1. Introduction

In recent years, with the rapid growth of medical data, how to efficiently utilize this data to support personalized health decisions has become an important research direction. Medical data typically has high dimensionality, time series characteristics, and complex noise, making traditional prediction methods inadequate for handling such data. Therefore, emerging methods based on deep learning, such as LSTM models, are gradually receiving attention and application from researchers. By constructing an efficient medical data prediction model, not only can the accuracy of disease prediction be improved and the misdiagnosis rate be reduced, but more personalized health management plans can also be provided for patients, thereby optimizing the allocation of medical resources and improving the overall quality of medical services.

The main contribution of this article is to propose an efficient prediction model based on LSTM to address the shortcomings of traditional medical data prediction methods. Firstly, the article conducts detailed data preprocessing, including data cleaning, missing value filling, and standardization processing, to ensure the quality and consistency of the data. Secondly, the article combines domain knowledge and correlation analysis to screen and construct key features, ensuring that the model can capture information closely related to the target variable. Finally, utilizing the time series modeling capability of the LSTM model, predictive training was conducted on medical data, and progress was made.

The organizational structure of this article is as follows: Firstly, the first part introduces the research background, related field work, and the significance of this study; the second part provides a detailed description of methods for data preprocessing, feature selection, and model design; the third part presents the experimental results of the model and compares and analyzes it with other models; finally, the fourth section summarizes the research findings of this article.

2. Related Works

In recent years, many researchers have attempted to use various machine learning algorithms to improve the prediction accuracy of medical data. For example, Aldahiri et al. highlighted several well-known machine learning algorithms for classification and prediction, and demonstrated their applications in the healthcare field. In addition, they provided a comprehensive overview of current machine learning methods and their applications in IoT medical data [

1]. Harimoorthy and Thangavelu proposed a universal architecture that utilizes medical data and machine learning techniques to analyze large amounts of data, identify hidden patterns in diseases, and provide personalized treatment and disease prediction for patients [

2]. Deep learning has the potential to change medical diagnosis, but its diagnostic accuracy is still uncertain. Aggarwal et al.’s study aimed to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of deep learning algorithms in identifying pathology in medical imaging [

3]. Song and Montenegro Marin discussed the training and accuracy of complex algorithms for extracting and studying key sports medicine data, as well as their shortcomings [

4]. Medical data is widely distributed in hospitals and personal lives, spanning different institutions and regions, and has important diagnostic and therapeutic value. However, the leakage of patient information has caused panic, making medical data security crucial for smart healthcare. Liu et al. aimed to develop a medical data security scheme based on a multi-objective convolutional interval type-2 fuzzy rough model using an improved multi-objective evolutionary algorithm [

5]. Mehmood et al. proposed a method called CardioHelp, which combines convolutional neural networks to obtain the probability of patients suffering from cardiovascular disease [

6]. Early prediction and diagnosis of sepsis are crucial for reducing mortality rates, but its symptoms are similar to other milder diseases, making diagnosis challenging. Goh et al. developed an artificial intelligence algorithm that utilizes structured data and unstructured clinical records to predict and diagnose sepsis [

7]. In order to forecast coronary heart disease, Ayon et al. analyzed many computational intelligence technologies. Their study findings were then compared with the most recent heart disease prediction methodologies, demonstrating their superiority over earlier studies [

8]. Overall, there are still issues with insufficient high-dimensional data processing capabilities and poor generalization in medical data prediction in other studies.

Some studies have shown that intelligent algorithms have great potential in addressing the complexity and diversity of medical data. For example, Manickam et al. explored the role of artificial intelligence in supporting the development of robotic surgeries for advanced biomedical applications [

9]. In parallel, Zhang et al. proposed a knowledge distillation framework utilizing the lightweight DeepSeek-R1 model for anti-money laundering transaction detection, which demonstrated that compact models can still maintain high interpretability and effectiveness in complex data environments similar to healthcare settings [

15]. Their success inspires new possibilities for applying knowledge distillation to medical data modeling.

In the healthcare field, the development and deployment of unfair artificial intelligence systems may affect the provision of fair care. Chen et al. outlined the fairness of machine learning from a healthcare perspective and discussed how algorithm bias arises in clinical workflows and the resulting medical disparities [

10]. However, these methods still have shortcomings when facing different types of data fusion and feature selection. Therefore, this article proposes to adopt an intelligent algorithm based on the combination of ensemble learning and deep learning, aiming to overcome the above shortcomings and improve the accuracy and stability of medical data prediction. Wang et al. demonstrated in the financial field that real-time credit risk detection can benefit from AI frameworks with dynamic response to high-frequency time-series data, a finding that echoes the needs of medical prediction tasks with similar temporal complexity [

16].

3. Methods

3.1. Data Preprocessing

3.1.1. Data Cleaning

Data cleansing is the first step in preprocessing and primarily uses medical data from MIMIC-III/MIMIC-IV, HCUP, and NHANES. These data often contain missing values, duplicates, and outliers that may originate from different measurement devices or recording errors. In this paper, the following strategy is used for data cleaning:

Duplicate value processing: possible duplicate records are detected and removed from these databases to prevent negative impact on model training.

