Submitted:

08 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Aim

3. Methodology

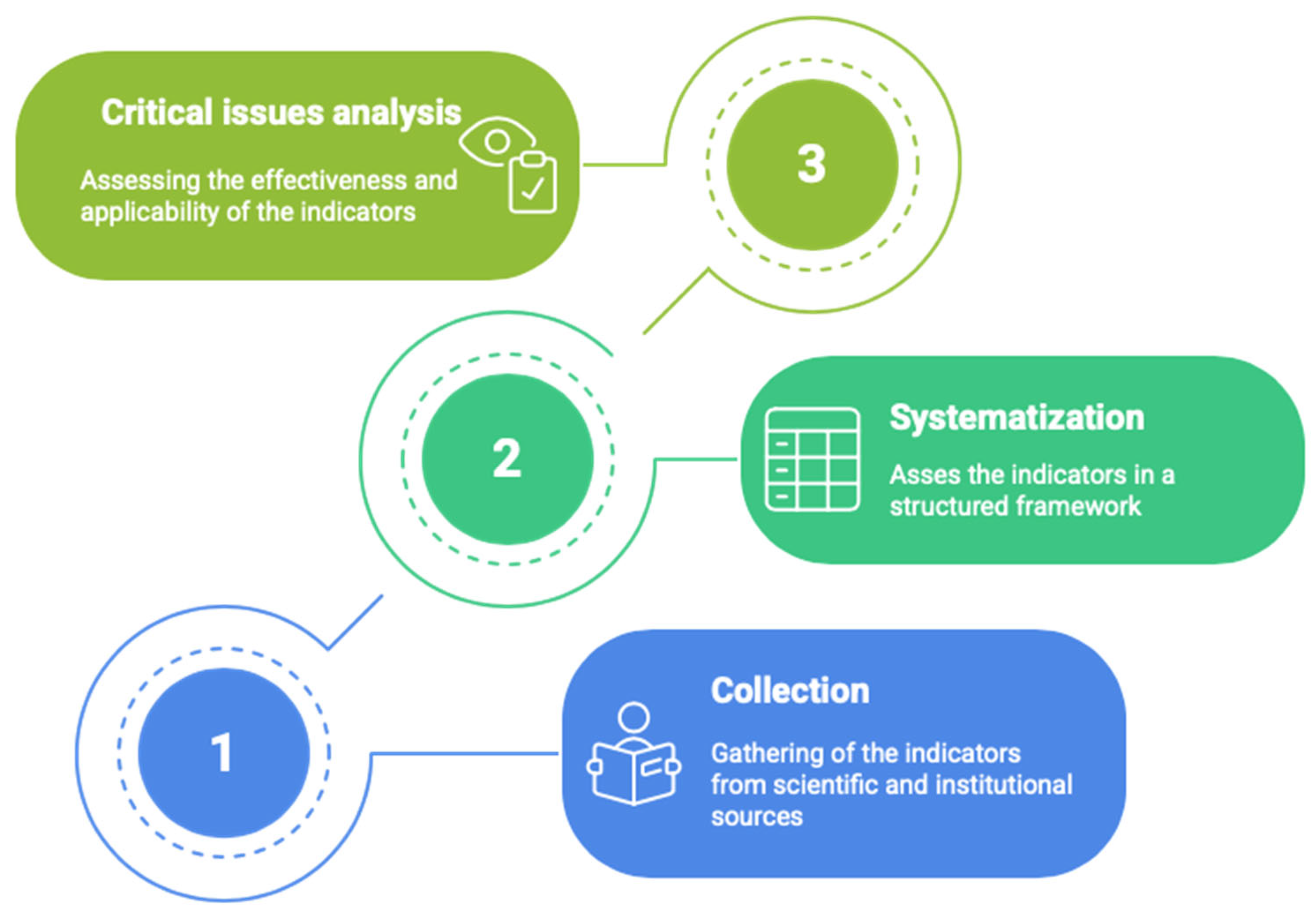

- Collection of the most commonly used urban sustainability indicators at the international level and identification of information sources.

