Submitted:

10 October 2025

Posted:

13 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Angiogenesis

2.1. Activators of Angiogenesis

2.2. Antiangiogenic Factors

3. Intestinal Barrier

4. Intestinal Hemostasis in IBD

5. Angiogenesis in IBD

5.1. Angiogenesis and Microbiome in IBD

5.2. Treatment of Angiogenesis in IBD

5.3. Dual Role of Angiogenesis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guan, Q. A Comprehensive Review and Update on the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 2019, 7247238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, J.; Wu, G.D.; Albenberg, L.; Tomov, V.T. Gut microbiota and IBD: Causation or correlation? Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benelli, R.; Lorusso, G.; Albini, A.; Noonan, D.M. Cytokines and Chemokines as Regulators of Angiogenesis in Health and Disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2006, 12, 3101–3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajib, S.; Zahra, F.T.; Lionakis, M.S.; German, N.A.; Mikelis, C.M. Mechanisms of angiogenesis in microbe-regulated inflammatory and neoplastic conditions. Angiogenesis 2017, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, S.; Sans, M.; De La Motte, C.; Graziani, C.; West, G.; Phillips, M.H.; Pola, R.; Rutella, S.; Willis, J.; Gasbarrini, A.; et al. Angiogenesis as a Novel Component of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Pathogenesis. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 2060–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, N.; Gerber, H.-P.; LeCouter, J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cébe-Suarez, S.; Zehnder-Fjällman, A.; Ballmer-Hofer, K. The role of VEGF receptors in angiogenesis; complex partnerships. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2006, 63, 601–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, N. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor: Basic Science and Clinical Progress. Endocr. Rev. 2004, 25, 581–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felmeden, D.C.; Blann, A.D.; Lip, G.Y. Angiogenesis: basic patho-physiology and implications for disease. Eur Heart J 2003, 24, 586–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dachs, G.; Tozer, G. Hypoxia modulated gene expression: angiogenesis, metastasis and therapeutic exploitation. Eur. J. Cancer 2000, 36, 1649–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giatromanolaki, A.; Sivridis, E.; Maltezos, E.; Papazoglou, D.; Simopoulos, C.; Gatter, K.C.; Harris, A.L.; et al. Hypoxia inducible factor 1alpha and 2alpha overexpression in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Pathol 2003, 56, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paleolog, E.M.; Young, S.; Stark, A.C.; McCloskey, R.V.; Feldmann, M.; Maini, R.N. Modulation of angiogenic vascular endothelial growth factor by tumor necrosis factor alpha? and interleukin-1 in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998, 41, 1258–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottomley, M.J.; A Webb, N.J.; Watson, C.J.; Holt, P.J.L.; Freemont, A.J.; Brenchley, P.E.C. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis spontaneously secrete vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF): specific up-regulation by tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) in synovial fluid. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1999, 117, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddlestone, J.; Bandarra, D.; Rocha, S. The role of hypoxia in inflammatory disease (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 35, 859–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakirtzi, K.; West, G.; Fiocchi, C.; Law, I.K.M.; Iliopoulos, D.; Pothoulakis, C. The Neurotensin–HIF-1α–VEGFα Axis Orchestrates Hypoxia, Colonic Inflammation, and Intestinal Angiogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 2014, 184, 3405–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, R.H.; Kantarjian, H.M.; Cortes, J.E. Biology of Platelet-Derived Growth Factor and Its Involvement in Disease. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2006, 81, 1241–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ierardi, E.; Giorgio, F.; Zotti, M.; Rosania, R.; Principi, M.; Marangi, S.; Della Valle, N.; De Francesco, V.; Di Leo, A.; Ingrosso, M.; et al. Infliximab therapy downregulation of basic fibroblast growth factor/syndecan 1 link: a possible molecular pathway of mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis. J. Clin. Pathol. 2011, 64, 968–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanazawa, S.; Tsunoda, T.; Onuma, E.; Majima, T.; Kagiyama, M.; Kikuchi, K. VEGF, basic-FGF, and TGF-β in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: a novel mechanism of chronić intestinal inflammation. Amer J. Gastroenterol. 2001, 96, 822–828. [Google Scholar]

