1. Introduction

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence has profoundly influenced numerous professional fields with its integration into medical education emerging as a significant driver of change (Krive et al., 2023; Narayanan et al., 2023). AI-powered tools are increasingly integrated into diagnostics, administrative tasks, and clinical decision-making (Chen et al., 2025; Saroha,2025). There is a need to continuously assess AI’s potential to enhance traditional teaching methods and prepare future healthcare professionals for these evolving technologies This integration necessitates a comprehensive assessment of its application within specific medical disciplines, such as anatomy, to delineate both opportunities and challenges (Saroha,2025). Specifically, within the context of anatomy education, AI presents unparalleled opportunities for tailoring learning experiences, allowing students to explore intricate spatial relationships and functional interdependencies through innovative approaches. This pedagogical transformation driven by AI extends beyond mere visualization, offering dynamic platforms for interactive learning and real time feedback that were previously unattainable (Mir et al., 2023). In medical education, the development of accurate and efficient assessment instruments is paramount for gauging students’ understanding and retention of challenging subjects, such as anatomy (Can & Toraman, 2022). Traditional assessment methods predominantly utilizing multiple-choice questions are instrumental in this evaluation process (Grevisse, 2024).

Anatomy is universally acknowledged as the most foundational and historically significant discipline within the medical sciences, providing a critical basis for understanding clinical challenges and serving as a prerequisite for all subsequent medical fields (Farrokhi et al., 2017; Papa & Vaccarezza, 2013; Zhang et al., 2023). Despite its fundamental significance, there are ongoing discussions concerning the challenges encountered in anatomy education and the resultant need for effective pedagogical and assessment methodologies (Chan et al., 2022; Cheung et al., 2021). The emergence of sophisticated large language models such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT has spurred considerable interest in their potential applications within educational settings, encompassing areas like content creation, individualized learning pathways, and assessment support (Kasneci et al., 2023; Kung et al., 2023; Sharma et al., 2023). LLM’s have shown capability in performing various medical tasks, including responding to medical knowledge inquiries and aiding in diagnostic procedures (Au & Yang, 2023; Chen et al., 2025). Research has examined ChatGPT’s performance on comprehensive medical assessments, such as the United States Medical Licensing Examination, indicating its potential utility in medical education and clinical decision-making (Gilson et al., 2023; Kung et al., 2023; Sharma et al., 2023). Moreover, LLM’s have been assessed for their proficiency in generating and responding to multiple-choice questions within specialized medical domains such as dermatology and cardiology (Ayub et al., 2023; Hariri, 2023; Meo et al., 2023) and even specifically in anatomy education (Ilgaz & Celik, 2023). Despite the general capability of large language models being noteworthy, their precise performance and dependability within specialized, knowledge- intensive domains such as anatomy warrant empirical investigation.

Considering anatomy’s fundamental role in medical education and the precision required for accurate anatomical comprehension, it is crucial to rigorously evaluate the proficiency of AI models, specifically ChatGPT, in addressing the complexities inherent in anatomical multiple- choice questions. This study aimed to assess the accuracy and utility of artificial intelligence platforms specifically large language models in managing anatomy content for medical college assessments. The objective of the study was to critically assess the efficacy of ChatGPT in responding to multiple-choice questions pertaining to anatomy. This research aimed to offer insights into the current capabilities of large language models in anatomical assessment and their potential implication for medical education by systematically evaluating their accuracy and limitations against a curated set of anatomic-specific multiple-choice questions. This study analyzes ChatGPT’s capacity to accurately answer multiple-choice questions across core medical disciplines such as anatomy, histology, microbiology, pathology and physiology. This study hypothesizes that Chat GPT will achieve a higher correct response rate than would be expected by chance, based on the official answer key derived from year 1 mid-term and final year examination. Furthermore, the research examines potential variations in Chat GPT’s performance across distinct academic disciplines. The evaluation of ChatGPT’s performance in these assessments can provide insight into its potential as a tool for medical education and self-directed learning. Moreover, the study’s outcomes will offer insights into the practical utility and potential obstacles associated with incorporating such artificial intelligence tools into academic evaluation frameworks thereby guiding educators and curriculum designers in the judicious implementation of AI within anatomy learning and assessment processes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Settings

The present cross-sectional study was conducted in the Department of Anatomy, College of Medicine, King Faisal University, AlAhsa, Saudi Arabia in August 2025. For AI performance evaluation, we used ChatGPT (GPT-5, OpenAI, San Francisco, CA; accessed August 2025 via

https://chat.openai.com).

2.2. Establishment of Multiple-Choice Question Bank

The research team members prepared the MCQ bank based on the questions from the mid-term and final exams of the first year. In College of Medicine, King Faisal University, the curriculum is PBL, integrated and student-centered. The disciplines in year 1 include Anatomy, Histology Microbiology, Pathology and Physiology. The research team members carefully reviewed the MCQ’s (420) content so that the MCQs were relevant to the subject contents. MCQs evaluated for quality, and it was ensured that the MCQs were unambiguous with only one correct answer. The language was simple and easy to understand. The investigator team members also proofread the MCQs for any errors, typos, confusing or misleading statements or inconsistencies. It was also checked that the options were well-constructed with no clear hints or clues within the stem. Once the investigators were satisfied with the preparation of MCQ pool (219) and its quality, all questions were compiled into the final exam format for each discipline after final selection.

