1. Introduction

As the most evolved end members of granite series, rare-metal-bearing granites generally show remarkable enrichment in multiple high-value metallic elements including Li, Ta, Nb, W, Be and Sn. The study of rare-metal granites provides valuable insights into processes such as crustal growth, reworking events, thermal history, and fluid evolution during orogenic events [1, 2].

The Dahutang orefield, as the world's second largest W deposit, associated with Cu-Mo and rare metal mineralization (including Au, Ag, Sn, and so on), was identified in 2012 in northern Jiangxi Province, South China [

3,

4]. The genetically related Mesozoic peraluminous granites have subsequently attracted significant attentions owing to their considerable economic potential and scientific value. However, recognizing and characterizing these granites presents substantial challenges due to three primary factors: ⅰ) granites are mainly in a concealed state; ⅱ) the local vegetation is luxuriant, which leads to most outcrops being concealed; and ⅲ) they do not bear markedly distinctive petrophysical features, which hampers geophysical exploration.

Substantial research progress has been carried in understanding the petrogenesis and emplacement history of these granites, with notable achievements in rock geochemistry and isotope geochemistry studies. In particular, extensive investigations have been conducted on the multi-stage magmatic evolution and associated mineralization processes [5-13]. However, the genesis of the ore deposit and the ore-related granites remains debated, with controversies mainly focusing on: the spatiotemporal relationship between multi-stage granites and mineralization processes; the key characteristics of each stage of magmatism and mineralization; the co-existence mechanism of copper deposits and rare-metal mineralization.

This study integrates bulk-rock geochemical data of the petrographically well-characterized Mesozoic granites associated with W-Cu-Mo-(±Sn-Li-Ta-Nb) mineralization, along with monazite U-Pb ages, and wolframite mineral analyses. These data are applied to unravel the genesis and evolution of these granites, providing a comprehensive understanding of their origin and the relation with mineralization. This study offers new insights into the broader geological framework and mineral potential of the Dahutang ore cluster.

2. Geologic setting

2.1. Regional geology

The Dahutang polymetallic deposit in Northern Jiangxi (Figure1a) is located in the central segment of the Jiangnan Orogenic Belt, locally termed as the Jiuling Mountainswithin. The 1500-km-long ENE-WSW trending Jiangnan Orogenic belt lies along the southeastern margin of the Yangtze block (

Figure 1). The Jiangnan Orogenic belt consists of Neoproterozoic arc terranes, which have experienced syn-schistose deformation and greenschist-facies metamorphism, culminating with the intrusion of Neoproterozoic granites (Jiuling granite; 819 Ma) [

14,

15]. The basement rocks of the Jiangnan Orogen are mainly Neoproterozoic metasedimentary and minor meta-volcanic rocks, known as the Shuangqiaoshan Group in this region.

Tectonically, the Dahutang ore cluster is bounded by the Jiujiang-Shitai and Jiangshan-Shaoxing faults (

Figure 1). The region exhibits well-developed fault systems, including approximately W-E trending faults in the northern portion that intersect the Xin’anli tungsten deposit. Additionally, several NE-NNE trending faults are present (

Figure 1b). The longest of these is the NNE-trending Xianguoshan- Shimensi- Shiweidong fault, extending over 25 km and hosting numerous ore deposits along its strike within the Dahutang district.

The meta-sedimentary sequence is the Neoproterozoic Shuangqiaoshan Group, a marine volcanic-clastic sedimentary succession comprising sandstones, phyllites, and slates interlayered with quartz-keratophyres and tuffs. The largest magmatic intrusion is the Jiuling Pluton, a Neoproterozoic granodiorite, emplaced as a batholith in Shuangqiaoshan Group.characterized by its It is gray in color and of coarse-grained texture and consists of medium- to coarse-grained biotite granodiorite. It is predominantly composed of plagioclase (65%), quartz (20%), and biotite (15%). The Jiuling Pluton contains numerous dark gray, deep-source xenoliths, typically rounded or elliptical in shape (with some irregular forms), ranging in size from several centimeters to tens of centimeters, and distributed sporadically throughout the intrusion.

Mesozoic intrusions occurr as small stocks, bosses, and sills, intrude into both the Neoproterozoic granodiorite and the Shuangqiaoshan Group.

2.2. Petrography of Mesozoic granites

Mesozoic granites, occurring as small stocks, bosses, and sills, emplaced into both the Neoproterozoic granodiorite and Shuangqiaoshan Group. The rock types closely associated with mineralization primarily include biotite granite, two-mica granite, and muscovite granite.

Biotite granite (G1) exhibits a porphyritic texture (

Figure 2a), with a medium-grained monzonitic matrix. Phenocrysts predominantly comprise quartz (~3%), plagioclase (~6%), K-feldspar (~5%), and biotite (1%) with variable size. The matrix consists mainly of quartz (~35%), K-feldspar (~32%), plagioclase (~25%), biotite (~6%), muscovite (~2%), and minor magnetite. The rock has undergone intense greisenization, with irregular microcrystalline secondary quartz and sericite aggregates filling intergranular spaces, resulting in serrated edges on early-formed minerals. Plagioclase exhibits polysynthetic twinning or rhythmic zoning, with crystal edges showing a serrated shape due to fluid dissolution (

Figure 2a).

Two-mica granite (G2) displays a massive structure and porphyritic texture, with phenocrysts dominated by plagioclase (~15%), K-feldspar (~10%), quartz (~10%), biotite (~3%), and muscovite (~2%). The matrix exhibits fine-grained texture (

Figure 2b). Major mineral compositions include plagioclase (~15%), K-feldspar (~15%), quartz (~25%), muscovite (~3%), and minor biotite (1%), with accessory minerals such as ilmenite and magnetite. Quartz is found also as finer recrystallized crystals surrounding the rock constituting minerals (

Figure 2b) which sometimes shows polygonal boundaries. K-feldspars are represented by coarse subhedral to anhedral tabular cystals of perthitic orthoclase with modest quantities of microcline. Biotite occurs as thick greenish brown to yellowish brown flakes and is replaced partially or completely by muscovite, chlorite and iron oxides. Sericite is found as irregular aggregates replaces K-feldspar, biotite and is replaced by chlorite and opaque minerals (

Figure 2c).

The muscovite granite (G3) exhibits distinct zoning structure. From the outer to the inner portions of the rock-mass contact zone, it can be subdivided into fine-grained → medium-grained → coarse-grained muscovite granite. The fine-grained muscovite granite shows strong mineralization, particularly Li mineralization, serving as the primary ore-hosting rock in the mining area. In contrast, the medium- to coarse-grained muscovite granite distal to the contact zone displays poor mineralization. The rock is grayish-white to flesh-red in color and composed of quartz (~40%), plagioclase (~30%), K-feldspar (~25%), muscovite (11-15%), and trace biotite (~2%) (

Figure 2d). The fine-grained muscovite granite has undergone intense albitization, as evidenced by the nearly complete replacement of K-feldspar by albite and muscovite, the predominant alteration of plagioclase into albite, and the common occurrence of Li-mica bordering and replacing the margins of muscovite (

Figure 2d). Lithium is predominantly hosted in Li-mica. The local fine-grained muscovite granite gradually transitions, instead of a distinct interface, into albite granite (G4).

3. Ore characteristics

Fifteen large, medium, and small mineral deposits and ore occurrences have been identified in the Dahutang and its marginal area, forming a significant ore concentration zone dominated by W associated with Cu, Mo, Li, Sn, Nb, Ta, and other rare metals. The region hosts a resource of 1.1×10

6 t of WO

3, accompanied by 0.65×10

6 t Cu and 28000t Mo. Multiple large-to-medium-sized W-Cu-Mo polymetallic deposits are distributed across the area, including the Shimensi, Dawutang, Shiweidong, and Kunshan mining areas (

Figure 1b).

Orefield mainly comprise four genetic types: disseminated vein type, altered granite type, hydrothermal cryptoexplosive breccia type, and large quartz vein type (

Figure 3). Among these, the former two types are the most economically important and exhibit typical porphyry-style characteristics, including pervasive whole-rock alteration-mineralization, low-grade mineralization, and large-tonnage deposit scales. The industrial W ore types: Scheelite dominant ores with minor wolframite and sulfides in the disseminated-veinlet and altered granite, and wolframite dominant ores with minor scheelite and sulfide in the quartz vein.

Disseminated-veined and altered-granite ores occur in the contact zones between Mesozoic granites and Neoproterozoic biotite granodiorite (

Figures 3a, b). These ores generally dip gently, typically at 10°-30°, largely concurrent with the orientation of the contacting surfaces. These type ores are well-developed in the Shimensi and Dawutang mining areas. Disseminated-veined ores that distribute within the exocontact zones (the Neoproterozoic granodiorite) are the most important type in the mining area (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4a, b), and exhibit higher grade and better mineralization continuity, whereas those in the endocontact zone are generally thinner, lower-grade, and show discontinuous mineralization. Hydrothermal alteration associated with disseminated-vein type ores is extensive, with greisen alteration being the major type. The altered-granite type ores occurs in the cupolas of the muscovite granite and albite granite the (

Figure 3b). Potassic alteration and albite alteration is the dominant alteration type associated with altered-granite type ores (

Figure 2d). These two type ores share similar strikes and geometries, often coexist or occur independently. Major ore minerals include scheelite, wolframite, chalcopyrite, lepidolite, zinnwaldite, and molybdenite.

Hydrothermal cryptoexplosive breccia type ores are mainly distributed in the upper parts of Mesozoic granite intrusions, with ores orientations perpendicular to the intrusive contact surfaces (

Figure 3a). The breccia matrix consists of magma melt or felsic hydrothermal materials, while breccia are predominantly Neoproterozoic granodiorite, with minor Mesozoic granite (

Figures 4e). These ore bodies exhibit complex morphologies, with type ores dominated by veinlet-disseminated ores. Ore assemblages are intricate and diverse, with primary metallic minerals including wolframite, scheelite, chalcopyrite, and molybdenite, followed by stannite, sphalerite, cassiterite, and others.

Quartz-vein type ores are primarily hosted within Neoproterozoic granodiorite and Shuangqiaoshan Group (

Figure 4g, h), and its occurrence is mainly controlled by fracture structures. This type ores are commonly seen in the Shimensi, Shiweidong, and Kunshan mining areas. This type of ores has the highest W average grade of 0.282% and accounts for about 1% of the total W resource. Wolframite is also the main ore mineral, and scheelite is the second. Wolframite occurs as coarse tabular or columnar crystals along the walls of large veins, with long axes growing perpendicular or oblique to the vein walls, forming symmetrical comb structures (

Figure 4g). Associated metallic minerals primarily include molybdenite (

Figure 4i) and chalcopyrite.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. minerals collection

Wolframite, monazite, and zircon minerals were sourced from the Mesozoic granites of the Dahutang orefield (

Table 1). These minerals were separated from the samples using the heavy mineral separation method, and homogeneous, transparent grains were selected under a binocular microscope to prepare sample mounts. 22 samples were collected for whole-rock chemical analyses from the Shimensi mining area, the Kunshan mining area and the Dawutang mining area.

4.2. Back-Scaterred Electron of wolframite

The targets and Back-Scaterred Electron (BSE) photographs of wolframite, monazite, and zircon were conducted at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The major elements analyses of wolframite were conducted at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences by the JXA-8100 electron probe with a excitation voltage of 20 KV, a excitation current of 1×10−8Aand a spot size of 0.5 μm.

4.3. Laser ablation ICP-MS of monazite and zircon

The U-Pb dating analyses of monazite and zircon was carried at the isotope Laboratory of Tianjin Geological Survey Center of China Geological Survey by the laser ablation Multi-receiving Plasma mass spectrometer (LA-ICP-MS), with using an excimer laser of NEW WAVE 193 nm FX ArF, a NEPUNE multi-receiver inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer. Each analysis consisted of 20~30s of background signal acquisition followed by 65s of ablation. During sample analysis, monazite standard sample 44,069 and zircon GJ-1 were used as the external age standard for U-Pb isotopic fractionation correction. In the standard deviation of the standard of isotope ratio, the standard deviation of the isotope ratio of the sample and the standard isotope ratio is also taken into account, and the relative standard deviation is set at 2%. Isotopic age mapping was performed using the ISOPLOT/EX 3.23 procedure [

19]. Data without common Pb correction are plotted on the Tera-Wasserburg diagram. The

206Pb/

238U age was calculated as a lower intercept of the

206Pb/

238U value of the regression line with the Concordia curve. Weighted mean ages for each spot were calculated using the

207Pb-correction for common Pb.

