Public Policy Relevance Statement

This paper’s mixed method approach examines the benefits, barriers, and facilitators of participation in an 8-week culturally grounded community-based mindfulness program for the Latino immigrant population in the United States. Results from the study show that these types of programs hold promise for improving wellbeing and reducing levels of stress among this population group. Given the high levels of stress, discrimination and marginalization currently being experienced by the Latino population in the United States, culturally grounded community-based mindfulness programs such as this one are granted.

1. Introduction

Stressors Facing Latinos

While numerous stressors have been noted in the scientific literature to be relevant for Latinos, a most prominent one and most germane to our study concerns acculturative stress, which refers to the challenges that immigrants endure before, during, and after migration (Berry, 2006; Caplan et al., 2007; Cervantes et al., 2015). Acculturative stressors contribute to health declines among Latinos residing in the U.S., regardless of their country of origin (i.e., both U.S.-born and foreign-born Latinos) and concern experiences with a wide range of factors (Cervantes et al., 2015). These stressors can include intergenerational acculturation gaps among parents and children, differences in acculturation between romantic partners, language barriers, pre-migration stress precipitating migration (e.g., being forced to leave one’s country due to poverty or violence), and most importantly the high level of hostility demonstrated by the receiving country, particularly under the current political environment (Vargas et al., 2021; Vos et al., 2021). Furthermore, limited access to health care (often due to migratory/legal status), and limited English proficiency (Austin, 2001), can also play critical roles.

A preponderance of research has demonstrated that acculturative stressors are linked to poor physical health outcomes including increased allostatic load, inflammatory biomarkers, and stress hormones (Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2021). Additionally, these stressors have been associated with mental health issues (Maldonado, 2018) such as a heightened risk of depression (Mendelson et al., 2008) anxiety (Alegria et al., 2008; Wassertheil-Smoller et al., 2014; Torres, 2010) and sleep disorders (Redline et al., 2014; Zhan et al., 2022). They also contribute to other poor health-related quality of life outcomes (Cavazos-Rehg et al., 2007; Garcini et al., 2018a; Garcini et al., 2017a; Garcini et al., 2017b; Garcini et al., 2018b). Latino immigrants living in the U.S. are particularly at risk of presenting poor sleep outcomes; they are 2.7 times more likely to be short sleepers (<5 hrs.) compared to non-Latino Whites, even after adjusting for socioeconomic factors (Whinnery et al., 2014). Sleep deprivation has been linked to adverse cardiovascular disease outcomes including high blood pressure, obesity, diabetes, poor quality of life, all-cause mortality, and safety risks while driving and operating machinery (Cappuccio et al., 2010; Chanchlani, 2017; Grandner et al., 2016; Greer, Goldstein, & Walker, 2013; Itani et al., 2017; Spiegel et al., 2009; Yin et al., 2017). Factors that increase risk and likelihood for sleep deprivation (Alcántara et al., 2017; Redline et al., 2014) among Latino immigrants include acculturative stress (Austin, 2001; Averett, Smith, & Wang, 2018; Sarkar et al., 2016; Urzúa et al., 2021; U.S. Census Bureau., 2019.), systemic oppression, cultural bias, discrimination, anti-immigrant rhetoric/policies (Salas-Wright et al., 2015), and the COVID-19 pandemic (Rodriguez-Diaz, et al., 2020). This phenomenon is concerning and warrants urgent scientific inquiry given not only Latino immigrants’ wide sleep outcome disparities but also the fact that they are understudied and underrepresented in most research on health (Ford et al., 2013), well-being (Waheed et al., 2015), and sleep (Loredo et al., 2010).

The challenges discussed above are especially pernicious, as they not only contribute to significant sources of stress for Latinos, but also limit their upward social mobility (Assari, 2018) and their social, economic and cultural integration into mainstream culture. They act as barriers to effective stress management and emotional well-being solutions, which are more readily available to non-Hispanic Whites, including mainstream mindfulness and yoga programs and interventions (Mendoza et al., 2018). In other words, these adverse social drivers of health contribute to the persistent health inequities experienced by Latinos in the U.S.

Mindfulness as a Strategy to Target Stress in Latinos

Mindfulness, defined as “bringing deliberate and non-judgmental awareness and attention to one’s present moment experience” (Kabat-Zinn, 1982) has roots in ancient Buddhist traditions, where it is seen as a necessary component for the cessation of suffering (Kabat-Zinn, 1982). In recent years, mindfulness has become increasingly integrated into health and wellness practices through mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs). MBIs are group-based training programs that focus on mindfulness meditation to enhance overall well-being. MBIs specifically target cognitive and behavioral aspects associated with stress reduction and the reframing of intrusive and worrisome thoughts. MBIs can effectively decrease stress and improve health outcomes among underrepresented populations (Abercrombie et al., 2007; Falsafi & Leopard, 2015; Green et al., 2012; Hinton et al., 2009; Raines et al., 2018; Roth & Creaser, 1997; Roth & Stanley, 2002; Ryan et al., 2018; Spears et al., 2015; Tran et al., 2014; Woods-Giscombe & Black, 2010; Zvolensky et al., 2015). Studies on mindfulness among Latinos have demonstrated reductions in depression and anxiety symptoms (Mendelson et al., 2008; Torres, 2010). However, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of cultural adapted MBIs for Latino populations highlighted the need for more rigorous and methodologically robust studies (Castellanos et al., 2019).

When culturally adapted, MBIs have the potential to address the challenges faced by Latino immigrant populations, they can be delivered requiring little to no financial investment, traditional formal education or English proficiency, and can be conveniently practiced at home in a secular nature (Cavanagh et al., 2014; Duarte et al., 2019; Lloyd et al., 2018; Sevilla-Llewellyn-Jones et al., 2018; Toivonen et al., 2017). In spite of this, the scientific literature points to a significant challenge: Latinos exhibit remarkably lower engagement rates in any type of mindfulness practice (e.g., meditation, yoga, tai chi, and qigong) compared to other ethnic minority groups (Clarke et al., 2018; Olano et al., 2015). This challenge emphasizes the urgent need for intervention studies conducted in real-world, community-based settings that prioritize determining intervention feasibility and addressing the specific barriers faced by Latino immigrants in accessing health resources like MBIs. To this end, Nagy et al. (2022) have made a compelling call to action, outlining concrete steps for the mindfulness field to be more inclusive of Latino individuals, summoning to increase representation of the Latino population in mindfulness-based research, enhancing the scientific rigor, as well as developing a more diverse workforce. Recent statistics reveal a notable increase in the use of complementary health approaches, such as participation in yoga and meditation. The practice of mindfulness rose significantly from 7.5% in 2002 to 17% in 2022 making it one of the most popular complementary health approaches in the U.S., alongside yoga (Nahin et al., 2024), specific information for Latino ethnicity is limited (Black et al., 2016; Campbell et al., 2009). Therefore, it is necessary to increase the accessibility of these types of programs and offerings in a culturally grounded manner that considers the characteristics and context of the community.

The goal of this culturally grounded, community-based mindfulness program for Latino immigrants aimed to introduce the concept of mindfulness. It intended to teach participants specific tools that they could integrate into their daily life to manage salient stressors and the added uncertainty from the COVID-19 pandemic, occurring at the time of the initial intervention, as well as the current political and social environment in the U.S. (American Psychological Association, 2019). The program consisted of an 8-week online curriculum, with each weekly session lasting 1.5-hours, delivered over four waves between the fall of 2020 and winter of 2022. The sessions were led by a Spanish-speaking trained yoga and mindfulness facilitator (who was also the Principal Investigator) at a community center in St. Louis, MO. It is worth mentioning that the Latino immigrant population in this region is experiencing growth, standing at 4%, but remains marginalized as they are not included in the mainstream job market or economic growth (Onesimo Sandoval, 2014). The purpose of this study was to qualitatively and quantitatively explore the benefits, barriers, and facilitators of participation in a culturally grounded, community-based and trauma sensitive mindfulness program aimed at reducing stress, improving wellbeing, and sleep outcomes among Latino immigrants.

2. Materials and Methods

This Institutional Review Board-approved study (protocol # 202110126), used an exploratory sequential multi-method design (QUAL – quant) where qualitative data was collected and analyzed and then results were followed with a quantitative phase informed by the first phase (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Keyworth et al., 2014).

Culturally grounded community-based mindfulness program.

The principal investigator (PI) of this study (DCP) is a yoga and mindfulness teacher, and native Spanish speaker from Colombia. The PI developed and delivered the culturally grounded, community-based mindfulness program following a similar structure as the Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program created by Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn in 1982 (Kabat-Zinn, 1982). The curriculum integrated mindfulness meditation, body awareness, and gentle yoga to cultivate nonjudgmental present-moment awareness and reduce stress, pain, and psychological distress. The curriculum included a trauma-sensitive approach (Treleaven, 2018) that was specifically related to the immigration experience (See Appendix I for an outline and short description of the sessions). Each week’s curriculum was designed to build upon the previous week’s content while remaining independent. This approach fostered flexibility, accommodating participants who might miss a class and allowing them to revisit missed classes through recorded sessions.