2.3. Selection of Multiple-Choice Questions

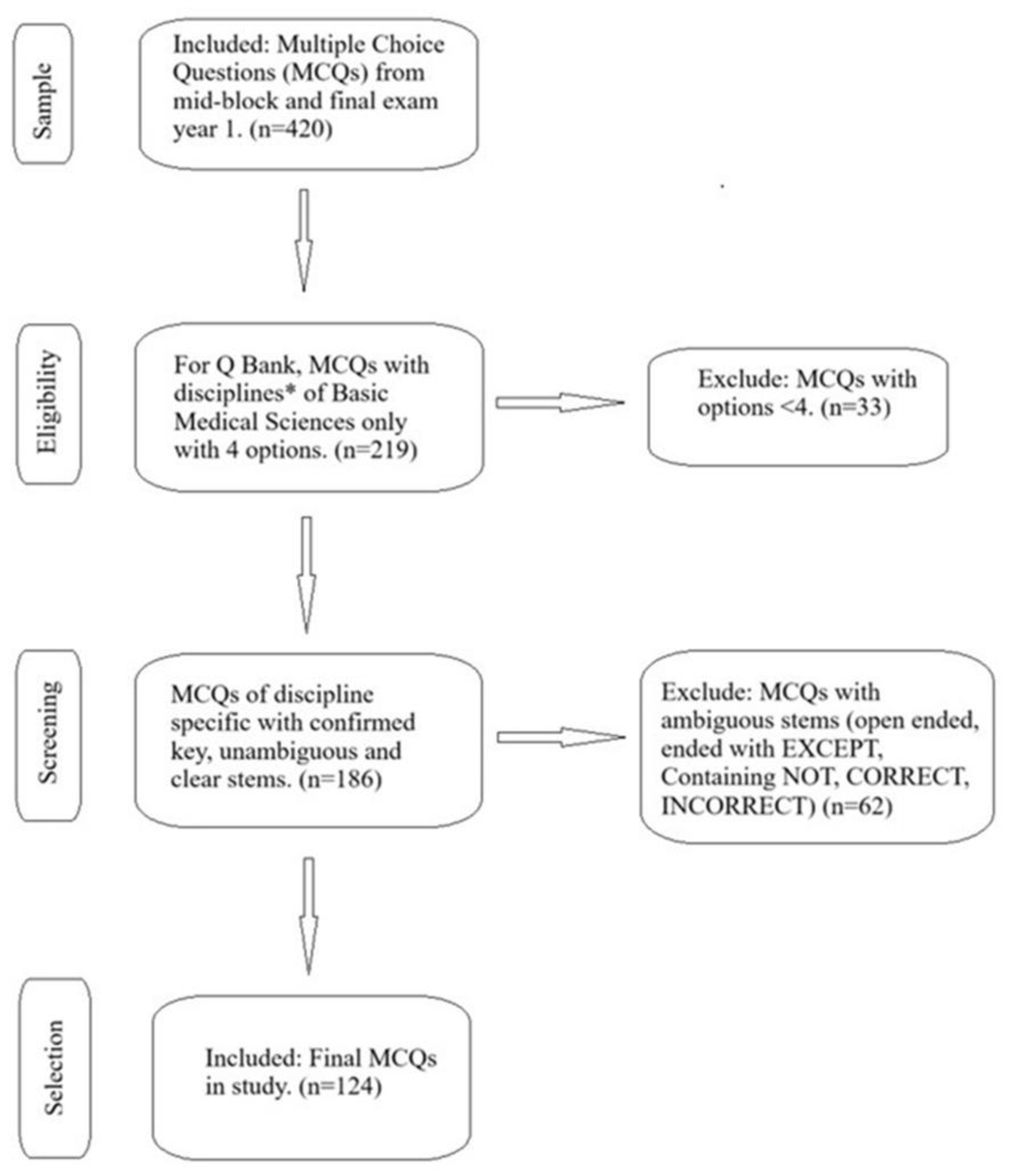

The MCQs in various disciplines of basic medical sciences were selected from the MCQ bank. Out of 219 MCQs in various disciplines of basic medical sciences, 124 MCQ’s were selected (

Table 1) based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria (

Figure 1). The research team members from basic medical sciences carefully checked all the MCQs and their answer keys.

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion of MCQS

Each question with a single best answer was selected from the MCQ’s pool. MCQs which were not related to the specific subject area of basic medical sciences, with misleading or open-ended stems, repetition, without appropriate scenarios and with biased answer keys were excluded from the study. The MCQs with less than four options were also excluded. MCQs with stem having words like “NOT”, “INCORRECT”, “CORRECT” or “EXCEP” were also excluded from the final selection for the ChatGPT performance (

Figure 1).