- Itoh, H.; Kataoka, H. Roles of hepatocyte growth factor activator (HGFA) and its inhibitor HAI-1 in the regeneration of injured gastrointestinal mucosa. J. Gastroenterol. 2002, 37, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Tu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, S. Placental growth factor enhances angiogenesis in human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells via PI3K/Akt pathway: Potential implications of inflammation bowel disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 470, 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeliet, P. Angiogenesis in life, disease and medicine. Nature 2005, 438, 932–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yancopoulos, G.D.; Davis, S.; Gale, N.W.; Rudge, J.S.; Wiegand, S.J.; Holash, J. Vascular-specific growth factors and blood vessel formation. Nature 2000, 407, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Kim, J.-H.; Moon, S.-O.; Kwak, H.J.; Kim, N.-G.; Koh, G.Y. Angiopoietin-2 at high concentration can enhance endothelial cell survival through the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase/Akt signal transduction pathway. Oncogene 2000, 19, 4549–4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobov, I.B.; Brooks, P.C.; Lang, R.A. Angiopoietin-2 displays VEGF-dependent modulation of capillary structure and endothelial cell survival in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 11205–11210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, U.; Reiss, Y.; Scharpfenecker, M.; Grunow, V.; Koidl, S.; Thurston, G.; Gale, N.W.; Witzenrath, M.; Rosseau, S.; Suttorp, N.; et al. Angiopoietin-2 sensitizes endothelial cells to TNF-α and has a crucial role in the induction of inflammation. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linares, P.M.; Chaparro, M.; Gisbert, J.P. Angiopoietins in inflammation and their implication in the development of inflammatory bowel disease. A review. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2014, 8, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zak, S.; Treven, J.; Nash, N.; Gutierrez, L.S. Lack of thrombospondin-1 increases angiogenesis in a model of chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2007, 23, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, S. Negative Regulators of Angiogenesis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Thrombospondin in the Spotlight. Pathobiology 2008, 75, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Masià, D.; Díez, I.; Calatayud, S.; Hernández, C.; Cosín-Roger, J.; Hinojosa, J.; Esplugues, J.V.; Barrachina, M.D. Induction of CD36 and Thrombospondin-1 in Macrophages by Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 and Its Relevance in the Inflammatory Process. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e48535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhadi, A.; Banan, A.; Fields, J.; Keshavarzian, A. Intestinal barrier: An interface between health and disease. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2003, 18, 479–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadoni, I.; Zagato, E.; Bertocchi, A.; Paolinelli, R.; Hot, E.; Di Sabatino, A.; Caprioli, F.; Bottiglieri, L.; Oldani, A.; Viale, G.; et al. A gut-vascular barrier controls the systemic dissemination of bacteria. Science 2015, 350, 830–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brescia, P.; Rescigno, M. The gut vascular barrier: A new player in the gut-liver-brain axis. Trends Mol. Med 2021, 27, 844–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mankertz, J.; Schulzke, J.-D. Altered permeability in inflammatory bowel disease: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2007, 23, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stürzl, M.; Kunz, M.; Krug, S.M.; Naschberger, E. Angiocrine Regulation of Epithelial Barrier Integrity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 643607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neurath, M.F. Cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pober, J.S.; Sessa, W.C. Evolving functions of endothelial cells in inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himadri, R.; Shalini, B.; Seppo, Y.H. Biology of vascular endothelial growth factors. FEBS Letters 2006, 580, 2879–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadoni, I.; Fornasa, G.; Rescigno, M. Organ-specific protection mediated by cooperation between vascular and epithelial barriers. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Posadas, R.; Stürzl, M.; Atreya, I.; Neurath, M.F.; Britzen-Laurent, N. Interplay of GTPases and Cytoskeleton in Cellular Barrier Defects during Gut Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabouridis, P.S.; Lasrado, R.; McCallum, S.; Chng, S.H.; Snippert, H.J.; Clevers, H.; Pettersson, S.; Pachnis, V. Microbiota Controls the Homeostasis of Glial Cells in the Gut Lamina Propria. Neuron 2015, 85, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, K.; Sasaki, H.; Furuse, M.; Tsukita, S. Endothelial claudin: claudin-5/TMVCF constitutes tight junction strands in endothelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 1999, 147, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günzel, D.; Yu, A.S.L. Claudins and the Modulation of Tight Junction Permeability. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 525–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolburg, H.; Wolburg-Buchholz, K.; Kraus, J.; Rascher-Eggstein, G.; Liebner, S.; Hamm, S.; Duffner, F.; Grote, E.-H.; Risau, W.; Engelhardt, B. Localization of claudin-3 in tight junctions of the blood-brain barrier is selectively lost during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and human glioblastoma multiforme. Acta Neuropathol. 2003, 105, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, A.; Dhillon, A.; Rowles, P.; Sawyerr, A.; Pittilo, R.; Lewis, A.; Pounder, R. Pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease: multifocal gastrointestinal infarction. Lancet 1989, 334, 1057–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakefield, A.J.; Sankey, E.A.; Dhillon, A.P.; Sawyerr, A.; More, L.; Sim, R.; Pittilo, R.M.; Rowles, P.M.; Hudson, M.; Lewis, A.A.; et al. Granulomatous vasculitis in crohn's disease. Gastroenterology More, L.; Sim, R,; Hudson, M.; et al. Immunohistochemical study of tissue factor expression in normal intestine and idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Pathol 1993, 46, 703-708.. 1991, 100, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, H.; Granger, D.N. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: a paradigm for the link between coagulation and inflammation. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009, 15, 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhillon, A.; Anthony, A.; Sim, R.; Wakefield, A.; Sankey, E.; Hudson, M.; Allison, M.; Pounder, R. Mucosal capillary thrombi in rectal biopsies. Histopathology 1992, 21, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, S.; Katz, J.A.; Saibeni, S.; et al. Activated platelets are the source of elevated levels of soluble CD40 ligand in the circulation of inflammatory bowel disease patients. Gut 2003, 52, 1435–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, S.; de la Motte, C.; Sturm, A.; Vogel, J.D.; A West, G.; A Strong, S.; A Katz, J.; Fiocchi, C. Platelets trigger a CD40-dependent inflammatory response in the microvasculature of inflammatory bowel disease patients. Gastroenterology 2003, 124, 1249–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutela, S.; Vetrano, S.; Correale, C.; Graziani, C.; Sturm, A.; Spinelli, A.; et al. Enhanced platelet adhesion induces angiogenesis in intestinal inflammation and inflammatory bowel disease microvasculature. J Cell Mol Med 2011, 15, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, E.; Porte, R.J.; A Knot, E.; Verheijen, J.H.; Dees, J. Disturbed fibrinolysis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. A study in blood plasma, colon mucosa, and faeces. Gut 1989, 30, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Wouwer, M.; Collen, D.; Conway, E.M. Thrombomodulin-Protein C-EPCR System: integrated to regulate coagulation and inflammation. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004, 24, 1374–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetrano, S.; Ploplis, V.A.; Sala, E.; Sandoval-Cooper, M.; Donahue, D.L.; Correale, C.; Arena, V.; Spinelli, A.; Repici, A.; Malesci, A.; et al. Unexpected role of anticoagulant protein C in controlling epithelial barrier integrity and intestinal inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011, 108, 19830–19835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faioni, E.M.; Ferrero, S.; Fontana, G.; Gianelli, U.; Ciulla, M.M.; Vecchi, M.; Saibeni, S.; Biguzzi, E.; Cordani, N.; Franchi, F.; et al. Expression of endothelial protein C receptor and thrombomodulin in the intestinal tissue of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 32, S266–S270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Cromer, W.; Mathis, J.M.; Granger, D.N.; Chaitanya, G.V.; Alexander, J.S. Role of the endothelium in inflammatory bowel diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 578–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkim, C.; Alkim, H.; Koksal, A.R.; Boga, S.; Sen, I. Angiogenesis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Int. J. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 970890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stadnicki, A.; Machnik, G.; Klimacka-Nawrot, E.; Wolanska-Karut, A.; Labuzek, K. Transforming growth factor-β1 and its receptors in patients with ulcerative colitis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2009, 9, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

