Submitted:

12 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

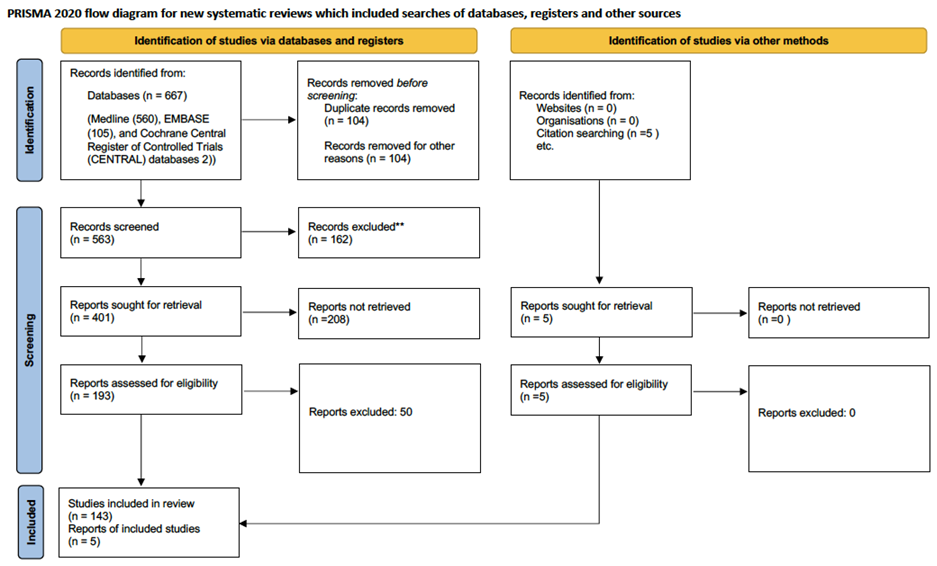

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Ultrasound Measurements of Splanchnic Circulation

3.1.1. B-MODE:

Bowel-Wall Thickening

Venous Congestion

3.1.2. Ecocolordoppler and Spectral Velocity Variations:

PORTAL VEIN:

4. Absent (Aphasic) Portal Venous Flow:

HEPATIC VEINS:

| Intrahepatic veins | Portal vein | Hepatic artery | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Normal |

Triphasic pattern: "a" wave: positive, "a" > "v" "S" wave: negative, "S" > "D" "v" wave: positive; "v" < "a" "D" wave: negative, "D" < "S" |

Anterograde flow Smoothly undulating venous waveforms Systolic speed 16–40 cm/s Pulsatility index > 0.5 |

Maximum systolic speed: 30–60 cm/s Resistive index 0.55–0.7 |

|

Heart failure |

Increased anterograde and retrograde speeds | All cases of hepatic congestion | |

