Submitted:

11 October 2025

Posted:

11 October 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Datasets

2.1.1. ChestX-Ray14

2.1.2. CheXpert

2.1.3. MIMIC-CXR

2.1.4. Pediatric Chest X-Ray (Kermany Dataset)

2.2. Preprocessing Techniques

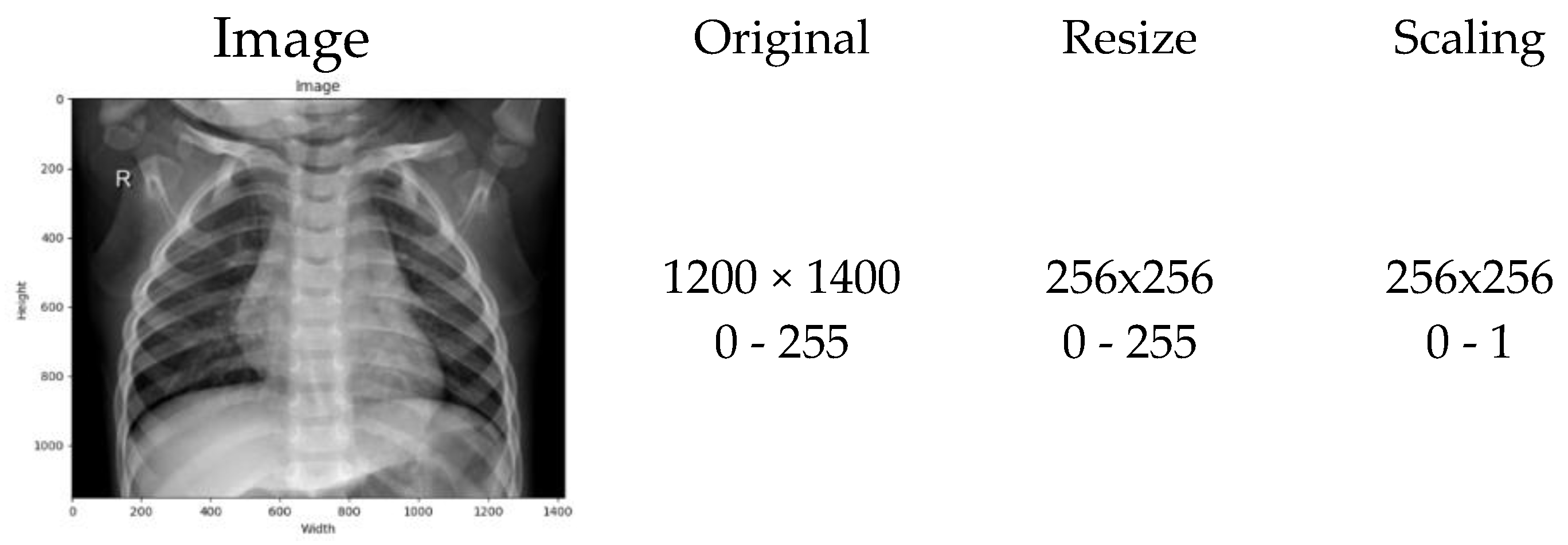

2.2.1. Normalization

2.2.2. Scaling Normalization

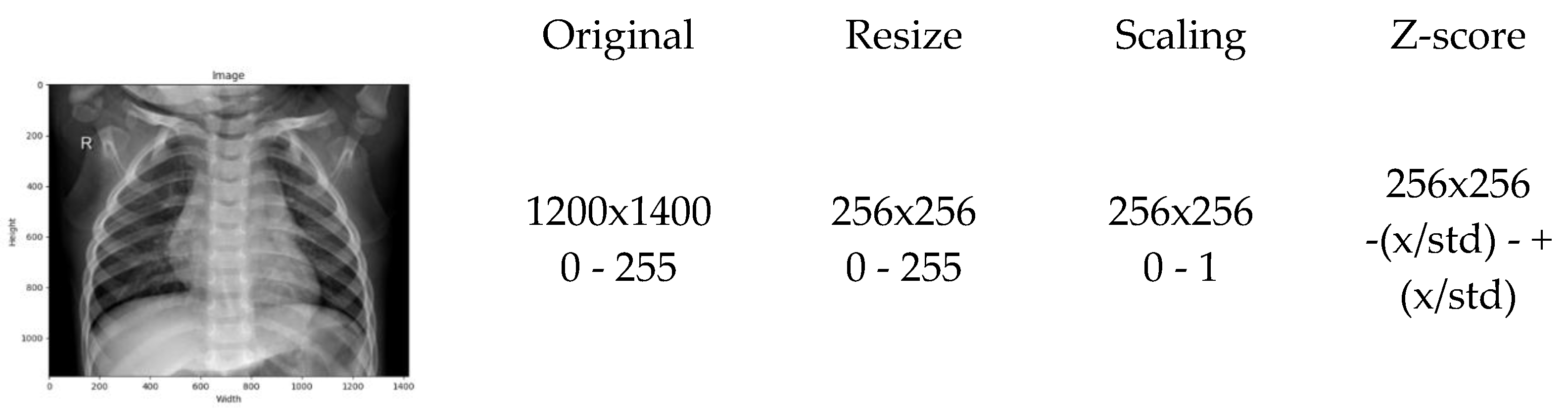

2.2.3. Z-Score Normalization

2.3. Deep Learning Models

2.3.1. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

2.3.2. EfficientNet-B0

2.3.3. MobileNetV2

2.4. Region of Interest and Per-Image Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR)

2.5. Domain Adaptation and Histogram Harmonization

2.6. Comparative Analysis of Related Work