Outlier detection: an IQR (Interquartile Range) based approach is used to remove outliers from the SEER databases and CMS public use files that may interfere with model predictions. For example, in important health indicators such as blood pressure and heart rate, extreme and unreasonable measurements are removed to ensure the reasonableness of the data.

Missing value processing: for missing values, this paper used linear interpolation and K-nearest neighbor algorithm for missing values in different databases, such as MIMIC-IV and HCUP, in order to maintain the integrity and consistency of the data [

11].

3.1.2. Data Standardization

Due to significant differences in the range and magnitude of data for different health indicators, such as blood pressure and blood glucose values, directly inputting these data into the model may result in certain features having too much or too little impact on the prediction results. To avoid this situation, this article uses the Z-score method to normalize the numerical values of all input features. The specific method is to subtract the mean from the value of each feature, and then divide by the standard deviation, so that the processed data has zero mean and unit standard deviation.

3.1.3. Dataset Partitioning

After preprocessing, this article divides the dataset into training set, validation set, and testing set to ensure the model’s generalization ability.

Table 1 shows the situation of some health indicators before and after preprocessing.

Owing to the robust modeling capabilities of the LSTM model utilized in this article for time series data, before importing the model, the data must be transformed into a format appropriate for time series. The specific approach is to associate the patient data of each time step with the data of several previous time steps, and construct a multi-step input sequence suitable for LSTM processing. In this study, each input sequence is set to contain 5 time steps, each time step containing all health indicator features. Through the above data preprocessing steps, this article ensures the integrity, consistency, and applicability of medical data, providing a reliable data foundation for subsequent model training and evaluation.

3.2. Key Feature Selection and Construction

3.2.1. Preliminary Screening Based on Domain Knowledge

Firstly, based on expert knowledge in the medical field, a set of core features that may have a significant impact on the patient’s health status was selected. For example, vital signs such as blood pressure, heart rate, blood glucose, and body temperature of patients are commonly used key indicators in clinical diagnosis and treatment, while relatively static features such as height and weight, although indirectly affecting certain health problems, have insufficient dynamism and low predictive value. Therefore, in the preliminary screening, this article prioritizes retaining vital sign data highly correlated with patient physiological changes, and excludes features with small variability or limited contribution to prediction.

3.2.2. Correlation Analysis

In order to further quantify the correlation between each feature and the target variable, this article uses Pearson correlation coefficient for analysis, as shown in Formula (1):

In Formula (1), and represent the eigenvalues and target values, and represent their means, and the closer the absolute value of is to 1, the stronger the correlation between the features and the target variable. For features with low correlation, this article performed a removal process to reduce the interference of noise and redundant information on the model. Through correlation analysis, features highly correlated with the target variable are retained, which helps improve the prediction accuracy and efficiency of the model.

3.2.3. Multicollinearity Detection

In high-dimensional medical data, there may be strong collinearity between certain features, meaning there is a high degree of linear correlation between multiple features. Multicollinearity not only increases the complexity of the model, but may also lead to unstable parameter estimation and reduce the predictive performance of the model. To address this issue, this article detects collinearity features by calculating the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). Usually, when the VIF value exceeds 10, it indicates strong collinearity between the feature and other features.

3.2.4. Feature Construction

In order to enhance the predictive ability of the model, this article also constructed and extended the original features. Feature construction mainly includes time series feature construction and derived feature generation. For instance, Miao et al. proposed a multimodal RAG framework that jointly optimizes visual encodings and policy vector retrieval, highlighting the importance of collaborative optimization in constructing robust, interpretable features from high-dimensional heterogeneous inputs—a strategy that can be similarly beneficial in multimodal medical datasets [

18]. In terms of time series feature construction, this article segmented the health data of each patient to ensure that the model can not only use the current health data, but also utilize data from previous time points to capture the historical changes in patient signs.

3.3. Model Architecture Design

3.3.1. Basic Structure of LSTM

The structure of LSTM mainly consists of cell states and gating mechanisms, which control the flow of information through input gates, forget gates, and output gates, effectively preserving important long-term dependent information while suppressing irrelevant short-term noise. This structure is different from traditional RNN(Recurrent Neural Networks) in that it can avoid gradient vanishing or exploding problems caused by long time series, ensuring that the model has stable learning ability when dealing with long time series [