| Increased pulsatility | |||

| Right heart | Higher “a” and “v” waves | ||

| failure | Adequate ratio maintained between S and D waves |

Pulsatility index < 0.5 |

Resistive index > 0.7 |

| High and both positive “a" and "v" waves |

Reduced systolic speed | ||

| Tricuspid regurgitation | Reduced “S” wave “S” wave < “D” wave |

(more common in LC) |

|

| *Severe TR: "S" wave retrograde (“a-S-v complex”) | |||

| Liver cirrhosis |

Loss of triphasic pattern |

Systolic speed <12.8 cm/s till reversal flow and thrombosis |

|

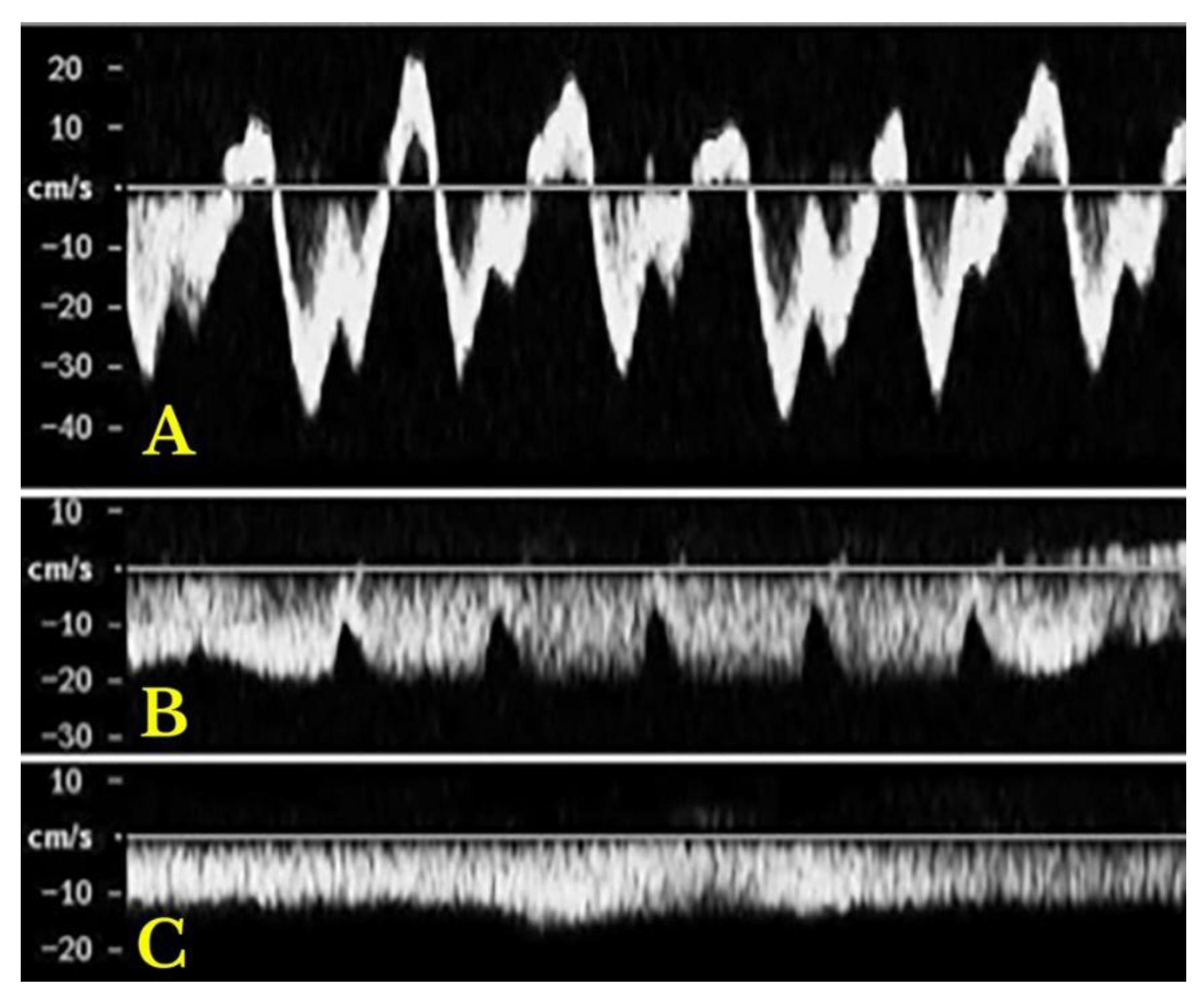

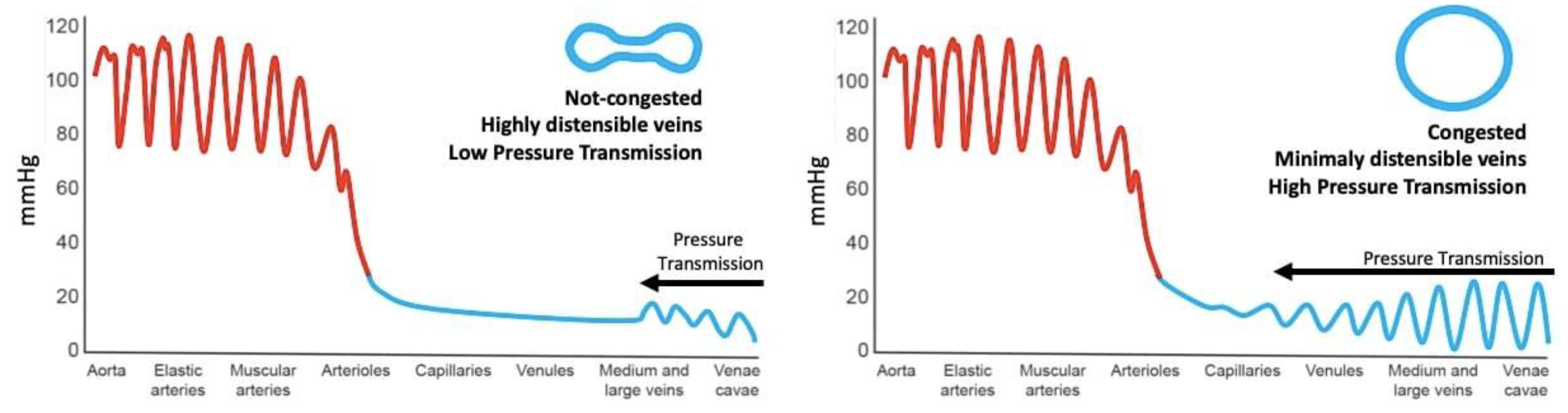

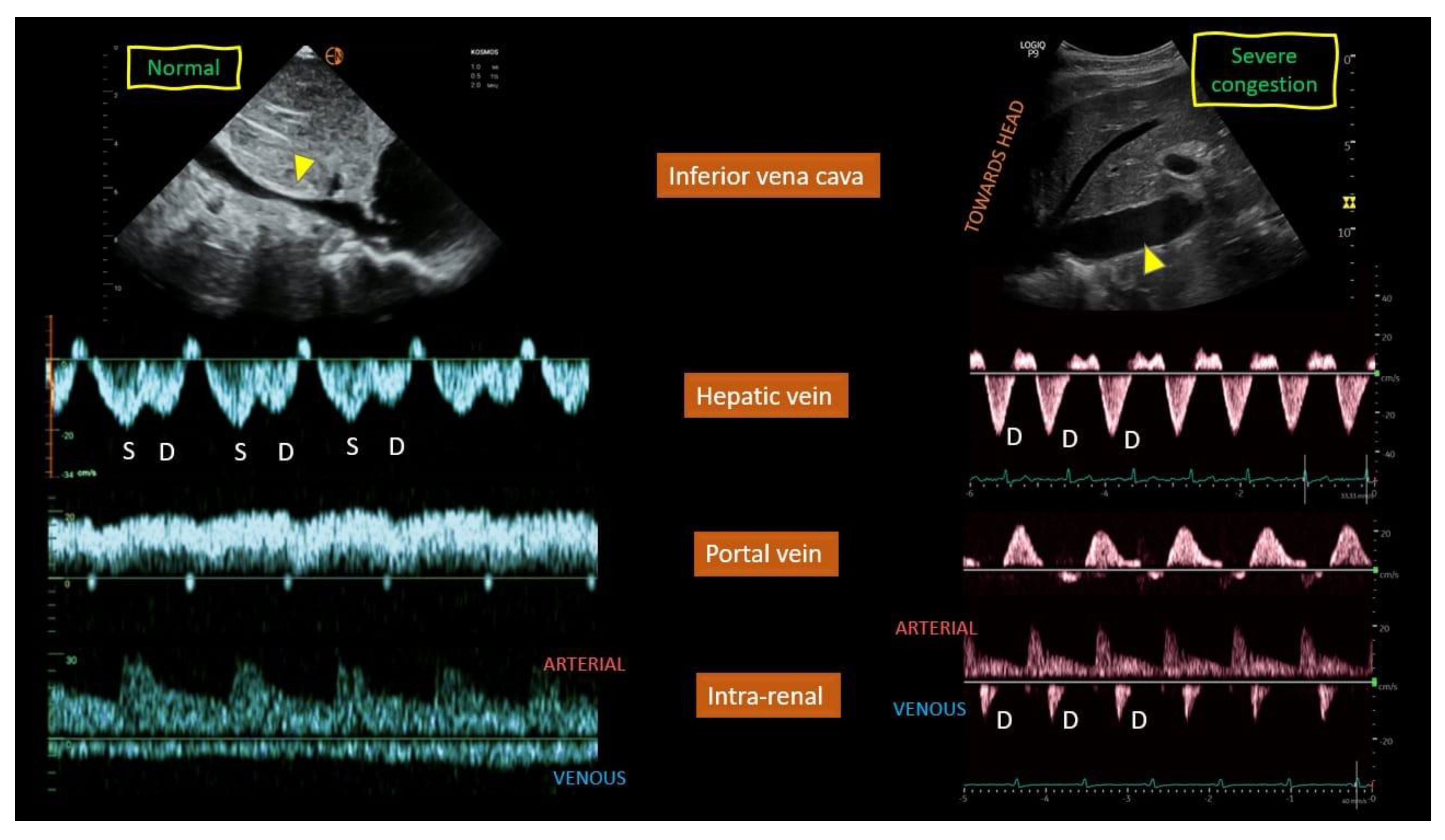

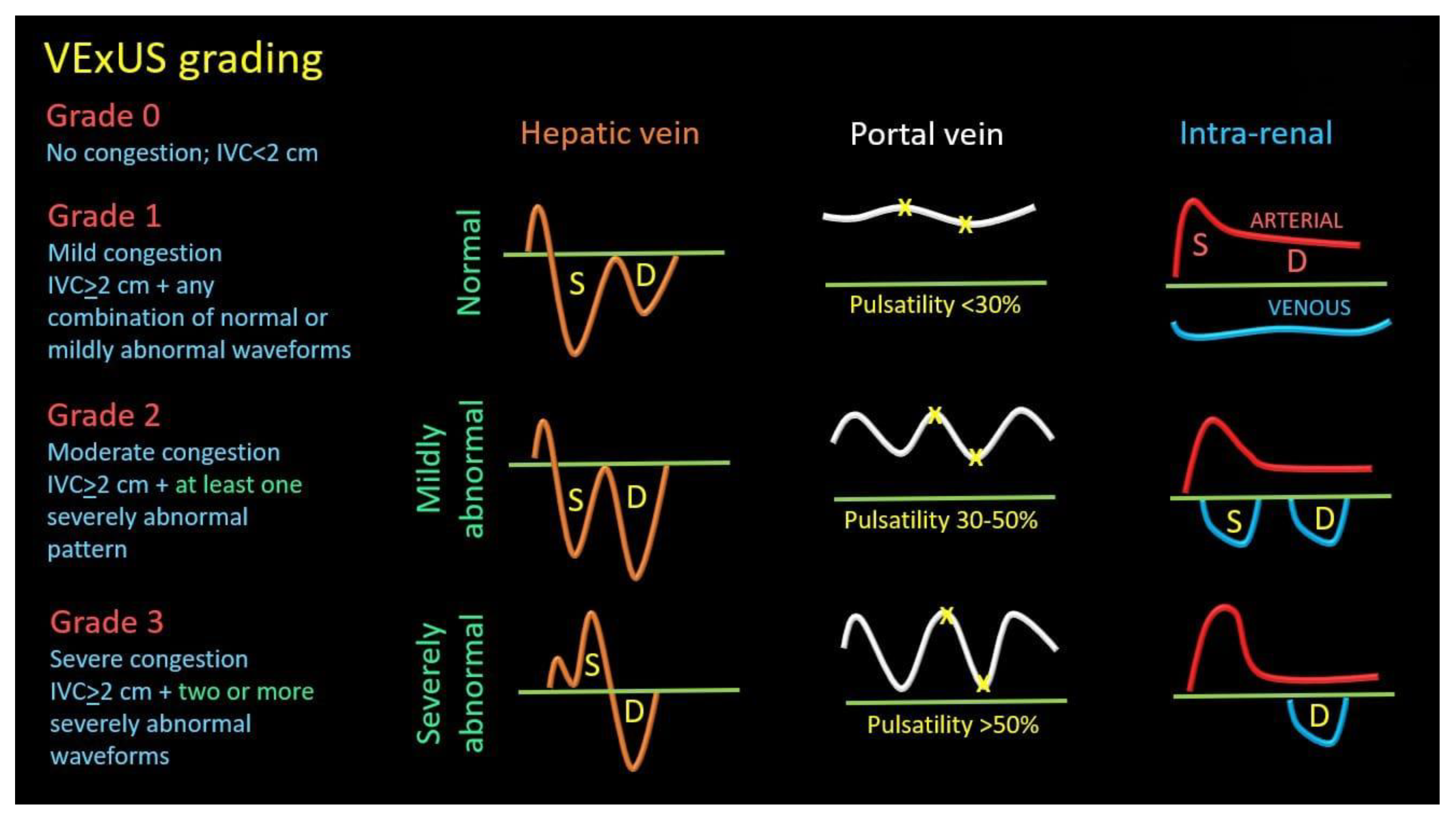

4.1.1. SYNOPSIS OF THE STUDY OF SPLANCHNIC SYSTEM CONGESTION: Venous Excess Ultrasound Score (VExUS) and EXTENDED VEXUS

Extended Venous Ultrasound (eVExUS) as a Complementary Hemodynamic Paradigm

4.1.2. Arterial Hypovascularization

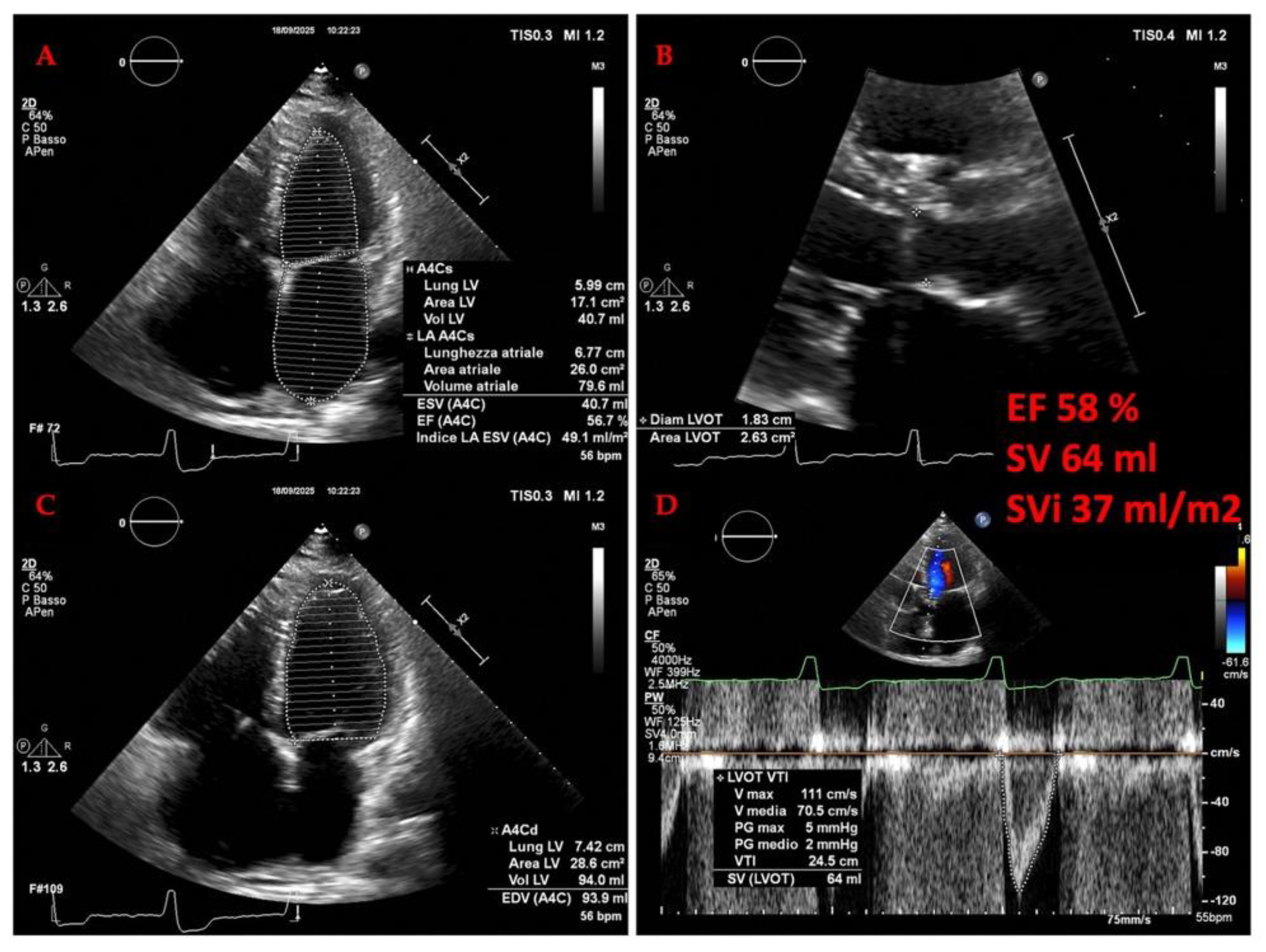

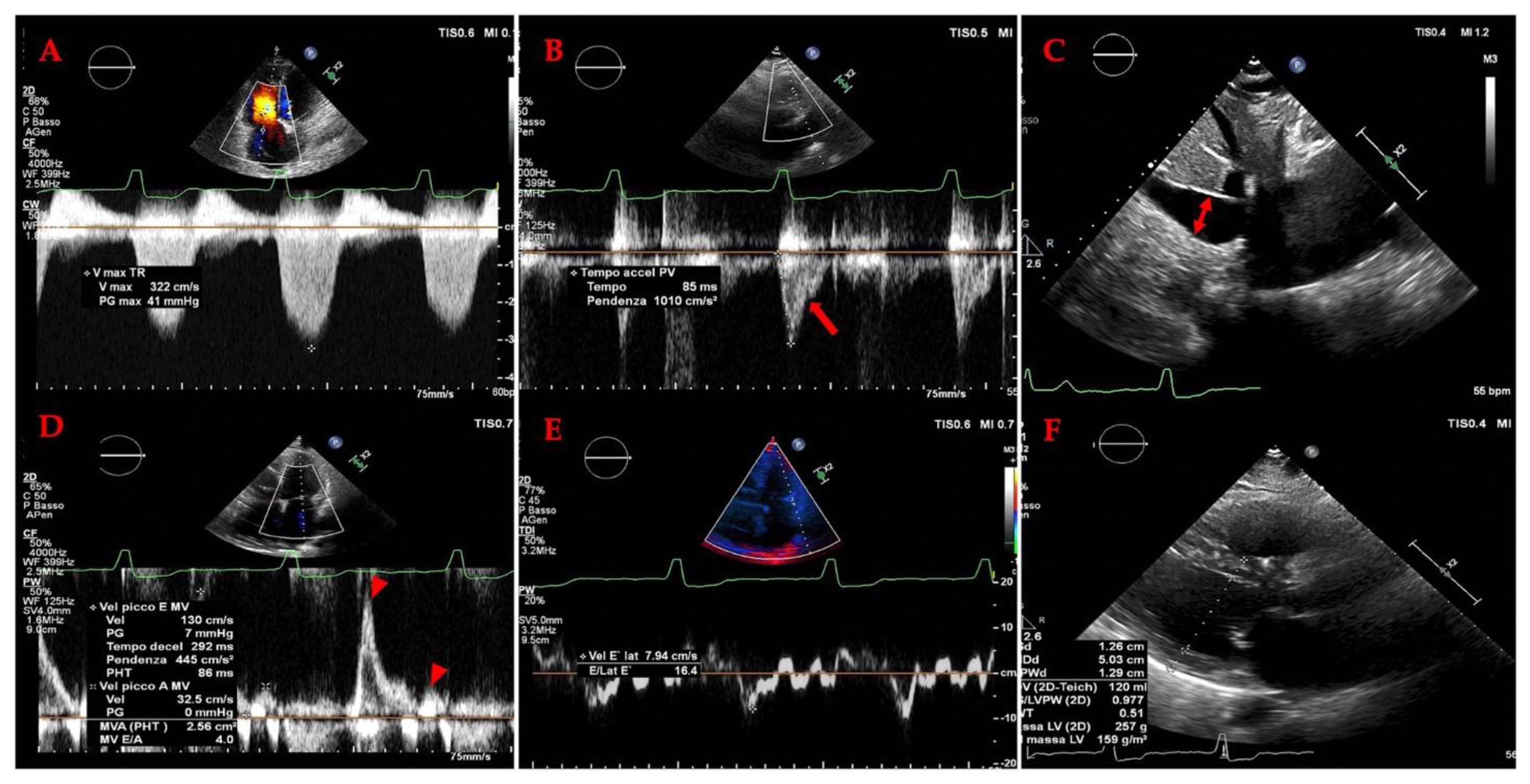

4.2. Cardiac Evaluation: Echocardiography

| Feature | HFpEF | HFrEF | Pulmonary Hypertension |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary dysfunction | Diastolic impairment (impaired relaxation, stiff ventricle) | Systolic impairment (reduced contractility, LVEF ≤40%) | Increased RV afterload due to elevated pulmonary vascular resistance |