- 2.

- Systematization of the identified indicators.

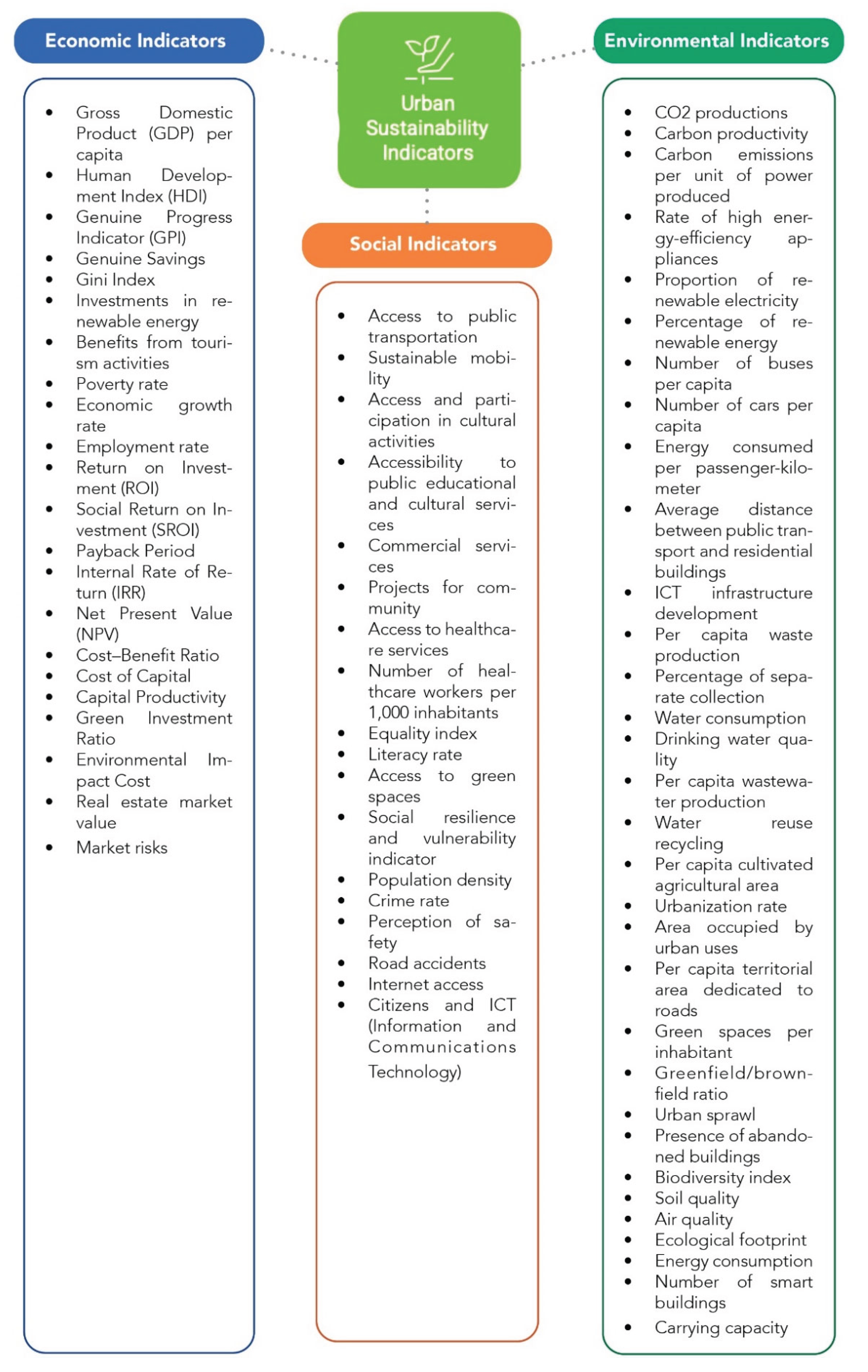

- category of each indicator based on classification into economic (22), environmental (31), and social (18) indicators;