4.4. whole-rock chemical analyses

In this paper, Whole-rock major- and trace-element analyses were carried out at the analysis and test Center of Nanjing Geological Survey Center of China Geological Survey. Fresh samples were crushed and powdered in an agate grinder mill and sieved with a < 200 μm mesh. Major elements were analyzed as a fused disk using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy (PANalytical PW2424) with measurement uncertainty standard deviation of <5 %. LOI at 1000℃ was measured for each sample, and elemental concentrations were normalized with the results of both analyses. Rare earth and other trace elements were analyzed using a Perkin Elmer Elan 9000 inductively coupled plasma-mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS) in solution mode. Prepared samples were added to lithium metaborate/lithium tetraborate flux, mixed well and fused in a furnace at 1025℃. The resulting melts were then cooled and dissolved in a mixture of nitric, hydrochloric and hydrofluoric acids prior to analysis. Standards were used to monitor the reliability of analytical results, and accuraccy were 1~5 % for major elements and 5~10 % for most trace elements.

5. Results

5.1. Geochronology

5.1.1. Dawutang mining area

Monazites from the medium- to coarse-grained G3 granite (14PM-5) and fine-grained G2 granite (14YKD-1) are light yellow, subhedral to euhedral, with grain sizes ranging from 50 to 80 μm. Under back-scattered electron (BSE) images, their structures are relatively homogeneous, with indistinct zoning (

Figure 5). A total of 28 and 29 analytical points were acquired for 14PM-5 and 14YKD-1, respectively. Data were plotted and calculated on Tera-Wasserburg inverse concordia diagrams. For 14PM-5, the monazite lower intercept age is 142.9±1.0 Ma (MSWD=2.3), with a weighted mean

206Pb/

238U age of 142.7±1.0 Ma (MSWD=1.1). For 14YKD-1, the monazite lower intercept age is 139.2±0.98 Ma (MSWD=1.3), and the weighted mean

206Pb/

238U age is 140.6±1.3 Ma (MSWD = 0.52) (

Figure 6,

Table 2).

Zircons from the porphyritic G2 granite (14PM-8) are elongated, subhedral to euhedral, with grain sizes varying from 50 to 100 μm. Under cathodoluminescence (CL) imaging, zircons are dark in color, displaying zoning, and some grains exhibit core-rim structures with bright cores and dark black rims. A total of 16 zircon grains from 14PM-8 were analyzed, but data from 7 grains with U>10,000 ppm and obvious inherited characteristics were excluded from plotting and calculations. Measured

207Pb/

206Pb and

206Pb/

238U values (without common Pb correction) were plotted on a Tera-Wasserburg inverse concordia diagram, and the weighted mean

206Pb/

238U age was calculated. Results yield a lower intercept age of 140.0±1.4 Ma (MSWD=1.6) and a weighted mean age of 140.3±1.9 Ma (MSWD = 0.43) (

Figure 6,

Table 2).

5.1.2. Shiweidong mining area

The monazites from the G2 granite (14SWD-1) are light yellow, euhedral to subhedral crystals ranging from 60 to 90 μm in size. Backscattered electron (BSE) imaging reveals a uniform internal structure with indistinct zoning (

Figure 5). Thirty analyses of these monazites yield a lower intercept age of 137.6 ± 1.3 Ma (MSWD=3.0) and a weighted average

206Pb/

238U age of 137.5 ± 1.0 Ma (MSWD=0.72) (

Figure 6,

Table 2).

5.1.3. Kunshan mining area

The monazites from two G1 granite samples (14YSD-3-1, 14YSD-3-2) are colorless, transparent, subhedral columnar crystals measuring 80-150 μm, displaying distinct banding under backscattered electron (BSE) imaging (

Figure 5). Thirty-two analyses of monazites from 14YSD-3-1 yield a lower intercept age of 149.6±0.6 Ma (MSWD=0.8) and a weighted mean

206Pb/

238U age of 149.5±0.9 Ma (MSWD = 0.3). Thirty-one analyses of monazites from 14YSD-3-2 yield a lower intercept age of 151.8±1.5 Ma (MSWD = 0.7) and a weighted average

206Pb/

238U age of 151.4±1.4 Ma (MSWD = 1.2;

Figure 6,

Table 2).

5.2. Geochemistry of wolframite

Wolframite occurs in the G1 of the Shimengsi and Kunshan mining areas, as well as the G2 of the Dawutang and Shiweidong mining areas. It is black to brownish-black in color with euhedral to subhedral crystals ranging from 60 to 150 μm in size, exhibiting tabular, acicular, or hair-like morphologies. Electron microprobe analysis data are presented in

Table 3.

The results show that wolframites are primarily composed of WO

3, MnO, and FeO, with trace amounts of Ta

2O

5, MoO

3, and PbO. Significant differences exist in the major element compositions of wolframites from different granites (

Figure 7): G1 wolframites range from 74.41% to 77.06% (avg. 76.08%) WO

3, 14.19% -18.85% (avg. 17.29%) FeO, and 5.65%-10.31% (avg. 7.10%) MnO; those of G2 show 75.12% -76.63% (avg. 75.84%) WO

3, 17.52%-21.09% (avg. 19.69%) FeO, and 3.36%- 6.68% (avg. 4.72%) MnO.

The crystal chemical formula of wolframite is determined to be (Fe

0.60-0.89, Mn

0.14-0.44)

1.01-1.05W

0.98-1.01O

4, indicating a slight deficit in W

6+ and an excess of Fe

2+ and Mn

2+, with Mn

2+ being significantly lower in content compared to Fe

2+, suggesting that the wolframite is iron-rich. The deficit in W

6+ may be due to the substitution of W by trace elements, such as Ta and Mo, in the wolframite lattice. WO

3 exhibits a negative correlation with FeO and a positive correlation with MnO in wolframite. A strong linear negative correlation is observed between MnO and FeO (

Figure 7). G1 Wolframites contain relatively higher concentrations of WO

3 and MnO, whereas G2 wolframites show significantly higher FeO content.

In addition to major elements such as W, Fe, and Mn in wolframite, the chemical characteristics of trace elements like Ta, Nb, and Mo warrant attention. Wolframites exhibit remarkably high Ta contents (Ta

2O

5: 0.38%-0.64%, avg. 0.50%), whereas Nb contents are extremely low (Nb

2O

5: 0-0.17%, avg. 0.036%). This is a phenomenon relatively uncommon in wolframite. In typical wolframite, Nb content is generally higher than Ta content because Nb exhibits geochemical properties more similar to W than Ta does, and Nb

5+ is more likely to substitute for W

6+ than Ta

5+; second, the upper limits of Ta isomorphism in wolframite are Ta

2O

5 (0.3%-0.4%) [

20]. Notably, the Ta content in Dahutang granite-related wolframite significantly exceeds this threshold and Nb content. Additionally, no correlation was observed between Nb/Ta contents in wolframite and rock type or with major elements (W, Fe, Mn). As proposed by Zhang, C.Z. et al. [

21], the Nb and Ta abundances in wolframite are primarily controlled by the concentrations of these ions in the ore-forming fluid during wolframite crystallization. Thus, the Nb-Ta chemical characteristics of wolframite directly reflect the fluid-melt interactions of Mesozoic peraluminous granites.

The Mo of the wolframite in the Dahutang ore cluster has relatively high content ( 0.01%-0.25%, avg. 0.152%MoO3) and substitutes for W6+ in the crystal lattice as the hexavalent state.

5.3. Whole-rock chemistry of Mesozoic granites

Total 22 whole-rock elemental compositions of the Mesozoic granites are analyzed in this study (

Table 4), including 14 G1 granites from the Shimensi mining area and the Kunshan mining area; 8 G2 granites from the Dawutang mining area. 20 previously reported bulk-rock geochemistry are also included for the following discussions (

Table 4). Among them 3 G2 granites from the Shiweidong mining area [

22]; 11 G3 granites from the Dawutang mining area [

23]; 6 G4 granites from the Dawutang mining area [

24].

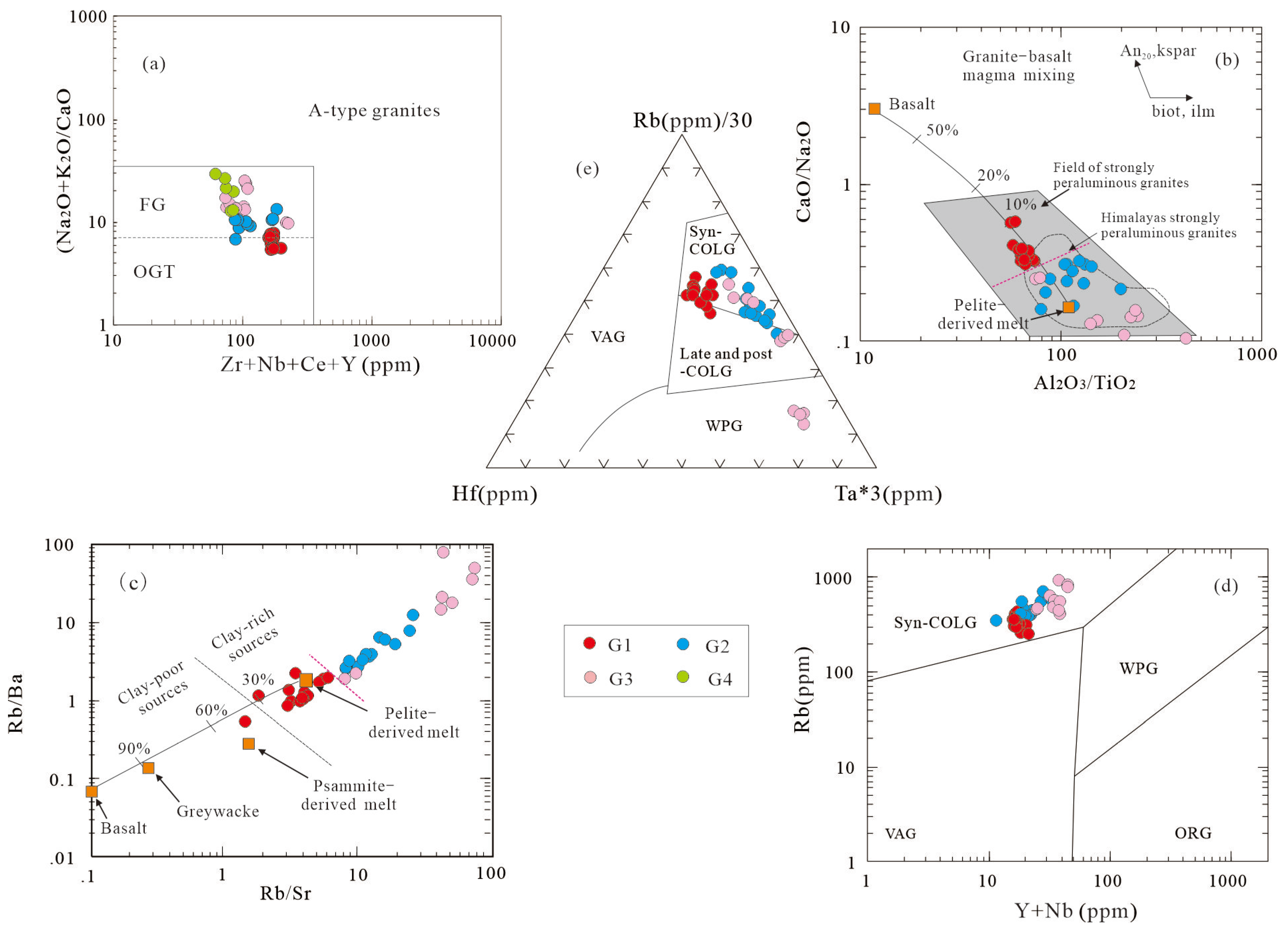

Overall, the Mesozoic granites are characterized by high and variable SiO

2 (70.7%-75.52%), Al

2O

3 (12.92%-16.58 %), low MgO (0.03%-0.54%) and CaO (0.30%-1.34%) (

Table 5). G1 granites have the lowest average MgO and higher abundances of TiO2, TFeO and CaO relative to the G2-G4 granites (

Figure 8a, 8c, 8d and 8g). In the SiO

2 vs. alkali (Na

2O+K

2O) diagrams (

Figure 9a and 9b), most data points plot within the calc-alkaline granite field, but G2-G4 granites have relative highly fractionated trend. All granites are strongly peraluminous, with aluminum saturation indicates ACNK ranging from 1.10 to 1.67, falling within the peraluminous field in the A/NK vs. A/CNK diagram (

Figure 9c). On the harker diagrams, major elements Al

2O

3, MnO, P

2O

5 and K

2O show differing behaviour across the G1 and G2-G4 granites (

Figure 8b, 8e, 8f and 8h). In the G1 granite, the contents of Al

2O

3, MnO, and P

2O

5 remain basically unchanged and do not vary with the MgO content, while the K

2O content is negatively related to MgO. However, in the G2-G4 granites, the contents of Al

2O

3, MnO, and P

2O

5 are negatively related to MgO, whereas the K

2O content is positively related to MgO.

