Background

The complexities associated with preterm birth are often traumatic for parents, both physically and emotionally [

1]. Parents experience separation from their infants in the neonatal care environment, while strangers care for their preterm babies Feelings of being poorly prepared, being overwhelmed by both in-hospital and post-discharge care-taking responsibilities, and unique personal needs throughout an infant’s stay in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) may influence parents’ ability to cope with their responsibilities These factors may have an impact on the development of the parent-infant relationship as well as the caregiver’s experience of their parenting role [

2].

Educational programmes delivered to parents of preterm infants during their NICU stay have been shown to improve both parental and neonatal outcomes [

3]. These benefits include increased parental confidence, enhanced knowledge of infant care, greater parental satisfaction, and improved mental health such as reduced stress and anxiety [

3,

4]. These programmes have the potential to alleviate parental stress and contribute to discharge preparation [

4,

5]. Springer et al. [

4] confirmed previously identified outcomes, including enhanced caretaking behaviour, positive parent-infant interaction, and stronger attachment. Additionally, Melnyk et al. [

6] demonstrated a reduction in length of stay when parents participated in NICU-based educational programmes.

Drawing on previous studies, educational topics that have been included in preterm parenting educational programmes covered infant health, information about what to expect in the NICU, preparing parents to see their infant for the first time, understanding infant behaviour, practical aspects of infant care (including skin-to-skin care and infant massage), infant feeding with a high emphasis on breastfeeding, and discharge planning In addition, Brett et al. [

5] identified potentially helpful education interventions, such as teaching parents to use behavioural assessment scales to interpret their preterm infant’s behaviour, parent support forums, and information and communication sharing.

There is an evident diversity of focus in studies on parent education programmes [

3] with most evaluating the effectiveness of education programmes. There has also been some evaluation of educational programmes with different styles of delivery, including direct instruction, written instruction (which may include brochures and reflective journaling), and even technology-based or simulation formats [

4]. However, the detailed curriculum or key components to be included in such educational programmes are less frequently presented in published articles.

In a review of the current literature, Lubbe et al. [

7] identified the key components of parenting education programmes for parents of preterm infants while in the NICU. The main topics included in published educational programmes were understanding the NICU environment, infant health, infant behaviour, infant care, infant feeding, and discharge preparation. It was clear that, for most programmes described, logistical considerations informed the delivery framework, and this informed delivery method(s), characteristics, and presentation formats of the educational intervention, and the key people involved in the educational programme delivery. The geographical representation of reports where parental educational programmes were implemented included high-, upper-middle-, and lower-middle-income countries, with one report from a low-income country. Only a few of the articles included qualitative research [

7].

Although literature covered parent educational programmes and their content designed for parents from all income levels, it did not specifically explore the South African context and parents’ perspectives of their own educational needs while their child was in the NICU. The literature therefore presented a good general framework of the ‘what’ to be included in a parenting programme, but was less clear about the ‘when’, ‘by whom’, and ‘how’ questions. It remains important to explore the specific context of any such programme, in order to determine the most suitable structure, considering both instructional approaches (such as delivery method and instructional formats) and training logistics (frequency and time of educational sessions, and facilitator type).

The aim of this study was to explore parental needs and perceptions regarding a parenting education intervention provided to them while in the NICU, with a focus on programme content, structure, and mode of delivery.

Methods

Aim and Design

This study followed a qualitative, exploratory, descriptive design comprising three semi-structured focus group discussions (FGDs) conducted between February and April 2023, with parents of preterm infants admitted to the neonatal ward.

Setting

This study was conducted in the Dr Kenneth Kaunda district in the North West province of South Africa, in a public, tertiary, referral hospital. The hospital has 8 NICU beds, 9 high-care neonatal beds, and 28 low-care neonatal beds, with an average of 66 neonatal admissions per month [

8]. The term neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in this study included critical care, high care, growing prem, and kangaroo-mother care units, as these are all included in a neonatal ward context in South Africa.

The patient profile of this hospital includes mothers from lower-income settings without medical insurance who are often referred to the facility from other geographical districts. Immediately after delivery, mothers are admitted to the postnatal ward, and mothers of less stable or more immature infants are discharged and may visit their babies daily (or less often) from home. Parents often live some distance from the hospital and incur costs when visiting their infants. Lodging facilities are available only when babies are mature enough to be cared for in the kangaroo-mother unit.

Participants

Inclusion criteria comprised parents of infants, singletons or multiples, born in the hospital with a gestational age below 37 weeks, and expected to stay in the NICU for at least 7 days. Mothers aged over 18 years were enrolled during their infants’ hospital stay as soon as possible after admission to the NICU. Parents needed to be able to understand and speak either English or one of the regional languages (Setswana or Afrikaans). The most frequently spoken home language in the province is Setswana (63.4%), followed by Afrikaans (9%). Parents with a history of drug addiction, psychosis, or other severe mental illnesses were excluded. Parents whose infants had severe congenital abnormalities or who had undergone major surgery were also excluded, due to the very specific educational needs surrounding these conditions.

