1. Introduction

Human beings have been searching for the basic mechanism of aging in an attempt to slow the process. From tails of the fountain of youth to modern genetics researchers have been attempting to understand the basic mechanism of aging and to slow or stop the aging process. To our knowledge, this is the first paper to show that cellular aging can be reversed by adding FURIN.

Aging is a time-related process causing the deterioration of functions in tissues and organs. Cellular senescence is a state of cell cycle arrest where cells lose the capacity to divide while maintaining metabolic activity. The accumulation of senescent cells is closely related to aging and age-related dysfunction of tissues and organs [1].

Notch signaling pathway is an evolutionally conserved pathway that is involved in the regulation of the development processes of the human body. The Notch signaling cascade is triggered when ligand expressed on another cell binds to Notch receptor. After binding, Notch receptor is cleaved by ADAM, and its intracellular domain is released and traffics into nucleus where it forms a transcription complex with other proteins and regulates the expression of downstream genes [2]. Previous studies have shown an emerging role of the Notch pathway in the regulation of aging, and that the dysregulation of Notch signaling has been implicated in several human development disorders and many cancers [3]. For example, the diminished activation of Notch may contribute to cellular senescence in skeletal muscle stem cells, and the myogenic differentiation capacity of satellite cells was achieved via forced activation of Notch [4,5].

Furin is a proprotein convertase (PC) that proteolytically cleaves precursor molecules into the mature forms [6]. In Notch signaling pathway, the nascent precursors of four members of NOTCH gene family—Pre-NOTCH1, Pre-NOTCH2, Pre-NOTCH3, and Pre-NOTCH4–undergo posttranslational modifications in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus. Furin is responsible for the maturation of NOTCH by catalyzing the proteolytic cleavage of Pre-NOTCH in Golgi [7,8,9]. Therefore, Furin plays a curial role in the activation of Notch signaling (See

Figure 1).

The purpose of this study is to identify innovative biomarkers within the Notch pathway for aging and age-related diseases, as well as potential therapeutic targets. In this study, we initially identified gene candidates with chronologically age-related expression patterns in silico, and proposed a hypothesis of Furin as a therapeutic target based on the correlation. A subsequent vitro experiment on C2C12 aged cell model indicated that Furin was able to restore age-related dysfunction, highlighting its potential as an anti-aging target.

Many disorders are more prevalent or more severe in people in their later years of life. This manuscript and finding provides hope to treat many such diseases.

| Statement of Significiance |

| Problem or Issue |

As people age they loose muscle mass |

| What is already known |

Lack of hormones may contribute to sarcopenia. |

| What this paper adds |

This paper shows how FURIN drives the Notch 2 and Notch 3 pathways leading to reversal of sarcopenia |

| Who will benefit from this information |

Aging individuals and Aging researchers |

2. Methods

2.1. In Silica Discovery

The analysis was performed with R. All codes are available upon request.

An initial retrospective analysis was conducted on the Adult Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Portal dataset [16], which contains RNA sequencing data from around 700 human individuals aged 20-79. Samples were divided into 6 age groups with a time granularity of 10 years (e.g., 20-29, 30-39, 40-49, 50-59, 60-69, 70-79). The RNA read counts data of two skin tissues of the lower leg (sun exposed) and the suprapubic region (not sun exposed) were used for differential expression (DE) analysis with DESeq2 package [17]. DE analysis across all age groups was performed on Notch-related mRNA using likelihood ratio test with a threshold of adjusted p-values 0.05. The list of Notch-related mRNA used was retrieved from Reactone [15,18,19]. For the significant DE genes identified, subsequent correlation tests were performed using ‘stats’ package between gene read counts and age groups to identify biomarkers with chronologically age-related expression patterns where absolute rho-values of 0.1 and two-side p-values of 0.05 were used as thresholds. Analysis of genes related to pre-Notch was also conducted. List of molecules investigated can be found in

Table S1.

