Submitted:

09 October 2025

Posted:

10 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- i)

- to conduct a comprehensive chemical characterization of hydrochar derived from chicken manure (CM), emphasizing the assessment of organic C and N forms by solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, alongside with the quantification of macro- and micronutrient as well as HM contents;

- ii)

- to analyze the losses and recovery rates of different nutritive elements during the HTC process, calculated by taking the product of the hydrochar mass yield and the content of the analyzed element in the hydrochar, and normalizing it by the element’s content in the feedstock; and,

- iii)

- to evaluate the resultant hydrochar in pot experiments for both its phytotoxicity and its potential as a fertilizer on three different economically and agronomically important plant species: lettuce, sunflower, and tomato.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Feedstock

2.2. Production of Hydrochar

2.3. Characterization of the Chicken Manure Utilized and the Produced Hydrochar

2.3.1. Chemical Composition

2.3.2. Solid-State 13C and 15N Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

2.4. Plant Experiment Conditions and Measurements

- -

- An estimate of the germinability: Germination percentage (G);

- -

- Mean Germination Time (MGT) corresponding to the time required for seeds to germinate or emerge;

- -

- Mean Germination Rate (MGR) representing the speed at which seeds germinate;

- -

- The time required for 50% of the seeds to germinate (T50);

- -

- Synchronization index (Z) describing the uniformity or synchronization in the timing of seed germination;

- -

- The uncertainty of the germination process (U) reflecting the degree of uncertainty associated with the distribution of the relative frequency of germination.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mass Yield and Ash Content

