Submitted:

09 October 2025

Posted:

10 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

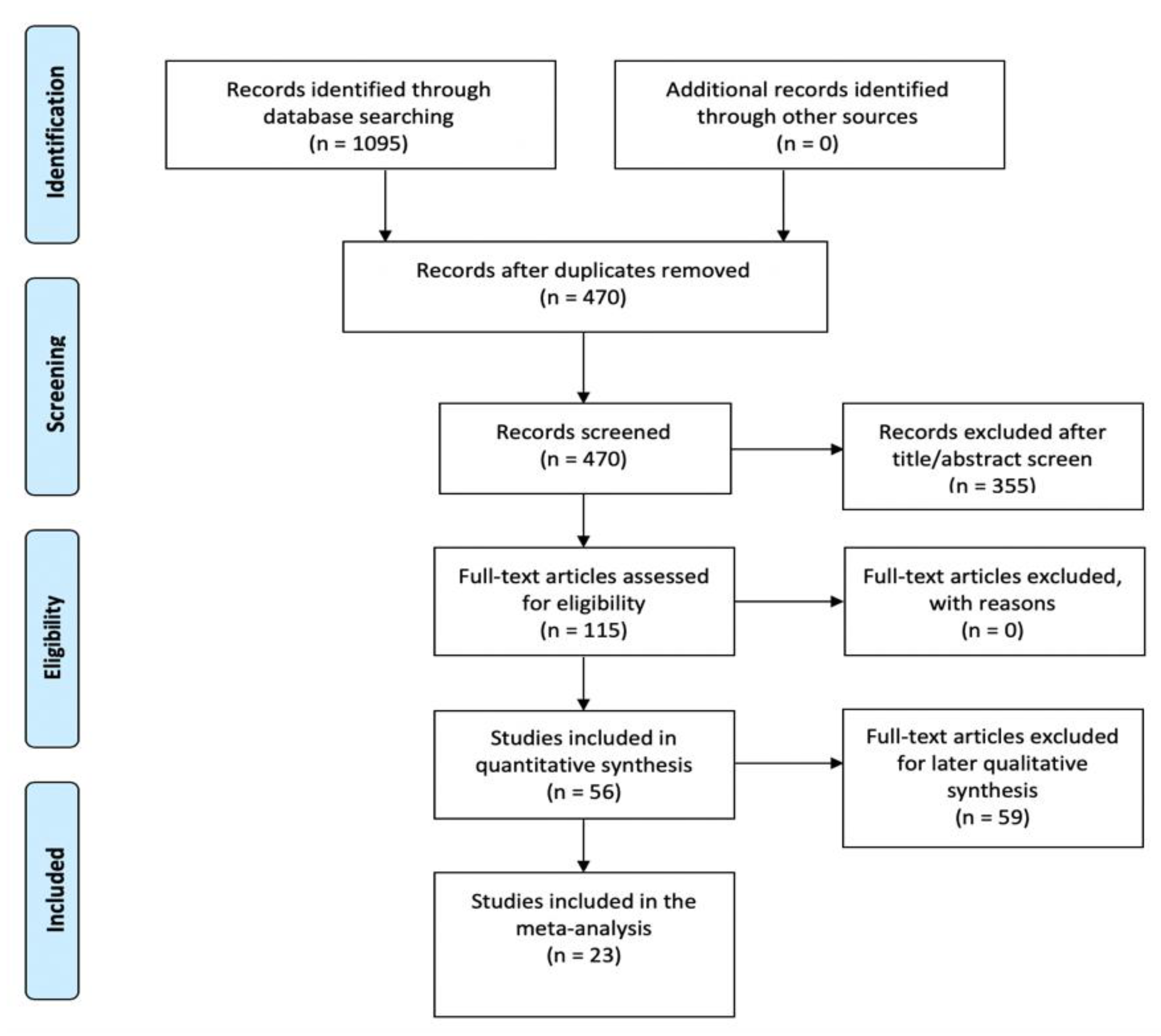

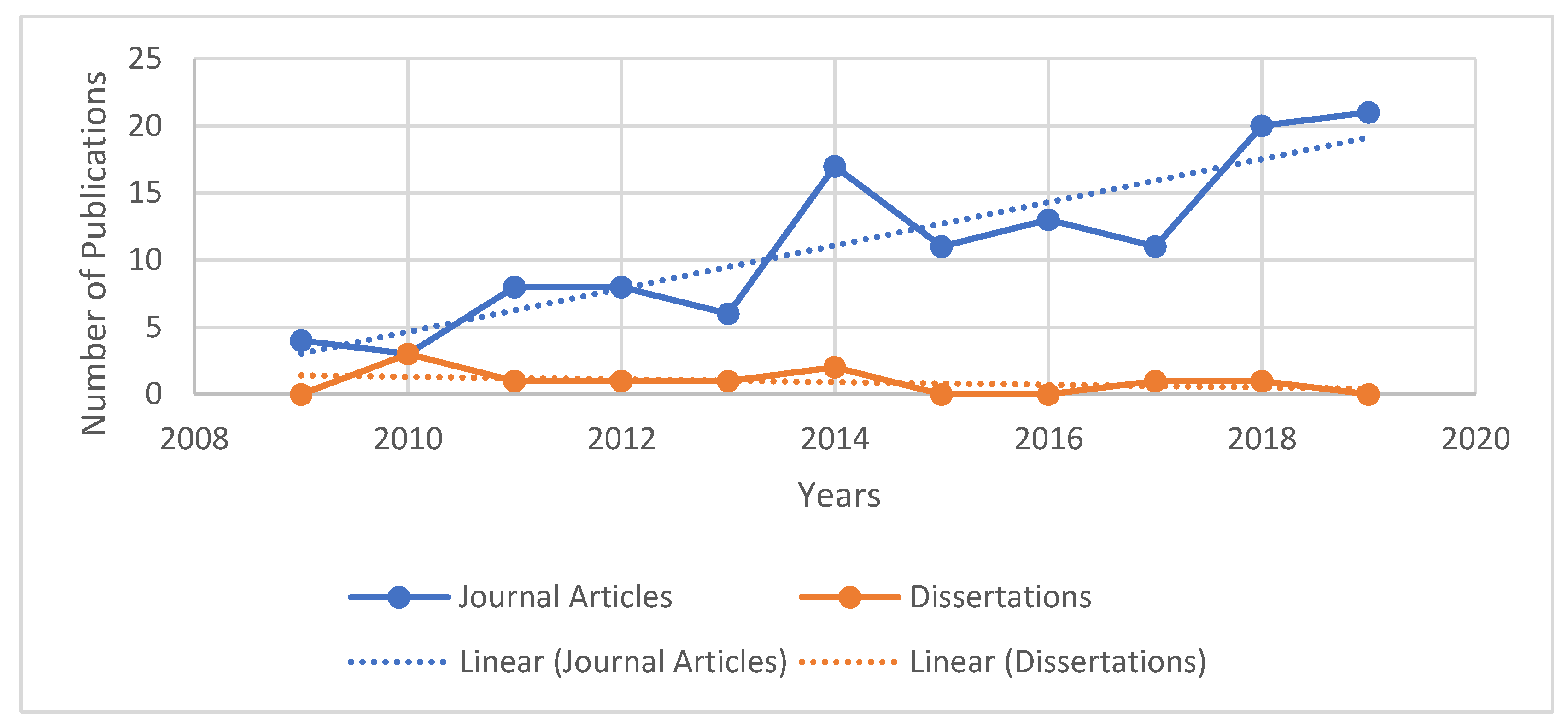

Methods

Study Selection

Eligibility Criteria

Coding

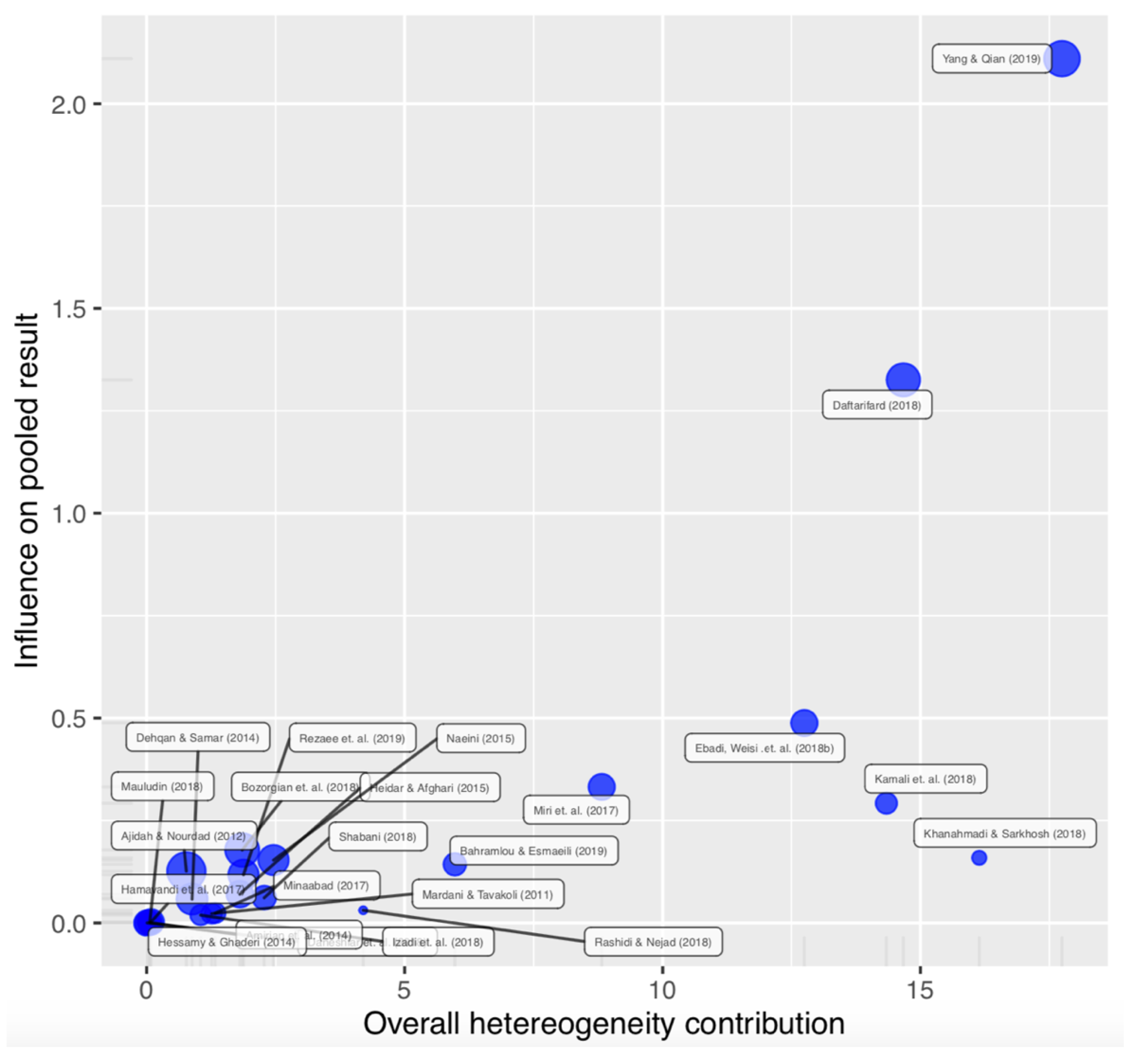

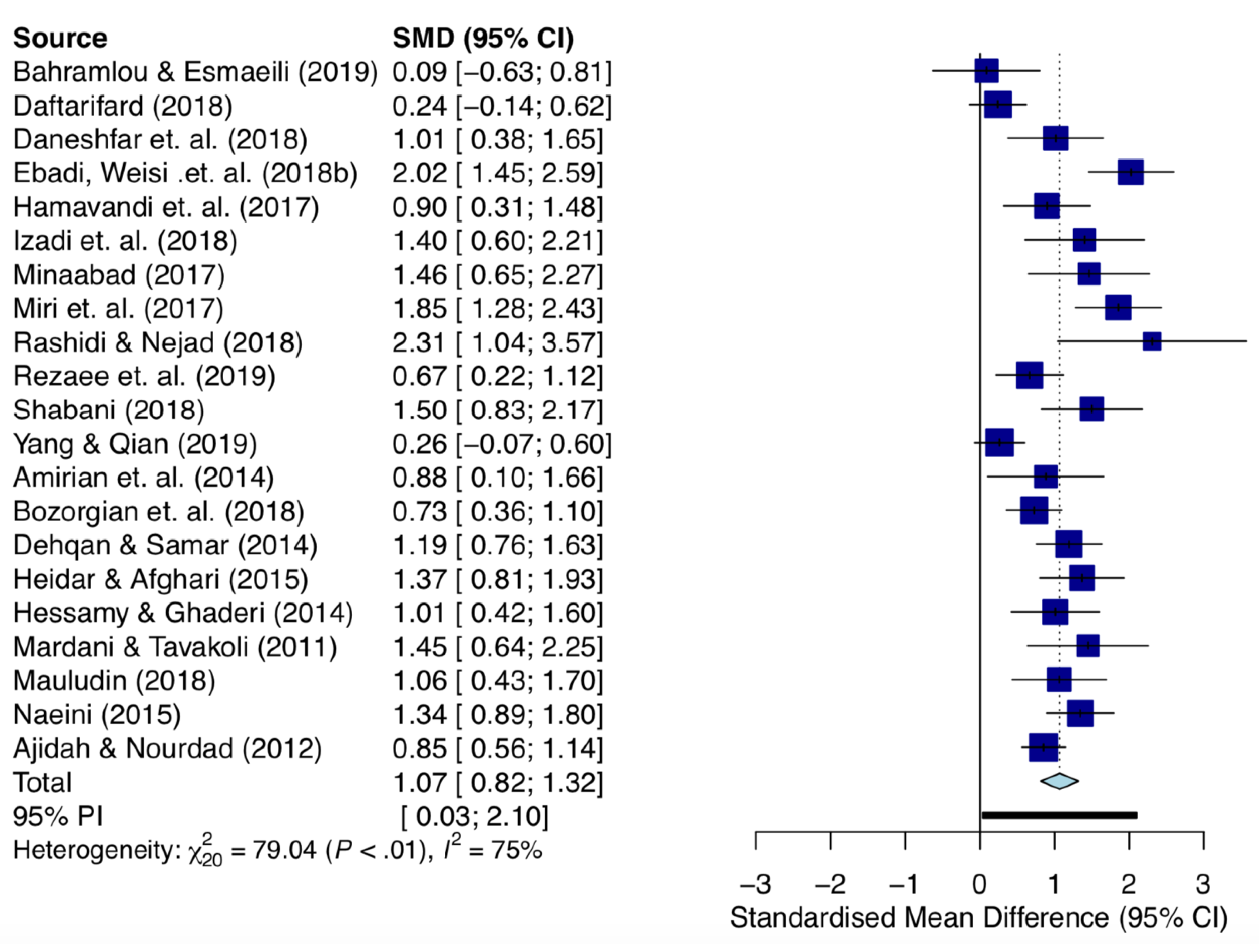

Meta-Analytic Techniques

Findings

Discussion

Limitations

Future Directions

Conclusions & Recommendations

References

- Ableeva, R. (2010). Dynamic assessment of listening comprehension in second language learning (Ph.D., The Pennsylvania State University). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/pqdtglobal/docview/816855305/abstract/EFD10DAB16AD46B5PQ/2.