2.2. Cell Culture

Murine skeletal myoblasts (C2C12) [20] were kindly provided by Dr. Thomas M. Suchyna (Department of Physiology and Biophysics, University at Buffalo). The cells were maintained in growth medium (GM) consisting of high glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Grand Island, NY) and 1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Cells were maintained at a confluency of less than 80% and subcultured every other day using 0.25% trypsin ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) solution suitable for cell culture (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Late passage (LP) cells, older cells, at passage 55-60 have largely lost the ability to differentiate into myotubes as described before [21], while early passage (EP) cells, younger cells, were used between passages 10-15. For cell counting, cells were trypsinized, stained with 0.4% trypan blue (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), and counted using an automatic cell counter (TC20, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

2.3. Gelatin Coating

For transfection and differentiation experiments, cells were seeded in gelatin coated 6-well plates or on gelatin coated glass coverslips in 12-well plates. For gelatine coating, gelatin type A from porcine skin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in water at 0.2% (w/v), sterilized by autoclaving, and added to the respective tissue culture dishes at 0.2 mg/cm2 for 1h at 37 °C. The solution was then aspirated, and the gelatin-coated dishes were dried in the laminar flow hood before seeding cells.

2.4. Differentiation Experiments

To initiate myoblast differentiation into multinucleated myotubes, myoblasts were seeded on gelatin coated 6-well plates or gelatin coated glass coverslips at a density of 30,000 cells/cm2 and allowed to reach ~90% confluency. Differentiation was induced by washing the cells twice in PBS before adding differentiation medium (DM) consisting of high glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 2% (v/v) horse serum, 10µg/ml insulin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) for up to 6 days.

Fusion index (FI) of myotubes was calculated by dividing the number of nuclei in myotubes by the total nuclei in a field of view ( ). FI

values are reported as mean±standard deviation (std) of at least three fields of view (> 700 total nuclei).

2.5. Plasmids and Transfection

The mus musculus 6xHis-Furin construct pcDNA3.1-mPCSK3 was a gift from Liming Pei (Addgene plasmid # 122674 ;

http://n2t.net/addgene:122674 ; RRID:Addgene_122674). Control transfections were performed using the pCMV-myc vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). 12h after plating on gelatin coated surfaces, cells were transfected with the DNA constructs using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) by adding the DNA-Lipofectamine solution straight to the GM without changing the culture medium to serum free Opti-MEM (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) to avoid induction of myotube formation. 48h after transfection, differentiation was induced as described above. At the indicated time points, cells were processed for immunofluorescence imaging or for quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR).

2.6. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from cells using Trizol

® reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. 1µg total RNA from each tissue sample was used to reverse transcribe into cDNA using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). qRT-PCR was performed using the iQ SYBR Green Supermix and the iCycler iQ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Table 1 shows the primers used in qRT-PCR. Primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT; Coralville, IA).

Relative mRNA expression was calculated by the ΔCT method. Triplicates were normalized to the average of the GAPDH housekeeping gene under the same conditions. The values are shown as mean ± std of triplicates in each experiment.

2.7. Immunofluorescence Staining and Microscopy

Cells grown on glass coverslips were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 7 min, and then blocked with 5% BSA for 1h. Incubations with the primary antibodies (α-myoin II heavy chain; Myosin 4 monoclonal antibody [MF20]; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were conducted at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation for 1h at room temperature with the appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated to FITC (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Rhodamine conjugated phalloidin was used for F-actin staining (Cytoskeleton Inc., Denver, CO). Coverslips were mounted with Prolong antifade containing 4’,6’-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Images were taken on a Leica DM 6B microscope (Deer Park, IL) and processed using Leica and ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD)

3. Results

We used the GTEx database and compared people in their 20s to their 30s, 40s, 50s, 60s and 70s (701 individuals). Our initial research, in Silica, focused exclusively on Notch pathways given the well-established knowledge of the importance of Notch in aging [2,3,4,5]. Differential expression (DE) analysis was performed to identify genes with significant expression change along the age groups in both tissues. In order to further understand the effect of chronologic age, we conducted Spearman correlation test on each significantly differentially expressed gene. The two-step tests revealed that the expression levels of Notch receptor genes NOTCH2 and NOTCH3 are negatively associated with age in both tissues; in contrast, those of downstream genes GZMB and HES1 are positively associated with age in both tissues.

To explore potential upstream mechanisms that may contribute to the observed dysregulation and identify potential target for Notch restoration, we subsequently investigated genes related to pre-Notch pathway, a regulatory pathway that governs the maturation of the Notch receptors. DE analysis and correlation test revealed that the convertase Furin was expressed with a similar pattern over age groups as NOTCH2/NOTCH3 where it is negatively associated with age. Additionally, Pearson correlation test demonstrated a strong positive correlation between Furin and NOTCH2/NOTCH3 in both tissues (See

Figure 2).