3.2. Physical and Chemical Parameters of Chicken Manure and Hydrochar

3.3. Modifications in the Elemental and Nutrient Composition During HTC

3.3.1. Elemental and Isotopic Composition

3.3.2. Macronutrient and Micronutrient Analysis

3.3.3. Other Metals and Heavy Metals Analysis

3.4. Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy

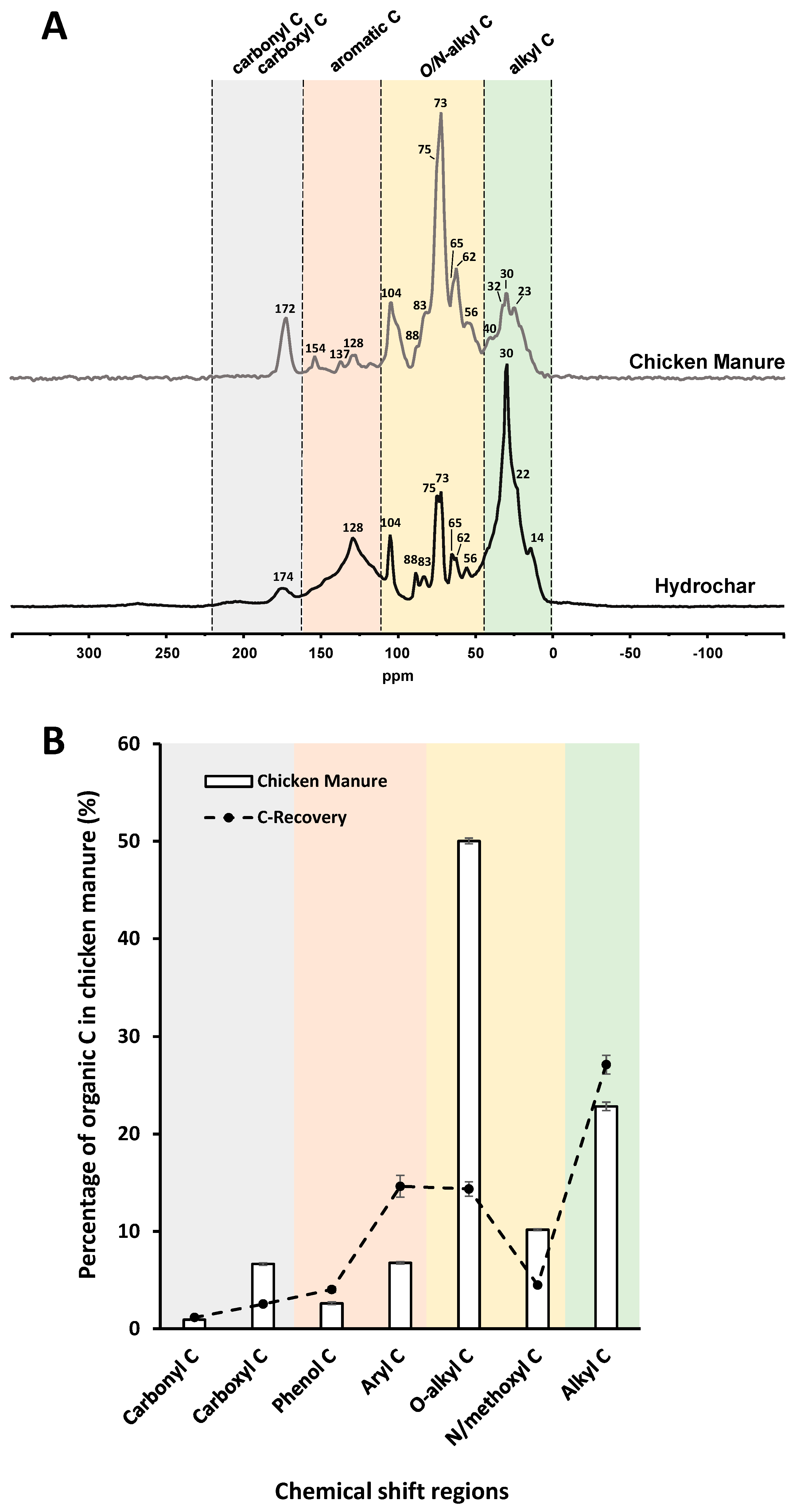

3.4.1. Solid-State 13C NMR Spectroscopy

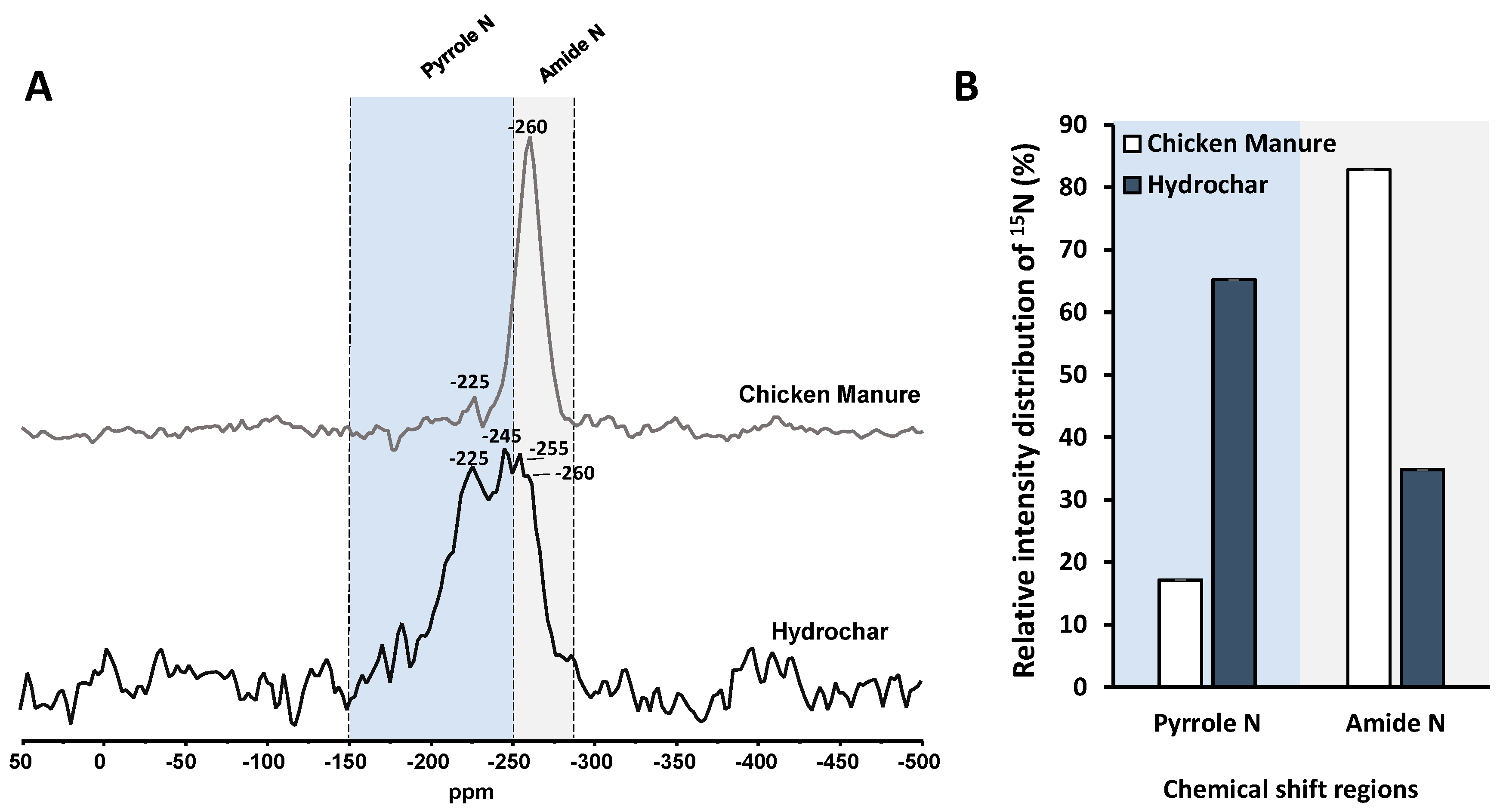

3.4.2. Solid-State 15N NMR Spectroscopy

