Submitted:

08 October 2025

Posted:

09 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

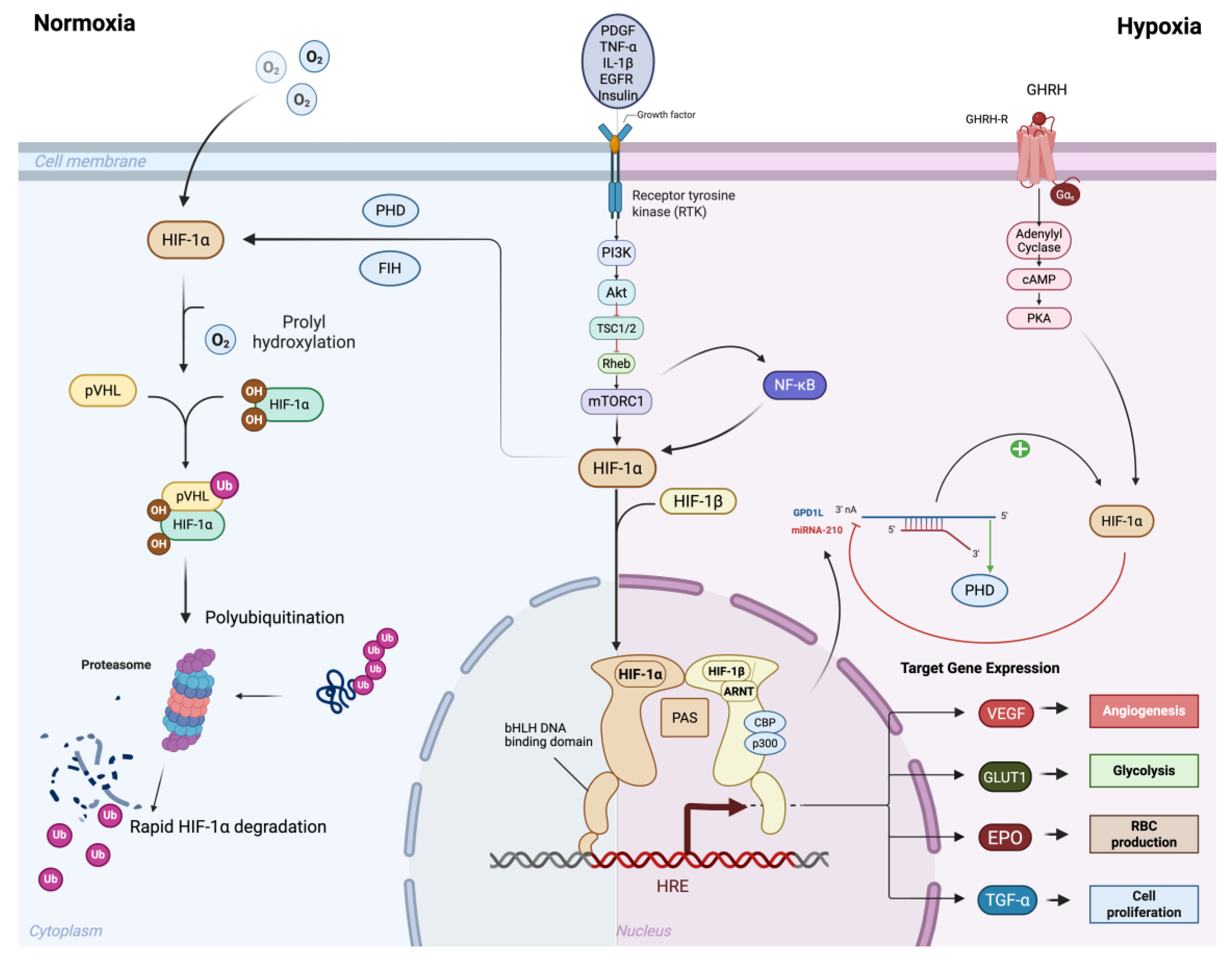

2. Oxygen-Dependent Regulation of the HIFs

3. Oxygen-Independent Regulation of the HIFs

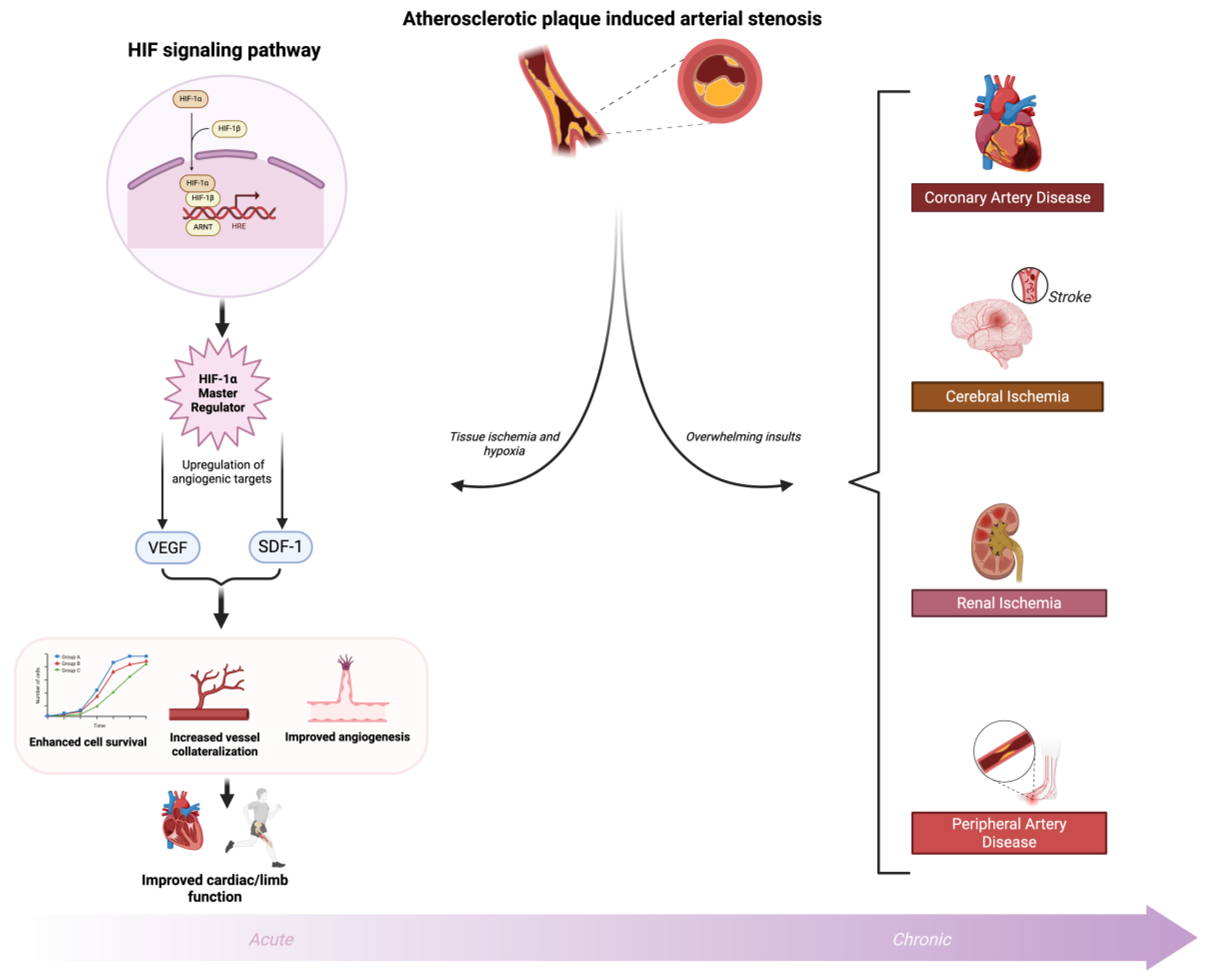

4. The HIF Proteins and Neovascularization

5. HIFs and Ischemic Cardiovascular Disease

6. HIF-1α Modulation for Therapeutic Angiogenesis and Ischemic Cardiovascular Diseases

7. Prolyl Hydroxylase Domain Inhibition

8. HIF-1α Gene Overexpression

9. Cell-Based HIF-1α Therapies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HIFs | hypoxia inducible factors |

| EPO | erythropoietin |

| RBC | red blood cell |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| TCA | tricarboxylic acid cycle |

| ARNT | aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator |

| ODD | oxygen-dependent degradation |

| PHD | prolyl hydroxylase domain |

| VHL | Von Hippel Lindau |

| DFO | deferoxamine |

| CoCl2 | cobalt chloride |

| HREs | hypoxic response elements |

| N-TAD | N-terminal activation domains |

| C-TAD | C-terminal activation domains |

| FIH | Factor Inhibiting HIF |

| HAF | hypoxia-associated factor |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| PASMCs | pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells |

| EGFR | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor |

| PDGF | Platelet-Derived Growth Factor |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| GHRH | growth hormone-releasing hormone |

| miRNAs | microRNAs |

| GPD1L | glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1-like |

