1. Introduction

Mount Hermon, a prominent peak straddling the borders of modern-day Lebanon, Syria, and Israel, has long captivated scholars and theologians alike due to its multifaceted significance. Rising to an elevation of 9,232 feet (2,814 meters), it stands as the highest point along the eastern Mediterranean coast, serving not only as a geographical landmark but also as a cultural and spiritual beacon throughout history (Britannica, n.d.).

1.1. Etymology and Linguistic Roots

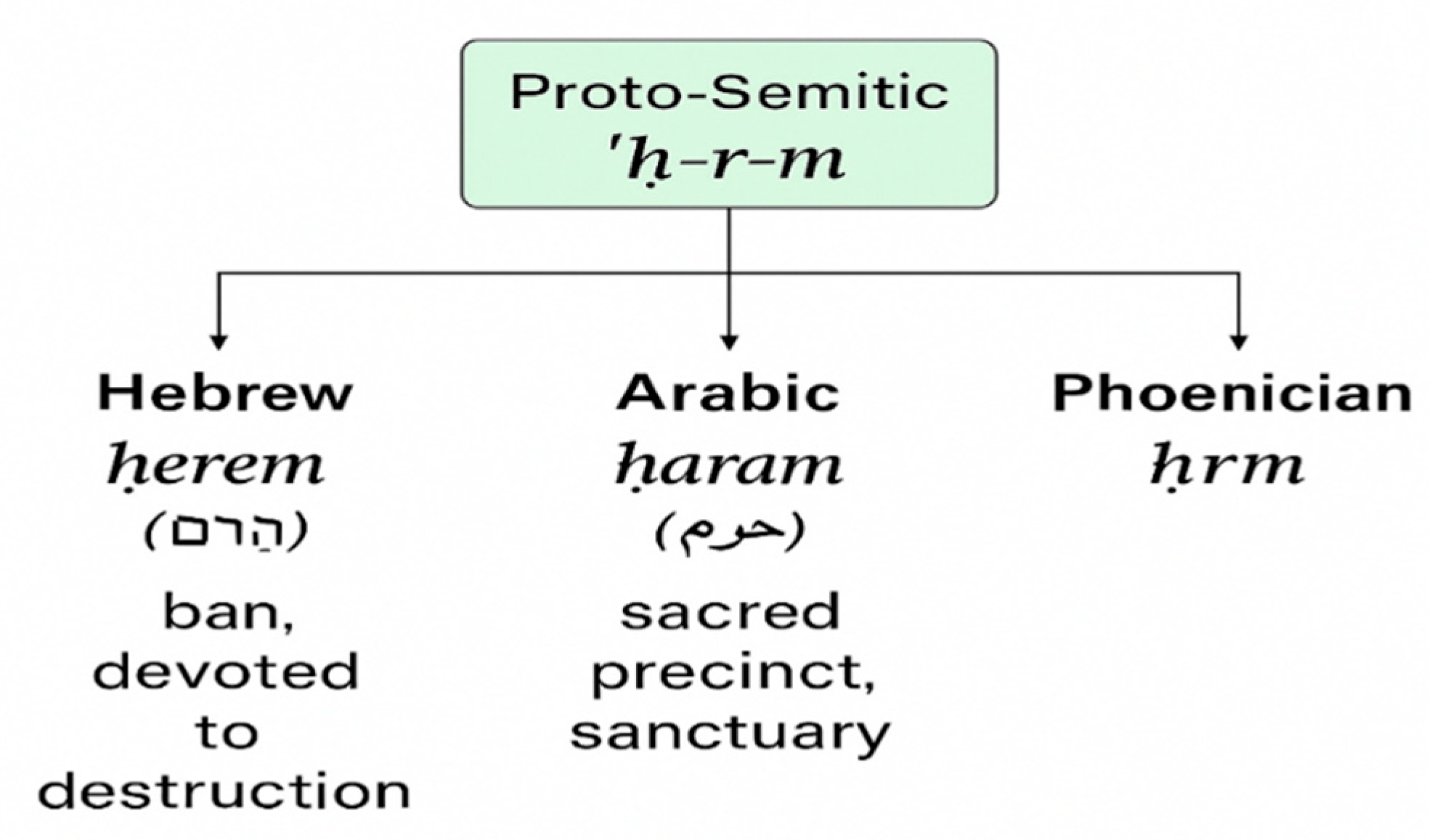

The name “Hermon” is deeply rooted in Semitic languages, particularly deriving from the triliteral root ḥrm (חרם), which encompasses meanings such as “taboo,” “consecrated,” or “sacred.” In Hebrew, the term ḥerem denotes something devoted or set apart, often for destruction or sacred purposes. Similarly, in Arabic, al-ḥaram refers to a holy or forbidden precinct, as seen in terms like al-Ḥaram al-Sharīf (the Noble Sanctuary) in Jerusalem (Abarim Publications, n.d.). This linguistic connection underscores the mountain’s longstanding association with sanctity and consecration.