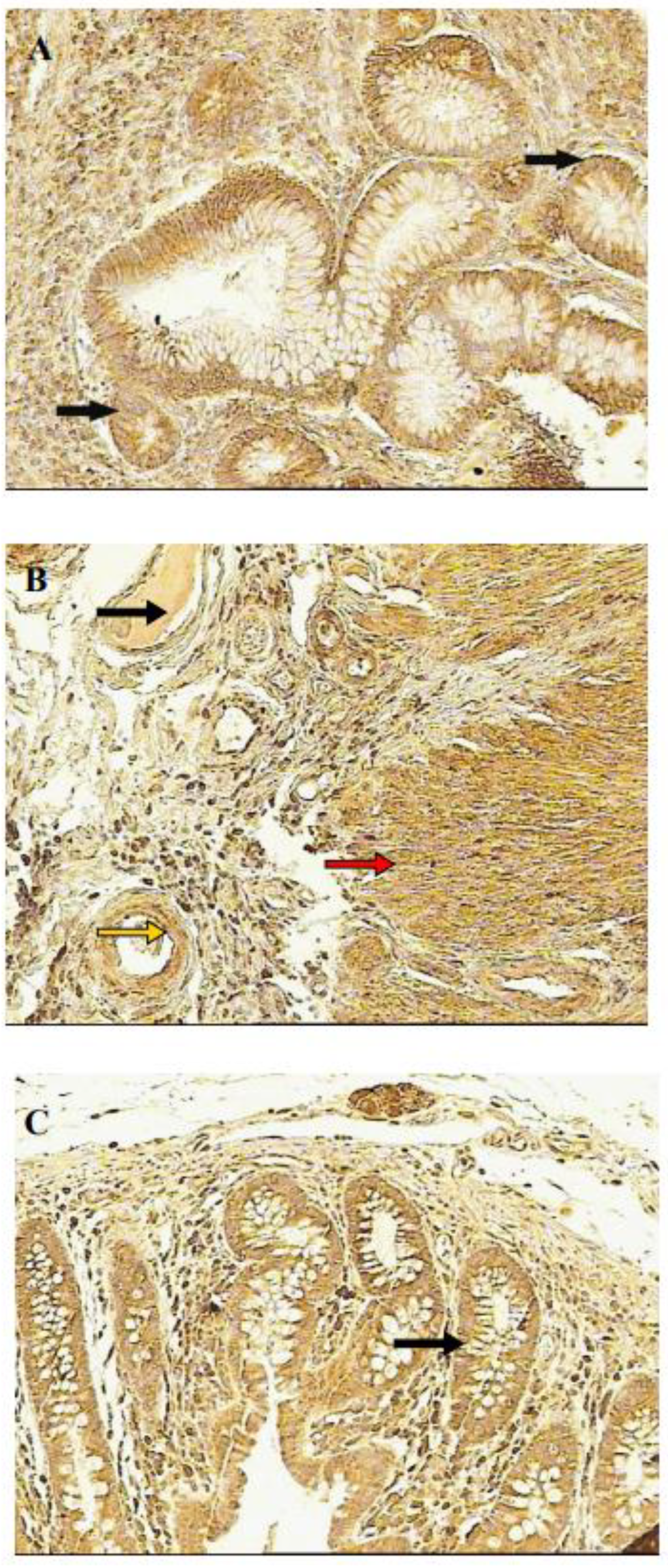

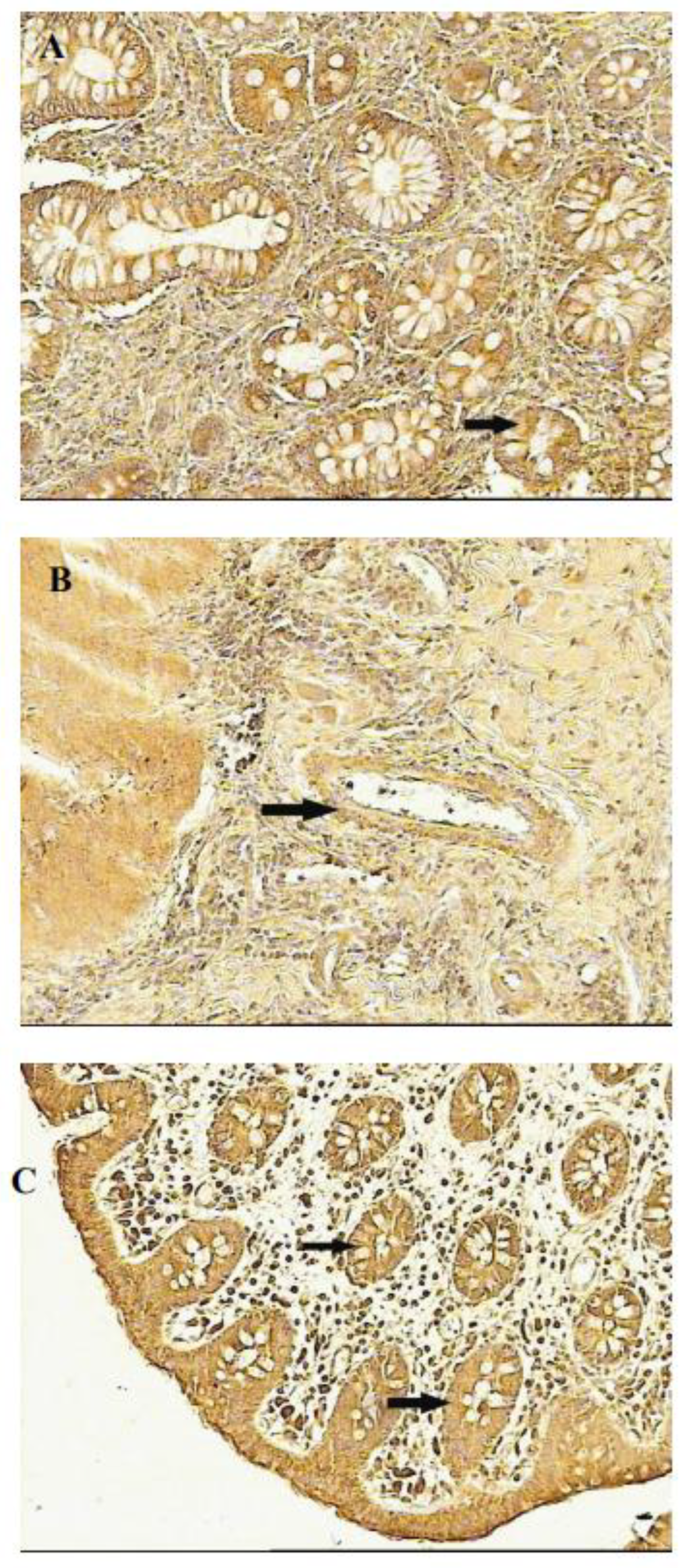

- Frysz-Naglak, D.; Fryc, B.; Klimacka-Nawrot, E.; Mazurek, U.; Suchecka, W.; Kajor, M.; Kurek, J.; Stadnicki, A. Expression, localization and systemic concentration of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors in patients with ulcerative colitis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2011, 11, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaldaferri, F.; Vetrano, S.; Sans, M.; Arena, V.; Straface, G.; Stigliano, E.; Repici, A.; Sturm, A.; Malesci, A.; Panes, J.; et al. VEGF-A Links Angiogenesis and Inflammation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Pathogenesis. Gastroenterology 2009, 136, 585–595.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousvaros, A.; Leichtner, A.; Zurakowski, D.; Kwon, J.; Law, T.; Keough, K.; Fishman, S. Elevated Serum Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Children and Young Adults with Crohn's Disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1999, 44, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himadri, R.; Shalini, B.; Seppo, Y.H. Biology of vascular endothelial growth factors. FEBS Letters 2006, 580, 2879–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proczka, R.M.; Polański, J.A.; Małecki, M.; Wikieł, K. The significance of vascular endothelial growth factor in the neoangiogenesis process. The role of hypoxia in the endothelial cells proliferation process and in the formation of collateral circulation. Acta Angiol 2003, 9, 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Griga, T.; Gutzeit, A.; Sommerkamp, C.; May, B. Increased production of vascular endothelial growth factor by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1999, 11, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griga, T.; May, B.; Pfisterer, O.; Müller, K.-M.; Brasch, F. Immunohistochemical localization of vascular endothelial growth factor in colonic mucosa of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Hepato-Gastroenterology 2002, 49, 116–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kapsoritakis, A.; Sfiridaki, A.; Maltezos, E.; Simopoulos, K.; Giatromanolaki, A.; Sivridis, E.; Koukourakis, M.I. Vascular endothelial growth factor in inflammatory bowel disease. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2003, 18, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstanova, G.; Deng, X.; French, S.W.; Lungo, W.; Paunovic, B.; Khomenko, T.; Ahluwalia, A.; Kaplan, T.; Dacosta-Iyer, M.; Tarnawski, A.; et al. Early endothelial damage and increased colonic vascular permeability in the development of experimental ulcerative colitis in rats and mice. Mod. Pathol. 2012, 92, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakatos, G.; Hritz, I.; Varga, M.Z.; Juhász, M.; Miheller, P.; Cierny, G.; Tulassay, Z.; Herszényi, L. The Impact of Matrix Metalloproteinases and Their Tissue Inhibitors in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Dig. Dis. 2012, 30, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzystek-Korpacka, M.; Neubauer, K.; Matusiewicz, M. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB reflects clinical, inflammatory and angiogenic disease activity and oxidative stress in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Biochem. 2009, 42, 1602–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macé, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Coron, E.; Le Rhun, M.; Boureille, A.; Bossard, C.; Mosnier, J.; Matysiak-Budnik, T.; Tarnawski, A.S. Confocal laser endomicroscopy: A new gold standard for the assessment of mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 30, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ippolito, C.; Colucci, R.; Segnani, C.; Errede, M.; Girolamo, F.; Virgintino, D.; Dolfi, A.; Tirotta, E.; Buccianti, P.; Di Candio, G.; et al. Fibrotic and Vascular Remodelling of Colonic Wall in Patients with Active Ulcerative Colitis. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2016, 10, 1194–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pousa, I.D.; Maté, J.; Salcedo-Mora, X.; Abreu, M.T.; Moreno-Otero, R.; Gisbert, J.P. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor and angiopoietin systems in serum of Crohnʼs disease patients. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2008, 14, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutroubakis, I.E.; Xidakis, C.; Karmiris, K.; Sfiridaki, A.; Kandidaki, E.; Kouroumalis, E.A. Potential role of soluble angiopoietin-2 and Tie-2 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 36, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizaki, A.; Nakayama, T.; Naito, S.; Sekine, I. Expression Patterns of Angiopoietin-1, -2, and Tie-2 Receptor in Ulcerative Colitis Support Involvement of the Angiopoietin/Tie Pathway in the Progression of Ulcerative Colitis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2008, 54, 2094–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotan, I.; Allez, M.; Danese, S.; Keir, M.; Tole, S.; McBride, J. The role of integrins in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease: Approved and investigational anti-integrin therapies. Med. Res. Rev. 2020, 40, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colman, R.W. Regulation of Angiogenesis by the Kallikrein-Kinin System. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2006, 12, 2599–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadnicki, A. Intestinal tissue kallikrein-kinin system in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2011, 17, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljameeli AM; Aswaid B; Bharati B; Gohri V; Mohite M, Singh S; Chidrawar V et al. Chloride channels and mast cell function: pioneering new frontiers in IBD therapy. Mol Cell Biochem 2025, 480, 3951–3969.