Parents meeting specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were purposefully selected [

9], as these mothers were able to provide in-depth information on the topic of parental educational needs while the infant is admitted to the NICU. The mothers were allocated to three face-to-face focus groups consisting of eight to nine participants each [

10], totalling 25 mothers.

Recruitment of Participants

The study received ethics approval from the Health Research Ethics Committee of the University of Cape Town (UCT- 647/2021), followed by North West provincial and hospital management approvals. No data collection procedures were initiated prior to obtaining written informed consent from all participants. This study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki [

11] and the 2024 South African Ethics in Health Research Guidelines [

12].

Mothers who met the inclusion criteria were recruited by dedicated nursing staff working in the neonatal ward. Recruitment nurses explained the study to the mothers and invited them to attend a focus group in a quiet and private venue on the hospital premises at a convenient time that would not interfere with feeding or other contact times with their infants.

Parents who wished to consider their participation in the study or consult with family members were encouraged to decide within 24 hours, since the information to be obtained was time sensitive and mothers’ input was required while they were living the experience of having their baby admitted to the NICU. The first FGD was conducted after the first 10 mothers were enrolled, and the process was repeated for the second and third focus groups.

At the venue, the study was again explained by the researcher (lead author), who then left the room and allowed the independent person to conduct the informed consent process, once again explaining that mothers could opt out without any prejudice to themselves. Some mothers did, indeed, choose to withdraw at this stage (that is, prior to consent). Permission was also obtained to audio-record the discussions to ensure that no data were missed.

Data Collection

FGDs provided the opportunity to interview a homogenous group of mothers – all with preterm infants still admitted to the NICU – on a specific topic: their perceived educational needs [

13]. The strength of focus group interviews in this study was the ability to capitalise on the group process – with interaction and participants sharing experiences as well as commenting on each other’s experiences, producing more detailed information and a deeper perspective [

14] of their own educational needs while in the NICU.

A focus group discussion question guide was developed for the purpose of the study (Supplementary Material S1). The main question which guided the FGDs was: What are/were your needs regarding parenting education while your baby is/was admitted to the NICU? In addition, probing questions guided parents to share specific content to be included in a parenting education programme, share their ideas on the mode of delivery and structure of the delivered programme, reflect on how healthcare professionals influenced their parenting, and share any creative solutions they had on the question of NICU-based parenting education.

The FGDs lasted between 36 and 58 minutes (an average of 46 minutes) and were conducted by an experienced interviewer with the support of a research intern who took field notes. Saturation was reached within each FGD as well as between the three groups [

15].

Data Analysis

The audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim by a trained transcriber and checked for accuracy. Setswana transcripts or phrases were translated into English by a language practitioner to allow English-speaking researchers to analyse the data. To ensure anonymity, a code was allocated to each focus group [

16] and all identifiers were removed. Thematic analysis of the FGDs and their field notes was performed by the researcher and an independent coder according to Tesch’s approach [

17]. This process was followed by reading and re-reading all the transcripts and field notes to obtain a sense of the whole whereafter one focus group was selected and the salient categories were identified. Similar topics were identified and clustered together, while appropriate and descriptive wordings were identified to assign the topics to appropriate sections. The next step was to group related topics and categorise them, whereafter final categories were agreed upon, which were then organised and coded. This structured data was preliminarily analysed and re-coded where necessary.

All anonymised copies of the transcripts were sent to the co-coder, who replicated the process to ensure that no data were lost. The coder and co-coder then compared the analysed datasets to identify, discuss, and reach a consensus on the discrepancies of the final codes, categories, and themes [