The etymological significance is further emphasised by the mountain’s alternative names in ancient texts. In the Hebrew Bible, Mount Hermon is also referred to as “Sirion” by the Sidonians and “Senir” by the Amorites (Deuteronomy 3:9). These appellations, appearing in Bronze and Iron Age texts, highlight the mountain’s prominence across different cultures and periods (Wikipedia, n.d.).

1.2. Religious Significance

Mount Hermon’s sacred status is well-documented across various religious traditions. In the Hebrew Bible, it is mentioned multiple times, often symbolising grandeur and divine blessing. Psalm 133:3, for instance, compares the unity among brethren to the dew of Hermon descending upon the mountains of Zion, illustrating the mountain’s metaphorical association with harmony and blessing (Got Questions, n.d.).

Beyond the Hebrew scriptures, Mount Hermon holds significance in apocryphal texts. The Book of Enoch narrates that it was on Mount Hermon where a group of angels, known as the Watchers, descended to earth and swore an oath, leading to events that contributed to the corruption of humanity (1 Enoch 6:6). This narrative further cements the mountain’s role as a pivotal site in theological lore.

In Christian tradition, some scholars posit that Mount Hermon may have been the site of the Transfiguration of Jesus, although this is a subject of debate. The mountain’s towering presence and its proximity to Caesarea Philippi make it a plausible candidate for this significant New Testament event (UNESCO, n.d.).

1.3. Archaeological and Cultural Monuments

The slopes of Mount Hermon are dotted with numerous temples and sanctuaries, testifying to its historical significance as a centre of worship. One of the most notable is the temple at Qasr Antar, situated near the summit, which is considered the highest temple of the ancient world. A Greek inscription found at this site indicates that those who took an oath there were bound by a sacred commitment, linking the location to the aforementioned narrative in the Book of Enoch (Wikipedia, n.d.).

Additionally, over 30 shrines and temples have been discovered in the Mount Hermon region, many of which bear Greek inscriptions and are dedicated to various deities, including Zeus and Pan. These findings reflect the mountain’s integration into the religious practices of successive civilisations, from the Canaanites and Phoenicians to the Greeks and Romans (UNESCO, n.d.).

1.4. Political and Geopolitical Importance

Mount Hermon’s strategic location has rendered it a significant political landmark throughout history. In biblical times, it marked the northern boundary of the Promised Land, which Joshua conquered, delineating the extent of Israelite territory (Deuteronomy 3:8). The mountain also formed the northern border of the territory inherited by the half-tribe of Manasseh (1 Chronicles 5:23).

In more recent history, the mountain’s southern and western slopes became part of the Israeli-administered Golan Heights following the Arab-Israeli War of 1967. This region has since been developed for recreational purposes, including skiing, highlighting the mountain’s continued relevance in contemporary geopolitical dynamics (Britannica, n.d.).

1.5. Interdisciplinary Significance

The study of Mount Hermon’s nomenclature and significance necessitates an interdisciplinary approach that intertwines linguistics, theology, archaeology, and political history. The convergence of these fields allows for a comprehensive understanding of how the mountain’s name and status have evolved, reflecting broader cultural and societal shifts.

Linguistically, the root ḥrm serves as a common thread linking various Semitic languages and their conceptualisations of sacredness. Theologically, the mountain’s recurring presence in religious texts highlights its profound spiritual resonance across various faiths. Archaeologically, the numerous temples and inscriptions found on its slopes provide tangible evidence of its historical role as a worship site. Politically, its position as a boundary marker and its strategic importance in modern conflicts highlight its enduring relevance in territorial discourse.

Mount Hermon’s multifaceted significance, encompassing linguistic, religious, archaeological, and political dimensions, underscores its unique position in the historical and cultural landscape of the Near East. The mountain’s name, derived from the Semitic root ḥrm, encapsulates themes of sanctity and consecration, reflecting its longstanding association with the divine. Its prominence in religious texts, coupled with the archaeological remnants of ancient worship practices, attests to its central role in spiritual narratives. Moreover, its strategic location has rendered it a pivotal landmark in geopolitical terms, both in antiquity and in contemporary times. An interdisciplinary exploration of Mount Hermon thus offers valuable insights into the complex interplay between language, religion, culture, and politics in shaping the identity and significance of this storied mountain.