3.5. Assessment of Phytotoxicity and Fertilizing Potential

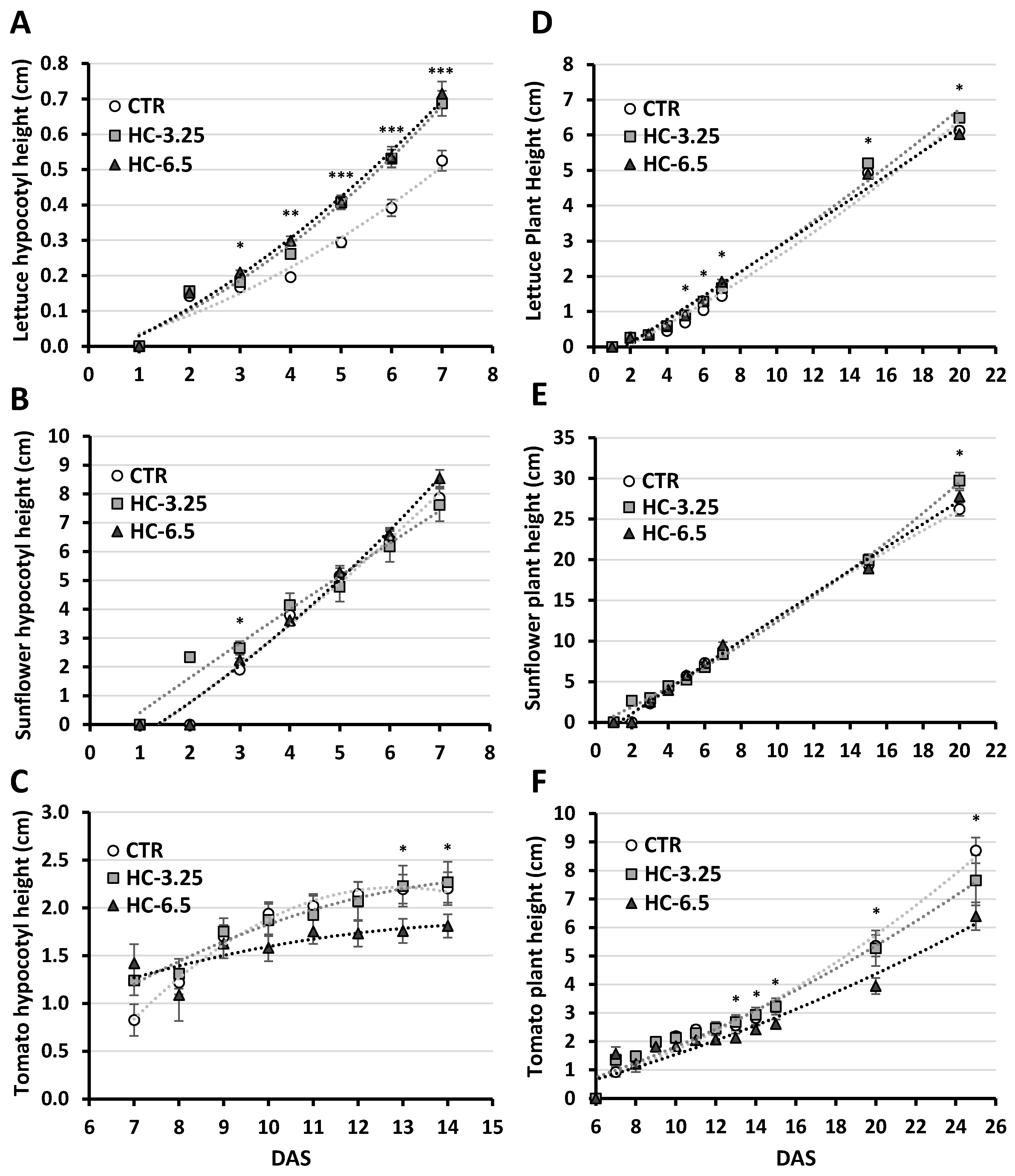

3.5.1. Germination and Seedling Growth

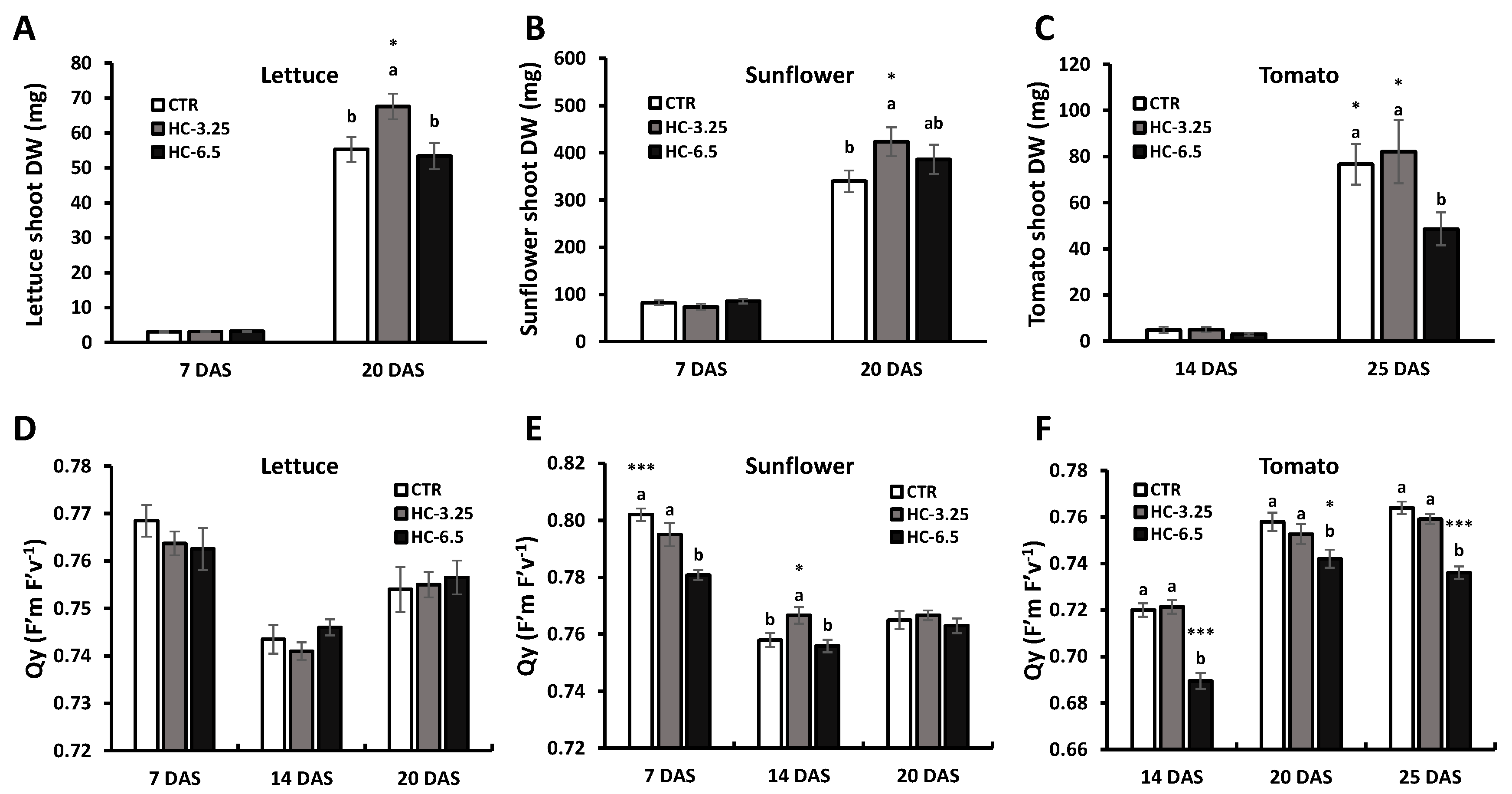

3.5.2. Biomass and Efficiency of Photosystem II

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CM Corg |

Chicken Manure Organic carbon |

| CP-MAS | Cross-Polarization Magic Angle Spinning |

| DAS | Days After Sowing |

| DM | Dry Matter |

| DOC | Dissolved Organic Carbon |

| DON | Dissolved Organic Nitrogen |

| DW | Dry Weight |

| EC | Electric Conductivity |

| G | Germination percentage |

| HF | Hydrofluoric acid |

| HM | Heavy Metal |

| HSD | Honestly Significant Difference |

| HTC IC |

Hydrothermal Carbonization Inorganic Carbon |

| ICP-OES | Inductively Coupled Plasma-Optical Emission Spectroscopy |

| IRMS | Isotopic Ratio Mass Spectrometer |

| MGR | Mean Germination Rate |

| MGT | Mean Germination Time |

| Ni | Inorganic Nitrogen |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| PSII | Photosystem II |

