2. Case Presentation

A 3-year-old neutered male West Highland White Terrier (6.5 kg) with no history of medical problems was brought to the clinic with signs of dyspnoea after being fed an apple (day 0). Barium contrast radiography revealed a foreign body (apple) obstructing the lower oesophagus, which was surgically pushed down to the stomach under anaesthesia. However, the patient regurgitated and developed respiratory failure and cyanosis, suggesting aspiration. Immediate intubation (bagging rate, 60/min; fraction of inspired oxygen [FiO

2], 1.0) and suctioning were performed, and the respiratory parameters were as follows: oxygen saturation (SpO

2), 77%; end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO

2), 67 mmHg; pH, 7.003; partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO

2), 120 mmHg; partial pressure of oxygen (pO

2), 61 mmHg; PaO

2/FiO

2 (P/F), 61 mmHg (

Table 1).

One hour after intubation (ventilator support setting: respiration rate (RR), 40/min; positive end-expiratory pressure [PEEP], 10 cmH2O; peak inspiratory pressure [PIP], 35 cmH2O; FiO2, 1.0), there was no improvement in respiration (SpO2, 70%; ETCO2, 60 mmHg; pH, 7.121; pCO2, 91 mmHg; pO2, 44 mmHg; P/F, 44 mmHg); thus, euthanasia or ECMO was proposed. The owner refused, and respiratory support with a ventilator was continued under various ventilator support settings, including high PEEP (>20 cmH2O) or high frequency, but none of various settings improved and ventilator settings were adjusted time by time with SpO2 and ETCO2 level. After 2.5 h of ventilator support (ventilator setting: RR, 50/min; PEEP, 6-15 cmH2O; PIP, 35-45 cmH2O; FiO2, 1.0), with little improvement in respiratory parameters (SpO2, 80%; ETCO2, 84 mmHg; pH, 7.073; pCO2, 118.5 mmHg; pO2, 46 mmHg; P/F, 44), it was determined that the patient’s condition could not be improved by ventilatory management without removing the obstruction. After consultation with the owner, the dog was planned for tracheobronchial lavage, provided with respiratory support using ECMO.

