1. Introduction

The construction industry is characterized by labor-intensive operations and densely populated work environments, making it one of the most hazardous sectors globally [

1]. Despite significant efforts to raise awareness and implement safety management practices, construction-related fatalities remain alarmingly persistent. Researchers have increasingly adopted data-mining and artificial intelligence (AI)-based techniques to reduce fatalities in the construction industry. These include the integration of natural language processing with gated recurrent units and symbiotic organism search algorithms for safety assessment [

2], virtual-reality-based safety training for modular construction [

3], safety analysis in highway construction using GPT-3.5 [

4], and machine learning–based integrated safety management systems tailored to site-specific characteristics [

5].

However, effectiveness of advancements in training, monitoring technologies, and risk evaluation strategies remains limited without a holistic understanding of the diverse attributes of construction accidents and their interrelationships. This gap is amplified by the technical, organizational, and task-level complexities inherent in construction work [

6]. Another issue is, existing studies often focus on narrowly defined scenarios, for instance, formwork-related incidents [

7], scaffolding-related falls [

8], or highway construction [

9], providing only fragmented insights into accident causation. Each construction task or material introduces distinct risks, requiring safety strategies tailored to specific operational contexts.

Understanding how multiple factors interact, such as project type, activity performed, involved objects, and causal triggers like human error or environmental conditions is crucial for effective accident prevention. This underscores the need for careful investigation of past accidents to systematically map these interactions [

10], particularly under varying circumstances and to apply the findings toward mitigating accident risks, an area largely underexplored in the existing literature [

5]. In contrast to traditional predictive analytics, clustering and association-based techniques such as Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) and Association Rule Mining (ARM) are better suited for grouping and analyzing the complex, multifactorial interactions inherent in construction accident data [

11].

A significant number of recent studies have applied MCA and ARM independently to investigate and uncover complex interdependencies among accident-related attributes [

6,

11,

12,

13,

14]. However, the independent application of each approach presents distinct limitations. For example, MCA may struggle to explain data variance, particularly when dealing with a large number of categories [

15]. On the other hand, while ARM is widely recognized for its ability to reveal detailed associations among categorical variables, the high volume and diversity of attributes often result in an overwhelming number of association rules [

14,

16]. This makes its standalone application particularly challenging when analyzing the highly categorical and complex nature of construction accident data.

Therefore, the present study has two primary objectives. First, it addresses the lack of a framework for understanding on-site conditions that contribute to accidents, particularly the chain of mechanisms underlying construction accidents. To achieve this, the study uncovers critical associations among key accident components (such as accident type, project type, tasks performed, and objects involved) and links them to contributing factors (such as human error, procedural deficiencies, equipment malfunctions, task-specific hazards, and environmental conditions), by integrating two data mining techniques: MCA and ARM. This integrated approach enhances interpretability and analytical precision, while supporting the development of targeted intervention strategies aligned with daily construction activities. Second, the study addresses the present limitations of using MCA and ARM independently, by adopting an integrated analytical framework that applies MCA prior to ARM. In this sequential framework, MCA-based clustering is used first to reduce complexity and structure the dataset. With a more structured and focused dataset, ARM can then operate more efficiently and generate more meaningful, scenario-specific association rules.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to implement this dual data-mining approach within the context of construction safety. Through an accident breakdown structure–based analysis, this study potentially offers safety professionals a robust tool for understanding how and under what conditions accidents occur based on past incident analysis, thereby facilitating the formulation of more precise and effective safety strategies tailored to specific future construction scenarios.

2. Theoretical Background to ARM & MCA in Construction Accident

2.1. ARM Application to Construction-Accident Analysis

ARM is an unsupervised technique that identifies associations between attributes chronologically rather than deriving cause-and-effect relationships. The Apriori algorithm is commonly used for ARM to identify frequent item sets. The ARM evaluation metrics are support, confidence, and lift. Support indicates the co-occurrence frequency proportion of the antecedent (X) and consequent (Y) in the database [

17]:

Here, P(X∪Y) is the probability of X and Y co-occurring in a derived set of items and N is the total number of derived items.

Confidence is the proportion of items where Y occurs given X occurrence [

17]:

Lift is the comparison of the Y occurrence probability given X with its actual occurrence probability [

17]:

ARM-generated rules are meaningful only when they are significant for the entire dataset. To ensure meaningful rules, the least significant rules are filtered using minimum support and confidence values. Additionally, lift < 1 indicates a negative association, whereas lift > 1 suggests that the presence of X induces Y [

14].

Applications of ARM in accident-related studies have typically focused on linking accident types with various accident attributes,

Table 1 summarizes the relevant studies and their focus areas. In general, most existing studies emphasize isolated factors or simple pairwise associations, failing to capture the dynamic, multifaceted nature of construction environments. Key contextual elements, such as the temporal and spatial dimensions of accidents, on-site working conditions, and the sequence of events leading to incidents, are frequently overlooked [

5,

18].

For example, Liao and Perng [

19] used ARM to identify injury-related attributes based on construction accident reports in Taiwan from 1999 to 2004. Cheng et al. [

20] applied ARM to analyze cause-and-effect relationships in 1,347 construction accidents in Taiwan between 2000 and 2007. Shin et al. [

21] used attributes such as contract amount, number of daily workers, worker tenure, age, and occupation, along with accident content, type, day, time, consequences, and project progress rate to analyze their interactions in relation to each accident. Similar approaches were adopted by Guo et al. [

17] and Ayhan et al. [

16], who examined the interplay between accident-related factors in an effort to develop attribute-based accident prevention systems. More recently, Kim et al. [

14] analyzed project characteristics, working objects, activities, and accident types using big data, while Shao et al. [

11] focused on associations among area, accident type, outcome, and time in collapse-related accidents in China.

While these studies provide valuable insights, they primarily focus on either specific or high-level attributes such as project characteristics, task categories, workers’ profiles or temporal information and often with the aim of predicting accident types. Although these factors are important for understanding criteria that contribute to accidents, this outcome-oriented approach makes it difficult to examine how specific objects (e.g., heavy equipment or temporary facilities) or activities (e.g., loading, painting, cutting) directly influence the occurrence of incidents. Many of the studies provide only a partial consideration of the influencing attributes, and more critically, they often overlook the underlying causal triggers that elevate the risk of accidents in relation to other key factors. For instance, was the accident caused by inadequate supervision, lack of safety awareness, equipment malfunction, or adverse weather conditions? Although Yoon et al. [

6] categorized accident causes using the 4-M framework, material, method, machine, and man, the study did not explore how these causal triggers interact with other critical accident attributes, such as accident type, activity, or object involved.