- denomination of the indicator;

- brief description clarifying the indicator function and meaning;

- calculation formula to specify the elaboration methodology;

- utility of the indicator with reference to its practical applications in decision-making processes;

- standardizability level, i.e. the possibility of applying the indicator in local, national, and global contexts;

- reference source for each indicator to ensure scientific traceability;

- geographic scale of applicability, distinguishing indicators usable at urban, regional, national, or global levels.

- 3.

- Analysis of the critical issues and strengths points of the identified indicators.

- the ability of indicators to capture multidimensional dynamics;

- possible distortions arising from the impossibility of generalizing the applicability of the indicator as it is strongly connected to the local specificities of the context in which it has been developed;

- difficulties in data collection and standardization;

4. Discussion of the Results

4.1. Economic Indicators

4.2. Environmental Indicators

4.3. Social Indicators

5. Conclusions and Future Developments

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sachs JD. The age of sustainable development. New York: Columbia University Press; 2015.

- United Nations Habitat. Envisaging the future of cities. World Cities Report. 2022;:42.

- De Siqueira JH, Mtewa AG, Fabriz DC. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). In: Cuyckens H, Ferstman C, Tanaka A, editors. International Conflict and Security Law: A Research Handbook. The Hague: TMC Asser Press; 2022, pag. 761–777.

- Canton H. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development—OECD. In: Europa Directory of International Organizations 2021. London: Routledge; 2021, pag. 677–687.

- Morano P, Locurcio M, Tajani F, Di Liddo F. An innovative GIS-based territorial information tool for the evaluation of corporate properties. Sustainability. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Batty M. Inventing future cities. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press; 2021.

- Lytras MD, Şerban AC. E-government insights to smart cities research: European Union (EU) study and the role of regulations. IEEE Access. 2020;8:65313–65326. [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Peprah NT. World Development Report 2022: Finance for an equitable recovery. Washington (DC): World Bank Publications; 2022. [CrossRef]

- Aalbers HL. A territorial approach to the Sustainable Development Goals: Synthesis report. OECD Urban Policy Reviews. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2020.

- Meadows D. Limits to growth: The 30 year update. White River Junction (VT): Sustainability Institute; 2004.

- Moraliyska M. Measuring the justness of the European green transition. Coll Pap New Econ. 2023;1.1:30–41.

- Saltelli A, et al. Five ways to ensure that models serve society: a manifesto. Nature. 2020;582(7813):482–484. [CrossRef]

- Giampietro ME, Mayumi K. Multi-scale integrated analysis of societal and ecosystem metabolism (MuSIASEM). In: Farley J, editor. Dictionary of Ecological Economics. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing; 2023, pag. 362–363.

- JPI Urban Europe. Strategic research and innovation agenda 2.0. Vienna: JPI Urban Europe; 2019.

- Riedel H, et al. SDG-Indikatoren für Kommunen. Indikatoren zur Abbildung der Sustainable Development Goals der Vereinten Nationen in deutschen Kommunen. 2020.

- Hussain S, et al. Navigating the impact of climate change in India: a perspective on climate action (SDG13) and sustainable cities and communities (SDG11). Front Sustain Cities. 2024;5:1308684. [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz JE, Sen A, Fitoussi J. Report by the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress. Paris: Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress; 2009.

- United Nations General Assembly. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: UN; 2015.

- Johnstone I. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Yearb Int Environ Law. 2023;34.1:yvae026.

- Wade RH. The world development report 2022: Finance for an equitable recovery in the context of the international debt crisis. Dev Change. 2023;54.5:1354–1373. [CrossRef]

- Carra AE. Oltre il PIL, un’altra economia – Nuovi indicatori per una società del ben-essere. Roma: Ediesse; 2010.