| Structural remodeling | Concentric LV hypertrophy, LA enlargement, interstitial fibrosis | Eccentric LV hypertrophy, dilatation, secondary MR | RV hypertrophy (early), RV dilatation (late), septal shift |

| Metabolic features | Impaired substrate flexibility, reduced ketone oxidation [1,2] | Reverse remodeling under SGLT2i/ARNI therapy [5,6] | RV microvascular remodeling (shorter, tortuous vessels, preserved density) [8] |

| Microvascular/Perfusion | Reduced myocardial perfusion reserve, LA functional changes [3] | Partially reversible LV microvascular dysfunction | RV perfusion and microarchitecture linked to coupling [9] |

| Neurohormonal/Inflammatory role | Inflammatory mediators (IL-1R1, fibrosis pathways) [4] | Strong neurohormonal activation (RAAS, sympathetic system) | Endothelial dysfunction, smooth muscle proliferation, in situ thrombosis |

| Imaging markers | Strain analysis shows impaired LA reservoir and LV diastolic strain [3] | Global longitudinal strain improves with therapy [6] | RV strain by MRI/echo, CT-MRI integration improves PH detection [10,11] |

| Reversibility | Limited, comorbidity-driven phenotype | Partially reversible with optimal therapy [7] | Some vascular and RV changes reversible after unloading [8] |

4.2.1. The Evolving Role of Echocardiography OF LEFT HEART in Heart Failure

4.2.2. The Evolving Role of Echocardiography in Heart Failure: A Focus on the Right Heart and Pulmonary Hypertension (PH)

4.2.3. ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY IN ADVANCED HEART FAILURE:

4.3. LUNG ULTRASOUND AND SPLANCHNIC CIRCULATION IN HEART FAILURE

4.3.1. Methodological Principles and Protocols

4.3.2. LUS in the Acute Heart Failure Setting

Diagnostic Application:

Monitoring Therapeutic Efficacy:

Prognostic Stratification:

4.3.3. LUS in the Chronic Ambulatory Heart Failure Setting

4.3.4. LUS During Stress Echocardiography

| POCUS application | Clinical relevance | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| IVC ultrasound | Provides an estimation of | Relatively easy to perform; able to use | Unreliable in many clinical scenarios |

| RAP | handheld ultrasound devices | (e.g., mechanical ventilation, | |

| pulmonary embolism, PH, cardiac | |||

| tamponade, intra-abdominal | |||

| hypertension, chronic TR, athletes); | |||

| unable to distinguish between | |||

| hypovolemia, euvolemia, and high- | |||

| output cardiac states; collapsibility | |||

| influenced by strength of breath | |||

| Internal jugular vein | Provides an estimation of | Relatively easy to perform; able to use | Operator variability (bed angle, |

| ultrasound | RAP | handheld ultrasound devices; useful | transducer pressure, off-axis views); |

| when IVC is inaccessible or unreliable | protocol variability (e.g., column | ||

| (e.g., cirrhosis, obesity) | height, change with Valsalva, | ||

| respiratory variation); incorrect | |||

| assumptions (e.g., RA depth is 5.0 cm) | |||

| Hepatic vein Doppler | Aids in the assessment of | Same window used for assessing the | Need ECG tracing; unreliable in atrial |

| systemic venous | IVC; supplemental information (e.g., | fibrillation, right ventricular systolic | |

| congestion | right ventricular systolic function, | dysfunction, chronic PH, TR, cirrhosis | |

| constriction and tamponade); exhibits | |||

| dynamic change in response to | |||

| decongestive | |||

| treatment | |||

| Portal vein Doppler | Aids in the assessment of | Don’t need ECG; exhibits dynamic | Operator variability (Doppler sampling |

| systemic venous | change in response to decongestive | location); unreliable in athletes (e.g., | |

| congestion | treatment (pulsatility may | pulsatility without high RAP) and | |

| improve even in chronic TR) | cirrhosis (e.g., no pulsatility with high | ||

| RAP or pulsatility due to arterioportal | |||

| shunts) | |||

| Intrarenal venous | Aids in the assessment of | Simultaneous arterial Doppler allows | Technically challenging (especially when |

| Doppler | systemic venous | identification of cardiac cycle; exhibits | patients unable to hold breath); |

| congestion | dynamic change in response to | operator variability (e.g., misinterpret | |

| decongestive treatment | pulsatility of main renal vessel as renal | ||

| parenchymal vessel); change in | |||

| response to decongestive treatment | |||

| may be delayed in the presence of | |||

| interstitial edema; no available data for | |||

| patients with advanced chronic kidney | |||

| disease | |||

| Femoral Vein Doppler (FVD) | Aids in the assessment of | Relatively easy to perform; feasible in | Operator variability (misaligned Doppler |

| systemic venous | patients unable to hold their breath | tracings, overreliance on absolute | |

| congestion | velocities or percent pulsatility); unable | ||

| to rule out venous congestion; | |||

| individual variability (cyclical variation | |||

| limits use of the stasis index) | |||

| Superior vena cava | Aids in the assessment of | Useful when hepatic or renal vessels are | Need ECG tracing; technically |

| Doppler | systemic venous | inaccessible or unreliable (e.g., | challenging transthoracic windows |

| congestion | cirrhosis, advanced kidney disease) | (especially in obese individuals) | |

| Lung ultrasound | Provides an assessment of | Relatively easy to perform; able to use | Operator variability (transducer angle); |

| extravascular lung water | handheld ultrasound devices; may | technically challenging in obese | |

| (e.g., pulmonary edema, | reduce need for serial chest x-ray to | individuals; protocol variability; B lines | |

| pleural effusions) | monitor response to decongestive | lack specificity for pulmonary edema; | |

| treatment | unreliable in preexisting lung disease | ||

| Mitral E/A ratio and E/e’ | Provides an estimation of | Reproducible; prognostic; useful to | Unreliable in many clinical scenarios |

| ratio | left atrial pressure | distinguish cardiogenic versus | (e.g., atrial fibrillation; mitral annular |

| noncardiogenic pulmonary edema | calcification; mitral valve and | ||

| pericardial disease); operator | |||

| variability | |||

| (Doppler cursor angle; sample volume placement); indeterminate E/e’ values are common | |||

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

References

- Chen-Izu, Y.; Banyasz, T.; Shaw, J.A.; Izu, L.T. The Heart is a Smart Pump: Mechanotransduction Mechanisms of the Frank-Starling Law and the Anrep Effect. Annu Rev Physiol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Swenne, C.A.; Shusterman, V. Neurocardiology: Major mechanisms and effects. J Electrocardiol 2024, 88, 153836. [CrossRef]

- Manolis, A.A.; Manolis, T.A.; Manolis, A.S. Neurohumoral Activation in Heart Failure. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, S.W.; Piper, H.; Starling, E.H. The regulation of the heart beat. The Journal of physiology 1914, 48, 465-513. [CrossRef]

- Nichols, C.G.; Hanck, D.A.; Jewell, B.R. The Anrep effect: an intrinsic myocardial mechanism. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 1988, 66, 924-929. [CrossRef]

- Hornby-Foster, I.; Richards, C.T.; Drane, A.L.; Lodge, F.M.; Stembridge, M.; Lord, R.N.; Davey, H.; Yousef, Z.; Pugh, C.J.A. Resistance- and endurance-trained young men display comparable carotid artery strain parameters that are superior to untrained men. Eur J Appl Physiol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Herring, N.; PATERSON, D. Haemodynamics: flow, pressure and resistance. In Levick's Introduction to Cardiovascular Physiology, Herring, N., PATERSON, D., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2018.

- O'Rourke, M.F.; Hashimoto, J. Mechanical factors in arterial aging: a clinical perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007, 50, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Laurent, S.; Cockcroft, J.; Van Bortel, L.; Boutouyrie, P.; Giannattasio, C.; Hayoz, D.; Pannier, B.; Vlachopoulos, C.; Wilkinson, I.; Struijker-Boudier, H.; et al. Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur Heart J 2006, 27, 2588-2605. [CrossRef]

- Vanhoutte, P.M.; Shimokawa, H.; Tang, E.H.; Feletou, M. Endothelial dysfunction and vascular disease. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2009, 196, 193-222. [CrossRef]

- Schiffrin, E.L. Vascular remodeling in hypertension: mechanisms and treatment. Hypertension 2012, 59, 367-374. [CrossRef]

- Shirwany, N.A.; Zou, M.H. Arterial stiffness: a brief review. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2010, 31, 1267-1276. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, G.F. Arterial stiffness and hypertension. Hypertension 2014, 64, 13-18. [CrossRef]

- Guyton, A.C.; Polizo, D.; Armstrong, G.G. Mean circulatory filling pressure measured immediately after cessation of heart pumping. Am J Physiol 1954, 179, 261-267. [CrossRef]

- Versprille, A.; Jansen, J.R. Mean systemic filling pressure as a characteristic pressure for venous return. Pflugers Arch 1985, 405, 226-233. [CrossRef]

- Guyton, A.C.; Lindsey, A.W.; Abernathy, B.; Richardson, T. Venous return at various right atrial pressures and the normal venous return curve. Am J Physiol 1957, 189, 609-615. [CrossRef]

- Aya, H.D.; Cecconi, M. Mean Systemic Filling Pressure Is an Old Concept but a New Tool for Fluid Management. In Perioperative Fluid Management; 2016; pp. 171-188.

- Spiegel, R. Stressed vs. unstressed volume and its relevance to critical care practitioners. Clin Exp Emerg Med 2016, 3, 52-54. [CrossRef]

- Rosenblum, J.D.; Boyle, C.M.; Schwartz, L.B. The mesenteric circulation. Anatomy and physiology. Surg Clin North Am 1997, 77, 289-306. [CrossRef]

- NETTER, F.H. Overview of lower digestive tract. In Netter Collection of Medical Illustrations: Digestive System, Part II – Lower Digestive Tract; Elsevier, Inc: 2025; Volume II, pp. 1-30.

- Yaku, H.; Fudim, M.; Shah, S.J. Role of splanchnic circulation in the pathogenesis of heart failure: State-of-the-art review. J Cardiol 2024, 83, 330-337. [CrossRef]

- Rutlen, D.L.; Supple, E.W.; Powell, W.J., Jr. The role of the liver in the adrenergic regulation of blood flow from the splanchnic to the central circulation. The Yale journal of biology and medicine 1979, 52, 99-106.

- Parks, D.A.; Jacobson, E.D. Physiology of the splanchnic circulation. Arch Intern Med 1985, 145, 1278-1281.