As a result, the influence of these causes on other accident-related variables remains unclear, and their interdependencies are still vague. This lack of clarity highlights the need for further investigative analysis of past accident data using ARM. Such analysis would allow a more thorough examination of how immediate causal triggers interact with other critical accident factors, thereby helping to fill the identified gap in the literature.

2.2. MCA Application to Accident Analysis

MCA statistically visualizes relationships between two or more categorical attributes by extracting the maximum information inherent in the data. MCA dimensions are interpreted based on coordinate positions; a two-dimensional depiction is usually sufficient to explain most of the variance [

22]. Eigenvalues measure the quantity of categorical information accounted for by each dimension; a higher eigenvalue indicates larger total variance among the variables in that dimension. The largest possible eigenvalue is 1.

In MCA, data are structured in a contingency table, with rows representing observations and columns representing attributes. A binary matrix encodes the attribute categories, and row/column indices are calculated by dividing the contingency-table frequencies by the marginal frequencies. Singular value decomposition (SVD) is then used to decompose the matrix of standardized residuals into matrices containing information on row and column indices. Consider a tabular dataset of categorical variables, denoted as X, where X consists of I observations across K categorical attributes. If the total number of distinct categories across all attributes is J, then:

where J

k is the number of categories for attribute k [

23]. To include all categories in the dataset, an additional data matrix with dimensions I × J is created, where each attribute is represented by multiple columns to display its possible categorical values. For example, for an attribute with two categories, the presence or absence of a category in an observation is indicated by 1 or 0, respectively.

If the sum of all entries in X is N, the probability matrix Z is computed as

If r and c indicate the vectors of the row and column totals of Z, respectively, the diagonals of c and r are D

r and D

c, respectively, and the MCA factor score can be obtained from the SVD of the following matrix:

Here, ∆ is the singular matrix of the diagonal values and ∧ is the eigenvalue matrix, such that ∧ = ∆^2. The observation (rows and columns, respectively) coordinates are given as [

23]:

These equations provide the coordinates for plotting the rows and columns in a lower-dimensional space (typically two-dimensional), which reveals the relationships between the categories [

23]. The inter-point distance in this plot indicates the level of association: smaller distances suggest a stronger association, whereas larger distances indicate a weaker or no association.

MCA is widely used in safety research, particularly in road traffic and collision studies. For example, Das and Sun [

24] applied MCA to analyze fatal run-off-road crashes in Louisiana using accident data from 2004 to 2011, while Jalayer and Zhou [

25] used it to identify patterns in motorcycle- and motorcyclist-related attributes influencing at-fault motorcycle-involved crashes based on a 2009–2013 dataset from Alabama. MCA has also been employed in the analysis of crash pattern in wrong-way driving accidents [

15], in fatal accident analyses involving wrong-way highway driving [

26], crash characteristics across different temporal levels [

27], and ship-to-ship collisions [

28].

In the construction sector, Kamardeen [

12] applied MCA to a dataset of 1,048 construction accident records collected over 13 years (2002–2014) to investigate fatality patterns. The study examined variables such as worker age, sex, occupation, injury type and location, and mechanism of injury, identifying seven distinct accident clusters, including fatal falls, equipment-related deaths, and noise- and substance-related incidents. However, a major limitation of this study was its omission of specific causal trigger attributes, such as procedural failures, human errors, or environmental factors, which are crucial for understanding why such accidents occur.

While researchers across various disciplines have demonstrated the utility of MCA in uncovering latent patterns within complex categorical datasets, its application in construction accident research remains notably limited. Existing studies have shown that MCA is effective in reducing dimensionality and identifying co-occurring patterns that are often hidden in raw data. However, because MCA does not assume any specific data distribution, and given the inherently multifactorial and categorical nature of construction accident data, where tasks, objects, and environmental conditions frequently interact, this lack of assumption may interfere with the accurate interpretation of results if MCA is applied in isolation. Therefore, MCA is better positioned as a preliminary step for grouping similar accident scenarios, where it can organize complex data into structured clusters and enhance the effectiveness of subsequent analytical methods such as ARM.

2.3. Integration of MCA and ARM for Construction Risk Assessment

Few researchers have actually combined MCA and ARM in safety analysis. Amiri et al. [

29] applied multiple data-mining techniques to Iranian construction-industry accident datasets from 2007–2011. Using MCA, they first determined the related accident-attribute associations such as worker’s age, marital status, time or injured part etc. Additionally, they applied decision tree ensembles to analyze the accident-influencing factors and examined the relationships between the accident criteria and consequences using ARM. Recently, Rahman et al. [

13] applied both MCA and ARM to investigate animal–vehicle crashes: first, MCA generated crash clusters, and then ARM found the frequent attribute associations in severe crash groups.

Table 1 summarizes previous MCA and ARM applications in construction-safety accident studies.

MCA and ARM both identify patterns in datasets but differ in purpose and approach: MCA focuses on visualizing relationships and reducing dimensionality among categorical attributes, while ARM extracts explicit rules to reveal frequent patterns and potential cause-and-effect links. One issue with MCA is, it can struggle with high-dimensional datasets when it comes to adequately explaining variance [

15]. When the explained variance is low, unrelated attribute categories may appear in close proximity within the MCA plot, depending on the factor scores calculated, as outlined in Equations (4) and (5), which might lead to inaccurate clustering and can hinder the pattern analysis in construction accident. As a result, relying solely on MCA for detailed analysis may compromise the accuracy of findings, particularly in the context of construction accident scenarios. In contrast, ARM identifies patterns based on the attribute co-occurrence frequency (Equations (1)–(3)). Previous construction-safety research agrees that ARM can generate an overwhelming number of rules, necessitating pruning techniques or expert knowledge to distinguish significant from insignificant rules [

14,

16]. Additionally, for improperly set metrics, ARM may produce too few rules, particularly for imbalanced data, as highlighted by Cheng et al. [

20].

Given the distinct limitations of MCA and ARM when applied independently, a combined approach offers a promising solution that leverages the strengths of both techniques while mitigating their respective weaknesses. Applying MCA as a preliminary clustering step can serve as an effective pre-pruning technique for ARM. This sequential approach facilitates the extraction of more concise and relevant association rules by narrowing the analytical focus to context-specific accident clusters. It enables a deeper examination of how risk factors collectively influence safety outcomes across various stages of construction by mapping accident causes within specific operational contexts. These refined insights can support the formulation of more precise, data-informed safety measures and adaptive intervention frameworks tailored to the evolving conditions of construction projects.