The adapted curriculum embedded core MBSR principles and practices within a culturally responsive and didactic framework informed by seminal work in this field (Parker, 2020). Informed by prior iterations of the program and by feedback received from prior participants as well as scientific evidence gathered through implementation studies some key modifications to the curriculum were implemented (Clarke et al., 2022; Lu et al., 2021; Nagy et al., 2022; Ornelas et al., 2025; Tobin, et al., 2021). These modifications included (1) delivering all instruction in participants’ native Spanish language; (2) emphasizing and encouraging connections between mindfulness practices and participants’ personal religious beliefs (e.g., “connecting the breath/body to God”), (3) incorporating culturally unique experiences into group activities and exercises (e.g., sharing immigration stories and examining how alterations in perspective can influence meaning and emotions), and (4) adding a more familial focus to course content (e.g., highlighting how certain skills or practices can benefit the family). In addition to class attendance, participants were further asked to complete homework assignments and engage in daily practice of mindfulness and meditation at-home (ranging from 5 minutes in the first class to 40 minutes by the end of the course), with access to guided audio and video instructions recorded by the principal investigator. For example, the homework following the second session focused on journaling about participants’ experience of immigrating to a new country, encouraging them to rewrite their stories from a strengths- and resilience-based perspective using the approach described in the book “Pertenaecer” by Criss Cuervo (Cuervo, 2019).

The restorative yoga practices from session three were based on the techniques outlined in the book “Restorative Yoga for Ethnic and Race-Based Stress and Trauma” by Gail Parker (Parker, 2020). Previous to implementation, the curriculum also received expert feedback by the teaching faculty of the Engaged Mindfulness Institute (EMI), where the PI received her mindfulness training. EMI focuses on trauma-informed mindfulness as a key skill for resilience and specializes in training people to bring mindfulness to underrepresented populations (Engaged Mindfulness Institute). One distinguishing feature of the mindfulness program from this study was the intentional integration of trauma-informed and trauma-sensitive principles into the curriculum. This approach consistently offered participants with multiple options and modifications during sessions, such as allowing for open eyes during meditation, incorporating gentle movements, maintaining spatial awareness, and fostering an empowered sense of agency.

The curriculum was delivered through an 8-week online course with a maximum of 25 participants in each session. The curriculum was delivered across four waves starting in 2020. The first wave took place in July-August in person with 10 participants, following COVID-19 public health protocols. The second concurrent wave also took place in July-August but was conducted online through Zoom with 12 participants. The third wave occurred in April-May 2021 with 24 people, and the fourth wave took place in November-December 2021 with 25 participants, both were conducted through Zoom.

Qualitative Data

Sample. Three bilingual (English and Spanish) and bicultural female research assistants (RAs) conducted the semi-structured focus group interviews (supplemental file 1) between Spring 2022 and Spring 2024. The first four focus groups were conducted with former participants who took part in the mindfulness program between Fall of 2020 and Fall of 2021 (n=17), each focus group had between 4 and 6 participants. The last two focus groups (n=12) were conducted with participants who attended the mindfulness program delivered in the Spring of 2024, each focus group had 6 participants.

Procedure. During the first and introductory call, the study team introduced themselves and the study’s purpose, verified the participants’ inclusion criteria, read the consent form to the participants and encouraged them to ask questions if they had any. Then, if they agreed to participate, the study team scheduled an hour appointment for the focus group. The study team sent messages to participants one day before the focus group and one hour before the scheduled time, reminding them of the upcoming session. All interactions with the participants were conducted in Spanish. At the beginning of the focus group session, they asked if they had any questions on the consent form, then obtained verbal consent from the participants and asked their permission to record their session. The focus groups lasted around one hour and fifteen minutes and were conducted virtually over Zoom.

Data collection. Participants were recruited using a snowballing sampling approach in partnership with a community health organization that provides a wide array of healthcare services including psychosocial support. To recruit participants, the study team reached out to former program attendees via phone or email. They provided a description of the study and invited them to take part in a focus group.

Qualitative Analysis Methods. We performed deductive analysis using Dedoose with initial and open coding to identify emerging ideas and interpret the data using codes, subcodes, categories, sub-categories, themes/concepts, and finally developing theory/assertions. Audio recordings for all six focus groups were sent to a transcription company. Research assistants reviewed transcripts for errors and made corrections. The edited transcripts were then uploaded onto Dedoose for analysis. A draft codebook was developed by one research assistant using deductive analysis of two transcripts. This codebook was then presented to the research team for approval. Once approved, a second research assistant joined coding efforts after establishing inter-rater reliability (IRR) of 1. The research assistants continued to check IRR as coding progressed with scores ranging from .8 - 1. Edits to the codebook were made only after consulting with the research team. The interviews, recordings, and transcripts were all in Spanish. The codebook was written in English and text excerpts were translated into English for the purposes of this article.

Qualitative Rigor and Reflexivity. The study team consisted of the PI, two Research Assistants (RAs), one of whom was a third-year doctoral student in social work and the other a master’s student in social work, and one consultant. 4 members of the team self-identified as Latinas, 2 as immigrants, and 3 were Native Spanish-speakers. 4 members of the research team self-identified as women. All of the research team members had prior experience with qualitative research. The focus groups were facilitated by 3 and the coding was done by 4. To ensure methodological rigor and to establish trustworthiness, the research team followed the guidelines established by Guba and Lincoln (1985). In line with the idea of credibility (truth of findings), the research team met routinely during the course of the study to discuss potential sources of bias and how the identities of the research team informed the interpretations made. Furthermore, the other function of these meetings was to address any questions or issues that arose during the focus group sessions. Dependability (consistency of results) was ensured by having a systematic and consistent data collection approach. Before data collection, the PI met with the study team to discuss the study protocol, a detailed consent form, review the interview guide, and make sure that they followed all necessary steps before, during, and after the data collection period. Transferability (application to other contexts, settings, or populations) is achieved by providing a detailed description of the study sample, settings, and results of this study.

Quantitative Data.

Sample. Quantitative data was collected only from the second cohort in 2024 due to funding restrictions, in addition we selected specific quantitative measures based on the results from the qualitative findings from cohort one (n=17). Pre and post data in the second cohort was taken using the measures described below.

Procedure. Several scales measuring resilience, stress, acculturative stress, mindfulness awareness, and sleep outcomes were utilized. Pre- and post- measurements through REDcap (Garcia & Abrahão, 2021) were delivered before and after the mindfulness program that took place in the Spring of 2024.

Measures.

Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10): The CD-RISC-10 (Connor & Davison, 2025) assesses an individual’s capacity to cope with stress, adversity, and challenging situations. It consists of 10 items, each rated on a 5-point Likert scale, measuring different aspects of resilience. A higher total score indicates greater resilience. The scale has demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha; α) and test-retest reliability, and shown to have good construct validity, meaning it accurately measures the intended construct of resilience, and is correlated with other measures of well-being. The total score is obtained by adding up all 10 items. The total ranges from 0 to 40. Higher scores suggest greater resilience and lower scores suggest less resilience, or more difficulty in bouncing back from adversity. Population scores for the CD-RISC-10 have been obtained from two U.S. communities, which have yielded mean scores of 32.1 and 31.8. (Connor & Davison, 2025)

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10): The PSS-10 (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983) is a tool for measuring psychological stress. It is a self-reported questionnaire that was designed to measure the degree to which situations in one’s life are appraised as stressful. Reverse scale is applied to 4 of the 10 questions and individual scores on the PSS can range from 0 to 40 with higher scores indicating higher perceived stress. Scores ranging from 0-13 would be considered low stress, from 14-26 would be considered moderate stress, and from 27-40 would be considered high perceived stress. The reliability and validity of this scale was presented by evidence from three samples, two of college students and one of participants in a community smoking-cessation program. The PSS showed adequate reliability and as predicted, was correlated with life-event scores, depressive and physical symptomatology, utilization of health services, social anxiety, and smoking-reduction maintenance. The PSS was a better predictor of the outcome in question than were life-event scores. It was found to measure a different and independently predictive construct when compared to a depressive symptomatology scale. The PSS is suggested for examining the role of nonspecific appraised stress in the etiology of disease and behavioral disorders and as an outcome measure of experienced levels of stress. (Cohen et al., 1983)