| QY | Quantum Yield |

| QYPSII | Quantum Yield of Photosystem II |

| SE | Standard Error |

| T50 | Time required for 50% of the seeds to germinate |

| U | Uncertainty of the germination process |

| VI | Vigour Index |

| VPDB | Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite |

| WHC | Water Holding Capacity |

| Z | Synchronization index |

References

- Fu, H.; Wang, B.; Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Xie, H.; Han, L.; Wang, N.; Sun, X.; Feng, Y.; Xue, L. Assessment of livestock manure-derived hydrochar as cleaner products: Insights into basic properties, nutrient composition, and heavy metal content. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Yu, J.; Ohtake, H.; Zhang, T. The potential for livestock manure valorization and phosphorus recovery by hydrothermal technology-a critical review. Mater Sci Energy Technol. 2023, 6, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libra, J.A.; Ro, K.S.; Kammann, C.; Funke, A.; Berge, N.D.; Neubauer, Y.; Titirici, M.M.; Fühner, C.; Bens, O.; Kern, J.; Emmerich, K.H. Hydrothermal carbonization of biomass residuals: a comparative review of the chemistry, processes and applications of wet and dry pyrolysis. Biofuels. 2011, 2(1), 71–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fertilizers Europe, 2024. Forecast of food, farming & fertilizer use in the European Union 2024-2034. https://www.fertilizerseurope.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Forecast-2024-34-web.pdf. 20 August.