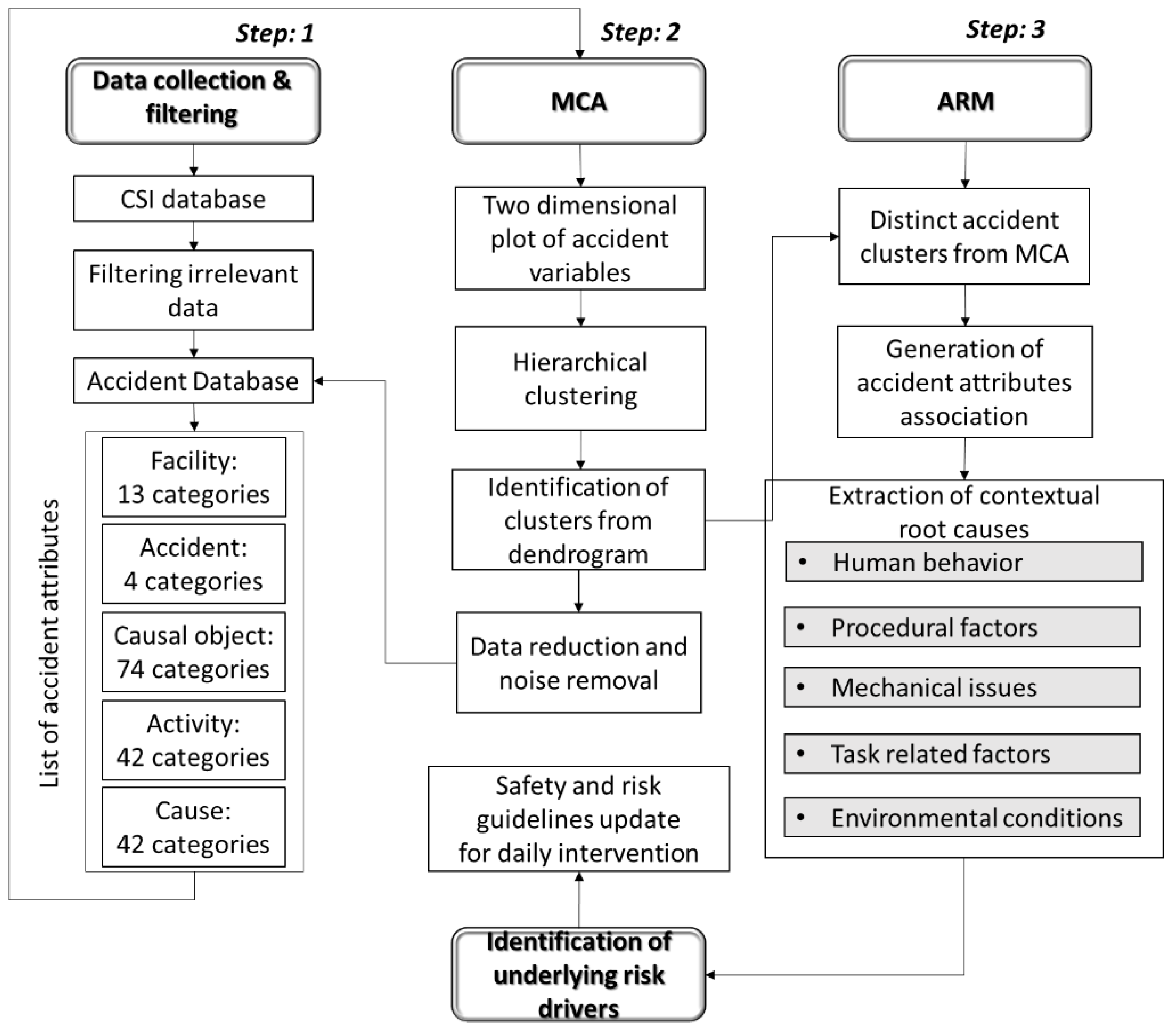

3. Methodology

The research methodology comprised four steps: data collection and filtering (step 1), MCA (step 2), ARM (step 3) and improved safety strategy implementation guideline through identification of underlying risk drivers (step 4). The Korea Authority of Land and Infrastructure Safety (KALIS) has implemented the Construction Safety Management Integrated Information (CSI) system, which continuously collects and updates data on construction accident cases. The CSI system provides standardized information on hazard factors, categorized by occupation, and has been widely utilized by Korean researchers for accident analysis and investigation [

5,

6,

14]. This study also adopts the CSI database for analysis of construction accident causes.

In Step 1, data collection and preprocessing were conducted. The CSI dataset comprises a comprehensive record of construction-site events, including personal illnesses and incidents ambiguously categorized as “others” or “not classified.” To ensure the accuracy and reliability of subsequent analyses, these non-informative categories were systematically excluded using custom Python scripting, which removed all rows with the corresponding entries from the database. Additionally, rows containing missing data were eliminated to maintain consistency and integrity across the dataset. The original CSI dataset contained approximately 14,286 entries from 2019 to 2023, and after removing the irrelevant and missing entries, the dataset was reduced to 12,484 valid samples.

The triggers of construction-site accidents often involve multiple causative factors and must be examined across a broad range of attributes [

11].

Figure 1 illustrates the five categorical attributes and the number of categories for each attribute considered in the present study. The attribute selection process was conducted with five considerations: following the ‘where’ (facility), ‘what’ (accident), where (activity), ‘how’ (causal object), and ‘why’ (causal object) sequence for risk factor extraction in the accident breakdown structure. “Facility” refers to the construction-project type, such as a bridge, buildings, or water supply system, etc. “Accident” indicates common construction-site accident types in Korea (e.g., falls, hits, stuck, and cuts) [

6,

14]. “Activity” refers to specific tasks (e.g., dismantling, installation, maintenance, or moving, etc.). “Causal object” indicates the category of accident-associated objects (e.g., excavators, dump trucks, or cranes etc.) as defined in the dataset. “Cause” contains expert-identified reasons for accident triggers, with 42 categories including worker unawareness, poor dismantling procedures, improper equipment operation, and incorrect personal protective equipment (PPE) usage, etc., which are systematically recorded in the CSI database [

6]. Each attribute and the respective categories are included in Appendix I.