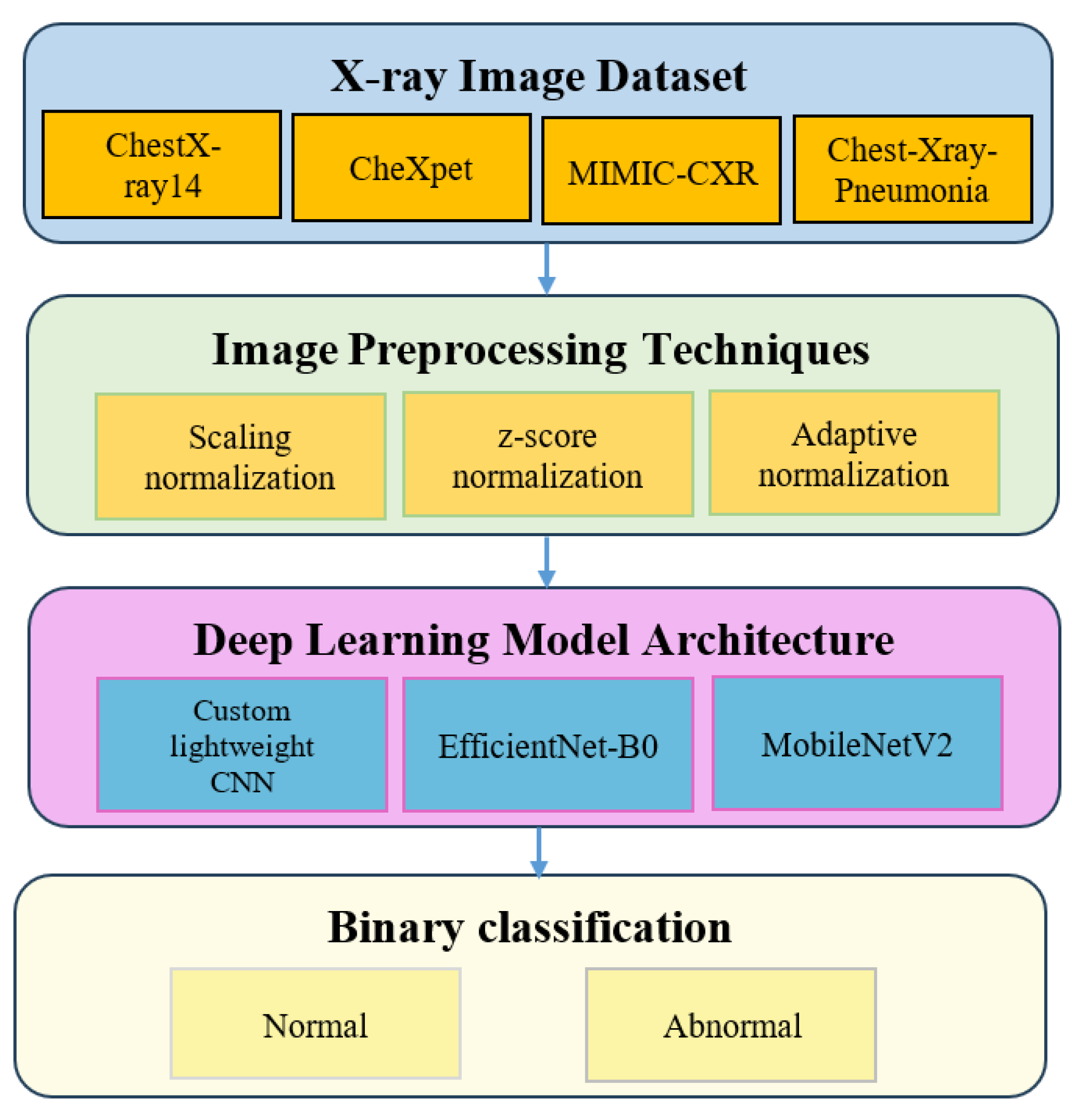

3. Methodology

3.1. Dataset Description

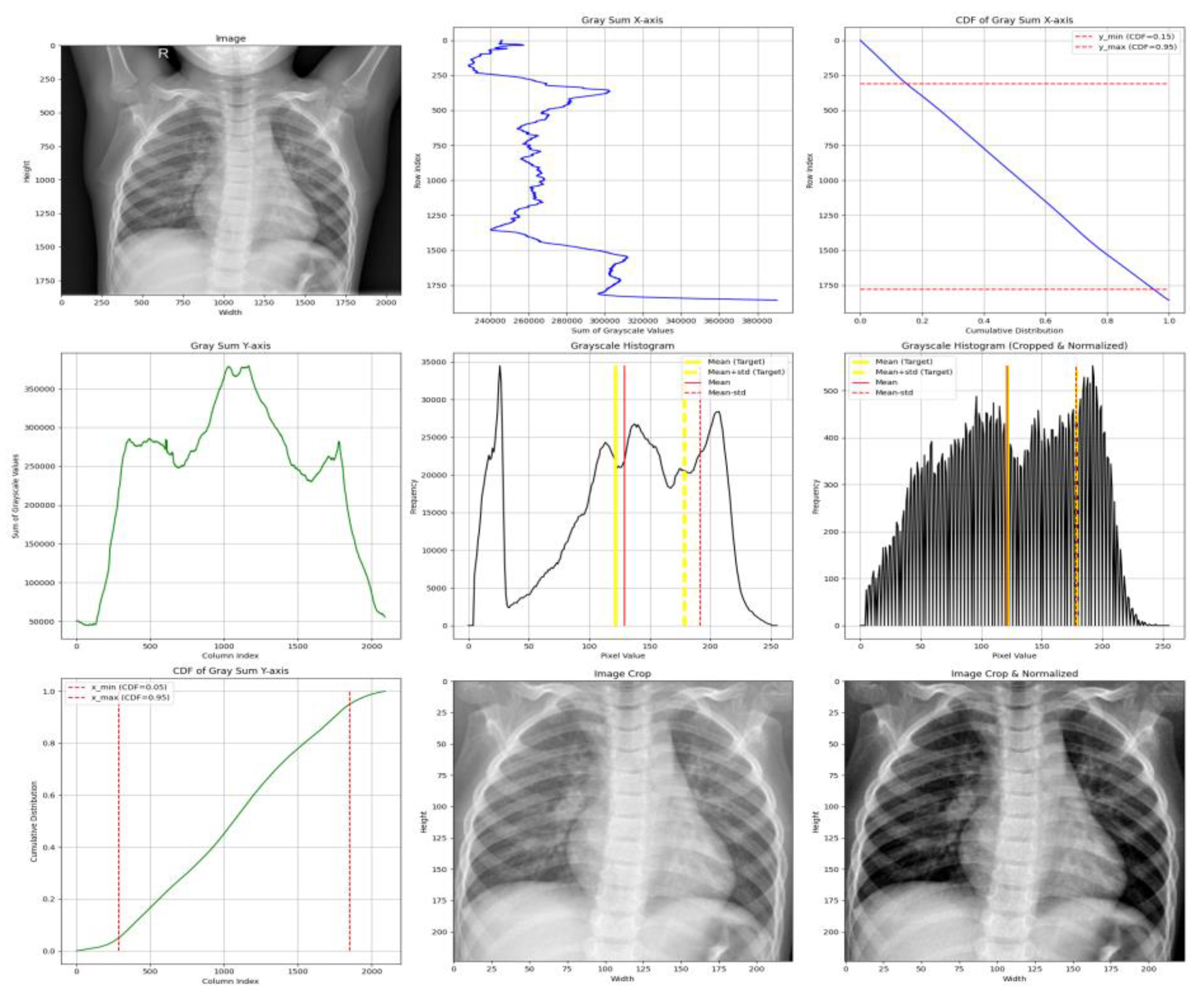

3.2. Image Preprocessing Techniques

- X-axis cropping is performed by computing the grayscale sum per row and selecting the region between the CDF thresholds of 0.05 and 0.95, effectively trimming 5% of the low-density pixels from both lateral sides.

- Y-axis cropping is performed similarly, but within a CDF range of 0.15 to 0.95, to avoid anatomical noise near the neck and upper clavicle.

- We compute the mean () and standard deviation () of grayscale pixel intensities from the cropped image.

- Normalization aims to align the mean and standard deviation with a target distribution, defined by:

- Target Mean: μ_target = 0.4776 × 255 ≈ 121.8

- Target Std. Dev: σ_target = 0.2238 × 255 ≈ 57.1

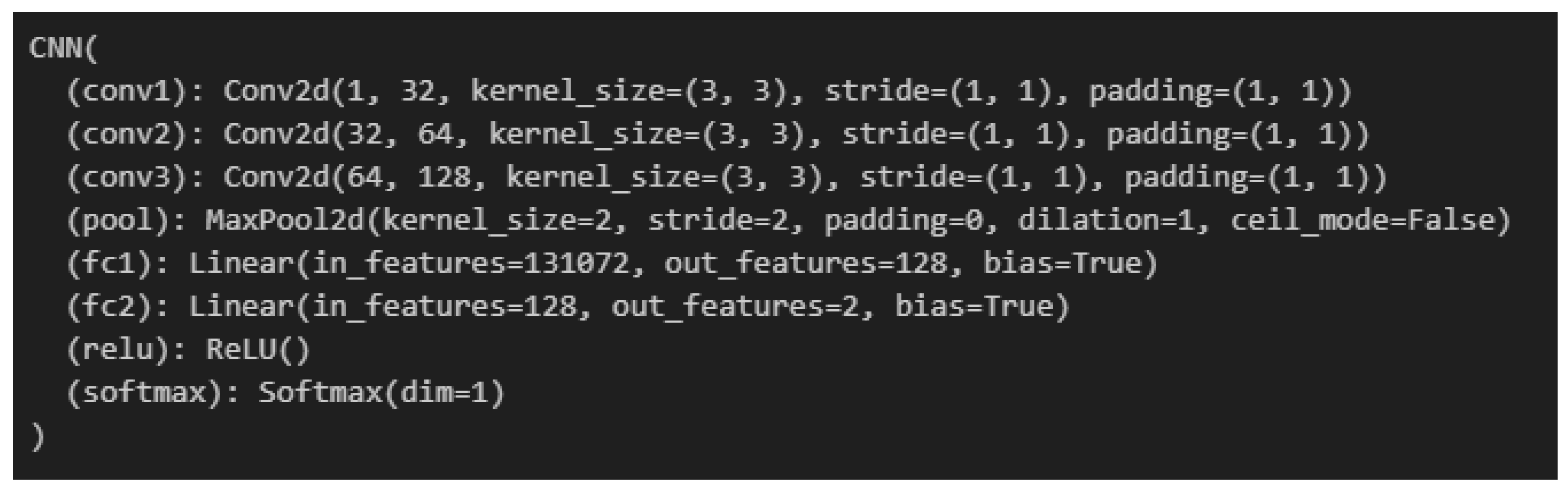

3.3. Deep Learning Model Architecture

3.4. Experimental Design

3.5. Evaluation Metrics and Performance Formulas

3.5.1. Accuracy

3.5.2. F1-Score

3.6. Statistical Significance Testing

4. Experimental Results

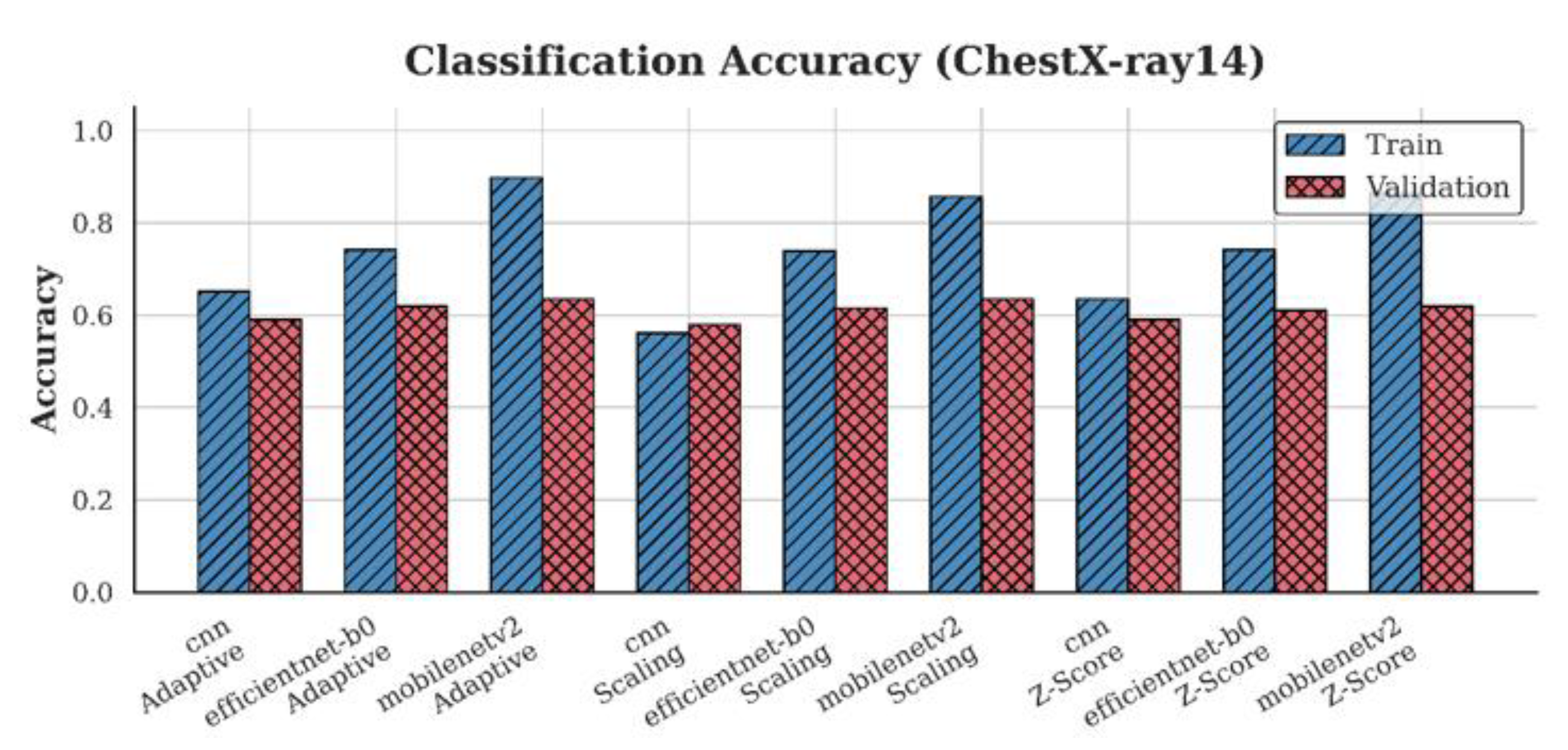

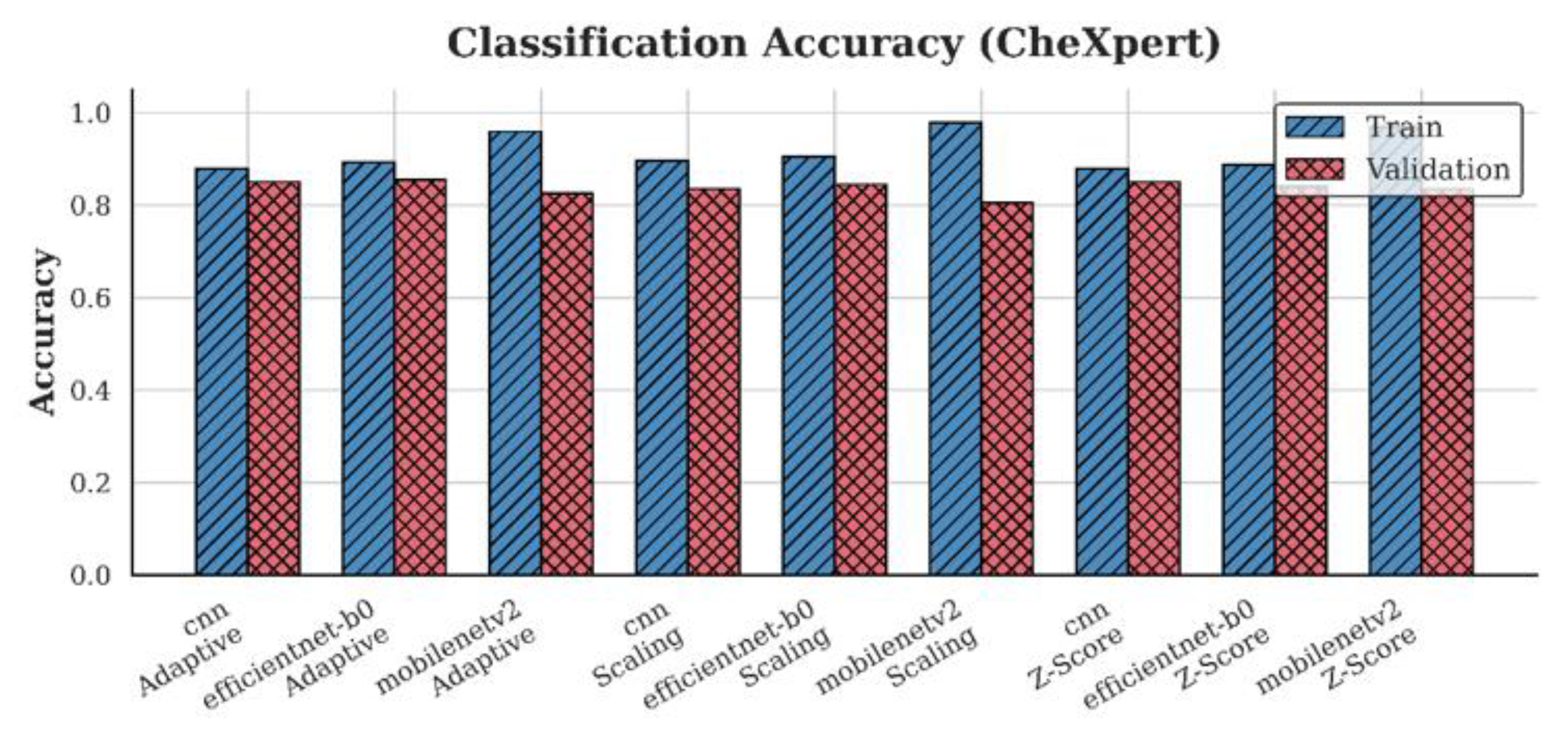

4.1. Accuracy Analysis

4.2. Loss Analysis

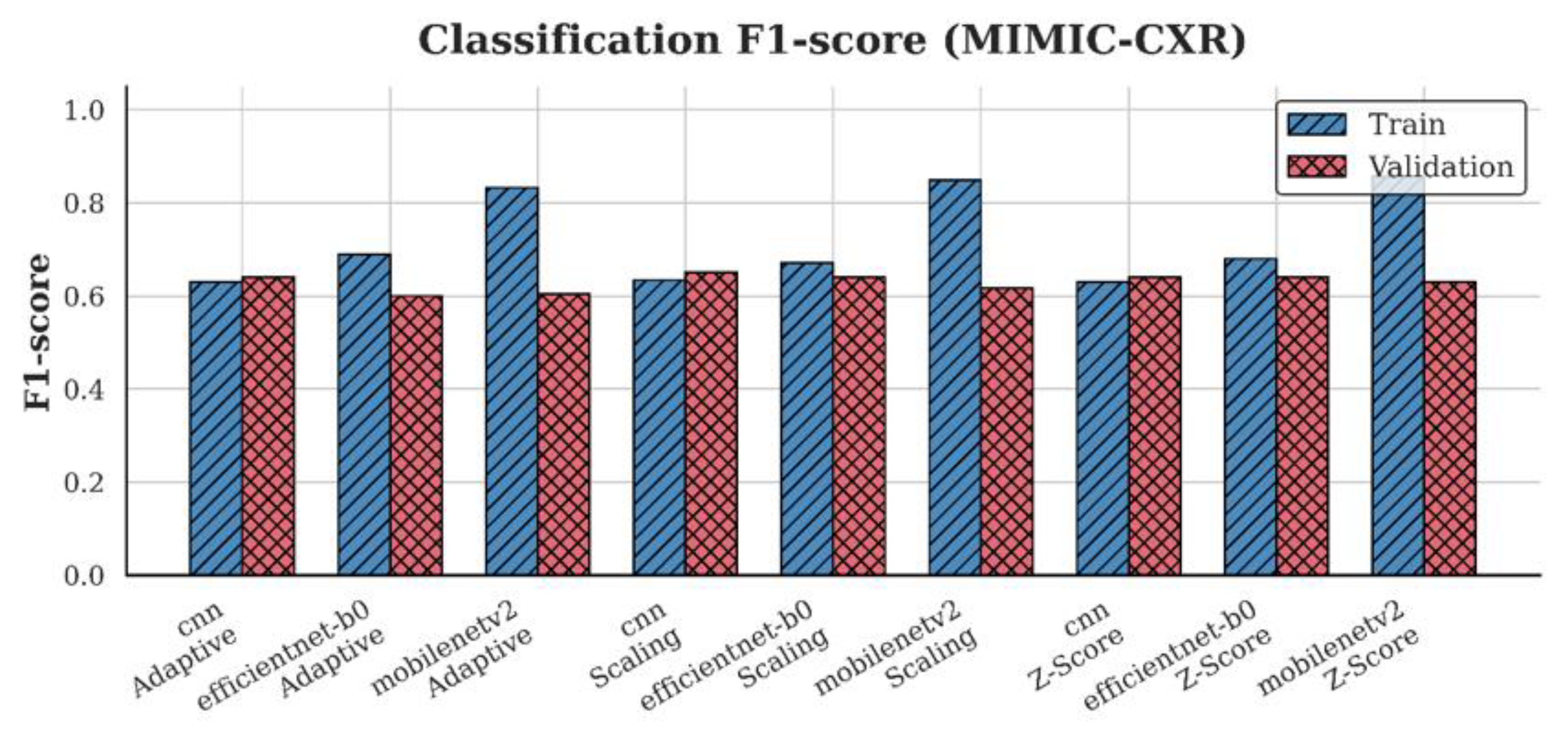

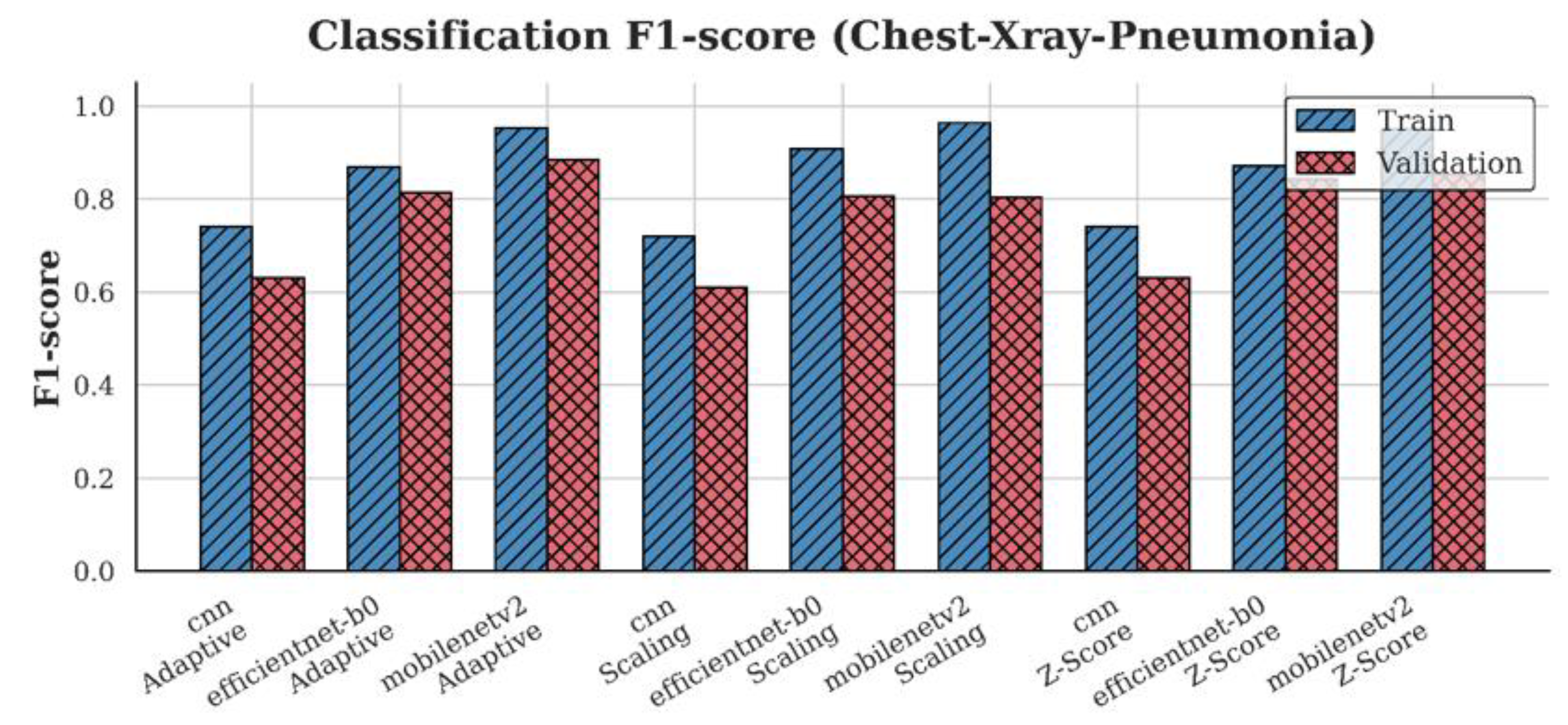

4.3. F1-Score Analysis

4.4. Synergistic Effects of Architecture and Normalization

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

Funding

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ethical approval

Declaration of Competing Interest

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

References

- Oh, Y.; Park, S.; Ye, J.C. Deep Learning COVID-19 Features on CXR Using Limited Training Data Sets. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2020, 39, 2688–2700. [CrossRef]

- Padmavathi, V.; Ganesan, K. Metaheuristic Optimizers Integrated with Vision Transformer Model for Severity Detection and Classification via Multimodal COVID-19 Images. Sci Rep 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, B.; Salman, O.K.M. Detection of COVID-19 Disease in Chest X-Ray Images with Capsul Networks: Application with Cloud Computing. Journal of Experimental & Theoretical Artificial Intelligence 2021, 33, 527–541. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Khan, S.H.; Saif, M.; Batool, A.; Sohail, A.; Waleed Khan, M. A Survey of Deep Learning Techniques for the Analysis of COVID-19 and Their Usability for Detecting Omicron. Journal of Experimental & Theoretical Artificial Intelligence 2024, 36, 1779–1821. [CrossRef]

- Attaullah, M.; Ali, M.; Almufareh, M.F.; Ahmad, M.; Hussain, L.; Jhanjhi, N.; Humayun, M. Initial Stage COVID-19 Detection System Based on Patients’ Symptoms and Chest X-Ray Images. Applied Artificial Intelligence 2022, 36, 2055398. [CrossRef]

- Marikkar, U.; Atito, S.; Awais, M.; Mahdi, A. LT-ViT: A Vision Transformer for Multi-Label Chest X-Ray Classification. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); 2023; pp. 2565–2569.

- Rajpurkar, P.; Irvin, J.; Zhu, K.; Yang, B.; Mehta, H.; Duan, T.; Ding, D.; Bagul, A.; Langlotz, C.; Shpanskaya, K.; et al. CheXNet: Radiologist-Level Pneumonia Detection on Chest X-Rays with Deep Learning. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2017. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Bai, H.; Sun, J.; Cheng, C.; Li, X. LPAdaIN: Light Progressive Attention Adaptive Instance Normalization Model for Style Transfer. Electronics 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Kim, T.; Park, J.; Raj, H.; Jabbar, M.S.; Abebaw, Z.D.; Lee, J.; Van, C.C.; Kim, H.; Shin, D. Pulmonary Abnormality Screening on Chest X-Rays from Different Machine Specifications: A Generalized AI-Based Image Manipulation Pipeline. Eur Radiol Exp 2023, 7. [CrossRef]

