1. Introduction

This work presents the process of securing and the transportation of the polychrome wooden Crucifix of the co-cathedral of Santa Maria Argentea in Norcia (Perugia), 1494, attributed to Giovanni Teutonico.

This study represents a key point among the research projects applied to the restoration and conservation of cultural heritage in emergency contexts, carried out by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure (OPD) of Florence as part of the Extended Partnership PNRR project “CHANGES: Cultural Heritage Active Innovation for Next-Gen Sustainable Society”, in particular among the activities of Spoke 6 “History, conservation and restoration of cultural heritage” [1].

The long-lasting process of studying the sculpture and its state of conservation, as well as formulating a specific intervention methodology for such a delicate and complex case, began in 2018. In February of that year, the Crucifix was extracted from the ruins of the destroyed church and moved to the designated storage building in the locality of Santo Chiodo, near Spoleto (Perugia), where the OPD coordinates the conservation activities of thousands of artworks and artefacts damaged by the 2016 earthquakes, in collaboration with the Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio dell’Umbria [2-5].

The research related to the Crucifix from Norcia continued from 2021 to 2024 with a PhD project in Technology, Conservation and Restoration promoted by the Dipartimento di Storia delle Arti e dello Spettacolo of the Università degli Studi di Firenze; it was supported by the OPD as part of the main line of research within the CHANGES project on the use of green materials and VBM in emergency situations. The study focused on investigating the characteristics and possible applications of sublimating organic compounds with binding properties, in order to protect, stabilize and temporarily consolidate the preparatory and paint layers of polychrome wooden sculptures and artefacts [6-7].

The sculpture, related to the last phase of the artistic production of Giovanni Teutonico, commissioned in 1494, was positioned on the Crucifix chapel altar, along the left aisle of the church. Carved in the round and life-size (dimensions: 174 x 174 cm), the work reflects the formal canons that make it a point of intersection between the International Gothic, with its realistic anatomical features and profound expressionist

pathos, and the Italian Renaissance language, revealed in the frontal and symmetrical arrangement of the figure and the observance of bodily proportions. It was made by using several lime-wood elements, assembled with hide glue and wooden pegs, then carved, covered with a ground of gesso and animal glue and finally painted. The high quality of the

Crucifix is not only due to the refinement of the carving, but also to the richness of realistic and dramatic details, such as the locks of hair made of curled metal wires and vegetable fibers, the eyelashes and the beard hair made using copper wires, the application of multiple vegetable cords all over the preparatory layer to simulate the veins under the skin, and the presence of an articulated mechanism in the head to move the tongue. This last peculiarity is typical of the so-called “speaking Crucifixes”, traditionally used during the paraliturgical Catholic ceremonies on Good Friday since the 15

th century [8] (

Figure 1).

On October 30

th 2016, an earthquake measuring 6.5 on the Richter scale with its epicenter between the towns of Norcia and Preci caused the collapse of the roof and the upper part of the facade of the co-cathedral of Santa Maria Argentea (

Figure 2).

The collapse of the ceiling caused the

Crucifix to detach from the cross and fall to the ground. The violent impact brought about serious structural damages and fragmented the sculpture into numerous pieces, with consequent deformation of the wood fibers. In addition to that, also the preparatory and paint layers were damaged: scratches, abrasions, losses, surface deformations and cleavage from the wooden substrate. Immediately after the collapse, the instability of the building prevented the timely recovery of the sculpture fragments, which could only be extracted safely between February 14

th and 16

th 2018. During the fifteen months under the rubble, the

Crucifix was subjected to intense and constant exposure to atmospheric agents (including snow during the two cold winters), which increased the problems of internal cohesion within the layers and aggravated their washout and lifting, causing a general and severe embrittlement of the constituent materials. Moreover, much of the painted surface was covered with thick, compact concretions of debris. When the pieces were rescued by the Firefighters and moved to the storage building in Spoleto, the wood was completely soaked in water and the paint layer was swollen (

Figure 3).

Over the following five months, during which hundreds of artworks continued to be rescued from all the damaged buildings in the region, keeping the sculpture in a well-ventilated area accelerated the drying of the fragments and reduced the proliferation of biodeteriogenic agents, but unfortunately also caused a significant shrinkage of the wood, as well as the development of new liftings and losses of the already severely detached preparatory and paint layers (

Figure 4).

The need of handling the fragments of the Crucifix and moving them from the storage building in Santo Chiodo to the OPD Department of Polychrome wooden sculptures in Florence, where the long and complex restoration treatment will be carried out, was the starting point for the design of a specific system to secure the unstable preparatory and paint layers, and to temporary consolidate and lock the flakes that had already fallen, in order to prevent further material loss. To achieve this, it was decided to avoid the use of natural or synthetic adhesives typically used in such situations (i.e. animal or vegetable glue, wax, acrylic or vinyl resins): in fact, by penetrating under the cleavages and into the porosity of the materials, these adhesives would have fixed the debris to the paint layer even more firmly, with irreversible consequences and further deterioration of the artwork. The solution found ensured maximum respect for the constituent materials and enabled a gradual approach during every phase: a volatile binder was selected and applied, allowing the fragments to be temporarily consolidated during the transportation, in the best possible conditions of reversibility and retractability. Therefore, after an initial testing phase based on the specific needs of the Crucifix, the volatile organic compound chosen was menthyl lactate (MNT_LAT), whose use as a temporary consolidating agent for the conservation of cultural heritage has not yet been documented. At the same time, other solutions were adopted to reduce oscillations and vibrations during the transportation: thanks to the latest 3D scanning technologies, a system of “blocks” and “masks” was designed and 3D printed to hold the fragments of the sculpture in place, preventing them from moving, sliding or rotating. The sculpture was then placed in a double crate, internally cushioned with spring-loaded tie-rods. Finally, a customized fume hood was installed in the OPD Laboratory to contain the consolidated fragments and facilitate the sublimation of MNT_LAT, in conditions that are safe for the conservators too. These measures allowed the sculpture to be moved safely, without further detachments or losses of ground and colour.

2. Materials and Methods

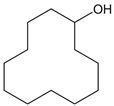

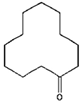

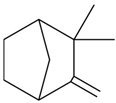

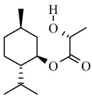

The first phase of the project was focused on the study of volatile binding media (VBM), cyclic organic compounds with adhesive and cohesive properties which, at room temperature, looks like waxy solids capable of sublimating, due to their high vapour pressure. VBM were introduced as materials for the preservation of cultural heritage in 1995, thanks to the studies by the German conservator Hans-Michael Hangleiter and chemists Elisabeth Jägers and Erhard Jägers on cyclododecane (CDD), camphene (CNF) and L-menthol (MNT) [9]. Over the years, their high reversibility and versatility of application have ensured their widespread use in various fields of conservation: they have mainly been used as temporary consolidating agents or adhesives, but also as surface protectants, water repellents and provisory supports for fragmented artefacts made of various materials. The most widely used and documented since the late 1990s is undoubtedly CDD. Our research originated from the need to find one or more VBM capable of replacing CDD, as it wasn’t at that time commercially available due to the closure in 2020 of the manufacturing laboratory Ephemeral GmbH in Otzberg (Germany), where Hangleiter himself had been producing it since 2013. The product also had to be suitable for use on the Giovanni Teutonico’s

Crucifix. Thus, a testing project was set up to analyze the physical and chemical properties of five VBM in addition to CDD: cyclododecanol (CDOL), cyclododecanone (CDON), camphene (CNF), L-menthol (MNT) and L-menthyl lactate (MNT_LAT) (

Table 1,

Figure 5).

-

Cyclododecane is a saturated cycloalkane that looks like a semi-transparent, waxy crystalline solid with a slight moldy smell at room temperature. It is completely non-polar, water-repellent and soluble only in hydrocarbon solvents. It is mainly used as a reaction intermediate for the synthesis of polyamides, polyesters and varnishes [10].

In archaeological excavations, CDD is used during block lifting and packaging operations, as well as consolidating, coating and releasing agent during casting for the reproduction of fragments. On clay and ceramic artefacts, it’s used as protective agent during the desalination process of fragile objects with delicate, water-sensitive painted surfaces. It’s also used for protection, water repellency, temporary consolidation and fixing on stones, wall paintings, easel paintings, textiles and paper materials. Spray CDD can be applied to create a uniform opaque layer on surfaces to be scanned for the acquisition of 3D digital models [6,11-40].

-

Both cyclododecanol and cyclododecanone have a similar structure to CDD: the former has a hydroxyl group (-OH), while the latter has a carbonyl group (=O). Like CDD, they’re both used in the synthesis of polyamides, polyesters and varnishes.

As of today, their use for conservation has not been documented [6,41-42].

-

Camphene is a natural monoterpene found in the essential oils of numerous plant species (especially conifers). At room temperature, it looks like a semi-transparent waxy solid with a pungent, refreshing smell similar to camphor. It is soluble in both non-polar and polar solvents and is used in the synthesis of perfumes, lacquers and insecticides, as plasticizer for resins and as a substitute for camphor [43].

CNF has been tested on wall paintings, archaeological artefacts, ceramics and paper materials [6,7,9,29,35,37].

-

L-menthol is a cyclic monoterpene, the main component of peppermint oil and essential oils from other mint species. At room temperature, it looks like a transparent, waxy, crystalline solid with needle-like crystals and a pungent, refreshing minty smell. It is soluble in both non-polar and polar solvents and is used as flavouring agent or fragrance in food, cosmetics, medicine and chemicals [44].

It was introduced as consolidating agent for wall paintings, and is also used on archaeological materials, ceramics and polychrome surfaces [6,7,9,35,37,45-54].

L-menthyl lactate is an ester of menthol and lactic acid. At room temperature, it looks like a semi-transparent waxy solid with small needle-like crystals and a more fruity and less pungent minty smell than MNT. It is soluble in both polar and non-polar organic solvents and is used as flavouring agent in food and cosmetics [6,55].