2.5. Preparation of Test Paper for ChatGPT

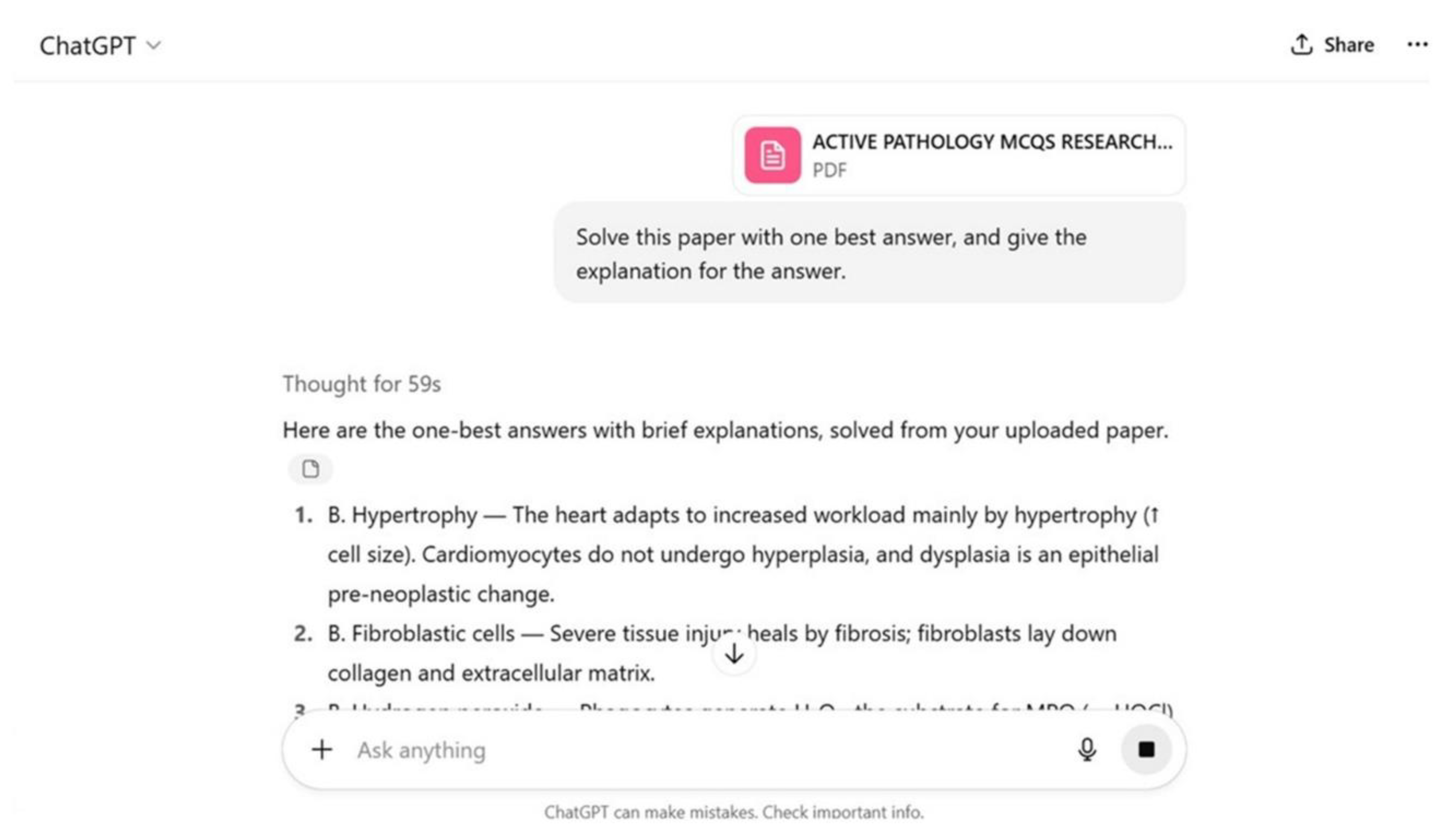

The MCQs were formatted into a test paper of each discipline and converted into a PDF document. The MCQs were entered by attaching each PDF document to ChatGPT one by one (

Figure 2).