Based on the correlation between Furin and NOTCH2/3, their age-related downregulation, and the biological mechanism that Furin protease is involved in the cleavage of NOTCH precursors, we proposed a hypothesis that age-related downregulation of FURIN can lead to a decrease of Notch receptors (i.e., NOTCH2 and NOTCH3), causing dysregulation of the Notch pathway and its downstream genes such as GZMB and HES1, hence age-related diseases.

Expression of FURIN, NOTCH2 and NOTCH3 is negatively associated with aging and expression of GZMB is positively associated with aging in the C2C12 murine myoblast model

To determine the functional relevance of the observed association of these genes with age, we used the established C2C12 in vitro model of age-related muscle loss. Sarcopenia, the progressive decline in muscle mass and function that is most commonly, but not exclusively associated with aging, is linked to decreased mobility, increased risk of obesity, decrease in metabolic function and the development of associated comorbidities and mortality [22,23,24].

An established in vitro model to analyze age related muscle loss is the use of late passage C2C12 murine myoblast cell line [20]. Upon serum removal, early passage C2C12 myoblasts differentiate into functional multinucleated myotubes [25]. However, serial passaging of C2C12 cells leads to a gradual loss of myogenic differentiation similar to aging muscle cells, and three-dimensional bioengineered skeletal muscle constructs of late passage C2C12 demonstrated a replication of the phenotype of aged skeletal muscles, demonstrating the suitability of this model system to study sarcopenia related pathways in vitro [21,26,27].

Analysis of the expression of the age-related genes in early passage (EP) and late passage (LP) C2C12 cells showed a statistically significant negative association of FURIN (

Figure 2A) and NOTCH2 expression with age. A similar trend was observed with NOTCH3 that did not quite reach statistical significance (

Figure 2B). In contrast, GZMB expression was positively associated with aging in the C2C12 mouse model, confirming the observations from the in silico analysis (

Figure 3).

3.1. Increase in FURIN Expression Restores the Ability to Form Myotubes in Aged Myoblasts

To determine if loss of Furin is associated with the loss of differentiation potential, LP myoblasts were transiently transfected with a Furin expression vector for 2 days before differentiation into myotubes was initiated. As shown in

Figure 3A, exogenous FURIN mRNA expression was about 650- fold higher than endogenous FURIN mRNA at the time of differentiation initiation. The level gradually dropped after induction of differentiation but remained at about 100-200 fold higher than endogenous expression for the duration of the differentiation experiments (

Figure 3A). Analysis of GZMB expression levels in LP cells transfected with Furin show a decrease in expression, indicating the functionality of the exogenous Furin as Furin is a regulator of GZMB expression [28].

As reported previously, early passage C2C12 myotubes readily differentiate and fuse to form functional, multinucleated myotubes, an ability that is lost in late passage cells after serial passaging [21,26]. However, as shown in

Figure 3 (C-E), transient transfection of late passage C2C12 myoblasts with a Furin expression vector restores, albeit somewhat delayed, the capacity of LP myoblasts to differentiate and form myotubes. Staining for F-actin in LP cells transfected with Furin demonstrate morphological changes consistent with differentiation, i.e., elongation and alignment of cells (

Figure 4C), while staining with antibodies that recognize myosin II heavy chain was used to clearly identify fused and multinucleated myotubes and to quantify the fusion index (

Figure 3D, E) [29].