In order to be applied to the surface of the artworks, VBM must be converted into liquid form; this change of state can be achieved either by heat, thanks to their thermoplastic properties, or by solvents. Therefore, three different application methods have been defined for each material: melted, in solution with drop application, and in solution with spray application.

The six VBM were melted using a hot spatula, fitted with a special tip shaped like a small crucible; this allowed for controlled and precise application, setting the treatment temperature according to the melting point of the different compounds. For the two applications in solution, saturated solutions of each VBM were prepared, dissolving each volatile binder in three of the most commonly used solvents in conservation: cyclohexane for hydrocarbons, ethanol for alcohols, and acetone for ketones. They were chosen in order to work with the maximum quantity of VBM in solution. Each solution was dripped using laboratory micropipettes and sprayed by airbrush and compressor (P ≅ 1 bar; distance from the surface ≅ 5 cm).

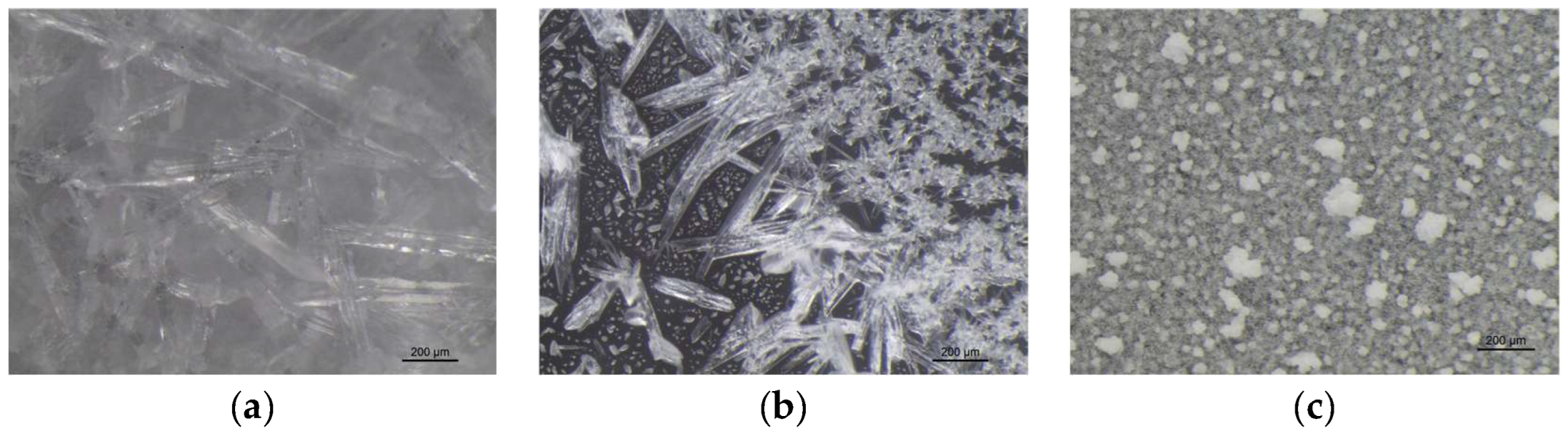

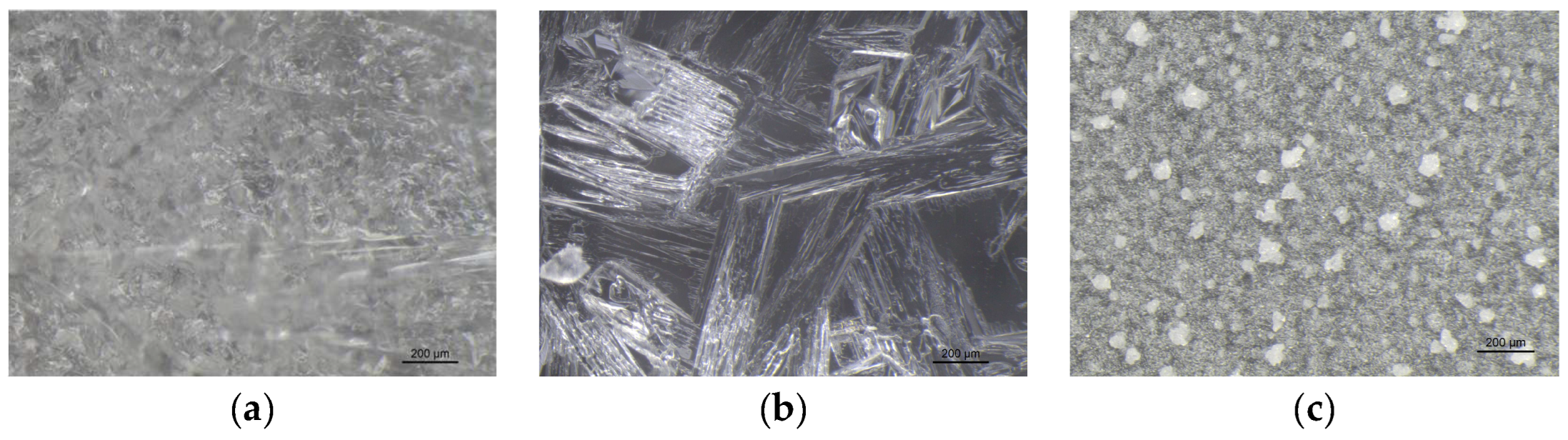

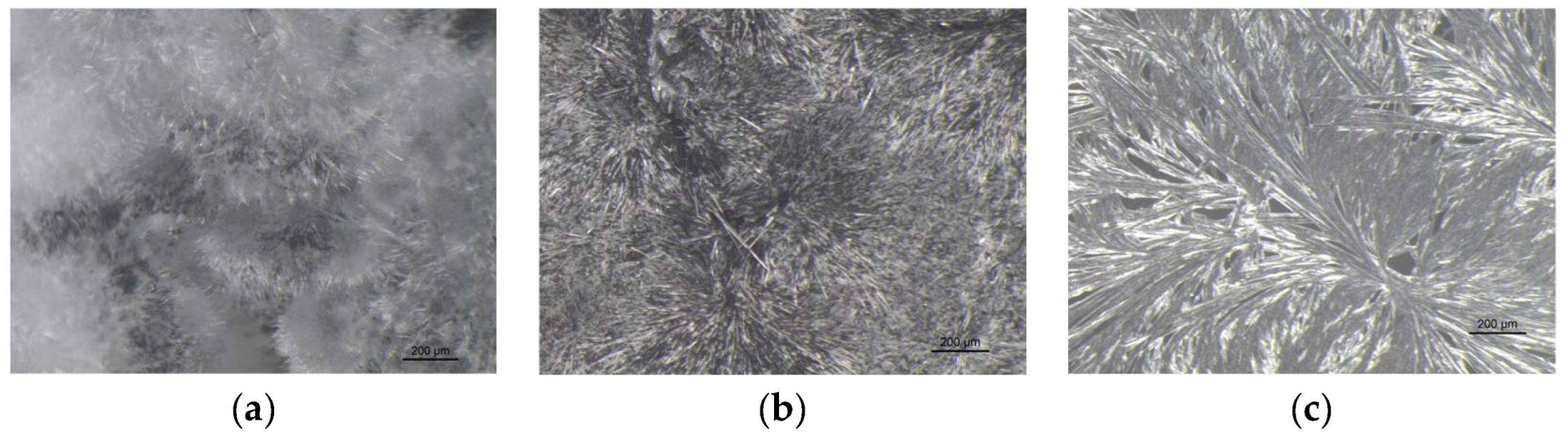

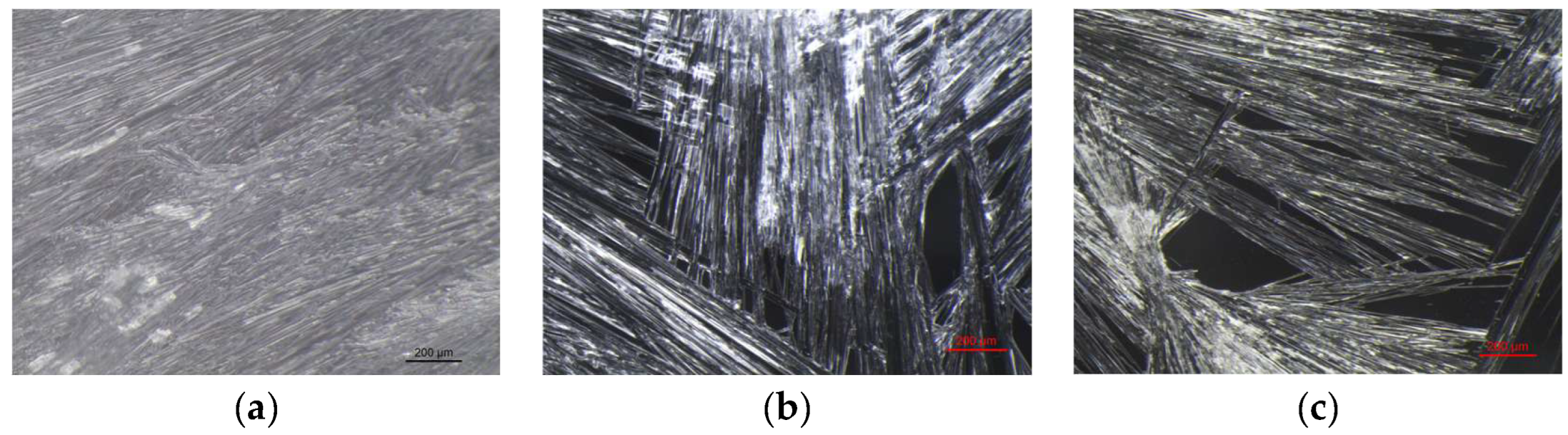

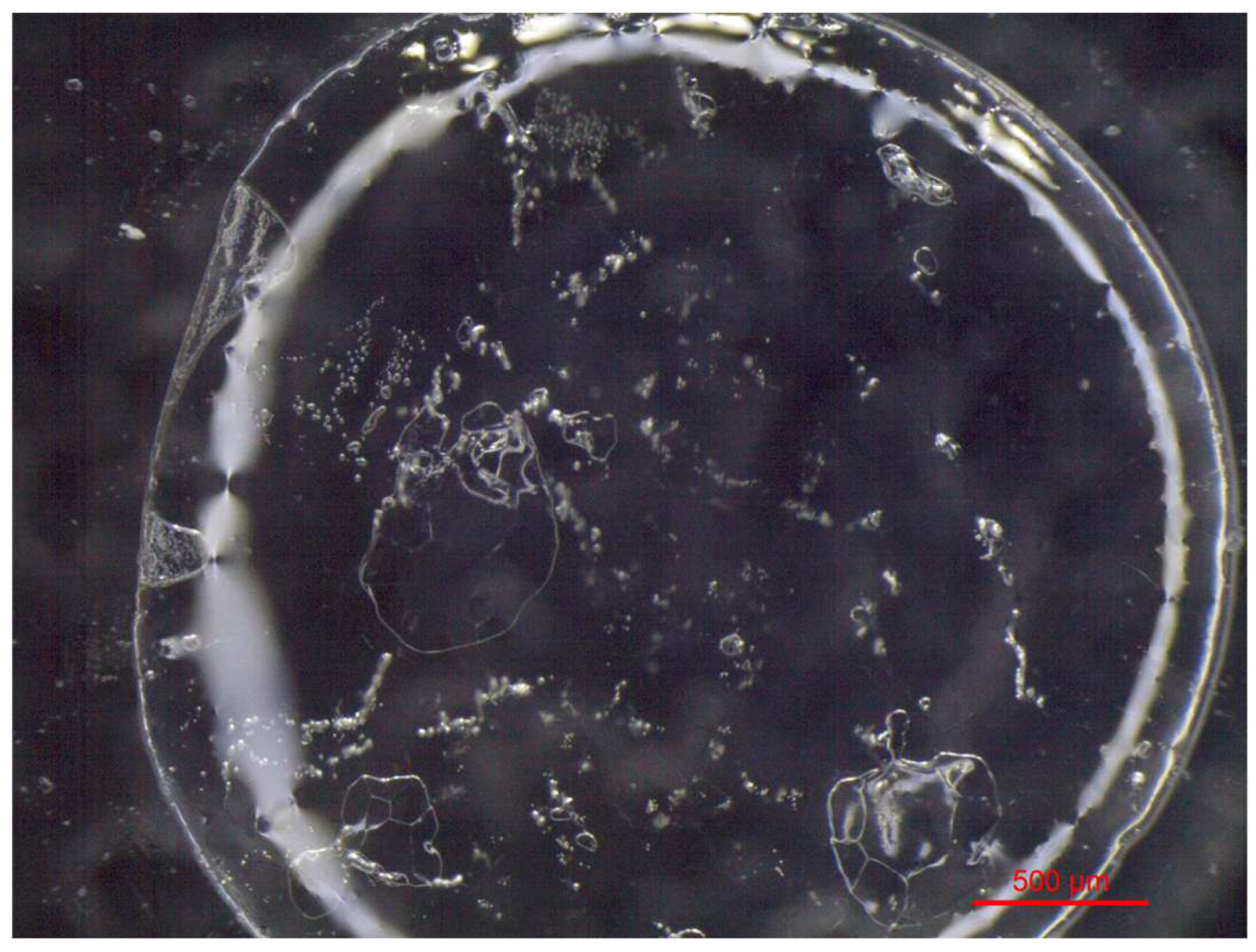

VBM were applied to glass slides and the morphology of the crystalline films was observed and photographed under a stereomicroscope. The crystalline structure depends on the ratio between the nucleation rate (formation of crystallization nuclei) and the crystal accretion rate: if the former prevails over the latter, smaller crystals are obtained and the solid has a structure more similar to the amorphous state; conversely, if the accretion rate exceeds the nucleation rate, a few larger crystals are formed, and the solid takes on a structure more similar to that of a single-crystal. It has been observed that the melted compounds form compact, hard and resistant crystalline films on the surface, characterized by small crystals that are very close together. This type of solidification occurs because there is a sudden decrease in temperature between the hot melted products and the cold surface of the glass slides, and therefore the crystals do not have time to expand. Crystalline films generated from drop-applied