Submitted:

09 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Sources

2.2. Study Hypotheses

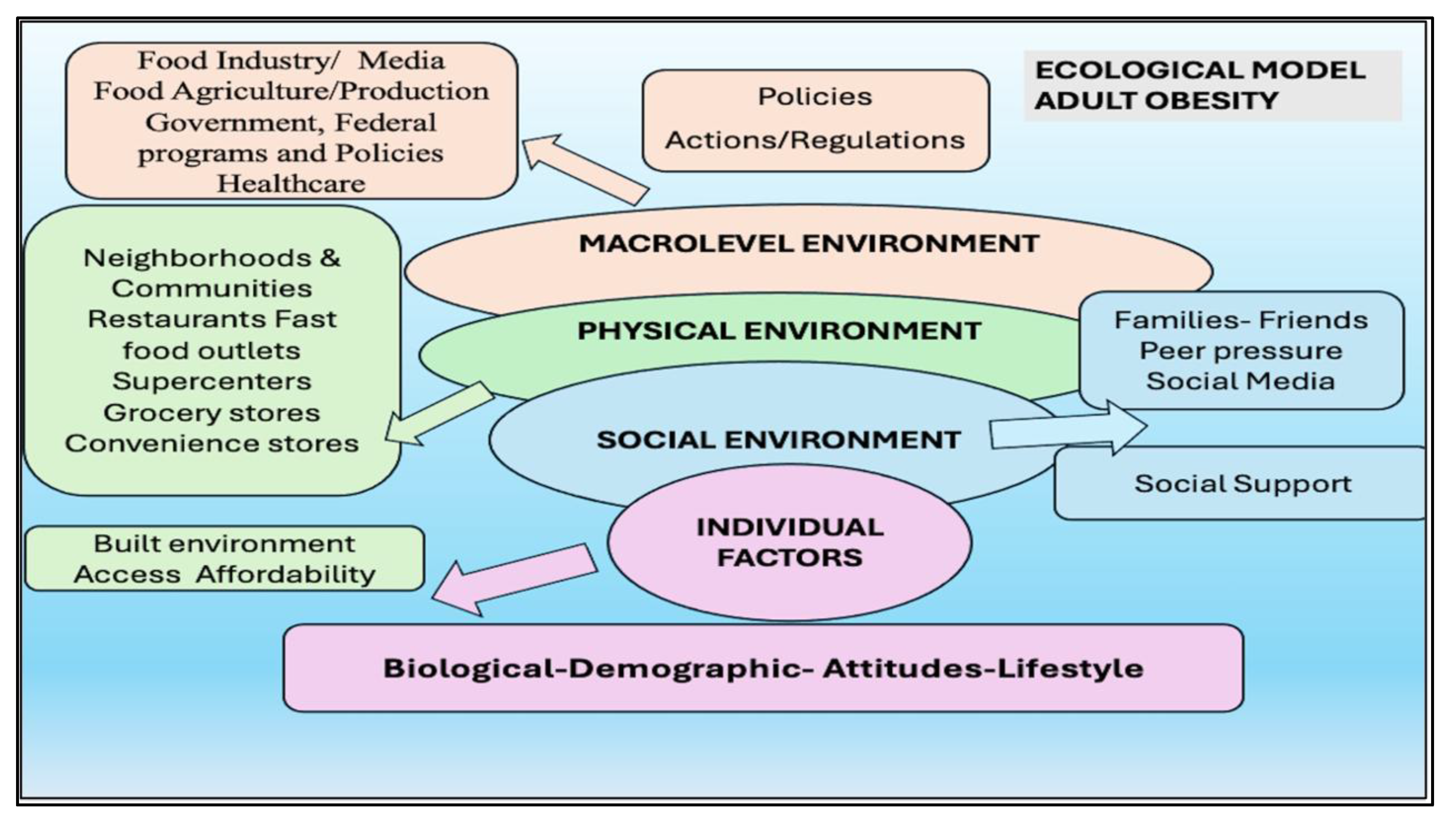

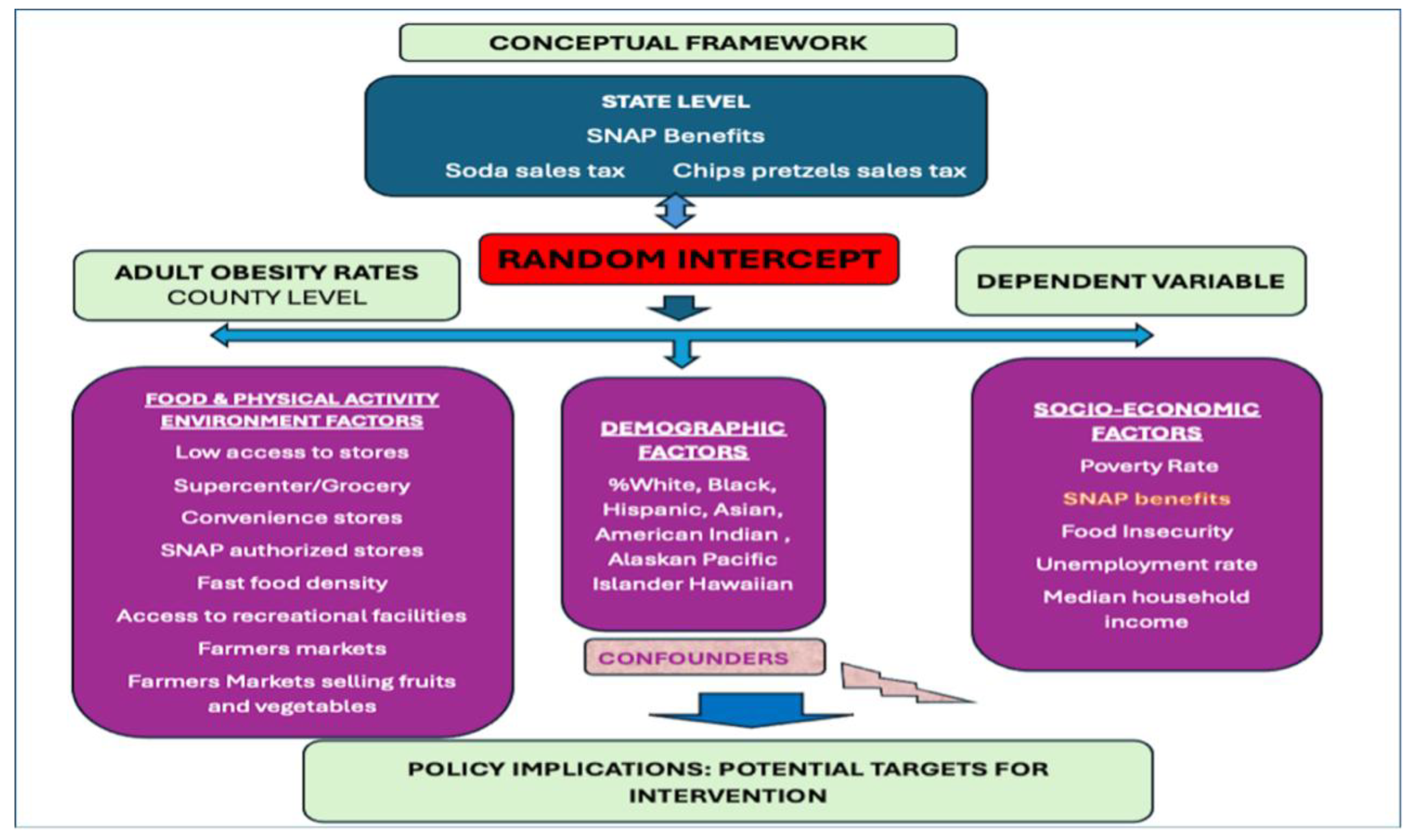

2.3. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

2.4. Variables and Measures

Access Measures

Socioeconomic variables

Demographics variables

Policy leveraged variables

2.5. Centering and Preprocessing

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Multilevel Model Specification

Combined Model:

3. Results

3.1. Model Fit and Justification

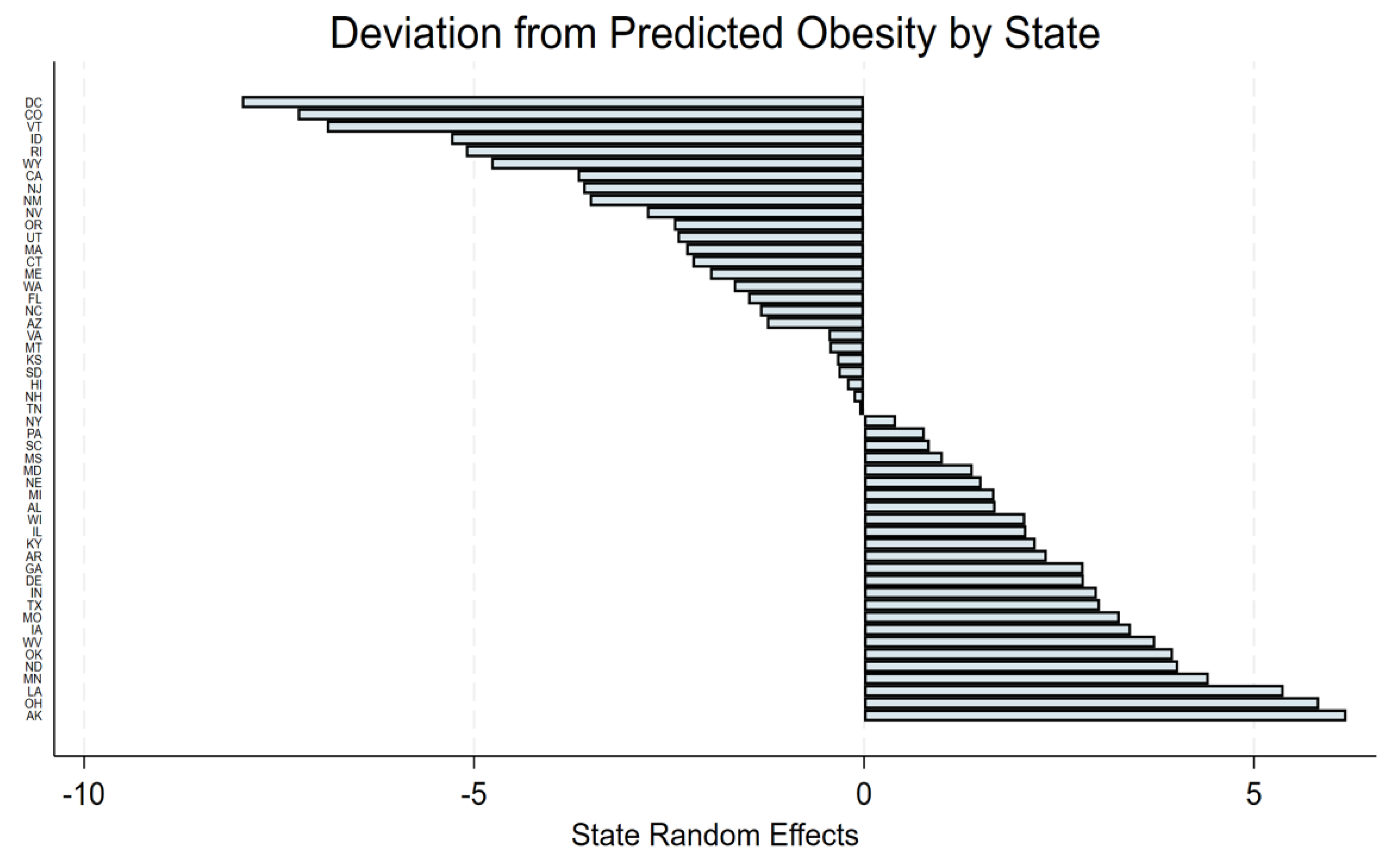

3.2. State-Level Random Effects

3.3. Fixed Effects Results

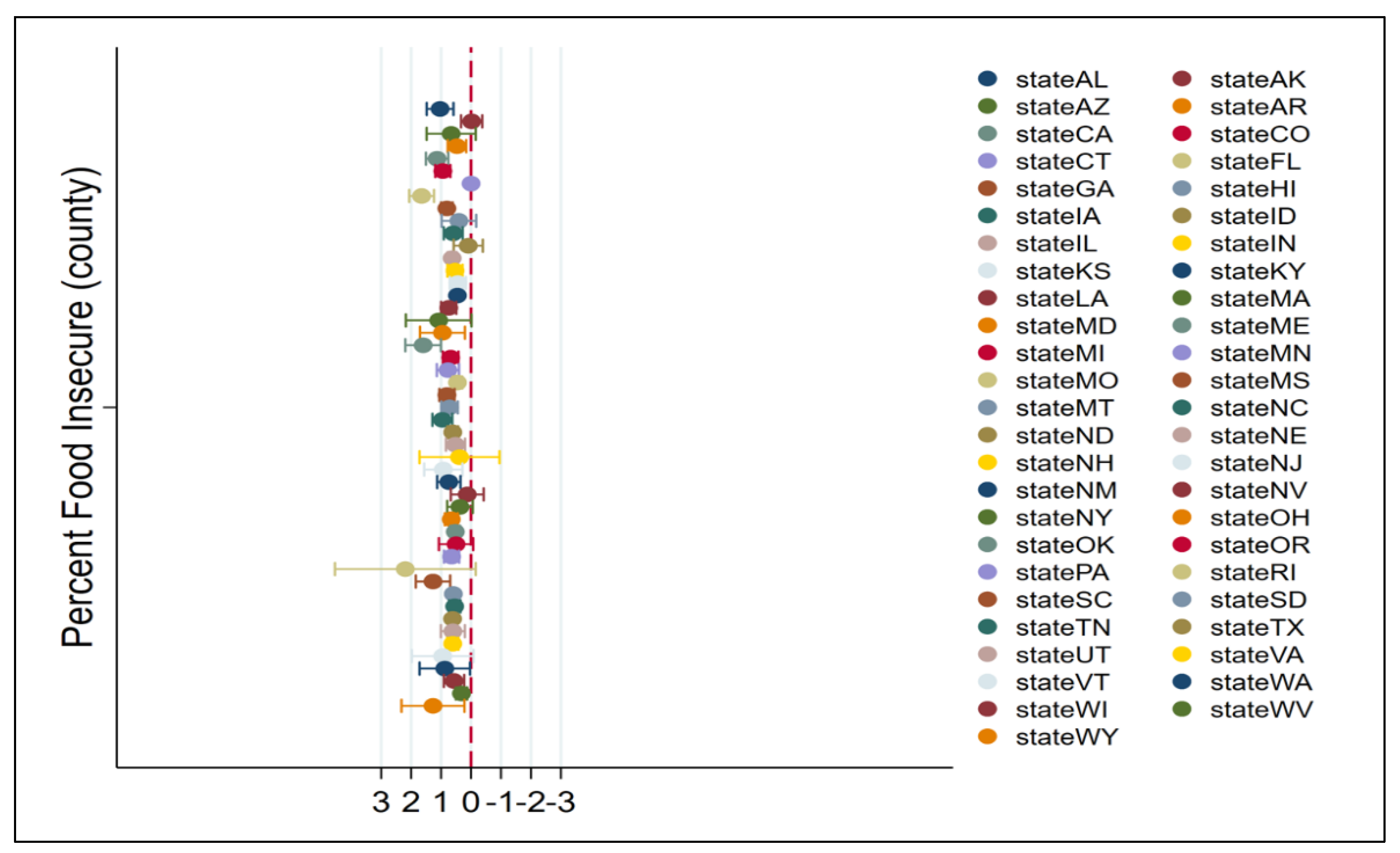

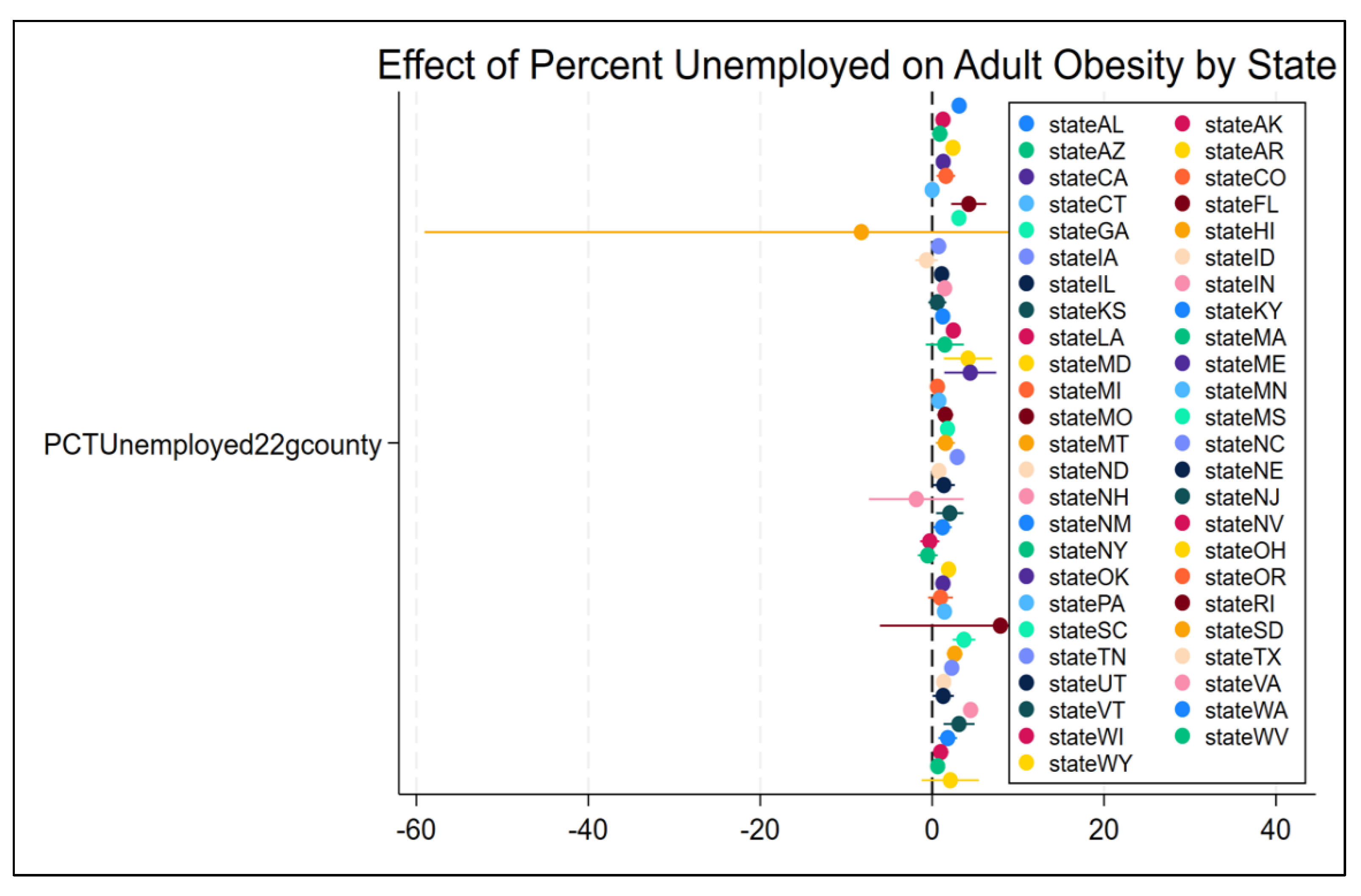

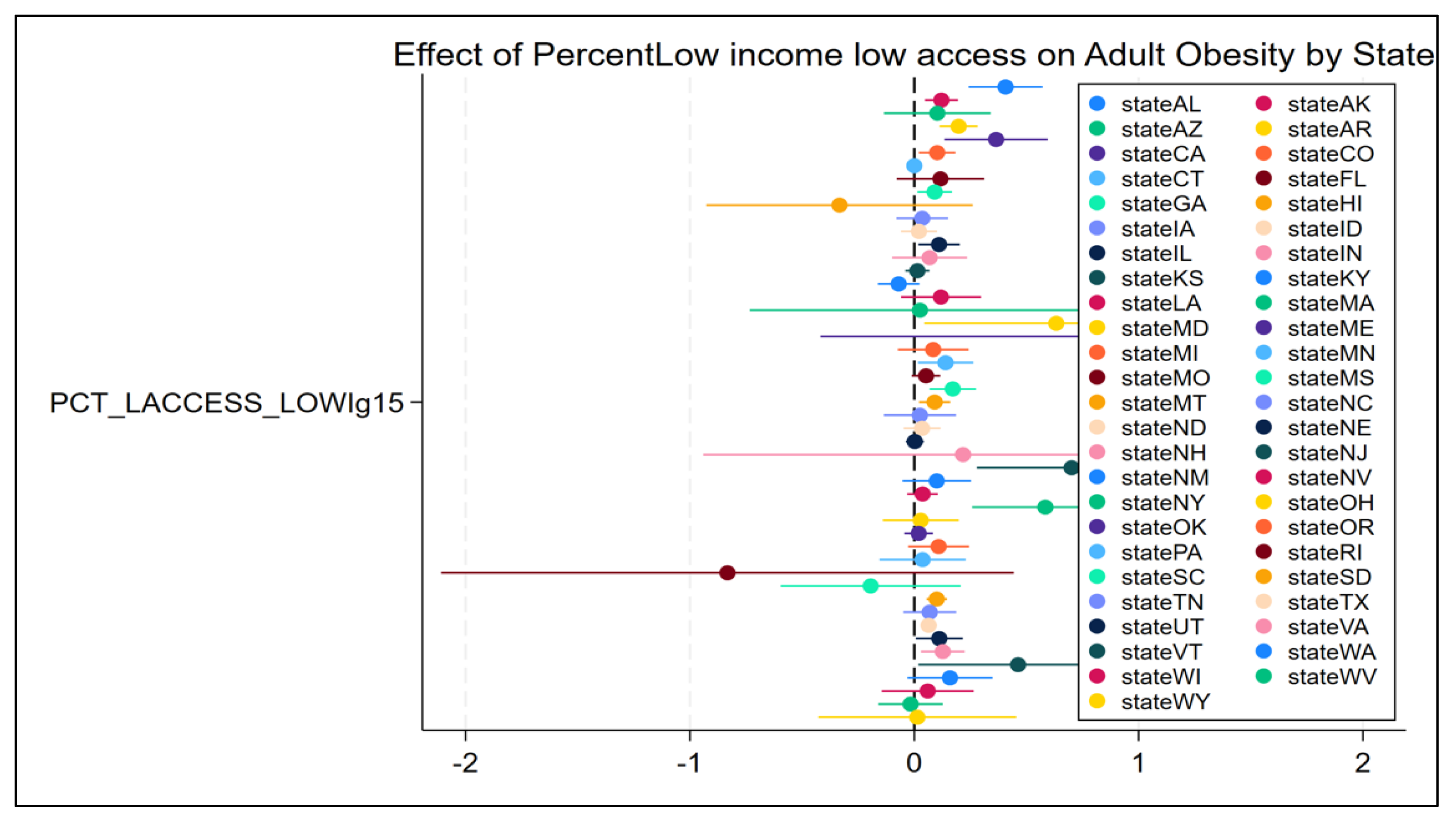

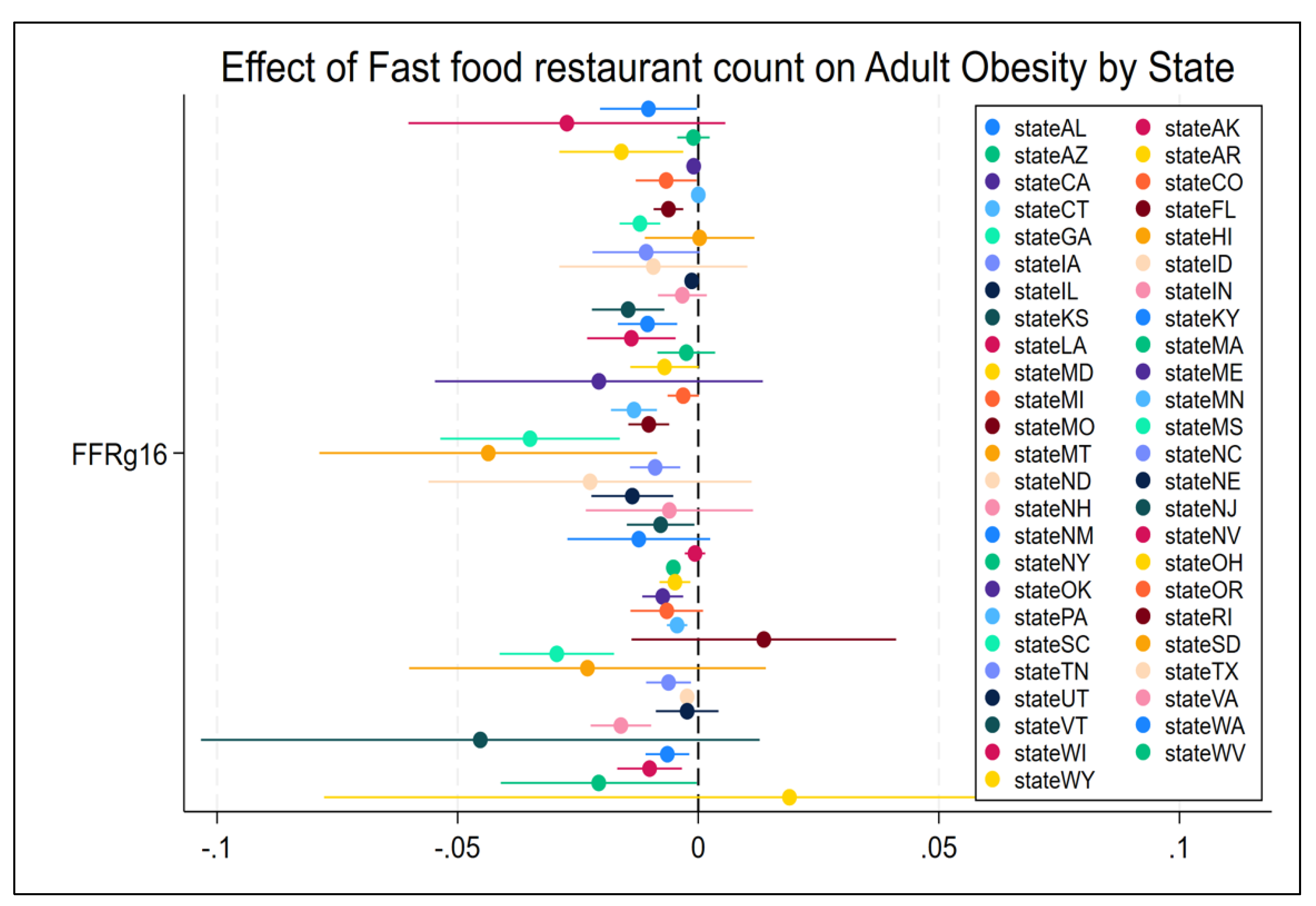

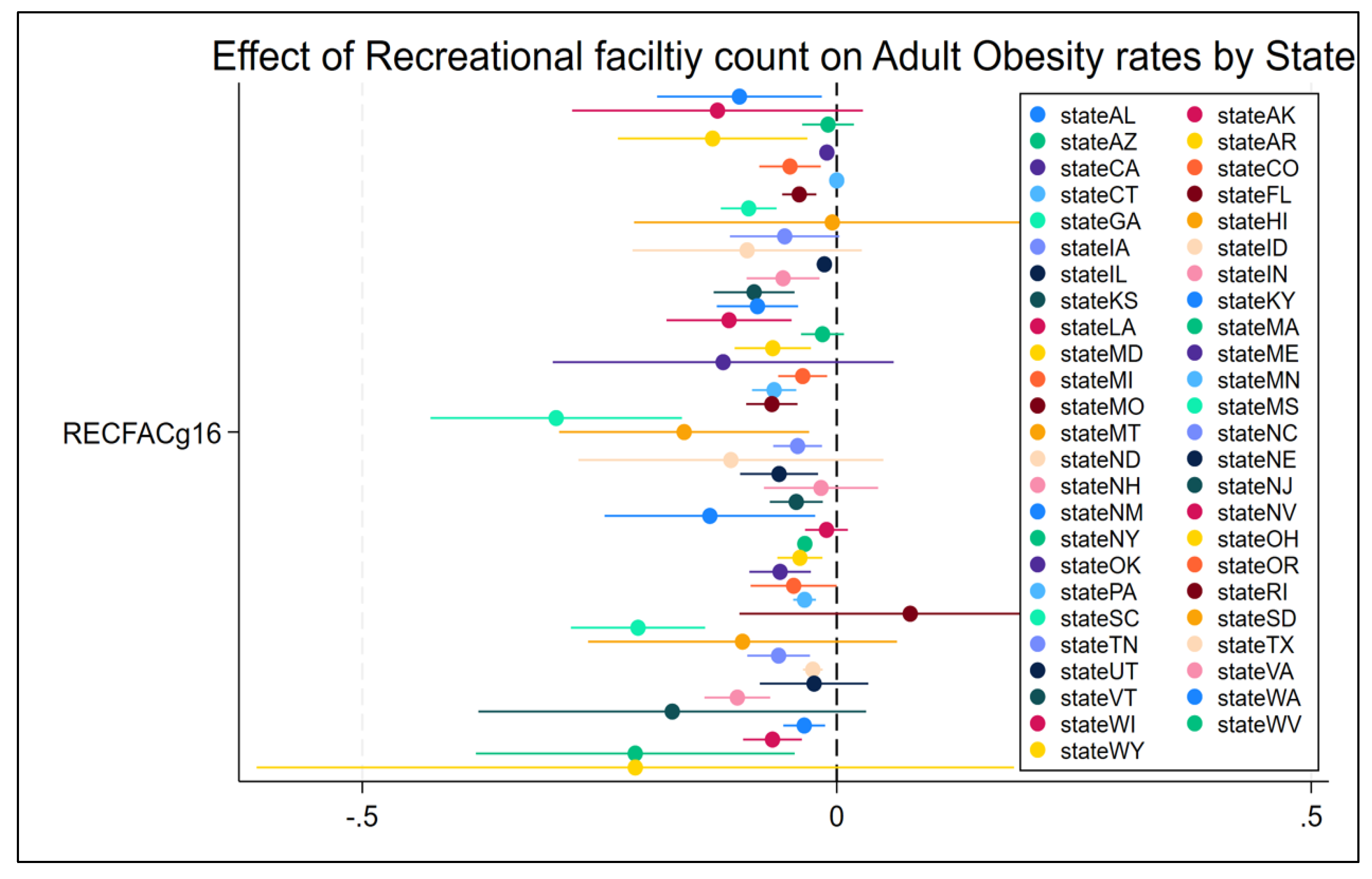

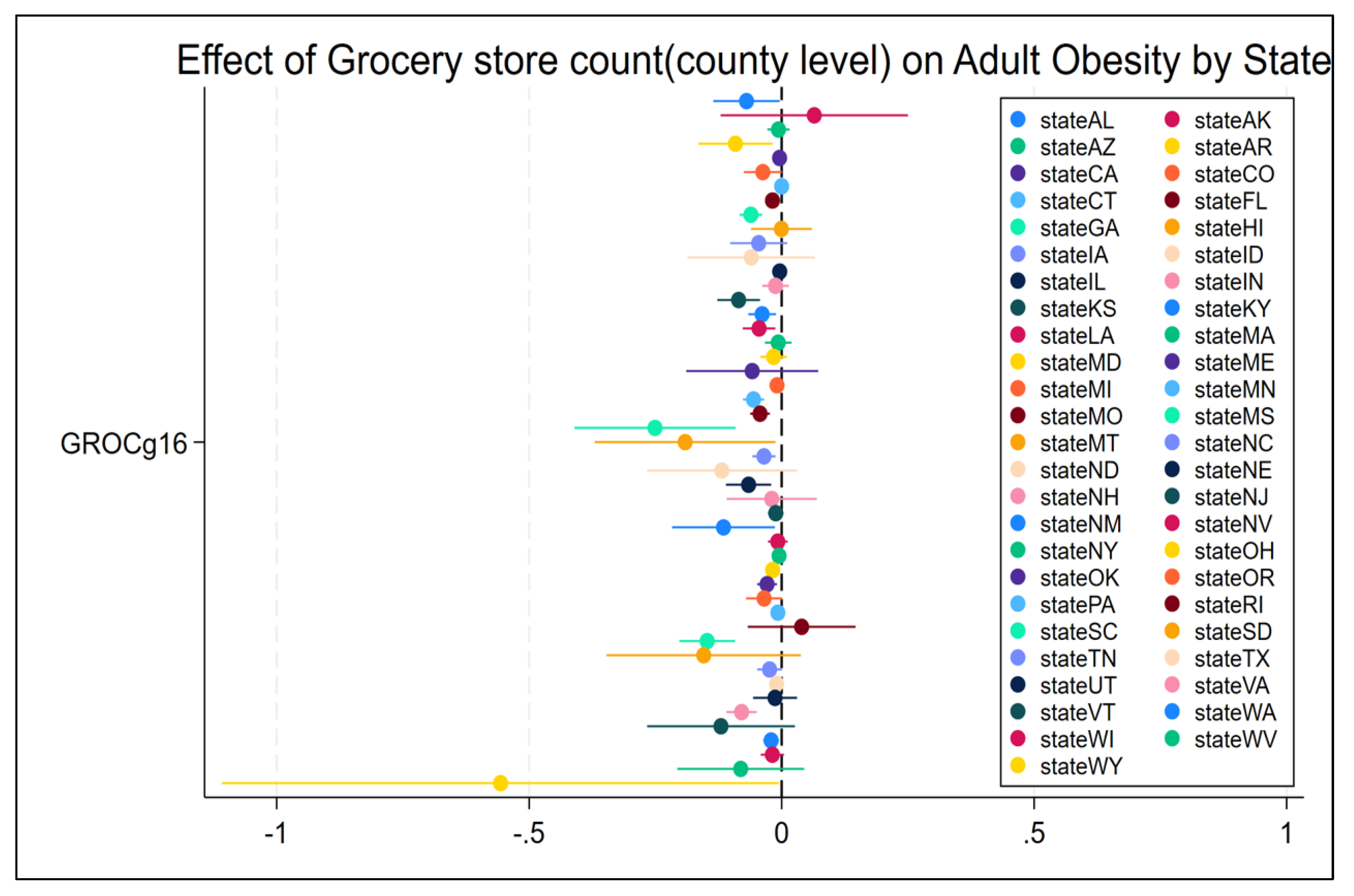

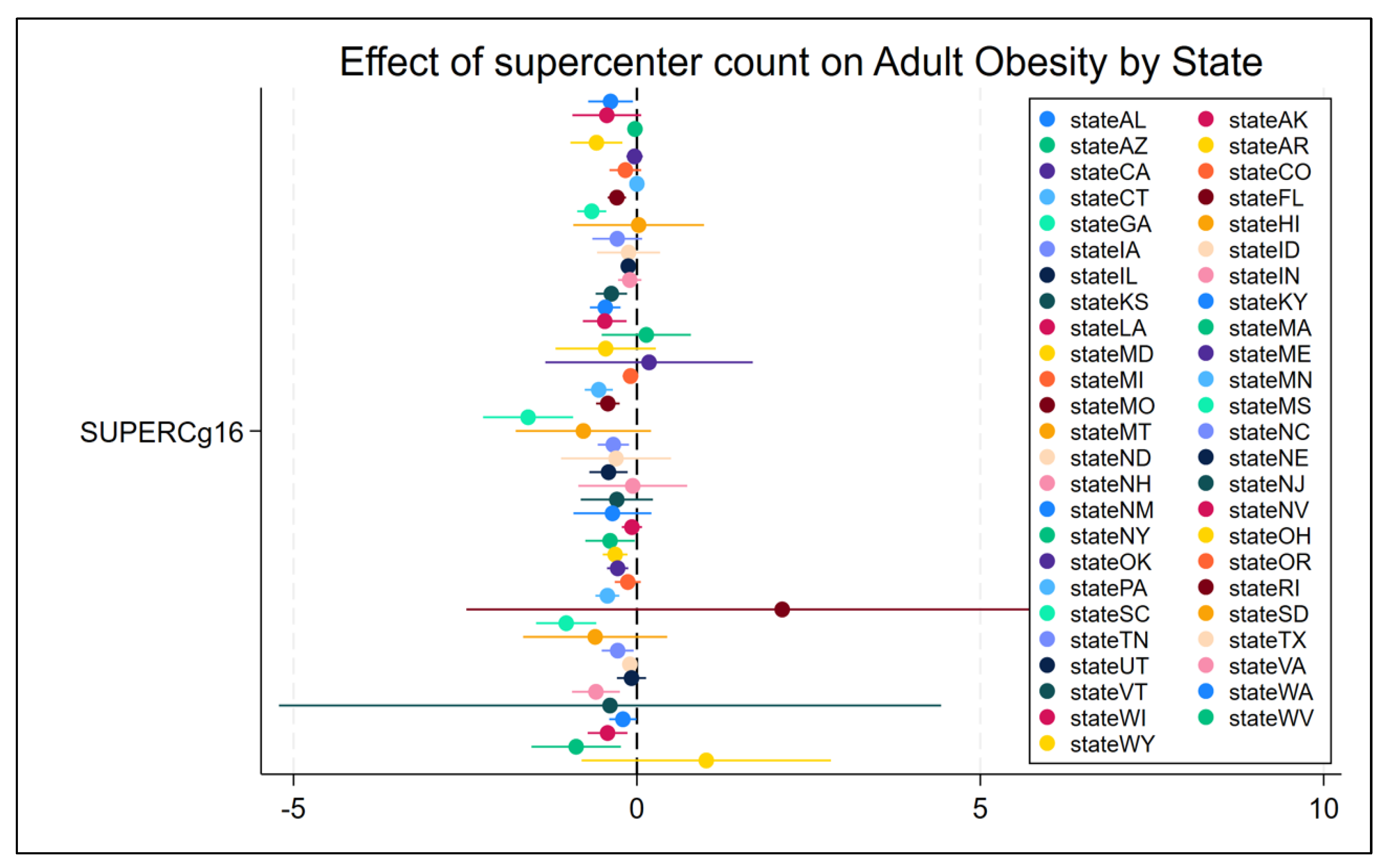

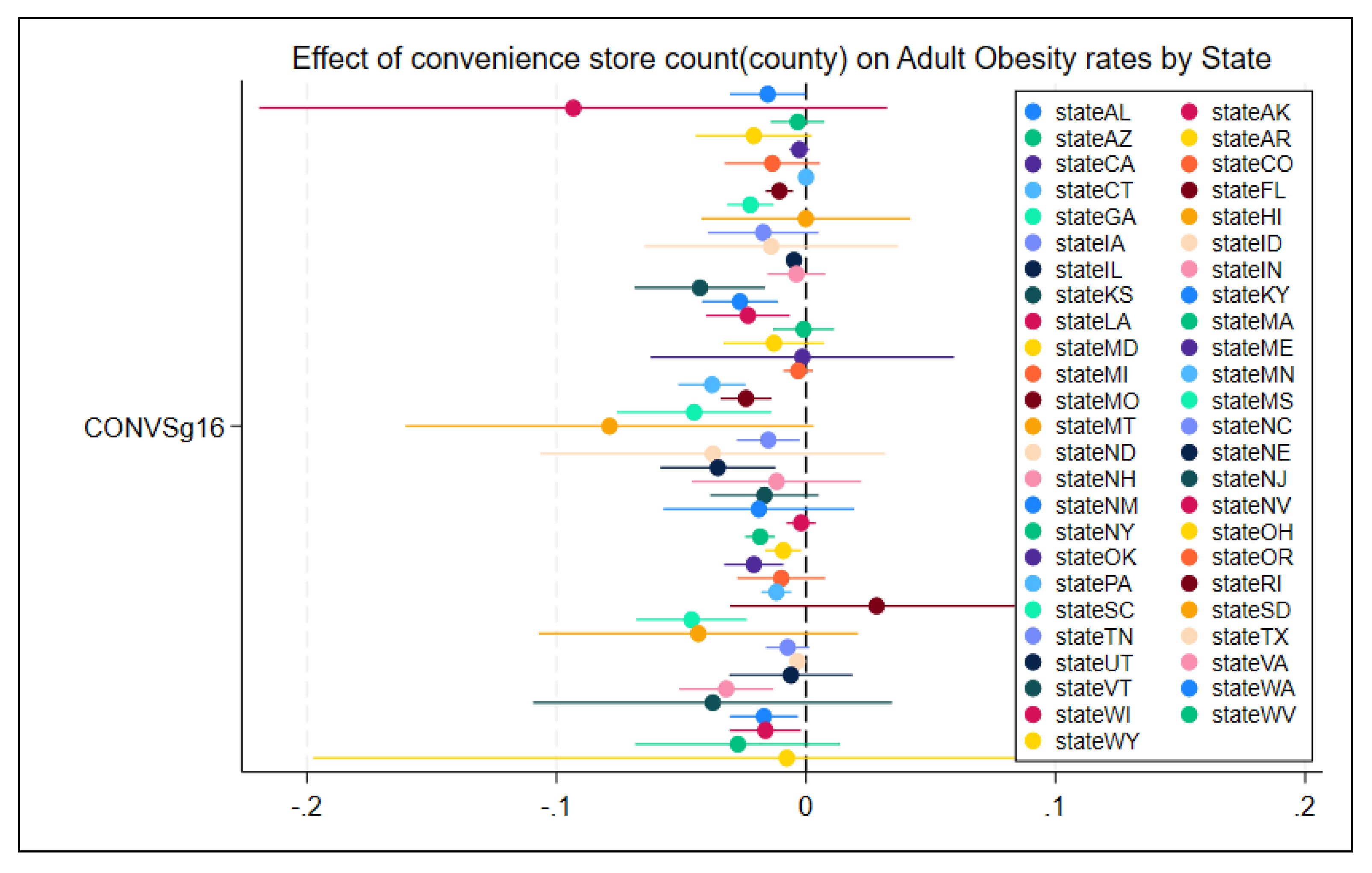

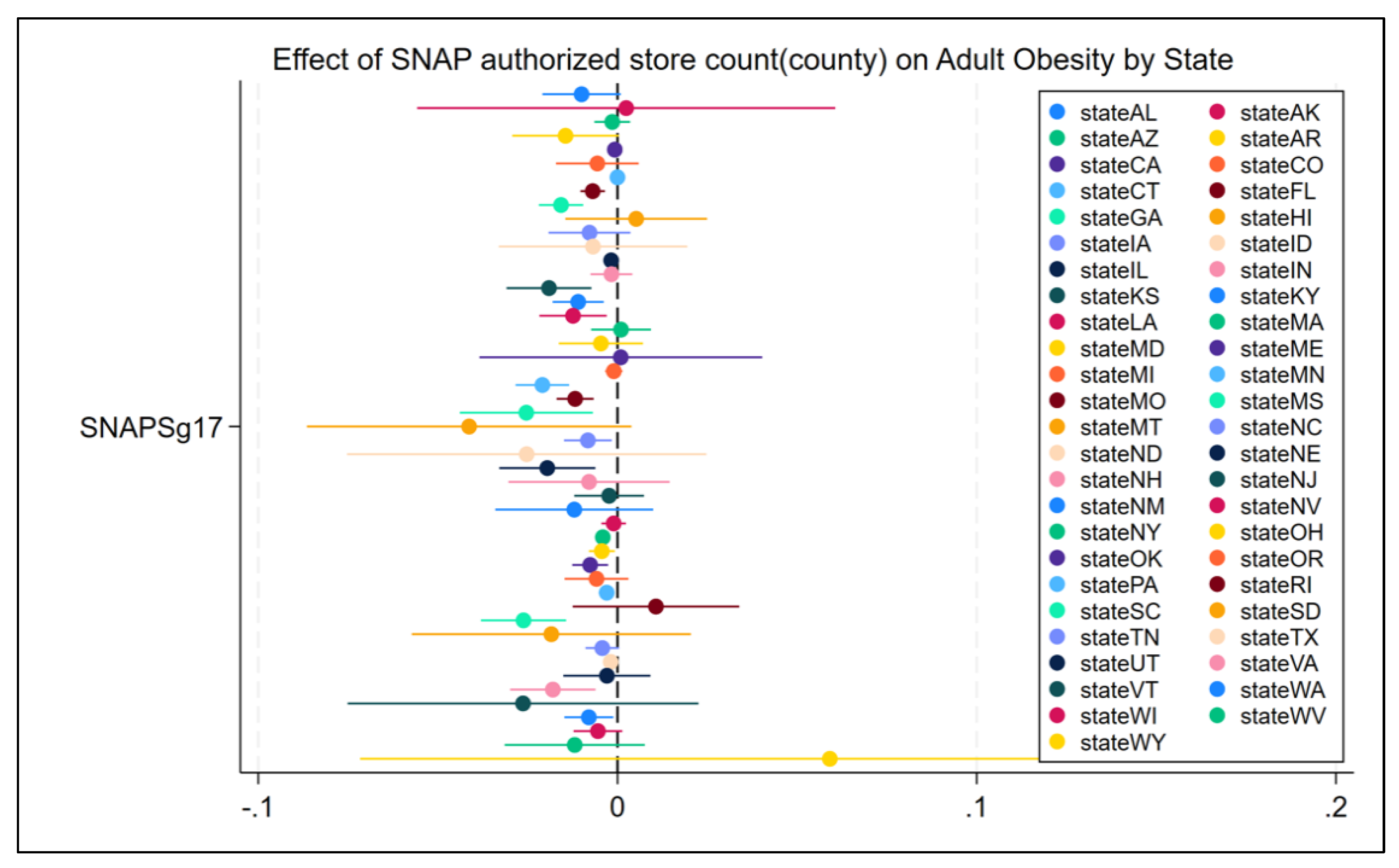

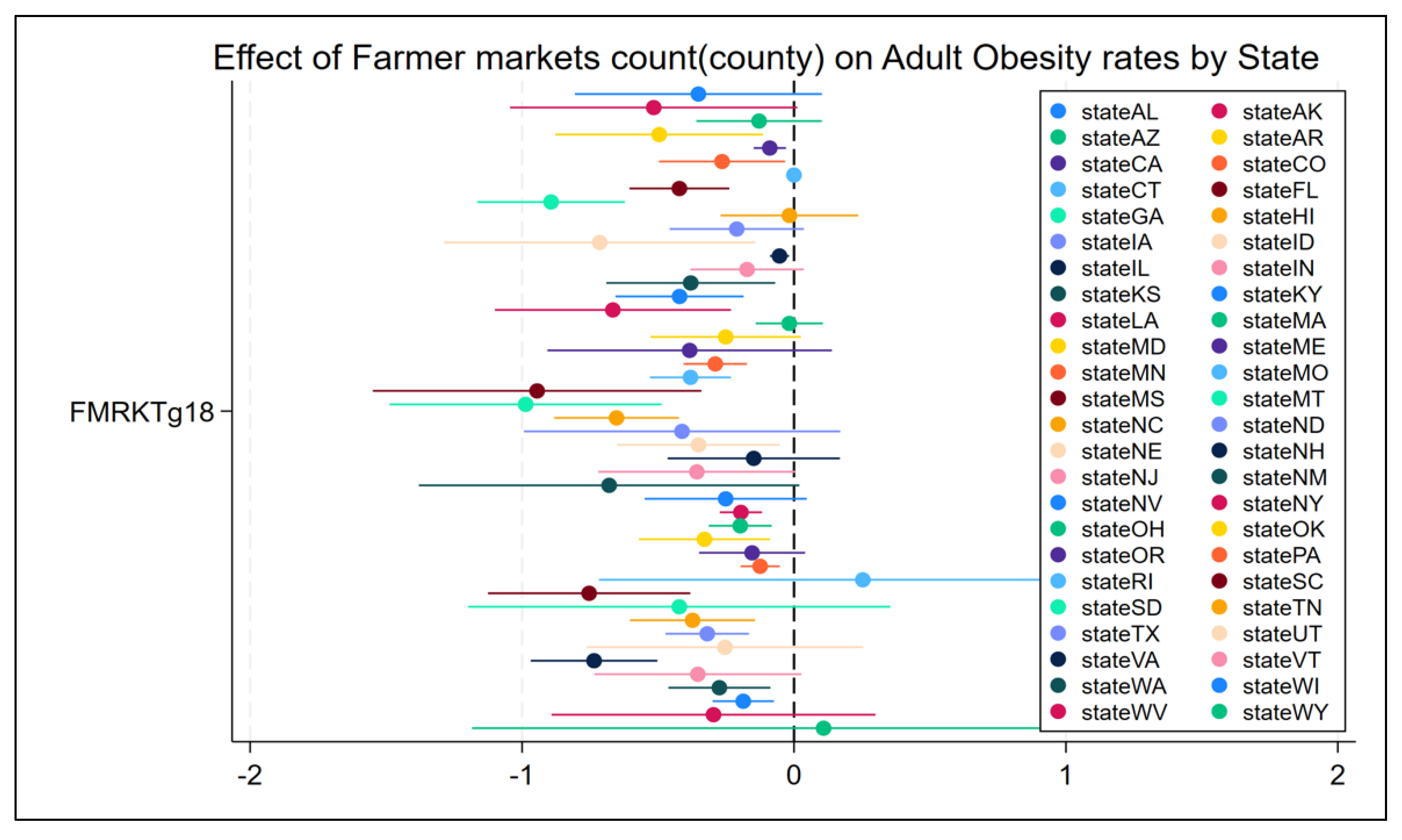