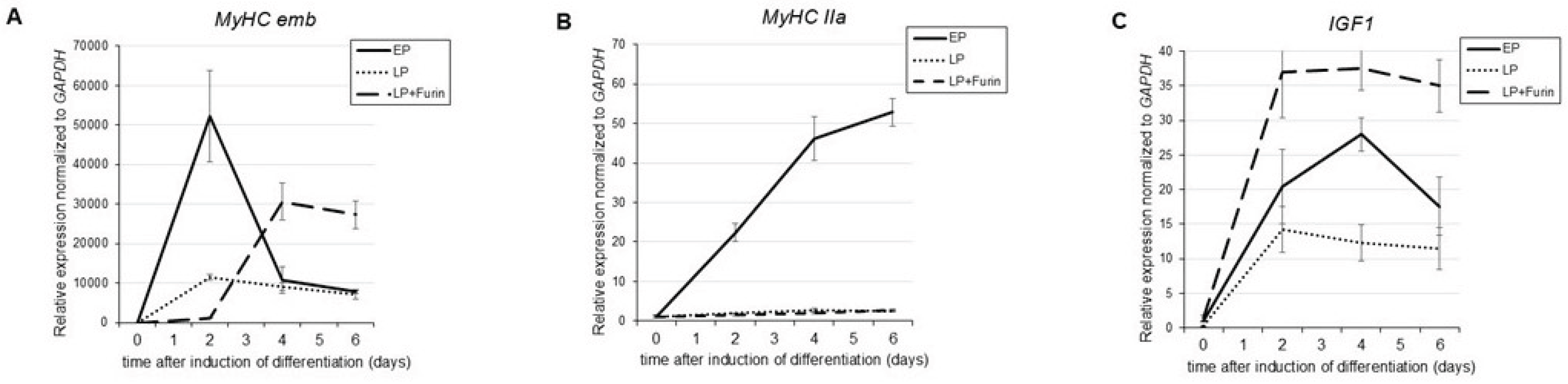

3.2. Increased FURIN Expression Restores Decreased MyHC_emb and IGF1 but not MyHC-IIa Expression During Differentiation in LP Myoblasts

During myogenesis, muscle specific genes such as the genes that encode contractile proteins including myosin heavy chains (MyHCs) are expressed. Adult mammalian skeletal muscles express 4 major types of myosin heavy chains (MyHCs) that are encoded by different genes: type I, IIa, IIx, and IIb [30,31]. In addition, 2 further isoforms, MyHC_embryonic (MyHC_emb) and MyHC_neonatal (MyHC_neo) are expressed during development and are transiently expressed during skeletal muscle regeneration after an injury [32,33]. Similar to human skeletal muscle, C2C12 cells start expressing MyHCs upon initiation of differentiation, including transient expression of the two developmental isoforms MyHC_emb and MyHC_neo [34]. As shown in

Figure 5 (A and B) expression of MyHC-IIa as a representative of MyHCs expressed in adult muscle, as well as MyHC_emb was greatly reduced in LP cells. Interestingly, while transient expression of MyHC_emb could be rescued by Furin expression in LP cells, although somewhat delayed when compared to EP cells, Furin expression had no effect on expression of MyHC-IIa. In addition, we analyzed the effect of Furin expression on IGF-1 expression, another factor that is fundamentally involved in myoblast differentiation [35,36]. As shown in

Figure 5C, and as previously reported, IGF-1 expression is greatly diminished in myoblasts that have undergone serial passaging [21], while expression of Furin lead to an overexpression of IGF-1 when compared to EP cells.

4. Discussion

We have identified a negative association of the cellular endoprotease Furin with aging and demonstrate that Furin can rescue age-related loss of myogenesis by restoring myogenetic differentiation of aged myoblasts.

In the initial bioinformatic analysis, we focused exclusively on Notch and pre-Notch pathway, given the well-established knowledge of the importance of Notch in aging, and examined the association of the genes involved in these pathway with age in lower leg and suprapubic tissue. Based on our funding of age-related downregulation of NOTCH2/3 and Furin, and the established role of Furin in the proteolytic activation of Notch precursors, we hypothesized that age-related decrease of Furin may lead to decline in Notch receptors, resulting in dysregulation and of its downstream genes such as GZMB and HES1. GZMB and HES1 were found to be positively associated with age and, therefore, negatively associated with NOTCH2/3. The GZMB gene encodes serine protease GZMB (Granzyme B), which is mainly expressed in NK cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes, and capable of mediating apoptosis [37]. Elevated GZMB level has been reported to contribute to age-related dysfunctions such as impaired pressure injuries healing [38]. The HES1 gene encodes transcriptional repressor HES1 (Hairy and Enhancer of Split-1), which can assist in maintenance of the quiescent cell state [39]. It was expected that the induction of exogenous Furin would mitigate the dysregulation of these genes in the in vitro experiment. Additionally, considering the broad range of substrates of Furin, alteration of Furin expression may affect aging via alternative mechanisms besides Notch. Therefore, we subsequently investigated the effect of Furin induction on both Notch and other well-established aging biomarkers in the aged cell model.

We used the C2C12 aging model to analyze the functional relevance of the observed reduction of Furin in age. Previous studies showed that serial passaging of C2C12 mouse myoblasts leads to the loss their differentiation ability and their ability to form multinucleated myotubes [21,27,40] through mechanisms that mimic processes that lead to aging human skeletal muscles including a reduction in IGF1 expression and alterations in the IGF-I/IGF-IR/PI3K/Akt pathways that critical for myoblast differentiation [21,41,42,43].