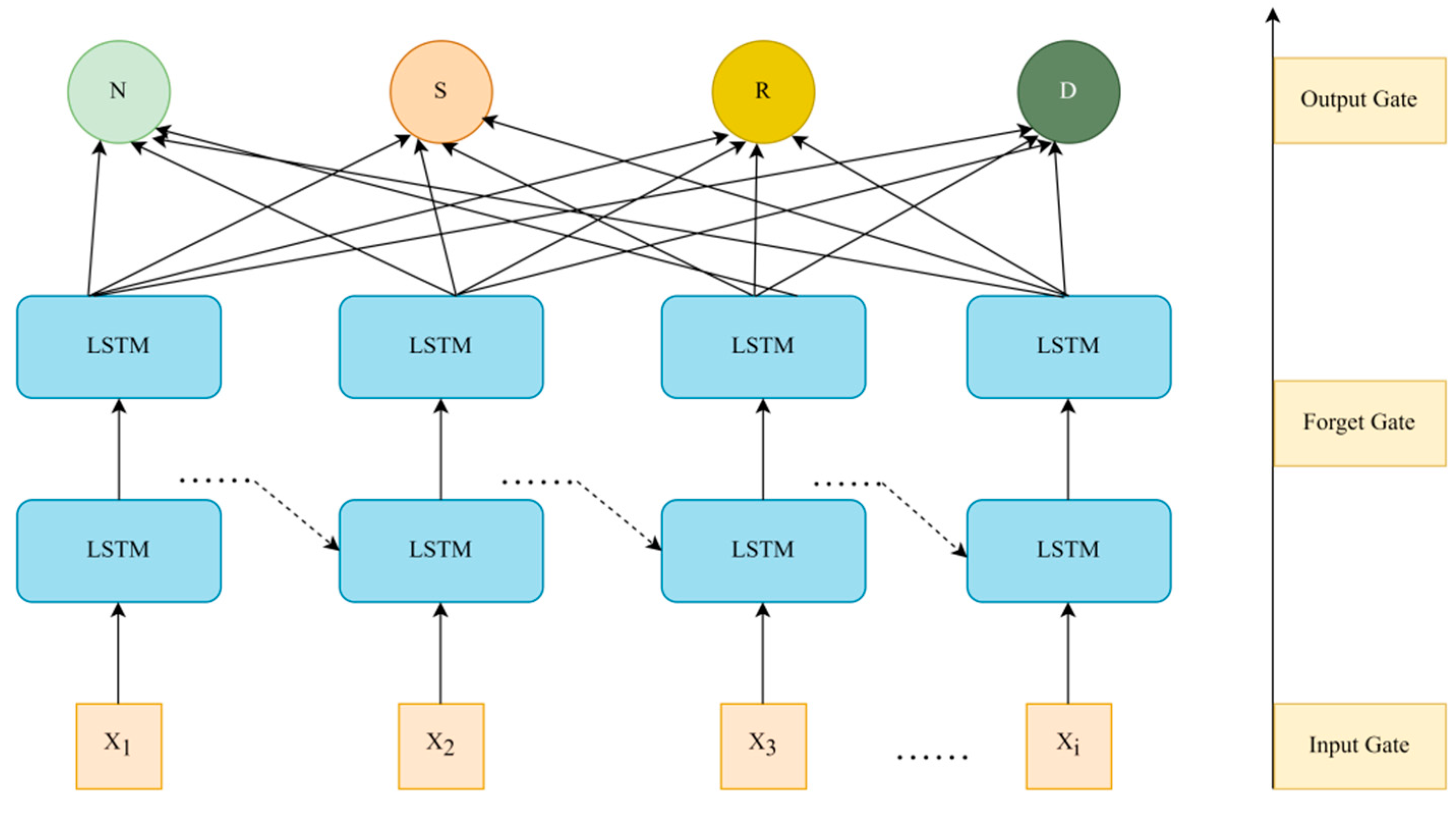

12]. The structure diagram of the LSTM model can be seen in

Figure 1:

In

Figure 1, the forget gate determines the historical information that needs to be discarded or retained, helping the model filter important temporal dependencies, as shown in Formula (2):

In Formula (2),

represents the output of the forget gate,

represents the weight matrix,

represents the hidden state of the previous time step,

is the current input,

is the bias term of the forget gate, and

represents the activation function. The input gate is used to control the proportion of current input information entering the cell state, as shown in Formulas (3) and (4):

Among them, represents the output of the input gate, and represents the update of candidate memory units. The output gate determines the output part of the cell state, ensuring that the model can effectively transmit information between time steps.

3.3.2. Input and Output Design of the Model

In practical applications, the medical data processed in this article involves continuous health indicators of multiple patients (such as blood pressure, heart rate, blood glucose, etc.), which constitute a typical multidimensional time series. Through this input structure, LSTM can capture the dynamic changes and dependencies of health indicators over time series [

13].

This article’s output is intended to be a health prediction value for one or more future time steps since the purpose is to forecast the patient’s state of health at a certain time step. The output dimensions are adjusted according to specific prediction tasks, such as predicting the future value of a single health indicator (such as blood pressure), or predicting multiple indicators (such as blood pressure, heart rate, and blood sugar) simultaneously.

3.3.3. Activation Function and Loss Function

In order to enhance the nonlinear mapping ability of the model, the LSTM hidden layer uses a hyperbolic tangent activation function to ensure that the network can capture nonlinear relationships in the time series. After the fully connected layer, the output layer uses a linear activation function to ensure that the model output matches the actual continuous health data.

In terms of loss function selection, this article adopts MSE as the objective function to measure the difference between predicted values and actual values. MSE, as a commonly used loss function in regression tasks, can effectively reflect the performance of the model in continuous value prediction. The optimization of the loss function is completed by the Adam optimizer, which combines adaptive learning rate and momentum to enable the model to converge faster during training while avoiding falling into local optima.

3.4. Model Training and Optimization

3.4.1. Training Strategy

This article adopts the method of small batch stochastic gradient descent. By dividing the dataset into multiple small batches and updating only the gradients of a portion of the samples during each training session, parameter updates and convergence are accelerated. In the experiment, this article set the batch size to 32, which can achieve a good balance between efficiency and performance. Compared to full gradient descent, small batch gradient descent not only reduces computational overhead, but also introduces noise, which helps to escape from local optima [

14].