The K/Al versus Na/Al molar ratio diagram (

Figure 9d) was used to characterize at the alteration trends of the Mesozoic peraluminous granites. The logic behind this method is that minimally altered igneous rock samples typically exhibit relatively balanced major element compositions. In contrast, metasomatized rocks display distinct chemical signatures, characterized by the dominance of one or two major elements (e.g., Na, K), which reflect the nature of hydrothermal alteration processes such as albitization, K-feldspathization, muscovitization, or greisenization. Most of the data points plot approximately at the middle region of unaltered granite with Na/Al molar ratios 0.3-0.5 [

29]. The G1 granite exhibits a little greisenization trend which is characterized by low (<0.3) Na/Al molar ratio values for variable K/Al molar ratios (0.1-0.4). The G2-G4 granites show pronounced albitization accompanied by increase in the Na/Al molar ratio (>0.5) and decrease in the K/Al molar ratio (<0.3), exemplified by the G4 granite which is the product of the albitization of G2/G3 granite. The alteration trends revealed by the major element composition of the granite are consistent with the field petrographic observations.

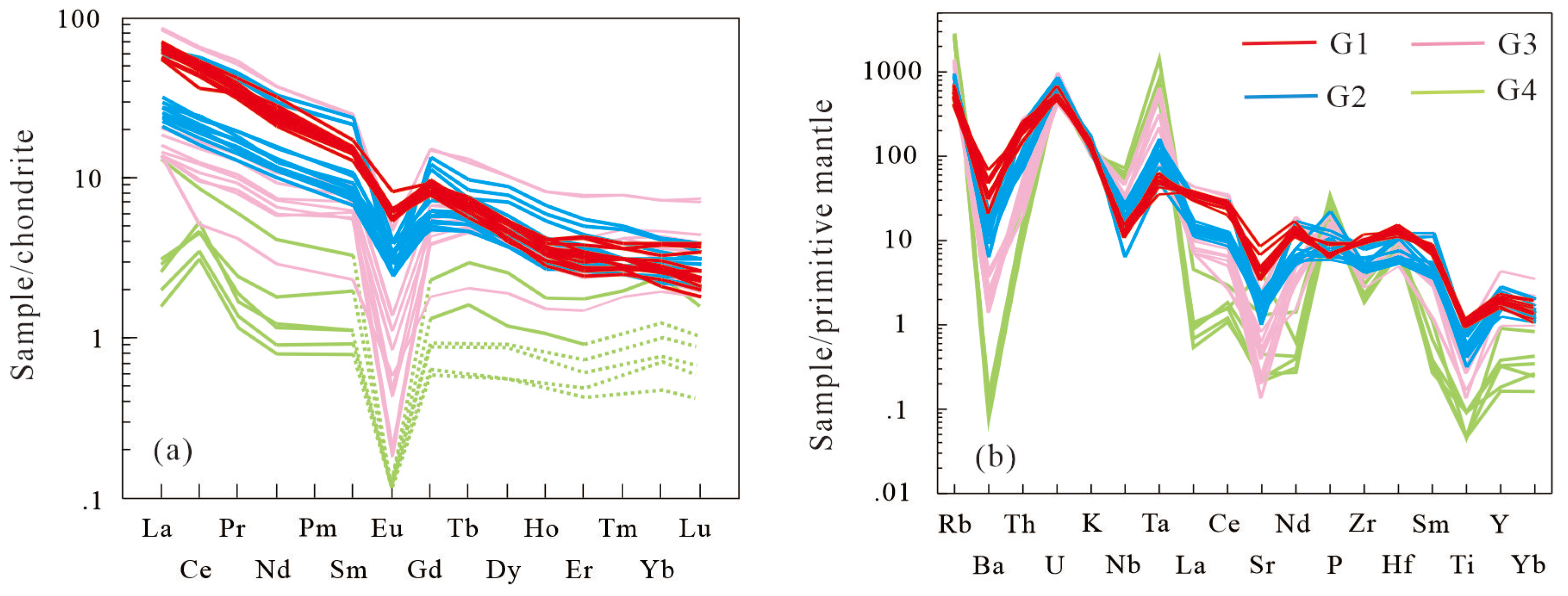

The Mesozoic granites exhibit right-leaning profiles with enrichment in light rare earth elements (LREE), characterized by LREE/HREE fractionation and negative Eu anomalies (

Figure 10). G4 is distinguished by severely Eu-depleted (Eu < 0.05 ppm), and pronounced M-type REE tetrad effects (TE

1,

3 values up to 1.28; [

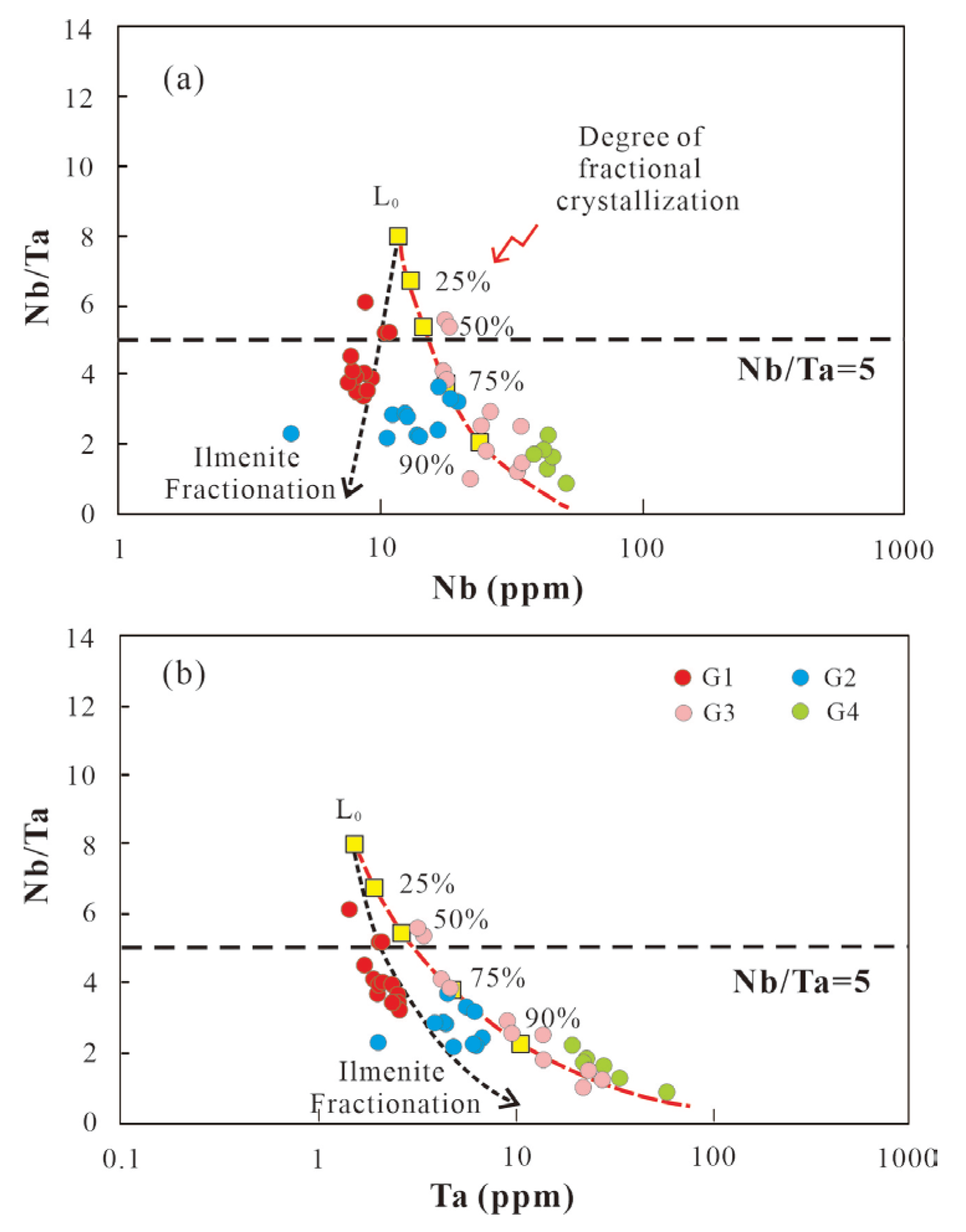

19]). Ba, Sr, Th, U, Zr and the REE are lower and Rb higher in the geochemically evolved G2-G4 granites, which also have stronger Eu anomalies, relative to the G1 granites, sharing the features of those S-type granites. The extremely low Sr and Ba concentrations likely result from intensive fractionation of plagioclase and K-feldspar, which incorporate these elements into their lattices and deplete them from the residual melt. Conversely, Rb—being incompatible in feldspars—accumulates preferentially in the residual melt during fractionation, leading to the high Rb content typical of highly fractionated granites. Notably, Ta and Nb display significant fractionation, with high Ta and low Nb.

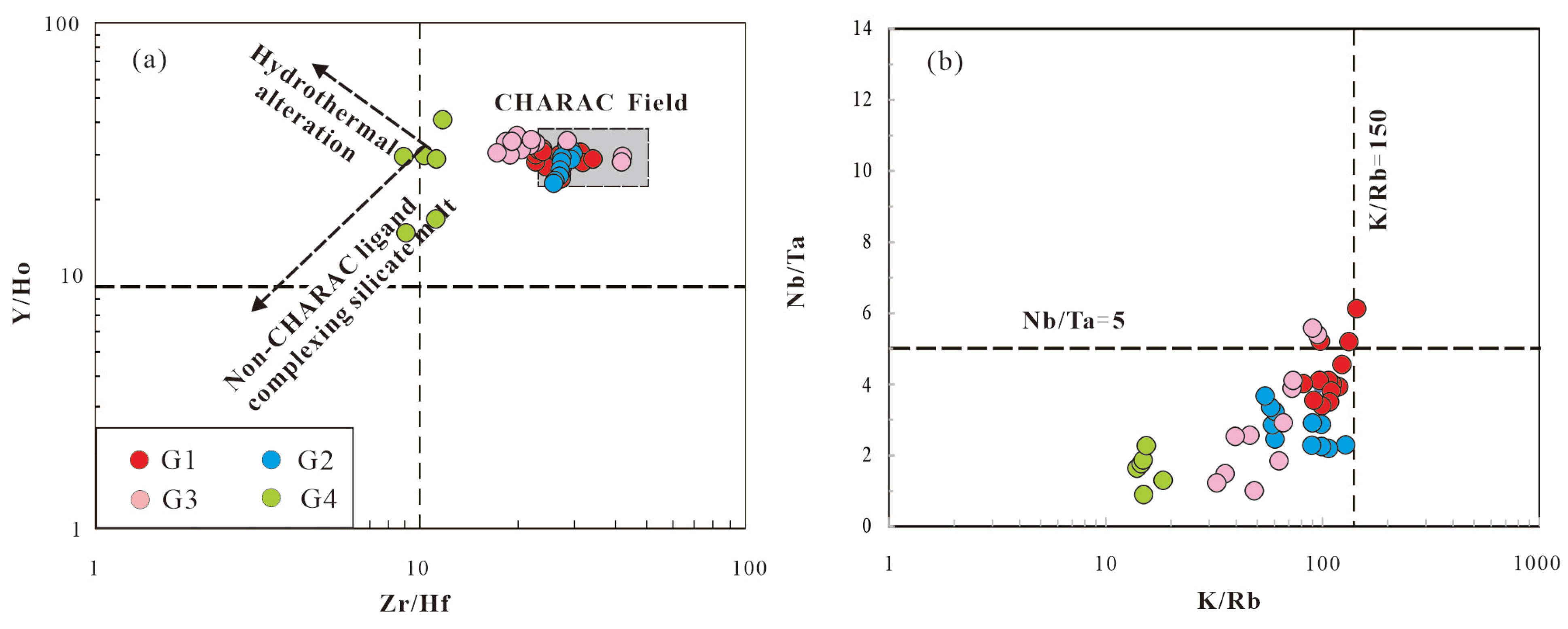

5.4. Characteristics of Zr/Hf, Y/Ho, Nb/Ta, and K/Rb isovalent ratios

In pure magmatic fractionation, isovalent element ratios like Y/Ho and Zr/Hf stay coherent and near chondritic levels, as mineral-melt fractionation depends on ionic substitution in lattices (governed by charge and radius)—termed CHARAC behavior [

31]. By contrast, fluid-driven leaching or precipitation, influenced by elements’ distinct chemical properties, causes non-CHARAC behavior, disrupting coherence between isovalent "twins." Highly evolved, H

2O-Li-P-B-Cl-rich magmas show such unusual non-CHARAC ratios [31, 32].

The Y/Ho ratios in G1–G3 granites range from 23.33 to 35.69, which are close to the chondritic ratio (Y/Ho=28) [

33] (

Table 5;

Figure 11a). In contrast, the Y/Ho ratios in G4 granites (14.8–41.4) deviate slightly from the chondritic ratio, indicating non-CHARAC behavior and a moderately evolved composition. Similarly, the Zr/Hf ratios follow a comparable pattern: in G1, G2, and G3 granites, the Zr/Hf ratios vary between 17.31 and 41.67, whereas in G4 granite, they range from 8.84 to 11.64 (

Table 5;

Figure 11a). The Zr/Hf ratios in G1–G3 granites are close to those of chondrites (the chondritic ratio is 38) [

33], but the Zr/Hf ratio of G4 granite clearly deviates from these values. Breiter et al. [

34] proposed categorizing granites into common granites (Zr/Hf > 55), moderately evolved granites (25 < Zr/Hf < 55), and highly evolved granites (Zr/Hf < 25). It is evident that the G1-G3 granites exhibit a composition that ranges from less to moderately evolved, whereas the G4 granite, characterized by a more highly evolved composition compared to the G1-G3.