- Ableeva, R., & Lantolf, J. (2011). Mediated dialogue and the microgenesis of second language listening comprehension. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 18(2), 133–149. [CrossRef]

- Aghaebrahimian, A., Rahimirad, M., Ahmadi, A., & Alamdari, J. K. (2014). Dynamic Assessment of Writing Skill in Advanced EFL Iranian Learners. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 98, 60–67. [CrossRef]

- Ajideh, P., & Nourdad, N. (2012). The Immediate and Delayed Effect of Dynamic Assessment on EFL Reading Ability. English Language Teaching, 5(12), 141–151. [CrossRef]

- Alavi, S. M., & Taghizadeh, M. (2014). Dynamic Assessment of Writing: The Impact of Implicit/Explicit Mediations on L2 Learners’ Internalization of Writing Skills and Strategies. Educational Assessment, 19(1), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Amirian, M. R., Davoudi, M., & Ramazanian, M. (2014). The Effect of Dynamic Assessment on Iranian EFL Learners’ Reading Comprehension. Advances in Language and Literary Studies; Footscray, 5(3), 191–194. [CrossRef]

- Bahramlou, K., & Esmaeili, A. (2019). The Effects of Vocabulary Enhancement Exercises and Group Dynamic Assessment on Word Learning Through Lexical Inferencing. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 48(4), 889–901. [CrossRef]