We show that transient expression of Furin can rescue the lost ability to form multinucleated myotubes, which suggests that a loss of Furin is intimately linked to the loss of differentiation potential of myoblasts during aging. Interestingly, analysis of the effect of Furin on the expression of muscle specific MyHCs genes showed a difference between the adult muscle MyHC IIa and MyHC-embryonic. While expression of both MyHCs is reduced in LP cells, Furin expression can rescue MyHC embryonic expression but there is no effect on the expression of MyHC IIa. While MyHC IIa is stably expressed in adult skeletal muscle, MyHC embryonic is only transiently expressed in adult muscle tissue during myogensis that occurs in response to an injury or disease and plays a critical role in differentiation of muscle progenitor cells and myoblasts [32,44,45]. Furin also rescued expression of IGF1 that is critically involved in myogenic differentiation during development as well as during muscle regeneration [21,46]. While the mechanisms by which Furin regulates IGF1 expression are not known, a possible mechanism is through activation of Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 Receptor (IGF1R), a receptor tyrosine kinase that plays a key role in cell growth, proliferation, and survival. IGF1R is initially synthesized as a precursor (proIGF1R) that requires Furin-mediated cleavage to become fully active [47].

Taken together, the selective effect of Furin on MyHC embryonic and IGF-1, both of which are essential for myogenesis suggests that Furin might be involved specifically in skeletal muscle plasticity and regeneration.

The preliminary finding indicated Furin was able to restore myotube function in the aged myoblasts cell model. This return of function gives hope that we can affect human aging. Given the ubiquity of Furin in mammalian cells, Furin has the potential to serve as an intervention target for age-related diseases in an extended scope. Reversal of aging has the potential to affect a great number of age-related disorders, including cancers, neurodegenerative disorders, autoimmune dysfunction, age-related sarcopenia and many others.

Whether or not, FURIN is the genetic fountain of youth is yet to be proven. In our study, we show that FURIN can effectively restore myotube function in an aged cell model.

5. Conclusions

Human beings have been searching for the basic mechanism of aging in an attempt to slow the process. From tails of the fountain of youth to modern genetics researchers have been attempting to understand the basic mechanism of aging and to slow or stop the aging process. This study’s retrospective RNA sequencing analysis revealed the age-related dysregulation of Furin and Notch in skin tissue. Such dysregulation was also observed in the myoblasts aging model. Furthermore, restoring Furin levels in aged myoblasts rescued age-related loss of myogenesis. To our knowledge, this is the first paper to show that cellular aging can be not only stopped by also reversed by Furin replacement. Further research is needed to see the effect of FURIN stimulation on animals and human beings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

This work has been supported in part by the NIH National Library of Medicine LMT15012495.

Author contributions

PLE wrote the initial draft of the manuscript; JL ran the bioinformatics analysis; JW, TS and WH ran the laboratory confirmation experiments; PLE, JL, JW, TS and WH all reviewed the manuscript

Conflict of Interest

Our university has a preliminary patent on FURIN for Sarcopenia

References

- Englund, D.A.; Zhang, X.; Aversa, Z.; LeBrasseur, N.K. Skeletal muscle aging, cellular senescence, and senotherapeutics: Current knowledge and future directions. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2021, 200, 111595–111595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, S.J. Notch signalling: a simple pathway becomes complex. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balistreri, C.R.; Madonna, R.; Melino, G.; Caruso, C. The emerging role of Notch pathway in ageing: Focus on the related mechanisms in age-related diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 2016, 29, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, M.E.; Suetta, C.; Conboy, M.J.; Aagaard, P.; Mackey, A.; Kjaer, M.; Conboy, I. Molecular aging and rejuvenation of human muscle stem cells. EMBO Mol. Med. 2009, 1, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conboy, I.M.; Conboy, M.J.; Smythe, G.M.; Rando, T.A. Notch-Mediated Restoration of Regenerative Potential to Aged Muscle. Science 2003, 302, 1575–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Ven, W.J. , et al., Furin is a subtilisin-like proprotein processing enzyme in higher eukaryotes. Mol Biol Rep, 1990. 14(4): p. 265-75.