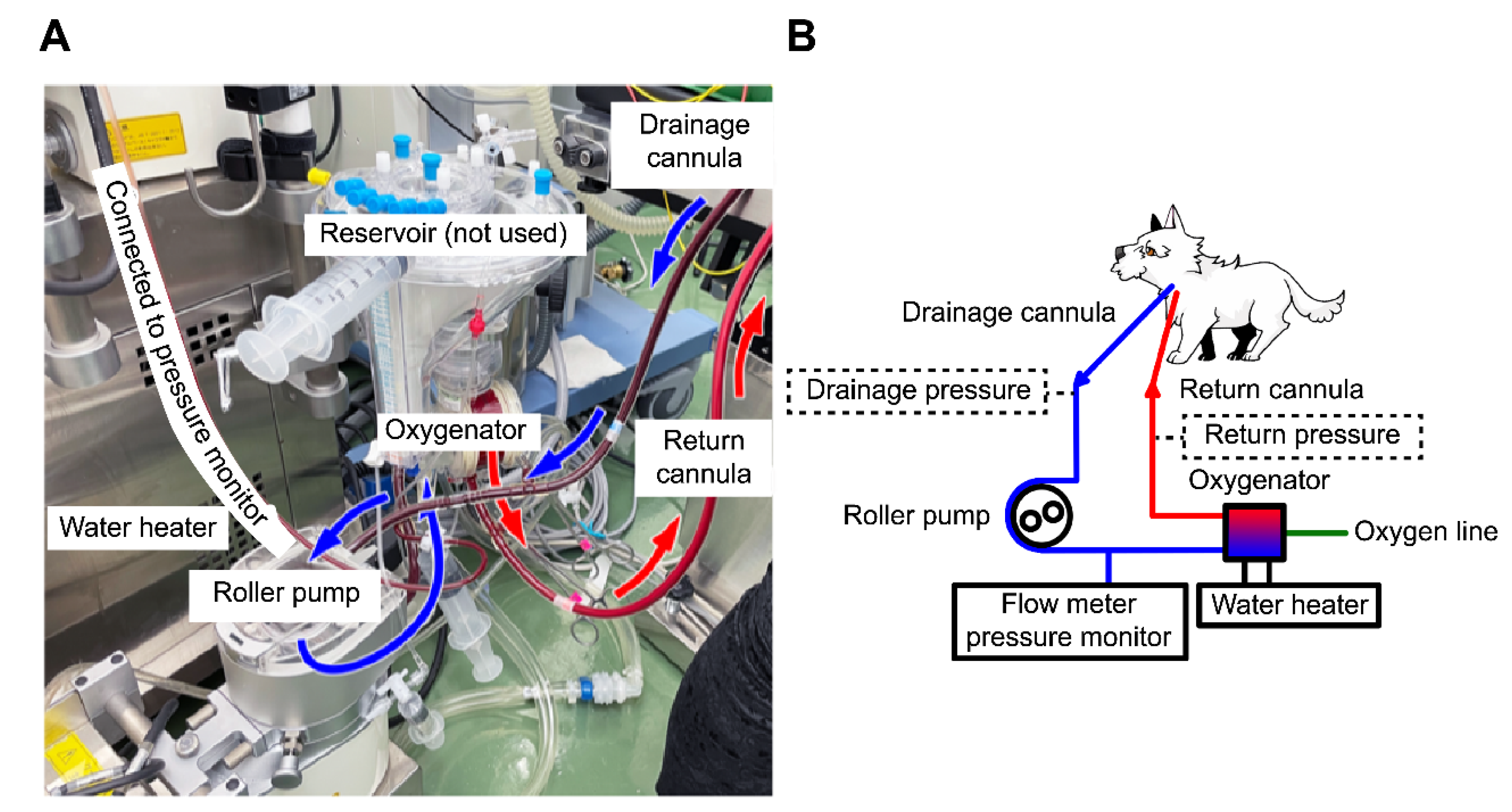

Heparin (300 U/kg) was administered intravenously, and the measured activated clotting time (ACT) (i-STAT ACT Kaolin; Abbot Japan, Tokyo, Japan) was >250 s. A 10-Fr drainage cannula (Flexmate; Toyobo, Shiga, Japan) was inserted into the left external jugular vein, and a 6-Fr return cannula (DLP Cardiopulmonary Bypass Cannula; Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was inserted into the common carotid artery. The dog was connected to an oxygenator and circuit (MERA-HP-Exelung TPC; Senko Medical Instrument, Tokyo, Japan) with a priming volume of 150 mL to establish VA-ECMO (

Figure 1).

The MERA-Extracorporeal Circulation System TRUSYS (Senko Medical Instrument) completed the system. The circulatory support flow rate was approximately 40% (250–280 mL/min), maintaining a blood delivery pressure of approximately 120 mmHg with 0.5 L/min of FiO

2 1.0. After the ECMO pump was turned on, the respiratory parameters improved (SpO

2, 90%; ETCO

2, 45 mmHg; pH, 7.236; PaCO

2, 70 mmHg; and PaO

2, 43 mmHg). The cannulas were sutured to a drape, which was sutured to the skin to prevent accidental removal. After confirming that the cannulas were secured, tracheobronchial lavage was initiated. Saline (50 mL/kg) was delivered through the tracheal tube to complete airway occlusion with saline (Video S1). After agitation by shaking the body, the saline was drained. Barium and a lump of phlegm were removed during the first lavage, and SpO

2 and levels of 100% and 40 mmHg were obtained, respectively. White fluid was removed after the second lavage. The patient underwent three lavages in the right and left lateral recumbent positions. Once the drained fluid was clear in colour, the SpO

2 was 100% and the ETCO

2 was 20 mmHg, and the ventilator support setting was lowered (RR, 20/min; PEEP, 6 cmH