| eNOS | endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| SMC | smooth muscle cell |

| MCP-1 | monocyte chemotactic protein-1 |

| CAMs | cell adhesion molecules |

| PAD | Peripheral Artery Disease |

| CLTI | chronic limb-threatening ischemia |

| Dll4 | delta like ligand 4 |

| MMPs | matrix metalloproteases |

| uPA | urokinase plasminogen activator |

| PAI-1 | plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 |

| ECM | extracellular matrix |

| EPCs | endothelial progenitor cells |

| HGF | hepatocyte growth factor |

| SDF-1α | Stromal Cell-Derived Factor-1 alpha |

| CAD | coronary artery disease |

| SNPs | Single nucleotide polymorphisms |

| MI | Myocardial Infarction |

| PCI | percutaneous coronary intervention |

| CABG | coronary artery bypass grafting |

| tPA | tissue plasminogen activator |

| shRNA | short hairpin RNA |

| MC-shPHD2 | minicircle vector |

| FGF | Fibroblast Growth Factor |

| KDR | Kinase Insert Domain Receptor |

| DMOG | Dimethyloxalylglycine |

| ABI | Ankle-Brachial Index |

| AdCA5 | adenoviral HIF-1α |

| CACs | circulating angiogenic cells |

| AAV | Adeno-Associated Virus |

| MSCs | Mesenchymal Stem Cells |

| ADSCs | Adipose-Derived Stem Cells |

| EPCs | Endothelial Progenitor Cells |

| iPSCs | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells |

| EVs | Extracellular vesicles |

| CSCs | Cardiac stem cells |

| HIF-CSC-Gel | HIF-1α-transfected CSCs embedded in fibrin gel |

| AMI | acute myocardial infarction |

References

- Semenza, G.L. , Regulation of Mammalian O2 Homeostasis by Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol, 1999. 15: p. 551-578.