- Karaki, A.A.; Alrawashdeh, T.; Abusaleh, S.; Alksasbeh, M.Z.; Alqudah, B.; Alemerien, K.; Alshamaseen, H. Pulmonary Edema and Pleural Effusion Detection Using EfficientNet-V1-B4 Architecture and AdamW Optimizer from Chest X-Rays Images. Computers, Materials and Continua 2024, 80, 1055–1073. [CrossRef]

- Wangkhamhan, T. Adaptive Chaotic Satin Bowerbird Optimization Algorithm for Numerical Function Optimization. Journal of Experimental & Theoretical Artificial Intelligence 2021, 33, 719–746. [CrossRef]

- Demircioğlu, A. The Effect of Feature Normalization Methods in Radiomics. Insights Imaging 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Rayed, M.E.; Islam, S.M.S.; Niha, S.I.; Jim, J.R.; Kabir, M.M.; Mridha, M.F. Deep Learning for Medical Image Segmentation: State-of-the-Art Advancements and Challenges. Inform Med Unlocked 2024, 47. [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, S.; Devi, R.; Mat Isa, N.A. Optimized Exposer Region-Based Modified Adaptive Histogram Equalization Method for Contrast Enhancement in CXR Imaging. Sci Rep 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Tomar, D.; Lortkipanidze, M.; Vray, G.; Bozorgtabar, B.; Thiran, J.-P. Self-Attentive Spatial Adaptive Normalization for Cross-Modality Domain Adaptation. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2021, 40, 2926–2938. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Luo, X.; Gao, Z.; Wang, G. An Uncertainty-Guided Tiered Self-Training Framework for Active Source-Free Domain Adaptation in Prostate Segmentation. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2024, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.P.; Zhou, T.; Ji, G.P.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, G.; Fu, H.; Shen, J.; Shao, L. Inf-Net: Automatic COVID-19 Lung Infection Segmentation from CT Images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2020, 39, 2626–2637. [CrossRef]

- Irvin, J.; Rajpurkar, P.; Ko, M.; Yu, Y.; Ciurea-Ilcus, S.; Chute, C.; Marklund, H.; Haghgoo, B.; Ball, R.; Shpanskaya, K.; et al. CheXpert: A Large Chest Radiograph Dataset with Uncertainty Labels and Expert Comparison. AAAI’19/IAAI’19/EAAI’19: Proceedings of the Thirty-Third AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Thirty-First Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference and Ninth AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence 2019, 33, 590–597. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.E.W.; Pollard, T.J.; Berkowitz, S.J.; Greenbaum, N.R.; Lungren, M.P.; Deng, C. ying; Mark, R.G.; Horng, S. MIMIC-CXR, a de-Identified Publicly Available Database of Chest Radiographs with Free-Text Reports. Sci Data 2019, 6. [CrossRef]