2O; PIP, 26 cmH

2O; FiO

2, 1.0). Suction was used to remove residual saline from the airway, and the dog was maintained in a head-down position. Ventilation was continued with the tracheal tube cuff deflated to dry out the airway. Blood gas analysis after tracheobronchial lavage showed the following values: pH, 7.488; PaCO

2, 23 mmHg; PaO

2, 112 mmHg (ventilator settings: RR, 10/min; PEEP, 6 cmH

2O; PIP, 26 cmH

2O; FiO

2, 0.6; P/F, 186). We continued ECMO support and waited for the recovery of respiratory function. The head-down position was discontinued after confirming that no more fluid could be removed through the tracheal tube or by suction. ACT was checked every 30 min to maintain it at >250 s, and 150 IU of heparin was administered once at 90 min after initiation of ECMO. The haematocrit level was 43% and the platelet count was 15.2×10

4/μL during ECMO, and no transfusion was required during ECMO. The patient’s respiratory status remained good, and weaning from ECMO was attempted. The ECMO flow rate was reduced to 8% (10 mL/sec), with 0.5 L/min of FiO

2 0.3, and weaning was attempted under the following ventilator settings: RR, 30/min; PEEP, 6 cmH

2O; PIP, 26 cmH

2O; FiO

2, 0.7; however, the oxygenation worsened, with SpO

2 of 88%, PaO

2 of 75 mmHg, and P/F of 107. Intravenous furosemide (1 mg/kg) was administered to treat the acute respiratory distress syndrome due to lung injury caused by intubation, aggressive ventilation, and increased vascular permeability due to the ECMO. Subsequently, oxygenation improved (SpO

2, 98%; pH, 7.344; PaCO

2, 43 mmHg; PaO

2, 215 mmHg) under the following ventilator settings: RR, 25/min; PEEP, 6 cmH

2O; PIP, 26 cmH

2O; FiO

2, 0.7; P/F, 305; the patient was weaned from ECMO. The total ECMO support time was 180 min. The heart rate gradually increased after weaning (