solutions consist of crystals of variable sizes, depending on the concentration of VBM and the volatility of the solvent; in general, they are less resistant and hard, as both the size of each crystal and the distance between them increases. Lastly, spray-applied VBM solutions are much softer and more fragile, as they consist largely of very small crystals, which already solidify during propulsion and deposit in multiple layers on the surface, without forming actual and compact crystalline films. The only exception is CNF in solution: regardless of the application method, it does not crystallize because it forms azeotropic mixtures, which are unable to solidify at room temperature before sublimation (

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11).

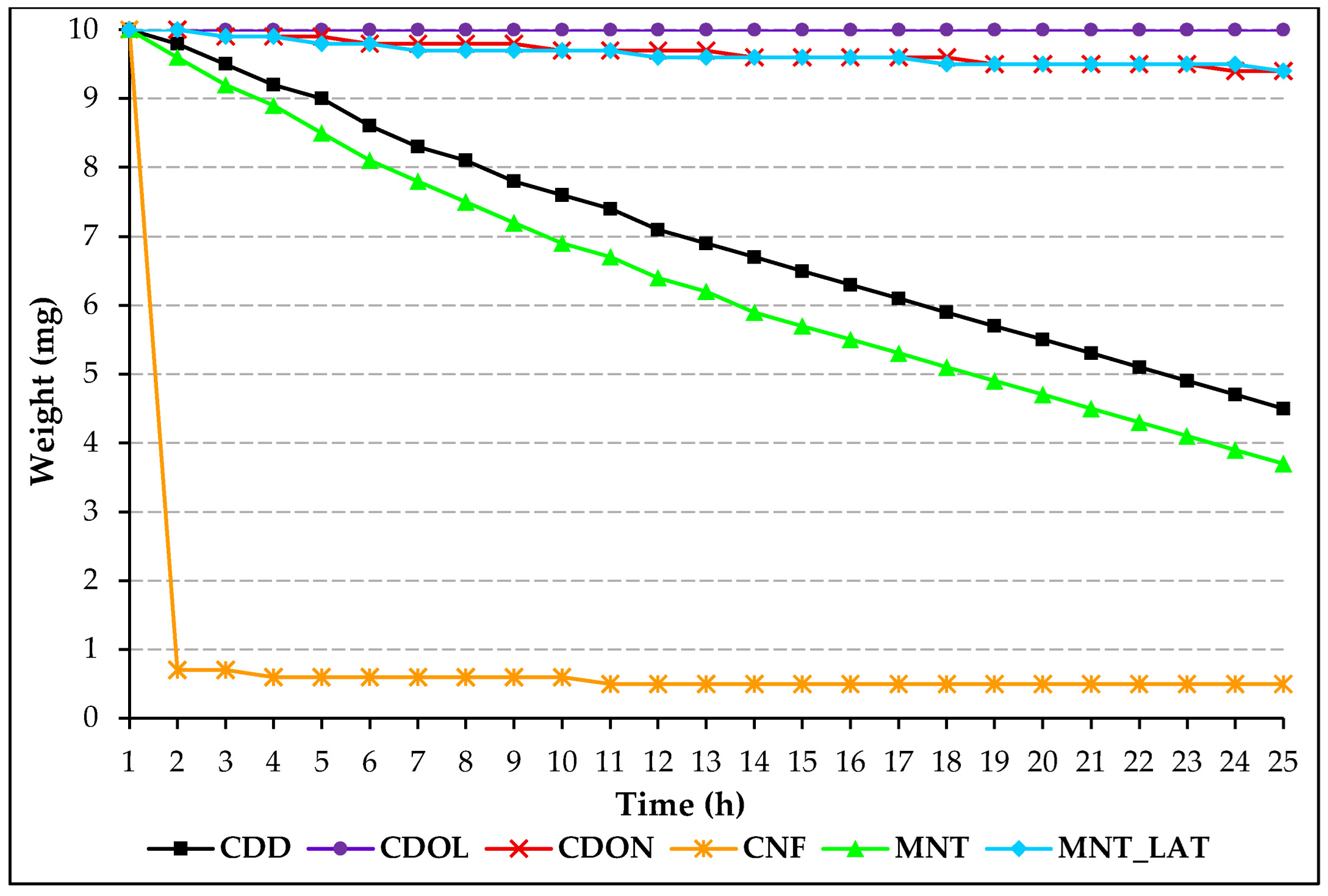

The sublimation rate was then estimated by measuring the weight variation of the samples at regular intervals on an analytical balance; the test was performed in an insulated box at a controlled temperature of 25±1°C to minimize the impact of environmental factors (temperature, pressure, ventilation). In this way, the sublimation rate was mainly influenced by the application method, the quantity of volatile binder present in each solution and the evaporation rate of each solvent. These same three parameters also determined the variation in size of the crystals formed, their compactness and the area of the exposed surface.

Melted VBM have a more compact crystalline films, so they sublimate more slowly than those in saturated solution. Among VBM in saturated solutions, spray-applied ones sublimate faster because the crystals are smaller and part of the solvent already evaporates during propulsion. The collected data were processed into linear graphs, where the slope represents the sublimation rate (mg/h). For melted VBM, it is possible to compare the linear graphs, as exactly the same amount of material was applied to each glass slide; however, this is not possible for saturated solutions, where the concentration of VBM varies according to their solubility parameters. Comparing the data, we can see that CDD and MNT have similar sublimation rates, as do CDON and MNT_LAT. In contrast, CNF sublimates very quickly, while the sublimation of CDOL is so slow that it hasn’t been detected (

Figure 12,

Table 2).