- Gazda, M.; Plavka, J.; Gazda, J.; Drotar, P. Self-Supervised Deep Convolutional Neural Network for Chest X-Ray Classification. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 151972–151982. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Chowdhury, M.E.H.; Khandakar, A.; Islam, K.R.; Islam, K.F.; Mahbub, Z.B.; Kadir, M.A.; Kashem, S. Transfer Learning with Deep Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for Pneumonia Detection Using Chest X-Ray. Applied Sciences 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Kermany, D.S.; Goldbaum, M.; Cai, W.; Valentim, C.C.S.; Liang, H.; Baxter, S.L.; McKeown, A.; Yang, G.; Wu, X.; Yan, F.; et al. Identifying Medical Diagnoses and Treatable Diseases by Image-Based Deep Learning. Cell 2018, 172, 1122-1131.e9. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lin, Z.Q.; Wong, A. COVID-Net: A Tailored Deep Convolutional Neural Network Design for Detection of COVID-19 Cases from Chest X-Ray Images. Sci Rep 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Ait Nasser, A.; Akhloufi, M.A. A Review of Recent Advances in Deep Learning Models for Chest Disease Detection Using Radiography. Diagnostics 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, Ş.; Turalı, M.Y.; Çukur, T. HydraViT: Adaptive Multi-Branch Transformer for Multi-Label Disease Classification from Chest X-Ray Images. Biomed Signal Process Control 2023, 100, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Dede, A.; Nunoo-Mensah, H.; Tchao, E.T.; Agbemenu, A.S.; Adjei, P.E.; Acheampong, F.A.; Kponyo, J.J. Deep Learning for Efficient High-Resolution Image Processing: A Systematic Review. Intelligent Systems with Applications 2025, 26. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.S.; Li, N.; Wang, T.; Liu, X.; Dai, J.; Chan, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhu, J.; Kong, W.; Lu, Z.; et al. COVID-19 Detection via Ultra-Low-Dose X-Ray Images Enabled by Deep Learning. Bioengineering 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Oltu, B.; Güney, S.; Yuksel, S.E.; Dengiz, B. Automated Classification of Chest X-Rays: A Deep Learning Approach with Attention Mechanisms. BMC Med Imaging 2025, 25. [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.M.; Rehmani, M.H.; O’Reilly, R. Addressing the Intra-Class Mode Collapse Problem Using Adaptive Input Image Normalization in GAN-Based X-Ray Images. In Proceedings of the 2022 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC); 2022; pp. 2049–2052.