- Mocan, D.; Lala, R.I.; Puschita, M.; Pilat, L.; Darabantiu, D.A.; Pop Moldovan, A. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.L. Congestion/decongestion in heart failure: what does it mean, how do we assess it, and what are we missing?-is there utility in measuring volume? Heart Fail Rev 2024, 29, 1187-1199. [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Gracia, J.; Demissei, B.G.; Ter Maaten, J.M.; Cleland, J.G.; O'Connor, C.M.; Metra, M.; Ponikowski, P.; Teerlink, J.R.; Cotter, G.; Davison, B.A.; et al. Prevalence, predictors and clinical outcome of residual congestion in acute decompensated heart failure. International journal of cardiology 2018, 258, 185-191. [CrossRef]

- Lala, A.; McNulty, S.E.; Mentz, R.J.; Dunlay, S.M.; Vader, J.M.; AbouEzzeddine, O.F.; DeVore, A.D.; Khazanie, P.; Redfield, M.M.; Goldsmith, S.R.; et al. Relief and Recurrence of Congestion During and After Hospitalization for Acute Heart Failure: Insights From Diuretic Optimization Strategy Evaluation in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure (DOSE-AHF) and Cardiorenal Rescue Study in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure (CARESS-HF). Circ Heart Fail 2015, 8, 741-748. [CrossRef]

- Drazner, M.H.; Hellkamp, A.S.; Leier, C.V.; Shah, M.R.; Miller, L.W.; Russell, S.D.; Young, J.B.; Califf, R.M.; Nohria, A. Value of clinician assessment of hemodynamics in advanced heart failure: the ESCAPE trial. Circ Heart Fail 2008, 1, 170-177. [CrossRef]

- Narang, N.; Chung, B.; Nguyen, A.; Kalathiya, R.J.; Laffin, L.J.; Holzhauser, L.; Ebong, I.A.; Besser, S.A.; Imamura, T.; Smith, B.A.; et al. Discordance Between Clinical Assessment and Invasive Hemodynamics in Patients With Advanced Heart Failure. J Card Fail 2020, 26, 128-135. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E.J.; Blaha, M.J.; Chiuve, S.E.; Cushman, M.; Das, S.R.; Deo, R.; de Ferranti, S.D.; Floyd, J.; Fornage, M.; Gillespie, C.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017, 135, e146-e603. [CrossRef]

- Ostrominski, J.W.; DeFilippis, E.M.; Bansal, K.; Riello, R.J., 3rd; Bozkurt, B.; Heidenreich, P.A.; Vaduganathan, M. Contemporary American and European Guidelines for Heart Failure Management: JACC: Heart Failure Guideline Comparison. JACC Heart Fail 2024, 12, 810-825. [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, B.; Coats, A.J.S.; Tsutsui, H.; Abdelhamid, C.M.; Adamopoulos, S.; Albert, N.; Anker, S.D.; Atherton, J.; Bohm, M.; Butler, J.; et al. Universal definition and classification of heart failure: a report of the Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Heart Failure Society and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition of Heart Failure: Endorsed by the Canadian Heart Failure Society, Heart Failure Association of India, Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand, and Chinese Heart Failure Association. European journal of heart failure 2021, 23, 352-380. [CrossRef]

- Authors/Task Force, M.; McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Bohm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Celutkiene, J.; et al. 2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. European journal of heart failure 2024, 26, 5-17. [CrossRef]

- Fudim, M.; Neuzil, P.; Malek, F.; Engelman, Z.J.; Reddy, V.Y. Greater Splanchnic Nerve Stimulation in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021, 77, 1952-1953. [CrossRef]

- Galie, N.; Humbert, M.; Vachiery, J.L.; Gibbs, S.; Lang, I.; Torbicki, A.; Simonneau, G.; Peacock, A.; Vonk Noordegraaf, A.; Beghetti, M.; et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J 2016, 37, 67-119. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, M.; Chen, T.; Zhou, Y. Correlation Between Liver Stiffness and Diastolic Function, Left Ventricular Hypertrophy, and Right Cardiac Function in Patients With Ejection Fraction Preserved Heart Failure. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021, 8, 748173. [CrossRef]

- Samsky, M.D.; Patel, C.B.; DeWald, T.A.; Smith, A.D.; Felker, G.M.; Rogers, J.G.; Hernandez, A.F. Cardiohepatic interactions in heart failure: an overview and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013, 61, 2397-2405. [CrossRef]

- Pieske, B.; Tschope, C.; de Boer, R.A.; Fraser, A.G.; Anker, S.D.; Donal, E.; Edelmann, F.; Fu, M.; Guazzi, M.; Lam, C.S.P.; et al. How to diagnose heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the HFA-PEFF diagnostic algorithm: a consensus recommendation from the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European journal of heart failure 2020, 22, 391-412. [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; Allen, L.A.; Byun, J.J.; Colvin, M.M.; Deswal, A.; Drazner, M.H.; Dunlay, S.M.; Evers, L.R.; et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022, 79, e263-e421. [CrossRef]

- Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Ferreira, J.P.; Bocchi, E.; Bohm, M.; Brunner-La Rocca, H.P.; Choi, D.J.; Chopra, V.; Chuquiure-Valenzuela, E.; et al. Empagliflozin in Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med 2021, 385, 1451-1461. [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.D.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Claggett, B.; de Boer, R.A.; DeMets, D.; Hernandez, A.F.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Lam, C.S.P.; Martinez, F.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med 2022, 387, 1089-1098. [CrossRef]

- Schwinger, R.H.G. Pathophysiology of heart failure. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2021, 11, 263-276. [CrossRef]

- Tanai, E.; Frantz, S. Pathophysiology of Heart Failure. Compr Physiol 2015, 6, 187-214. [CrossRef]

- Yancy, C.W.; Jessup, M.; Bozkurt, B.; Butler, J.; Casey, D.E., Jr.; Drazner, M.H.; Fonarow, G.C.; Geraci, S.A.; Horwich, T.; Januzzi, J.L.; et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2013, 128, 1810-1852. [CrossRef]

- Greene, S.J.; Bauersachs, J.; Brugts, J.J.; Ezekowitz, J.A.; Lam, C.S.P.; Lund, L.H.; Ponikowski, P.; Voors, A.A.; Zannad, F.; Zieroth, S.; et al. Worsening Heart Failure: Nomenclature, Epidemiology, and Future Directions: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023, 81, 413-424. [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Jimenez, S.; Garcia Sebastian, C.; Vela Martin, P.; Garcia Magallon, B.; Martin Centellas, A.; de Castro, D.; Mitroi, C.; Del Prado Diaz, S.; Hernandez-Perez, F.J.; Jimenez-Blanco Bravo, M.; et al. Prevalence and prognostic impact of subclinical venous congestion in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2025. [CrossRef]

- Saadi, M.P.; Silvano, G.P.; Machado, G.P.; Almeida, R.F.; Scolari, F.L.; Biolo, A.; Aboumarie, H.S.; Telo, G.H.; Donelli da Silveira, A. Modified VExUS: A Dynamic Tool to Predict Mortality in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2025. [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Bohm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Celutkiene, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2023, 44, 3627-3639. [CrossRef]

- Gamarra, A.; Salamanca, J.; Diez-Villanueva, P.; Cuenca, S.; Vazquez, J.; Aguilar, R.J.; Diego, G.; Rodriguez, A.P.; Alfonso, F. Ultrasound imaging of congestion in heart failure: a narrative review. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2025, 15, 233-250. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [CrossRef]

- Wells, A.U.; Shea, B.; O'Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.A.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Available online: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on.

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savovic, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [CrossRef]

- Fede, G.; Privitera, G.; Tomaselli, T.; Spadaro, L.; Purrello, F. Cardiovascular dysfunction in patients with liver cirrhosis. Ann Gastroenterol 2015, 28, 31-40.

- Mukhtar, A.; Dabbous, H. Modulation of splanchnic circulation: Role in perioperative management of liver transplant patients. World J Gastroenterol 2016, 22, 1582-1592. [CrossRef]

- Valentova, M.; von Haehling, S.; Bauditz, J.; Doehner, W.; Ebner, N.; Bekfani, T.; Elsner, S.; Sliziuk, V.; Scherbakov, N.; Murin, J.; et al. Intestinal congestion and right ventricular dysfunction: a link with appetite loss, inflammation, and cachexia in chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2016, 37, 1684-1691. [CrossRef]

- Sandek, A.; Swidsinski, A.; Schroedl, W.; Watson, A.; Valentova, M.; Herrmann, R.; Scherbakov, N.; Cramer, L.; Rauchhaus, M.; Grosse-Herrenthey, A.; et al. Intestinal blood flow in patients with chronic heart failure: a link with bacterial growth, gastrointestinal symptoms, and cachexia. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014, 64, 1092-1102. [CrossRef]

- Pellicori, P.; Zhang, J.; Cuthbert, J.; Urbinati, A.; Shah, P.; Kazmi, S.; Clark, A.L.; Cleland, J.G.F. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein in chronic heart failure: patient characteristics, phenotypes, and mode of death. Cardiovasc Res 2020, 116, 91-100. [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, Y.; Ishii, S.; Fujita, T.; Iida, Y.; Kaida, T.; Nabeta, T.; Maekawa, E.; Yanagisawa, T.; Koitabashi, T.; Takeuchi, I.; et al. Prognostic impact of intestinal wall thickening in hospitalized patients with heart failure. International journal of cardiology 2017, 230, 120-126. [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, Y.; Ishii, S.; Maemura, K.; Oki, T.; Yazaki, M.; Fujita, T.; Nabeta, T.; Maekawa, E.; Koitabashi, T.; Ako, J. Association between intestinal oedema and oral loop diuretic resistance in hospitalized patients with acute heart failure. ESC Heart Fail 2021, 8, 4067-4076. [CrossRef]

- Hao, R.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, J.; Fan, R.; Chen, P.; Yin, N.; Qin, H. Evaluation value of ultrasound on gastrointestinal function in patients with acute heart failure. Front Cardiovasc Med 2024, 11, 1475920. [CrossRef]

- Ciozda, W.; Kedan, I.; Kehl, D.W.; Zimmer, R.; Khandwalla, R.; Kimchi, A. The efficacy of sonographic measurement of inferior vena cava diameter as an estimate of central venous pressure. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2016, 14, 33. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, G. Inferior Vena Cava Collapsibility Index is a Valuable and Non-Invasive Index for Elevated General Heart End-Diastolic Volume Index Estimation in Septic Shock Patients. Med Sci Monit 2016, 22, 3843-3848. [CrossRef]

- Aspromonte, N.; Fumarulo, I.; Petrucci, L.; Biferali, B.; Liguori, A.; Gasbarrini, A.; Massetti, M.; Miele, L. The Liver in Heart Failure: From Biomarkers to Clinical Risk. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Wells, M.L.; Fenstad, E.R.; Poterucha, J.T.; Hough, D.M.; Young, P.M.; Araoz, P.A.; Ehman, R.L.; Venkatesh, S.K. Imaging Findings of Congestive Hepatopathy. Radiographics 2016, 36, 1024-1037. [CrossRef]

- Wells, M.L.; Venkatesh, S.K. Congestive hepatopathy. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2018, 43, 2037-2051. [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, H.; Yokosuka, O. Ultrasonography for Noninvasive Assessment of Portal Hypertension. Gut Liver 2017, 11, 464-473. [CrossRef]

- Gerstenmaier, J.F.; Gibson, R.N. Ultrasound in chronic liver disease. Insights into imaging 2014, 5, 441-455. [CrossRef]

- Weinreb, J.; Kumari, S.; Phillips, G.; Pochaczevsky, R. Portal vein measurements by real-time sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1982, 139, 497-499. [CrossRef]

- Procopet, B.; Berzigotti, A. Diagnosis of cirrhosis and portal hypertension: imaging, non-invasive markers of fibrosis and liver biopsy. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2017, 5, 79-89. [CrossRef]

- McNaughton, D.A.; Abu-Yousef, M.M. Doppler US of the liver made simple. Radiographics 2011, 31, 161-188. [CrossRef]

- Allen, L.A.; Felker, G.M.; Pocock, S.; McMurray, J.J.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Swedberg, K.; Wang, D.; Yusuf, S.; Michelson, E.L.; Granger, C.B.; et al. Liver function abnormalities and outcome in patients with chronic heart failure: data from the Candesartan in Heart Failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity (CHARM) program. European journal of heart failure 2009, 11, 170-177. [CrossRef]

- Brankovic, M.; Lee, P.; Pyrsopoulos, N.; Klapholz, M. Cardiac Syndromes in Liver Disease: A Clinical Conundrum. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2023, 11, 975-986. [CrossRef]

