1. Introduction

The product market lifecycle can be categorized into two primary stages: introduction and maturity. During the introductory stage, there is limited consumer awareness of a new product, leading to low initial market demand. However, as the product matures over time, market demand will increase due to advertising, marketing efforts, and positive word-of-mouth. Companies often consider raising prices to boost profits and exploit this growing demand in the mature stage. However, as consumer fairness becomes increasingly recognized, the price increase during this stage may be perceived as unjust, surpassing the acceptable pricing threshold for consumers. This can lead to negative perceptions of transaction fairness and ultimately decrease market demand in the mature stage.

Numerous studies in behavioral economics have confirmed the significant influence of consumers’ perceptions of fair pricing on their purchasing decisions. Consumers tend to establish subjective benchmarks to determine what they consider a fair price for a product. When corporate pricing strategies exceed these benchmarks, it can lead to a sense of inequity among consumers and trigger negative psychological responses that significantly impact their purchasing behavior (

Malc et al. 2016). For instance, in 2014, the famous American streaming platform Netflix announced an abrupt price hike, causing many consumers to view the move as taking advantage of its market dominance and reputation at the expense of loyal users. This perception decreased consumer willingness to maintain subscriptions and prompted them to consider alternative streaming services.

In the face of increasing market demand during the maturity stage, previous studies have noted that companies often choose to raise prices despite the potential for dissatisfaction among price-sensitive consumers and subsequent decreases in demand. This strategic approach aims to enhance per-unit profitability, thereby strengthening overall profitability (

Diao et al. 2023). Implementing this strategy requires a deep understanding of market dynamics and consumer behavior, driven by a consistent pursuit of maximizing financial returns.

However, the presence of consumers concerned about fairness does not always lead to reduced demand. When enterprises implement price decrease strategies, it can have a positive psychological impact on fairness-conscious consumers. For instance, renowned retailers like Uniqlo have effectively utilized price decrease strategies to drive market expansion. Regular sales promotions and discounts on popular products have successfully boosted consumer demand (

Khan et al. 2023). Similarly, during major shopping events like "Double 11" in China, many companies employ aggressive price reduction tactics to stimulate substantial consumer demand, resulting in year-on-year sales growth (

Li and Puyang 2017). The principal driver of increased demand following a price decrease strategy is the consumers’ fairness concerns. They utilize the initially set higher prices as a reference for what they consider a fair price. This establishes a benchmark that, when lowered in the subsequent stage, resonates with their fairness expectations, thereby effectively stimulating demand.

Hence, it is crucial for companies to fully understand and take into consideration the impact of consumer fairness concerns on demand when developing effective two-stage pricing strategies. Examining how factors such as consumer fairness concerns and market growth scale affect the underlying mechanisms of these strategies in supply chain operations is of significant importance. This research addresses profit-driven price increases by monopolistic e-commerce entities and protects consumer rights. In doing so, companies can maintain competitiveness in mature markets, optimize profitability in supply chain management, and minimize adverse effects from pricing inequalities.

This paper differs from existing research in the following two main aspects: (1) Previous studies have primarily focused on the impact of price increase strategies on profits during the maturity stage. However, our research emphasizes that a decrease strategy, influenced by consumer fairness concerns, can stimulate consumer demand and prove advantageous under specific conditions; (2) Consumer fairness concerns establish a correlation between pricing strategies across the two stages, thereby constraining the pricing reaction functions of manufacturers and retailers. This correlation results in notable variations in profitability compared to scenarios that do not account for consumer fairness concerns.

2. Literature Review

The existing body of research relevant to this paper primarily focuses on exploring two main themes: consumer fairness concerns and the implementation of two-stage pricing strategies. These areas have garnered considerable attention due to their profound implications for market dynamics and consumer behavior in various economic contexts.

2.1. Consumer Fairness Concerns

Considerations beyond rational economic self-interest intricately influence consumers’ purchasing decisions. Fairness considerations are pivotal in shaping their perceptions of value, influencing their willingness to pay, and ultimately guiding their purchasing behavior. These non-economic factors are crucial in determining consumer behavior and should be taken into account when analyzing market trends and developing marketing strategies.