2. Research Methodology

To investigate the origin and evolution of the name “Mount Hermon,” this study employs a multidisciplinary qualitative methodology that encompasses three primary domains: historical linguistics, textual analysis, and political-historical geography. Each of these approaches contributes to a composite understanding of how the mountain’s name reflects intersecting sacred, linguistic, and territorial narratives across millennia.

2.1. Historical Linguistic Analysis

The study begins with a linguistic tracing of the root ḥrm (חרם), a Semitic triliteral root found across Hebrew, Arabic, Ugaritic, and Phoenician languages. Lexical sources and comparative grammars (Huehnergard & Rubin, 2012; Lipiński, 2001) were consulted to identify phonological, morphological, and semantic patterns of this root and its cognates. The analysis relied on diachronic linguistic tools to trace changes in usage and meaning across time and languages. This section utilised corpus-based etymological dictionaries and inscriptions from primary sources, such as Ugaritic tablets and Phoenician votive stelae, to establish the root’s original associations with “sacred,” “forbidden,” or “set apart.”

2.2. Textual and Theological Analysis

The second methodological strand involves an intertextual analysis of religious documents that reference Mount Hermon directly or indirectly. Key texts include the Hebrew Bible (e.g., Deuteronomy 3:9; Psalm 133:3), apocryphal texts such as the Book of Enoch, and early Islamic geographical writings. A hermeneutic approach was employed to interpret the role of Hermon in these texts, focusing on the mountain’s function as a sacred space, an oath-taking site, and a symbolic threshold between the divine and human realms (Nickelsburg, 2001; Cross, 1973). Greek and Roman inscriptions were also examined for religious references to the mountain, emphasising continuity or transformation in its symbolic status over time.

2.3. Political-Historical Geography

The third component of the methodology explores how the name and symbolism of Mount Hermon intersected with political boundaries, tribal territories, and imperial control. Historical maps, archaeological site reports, and territorial treaties (e.g., Hittite-Amorite documents) were analysed to assess the mountain’s function as a political marker. This approach was informed by theories of sacred geography, particularly how physical landmarks acquire political meaning through ritual and linguistic designation (Basso, 1996). Mount Hermon’s shifting geostrategic significance under different empires—Canaanite, Israelite, Assyrian, Hellenistic, Roman, and Islamic—was also incorporated to contextualise naming practices within broader processes of identity formation and statecraft.

2.4. Synthesis and Interpretation

The three strands—linguistic, textual, and geographical—were then synthesised through comparative and interpretive analysis. The goal was to establish correlations between semantic evolution and sociopolitical transformation. For example, the presence of the root ḥrm in both religious and administrative contexts points to a fusion of the sacred and the civic in naming practices. Moreover, shifts in meaning (from “consecrated” to “forbidden”) parallel transitions in the mountain’s ritual and territorial functions.

In sum, the research draws on both primary texts and secondary scholarship to reconstruct a layered narrative of Mount Hermon’s name. This triangulated methodology ensures that the inquiry is not limited to a single disciplinary lens but instead reflects the multifaceted nature of ancient naming practices and their enduring legacy.

3. Linguistic Origins

3.1. Proto-Semitic Roots

The name “Hermon” (Hebrew: חֶר\u05ְמֹן, Ḥermōn) likely derives from a Semitic root ḥrm (חרם), meaning “to devote,” “to consecrate,” or “to prohibit.” In early Semitic languages, this root appears in terms relating to sacred space or taboo, reflecting the mountain’s sanctified status (Huehnergard, 1995). The Arabic cognate “ḥarām” similarly connotes a sacred or forbidden place, such as al-Masjid al-Ḥarām in Mecca.

Figure 1.

Etymology of Semitic Root “*”.

Figure 1.

Etymology of Semitic Root “*”.

This diagram traces the evolution of the Semitic root ḥrm, which conveys meanings such as “sacred,” “forbidden,” and “devoted.” The root has permeated various Semitic languages, reflecting the cultural and religious significance of concepts associated with sanctity and prohibition.