- Harjola, V.P.; Mullens, W.; Banaszewski, M.; Bauersachs, J.; Brunner-La Rocca, H.P.; Chioncel, O.; Collins, S.P.; Doehner, W.; Filippatos, G.S.; Flammer, A.J.; et al. Organ dysfunction, injury and failure in acute heart failure: from pathophysiology to diagnosis and management. A review on behalf of the Acute Heart Failure Committee of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European journal of heart failure 2017, 19, 821-836. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, K.; Feng, G.; Tian, X. Association Between the Albumin-Bilirubin (ALBI) Score and All-cause Mortality Risk in Intensive Care Unit Patients with Heart Failure. Glob Heart 2024, 19, 97. [CrossRef]

- Singal, A.K.; Ahmad, M.; Soloway, R.D. Duplex Doppler ultrasound examination of the portal venous system: an emerging novel technique for the estimation of portal vein pressure. Dig Dis Sci 2010, 55, 1230-1240. [CrossRef]

- Tessler, F.N.; Gehring, B.J.; Gomes, A.S.; Perrella, R.R.; Ragavendra, N.; Busuttil, R.W.; Grant, E.G. Diagnosis of portal vein thrombosis: value of color Doppler imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1991, 157, 293-296. [CrossRef]

- Hosoki, T.; Arisawa, J.; Marukawa, T.; Tokunaga, K.; Kuroda, C.; Kozuka, T.; Nakano, S. Portal blood flow in congestive heart failure: pulsed duplex sonographic findings. Radiology 1990, 174, 733-736. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.C.; Lovett, K.E.; Chezmar, J.L.; Moyers, J.H.; Torres, W.E.; Murphy, F.B.; Bernardino, M.E. Comparison of pulsed Doppler sonography and angiography in patients with portal hypertension. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1987, 149, 77-81. [CrossRef]

- Gaiani, S.; Bolondi, L.; Li Bassi, S.; Santi, V.; Zironi, G.; Barbara, L. Effect of meal on portal hemodynamics in healthy humans and in patients with chronic liver disease. Hepatology 1989, 9, 815-819.

- Subramanyam, B.R.; Balthazar, E.J.; Madamba, M.R.; Raghavendra, B.N.; Horii, S.C.; Lefleur, R.S. Sonography of portosystemic venous collaterals in portal hypertension. Radiology 1983, 146, 161-166. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R.N.; Gibson, P.R.; Donlan, J.D.; Clunie, D.A. Identification of a patent paraumbilical vein by using Doppler sonography: importance in the diagnosis of portal hypertension. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1989, 153, 513-516. [CrossRef]

- Iranpour, P.; Lall, C.; Houshyar, R.; Helmy, M.; Yang, A.; Choi, J.I.; Ward, G.; Goodwin, S.C. Altered Doppler flow patterns in cirrhosis patients: an overview. Ultrasonography 2016, 35, 3-12. [CrossRef]

- Afif, A.M.; Chang, J.P.; Wang, Y.Y.; Lau, S.D.; Deng, F.; Goh, S.Y.; Pwint, M.K.; Ooi, C.C.; Venkatanarasimha, N.; Lo, R.H. A sonographic Doppler study of the hepatic vein, portal vein and hepatic artery in liver cirrhosis: Correlation of hepatic hemodynamics with clinical Child Pugh score in Singapore. Ultrasound 2017, 25, 213-221. [CrossRef]

- Baikpour, M.; Ozturk, A.; Dhyani, M.; Mercaldo, N.D.; Pierce, T.T.; Grajo, J.R.; Samir, A.E. Portal Venous Pulsatility Index: A Novel Biomarker for Diagnosis of High-Risk Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2020, 214, 786-791. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yin, J.; Duan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, L.; Cao, T. Assessment of intrahepatic blood flow by Doppler ultrasonography: relationship between the hepatic vein, portal vein, hepatic artery and portal pressure measured intraoperatively in patients with portal hypertension. BMC Gastroenterol 2011, 11, 84. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Yousef, M.M.; Milam, S.G.; Farner, R.M. Pulsatile portal vein flow: a sign of tricuspid regurgitation on duplex Doppler sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1990, 155, 785-788. [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, V.; Vikneswaran, G.; Rola, P.; Raju, S.; Bhat, R.S.; Jayakumar, A.; Alva, A. Combination of Inferior Vena Cava Diameter, Hepatic Venous Flow, and Portal Vein Pulsatility Index: Venous Excess Ultrasound Score (VEXUS Score) in Predicting Acute Kidney Injury in Patients with Cardiorenal Syndrome: A Prospective Cohort Study. Indian J Crit Care Med 2020, 24, 783-789. [CrossRef]

- Prowle, J.R.; Bellomo, R. Fluid administration and the kidney. Curr Opin Crit Care 2013, 19, 308-314. [CrossRef]

- Gallix, B.P.; Taourel, P.; Dauzat, M.; Bruel, J.M.; Lafortune, M. Flow pulsatility in the portal venous system: a study of Doppler sonography in healthy adults. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1997, 169, 141-144. [CrossRef]

- Argaiz, E.R. VExUS Nexus: Bedside Assessment of Venous Congestion. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2021, 28, 252-261. [CrossRef]

- Caselitz, M.; Bahr, M.J.; Bleck, J.S.; Chavan, A.; Manns, M.P.; Wagner, S.; Gebel, M. Sonographic criteria for the diagnosis of hepatic involvement in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT). Hepatology 2003, 37, 1139-1146. [CrossRef]

- Abou-Arab, O.; Beyls, C.; Moussa, M.D.; Huette, P.; Beaudelot, E.; Guilbart, M.; De Broca, B.; Yzet, T.; Dupont, H.; Bouzerar, R.; et al. Portal Vein Pulsatility Index as a Potential Risk of Venous Congestion Assessed by Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Prospective Study on Healthy Volunteers. Front Physiol 2022, 13, 811286. [CrossRef]

- Gorg, C.; Seifart, U.; Zugmaier, G. Color Doppler sonographic signs of respiration-dependent hepatofugal portal flow. J Clin Ultrasound 2004, 32, 62-68. [CrossRef]

- Hidajat, N.; Stobbe, H.; Griesshaber, V.; Felix, R.; Schroder, R.J. Imaging and radiological interventions of portal vein thrombosis. Acta Radiol 2005, 46, 336-343. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Ghittoni, G.; Ravetta, V.; Torello Viera, F.; Rosa, L.; Serassi, M.; Scabini, M.; Vercelli, A.; Tinelli, C.; Dal Bello, B.; et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography and spiral computed tomography in the detection and characterization of portal vein thrombosis complicating hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur Radiol 2008, 18, 1749-1756. [CrossRef]

- Altinkaya, N.; Koc, Z.; Ulusan, S.; Demir, S.; Gurel, K. Effects of respiratory manoeuvres on hepatic vein Doppler waveform and flow velocities in a healthy population. Eur J Radiol 2011, 79, 60-63. [CrossRef]

- Piscaglia, F.; Donati, G.; Serra, C.; Muratori, R.; Solmi, L.; Gaiani, S.; Gramantieri, L.; Bolondi, L. Value of splanchnic Doppler ultrasound in the diagnosis of portal hypertension. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2001, 27, 893-899.

- Morales, A.; Hirsch, M.; Schneider, D.; Gonzalez, D. Congestive hepatopathy: the role of the radiologist in the diagnosis. Diagn Interv Radiol 2020, 26, 541-545. [CrossRef]

- Rengo, C.; Brevetti, G.; Sorrentino, G.; D'Amato, T.; Imparato, M.; Vitale, D.F.; Acanfora, D.; Rengo, F. Portal vein pulsatility ratio provides a measure of right heart function in chronic heart failure. Ultrasound Med Biol 1998, 24, 327-332. [CrossRef]

- Goncalvesova, E.; Lesny, P.; Luknar, M.; Solik, P.; Varga, I. Changes of portal flow in heart failure patients with liver congestion. Bratislavske lekarske listy 2010, 111, 635-639.

- Catalano, D.; Caruso, G.; DiFazzio, S.; Carpinteri, G.; Scalisi, N.; Trovato, G.M. Portal vein pulsatility ratio and heart failure. J Clin Ultrasound 1998, 26, 27-31. [CrossRef]

- Deschamps, J.; Denault, A.; Galarza, L.; Rola, P.; Ledoux-Hutchinson, L.; Huard, K.; Gebhard, C.E.; Calderone, A.; Canty, D.; Beaubien-Souligny, W. Venous Doppler to Assess Congestion: A Comprehensive Review of Current Evidence and Nomenclature. Ultrasound Med Biol 2023, 49, 3-17. [CrossRef]

- Husain-Syed, F.; Birk, H.W.; Ronco, C.; Schormann, T.; Tello, K.; Richter, M.J.; Wilhelm, J.; Sommer, N.; Steyerberg, E.; Bauer, P.; et al. Doppler-Derived Renal Venous Stasis Index in the Prognosis of Right Heart Failure. J Am Heart Assoc 2019, 8, e013584. [CrossRef]

- Moriyasu, F.; Nishida, O.; Ban, N.; Nakamura, T.; Sakai, M.; Miyake, T.; Uchino, H. "Congestion index" of the portal vein. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1986, 146, 735-739. [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, Y.; Ishii, S.; Yazaki, M.; Fujita, T.; Iida, Y.; Kaida, T.; Nabeta, T.; Nakatani, E.; Maekawa, E.; Yanagisawa, T.; et al. Portal congestion and intestinal edema in hospitalized patients with heart failure. Heart and vessels 2018, 33, 740-751. [CrossRef]

- Bouabdallaoui, N.; Beaubien-Souligny, W.; Oussaid, E.; Henri, C.; Racine, N.; Denault, A.Y.; Rouleau, J.L. Assessing Splanchnic Compartment Using Portal Venous Doppler and Impact of Adding It to the EVEREST Score for Risk Assessment in Heart Failure. CJC Open 2020, 2, 311-320. [CrossRef]

- Galindo, P.; Gasca, C.; Argaiz, E.R.; Koratala, A. Point of care venous Doppler ultrasound: Exploring the missing piece of bedside hemodynamic assessment. World J Crit Care Med 2021, 10, 310-322. [CrossRef]

- Rola, P.; Miralles-Aguiar, F.; Argaiz, E.; Beaubien-Souligny, W.; Haycock, K.; Karimov, T.; Dinh, V.A.; Spiegel, R. Clinical applications of the venous excess ultrasound (VExUS) score: conceptual review and case series. Ultrasound J 2021, 13, 32. [CrossRef]

- Turk, M.; Koratala, A.; Robertson, T.; Kalagara, H.K.P.; Bronshteyn, Y.S. Demystifying Venous Excess Ultrasound (VExUS): Image Acquisition and Interpretation. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE 2025. [CrossRef]

- Istrail, L.; Kiernan, J.; Stepanova, M. A Novel Method for Estimating Right Atrial Pressure With Point-of-Care Ultrasound. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2023, 36, 278-283. [CrossRef]

- Beaubien-Souligny, W.; Benkreira, A.; Robillard, P.; Bouabdallaoui, N.; Chasse, M.; Desjardins, G.; Lamarche, Y.; White, M.; Bouchard, J.; Denault, A. Alterations in Portal Vein Flow and Intrarenal Venous Flow Are Associated With Acute Kidney Injury After Cardiac Surgery: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2018, 7, e009961. [CrossRef]

- Iida, N.; Seo, Y.; Sai, S.; Machino-Ohtsuka, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Ishizu, T.; Kawakami, Y.; Aonuma, K. Clinical Implications of Intrarenal Hemodynamic Evaluation by Doppler Ultrasonography in Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail 2016, 4, 674-682. [CrossRef]

- Beaubien-Souligny, W.; Rola, P.; Haycock, K.; Bouchard, J.; Lamarche, Y.; Spiegel, R.; Denault, A.Y. Quantifying systemic congestion with Point-Of-Care ultrasound: development of the venous excess ultrasound grading system. Ultrasound J 2020, 12, 16. [CrossRef]

- Goldhammer, E.; Mesnick, N.; Abinader, E.G.; Sagiv, M. Dilated inferior vena cava: a common echocardiographic finding in highly trained elite athletes. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1999, 12, 988-993. [CrossRef]