- Chan, Y.-M.; Jan, Y.N. Roles for Proteolysis and Trafficking in Notch Maturation and Signal Transduction. Cell 1998, 94, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.; Bashirullah, A.; Dagnino, L.; Campbell, C.; Fisher, W.W.; Leow, C.C.; Whiting, E.; Ryan, D.; Zinyk, D.; Boulianne, G.; et al. Fringe boundaries coincide with Notch-dependent patterning centres in mammals and alter Notch-dependent development in Drosophila. Nat. Genet. 1997, 16, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logeat, F.; Bessia, C.; Brou, C.; LeBail, O.; Jarriault, S.; Seidah, N.G.; Israël, A. The Notch1 receptor is cleaved constitutively by a furin-like convertase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998, 95, 8108–8112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, E.M.; Kim, S.-K.; Sohn, J.-H.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, Y.; Kim, Y.S.; Mook-Jung, I. Furin is an endogenous regulator of α-secretase associated APP processing. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 349, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, C.; Dang, R.; Cui, Y.; Liu, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Zhu, J.; Li, D.; Li, J.; Wang, D. Characterization of plasma metal profiles in Alzheimer’s disease using multivariate statistical analysis. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0178271–e0178271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintino, L.; Manfré, G.; Wettergren, E.E.; Namislo, A.; Isaksson, C.; Lundberg, C. Functional Neuroprotection and Efficient Regulation of GDNF Using Destabilizing Domains in a Rodent Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 2169–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.G.; Tittle, T.R.; Barot, R.R.; Betts, D.J.; Gallagher, J.J.; Kordower, J.H.; Chu, Y.; Killinger, B.A. Proximity proteomics reveals unique and shared pathological features between multiple system atrophy and Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2025, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Agnaf, O.; Gibson, G.; Anwar, Z.; Sidera, C.; Isbister, A.; Austen, B. Structure and neurotoxicity of novel amyloids derived from the BRI gene. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2005, 33, 1111–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlic-Milacic, M. and S.E. Egan. Pre-NOTCH Expression and Processing. 2011 [cited 2025 Mar 14]; Available from: https://reactome.org/content/detail/R-HSA-1912422.

- Consortium, G.T. , The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet, 2013. 45(6): p. 580-5.

- Love, M.I., W. Huber, and S. Anders, Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol, 2014. 15(12): p. 550.

- Milacic, M.; Beavers, D.; Conley, P.; Gong, C.; Gillespie, M.; Griss, J.; Haw, R.; Jassal, B.; Matthews, L.; May, B.; et al. The Reactome Pathway Knowledgebase 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 52, D672–D678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassal, B. Signaling by NOTCH. 2004 [cited 2025 Mar 14]; Available from: https://reactome.org/content/detail/R-HSA-157118.

- Yaffe, D.; Saxel, O. Serial passaging and differentiation of myogenic cells isolated from dystrophic mouse muscle. Nature 1977, 270, 725–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharples, A.P.; E Stewart, C. Myoblast models of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and atrophy. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2011, 14, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, A.A. , et al., Sarcopenia. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2024. 10(1): p. 68.

- Beaudart, C.; Demonceau, C.; Reginster, J.; Locquet, M.; Cesari, M.; Jentoft, A.J.C.; Bruyère, O. Sarcopenia and health-related quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cachex- Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 1228–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, I.H. Sarcopenia: Origins and Clinical Relevance. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2011, 27, 337–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burattini, S.; Ferri, P.; Battistelli, M.; Curci, R.; Luchetti, F.; Falcieri, E. C2C12 murine myoblasts as a model of skeletal muscle development: morpho-functional characterization. . 2004, 48, 223–33. [Google Scholar]

- Shahini, A.; Choudhury, D.; Asmani, M.; Zhao, R.; Lei, P.; Andreadis, S.T. NANOG restores the impaired myogenic differentiation potential of skeletal myoblasts after multiple population doublings. Stem Cell Res. 2018, 26, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharples, A.P. , et al., Modelling in vivo skeletal muscle ageing in vitro using three-dimensional bioengineered constructs. Aging Cell, 2012. 11(6): p. 986-95.