- He, S.-H. Key role of mast cells and their major secretory products in inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2004, 10, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandagale, A.; Reinhardt, C. Gut microbiota ndash architects of small intestinal capillaries. Front. Biosci. 2018, 23, 752–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishima, Y.; Sartor, R.B. Manipulating resident microbiota to enhance regulatory immune function to treat inflammatory bowel diseases. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 55, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.T.; Amos, G.C.A.; Murphy, A.R.J.; Murch, S.; Wellington, E.M.H.; Arasaradnam, R.P. Microbial imbalance in inflammatory bowel disease patients at different taxonomic levels. Gut Pathog. 2020, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinhardt, C.; Bergentall, M.; Greiner, T.U.; Schaffner, F.; Östergren-Lundén, G.; Petersen, L.C.; Ruf, W.; Bäckhed, F. Tissue factor and PAR1 promote microbiota-induced intestinal vascular remodelling. Nature 2012, 483, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirbel, A.; Kessler, S.; Rieder, F.; West, G.; Rebert, N.; Asosingh, K.; McDonald, C.; Fiocchi, C. Pro-Angiogenic Activity of TLRs and NLRs: A Novel Link Between Gut Microbiota and Intestinal Angiogenesis. Gastroenterology 2013, 144, 613–623.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.-S.; Xu, F.; Bagchi, A.; Herrup, E.; Prakash, A.; Valentine, C.; Kulkarni, H.; Wilhelmsen, K.; Warren, S.; Hellman, J. Bacterial Lipoprotein TLR2 Agonists Broadly Modulate Endothelial Function and Coagulation Pathways In Vitro and In Vivo. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirbel, A.; Rebert, N.; Sadler, T.; West, G.; Rieder, F.; Wagener, C.; Horst, A.; Sturm, A.; de la Motte, C.; Fiocchi, C. Mutual Regulation of TLR/NLR and CEACAM1 in the Intestinal Microvasculature: Implications for IBD Pathogenesis and Therapy. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 25, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez, A.; Francés, R.; Amorós, A.; Zapater, P.; Garmendia, M.; Ndongo, M.; Caño, R.; Jover, R.; Such, J.; Pérez-Mateo, M. Cytokine association with bacterial DNA in serum of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2009, 15, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez, A.; Zapater, P.; Juanola, O.; Sempere, L.; García, M.; Laveda, R.; Martínez, A.; Scharl, M.; González-Navajas, J.M.; Such, J.; et al. Gut Bacterial DNA Translocation is an Independent Risk Factor of Flare at Short Term in Patients With Crohn’s Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 111, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzoni Ch; Ochana B; Focht G; Harpenas F; Quteineh A; Orlansky E et al. Human DNA levels in feces reflect gut inflammation and associate with presence of gut species in IBD patients across the age spectrum. Res Sq 2025 :rs.3.rs-6809327. [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, S.T.; Mullish, B.H.; Olbei, M.L.; Danckert, N.P.; Valdivia-Garcia, M.A.; Serrano-Contreras, J.I.; Chrysostomou, D.; Balarajah, S.; Perry, R.W.; Thomas, J.P.; et al. Deciphering the microbiome–metabolome landscape of an inflammatory bowel disease inception cohort. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2527863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, K.R.; Halliday, M.I.; Barclay, G.R.; et al. Significance of systemic endotoxemia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 1995, 36, 897–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo, Ó.P.; Román, A.L.S.; Arbizu, E.A.; Martínez, A.d.l.H.; Sevillano, E.R.; Martínez, A.A. Serum lipopolysaccharide-binding protein in endotoxemic patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2007, 13, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navabi, S.; Gorrepati, V.S.; Yadav, S.; Chintanaboina, J.; Maher, S.; Demuth, P.; Stern, B.; Stuart, A.; Tinsley, A.; Clarke, K.; et al. Influences and Impact of Anxiety and Depression in the Setting of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 2303–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, G.; Rosenfeld, G.; Leung, Y.; Qian, H.; Raudzus, J.; Nunez, C.; Bressler, B. Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 2017, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjina, I.T.; Zivkovic, P.M.; Matetic, A.; Rusic, D.; Vilovic, M.; Bajo, D.; Puljiz, Z.; Tonkic, A.; Bozic, J. Impaired neurocognitive and psychomotor performance in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Błoński W, Stadnicki A, Lichtenstein G., Burke, A. Infliximab use in ulcerative colitis. In: Ulcerative Colitis. The complete quid to medical management. Ed: GR Lichtenstein, EJ Scherl New York Slack Inc 2011, 237-254.