A fundamental element for the application of VBM on cultural heritage is their ability to leave a negligible amount of residue on the treated surface. Such residues are essentially due to a minimal presence of impurities, which could derive from: industrial production processes; chemical transformations of molecules; possible chemical interactions with the substrate which they are applied on. To this end, a test was carried out to measure the quantity of any residues after complete sublimation. Only melted VBM (except CDOL, which has proven to be non-volatile) were analyzed to avoid possible interference from solvents. The VBM samples applied to the glass slides were weighed with an analytical balance at the time of crystallization and after complete sublimation. The percentage of residues released by each VBM was calculated by determining the ratio between the initial and final weights. The residues of CDD, MNT and MNT_LAT are fairly negligible and transparent (0,7%), while CNF and CDON release detectable quantities of yellowish residual substances (≥ 3,5%) (

Table 2).

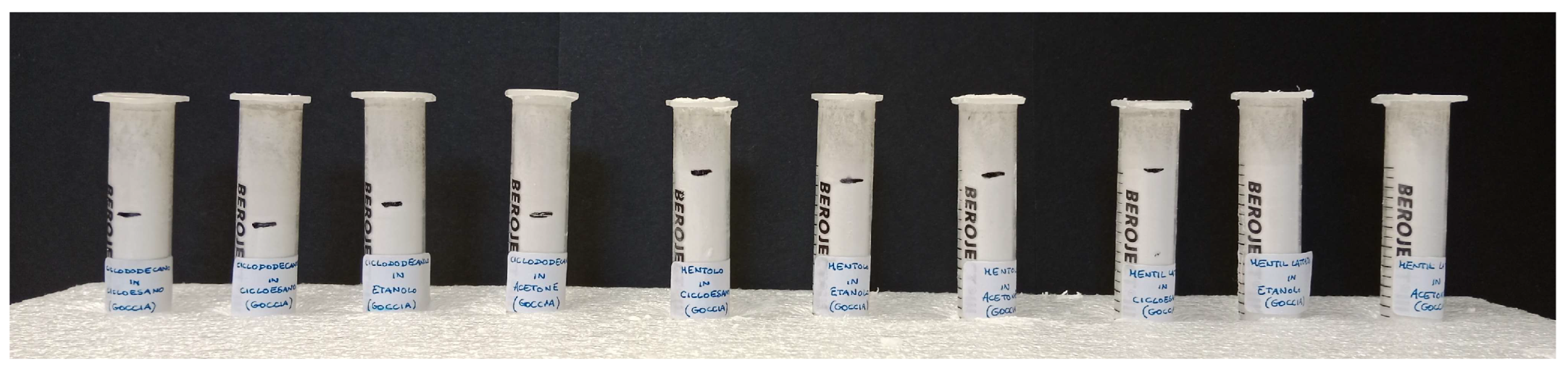

In order to evaluate the consolidating power of VBM, their capacity of penetration was analyzed. Mock-ups were created with porosity and cohesion characteristics similar to those of a degraded generic preparatory layer. The ambient temperature was stabilized at 25±1°C. Graduated cylinders (diameter = 1,5 cm) were filled with Bologna gesso (hydrate calcium sulphate) without any binder to simulate decohesion. To the upper surface of the cylinders 2,0 ml of each volatile binder were applied melted and in saturated solutions, both dripped and sprayed. After 24 hours, the penetration depth was measured with a caliper and the volume of gesso affected was estimated. CNF and CDON were excluded due to the excessive release of non-volatile residues resulting from the previous test (

Figure 13). The crystallization of melted VBM occurs very quickly on the surface, due to the sudden decrease in temperature between the melted substance and that of the gesso and the environment. For this reason, the degree of penetration is low. More specifically, CDD and CDOL crystallize more rapidly and more superficially than MNT and MNT-LAT, as their melting points are much higher than the temperature of the application surface (with rapid cooling, the compounds solidify more quickly and are unable to penetrate deeply). The degree of penetration of the drop-applied saturated solutions depends on the quantity of volatile binder present in the solution and the volatility of the solvent. Finally, the spray-applied saturated solutions didn’t penetrate the mock-ups because the dissolved volatile binders accumulated on the surface as small semi-solid crystalline flakes (

Table 3).

It is important to emphasize that the results of this penetration test must be interpreted in light of its empirical nature. Mock-ups are not perfectly comparable to real situations, as the presence of the plastic cylinder inhibits contact with the air, thereby slowing down both the crystallization and sublimation of VBM. Furthermore, it’s not possible to accurately measure the depth of penetration of VBM into the innermost bulk of the mock-ups, as only their presence on the cylinder walls is detected. However, it’s still possible to make some observations based on a comparison of the results obtained, with a view to applying VBM on brittle preparatory and paint layers.

3. Results

The results of the tests made it possible to select the VBM with the best properties and define the most suitable application methods for the case study of the Crucifix of Santa Maria Argentea.

Among the five melted compounds, the following were excluded: CDOL because it’s non-volatile; CNF because it forms a film that is too soft, has too rapid sublimation times and leaves a high percentage of non-volatile residues after sublimation (3,5%); CDON because it leaves a very high amount of non-volatile residual substances (11,4%, the highest percentage of all the materials tested). On the other hand, both MNT and MNT_LAT proved suitable for application testing.

From the set of saturated VBM solutions with drop application, those containing CNF were discarded because the binder didn’t crystallize after the evaporation of any of the three solvents, as were those containing CDON due to the excessive release of non-volatile residues; CDOL solutions were not chosen either, because the crystalline films weren’t compact enough, with crystals too small and sparse to ensure a good consolidation.

The spray application method was discarded for all the solutions, as all VBM form crystals that aren’t so compact and sufficiently resistant to mechanical stress; furthermore, the crystalline films only form on the surface, without penetrating the substrate.

In light of all these results, MNT and MNT_LAT, whether applied melted or as dripped saturated solutions, passed all the tests.

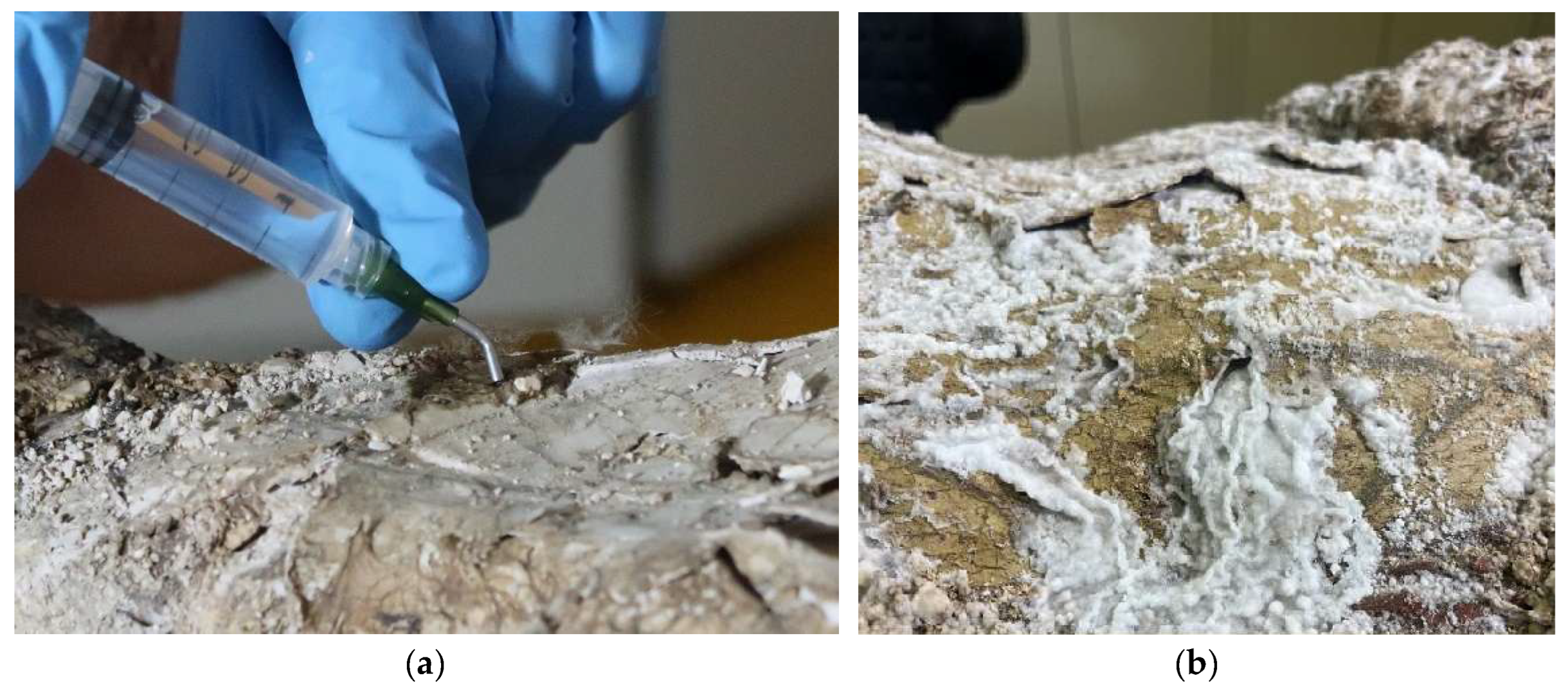

Before applying any of the compounds on the entire

Crucifix, application tests were carried out on the fragment of the right leg. MNT and MNT_LAT were injected via syringe, both on surface and under the cleavages. The saturated solutions of the two VBM crystallized too slowly and formed crystalline films that weren’t compact enough, so they couldn’t appropriately consolidate the layers (the solubility of cyclohexane, ethanol and acetone on the paint layers had been tested beforehand). Moreover, all the attempts to do multiple applications in the same area were unsuccessful, as the addition of solvent caused the crystalline film that had already formed to redissolve, preventing the stratification and not filling the voids between the wood and the preparation. On the contrary, both the melted VBM formed compact and resistant crystalline films, with excellent consolidating properties. Their low viscosity allows for easy transmission via syringe, even in the most difficult to reach areas. Consecutive applications allow the crystals to stratify and fill the empty spaces under the cleavages. VBM were melted in special wax heaters with adjustable temperature; they were then applied using syringes with blunt needles of different curvatures and gauge measures. This method made it possible to quickly liquefy large amounts of VBM and distribute them over wide areas of the sculpture. Given that the two VBM tested showed almost equal consolidating capability, MNT_LAT was selected because it guarantees a longer-lasting action, thanks to its lower sublimation rate (about ten times lower than MNT); also, its less pungent smell helps during the operating phase (

Figure 14).