- Baumann F. The next frontier—human development and the anthropocene: UNDP human development report 2020. Environ Sci Policy Sustain Dev. 2021;63.3:34–40. [CrossRef]

- United Nations General Assembly. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015.

- Talberth J, Cobb C, Slattery N. The Genuine Progress Indicator 2006. Oakland (CA): Redefining Progress; 2007.

- Hamilton C, Saddler H. The Genuine Progress Indicator. A new index of changes in well-being in Australia. 1997;14.

- Lange GM, Wodon Q, Carey K. The changing wealth of nations 2018: Building a sustainable future. Washington (DC): World Bank Publications; 2018.

- Mori K, Christodoulou A. Review of sustainability indices and indicators: Towards a new City Sustainability Index (CSI). Environ Impact Assess Rev. 2012;32.1:94–106. [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino S. Il coefficiente di Gini: le origini. Milano: Società Italiana di Economia Pubblica; 2020.

- Zenga M. Proposta per un indice di concentrazione basato sui rapporti fra quantili di popolazione e quantili di reddito. Giorn degli Econ Ann Econ. 1984;:301–326.

- Di Pasquale E, Tronchin C, Della Puppa F. Talenti e competenze nell’Europa del futuro. I dati del XIII rapporto annuale sull’economia dell’immigrazione. Quaderni di Ricerca sull’Artigianato. 2023;11.3:359–384.

- Cadum E, Costa G, Biggeri A, Martuzzi M. Deprivazione e mortalità: un indice di deprivazione per l’analisi delle disuguaglianze su base geografica. Epidemiol Prev. 1999;23.3:175–187.

- Scarpetta S, Di Noia C. Pensions at a glance 2023: OECD and G20 indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2023.

- Paniccia P, Silvestrelli P, Valeri M, editori. Economia e management delle attività turistiche e culturali. Destinazione, impresa, esperienza. Vol. 11. Torino: Giappichelli; 2010.

- United Nations. Statistical Division. International recommendations for tourism statistics 2008. No. 83. New York: UN; 2010.

- Navigating Global Divergences. World economic outlook. World Economic Outlook. 2023.

- Shakir Hanna SH, Cesaretti GP. Crescita economica e sostenibilità. Roma: Donzelli; 2019.

- Indriastuti M, Chariri A. The role of green investment and corporate social responsibility investment on sustainable performance. Cogent Bus Manag. 2021;8.1:1960120. [CrossRef]

- Bruno M. Applicazione di metodologie e indicatori di sostenibilità ambientale per la valutazione di nuovi sistemi di produzione di energia da fonti rinnovabili. 2023.

- Rizzello A. Green investing: Changing paradigms and future directions. Cham: Springer Nature; 2022.

- Li F, Cao X, Sheng P. Impact of pollution-related punitive measures on the adoption of cleaner production technology: Simulation based on an evolutionary game model. J Clean Prod. 2022;339:130703. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson G, Mourato S. Environmental cost-benefit analysis. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 2008;33.1:317–344.

- Hamidi E, et al. Computational study of heat transfer enhancement using porous foams with phase change materials: A comparative review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2023;176:113196. [CrossRef]

- Gallo A. A refresher on internal rate of return. Harv Bus Rev Digit Artic. 2016;2.

- Pratt S, Grabowski R. Cost of capital: Applications and examples. 2008.

- Then V, et al. Social return on investment analysis. In: Palgrave Studies in Impact Finance. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan; 2017.

- Wilson KE. Social impact investment: The impact imperative for sustainable development. 2019.

- Osborne MJ. A resolution to the NPV–IRR debate?. Q Rev Econ Finance. 2010;50.2:234–239.

- Damodaran A. Applied corporate finance. 3rd ed. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons; 2014.

- Arjunan K. A new method to estimate NPV and IRR from the capital amortization schedule and the advantages of the new method. Australas Account Bus Finance J. 2022;16.6. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson G. Cost benefit analysis and the environment: further developments and policy use. 2018.