3.4.2. Optimization Algorithm

In the selection of optimization algorithms, this article uses the Adam optimizer. Adam combines the ideas of momentum and adaptive learning rate to quickly and effectively optimize complex neural networks in most scenarios. The main advantage of Adam is that it accelerates convergence by adaptively adjusting the learning rate of each parameter, and performs well in sparse data or gradient instability.

3.4.3. Regularization and Prevention of Overfitting

Medical data is often limited, so models tend to perform well on training data but have poor generalization ability on testing data, which is known as overfitting. For this purpose, this article investigates the addition of a Dropout layer after the LSTM layer and fully connected layer, with a dropout rate set to 0.2. Dropout randomly sets the output of some neurons to 0 during each training session, forcing the model to not rely on specific neurons, thereby improving the model’s generalization ability and reducing the risk of overfitting.

3.4.4. Learning Rate Scheduling

The initial setting of the learning rate in this article is 0.001, but as the training process progresses, the learning rate should not remain fixed. In order to balance the fast convergence and stability of the model, this article adopts a learning rate decay strategy, as shown in Formula (5):

In Formula (5), represents the attenuated learning rate, represents the initial learning rate, represents the decay rate, and represents the time step. Specifically, when the validation set loss of the model no longer decreases within several epochs, this article proportionally decays the learning rate to 0.5 times its original value. This method of dynamically adjusting the learning rate can ensure that the model converges quickly in the early stages while steadily optimizing in the later stages of training, avoiding oscillations during the training process.

This article ensures the good performance of the LSTM model in processing medical time series data through reasonable dataset partitioning and small batch stochastic gradient descent. The learning rate scheduling and other operations further optimize the training process, prevent overfitting problems, and improve the model’s generalization ability. Finally, after a series of training and tuning, the LSTM model proposed in this article was able to achieve high prediction accuracy and stability in medical data prediction tasks, providing effective support for practical applications.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Experimental Preparation

- (1)

Dataset preparation

Selecting appropriate data from real healthcare datasets ensures that the datasets used have time series characteristics and contain key health indicators. The following datasets were primarily used in this study: the MIMIC-III/MIMIC-IV (publicly available hospital intensive care dataset containing detailed patient charts, signs, laboratory results, etc.), the National Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), the Medicare database (CMS) Public Use File, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), the SEER program database, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) data portal. These datasets were divided into training, validation, and test sets for the experiments in this paper to ensure the scientific validity and reliability of the model evaluation.

- (2)

Experimental environment configuration

To ensure the efficiency of model training and evaluation, the experiment needs to be run in a high-performance computing environment. The GPU model used in this experiment is NVIDIA’s Tesla T4, and the CPU is an 8-core processor with 16GB of RAM to handle larger medical datasets.

- (3)

Control experimental parameters

To compare the performance of LSTM models, other control models need to be prepared, such as:

ARIMA: it is a classic time series model that requires setting appropriate p, d, and q parameters.

GRU: GRU aims to solve the problems of gradient vanishing and exploding in RNN by setting hyperparameters similar to LSTM.