- Rutella, S.; Fiorino, G.; Vetrano, S.; Correale, C.; Spinelli, A.; Pagano, N.; Arena, V.; Maggiano, N.; Repici, A.; Malesci, A.; et al. Infliximab Therapy Inhibits Inflammation-Induced Angiogenesis in the Mucosa of Patients With Crohn's Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 106, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algaba, A.; Linares, P.M.; Fernández-Contreras, M.; Figuerola, A.; Calvet, X.; Guerra, I.; et al. The effects of infliximab or adalimumab on vascular endothelial growth factor and angiopoietin 1 angiogenic factor levels in inflammatory bowel disease: serial observations in 37 patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014, 20, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danese, S.; Sans, M.; Scaldaferri, F.; Sgambato, A.; Rutella, S.; Cittadini, A.; Piqué, J.M.; Panes, J.; Katz, J.A.; Gasbarrini, A.; et al. TNF-α Blockade Down-Regulates the CD40/CD40L Pathway in the Mucosal Microcirculation: A Novel Anti-Inflammatory Mechanism of Infliximab in Crohn’s Disease. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 2617–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstanova, G.; Khomenko, T.; Deng, X.; Chen, L.; Tarnawski, A.; Ahluwalia, A.; Szabo, S.; Sandor, Z. Neutralizing Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) Antibody Reduces Severity of Experimental Ulcerative Colitis in Rats: Direct Evidence for the Pathogenic Role of VEGF. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009, 328, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magro, F.; Costa, C. Long-standing remission of Crohn’s disease under imatinib therapy in a patient with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2006, 12, 1087–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coriat, R.; Mir, O.; Leblanc, S.; Ropert, S.; Brezault, C.; Chaussade, S.; Goldwasser, F. Feasibility of anti-VEGF agent bevacizumab in patients with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2010, 17, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapani, S.; Chu, D.; Wu, S. Risk of gastrointestinal perforation in patients with cancer treated with bevacizumab: a meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, R.A.; Brady, M.F.; Bookman, M.A.; Monk, B.J.; Walker, J.L.; Homesley, H.D.; Fowler, J.; Greer, B.E.; Boente, M.; Fleming, G.F.; et al. Risk Factors for GI Adverse Events in a Phase III Randomized Trial of Bevacizumab in First-Line Therapy of Advanced Ovarian Cancer: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1210–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loriot, Y.; Boudou-Rouquette, P.; Billemont, B.; Ropert, S.; Goldwasser, F. Acute exacerbation of hemorrhagic rectocolitis during antiangiogenic therapy with sunitinib and sorafenib. Ann. Oncol. 2008, 19, 1975–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Gómez, R.G.; Grecea, M.; Gallois, C.; Boige, V.; Pautier, P.; Pistilli, B.; Planchard, D.; Malka, D.; Ducreux, M.; Mir, O. Safety and Efficacy of Bevacizumab in Cancer Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Cancers 2022, 14, 2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwenberg, M.; D’haens, G. Next-Generation Therapeutics for IBD. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2015, 17, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feagan, B.G.; Rutgeerts, P.; Sands, B.E.; Hanauer, S.; Colombel, J.-F.; Sandborn, W.J.; Van Assche, G.; Axler, J.; Kim, H.-J.; Danese, S.; et al. Vedolizumab as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. New Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandborn, W.J.; Feagan, B.G.; Rutgeerts, P.; Hanauer, S.; Colombel, J.-F.; Sands, B.E.; Lukas, M.; Fedorak, R.N.; Lee, S.; Bressler, B.; et al. Vedolizumab as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Crohn’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zundler, S.; Schillinger, D.; Fischer, A.; Atreya, R.; Lopez-Posadas, R.; Watson, A.; Neufert, C.; et al. Blockade of alpha Ebeta7 integrin suppresses accumulation of CD8+ and Th9 lymphocytes from patients with IBD in the inflamed gut in vivo. Gut 2017, 66, 1936–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danese, S.; Sans, M.; Spencer, D.M.; Beck, I.; Doñate, F.; Plunkett, M.L.; de la Motte, C.; Redline, R.; E Shaw, D.; Levine, A.D.; et al. Angiogenesis blockade as a new therapeutic approach to experimental colitis. Gut 2007, 56, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biazzo, M.; Deidda, G. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation as New Therapeutic Avenue for Human Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartor, B. Beyond random fecal microbial transplants: next generation personalized approaches to normalize dysbiotic microbiota for treating IBD. Gastrenterol Clin North Amer 2025, 54, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Xiao, H.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, S.; Luo, D.; Zheng, Q.; et al. Faecal microbiota transplantation protects against radiation-induced toxicity. EMBO Mol Med 2017, 9, 448–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dignass, A.U.; Podolsky, D.K. Epithelial restitution and intestinal repair. In Kirsner’s inflammatory bowel diseases; Sartor, R.B., Sandborn, W.J., Eds.; Saunders: Philadelphia, 2004; pp. 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X.; Szabo, S.; Khomenko, T.; Tolstanova, G.; Paunovic, B.; French, S.W.; Sandor, Z. Novel Pharmacologic Approaches to the Prevention and Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2012, 19, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Nightingale, J.M.; West, K.P.; Berlanga-Acosta, J.; Playford, R.J. Epidermal Growth Factor Enemas with Oral Mesalamine for Mild-to-Moderate Left-Sided Ulcerative Colitis or Proctitis. New Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paunovic, B.; Deng, X.; Khomenko, T.; Ahluwalia, A.; Tolstanova, G.; Tarnawski, A.; Szabo, S.; Sandor, Z. Molecular Mechanisms of Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor Effect on Healing of Ulcerative Colitis in Rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2011, 339, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, M.V.; Nagy, J.A.; Senger, D.R. Active Rac1 improves pathologic VEGF neovessel architecture and reduces vascular leak: mechanistic similarities with angiopoietin-1. Blood 2011, 117, 1751–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, U.P.; Singh, N.P.; Murphy, E.A.; Price, R.L.; Fayad, R.; Nagarkatti, M.; Nagarkatti, P.S. Chemokine and cytokine levels in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Cytokine 2016, 77, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