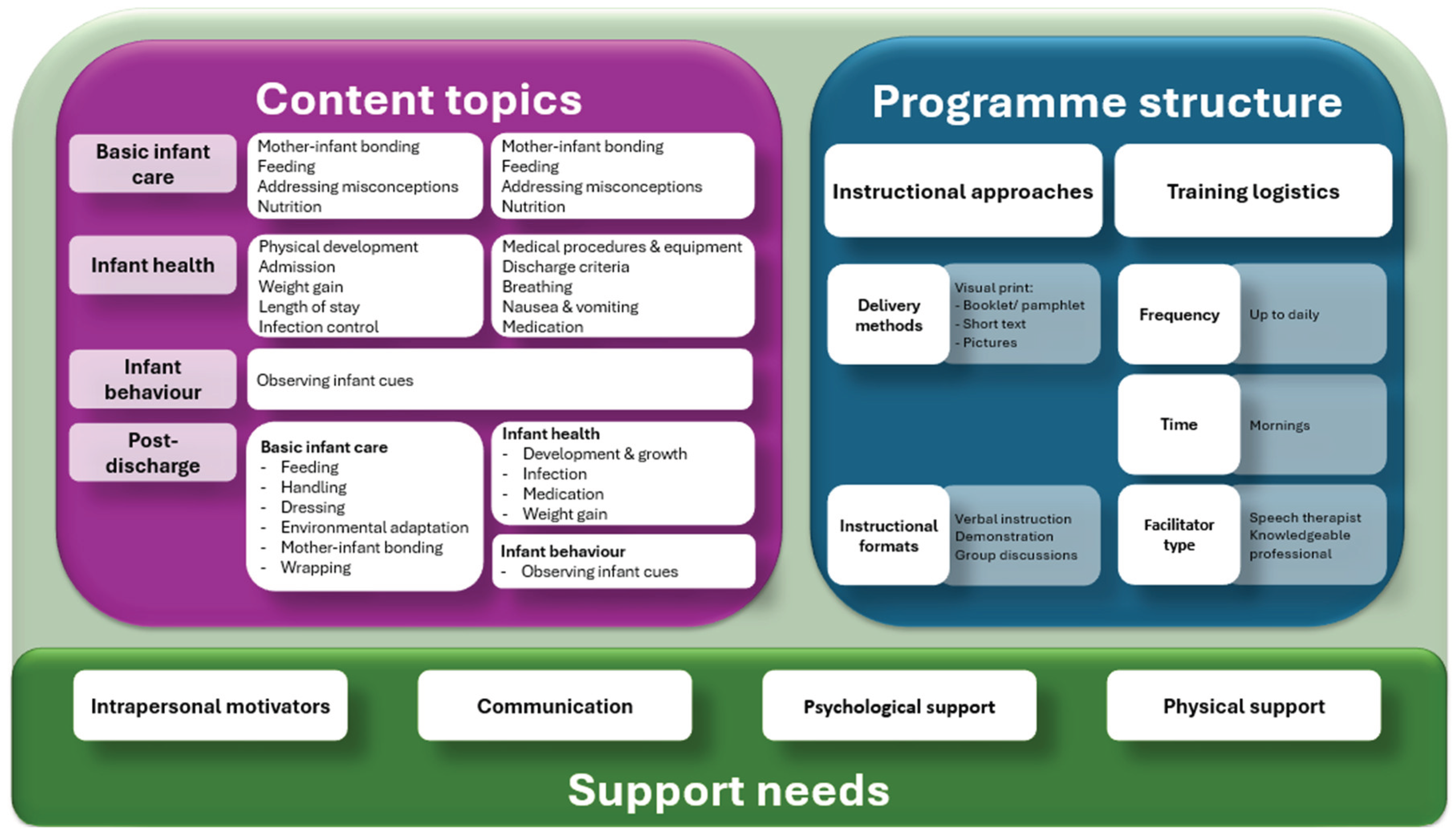

16]. This process and results can be seen in

Figure 1: Parent educational programme delivery framework.

Results

Participating mothers were over 18 years of age and had experienced either a singleton or multiple birth, with a reported infant birth weight ranging between 800 and 1900 grams. Most mothers were fluent in English, with a small percentage preferring to speak Setswana but understanding English. Biographical data was requested from the participants in a self-reported format as part of their informed consent. However, most participants were unsure about information such as exact gestational age, birth weight, and APGAR scores. Since ethical approval did not allow access to patient files, the researchers relied on information that the mothers were able to share during the focus group interviews.

The findings are presented in three main areas: a) content topics, b) education programme structure, and c) support needs, aligning well with the questions posed, namely: 1) ‘share specific content’, 2) ‘share ideas on structure’, and 3) ‘mode of delivery’ (see

Figure 1: Parent educational programme delivery framework). Participants were also asked to reflect on how healthcare professionals influenced their parenting and to provide creative ideas regarding parenting education.

The results are now presented under the three categories: Content topics, Programme structure, and Support needs.

Category A: Content Topics

Content topics included information needs about basic infant care, infant health and behaviours, and post-discharge related information needs.

Basic infant care needs voiced by parents focused on information pertaining to feeding (n=42), including information on breastmilk expression, bottle-feeding versus breastfeeding, and milk storage. As participants stated, ‘Because they also told us, before you feed you start to check if the tube is on the right position’ (F1) and, ‘Yes, we want more information about feeding and bathing’ (F3). Basic infant care further included handling (n=14) as voiced by F1: ‘So, as parents we are told to not touch our babies because we bring infection’. One mother’s response, that highlighted the importance of their innate need for mothering and closeness, was, ‘We take time to come to the babies and bond with them’ (F1).

Infant health and Infant behaviour focussed mostly on concerns regarding infant development (n=20) as articulated by one participant, ‘I need to know that he is developing… like lungs, and others, after how long.’ (F1). The next most prominent focus was on medical procedures or equipment (n=12), ‘Mentally wise, it won’t affect them because, most of them, you find out that they’re putting drips on their heads?’ (F1). Infection was mentioned (n=9), ‘Like it is said they are prone to infection’ (F1), followed by weight gain (n=7) as an indicator of good development and as a discharge criterion, ‘When he reaches that KG [kilogram] where he can go home’ (F1). Since breathing is a medical challenge evident in all preterm infants, it was not surprising that information on it was specifically voiced as an educational need by parents (n=9) and was formulated by a mother from F2 as, ‘If something happens to the infant; they don’t breathe properly or forget to breathe? If he forgets to breathe, what should I do?’. Discharge criteria was mentioned least often (n=7), which can be attributed to mothers being at an early stage in their NICU journey, with their baby not yet ready to go home. Mothers did, however, ask questions such as, ‘When is he supposed to be discharged?’ (F2) and ‘Is the baby stable to go home?’ (F3), supporting the view that discharge planning should be initiated early during the hospital stay.