4.2. Experimental Analysis

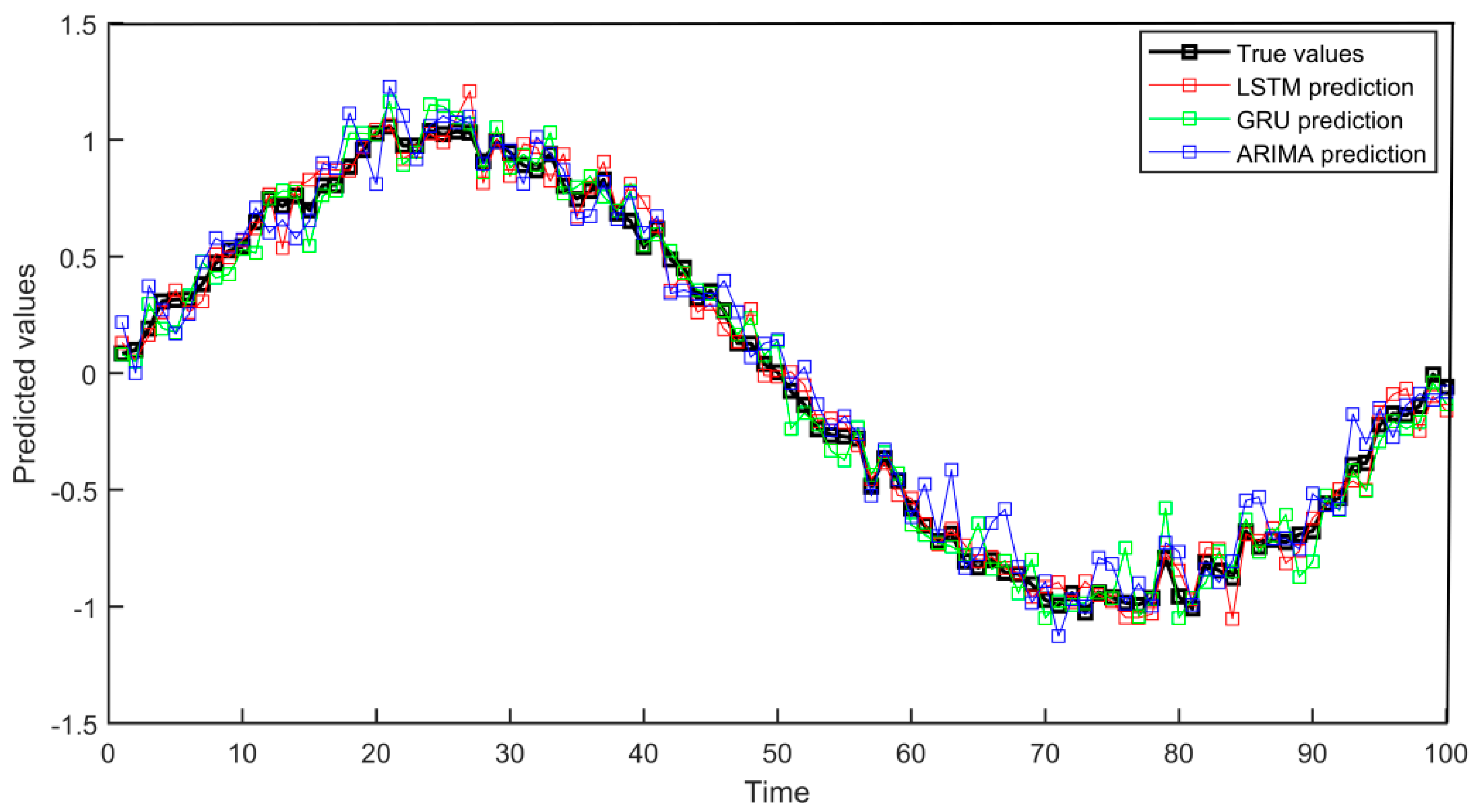

4.2.1. Prediction Accuracy Evaluation

This experiment compared the predictive performance of three models, LSTM, GRU, and ARIMA, by simulating medical time series data. In the experiment, models were trained using data from the past 80 time points, and these three models were used to predict health indicators for the next 20 time points. The prediction accuracy was evaluated through MSE and MAE. After the experiment, the performance of different models was compared through charts, as shown in

Figure 2:

Through experimental results analysis, the LSTM model performs the best in medical data prediction, with an MSE of 0.0056 and a MAE of 0.0601, significantly better than the MSE (0.0065) and MAE (0.0638) of GRU and the MSE (0.0109) and MAE (0.0831) of ARIMA models. In the above data conclusions, the LSTM model has significant advantages in capturing complex time series characteristics and can more accurately process medical data containing trends and noise, verifying its effectiveness in improving prediction accuracy.