- Vivier, E.; Metton, O.; Piriou, V.; Lhuillier, F.; Cottet-Emard, J.M.; Branche, P.; Duperret, S.; Viale, J.P. Effects of increased intra-abdominal pressure on central circulation. Br J Anaesth 2006, 96, 701-707. [CrossRef]

- Crespo-Aznarez, S.; Campos-Saenz de Santamaria, A.; Sanchez-Marteles, M.; Garces-Horna, V.; Josa-Laorden, C.; Gimenez-Lopez, I.; Perez-Calvo, J.I.; Rubio-Gracia, J. The Association Between Intra-abdominal Pressure and Diuretic Response in Heart Failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2023, 20, 390-400. [CrossRef]

- Rora Bertovic, M.; Trkulja, V.; Curcic Karabaic, E.; Sundalic, S.; Bielen, L.; Ivicic, T.; Radonic, R. Influence of Increased Intra-Abdominal Pressure on the Validity of Ultrasound-Derived Inferior Vena Cava Measurements for Estimating Central Venous Pressure. J Clin Med 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Davison, R.; Cannon, R. Estimation of central venous pressure by examination of jugular veins. Am Heart J 1974, 87, 279-282. [CrossRef]

- Chayapinun, V.; Koratala, A.; Assavapokee, T. Seeing beneath the surface: Harnessing point-of-care ultrasound for internal jugular vein evaluation. World J Cardiol 2024, 16, 73-79. [CrossRef]

- Leal-Villarreal, M.A.J.; Aguirre-Villarreal, D.; Vidal-Mayo, J.J.; Argaiz, E.R.; Garcia-Juarez, I. Correlation of Internal Jugular Vein Collapsibility With Central Venous Pressure in Patients With Liver Cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2023, 118, 1684-1687. [CrossRef]

- Bauman, Z.; Coba, V.; Gassner, M.; Amponsah, D.; Gallien, J.; Blyden, D.; Killu, K. Inferior vena cava collapsibility loses correlation with internal jugular vein collapsibility during increased thoracic or intra-abdominal pressure. J Ultrasound 2015, 18, 343-348. [CrossRef]

- Benkreira, A.; Beaubien-Souligny, W.; Mailhot, T.; Bouabdallaoui, N.; Robillard, P.; Desjardins, G.; Lamarche, Y.; Cossette, S.; Denault, A. Portal Hypertension Is Associated With Congestive Encephalopathy and Delirium After Cardiac Surgery. Can J Cardiol 2019, 35, 1134-1141. [CrossRef]

- Croquette, M.; Puyade, M.; Montani, D.; Jutant, E.M.; De Gea, M.; Laneelle, D.; Thollot, C.; Trihan, J.E. Diagnostic Performance of Pulsed Doppler Ultrasound of the Common Femoral Vein to Detect Elevated Right Atrial Pressure in Pulmonary Hypertension. Journal of cardiovascular translational research 2023, 16, 141-151. [CrossRef]

- Croquette, M.; Larrieu Ardilouze, E.; Beaufort, C.; Jutant, E.M.; Puyade, M.; Montani, D.; Thollot, C.; Laneelle, D.; De Gea, M.; Trihan, J.E. Femoral venous stasis index predicts elevated right atrial pressure and mortality in pulmonary hypertension. ERJ Open Res 2025, 11. [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, V.; Rola, P.; Denault, A.; Vikneswaran, G.; Spiegel, R. Femoral vein pulsatility: a simple tool for venous congestion assessment. Ultrasound J 2023, 15, 24. [CrossRef]

- Murayama, M.; Kaga, S.; Okada, K.; Iwano, H.; Nakabachi, M.; Yokoyama, S.; Nishino, H.; Tsujinaga, S.; Chiba, Y.; Ishizaka, S.; et al. Clinical Utility of Superior Vena Cava Flow Velocity Waveform Measured from the Subcostal Window for Estimating Right Atrial Pressure. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2022, 35, 727-737. [CrossRef]

- Murayama, M.; Kaga, S.; Onoda, A.; Nishino, H.; Yokoyama, S.; Goto, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Yanagi, Y.; Shimono, Y.; Nakamura, K.; et al. Head-to-Head Comparison of Hepatic Vein and Superior Vena Cava Flow Velocity Waveform Analyses for Predicting Elevated Right Atrial Pressure. Ultrasound Med Biol 2024, 50, 1352-1360. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Denault, A.Y.; Beaubien-Souligny, W.; Cho, S.A.; Ji, S.H.; Jang, Y.E.; Kim, E.H.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, J.T. Evaluation of Portal, Splenic, and Hepatic Vein Flows in Children Undergoing Congenital Heart Surgery. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia 2023, 37, 1456-1468. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, C.; Chamberland, M.E.; Aldred, M.P.; Couture, E.; Beaubien-Souligny, W.; Calderone, A.; Lamarche, Y.; Denault, A. Constrictive pericarditis: portal, splenic, and femoral venous Doppler pulsatility: a case series. Canadian journal of anaesthesia = Journal canadien d'anesthesie 2022, 69, 119-128. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Noguera, A.; Montserrat, E.; Torrubia, S.; Villalba, J. Doppler in hepatic cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis. Semin.Ultrasound CT MR 2002, 23, 19-36.

- Kim, M.Y.; Baik, S.K.; Park, D.H.; Lim, D.W.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, H.S.; Kwon, S.O.; Kim, Y.J.; Chang, S.J.; Lee, S.S. Damping index of Doppler hepatic vein waveform to assess the severity of portal hypertension and response to propranolol in liver cirrhosis: a prospective nonrandomized study. Liver Int 2007, 27, 1103-1110. [CrossRef]

- Dodd, G.D., 3rd; Memel, D.S.; Zajko, A.B.; Baron, R.L.; Santaguida, L.A. Hepatic artery stenosis and thrombosis in transplant recipients: Doppler diagnosis with resistive index and systolic acceleration time. Radiology 1994, 192, 657-661. [CrossRef]

- Lemmer, A.; VanWagner, L.; Ganger, D. Congestive hepatopathy: Differentiating congestion from fibrosis. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken) 2017, 10, 139-143. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.W.; Kalk, J.F.; Klein, C.P. Hepatic arterial pulsatility index in cirrhosis: correlation with portal pressure. J Hepatol 1999, 30, 876-881. [CrossRef]

- Bolognesi, M.; Sacerdoti, D.; Merkel, C.; Gerunda, G.; Maffei-Faccioli, A.; Angeli, P.; Jemmolo, R.M.; Bombonato, G.; Gatta, A. Splenic Doppler impedance indices: influence of different portal hemodynamic conditions. Hepatology 1996, 23, 1035-1040. [CrossRef]

- Bolognesi, M.; Quaglio, C.; Bombonato, G.; Gaiani, S.; Pesce, P.; Bizzotto, P.; Favaretto, E.; Gatta, A.; Sacerdoti, D. Splenic Doppler impedance indices estimate splenic congestion in patients with right-sided or congestive heart failure. Ultrasound Med Biol 2012, 38, 21-27. [CrossRef]

- Yoshihisa, A.; Ishibashi, S.; Matsuda, M.; Yamadera, Y.; Ichijo, Y.; Sato, Y.; Yokokawa, T.; Misaka, T.; Oikawa, M.; Kobayashi, A.; et al. Clinical Implications of Hepatic Hemodynamic Evaluation by Abdominal Ultrasonographic Imaging in Patients With Heart Failure. J Am Heart Assoc 2020, 9, e016689. [CrossRef]

- Harjola, V.P.; Mebazaa, A.; Celutkiene, J.; Bettex, D.; Bueno, H.; Chioncel, O.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Falk, V.; Filippatos, G.; Gibbs, S.; et al. Contemporary management of acute right ventricular failure: a statement from the Heart Failure Association and the Working Group on Pulmonary Circulation and Right Ventricular Function of the European Society of Cardiology. European journal of heart failure 2016, 18, 226-241. [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2015, 28, 1-39 e14. [CrossRef]

- Paulus, W.J.; Tschope, C. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013, 62, 263-271. [CrossRef]

- Redfield, M.M. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med 2016, 375, 1868-1877. [CrossRef]

- Sanders-van Wijk, S.; van Empel, V.; Davarzani, N.; Maeder, M.T.; Handschin, R.; Pfisterer, M.E.; Brunner-La Rocca, H.P.; investigators, T.-C. Circulating biomarkers of distinct pathophysiological pathways in heart failure with preserved vs. reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. European journal of heart failure 2015, 17, 1006-1014. [CrossRef]

- Ponikowski, P.; Voors, A.A.; Anker, S.D.; Bueno, H.; Cleland, J.G.; Coats, A.J.; Falk, V.; Gonzalez-Juanatey, J.R.; Harjola, V.P.; Jankowska, E.A.; et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. European journal of heart failure 2016, 18, 891-975. [CrossRef]

- Simonneau, G.; Montani, D.; Celermajer, D.S.; Denton, C.P.; Gatzoulis, M.A.; Krowka, M.; Williams, P.G.; Souza, R. Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. The European respiratory journal 2019, 53. [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.A.; Couch, L.S.; Rider, O.J. Myocardial Metabolism in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. J Clin Med 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Wagg, C.S.; Wong, N.; Wei, K.; Ketema, E.B.; Zhang, L.; Fang, L.; Seubert, J.M.; Lopaschuk, G.D. Alterations of myocardial ketone metabolism in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). ESC Heart Fail 2025, 12, 3179-3182. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.N.; Liu, Y.T.; Kang, S.; Qu Yang, D.Z.; Xiao, H.Y.; Ma, W.K.; Shen, C.X.; Pan, J.W. Interdependence between myocardial deformation and perfusion in patients with T2DM and HFpEF: a feature-tracking and stress perfusion CMR study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2024, 23, 303. [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Guo, J.; Tao, H.; Gu, Z.; Tang, W.; Zhou, F.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Jia, D.; Sun, Y.; et al. Circulating mediators linking cardiometabolic diseases to HFpEF: a mediation Mendelian randomization analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2025, 24, 201. [CrossRef]

- Carluccio, E.; Biagioli, P.; Reboldi, G.; Mengoni, A.; Lauciello, R.; Zuchi, C.; D'Addario, S.; Bardelli, G.; Ambrosio, G. Left ventricular remodeling response to SGLT2 inhibitors in heart failure: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2023, 22, 235. [CrossRef]

- Correale, M.; D'Alessandro, D.; Tricarico, L.; Ceci, V.; Mazzeo, P.; Capasso, R.; Ferrara, S.; Barile, M.; Di Nunno, N.; Rossi, L.; et al. Left ventricular reverse remodeling after combined ARNI and SGLT2 therapy in heart failure patients with reduced or mildly reduced ejection fraction. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc 2024, 54, 101492. [CrossRef]

- Veltmann, C.; Duncker, D.; Doering, M.; Gummadi, S.; Robertson, M.; Wittlinger, T.; Colley, B.J.; Perings, C.; Jonsson, O.; Bauersachs, J.; et al. Therapy duration and improvement of ventricular function in de novo heart failure: the Heart Failure Optimization study. Eur Heart J 2024, 45, 2771-2781. [CrossRef]

- Ichimura, K.; Boehm, M.; Andruska, A.M.; Zhang, F.; Schimmel, K.; Bonham, S.; Kabiri, A.; Kheyfets, V.O.; Ichimura, S.; Reddy, S.; et al. 3D Imaging Reveals Complex Microvascular Remodeling in the Right Ventricle in Pulmonary Hypertension. Circ Res 2024, 135, 60-75. [CrossRef]