- Maekawa, Y.; Minato, Y.; Ishifune, C.; Kurihara, T.; Kitamura, A.; Kojima, H.; Yagita, H.; Sakata-Yanagimoto, M.; Saito, T.; Taniuchi, I.; et al. Notch2 integrates signaling by the transcription factors RBP-J and CREB1 to promote T cell cytotoxicity. Nat. Immunol. 2008, 9, 1140–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, K.; Yoshida, K.; Kanie, K.; Omori, K.; Kato, R. Morphology-Based Analysis of Myoblasts for Prediction of Myotube Formation. SLAS Discov. Adv. Sci. Drug Discov. 2019, 24, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narusawa, M.; Fitzsimons, R.B.; Izumo, S.; Nadal-Ginard, B.; A Rubinstein, N.; Kelly, A.M. Slow myosin in developing rat skeletal muscle. J. Cell Biol. 1987, 104, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieczorek, D.F.; Periasamy, M.; Butler-Browne, G.S.; Whalen, R.G.; Nadal-Ginard, B. Co-expression of multiple myosin heavy chain genes, in addition to a tissue-specific one, in extraocular musculature. J. Cell Biol. 1985, 101, 618–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartore, S.; Gorza, L.; Schiaffino, S. Fetal myosin heavy chains in regenerating muscle. Nature 1982, 298, 294–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiaffino, S. Muscle fiber type diversity revealed by anti-myosin heavy chain antibodies. FEBS J. 2018, 285, 3688–3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, D.M.; Parr, T.; Brameld, J.M. Myosin heavy chain mRNA isoforms are expressed in two distinct cohorts during C2C12 myogenesis. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2011, 32, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, M.E.; DeMayo, F.; Yin, K.C.; Lee, H.M.; Geske, R.; Montgomery, C.; Schwartz, R.J. Myogenic Vector Expression of Insulin-like Growth Factor I Stimulates Muscle Cell Differentiation and Myofiber Hypertrophy in Transgenic Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 12109–12116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retamales, A.; Zuloaga, R.; Valenzuela, C.; Gallardo-Escarate, C.; Molina, A.; Valdés, J. Insulin-like growth factor-1 suppresses the Myostatin signaling pathway during myogenic differentiation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 464, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonina, I.S.; Cullen, S.P.; Martin, S.J. Cytotoxic and non-cytotoxic roles of the CTL/NK protease granzyme B. Immunol. Rev. 2010, 235, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, C.T.; Bolsoni, J.; Zeglinski, M.R.; Zhao, H.; Ponomarev, T.; Richardson, K.; Hiroyasu, S.; Schmid, E.; Papp, A.; Granville, D.J. Granzyme B mediates impaired healing of pressure injuries in aged skin. npj Aging Mech. Dis. 2021, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ren, S.; Yan, C.; Wang, C.; Jiang, T.; Kang, Y.; Chen, J.; Xiong, H.; Guo, J.; Jiang, G.; et al. HES1 revitalizes the functionality of aged adipose-derived stem cells by inhibiting the transcription of STAT1. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigot, A.; Jacquemin, V.; Debacq-Chainiaux, F.; Butler-Browne, G.S.; Toussaint, O.; Furling, D.; Mouly, V. Replicative aging down-regulates the myogenic regulatory factors in human myoblasts. Biol. Cell 2008, 100, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beccafico, S.; Riuzzi, F.; Puglielli, C.; Mancinelli, R.; Fulle, S.; Sorci, G.; Donato, R. Human muscle satellite cells show age-related differential expression of S100B protein and RAGE. AGE 2010, 33, 523–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrangelo, T.; Puglielli, C.; Mancinelli, R.; Beccafico, S.; Fanò, G.; Fulle, S. Molecular basis of the myogenic profile of aged human skeletal muscle satellite cells during differentiation. Exp. Gerontol. 2009, 44, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shanti, N.; E Stewart, C. PD98059 enhances C2 myoblast differentiation through p38 MAPK activation: a novel role for PD98059. J. Endocrinol. 2008, 198, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, M.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, A.; Bharadwaj, A.; Saini, M.; Kardon, G.; Mathew, S.J. Myosin heavy chain-embryonic regulates skeletal muscle differentiation during mammalian development. Development 2020, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiaffino, S.; Gorza, L.; Dones, I.; Cornelio, F.; Sartore, S. Fetal myosin immunoreactivity in human dystrophic muscle. Muscle Nerve 1986, 9, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musarò, A.; Rosenthal, N. Maturation of the Myogenic Program Is Induced by Postmitotic Expression of Insulin-Like Growth Factor I. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999, 19, 3115–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawowy, P.; Kallisch, H.; Kilimnik, A.; Margeta, C.; Seidah, N.G.; Chrétien, M.; Fleck, E.; Graf, K. Proprotein convertases regulate insulin-like growth factor 1-induced membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase in VSMCs via endoproteolytic activation of the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 321, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).