The results obtained from the analytical and application tests enabled the selection of MNT_LAT and the definition of the most suitable methodology for the case study. So, a special area for the temporary consolidation of the Crucifix was set up inside the storage building in Santo Chiodo. The smallest fragments of the sculpture, consolidated with melted MNT_LAT applied via syringe, were placed in rigid plastic boxes, internally upholstered with expanded polyethylene (Ethafoam®) and cushioned with acid-free tissue paper. At the same time, the consolidation was also carried out on the larger fragments placed on the pallet. The treatment was accomplished by four conservators, and took four days of work and approximately 3 kg of MNT_LAT (

Figure 15).

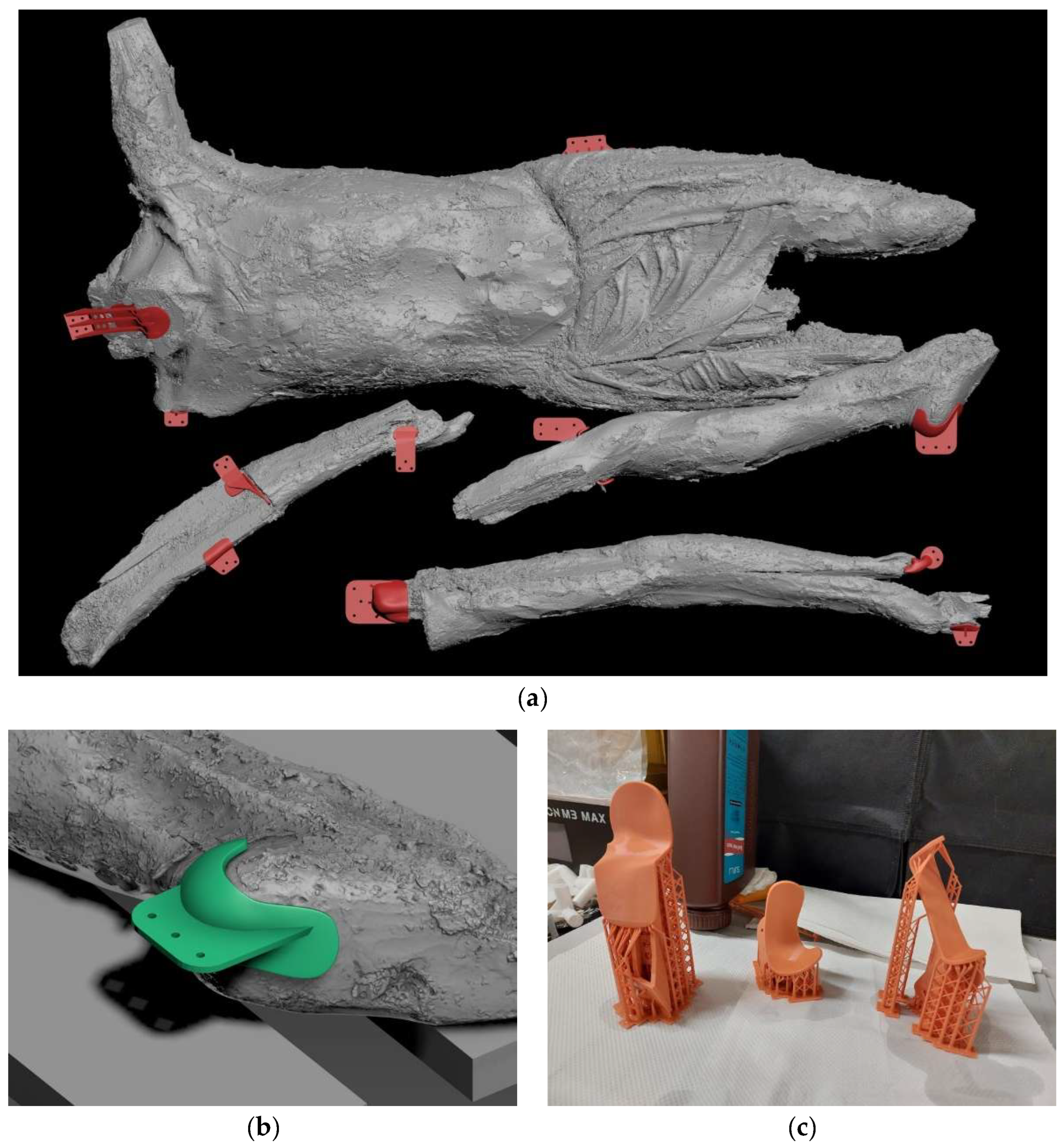

In parallel with the study of VBM for the consolidation of the preparatory and paint layers of the

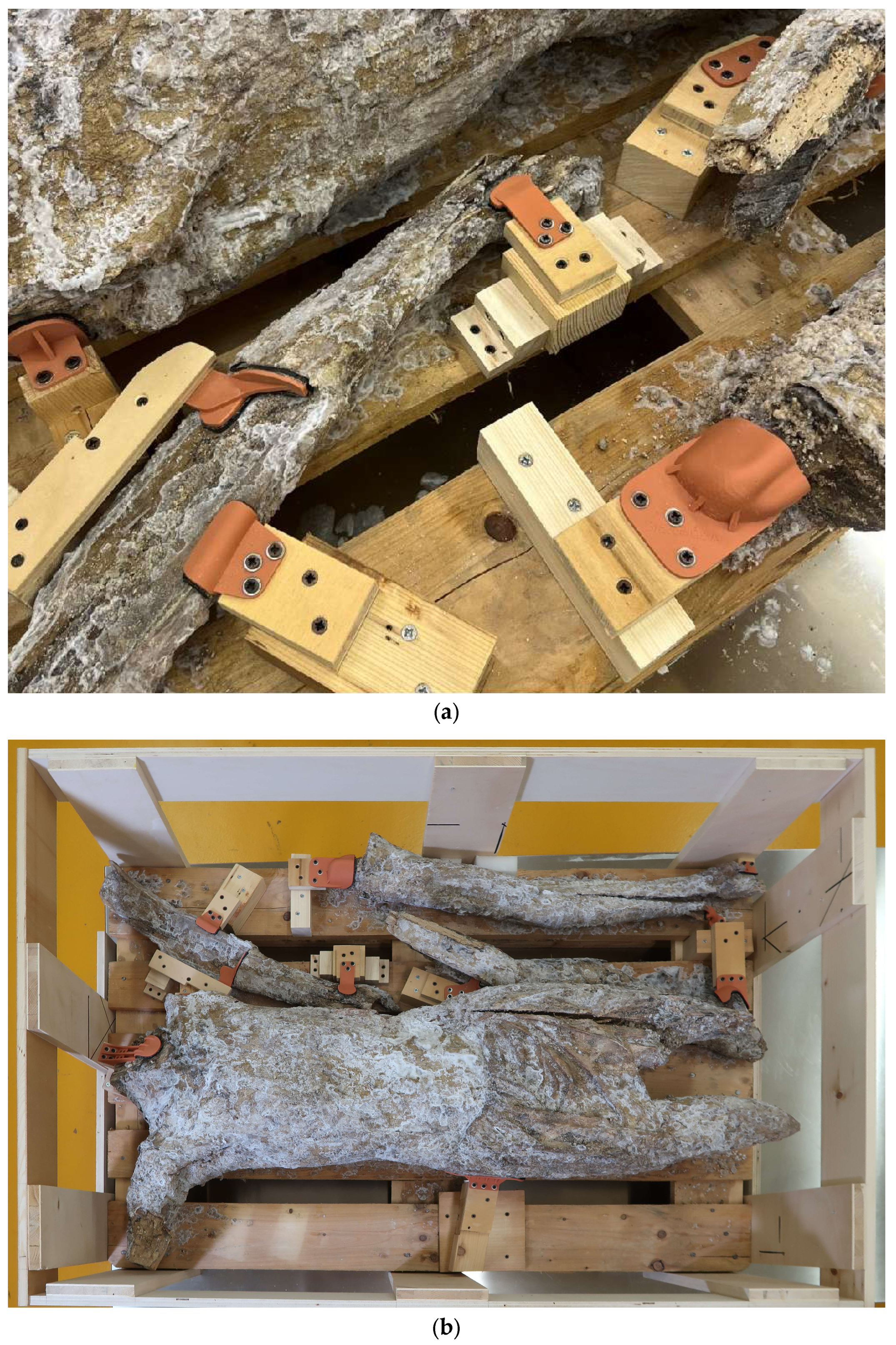

Crucifix, its transportation and subsequent storage in the OPD Department of Polychrome wooden sculptures were planned. In particular, the larger fragments of the sculpture were the most complicated: after been extracted from the rubble in 2018, they had been placed on a wooden pallet and hadn’t been moved since, due to their extreme fragility. A specific locking system was designed for them. The entire surface was 3D scanned and a digital model was created. For each fragment (the torso, the left leg and both arms), four areas without ground and colour were identified as ideal support surfaces for “blocks”. These were made with wooden pieces screwed to the pallet, to the ends of which were fixed 3D “masks” printed using the digital model. Each block was positioned opposite to another one, so as to contrast any possible rotational or translational movement of the fragment during the transportation. Each one of the twelve masks was 3D printed with a special stereolithographic resin, with excellent detail reproduction accuracy and low elastic modulus (this allows it to break in the event of mechanical shock, rather than exerting excessive pressure on the fragment of the sculpture). They were coated with a double cushioning layer of the synthetic rubber foam Aerstop® (

Figure 16 and

Figure 17). Finally, some wooden crossbeams were screwed around the pallet to create a “cage” around the

Crucifix.