- Bakhoda, I., & Shabani, K. (2019). Enhancing L2 learners’ ZPD modification through computerized-group dynamic assessment of reading comprehension. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 13(1), 31–44. [CrossRef]

- Barabadi, E., Khajavy, G. H., & Kamrood, A. M. (2018). Applying Interventionist and Interactionist Approaches to Dynamic Assessment for L2 Listening Comprehension. International Journal of Instruction, 11(3), 681–700. [CrossRef]

- Bozorgian, H., & Fakhri Alamdari, E. (2018). Multimedia listening comprehension: Metacognitive instruction or metacognitive instruction through dialogic interaction. ReCALL : The Journal of EUROCALL; Cambridge, 30(1), 131–152. http://dx.doi.org.mutex.gmu.edu/10.1017/S0958344016000240. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. (2019). Developing Students’ Critical Thinking and Discourse Level Writing Skill Through Teachers’ Questions: A Sociocultural Approach. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics, 42(2), 141–162. [CrossRef]

- Daftarifard, P. (2018). The effect of mediational artifacts on EFL learners’ reading comprehension performance. International Journal of Language Studies, 12(3), 73–90.

- Daneshfar, S., Aliasin, S. H., & Hashemi, A. (2018). The Effect of Dynamic Assessment on Grammar Achievement of Iranian Third Grade Secondary School EFL Learners. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 8(3), 295–305. http://dx.doi.org.mutex.gmu.edu/10.17507/tpls.0803.04. [CrossRef]

- Dehqan, M., & Samar, R. G. (2014). Reading Comprehension in a Sociocultural Context: Effect on Learners of Two Proficiency Levels. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 98, 404–410. [CrossRef]

- Dynamic Assessment of Incidental Vocabularies: A Case of Iranian ESP Learners. (2016). Advances in Language and Literary Studies, 7(2). [CrossRef]

- Ebadi, S., & Rahimi, M. (2019). Mediating EFL learners’ academic writing skills in online dynamic assessment using Google Docs. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 32(5–6), 527–555. [CrossRef]

- Ebadi, S., Asakereh, A., & Link to external site, this link will open in a new window. (2017). Developing EFL Learners’ Speaking Skills through Dynamic Assessment: A Case of A Beginner and an Advanced Learner. Cogent Education, 4(1), 18. http://dx.doi.org.mutex.gmu.edu/10.1080/2331186X.2017.1419796. [CrossRef]

- Ebadi, S., Link to external site, this link will open in a new window, Vakilifard, A., Bahramlou, K., & Link to external site, this link will open in a new window. (2018). Learning Persian vocabulary through reading: The effects of noticing and computerized dynamic assessment. Cogent Education; Abingdon, 5(1). http://dx.doi.org.mutex.gmu.edu/10.1080/2331186X.2018.1507176. [CrossRef]

- Ebadi, S., Weisi, H., Monkaresi, H., & Bahramlou, K. (2018). Exploring lexical inferencing as a vocabulary acquisition strategy through computerized dynamic assessment and static assessment. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 31(7), 790–817. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, E. (2015). The effect of dynamic assessment on complexity, accuracy, and fluency in EFL learners’ oral production. International Journal of Research Studies in Language Learning, 4(3). [CrossRef]

- Elola, I., & Oskoz, A. (2016). Supporting Second Language Writing Using Multimodal Feedback. Foreign Language Annals; Alexandria, 49(1), 58–74. http://dx.doi.org.mutex.gmu.edu/10.1111/flan.12183. [CrossRef]

- Erfani, S. S., & Nikbin, S. (2015). The Effect of Peer-Assisted Mediation vs. Tutor-Intervention within Dynamic Assessment Framework on Writing Development of Iranian Intermediate EFL Learners. English Language Teaching, 8(4), 128–141. [CrossRef]

- Estaji, M., & Farahanynia, M. (2019). The Immediate and Delayed Effect of Dynamic Assessment Approaches on EFL Learners’ Oral Narrative Performance and Anxiety. Educational Assessment, 24(2), 135–154. [CrossRef]

- Farangi, M. R., & Saadi, Z. K. (2017). Dynamic assessment or schema theory: The case of listening comprehension. Cogent Education; Abingdon, 4(1). http://dx.doi.org.mutex.gmu.edu/10.1080/2331186X.2017.1312078. [CrossRef]

- Ghonsooly, B., & Hassanzadeh, T. (2019). Effect of interactionist dynamic assessment on English vocabulary learning: Cultural perspectives in focus. Issues in Educational Research, 29(1), 70–88.

- Hamavandi, M., Rezai, M. J., & Mazdayasna, G. (2017). Dynamic assessment of morphological awareness in the EFL context. Cogent Education; Abingdon, 4(1). http://dx.doi.org.mutex.gmu.edu/10.1080/2331186X.2017.1324254. [CrossRef]

- Hanifi, S., Nasiri, M., & Aliasin, H. (2016). Dynamic Assessment of Incidental Vocabularies: A Case of Iranian ESP Learners. Advances in Language and Literary Studies; Footscray, 7(2), 163–170.