Research by

Bolton et al. (

2003) highlighted that consumer fairness concerns involve subjective evaluation of transaction terms, including price, product quality, and service levels. These evaluations are pivotal as they reflect consumers’ perceptions of whether the transactional process, especially pricing, meets their expectations of fairness and equity.

Jiang et al. (

2023) emphasized that when consumers perceive prices as aligned with the product’s perceived value, they are more inclined to make purchases. Conversely, as highlighted by

Hou et al. (

2024), perceived price inequity can significantly deter purchasing behavior, even in the face of solid product appeal. Moreover, the implications of fairness extend beyond individual transactions.

Yi et al. (

2018) argued that brands perceived as fair benefit from enhanced consumer loyalty and positive word-of-mouth, contributing to sustained market presence and competitive advantage. However, instances of perceived unfairness can trigger assertive consumer responses such as complaints, boycotts, or negative word-of-mouth campaigns, as noted by

Allender et al. (

2021), posing significant risks to a company’s reputation and market position. Further complicating matters,

Diao et al. (

2023) suggested that consumers with heightened fairness concerns exhibit greater price sensitivity and hold higher expectations regarding price fairness. This sensitivity underscores the importance of considering fairness in pricing strategies across various industries.

Extensive research has demonstrated the critical importance of considering consumer fairness concerns in developing effective supply chain pricing strategies. This factor directly influences how consumers perceive price changes and subsequently impacts their purchasing decisions, ultimately profoundly affecting corporate profit maximization.

Yang et al. (

2022) explored how retailers can strategically leverage fairness perceptions to enhance profitability under specific conditions. Meanwhile,

Gönsch et al. (

2013) highlighted the profound influence of fairness concerns on supply chain dynamics, affecting profitability and strategic decisions at every stage. Strategically,

Zhang et al. (

2019) found that addressing consumer fairness concerns can mitigate price competition and help sustain profit margins within supply chains. Moreover,

Yoshihara and Matsubayashi (

2021) observed that integrating fairness considerations into dynamic pricing decisions can optimize supply chain efficiency, particularly in complex market environments. Ultimately,

Liu et al. (

2022) argued that collaborative approaches between manufacturers and retailers, grounded in fairness principles, can yield mutually beneficial outcomes. This approach involves setting competitive yet fair prices that resonate with consumer expectations and perceptions, fostering long-term consumer trust and sustained profitability. In sum, integrating fairness considerations into pricing strategies is not just a matter of consumer preference but a strategic imperative for companies aiming to navigate competitive markets effectively while safeguarding their brand reputation and fostering consumer loyalty.

2.2. Two-Stage Pricing

Consumer psychology and behavior play a crucial role in shaping the effectiveness of two-stage pricing strategies within supply chains, particularly concerning how consumers accept and respond to pricing strategies across different sales stages. The impact of these strategies on consumers’ psychological perceptions and behavioral choices significantly influences the dynamics of supply chain management.

Research by

Prakash and Spann (

2022) highlighted that while dynamic pricing strategies offer flexibility in responding to market changes, frequent price fluctuations can influence consumers’ perceptions of fairness. Retailers can leverage this understanding to mitigate the negative impact of consumer fairness concerns on demand. Similarly,

Aviv et al. (

2019) argued that adopting a two-stage dynamic pricing strategy can optimize supply chain efficiency and profitability by adjusting prices per market dynamics, thereby effectively addressing consumer fairness concerns. Moreover,

Liu et al. (

2022) underscored the critical role of consumer fairness concerns in shaping purchasing decisions under two-stage pricing scenarios, emphasizing the need for strategies that enhance perceived fairness and predictability.

Market demand dynamics significantly impact strategic pricing decisions throughout different stages of a product’s life cycle. Enterprises must effectively navigate these fluctuations to ensure that their pricing strategies remain efficient and competitive in the marketplace.

According to

Li et al. (

2019), adopting tailored pricing strategies throughout a product’s life cycle allows enterprises to effectively accommodate shifts in market demand.