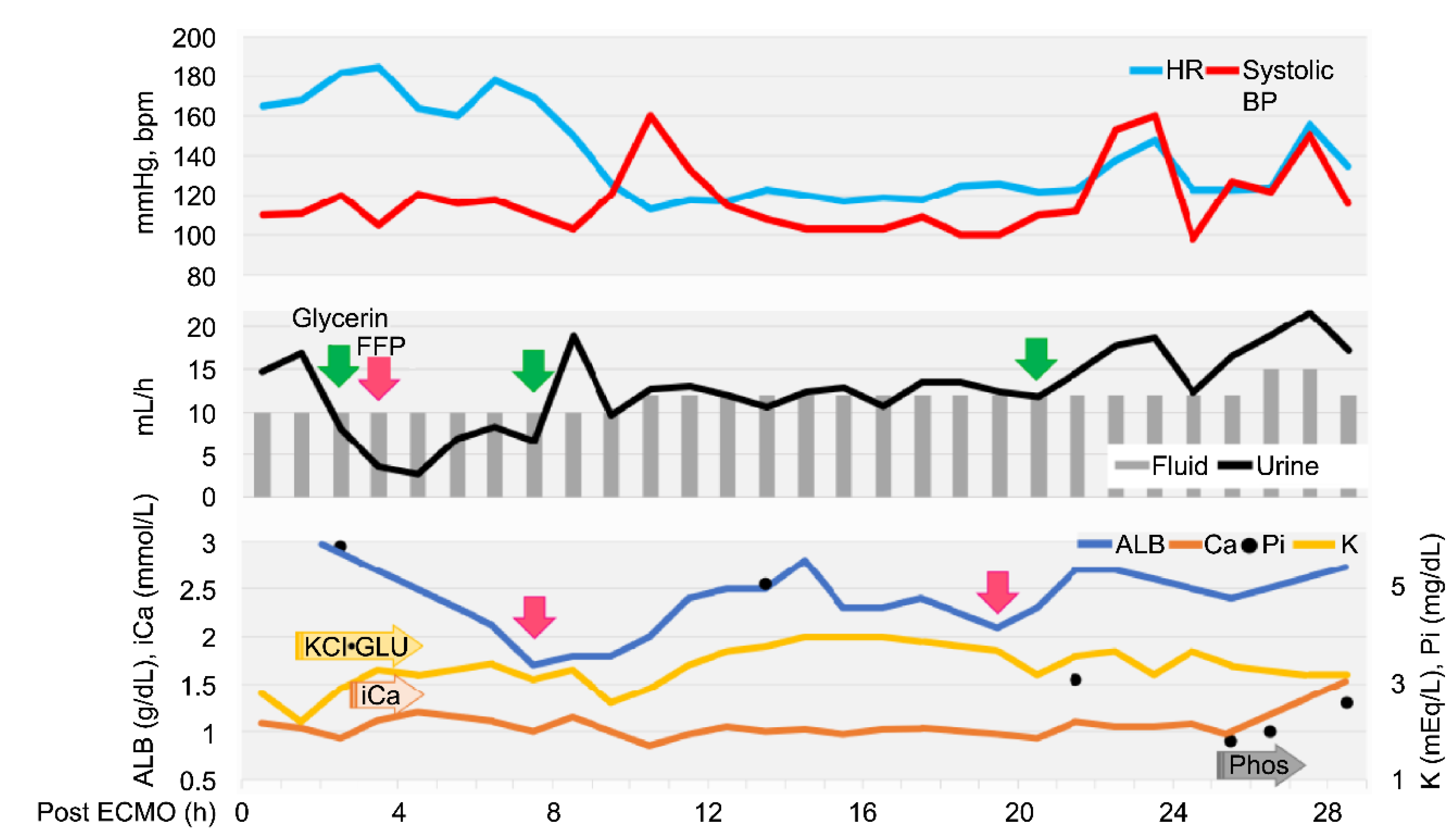

Figure 2), but the fluid volume after ECMO withdrawal was balanced (the delivered fluid volume was approximately equal to the urine volume).

Echocardiography revealed low cardiac volume and tachycardia due to increased vascular permeability. Intravascular hypovolemia was suspected. Glycerine (10 mL/kg) and fresh frozen plasma (FFP) (15 mL/kg) were administered to prevent cerebral oedema. Glucose (1–2 g/kg/h), KCl (0.1–0.3 mEq/kg/h), and calcium gluconate hydrate (10–20 mg/kg/h) were administered as CRI, and the dose was controlled with blood examination each time. Dobutamine (0.5–3 µg/kg/min) and noradrenaline (0.02–0.1 µg/kg/min) were administered to control blood pressure. Seven hours after ECMO discontinuation, tachycardia improved, but the albumin level decreased (1.7 g/dL). Therefore, FFP was re-administered, which increased the albumin level to 2.8 g/dL. Glycerine was also administered to prevent cerebral oedema caused by continued low urine output. The patient stabilized, but 20 h after ECMO discontinuation, mild hypotension and decreased albumin (2.1 g/dL) were observed; hence, FFP was administered again. Glycerine was administered every 12 h. The urine output increased to 15–30 mL/kg/h 24 h after ECMO discontinuation. Stick urinalysis, performed because of polyuria, revealed an occult blood reaction (2+) and negative results for glucose, ketones, and bilirubin. Sodium phosphate correction was performed to treat the electrolyte abnormalities caused by polyuria. The patient was managed under anaesthesia with sevoflurane 1.5–2.0 minimum alveolar concentration and rocuronium bromide 0.4 mg/kg/h to prevent brain damage due to prolonged hypoxia and high carbon dioxide levels. Since the respiratory status was good (SpO

2, 100%; ETCO

2, 54 mmHg; pH, 7.305; pCO

2, 51.0 mmHg; pO

2, 187 mmHg; P/F, 311) under a ventilator setting of RR of 32/min, PEEP of 6 cmH

2O, PIP of 20 cmH

2O, and FiO

2 of 0.6, the patient was weaned off rocuronium bromide (constant rate infusion) and switched to spontaneous breathing with pressure support mode (RR, 20/min; PEEP, 6 cmH