- Hanjani, A. M., & Li, L. (2014). Exploring L2 writers’ collaborative revision interactions and their writing performance. System, 44, 101–114. [CrossRef]

- Hashemi Shahraki, S., Ketabi, S., & Barati, H. (2014). Group dynamic assessment of EFL listening comprehension: Conversational implicatures in focus. International Journal of Research Studies in Language Learning, 4(3). [CrossRef]

- Heidar, D. M., & Afghari, A. (2015). The Effect of Dynamic Assessment in Synchronous Computer-Mediated Communication on Iranian EFL Learners’ Listening Comprehension Ability at Upper-Intermediate Level. English Language Teaching, 8(4), 14–23. [CrossRef]

- Hessamy, G., & Ghaderi, E. (2014). The Role of Dynamic Assessment in the Vocabulary Learning of Iranian EFL Learners. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 98, 645–652. [CrossRef]

- Hidri, S. (2019). Static vs. dynamic assessment of students’ writing exams: A comparison of two assessment modes. International Multilingual Research Journal, 13(4), 239–256. [CrossRef]

- Izadi, M., Khoshsima, H., Nourmohammadi, E., & Yarahmadzehi, N. (2018). Mediational Strategies in a Dynamic Assessment Approach to L2 Listening Comprehension: Different Ability Levels in Focus 1. Italian Sociological Review; Verona, 8(3), 445–466.

- Jafary, M. R., Nordin, N., & Mohajeri, R. (2012). The Effect of Dynamic versus Static Assessment on Syntactic Development of Iranian College Preparatory EFL Learners. English Language Teaching, 5(7), 149–157. [CrossRef]

- Kamali, M., Abbasi, M., & Sadighi, F. (2018). The Effect of Dynamic Assessment on L2 Grammar Acquisition by Iranian EFL Learners. International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies, 6(1), 72–78. [CrossRef]

- Mehri Kamrood, A., Davoudi, M., Ghaniabadi, S., & Amirian, S. M. R. (2019). Diagnosing L2 learners’ development through online computerized dynamic assessment. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1-30. [CrossRef]

- Kao, Y.-T. (2014). Vygotsky’s theory of instruction and assessment: The implications on foreign language education (Ph.D., The Pennsylvania State University). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/pqdtglobal/docview/1639700013/abstract/B97860CF0EB34B8EPQ/2.

- Khanahmadi, F., & Sarkhosh, M. (2018). Teacher-vs. Peer-Mediated Learning of Grammar through Dynamic Assessment: A Sociocultural Perspective. International Journal of Instruction, 11(4), 207–222. [CrossRef]

- Khonamri, Fatameh, & Sana’ati, M. K. (2016). The Effect of Dynamic Assessment on Iranian EFL Students’ Critical Reading Performance. Kesan Penilaian Dinamik Terhadap Penguasaan Pembacaan Kritikal Pelajar EFL Iran., 41(2), 115–123.

- Khonamri, Fatemeh, & Sana’ati, M. K. (2014). The Impacts of Dynamic Assessment and CALL on Critical Reading: An Interventionist Approach. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 98, 982–989. [CrossRef]

- Kozulin, A., & Levi, T. (2018). EFL Learning Potential: General or Modular? Journal of Cognitive Education & Psychology, 17(1), 16–27. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z. (2010). Interactive Dynamic Assessment with Children Learning EFL in Kindergarten. Early Childhood Education Journal; New York, 37(4), 279–287. http://dx.doi.org.mutex.gmu.edu/10.1007/s10643-009-0356-6. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.-Y., & Hu, C.-F. (2019). Dynamic assessment of phonological awareness in young foreign language learners: Predictability and modifiability. Reading and Writing, 32(4), 891–908. [CrossRef]

- Mardani, M., & Tavakoli, M. (2011). Beyond Reading Comprehension: The Effect of Adding a Dynamic Assessment Component on EFL Reading Comprehension. Journal of Language Teaching & Research, 2(3), 688–696. [CrossRef]

- Mauludin, L. A. (2018). Dynamic assessment to improve students’ summary writing skill in an ESP class. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 36(4), 355–364. [CrossRef]

- Mawlawi Diab, N. (2016). A comparison of peer, teacher and self-feedback on the reduction of language errors in student essays. System, 57, 55–65. [CrossRef]

- Minaabad, M. S. (2017). Study of the Effect of Dynamic Assessment and Graphic Organizers on EFL Learners’ Reading Comprehension. Journal of Language Teaching & Research, 8(3), 548–555. [CrossRef]

- Miri, M., Alibakhshi, G., Kushki, A., & Bavarsad, P. S. (2017). Going beyond One-to-One Mediation in Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD): Concurrent and Cumulative Group Dynamic Assessment. Eurasian Journal of Applied Linguistics; Ankara, 3(1), 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Naeini, J. (2014). On the Study of DA and SLA: Feuerstein’s MLE and EFL Learners’ Reading Comprehension. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 98, 1297–1306. [CrossRef]

- Naeini, J. (2015). A Comparative Study of the Effects of Two Approaches of Dynamic Assessment on the Reading Comprehension of Iranian EFL Learners. International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature; Footscray, 4(2), 54–67. http://dx.doi.org.mutex.gmu.edu/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.4n.2p.54. [CrossRef]

- Nazari, B., & Mansouri, S. (2014). Dynamic assessment versus static assessment: A study of reading comprehension ability in Iranian EFL learners. Dil ve Dilbilimi Çalışmaları Dergisi, 10(2).

- Park, K. (2010). Enhancing lexicogrammatical performance through corpus-based mediation in L2 academic writing instruction (Ph.D., The Pennsylvania State University). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/pqdtglobal/docview/1732856900/abstract/EFD10DAB16AD46B5PQ/6.