In Step 2, MCA is applied to the filtered CSI database. Applying MCA to these selected five attributes generates multiple specific scenarios, such as falls, hits, stuck, and cut accidents, by clustering relevant facility, causal object, causal triggers and activity types with the corresponding accident types in close proximity. While MCA offers a useful visual representation of data, to support the identification of associations between attribute categories and to determine the optimal number of clusters, previous studies have used hierarchical clustering as a complementary technique [

30]. In this study, hierarchical clustering was applied to the MCA coordinate data points to determine the association. Dendrograms were then used to visually determine the optimal number of clusters based on these associations. At the end of step 2, each of the identified clusters were extracted for further analysis with ARM.

In Step 3, ARM is used to generate meaningful association rules that identify specific causal risk factors within each of the clusters identified in Step 2. From the CSI data, the 42 categories of accident causes are grouped into five major classes: (a) human behavior (e.g., worker negligence or inadequate use of PPE), (b) procedural factors (e.g., poor installation methods or improper work sequencing), (c) mechanical issues (e.g., equipment malfunctions or operational defects), (d) task-related factors (e.g., unsafe movement or work posture), and (e) environmental conditions (e.g., weather conditions or unsafe surrounding structures). ARM uncovers detailed associations between these cause classes and specific activities or objects at the construction-project level for different accident types.

In Step 4, the findings are critically analyzed to identify specific stages within the daily activity schedule that require advance inspection, thereby enhancing the efficiency and focus of safety planning. Finally, the process for developing targeted safety guidelines and effective safety management strategies is demonstrated through an example case study.

4. Accident-Pattern and Causation Analysis

4.1. MCA-Based Cluster Generation

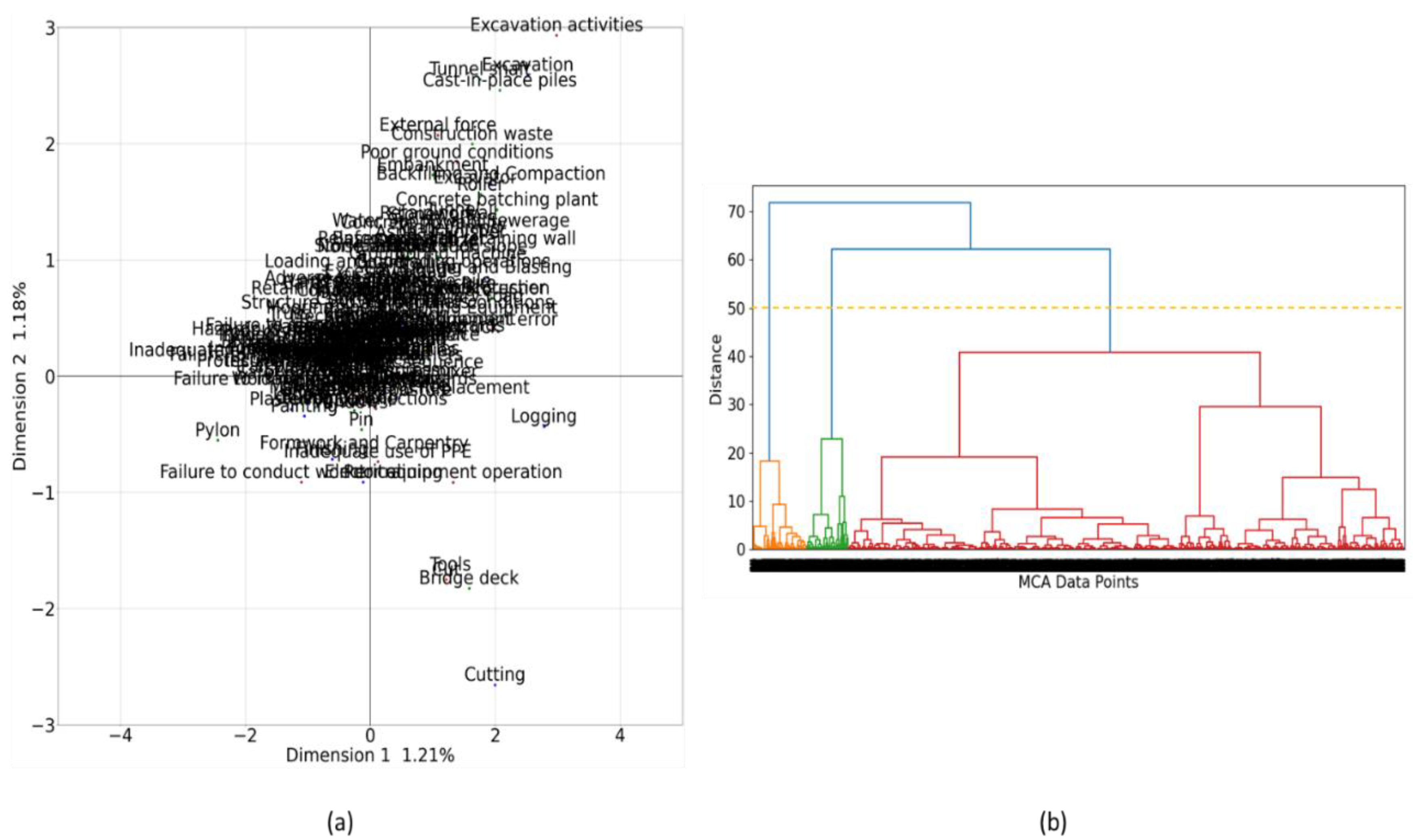

The five MCA attributes included facility, activity, causal object, accident type, and cause. The results were plotted in two dimensions to visualize the relationships among these accident attributes (

Figure 2). MCA reduces dimensionality by projecting the original data onto new dimensions (axes) that capture the maximum variance within the dataset.

Figure 2 (a), Dimensions 1 and 2 (horizontal and vertical axes, respectively) represent the first and second principal components. The eigenvalues (as described in Equation (6)) quantify the amount of variance explained by each dimension; thus, Dimensions 1 and 2 are the principal axes that capture the greatest variance. Points that appear close to each other in the plot are more similar or related within the context of the analyzed dimensions.

Due to the large number of categories, the original MCA plot appears visually congested, hindering clear interpretation of associations, a known limitation of MCA as previously discussed. To overcome this issue and to separate closely positioned points that may carry redundant information, this study employs hierarchical clustering based on dendrogram analysis to systematically determine the optimal number of clusters and extract the corresponding data points.