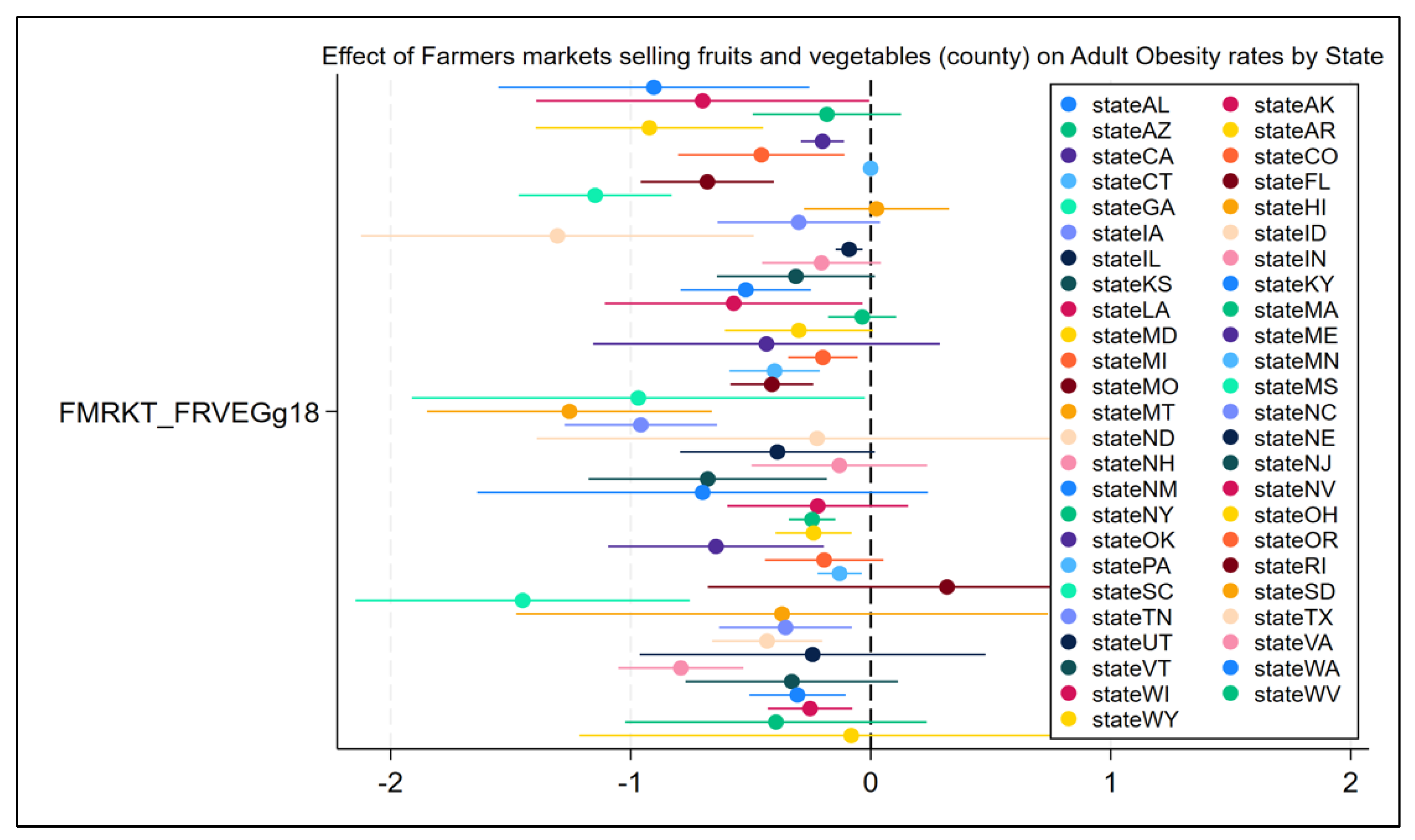

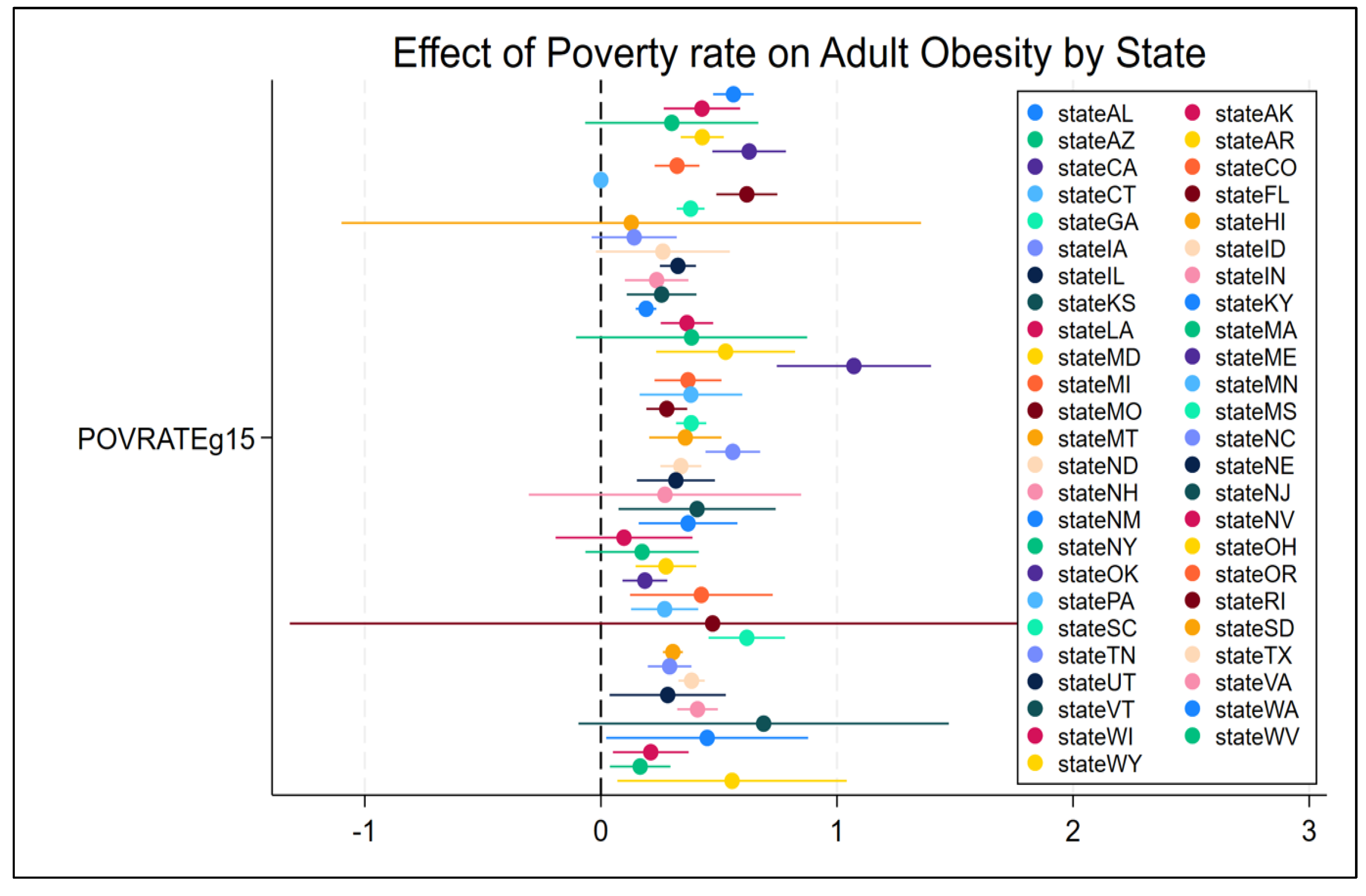

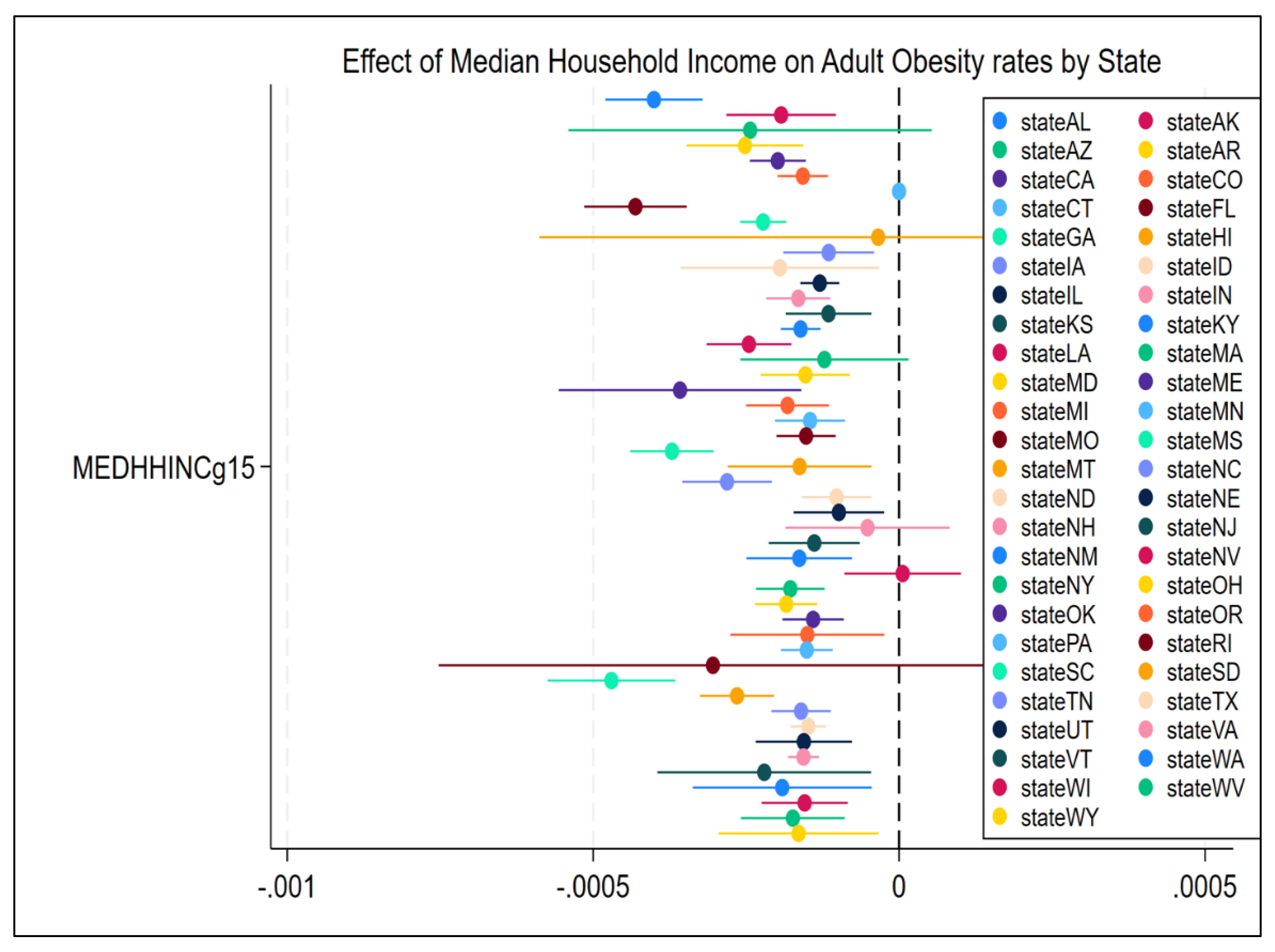

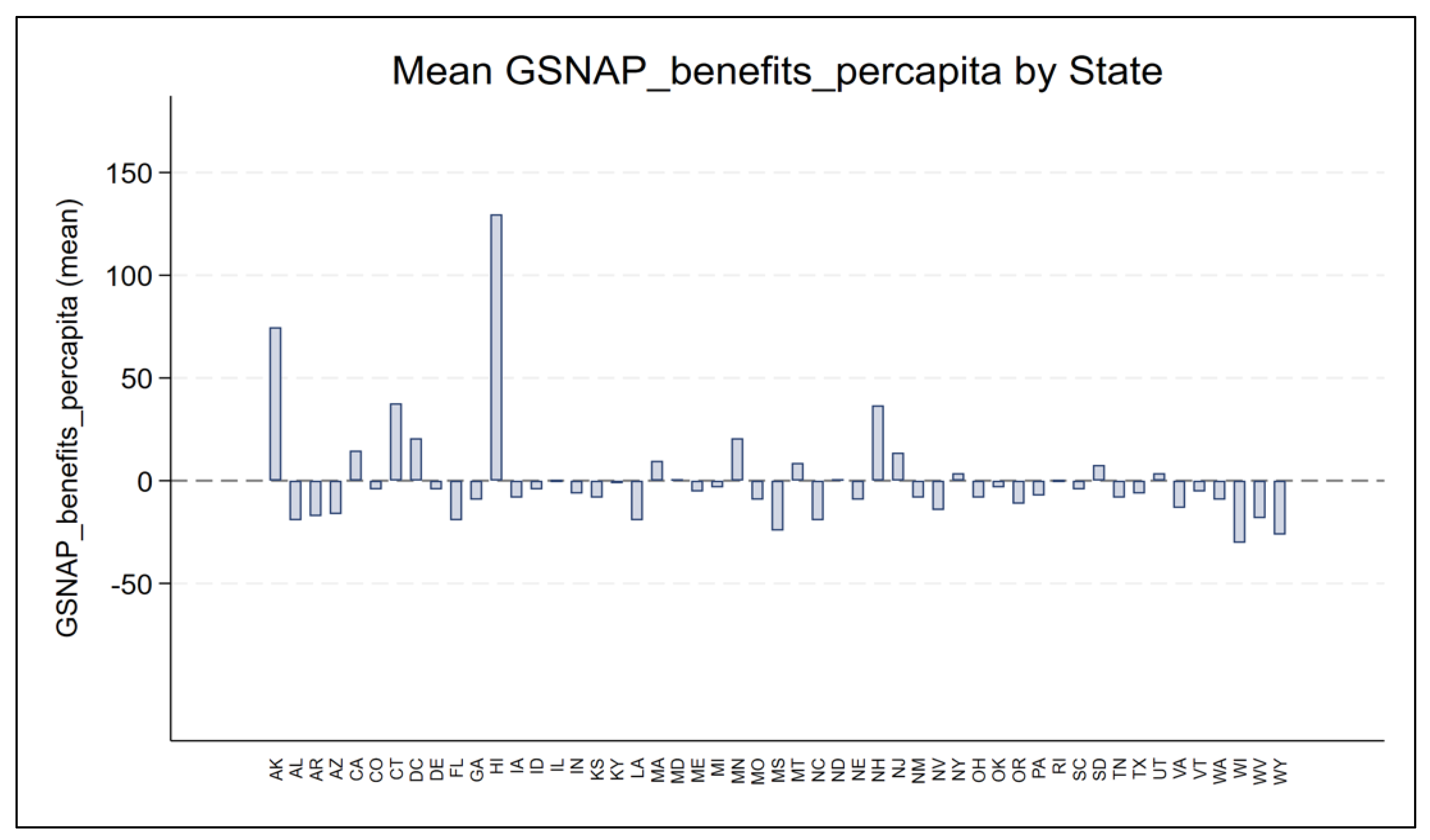

3.4. State-Level Heterogeneity in Key Predictors: Coefficient Plot Exploration

4. Discussion

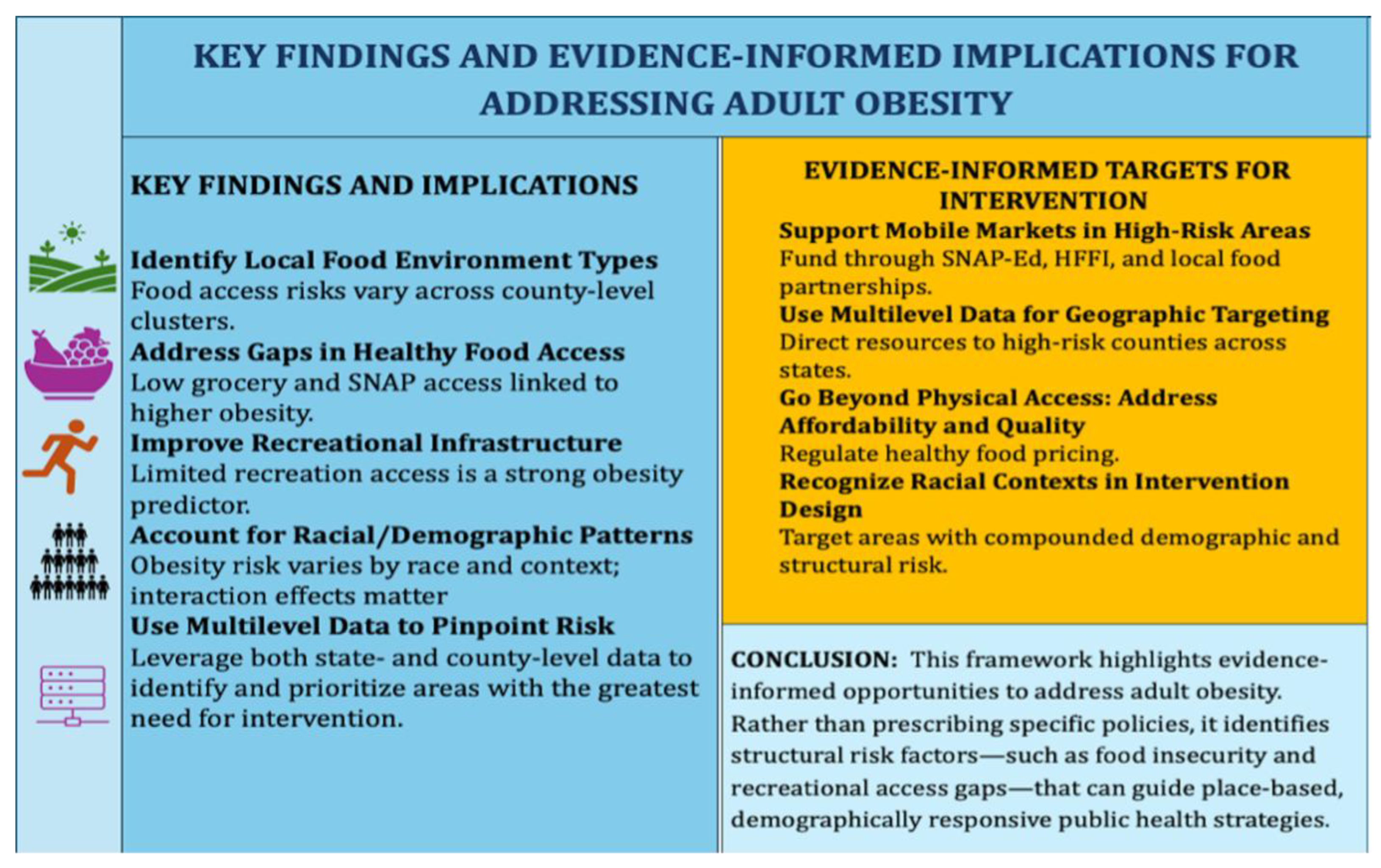

4.1. Guiding Strategies for Addressing Adult Obesity Through Food and Environmental Policy

5. Summary and Conclusion

6. Scope and Limitations

7. Recommendations for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDC | Center of Disease Control and Prevention |