NLAAS Acculturative Stress Questionnaire: This study used the Acculturative Stress questionnaire developed in the National Latino Asian American Study (NLAAS), the first nationally representative community household survey of Asian and Latin Americans conducted between May 2002 and December 2003 (Alegria et al., 2004). Acculturative Stress is defined by the sum of nine items designed to measure the stress felt as a result of adapting one’s own culture with a host culture. Each item had dichotomized responses (yes = 1 or no = 0). All items were summed, with higher values representing higher acculturative stress (α=0.67). The nine items for acculturative stress are: 1. felt guilty about leaving family/friends in the country of origin, 2. avoided health service due to fear of immigration officials, 3. felt the same respect in the U.S. as in country of origin (reverse coded), 4. had limited contact with family and friends, 5. had difficult interactions due to difficulty with English language, 6. was treated badly due to poor or accented English, 7. had difficulty finding work due to Latino or Asian descent, 8. was questioned about legal status, and 9. perceived deportation by going to a social or government agency. (Sunget al., 2018)

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS): The MAAS; (Brown et al., 2011) was used to evaluate quality of consciousness and well-being associated with increased self-awareness. The 15-item measure uses a 6-point scale to ask participants how often they experience mindful thinking and awareness, with response options ranging from 1 (“Almost always”) to 6 (“Almost never”). A translated version of this scale has been previously used in Spanish-speaking community settings. (Tejedor et. al., 2014, Soler et. al., 2012) Each statement on the assessment relates to the mindfulness concept of present-moment awareness. If someone scores a higher number on this assessment, it means that a person has a higher degree of dispositional mindfulness. This means that these individuals can be more likely to self-reflect and be receptive to their internal state and external environment consciously. If someone has a MAAS score on the lower side, it can mean they are less likely to self-reflect and pay attention mindfully. If someone has a higher degree of dispositional mindfulness, they are likely more proficient at utilizing present moment awareness as it relates to their internal state, external environment, and relationships with others. The MAAS showed acceptable psychometric properties in terms of validity and reliability. The scale obtained an adequate convergent validity with the Five Facets Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) and good discriminating validity with relation to depressive symptoms. Additionally, it had good reliability indexes (Cronbach’s α = 0.89, between 0.71 and 0.91) and replicates the original single-factor structure accounting for 42.8% of the total variance. These results were comparable to those obtained by the original English version of the scale. (Soler et. al., 2012, Tejedor et. al., 2014)

Women’s Health Initiative Insomnia Rating Scale (WHIIRS): The WHIIRS (Levine et al., 2003, 2005) is a brief, five-item questionnaire used to assess insomnia symptoms in postmenopausal women. It’s a self-report measure that asks about the frequency of specific sleep problems over the past four weeks, such as difficulty falling asleep, night waking, early morning awakening, and overall sleep quality. A higher score on the WHIIRS indicates a greater frequency of sleep problems. Scoring questions one through four are answered using a five-point, Likert-type scale (0 means that the problem has not been experienced in the past 4 weeks, while four denotes a problem that occurs at least five times a week). Respondents indicate how often they have experienced certain sleep difficulties over the past month, with higher scores denoting higher frequencies. Question five asks individuals to rate the quality of their sleep on a typical night. Total scores will fall between 0 and 20. Though no specific cutoff has been recommended, Levine and colleagues suggest that a .5 standard deviation difference in mean scores on the WHIIRS between two treatment groups may indicate a significant difference. Levine et. al., performed several studies to determine validity and reliability of the WHIIRS scale. In one of the studies, reliability of the WHIIRS was estimated using a resampling approach where the mean alpha coefficient was .78. After administering the scale that day, test-retest reliability coefficients were 0.96 and, after administering a year later, they were 0.66. Correlations between the WHIIRS scale and other measures of related constructs were expected and therefore demonstrate validity and an acceptable internal consistency.

Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS): The ESS is a self-administered questionnaire with 8 questions. Respondents are asked to rate, on a 4-point scale (0-3), their usual chances of dozing off or falling asleep while engaged in eight different activities. The ESS score (the sum of 8 item scores, 0-3) can range from 0 to 24. The higher the ESS score, the higher that person’s average sleep propensity in daily life (ASP), or their ‘daytime sleepiness’. The questionnaire takes between 2 and 3 minutes to answer and it is available in various languages. Validity and reliability of this scale is supported by a study in a sample of twenty-five poor sleepers from a university population and is proposed as an important tool for diagnosis of sleep problems. A test-retest of 0.86 displays good reliability. (Veqar & Hussain, 2018)

Statistical Methods: Means and standard deviations were computed for the pre- and post-measures. Because of the small sample size (n=17), non-parametric statistics were applied to the data. Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test (t-test paired two samples for means comparisons baseline to end of treatment) (Rosner, Glynn, & Lee, 2006) was conducted for self-report measures, NLAAS Acculturative Stress, CD-RISC-10, PSS-10, MAAS, WHIIRS, and ESS.

3. Results

Participant Characteristics

The participants in this multi- method study (n= 29), consisted of former attendees of a culturally grounded and trauma informed, community-based mindfulness program. They were community members over the age of 18 who frequented a community center in St. Louis, MO. All participants had migrated to the United States within the past 21 years, with the exception of a U.S.-born participant, and were native Spanish speakers. The data collection involved six focus groups. The first cohort (

n=17) was done in 2022. The second cohort (n=17 in total for quantitative component and 12 of those for the qualitative component) was done in 2024. All individuals were women with the exception of one man, ranging in age from 21 to 54 years, with an average age of 39.7 years. Of the participants, 12 (41%) were married and 24 (83%) had children living at home. All the participants resided in the St. Louis, MO area (see

Table 1 for participants’ demographic characteristics).

Qualitative Data Analysis

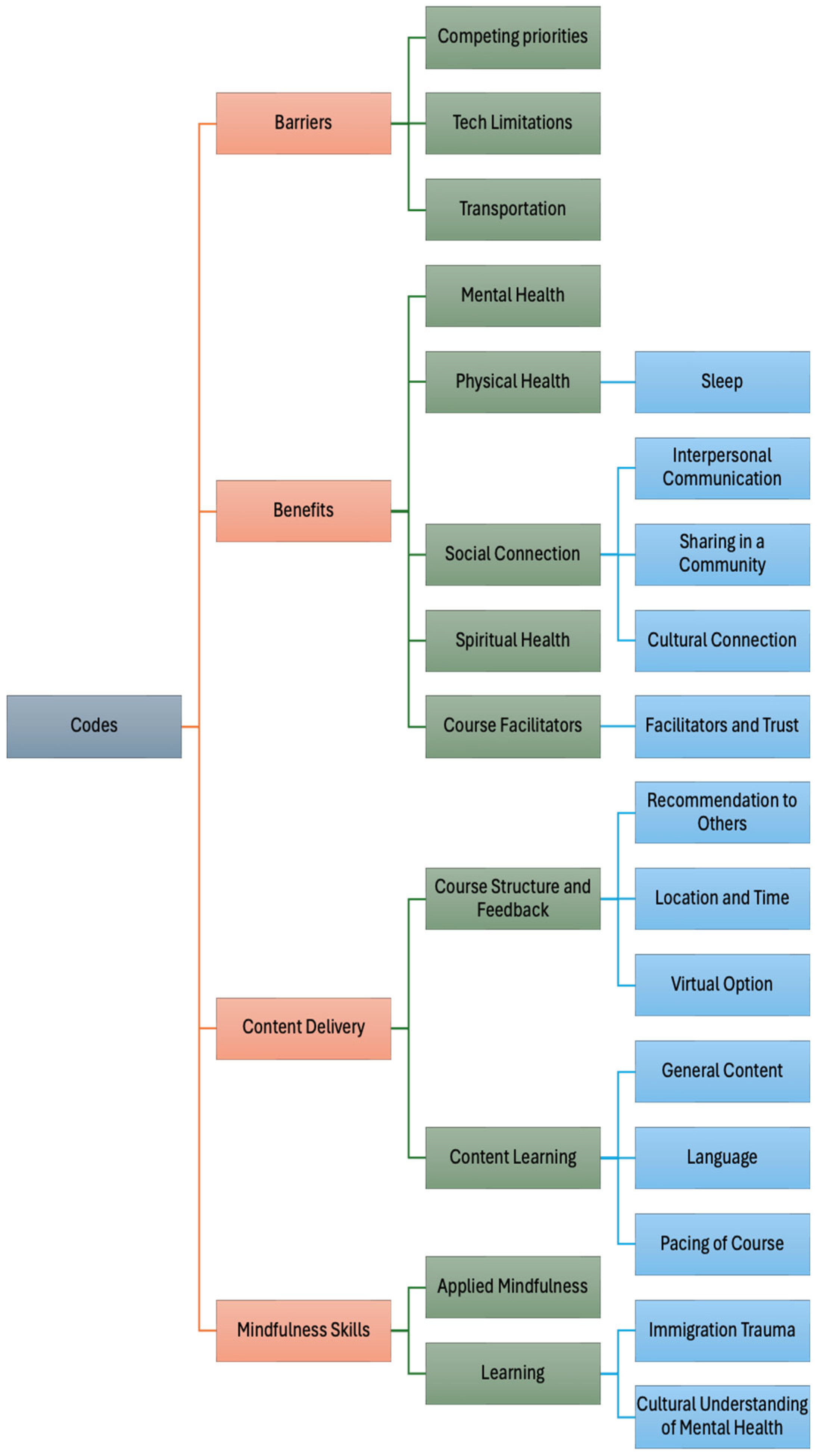

Using deductive coding we identified four major categories, themes and sub-themes as follows: 1.