Infant behaviour was the third most frequently raised issue (n=24). It became clear that some mothers were tuned-in to infant behaviour, with one observing, ‘They’re stressing too much’ (F1), and another, ‘Sometimes you feel that your child is not right’ (F2). Another pondered, ‘Is the baby feeling well or whatever?’ (F3). Mothers did not necessarily seem to have the language to describe infant behaviour, but they did think about it and wanted to know more.

Post-discharge related information. Although exploring educational needs during NICU stay was the focus of FGDs, it is important to note that mothers were already thinking about what their needs would be after discharge. These were similar to their perceived in-hospital needs, with feeding highlighted as the most important (n=30), evident from a question: ‘How long after discharge must I continue breastfeeding?’ (F1). Feeding is the most important mechanism in parent-infant interaction and is directly linked to bonding and maternal emotional health; therefore, it was expected to be the highest education need as well.

Education about infant development (n=20) remained high in the NICU and after discharge, with information sought on handling (n=8) decreasing but still evident as a post-discharge need. This may indicate that mothers already learn/ learnt this information and skills during their infants’ NICU stay.

Category B: Programme Structure

The second main theme relates to the suggested structure of a parent education programme, especially in the South African public sector context, from the parents’ perspective. In this context, ‘structure’ refers to instructional approaches and training logistics.

Instructional approaches included visual format delivery methods. Participants proposed a training booklet (n=5) or pamphlet (n=3), with short descriptions (n=2) and pictures (n=3) explaining the necessary information. Mothers stated, ‘The information booklet requires comprehensive information on the development of the baby’ (F3); ‘They [mothers] read the first page and then they’re tired’ (F1); and ‘It’s fine with pictures’ (F1). Additionally, participants suggested instructional formats such as verbal instruction (n=20), augmented by demonstration (n=12), and group discussions (n=11). A participants stated, ‘I think with the discussion it will help because some of the mommies they are lazy to read’ (F1). The programme presenter should be knowledgeable and be either a speech therapist (n=3) – since, ‘You must see the speech therapist’ (F2) – or a qualified doctor (n=2), rather than an intern, since ‘Qualified doctors have more information than interns’ (F3).

Feedback on training included the duration, timing, frequency, and facilitator type for the educational intervention. Participants mentioned that the frequency of sessions should include continuous learning opportunities (n=2), that occur ‘Almost every day’ (n=6) and preferably occur in the mornings (n=8), since ‘We came here at six o’clock’ (F1). The duration of sessions was not mentioned by mothers; however, it was clear that such sessions should fit in between feeding times and not be longer than 45 minutes, based on mothers’ availability to participate in the FGD and tolerance for being away from their infants.

Category C: Support Needs

Support seemed to influence maternal experiences either positively or negatively, and if mothers’ support needs were not addressed, they seemed unable to identify their own learning needs. Support can be sub-categorised as intrapersonal motivators, communication, and psychological or physical support.

Intrapersonal motivators affecting maternal experiences included perceived maternal involvement in infant care (n=12) and maternal background (n=9). Mothers felt unprepared to care for a preterm infant (n=26), with one mother commenting, ‘Most of the mommies, when we do have these premature babies, we don’t have a heart for them’ (F1). They voiced feelings of stress (n=6) and being judged or blamed (n=6). A range of coping strategies were also identified, including patience (n=4), self-talk (n=4), and accepting the unexpected (n=3).

Comments on communication highlighted negative communication and a lack of communication, especially nurse-caregiver communication (n=24). Mothers mentioned negative communication, ‘Some of the nurses also they become rude, forgetting that you are not there, you didn’t choose to be there, you didn’t choose to have the child at the early’ (F1), and ‘If something bad happens, you’re the wrong one’ (F3). Lack of communication was also identified by mothers as challenging, ‘They do not let us know about the weights; they don’t let us know a lot of things’ (F1); ‘What are we supposed to do, they don’t teach us’ (F2); and ‘You were not given a chance to ask, you were not told anything, you were not updated’ (F3).

Psychological support (n=8) required was evident from mothers who identified their own need for counselling; for example, ‘You need someone to refer you straight to the person who you know will help you with your problems’ (F2). Specific mental support needs were voiced as, ‘I feel most mothers are burdened but they can’t talk about what is happening inside them’ (F2). Finally, a mother from F1 sounded rather desperate when she responded with, ‘Now, I don’t know what, where or how is she. I just see her [the nurse] feeding her, changing nappy, I don’t know anything about my baby’. Peer support is an important need, as expressed by a mother stating, ‘I get healed inside and especially when I meet these people. These people, someone, can come with this advice, you took advice’ (F1).

Physical support needs included resources required, such as accommodation (n=9), internet access (n=4), transport (n=3), financial assistance (n=3), and needing antenatal information (n=3). Mothers asked, ‘Why can’t they allow us to sleep here, all of us?’ and ‘You will need an extra [internet access] data for that’ (F1) and ‘I don’t have money’ (F2).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore parental needs and perceptions regarding a parenting education intervention provided to them while their infants were admitted to the NICU, with a focus on determining their perceived needs regarding content topics, the programme structure, and additional support needs. In our study, we explored these needs and perceptions through three FGDs with mothers whose babies were still admitted to the NICU in a South African public sector hospital. This approach allowed for a rich description of the contextual factors which may influence parental needs and perceptions, as well as depth, to allow for application to similar settings. Data were obtained while parents lived the experience of having a preterm baby admitted to the hospital and could share their experiences and needs while submerged in the situation, instead of relying on recall of their experiences later when dealing with new demands.