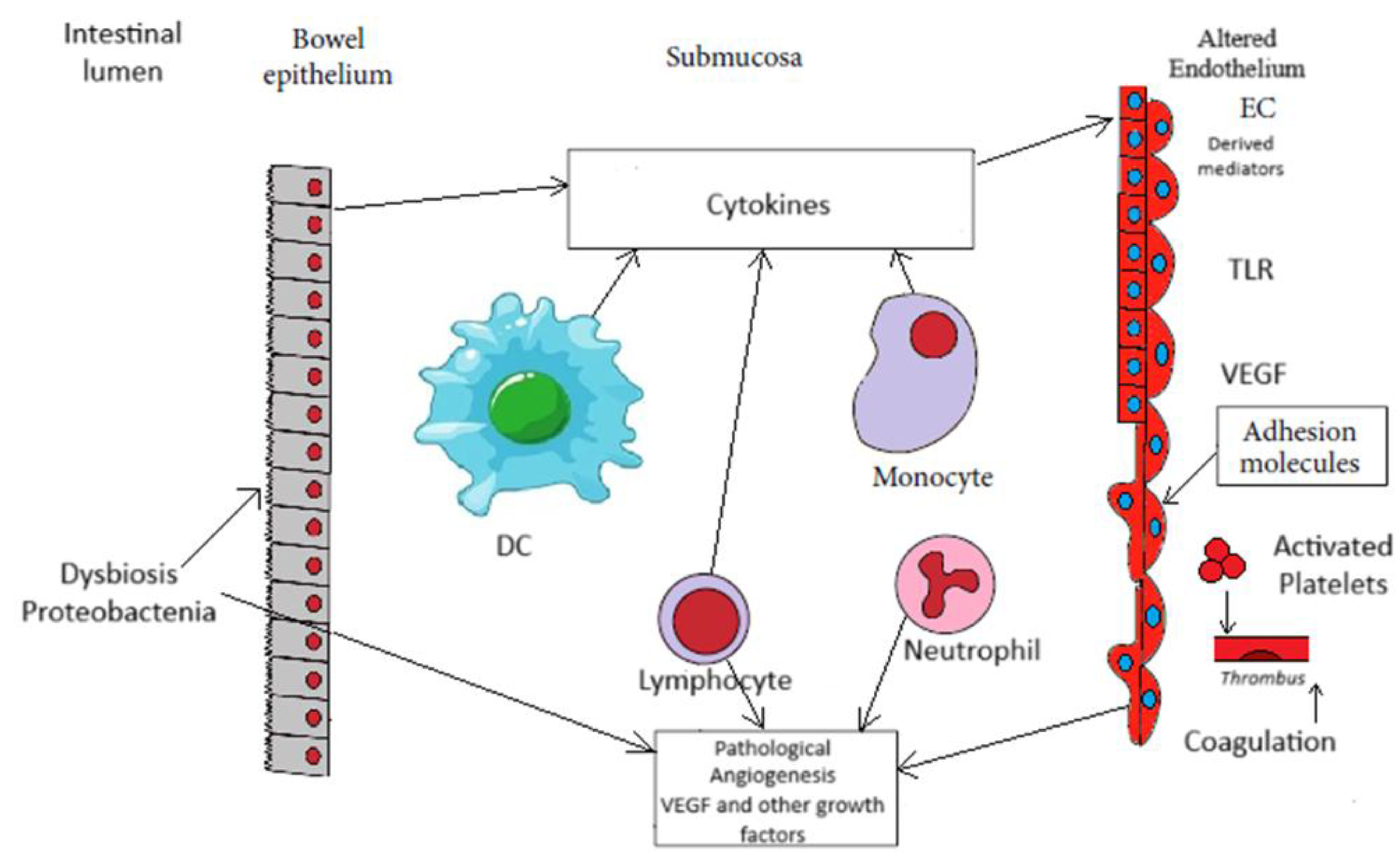

| ■ Dysbiosis ■ Endothelial activation ■ Intestinal barrier dysfunction ■ Active inflammation ■ Hypercoagulability ■ Thrombi formation ■ Ischemia |

| Endothelial activation and expression of adhesion molecules | leucocyte recruitment platelet adhesion inflammation |

|---|---|

| VEGF expression | ECs proliferation and migration up-regulation of adhesion molecules immune cells recruitment vascular permeability sprouting of angiogenesis |

| b FGF expression | sprouting of angiogenesis |

| PDGF expression | sprouting of angiogenesis vascular coverage |

| Toll – like receptor expression by EC | regulation of endothelial barrier homeostasis specific receptor for bacterial products |

| Coagulation activation | platelet adhesion and activation impaired of protein C pathway thrombi formation ischemia |

| Microvascular dysfunction | granulomatous vasculitis ulceration |

| Angiogenesis | neovascularization remodeling of vasculature initiation /promotion of inflammation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).