Barriers (Competing Priorities, Technology Limitations, Transportation), 2.

Benefits (Mental Health, Physical Health (Sleep), Social Connection (Interpersonal Communication, Sharing in Community, Cultural Connection), Spiritual Health, 3.

Content Delivery (Course Facilitators, Course Structure/Feedback (Location and Time, Virtual Option, Recommendation to Others), Content Learning (General Content, Language, Pacing of Course), and 4.

Mindfulness Skills (Applied Mindfulness) and Learning/Knowledge (Immigration Trauma & Cultural Understanding of Mental Health). (See

Figure 1).

Each of the themes and subthemes established had a series of excerpts, or quotes referring to them (Appendix II). They emphasize specific circumstances in which participants applied mindfulness techniques, provided their opinions on language used in the course, or how their mental health and sleep was drastically improved. The incorporation of the immigration story exercise proved to be transformative, as expressed by one participant.

The three largest (most mentioned) codes were: Improved Mental Health, Applying Mindfulness Techniques, and General Content/Feedback.

Improved mental health. Defined as expressing ways in which mindfulness has decreased negative feelings and experiences. Better managing stress and anger after the mindfulness program were the most mentioned by participants (n=14). A reference to feeling calmer, feeling less depressed, better anxiety management, and living in the present moment were mentioned several times (n= 6-8). Other comments on feeling less guilt, less preoccupied, improving their sleep, and changes in personality were also mentioned a few times (n= 2-5). Some topics were mentioned only one time. (See

Table 2. Improved Mental Health Highlights).

Applying mindfulness techniques. Defined as examples of using skills learned in the course outside the classroom. From the examples of the techniques mentioned below, increased focus and attention as well as experiencing more relaxation were the most common (

n= 16-19). Techniques such as mindful eating and better breathing were mentioned several times (

n= 13-14). Other comments about the techniques applied refer to giving themselves more time and exercising more (

n=9). Topics on gratitude, writing, and meditation being hard were mentioned the least (

n= 2-3) (See

Table 3. Applying Mindfulness Techniques Highlights).

General content. is described as reflections or suggestions regarding which features of the course should be enhanced and what the instructor should pay special attention to. Within all six focus groups all participants highlighted that they would take the course again. Several participants mentioned they wouldn’t change anything from the course, that they loved it, and that all sessions were interesting and important to them (n= 5-9). A few remarks on having an outdoor class, a more individual experience, positive comments on the walking meditation, more yoga time and more focus on spirituality were suggested (

n= 2-3) (See

Table 4. General Content/Course Feedback Highlights).

Benefits and Barriers. “I feel the benefits of the course” was mentioned by seventeen participants within all six focus groups within the three largest codes. Among the most common mentioned barriers (Competing Priorities) were, conflicts with the schedule, childcare, other classes, other meetings, running errands, work, church, household chores, technology limitations (slow internet), and lack of transportation. Most people agreed on having an 8-8:30 pm course because of their multiple activities during the day. Several mentioned how convenient the virtual option was; however, a few would prefer in-person because of a closer connection and sharing the class in community. Many participants referred to a trustworthy facilitator (PI) leading to the effectiveness of the course.

Quantitative Data Analysis

Quantitative results (see

Table 5) demonstrated that there was a significant increase in the measures of resilience from baseline to end of treatment (Baseline

M = 24, standard deviation [SD] = 7, Post

M = 27, SD = 7; t-test= -2.816, p < 0.01). On average, participant test scores of resilience increased by 3 points, with four participants (24%) showing enough improvement to cross into a higher quartile of resilience. The change in individual total scores ranged from a loss of 4 points to an increase of 13 points. As a group, the aspects of resilience with greatest growth were self-efficacy (+23) and optimism (+14).

At the end of treatment, there were significant reductions on perceived stress (Baseline M = 19, standard deviation [SD] = 7, Post M = 14, SD = 7; t-test= 3.307, p < 0.01). Seventy-six percent of participants (13 out of 17) reported a lower score of perceived stress during their post-test. In 35% of the participants (6 out of 17), this decrease was significant enough to lower their stress level. Thirty percent of participants (5 out of 17) decreased their reported stress level from moderate to low. Six percent of participants (1 out of 17) decreased in stress levels from high to moderate stress. Six percent of participants (1 out of 17) reported no change, while eighteen percent (3 out of 17) scored higher stress scores on the post-test.

Before their participation in the program 59% of participants (10 out of 17) reported not feeling as respected in the U.S. as they did in their country. Fifty-three of participants (9 out of 17) felt living outside their country of origin had limited their contact with family and friends and fifty nine percent of participants (10 out of 17) struggled to interact with others due to a language barrier. The percentage of participants who felt they were not as respected in the United States as they were in their home country rose from 59% (10 participants) to 71% (12 participants) post intervention. The percentage of participants who reported feeling guilty for leaving friends and family in their home country decreased from 35% (6 participants) to 24% (4 participants).

Additionally, there was a statistically significant increase on the MAAS suggesting an increase in mindful states in day-to-day life (Baseline M = 56, standard deviation [SD] = 15, Post M = 66, SD = 14; t-test= -4.532, p < 0.01).

The average number of hours of sleep reported by participants (n=16) increased from 6.5 hours in the pre-test to 7 hours during the post-test. Forty-four percent of participants (7 out of 16) reported no change in their average hours of sleep. One individual reported being a caretaker and explained some of her sleep habits depended on her caretaking duties that night. The average pre-test score for WHIIRS was 10, while the average post-score was 7. The higher the score the greater number of sleep difficulties experienced. Seventy-six percent participants (13 out of 17) reported a decrease in frequency of sleep difficulties post intervention. The number of participants who reported experiencing any trouble falling asleep decreased by thirty-five percent (6 out of 17) post intervention. Thirty-five percent of participants (6 out of 17) stopped waking up in the middle of the night post-intervention. Twenty-four percent of participants (4 out of 17) stopped waking up earlier than planned post-intervention. Twenty-four percent of participants (4 out of 17) stopped having trouble going back to sleep after waking up in the middle of the night post-intervention. The number of participants experiencing sound sleep increased by 18% (3 participants).

While the results from the Epworth Sleepiness Scale did not show significant changes, 41% of participants (7 out of 17) lowered their daytime sleepiness score. Twenty-four percent of participants (4 out of 17) reported no change in daytime sleepiness and 35% (6 out of 17) reported an increase in daytime sleepiness.

4. Discussion

The multi-method, qualitative and quantitative data collected in this study showed that the Mindfulness program was useful in reducing stress, improving wellbeing and improving sleep outcomes among participants. Results from the focus groups yielded positive and optimistic perspectives and participants were satisfied with the content of the course. Several individuals experienced increased benefits such as improved mental health (less depression, less stress and better anger management). The application of mindfulness techniques in daily life, such as practicing more focused attention while riding a bicycle or driving, feeling more relaxed, and mindful eating, were frequently mentioned.

Mindfulness has demonstrated effectiveness in treating depression, anxiety disorders, sleep disorders, and chronic pain management (Baer, 2003; Campbell et al., 2012; Evans et al., 2011; Gallegos et al., 2018; Gawrysiak et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2016; Jazaieri et al., 2012; Lao et al., 2016; Leung et al., 2015; Minor et al., 2006; Mohammed et al., 2018; Schmidt et al., 2015; Serpa et al., 2014; Simpson & Mapel, 2011; Zhang et al., 2018). While there is limited research on the application of mindfulness specifically in Latino populations (Castellanos et al., 2019), the existing findings offer a promising outlook. Notably, Roth & Stanley found improvements in health-related quality of life (Roth & Stanley, 2002), mindful attention awareness, self-compassion, perceived stress, depression (Edwards et al., 2014) life satisfaction (Neece, 2014) and reduced post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms (Viana et al., 2017). Moreover, prior research has indicated that mindfulness-based programs are feasible and well received in Latino populations (Cotter & Jones, 2020).