Crystallization differentiation (i.e. mica, feldspars) induces a reduction in Nb/Ta and K/Rb ratios. However, fractional crystallization alone is insufficient to explain the occurrence of Nb/Ta<5 and K/Rb<150 in most peraluminous granites. It has been suggested that extremely low Nb/Ta and K/Rb ratios are further intensified by hydrothermal processes during the magmatic-hydrothermal transition, particularly in highly evolved granites [

35].

The Nb/Ta ratios of Mesozoic peraluminous granites in the study area range from 0.89 to 6.11 (

Table 5;

Figure 11b), which intense deviate from the chondritic ratio (chondritic Nb/Ta = 17) [

33]. If Nb/Ta ≤ 5 is taken as an indicator of hydrothermal processes [

35], most Mesozoic granites predominantly fall within the magmatic-hydrothermal field. All studied granite samples exhibit low K/Rb ratios (< 150), indicating a highly evolved magma composition. The K/Rb ratio of magmatic rocks (230) is close to that of chondrites (242) [

33], while most crust-forming rocks have K/Rb ratios ranging from 150 to 350 [

36]. The G1 granite has the highest K/Rb ratios, ranging from 81.77 to 144.15, whereas the G2–G4 granites have lower and more widely varying ratios, ranging from 13.96 to 128.29 (

Table 5;

Figure 11b). Therefore, the low Nb/Ta and K/Rb ratios of the Mesozoic peraluminous granites result from both mineral crystallization fractionation and hydrothermal alteration during the late magmatic sub-solidus stage.

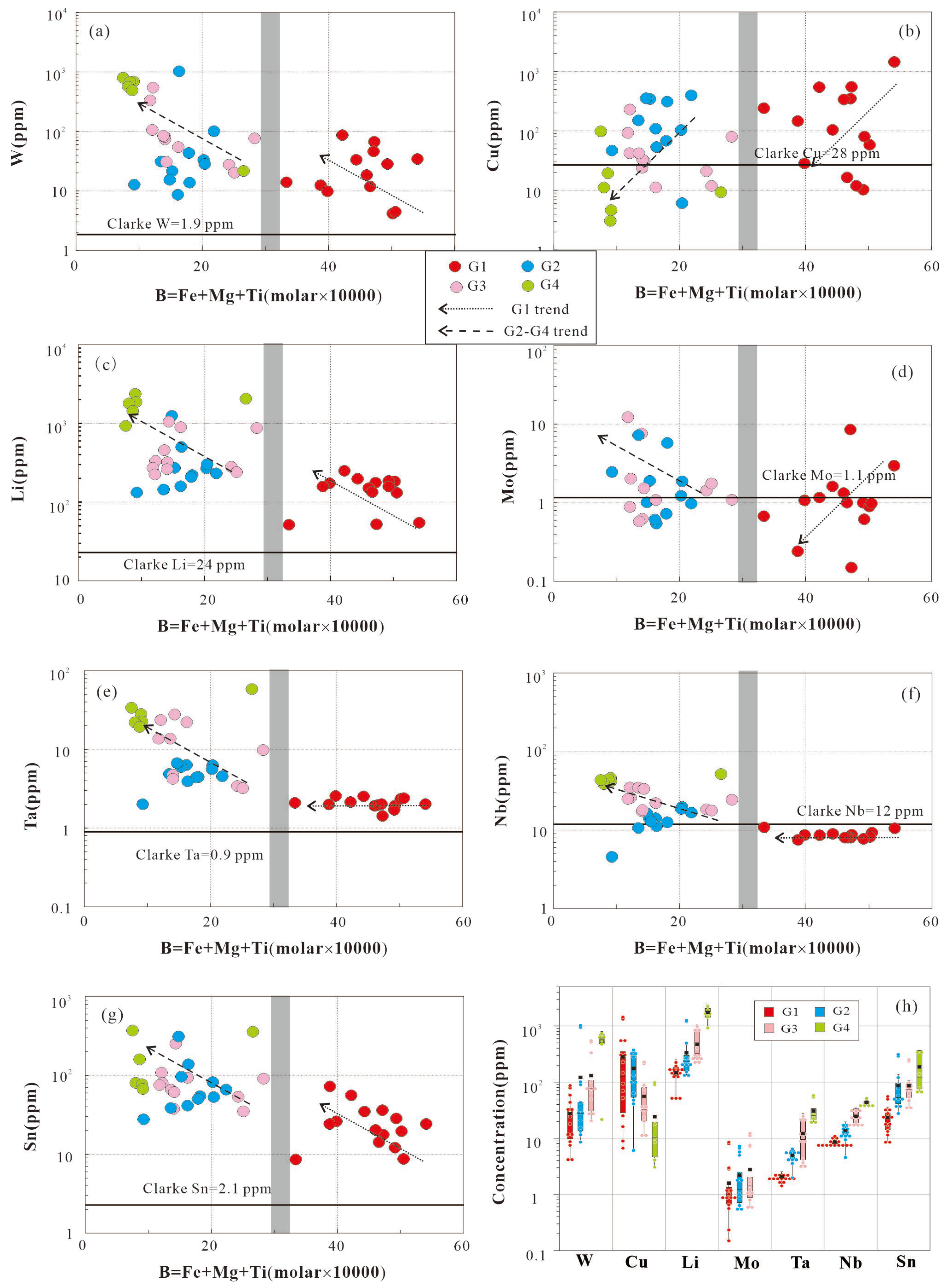

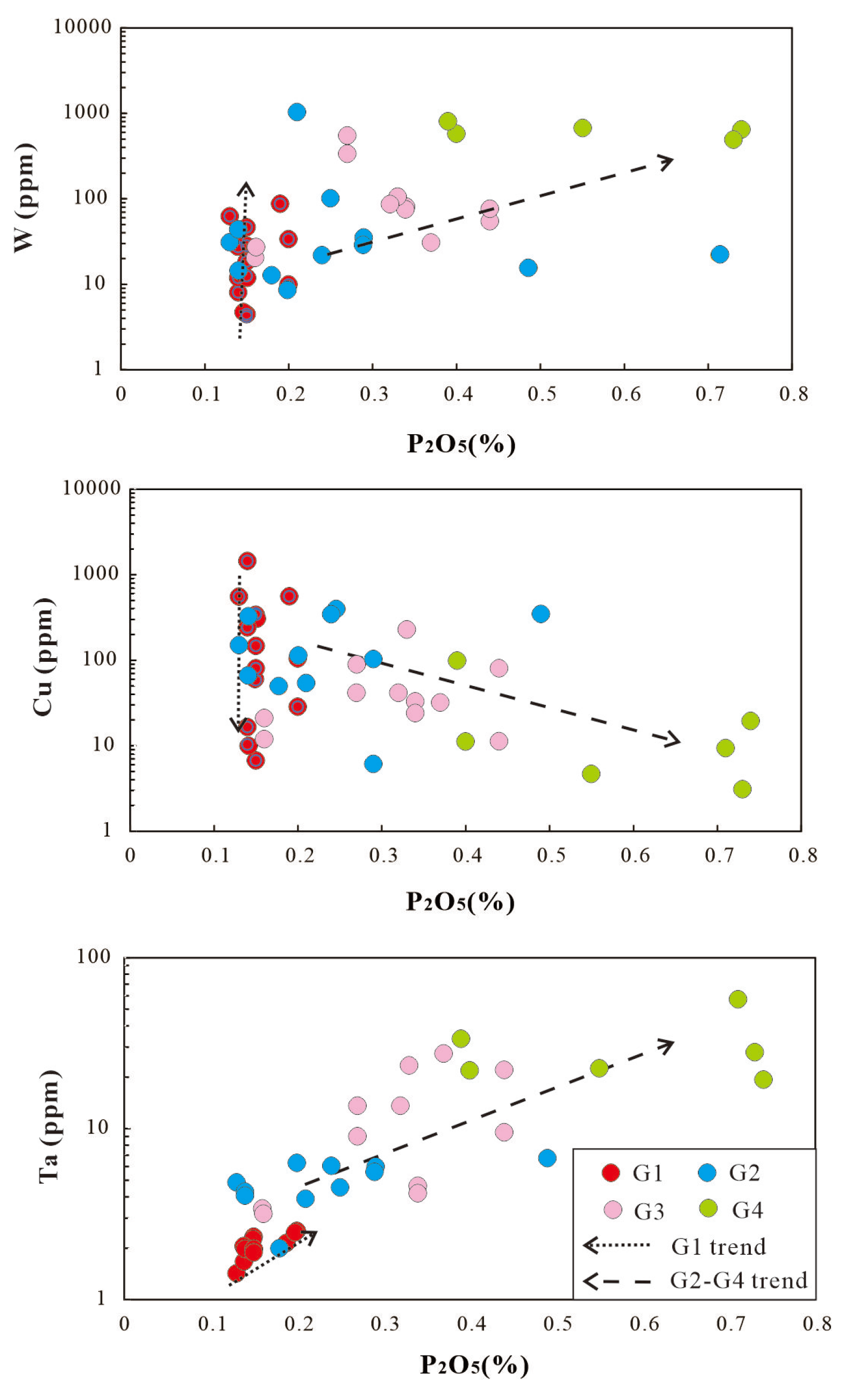

5.5. Characteristics of ore-forming elements

Geochemical data reveal the following concentrations of ore-forming elements in the Mesozoic peraluminous granites of the study area: 4.17–801 ppm of W, 3.07-1443 ppm of Cu, 51.5-2367 ppm of Li, 0.15-12.2 ppm of Mo, 4.45-51.3 ppm of Nb, 1.7-57.9 ppm of Ta, 8.55-369 ppm of Sn (

Table 5). Relative to the upper continental crust (UCC; values from [

37]), the Mesozoic peraluminous granites exhibit strong enrichment in W, Sn, and Li, moderate enrichment in Ta and Cu, and comparable abundances in Sn and Nb. The enrichment sequence of metallogenic elements is: W > Sn > Li > Ta > Cu > Mo > Nb.

On ore-forming element box plots, the G1 granite are characterized by lower abundances of all rare metals, with the exception of Cu. The G2-G4 granite are enriched in W, Li, Sn, Ta and Nb relative to the less G1 granites, with their contents increasing progressively from G2 to G4 granite. G4 granite show significantly enriched abundances of W, Li, Sn, Ta and Nb compared to the G1, G2, and G3 granites (

Figure 12). In contrast, Cu content shows an inverse trend: G1> G2> G3 > G4 granite. Nb content is slightly below UCC in G1 (8.58 ppm).

Using Σ(Fe + Mg + Ti) as a fractionation indicator, where decreasing Σ(Fe + Mg + Ti) indicates increasing degrees of fractionation or a variable source [

38], ore-forming elements exhibit distinct behaviors between the G1 granite and the G2-G4 granites (

Figure 12), which is analogous to the variation pattern of major elements. Nb, Ta, and P increase with fractionation in G2-G4 granites, but remains constant in G1granite. W and Sn are significantly elevated in the G2-G4 granite series relative to G1 granite. Mo shows decreases with fractionation in G1 granite, but increases in G2-G4 granites. Cu shows decreases with fractionation in G1 and G2-G4 granite series. It is evident that the G1 granite and the G2-G4 granites have distinct sources, and the differentiation of the two exerts different influences on ore-forming elements. For W, and Sn, differentiation is conducive to the enrichment of these elements—the higher the degree of differentiation, the greater the enrichment. For Cu, however, differentiation is unfavorable to mineralization, particularly in the G2-G4 granites. As for Li, Nb and Ta, the situation is more complex, with their behaviors varying across different rock types.