2.6. Score System

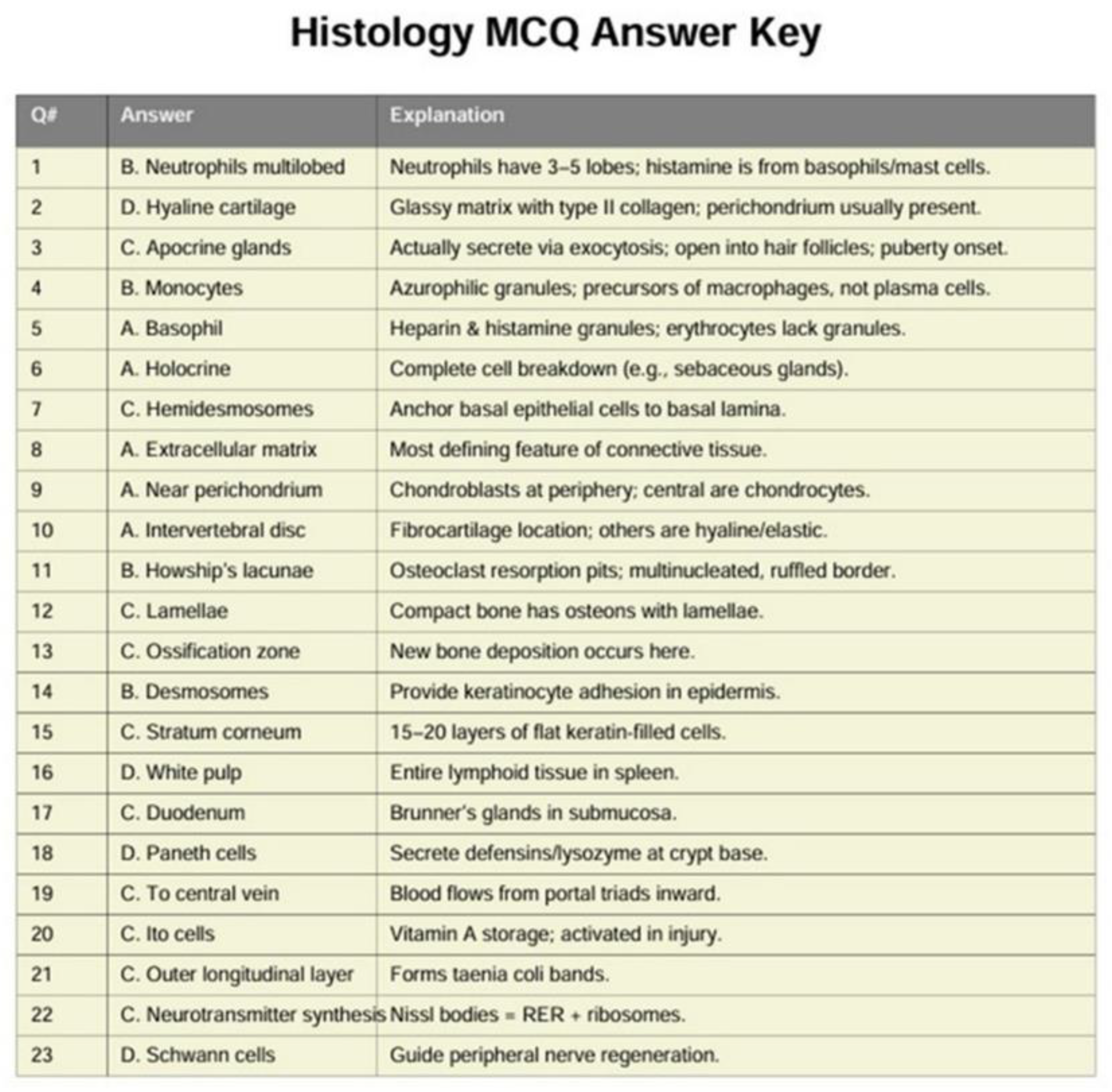

The questions were used as input in ChatGPT and the responses that the tool gave were stored in a separate ChatGPT PDF file (

Figure 3). The first response that was obtained, taken as the final response, and we did not use the choice of “regenerate response”. Based on a pre-determined answer key, scoring was executed on a scale of 0 to 1, with 0 representing incorrect and 1 representing correct. Responses of ChatGPT for papers of disciplines (anatomy; histology microbiology; pathology and physiology) of Year 1 were saved along with the key in separate excel file for data analysis.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The data was carefully reviewed and analyzed. The analysis was based on each question and its response. ChatGPT’s performance was quantified by contrasting its responses with the established answer key derived from the first-year mid-term and final examinations. Each response was evaluated on a binary scale (correct or incorrect), and overall accuracy was determined by the ratio of correctly answered questions. Additionally, accuracy was examined across the five disciplines. The descriptive statistical analysis was done using numbers and percentages. In addition to descriptive statistics (numbers and percentages) 95% confidence interval were calculated for accuracy rates using Wilson’s core method, to provide an estimate of statistical precision and reproducibility. Furthermore, errors were tabulated analyzed to identify mode of failure in each discipline.

2.8. Ethical Approval

ChatGPT is an open-source digital instrument available to individuals who register on its dedicated online website. Ethical approval was taken due to the use of MCQs from the mid-term and final exam original papers for year 1 students (academic year 24-25) of College of Medicine, King Faisal University with reference number KFU-REC-2023-DEC-ETHICS1792.

3. Results

The present study details the analytical outcomes, revealing a high overall accuracy of ChatGPT across multiple basic science disciplines, with a primary focus on its accuracy in answering anatomy-related multiple-choice questions (MCQs). A total of 124 MCQs were administered across five disciplines: Anatomy, Histology, Microbiology, Pathology and Physiology. The overall performance of ChatGPT across all 124 questions from the five disciplines was exceptionally high, 121 correct answers, with 95% confidence interval of 93.4–99.1% (

Table 2).