In this study, the developed curriculum demonstrated a sensitive approach tailored to the unique social and environmental challenges faced by Latino immigrants residing in St. Louis. The curriculum was also exclusively delivered in Spanish by a native Spanish speaker to accommodate Latino immigrants’ particular needs and increase a sense of safety and belonging for the participants. Furthermore, by focusing specifically on Latino immigrants attending community centers, which are in many cases the population’s only point of entry to healthcare and mental health care services utilization (Sarkar et al., 2016), this program unraveled critical insights into surmounting community-level barriers that traditionally impede engagement with conventional healthcare models. This community-based approach marks a significant step toward fulfilling the pressing demand for interventions conducted in real-world settings, where the socioeconomic constraints faced by Latino immigrants are duly recognized as integral factors in the pursuit of effective, evidence-based practices. To this end, community-based and culturally grounded mindfulness programs may emerge as a cost-effective means to address mental health problems in primary care (Ortiz et al., 2019).

The incorporation of participant feedback facilitated program refinement, reflecting their preferences and perceived needs. This approach, informed by evidence and previous recommendations (Cuervo, 2019; Kabat-Zinn, 1982; Parker, 2020) also directly addressed a common barrier to Latino retention in mindfulness programs, particularly time constraints. The six focus groups encountered similar barriers that hindered their participation in the program. These barriers included: (1) limited childcare, completing household chores and other social and family activities; (2) not having access to a mobile data plan, or having a low-quality phone; (3) work obligations; and (4) not having a private or quiet space to practice. The only discrepancy between focus groups 1 (i.e., those who attended five and six sessions or less) and 2 (i.e., those who attended more than six sessions), was that group 1 identified the timing of the course, which was delivered in the evening around 6 p.m., as a barrier to their participation, and preferred later times during the day.

Participants from all six focus groups self-reported various perceived benefits across physical, social, mental, and spiritual aspects. These benefits included improved sleep; weight loss; a stronger immune system; better management of chronic pain and migraines; improved digestion; enhanced relaxation; a greater sense of connectedness with others; improved relationships; increased self-love, resilience, hope, and self-esteem; and reduced stress, fear, depression, and anxiety; as well as the ability to manage difficult emotions such as anger. Many participants found the immigration stories exercise to be liberating, shedding the weight of past traumas, and unlocking a newfound sense of purpose and resilience.

The most significant facilitator reported was the free access to classes via Zoom. In terms of motivators, both groups identified intrinsic motivators such as feeling better, calmer, and more centered, as well as extrinsic motivators such as the opportunity to share in a group setting and receive support from other participants with a shared lived experience. The facilitator’s soft voice and established rapport with the Latino community stemming from several years of teaching gentle yoga at the community center, significantly enhanced participant engagement. This connection played a pivotal role when difficult emotions surfaced after practices, specifically during the immigration stories and experiences. This exercise allowed participants to reflect on their life experiences, release past burdens, and embrace a new narrative. The strategic avoidance of terms with religious connotations or Sanskrit terms common in yoga and mindfulness classes further ensured accessibility and cultural sensitivity (Nagy et al., 2022).

All quantitative measures with the exception of the ESS and the acculturative scale were statistically significant. There was a significant increase in the measures of resilience from baseline to end of treatment. On average, participant test scores of resilience increased by 3 points, with the greatest increase in the subcomponents of self-efficacy and optimism. A review of Latino/Latinx participants in Mindfulness-Based intervention research found that only one study assessed resiliency, thus results from this study contribute to the evidence around this topic. These findings are of particular relevance and importance given the current circumstances being faced by the Latino community in the U.S. and are similar to findings by other authors in this area (Oh, Sarwar, & Pervez, 2022; Ortiz, 2015).

At the end of treatment, there were significant reductions on perceived stress. Cotter & Jones’s (2020) review found that nine studies examined stress and seven of them found significant reductions in perceived stress post-program. These findings strengthen the importance of these types of interventions in light of the current levels of stress experienced by Latino immigrants in the United States.

While individual levels of acculturative stress did not change significantly post intervention, each of the nine questions resulted in a different distribution of answers post-intervention. One interpretation is that while the intervention was not associated with a decrease in acculturative stress, it did invite a level of self-reflection across participants.

The statistically significant increase on the MAAS score is in accordance with those found in prior studies (Cotter et al., 2020; Zvolensky et al., 2015) and is an important finding that could be related and associated with the increased resilience and the lower perceived stress.

The average number of hours of sleep reported by participants increased from 6.5 hours to 7 hours after the program. The number of participants who reported experiencing any trouble falling asleep decreased by 35% post intervention. The number of participants experiencing any type of restless sleep decreased by half and the number of participants experiencing sound sleep increased by 18%. Traditional solutions to improve sleep (e.g., medication and behavioral interventions) are not always applicable, relevant, or accessible to Latino immigrants due to language and cultural barriers, as well as disparities in access to health care (Loredo et al., 2010). Participating in mindfulness programs improves sleep (Goyal et al., 2014; Kabat-Zinn, 1982; Rusch et al., 2019), however study of this topic has been limited to Non-Latino White populations (Huberty et al., 2021; Zheng et al., 2020). The current study helps address this gap and found that participation in this Mindfulness program improved sleep outcomes.

It is important to note that this study has limitations. The sample size was relatively small, and the findings may not be generalizable to all Latino immigrants, most of their origins were from Mexico (75%). A key challenge to generalizable clinical research is the systematic and consistent exclusion of Latinos compared to other ethnic minority groups, in addition to various types of mindfulness practice (e.g., meditation, yoga, tai chi, and qigong) (Clarke et al., 2018; Olano et al., 2015).However, this challenge only highlights the critical need for real-world, community-based programs where Latino immigrants’ barriers to health resources are prioritized and addressed in determining intervention feasibility. Future research should aim to include a larger and more diverse sample to ensure broader representation. Despite these limitations, this study contributes to the growing body of knowledge on mindfulness interventions for underrepresented and minoritized populations with a central focus on cultural considerations, equity, and empowerment to promote wellbeing and resilience among Latino immigrants. We consider this paper timely and crucial for immigrants to engage in health programs outside of traditional medical settings through trusted non-profit organizations due to the recent change in administration. By integrating cultural considerations, addressing barriers, and leveraging motivators, we can develop effective and sustainable programs that promote wellbeing and resilience among the Latino immigrant population in the U.S., taking an even larger significance now, given the hostile social and political environment. This study underscores the potential of culturally grounded, community-based mindfulness programs to meet the specific needs of Latino immigrant populations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Research in Implementation Science for Equity (RISE) program at UCSF and funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (5R25HL126146-06) through the Programs to Increase Diversity Among Individuals Engaged in Health-Related Research (PRIDE). NJPF was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [under Grant T32HL130357]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Special thanks to LifeWise and the participants of the program and to Karina Marin (RA2) for her contributions in data collection and earlier drafts of this manuscript.

References

- Abercrombie, P. D., Zamora, A., & Korn, A. P. (2007). Lessons learned: providing a mindfulness-based stress reduction program for low-income multiethnic women with abnormal pap smears. Holist Nurs Pract, 21(1), 26-34. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17167329.

- Alcántara, C., Patel, S. R., Carnethon, M., Castañeda, S., Isasi, C. R., Davis, S., Ramos, A., Arredondo, E., Redline, S., Zee, P. C., & Gallo, L. C. (2017). Stress and Sleep: Results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos Sociocultural Ancillary Study. SSM - population health, 3, 713–721. [CrossRef]

- Alegria, M., Canino, G., Shrout, P. E., Woo, M., Duan, N., Vila, D., Torres, M., Chen, C. N., & Meng, X. L. (2008). Prevalence of mental illness in immigrant and non-immigrant U.S. Latino groups. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(3), 359-369. [CrossRef]

- Alegria, M., Takeuchi, D., Canino, G., Duan, N., Shrout, P., Meng, X. L., & Gong, F. (2004). Considering context, place and culture: the National Latino and Asian American Study. International journal of methods in psychiatric research, 13(4), 208-220.

- Amaro, H., & Zambrana, R. E. (2000). Criollo, mestizo, mulato, LatiNegro, indígena, white, or black? The US Hispanic/Latino population and multiple responses in the 2000 census. American journal of public health, 90(11), 1724–1727. [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. (2019). Stress in America: Stress and Current Events. (Stress in America™ Survey). https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2019/stress-america-2019.pdf.

- Assari, S. (2018). Race, Intergenerational Social Mobility and Stressful Life Events. Behav Sci (Basel), 8(10), 86. [CrossRef]

- Austin, B. J. (2001). Cultural bias emerges in reported access to health care: commonly used measure may be inappropriate for non-English-speaking Hispanics. Find Brief, 4(4), 1-2. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12138925.