Our study is one of the very few qualitative studies exploring parental educational needs from mothers’ personal perspectives while their preterm babies are still admitted to the NICU. Internationally, studies have focused more on evaluating the effectiveness of parent educational interventions, with less published on the process of developing educational interventions or describing the actual parent educational interventions [

3,

4].

In our study, the Content topics category aligned well with published research, suggesting the inclusion of topics in a parenting education programme to cover basic infant care, infant health, infant behaviour, and post-discharge information.

Although the topics may be similar, further exploration is required to understand the contextual differences within each topic. For example, the visuals to explain the NICU environment may differ to reflect each setting, and there may be differences in policy and procedures, but both our participants and literature confirmed the necessity of inclusion of these topics in an educational programme [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. In addition, pictures to explain infant behaviour may be included to reflect the diversity and cultural background of the parents who receive the education, but infant behaviour cues and parent-infant interaction strategies are likely to remain constant across settings. Our findings aligned with literature to include infant behaviour – inclusive of infant cues, communication and interaction – in parent educational materials [

18,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41].

Our study identified variations in the suggested instructional approaches and training logistics for educational interventions (

education programme structure). Our participants favoured materials presented in a visual, printed format, such as a booklet or pamphlet with short descriptions and pictures, similar to the findings of Bracht [

19], Chen [

20], Heo [

22], Khanjari [

42], Milgrom [

37], Morey [

43], Nieves [

38], Ong [

29], Petteys [

39], Peyrovi [

30], Yu [

41] and Yurtsever [

44]. However, the mothers also communicated the need for verbal instruction augmented by demonstrations and group discussions. These modes fit well with the Family Integrated Care (FICare) approach, which utilises bedside demonstrations [

19,

45] and group discussions that also form part of Creating Opportunities for Parent Empowerment (COPE) [

25], FICare [

19,

45], and family-centred care (FCC) [

46]. Verbal instruction seems to favour individual bedside discussions, as described in the literature [

4,

19,

24,

26,

47]. FICare includes individual bedside discussions and group discussions with written materials [

19,

45], while COPE also considers individual discussions [

25] and digital formats to deliver content [

38]. Yurtsever [

44] additionally reported on a web-based education programme in Turkey. In our study’s setting, mothers suggested the use of technology, such as utilising the MomsConnect messaging system, but identified challenges with online training, such as limited data and poor internet connectivity in some areas of South Africa. Our participants preferred presentations in a verbal format and preferably in groups, which may speak to the support obtained from a peer group, as well as the strong social bonds evident in African culture.

Regarding programme delivery, parents in our study suggested numerous educational sessions, even daily, and expressed a preference for mornings. Literature reporting parents’ preferences regarding the time of day for the sessions was not identified in the literature we reviewed. Practical considerations mentioned by our participants around the duration of sessions included their preference for educational sessions to be fitted into the timeframe between feedings, to allow mothers to have maximum time with their babies. Our participants did not comment on a preferred length of sessions, while the consulted literature suggested the duration to vary between 15 minutes [

47] and 120 minutes [

21], with most studies reporting sessions of approximately 60 minutes to have been the most practical (18, 23, 26, 28, 30, 36, 44). Therefore, a maximum length of 60 minutes was suggested as a practical window in our setting.

Interestingly, the conclusions of a high proportion of reviewed literature were not consistent with our findings and suggested that nursing staff are the most common presenters of parent education programmes in low-income settings such as South Korea [

22]; low-middle income countries, including Iran [

4,

23,

27,

28]; upper middle-income countries, including Brazil [

33] and Malaysia [

29]; and high-income countries such as China [

20,

41,

47], the USA [

38,

43], Australia [

45], and Canada [

19]. The use of a speech therapist, also mentioned by our participants, was suggested by only one USA study [

43]. Mothers in our study were quite emphatic that presentations should be made by knowledgeable healthcare professionals and not rotating professionals, such as students or medical interns. This highlights an opportunity to explore how the current workload of nurses may impact available time for parental education and support. It also suggests enhancing healthcare professionals’ training to better equip them for the NICU environment and supporting mothers, with further research potentially improving preparedness and outcomes.

Taken together, the findings of this study highlight the importance of including views of end-users (i.e., parents in the NICU) when designing a parent education programme for a specific setting. The views on content topics seem to be aligned across high- and low-resource settings, but practical considerations such as where, when, how, and by whom should be contextually considered.

Educational interventions do not typically serve psychological needs; however, support needs seem to influence maternal experiences, either positively or negatively. Our study highlighted the importance of support in the NICU as a building block for parents to move towards the identification of their own educational needs, since mothers seemed unable to identify the latter when their support needs were not met.