- Qin X, et al. Exploring driving forces of green growth: Empirical analysis on China’s iron and steel industry. Sustainability. 2019;11.4:1122. [CrossRef]

- Schreyer P, Pilat D. Measuring productivity. OECD Econ Stud. 2001;33.2:127–170.

- Des Rosiers F, et al. Does an improved urban bus service affect house values?. Int J Sustain Transp. 2010;4.6:321–346.

- Di Liddo F, et al. A data analysis of the relationship between life quality indicators and the real estate market in Italian provincial capitals. Real Estate. 2025;2.2:4.

- Locurcio M, et al. An innovative GIS-based territorial information tool for the evaluation of corporate properties: An application to the Italian context. Sustainability. 2020;12.14:5836. [CrossRef]

- Orsi F. Misurazione del rischio di mercato. 2009;:1–104.

- Bărbulescu A. Modeling the greenhouse gases data series in Europe during 1990–2021. Toxics. 2023;11.9:726. [CrossRef]

- Dincer I, et al. Progress in clean energy. In: Novel Systems and Applications. Vol. 2. Cham: Springer; 2015.

- Çağlar M. Examining green growth conditions and achievements of the OECD countries: A descriptive analytical approach. Marmara Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Dergisi. 2024;:1–17.

- Khan A. Soil health and fertility: modern approaches to enhancing soil quality. Front Agric. 2024;1.2:283–324.

- Sovacool BK. Valuing the greenhouse gas emissions from nuclear power: A critical survey. Energy Policy. 2008;36.8:2950–2963. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk OA. Summary of the 2023 report of TCEP (Tracking Clean Energy Progress) by the International Energy Agency (IEA), and proposed process for computing a single aggregate rating. E3S Web Conf. 2025;601.

- Tol RSJ. The economic effects of climate change. J Econ. 2014.

- Ringel M, Knodt M. The governance of the European Energy Union: Efficiency, effectiveness and acceptance of the Winter Package 2016. Energy Policy. 2018;112:209–220. [CrossRef]

- Cosentino SL, et al. Le colture da biomassa per energia: il loro contributo alla sostenibilità agricola, energetica ed ambientale. Italus Hortus. 2014;21:29–58.

- Kammen DM. The rise of renewable energy. Sci Am. 2006;295.3:84–93. [CrossRef]

- Firdaus A, et al. Global renewable energy potential and installed capacity. Indones J Eng Sci. 2024;5.3:135–139. [CrossRef]

- Teresi G. Open Sustainability-Mobility Management: Un approccio integrato per l’efficienza e la sostenibilità dei sistemi di trasporto. Torino: Politecnico di Torino; 2024. Tesi di dottorato.

- Eiro L, et al. National Programme for Sustainable Growth in the Transport Sector 2021–2023. 2022.

- Laroche PCSJ, et al. Assessing the contribution of mobility in the European Union to rubber expansion. Ambio. 2022;51.3:770–783.

- Coraggioso G. La sostenibilità del trasporto intermodale ed il calcolo delle emissioni inquinanti. 2023.

- Rapson D, Muehlegger E. Global transportation decarbonization. J Econ Perspect. 2023;37.3:163–188.

- Burlando F. La sostenibilità ambientale nel settore Real Estate. Torino: Politecnico di Torino; 2022. Tesi di laurea.

- Citaristi I. United Nations Human Settlements Programme—UN-Habitat. In: Europa Directory of International Organizations 2022. London: Routledge; 2022, pag. 240–243.

- EA Perugia, Roma. La percezione della qualità della vita nelle città italiane: un confronto europeo. 2023.