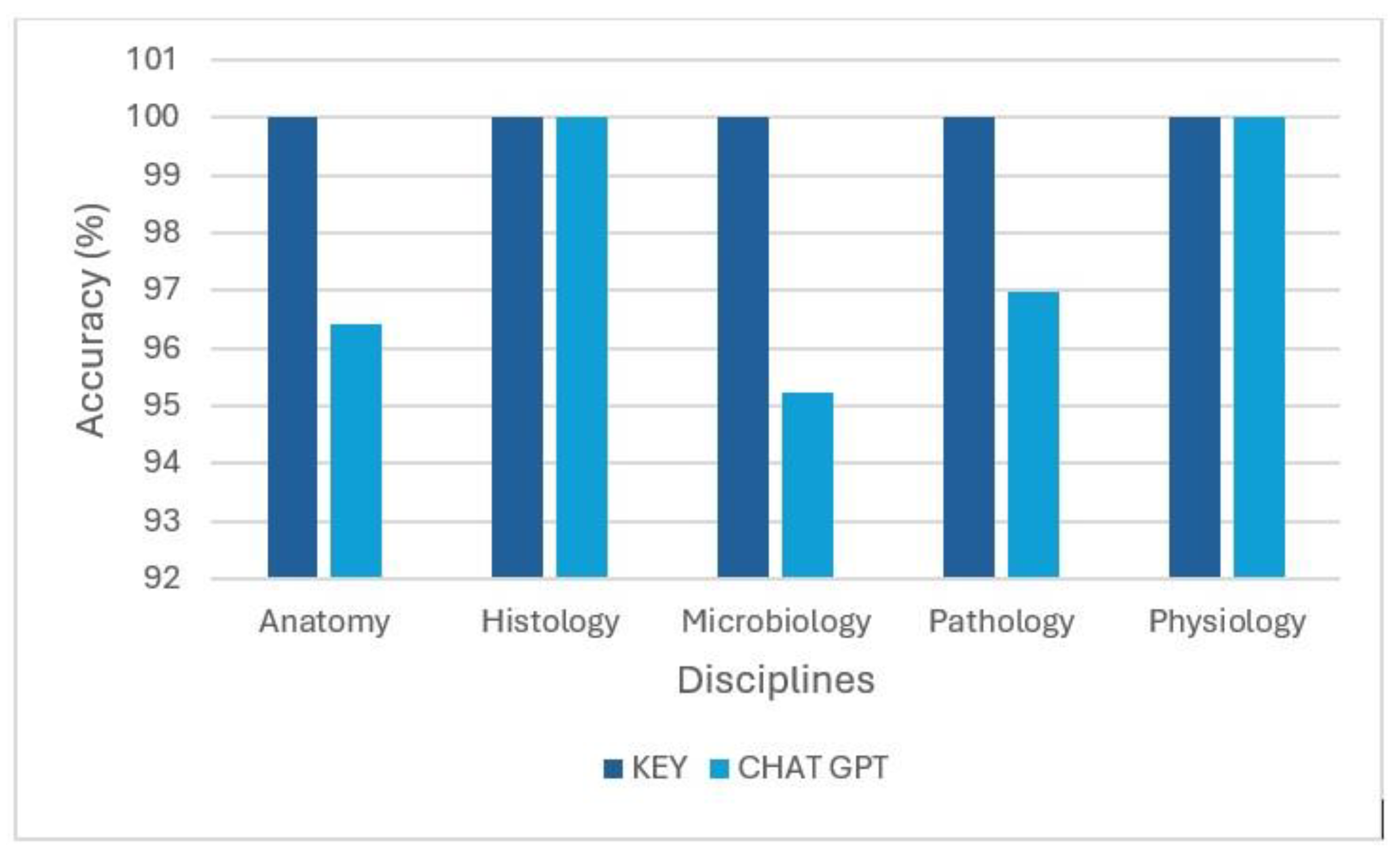

ChatGPT demonstrated a high level of accuracy across all evaluated basic medical science disciplines. For anatomy, ChatGPT achieved a score of 27 out of 28, corresponding to an accuracy rate of 96%. This indicates a strong performance in the domain of anatomical knowledge. When compared to other disciplines, ChatGPT’s performance in anatomy was slightly lower than in histology (100%) and physiology (100%) but comparable to pathology (97%) and microbiology (95%). This resulted in an exceptionally high cumulative accuracy of 98% across all five disciplines (

Figure 4) demonstrating ChatGPT’s consistent performance.

Figure 4 illustrates ChatGPT’s comparative performance across disciplines, highlighting its consistently high accuracy and demonstrating that Anatomy performance was nearly equivalent to other basic sciences. The achieved accuracy of 96% in Anatomy alongside 100% in Histology and Physiology, 97% in Pathology and 95% in Microbiology indicates the model’s high proficiency across these foundational medical disciplines when answering these MCQ’s.

The error analysis identified the mode of failure in each discipline. Highlighted areas of occasional mistakes and strengths allowed a clearer understanding of ChatGPT’s performance across different subject domains (

Table 3).

Only three errors were found overall in the 124 questions via error analysis. Instead of demonstrating systematic deficiencies, the mode of failure study (

Table 3), showed that these errors were isolated and did not cluster within particular content areas.

4. Discussion

The aim of this research was to assess ChatGPT’s proficiency in responding to multiple-choice anatomy questions, thereby evaluating its capabilities and potential impact on medical education. In our assessment ChatGPT demonstrated a notable accuracy of 96% correctly answering 27 out of 28 anatomical multiple-choice questions. This level of performance is particularly significant given the fundamental role and inherent complexity of anatomy within medical education. This high level of accuracy suggests that advanced language models such as ChatGPT function as effective supplementary resources for students, facilitating self-assessment and reinforcing knowledge in core medical science subjects (Meo et al., 2023). Across the five foundational medical science disciplines, Anatomy Histology, Microbiology, Pathology and Physiology, the model exhibited outstanding performance, achieving an overall accuracy rate of 98% (121 out of 124). The model achieved 100% score in Histology and Physiology, further validating its capacity for accurate factual recall and comprehension. This strong performance across diverse subjects underscores the potential of large language models to provide reliable informational support across a broad spectrum of preclinical medical education (Ilgaz & Çelik, 2023). These findings are consistent with research indicating strong performance by large language models in medical knowledge assessments. Studies by Gilson et al. (2023), Kung et al. (2023), and Sharma et al. (2023), have shown that ChatGPT achieves scores at or near the passing threshold on the United States Medical Licensing Examination, suggesting a substantial understanding of core medical concepts.