Gönsch et al. (

2013) advocated for flexible pricing adjustments that align with consumer responses to the dynamic nature of market demand. As products mature,

Chen et al. (

2020) suggested that enterprises face challenges adjusting pricing strategies to meet evolving market needs, necessitating strategic adaptations to sustain consumer interest and market share. In the maturity stage, strategic choices such as those discussed by

Che et al. (

2021), balancing brand prestige with promotional pricing strategies, become crucial for market positioning and profitability. Additionally,

Taleizadeh et al. (

2020) proposed leveraging higher introductory prices to establish a high-end product image, followed by price reductions during maturity to broaden consumer appeal and maintain competitiveness.

Understanding the consumer-centric dynamics is crucial for supply chain enterprises that aim to optimize pricing strategies throughout the product life cycle. By aligning pricing decisions with consumers’ perceptions of fairness and market demand dynamics, businesses can effectively improve profitability, maintain a competitive advantage, and encourage consumer loyalty.

The existing literature extensively discusses consumer fairness concerns and their application in market strategies, highlighting the influence of consumers’ sensitivity to price changes on their purchasing decisions. However, there is a significant research gap concerning how consumers form psychological expectations of pricing based on selling prices and how these expectations shape their responses to price adjustments. Moreover, while existing studies analyze the impact of consumer behavior on supply chain pricing and profits, they often overlook the integration of consumer fairness concerns into two-stage pricing strategies and their impact on strategy effectiveness.

This study aims to bridge these gaps by conducting a comprehensive analysis of consumer fairness concerns and their impact on the pricing strategies adopted by manufacturers and retailers within the supply chain. The research will explore various factors in the dynamic market environment, including market growth scale, consumer fairness concern coefficients, and decision-making strategies within supply chains, all of which collectively influence pricing decisions and affect the profitability of manufacturers and retailers. Specifically, this study will examine the implications of implementing price increase or decrease strategies under different market conditions, providing new insights and strategic recommendations for optimizing supply chain management practices. The goal is to contribute to a deeper understanding of consumer-centric pricing strategies and their role in sustaining supply chain operations and fostering growth to address existing research gaps.