Visual Description:

Proto-Semitic Root: ḥ-r-m

Hebrew: ḥerem (חֵרֶם) – “ban,” “devoted to destruction”

Arabic: ḥaram (حَرَم) – “sacred precinct,” “sanctuary”

Ugaritic: ḥrm – appears in contexts denoting sacredness or prohibition

Phoenician: ḥrm – used in inscriptions related to sacred offerings

This linguistic tree illustrates how the root ḥrm has been preserved and adapted across Semitic languages, often retaining its core association with sacredness and prohibition.

3.2. Comparative Linguistics

The etymological lineage of “Hermon” aligns with similar constructs in other Northwest Semitic languages. Ugaritic and Phoenician inscriptions employ ḥrm in religious contexts, particularly when describing offerings dedicated to deities (Sivan, 2001). Comparative linguistic analysis supports the idea that ancient Semitic peoples understood Hermon as a “dedicated” or “consecrated” site.

Figure 2.

Mt. Hermon (Jebel al-Shaykh) on the Lebanon–Syria border.

Figure 2.

Mt. Hermon (Jebel al-Shaykh) on the Lebanon–Syria border.

4. Religious Significance

4.1. Canaanite and Early Israelite Traditions

Mount Hermon is frequently associated with high places (bamot) used for worship in the Canaanite religion. It was considered a dwelling place for deities, particularly Baal, the god of storms. The Hebrew Bible mentions Hermon multiple times, sometimes under alternative names such as Sirion (used by Sidonians) and Senir (used by Amorites) (Deuteronomy 3:9). These names reflect regional linguistic variations and underscore the mountain’s sacred role in early Israelite cosmology (Cross, 1973).

4.2. Greco-Roman and Early Christian Views

Mount Hermon retained its sanctity during the Hellenistic and Roman periods, with temples constructed near its summit. Greek inscriptions refer to the mountain as a place where oaths were sworn before the “greatest and holy god” (Nickelsburg, 2001). Early Christian traditions, while focusing less on Hermon, inherited a symbolic geography that maintained its spiritual aura.

Figure 3.

Ruins of the Roman temple Qasr Antar on Mt. Hermon’s summit (2nd c. CE). Sources: Authoritative studies trace ḥrm to the “sacred/taboo” semantic field. Biblical, mythological, and archaeological records document Hermon’s cultic role from Canaanite times (e.g., treaty oaths, Ugaritic mythology) through the Hebrew Bible and into the Greco-Roman period. The UNESCO Tentative List and historical surveys confirm its enduring religious significance.

Figure 3.

Ruins of the Roman temple Qasr Antar on Mt. Hermon’s summit (2nd c. CE). Sources: Authoritative studies trace ḥrm to the “sacred/taboo” semantic field. Biblical, mythological, and archaeological records document Hermon’s cultic role from Canaanite times (e.g., treaty oaths, Ugaritic mythology) through the Hebrew Bible and into the Greco-Roman period. The UNESCO Tentative List and historical surveys confirm its enduring religious significance.

Hermon’s sacred character dates back to the Bronze Age. Nineteenth-century BCE Egyptian execration texts mention Siryon (Hermon), and approximately 1350 BCE, a Hittite–Amorite treaty invokes the gods of “Mt. Shariyanu” (Hermon). In the Hebrew Bible (12th–10th c. BCE), Hermon (also known as Sirion or Senir) marks Israel’s northern boundary, and Judges 3:3 even refers to Baal-Hermon as a local deity. Later biblical poetry (Psalm 133:3; Song of Solomon 4:8) praises Hermon’s dew and cypresses. By the Roman era, the summit sanctuary (Qasr Antar) had crowned the peak, and early Christians later identified Jebel esh-Sheikh with Jesus’ Transfiguration. Even today, the mountain (Jebel al-Thalj, “Snow Mountain”) is venerated by local Druze, Christian and Muslim communities.

4.3. Islamic Traditions

In Islamic tradition, Hermon does not occupy a central religious position, but the semantic link to the Arabic ḥarām imbues it with reverence. Some Islamic geographers and commentators note the mountain’s biblical associations, preserving its status as a spiritually charged location.

The Qur’an, unlike the Hebrew Bible, does not explicitly mention Mount Hermon by name. In the Bible, Hermon is referred to in passages such as Deuteronomy 3:9 and Psalm 133:3, where it is portrayed as a sacred and majestic mountain. By contrast, the Qur’anic text neither names Hermon nor directly identifies it as part of the sacred geography of revelation. This absence has prompted scholars to investigate whether indirect allusions or linguistic parallels exist within the Qur’an.