- Reinhold, J.C.; Dewey, B.E.; Carass, A.; Prince, J.L. Evaluating the Impact of Intensity Normalization on MR Image Synthesis. Proc SPIE Int Soc Opt Eng 2018, 10949. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Belongie, S. Arbitrary Style Transfer in Real-Time with Adaptive Instance Normalization. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017; pp. 1510–1519.

- R, V.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, A.; Ashok Kumar, V.D.; K, R.; Kumar, V.D.A.; Jilani Saudagar, A.K.; A, A. COVIDPRO-NET: A Prognostic Tool to Detect COVID 19 Patients from Lung X-Ray and CT Images Using Transfer Learning and Q-Deformed Entropy. Journal of Experimental & Theoretical Artificial Intelligence 2023, 35, 473–488. [CrossRef]

- Albert, S.; Wichtmann, B.D.; Zhao, W.; Maurer, A.; Hesser, J.; Attenberger, U.I.; Schad, L.R.; Zöllner, F.G. Comparison of Image Normalization Methods for Multi-Site Deep Learning. Applied Sciences 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Al-Waisy, A.S.; Mohammed, M.A.; Al-Fahdawi, S.; Maashi, M.S.; Garcia-Zapirain, B.; Abdulkareem, K.H.; Mostafa, S.A.; Kumar, N.M.; Le, D.N. COVID-DeepNet: Hybrid Multimodal Deep Learning System for Improving COVID-19 Pneumonia Detection in Chest X-Ray Images. Computers, Materials and Continua 2021, 67, 2409–2429. [CrossRef]

- Nuruddin Bin Azhar, A.; Sani, N.S.; Luan, L.; Wei, X. Enhancing COVID-19 Detection in X-Ray Images Through Deep Learning Models with Different Image Preprocessing Techniques. IJACSA) International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2025, 16, 633–644. [CrossRef]

- Toğaçar, M.; Ergen, B.; Cömert, Z. COVID-19 Detection Using Deep Learning Models to Exploit Social Mimic Optimization and Structured Chest X-Ray Images Using Fuzzy Color and Stacking Approaches. Comput Biol Med 2020, 121. [CrossRef]

- Sanida, T.; Dasygenis, M. A Novel Lightweight CNN for Chest X-Ray-Based Lung Disease Identification on Heterogeneous Embedded System. Applied Intelligence 2024, 54, 4756–4780. [CrossRef]

- Sriwiboon, N. Efficient and Lightweight CNN Model for COVID-19 Diagnosis from CT and X-Ray Images Using Customized Pruning and Quantization Techniques. Neural Comput Appl 2025, 37, 13059–13078. [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Jurman, G. The Advantages of the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) over F1 Score and Accuracy in Binary Classification Evaluation. BMC Genomics 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Bani Baker, Q.; Hammad, M.; Al-Smadi, M.; Al-Jarrah, H.; Al-Hamouri, R.; Al-Zboon, S.A. Enhanced COVID-19 Detection from X-Ray Images with Convolutional Neural Network and Transfer Learning. J Imaging 2024, 10. [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulos, I.D.; Mpesiana, T.A. Covid-19: Automatic Detection from X-Ray Images Utilizing Transfer Learning with Convolutional Neural Networks. Phys Eng Sci Med 2020, 43, 635–640. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, N.K.; Rahman, Md.M.; Kabir, M.A. PDCOVIDNet: A Parallel-Dilated Convolutional Neural Network Architecture for Detecting COVID-19 from Chest X-Ray Images. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, Ş.; Turalı, M.Y.; Çukur, T. HydraViT: Adaptive Multi-Branch Transformer for Multi-Label Disease Classification from Chest X-Ray Images. 2023.

- Wang, L.; Lin, Z.Q.; Wong, A. COVID-Net: A Tailored Deep Convolutional Neural Network Design for Detection of COVID-19 Cases from Chest X-Ray Images. Sci Rep 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Rajpurkar, P.; Irvin, J.; Ball, R.L.; Zhu, K.; Yang, B.; Mehta, H.; Duan, T.; Ding, D.; Bagul, A.; Langlotz, C.P.; et al. Deep Learning for Chest Radiograph Diagnosis: A Retrospective Comparison of the CheXNeXt Algorithm to Practicing Radiologists. PLoS Med 2018, 15, e1002686. [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. V EfficientNetV2: Smaller Models and Faster Training; 2021.

- Çallı, E.; Sogancioglu, E.; van Ginneken, B.; van Leeuwen, K.G.; Murphy, K. Deep Learning for Chest X-Ray Analysis: A Survey. Med Image Anal 2021, 72, 102125. [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Lin, R.; Du, W.; Tavares, A.; Liang, Y. Explainable Hybrid Transformer for Multi-Classification of Lung Disease Using Chest X-Rays. Sci Rep 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Bani Baker, Q.; Hammad, M.; Al-Smadi, M.; Al-Jarrah, H.; Al-Hamouri, R.; Al-Zboon, S.A. Enhanced COVID-19 Detection from X-Ray Images with Convolutional Neural Network and Transfer Learning. J Imaging 2024, 10. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Li, X.; Li, M.; Zuo, W.; Shan, S. Shift-Net: Image Inpainting via Deep Feature Rearrangement. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision – ECCV 2018; Ferrari, V., Hebert, M., Sminchisescu, C., Weiss, Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 3–19.

- Gazda, M.; Plavka, J.; Gazda, J.; Drotar, P. Self-Supervised Deep Convolutional Neural Network for Chest X-Ray Classification. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 151972–151982. [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, M.; Terhljan, N.; Chung, A.G.; Zhao, A.; Surana, S.; Aboutalebi, H.; Gunraj, H.; Sabri, A.; Alaref, A.; Wong, A. COVID-Net CXR-2: An Enhanced Deep Convolutional Neural Network Design for Detection of COVID-19 Cases From Chest X-Ray Images. Front Med 2022, 9. [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Kim, T.; Park, J.; Raj, H.; Jabbar, M.S.; Abebaw, Z.D.; Lee, J.; Van, C.C.; Kim, H.; Shin, D. Pulmonary Abnormality Screening on Chest X-Rays from Different Machine Specifications: A Generalized AI-Based Image Manipulation Pipeline. Eur Radiol Exp 2023, 7. [CrossRef]