- Mendiola, E.A.; da Silva Goncalves Bos, D.; Leichter, D.M.; Vang, A.; Zhang, P.; Leary, O.P.; Gilbert, R.J.; Avazmohammadi, R.; Choudhary, G. Right Ventricular Architectural Remodeling and Functional Adaptation in Pulmonary Hypertension. Circ Heart Fail 2023, 16, e009768. [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Kato, S.; Yasuda, N.; Sawamura, S.; Fukui, K.; Iwasawa, T.; Ogura, T.; Utsunomiya, D. Integrating CT-Based Lung Fibrosis and MRI-Derived Right Ventricular Function for the Detection of Pulmonary Hypertension in Interstitial Lung Disease. J Clin Med 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Guo, D.; Wang, J.; Gong, J.; Hu, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lv, X.; Li, Y. Effects of right ventricular remodeling in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension on the outcomes of balloon pulmonary angioplasty: a 2D-speckle tracking echocardiography study. Respir Res 2024, 25, 164. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, R.; Hayashi, O.; Horio, T.; Fujiwara, R.; Matsuoka, Y.; Yokouchi, G.; Sakamoto, Y.; Matsumoto, N.; Fukuda, K.; Shimizu, M.; et al. The E/e' ratio on echocardiography as an independent predictor of the improvement of left ventricular contraction in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. J Clin Ultrasound 2023, 51, 1131-1138. [CrossRef]

- Upadhya, B.; Rose, G.A.; Stacey, R.B.; Palma, R.A.; Ryan, T.; Pendyal, A.; Kelsey, A.M. The role of echocardiography in the diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart Fail Rev 2025, 30, 899-922. [CrossRef]

- Pender, A.; Lewis-Owona, J.; Ekiyoyo, A.; Stoddard, M. Echocardiography and Heart Failure: An Echocardiographic Decision Aid for the Diagnosis and Management of Cardiomyopathies. Curr Cardiol Rep 2025, 27, 64. [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Bohm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Celutkiene, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021, 42, 3599-3726. [CrossRef]

- Kuwahara, N.; Honjo, T.; Sone, N.; Imanishi, J.; Nakayama, K.; Kamemura, K.; Iwahashi, M.; Ohta, S.; Kaihotsu, K. Clinical impact of portal vein pulsatility on the prognosis of hospitalized patients with acute heart failure. World J Cardiol 2023, 15, 599-608. [CrossRef]

- Grigore, A.M.; Grigore, M.; Balahura, A.M.; Uscoiu, G.; Verde, I.; Nicolae, C.; Badila, E.; Iliesiu, A.M. The Role of the Estimated Plasma Volume Variation in Assessing Decongestion in Patients with Acute Decompensated Heart Failure. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, S.; Antonopoulos, M. Portal vein pulsatility: An important sonographic tool assessment of systemic congestion for critical ill patients. World J Cardiol 2024, 16, 221-225. [CrossRef]

- Galderisi, M.; Cosyns, B.; Edvardsen, T.; Cardim, N.; Delgado, V.; Di Salvo, G.; Donal, E.; Sade, L.E.; Ernande, L.; Garbi, M.; et al. Standardization of adult transthoracic echocardiography reporting in agreement with recent chamber quantification, diastolic function, and heart valve disease recommendations: an expert consensus document of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. European heart journal cardiovascular Imaging 2017, 18, 1301-1310. [CrossRef]

- Nagueh, S.F.; Sanborn, D.Y.; Oh, J.K.; Anderson, B.; Billick, K.; Derumeaux, G.; Klein, A.; Koulogiannis, K.; Mitchell, C.; Shah, A.; et al. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography and for Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction Diagnosis: An Update From the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2025, 38, 537-569. [CrossRef]

- Smiseth, O.A.; Morris, D.A.; Cardim, N.; Cikes, M.; Delgado, V.; Donal, E.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Galderisi, M.; Gerber, B.L.; Gimelli, A.; et al. Multimodality imaging in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: an expert consensus document of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. European heart journal cardiovascular Imaging 2022, 23, e34-e61. [CrossRef]

- Pieske, B.; Tschope, C.; de Boer, R.A.; Fraser, A.G.; Anker, S.D.; Donal, E.; Edelmann, F.; Fu, M.; Guazzi, M.; Lam, C.S.P.; et al. How to diagnose heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the HFA-PEFF diagnostic algorithm: a consensus recommendation from the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2019, 40, 3297-3317. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M.; Rudski, L.G.; Addetia, K.; Afilalo, J.; D'Alto, M.; Freed, B.H.; Friend, L.B.; Gargani, L.; Grapsa, J.; Hassoun, P.M.; et al. Guidelines for the Echocardiographic Assessment of the Right Heart in Adults and Special Considerations in Pulmonary Hypertension: Recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2025, 38, 141-186. [CrossRef]

- Cordina, R.L.; Playford, D.; Lang, I.; Celermajer, D.S. State-of-the-Art Review: Echocardiography in Pulmonary Hypertension. Heart Lung Circ 2019, 28, 1351-1364. [CrossRef]

- Labrada, L.; Vaidy, A.; Vaidya, A. Right ventricular assessment in pulmonary hypertension. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2023, 29, 348-354. [CrossRef]

- Tsipis, A.; Petropoulou, E. Echocardiography in the Evaluation of the Right Heart. US Cardiol 2022, 16, e08. [CrossRef]

- D'Alto, M.; Di Maio, M.; Romeo, E.; Argiento, P.; Blasi, E.; Di Vilio, A.; Rea, G.; D'Andrea, A.; Golino, P.; Naeije, R. Echocardiographic probability of pulmonary hypertension: a validation study. The European respiratory journal 2022, 60. [CrossRef]

- Borlaug, B.A.; Sharma, K.; Shah, S.J.; Ho, J.E. Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: JACC Scientific Statement. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023, 81, 1810-1834. [CrossRef]

- Pastore, M.C.; Mandoli, G.E.; Aboumarie, H.S.; Santoro, C.; Bandera, F.; D'Andrea, A.; Benfari, G.; Esposito, R.; Evola, V.; Sorrentino, R.; et al. Basic and advanced echocardiography in advanced heart failure: an overview. Heart Fail Rev 2020, 25, 937-948. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Song, Y.; Chen, F. Evaluating the impact of Sacubitril/valsartan on diastolic function in patients with heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2024, 103, e37965. [CrossRef]

- Galzerano, D.; Savo, M.T.; Castaldi, B.; Kholaif, N.; Khaliel, F.; Pozza, A.; Aljheish, S.; Cattapan, I.; Martini, M.; Lassandro, E.; et al. Transforming Heart Failure Management: The Power of Strain Imaging, 3D Imaging, and Vortex Analysis in Echocardiography. J Clin Med 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Zoghbi, W.A.; Jone, P.N.; Chamsi-Pasha, M.A.; Chen, T.; Collins, K.A.; Desai, M.Y.; Grayburn, P.; Groves, D.W.; Hahn, R.T.; Little, S.H.; et al. Guidelines for the Evaluation of Prosthetic Valve Function With Cardiovascular Imaging: A Report From the American Society of Echocardiography Developed in Collaboration With the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance and the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2024, 37, 2-63. [CrossRef]

- Nuzzi, V.; Manca, P.; Mule, M.; Leone, S.; Fazzini, L.; Cipriani, M.G.; Faletra, F.F. Contemporary clinical role of echocardiography in patients with advanced heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 2024, 29, 1247-1260. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.; Rahko, P.S.; Blauwet, L.A.; Canaday, B.; Finstuen, J.A.; Foster, M.C.; Horton, K.; Ogunyankin, K.O.; Palma, R.A.; Velazquez, E.J. Guidelines for Performing a Comprehensive Transthoracic Echocardiographic Examination in Adults: Recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2019, 32, 1-64. [CrossRef]

- Colonna, P.; Pinto, F.J.; Sorino, M.; Bovenzi, F.; D'Agostino, C.; de Luca, I. The emerging role of echocardiography in the screening of patients at risk of heart failure. Am J Cardiol 2005, 96, 42L-51L. [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.F.; Campbell, D.J.; Prior, D.L. Noninvasive Cardiac Imaging and the Prediction of Heart Failure Progression in Preclinical Stage A/B Subjects. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2017, 10, 1504-1519. [CrossRef]

- Writing Group, M.; Doherty, J.U.; Kort, S.; Mehran, R.; Schoenhagen, P.; Soman, P.; Rating Panel, M.; Dehmer, G.J.; Doherty, J.U.; Schoenhagen, P.; et al. ACC/AATS/AHA/ASE/ASNC/HRS/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR/STS 2019 Appropriate Use Criteria for Multimodality Imaging in the Assessment of Cardiac Structure and Function in Nonvalvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2019, 32, 553-579. [CrossRef]

- Edvardsen, T.; Asch, F.M.; Davidson, B.; Delgado, V.; DeMaria, A.; Dilsizian, V.; Gaemperli, O.; Garcia, M.J.; Kamp, O.; Lee, D.C.; et al. Non-Invasive Imaging in Coronary Syndromes: Recommendations of The European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging and the American Society of Echocardiography, in Collaboration with The American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2022, 35, 329-354. [CrossRef]

- Chioncel, O.; Mebazaa, A.; Harjola, V.P.; Coats, A.J.; Piepoli, M.F.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Laroche, C.; Seferovic, P.M.; Anker, S.D.; Ferrari, R.; et al. Clinical phenotypes and outcome of patients hospitalized for acute heart failure: the ESC Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. European journal of heart failure 2017, 19, 1242-1254. [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, N.R.; Mazzola, M.; Bandini, G.; Barbieri, G.; Spinelli, S.; De Biase, N.; Masi, S.; Moggi-Pignone, A.; Ghiadoni, L.; Taddei, S.; et al. Prognostic Role of Sonographic Decongestion in Patients with Acute Heart Failure with Reduced and Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Multicentre Study. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.S.; FitzGerald, J.M.; Schulzer, M.; Mak, E.; Ayas, N.T. Does this dyspneic patient in the emergency department have congestive heart failure? JAMA 2005, 294, 1944-1956. [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, D.; Meziere, G.; Biderman, P.; Gepner, A.; Barre, O. The comet-tail artifact. An ultrasound sign of alveolar-interstitial syndrome. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 1997, 156, 1640-1646. [CrossRef]

- Volpicelli, G.; Elbarbary, M.; Blaivas, M.; Lichtenstein, D.A.; Mathis, G.; Kirkpatrick, A.W.; Melniker, L.; Gargani, L.; Noble, V.E.; Via, G.; et al. International evidence-based recommendations for point-of-care lung ultrasound. Intensive Care Med 2012, 38, 577-591. [CrossRef]

- Picano, E.; Frassi, F.; Agricola, E.; Gligorova, S.; Gargani, L.; Mottola, G. Ultrasound lung comets: a clinically useful sign of extravascular lung water. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2006, 19, 356-363. [CrossRef]

- Gargani, L. Lung ultrasound: a new tool for the cardiologist. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2011, 9, 6. [CrossRef]

- Chouihed, T.; Coiro, S.; Zannad, F.; Girerd, N. Lung ultrasound: a diagnostic and prognostic tool at every step in the pathway of care for acute heart failure. Am J Emerg Med 2016, 34, 656-657. [CrossRef]

- Mottola, C.; Girerd, N.; Coiro, S.; Lamiral, Z.; Rossignol, P.; Frimat, L.; Girerd, S. Evaluation of Subclinical Fluid Overload Using Lung Ultrasound and Estimated Plasma Volume in the Postoperative Period Following Kidney Transplantation. Transplant Proc 2018, 50, 1336-1341. [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, D.A.; Meziere, G.A. Relevance of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute respiratory failure: the BLUE protocol. Chest 2008, 134, 117-125. [CrossRef]

- Dubon-Peralta, E.E.; Lorenzo-Villalba, N.; Garcia-Klepzig, J.L.; Andres, E.; Mendez-Bailon, M. Prognostic value of B lines detected with lung ultrasound in acute heart failure. A systematic review. J Clin Ultrasound 2022, 50, 273-283. [CrossRef]

- Gargani, L.; Volpicelli, G. How I do it: lung ultrasound. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2014, 12, 25. [CrossRef]

- Yuriditsky, E.; Horowitz, J.M.; Panebianco, N.L.; Sauthoff, H.; Saric, M. Lung Ultrasound Imaging: A Primer for Echocardiographers. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2021, 34, 1231-1241. [CrossRef]

- Picano, E.; Scali, M.C.; Ciampi, Q.; Lichtenstein, D. Lung Ultrasound for the Cardiologist. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2018, 11, 1692-1705. [CrossRef]

- Jambrik, Z.; Monti, S.; Coppola, V.; Agricola, E.; Mottola, G.; Miniati, M.; Picano, E. Usefulness of ultrasound lung comets as a nonradiologic sign of extravascular lung water. Am J Cardiol 2004, 93, 1265-1270. [CrossRef]