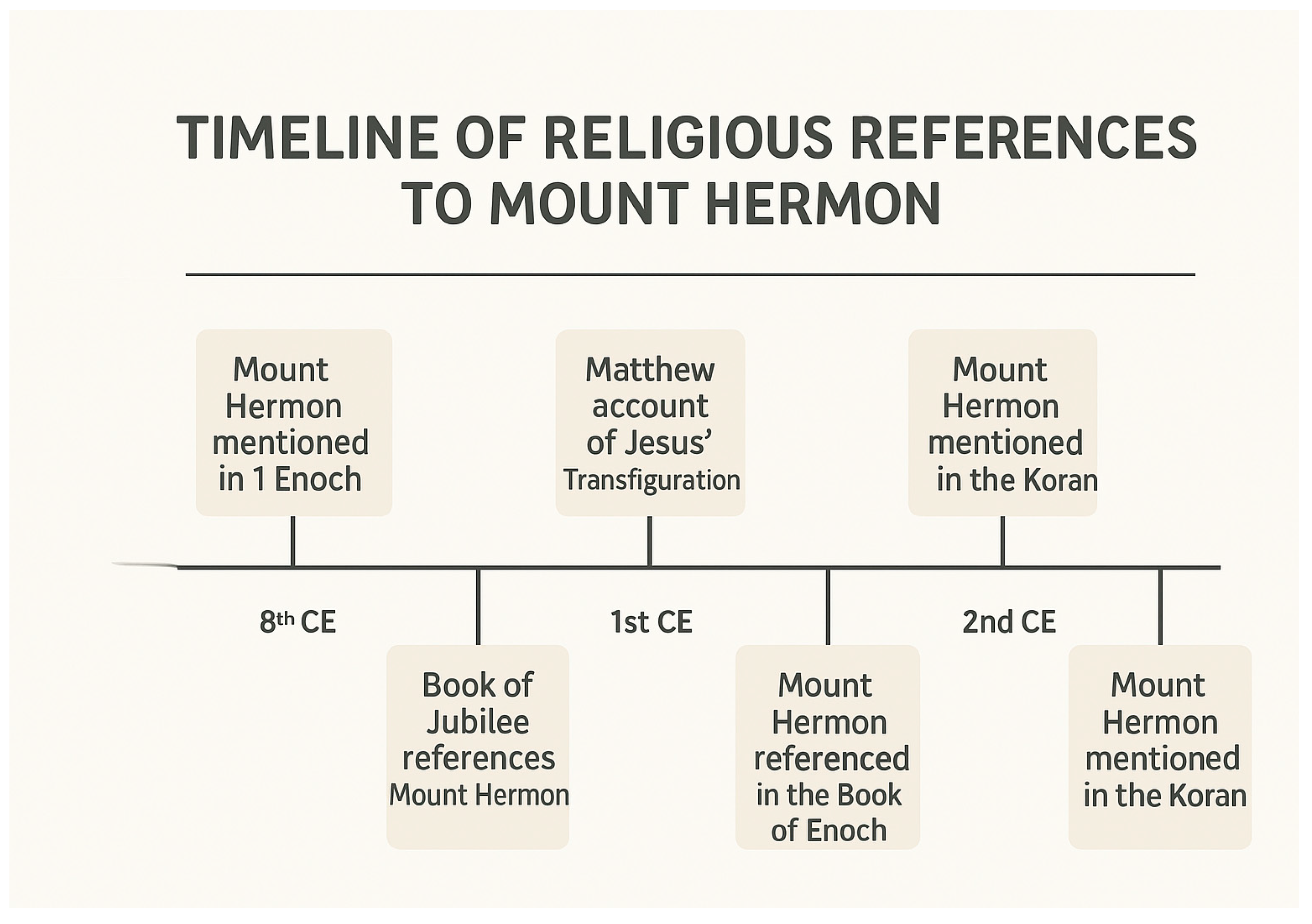

Figure 4.

Timeline of Religious References to Mount Hermon.

Figure 4.

Timeline of Religious References to Mount Hermon.

The main area of scholarly discussion arises from the Semitic root ḥrm (حرم), meaning “sacred,” “forbidden,” or “protected.” This root appears extensively in the Qur’an in contexts such as al-Masjid al-Ḥarām (the Sacred Mosque in Mecca, Qur’an 2:144, 2:149), al-ḥaram al-sharīf (the sacred precinct), and terms such as ḥurmat (sanctity) (Abdel Haleem, 2005). The name “Hermon” (Hebrew: חרמון, Ḥermōn) shares the same Semitic root, suggesting that in ancient usage the mountain may have carried associations of sanctity. Although this linguistic parallel is compelling, it is important to stress that the Qur’an does not explicitly establish this connection.