- Gunraj, H.; Wang, L.; Wong, A. COVIDNet-CT: A Tailored Deep Convolutional Neural Network Design for Detection of COVID-19 Cases From Chest CT Images. Front Med 2020, 7. [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.P.; Zhou, T.; Ji, G.P.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, G.; Fu, H.; Shen, J.; Shao, L. Inf-Net: Automatic COVID-19 Lung Infection Segmentation from CT Images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2020, 39, 2626–2637. [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.; Park, S.; Ye, J.C. Deep Learning COVID-19 Features on CXR Using Limited Training Data Sets. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2020, 39, 2688–2700. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Chowdhury, M.E.H.; Khandakar, A.; Islam, K.R.; Islam, K.F.; Mahbub, Z.B.; Kadir, M.A.; Kashem, S. Transfer Learning with Deep Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for Pneumonia Detection Using Chest X-Ray. Applied Sciences 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Gunraj, H.; Wang, L.; Wong, A. COVIDNet-CT: A Tailored Deep Convolutional Neural Network Design for Detection of COVID-19 Cases From Chest CT Images. Front Med 2020, 7. [CrossRef]

- Toğaçar, M.; Ergen, B.; Cömert, Z. COVID-19 Detection Using Deep Learning Models to Exploit Social Mimic Optimization and Structured Chest X-Ray Images Using Fuzzy Color and Stacking Approaches. Comput Biol Med 2020, 121. [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, T.; Talo, M.; Yildirim, E.A.; Baloglu, U.B.; Yildirim, O.; Rajendra Acharya, U. Automated Detection of COVID-19 Cases Using Deep Neural Networks with X-Ray Images. Comput Biol Med 2020, 121, 103792. [CrossRef]

- Al-Waisy, A.S.; Mohammed, M.A.; Al-Fahdawi, S.; Maashi, M.S.; Garcia-Zapirain, B.; Abdulkareem, K.H.; Mostafa, S.A.; Kumar, N.M.; Le, D.N. COVID-DeepNet: Hybrid Multimodal Deep Learning System for Improving COVID-19 Pneumonia Detection in Chest X-Ray Images. Computers, Materials and Continua 2021, 67, 2409–2429. [CrossRef]

- Vinod, D.N.; Jeyavadhanam, B.R.; Zungeru, A.M.; Prabaharan, S.R.S. Fully Automated Unified Prognosis of Covid-19 Chest X-Ray/CT Scan Images Using Deep Covix-Net Model. Comput Biol Med 2021, 136. [CrossRef]

- Marikkar, U.; Atito, S.; Awais, M.; Mahdi, A. LT-ViT: A Vision Transformer for Multi-Label Chest X-Ray Classification. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Karaki, A.A.; Alrawashdeh, T.; Abusaleh, S.; Alksasbeh, M.Z.; Alqudah, B.; Alemerien, K.; Alshamaseen, H. Pulmonary Edema and Pleural Effusion Detection Using EfficientNet-V1-B4 Architecture and AdamW Optimizer from Chest X-Rays Images. Computers, Materials and Continua 2024, 80, 1055–1073. [CrossRef]

- Sanida, T.; Dasygenis, M. A Novel Lightweight CNN for Chest X-Ray-Based Lung Disease Identification on Heterogeneous Embedded System. Applied Intelligence 2024, 54, 4756–4780. [CrossRef]

- Yen, C.T.; Tsao, C.Y. Lightweight Convolutional Neural Network for Chest X-Ray Images Classification. Sci Rep 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Hage Chehade, A.; Abdallah, N.; Marion, J.M.; Hatt, M.; Oueidat, M.; Chauvet, P. Reconstruction-Based Approach for Chest X-Ray Image Segmentation and Enhanced Multi-Label Chest Disease Classification. Artif Intell Med 2025, 165. [CrossRef]

- Padmavathi, V.; Ganesan, K. Metaheuristic Optimizers Integrated with Vision Transformer Model for Severity Detection and Classification via Multimodal COVID-19 Images. Sci Rep 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Shati, A.; Hassan, G.M.; Datta, A. A Comprehensive Fusion Model for Improved Pneumonia Prediction Based on KNN-Wavelet-GLCM and a Residual Network. Intelligent Systems with Applications 2025, 26. [CrossRef]

- Sriwiboon, N. Efficient and Lightweight CNN Model for COVID-19 Diagnosis from CT and X-Ray Images Using Customized Pruning and Quantization Techniques. Neural Comput Appl 2025. [CrossRef]

- Albert, S.; Wichtmann, B.D.; Zhao, W.; Maurer, A.; Hesser, J.; Attenberger, U.I.; Schad, L.R.; Zöllner, F.G. Comparison of Image Normalization Methods for Multi-Site Deep Learning. Applied Sciences 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Demircioğlu, A. The Effect of Feature Normalization Methods in Radiomics. Insights Imaging 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.; Park, S.; Ye, J.C. Deep Learning COVID-19 Features on CXR Using Limited Training Data Sets. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2020, 39, 2688–2700. [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Jurman, G. The Advantages of the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) over F1 Score and Accuracy in Binary Classification Evaluation. BMC Genomics 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Demšar, J. Statistical Comparisons of Classifiers over Multiple Data Sets; 2006; Vol. 7.

- Reinhold, J.C.; Dewey, B.E.; Carass, A.; Prince, J.L. Evaluating the Impact of Intensity Normalization on MR Image Synthesis. 2018.

- Banik, P.; Majumder, R.; Mandal, A.; Dey, S.; Mandal, M. A Computational Study to Assess the Polymorphic Landscape of Matrix Metalloproteinase 3 Promoter and Its Effects on Transcriptional Activity. Comput Biol Med 2022, 145, 105404. [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.M.; Rehmani, M.H.; O’reilly, R. Addressing the Intra-Class Mode Collapse Problem Using Adaptive Input Image Normalization in GAN-Based X-Ray Images. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, EMBS; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2022; Vol. 2022-July, pp. 2049–2052.

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. Mach Learn 2020. [CrossRef]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.-C. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018; pp. 4510–4520.

- Bougourzi, F.; Dornaika, F.; Distante, C.; Taleb-Ahmed, A. D-TrAttUnet: Toward Hybrid CNN-Transformer Architecture for Generic and Subtle Segmentation in Medical Images. Comput Biol Med 2024, 176, 108590. [CrossRef]

- Irvin, J.; Rajpurkar, P.; Ko, M.; Yu, Y.; Ciurea-Ilcus, S.; Chute, C.; Marklund, H.; Haghgoo, B.; Ball, R.; Shpanskaya, K.; et al. CheXpert: A Large Chest Radiograph Dataset with Uncertainty Labels and Expert Comparison.

- Johnson, A.E.W.; Pollard, T.J.; Berkowitz, S.J.; Greenbaum, N.R.; Lungren, M.P.; Deng, C. ying; Mark, R.G.; Horng, S. MIMIC-CXR, a de-Identified Publicly Available Database of Chest Radiographs with Free-Text Reports. Sci Data 2019, 6. [CrossRef]

- Kermany, D.S.; Goldbaum, M.; Cai, W.; Valentim, C.C.S.; Liang, H.; Baxter, S.L.; McKeown, A.; Yang, G.; Wu, X.; Yan, F.; et al. Identifying Medical Diagnoses and Treatable Diseases by Image-Based Deep Learning. Cell 2018, 172, 1122-1131.e9. [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. 2019.