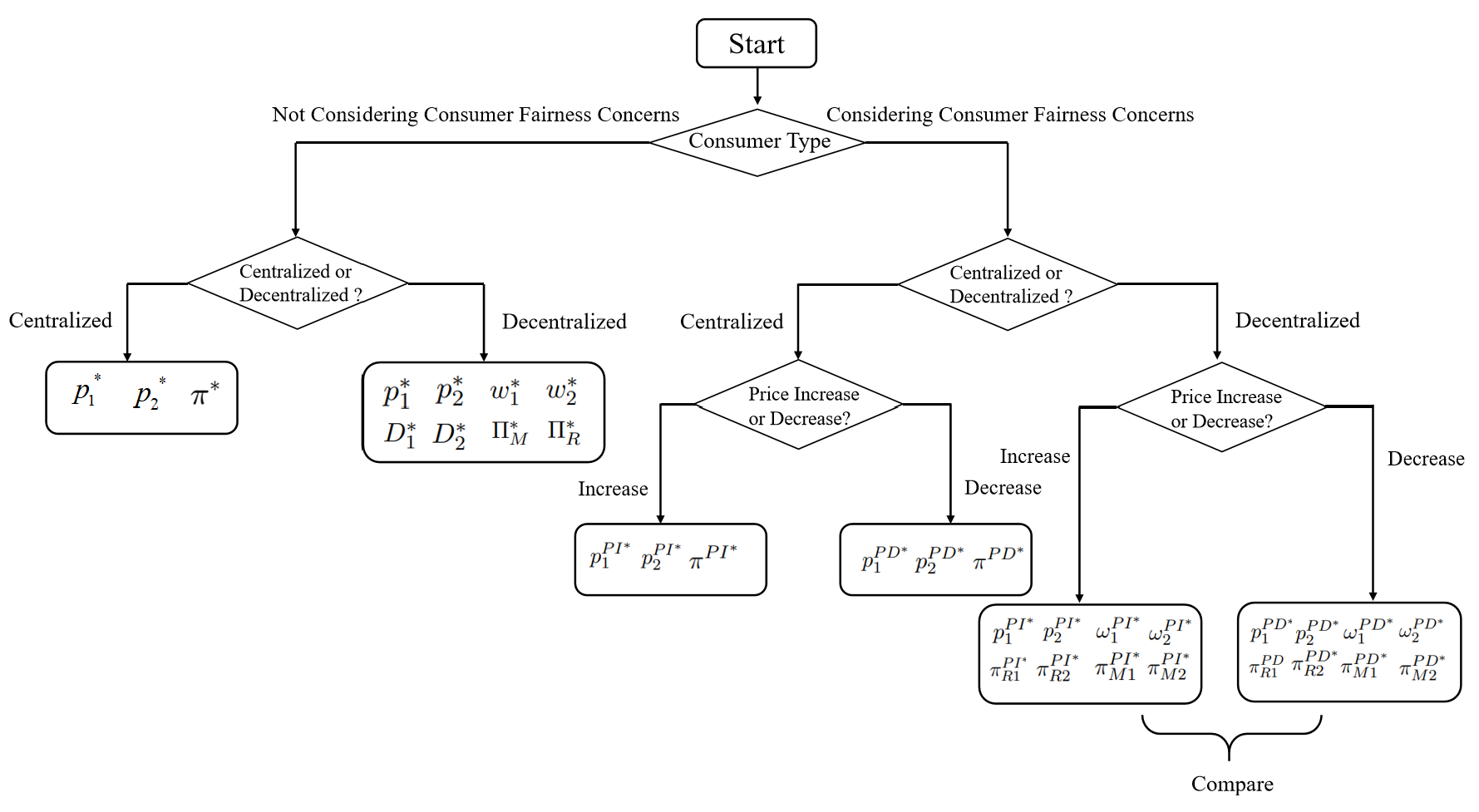

6. Numerical Analysis

This section first examines the impact of parameters such as the price elasticity of demand , the coefficient for consumer fairness concern , and the scale of market growth on the optimal two-stage retail prices and profits when the retailer adopts price increase or decrease strategies under centralized decision-making.

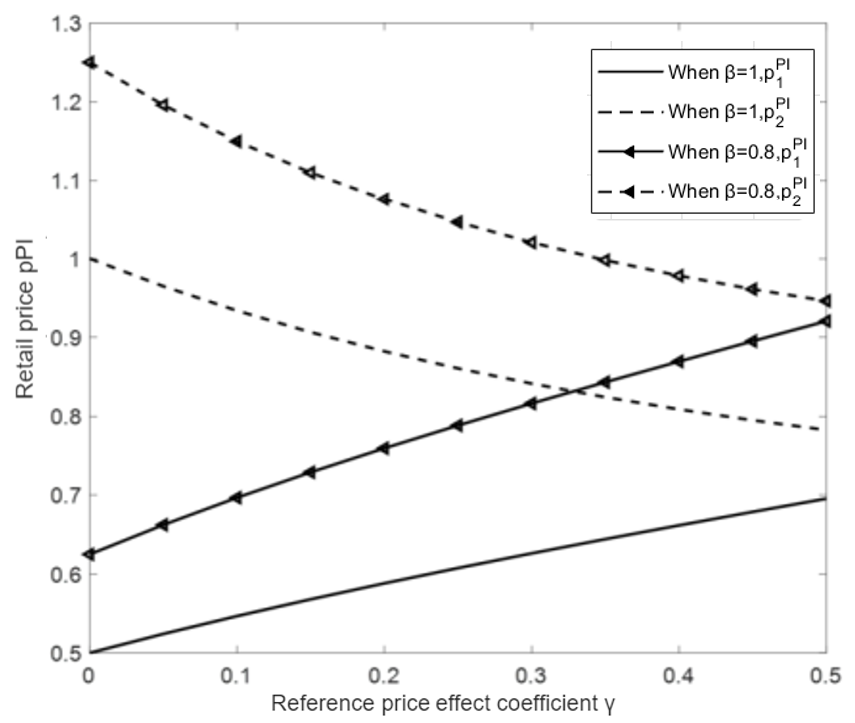

Drawing upon on Proposition 2, we investigate the relationship between the optimal two-stage prices

,

and the consumer fairness concern coefficient

, as illustrated in

Figure 2. It presents the variation when

(solid and dashed lines in the figure) and

(solid and dashed lines with triangle markers) with

.