Later Islamic geographers and exegetes occasionally speculated on the role of Hermon within sacred history, sometimes linking it with traditions of the prophets or identifying it as part of the boundary of the Holy Land (al-Ṭabarī, 1987). However, these are exegetical extrapolations rather than Qur’anic attestations. They reflect an effort by Muslim scholars to situate Qur’anic geography within the broader biblical and Near Eastern landscape.

Thus, the significance of Mount Hermon in Qur’anic studies lies less in a direct textual reference and more in the intertextual and linguistic dimensions of sacred geography. The Qur’an often speaks of “the blessed land” (al-arḍ al-mubārakah, Qur’an 21:71; 17:1), which many exegetes interpreted as the Levant (al-Shām). Since Hermon is part of this geographical region, it is indirectly encompassed within the Qur’an’s conceptualisation of sacred territory, even if it remains unnamed.

In conclusion, Mount Hermon should be understood as a biblically attested sacred site that carries linguistic resonances with Qur’anic vocabulary but is absent as a direct referent in the Islamic scripture. Its theological significance in Islamic thought arises from later interpretive traditions and the shared Semitic heritage of sacred language, rather than from an explicit Qur’anic verse.

Chronological chart illustrating significant religious references to Mount Hermon from Egyptian execration texts (c. 19th c. BCE), Hittite-Amorite treaties (c. 14th c. BCE), the Hebrew Bible (e.g., Deuteronomy, Psalms), Roman temple inscriptions (c. 2nd c. CE), Christian pilgrim texts, and medieval Islamic geography. Sources: Cross (1973); Nickelsburg (2001); Harley & Woodward (1987).]

This timeline presents significant religious and historical references to Mount Hermon, highlighting its enduring sacred status across various cultures and epochs.

Visual Description:

19th Century BCE: Egyptian Execration Texts mention šrynw (Sirion), an early reference to Mount Hermon.

14th Century BCE: Hittite-Amorite treaties invoke the gods of “Mount Shariyanu” (Hermon) as divine witnesses.

12th–10th Century BCE: Hebrew Bible references:

Deuteronomy 3:9 – Hermon is called Sirion by the Sidonians and Senir by the Amorites.

Judges 3:3 – Mention of Baal-Hermon, indicating local deity worship.

Psalm 133:3 – Hermon’s dew symbolises blessing.

8th–7th Century BCE: Assyrian inscriptions (e.g., Shalmaneser III) mention Mount Saniru (Hermon) in military campaigns.

2nd Century CE: Roman temple Qasr Antar on Hermon’s summit; inscriptions suggest oaths taken in the name of the “greatest and holy god.”

1st Century CE: Early Christian traditions associate Mount Hermon with the Transfiguration of Jesus, though not explicitly named in the New Testament.

Medieval Period: Islamic geographers and commentators note Hermon’s biblical associations, maintaining its revered status.

5. Political Dimensions

5.1. Territorial Boundaries and Identity

Mount Hermon has historically marked political boundaries—from ancient Canaanite territories to the frontiers of Roman provinces. In modern times, it serves as a contested geopolitical marker between Lebanon, Syria, and Israel. The enduring sanctity of Hermon contributed to its role as a territorial anchor in the construction of political identities (Millar, 1993).

5.2. Imperial Appropriations

Empires throughout history have appropriated the name and image of Hermon to legitimise their rule. For instance, the Roman use of inscriptions and temple-building near Hermon reinforced imperial authority through religious symbolism. Similarly, biblical references to Hermon in the context of conquest narratives suggest a divine sanctioning of territorial control (Miller, 2002).

6. Hermon in Later Historical Memory and National Identity

6.1. Medieval Perceptions and Cartographic Legacies

Hermon maintained a spectral presence in religious cartography and pilgrimage literature throughout the medieval period. Jewish travellers such as Benjamin of Tudela and Christian chroniclers associated Hermon with divine elevation and boundary, though often confusing it with other regional highlands. Islamic geographers, such as al-Idrisi, integrated Hermon into broader maps of Bilad al-Sham, indicating its sustained significance (Harley & Woodward, 1987).