Table 2 summarizes the eigenvalues for each dimension. A higher eigenvalue indicates a greater proportion of total variance explained by that dimension. The relatively low eigenvalues for the first two dimensions suggest a high degree of heterogeneity among the attributes, with each contributing unique and distinct information [

31]. This heterogeneity reflects the inherently random and complex nature of construction-site accidents. As shown in

Table 2, the first two dimensions together account for approximately 2.5% of the total variance. This outcome of lower values of variance supports the initial assumption that MCA alone is insufficient to capture the complete structure of construction accident data. Consequently, it should be paired with a complementary analytical method, such as ARM, to more effectively uncover the underlying associations among accident attributes.

Next, hierarchical clustering was applied to the coordinates generated from MCA to uncover meaningful groupings within the data. This process employed Ward’s linkage method, which minimizes total within-cluster variance at each merging step [

32]. As an unsupervised learning technique, hierarchical clustering produces a dendrogram, a tree-like structure that visualizes how individual data points are progressively grouped into larger clusters.

Figure 2(b) presents the dendrogram constructed from the MCA-derived data points. The top of the dendrogram represents the full dataset, with all data points eventually merged into a single cluster. In contrast, the densely populated lower section displays the original MCA data points before clustering. Horizontal cuts at different vertical distances yield varying levels of clustering granularity; in this study, a cut was made at approximately 40 (dashed orange line), resulting in three distinct clusters containing 720, 549, and 7,366 entries, respectively. This process effectively filters out noise within the data, reducing the dataset from 12,484 to 8,635 for more focused analysis.

The clusters identified through hierarchical clustering, then were utilized to generate association rules independently. This approach narrows the rule generation scope to more homogeneous groups, thereby enhancing the specificity, relevance, and interpretability of the resulting association rules.

4.2. ARM-based Causal Factor Analysis

ARM also considers the same five attributes: accident, structure, activity, object, and actual-cause type. The ARM parameters (support, confidence, and lift) for rule generation typically depend on the dataset. Setting support and confidence thresholds too low can lead to an overwhelming number of rules, whereas excessively high thresholds may produce too few, limiting their analytical value. To strike a balance between rule relevance and interpretability, minimum thresholds of 0.01 for support, 60% for confidence, and ≥1.0 for lift were applied consistently across all clusters based on established metrics previous literature [

14,

16]. The following subsections present the analysis results for each cluster, with section headings including the support, confidence, and lift values associated with each cluster.

4.2.1. Cluster 1

Table 3 presents association rules derived through Association Rule Mining (ARM) for Cluster 1. In ARM, an if-then relationship is established between sets of accident-related factors, where the antecedents predict the likelihood of the consequents. Each rule’s lift value > 1 indicates a meaningful association, while high confidence values (>80%) signify reliability.

For instance, Rule 1 reveals that during installation activities, if workers show negligent behavior, there is a high probability (92% confidence, lift = 1.46) that a cut-type accident will occur, involving tool-type objects in building construction projects. Similar scenarios appear in Rules 2 and 3, where formwork and carpentry or setup activities, coupled with worker negligence, are also highly associated with cut-type injuries and the use of tools. Conversely, Rules 4 and 5 highlight how cutting activities performed in building-type facilities can lead to cut injuries when construction tools are used under unsafe conditions, such as poor equipment operation or reckless actions.

The network graph in

Figure S1 effectively illustrates the key associations within Cluster 1. The central node, Accident_Cut, is connected to a variety of activity types, causes, facilities, and object types that frequently co-occur in cut-related incidents. This visual mapping highlights how Cluster 1 specifically groups factor combinations that are strongly associated with cut-type accidents, offering valuable insights for identifying and mitigating such scenarios on construction sites.

The rules in Cluster 1 reveal two dominant themes: (1) human behavior-related causes, particularly negligence and recklessness, and (2) mechanical or equipment-related issues, such as poor tool handling or unsafe operational procedures. These patterns reinforce known industry concerns, but the data-driven specificity provided by the model adds operational clarity. For instance, traditional safety protocols might flag “cutting” or “tool use” as generic hazards; in contrast, the model pinpoints when these become critical, e.g., during formwork tasks under negligent attitude, allowing managers to prioritize inspections.

4.2.2. Cluster 2

Table 4 presents the association rules derived through ARM for Cluster 1, which primarily includes hit and stuck type incidents. Only five rules were generated, all of which involve excavation-related activities. For stuck-type accidents, the likelihood of occurrence is high, about 87.5% confidence, for excavation activities, especially when the worker makes a judgment error while working near an excavation slope (object type). This rule also shows a strong association with a lift value of 7.51. Inadequate removal of wastes is identified as a key contributing factor that can trigger hit-type accidents in both excavation and drilling and blasting activities, with 100% confidence (Rules 4 and 5). However, these rules do not involve any specific object type. Except in Rules 2 and 3, none of the rules include facility type, indicating that project type does not hold significant influence in these specific scenarios, or has less relevance compared to the object or cause categories. In Rule 2, both water Supply and sewerage and buildings facilities were found to be associated with hit-type accidents, and the likelihood of occurrence is exactly 100% when the worker exhibits neglectful behavior. In Rule 3, the complexity of excavation activities significantly influences hit-type accidents with 73% confidence; however, both of these rules also lack specific object-type information.

Overall, this cluster reveals more fragmented associations rather than comprehensive links across all five considered attributes.

Figure S2 presents the network graph visualizing the associations between the attribute categories, where Activity_Excavation appears as the central connecting node. In summary, the rules generated in Cluster 2 demonstrate how task complexity, judgment errors, and site management deficiencies contribute to specific accident types in excavation operations. These insights can be integrated into pre-task risk assessments (e.g., job hazard analyses). For example, supervisors should conduct real-time evaluations of terrain and assign more experienced personnel to high-risk slope zones. Additionally, given the limited influence of facility type, safety planning should prioritize activity and cause factors over project classification.

4.2.3. Cluster 3

Cluster 3 reveals multiple associations under diverse construction scenarios, reflecting a broad spectrum of activity-accident relationships. For example, during installation activities, both hit and fall type accidents are likely to occur in building-type projects when workers exhibit neglectful behavior. Among these, hit-type accidents show a stronger association, with a confidence level of 89% (Rule 7), whereas fall-type accidents are also linked to the presence of formwork as an object (Rule 6).

In the case of dismantling activities, hit-type accidents can occur under two distinct conditions: (1) due to poor dismantling procedures in building projects, even without a specific object type (confidence: 54%, lift: 7.14, Rule 1), or (2) due to worker negligence when handling formwork (Object) (confidence: 51%, lift: 1.49, Rule 5). While the confidence values are moderate, they still represent meaningful risks and should be considered in risk assessments. Fall type accidents from installation activities due to poor installation method also indicates a moderately associated risk (confidence: 50%, lift: 2.21). Transportation activities are associated with both hit and stuck type accidents, each showing over 80% confidence within building-type projects, mostly stemming from worker negligence and without any specific object type involved (Rules 2 and 8). Meanwhile, fall-type accidents are more likely to result from worker negligence during finishing activities (confidence: 75%, lift: 2.06, Rule 3) than during moving activities (confidence: 64%, lift: 1.51, Rule 4), again in the context of building-type projects.