- Wenger, R.H. , Cellular adaptation to hypoxia: O2-sensing protein hydroxylases, hypoxia-inducible transcription factors, and O2-regulated gene expression. FASEB J, 2002. 16(10): p. 1151-1162. [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L. , Hypoxia-inducible factors in physiology and medicine. Cell, 2012. 148(3): p. 399-408.

- Wang, G.L. , et al., Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix–loop–helix–PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1995. 92(12): p. 5510-5514.

- Semenza, G.L. , Wang G.L., A Nuclear Factor Induced by Hypoxia via De Novo Protein Synthesis Binds to the Human Erythropoietin Gene Enhancer at a Site Required for Transcriptional Activation. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 1992. 12: p. 5447-5454.

- Gregg, L. Semenza, M.K.N., Suzie M. Chi, Stylianos E. Antonarakis, Hypoxia-inducible nuclear factors bind to an enhancer element located 3' to the human erythropoietin gene. PNAS, 1991. 88: p. 5680-5684.

- Haase, V.H. , Regulation of erythropoiesis by hypoxia-inducible factors. Blood Rev, 2013. 27(1): p. 41-53. [CrossRef]

- Wei Liu, S.-M.S. , Xu-Yun Zhao, Guo-Qiang Chen, Targeted genes and interacting proteins of hypoxia inducible factor-1 Int J Biochem Mol Biol, 2012. 3: p. 165-178.

- Forsythe, J.A. , et al., Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Mol Cell Biol, 1996. 16(9): p. 4604-4613.

- Shweiki, D. , Vascular endothelial growth factor induced by hypoxia may mediate hypoxia-initiated angiogenesis. Nature, 1992. 359(6398): p. 843-845.

- Yuxiang Liu, S.R.C. , Toshisuke Morita, and Stella Kourembanas, Hypoxia Regulates Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Gene Expression in Endothelial Cells. Circulation Research, 1995. 77(3): p. 638-643.

- Papandreou, I. , et al., HIF-1 mediates adaptation to hypoxia by actively downregulating mitochondrial oxygen consumption. Cell Metab, 2006. 3(3): p. 187-197. [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L. , et al., Transcriptional regulation of genes encoding glycolytic enzymes by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem, 1994. 269(38): p. 23757-23763.

- Eltzschig, H.K. and P. Carmeliet, Hypoxia and inflammation. N Engl J Med, 2011. 364(7): p. 656-665. [CrossRef]

- P. H. Maxwell, G.U.D., J. M. Gleadle, L. G. Nicholls, A. L. Harris, I. J. Stratford, O. Hankinson, C. W. Pugh, and P. J. Ratcliffe, Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 modulates gene expression in solid tumors and influences both angiogenesis and tumor growth. PNAS, 1997. 94: p. 8104-8109.

- M.E. Hubbi, G.L.S., Regulation of cell proliferation by hypoxia-inducible factors. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol., 2015. 309. [CrossRef]

- S. Rey, G.L.S., Hypoxia-inducible factor-1-dependent mechanisms of vascularization and vascular remodelling. Cardiovasc Res, 2010. 86: p. 236–242. [CrossRef]

- D. Wu et al., Structural characterization of mammalian bHLH-PAS transcription factors Curr Opin Struct Biol., 2016. 43: p. 1-9. [CrossRef]

- K. Hirose et al., cDNA cloning and tissue-specific expression of a novel basic helix-loop-helix/PAS factor (Arnt2) with close sequence similarity to the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (Arnt). Mol Cell Biol., 1996. 16(4): p. 1706-1713.

- M. A. Maynard et al., Human HIF-3alpha4 is a dominant-negative regulator of HIF-1 and is down-regulated in renal cell carcinoma FASEB J, 2005. 19(11): p. 1396-1406. [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, P.H. , et al., The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature, 1999. 399(6733): p. 271-275.

- Epstein, A.C. , et al., C. elegans EGL-9 and mammalian homologs define a family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation. Cell, 2001. 107(1): p. 43-54. [CrossRef]

- W. G. Kaelin Jr et al., The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein and clear cell renal carcinoma Clin Cancer Res., 2007. 13: p. 680s-684s. [CrossRef]

- Ivan, M. , et al., HIFα targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: implications for O2 sensing. Science, 2001. 292(5516): p. 464-468. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.E. , et al., Activation of hypoxia-inducible transcription factor depends primarily upon redox-sensitive stabilization of its α subunit. J Biol Chem, 1996. 271(50): p. 32253-32259.

- Schofield, C.J. and P.J. Ratcliffe, Oxygen sensing by HIF hydroxylases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2004. 5(5): p. 343-354. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, M.A., S. P. Dunning, and H.F. Bunn, Regulation of the erythropoietin gene: evidence that the oxygen sensor is a heme protein. Science, 1988. 242(4884): p. 1412-1415.