- Pishghadam, R., Barabadi, E., & Kamrood, A. M. (2011). The Differing Effect of Computerized Dynamic Assessment of L2 Reading Comprehension on High and Low Achievers. Journal of Language Teaching & Research, 2(6), 1353–1358. [CrossRef]

- Poehner, M. E., & Lantolf, J. P. (2013). Bringing the ZPD into the equation: Capturing L2 development during Computerized Dynamic Assessment (C-DA). Language Teaching Research, 17(3), 323–342. [CrossRef]

- Poehner, M. E., Zhang, J., & Lu, X. (2015). Computerized dynamic assessment (C-DA): Diagnosing L2 development according to learner responsiveness to mediation. Language Testing, 32(3), 337–357. [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, N., & Bahadori Nejad, Z. (2018). An Investigation Into the Effect of Dynamic Assessment on the EFL Learners’ Process Writing Development. SAGE Open, 8(2), 215824401878464. [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, A. A., Alavi, S. M., & Razzaghifard, P. (2019). The impact of mobile-based dynamic assessment on improving EFL oral accuracy. Education and Information Technologies, 24(5), 3091–3105. [CrossRef]

- Safa, M. A., & Beheshti, S. (2018). Interactionist and Interventionist Group Dynamic Assessment (GDA) and EFL Learners’ Listening Comprehension Development. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 6(3), 37–56.

- Scotland, J. (2017). Participating in a shared cognitive space: An exploration of working collaboratively and longer-term performance of a complex grammatical structure. Retrieved from https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/handle/10871/32739.

- Shabani, K. (2014). Dynamic Assessment of L2 Listening Comprehension in Transcendence Tasks. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 98, 1729–1737. [CrossRef]

- Shabani, K. (2018). Group Dynamic Assessment of L2 Learners’ Writing Abilities. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 6(1), 129–149.

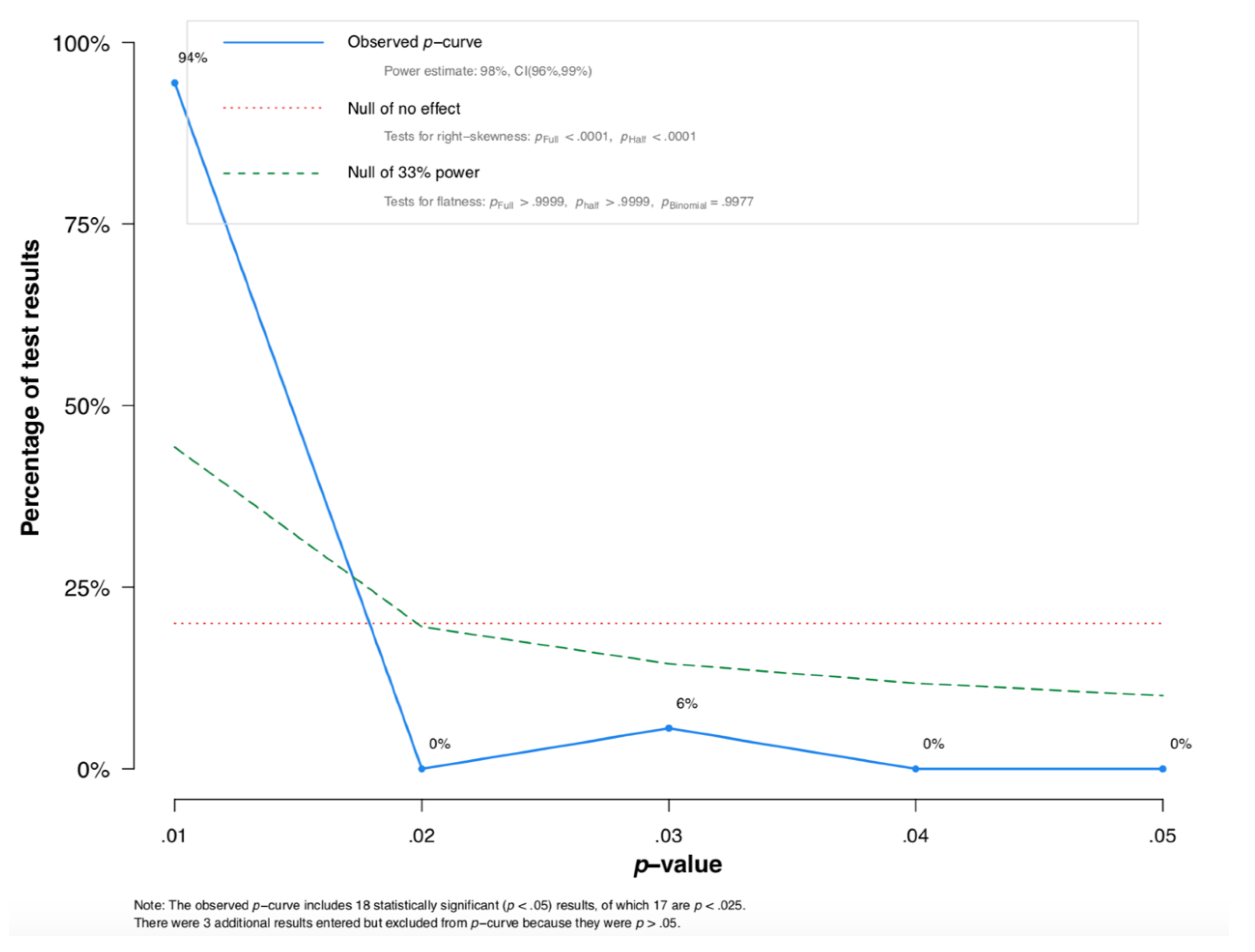

- Simonsohn, U., Nelson, L. D., & Simmons, J. P. (2014a). P-curve: a key to the file-drawer. Journal of experimental psychology: General, 143(2), 534. [CrossRef]

- Simonsohn, U., Nelson, L. D., & Simmons, J. P. (2014b). p-curve and effect size: Correcting for publication bias using only significant results. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(6), 666-681.

- Tavakoli, M., & Nezakat-Alhossaini, M. (2014). Implementation of corrective feedback in an English as a foreign language classroom through dynamic assessment. Dil ve Dilbilimi Çalışmaları Dergisi, 10(1), 211-232.