From

Figure 2, it is evident that the optimal retail price in the first stage increases regardless of the value of

, as

increases. Conversely, the optimal retail price in the second stage decreases with an increase in

. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that as

rises, there is a reduction in the optimal retail price in the second stage, necessitating an increase in the optimal price for the first stage to offset any potential losses. Furthermore, an increase in

leads to higher optimal retail prices in both the first and second stages.

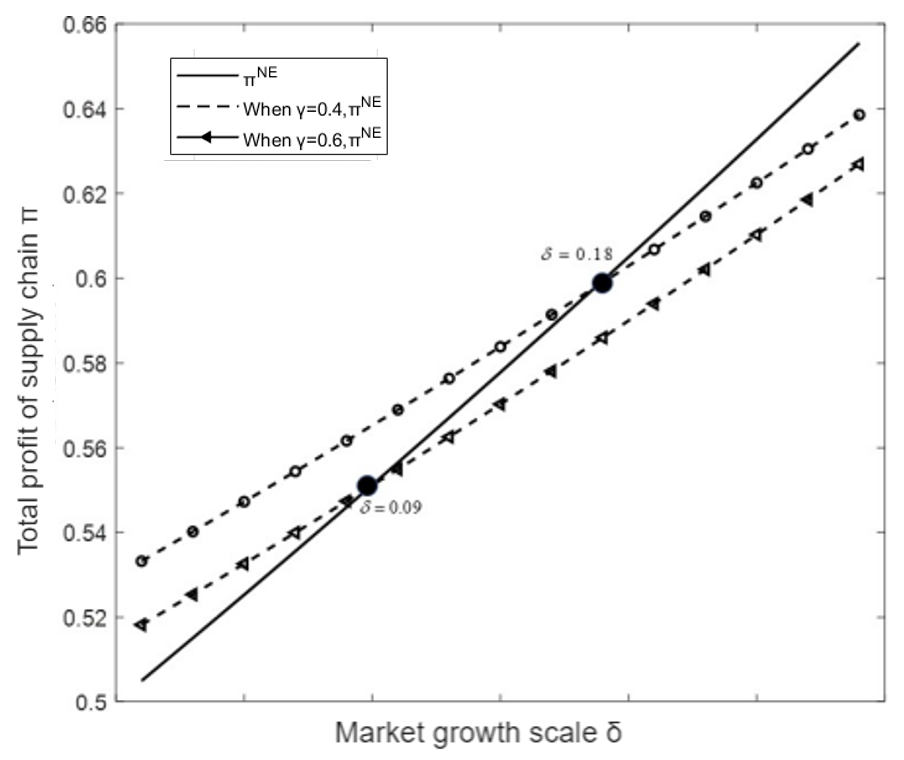

Based on Theorem 2,

Figure 3 compares optimal profits when the supply chain adopts price increase or decrease strategies under centralized decision-making. The parameter values are

and

, demonstrating the results for

(illustrated by the dashed line with triangle markers) and

(illustrated by the dashed line with hollow circle markers).

Figure 3 illustrates that when

, profit under the price decrease strategy surpasses that under the price increase strategy if

; conversely, if

, profit under the price increase strategy exceeds that under the price decrease strategy. When

, the intersection point occurs at a higher value of

at 0.18; if

, profit under the price decrease strategy is more significant than that under the price increase strategy, while if

, the opposite is true. These findings highlight that in centralized decision-making for optimal sequencing in supply chain management, it is preferable to initially implement a price decrease strategy followed by transitioning to a price increase strategy.

Table 2 presents a comprehensive overview of how variations in the consumer fairness concern coefficient

influence the optimal two-stage prices and profits of the supply chain, considering both price increase and decrease strategies. Notably, regardless of the adopted strategy, the optimal pricing in the first stage increases as

rises, indicating consumers’ sensitivity to fairness in initial pricing decisions. Conversely, the optimal pricing in the second stage decreases with increasing

, suggesting a strategic adjustment to balance consumer perceptions and profitability across stages.