6. Discussion

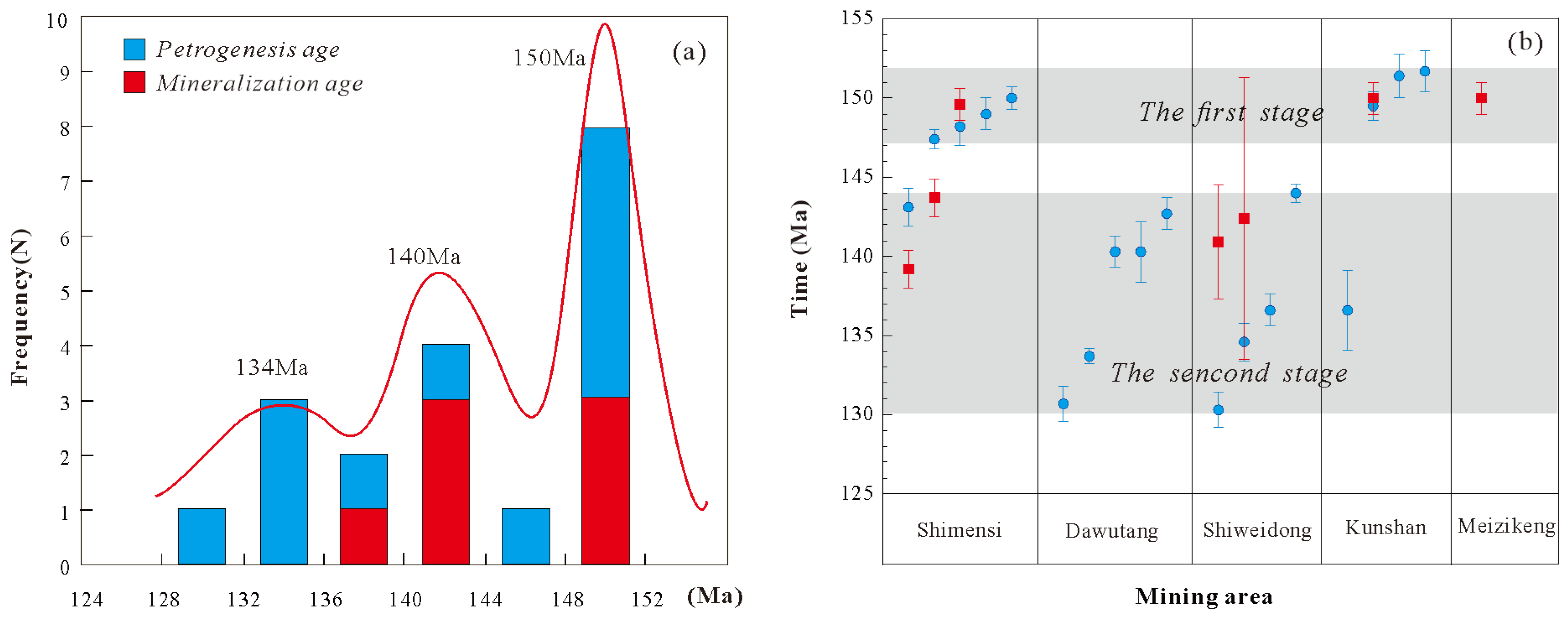

6.1. Spatio-temporal distribution of the Mesozoic peraluminous granites

In the Dahutang ore concentration area, substantial chronological and petrological studies have established a basic consensus that the magmatic activity in this region occurred within the time frame of 130-150 Ma. However, debates persist regarding whether this represents a prolonged single magmatic event or two-stage magmatic activities. We collected recently reported precise ages of the Mesozoic granites as well as the mineralization ages for cross-validation (

Table 6,

Figure 13). Although only a limited number of mineralization ages were available, the diagenetic ages were screened using the following criteria: U content is less than 3000 ppm; each dataset includes at least 15 effective analytical points; and for the same lithology in a single article, the data with the highest testing accuracy are selected. The Mesozoic peraluminous are divided into two periods: 147-152 Ma and 130-144 Ma. Existing mineralization dating efforts have predominantly centered on two time intervals, ~150 Ma and 139-144 Ma (

Table 6 and

Figure 13), which is consistent with magmatic activities.

We have noticed that despite the rigorous selection of age data, the errors in the age data of the two episodes still show systematic differences: the errors of the diagenetic ages of the G1 granite (147-152 Ma) and its associated mineralization ages (~150 Ma) are relatively small, while the errors of the diagenetic ages of the G2-G4 granites (130-144 Ma) and their associated mineralization ages (139-144) Ma are relatively large. The large age errors of the extensive G2-G4 magmatic stage are attributed not only to the limitations of analytical precision but also potentially to the recrystallization of dated minerals caused by magmatic-hydrothermal processes, which results in scattered ages and relatively large errors [

42].

147-152 Ma magmatic activity is characterized by a single lithology (primarily G1), narrow geochemical and time range, implying limited magmatic differentiation; whereas 130-144 Ma magmatic activity consists of complex lithologies (including G2, G3, and G4), and shows diverse compositions and higher-degree evolution in a longer time span. So, though the emplacement of the G1 granite coincides spatially with that of the G2-G4 granites, it is noteworthy that these two episodes of magmatism are not genetically related and evolved independently.

6.2. Implications for magma temperature

Zircon saturation thermometry (TZr) [

43] provides a simple and robust means of estimating magma temperatures. Among all granites, G1 biotite granites have the highest zircon content (100-129 ppm), with calculated T

Zr values between 754 and 795℃ (avg. 766℃) for 14 values (

Table 4). Next is G2, where 11 samples have zircon contents of 49.7-98.3 ppm and calculated T

Zr values of 705-760℃ (avg. 730℃). Third is G3 granite, which exhibits the widest temperature variation range: 11 samples have zircon contents of 31.2-124 ppm and calculated T

Zr values of 678-775℃ (avg. 718℃). The G4 has the lowest temperature, with 6 samples showing zircon contents of 20.6-41.4 ppm and T

Zr values of 645-693℃ (avg. 662℃). Among them, the highly fractionated G4 granite and a few G3 granites, with Zr <45 ppm, severe and obvious depletion of Sr, Eu, and Ba, exhibit lowest saturation temperatures, and their Zr/Hf ratios show obvious non-CHARAC behavior. Their T

Zr values represent only the minimum estimate of temperature rather than the initial magma temperature. 2) Excluding samples of Zr< 45 ppm, the average temperature of G3 granite is 735°C, which is essentially consistent with the temperature of G2 granite (730°C) and differs by 30°C from that of G1 biotite granite 766°C. So, ~766°C and ~735°C reflect the initial magma temperature of G1 granite and G2-G4 granites respectively.

Magma with a temperature of < 800 °C was defined as "cold magma" by Miller, C.F. [

44]. At such a low temperature, mafic minerals and calcic plagioclase are highly insoluble, and melts are near Ab-Or-Qz minimum melt compositions. As a result, the magma contains a large number of residual minerals from the source area, making it almost impossible for the magma to erupt. All current models for generating large-scale magmas at T< 800°C within the crust require a source of water-rich fluid, because anhydrous melts require unrealistically high temperatures, and fluids could ascend into the zone of melting as a consequence of dehydration of underthrust sedimentary rocks or of hydrous mafic silicates in ultramafic-mafic rocks (cf. Thompson, 2001[

45]; Patin˜o Douce, 1999[

46]; Spear, 1995[

47]). In conclusion, it is possible that the dehydration melting of subducted sedimentary rocks in a thickened crust environment gave rise to the low-temperature, high-silica peraluminous, and cryptic granites in the study area.

6.3. Tectonic setting and metallogenic materials

Though the Mesozoic granites exhibit a strongly peraluminous feature (A/CNK >1.1;

Figure 9c), they also possess calc-alkaline affinities and low Zr+Nb +Ce+Y contents (<200 ppm) (

Figure 14a), distinguishing them from the diagnostic features of A-type granites [

48]. Secondly, the studied granites exhibit apparently lower zircon saturation temperatures (<800℃;

Table 4) compared with the typical A-type granites (>820℃). The fractionation of apatite is regarded as one distinctive feature for I- and S-type granites (e.g., Taylor andFallick, 1997[

49]; Li et al., 2007[

50]). G2-G4 granites have high P2O5 contents (mostly >0.2%, albite granite reaches up to 0.75%), and increases with the increase of fractionation in granites (

Figure 12h), indicating that they have S-type affinity. But G1 granite with relatively low P

2O

5 contents (0.13%-0.2%) is more similar to the characteristics of I-type granite.

Sylvester [

51] divided the source rock compositions of strongly peraluminous granites into psammite- and pelite-derived melt based on the CaO/Na

2O value of 0.3 as the boundary. G2-G4 granites are characterized by low CaO/Na

2O values (0.06-0.30), high Rb/Sr (8.1-382.2) and Rb/Ba ratios (1.9-3237;

Figure 14b, 14c), which are similar to the compositions of the Himalayan strongly peraluminous granites. This indicates that they originated from the melting of upper crustal sediments with a high clay component. G1 granite is characterized by relatively high CaO/Na

2O value (0.31-0.57), low Al

2O

3/TiO

2 value, and low Rb/Sr (1.5-5.2) and Rb/Ba ratio (0.54-2.25). The samples are concentrated near the mixing line of basalt melt and pelite melt (

Figure 14b, 14c), which are the products of the mixing of a small amount of basaltic rocks and clay-rich pelitic sediments, showing the characteristics of crust-mantle mixing. The mantle-derived signatures are primarily hosted in the G1 magmas as their elevated thermal state facilitates partial melting of crustal mafic minerals and calcic plagioclase, whereas the G2-G2 magmas exhibits lower and progressively decreasing temperatures, and melt compositions approaching the Ab-Or-Qz minimum. Previous studies [52-53, 13, 22] on the Nd-Hf-O isotopes of the Dahutang Mesozoic granite have also shown that these granites are mainly derived from partial melting of the Proterozoic crust (G2-G4) with minor mantle inputs (G1).

The field relationships, mineralogy and geochemistry data help to define the geodynamic setting of the Mesozoic peraluminous granites. The present study shows that the Mesozoic peraluminous granites is undeformed and unmetamorphosed. It represents the youngest igneous activity in the study area and intruded the subduction-related rocks. These criteria indicate a post-collisional setting for the Mesozoic peraluminous granites. Also, the chemical characteristics of the Mesozoic peraluminous granites are consistent with a post-collisional tectonic setting: marked depletion in Sr, MgO, CaO, and transition metals, primitive mantle-normalized patterns (

Figure 10) enriched in both LILE and HFSE, and no depletion (quite the opposite, in fact) in Nb or Ta. On the tectonic discrimination diagram (

Figure 14d, 14e), all granites fall within the collisional region, indicating they formed in a post-collisional environments.

Shuangqiaoshan Group in the eastern Jiangnan Orogen is formed in a back-arc basin associated with NW-dipping Neoproterozoic oceanic plate subduction beneath the Yangtze Block (

Figure 1b) [

55]. Plausibly, fluids could ascend into the zone of melting as a consequence of dehydration of subduction-related Shuangqiaoshan Group. W-Sn-Li-Nb-Ta partitions strongly into muscovites, which are often the first minerals involved in incongruent melting reactions. If metapelite source micas are also enriched in W-Sn-Li-Nb-Ta, any W-Sn-Li-Ta that is not partitioned into residual minerals during melting will be released to the resultant melt [56, 57]. In fact, Shuangqiaoshan Group are enriched in ore-forming metals, with W, Sn, Cu, Mo, and Ta contents of 10.1, 5.1, 38.5, 2.6, and 36-76 ppm, respectively [58-60], which are one to two orders of magnitude higher than the UCC. One of the reasons for the low Nb content in Mesozoic granites is the low Nb content of the Shuangqiaoshan Group (8-12 ppm, a little lower than UCC); low melting temperature is also an important contributing factor. The host minerals of Nb include muscovite, as well as biotite and Fe-Ti oxides (e.g., Stepanov & Hermann, 2013 [

61]); in a low melting temperature, these minerals do not melt and cause Nb to partition into residual biotite and Fe-Ti oxides.

6.4. The role of fluorine and phosphorus

Although F was not analyzed in this study, it emerges as a key control on the distribution of W, Sn, Nb, Ta in peraluminous Mesozoic granites. Based on previous data, F content shows a moderate increase from approximately 0.1%-0.69% in G2 granites to 0.21%-0.84% in G3-G4 granites [

13]. Elevated F is typical of fractionated peraluminous melts; together with other fluxing elements (e.g. P, Li, B), it lowers the melt temperature and reduced viscosity [

62]. High F concentrations promote the retention of W, Sn, Li, Nb and Ta in low-temperature melts, with these metals preferentially partitioning into the melt during its evolution. This pattern is observed in the G4 granites, which have the highest F contents, also exhibit the highest W, Sn, Li, Nb and Ta concentrations (

Figure 12). No relevant data on F in G1 granites was identified.

Like F, phosphorus accumulates with the fractionation of peraluminous melts, reaching maximum levels in the most evolved granites which also have the lowest Ca contents. When P is present in high concentrations alongside low Ca, a relationship designated the "Pedrobernardo-type" trend by Bea et al. (1992) [

63], P exhibits the behavior of an incompatible element and concentrates in residual fluids. This phenomenon arises because limited Ca availability constrains apatite crystallization. Within G2-G4 granites, P

2O

5 shows a positive correlation with Rb, commonly enriched in residual melts and a negative correlation with compatible elements such as Sr and Ba (

Figure 10). Extending this relationship to rare metals: in G2-G4 S-type granites, P

2O

5 correlates positively with W, Sn, Li, Nb, Ta, and Mo, and negatively with Cu, while no overall trends with Mo; for G1 I-type granites, W, Cu, Li and Sn show no overall trends, while Nb and Ta exhibit a little positive correlation (

Figure 15). The combined effects of F and P, along with Li, favor the retention of W, Sn, Nb, Ta, with no such effect on Cu and Mo in the S-type granitic melt. This enhances the potential for these metals (W, Sn, Nb, Ta) to later partition into exsolving magmatic-hydrothermal fluids. However, in I-type granites fluxing elements have almost no such effect.

