Submitted:

08 October 2025

Posted:

10 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

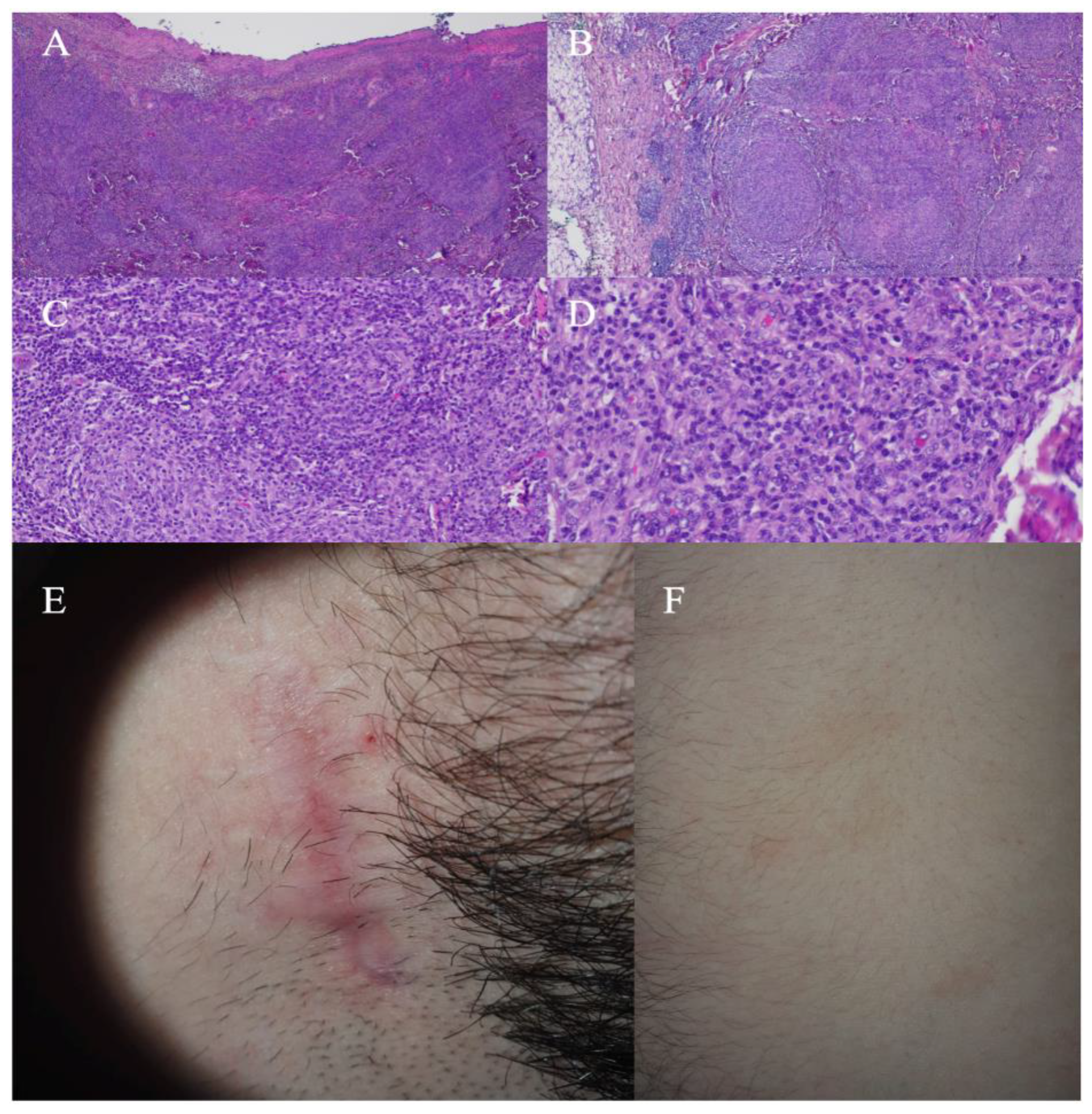

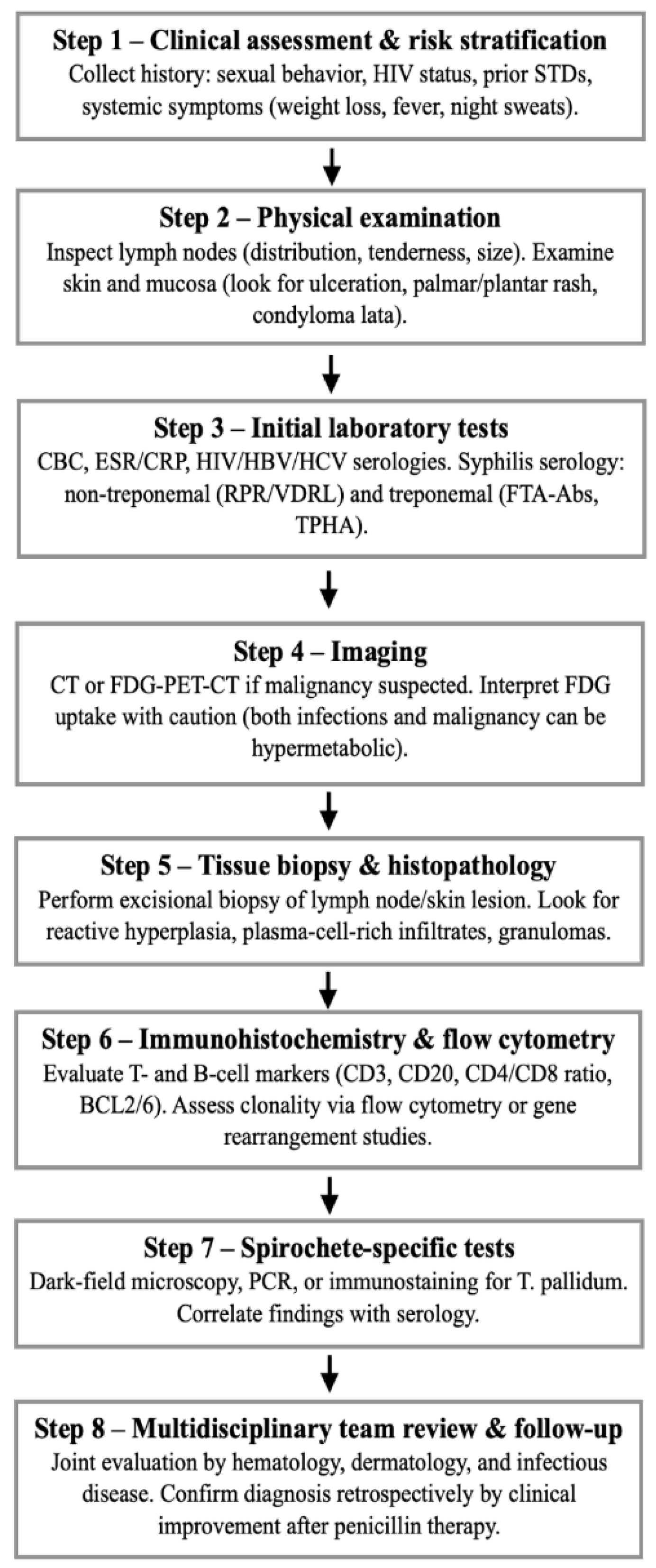

2. Case Report

4. Case Report

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FDG-PET-CT | Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography–computed tomography |

| CTCL | Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| FNAC | Fine needle aspiration cytology |

| CE-CT | Contrast-enhanced computed tomography |

| RPR | Rapid plasma reagin test |

| TPHA | Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay |

| STD | Sexually transmitted diseases |

| CBC | Complete blood count |

| ESR | Erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| VDRL | Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test |

| FTA-Abs | Fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

References

- Hook, E.W., 3rd; Marra, C.M. Acquired Syphilis in Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 1992, 326, 1060–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanem, K.G.; Ram, S.; Rice, P.A. The Modern Epidemic of Syphilis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, P. Syphilis. BMJ 2007, 334, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohta, A.; Furusyo, N.; Kishihara, Y.; Eiraku, K.; Murata, M.; Kainuma, M.; Toyoda, K.; Ogawa, E.; Hayashi, T.; Koga, T. Secondary Syphilis with Pulmonary Involvement. Intern. Med. 2018, 57, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, Y.