This cluster is notably more diverse than the others, likely due to its inclusion of the largest number of entries, which may contribute to the variation in patterns.

Figure S3 presents a network graph visualizing the associations among all accident-related factors in Cluster 3. One of the most prominent patterns across this cluster is the recurring presence of worker negligence, which is linked to multiple accident types across various activities. In contrast, object type plays a relatively minor role in this cluster, as only two rules include a specific object (formwork).

Overall, Cluster 3 highlights the complex and multifactorial nature of accident causation in construction. The data reveals that across varied tasks, from installation to transport, human behavior, especially negligence, consistently emerges as a critical risk factor. As such, safety strategies should focus not only on task-specific protocols but also on reinforcing a strong safety culture that addresses behavioral risks at all levels of project execution. From an operational standpoint, these findings support the use of the MCA+ARM framework not only to detect high-risk activity–cause–accident patterns that may not be evident in traditional risk assessments, but also to encourage behavior-based safety interventions, particularly for routine tasks such as finishing, moving, or dismantling.

Table 5.

Association between accident factors in Cluster 3.

Table 5.

Association between accident factors in Cluster 3.

| Rule No |

Antecedents |

Consequents |

Support |

Confidence |

Lift |

| 1 |

Facility_Buildings, Cause_Poor dismantling procedure |

Accident_Hit, Activity_Dismantling |

0.011 |

0.54 |

7.14 |

| 2 |

Accident_Hit, Activity_Transportation, Cause_Worker’s negligence |

Facility_Buildings |

0.011 |

0.84 |

1.03 |

| 3 |

Activity_Finishing, Cause_Worker’s negligence |

Facility_Buildings, Accident_Fall |

0.014 |

0.75 |

2.06 |

| 4 |

Facility_Buildings, Activity_Moving, Cause_Worker’s negligence |

Accident_Fall |

0.02 |

0.64 |

1.51 |

| 5 |

Object_Formwork, Activity_Dismantling, Cause_Worker’s negligence |

Accident_Hit |

0.011 |

0.51 |

1.49 |

| 6 |

Object_Formwork, Activity_Installation, Cause_Worker’s negligence, Facility_Buildings |

Accident_Fall |

0.011 |

0.51 |

1.19 |

| 7 |

Accident_Hit, Activity_Installation, Cause_Worker’s negligence |

Facility_Buildings |

0.025 |

0.89 |

1.08 |

| 8 |

Accident_Stuck, Activity_Transportation, Cause_Worker’s negligence |

Facility_Buildings |

0.01 |

0.875 |

1.06 |

| 9 |

Accident_Fall, Cause_Poor installation method |

Activity_Installation |

0.021 |

0.50 |

2.21 |

4.3. Cluster-Based Patterns and Risk Interpretations

A critical review of the derived association rules suggests that rule informativeness is highly dependent on contextual segmentation. In Clusters 1 and 2, ARM produced high-confidence, high-lift rules despite fewer rule generations, indicating strong intra-cluster homogeneity. In contrast, Cluster 3, though rule-rich, yielded a wider range of confidence values and weaker inter-variable consistency, likely due to greater input diversity. This reinforces that clustering granularity directly influences the signal-to-noise ratio in ARM outputs, thereby affecting the reliability of actionable insights.

Fall, hit, and cut-type accidents were more prevalent than stuck-type incidents, consistent with prior CSI-data based studies [

6,

14]. Similar patterns have been reported in other regional studies, where fall and hit accidents outnumber other types [

6,

33], suggesting a broader trend in construction accident occurrences. Among all causal factors, human behavior, including negligence, reckless actions, and judgment errors, appeared most frequently, highlighting persistent safety lapses across activity types. This underlines the need for enhanced supervision, particularly aligned with scheduled activities, to create a more responsive and dynamic safety management framework.

Notably, object type was often absent in high-confidence rules despite its inclusion, indicating that object-specific hazard patterns may be less stable across contexts. This challenges the emphasis on object-focused risk assessments, such as formwork, scaffolding [

7,

8], and construction tools or equipment [

34], commonly seen in previous research. Similarly, facility type appeared inconsistently, implying limited predictive value unless combined with task and behavior-related variables. These findings underscore the importance of interaction effects, which are often overlooked in univariate or bivariate models.

Overall, the findings align with and extend previous research. Prior studies have linked cut-type accidents to tasks involving tools and small machinery [

35], which this study further associates with building projects, human behavior, and mechanical issues. Hit and stuck-type accidents during excavation, as noted by [

36], and the role of inadequate waste removal in hit-type incidents [

33] are also supported. Unlike earlier work, the present study connects these activities to specific root causes, such as human behavior and task-related factors. improving practical relevance. Similarly, the association of fall accidents with dismantling, moving, and installation tasks involving formwork and scaffolding [

37,

38], and hit accidents caused by materials during transportation and setup [

14,

33], are reaffirmed. However, the proposed approach goes further by linking such patterns to explicit causal triggers, enabling daily risk prioritization, something not feasible without this level of causal mapping.

Given the dynamic nature of construction projects, these attributes interactions should be systematically recorded. A national integrated system could support real-time risk alerts by allowing managers to input daily activity details, such as facility type, task, and object, into a database that maps these to known accident-cause associations. Additionally, a risk assessment indicator could be incorporated, categorizing risks as moderate (50%–65%), high (70%–85%), or very high (>85%) based on the confidence levels associated with each rule to assist the project or risk manager in decision making or in developing necessary strategies.

5. Results and Discussion

This section presents a hypothetical case study demonstrating how insights from the MCA+ARM framework can be applied to real-world construction safety scenarios, highlighting its potential for enhanced risk management and accident prevention:

A safety manager (X) at a large construction company is overseeing a wastewater treatment plant construction project. Key tasks for the day include, 1: Heavy material moving near formwork structures (facility type: Water Supply & Sewerage); 2: Excavation work for pipeline laying; 3: Tool-intensive setup of scaffolding around an overhead tank. Each task is entered into the company’s integrated safety-risk management system, which leverages insights from the MCA+ARM framework. The input consists of the activity keywords (“moving”, “excavation” and “setup”) and associated objects (“formwork”, “pipe” and “tool”) and all under the common facility type “water supply and sewerage”.