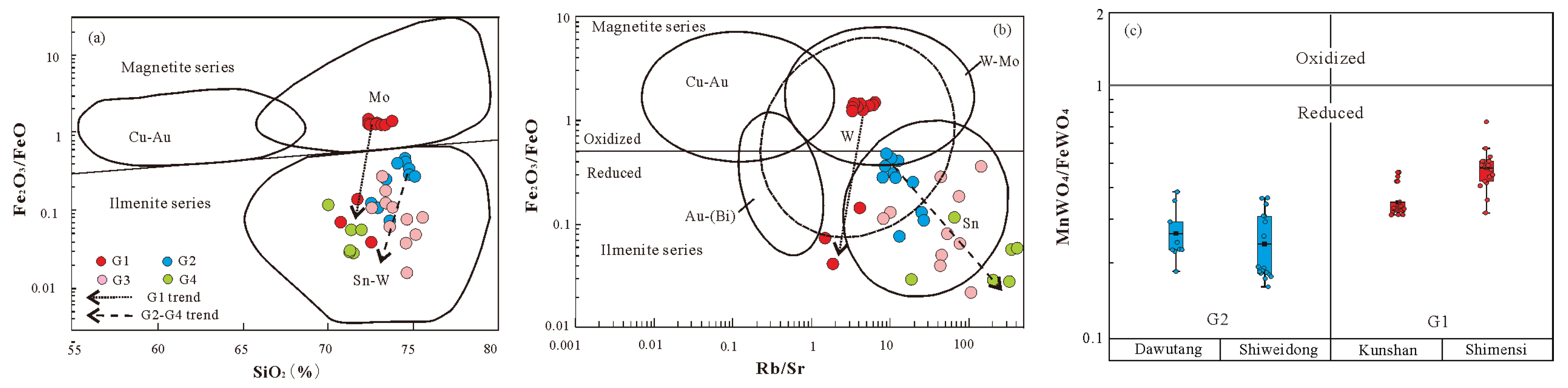

6.5. PH, Eh conditions as indicators of mineralisation

Redox state controls the efficiencies of removal of metal from source into the melt, partition coefficients of metal species to coexisting melt, and transportation of metal into ore-forming fluid [

64]. An empirical redox indicator is the whole-rock Fe

2O

3/FeO ratio (e.g., Blevin, 2004 [

65]). The G1 granite exhibits Fe

2O

3/FeO ratios ranging from 0.04 to 1.47 (avg. 1.07):the 7 samples of the Shimensi mining area range from 1.27 to 1.47 , whereas 3 samples of the Kunshan mining area exhibit significantly lower ratios (0.04-0.14) (

Table 4, Figure16a and 16b). Most samples reflecting an oxidized redox state and relatively high oxygen fugacity and correspond to the magnetite series as defined by Ishihara (1981)[

66]. The G2-G4 granites characterized by Fe

2O

3/FeO ratios of 0.04-0.47 (avg. 0.19), reflect a reduced redox state and low oxygen fugacity, consistent with the ilmenite series (

Table 4, Figure16a, 16b). Nevertheless, as pointed out by Blevin (2004) [

65], for granitic rocks featuring high SiO

2 contents (>72%) and low total FeOT (<2%), the Fe

2O

3/FeO ratios is unsuitable to reveal the magmatic oxygen fugacity. It is necessary to employ alternative methods for determining the redox state.

Previous experimental studies have demonstrated that there is a certain correlation between the contents of FeO and MnO in wolframite and the pH, Eh conditions of formation [67-69]. Wolframite (Fe, Mn)WO

4 is an intermediate member of the complete isomorphous series of ferberite (FeWO

4)- hübnerite (MnWO

4). In a weakly acidic and oxidative environment, iron ions exist as Fe

3+ rather than Fe

2+; this state is unfavorable for their combination with WO

42−, but more favorable for Mn

2+ to combine with WO

42− and form MnWO

4. Consequently, the MnWO

4/FeWO

4 ratio is greater than 1. However, in a weakly alkaline and reductive environment, iron ions in the fluid exist as Fe

2+ rather than Fe

3+; Mn

2+ is gradually replaced as Fe

2+ combines with WO

42− to form FeWO

4, resulting in a MnWO

4/FeWO

4 ratio of less than 1. For the wolframite of G1 granite, the MnWO

4/FeWO

4 ratio ranges from 0.31 to 0.73 (avg. 0.42): Shimensi mining area of 0.32-0.73 (average 0.48); Kunshan mining area of 0.31-0.46 (avg. 0.35). For the wolframite of G2 granite, the MnWO

4/FeWO

4 ratio ranges from 0.16-0.39 (avg. 0.25): Dawutang mining area of 0.17-036 (avg. 0.24); Shiweidong mining area of 0.19-039 (avg. 0.26). The MnWO

4/FeWO

4 ratios of all wolframite are less than 1, indicating they are ferromanganese wolframite and formed in a generally weakly alkaline and relatively reducing environment. However, the MnWO

4/FeWO

4 ratio in the G1 granites is much higher than that in the G2 granites, especially in the Shimensi mining area (

Figure 16c). It indicates that wolframite crystallized in two periods under different environments.

Based on the geochemical characteristics of whole rocks and wolframite, the magmas of both G1 granite and G2-G4 granites are generally in a reduced redox state, but there are still obvious differences between them. The G2-G4 granitic magmas exhibit strong reducibility, which increases with the rise of Rb/Sr ratio from G2 to G4. In contrast, the G1 granite lies between the reduced and oxidized redox states. The reason why G1 granite magma is more oxidative than G2-G4 granite magmas may be that there was an injection of minor mantle materials into its magmatic source area.

The magmatic redox state can play an important role in determining the types of ore deposits produced from magmatic melts by affecting the enrichment processes of the metals. Cu and Mo are sulphophile elements, and its mineralization is generally associated with oxidized magmas [64, 72-73], whereas reduced redox state is beneficial for Sn-Li-Nb-Ta mineralization (

Figure 16a, 16b; e. g., Linnen et al., 2005 [

74]; Zaraisky et al., 2010[

75]). W seems to show little dependence on magmatic redox state because it dissolves predominantly as W6+ at all oxygen fugacities in silicate magma [

76]. However, lower oxygen fugacity is favorable for the removal of tungsten from magma into hydrothermal ore-forming fluids [77-78]. We infer that the G1 magmas have potentials to form minor Cu and Mo mineralization whereas the G2-G4 magmas are favorable for significant W-Sn-Li-Nb-Ta.

6.6. Magmatic evolution, hydrothermal alteration and mineralization

More than one genetic hypothesis have been proposed for the origin of the Mesozoic peraluminous granites in the Dahutang area: (1) melt-fluid interaction origin [

12], (2) fractional crystallization origin [15, 23], and (3) a combination of melt-fluid interaction with fractional crystallization origin [

13].

Both of G1 granite and G2-G4 granites represent different stages of fractionation and late stage fluid-melt interactions which are shown by many geologic, petrographic and chemical observations. Geologically, The formation of hydrothermal cryptoexplosive breccia pipe, pegmatitoid, greisen, and quartz veins in Dahutang area indicates that the parent melts were volatile saturated. Petrographically, exsolution textures represented by perthites, rhythmic zoning of Plagioclase, as well as the turbidity of alkali-feldspars observed in both of them characterize the highly fractionated granites [79-81]. Geochemically, CaO, TiO

2, Sr depletion and higher Al

2O

3 and Na

2O in addition to the strong negative Eu anomalies can be reflect extensive fractionation of biotite and plagioclase, while low Ba can interpret the K-feldspar fractionation [

82] and this is compatible with albite dominance in G2-G4 granites and orthoclase in G1 granite. Both of G1 granite and G2-G4 granites show significant evidence of interaction with fluids, i.e. high contents of Sn (30-10000 ppm), Cs (35-1000 ppm), F (>0.4%-4%), Li (250-2000 ppm), W (10-1000 ppm) and Rb (>500 ppm), with low Nb/Ta (<5) [

35]. Because such incompatible elements have a strong affinity for magmatic fluids, their enrichment is commonly used as a marker of a magmatic-hydrothermal alteration in evolved crustal granites.

Nb/Ta of G1 granite ranges from 3.39-6.11 whereas G2-G4 samples have lower Nb/Ta ratios (0.89-3.66).

Figure 17 illustrates the melt evolution model proposed by Ballouard C [

35]. Those modeling qualitatively reproduces the behaviors of Nb and Ta. According to this model, G1 granite and G2-G4 granites exhibit two distinct mineral fractionation trends in terms of Fe-Ti oxides and micas, respectively. However, both show a high degree of fractionation, ranging from 75% to 90%, to reach low Nb/Ta ratios of 2~4. This unrealistic degree of fractionation suggests the involvement of hydrothermal processes as well. For this reason, the extensive decrease of the Nb/Ta whole-rock values in G2-G4 granites may be enhanced by late magmatic fluids causing secondary muscovitization process [

35].

In the G1 granite, the K/Rb-ratios vary between 81.77 and 144.15 whereas in the G2-G4 granites vary between 13.96 and 128.29. This lower ratio (<150), which is lower ratio than chondritic value (242) [

33], indicates the interaction with an aqueous fluid phase [

83] or growth of mineral in the existence of aqueous fluids [

84] characterizing the evolved magmatic system. The Zr/Hf ratio of G1 granites range from 22.61-34.13 near to the Zr/Hf ratio of chondrite (38) [

33] indicating that G1 may represent the stage of evolution corresponding to the beginning of fluid-melt interaction accompanied by fractionation of biotite and feldspars. Instead, the ratios of Zr/Hf of G2-G4 granites decrease strongly relative to chondrite indicating the later stage of evolution more affected by fluid-melt interaction. Based on the variation characteristics of the Y/Ho and Zr/Hf ratio (influenced solely by magmatic fluids) and the K/Rb and Nb/Ta ratios (influenced by both fractional crystallization and magmatic fluids), We infer that G1 granite represents moderately fractionated melt with the lower effect of magmatic melt-fluid interaction, and G2-G4 granites support intense crystal fractionation and the fluid-mobilization.

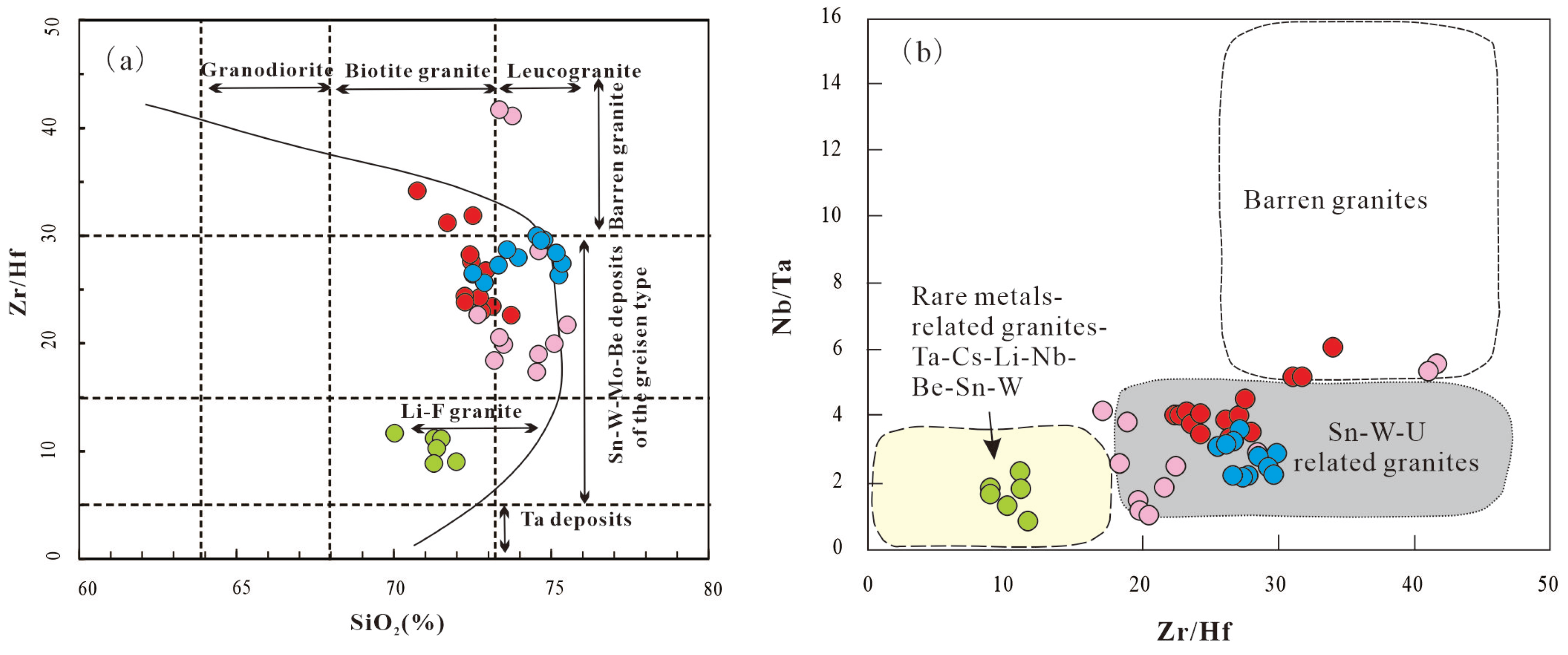

The Zr/Hf ratio serves as a geochemical proxy for the fertility of granitic rocks. Specifically, granites associated with Sn, W, Mo, Be, and Ta mineralization are anticipated to have a Zr/Hf ratio <30 (corresponding to the lower limit of CHARAC range; [

31]), and this characteristic is illustrated in

Figure 18a [

85]. In

Figure 18a, all the Mesozoic peraluminous granites in the Dahutang district have geochemical features distinct from those of barren granites, but similar to those of ore-bearing granites. Among these granites, the G1 granites, characterized by small variations in Zr/Hf ratio (20<Zr/Hf<35), are associated with Sn, W, Mo, and Be mineralization. In contrast, the G2-G4 granites exhibit a large range of Zr/Hf ratio (~10<Zr/Hf<45), which consequently enables them to have a broader mineralization potential—encompassing not only Sn, W, Mo, and Be but also Li and Ta mineralization. Similar, in a Nb/Ta versus Zr/Hf diagram (

Figure 18b), the G1 granite fall into the field of Sn-W-(U)-bearing granites, while G2-G4 granitic series spans two zones: Sn-W-(U)-bearing granites and rare-metalbearing granites (

Figure 18b).