- Masoura M, Malefaki S. Evolution of the Digital Economy and Society Index in the European Union: A Socioeconomic Perspective. TalTech J Eur Stud. 2023;13.2. [CrossRef]

- Ogbonna DN, Amangabara GT, Ekere TO. Urban solid waste generation in Port Harcourt metropolis and its implications for waste management. Manag Environ Qual Int J. 2007;18.1:71–88. [CrossRef]

- Marinello S, Lolli F, Gamberini R. Waste management and COVID-19: What does the scientific literature suggest?. Proc 10th Int Conf Informatics, Environ, Energy Appl. 2021.

- Magrini C, D’Addato F, Bonoli A. Municipal solid waste prevention: A review of market-based instruments in six European Union countries. Waste Manag Res. 2020;38.1_suppl:3–22. [CrossRef]

- Testa E. Strategie di comunicazione nella raccolta differenziata. 2011.

- Corona P. Indicatori ambientali e pianificazione territoriale. 1995.

- D’Angelis E, Grassi M. La nuova civiltà dell’acqua: il Piano Nazionale per la sicurezza idrica e idrogeologica e l’adattamento al cambiamento climatico. 2024;:1–398.

- Procházková M, et al. Industrial wastewater in the context of European Union water reuse legislation and goals. J Clean Prod. 2023;426:139037. [CrossRef]

- Brillanti C. Processi di urbanizzazione e implicazioni ambientali. Uno sguardo storico sulle peculiarità del caso Roma. In: Nuove storie. Milano: Mimesis; 2024, pag. 143–156.

- Ramm K, Smol M. Water reuse—analysis of the possibility of using reclaimed water depending on the quality class in the European countries. Sustainability. 2023;15.17:12781. [CrossRef]

- Viola J. Metodi di rilevamento delle perdite idriche lungo la rete di distribuzione del sistema acquedottistico italiano.

- Valmori I, Spadoni C. Agricoltura digitale: innovazioni e tecnologie per l'agricoltura sostenibile di oggi e domani. 2023;:1–271.

- Boerger V, et al. The state of the world’s land and water resources for food and agriculture – Systems at breaking point. Synthesis report 2021. FAO; 2021.

- Mwanza C. United Nations Human Settlements Programme: Recruitment, equitable geographical distribution and gender. 2023.

- Salvini MS. Evoluzione dell’urbanizzazione. Storia e sviluppo delle città nel mondo. Roma: Gruppo Albatros Il Filo; 2024.

- Munafò M. Consumo di suolo, dinamiche territoriali e servizi ecosistemici. Edizione 2022. Report SNPA 32/22. Roma: Sistema Nazionale per la Protezione dell’Ambiente; 2022.

- Ronchi S, Anghinelli S, Lodrini S. Riflessioni critiche sull'efficacia della VAS nel rispondere alle sfide della città contemporanea in Italia. Territorio. 2023;106.4:111–120. [CrossRef]

- Passalacqua M, Pozzo B. Diritto e rigenerazione dei brownfields. Amministrazione, obblighi civilistici, tutele. 2019.

- Battisti L, Dansero E, Di Gioia A. Riqualificazione delle periferie dal passato industriale: il ruolo delle nature-based solutions a Torino. Doc Geogr. 2023;2:279–303.

- Merola M. Misurare la sostenibilità urbana. Sistemi di indicatori a confronto e l’esperienza di ecosistema urbano. 2013.

- European Commission. OECD Regional Development Studies. Applying the Degree of Urbanisation: A Methodological Manual to Define Cities, Towns and Rural Areas for International Comparisons. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2021.

- Armondi S. Quali spazialità nelle politiche per la manifattura urbana? Scelte pubbliche e implicazioni geografiche. Geostoria Territ. 2021;:73–82.

- Bianchi A. La rigenerazione urbana per una nuova urbanistica. Riv Econ Mezzog. 2023;37.1–2:108–144.

- Campo P. Report Urban Nature 2019: Biodiversità urbana. Percorsi e proposte in campo. 2019.

- Brooks TM, et al. Global biodiversity conservation priorities. Science. 2006;313.5783:58–61.