Furthermore, as increases, a noticeable trend emerges: profits from the price increase strategy tend to decline, while profits from the price decrease strategy tend to improve. This trend underscores the strategic necessity of integrating consumer fairness concerns into pricing decisions to enhance supply chain profitability. By aligning pricing strategies with consumer expectations of fairness, supply chain stakeholders can optimize their market positioning and effectively navigate dynamic market conditions.

The preceding discussion focused on centralized decision-making scenarios. This section conducts a numerical investigation into the impact of parameters such as the price elasticity of demand , consumer fairness concern coefficient , and market growth scale on the optimal two-stage retail prices and profits when retailers adopt price increase or decrease strategies under decentralized decision-making. Unless otherwise specified, the default parameter values in this paper are , , and .

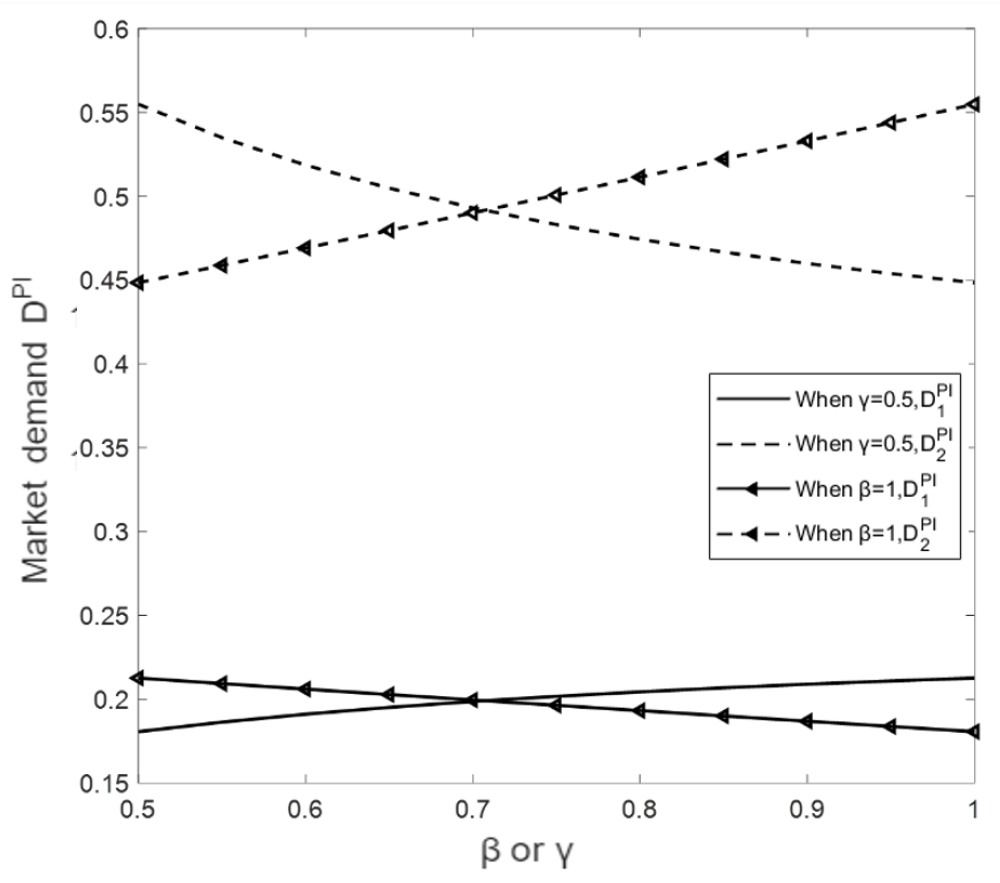

Drawing on Propositions 5, we investigate the correlation between the manufacturers’ and retailers’ second-stage optimal profits under price increase and decrease strategies to the first-stage retail price, as illustrated in

Figure 4. To begin, when setting the consumer fairness concern coefficient at

, we analyze variations in

and

as

increases from 0.5 to 1, represented by solid and dashed lines in the figure. Furthermore, with a fixed price elasticity of demand at

, we examine changes in

and

as

increases from 0.5 to 1, shown by solid lines with triangle markers and dashed lines in the figure.