| SNAP USDA | Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. United States Department of Agriculture |

| PLACES | Population Level Analysis and Community Estimates. |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| VARIABLE | COEFF. | STD. ERROR | p-value | INTERPRETATION |

| Grocery store (GROCg16) |

-0.01 | 0.014 | 0.46 | Not statistically significant; no clear evidence grocery store density affects obesity rates. |

| Farmers market (FMRKTg18) |

-0.006 | 0.0096 | 0.55 | Not statistically significant; no significant association with obesity. |

| Farmers market selling fruits and vegetables (FMRKT_FRVEGg18) |

-0.0 | 0.009 | 0.13 | Not statistically significant; no significant effect. |

| Fast-food Restaurants. (FFRg16) | 0.0612 | 0.014 | 0.00 | A 1- unit increase in Fast food density (FFRg16) is associated with a 0.0612 percentage point increase in adult obesity rates. Significant positive; more fast-food restaurants linked to higher obesity rates. |

| Supercenter (SUPERCg16) |

-0.053 | 0.019 | 0.01 | A 1- unit increase in Supercenter density (SUPERCg16) is associated with a 0.053 percentage point decrease in adult obesity rates. Significant negative; more supercenters linked to lower obesity, contrary to hypothesis. |

| Convenience Stores (CONVSg16) |

0.0885 | 0.019 | 0.001 | A 1-unit increase in Convenience store density (CONVSg16) is associated with a 0.0885 percentage point increase in adult obesity rates. Significant positive; more convenience stores associated with higher obesity. |

|

% low access to stores, low income. (PCT_LACCESS_LOWIg15) |

0.169 |

0.034 |

0.001 |

A 1 percentage point increase low-income households with low access to stores (PCT_LACCESS_LOWIg15) is associated with a 0.1686 percentage point increase in adult obesity rates. This significant positive association indicates that limited access to food outlets is linked to higher obesity prevalence. |

| (RECFACg16) Recreational facilities. |

-0.028 | 0.006 | 0.001 | A 1-unit increase in Recreational facilities density (RECFACg16) is associated with a 0.0276 percentage point decrease in adult obesity rates. Significant negative; more recreational facilities linked to lower obesity. |