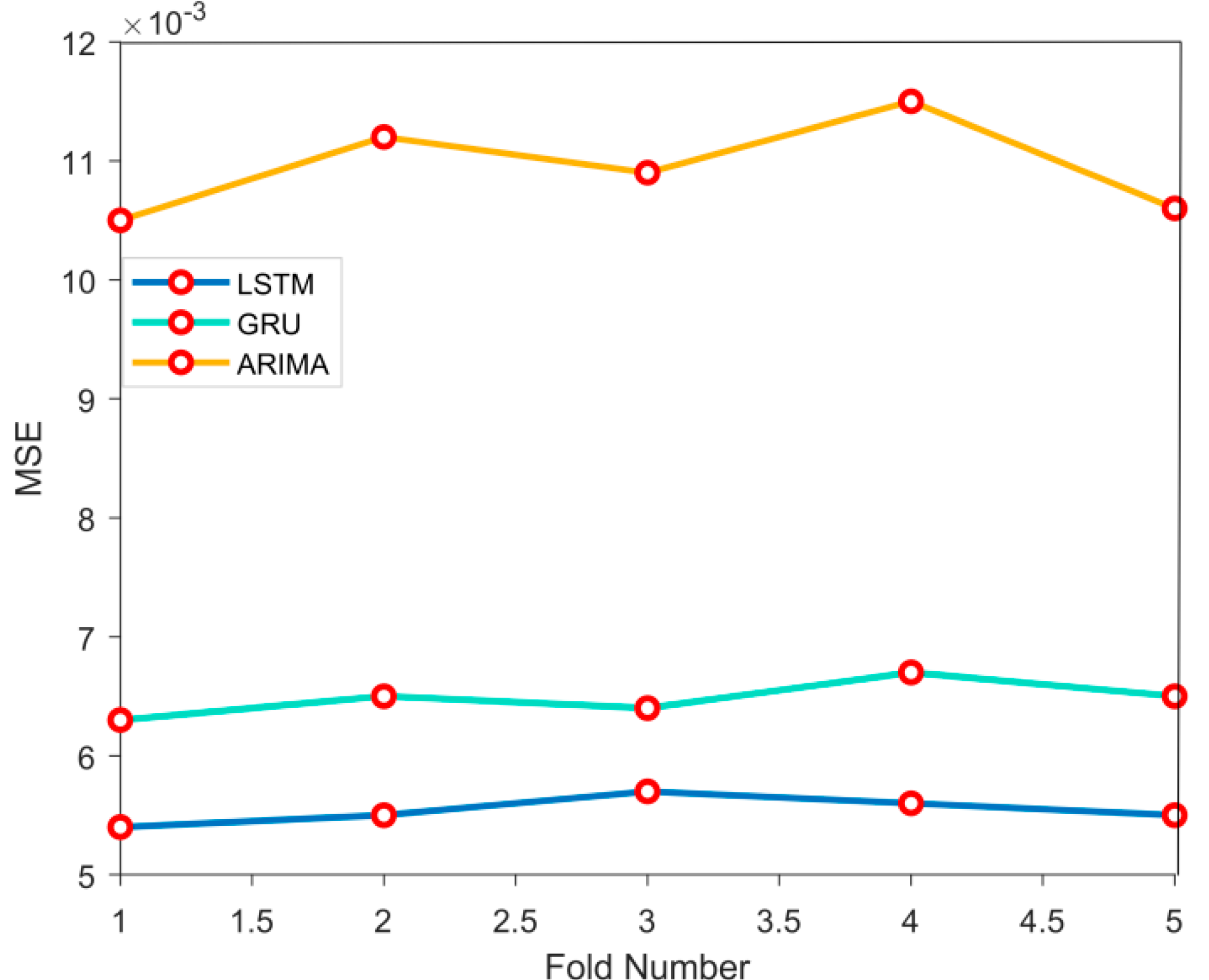

4.2.2. Model Robustness Evaluation

This experiment evaluates the robustness of LSTM, GRU, and ARIMA models through 5-fold cross validation. At each compromise, each model is trained based on the dataset and makes predictions on the dataset. By calculating the MSE of each fold, the performance stability of the model is ultimately evaluated, as shown in

Figure 3:

The results of 5-fold cross validation show that the LSTM model has the best robustness, with an error variance of 0.00034, significantly lower than the error variance of the GRU model (0.00047) and the ARIMA model (0.00112). In the above data conclusions, the LSTM model performs more stably under different data partitions and is less susceptible to the influence of dataset fluctuations.