-M.; Yang, S.-W.; Dai, M.-G.; Ye, B.; He, F.-Y. Gastric Syphilis Mimicking Gastric Cancer: A Case Report. World J. Clin. Cases 2021, 9, 7798–7804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerchione, C.; Maraolo, A.E.; Marano, L.; Pugliese, N.; Nappi, D.; Tosone, G.; Cimmino, I.; Cozzolino, I.; Martinelli, V.; Pane, F.; et al. Secondary Syphilis Mimicking Malignancy: A Case Report and Review of Literature. J. Infect. Chemother. 2017, 23, 576–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, M.; Fujii, Y.; Ozaki, K.; Urano, Y.; Iwasa, M.; Nakamura, S.; Fujii, S.; Abe, M.; Sato, Y.; Yoshino, T. Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Positive Secondary Syphilis Mimicking Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma. Diagn. Pathol. 2015, 10, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maci, C.; Canetti, D.; Tassan Din, C.; Bruzzesi, E.; Lucente, M.F.; Badalucco Ciotta, F.; Candela, C.; Ponzoni, M.; Castagna, A.; Nozza, S. Malignant Syphilis Mimicking Lymphoma in HIV: A Challenging Case and a Review of Literature Focusing on the Role of HIV and Syphilis Coinfection. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salah, H.; Prieto, V.; Cho, W.C.; Torres-Cabala, C.; Lenskaya, V. (virtual) the Misleading Syphilis: Two Cases Masquerading as Lymphomas. In Proceedings of the ASDP 61st Annual Meeting; ASDP Proceedings, November 4 2024.