However, it is crucial to acknowledge that while impressive, such high accuracy does not equate to perfect understanding or clinical reasoning, as AI (LLM) is prone to generating plausible but inaccurate information, a phenomenon known as confabulation (Lai et al., 2023). Therefore, it is imperative to implement robust validation mechanisms to verify the factual correctness of information provided by AI, especially in high-stakes environments like medical education, where misinformation could have serious implications for patient safety (Mishra et al., 2025). Despite these limitations, the near-passing threshold performance of AI on standardized medical examinations like USMLE suggests its potential utility in assisting with medical education and even clinical decision-making (Kasneci et al., 2023; Kung et al., 2023; Sharma et al., 2023). Similarly, research in specialized medical domains such as dermatology and cardiology has indicated a high level of proficiency in generating and responding to multiple-choice questions (Ayub et al., 2023; Hariri, 2023; Meo et al., 2023). Our findings, which show a 96% accuracy rate in Anatomy, align with existing literature by providing specific evidence that ChatGPT can reliably process knowledge of anatomical structures, their interrelationships, and their functions. This further corroborates the potential for AI to serve as valuable educational tools, particularly for foundational knowledge acquisition and assessment in complex medical subjects (Brin et al., 2023; Clusmann et al., 2023).

Conversely, some studies in existing literature highlight the necessity for a cautious approach. Bolgova et al. (2023) investigated ChatGPT’s performance on gross anatomy MCQs (GPT-3.5), reporting an average accuracy rate of 44.1%. Its overall performance in gross anatomy fell short of the passing requirements for examinations like the Chinese National Medical Licensing Examination (Bolgova et al., 2023). In another study, across all eight assessments, neither ChatGPT 3.5 nor 4 provided responses that accurately described the scalenovertebral triangle. This lack of alignment could impede novice medical students’ ability to discern correct anatomical information, potentially leading to misinterpretations (Singal & Goyal 2024). A scoping review conducted by Sharma et al. (2024) also indicated that while ChatGPT can excel in recalling factual in-formation, its performance diminishes when faced with tasks that necessitate higher order cognitive processing, three-dimensional spatial reasoning, or the interpretation of radiological and cadaveric imagery. These outcomes contrast with exceptionally high scores observed in our study, thereby highlighting the impact of study design and question characteristics on the model’s performance. These discrepancies underscore the importance of evaluating AI with diverse assessment methodologies and content types to comprehensively understand its capabilities and limitations (Rosoł et al., 2023). The omission of image-based questions in specific studies, including aspects of our own research, inherently constrains the evaluation’s breadth, as visual interpretation is vital to many medical fields, notably radiology (Gotta et al., 2024).

The strong performance observed in this study may be attributed to the methodological rigor employed in the curation of multiple-choice question bank. Only un-ambiguous, single best answer questions were included, while items with “NOT”, “EXCEPT”, or other potentially confusing elements were excluded. Furthermore, scenario-based questions were meticulously chosen to evaluate factual and conceptual recall, deliberately omitting the necessity for image interpretation. This methodological approach minimized ambiguity, allowing ChatGPT to achieve optimal performance. Conversely, research employing unrestricted exam repositories, which encompass questions requiring integrated reasoning, might have documented lower accuracy rates. Therefore, our findings accentuate ChatGPT’s proficiency in structured, precisely formulated knowledge assessments characteristics of early medical curriculum. This emphasizes the critical role of question design and assessment modality in accurately gauging the capabilities of AI in specialized domains. Furthermore, it underscores the need for a granular subclassification of question types such as factoid, procedural, causal, and comparative questions, to comprehensively explore the nuanced performance of AI across diverse medical examination scenarios (Knoedler et al., 2024).

The single instance of an incorrect answer within the anatomy section warrants a detailed qualitative examination. An analysis to ascertain whether this inaccuracy arose from subtle interpretational challenges, inherent limitations of the model concerning a specific anatomical detail, or structural ambiguities within the question itself could provide valuable insights for refining AI tools intended for educational applications. Such detailed examination is crucial given that AI, despite exhibiting high accuracy, often employ confident language even when providing incorrect responses, which can mislead users who trust the model’s output as the sole source of information (Gotta et al., 2024).

The educational ramifications of these discoveries are considerable. Given its established high accuracy ChatGPT possesses the potential to function as a beneficial ancillary resource in anatomy instruction, offering prompt, dependable feedback, serving as an intelligent tutor for knowledge retention and aiding educators in curriculum development and examination strategy. However, while ChatGPT can be valuable supplementary tool for learning and assessment in medical education, especially for foundational knowledge, its current limitations in complex reasoning and visual interpretation necessitate careful integration and human oversight (Lai et al., 2023; Scherr et al., 2023). Educators must recognize that AI’s utility is primarily in augmenting, not replacing traditional pedagogical methods especially in disciplines requiring critical thinking, problem solving, and nuanced interpretation of complex medical cases. Furthermore, future research should explore the development of hybrid custom models that combine AI-driven preliminary evaluations with human expert review, thereby leveraging the efficiency of AI while ensuring the strong validation of complex medical knowledge (Grévisse, 2024). The implementation of AI for pre-testing examination questions could also significantly reduce the number of ambiguous or factually incorrect items, enhancing the reliability and fairness of medical assessments (Roos et al., 2023). Consistent with previous findings, AI technologies can potentially boost student involvement and facilitate tailored educational pathways. However, as highlighted by Kasneci et al. (2023) and Krive et al. (2023), AI should be considered an adjunct to, rather than a substitute for established teaching methodologies. Critical thinking in clinical settings, spatial cognition, hands-on proficiencies, and the cultivation of professional qualities like empathy necessitate guidance from human mentors and practical experiences that AI cannot emulate.