- Vingerhoets, R.; Spiller, M.; Schoumans, O.; Vlaeminck, S.E.; Buysse, J.; Meers, E. Economic potential for nutrient recovery from manure in the European union. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 2025. 215, 108079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, S.; Gholizadeh, M.; Hu, X.; Yuan, X.; Sarkar, B.; Vithanage, M.; Mašek, O.; Ok, Y.S. Co-hydrothermal carbonization of swine and chicken manure: Influence of cross-interaction on hydrochar and liquid characteristics. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 786, 147381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yao, S.; Wang, Y.; Lu, H.; Brar, S.K.; Yang, S. Bio-and hydrochars from rice straw and pig manure: inter-comparison. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 235, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavali, M.; Junior, N.L.; de Sena, J.D.; Woiciechowski, A.L.; Soccol, C.R.; Belli Filho, P.; Bayard, R.; Benbelkacem, H.; de Castilhos Junior, A.B. A review on hydrothermal carbonization of potential biomass wastes, characterization and environmental applications of hydrochar, and biorefinery perspectives of the process. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paneque, M.; Knicker, H.; Kern, J.; De la Rosa, J.M. Hydrothermal carbonization and pyrolysis of sewage sludge: Effects on Lolium perenne Germination and Growth. Agronomy. 2019, 9(7), 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, M.T.; Freitas, A.; Yang, X.; Hiibel, S.; Lin, H.; Coronella, C.J. Hydrothermal Carbonization (HTC) of Cow Manure: Carbon and Nitrogen Distributions in HTC Products. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2016, 35, 1002–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, Q. Effects of process parameters on the distribution characteristics of inorganic nutrients from hydrothermal carbonization of cattle manure. J. Environ. Manage. 2018, 209, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Wang, F.; Zhai, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Peng, C.; Wang, T.; Li, C.; Zeng, G. Effect of sewage sludge hydrochar on soil properties and Cd immobilization in a contaminated soil. Chemosphere. 2017, 189, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jager, M.; Giani, L. An investigation of the effects of hydrochar application rate on soil amelioration and plant growth in three diverse soils. Biochar. 2021, 3(3), 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luutu, H.; Rose, M.T.; McIntosh, S.; Van Zwieten, L.; Weng, H.H.; Pocock, M.; Rose, T.J. Phytotoxicity induced by soil-applied hydrothermally-carbonised waste amendments: effect of reaction temperature, feedstock and soil nutrition. Plant Soil. 2023, 493(1), 647–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, E.; Tobajas, M.; Mohedano, A.F.; Reguera, M.; Esteban, E.; de la Rubia, A. Effect of garden and park waste hydrochar and biochar in soil application: a comparative study. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023, 13(18), 16479–16493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, M.T.; Lynam, J.G.; Uddin, M.H.; Coronella, C.J. Hydrothermal carbonization: Fate of inorganics. Biomass Bioenerg. 2013, 49, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhnidi, M.J.; Wüst, D.; Funke, A.; Hang, L.; Kruse, A. Fate of nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium during hydrothermal carbonization and the potential for nutrient recovery. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2020, 8(41), 15507–15516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzediegwu, C.; Naeth, M.A.; Chang, S.X. Carbonization temperature and feedstock type interactively affect chemical, fuel, and surface properties of hydrochars. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 330, 124976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heilmann, S.M.; Molde, J.S.; Timler, J.G.; Wood, B.M.; Mikula, A.L.; Vozhdayev, G.V.; Colosky, E.C.; Spokas, K.A.; Valentas, K.J. Phosphorus reclamation through hydrothermal carbonization of animal manures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48(17), 10323–10329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Tan, F.; Wu, B.; He, M.; Wang, W.; Tang, X.; Hu, O.; Zhang, M. Immobilization of phosphorus in cow manure during hydrothermal carbonization. J. Environ. Manage. 2015, 157, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.X.; Fang, C.; Zhang, B.; Tang, Y.Z. Transformations of phosphorus speciation during (hydro)thermal treatments of animal manures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 3016–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paneque, M.; de la Rosa, J.M.; Patti, A.F.; Knicker, H. Changes in the bio-availability of phosphorus in pyrochars and hydrochars derived from sewage sludge after their amendment to soils. Agronomy. 2021, 11(4), 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Ro, K.S.; Chappell, M.; Li, Y.; Mao, J. Chemical structures of swine-manure chars produced under different carbonization conditions investigated by advanced solid-state 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Energy Fuels. 2011, 25(1), 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paneque, M.; De la Rosa, J.M.; Kern, J.; Reza, M.T.; Knicker, H. Hydrothermal carbonization and pyrolysis of sewage sludges: What happen to carbon and nitrogen? J Anal Appl Pyrol. 2017, 128, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veihmeyer, F.J.; Hendrickson, A.H. Methods of measuring field capacity and wilting percentages of soils. Soil Sci. 1949, 68, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeney, D.R.; Nelson, D.W. forms. In Methods of Soil Analysis Part 2; Bottomley, P.J., Angle, J.S., Weaver, R.W., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1982; pp. 643–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greweling, T.; Peech, M.L. Chemical Soil Test; Agriculture Experiment Station, Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1960; p. 960. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, S.R.; Cole, C.V.; Watanabe, F.S. Estimation of Available Phosphorus in Soils by Extraction with Sodium Bicarbonate; Circular (United States. Department of Agriculture); U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Helmke, P.A.; Sparks, D.L. cesium. In Methods of Soil Analysis Part 3: Chemical Methods; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; SSSA Book Series No 5; SSSA: Madison, WI, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, C.N.; Dalmolin, R.S.; Dick, D.P.; Knicker, H.; Klamt, E.; Kögel-Knabner, I. The effect of 10% HF treatment on the resolution of CPMAS 13C NMR spectra and on the quality of organic matter in Ferralsols. Geoderma 2003, 116, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knicker, H.; Totsche, K.U.; Almendros, G.; González-Vila, F.J. Condensation degree of burnt peat and plant residues and the reliability of solid-state VACP MAS 13C NMR spectra obtained from pyrogenic humic material. Org. Geochem. 2005, 36, 1359–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranal, M.A.; Santana, D.G. How and why to measure the germination process? Braz J Bot. 2006, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranal, M.A.; Santana, D.G.; Ferreira, W.R.; Mendes-Rodrigues, C. Calculating germination measurements and organizing spreadsheets. Braz J Bot. 2009, 32, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekpo, U.; Ross, A.B.; Camargo-Valero, M.A.; Williams, P.T. A comparison of product yields and inorganic content in process streams following thermal hydrolysis and hydrothermal processing of microalgae, manure and digestate. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 200, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejna, M.; Świechowski, K.; Rasaq, W.A.; Białowiec, A. Study on the Effect of Hydrothermal Carbonization Parameters on Fuel Properties of Chicken Manure Hydrochar. Materials. 2022, 15(16), 5564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funke, A.; Ziegler, F. Hydrothermal carbonization of biomass: a summary and discussion of chemical mechanisms for process engineering. Biofuel Bioprod. Biorefin. 2010, 4(2), 160–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, V.; Jung, D.; Zimmermann, J.; Rodriguez Correa, C.; Elleuch, A.; Halouani, K.; Kruse, A. Conductive carbon materials from the hydrothermal carbonization of vineyard residues for the application in electrochemical double-layer capacitors (EDLCs) and direct carbon fuel cells (DCFCs). Materials. 2019, 12(10), 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargmann, I.; Martens, R.; Rillig, M.C.; Kruse, A.; Kücke, M. Hydrochar amendment promotes microbial immobilization of mineral nitrogen. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2014, 177(1), 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiz, G.; Wynn, J.G.; Wurster, C.M.; Goodrick, I.; Nelson, P.N.; Bird, M.I. Pyrogenic carbon from tropical savanna burning: production and stable isotope composition. Biogeosciences Discussions. 2015, 11(10), 15149–15183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, I.; Braadbaart, F.; Boon, J.J.; van Bergen, P.F. Stable carbon isotope changes during artificial charring of propagules. Org. Geochem. 2002, 33(12), 1675–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabio, E.; Álvarez-Murillo, A.; Román, S.; Ledesma, B. Conversion of tomato-peel waste into solid fuel by hydrothermal carbonization: Influence of the processing variables. Waste Manag. 2016, 47, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, M.T.; Poulson, S.R.; Roman, S.; Coronella, C.J. Behavior of stable carbon and stable nitrogen isotopes during hydrothermal carbonization of biomass. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2018, 131, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mau, V.; Quance, J.; Posmanik, R.; Gross, A. Phases’ characteristics of poultry litter hydrothermal carbonization under a range of process parameters. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 219, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Parliament, European Council Regulation (EU) 2019/1009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 laying down rules on the making available on the market of EU fertilizing products and amending Regulations (EC) No 1069/2009 and (EC) No 1107/2009 and repealing Regulation (EC) No 2003/2003. http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/1009/2023-03-16. (Accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Schnitzer, M.I.; Monreal, C.M.; Facey, G.A.; Fransham, P.B. The conversion of chicken manure to biooil by fast pyrolysis I. Analyses of chicken manure, biooils and char by 13C and 1H NMR and FTIR spectrophotometry. J. Environ. Sci. Health. Part B Pestic. Food Contam. Agric. Wastes 2007, 42, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimò, G.; Kucerik, J.; Berns, A.E.; Schaumann, G.E.; Alonzo, G.; Conte, P. Effect of heating time and temperature on the chemical characteristics of biochar from poultry manure. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62(8), 1912–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Burns, I.G.; Turner, M.K. Derivation of a dynamic model of the kinetics of nitrogen uptake throughout the growth of lettuce: calibration and validation. J. Plant Nutr. 2008, 31(8), 1440–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shen, F.; Guo, H.; Wang, Z.; Yang, G.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Deng, S. Phytotoxicity assessment on corn stover biochar, derived from fast pyrolysis, based on seed germination, early growth, and potential plant cell damage. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2015, 22, 9534–9543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Limon, M.S.H.; Romić, M.; Islam, M.A. Hydrochar-based soil amendments for agriculture: a review of recent progress. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baronti, S.; Alberti, G.; Camin, F.; Criscuoli, I.; Genesio, L.; Mass, R.; Vaccari, F.P.; Ziller, L.; Miglietta, F. Hydrochar enhances growth of poplar for bioenergy while marginally contributing to direct soil carbon sequestration. GCB Bioenergy. 2017, 9(11), 1618–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Rosa, J.M.; Knicker, H. Bioavailability of N released from N-rich pyrogenic organic matter: an incubation study. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43(12), 2368–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paneque, M.; José, M.; Franco-Navarro, J.D.; Colmenero-Flores, J.M.; Knicker, H. Effect of biochar amendment on morphology, productivity and water relations of sunflower plants under non-irrigation conditions. Catena. 2016, 147, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Elemental composition | ||||||||||