2O; pressure support, 15 cmH

2O; FiO

2, 0.4). At 26 h after ECMO discontinuation, the results of blood gas analysis, blood biochemistry tests, and complete blood count were good (SpO

2, 100%; ETCO

2, 37 mmHg; pH, 7.338; pCO

2, 47 mmHg; pO

2, 126 mmHg; P/F, 315; haematocrit, 39%; platelet, 11.5×10

4/μL). The eyelid reflex and swallowing response were promptly observed, and the patient was extubated 28 h after ECMO discontinuation. After recovery from anaesthesia, the level of modified Glasgow Coma Scale (MGCS) was 16, and the dog was able to turn around and change its position independently when called by its name. The patient was also able to drink water and consume liquid foods. However, 6 h after extubation, head tremors were observed (Video S2). Temporary improvement was observed after intravenous administration of diazepam (0.5 mg/kg). However, as the tremors continued, continuous diazepam was administered, and hyperthermia, panting, and involuntary movements appeared, and the MGCS dropped to 10. Sedation was reinforced, but repeated panting and respiratory arrest occurred; therefore, the patient was intubated again 18 h after extubation, and respiratory control was performed. Because of the pronounced neurological symptoms, we considered the high body temperature and panting to be due to brain damage and the repeated administration of glycerine and anticonvulsants. The patient was extubated after the respiratory arrest resolved, but sedation was continued. However, the high body temperature and involuntary movements persisted. On day 6, the patient’s hyperthermia and involuntary movements improved, and all medications used for sedation management were discontinued. However, the patient’s consciousness did not improve, although mild eyelid reflex and swallowing response were observed. Cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and electroencephalography (EEG) were performed to assess the brain damage. The white matter showed hyposignal on T1-weighted and post-contrast T1-weighted MRI (