- Teo, A., & Jen, F. (2012). Promoting EFL students’ inferential reading skills through computerized dynamic assessment. Language Learning & Technology, 16(3), 10-20.

- Tocaimaza-Hatch, C. C. (2016). Mediated Vocabulary in Native Speaker-Learner Interactions During an Oral Portfolio Activity. Foreign Language Annals; Alexandria, 49(2), 336–354. http://dx.doi.org.mutex.gmu.edu/10.1111/flan.12190. [CrossRef]

- van Compernolle, R. A., & Zhang, H. (Stanley). (2014). Dynamic assessment of elicited imitation: A case analysis of an advanced L2 English speaker. Language Testing, 31(4), 395–412. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. (2017). Dynamic Assessment in English Pronunciation Teaching: From the Perspective of Intellectual Factors. Theory and Practice in Language Studies; London, 7(9), 780–785. http://dx.doi.org.mutex.gmu.edu/10.17507/tpls.0709.10. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., & Qian, D. D. (2017). Assessing English reading comprehension by Chinese EFL learners in computerized dynamic assessment. Language Testing in Asia; Heidelberg, 7(1), 1–15. http://dx.doi.org.mutex.gmu.edu/10.1186/s40468-017-0042-3. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., & Qian, D. D. (2019). Promoting L2 English learners’ reading proficiency through computerized dynamic assessment. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. (2018). Both Sides of the Interaction: Native Speaker and Nonnative Speaker Tutors Serving Nonnative Speaker Students in a University Writing Center (Ph.D., Oklahoma State University). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/pqdtglobal/docview/2271929299/abstract/EFD10DAB16AD46B5PQ/7.

| Author | Year | N | Age | Context | L2 | L2 Targeted Skill(s) | Approach | Mediator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ableeva & Lantolf | 2011 | 7 | 18-20 | University | French | L | interactionist | T-G |

| Aghaebrahimiana et. al. | 2014 | 20 | University | English | W | interventionist | T-I (G) | |

| Ajidah & Nourdad | 2012 | 197 | University | English | R | interventionist | T-G | |

| Alavi & Taghizadeh | 2014 | 32 (m) | 18-20 | University | English | W | interventionist | T-G |

| Amirian et. al. | 2014 | 28 | 17-20 | Institute | English | R | interventionist | T-G |

| Bahramlou & Esmaeili | 2019 | 45 | 13-19 | Institute | English | V | interventionist | T-G |

| Barabadi et. al. | 2018 | 91 | M=16 | School | English | L | Both | C + T-I |

| Bozorgian &Alamdari | 2018 | 180 | 16-24 | Institute | English | |||

| Daftarifrad | 2018 | 185 | N.M. | University | English | R | Interventionist | C |

| Daneshfar et. al. | 2018 | 86 | School | English | G | Interventionist | T-G | |

| Ebadi et. al. | 2018 | 75 | 18-28 | Distance | Persian | V | Interventionist | C |

| Ebadi et. al | 2018(b) | 80 | 16-24 | Institute | English | V | Interventionist | C |

| Ebrahimi | 2015 | 44(F) | 11-15 | Institute | English | S | Both | |

| Erfani & Nikbin | 2015 | 60(F) | W | T-G; P-P | ||||

| Estaji & Farahanynia | 2019 | 34 | 18-29 | Institute | English | S | Both | T-G |

| Farangi & Saadi | 2017 | 42 | 16-19 | Institute | English | L | Interactionist | T-G |

| Ghonsooly & Hassanzadeh | 2019 | 120 | 18-30 | Institute | English | V | Interactionist | T-G |

| Hamavandi et. al. | 2017 | 50 (F) | 14 - 18 | Institute | English | R | Interventionist | T-I |

| Hanifi et. al. | 2016 | 25 | University | English | V | Interventionist | T-G | |

| Hashemi et. al. | 2014 | 50 | 14-18 | School | English | L | Interactionist | T-G |

| Heidar & Afghari | 2015 | 60 | 25-32 | Institute | English | L | Interactionist | T-G |

| Hessamy & Ghaderi | 2014 | 50 (M) | 13-16 | Institute | English | V | Interactionist | T-G |

| Hidri | 2019 | 132 | 18-20 | University | English | W | Interactionist* | T-G |

| Izadi et. al. | 2018 | 30 | 18-22 | Institute | English | L | Interactionist | T-I |

| Jafary et. al. | 2012 | 60 (M) | 17-19 | English | G | Interactionist | T-G | |

| Kamali et. al. | 2018 | 46(M) | 15-20 | Institute | English | G | Interventionist | T-G |

| Kamrood et. al. | 2019 | 54 | 21-37 | University | English | L | Interventionist | C |

| Khanahmadi & Sarkhosh | 2018 | 45 | 14-19 | Institute | English | G | Interactionist | T-G; P-P |

| Khonamari & Sana’ati | 2016 | 61(M) | English | R | Interventionist | T-G | ||

| Kozulin & Levi | 2018 | 80 | 17 | School | English | S | Interactionist | T-I;T-G;P-P |

| Lin | 2010 | 123 | ||||||

| Lu & Hu | 2019 | 50 | 10 | School | English | L(phonology) | Interactionist | T-I |

| Mardani & Tavakoli | 2011 | 30(M) | Institute | English | R | Interactionist | T-G | |

| Mauludin | 2018 | 44 | 16-18 | School (technical institute) | English | W | Interactionist | T-G;T-I |

| Minaabad | 2017 | 45 | School | English | R | Both | T-I | |

| Miri et. al. | 2017 | 67(M) | 15-17 | School | English | G | Interactionist | T-I; T-G |