The findings of this study should be interpreted within the context of several limitations. Although the multiple-choice question bank was meticulously curated and validated by subject matter experts, it represents a specific subset of questions derived from a single institution’s curriculum, which may restrict the generalizability of the result. The high accuracy observed may be attributed to the limited scope of the assessment specifically the comparatively small number of questions per discipline and the omission of image-based queries, complex clinical scenarios, and advanced reasoning challenges. The evaluation was confined to a single iteration of ChatGPT, and subsequent model advancements or the utilization of its iterative refinement features could potentially alter the observed results. Future investigations should incorporate more extensive and varied question repositories, incorporate the interpretation of visual data and practical clinical reasoning, and conduct direct comparisons of model performance against that of medical students to more effectively contextualize its function within medical education.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, ChatGPT demonstrated exceptional accuracy on anatomy multiple-choice questions, aligning with or surpassing its performance in other basic medical sciences. Analysis of 95% confidence intervals and error patterns indicate that its performance is both statistically reliable and consistent with very few isolated errors and no systematic biases. These findings highlight its potential utility as a supportive educational instrument in anatomy and preclinical education. However, thoughtful integration, mindful of its limitation, is crucial to maximizing its benefits while preserving the comprehensive aims of medical education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.K. and N.A.; methodology, N.K.; software, N.K.; validation, N.K. and N.A.; formal analysis, N.K.; resources, N.A.; data curation, N.K. and N.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.K.; writing—review and editing, N.K.; visualization, N.A.; supervision, N.A.; project administration, N.A.; funding acquisition, N.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research to be funded by “The Deanship of Scientific Research and The Vice President for Graduate Studs and Scientific Research”, King Faisal University, Al Ahsa, Saudi Arabia after the publication of research. Funding by researchers after the acceptance of article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing does not apply to this article. Data are contained within this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge “The Deanship of Scientific Research and The Vice President for Graduate Studs and Scientific Research”, King Faisal University for their support in covering the costs of publication for this research paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| USMLE |

United States Medical Licensing Examination |

| MCQs |

Multiple Choice Questions |

| PBL |

Problem Solving Learning |

| LLMs |

Large Learning Models |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Au, K. F., & Yang, W. (2023). Auxiliary use of ChatGPT in surgical diagnosis and treatment. International Journal of Surgery. [CrossRef]

- Ayub, I., Hamann, D., Hamann, C. R., & Davis, M. J. (2023). Exploring the Potential and Limitations of Chat Generative Pre-Trained Transformer (ChatGPT) in Generating Board-Style Dermatology Questions: A Qualitative Analysis. Cureus. [CrossRef]

- Bolgova, O., Shypilova, I., Sankova, L., & Mavrych, V. (2023). How Well Did ChatGPT Perform in Answering Questions on Different Topics in Gross Anatomy? European Journal of Medical and Health Sciences, 5(6), 94. [CrossRef]

- Brin, D., Sorin, V., Konen, E., Nadkarni, G. N., Glicksberg, B. S., & Klang, E. (2023). How Large Language Models Perform on the United States Medical Licensing Examination: A Systematic Review [Review of How Large Language Models Perform on the United States Medical Licensing Examination: A Systematic Review]. medRxiv (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory). Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. [CrossRef]

- Çan, M. A., & Toraman, Ç. (2022). The effect of repetition- and scenario-based repetition strategies on anatomy course achievement, classroom engagement and online learning attitude. BMC Medical Education, 22(1). [CrossRef]

- Chan, A. Y.-C. C., Stapper, C. P., Bleys, R. L. A. W., Leeuwen, M. van, & Cate, O. ten. (2022). Are We Facing the End of Gross Anatomy Teaching as We Have Known It for Centuries? Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 1243. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Yi, H., You, M., Liu, W., Li, W., Li, H., Zhang, X., Guo, Y., Fan, L., Chen, G., Lao, Q., Fu, W., Li, K., & Li, J. (2025). Enhancing diagnostic capability with multi-agents’ conversational large language models. Npj Digital Medicine, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C. C., Bridges, S., & Tipoe, G. L. (2021). Why is Anatomy Difficult to Learn? The Implications for Undergraduate Medical Curricula. Anatomical Sciences Education, 14(6), 752. [CrossRef]

- Clusmann, J., Kolbinger, F. R., Muti, H. S., Carrero, Z. I., Eckardt, J.-N., Laleh, N. G., Löffler, C. M. L., Schwarzkopf, S.-C., Unger, M., Veldhuizen, G. P., Wagner, S. J., & Kather, J. N. (2023). The future landscape of large language models in medicine [Review of The future landscape of large language models in medicine]. Communications Medicine, 3(1). Nature Portfolio. [CrossRef]

- Farrokhi, A., Soleymaninejad, M., Ghorbanlou, M., Fallah, R., & Nejatbakhsh, R. (2017). Applied anatomy, today’s requirement for clinical medicine courses. Anatomy & Cell Biology, 50(3), 175. [CrossRef]

- Gilson, A., Safranek, C. W., Huang, T., Socrates, V., Chi, L., Taylor, R. A., & Chartash, D. (2023). How Does ChatGPT Perform on the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE)? The Implications of Large Language Models for Medical Education and Knowledge Assessment. JMIR Medical Education, 9. [CrossRef]