- Averett, S. L., Smith, J. K., & Wang, Y. (2018). Minimum Wages and the Health of Hispanic Women [journal article]. Journal of Economics, Race, and Policy, 1(4), 217-239. [CrossRef]

- Baer, R. A. (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology-Science and Practice, 10(2), 125-143. [CrossRef]

- Berry, J. W. (2006). Stress perspectives on acculturation. In D. L. Sam & J. W. Berry (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology (pp. 43–57). Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Black, D. S., Lam, C. N., Nguyen, N. T., Ihenacho, U., & Figueiredo, J. C. (2016). Complementary and Integrative Health Practices Among Hispanics Diagnosed with Colorectal Cancer: Utilization and Communication with Physicians. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, N.Y.), 22(6), 473–479. [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. W., West, A. M., Loverich, T. M., & Biegel, G. M. (2011). Assessing adolescent mindfulness: validation of an adapted Mindful Attention Awareness Scale in adolescent normative and psychiatric populations. Psychological assessment, 23(4), 1023–1033. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L. C. Andrews, N., Scipio, C., Flores, B., Feliu, M. H., & Keefe, F. J. (2009). Pain coping in Latino populations. The journal of pain, 10(10), 1012–1019. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, T. S., Labelle, L. E., Bacon, S. L., Faris, P., & Carlson, L. E. (2012). Impact of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) on attention, rumination and resting blood pressure in women with cancer: a waitlist-controlled study. J Behav Med, 35(3), 262-271. [CrossRef]

- Caplan S. (2007). Latinos, acculturation, and acculturative stress: a dimensional concept analysis. Policy, politics & nursing practice, 8(2), 93–106. [CrossRef]

- Cappuccio, F. P., D’Elia, L., Strazzullo, P., & Miller, M. A. (2010). Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep, 33(5), 585–592. [CrossRef]

- Castellanos, R., Yildiz Spinel, M., Phan, V., Orengo-Aguayo, R., Humphreys, K. L., & Flory, K. (2019). A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cultural Adaptations of Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Hispanic Populations. Mindfulness (N Y), 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, K., Strauss, C., Forder, L., & Jones, F. (2014). Can mindfulness and acceptance be learnt by self-help?: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mindfulness and acceptance-based self-help interventions. Clin Psychol Rev, 34(2), 118-129. [CrossRef]

- Cavazos-Rehg, P. A., Zayas, L. H., & Spitznagel, E. L. (2007). Legal status, emotional well-being and subjective health status of Latino immigrants. J Natl Med Assoc, 99(10), 1126-1131. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17987916.

- Cervantes, R. C., Fisher, D. G., Padilla, A. M., & Napper, L. E. (2015). The Hispanic Stress Inventory Version 2: Improving the assessment of acculturation stress. Psychological Assessment, 28(5), 509–522. [CrossRef]

- Chanchlani N. (2017). Health consequences of shift work and insufficient sleep. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 356, i6599. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, T. C., Barnes, P. M., Black, L. I., Stussman, B. J., & Nahin, R. L. (2018). Use of yoga, meditation, and chiropractors among U.S. adults aged 18 and over.

- Clarke, R. D., Morris, S. L., Wagner, E. F., Spadola, C. E., Bursac, Z., Fava, N. M., & Hospital, M. (2022). Feasibility, acceptability and preliminary impact of mindfulness-based yoga among Hispanic/Latinx adolescents. Explore (New York, N.Y.), 18(3), 299–305. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. [CrossRef]

- Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. T. (2025). Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). https://www.connordavidson-resiliencescale.com/about.php.

- Cotter, E. W., & Jones, N. (2020). A review of Latino/Latinx participants in mindfulness-based intervention research. Mindfulness (N Y), 11(3), 529-553. [CrossRef]

- Cuervo, C. (2019). PERTENÆCER: Eight-Week Mindfulness and Meditation Training and Practices for Latinx Immigrants in the United States.

- Creswell, J.W., & Creswell, J.D. (2018). Mixed methods procedures. In, Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed., pp. 213-246). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Duarte, R., Lloyd, A., Kotas, E., Andronis, L., & White, R. (2019). Are acceptance and mindfulness-based interventions ‘value for money’? Evidence from a systematic literature review. Br J Clin Psychol, 58(2), 187-210. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M., Adams, E. M., Waldo, M., Hadfield, O. D., & Biegel, G. M. (2014). Effects of a mindfulness group on Latino adolescent students: Examining levels of perceived stress, mindfulness, self-compassion, and psychological symptoms. . Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 39(2), 145–163. [CrossRef]

- Evans, S., Ferrando, S., Carr, C., & Haglin, D. (2011). Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and distress in a community-based sample. Clin Psychol Psychother, 18(6), 553-558. [CrossRef]

- Falsafi, N., & Leopard, L. (2015). Pilot Study Use of Mindfulness, Self-Compassion, and Yoga Practices With Low-Income and/or Uninsured Patients With Depression and/or Anxiety. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 33(4), 289-297. [CrossRef]

- Ford, M. E., Siminoff, L. A., Pickelsimer, E., Mainous, A. G., Smith, D. W., Diaz, V. A., Soderstrom, L. H., Jefferson, M. S., & Tilley, B. C. (2013). Unequal Burden of Disease, Unequal Participation in Clinical Trials: Solutions from African American and Latino Community Members. Health & Social Work, 38(1), 29-38. [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, A. M., Moynihan, J., & Pigeon, W. R. (2018). A Secondary Analysis of Sleep Quality Changes in Older Adults From a Randomized Trial of an MBSR Program. J Appl Gerontol, 37(11), 1327-1343. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, K. K. S., & Abrahão, A. A. (2021). Research Development Using REDCap Software. Healthcare informatics research, 27(4), 341–349. [CrossRef]

- Garcini, L. M., Pena, J. M., Galvan, T., Fagundes, C. P., Malcarne, V., & Klonoff, E. A. (2017a. Mental disorders among undocumented Mexican immigrants in high-risk neighborhoods: Prevalence, comorbidity, and vulnerabilities. J Consult Clin Psychol, 85(10), 927-936. [CrossRef]

- Garcini, L. M., Pena, J. M., Gutierrez, A. P., Fagundes, C. P., Lemus, H., Lindsay, S., & Klonoff, E. A. (2017b). “One Scar Too Many:” The Associations Between Traumatic Events and Psychological Distress Among Undocumented Mexican Immigrants. J Trauma Stress, 30(5), 453-462. [CrossRef]

- Garcini, L. M., Chirinos, D. A., Murdock, K. W., Seiler, A., LeRoy, A. S., Peek, K., Cutchin, M. P., & Fagundes, C. (2018a). Pathways linking racial/ethnic discrimination and sleep among U.S.-born and foreign-born Latinxs. J Behav Med, 41(3), 364-373. [CrossRef]

- Garcini, L. M., Renzaho, A. M. N., Molina, M., & Ayala, G. X. (2018b). Health-related quality of life among Mexican-origin Latinos: the role of immigration legal status. Ethn Health, 23(5), 566-581. [CrossRef]

- Gawrysiak, M. J., Grassetti, S. N., Greeson, J. M., Shorey, R. C., Pohlig, R., & Baime, M. J. (2018). The many facets of mindfulness and the prediction of change following mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). J Clin Psychol, 74(4), 523-535. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Guarda, R. M., Befus, D., Steigerwald, M., Stafford, A., Nagy, G. A., & Conklin, J. (2021). A systematic review of the physical health consequences of acculturation stress among Hispanics in the US. . Biological Research for Nursing, 23(3), 362-374.

- Goyal, M., Singh, S., Sibinga, E. M., Gould, N. F., Rowland-Seymour, A., Sharma, R., Berger,.

- Z., Sleicher, D., Maron, D. D., Shihab, H. M., Ranasinghe, P. D., Linn, S., Saha, S., Bass, E. B., & Haythornthwaite, J. A. (2014). Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA internal medicine, 174(3), 357–368. [CrossRef]

- Grandner, M. A., Alfonso-Miller, P., Fernandez-Mendoza, J., Shetty, S., Shenoy, S., & Combs, D. (2016). Sleep: important considerations for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Current opinion in cardiology, 31(5), 551–565. [CrossRef]

- Greer, S. M., Goldstein, A. N., & Walker, M. P. (2013). The impact of sleep deprivation on food desire in the human brain. Nature communications, 4, 2259. [CrossRef]

- Green, M. A., Perez, G., Ornelas, I. J., Tran, A. N., Blumenthal, C., Lyn, M., & Corbie-Smith, G. (2012). Amigas Latinas Motivando el ALMA (ALMA): Development and Pilot Implementation of a Stress Reduction Promotora Intervention. Calif J Health Promot, 10, 52-64. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25364312.

- Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. In: Newbury Park. CA: Sage.