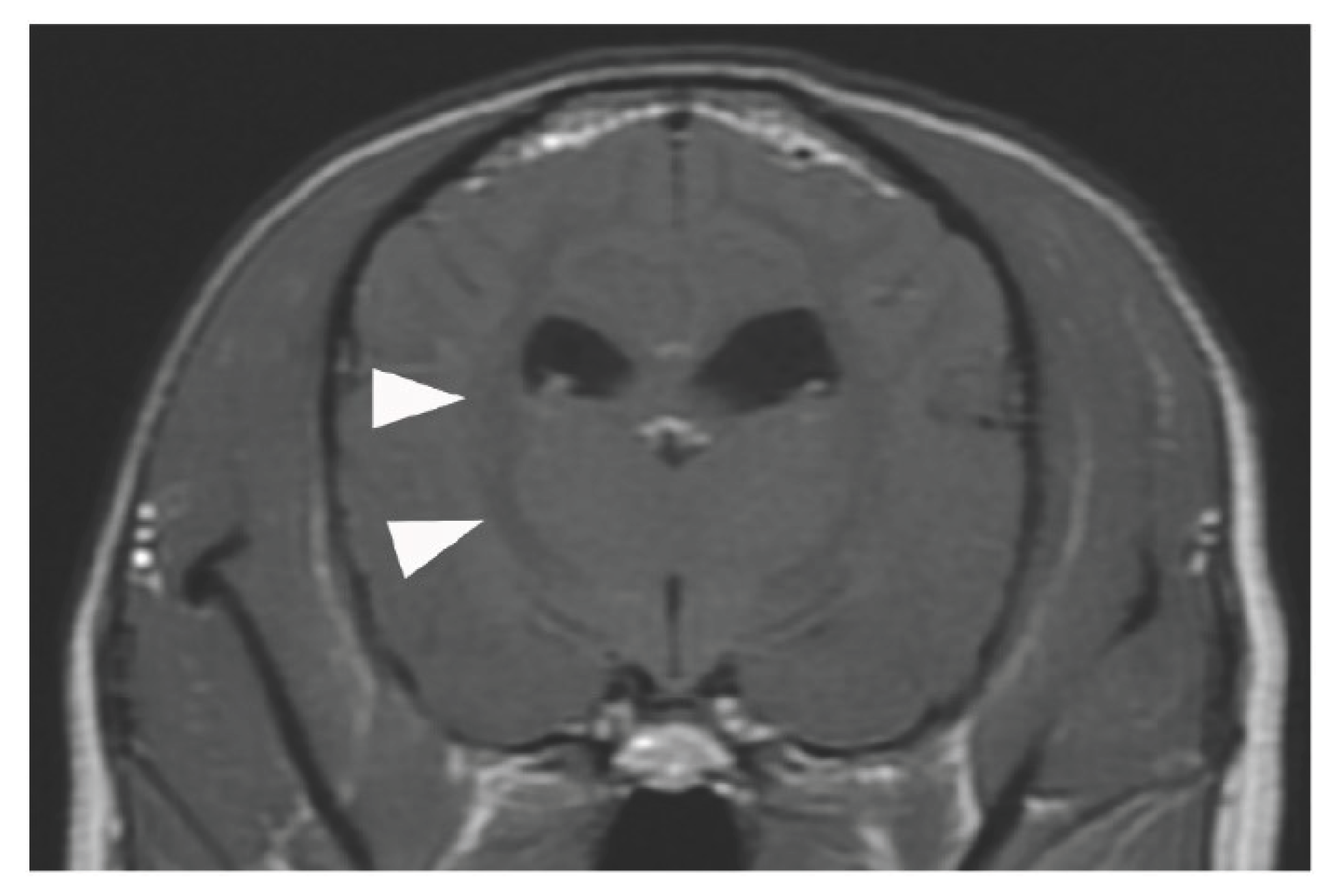

Figure 3).

No haemorrhage, infarction, cerebral oedema, or cerebral herniation was observed. EEG examination showed no apparent abnormal waveforms. The eyelid reflex and swallowing response progressively weakened, the MGCS was reduced to 3, and the patient died on day 8 from respiratory arrest without regaining consciousness. The owner did not request further resuscitation.

3. Discussion

According to the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization guidelines, ECMO is indicated for bronchoalveolar lavage in cases of severe inhalation injury. In this case, the patient developed upper airway obstruction secondary to barium aspiration, constituting a severe inhalation injury that met the criteria for extensive bronchoalveolar lavage, as defined by [

9], the International Organization for Human ECMO. Given that the patient was young (3 years), exhibited good energy and appetite, and had no underlying chronic diseases, a full recovery could allow it to lead a normal life. Therefore, ECMO was not contraindicated and was indicated for prompt introduction. However, due to the owner’s reluctance and our inexperience in using the modality, a long duration elapsed between the presentation with respiratory failure and the introduction of ECMO, resulting in prolonged hypoxia. Oxygenation was maintained by ECMO, which enabled tracheobronchial lavage with complete airway occlusion. Following the lavage procedure performed under ECMO support, barium was completely removed and the respiratory status improved drastically, the dog was allowed to drink water after extubation. MRI demonstrated no brain herniation or ECMO-related complications commonly reported in human medicine, such as cerebral hemorrhage or stroke [

4,

10]. Therefore, the patient might have survived with no hypoxia-related brain damage [

11] if early intervention had been performed. Currently, no indication criteria exist for the use of ECMO in veterinary medicine. However, human studies have reported that early initiation of ECMO improves survival in cases of acute respiratory distress syndrome [

12], pulmonary hypertension [

13], coronavirus disease 2019 [

14], and cardiogenic shock [

15,

16,

17]. Based on these findings, we strongly believe that the same principle applies in the veterinary field. If ECMO is associated with a high probability of survival, it should be applied proactively and without delay.