| SNAP authorised stores (SNAPSg17) |

0.002 | 0.001 | 0.09 | The result is not statistically significant. |

| SNAP benefits per capita (GSNAP_benefits_percapita) |

-0.058 | 0.01 | 0.001 | A 1-unit increase in GSNAP_benefits_percapita is associated with a 0.0575 percentage point change in adult obesity rates. Significant negative; higher SNAP benefits per capita linked to lower obesity. |

| Soda tax stores (GSODATAX_STORES14) |

-0.378 | 0.293 | 0.21 | Not statistically significant. |

| Chips/Pretzel tax stores (GCHIPSTAX_STORES14) |

-0.712 | 0.474 | 0.13 | Not statistically significant. |

| Soda tax vending machine (GSODATAX_VENDM14) |

0.207 | 0.653 | 0.76 | Not statistically significant. |

| Chips/Pretzel tax vending machine (GCHIPSTAX_VENDM14) |

-0.527 | 0.396 | 0.19 | Not statistically significant. |

| % Food insecurity (PCTFoodInsecure21gCounty) |

0.282 | 0.009 | 0.001 | Statistically significant. A 1 percentage point increase in county-level food insecurity is associated with a 0.28 percentage point increase in adult obesity, supporting the hypothesis that greater food insecurity contributes to higher obesity rates. |

| % Unemployed (PCTUnemployed22gcounty) |

0.196 | 0.02 | 0.001 | A 1 percentage point increase in county-level unemployment is associated with a 0.1958 percentage point increase in adult obesity rates. This strong positive association supports the hypothesis that economic insecurity contributes to obesity risk. |

|

Race/Ethnicity Controls |

||||

| % Asian (PCT_ASg23) |

-0.158 | 0.02 | 0.00 | A 1 percentage point increase in Asian (PCT_AIANG21g) is associated with a 0.158 percentage point decrease in adult obesity rates. Significant negative; higher Asian population linked to decreased obesity. |

| % American Indian Alaskan Native (PCT_AIANg23) |

0.185 | 0.022 | 0.001 | A 1 percentage point increase in American Indian Alaskan native (PCT_AIANG21g) is associated with a 0.1848 percentage point increase in adult obesity rates. Significant positive; higher American Indian/Alaskan Native population linked to increased obesity. |

| % Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander (PCT_NHPIg23) |

-0.023 | 0.057 | 0.69 | Not statistically significant. |

| % Hispanic (PCT_H23g) |

0.121 | 0.015 | 0.001 | A 1 percentage point increase in Hispanics (PCT_Hisp21g) is associated with a 0.121 percentage point increase in adult obesity rates. Significant positive; higher Hispanic population linked to increased obesity. |

| % Non-Hispanic Black (PCT_NHBg23) |

0.025 | 0.01 | 0.02 | A 1 percentage point increase in Non-Hispanic Black (PCT_NHBg23) is associated with a 0.025 percentage point increase in adult obesity rates. Significant positive; more Non-Hispanic Black residents linked to higher obesity. |

| % Non-Hispanic White (PCT_NHWg23) |

-0.02 | 0.009 | 0.03 | A 1 percentage point increase in Non- Hispanic Whites (PCT_NHWg23) is associated with a 0.02 percentage point decrease in adult obesity rates. Significant negative; more Non-Hispanic White residents linked to lower obesity. |

| Median household income (MEDHHINCg15) |

-0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.001 | A 1-unit increase in Median Household Income (MEDHHINCg15) is associated with a 0.0004 percentage point decrease c in adult obesity rates. Significant negative; higher income linked to lower obesity. |

| Poverty rate (POVRATEg15) |

0.307 | 0.047 | 0.00 | A 1 percentage point increase in Poverty rate (POVRATEg15) is associated with a 0.3065 percentage point increase in adult obesity rates. Significant positive; higher poverty associated with higher obesity. |

Appendix B

| Variable | General Trend | Key Finding |

| Fast-Food Restaurant Density (FFRg16) | Combination of negative and positive, some significant | Fast-food density linked to higher obesity in few states but not in others. |

|

Percent Unemployed (PCTUnemployed22gcounty) |

Mixed, several negative | Unemployment negatively associated with obesity in some states |

|

Percent Food Insecure (PCTFoodInsecure21gCounty) |

Mixed, mostly non-significant | No consistent pattern: some states show weak positive link |

| Percent Low Access to stores + Low Income (PCT_LACCESS_LOWIg15) | Mixed, weak effects | Low-income, low access not consistently associated |

|

Grocery Store (GROCg16) |

Mostly negative, some significant | Greater grocery access linked to lower obesity. In many states, more grocery stores are linked to lower obesity rates, supporting access to healthy food. |

|

Supercenter (SUPERCg16) |

Highly variable, wide CI | Unstable estimates; some positive associations: some states show a link to higher obesity |

|

Convenience Store (CONVSg16) |

Mixed, mostly non-significant | Inconclusive; substitution effects possible ( a substitute to grocery stores with varying impact on dietary quality either positively or negatively, adding complexity to the relationship). |

| SNAP-authorized Stores. (SNAPSg17) | Weak, mixed | SNAP store density not a strong predictor |

|

Recreational Facilities (RECFACg16) |

Mostly negative, some significant | Access to recreation linked to lower obesity in many states |

|

Farmers' Markets (FMRKTg18) |

Mixed, wide CI | Mixed influence; variability across states |

|

Farmers’ Markets selling fruits and vegetables (FMRKT_FRVEGg18) |

Mostly negative, some significant | States with more markets selling fruits/vegetables show reduced obesity in some regions. |

|

Percent American Indian/Alaska Native (PCT_AIANg23) |

Wide CI, mostly non-significant | Estimates unstable due to small subgroup size |

|

Percent Asian Population (PCT_ASg23) |

Mostly negative, some significant | A larger Asian population is often linked to lower obesity rates, consistent with national trends |

|

Percent Hispanic Population (PCT_Hg23) |

Mixed, few negative | Some states show lower obesity with higher Hispanic population, though effects vary. |

|

Percent Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (PCT_NHPIg23) |

Wide CI, outliers present | High variability due to small populations |

|

Percent Non-Hispanic Black (PCT_NHBg23) |

Mixed, slightly positive | Some positive associations observed: Some states show increased obesity with higher Black population; not uniform. |

|

Percent Non-Hispanic White (PCT_NHWg23) |

Mostly negative. | Generally protective : Higher White population linked to lower obesity |

|

Median Household Income (MEDHHINCg15) |

Strongly negative in most states | Consistently associated with lower obesity prevalence; higher income is a protective factor. |

|

Poverty Rate (POVRATEg15) |

Mixed, some positive | Poverty shows variable influence; some states show higher obesity with higher poverty. |

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Obesity Consequences. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/basics/consequences.html (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult Obesity Facts. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult-obesity-facts/index.html (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. PLACES: Local Data for Better Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/places (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Walker, R.E.; Keane, C.R.; Burke, J.G. Disparities and access to healthy food in the United States: A review of food deserts literature. Health Place 2010, 16, 876–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michimi, A.; Wimberly, M.C. Natural environments, obesity, and physical activity in nonmetropolitan areas of the United States. J. Rural Health 2012, 28, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michimi, A.; Wimberly, M.C. The food environment and adult obesity in US metropolitan areas. Geospat. Health 2015, 10, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morland, K.B.; Evenson, K.R. Obesity prevalence and the local food environment. Health Place 2009, 15, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morland, K.; Diez Roux, A.V.; Wing, S. Supermarkets, other food stores, and obesity: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006, 30, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukenya, J. Determinants of Food Insecurity in Huntsville, Alabama, Metropolitan Area. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2017, 12, 543–558. [Google Scholar]

- University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps: Obesity Rates and Food Environment Indicators. 2024. Available online: https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/health-data.

- USDA Economic Research Service. Food Environment Atlas Overview. 2024. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-environment-atlas/go-to-the-atlas (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Myers, C.A.; Slack, T.; Martin, C.K.; Broyles, S.T.; Heymsfield, S.B. Change in obesity prevalence across the United States is influenced by recreational and healthcare contexts, food environments, and Hispanic populations. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallis, J.F.; Cerin, E.; Kerr, J.; Adams, M.A.; Sugiyama, T.; Christiansen, L.B.; Schipperijn, J.; Davey, R.; Salvo, D.; Frank, L.D.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Owen, N. Built environment, physical activity, and obesity: Findings from the International Physical Activity and Environment Network (IPEN) Adult Study. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2020, 41, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudzune, K.A.; Doshi, R.S.; Mehta, A.K.; Chaudhry, Z.W.; Jacobs, D.K.; Vakil, R.M.; Lee, C.J.; Bleich, S.N.; Clark, J.M. Effectiveness of policies and programs to combat adult obesity: A systematic review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2018, 33, 1990–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polyzou, E.A.; Polyzos, S.A. Outdoor environment and obesity: A review of current evidence. Metab. Open 2024, 24, 100331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garasky, S.; Mbwana, K.; Romualdo, A.; Tenaglio, A.; Roy, M. Foods Typically Purchased by SNAP Households. United States Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2016. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/research-and-analysis.

- Leung, C.W.; Ding, E.L.; Catalano, P.J.; Villamor, E.; Rimm, E.B.; Willett, W.C. Dietary intake and dietary quality of low-income adults in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 977–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gundersen, C.; Ziliak, J.P. Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 1830–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zepeda, L.; Reznickova, A. Measuring effects of mobile markets on healthy food choices. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2014, 9, 426–439. [Google Scholar]

- Ahern, M.; Brown, C.; Dukas, S. A national study of the association between food environments and county-level health outcomes. J. Rural Health 2011, 27, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownell, K.D.; Farley, T.; Willett, W.C.; Popkin, B.M.; Chaloupka, F.J.; Thompson, J.W.; Ludwig, D.S. The public health and economic benefits of taxing sugar-sweetened beverages. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1599–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, L.M.; Slater, S.; Mirtcheva, D.; Bao, Y.; Chaloupka, F.J. Food store availability and neighborhood characteristics in the United States. Prev. Med. 2007, 44, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, K.; Gilliland, J. A spatial analysis of the food environment and obesity in a large urban centre. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 197–203. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, C.; Myers, S.L. Do the poor pay more for food? An analysis of grocery store availability and food price disparities. J. Consum. Aff. 1999, 33, 276–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).