- Yuan, Y. , et al., Cobalt inhibits the interaction between hypoxia-inducible factor-α and von Hippel–Lindau protein by direct binding to hypoxia-inducible factor-α. J Biol Chem, 2003. 278(18): p. 15911-15916. [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, P. , et al., Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel–Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science, 2001. 292(5516): p. 468-472. [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L. , HIF-1: mediator of physiological and pathophysiological responses to hypoxia. J Appl Physiol, 2000. 88(4): p. 1474-1480. [CrossRef]

- Mahon, P.C., K. Hirota, and G.L. Semenza, FIH-1: a novel protein that interacts with HIF-1α and VHL to mediate repression of HIF-1 transcriptional activity. Genes Dev, 2001. 15(20): p. 2675-2686. [CrossRef]

- Arany, Z. , et al., An essential role for p300/CBP in the cellular response to hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1996. 93(23): p. 12969-12973. [CrossRef]

- Lando, D. , et al., FIH-1 is an asparaginyl hydroxylase enzyme that regulates the transcriptional activity of hypoxia-inducible factor. Genes Dev, 2002. 16(12): p. 1466-1476. [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.J. , et al., Differential roles of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) and HIF-2α in hypoxic gene regulation. Mol Cell Biol, 2003. 23(24): p. 9361-9374.

- Tian, H., S. L. McKnight, and D.W. Russell, Endothelial PAS domain protein 1 (EPAS1), a transcription factor selectively expressed in endothelial cells. Genes Dev, 1997. 11(1): p. 72-82. [CrossRef]

- Makino, Y. , et al., Inhibitory PAS domain protein (IPAS) is a hypoxia-inducible splicing variant of the hypoxia-inducible factor-3α locus. J Biol Chem, 2002. 277(36): p. 32405-32408. [CrossRef]

- Wenger, R.H. and M. Gassmann, Oxygen(es) and the hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1): Approaching the next level of oxygen sensing. Biol Chem, 1997. 378(7): p. 609-616.

- Kietzmann, T. and A. Gorlach, Reactive oxygen species in the control of hypoxia-inducible factor-mediated gene expression. Semin Cell Dev Biol, 2005. 16(4-5): p. 474-486. [CrossRef]

- Koh, M.Y. and G. Powis, Passing the baton: the HIF switch. Trends Biochem Sci, 2012. 37(9): p. 364-372. [CrossRef]

- Koh, M.Y. , et al., The hypoxia-associated factor switches cells from HIF-1α to HIF-2α-dependent signaling promoting stem cell characteristics, aggressive tumor growth and invasion. Cancer Res, 2011. 71(11): p. 4015-4027.

- Rocha, S. , Gene regulation under low oxygen: holding your breath for transcription. Trends Biochem Sci, 2007. 32(8): p. 389-397. [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L. , Signal transduction to hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Biochem Pharmacol, 2002. 64(5-6): p. 993-998. [CrossRef]

- Rius, J. , et al., NF-κB links innate immunity to the hypoxic response through transcriptional regulation of HIF-1α. Nature, 2008. 453(7196): p. 807-811. [CrossRef]

- Bonello, S. , et al., Reactive oxygen species activate the HIF-1α promoter via a functional NFκB site. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2007. 27(4): p. 755-761. [CrossRef]

- Diebold, I. , et al., The NADPH oxidase subunit NOX4 is a new target gene of the hypoxia-inducible factor-1. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 2010. 21(12): p. 2087-2096. [CrossRef]

- Oliver, K.M., C. T. Taylor, and E.P. Cummins, Hypoxia. Regulation of NFκB signaling during inflammation: the role of hydroxylases. Arthritis Res Ther, 2009. 11(1): p. 215-215. [CrossRef]

- Richard, D.E., E. Berra, and J. Pouysségur, Angiogenesis: how a tumor adapts to hypoxia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 1999. 266(3): p. 718-722. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.T. and E.P. Cummins, The role of NF-κB in hypoxia-induced gene expression. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2009. 1177: p. 178-184. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh et al., Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha-Induced Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1α–β-Catenin Axis Regulates Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I Gene Activation through Chromatin Remodeling. 2013: Mol Cell Biol. p. 2718–2731. [CrossRef]

- K. W. Kim et al., TNF-α upregulates HIF-1α expression in pterygium fibroblasts and enhances their susceptibility to VEGF independent of hypoxia. 2017: Experimental Eye Research, 164, 74–81. [CrossRef]

- S. Tsapournioti et al., TNFα induces expression of HIF-1α mRNA and protein but inhibits hypoxic stimulation of HIF-1 transcriptional activity in airway smooth muscle cells. J Cell Physiol., 2013. 228(8): p. 1745-1753. [CrossRef]

- Y.-J. Jung et al., IL-1beta-mediated up-regulation of HIF-1alpha via an NFkappaB/COX-2 pathway identifies HIF-1 as a critical link between inflammation and oncogenesis FASEB J., 2003. 17(14): p. 2115-2117. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H., K. Chiles, and D. Feldser, Modulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α expression by the epidermal growth factor/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/PTEN/AKT/FRAP pathway in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res, 2000. 60(6): p. 1541-1545.