- Gotta, J., Qiao, H., Koch, V., Gruenewald, L. D., Geyer, T., Martin, S. S., Scholtz, J., Booz, C., Santos, D. P. dos, Mahmoudi, S., Eichler, K., Gruber--Rouh, T., Hammerstingl, R., Biciusca, T., Juergens, L. J., Höhne, E., Mader, C., Vogl, T. J., & Reschke, P. (2024). Large language models (LLMs) in radiology exams for medical students: Performance and consequences. RöFo—Fortschritte Auf Dem Gebiet Der Röntgenstrahlen Und Der Bildgebenden Verfahren. [CrossRef]

- Grévisse, C. (2024). LLM-based automatic short answer grading in undergraduate medical education. BMC Medical Education, 24(1). [CrossRef]

- Hariri, W. (2023). Analyzing the Performance of ChatGPT in Cardiology and Vascular Pathologies. Research Square (Research Square). [CrossRef]

- Ilgaz, H. B., & Çelik, Z. (2023). The Significance of Artificial Intelligence Platforms in Anatomy Education: An Experience With ChatGPT and Google Bard. Cureus. [CrossRef]

- Kasneci, E., Seßler, K., Küchemann, S., Bannert, M., Dementieva, D., Fischer, F., Gasser, U., Groh, G., Günnemann, S., Hüllermeier, E., Krusche, S., Kutyniok, G., Michaeli, T., Nerdel, C., Pfeffer, J., Poquet, O., Sailer, M., Schmidt, A., Seidel, T., … Kasneci, G. (2023). ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learning and Individual Differences, 103, 102274. [CrossRef]

- Knoedler, L., Knoedler, S., Hoch, C. C., Prantl, L., Frank, K., Soiderer, L., Cotofana, S., Dorafshar, A. H., Schenck, T. L., Vollbach, F. H., Sofo, G., & Alfertshofer, M. (2024). In-depth analysis of ChatGPT’s performance based on specific signaling words and phrases in the question stem of 2377 USMLE step 1 style questions. Scientific Reports, 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Krive, J., Isola, M., Chang, L., Patel, T., Anderson, M. C., & Sreedhar, R. (2023). Grounded in reality: artificial intelligence in medical education. JAMIA Open, 6(2). [CrossRef]

- Kung, T. H., Cheatham, M., Medenilla, A., Sillos, C., Leon, L. D., Elepaño, C., Madriaga, M., Aggabao, R., Diaz-Candido, G., Maningo, J., & Tseng, V. (2023). Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: Potential for AI-assisted medical education using large language models. PLOS Digital Health, 2(2). [CrossRef]

- Lai, U. H., Wu, K. S., Hsu, T.-Y., & Kan, J. K. C. (2023). Evaluating the performance of ChatGPT-4 on the United Kingdom Medical Licensing Assessment. Frontiers in Medicine, 10. [CrossRef]

- Meo, S. A., Al--Masri, A. A., Alotaibi, M., Meo, M. Z. S., & Meo, M. O. S. (2023). ChatGPT Knowledge Evaluation in Basic and Clinical Medical Sciences: Multiple Choice Question Examination-Based Performance. Healthcare, 11(14), 2046. [CrossRef]

- Mir, R., Mir, G. M., Raina, N. T., Mir, S., Mir, S. M., Miskeen, E., Alharthi, M. H., & Alamri, M. M. S. (2023). Application of Artificial Intelligence in Medical Education: Current Scenario and Future Perspectives. [Review of Application of Artificial Intelligence in Medical Education: Current Scenario and Future Perspectives.]. PubMed, 11(3), 133. National Institutes of Health. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V., Lurie, Y., & Mark, S. (2025). Accuracy of LLMs in medical education: evidence from a concordance test with medical teacher. BMC Medical Education, 25(1). [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S., Rajprasath, R., Durairaj, E., & Das, A. (2023). Artificial Intelligence Revolutionizing the Field of Medical Education. Cureus. [CrossRef]

- Papa, V., & Vaccarezza, M. (2013). Teaching Anatomy in the XXI Century: New Aspects and Pitfalls [Review of Teaching Anatomy in the XXI Century: New Aspects and Pitfalls]. The Scientific World JOURNAL, 2013(1). Hindawi Publishing Corporation. [CrossRef]

- Roos, J., Kasapovic, A., Jansen, T., & Kaczmarczyk, R. (2023). Artificial Intelligence in Medical Education: Comparative Analysis of ChatGPT, Bing, and Medical Students in Germany. JMIR Medical Education, 9. [CrossRef]

- Rosoł, M., Gąsior, J. S., Łaba, J., Korzeniewski, K., & Młyńczak, M. (2023). Evaluation of the performance of GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 on the Polish Medical Final Examination. Scientific Reports, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Saroha, S. (2025). Artificial Intelligence in Medical Education: Promise, Pitfalls, and Practical Pathways. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 1039. [CrossRef]

- Scherr, R., Halaseh, F. F., Spina, A., Andalib, S., & Rivera, R. (2023). ChatGPT Interactive Medical Simulations for Early Clinical Education: Case Study. JMIR Medical Education, 9. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P., Thapa, K., Dhakal, P., Upadhaya, M. D., Adhikari, S., & Khanal, S. R. (2023). Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: Unlocking the Potential of Large Language Models for AI-Assisted Medical Education. arXiv (Cornell University). [CrossRef]

- Singal, A., Goyal, S. Reliability and efficiency of ChatGPT 3.5 and 4.0 as a tool for scalenovertebral triangle anatomy education. Surg Radiol Anat 47, 24 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Ji, Z., Zhou, P., Dong, L., & Chen, Y. (2023). Clinical anatomy teaching: A promising strategy for anatomic education. Heliyon, 9(3). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).