The system cross-references each input against a pre-mapped database of MCA cluster-based association rules derived from historical construction accident data. When keywords are entered, the system first retrieves all association rules related to the input activity. Next, it filters the rules by the relevant object or facility type to ensure contextual relevance. Finally, the system outputs the associated risk factors and provides an overall risk assessment, along with a qualitative risk indication level (e.g.,

Moderate, High, Very High), which is determined based on the confidence level (

Table 6).

Guided by the output, X implements a proactive risk mitigation plan. Each intervention targets the risk factors identified for each task, with the intensity of the intervention informed by the rule’s confidence and lift values (i.e., higher-risk scenarios prompt more stringent controls). Key measures include:

Targeted Supervision for Movement/Fall Prevention: For the task involving heavy material movement near formwork (moderate risk; 64% confidence for fall accidents), the safety manager (X) deploys a dedicated on-site supervisor to monitor worker activities throughout the shift. While the confidence and lift values are comparatively lower than other scenarios, they still highlight worker behavior, particularly negligence, as a critical contributing factor. The supervisor ensures strict adherence to fall prevention protocols, including the use of designated walkways, controlled pace of movement, and maintenance of three-point contact during vertical transitions.

Engineering Controls and PPE for Excavation Activities: For the excavation and pipeline installation task (high risk; 73% confidence for hit-type accidents), X enforces a dual-layered safety strategy comprising engineering and administrative controls. Temporary barricades are installed around open trenches to physically isolate workers from mobile equipment and to prevent inadvertent access to high-risk zones. The high lift value (2.38) indicates a strong contextual relationship between excavation activities and impact-related incidents, thus warranting immediate and stringent risk control measures. In parallel, a second supervisory team is tasked with conducting scheduled safety audits and ensuring the continuous integrity of barriers and signage.

Enhanced Safety Briefing and PPE Enforcement for Tool-Based Setup Work: For the scaffolding setup task involving hand tools (very high risk; 100% confidence for cut-type accidents), X organizes a task-specific pre-work safety briefing. The session emphasizes precision in tool handling, safe posture, and adherence to best practices during assembly operations. All personnel are required to undergo a PPE verification process, including the mandatory use of cut-resistant gloves, face shields, and protective eyewear. No worker is permitted to begin operations without full compliance. The high-confidence rule justifies a zero-tolerance policy and full enforcement of safety protocols.

Throughout the day, X systematically tracks the implementation and compliance of each intervention using a structured checklist aligned with the identified MCA–ARM risk profiles. Based on this data-driven strategy, X estimates a projected 20–30% reduction in incident rates within the targeted hazard categories, compared to previous projects lacking such analytical support. Although hypothetical, this case study demonstrates the practical applicability and transformative potential of integrating pattern-driven insights into proactive, task-level construction safety management.

6. Conclusions

The present study addresses a critical gap in the construction safety analytics literature, namely, the tendency to aggregate diverse accident scenarios in ways that obscure meaningful causation patterns. Without identifying immediate and actionable causal factors, it becomes difficult to conduct effective risk assessments or to develop proactive safety strategies, especially when the goal is to manage risks both across construction stages and in day-to-day operations. Additionally, this study responds to the limitations of prior research employing cluster-based pattern analysis techniques, such as ARM, which often generate an overwhelming number of rules with limited interpretability. By integrating MCA with ARM, this study reduces data dimensionality, thereby enabling the extraction of more focused, interpretable, and actionable safety insights.

The proposed approach accounts for multiple dimensions of construction accidents, including accident types and contextual attributes, factors that have often been underexplored in previous studies. It follows a systematic logic based on the sequence of “where” (facility), “what” (accident), “when/where” (activity), “how” (causal object), and “why” (cause), forming an accident breakdown structure that aligns with a prototype risk assessment framework for maintaining safe construction sites. A hypothetical case study was presented to demonstrate how these insights can be integrated into daily risk assessments, tailored to scheduled construction activities.

Despite its strengths, the framework has limitations. First, while ARM effectively captures direct co-occurrences between causes and outcomes, it does not infer temporal or causal directionality. For example, although “worker’s negligence” frequently appears across various accident types and activities, it remains unclear whether it serves as a primary cause or a compounding factor influenced by other latent variables, such as task complexity or environmental conditions. Additionally, even high-confidence association rules should be interpreted with caution, especially in imbalanced datasets where certain accident types (e.g., falls or hits) are disproportionately represented, as observed in previous studies. Second, the dataset used originates from Korea, which introduces potential regional or cultural biases in the identified patterns. The prevalence of certain accident types (e.g., falls, hits) and the dominance of behavioral causes may reflect localized work practices, regulatory contexts, or reporting standards. Third, while the framework reduces dimensional complexity, imbalanced data distributions can still lead to high-confidence rules for overrepresented categories. This highlights the need for data balancing techniques (e.g., SMOTE, under-sampling) and rule prioritization strategies in future implementations. Fourth, the explained variance in MCA is very low due to the large number of categories, which, although a common issue in MCA, can still be problematic. Finally, the hypothetical case study, while illustrative, does not provide empirical evidence for real-world effectiveness. Future work should focus on pilot testing the framework in actual construction projects to validate usability and impact.

In conclusion, the MCA–ARM integrated framework presents a promising method for uncovering latent, context-specific patterns in construction accident data. However, its broader applicability should be further investigated at a global level to support practical, cross-regional safety assessments. Moving forward, integrating these insights into adaptive safety management systems will be essential for enabling proactive, data-informed risk mitigation in construction environments.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Association of cut-type accident attributes from Cluster 1; Figure S2: Association of hit and stuck-type accident attributes from Cluster 2; Figure S3: Association of hit and fall-type accident attributes from Cluster 3.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.C and J.H.C.; methodology, A.M.C and J.H.C; software, A.M.C.; validation, A.M.C and J.H.C.; formal analysis, A.M.C. ; investigation, A.M.C.; resources, J.H.C., S.I.P; data curation, A.M.C.; writing—original draft preparation A.M.C. and J.H.C.; writing—review and editing, A.M.C. and J.H.C.; visualization, A.M.C.; supervision, S.I.P and J.H.C.; project administration, J.H.C.; funding acquisition, S.I.P and J.H.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Korea Agency for Infrastructure Technology Advancement (KAIA), funded by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport (RS-2020-KA156208).