- Görlach, A. and S. Bonello, The cross-talk between NF-κB and HIF-1: further evidence for a significant liaison. Biochem J, 2008. 412(3): p. e17-e19. [CrossRef]

- E. Laughner et al., HER2 (neu) Signaling Increases the Rate of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1α (HIF-1α) Synthesis: Novel Mechanism for HIF-1-Mediated Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Expression Mol Cell Biol., 2001. 21(12): p. 3995-4004. [CrossRef]

- Treins, C. and et al., Insulin stimulates hypoxia-inducible factor 1 through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/target of rapamycin-dependent signaling pathway. J Biol Chem, 2002. 277(31): p. 27975-27981. [CrossRef]

- R. Kanashiro-Takeuchi et al., Cardiomyocyte-specific expression of HIF-1α mediates the cardioprotective effects of Growth Hormone Releasing Hormone (GHRH). bioRxiv, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Wanschel et al., Oxygen-independent, hormonal control of HIF-1α regulates the developmental and regenerative growth of cardiomyocytes. bioRxiv, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Albanese and et al., The Role of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Post-Translational Modifications in Regulating Its Localisation, Stability, and Activity Int. J. Mol. Sci., 2021. 22(1). [CrossRef]

- J. Bárdos and et al., Negative and positive regulation of HIF-1: A complex network. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer, 2005. 1755(2): p. 107-120. [CrossRef]

- Y. Mizukami et al., ERK1/2 regulates intracellular ATP levels through alpha-enolase expression in cardiomyocytes exposed to ischemic hypoxia and reoxygenation J Biol Chem., 2004. 279(48): p. 50120-50131. [CrossRef]

- Sang, N. and et al., MAPK signaling up-regulates the activity of hypoxia-inducible factors by its effects on p300. J Biol Chem, 2003. 278(16): p. 14013-14019. [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.Y. and J. Loscalzo, MicroRNA-210: a unique and pleiotropic hypoxamir. Cell Cycle, 2010. 9(6): p. 1072-1083. [CrossRef]

- C. Devlin and et al., miR-210: More than a silent player in hypoxia. IUBMB Life, 2011. 63(2): p. 94-100. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X. , Hypoxia-inducible mir-210 regulates normoxic gene expression involved in tumor initiation. Mol Cell, 2009. 35(6): p. 856-867. [CrossRef]

- G. Cao and et al., MiR-210 regulates lung adenocarcinoma by targeting HIF-1α. Heliyon, 2023. 9(5). [CrossRef]

- H. Wang and et al., Negative regulation of Hif1a expression and T H 17 differentiation by the hypoxia-regulated microRNA miR-210 Nature Immunology, 2014. 15: p. 393-401. [CrossRef]

- T. Kelly and et al., A hypoxia-induced positive feedback loop promotes hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha stability through miR-210 suppression of glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1-like Mol Cell Biol, 2011. 31(13): p. 2696-2706. [CrossRef]

- Fasanaro, P. , MicroRNA-210 modulates endothelial cell response to hypoxia and inhibits the receptor tyrosine kinase ligand Ephrin-A3. J Biol Chem, 2008. 283(23): p. 15878-15883. [CrossRef]

- Bruning, U. , MicroRNA-155 promotes resolution of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α activity during prolonged hypoxia. Mol Cell Biol, 2011. 31(19): p. 4087-4096. [CrossRef]

- Risau, W. , Mechanisms of angiogenesis. Nature, 1997. 386(6626): p. 671-674. [CrossRef]

- Carmeliet, P. , Angiogenesis in life, disease and medicine. Nature, 2005. 438(7070): p. 932-936. [CrossRef]

- F. Pipp et al., Elevated fluid shear stress enhances postocclusive collateral artery growth and gene expression in the pig hind limb Aterioscler Thromb Vascular Biol., 2004. 24(9): p. 1664-1668. [CrossRef]

- Helisch, A. and W. Schaper, Arteriogenesis: the development and growth of collateral arteries. Microcirculation, 2003. 10(1): p. 83-97. [CrossRef]

- Z. Peng et al., CCL2 promotes proliferation, migration and angiogenesis through the MAPK/ERK1/2/MMP9, PI3K/AKT, Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways in HUVECs Exp Ther Med., 2022. 25(2). [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, H. , et al., VEGF guides angiogenic sprouting utilizing endothelial tip cell filopodia. Journal of Cell Biology, 2003. 161(6): p. 1163-1177. [CrossRef]

- Phng, L.K. and H. Gerhardt, Angiogenesis: a team effort coordinated by Notch. Developmental Cell, 2009. 16(2): p. 196-208. [CrossRef]

- Lobov, I.B. , et al., Delta-like ligand 4 (Dll4) is induced by VEGF as a negative regulator of angiogenic sprouting. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U S A, 2007. 104(9): p. 3219-3224. [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.H. and K. Alitalo, Molecular regulation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2007. 8(6): p. 464-478. [CrossRef]

- Eilken, H.M. and R.H. Adams, Dynamics of endothelial cell behavior in sprouting angiogenesis. Current Opinion in Cell Biology, 2010. 22(5): p. 617-625. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Mentzer, M.A.K., Intussusceptive Angiogenesis: Expansion and Remodeling of Microvascular Networks Angiogenesis, 2014. 17: p. 499-509. [CrossRef]

- N. Tang et al., Loss of HIF-1alpha in endothelial cells disrupts a hypoxia-driven VEGF autocrine loop necessary for tumorigenesis Cancer Cell, 2004. 6(5): p. 485-495. [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L. , HIF-1 mediates metabolic responses to intratumoral hypoxia and oncogenic mutations. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2013. 123(9): p. 3664-3681. [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, N., H. P. Gerber, and J. LeCouter, The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med, 2003. 9(6): p. 669-676. [CrossRef]

- De Bock, K. , et al., Role of PFKFB3-driven glycolysis in vessel sprouting. Cell, 2013. 154(3): p. 651-663. [CrossRef]