- Erdogan HE, et al. Soil conservation and sustainable development goals (SDGs) achievement in Europe and Central Asia: Which role for the European soil partnership?. Int Soil Water Conserv Res. 2021;9.3:360–369. [CrossRef]

- Munafò M, et al. ISPRA land and soil monitoring, mapping, and assessment activities. In: Dazzi C, editor. Soil Science in Italy: 1861 to 2024. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2024, pag. 607–619.

- World Health Organization. WHO global air quality guidelines: particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide. Geneva: WHO; 2021.

- Turner MC, et al. Clean air in Europe for all! Taking stock of the proposed revision to the ambient air quality directives: a joint ERS, HEI and ISEE workshop report. Eur Respir J. 2023;62.4. [CrossRef]

- Global Footprint Network. Global footprint network, ecological footprint. 2023.

- Amrhein S, Reiser D. Ecological footprint. In: Idowu SO, Del Baldo M, Capaldi N, editors. Encyclopedia of Sustainable Management. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2023, pag. 1234–1240.

- Dechamps P. The IEA World Energy Outlook 2022 – A brief analysis and implications. Eur Energy Climate J. 2023;11.3:100–103. [CrossRef]

- Balluchi F. La valutazione delle performance socio-ambientali: indicatori e modelli interpretativi. Torino: Giappichelli Editore; 2013.

- Agrosì G, ed. La Smart City e la città comoda: una nuova realtà futurista “Smartiana”. Milano: Mimesis; 2022.

- US Green Building Council. LEED v4 for building design and construction. Washington (DC): USGBC Inc; 2014.

- Mustonen T, et al. The role of indigenous knowledge and local knowledge in understanding and adapting to climate change. In: IPCC Climate Change. 2022:2021–2030.

- Telišman-Košuta N, Ivandić N. Collaborative destination management based on carrying capacity assessment from resident and visitor perspectives: A case study of Crikvenica-Vinodol Riviera, Croatia. In: Petrosillo I, editor. Mediterranean Protected Areas in the Era of Overtourism: Challenges and Solutions. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021, pag. 175–192.

- Lucas K, Van Wee B, Maat K. A method to evaluate equitable accessibility: combining ethical theories and accessibility-based approaches. Transp. 2016;43.3:473–490. [CrossRef]

- Currie G. Quantifying spatial gaps in public transport supply based on social needs. J Transp Geogr. 2010;18.1:31–41. [CrossRef]

- Litman T. Evaluating transportation equity. Victoria (BC): Victoria Transport Policy Institute; 2017.

- Myrovali G, Morfoulaki M. Sustainable urban mobility. In: Urban Sustainability: A Game-Based Approach. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021, pag. 39–80.

- Cerquetti M, Sánchez-Mesa Martínez L, Vitale C. The management of cultural heritage and landscape in inner areas. 2019.

- Landmann T. Cultural security within the European Union in terms of selected conditions of the cultural economics. Sci J Military Univ Land Forces. 2021;53. [CrossRef]

- Pilipchuk NV, et al. Transformation of the higher education services market: Comparative analysis by OECD countries. In: Innovative Trends in International Business and Sustainable Management. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2022, pag. 321–332.

- Citaristi I. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization—UNESCO. In: Europa Directory of International Organizations 2022. London: Routledge; 2022, pag. 369–375.

- ISTAT. Le innovazioni nella rilevazione: la conduzione della raccolta dei dati nel censimento delle istituzioni pubbliche. Roma: Istituto Nazionale di Statistica; 2024.

- Turok I, Visagie J. Inclusive urban development in South Africa: what does it mean and how can it be measured?. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies; 2018.

- Mulgan G, Tucker S, Ali R, Sanders B. Social innovation: what it is, why it matters and how it can be accelerated. Oxford: Young Foundation; 2007.

- Servi M. Gestione sostenibile dei beni naturali Patrimonio dell'Umanità: il modello del Tourism Business Ecosystem applicato al Parco Nazionale dei Laghi di Plitvice. 2024.