- Gargani, L.; Pang, P.S.; Frassi, F.; Miglioranza, M.H.; Dini, F.L.; Landi, P.; Picano, E. Persistent pulmonary congestion before discharge predicts rehospitalization in heart failure: a lung ultrasound study. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2015, 13, 40. [CrossRef]

- Volpicelli, G.; Mussa, A.; Garofalo, G.; Cardinale, L.; Casoli, G.; Perotto, F.; Fava, C.; Frascisco, M. Bedside lung ultrasound in the assessment of alveolar-interstitial syndrome. Am J Emerg Med 2006, 24, 689-696. [CrossRef]

- Buessler, A.; Chouihed, T.; Duarte, K.; Bassand, A.; Huot-Marchand, M.; Gottwalles, Y.; Penine, A.; Andre, E.; Nace, L.; Jaeger, D.; et al. Accuracy of Several Lung Ultrasound Methods for the Diagnosis of Acute Heart Failure in the ED: A Multicenter Prospective Study. Chest 2020, 157, 99-110. [CrossRef]

- Liteplo, A.S.; Marill, K.A.; Villen, T.; Miller, R.M.; Murray, A.F.; Croft, P.E.; Capp, R.; Noble, V.E. Emergency thoracic ultrasound in the differentiation of the etiology of shortness of breath (ETUDES): sonographic B-lines and N-terminal pro-brain-type natriuretic peptide in diagnosing congestive heart failure. Acad Emerg Med 2009, 16, 201-210. [CrossRef]

- Platz, E.; Jhund, P.S.; Girerd, N.; Pivetta, E.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Peacock, W.F.; Masip, J.; Martin-Sanchez, F.J.; Miro, O.; Price, S.; et al. Expert consensus document: Reporting checklist for quantification of pulmonary congestion by lung ultrasound in heart failure. European journal of heart failure 2019, 21, 844-851. [CrossRef]

- Pivetta, E.; Goffi, A.; Lupia, E.; Tizzani, M.; Porrino, G.; Ferreri, E.; Volpicelli, G.; Balzaretti, P.; Banderali, A.; Iacobucci, A.; et al. Lung Ultrasound-Implemented Diagnosis of Acute Decompensated Heart Failure in the ED: A SIMEU Multicenter Study. Chest 2015, 148, 202-210. [CrossRef]

- Pivetta, E.; Goffi, A.; Nazerian, P.; Castagno, D.; Tozzetti, C.; Tizzani, P.; Tizzani, M.; Porrino, G.; Ferreri, E.; Busso, V.; et al. Lung ultrasound integrated with clinical assessment for the diagnosis of acute decompensated heart failure in the emergency department: a randomized controlled trial. European journal of heart failure 2019, 21, 754-766. [CrossRef]

- Frassi, F.; Gargani, L.; Gligorova, S.; Ciampi, Q.; Mottola, G.; Picano, E. Clinical and echocardiographic determinants of ultrasound lung comets. Eur J Echocardiogr 2007, 8, 474-479. [CrossRef]

- Volpicelli, G.; Caramello, V.; Cardinale, L.; Mussa, A.; Bar, F.; Frascisco, M.F. Bedside ultrasound of the lung for the monitoring of acute decompensated heart failure. Am J Emerg Med 2008, 26, 585-591. [CrossRef]

- Cortellaro, F.; Ceriani, E.; Spinelli, M.; Campanella, C.; Bossi, I.; Coen, D.; Casazza, G.; Cogliati, C. Lung ultrasound for monitoring cardiogenic pulmonary edema. Intern Emerg Med 2017, 12, 1011-1017. [CrossRef]

- Ohman, J.; Harjola, V.P.; Karjalainen, P.; Lassus, J. Assessment of early treatment response by rapid cardiothoracic ultrasound in acute heart failure: Cardiac filling pressures, pulmonary congestion and mortality. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2018, 7, 311-320. [CrossRef]

- Facchini, C.; Malfatto, G.; Giglio, A.; Facchini, M.; Parati, G.; Branzi, G. Lung ultrasound and transthoracic impedance for noninvasive evaluation of pulmonary congestion in heart failure. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2016, 17, 510-517. [CrossRef]

- Coiro, S.; Porot, G.; Rossignol, P.; Ambrosio, G.; Carluccio, E.; Tritto, I.; Huttin, O.; Lemoine, S.; Sadoul, N.; Donal, E.; et al. Prognostic value of pulmonary congestion assessed by lung ultrasound imaging during heart failure hospitalisation: A two-centre cohort study. Scientific reports 2016, 6, 39426. [CrossRef]

- Platz, E.; Campbell, R.T.; Claggett, B.; Lewis, E.F.; Groarke, J.D.; Docherty, K.F.; Lee, M.M.Y.; Merz, A.A.; Silverman, M.; Swamy, V.; et al. Lung Ultrasound in Acute Heart Failure: Prevalence of Pulmonary Congestion and Short- and Long-Term Outcomes. JACC Heart Fail 2019, 7, 849-858. [CrossRef]

- Coiro, S.; Rossignol, P.; Ambrosio, G.; Carluccio, E.; Alunni, G.; Murrone, A.; Tritto, I.; Zannad, F.; Girerd, N. Prognostic value of residual pulmonary congestion at discharge assessed by lung ultrasound imaging in heart failure. European journal of heart failure 2015, 17, 1172-1181. [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Lasarte, M.; Maestro, A.; Fernandez-Martinez, J.; Lopez-Lopez, L.; Sole-Gonzalez, E.; Vives-Borras, M.; Montero, S.; Mesado, N.; Pirla, M.J.; Mirabet, S.; et al. Prevalence and prognostic impact of subclinical pulmonary congestion at discharge in patients with acute heart failure. ESC Heart Fail 2020, 7, 2621-2628. [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, T.; Bozec, E.; Pellicori, P.; Bayes-Genis, A.; Coiro, S.; Domingo, M.; Gargani, L.; Palazzuoli, A.; Girerd, N. Prognostic Value and Therapeutic Utility of Lung Ultrasound in Acute and Chronic Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2022, 15, 950-952. [CrossRef]

- Miglioranza, M.H.; Gargani, L.; Sant'Anna, R.T.; Rover, M.M.; Martins, V.M.; Mantovani, A.; Weber, C.; Moraes, M.A.; Feldman, C.J.; Kalil, R.A.; et al. Lung ultrasound for the evaluation of pulmonary congestion in outpatients: a comparison with clinical assessment, natriuretic peptides, and echocardiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2013, 6, 1141-1151. [CrossRef]

- Pellicori, P.; Shah, P.; Cuthbert, J.; Urbinati, A.; Zhang, J.; Kallvikbacka-Bennett, A.; Clark, A.L.; Cleland, J.G.F. Prevalence, pattern and clinical relevance of ultrasound indices of congestion in outpatients with heart failure. European journal of heart failure 2019, 21, 904-916. [CrossRef]

- Platz, E.; Lewis, E.F.; Uno, H.; Peck, J.; Pivetta, E.; Merz, A.A.; Hempel, D.; Wilson, C.; Frasure, S.E.; Jhund, P.S.; et al. Detection and prognostic value of pulmonary congestion by lung ultrasound in ambulatory heart failure patients. Eur Heart J 2016, 37, 1244-1251. [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, K.H.; Merz, A.A.; Lewis, E.F.; Claggett, B.L.; Crousillat, D.R.; Lau, E.S.; Silverman, M.B.; Peck, J.; Rivero, J.; Cheng, S.; et al. Pulmonary Congestion by Lung Ultrasound in Ambulatory Patients With Heart Failure With Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction and Hypertension. J Card Fail 2018, 24, 219-226. [CrossRef]

- Domingo, M.; Conangla, L.; Lupon, J.; de Antonio, M.; Moliner, P.; Santiago-Vacas, E.; Codina, P.; Zamora, E.; Cediel, G.; Gonzalez, B.; et al. Prognostic value of lung ultrasound in chronic stable ambulatory heart failure patients. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2021, 74, 862-869. [CrossRef]

- Morvai-Illes, B.; Polestyuk-Nemeth, N.; Szabo, I.A.; Monoki, M.; Gargani, L.; Picano, E.; Varga, A.; Agoston, G. The Prognostic Value of Lung Ultrasound in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction in the Ambulatory Setting. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021, 8, 758147. [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Lasarte, M.; Alvarez-Garcia, J.; Fernandez-Martinez, J.; Maestro, A.; Lopez-Lopez, L.; Sole-Gonzalez, E.; Pirla, M.J.; Mesado, N.; Mirabet, S.; Fluvia, P.; et al. Lung ultrasound-guided treatment in ambulatory patients with heart failure: a randomized controlled clinical trial (LUS-HF study). European journal of heart failure 2019, 21, 1605-1613. [CrossRef]

- Araiza-Garaygordobil, D.; Gopar-Nieto, R.; Martinez-Amezcua, P.; Cabello-Lopez, A.; Alanis-Estrada, G.; Luna-Herbert, A.; Gonzalez-Pacheco, H.; Paredes-Paucar, C.P.; Sierra-Lara, M.D.; Briseno-De la Cruz, J.L.; et al. A randomized controlled trial of lung ultrasound-guided therapy in heart failure (CLUSTER-HF study). Am Heart J 2020, 227, 31-39. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, Y.N.V.; Obokata, M.; Wiley, B.; Koepp, K.E.; Jorgenson, C.C.; Egbe, A.; Melenovsky, V.; Carter, R.E.; Borlaug, B.A. The haemodynamic basis of lung congestion during exercise in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J 2019, 40, 3721-3730. [CrossRef]

- Simonovic, D.; Coiro, S.; Carluccio, E.; Girerd, N.; Deljanin-Ilic, M.; Cattadori, G.; Ambrosio, G. Exercise elicits dynamic changes in extravascular lung water and haemodynamic congestion in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction. European journal of heart failure 2018, 20, 1366-1369. [CrossRef]

- Scali, M.C.; Cortigiani, L.; Simionuc, A.; Gregori, D.; Marzilli, M.; Picano, E. Exercise-induced B-lines identify worse functional and prognostic stage in heart failure patients with depressed left ventricular ejection fraction. European journal of heart failure 2017, 19, 1468-1478. [CrossRef]

- Coiro, S.; Simonovic, D.; Deljanin-Ilic, M.; Duarte, K.; Carluccio, E.; Cattadori, G.; Girerd, N.; Ambrosio, G. Prognostic Value of Dynamic Changes in Pulmonary Congestion During Exercise Stress Echocardiography in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circ Heart Fail 2020, 13, e006769. [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, N.R.; Masi, S. The emerging role of endothelial function in cardiovascular oncology. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020, 27, 604-607. [CrossRef]

- Assavapokee, T.; Rola, P.; Assavapokee, N.; Koratala, A. Decoding VExUS: a practical guide for excelling in point-of-care ultrasound assessment of venous congestion. Ultrasound J 2024, 16, 48. [CrossRef]

- Fudim, M.; Kaye, D.M.; Borlaug, B.A.; Shah, S.J.; Rich, S.; Kapur, N.K.; Costanzo, M.R.; Brener, M.I.; Sunagawa, K.; Burkhoff, D. Venous Tone and Stressed Blood Volume in Heart Failure: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022, 79, 1858-1869. [CrossRef]

- Fudim, M.; Hernandez, A.F.; Felker, G.M. Role of Volume Redistribution in the Congestion of Heart Failure. J Am Heart Assoc 2017, 6. [CrossRef]

- Kanitkar, S.; Soni, K.; Vaishnav, B. Venous Excess Ultrasound for Fluid Assessment in Complex Cardiac Patients With Acute Kidney Injury. Cureus 2024, 16, e66003. [CrossRef]

- Melo, R.H.; Gioli-Pereira, L.; Melo, E.; Rola, P. Venous excess ultrasound score association with acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Ultrasound J 2025, 17, 16. [CrossRef]

- Jain, C.C.; Reddy, Y.N.V. Approach to Echocardiography in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Cardiol Clin 2022, 40, 431-442. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).