- Hinton, D. E., Lewis-Fernandez, R., & Pollack, M. H. (2009). A Model of the Generation of Ataque de Nervios: The Role of Fear of Negative Affect and Fear of Arousal Symptoms. Cns Neuroscience & Therapeutics, 15(3), 264-275. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. P., He, M., Wang, H. Y., & Zhou, M. (2016). A meta-analysis of the benefits of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on psychological function among breast cancer (BC) survivors. Breast Cancer, 23(4), 568-576. [CrossRef]

- Huberty, J. L., Green, J., Puzia, M. E., Larkey, L., Laird, B., Vranceanu, A. M., Vlisides-Henry, R., & Irwin, M. R. (2021). Testing a mindfulness meditation mobile app for the treatment of sleep-related symptoms in adults with sleep disturbance: A randomized controlled trial. PloS one, 16(1), e0244717. [CrossRef]

- Itani, O., Jike, M., Watanabe, N., & Kaneita, Y. (2017). Short sleep duration and health outcomes: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Sleep medicine, 32, 246–256. [CrossRef]

- Jazaieri, H., Goldin, P. R., Werner, K., Ziv, M., & Gross, J. J. (2012). A randomized trial of MBSR versus aerobic exercise for social anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychol, 68(7), 715-731. [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (1982). An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen Hosp Psychiatry, 4(1), 33-47. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7042457.

- Keyworth, C., Knopp, J., Roughley, K., Dickens, C., Bold, S., & Coventry, P. (2014). A mixed-methods pilot study of the acceptability and effectiveness of a brief meditation and mindfulness intervention for people with diabetes and coronary heart disease. Behavioral medicine, 40(2), 53–64. [CrossRef]

- Lao, S. A., Kissane, D., & Meadows, G. (2016). Cognitive effects of MBSR/MBCT: A systematic review of neuropsychological outcomes. Conscious Cogn, 45, 109-123. [CrossRef]

- Leung, L., Han, H., Martin, M., & Kotecha, J. (2015). Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) as sole intervention for non-somatisation chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP): protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open, 5(5), e007650. [CrossRef]

- Levine, D. W., Kripke, D. F., Kaplan, R. M., Lewis, M. A., Naughton, M. J., Bowen, D. J., & Shumaker, S. A. (2003). Reliability and validity of the Women’s Health Initiative Insomnia Rating Scale. Psychological assessment, 15(2), 137–148. [CrossRef]

- Levine, D. W., Dailey, M. E., Rockhill, B., Tipping, D., Naughton, M. J., & Shumaker, S. A. (2005). Validation of the Women’s Health Initiative Insomnia Rating Scale in a multicenter controlled clinical trial. Psychosomatic medicine, 67(1), 98–104. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, A., White, R., Eames, C., & Crane, R. (2018). The Utility of Home-Practice in Mindfulness-Based Group Interventions: A Systematic Review. Mindfulness (N Y), 9(3), 673-692. [CrossRef]

- Loredo, J. S., Soler, X., Bardwell, W., Ancoli-Israel, S., Dimsdale, J. E., & Palinkas, L. A. (2010). Sleep health in U.S. Hispanic population. Sleep, 33(7), 962–967. [CrossRef]

- Lu, S., Huang, C. C., Cheung, S. P., Rios, J. A., & Chen, Y. (2021). Mindfulness and social-emotional skills in Latino pre-adolescents in the U.S.: The mediating role of executive function. Health & social care in the community, 29(4), 1010–1018. [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, A., Preciado, A., Buchanan, M., Pulvers, K., Romero, D., & D’Anna-Hernandez, K. (2018). Acculturative stress, mental health symptoms, and the role of salivary inflammatory markers among a Latino sample. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 24(2), 277–283. [CrossRef]

- Mendelson, T., Rehkopf, D. H., & Kubzansky, L. D. (2008). Depression among Latinos in the United States: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(3), 355-366. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, S., Armbrister, A. N., & Abraido-Lanza, A. F. (2018). Are you better off? Perceptions of social mobility and satisfaction with care among Latina immigrants in the U.S. Soc Sci Med, 219, 54-60. [CrossRef]

- Minor, H. G., Carlson, L. E., Mackenzie, M. J., Zernicke, K., & Jones, L. (2006). Evaluation of a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program for caregivers of children with chronic conditions. Soc Work Health Care, 43(1), 91-109. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, W. A., Pappous, A., & Sharma, D. (2018). Effect of Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) in Increasing Pain Tolerance and Improving the Mental Health of Injured Athletes. Front Psychol, 9, 722. [CrossRef]

- Nahin, R. L., Rhee, A., & Stussman, B. (2024). Use of complementary health approaches overall and for pain management by US adults. JAMA, 331(7), 613–615. [CrossRef]

- Nagy, G. A., Cuervo, C., Ramos Rodriguez, E. Y., Plumb Vilardaga, J., Zerubavel, N., West, J. L., Falick, M. C., & Parra, D. C. (2022). Building a More Diverse and Inclusive Science: Mindfulness-Based Approaches for Latinx Individuals. Mindfulness (N Y), 13(4), 942-954. [CrossRef]

- Neece, C. L. (2014). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for parents of young children with developmental delays: implications for parental mental health and child behavior problems. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil, 27(2), 174-186. [CrossRef]

- Oh, V. K. S., Sarwar, A., & Pervez, N. (2022). The study of mindfulness as an intervening factor for enhanced psychological well-being in building the level of resilience. Frontiers in psychology, 13, 1056834. [CrossRef]

- Olano, H. A., Kachan, D., Tannenbaum, S. L., Mehta, A., Annane, D., & Lee, D. J. (2015). Engagement in mindfulness practices by U.S. adults: sociodemographic barriers. J Altern Complement Med, 21(2), 100-102. [CrossRef]

- Onesimo Sandoval, J. S. (2014). The unspoken truth: Evaluating attitudes toward immigration in Missouri. International Journal of Social Science Research, 2(2), 55-71.

- Ornelas, I. J., Nelson, A. K., Price, C., Pérez-Solorio, S. A., Rao, D., & Chan, K. C. G. (2025). Amigas Latinas Motivando el Alma (ALMA): Increasing Mindfulness and Social Support to Reduce Depression and Anxiety in Latina Immigrant Women. Mindfulness, 16(7), 1923–1932. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, J. A. (2015). Bridging the gap: Adapting mindfulness-based stress reduction for Latino populations. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1723912536/.

- Ortiz, J. A., Smith, B. W., Shelley, B. M., & Erickson, K. S. (2019). Adapting Mindfulness to Engage Latinos and Improve Mental Health in Primary Care: a Pilot Study. Mindfulness (N Y), 10(12), 2522-2531. [CrossRef]

- Parker, G. (2020). Restorative Yoga for Ethnic and Race-Based Stress and Trauma. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Raines, E. M., Rogers, A. H., Bakhshaie, J., Viana, A. G., Lemaire, C., Garza, M., Mayorga, N. A., Ochoa-Perez, M., & Zvolensky, M. J. (2018). Mindful attention moderating the effect of experiential avoidance in terms of mental health among Latinos in a federally qualified health center. Psychiatry Research, 270, 574-580. [CrossRef]

- Redline, S., Sotres-Alvarez, D., Loredo, J., Hall, M., Patel, S. R., Ramos, A., Shah, N., Ries, A., Arens, R., Barnhart, J., Youngblood, M., Zee, P., & Daviglus, M. L. (2014). Sleep-disordered Breathing in Hispanic/Latino Individuals of Diverse Backgrounds The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 189(3), 335-344. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Diaz, C. E., Guilamo-Ramos, V., Mena, L., Hall, E., Honermann, B., Crowley, J. S., Baral, S., Prado, G. J., Marzan-Rodriguez, M., Beyrer, C., Sullivan, P. S., & Millett, G. A. (2020). Risk for COVID-19 infection and death among Latinos in the United States: examining heterogeneity in transmission dynamics. Annals of epidemiology, 52, 46–53.e2. [CrossRef]

- Rosner, B., Glynn, R. J., & Lee, M. L. (2006). The Wilcoxon signed rank test for paired comparisons of clustered data. Biometrics, 62(1), 185–192. [CrossRef]

- Roth, B., & Creaser, T. (1997). Mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction: experience with a bilingual inner-city program. Nurse Pract, 22(3), 150-152, 154, 157 passim. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9078521.

- Roth, B., & Stanley, T. W. (2002). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and healthcare utilization in the inner city: preliminary findings. Altern Ther Health Med, 8(1), 60-62, 64-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11795623.