In this case, the ECMO pump flow rate was only approximately 50% of the adult dose recommended by the guidelines and approximately 40% of the paediatric dose [

18,

19,

20]. The cardiopulmonary bypass circuit lacked a pressure monitor for ECMO because we modified the circuit used for canine open-heart surgery, which we perform periodically. Therefore, the pressure monitor was only placed before the oxygenator, and the ECMO was operated with the oxygenator pressure as an indicator. Because ECMO use is long and prone to thrombosis and circuit problems, the drainage and return pressures should be monitored to accurately adjust the flow rate (

Figure 1B) [

18]. In this case, we could not measure the drainage pressure; thus, we could not increase the pump flow rate. Furthermore, the SpO

2 increased from 63% to 90% immediately after ECMO was introduced, but the SaO

2 did not improve. This might be due to the use of VA-ECMO and the common carotid artery for the return cannula. Although VV-ECMO mixes oxygenated blood in the veins, VA-ECMO mixes oxygenated blood in the arteries. In this case, the mixing point may have been near the brachiocephalic artery because the blood was pumped at a slow flow rate into the left common carotid artery [

9]. Therefore, the blood to the head was oxygenated, as indicated by the increased SpO

2 measured on the tongue. However, since the pump flow rate was approximately 40% and the blood was collected from the hind leg, an increase in SaO

2 could not be confirmed. Due to the small body size, a 10 Fr drainage cannula was placed in the jugular vein, and VV-ECMO would have required an abdominal aortic approach. The main objective of ECMO was lung lavage, which involved moving the dog. To mitigate the risk of catheter dislodgement, VA-ECMO was selected because it could be conducted entirely via a cervical incision and enabled rapid cannulation. Future studies involving dogs are planned to compare the flow and gas exchange rates between VA-ECMO and VV-ECMO.

In human medicine, ECMO use is associated with ECMO- and patient-related complications [

1,

21]. Our case showed no ECMO-related complications, presumably because the total ECMO use was only 3 h, which presented few opportunities for thrombosis, bleeding, or problems with the oxygenator to occur. Problems could potentially be caused by the cannula or circuit during airway lavage; however, we believe that fixing the cannulas effectively prevented extraction accidents. We likewise did not observe patient-related complications, such as bleeding, haemolysis, or infection, possibly due to the short duration of care. However, a urine test revealed an occult blood reaction of 2+. In human medicine, anaemia is expected to progress owing to the consumption of blood by the pump, even in the absence of apparent haemolysis [

22]. Therefore, red blood cell transfusion might be necessary in prolonged cases. Furthermore, patient-related complications also include decreased circulating blood volume and changes in circulatory dynamics. This is due to the increased body water volume because of the ECMO circuit and the increased vascular permeability caused by foreign-body reactions, leading to oedema, including pulmonary edema, and cerebral herniation [

10,

23]. In this case, low albumin levels due to intravascular hypovolemia and increased vascular permeability occurred within 24 h after weaning from ECMO, with very unstable circulatory dynamics within 8 h after weaning. The total FFP volume used in this case was 110 mL. In human medicine, blood transfusion is always required when ECMO is used in patients weighing <10–15 kg [

12]. However, in our case, the blood transfusion volume per body weight was higher than that commonly used in humans [

22]. This might be due to the considerably higher foreign-body exposure per body surface area in this dog than in humans and the possible species-related differences. Although the patient weighed 6.5 kg and the haemodilution rate was low, smaller patients might require a red blood cell transfusion. In this case, complications similar to those observed in human medicine were observed after brief ECMO. However, their degree and timing could vary depending on the support time and size of the dog. Further studies are required to determine the appropriate management of dogs when ECMO is introduced and after weaning. The applicable cases will differ greatly depending on how ECMO is established in animals, how ECMO-related complications are managed, and how patients are managed before and after the introduction of ECMO. ECMO is expected to become an effective treatment option in veterinary medicine once management methods improve and applicable cases are identified. However, ECMO is only a time-saving device to protect organs from hypoxia and allow time for the treatment of the underlying disease.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.I.; formal analysis, N.I.; investigation, N.I., Y.U., K.S., E.M., T.T., T.M., S.S. and Y.H.; data curation, N.I.; writing—original draft preparation, N.I., Y.U., K.S., E.M., T.T., T.M., S.S. and Y.H; writing—review and editing, N.I., Y.U., K.S., E.M., T.T., T.M., S.S. and Y.H; visualization, N.I., Y.U., K.S., E.M., T.T., T.M., S.S. and Y.H; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.