| Mass yield | Ash content | Corg | N | Oa | H | |||||

| % DMa | g kg-1 | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |||||

| CM | - | 850 ± 9 | 7.70 ± 0.19 a | 2.35 ± 0.18 a | 3.52 ± 1.02 a | 1.04 ± 0.25 | ||||

| Hydrochar | 89.6 | 916 ± 2 | 5.86 ± 0.74 b | 0.47 ± 0.05 b | 1.38 ± 0.21 b | 0.61 ± 0.15 | ||||

| P-value | *** | *** | * | ns | ||||||

|

Recovery (% DM) |

96.0 | 68.3 ± 1.69 | 17.8 ± 1.97 | 49.9 ± 2.59 | 63.7 ± 2.52 | |||||

| Corg/N | NO3--N | NH4+-N | Ni of the total N | ||||

| (w/w) | g kg-1 | g kg-1 | % | ||||

| CM | 3.36 ± 0.08 b | 0.38 ± 0.02 a | 0.17 ± 0.00 a | 2.34 ± 0.18 | |||

| Hydrochar | 13.0 ± 0.75 a | 0.08 ± 0.02 b | 0.05 ± 0.01 b | 2.78 ± 0.31 | |||

| P-value | *** | *** | *** | ns | |||

| Recovery (% DM) | - | 19.4 ± 3.90 | 23.5 ± 3.07 | 106 ± 15.5 | |||

| Element (g kg-1) | Chicken Manure | Hydrochar | P-value | Recovery (% DM) |

| P | 2.75 ± 0.10 a | 1.04 ± 0.02 b | *** | 34.0 ± 0.62 |

| Extr-P | 0.59 ± 0.01 a | 0.02 ± 0.00 b | *** | 2.55 ± 0.07 |

| K | 4.59 ± 0.18 a | 0.60 ± 0.02 b | *** | 11.7 ± 0.33 |

| Extr-K | 4.60 ± 0.12 a | 0.25 ± 0.01 b | *** | 4.95 ± 0.12 |

| S | 1.33 ± 0.05 a | 0.24 ± 0.01 b | *** | 16.1 ± 0.32 |

| Extr-S | 0.49 ± 0.01 a | 0.04 ± 0.00 b | *** | 7.28 ± 0.06 |

| Ca | 40.3 ± 1.31 a | 32.1 ± 1.09 b | *** | 71.5 ± 2.42 |

| Mg | 1.84 ± 0.04 a | 0.92 ± 0.02 b | *** | 44.8 ± 0.94 |

| Element (mg kg-1) | Chicken Manure | Hydrochar | P-value | Recovery (% DM) |

| Fe | 6889 ± 263 a | 4206 ± 76.3 b | *** | 54.7 ± 0.99 |

| Cu | 66.0 ± 1.88 a | 31.5 ± 3.16 b | *** | 42.7 ± 4.28 |

| B | 10.0 ± 0.28 a | 2.35 ± 0.11 b | *** | 20.9 ± 0.99 |

| Mn | 137 ± 4.36 a | 60.7 ± 0.58 b | *** | 39.6 ± 0.38 |

| Zn | 184 ± 5.93 a | 72.9 ± 2.04 b | *** | 35.5 ± 1.01 |

| Element (mg kg-1) | Chicken Manure | Hydrochar | P-value | Recovery (% DM) |

| Na | 1208 ± 31.3 a | 231.4 ± 4.49 b | *** | 17.2 ± 0.33 |

| Al | 6031 ± 114 a | 3425 ± 42.9 b | *** | 50.9 ± 0.64 |

| Ba | 26.3 ± 0.78 a | 10.0 ± 0.17 b | *** | 34.1 ± 0.59 |

| Li | 4.95 ± 0.23 a | 2.82 ± 0.07 b | *** | 51.0 ± 1.19 |

| Sr | 26.3 ± 0.58 a | 15.1 ± 0.43 b | *** | 51.3 ± 1.47 |

| As | 3.42 ± 1.14 a | 1.11 ± 0.57 a | ns | 29.0 ± 14.9 |

| Cd | 0.14 ± 0.04 a | 0.20 ± 0.03 a | ns | 129 ± 19.4 |

| Co | 1.69 ± 0.13 a | 0.96 ± 0.06 b | ** | 50.8 ± 3.31 |

| Cr | 22.0 ± 0.76 a | 15.4 ± 0.26 b | *** | 62.6 ± 1.06 |

| Hg | 1.19 ± 0.29 a | 0.87 ± 0.27 a | ns | 65.4 ± 20.1 |

| Ni | 7.22 ± 0.32 a | 3.87 ± 0.07 b | *** | 48.0 ± 0.93 |

| Mo | 1.39 ± 0.05 a | 0.81 ± 0.09 b | ** | 51.8 ± 5.86 |

| Pb | 11.9 ± 0.60 a | 6.63 ± 0.38 b | ** | 50.0 ± 2.88 |

| V | 13.9 ± 0.49 a | 8.16 ± 0.18 b | *** | 52.7 ± 1.14 |

| Treatments | G (%) | MGT (days) | MGR (day-1) | T50 (days) | Z (unit less) | U (bit) | VI | |

| Lettuce | CTR | 87.5 ± 3.95 | 2.81 ± 0.15 | 0.36 ± 0.02 | 2.07 ± 0.17 | 0.42 ± 0.09 | 1.21 ± 0.21 | 46.1 ± 2.44 b |

| HC-3.25 | 85.0 ± 2.50 | 2.66 ± 0.21 | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 1.70 ± 0.06 | 0.56 ± 0.11 | 0.91 ± 0.24 | 58.4 ± 2.58 a | |

| HC-6.5 | 85.0 ± 2.50 | 2.72 ± 0.19 | 0.37 ± 0.03 | 1.98 ± 0.16 | 0.43 ± 0.04 | 1.14 ± 0.11 | 60.8 ± 4.00 a | |

| P-value | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | * | |

| Sunflower | CTR | 77.5 ± 2.50 | 3.57 ± 0.17 b | 0.28 ± 0.01 a | 3.02 ± 0.18 b | 0.51 ± 0.13 a | 1.21 ± 0.10 b | 609 ± 27.6 ab |

| HC-3.25 | 69.3 ± 6.27 | 4.51 ± 0.24 a | 0.22 ± 0.01 b | 3.97 ± 0.30 a | 0.12 ± 0.05 b | 1.93 ± 0.15 a | 540 ± 44.9 b | |

| HC-6.5 | 77.5 ± 4.68 | 3.84 ± 0.19 b | 0.26 ± 0.01 ab | 2.83 ± 0.11 b | 0.43 ± 0.08 a | 1.14 ± 0.17 b | 671 ± 25.5 a | |

| P-value | ns | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Tomato | CTR | 83.3 ± 0.00 a | 9.52 ± 0.56 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 8.50 ± 0.89 | 0.26 ± 0.07 a | 1.48 ± 0.22 | 185 ± 14.8 a |

| HC-3.25 | 86.7 ± 6.24 a | 9.64 ± 0.89 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 8.98 ± 1.22 | 0.33 ± 0.09 a | 1.35 ± 0.26 | 187 ± 15.8 a | |

| HC-6.5 | 70.0 ± 3.33 b | 10.4 ± 0.52 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | 9.90 ± 0.58 | 0.03 ± 0.03 b | 1.96 ± 0.13 | 116 ± 8.80 b | |

| P-value | * | ns | ns | ns | * | ns | * | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).