- Litjens, G.; Kooi, T.; Bejnordi, B.E.; Setio, A.A.A.; Ciompi, F.; Ghafoorian, M.; van der Laak, J.A.W.M.; van Ginneken, B.; Sánchez, C.I. A Survey on Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis. Med Image Anal 2017, 42, 60–88. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Sodha, V.; Pang, J.; Gotway, M.B.; Liang, J. Models Genesis. Med Image Anal 2021, 67, 101840. [CrossRef]

- Rayed, Md.E.; Islam, S.M.S.; Niha, S.I.; Jim, J.R.; Kabir, M.M.; Mridha, M.F. Deep Learning for Medical Image Segmentation: State-of-the-Art Advancements and Challenges. Inform Med Unlocked 2024, 47, 101504. [CrossRef]

| Authors | Model Architecture |

Technique/ Approach |

Dataset | Performance Metrics |

Key Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [55] | Inf-Net (Res2Net-based) | Semi-supervised segmentation with reverse & edge attention | COVID-SemiSeg | Dice Coefficient, Sensitivity, Specificity | First semi-supervised deep model for COVID-19 CT lung infection segmentation; released annotated dataset |

| [56] | Patch-based ResNet-18 + CAM | Semi-supervised learning using limited labeled data and CAM-based localization | COVIDx, RSNA Pneumonia | Accuracy, AUC, Sensitivity, Specificity | Achieved high performance with few COVID-19 CXR using semi-supervised and attention-based localization |

| [57] | CNN variants (VGG19, DenseNet121, InceptionV3) | Transfer learning with fine-tuning and augmentation | ChestX-ray Pneumonia | Accuracy, F1-score | Compared to several CNNs; VGG19 achieved highest accuracy; emphasized effect of augmentation |

| [58] | COVIDNet-CT | Tailored CNN for CT-based COVID detection | COVIDx-CT | Accuracy, Sensitivity | High-accuracy detection in CT scans |

| [59] | MobileNetV2, SqueezeNet (stacked) | Fuzzy color preprocessing + Social Mimic Optimization + stacking ensemble | COVID-19 dataset (Cohen), ChestX-ray | Accuracy, Sensitivity, Specificity, F1-score | Combined CNN with fuzzy imaging and metaheuristics; high performance with small and imbalanced datasets |

| [44] | COVID-Net | Machine-driven CNN for multi-class COVID-19 detection | COVIDx | Accuracy, Sensitivity (COVID) | Designed COVID-specific CNN and released COVIDx dataset with focus on transparency and explainability |

| [60] | DarkCovidNet (modified DarkNet-19) | CNN for binary & multi-class COVID-19 detection from X-ray | COVID-19 X-ray (collected) | Accuracy, F1-score, Specificity | Proposed DarkCovidNet; evaluated both binary and multi-class classification; high performance with limited dataset |

| [61] | InceptionResNetV2 + BiLSTM | Hybrid fusion of deep CNN features and handcrafted features (GLCM, LBP) | COVIDx, Kaggle CXR COVID, BIMCV COVID-19+ | Accuracy, AUC, F1-score | Hybrid multimodal model outperformed CNN-only baselines; high accuracy with feature fusion strategy |

| [62] | Deep Covix-Net (CNN-based) | Hybrid deep CNN with wavelet & FFT; ensemble with Random Forest | Kaggle & GitHub (CXR + CT images) | Accuracy, Confusion Matrix, AUC | Unified model for CXR & CT COVID-19 detection; high accuracy with hybrid processing pipeline |

| [63] | LT-ViT (Label Token Vision Transformer) | Multi-scale attention between label tokens and image patches | CheXpert, ChestX-ray14 | AUC, Interpretability | Outperformed ViT baselines; interpretable without Grad-CAM; multi-label optimized via label-token fusion |

| Authors |

Model Architecture |

Technique/ Approach |

Dataset | Performance Metrics | Key Highlights |

| [53] | ResNet-based CNN | Preprocessing with style and histogram normalization for cross-device generalization | Multi-hospital Chest X-rays (7 hospitals, Korea) | Accuracy, AUC, Sensitivity | Proposed generalized preprocessing pipeline; improved CXR classification across varied X-ray machines |

| [64] | EfficientNet-V1-B4 | CLAHE, data augmentation, AdamW optimizer | ChestX-ray14, PadChest, CheXpert (28,309 images) | Accuracy, Recall, Precision, F1-score, AUC | Robust multi-class classification of edema and effusion with near-perfect AUC. |

| [65] | Lightweight CNN (custom) | Lung disease classification optimized for embedded systems | ChestX-ray14, COVID-19 Radiography DB | Accuracy, Sensitivity, Specificity | Efficient CNN for embedded deployment; real-time lung disease detection on low-power devices |

| [66] | Lightweight CNN (custom) | Efficient chest X-ray classification for low-resource devices | ChestX-ray14 (NIH) | Accuracy, Precision, Sensitivity, Specificity | Proposed ultra-light CNN with near-ResNet50 performance; optimized for edge deployment |

| [67] | CycleGAN + XGBoost/Random Forest | CycleGAN-based segmentation, radiomic feature extraction, novel feature selection | ChestX-ray14 | AUC, Accuracy | Introduction of pathology-aware segmentation with CycleGAN; achieved 83.12% AUC in multi-label classification |

| [48] | EHTNet (Hybrid CNN-Transformer) | Explainable hybrid model for lung disease multi-classification | ChestX-ray14, COVID-19 Radiography DB | Accuracy, AUC, Sensitivity | Introduced EHTNet with attention-based explainability; outperformed CNN & ViT baselines |

| [68] | Vision Transformer + Metaheuristics | Severity detection and COVID classification via multimodal learning | Chest X-ray, Chest CT (COVID-19) | Accuracy, Sensitivity, Specificity | Applied PSO/GWO to fine-tune ViT; supports multimodal inputs; high precision in severity ranking |

| [69] | ResNet50 + KNN-Wavelet-GLCM | Deep–shallow fusion using texture features and CNN with soft voting | RSNA, Kermany pneumonia datasets | Accuracy, AUC | Hybrid model combining CNN and handcrafted features; high precision on both adult and pediatric datasets |

| [70] | Lightweight CNN (customized) | Pruning + post-training quantization for edge-device deployment | COVIDx (CXR), COVID-CT (CT) | Accuracy, F1-score, Inference time | Designed ultra-efficient CNN for COVID-19 diagnosis with <2MB size and real-time speed on embedded systems |

| This Study | CNN, EfficientNet, MobileNetV2 | Adaptive normalization strategies | ChestX-ray14,CheXpert,MIMIC-CXR,Chest-Xray-Pneumonia | Accuracy, F1 | Systematic evaluation of normalization across datasets and models |

| Dataset | Image Count | Sampling | Patients | Number of Classes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChestX-ray14 | 112,120 | 16,000 | 30,805 | 14 |

| CheXpert | 224,316 | 16,000 | 65,240 | 14 |

| MIMIC-CXR | 377,110 | 16,000 | 227,827 | 14 |

| Chest-Xray-Pneumonia | 5,863 | 5,863 | Pediatric only | 3 |

| Comparison | p-value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Adaptive vs. Z-score | 0.0078 | Significant () |

| Adaptive vs. Scaling | 0.0039 | Significant () |

| Z-score vs. Scaling | 0.0781 | Not Significant () |

| Dataset | Deep learning | Scaling | Z-score | Adaptive |

| ChestX-ray14 | CNN | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.59 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.62 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.64 | |

| CheXpert | CNN | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.86 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.83 | |

| MIMIC-CXR | CNN | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.64 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.60 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.60 | |

| Chest-Xray-Pneumonia | CNN | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.63 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.82 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.82 | 0.88 | 0.91 |

| Dataset | Preprocessing | Scaling | Z-score | Adaptive |

| ChestX-ray14 | CNN | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.69 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.66 | 0.67 | 0.68 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.66 | 0.73 | 0.71 | |

| CheXpert | CNN | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.46 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.44 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.37 | |

| MIMIC-CXR | CNN | 0.66 | 0.65 | 0.65 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.70 | 0.66 | 0.68 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.74 | |

| Chest-Xray-Pneumonia | CNN | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.36 | 0.40 | 0.40 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.29 |

| Dataset | Preprocessing | Scaling | Z-score | Adaptive |

| ChestX-ray14 | CNN | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.59 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.62 | 0.60 | 0.60 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.62 | |

| CheXpert | CNN | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.82 | |

| MIMIC-CXR | CNN | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.64 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.60 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.60 | |

| Chest-Xray-Pneumonia | CNN | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.63 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.81 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).