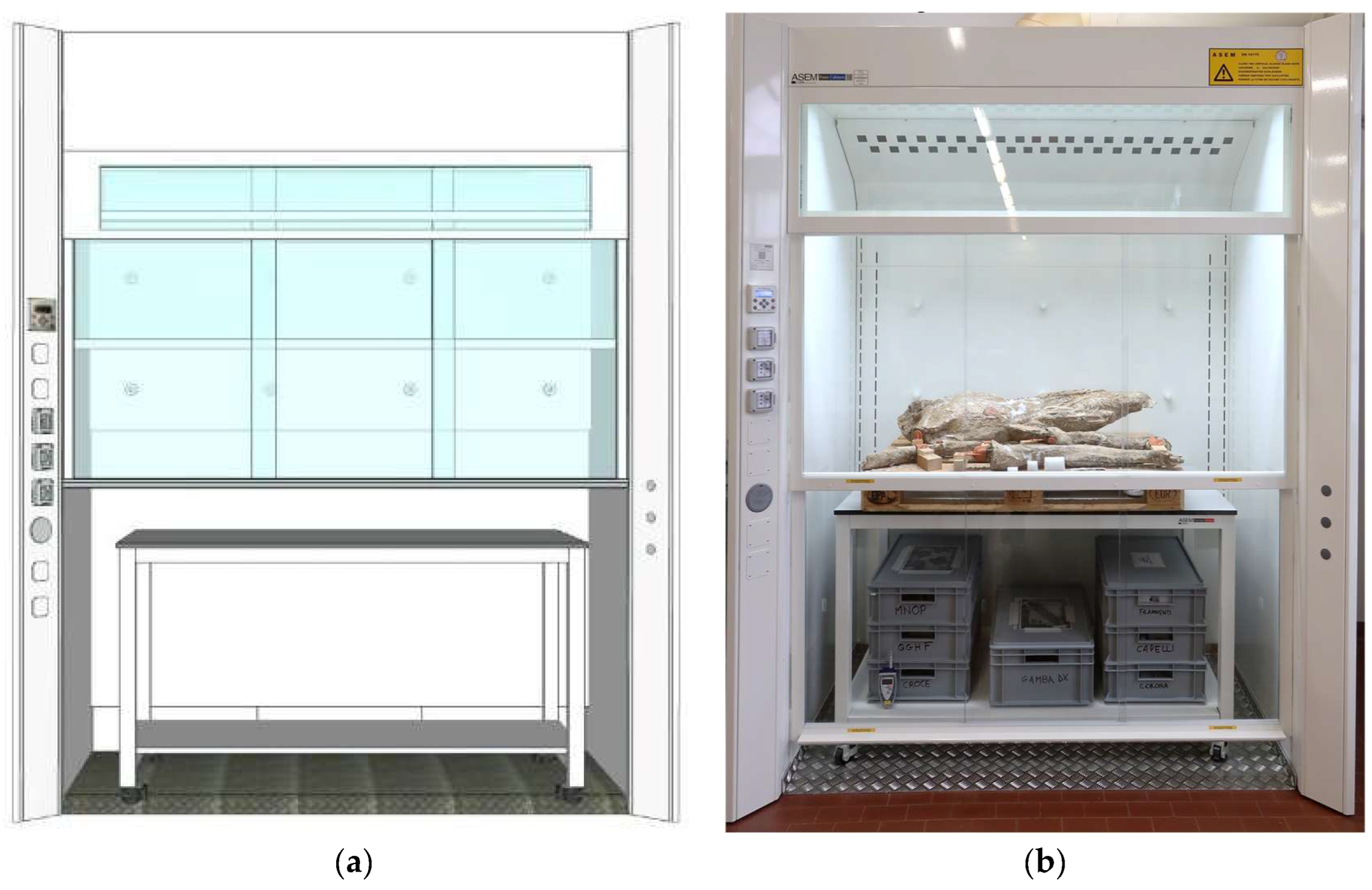

This protective structure was then placed in a double crate made with an internal system of spring-loaded tie-rods which connected the two wooden crates. This system allowed the sculpture to travel suspended during the journey by truck, in order to absorb and cushion any mechanical shock (

Figure 18).

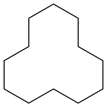

Finally, after the removal from the crate in the OPD laboratory, the fragments still placed on the pallet and the boxes with the smaller ones were put in a customized walk-in fume hood, in order to keep them safe and to speed up the sublimation of MNT_LAT (

Figure 19).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This case study confirmed the importance of VBM for the conservation of cultural heritage, with particular reference to their consolidating properties in the process of securing works damaged by catastrophic events. Analytical tests provided fundamental results for characterizing compounds with these properties: it was possible to discard some (CDOL, CDON, CNF) and select others (MNT and MNT_LAT) in addition to CDD, which has since become commercially available again. In particular, the introduction of MNT_LAT and its first successful application in the field of conservation represent an excellent innovation. The range of possibilities disposable for conservators is therefore broader, and further research into these compounds is encouraged.

The tenacity of MNT_LAT's consolidating power was definitively proved when the crate was opened. At that point, it was discovered that the “block” holding the Crucifix's neck had broken, probably due to a particularly strong vibration during the transportation by truck. The break caused the torso to rotate slightly and shift from its original position. Nevertheless, the presence of the solid film of MNT_LAT on the surface and beneath the cleavages ensured the stability of the preparatory and paint layers, preventing them from collapsing or falling off. Only some debris from the hollow interior of the torso, where the binder had not been applied, detached.

The coordinated system of temporary consolidation with melted MNT_LAT, the creation of blocks with 3D printed masks and the double crate with spring-loaded tie-rods has made it possible to move the sculpture safely, without the need to handle the most fragile fragments, and prevented the detachment and loss of further painting material. The positioning in the fume hood is facilitating and speeding up the sublimation of MNT_LAT, in conditions that are safe for the conservators too, allowing them to begin the next steps of this complex restoration project: once again, the presence of the volatile binder will allow mechanical cleaning to begin, in order to remove the thick deposits of debris without damaging the colour. The conservation treatment on the Giovanni Teutonico’s Crucifix will be carried out in parallel with further scientific tests (crystallographic studies, possible consequences of crystallization on the porosity of the substrate) and application tests on different materials (paintings on canvas, murals, paper, etc.).

Funding

The project is funded by the European Union - Next Generation EU under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR) - Mission 4 Education and research - Component 2 From research to business - Investment 1.3, Notice D.D. 341 of 15/03/2022, entitled: Cultural Heritage Active Innovation for Sustainable Society proposal code PE0000020 - CUP F53C22000690006, duration until 28.02.2026.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge conservators Arianna Acciai and Giulia Ciabattini for their hard work and professionalism during the consolidating and packaging operations in Santo Chiodo; conservator Mattia Mercante for 3D scanning and printing; art historians Riccardo Gennaioli and Renata Pintus (OPD) as coordinators of the project; conservation scientist Andrea Cagnini and all the colleagues of the OPD Scientific Laboratory for the analysis; conservators Luciano Ricciardi e Andrea Santacesaria (OPD) for the anoxic treatment; conservator Oriana Sartiani (OPD) for coordinating relations with SABAP Umbria and Centro Operativo Beni Culturali of Santo Chiodo; conservator Marina Ginanni (OPD) for sharing photographic documentation; all the colleagues of the OPD Dipartment of Polychrome wooden sculptures; OPD Purchasing, Technical and Administrative Offices; conservator Nicola Bruni and art historians Giovanni Luca Delogu, Elena Marchionni and Giulia Spina (SABAP Umbria and Centro Operativo Beni Culturali of Santo Chiodo) for their constant availability and support; all the freelance conservators operating in Santo Chiodo for their kind collaboration; conservators Roberto Bonaiuti (OPD), Giulia Basilissi (Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Florence) and Flavia Puoti (Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence) for sharing their experiences in valuable discussions; Atelier Cultura di Marzia Tomasin & C. s.n.c. for the video recording; conservator Veronica Collina for helping with the text review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OPD |

Opificio delle Pietre Dure |

| PNRR |

Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza |

| VBM |

Volatile Binding Media |

| CDD |

Cyclododecane |

| CDOL |

Cyclododecanone |

| CDON |

Cyclododecanol |

| CNF |

Camphene |

| MNT |

L-menthol |

| MNT_LAT |

L-menthyl lactate |

References

- Cultural Heritage Active Innovation for Next-Gen Sustainable Society. Available online: https://www.fondazionechanges.org/ (accessed on 2nd October 2025).

- Mercalli, M.; Pinna, A.; Mencarelli, R. Tesori della Valnerina. Interventi e restauri dopo il terremoto, 1st ed.; Quattroemme Srl: Perugia, Italy, 2017.

- Sartiani, O. L’attività della Task Force Restauratori - Firenze per l’Umbria nel 2018. Conclusione del primo progetto. OPD Restauro 2018, 30, pp. 350-361.

- Mercalli, M. Linee guida per l’individuazione, l’adeguamento, la progettazione e l’allestimento di depositi per il ricovero temporaneo di beni culturali mobili con annessi laboratori di restauro, 1st ed.; Campisano Editore Srl: Roma, Italy, 2023.

- AA. VV. La gestione del Patrimonio Culturale in situazioni di emergenza. Testimonianze e casi studio anni 2021-2022-2023, 1st ed.; VirArt ODV: Bastia Umbra, Italy, 2024.

- Amato, V. I leganti volatili alternativi al ciclododecano: studio e applicazione per la messa in sicurezza e il consolidamento temporaneo del crocifisso ligneo policromo di Santa Maria Argentea a Norcia. PhD Thesis, Università degli Studi di Firenze, Florence, Italy, 28/03/2025, https://hdl.handle.net/2158/1417752 (accessed on 2nd October 2025).