- Yancopoulos, G.D. , et al., Vascular-specific growth factors and blood vessel formation. Nature, 2000. 407(6801): p. 242-248. [CrossRef]

- R. Carlsson et al., Molecular Regulation of the Response of Brain Pericytes to Hypoxia Int. J. Mol. Sci, 2023. 24(6). [CrossRef]

- Carmeliet, P. and R.K. Jain, Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature, 2011. 473(7347): p. 298-307. [CrossRef]

- Urbich, C. and S. Dimmeler, Endothelial progenitor cells: characterization and role in vascular biology. Circ Res, 2004. 95(4): p. 343-353. [CrossRef]

- Ceradini, D.J. and G.C. Gurtner, Homing to hypoxia: HIF-1 as a mediator of progenitor cell recruitment to injured tissue. Trends Cardiovasc Med, 2005. 15(2): p. 57-63. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yin et al., SDF-1alpha involved in mobilization and recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells after arterial injury in mice Cardiovasc Pathol., 2010. 19(4): p. 218-227. [CrossRef]

- Askari, A.T. , et al., Effect of stromal-cell-derived factor 1 on stem-cell homing and tissue regeneration in ischemic cardiomyopathy. Lancet, 2003. 362(9385): p. 697-703. [CrossRef]

- S. Kanki et al., Stromal Cell-Derived Factor-1 Retention and Cardioprotection for Ischemic Myocardium 2011, Circulation: Heart Failure. [CrossRef]

- D. Rath et al., Platelet surface expression of SDF-1 is associated with clinical outcomes in the patients with cardiovascular disease Platelets, 2017. 28(1): p. 34-39. [CrossRef]

- J. Tang et al., Adenovirus-mediated stromal cell-derived factor-1 alpha gene transfer improves cardiac structure and function after experimental myocardial infarction through angiogenic and antifibrotic actions Mol Biol Rep., 2010. 37(4): p. 1957-1969. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E.J. , et al., Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 2019. 139(10): p. e56-e528. [CrossRef]

- Libby, P. , Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature, 2002. 420(6917): p. 868-874. [CrossRef]

- Eelen, G. , et al., Endothelial cell metabolism in normal and diseased vasculature. Circulation Research, 2015. 116(7): p. 1231-1244. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H. , et al., Early expression of angiogenesis factors in acute myocardial ischemia and infarction. N Engl J Med, 2000. 342(9): p. 626-633. [CrossRef]

- G. B. Habib et al., Influence of coronary collateral vessels on myocardial infarct size in humans. Results of phase I thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) trial. The TIMI Investigators Circulation, 1991. 83(3): p. 739-746. [CrossRef]

- J. Elias et al., Impact of Collateral Circulation on Survival in ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Patients Undergoing Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention With a Concomitant Chronic Total Occlusion. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions, 2017. 10(9). [CrossRef]

- A. Heinl-Green et al., The efficacy of a ‘master switch gene’ HIF-1α in a porcine model of chronic myocardial ischaemia European Heart Journal, 2005. 26(13) p. 1327-1332. [CrossRef]

- Milkiewicz, M., C. W. Pugh, and S. Egginton, Inhibition of endogenous HIF inactivation induces angiogenesis in ischaemic skeletal muscles of mice. J Physiol, 2004. 560(Pt 1): p. 21-26. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Hlatky et al., Polymorphisms in hypoxia inducible factor 1 and the initial clinical presentation of coronary disease Am Heart J., 2007. 154(6): p. 1035-1042. [CrossRef]

- A. López-Reyes et al., The HIF1A rs2057482 polymorphism is associated with risk of developing premature coronary artery disease and with some metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors. The Genetics of Atherosclerotic Disease (GEA) Mexican Study. Experimental and Molecular Pathology, 2014. 96(3). [CrossRef]

- L.-F. Wu et al., The association between hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit alpha gene rs2057482 polymorphism and cancer risk: a meta-analysis BMC Cancer, 2019. 19. [CrossRef]

- X. Guo et al., SNP rs2057482 in HIF1A gene predicts clinical outcome of aggressive hepatocellular carcinoma patients after surgery Scientific Reports, 2015. 5. [CrossRef]

- C. Chaar et al., Systematic review and meta-analysis of the genetics of peripheral arterial disease JVS Vasc Sci., 2023. 5. [CrossRef]

- A. H. Borton et al., Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Nuclear Translocator in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Is Required for Optimal Peripheral Perfusion Recovery J Am Heart Assoc., 2018. 7(11). [CrossRef]

- Tuomisto, T.T. , HIF-VEGF-VEGFR-2, TNF-α and IGF pathways are upregulated in critical human skeletal muscle ischemia as studied with DNA array. Atherosclerosis, 2004. 174(1): p. 111-120. [CrossRef]

- Annex, B.H. , Therapeutic angiogenesis for critical limb ischaemia. Nat Rev Cardiol, 2013. 10(7): p. 387-396. [CrossRef]

- O'Gara, P.T. , et al., 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation, 2013. 127(4): p. e362-e425. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, F.J. , et al., 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J, 2019. 40(2): p. 87-165. [CrossRef]

- Powers, W.J. , et al., 2018 Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke, 2018. 49(3): p. e46-e110. [CrossRef]

- Conte, M.S. , et al., Global vascular guidelines on the management of chronic limb-threatening ischemia. J Vasc Surg, 2019. 69(6S): p. 3S-125S.e40.