From the perspective of the geochemical properties of elements, tungsten is a crust-loving element, while copper is a mantle-loving element. In the Dahutang orefield, U and Cu are closely associated, with U reaching a super-large scale and Cu reaching a medium-large scale. The cause of the rare metallogenic phenomenon of the close association between U and Cu has long been a subject of discussion (i.e.[5, 10, 24]). If the W-Cu association is a phenomenon formed in a single phase of magma, it is rare and difficult to explain. However, if they are products of different magmas, and only overlap in the ore-hosting space, this can be easily understood. From the diagrams presented in Figures 13, 14, and 16, we highlight significant chronological (147-152 Ma and 130-144 Ma), geochemical (I-type and S-type), redox state, and metallogenic (W-Cu-Mo and W-Sn-Li-Ta mineralization) evidence that each stage granite has its own discrete episodes of magmatism and mineralisation and there is not a all-time fluid source for the mineralisation. The G1 granite and G2-G4 granites have potentially exsolved differ metals and rare metals in differing relative proportions due to the variations source melting conditions and subsequent fractionation. Fractional crystallization and subsolidus hydrothermal alteration together have boosted the solubility and hydrothermal transport capacity of W-Sn-Li-Nb-Ta by multiple orders of magnitude—this effect occurs specifically in the G2-G4 magmas, which are reduced, rich in volatiles, and aqueous. In contrast, the G1 granite magma differs significantly: it is more oxidative and contains fewer volatiles than the G2-G4 suite. When intense crystal fractionation takes place, this G1 magma has the potential to generate W, Cu, and Mo mineralization. Mineral exploration efforts in the Dalutang mining area have, historically, centered mainly on W, Cu, and Mo. Our research, however, leads us to the conclusion that the region holds substantial mineral potential for rare metals—with Sn, Li, and Ta being the key ones. Looking ahead, future surveys ought to give priority to zones neighboring the evolved G2-G4 peraluminous leucogranites, as these areas are promising for discovering new concealed mineral deposits.

7. Conclusions

The Mesozoic peraluminous granites are composite, constructed over 20 Ma. An earlier magmatic stage (152-147 Ma) involved biotite melting of a Proterozoic subducted crustal source, with minor mantle contributions, generating biotite (G1) granites. Sustained collision induced lower-temperature, muscovite-dominated melting, leading to a second major magmatic episode (144-130 Ma) that produced two-mica (G2) granites. Subsequent fractionation yielded muscovite (G3) and albite (G4) granites. This crustal source, enriched in W, Sn, Li, Cu, Mo, and Ta, would have generated melts rich in these elements.

The G1 granite and G2-G4 granites are peralumineous rare metal bearing I- and S-type granites respectively, and formed by fractional crystallization accompanied by varied late magmatic fluid overprint. They share some similarities and greatly vary in other geologic, petrographical and chemical aspects. The G2-G4 granites are more evolved showing numerous evidences of late magmatic fluid-melt interaction as 1) hydrothermal cryptoexplosive breccia pipe, pegmatitoid, and quartz veins, 2) exsolution textures represented by perthites, 3) secondary albite overgrowth on the rim of K-feldspar, 4) rich fluxing elements (e.g. F, P, Li), 5) the low values of K/Rb, Nb/Ta, Zr/Hf and REE tetrad effect of G4 granite declare non-CHARAC behavior causing modification of magmatic trace element abundances by fluid-melt interaction. On the other hand, G1 granite shows few evidences of late-magmatic fluid-melt interaction as 1) hydrothermal cryptoexplosive breccia pipe, pegmatitoid, greisen, and quartz veins, 2) slight replacement of biotite by muscovite, chlorite and iron oxides, 3) K/Rb and Nb/Ta ratios that are lower than those of chondrites but higher than those of G2-G4 granites, 4) chondritic or closely chondritic Zr/Hf and Y/Ho ratios and absence of tetrad effect, indicating the lower imprint of late stage magmatic fluid-melt interaction than G2-G4 granites.

Zr saturation temperatures (< 800°C) indicate that these granites crystallized under shallow, low-temperature, water-rich conditions. In the reduced, volatile-rich aqueous G2-G4 magmas, the solubility and hydrothermal transport capacity of W-Sn-Li-Nb-Ta have been enhanced by multiple orders of magnitude under the combined influence of fractional crystallization and subsolidus hydrothermal alteration. But the G1 granite magma, which is more oxidative and less volatile than G2-G4 granite magmas, potentials to form W, Cu and Mo mineralization accompanied by intense crystal fractionation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M.Y. and M.T.S.; methodology, H.M.Y.; formal analysis, H.M.Y. and L.Z.; investigation, H.M.Y. and C.S.W.; resources, H.M.Y. and M.G.Y.; data curation, H.M.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M.Y.; writing—review and editing, H.M.Y. and M.T.S.; visualization, H.M.Y.; supervision, H.M.Y. and X.L.Z.; project administration, H.M.Y.; funding acquisition, H.M.Y. and M.G.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research was funded by China Geological Survey Project (Grant No. DD202402081 and DD20240067), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 92062223).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The study has benefited from discussions with Chuanlin Zhang and Xianhua Li. The manuscript benefitted greatly from critical reviews by anonymous reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bonin, B. Do coeval mafic and felsic magmas in post-collisional to within-plate regimes necessarily imply two contrasting, mantle and crustal, sources? A review. Lithos 2004, 78, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonin, B. A-type granites and related rocks: evolution of a concept, problems and prospects. Lithos 2007, 97, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X. K, Chen, M.S., Zhan, G.N., Qian, Z.Y.i, Li, H., Xu, J.H. Metallogenic geological conditions of Shimensi tungsten-polymetallic deposit in north Jiangxi province. Contrib. Geol. Miner. Resour. Res. 2012, 27, 143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, X.K. , Wang, P., Sun, D.M., Zhong, B. Re-Os isotopic age of molybdeinte from the Shimensi tungsten polymetallic deposit in northern Jiangxi province and its geological implications. Geol. Bull. China 2013, 32, 1824–1831. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.C. , Jiang, S.Y. Geochronology, geochemistry and petrogenesis of the tungsten-bearing porphyritic granite in the Dahutang tungsten deposit, Jiangxi Province. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2013, 29, 4323–4335. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L. C, Jiang, S.Y. Highly fractionated S-type granites from the giant Dahutang tungsten deposit in Jiangnan Orogen, Southeast China: Geochronology, petrogenesis and their relationship with W-mineralization. Lithos 2014, 202–203, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.H. , Liu, J.J, Mao, J.W., Deng, J., Zhang, F., Meng, X.Y., Xiong, B.K., Xiang, X.K., Luo, X.H. Geochronology and geochemistry of granitoids related to the giant Dahutang tungsten deposit, middle Yangtze River region, China: Implications for petrogenesis, geodynamic setting, and mineralization. Gondwana Res. 2015, 28, 816–836. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.Y. , Peng, N.J., Huang, L.C., Xu, Y.M.g, Zhan, G.L., Dan, X.H. Geological characteristic and ore genesis of the giant tungsten deposits from the Dahutang ore-concentrated district in northern Jiangxi Province. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2015, 31, 639–655. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, H.M. , Zhang, X., Zhu, Y.H. In-situ Monazite U-Pb Geochronology of Granites in Shimensi Tungsten Polymetallic Deposit, Jiangxi Province and its Geological Significance. Geotect. Metallo. 2016, 40, 58–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, K.K. , Chen, B., Deng, J. Biotite in highly evolved granites from the Shimensi W-Cu-Mo polymetallic ore deposit, China: Insights into magma source and evolution. Lithos 2019, 350-351, 105245. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.K. , Hou, Z.Q., Zhang, Z.Y., Mavrogenes, J., Pan, X.F., Zhang, X, Xiang X.K. Metallogenic ages and sulfur sources of the giantDahutang W-Cu-Mo ore field, South China: Constraints frommuscovite 40Ar/39Ar dating and in situ sulfur isotope analyses. Ore Geol. Rev. 2021, 134, 104141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.H. , Zhang, D., Xiang, X.K., Zhu, X.Y., He, X.L. Geology and mineralization of the supergiant Shimensi granitic-type W-Cu-Mo deposit (1.168 Mt) in northern Jiangxi, South China: A Review. China Geol. 2022, 5, 510–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.S. , Pan, X.F., Hou, Z.Q., Deng, Y., Zhang, Z.Y., Fan, X.K., Li, X., Liu, D.W. Petrogenesis and redox state of late Mesozoic granites in the Pingmiao deposit: Implications for the W–Cu–Mo mineralization in the Dahutang district. Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 145, 104898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H. , Li, Z.X., Ge, W.C., Zhou, H.W., Li, W.X., Liu, Y., Wingate, M.T.D. Neoproterozoic granitoids in South China: crustal melting above a mantle plume atnca. 825 Ma? Precambian Res. 2003, 122, 45–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.K. , Chen, B., Chen, J.S., Xiang, X.K. The petrogenesis of the Jiuling granodiorite from the Dahutang deposit, Jiangxi Province and its tectonic implications. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2017, 33, 907–924. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M. Y, Feng, C.Y., Li, D.X., Wang, H., Zhou, J.H., Ye, S.Z., Wang, G.H. Geochronological study of the Kunshan W-Mo-Cu Deposit in the Dahu-tang Area, Northern Jiangxi Province and its geological significance. Geotect. Metallo. 2016, 40, 503–516. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, X.K. , Yin, Q.Q., Zhan, G.N., Qu, K., Liu, X., Tan, R., Zhong, B. Metallogenic conditions and ore-prospecting of Shimensi tungsten ore-section in the North of Dahutang Area in Jiangxi Province. J. Jilin Univ. (Earth Sci. Edi.) 2017, 47, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H. , Yu, N.B., Lu, G.S., Chen, D.K., Dan, X.H. Discovery and Exploration Enlightenment of the Dawutang Extra Large Tungsten Deposit in the Jiangnan Tungsten Mine Belt. South China Geol. 2024, 40, 343–352. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, K.R. User's manual for Isoplot/Ex (rev. 2.49): a geochronological toolkit for Microsoft excel. Berkeley Geochronology Centre: Special Publication 2001; No. 1a, pp. 55.

- Ивoйлoв, A.C. , Qiu, Y.Z. Supplementary information of the form of niobium tantalum in the black tungsten deposit. Geol. Geochem. 1974, 7, 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.Z. Variation in Nb-Ta contents of wolframite and its significance as an indicator. Miner. Deposi. 1984, 3, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.C. , Jiang, S.Y. Highly fractionated S-type granites from the giant Dahutang tungsten deposit in Jiangnan Orogen, Southeast China: geochronology, petrogenesis and their relationship with W-mineralization. Lithos 2014, 202–203, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiangxi Bureau of Geology and Mineral Exploration and Development northwest Jiangxi Brigade. Verification report of tungsten ore resources and reserves in Dawutang mining area, Jing'an County, Jiangxi Province, China, 2016; No published.

- Yang, Y.S. , Pan, X.F., Hou, Z.Q., Deng, Y., Zhang, Z.Y., Fan X.K., Lia, X, Liu, D.W. Petrogenesis and redox state of late Mesozoic granites in the Pingmiao deposit: Implications for the W–Cu–Mo mineralization in the Dahutang district. Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 145, 104898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Maitre, R.W. , Bateman, P., Dudek, A., Keller, J., Lameyre, J., Le Bas, M.J., Sabine, P.A., Schmid, R., Sorensen, H., Streckeisen, A., Wooley, A.R., Zanettin, B. In A classification of igneous rocks and glossary of terms; Blackwell, Oxford, 1989; pp. 193.