| Naeini | 2014 | 46 | University | English | R | Interactionist | T-I | |

| Naeini | 2015 | 102 | University | English | R | Both | T-I | |

| Nazari & Mansouri | 2014 | 30 | 15-21 | Institute | English | R | Interventionist | T-I |

| Pishghadam et. al. | 2011 | 104 | 18-44(M=28) | University | English | R | Interventionist | C |

| Poehner & Lantolf | 2013 | 163 | University | Chinese; French; Russian | L & R | Interventionist | C | |

| Poehner et. al. | 2015 | 150 | University | Chinese | L & R | Interventionist (based on interactionally developed prompts) | C | |

| Rashidi & Nejad | 2018 | 17 | 20-35 | English | W | Interactionist | T-G | |

| Rezaee et. al. | 2019 | 120 | 18-30(m=20) | Mobile-based | English | S | Interventionist | T-I |

| Safa & Beheshti | 2018 | 90(F) | 15-26 | English | L | Both | T-G | |

| Shabani | 2014 | 17 | 20-25 | University | English | L | Interactionist | T-G |

| Shabani | 2018 | 44 | English | W | Interactionist | T-G | ||

| Teo | 2012 | 68 | 18-19 | University | English | R | Interventionist | C |

| Tocaimaza-Hatch | 2016 | 9 | 20-26 | University | English | V | Interactionist | P-P |

| Van Compernolle & Zhang | 2014 | 1 | English | G | Interventionist | T-I | ||

| Yang | 2017 | 36 | University | English | S | Interventionist | T-G | |

| Yang & Qian | 2017 | 46 | M=20 | University | English | R | Interventionist | C |

| Yang & Qian | 2019 | 183 | University | English | R | Interventionist | C | |

| Ableeva | 2010 | 7 | University | French | L | Interactionist | T-G | |

| Scotland | 2017 | 52 | University | English | ||||

| Lin | 2010 | 63 | 3-4 | Kindergarten | English | L&S | interventionist | T-I |

| Purpose | L2 DA as an instruction method | L2 DA as an assessment method | L2 DA as a service method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functions | To help evaluate the effectiveness of a teaching method. To evaluate the appropriateness of learning outcomes to L2 learners. To target students’ actual needs by identifying their zones of proximal development and plan instruction accordingly. To equip students with learning strategies and techniques to develop self-regulation (and related constructs like agency). |

To check understanding while teaching. To determine if learning outcomes were met and plan near or far future learning experiences. To provide potentially less anxious assessment environments. To evaluate the appropriateness of assessments from students’ responses before giving summative assessments that could be over or below the levels of the students. To assess skills that are of an interactional nature such as speaking by creating more authentic experiences (authenticity). To evaluate the progress of students within their zones of proximal development and provide accurate estimations of the odds of success in a course. To provide detailed reports about students’ progress that contain information about their actual performance, mediated performance, and learning potential to parents, policy makers, and curriculum developers. |

To help place students in their proper levels in second/foreign language learning courses/programs. To help provide curriculum developers and textbook writers with the actual skills needed for each level based on the identified skills from DA practices. To pilot summative and large-scale test items to learners to assess its suitability for the targeted level and identify problems with items which cannot be measured but could be investigated interactionally as with cultural bounded issues. To maximize students learning experiences in writing centers and one-to-one conferencing by providing a rich reciprocal experience. To help identify talented learners through unassisted scores and learning potential scores. |

| Mediation | Could be applied using an interactionist or an interventionist approach. Different types of prompts can be used mapped with the adopted approach. Prompts may not only focus on helping acquire knowledge but also leaning strategies that contribute to ones metacognition. |

Can be applied using an interactionists or interventionist approach. Mediation targets content; the formation of prompts may not focus on metacognition as it assesses change towards achieving the learning outcomes of a course. |

Can be of various forms according to the targeted function. Mediation is of an exploratory nature hence gradual prompts might be suitable for situations where the goal is to predict instead of modify learning. |

| Requirements | A conceptualization of the nature of language and language learning by adopting theories from fields such as second language acquisition and psycholinguistics. Understanding the effect of constructs such as attention, motivation, and age on second language learning. |

Strong validity arguments. Clear purposes of assessment aligned with the learning outcomes. Short, weekly or unit based, to allow for rich reflections and continuous development of the course and swift interreference to address students’ learning difficulties. Careful design of prompts which focuses on helping learners achieve the outcomes content wise. Reliability of mediation offered (prescribed mediation) must be investigated and compared among learners who share similar characteristics. |

A clearly articulated purpose and goal of the DA intervention. A well-designed intervention that aligns with the intended function (e.g., an interactionist approach with no prescribed prompts for writing conferences vs. an interventionist approach with a prescribed mediation offered to place a student in the accurate level within a program). Reliability must be investigated and addressed thoroughly for functions that require producing accurate results such as placing students in accurate learning levels and identifying students of talent or special need. Validity evidence must be appropriate for the intended function. |

| Medium | teacher to students computerized |

teacher to student teacher to students computerized |

teacher to student Computerized |

| Practicality | Allows for the modification/adoption of teaching approaches by providing necessary evidence. Targets the whole class and emphasizes an equal opportunity learning experience considerate of whole class development. Allows for the identification of underperforming or overperforming students and creating meaningful groupings based on actual levels which will maximize learning from classes and learning from peers. |

Can be applied in class or outside class: hence saving time for more instruction time. Can provide further assessments in response to previous assessments to evaluate change between assessments. Helps design less anxious assessment experiences. Rich assessments of few or single learning outcomes yielding richer information. Meaningful assessment reports comprehended by parents and students even; number scores is meaningful as it reflects performance unassisted and assisted. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).