Established parenting programmes such as FICare, implemented in Canada [

19], Australia [

45] and Spain [

26]; or FCC, implemented in China [

46] and India [

24]; or COPE, which originated in and was implemented in the USA [

48] and proved to be effective in Iran [

25] highlighted the link between NICU parental education programmes and a reduction in negative parental psychological consequences [

3,

49,

50,

51], such as parental stress and anxiety [

3,

19,

52]. This link may therefore explain why our participants focused so strongly on their preference to have their support needs first met, before reflecting on their educational needs.

Our study highlights the importance of positive parental support and mothers’ traumatic experiences in the absence of respectful care. Since nursing staff are the main professional care providers, a huge responsibility lies on their shoulders to interact with parents, be available to answer questions, provide comfort during maternal-infant interaction, practice patience, and treat all parents equally. Our study suggests that resource restrictions lead to staff not being available for this support function, since they must triage their time towards direct infant care. This situation results in a disconnect between parental educational needs and the available resources to address these needs.

Limitations and Strengths of the Study

The context of our qualitative study is important, as it reflects a broader, representative setting of public health NICU contexts in South Africa, where similar challenges and dynamics are often present. However, it is important to note that our findings are limited to a single institution, and the replication of this study in different settings would further enrich the understanding of these issues. Additionally, a limitation of our study is the language barrier, as English was not the first language of any of the participants. Although questions were translated into Setswana by a native Setswana-speaking interviewer and participants were encouraged to respond in their native language, there remains the possibility that some deeper meanings or nuances may not have been fully captured by the researchers. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted with caution considering the potential impact of these language-related factors.

Data saturation was, however, reached within and between FGDs, contributing to the credibility of the data. Credibility was further increased through member checking to ensure that the findings were accurate and reflective of the mother’s experiences [

53], and therefore truthfully represented the population of this study [

54]. The use of a skilled coder and co-coder, in conjunction with a consensus meeting, contributed to the validity of the analysis, as it ensured that multiple perspectives were incorporated into the coding process. Biases were reduced in this manner, while the consistency and reliability of the findings were enhanced.

Transferability was achieved by providing in-depth descriptions, which enables the reader to assess the relevance and applicability of the findings to a larger population [

54]. Confirmability refers to the degree to which the findings of a study, particularly in qualitative research, are based on the data collected from participants and not influenced by the researcher’s biases or interpretations [

54]. The authors have outlined what steps were taken to ensure the integrity of data and the elimination of bias under Methods (above).

Although we intended to explore broader

parental needs, no fathers were identified in the NICU during the study. This seemed to be the case in other settings as well, since some studies were designed with a specific focus on fathers’ roles and experiences [

20]. Therefore, fathers’ needs and involvement could be explored in future studies. A limitation of our study is that biographical data were collected through participant self-reports, and we did not anticipate that mothers would not be sure of data such as birth weight and gestational age.

Implications for Practice and Further Research

Mothers of preterm infants may greatly benefit from a parent education programme during their NICU stay, due to its positive impact on parental and neonatal outcomes. Our study confirmed that the topics parents believe should be included in such a programme seem to be similar across focus groups, irrespective of context; however, further research should be directed towards exploring the best programme structure for various settings. A larger and more diverse sample will also allow for exploring differences in educational needs which may exist in mothers of infants with different gestational age and birth weight, and different groups of mothers, for example, teenage mothers, versus older mothers, and singleton opposed to mothers of multiples. The development of a contextualised parent education programme for the NICU and testing its efficacy and acceptability is therefore suggested for future research. A more in-depth evaluation of neonatal and parental outcomes when a parenting education programme is implemented as an intervention will provide valuable suggestions towards integrating this type of intervention into standard neonatal care. Peer support was briefly mentioned by the participants and could also be investigated as a potential intervention to address the support component of a parent education intervention.

Conclusion

Our qualitative study confirmed findings from previous studies, with the identification of three main areas to be considered in planning programmes to address parents’ educational needs – content topics, structure of the education programme, and support needs of mothers. Content topics can be broadly categorised into NICU-care topics and post-discharge care (which mothers wanted to know about while still in hospital). The mothers in our study emphasised the importance of structuring education programmes in ways that consider factors such as time, materials, and presentation format. While there was no clear consensus on the ideal format, mothers suggested that it is crucial for these programmes to be contextualised to their specific needs and circumstances. This input highlights the need for flexibility and relevance in how educational content is delivered to families in the NICU setting. Parental education needs extend beyond mere dissemination of information; mothers also require respect and a sense of being cared for during their NICU experience, highlighting the importance of good communication, along with psychological and physical support, which need to be addressed as a platform on which to build strategies for effective education.

Author Contributions

Both authors conceptualised the study, revised the manuscript, and interpreted the results. WL conceptualised the paper and prepared the manuscript. KD was responsible for study supervision, technical preparation, and critical review. Both authors contributed to the intellectual content and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Considerations

The larger project within which this study was nested received ethical clearance from the Health Research Ethics Committee of the University of Cape Town (UCT-647/2021). Approval for site access was also obtained through letters from the North West provincial Department of Health and the management of the facility. This study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the South African Ethics in Health Research Guidelines: Principles, Processes and Structures (2024).