From

Figure 4, it is evident that as the parameter

increases, the demand in the first stage

rises monotonically, while the demand in the second stage

decreases monotonically. On the other hand, as the parameter

increases, there is a counterintuitive trend where the demand in the second stage

increases with an increasing consumer fairness concern coefficient, while at the same time, the demand in the first stage

decreases. This can be attributed to a need to raise demand in the second stage to enhance overall profits due to a decrease in first-stage demand caused by an increase in

. Simultaneously, this decrease caused by an increase in

is outweighed by a greater increase due to a price reduction.

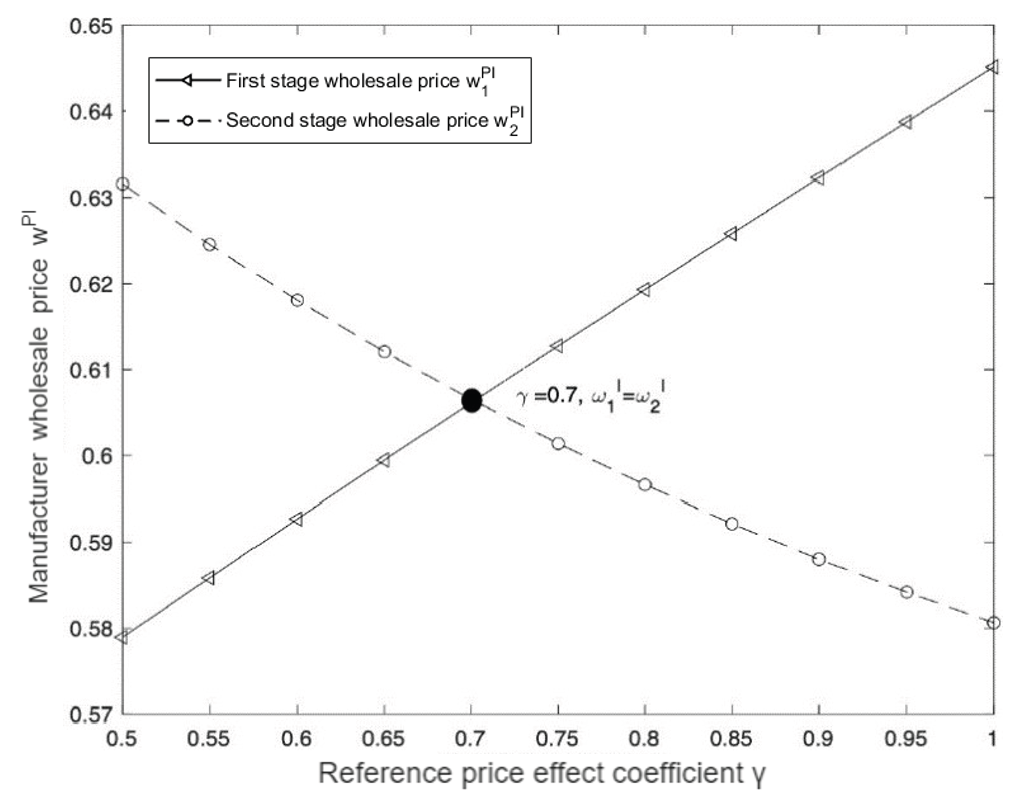

Next, we will investigate the correlation between the manufacturer’s wholesale prices in both stages and the change in

, as illustrated in

Figure 5. From the figure, it is evident that as

increases,

exhibits a monotonically increasing trend with respect to

, while

shows a monotonically decreasing pattern. When

, the manufacturer’s wholesale prices in the first and second stages are equal, i.e.,

. On the other hand, when

is relatively large, manufacturers tend to raise the wholesale price in the first stage and lower it in the second stage, thereby boosting demand in the second stage and ultimately securing higher profits.

Table 3 and

Table 4 provide a detailed exploration of how consumer fairness concerns, quantified by the coefficient

, impact the optimal pricing strategies of manufacturers and retailers when employing price increase and decrease strategies, respectively.