- Rusch, H. L., Rosario, M., Levison, L. M., Olivera, A., Livingston, W. S., Wu, T., & Gill, J. M. (2019). The effect of mindfulness meditation on sleep quality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1445(1), 5–16. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, D., Maurer, S., Lengua, L., Duran, B., & Ornelas, I. J. (2018). Amigas Latinas Motivando el Alma (ALMA): an Evaluation of a Mindfulness Intervention to Promote Mental Health among Latina Immigrant Mothers. J Behav Health Serv Res, 45(2), 280-291. [CrossRef]

- Salas-Wright, C. P., Clark, T. T., Vaughn, M. G., & Córdova, D. (2015). Profiles of acculturation among Hispanics in the United States: links with discrimination and substance use [journal article]. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(1), 39-49. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M., Asti, L., Nacion, K. M., & Chisolm, D. J. (2016). The Role of Health Literacy in Predicting Multiple Healthcare Outcomes Among Hispanics in a Nationally Representative Sample: A Comparative Analysis by English Proficiency Levels [journal article]. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 18(3), 608-615. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S., Gmeiner, S., Schultz, C., Lower, M., Kuhn, K., Naranjo, J. R., Brenneisen, C., & Hinterberger, T. (2015). Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction (MBSR) as Treatment for Chronic Back Pain - an Observational Study with Assessment of Thalamocortical Dysrhythmia. Forsch Komplementmed, 22(5), 298-303. [CrossRef]

- Serpa, J. G., Taylor, S. L., & Tillisch, K. (2014). Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) reduces anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation in veterans. Med Care, 52(12 Suppl 5), S19-24. [CrossRef]

- Sevilla-Llewellyn-Jones, J., Santesteban-Echarri, O., Pryor, I., McGorry, P., & Alvarez-Jimenez, M. (2018). Web-Based Mindfulness Interventions for Mental Health Treatment: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JMIR Ment Health, 5(3), e10278. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J., & Mapel, T. (2011). An investigation into the health benefits of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) for people living with a range of chronic physical illnesses in New Zealand. N Z Med J, 124(1338), 68-75. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21946964.

- Soler, J., Tejedor, R., Feliu-Soler, A., Pascual, J. C., Cebolla, A., Soriano, J., Alvarez, E., & Perez, V. (2012). Psychometric proprieties of Spanish version of Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS). Actas espanolas de psiquiatria, 40(1), 19–26.

- Spears, C. A., Houchins, S. C., Stewart, D. W., Chen, M., Correa-Fernandez, V., Cano, M. A., Heppner, W. L., Vidrine, J. I., & Wetter, D. W. (2015). Nonjudging facet of mindfulness predicts enhanced smoking cessation in Hispanics. Psychol Addict Behav, 29(4), 918-923. [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, K., Tasali, E., Leproult, R., & Van Cauter, E. (2009). Effects of poor and short sleep on glucose metabolism and obesity risk. Nature reviews. Endocrinology, 5(5), 253–261. [CrossRef]

- Sung, J. H., Lee, J. E., & Lee, J. Y. (2018). Effects of Social Support on Reducing Acculturative Stress-Related to Discrimination between Latin and Asian Immigrants: Results from National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS). Journal of advances in medicine and medical research, 27(4), JAMMR.42728. [CrossRef]

- Tejedor, R., Feliu-Soler, A., Pascual, J. C., Cebolla, A., Portella, M. J., Trujols, J., Soriano, J., Pérez, V., & Soler, J. (2014). Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale. Revista de psiquiatria y salud mental, 7(4), 157–165. [CrossRef]

- Tobin, J., Hardy, J., Calanche, M. L., Gonzalez, K. D., Baezconde-Garbanati, L., Contreras, R., & Bluthenthal, R. N. (2021). A Community-Based Mindfulness Intervention Among Latino Adolescents and Their Parents: A Qualitative Feasibility and Acceptability Study. Journal of immigrant and minority health, 23(2), 344–352. [CrossRef]

- Toivonen, K. I., Zernicke, K., & Carlson, L. E. (2017). Web-Based Mindfulness Interventions for People With Physical Health Conditions: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res, 19(8), e303. [CrossRef]

- Torres, L. (2010). Predicting levels of Latino depression: acculturation, acculturative stress, and coping. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16(2), 256–263. [CrossRef]

- Tran, A. N., Ornelas, I. J., Perez, G., Green, M. A., Lyn, M., & Corbie-Smith, G. (2014). Evaluation of Amigas Latinas Motivando el Alma (ALMA): a pilot promotora intervention focused on stress and coping among immigrant Latinas. J Immigr Minor Health, 16(2), 280-289. [CrossRef]

- Treleaven, D. A. (2018). Trauma-sensitive mindfulness: Practices for safe and transformative healing. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Urzúa, A., Caqueo-Urízar, A., Henríquez, D., & Williams, D. R. (2021). Discrimination and Health: The Mediating Effect of Acculturative Stress. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(10), 5312. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2019). 1968-2019 Annual Social Economic Supplements. https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2019/demo/p60-266.html.

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). Hispanic Heritage Month: 2023. Facts for Features. U.S. Department of Commerce. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2023/hispanic-heritage-month.html.

- Vargas, E. D., Sanchez, G. R., & Juárez, M. (2017). Fear by Association: Perceptions of Anti-Immigrant Policy and Health Outcomes. Journal of health politics, policy and law, 42(3), 459–483. [CrossRef]

- Veqar, Z., & Hussain, M. E. (2018). Psychometric analysis of Epworth Sleepiness Scale and its correlation with Pittsburgh sleep quality index in poor sleepers among Indian university students. International journal of adolescent medicine and health, 31(2), /j/ijamh.2019.31.issue-2/ijamh-2016-0151/ijamh-2016-0151.xml. [CrossRef]

- Viana, A. G., Paulus, D. J., Garza, M., Lemaire, C., Bakhshaie, J., Cardoso, J. B., Ochoa-Perez, M., Valdivieso, J., & Zvolensky, M. J. (2017). Rumination and PTSD symptoms among trauma-exposed Latinos in primary care: Is mindful attention helpful? Psychiatry Res, 258, 244-249. [CrossRef]

- Vos, S. R., Shrader, C. H., Alvarez, V. C., Meca, A., Unger, J. B., Brown, E. C., Zeledon, I., Soto, D., & Schwartz, S. J. (2021). Cultural Stress in the Age of Mass Xenophobia: Perspectives from Latin/o Adolescents. International journal of intercultural relations : IJIR, 80, 217–230. [CrossRef]

- Waheed, W., Hughes-Morley, A., Woodham, A., Allen, G., & Bower, P. (2015). Overcoming barriers to recruiting ethnic minorities to mental health research: a typology of recruitment strategies. BMC Psychiatry, 15(1), 101. [CrossRef]

- Wassertheil-Smoller, S., Arredondo, E. M., Cai, J. W., Castaneda, S. F., Choca, J. P.;, Gallo, L. C., Jung, M., LaVange, L. M., Lee-Rey, E. T., Mosley, T., Penedo, F. J., Santistaban, D. A., & Zee, P. C. (2014). Depression, anxiety, antidepressant use, and cardiovascular disease among Hispanic men and women of different national backgrounds: results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Annals of Epidemiology, 24(11), 822-830. [CrossRef]

- Whinnery, J., Jackson, N., Rattanaumpawan, P., & Grandner, M. A. (2014). Short and long sleep duration associated with race/ethnicity, sociodemographics, and socioeconomic position. Sleep, 37(3), 601–611. [CrossRef]

- Woods-Giscombe, C. L., & Black, A. R. (2010). Mind-Body Interventions to Reduce Risk for Health Disparities Related to Stress and Strength Among African American Women: The Potential of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, Loving-Kindness, and the NTU Therapeutic Framework. Complement Health Pract Rev, 15(3), 115-131. [CrossRef]

- Yin, J., Jin, X., Shan, Z., Li, S., Huang, H., Li, P., Peng, X., Peng, Z., Yu, K., Bao, W., Yang, W., Chen, X., & Liu, L. (2017). Relationship of Sleep Duration With All-Cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Events: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Journal of the American Heart Association, 6(9), e005947. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, C., Nagy, G. A., Wu, J., Stafford, A. M., McCabe, B., & Gonzalez-Guarda, R. M. (2022). Acculturation stress, age at immigration, and employment status as predictors of sleep among Latinx immigrants. . Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health., 24, 1408-1420. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., Zhao, H., & Zheng, Y. (2018). Effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on symptom variables and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M. X., Masters-Waage, T. C., Yao, J., Lu, Y., Tan, N., & Narayanan, J. (2020). Stay Mindful and Carry on: Mindfulness Neutralizes COVID-19 Stressors on Work Engagement via Sleep Duration. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 610156. [CrossRef]

- Zvolensky, M. J., Bakhshaie, J., Garza, M., Paulus, D. J., Valdivieso, J., Lam, H., Bogiaizian, D., Robles, Z., Schmidt, N. B., & Vujanovic, A. (2015). Anxiety sensitivity and mindful attention in terms of anxiety and depressive symptoms and disorders among Latinos in primary care. Psychiatry Research, 229(1-2), 245-251. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).