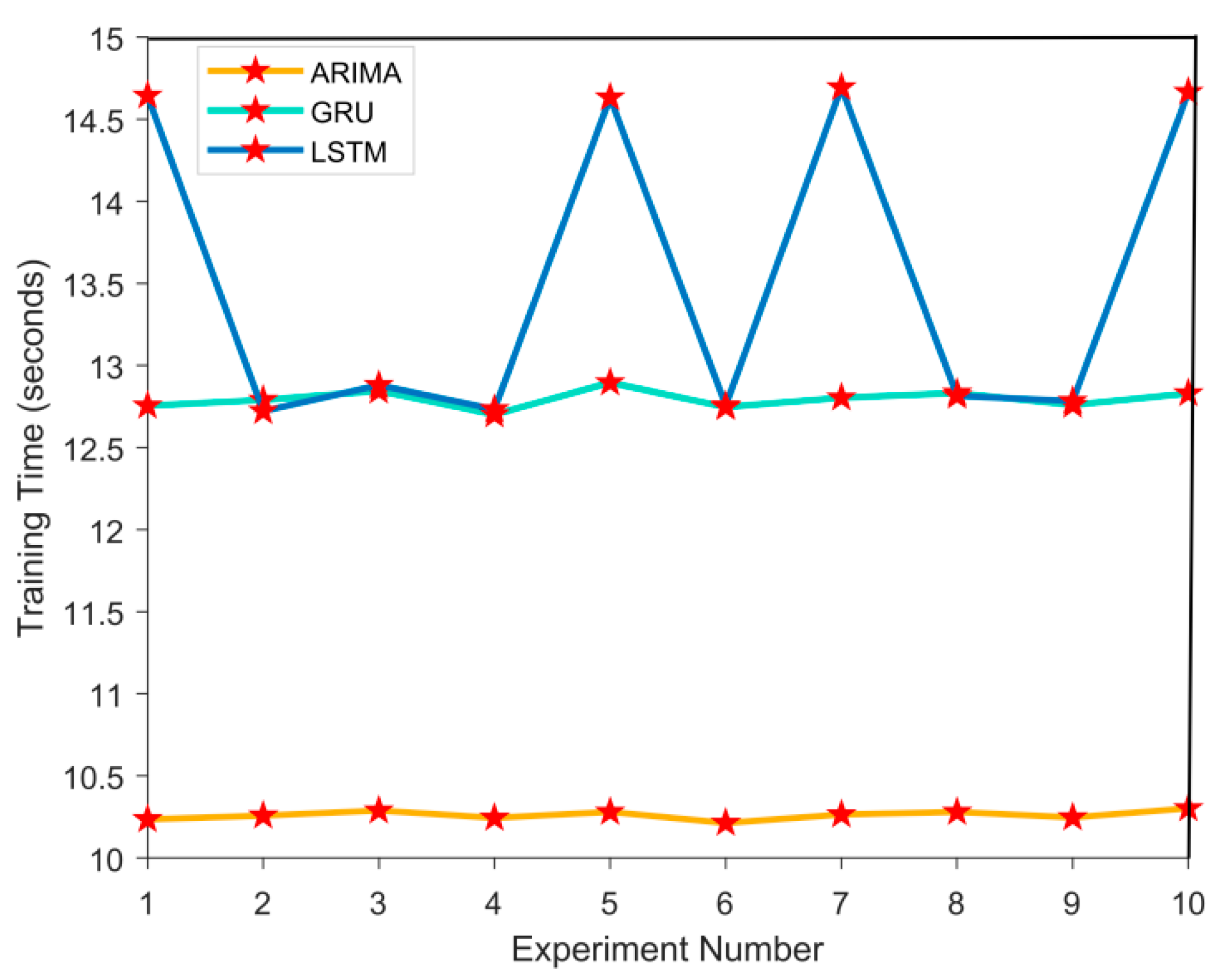

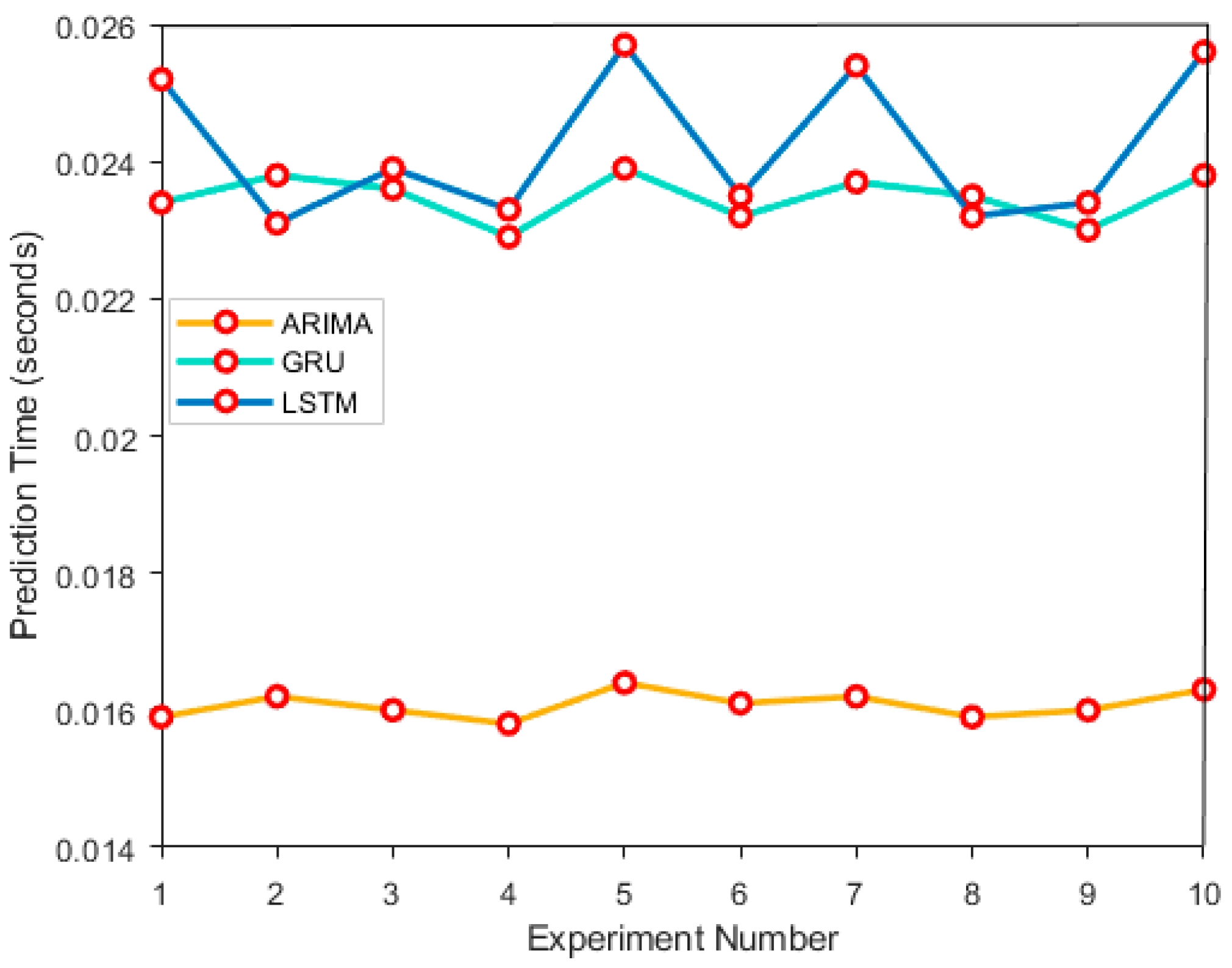

4.2.3. Model Calculation Efficiency Evaluation

In the model calculation efficiency evaluation experiment, the computational efficiency of ARIMA, GRU, and LSTM models was evaluated. By simulating medical time series data, recording the training time and prediction time of each model in 10 experiments. After the experiment, by observing the time fluctuations in each experiment, the performance differences between them in different experiments were analyzed, as shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5:

In

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, the computational efficiency results of ARIMA, GRU, and LSTM models are as follows. The average training time of ARIMA model is 10.2543 seconds, and the average prediction time is 0.0161 seconds; the GRU models are 12.7895 seconds and 0.0236 seconds, respectively; the LSTM models have a prediction time of 14.6521 seconds and an average prediction time of 0.0254 seconds. In the above data conclusions, ARIMA model performs the best in computational efficiency, followed by GRU, and LSTM has the longest training time, but it performs better in capturing complex time series features.