Consent to Participate

Participants were provided 24 hours to decide if they wanted to participate in the study, and written informed consent was obtained by an independent person before initiating any data collection procedures.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the study are not publicly available, in order to protect the privacy and confidentiality of the participants due to the qualitative nature of this data. Data supporting the findings are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Vivien Sandt for taking care of the language editing of the manuscript and Mrs Jessica Botha for her valuable input in the technical editing and proofreading of this manuscript.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| COPE |

Creating Opportunities for Parent Empowerment |

| FCC |

Family Centred Care |

| FICare |

Family Integrated Care |

| FGDs |

Focus Group Discussions |

| NICU |

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit |

References

- Furtak SL, Gay CL, Kriz RM, Bisgaard R, Bolick SC, Lothe B, et al. What parents want to know about caring for their preterm infant: a longitudinal descriptive study. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(11):2732–9. [CrossRef]

- Treyvaud K, Spittle A, Anderson PJ, O’Brien K. A multilayered approach is needed in the NICU to support parents after the preterm birth of their infant. Early Hum Dev. 2019;139:104838. [CrossRef]

- Gehl MB, Alter CC, Rider N, Gunther LG, Russell RB. Improving the efficiency and effectiveness of parent education in the neonatal intensive care unit. Adv Neonatal Care. 2020;20(1):59–67. [CrossRef]

- Springer C, Elleman B, Cooper O. The effectiveness of parental education programs within neonatal intensive care units: a systematic review. Res Directs Ther Sci. 2023;2(1). [CrossRef]

- Brett J, Staniszewska S, Newburn M, Jones N, Taylor L. A systematic mapping review of effective interventions for communicating with, supporting, and providing information to parents of preterm infants. BMJ Open. 2011;1(1):e000023. [CrossRef]

- Melnyk BM, Feinstein NF, Alpert-Gillis L, Fairbanks E, Crean HF, Sinkin RA, et al. Reducing premature infants’ length of stay and improving parents’ mental health outcomes with the creating opportunities for parent empowerment (COPE) neonatal intensive care unit program: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):e1414–27. [CrossRef]

- Lubbe W, Donald K, Kruger IM. Key components of parenting education interventions for preterm infant–parent dyads admitted to the NICU: a systematic review. SSRN. 2024. Available from: https://ssrn.com/abstract=.

- University of Witwatersrand. Admissions registers of hospital complex, prepared by nursing services manager. 2023.

- Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed-method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(5):533–44. [CrossRef]

- Marques ICDS, Theiss LM, Johnson CY, McLin E, Ruf BA, Vickers SM, et al. Implementation of virtual focus groups for qualitative data collection in a global pandemic. Am J Surg. 2021;221(5):918–22. [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–4. [CrossRef]

- National Health Research Ethics Council. South African ethics in health research guidelines: principles, processes and structures. 3rd ed. Pretoria: NDoH; 2024.

- Gill P, Stewart K, Treasure E, Chadwick B. Methods of data collection in qualitative research: interviews and focus groups. Br Dent J. 2008;204(6):291–5. [CrossRef]

- Love B, Vetere A, Davis P. Should interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) be used with focus groups? Int J Qual Methods. 2020;19:1609406920921600. [CrossRef]

- Hennink M, Kaiser BN. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: a systematic review of empirical tests. Soc Sci Med. 2022;292:114523. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, JW. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2009.

- Tesch, R. Qualitative research: analysis types and software tools. New York: Falmer; 1990.

- Bostanabad MA, Areshtanab HN, Balila M, Jafarabadi MA, Ravanbakhsh K. Effect of a supportive-training intervention on mother–infant attachment. Iran J Pediatr. 2017;27(6):1–7. [CrossRef]

- Bracht M, O’Leary L, Lee SK, O’Brien K. Implementing family-integrated care in the NICU: a parent education and support program. Adv Neonatal Care. 2013;13(2):115–26. [CrossRef]

- Chen YL, Lee TY, Gau ML, Lin KC. The effectiveness of an intervention program for fathers of hospitalized preterm infants on paternal support and attachment 1 month after discharge. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2019;33(2):160–9. [CrossRef]

- Fotiou C, Vlastarakos PV, Bakoula C, Papagaroufalis K, Bakoyannis G, Darviri C, et al. Parental stress management using relaxation techniques in a neonatal intensive care unit: a randomized controlled trial. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2016;32:20–8. [CrossRef]

- Heo YJ, Oh WO. The effectiveness of a parent participation improvement program for parents on partnership, attachment, and infant growth in a neonatal intensive care unit: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;95:19–27. [CrossRef]

- Jafarzadeh ZA, Maghsoudi J, Barekatain B, Marofi M. Effect of telenursing on attachment and stress in mothers of preterm infants. Iran J Neonatol. 2019;10(1):65–71. [CrossRef]

- Maria A, Litch JA, Stepanchak M, Sarin E, Wadhwa R, Kumar H. Assessment of feasibility and acceptability of family-centered care implemented at a neonatal intensive care unit in India. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21(1). [CrossRef]

- Mianaei SJ, Karahroudy FA, Rassouli M, Tafreshi MZ. The effect of creating opportunities for parent empowerment program on maternal stress, anxiety, and participation in NICU wards in Iran. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2014;19(1):94–100. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3917192/.