- World Health Organization. Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators. Geneva: WHO Document Production Services; 2010.

- Vandenbroucke F. Working together to advance resilient health systems across the OECD. Lancet. 2024;403.10425:415–416. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030. Geneva: WHO; 2016.

- Liu JX, Goryakin Y, Maeda A, Bruckner T, Scheffler RM. Global health workforce labor market projections for 2030. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15.1:11.

- Di Bella E, Suter C. The main indicators of gender (in)equality. In: Marcuzzo MC, editor. Measuring Gender Equality. Milano: FrancoAngeli; 2023, pag. 61.

- UN Women. Progress on the sustainable development goals: the gender snapshot 2022. 2022.

- Antoninis M, et al. Global Education Monitoring Report 2023: Technology in education: a tool on whose terms?. Paris: UNESCO; 2023.

- Klapper L, Lusardi A, Van Oudheusden P. Financial literacy around the world. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2015.

- World Health Organization. Urban green spaces and health: a review of evidence. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2016.

- Kabisch N, Qureshi S, Haase D. Human–environment interactions in urban green spaces: a systematic review of contemporary issues and prospects for future research. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 2015;50:25–34. [CrossRef]

- Graziano P, Rizzi P. Resilienza e vulnerabilità nelle regioni europee. Scienze Regionali. 2020;19.1:91–118.

- Cutter SL, Boruff BJ, Shirley WL. Social vulnerability to environmental hazards. In: Moser SC, editor. Hazards, Vulnerability and Environmental Justice. London: Routledge; 2012, pag. 115–132. [CrossRef]

- Bigini M, Sacchi A. Crisi demografica, composizione della spesa pubblica e crescita economica: il caso italiano. Argomenti. 2024;28.

- Bongaarts J. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Family Planning 2020: Highlights. New York: United Nations Publications; 2020. [CrossRef]

- Hayes BE, Perander J, Smecko T, Trask J. Measuring perceptions of workplace safety: development and validation of the Work Safety Scale. J Saf Res. 1998;29.3:145–161. [CrossRef]

- McDaniels TL, Kamlet MS, Fischer GW. Risk perception and the value of safety. Risk Anal. 1992;12.4:495–503.

- Ivaldi E, Bonatti G, Soliani R. Composite index for quality of life in Italian cities: an application to URBES indicators. Rev Econ Finance. 2014;4:18–32.

- Carter DL. Law enforcement intelligence: a guide for state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies. Vol. 16. Washington (DC): US Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services; 2004.

- McElreath DH, et al. Introduction to law enforcement. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 2013.

- Nicholson-Crotty S, O'Toole LJ Jr. Public management and organizational performance: the case of law enforcement agencies. J Public Adm Res Theory. 2004;14.1:1–18. [CrossRef]

- Campagna D, Caperna G, Montalto V. Does culture make a better citizen? Exploring the relationship between cultural and civic participation in Italy. Soc Indic Res. 2020;149.2:657–686. [CrossRef]

- Balanskat A, Blamire R, Kefala S. The ICT impact report. Brussels: European Schoolnet; 2006.

- Rodela R. Decision support for inclusive spatial planning in the European geographical context. Plan Pract Res. 2025;40.2:406–420. [CrossRef]

- Pylypenko V, et al. Social inclusion in driving sustainable growth within United Territorial Communities. Grassroots J Nat Resour. 2024;7.3:420–457. [CrossRef]

- Guarini, M.R., Battisti, F. Social housing and redevelopment of building complexes on brownfield sites: The financial sustainability of residential projects for vulnerable social groups, Advanced Materials ResearchOpen source preview, 2014, 869-870, pp. 3–13. [CrossRef]

- Guarini, M.R., Battisti, F., Evaluation and management of land-development processes based on the public-private partnership, Advanced Materials ResearchOpen source preview, 2014, 869-870, pp. 154–161. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).