- Another Crucifix attributed to the Giovanni Teutonico’s workshop from the church of Madonna Addolorata in Norcia (Perugia) was studied and partially restored during a Master's degree thesis at the OPD Scuola di Alta Formazione e Studio in 2020-2021. The sculpture had also been damaged by the 2016 earthquake; in particular, the right arm had been buried under rubble for a long period of time, leaving it in a very poor state of conservation. On that occasion, an early research on volatile binders began: it was aimed to temporarily consolidate the degraded materials for allowing the removal of debris and then the adhesion of the preparatory and paint layers.

- Amato, V. Il restauro di un crocifisso ligneo attribuito alla bottega di Giovanni Teutonico, distrutto durante il terremoto del 2016: consolidamento temporaneo del colore con adesivi volatili, risanamento strutturale e ricomposizione. Graduation Thesis, OPD-SAFS, Florence, Italy, 2021, pp. 127-131; 135-164.

- Amato, V.; Bassi, S. Il restauro strutturale di un Crocifisso attribuito alla bottega di Giovanni Teutonico danneggiato dal sisma del 2016. OPD Restauro 2021, 33, pp.193-199.

- Cavatorti, S. Giovanni Teutonico. Scultura lignea tedesca nell’Italia del secondo Quattrocento, 1st ed.; Aguaplano: Perugia, Italy, 2016.

- Hangleiter, H. M.; Jägers, E.; Jägers, E. Flüchtige Bindemittel - Teil 1: Anwendungen, Teil 2: - Materialen und Materialeigenschaften. Zeitschrift für Kunsttechnologie und Konservierung 1995, 9, pp. 385-392.

- PubChem: Cyclododecane. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Cyclododecane (accessed on 2nd October 2025).

- Brückler, I.; et al. Cyclododecane: Technical Note on Some Uses in Paper and Objects Conservation. JAIC 1999, 38, pp. 162-175. [CrossRef]

- Keynan, D.; Eyb-Green, S. Cyclododecane and Modern Paper: a note on ongoing research. WAAC Newsletter 2000, 22, https://cool.culturalheritage.org/waac/wn/wn22/wn22-3/wn22-306.html (accessed on 2nd October 2025).

- Stein, R.; et al. Observations on Cyclododecane as a Temporary Consolidant for Stone. JAIC 2000, 39, pp. 355-369, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3179979 (accessed on 2nd October 2025).

- Caspi, S.; Kaplan, E. Dilemmas in transporting unstable ceramics: A look at cyclododecane. Objects Specialty Group Postprints 2001, 8, 116-35, https://faic.wpenginepowered.com/osg-postprints/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2015/02/osg008-007.pdf (accessed on 2nd October 2025).

- Maish, J.; Risser, E. A Case Study in the Use of Cyclododecane and Latex Rubber in the Molding of Marble. JAIC 2002, 41, pp. 127-137. [CrossRef]

- Nichols, K.; Mustalish, R. Cyclododecane in Paper Conservation Discussion. The Book and paper Group Annual 2002, 21, pp. 81-84.

- Perkins Arenstein, R.; et al. NMAI good tips: Application and bulking of cyclododecane, and mass production of supports. Objects Speciality Group Postprints 2003, 10, pp. 176-187, https://resources.culturalheritage.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2015/02/osg010-16.pdf (accessed on 2nd October 2025).

- Muros, V., Hirx, J. The Use of Cyclododecane As a Temporary Barrier for Water-Sensitive Ink on Archaeological Ceramics During Desalination. JAIC 2004, 43, pp. 75-89. [CrossRef]

- Perkins Arenstein, R.; Davidson, A.; Kronthal, L. An investigation of cyclododecane for molding fossil specimens. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 2004, 24, pp. 1-18, https://vertpaleo.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Davidson_et_al_2004.pdf (accessed on 2nd October 2025).

- Watters, C. Cyclododecane: A Closer Look at Practical Issues. Anatolian Archaeological Studies 2007, 16, pp. 195-204, http://www.jiaa-kaman.org/en/aas/index16.html (accessed on 2nd October 2025).

- Boschetti, E.; Borgioli, L. Il fascino discreto del ciclododecano. Progetto Restauro 2007, 42, pp. 2-5.

- Hangleiter, H. M.; Saltzmann, L. Un legante volatile: il ciclododecano. In Materiali e metodi per il Consolidamento e Metodi Scientifici per Valutarne l’efficacia, 1st ed.; Cesmar7; Il Prato: Saonara, Italy, 2008, pp. 109-113.

- Rowe, S.; Rozeik, C. The uses o cyclododecane in conservation. Studies in Conservation 2008, 53, pp. 17-31. [CrossRef]

- Hiby, G. Il ciclododecano nel restauro di dipinti su tela e manufatti policromi, 1st ed.; Il Prato: Saonara, Italy, 2008.

- Borgioli, L.; Boschetti, E.; Splendore, A. Preconsolidare e velinare: l’opzione ciclododecano. Kermes 2009, 22, pp. 67-73.

- Bucher, S.; Xia, Y. The Stone Armor from the Burial Complex of Qin Shihuang in Lintong, China: Methodology for Excavation, Restoration, and Conservation, including the Use of Cyclododecane, a Volatile Temporary Consolidant. Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road: Second International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites, Agnew, N.; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, US, 2010; pp. 218-224.

- Riggiardi, D. Il ciclododecano nel restauro dei manufatti artistici, 1st ed.; Il Prato: Saonara, 2010.

- Brown, M.; Davidson, A. The use of cyclododecane to protect delicate fossils during transportation. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 2010, 30, pp. 300-303. [CrossRef]

- Geller, B.; Hiby, G. Ciclododecano e Camphene Triciclene nel restauro della carta, 1st ed.; Il Prato: Saonara, Italy, 2011.

- Sahmel, K.; et al., Removing dye bleed from a sampler: new methods for an old problem. Textile Speciality Group Postprints 2012, 22, pp. 78-90.

- Bagan, R.; Tavares da Silva, A. The use of Cyclododecane on easel paintings. The Picture restorer 2013, 42, pp. 42-47.

- Bassi, S. Lo ‘studio’ di Piero Tredici e il restauro della Bestia macellata (1961): analisi dei materiali e sperimentazione sugli adesivi per fermatura. Graduation Thesis, OPD-SAFS, Florence, Italy, 2015, pp. 67-81.

- Muñoz-Viñas, S.; Vivancos-Ramón, V.; Ruiz-Segura, P. The Influence of Temperature on the Application of Cyclododecane in Paper Conservation. Restaurator. International Journal for the Preservation of Library and Archival Material 2016, 37, pp. 29-48 . [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Marín, C.; et. al. Cyclododecane as opacifier for digitalization of archaeological glass. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2016, 17, pp. 131-140. [CrossRef]

- Rozeik, C. Subliming Surfaces. Volatile Binding Media in Heritage Conservation, 1at ed; University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Papini G.; et al. Evaluation of the effects of cyclododecane on oil paintings. IJCS 2018, 9, pp. 105-116.

- Sadek, H.; H. Berrie, B. H.; Weiss, R. G. Sublimable layers for protection of painted pottery during desalination. A comparative study. JAIC 2018, 57, pp. 189-202. [CrossRef]

- Singh, M. R.; Gupta, D. A. Removal of Bats’ Excreta from Water-Soluble Wall Paintings Using Temporary Hydrophobic Coating. JAIC 2021, 60, pp. 269-280. [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, C.; Godts, S. Cyclododecane as protection for water-sensitive polychromy during water bath desalination of limestone sculptures: The case study of a mid-15th-century wall-mounted memorial from the Burgundian Netherlands. In Transcending Boundaries: Integrated Approaches to Conservation. ICOM-CC 19th Triennial Conference Preprints, Bridgland, J.; ICOM-CC: Paris, France, 2021, https://www.icom-cc-publications-online.org/4282 (accessed on 2nd October 2025).

- Attblime. High Performance 3D-Scanningspray. Available online: https://graichen.de/attblime-de/#attblime (accessed on 2nd October 2025).

- PubChem: Cyclododecanol. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/15595 (accessed on 2nd October 2025).

- PubChem: Cyclododecanone. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/13246 (accessed on 2nd October 2025).

- PubChem: Camphene. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/6616 (accessed on 2nd October 2025).

- PubChem: Menthol. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/16666 (accessed on 2nd October 2025).

- Han, X.; et al. The use of menthol as temporary consolidant in the excavation of Qin Shihuang’s terracotta army. Archaeometry 2014, 56, pp. 1041-1053. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Huang, X.; Zhang, B. Morphological studies of menthol as temporary consolidant for urgent conservation in archaeological field. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2015, 18, pp. 271-278. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; et al. Menthol-based eutectic mixtures: Novel potential temporary consolidants for archaeological excavation applications. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2019, 39, pp. 103-109. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z. C.; et al. Study of solidification of menthol for the applications in temporary consolidation of cultural heritage. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2020, 44, pp. 83-89. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; et al. Studies of internal stress induced by solidification of menthol melt as temporary consolidant in archaeological excavation using resistance strain gauge method. Heritage Science 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Acciai, A. Il restauro dei modelli pittorici di Antonio Cioci per un commesso in pietre dure. Studio e applicazione di adesivi naturali per la fermatura e il consolidamento di due dipinti su tela. Graduation Thesis, OPD-SAFS, Florence, Italy, 2022, pp. 143-178.

- Borrelli, C. Nuovi approcci al restauro paleontologico: il caso dei carnivori di Pirro Nord, Apricena (FG). Graduation Thesis, OPD-SAFS, Florence, Italy, 2025.

- Bressan, A. Spada in ferro ed elmo in bronzo di periodo ellenistico dalla tomba 52 della necropoli di Santa Maria Cardetola, Crecchio (CH). Microscavo, intervento conservativo e nuove proposte di consolidamento dei materiali organici residui. Graduation Thesis, OPD-SAFS, Florence, Italy, 2022, pp. 143-152.