6.2. Zionist and Arab Nationalist Narratives

In the 20th century, Hermon reemerged as a symbol of national heritage. Zionist narratives linked Hermon to biblical geography and Israeli security, especially after the Six-Day War and the occupation of the Golan Heights. Arab nationalist historiography, in contrast, emphasised Hermon as part of a shared Levantine identity that transcended modern borders. Both perspectives imbued the mountain with ideological meaning that reflected broader territorial aspirations (Kimmerling, 2001).

6.3. Contemporary Conflicts and Heritage Politics

Mount Hermon remains a politically sensitive zone and a powerful emblem in heritage discourse today. Debates about archaeological excavation, ecological preservation, and tourism intersect with military control and cultural claims. The name Hermon thus continues to resonate with layered meanings, situating it at the nexus of history, language, religion, and politics (Ben-Yehuda, 1995).

7. Memorising the Culture and Oral Traditions of the Inhabitants

Mount Hermon’s surrounding communities have historically relied on rich oral traditions and mnemonic practices to preserve cultural, spiritual, and ecological knowledge. These traditions serve as a living archive, through which history, myth, language, and identity are transmitted across generations. Among the most enduring features of this culture of memory are storytelling, poetic forms, liturgical chanting, sacred oaths, seasonal festivals, and pilgrimage songs—all of which encode collective memory and connect inhabitants to the land.

7.1. Oral Histories and Storytelling

The inhabitants of Mount Hermon, particularly Druze, Christian, and Alawite communities, have maintained a strong oral tradition that passes down legends about the mountain’s divine protection, the lives of saints, and historical battles. These stories often embed local topographies—such as springs, caves, and peaks—within moral or theological frameworks (Meri, 2002). For instance, narratives about angels descending upon Hermon or prophets ascending from its slopes function as mythic accounts and mnemonic anchors for ritual practices and social cohesion.

7.2. Memory Through Poetics and Chanting

In ancient and contemporary practices, poetic and chant-based forms have served as mnemonic devices to preserve liturgical language and genealogies. In Semitic traditions, particularly those associated with Aramaic-speaking Christian sects and Arabic-speaking mountain dwellers, poetic refrains and chanted litanies ensure continuity of memory. These forms often invoke Hermon as a divine threshold—”a place set apart” (ḥarām)—reinforcing its sacred geography through repetitive structure and sacred semantics (O’Connor, 1997).

7.3. Sacred Oaths and Covenant Language

Mount Hermon appears prominently in ancient covenantal and oath-taking practices. Notably, in the apocryphal Book of Enoch, Hermon is where fallen angels swore their mutual pact, binding themselves with a sacred oath (Nickelsburg, 2001). This mythic mountain use illustrates how memorisation is tied to cosmic and legal orders. Local communities have echoed this tradition through oaths and vows sworn at specific locations on the mountain, often invoking divine witness and ancestral memory.

7.4. Memory and the Seasons: Festivals and Pilgrimages

Seasonal rituals tied to agriculture and transhumance also reflect mnemonic systems. Spring and autumn festivals incorporate songs, prayers, and communal meals that remember ancestral migrations or divine interventions associated with the mountain. Oral performances during these events renew social bonds and transmit ethical codes. Pilgrimages to high-altitude shrines or caves on Hermon often involve recounting family histories and reciting prayers memorised from childhood (Tapper, 1990).

7.5. Landscape as Memory Archive

The very geography of Hermon serves as a mnemonic field. Particular rock formations, tree groves, and water sources are spatial cues for storytelling and ritual. As anthropologist Keith Basso (1996) argued in another indigenous context, “place-making is a way of constructing history itself.” On Hermon, memory is inscribed into the landscape through naming practices, ritual repetition, and symbolic associations. Local toponyms frequently encode historical episodes or mythic encounters.

7.6. Language as a Medium of Memory

Multilingualism—Arabic, Aramaic, Hebrew, and earlier Canaanite tongues—has long shaped the memorising culture of Hermon’s inhabitants. Each language carries its own semantic and theological associations. Oral transmission in these languages ensures that identity is remembered through content and form. The linguistic diversity also reflects the region’s historical layers, preserving ancient syntactic structures and metaphoric frameworks (Hezser, 2001).

7.7. Contemporary Challenges and Preservation Efforts

In the modern era, the memorising culture of Mount Hermon faces challenges due to urbanisation, political instability, and generational shifts. Oral traditions are increasingly documented in digital archives and ethnographic recordings to prevent cultural erosion. Initiatives by local scholars and international anthropologists aim to record elders’ narratives, ritual songs, and place-based memories before they are lost (UNESCO, 2011).