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data, models, or code that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used ChatGPT for the purposes of grammatical correction.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Suh, S. A qualitative study understanding unsafe behaviors of workers in construction sites. Korean J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023, 24.6, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.Y.; Kusoemo, D.; Gosno, R.A. Text mining-based construction site accident classification using hybrid supervised machine learning. Autom. Constr. 2020, 118, 103265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Chae, J.; and Kang, Y. Job training and safety education for modular construction using virtual reality. Korean J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023, 24.5, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smetana, M.; Salles de Salles, L.; Sukharev, I.; Khazanovich, L. Highway construction safety analysis using large language models. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14.4, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Chang, T.; Chi, S. Developing an integrated construction safety management system for accident prevention. J. Manag. Eng. 2024, 40.6, 04024051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.G.; Ahn, C.R.; Yum, S.G.; Oh, T.K. Establishment of safety management measures for major construction workers through the association rule mining analysis of the data on construction accidents in Korea. Buildings 2024, 14.4, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.R.; Shin, Y.S.; Shin, J.K. Checklist development for prevention of safety accidents in formwork in small and medium-sized construction sites. J. Korea Inst. Build. Constr. 2017, 17.6, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, E.; Yurdusev, M.A.; Yildizel, S.A.; Calis, G. Investigation of scaffolding accident in a construction site: A case study analysis. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 120, 105108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, R.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, N.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Yang, H. Modified accident causation model for highway construction accidents (ACM-HC). Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 28, 2592–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairami-Khankandi, S.; Bolbot, V.; BahooToroody, A.; Goerlandt, F. A systems-theoretic approach using association rule mining and predictive Bayesian trend analysis to identify patterns in maritime accident causes. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 258, 110911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Guo, S.; Dong, Y.; Niu, H.; Zhang, P. Cause analysis of construction collapse accidents using association rule mining. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 30.9, 4120–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamardeen, I. Preventing Workplace Incidents in Construction: Data Mining and Analytics Applications. Routledge, Abingdon, Oxon, 2020.

- Rahman, M.A.; Das, S.; Codjoe, J.; Mitran, E.; Sun, X.; Abedi, K.; Hossain, M.M. Applying data mining methods to explore animal-vehicle crashes. Transp. Res. Rec. 2023, 2677.11, 665–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.N.; Kim, T.H.; Lee, M.J. Analysis of building construction jobsite accident scenarios based on big data association analysis. Buildings 2023, 13.8, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Avelar, R.; Dixon, K.; Sun, X. Investigation on the wrong way driving crash patterns using multiple correspondence analysis. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2018, 111, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayhan, B.U.; Doğan, N.B.; Tokdemir, O.B. An association rule mining model for the assessment of the correlations between the attributes of severe accidents. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2020, 26.4, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zhang, P.; Ding, L. Time-statistical laws of workers’ unsafe behavior in the construction industry: A case study. Physica A 2019, 515, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C., Chen, R., Jiang, S., Zhou, Y., Ding, L., Skibniewski, M.J., and Lin, X. 2019. “Human dynamics in near-miss accidents resulting from unsafe behavior of construction workers.” Physica A, 530, 121495.

- Liao, C.W.; Perng, Y.H. Data mining for occupational injuries in the Taiwan construction industry. Safety Sci. 2008, 46.7, 1091–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.W.; Lin, C.C.; Leu, S.S. Use of association rules to explore cause–effect relationships in occupational accidents in the Taiwan construction industry. Safety Sci. 2010, 48(4), 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.P., Park, Y.J., Seo, J., and Lee, D.E. “Association rules mined from construction accident data.” KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22, 1027–1039.

- Greenacre, M.; Blasius, J. Multiple Correspondence Analysis and Related Methods. Chapman and Hall/CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 2006.

- Salkind, N.J. Encyclopedia of measurement and statistics. SAGE publications, London, UK. 2006 Oct 13.

- Das, S.; Sun, X. Association knowledge for fatal run-off-road crashes by multiple correspondence analysis. IATSS Res. 2016, 39.2, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalayer, M.; Zhou, H. A multiple correspondence analysis of at--fault motorcycle--involved crashes in Alabama. J. Adv. Transp. 2016, 50(8), 2089–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhou, H.; Chang, Q.; Jalayer, M. Multiple correspondence analysis of wrong-way driving fatal crashes on freeways. Transp. Res. Rec. 2021, 2675(10), 1312–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, T.P.; Wu, Y.W.; Chen, A.Y. Temporal stability of associations between crash characteristics: A multiple correspondence analysis. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2022, 168, 106590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugurlu, H.; Cicek, I. Analysis and assessment of ship collision accidents using fault tree and multiple correspondence analysis. Ocean Eng. 2022, 245, 110514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, M.; Ardeshir, A.; Fazel Zarandi, M.H.; Soltanaghaei, E. Pattern extraction for high-risk accidents in the construction industry: A data-mining approach. Int. J. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2016, 23.3, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibenda, M.; Wedagama, D.M.P.; Dissanayake, D. Drivers’ attitudes to road safety in the South East Asian cities of Jakarta and Hanoi: Socio-economic and demographic characterisation by multiple correspondence analysis. Safety Sci. 2022, 155, 105869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Sun, X. Factor association with multiple correspondence analysis in vehicle–pedestrian crashes. Transp. Res. Rec. 2015, 2519.1, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, F. Introduction to HPC with MPI for Data Science. Springer. Switzerland. 2016.

- Esmaeili, B.; Hallowell, M.R.; Rajagopalan, B. Attribute-based safety risk assessment. I: Analysis at the fundamental level. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2015, 141.8, 04015021. [CrossRef]

- Williams, O.S.; Hamid, R.A.; Misnan, M.S. Accident causal factors on building construction sites: A review. Int. J. Built Environ. Sustain. 2018, 5.1, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winge, S.; Albrechtsen, E. Accident types and barrier failures in the construction industry. Safety Sci. 2018, 105, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingard, H.; Cooke, T.; Gharaie, E. A case study analysis of fatal incidents involving excavators in the Australian construction industry. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2013, 20(5), 488–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomakov, V.I.; Tomakov, M.V.; Pahomova, E.G.; Semicheva, N.E.; Bredihina, N.V. A study on the causes and consequences of accidents with cranes for lifting and moving loads in industrial plants and construction sites of the Russian Federation. J. Appl. Eng. Sci. 2018, 16.1.504, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.M.; Won, J.H.; Jeong, H.J.; Shin, S.H. Identifying critical factors and trends leading to fatal accidents in small-scale construction sites in Korea. Buildings 2023, 13, 2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).