- Komeno, Y.; Ota, Y.; Koibuchi, T.; Imai, Y.; Iihara, K.; Ryu, T. Secondary Syphilis with Tonsillar and Cervical Lymphadenopathy and a Pulmonary Lesion Mimicking Malignant Lymphoma. Am. J. Case Rep. 2018, 19, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodak, E.; David, M.; Rothem, A.; Bialowance, M.; Sandbank, M. Nodular Secondary Syphilis Mimicking Cutaneous Lymphoreticular Process. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1987, 17, 914–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.E.; Romanowski, B. Syphilis: Review with Emphasis on Clinical, Epidemiologic, and Some Biologic Features. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999, 12, 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohta, M. Secondary Syphilis with Generalized Lymphadenopathy and Pulmonary Involvement Mimicking Lymphoma. Intern Med 2019, 58, 1813–1816. [Google Scholar]

- Bledsoe, J.R.; Della-Torre, E.; Rovati, L.; Deshpande, V. IgG4-Related Disease: Review of the Histopathologic Features, Differential Diagnosis, and Therapeutic Approach. APMIS 2018, 126, 459–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| First author (Year) | Clinical presentation | Initial suspected diagnosis | Diagnostic pitfall | Final clue leading to syphilis diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ohta et al. (2018) [4] | Chest pain, rash, stomatitis, generalized lymphadenopathy, pulmonary nodules | Metastatic lung cancer / lymphoma | FDG-PET-CT uptake in mediastinal/axillary nodes and lung nodules, nonspecific lymph node biopsy | Positive RPR/TPHA serology, resolution with antibiotics, contracted lung nodular shadows following treatment |

| Cerchione et al. (2017) [6] | Generalized lymphadenopathy, fever, weight loss, rash, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, nocturnal sweating | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | FDG-PET-CT hypermetabolic nodes, FNAC showing reactive hyperplasia, delayed rash misinterpreted as viral exanthema, negative flow cytometry assay for B/T cell clonality | Treponemal serology positive after repeated testing, regression with penicillin, high-risk sexual intercourse |

| Yamashita et al. (2015) [7] | HIV positivity, ulcerated skin lesions, fever, headache, and myalgia without lymphadenopathy |

CTCL | Histology resembling CTCL with only CD8+ T-cell infiltrates | Negative TCR rearrangement, positive treponemal tests, detection of spirochetes |

| Lan et al. (2021) [5] | Epigastric pain, weight loss, endoscopic gastric mass | Gastric adenocarcinoma or lymphoma | Endoscopy and biopsy showing antral gastric ulcer with gastric retention, CE-CT and FDG-PET-CT suggesting gastric cancer |

Immunohistochemistry for Treponema pallidum, positive serology, promiscuous partner, histopathology negative for cancer cells |

| Salah et al. (2024) – Case 1 [9] | Generalized erythematous plaques | Primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma | Skin biopsy - lymphocytic infiltrate with CD3+T-cells and CD20+ B-cells, B-cells positive for BCL2 and BCL6. Predominance of kappapositive plasma cells |

Positive syphilis serology, immunohistochemical study showing spirochetes, negative flow cytometry |

| Salah et al. (2024) – Case 2 [9] | Severe gastritis and esophageal candidiasis followed by disseminated eruption | Drug eruption after antifungal therapy |

Biopsy -lymphocytic infiltrate with atypical CD3+, CD8+, TCRbetaF1+ CD7 + T-cells, immunoreactivity for TIA-1 and granzyme B |

Unremarkable bone marrow biopsy and flow cytometry, immunohistochemical study showing spirochetes, positive syphilis serology |

| Hodak et al. (1987) [11] | Cutaneous eruption with plasma cell infiltrate | Cutaneous lymphoma | Histology suggested lymphoma; histological reactive pattern | Serologic tests positive for syphilis, dark-field microscopy demonstrating spirochetes in a nodular lesion, clinical resolution after penicillin |

| Komeno et al. (2018) [10] | Bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy, pulmonary nodule, periportal lymph node |

Malignant lymphoma | Histology of lymph nodes with adipose tissue with fibrosis, infiltration by lymphocytes with mildly expanded nuclei | Treponemal serology positive, clinical resolution after penicillin, history of oral sex with partners |

| Maci et al. (2025) [8] | HIV positivity under antiretroviral therapy, five-day history of fever and multiple lymphadenopathies, lung consolidation |

Hematologic malignancy | Lymph node biopsy revealing disrupted architecture with multiple granulomas multinucleated giant cells, negative anti-treponema immunoreaction |

Serological tests, clinical resolution after penicillin, regression of the lung consolidation by FDG-PET-CT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).