- Jude, E.B., I. Eleftheriadou, and N. Tentolouris, Peripheral arterial disease in diabetes—a review. Diabet Med, 2010. 27(1): p. 4-14. [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L. , Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer, 2003. 3(10): p. 721-732. [CrossRef]

- Takeda, K., A. Cowan, and G.H. Fong, Essential role for prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2 in oxygen homeostasis of the adult vascular system. Mol Cell Biol, 2007. 27(21): p. 7179-7185.

- M. T. Rishi et al., Deletion of prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins (PHD1, PHD3) stabilizes hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha, promotes neovascularization, and improves perfusion in a murine model of hind-limb ischemia. Microvascular Research, 2015. 97: p. 181-188. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhang et al., Localized Delivery of shRNA against PHD2 Protects the Heart from Acute Myocardial Infarction through Ultrasound-Targeted Cationic Microbubble Destruction Theranostics, 2017. 7(1): p. 51-66. [CrossRef]

- M. Huang et al., Short hairpin RNA interference therapy for ischemic heart disease. Circulation, 2008. 118: p. S226-S233. [CrossRef]

- Milkiewicz, M., C. W. Pugh, and S. Egginton, Inhibition of endogenous HIF inactivation induces angiogenesis in ischaemic skeletal muscles of mice. Journal of Physiology, 2004. 560(Pt 1): p. 21-26. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Pradeep et al., Protective Effect of Cardiomyocyte-Specific Prolyl-4-Hydroxylase 2 Inhibition on Ischemic Injury in a Mouse MI Model J Am Coll Surg., 2022. 235(2): p. 240-254. [CrossRef]

- M. Thirunavukkarasu et al., Stabilization of Transcription Factor, HIF-1α by Prolylhydroxylase 1 Knockout Reduces Cardiac Injury After Myocardial Infarction in Mice Cells, 2025. 14(6). [CrossRef]

- M. Huang et al., Double Knockdown of Prolyyl Hydroxylase and Factor Inhibiting HIF with Non-Viral Minicircle Gene Therapy Enhances Stem Cell Mobilization and Angiogenesis After Myocardial Infarction Circulation, 2011. 124: p. S46-S54. [CrossRef]

- L. Xie et al., Depletion of PHD3 Protects Heart from Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury by Inhibiting Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis J Mol Cell Cardiol., 2015. 80: p. 156-165. [CrossRef]

- R. Tiwari et al., Chemical inhibition of oxygen-sensing prolyl hydroxylases impairs angiogenic competence of human vascular endothelium through metabolic reprogramming. iScience, 2022. 25(10). [CrossRef]

- E. Olson et al., Short-term treatment with a novel HIF-prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor (GSK1278863) failed to improve measures of performance in subjects with claudication-limited peripheral artery disease Vasc Med., 2014. 19(6): p. 473-482. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu et al., Advances in the study of exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells and cardiac cells for the treatment of myocardial infarction Cell Commun Signal, 2023. 21. [CrossRef]

- H. Shigematsu et al., Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of hepatocyte growth factor plasmid for critical limb ischemia Gene Ther., 2010. 17(9): p. 1152-1161. [CrossRef]

- S. Rajagopalan et al., Regional angiogenesis with vascular endothelial growth factor in peripheral arterial disease: a phase II randomized, double-blind, controlled study of adenoviral delivery of vascular endothelial growth factor 121 in patients with disabling intermittent claudication Circulation, 2003. 108(16): p. 1933-1938. [CrossRef]

- P. Barć et al., Double VEGF/HGF Gene Therapy in Critical Limb Ischemia Complicated by Diabetes Mellitus. J Cardiovasc Transl Res, 2021. 14(3). [CrossRef]

- W. Xue et al., Cardiac-Specific Overexpression of HIF-1α Prevents Deterioration of Glycolytic Pathway and Cardiac Remodeling in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Mice Am J Pathol, 2010. 177(1): p. 97-105. [CrossRef]

- M. Kido et al., Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1-Alpha Reduces Infarction and Attenuates Progression of Cardiac Dysfunction After Myocardial Infarction in the Mouse. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2005. 46(11): p. 2116-2124. [CrossRef]

- K. Shyu et al., Intramyocardial injection of naked DNA encoding HIF-1alpha/VP16 hybrid to enhance angiogenesis in an acute myocardial infarction model in the rat Cardiovascular Res, 2002. 54(3): p. 576-583. [CrossRef]

- Czibik et al., In vivo Remote Delivery of DNA Encoding for Hypoxia-inducible Factor 1 Alpha Reduces Myocardial Infarct Size. American Society for Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 2009. 2(1): p. 33-40. [CrossRef]

- K. Sarkar et al., Adenoviral transfer of HIF-1α enhances vascular responses to critical limb ischemia in diabetic mice PNAS, 2009: p. 18769-18774. [CrossRef]

- M. Creager et al., Effect of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α Gene Therapy on Walking Performance in Patients With Intermittent Claudication Circulation, 2011. 124. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X. , et al., Transplantation of hypoxia-preconditioned mesenchymal stem cells improves infarcted heart function via enhanced survival of implanted cells and angiogenesis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 2008. 135(4): p. 799-808. [CrossRef]

- I. Rosová et al., Hypoxic Preconditioning Results in Increased Motility and Improved Therapeutic Potential of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Stem Cells, 2008. 26(8): p. 2173-2182. [CrossRef]

- J. Garcia et al., Hypoxia-preconditioning of human adipose-derived stem cells enhances cellular proliferation and angiogenesis: A systematic review J Clin Transl Res, 2022. 8(1): p. 61-70. [CrossRef]

- X. Pei et al., Local delivery of cardiac stem cells overexpressing HIF-1α promotes angiogenesis and muscular tissue repair in a hind limb ischemia model. Journal of Controlled Release, 2020. 322: p. 610-621. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Lai et al., Exosome secreted by MSC reduces myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury Stem Cell Res, 2010. 4(3): p. 214-222.