In sum, the inhabitants of Mount Hermon possess a deeply rooted culture of memory that enshrines sacred geography, ritual continuity, and linguistic legacy. Their memorising practices illuminate how communities living on contested or transcendent terrain preserve identity through embodied knowledge, oral transmission, and spatial symbolism.

8. Conclusions

Mount Hermon embodies a rich interplay of linguistic heritage, religious symbolism, and political significance. From its Proto-Semitic roots to its invocation in sacred texts and imperial ideologies, Hermon stands as a linguistic artefact and sacred landmark that reflects the evolving cultures of the Near East. As a node of convergence for language, mythology, power, and identity, Mount Hermon offers a compelling case study in the longue durée of place-naming and its role in shaping collective memory.

9. Future Directions for Research

While much has been explored about Mount Hermon’s name, sacred status, and political symbolism, further interdisciplinary research is warranted. Potential areas include:

Epigraphic Surveys: Continued archaeological and epigraphic investigations near Mount Hermon may yield inscriptions or artefacts that further clarify the linguistic transitions from the Canaanite to the Aramaic, Greek, and Arabic periods.

Digital Toponymy: A digital atlas of Hermon’s names across cultures and periods could serve as a resource for historical geography and linguistics scholars.

Interfaith Pilgrimage Studies: Ethnographic studies of contemporary religious tourism could provide insight into how Hermon’s sacred character is negotiated in modern multi-faith contexts.

Climate and Sacred Landscapes: Hermon’s unique alpine climate may have influenced its religious designation. Future geo-environmental studies could explore links between ecological distinctiveness and cultural sacralisation.

In advancing these areas, scholars will deepen our understanding of Mount Hermon itself and the broader processes through which language, faith, and politics shape place.

References

- Abarim Publications. (n.d.). The name Hermon: Meaning and etymology. Retrieved from https://www.abarim-publications.com/Meaning/Hermon.html.

- Basso, K. H. (1996). Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language Among the Western Apache—University of New Mexico Press.

- Ben-Yehuda, N. (1995). The Masada Myth: Collective Memory and Mythmaking in Israel. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Britannica. (n.d.). Mount Hermon, Height, Map, & Facts. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/place/Mount-Hermon.

- Cross, F. M. (1973). Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic: Essays in the History of the Religion of Israel. Harvard University Press. [CrossRef]

- Got Questions. (n.d.). What is the significance of Mount Hermon in the Bible? Retrieved from https://www.gotquestions.org/mount-Hermon.html.

- Harley, J. B., & Woodward, D. (Eds.). (1987). The History of Cartography, Volume 1: Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient, and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean. University of Chicago Press.

- Hezser, C. (2001). Jewish Literacy in Roman Palestine. Mohr Siebeck. [CrossRef]

- Huehnergard, J. (1995). Semitic Languages. In J. M. Sasson (Ed.), Civilisations of the Ancient Near East (Vol. 4, pp. 2117–2134). Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- Huehnergard, J., & Rubin, A. D. (2012). Phyla and waves: Models of classification of the Semitic languages. In S. Weninger (Ed.), The Semitic languages: An international handbook (pp. 259–278). De Gruyter Mouton.

- Kimmerling, B. (2001). The Invention and Decline of Israeliness: State, Society, and the Military. University of California Press. [CrossRef]

- Lipiński, E. (2001). Semitic languages: Outline of a comparative grammar. Peeters.

- Meri, J. W. (2002). The Cult of Saints among Muslims and Jews in Medieval Syria. Oxford University Press.

- Millar, F. (1993). The Roman Near East, 31 B.C.–A.D. 337. Harvard University Press.

- Miller, P. D. (2002). The Religion of Ancient Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. [CrossRef]

- Nickelsburg, G. W. E. (2001). 1 Enoch 1: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 1–36; 81–108. Fortress Press.

- O’Connor, M. (1997). Hebrew Verse Structure. Eisenbrauns.

- Sivan, D. (2001). A Grammar of the Ugaritic Language. Brill.

- Tapper, R. (1990). “Anthropologists, Historians and Tribespeople on Tribe and State Formation in the Middle East.” In P. Khoury & J. Kostiner (Eds.), Tribes and State Formation in the Middle East, pp. 48–73. University of California Press.

- UNESCO. (n.d.). Sacred Mount Hermon and its associated cultural monuments. Retrieved from https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6432/.

- UNESCO. (2011). Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. Retrieved from https://www.unesco.org.

- Wikipedia. (n.d.). Mount Hermon. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mount_Hermon.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).