- Sylvester, P.J. Post-collisional alkaline granites. J. Geol. 1989, 97, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniar, P.D. , Piccoli, P.M.. Tectonic discrimination of granitoids. Geol. Soc. Amer. Bull. 1989, 101, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, C.R. Molar element ratio analysis of lithogeochemical data: a toolbox for use in mineral exploration and mining. Geochemistry: Exploration, Environment, Analysis 2020, 20, 233–256.

- Harlaux, M. , Blein, O., Ballouard, C., Kontak, D.J., Thi´eblemont, D., Dabosville, A., Gourcerol, B. Geochemical footprints of peraluminous rare-metal granites and pegmatites in the northern French Massif Central and implications for exploration targeting. Ore Geol. Rev. 2025, 176, 106409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.S. , McDonough, W.F. Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanicbasalts: Implications for mantle composition and processes. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1989, 42, 313–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bau, M. Controls on the fractionation of isovalent trace elements in magmatic and aqueous systems: evidence from Y/Ho, Zr/Hf, and lanthanide tetrad effect. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1996, 123, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irber, W. The lanthanide tetrad effect and its correlation with K/Rb, Eu/Eu*, Sr/Eu, Y/Ho, and Zr/Hf of evolving peraluminous granite suites. Geochem. Cosmochim. Acta 1999, 63, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, E. , Grevesse, N. Abundances of the elements: meteoritic and solar. Geochem. Cosmochim. Acta 1989, 53, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiter, K. , Skoda, R., Uher, P. Nb-Ta-Ti-W-Sn oxide minerals as indicators of a peraluminous P- and F-rich granitic systems evolution: Podlesi, Czech Republic. Mineral. Petrol. 2007, 91, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballouard, C. , Poujol, M., Boulvais, P., Branquet, Y., Tart`ese, R., Vigneresse, J. Nb-Ta fractionation in peraluminous granites: a marker of the magmatic-hydrothermal transition. Geology 2016, 44, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. The application of trace element data to problems in petrology. Phys. Chem. Earth 1965, 6, 133–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, R.L. , Gao, S. Composition of the Continental Crust. Treatise on Geochemistry, 2014, 2Nd Edition 4, 1–51. [CrossRef]

- Debon, F. , Le Fort, P. A chemical–mineralogical classification of common plutonic rocks and associations. Trans. R. Soc. Edinburgh: Earth Sci. 1983, 73, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.H. , Cheng, Y.B., Liu, J.J., Yuan, S.D., Wu, S.H., Xiang, X.K., Luo, X.H. Geology and molybdenite Re–Os age of the Dahutang granite-related veinlets-disseminated tungsten ore field in the Jiangxin Province, China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2013, 53, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C. Y, Zhang, D.Q., Xiang, X.K., Li, D.X., Qu, H.Y., Liu, J.N., Xiao, Y. Re-Os isotopic dating of molybdenite from the Dahutang tungsten deposit in northwestern Jiangxi Province and its geological implication. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2012, 28, 3858–3868. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.H. , Zhang, D., Wu, G.G., Luo, P., Chen, X.H., Di, Y.J., Lü, L.J. Re-Os isotopic age of molybdenite from the Meizikeng molybdenite deposit in Northern Jiangxi Province and its geological significance. J. Jilin Univ. (Earth Sci. Edit.) 2013, 43, 1851–1863. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.L. “High-U effect” during SIMS zircon U-Pb dating. Bull. Miner. Petrol. Geochem. 2016, 35, 405–412. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, E.B. , Harrison, T.M. Zircon saturation revisited: Temperature and composition effects in a variety of crustal magma types. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1983, 64, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.F. , McDowell, S.M., Mapes, R.W. Hot and cold granites? Implications of zircon saturation temperatures and preservation of inheritance. Geology 2003, 31, 529–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.B. Partial melting of metavolcanics in amphibolite facies regional metamorphism. J. Earth Sys. Sci. 2001, 110, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patin˜o Douce, A.E. What do experiments tell us about the relative contributions of crust and mantle to the origin of granitic magmas? In Understanding granities: Integrating new and classical techniques; Castro, A., et al., Eds.; Geological Society of London Special Publication: London, 1999; Volume 168, pp. 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Spear, F.S. Metamorphic phase equilibria and pressure-temperature-time paths. Mineralogical Society of America: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp.799.

- Whalen, J. , Currie, K., Chappell, B. A-type granites: geochemical characteristics, discrimination and petrogenesis. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1987, 95, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.P. , Fallick, A.E. The evolution of fluorine-rich felsic magmas: source dichotomy, magmatic convergence and the origins of topaz granite. Terra Nova 1997, 9, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H. , Li, Z.X., Li, W.X., Liu, Y., Yuan, C., Wei, G.J., Qi, C.S. U-Pb zircon, geochemical and Sr–Nd–Hf isotopic constraints on age and origin of Jurassic I- andA-type granites from central Guangdong, SE China: A major igneous event in response to foundering of a subducted flat-slab? Lithos 2007, 96, 186–204. [Google Scholar]

- Sylvester, P.J. , Liegeois, J.P. Post-collisional strongly peraluminous granites. Lithos 1998, 45, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, L. , L´ecuyer, C. Continental recycling: the oxygen isotope point of view. Geochem. Geophys. Geosys. 2005, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W.F. , Shen, N.P., Yan, B., Lai, C., Yang, J.H., Gao, W., Liang, F. Petrogenesis of ore-forming granites with implications for W–mineralization in the super-large Shimensi tungsten-dominated polymetallic deposit in northern Jiangxi Province, South China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2018, 95, 1123–1139. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J.A. Source and settings of granitic rocks. Episodes 1996, 19, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L. , Zhou, J.C., Griffin, W.L., Zhao, G.C., Yu, J.H., Qiu, J.S., Zhang, Y.J., Xing, G. F. Geochemical zonation across a Neoproterozoic orogenic belt: Isotopic evidence from granitoids and metasedimentary rocks of the Jiangnan orogen, China. Precambram Res. 2014, 242, 154–171.

- Harris, N. , Ayres,M., Massey, J. Geochemistry of graniticmelts produced during the incongruent melting of muscovite: implications for extraction of Himalayan leucogranite magmas. J. Geophys. Res. 1995, 100, 15767–15777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, N.B.W. , Inger, S. Trace element modelling of pelite-derived granites. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1992, 110, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J. , Ma, D.S. The geochemical studies of tungsten built in South China. Sci.China B 1982, 10, 939–950. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, D.S. Tantalum-rich Granite Type Deposits in South China. Geological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1996; pp. 147.

- Xu, J. W-bearing sedimentary formations and stratabound W-deposits in Jiangxi Province. Geol. Prospect. 1988, 10, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Stepanov, A.S. , Hermann, J. Fractionation of Nb and Ta by biotite and phengite: implications for the “missing Nb paradox”. Geology 2013, 41, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černŷ, P. , Belvin, P.L., Cuney, M., London, D. Granite-related ore deposits. Economic Geology 2005, 100th Anniversary Volume, 337–370. [Google Scholar]

- Bea, F. , Fershtater, G., Corretgé, L.G. The geochemistry of phosphorus in granite rocks and the effect of aluminium. Lithos 1992, 29, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candela, P.A. , Bouton, S.L. The influence of oxygen fugacity on tungsten and molybdenum partitioning between silicate melts and ilmenite. Econ. Geol. 1990, 85, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blevin, P.L. Redox and compositional parameters for interpreting the granitoid metallogeny of eastern Australia: implications for gold-rich ore systems. Resour. Geol. 2004, 54, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, S. The granitoids series and mineralization. Econ. Geol. 1981, 75th Anniversary Volume, 458–484. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.H. On various features of the chemical composition of wolframites in a tungsten-tin deposit in Jiangxi Province. J. Nanjing Univ. (Natural Sci.) 1982, 1, 133–145. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Y.J. Geochemical types of the vein wolframite deposits in the Nanling region. Geochimica 1982, 2, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B. , Li, W.X., Cai, Y.J. Conditions of formation of wolframite, cassiterite, columbite, microlite and tapiolite and experimental studies on the variation of Nb and Ta in wolframite and cassiterite. Geochimica 1977, 2, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, T. , Pollard, P.J., Mustard, R., Mark, G., Graham, J.L. A comparison of granite-related tin, tungsten, and gold-bismuth deposits: implications for exploration. SEG Newsletter 2005, 61, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Blevin, P.L. , Chappell, B.W. The role of magma sources, oxidation states and fractionation in determining the granite metallogeny of eastern Australia. Trans. Royal Soc. Edinburgh 1992, 83, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillitoe, R.H. Porphyry Copper Systems. Econ. Geol. 2010, 105, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.D. , Huang, R.F., Li H., Hu, Y.B., Zhang, C.C., Sun, S.J., Zhang, L.P., Ding, X., Li, C.Y., Zartman, R.E., Ling, M.X. Porphyry deposits and oxidized magmas. Ore Geol. Rev. 2015, 65, 97–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnen, R.L., Cuney, M. Granite-related rare-element deposits and experimental constraints on Ta-Nb-W- Sn-Zr-Hf mineralization. In Rare-Element Geochemistry and Mineral Deposits; Linnen, R.L., Samson, I.M., Eds.; Geological Association: Canada, 2008; Short Course Notes 17, pp. 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- Zaraisky, G.P. , Korzhinskaya, V., and Kotova, N. Experimental studies of Ta2O5 and columbite–tantalite solubility in fluoride solutions from 300 to 550°C and 50 to100 Mpa. Mineral. Petrol. 2010, 99, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, X.D. , Linnen, R.L., Wang, R.C., Aseri, A., Thibault, Y. Tungsten solubility in evolved granitic melts: An evaluation of magmatic wolframite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2013, 106, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, E. , Keppler, H., Audetat, A. The mobility of W and Mo in subduction zone fluids and the Mo–W–Th–U systematics of island arc magmas. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2012, 351, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candela, P.A. , Bouton, S.L. The influence of oxygen fugacity on tungsten and molybdenum partitioning between silicate melts and ilmenite. Econ. Geol. 1990, 85, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, P.J. Geologic characteristics and genetic problems associated with the development of granite-hosted deposits of tantalum and niobium. In Lanthanides, Tantalum and Niobium; Möller, P., Cerny, P., Saupe, F., Eds.; Springer New York: Berlin Heidelberg, 1989; pp. 240–256. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, M.O. Geochemical criteria for distinguishing magmatic and metasomatic albite-enrichment in granitoids: examples from the Ta–Li granite Yichun (China) and the Sn–W deposit Tikus (Indonesia). Mineral. Deposita 1992, 27, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helba, H. , Trumbull, R.B., Morteani, G., Khalil, S.O., Arslan, A. Geochemical and petrographic studies of Ta mineralization in the Nuweibi albite granite complex, Eastern Desert, Egypt. Miner. Deposita 1997, 32, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. , Sun, D., Huimin, L., Jahn, B., Wilds, S. A-type granites in northeastern China: age and geochemical constraints on their petrogenesis. Chem. Geol. 2002, 187, 143–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.B. The mineralogy of peraluminous granites: a review. Can. Mineral. 1992, 19, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Shearer, C. , Papike, J., Laul, J. Chemistry of potassium feldspars from three zoned pegmatites, Black Hills, South Dakota: implications concerning pegmatite evolution. Geochem. Cosmochim. Acta 1985, 49, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaraisky, G.P. , Aksyuk, A.M., Devyatova, V.N., Udoratina, O.V., Chevychelov, V.Y. The Zr/Hf ratio as a fractionation indicator of rare-metal granites. Petrology 2009, 17, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Geological sketch map of (a) the Jiangnan Orogen and (b) the Dahutang orefield. Age dta of the Mesozoic granites are denoted by symbols: red circle from this study data, blue circle from [5-7, 9, and 16].

Figure 1.

Geological sketch map of (a) the Jiangnan Orogen and (b) the Dahutang orefield. Age dta of the Mesozoic granites are denoted by symbols: red circle from this study data, blue circle from [5-7, 9, and 16].

Figure 2.

Microphotographs (crossed polarizers) of the Dahutang orefield. (a) Biotite (G1) granite. Plagioclase exhibits polysynthetic twinning or rhythmic zoning, with crystal edges showing a serrated shape due to fluid dissolution; (b) Two-mica (G2) granite. Coarse quartz and plagioclase surrounded by fine recrystallized quartz along its boundaries. Orthoclase perthite crystal shows patch perthite type; (c) Two-mica granite. Sericite aggregates replaces K-feldspar, biotite and is replaced by chlorite and opaque minerals; (d) Muscovite granite. Margins of muscovite are bordered and replaced by Li-mica. (Pl= plagioclase; Or= orthoclase; Mcc= microcline; Ms=muscovite; Qz=quartz; Bt=biotite; Ab= albite; Ser=Sericite).

Figure 2.