- Bressan, A.; et al. Il microscavo di alcuni reperti dalla tomba 52 dalla Necropoli di Santa Maria Cardetola, Crecchio (CH). Studi e sperimentazioni di prodotti consolidanti. OPD Restauro 2022, 34, pp. 66-73.

- Ciabattini, G. Il fondo Leonardo Savioli: dal Centro Pecci allo studio dell’artista. Restauro strutturale di un dipinto su compensato, messa in sicurezza delle opere e proposte per l’allestimento. Graduation Thesis, OPD-SAFS, Florence, Italy, 2022, pp. 147-151, 195-196.

- PubChem: Menthyl lactate. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/7076215 (accessed on 2nd October 2025).

Figure 1.

Giovanni Teutonico, Crucifix, 1494, polychrome wooden sculpture, 174 x 174 cm, chapel of the Crucifix, co-cathedral of Santa Maria Argentea, Norcia (Perugia), before the earthquake. (Credits: Sandro Bellu; © Archidiocesi di Spoleto-Norcia).

Figure 1.

Giovanni Teutonico, Crucifix, 1494, polychrome wooden sculpture, 174 x 174 cm, chapel of the Crucifix, co-cathedral of Santa Maria Argentea, Norcia (Perugia), before the earthquake. (Credits: Sandro Bellu; © Archidiocesi di Spoleto-Norcia).

Figure 4.

Details of the Crucifix inside the storage building in Santo Chiodo (Spoleto): (a) right side of the abdomen; (b) right shoulder; (c) left leg; (d) right knee.

Figure 4.

Details of the Crucifix inside the storage building in Santo Chiodo (Spoleto): (a) right side of the abdomen; (b) right shoulder; (c) left leg; (d) right knee.

Figure 5.

Images at the stereomicroscope of solid-state VBM at room temperature (4x magnification): (a) CDD; (b) CDOL; (c) CDON; (d) CNF; (e) MNT; (f) MNT_LAT.

Figure 5.

Images at the stereomicroscope of solid-state VBM at room temperature (4x magnification): (a) CDD; (b) CDOL; (c) CDON; (d) CNF; (e) MNT; (f) MNT_LAT.

Figure 6.

Images at the stereomicroscope of CDD (8x magnification): (a) melted CDD; (b) dripped saturated solution of CDD in cyclohexane; (c) sprayed saturated solution of CDD in cyclohexane.

Figure 6.

Images at the stereomicroscope of CDD (8x magnification): (a) melted CDD; (b) dripped saturated solution of CDD in cyclohexane; (c) sprayed saturated solution of CDD in cyclohexane.

Figure 7.

Images at the stereomicroscope of CDOL (8x magnification): (a) melted CDOL; (b) dripped saturated solution of CDOL in acetone; (c) sprayed saturated solution of CDOL in acetone.

Figure 7.

Images at the stereomicroscope of CDOL (8x magnification): (a) melted CDOL; (b) dripped saturated solution of CDOL in acetone; (c) sprayed saturated solution of CDOL in acetone.

Figure 8.

Images at the stereomicroscope of CDON (8x magnification): (a) melted CDON; (b) dripped saturated solution of CDON in ethanol; (c) sprayed saturated solution of CDON in ethanol.

Figure 8.

Images at the stereomicroscope of CDON (8x magnification): (a) melted CDON; (b) dripped saturated solution of CDON in ethanol; (c) sprayed saturated solution of CDON in ethanol.

Figure 9.

Images at the stereomicroscope of MNT (8x magnification): (a) melted MNT; (b) dripped saturated solution of MNT in acetone; (c) sprayed saturated solution of MNT in acetone.

Figure 9.

Images at the stereomicroscope of MNT (8x magnification): (a) melted MNT; (b) dripped saturated solution of MNT in acetone; (c) sprayed saturated solution of MNT in acetone.

Figure 10.

Images at the stereomicroscope of MNT_LAT (8x magnification): (a) melted MNT_LAT; (b) dripped saturated solution of MNT_LAT in acetone; (c) sprayed saturated solution of MNT_LAT in acetone.

Figure 10.

Images at the stereomicroscope of MNT_LAT (8x magnification): (a) melted MNT_LAT; (b) dripped saturated solution of MNT_LAT in acetone; (c) sprayed saturated solution of MNT_LAT in acetone.

Figure 11.

Images at the stereomicroscope of melted CNF (4x magnification).

Figure 11.

Images at the stereomicroscope of melted CNF (4x magnification).

Figure 12.

Linear graph showing the variation in weight (mg) as a function of time (h) of the melted VBM.

Figure 12.

Linear graph showing the variation in weight (mg) as a function of time (h) of the melted VBM.

Figure 13.

Mock-ups during the test for evaluating the capacity of penetration of VBM.

Figure 13.

Mock-ups during the test for evaluating the capacity of penetration of VBM.

Figure 14.

Application of MNT_LAT on the Crucifix: (a) syringe injection of the melted binder; (b) crystalline film on the surface and under the cleavages.

Figure 14.

Application of MNT_LAT on the Crucifix: (a) syringe injection of the melted binder; (b) crystalline film on the surface and under the cleavages.

Figure 15.

Details of the Crucifix after the consolidation treatment: (a) torso; (b) right leg and other smaller fragments.

Figure 15.

Details of the Crucifix after the consolidation treatment: (a) torso; (b) right leg and other smaller fragments.

Figure 16.

Blocking system designed for the transportation of the larger fragments: (a) 3D digital model of the Crucifix with the “masks”; (b) detail of the left heel; (c) some 3D printed “masks”. (Credits: Mattia Mercante).

Figure 16.

Blocking system designed for the transportation of the larger fragments: (a) 3D digital model of the Crucifix with the “masks”; (b) detail of the left heel; (c) some 3D printed “masks”. (Credits: Mattia Mercante).

Figure 17.

Blocking system realized for the transportation of the larger fragments: (a) detail of some masks screwed to the pallet; (b) the pallet with the consolidated and blocked fragments.

Figure 17.

Blocking system realized for the transportation of the larger fragments: (a) detail of some masks screwed to the pallet; (b) the pallet with the consolidated and blocked fragments.

Figure 18.

The Crucifix placed inside the double crate.

Figure 18.

The Crucifix placed inside the double crate.

Figure 19.

The customized walk-in fume hood: (a) digital rendering (Credits: Genelab Srl); (b) the Crucifix inside the fume hood after the transportation.

Figure 19.

The customized walk-in fume hood: (a) digital rendering (Credits: Genelab Srl); (b) the Crucifix inside the fume hood after the transportation.

Table 1.

Chemical structural formulas of the six tested VBM: cyclododecane (CDD), cyclododecanol (CDOL), cyclododecanone (CDON), camphene (CNF), L-menthol (MNT) and L-menthyl lactate (MNT_LAT).

Table 2.

Physical and chemical parameters of the tested VBM. The data obtained from the tests for the sublimation rate and the residue rate are also shown.

Table 2.

Physical and chemical parameters of the tested VBM. The data obtained from the tests for the sublimation rate and the residue rate are also shown.

| |

CDD |

CDOL |

CDON |

CNF |

MNT |

MNT_LAT |

| Raw formula |

C12H24

|

C12H24O |

C12H22O |

C10H16

|

C10H20O |

C13H24O3

|

| CAS number |

294-62-2 |

1724-39-6 |

830-13-7 |

79-92-5 |

2216-51-5 |

59259-38-0 |

| Supplier |

CTS 1

|

TCI 2

|

TCI 2

|

Sigma-Aldrich |

Sigma-Aldrich |

Sigma-Aldrich |

| Item code |

01159100-01 |

C0461 |

C0462 |

456055 |

W266590 |

W37480 |

| Lot |

400 |

FHJ01 |

WWQ3G-IP |

MKCH6072 |

SHBM6897 |

SHBM7087 |

| Purity (%) |

100 |

>98 |

>99 |

>94,5 |

>99 |

>97 |

| Density (g/m3) |

0,82 |

- |

- |

0,85 |

- |

- |

| Melting point (°C) |

60,7 |

76-80 |

61-63 |

48-52 |

42-45 |

42-47 |

| Boiling point (°C) |

247 |

104 |

113 |

159-160 |

212 |

140-142 |

| Flash point (°C) |

98 |

- |

- |

26 |

94 |

>113 |

| Auto-ignition point (°C) |

175 |

380 |

280 |

- |

- |

- |

| Vapour pressure (hPa) |

13,3 (at 100°C) |

- |

- |

3,8 (at 20°C) |

0,19 (at 25°C) |

- |

| Water solubility (g/l at 20°C) |

0,01 |

- |

- |

0,0042 |

0,397 |

- |

| Cyclohexane solubility (g/ml at 25°C) |

0,70 |

0,57 |

0,08 |

1,50 |

4,40 |

0,95 |

| Ethanol solubility (g/ml at 25°C) |

- |

0,48 |

0,47 |

1,20 |

1,00 |

0,80 |

| Acetone solubility (g/ml at 25°C) |

- |

0,95 |

0,20 |

1,50 |

3,40 |

0,95 |

| Sublimation rate (mg/h at 25°C) * |

0,2 |

- |

0,02 |

9,3 |

0,2 |

0,02 |

| Residue rate (%) * |

0,7 |

- |

11,4 |

3,5 |

0,7 |

0,7 |

| LD50/rat (g/kg) |

>10 |

>2,5 |

>2,5 |

>5 |

>2,9 |

>2,5 |

Table 3.

Estimated volume of gesso (cm3) penetrated by 2,0 ml of VBM.

Table 3.

Estimated volume of gesso (cm3) penetrated by 2,0 ml of VBM.

| |

Melted |

Drop-applied solutions |

| |

|

Cyclohexane |

Ethanol |

Acetone |

| CDD |

0,1 |

6,1 |

- |

- |

| CDOL |

0,01 |

5,5 |

5,4 |

5,9 |

| MNT |

1,8 |

3,7 |

4,6 |

3,9 |

| MNT_LAT |

1,7 |

3,8 |

4,5 |

3,7 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).