In

Table 3, which examines the price increase strategy, the optimal retail prices in the first stage generally rise as

increases. This trend suggests that as consumers become more sensitive to fairness considerations, retailers may perceive the need to set higher initial prices to maintain perceived fairness and safeguard profit margins. However, the optimal prices in the second stage show an initial increase followed by a decrease with increasing

. This pattern indicates a strategic response to mitigate potential consumer backlash against perceived price hikes over time, optimizing overall profitability.

In contrast,

Table 4 focuses on the strategy of price decrease. As the parameter

increases, manufacturers’ optimal pricing decisions initially rise and then decline. This trend suggests that manufacturers may initially lower prices to meet consumer fairness expectations to stimulate demand and maintain competitive positioning. However, as

continues to increase, manufacturers may adjust prices upward to balance profitability with consumers’ perceived value and fairness expectations.

7. Conclusion

This paper explores the impact of consumer fairness concerns on the two-stage dynamic pricing strategies of a manufacturer and a retailer within a supply chain. When retailers operate in a growing market with consumer fairness considerations, it is crucial to investigate the effects of implementing price increase or decrease strategies in the second stage on the profits of the manufacturer, retailer, and the overall supply chain. This is essential for the long-term operation and development of the supply chain.

This paper initially formulates and solves the Stackelberg game model under decentralized decision-making, with and without considering consumer fairness concerns. When formulating the demand function with consideration for consumer fairness concerns, it also explores the negative impact of such concerns under a price-increase strategy and the positive impact under a price-decrease strategy. Subsequently, a numerical analysis of the model results is performed. A similar research approach is also employed for the modeling, solving, and numerical analysis conducted under a centralized decision-making framework. The main conclusions and insights obtained in this paper are as follows:

- (1)

In decentralized decision-making and considering consumer fairness concerns, the retailer’s profit from implementing a price increase strategy always outweighs that of implementing a price decrease strategy. It is evident that under decentralized decision-making, even with consumer fairness concerns in the market, the supply chain will continue to prioritize the implementation of a price increase strategy;

- (2)

In decentralized decision-making, the retailer’s profit considering consumer fairness concerns may be higher than the profit without considering consumer fairness concerns under certain conditions. This is a counterintuitive phenomenon, mainly due to consumer fairness concerns, which leads to correlated reaction functions of the manufacturer and retailer in both stages. Consequently, this correlation constrains the pricing reaction functions of manufacturers and retailers, presenting a notable difference from completely independent decentralized decisions that do not take into account consumer fairness concerns;

- (3)

In centralized decision-making, the profit of the supply chain, considering consumer fairness concerns, is consistently lower than the profit achieved without such considerations. Specifically, the optimal price in the initial stage is higher when considering consumer fairness concerns but lower in the subsequent stage when not considering these concerns. It is evident that within a centralized decision-making framework, consumer fairness considerations serve to limit retailer’s ability to raise prices and compel concessions from the supply chain toward consumers, ultimately leading to a reduction in overall profit;

- (4)

In centralized decision-making and consideration of consumer fairness concerns, retailers will adopt a price decrease strategy when the market growth scale in the second stage is relatively low. Conversely, retailers opt for a price increase strategy when the market growth scale is relatively high. This also indicates that under centralized decision-making, even if retailers face a growing market, they will not always choose to implement a price increase strategy.

Further avenues for future research in this paper could be further explored. Firstly, the paper predominantly delves into examining the impact of consumer fairness concerns on the two-stage dynamic pricing within the supply chain. However, additional investigations can be carried out focusing on the pricing strategy within the supply chain under manufacturers’ and retailers’ fairness concerns; secondly, after comprehending the impact of consumer fairness concerns on supply chain pricing, it is possible to formulate reasonable contract agreements that strike a balance between the profits of manufacturers and retailers. Finally, this paper examines a Stackelberg game model in which the manufacturer holds dominance and is followed by the retailer. If the retailer has a large scale, it may influence supply chain decision-making. Additionally, the Nash game, in which manufacturers and retailers make decisions simultaneously, can also be taken into consideration.