- T. Chen et al., MicroRNA-31 contributes to colorectal cancer development by targeting factor inhibiting HIF-1α (FIH-1) Cancer Biol Ther, 2014. 15(5): p. 516-523. [CrossRef]

- P. P. Parikh, R.M.L.-S., H. Shao et al.,, Intramuscular E-selectin/adeno-associated virus gene therapy promotes wound healing in an ischemic mouse model J Surg Res, 2018: p. 68-76. [CrossRef]

- HJ, Q., P. Parikh, RM. Lassance-Soares et al.,, Gangrene, revascularization, and limb function improved with E-selectin/adeno-associated virus gene therapy JVS Vasc Sci, 2020. 2: p. 20-32. [CrossRef]

- HJ. Quiroz, F.S., H. Shao et al.,, E-Selectin-Overexpressing Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy Confers Improved Reperfusion, Repair, and Regeneration in a Murine Critical Limb Ischemia Model Front Cardiovasc Med, 2022. 8:826687. [CrossRef]

- A. Ribieras, Y.Y.O., Y. Li, et al.,, E-Selectin/AAV2/2 Gene Therapy Alters Angiogenesis and Inflammatory Gene Profiles in Mouse Gangrene Model Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 2022. 9. [CrossRef]

- A. Ribieras, Y.O., Y. Li et al.,, E-Selectin/AAV Gene Therapy Promotes Myogenesis and Skeletal Muscle Recovery in a Mouse Hindlimb Ischemia Model Cardiovasc Ther, 2023: p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- CT. Huerta, Y.O., Li Y, et al.,, Novel Gene-Modified Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy Reverses Impaired Wound Healing in Ischemic Limbs Ann Surg, 2023. 278: p. 383-395. [CrossRef]

- F. Voza, Y.O., Y. Li, et al.,, Codon-Optimized and de novo-Synthesized E-Selectin/AAV2 Dose-Response Study for Vascular Regeneration Gene Therapy Ann Surg, 2024. 280(4): p. 570-583. [CrossRef]

- Le Jan, S. , et al., Angiopoietin-Like 4 Is a Proangiogenic Factor Produced during Ischemia and in Conventional Renal Cell Carcinoma. Am J Pathol, 162, 1521-1528 (2003).

- A. Mammoti, et al., Endothelial Twist1-PDGFB signaling mediates hypoxia- induced proliferation and migration of αSMA-positive cells. Scientific Reports, 10, 7563 (2020). [CrossRef]

- G. Seghezzi, et al., Fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) induces vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in the endothelial cells of forming capillaries: an autocrine mechanism contributing to angiogenesis. J Cell Biol, 141, 1659-1673 (1998). [CrossRef]

- A. Luttun, et al., Revascularization of ischemic tissues by PlGF treatment, and inhibition of tumor angiogenesis, arthritis and atherosclerosis by anti-Flt1. Nature Medicine, 8, 831-840 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, et al., MMP-2 and MMP-9 contribute to the angiogenic effect produced by hypoxia/15-HETE in pulmonary endothelial cells. J Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, 121, 36-50 (2018). [CrossRef]

- E. Revuelta-López, et al., Hypoxia Induces Metalloproteinase-9 Activation and Human Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Migration Through Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor–Related Protein 1–Mediated Pyk2 Phosphorylation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Bio, 33, 2877-2887 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Y. S. Park et al., Expression of angiopoietin-1 in hypoxic pericytes: Regulation by hypoxia-inducible factor-2α and participation in endothelial cell migration and tube formation. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2, 263-269 (2016). [CrossRef]

| Target Gene | Function | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| VEGF (VEGFA) | Stimulates endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and new blood vessel formation | [9] |

| ANGPT1 (Angiopoietin-1) | Stabilizes blood vessels and promotes maturation via Tie2 receptor | [158] |

| ANGPTL4 (angiopoietin-related protein 4) | Regulates vascular permeability and enhances endothelial cell survival | [152] |

| PDGFB (platelet-derived growth factor B) | Recruits pericytes and smooth muscle cells for vessel stabilization | [153] |

| FGF2 (Basic fibroblast growth factor) | Promotes proliferation and differentiation of endothelial cells | [154] |

| SDF-1 (CXCL12) | Attracts endothelial progenitor cells to ischemic tissue | [91] |

| PIG (Placental growth factor) | Enhances VEGF-driven angiogenesis and inflammatory cell recruitment | [155] |

| EPO (Erythropoietin) | Indirectly promotes angiogenesis by enhancing red blood cell mass and oxygen delivery | [3] |

| MMP2 (Matrix metalloproteinase-2) | Degrades extracellular matrix for endothelial migration and angiogenic sprouting | [156] |

| MMP9 (Matrix metalloproteinase-9) | Facilitates basement membrane remodeling during angiogenesis | [157] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).