4.3. Experimental Summary

Through experimental evaluation of model prediction accuracy, robustness, and computational efficiency, the performance of ARIMA, GRU, and LSTM models can be comprehensively analyzed. In the prediction accuracy experiment, the mean square error and mean absolute error of the LSTM model are lower than those of GRU and ARIMA, demonstrating stronger nonlinear time series modeling ability. In robustness experiments, LSTM has the smallest error variance and better model stability; the ARIMA model is more sensitive to data partitioning and has significant fluctuations in errors. In the evaluation of computational efficiency, ARIMA model has the shortest training and prediction time, followed by GRU, and LSTM has the longest time consumption. However, its superiority in complex data feature extraction still has great application value. Overall, different models have their own emphasis on computational speed and predictive performance, and the selection should be based on specific needs when applied. As shown by Dai et al. in banking marketing tasks, combining large language model ensembles with multimodal feature extraction can significantly enhance downstream identification performance [

17]. This offers a promising direction for further enriching medical time series modeling using advanced ensemble structures.

5. Conclusions

This article cites a medical data prediction model based on LSTM algorithm, aiming to address the limitations of traditional prediction methods in processing high-dimensional and complex time series medical data. By preprocessing the data through cleaning, missing value filling, standardization, and combining domain knowledge for feature selection and construction, the quality and relevance of the input data for the model are ensured. The LSTM model, with its advantage in capturing long-term dependencies in time series, has performed well in experiments, not only improving the accuracy of health status prediction, but also demonstrating good robustness and stability. Compared with traditional time series models, LSTM has significantly superior predictive ability in complex data environments. However, despite significant improvements in the predictive performance of the model, there are still some shortcomings. For example, the model is sensitive to noisy data and the training process is time-consuming. Future research can further optimize the model structure, integrate with more types of intelligent algorithms, and improve resistance to noise and training efficiency. In addition, a wider range of datasets and feature selection methods can be explored to further enhance the model’s generalization ability and applicability in practical applications.

References

- Aldahiri, A.; Alrashed, B.; Hussain, W. Trends in using IoT with machine learning in health prediction system. Forecasting 2021, 3, 181–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harimoorthy, K.; Thangavelu, M. Retracted article: Multi-disease prediction model using improved SVM-radial bias technique in healthcare monitoring system. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2021, 12, 3715–3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Sounderajah, V.; Martin, G.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of deep learning in medical imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ Digit. Med. 2021, 4, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.; Montenegro-Marin, C.E. Secure prediction and assessment of sports injuries using deep learning based convolutional neural network. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2021, 12, 3399–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, J.; Li, J.; et al. Federated neural architecture search for medical data security. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 5628–5636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, A.; Iqbal, M.; Mehmood, Z.; et al. Prediction of heart disease using deep convolutional neural networks. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2021, 46, 3409–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, K.H.; Wang, L.; Yeow, A.Y.K.; et al. Artificial intelligence in sepsis early prediction and diagnosis using unstructured data in healthcare. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayon, S.I.; Islam, M.M.; Hossain, M.R. Coronary artery heart disease prediction: a comparative study of computational intelligence techniques. IETE J. Res. 2022, 68, 2488–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manickam, P.; Mariappan, S.A.; Murugesan, S.M.; et al. Artificial intelligence (AI) and internet of medical things (IoMT) assisted biomedical systems for intelligent healthcare. Biosensors 2022, 12, 562–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.J.; Wang, J.J.; Williamson, D.F.K.; et al. Algorithmic fairness in artificial intelligence for medicine and healthcare. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 7, 719–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Z.; Ye, F.; Yan, M.; et al. A survey on algorithms for intelligent computing and smart city applications. Big Data Min. Anal. 2021, 4, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzybowski, A.; Jin, K.; Wu, H. Challenges of artificial intelligence in medicine and dermatology. Clin. Dermatol. 2024, 42, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Liu, G.; Pan, Q. A review on representative swarm intelligence algorithms for solving optimization problems: Applications and trends. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2021, 8, 1627–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, F.; Masood, J.; Zahir, H.; et al. Novel approach to evaluate classification algorithms and feature selection filter algorithms using medical data. J. Comput. Cogn. Eng. 2023, 2, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, Z. Research and Application of Anti-Money Laundering Transaction Detection based on DeepSeek-R1 Small Model using Knowledge Distillation. Proceedings of the 2025 4th International Conference on Cyber Security, Artificial Intelligence and the Digital Economy. 2025:159–164.

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, Z. Application of AI in Real-Time Credit Risk Detection. In Proceedings of International Conference on AI and Financial Innovation. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2025. pp. 145–156.

- Dai, Y.; Feng, H.; Wang, Z.; Gao, Y. Advanced Large Language Model Ensemble for Multimodal Customer Identification in Banking Marketing. Preprints 2025. [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Lu, D.; Wang, Z. A Multimodal RAG Framework for Housing Damage Assessment: Collaborative Optimization of Image Encoding and Policy Vector Retrieval. arXiv arXiv:2509.09721, 2025. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).