- Moreno-Sanz B, Montes MT, Antón M, Serrada MT, Cabrera M, Pellicer A. Scaling up the family integrated care model in a level IIIc neonatal intensive care unit: a systematic approach to the methods and effort taken for implementation. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:682097. [CrossRef]

- Moudi Z, Molashahi B, Ansari H, Imani M. The effect of a care program and social support on anxiety level in mothers of late preterm infants in Sistan and Baluchestan, Iran. Women Health. 2019;59(5):569–78. [CrossRef]

- Mousavi SS, Keramat A, Chaman R, Mohagheghi P, Mousavi SA, Khosravi A. Impact of maternity support program on the stress of mothers in the first encounter with the preterm infants. Int J Prev Med. 2021;12:68. [CrossRef]

- Ong SL, Abdullah KL, Danaee M, Soh KL, Soh KG, Lee DSK, et al. The effectiveness of a structured nursing intervention program on maternal stress and ability among mothers of premature infants in a neonatal intensive care unit. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(3–4):641–9. [CrossRef]

- Peyrovi H, Mosayebi Z, Mohammad-Doost F, Chehrzad MM, Mehran A. The effect of empowerment program on “perceived readiness for discharge” of mothers of premature infants. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(5):752–7. [CrossRef]

- Rostami FF, Soleimani F, Norouzi M, Hatamizadeh N, Mokhtarinouri J, Poshtmashhadi M. Preterm infant neurodevelopmental care training program and mother–infant attachment. Int J Womens Health Reprod Sci. 2020;8(2):192–7. [CrossRef]

- Sivanandan S, Bethou A, Ramanujam SS, Kumar C, Chinnasamy K, Natarajan P, et al. Implementing family-centered care in the neonatal intensive care unit – a quality improvement initiative. Indian J Pediatr. 2021;88(9):872–8. [CrossRef]

- Viera CS, Bugs BM, Fonseca LMM, Guimarães ATB, Machinesk GG. Educative activity and maternal stress of premature infant: controlled trial. Arq Bras Psic. 2019;71:19–35. Available from: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1809-52672019000100003&nrm=iso.

- Chen Y, Zhang J, Bai J. Effect of an educational intervention on parental readiness for premature infant discharge from the neonatal intensive care units. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(1):135–46. [CrossRef]

- Kadiroğlu T, Güdücü T. Effect of infant care training on maternal bonding, motherhood self-efficacy, and self-confidence in mothers of preterm newborns. Matern Child Health J. 2022;26(1):131–8. [CrossRef]

- Lv B, Gao XR, Sun J, Li TT, Liu ZY, Zhu LH, et al. Family-centered care improves clinical outcomes of very-low-birth-weight infants: a quasi-experimental study. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:138. [CrossRef]

- Milgrom J, Newnham C, Martin PR, Anderson PJ, Doyle LW, Hunt RW, et al. Early communication in preterm infants following intervention in the NICU. Early Hum Dev. 2013;89(9):755–62. [CrossRef]

- Nieves H, Clements-Hickman A, Davies CC. Effect of a parent empowerment program on parental stress, satisfaction, and length of stay in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2021;35(1):92–9. [CrossRef]

- Petteys AR, Adoumie D. Mindfulness-based neurodevelopmental care: impact on NICU parent stress and infant length of stay; a randomized controlled pilot study. Adv Neonatal Care. 2018;18(2):E12–22. [CrossRef]

- Phianching K, Chaimongkol N, Pongjaturawit Y. Effects of the parental sensitivity intervention among mothers and fathers of preterm infants: a quasi-experimental study. Pac Rim Int J Nurs Res. 2020;24(2):246–59. Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85085012749&partnerID=40&md5=d41e8bbf659dae5ac3f490c6b24e72b2.

- Yu NKK, Shum KKM, Lam YY, Kwan QKL, Ng SYP, Chan NTT. Sensitivity training for mothers with premature infants: a randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Psychol. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Khanjari S, Bell EF, Mohagheghi P, Sadeghi LS, Haghani S, Rokhsatichenijani E. The effect of family-centered education on the quality of life of the parents of premature infants. J Neonatal Nurs. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Morey JA, Gregory K. Nurse-led education mitigates maternal stress and enhances knowledge in the NICU. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2012;37(3):182–91. [CrossRef]

- Yurtsever G, Efe E. The effect of web-based preterm infant care training on mothers’ self-confidence. Health Care Women Int. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Broom M, Parsons G, Carlisle H, Kecskes Z. Exploring parental and staff perceptions of the family-integrated care model: a qualitative focus group study. Adv Neonatal Care. 2017;17:1. [CrossRef]

- Zhang R, Huang RW, Gao XR, Peng XM, Zhu LH, Rangasamy R, et al. Involvement of parents in the care of preterm infants: a pilot study evaluating a family-centered care intervention in a Chinese neonatal ICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018;19(8):741–7. [CrossRef]

- Cheng YC, Chen LL, Chang YS, Li TC, Chen CJ, Huang LC. The effectiveness of learning portfolios in learning participation and learners’ perceptions of skills and confidence in the mother of preterm infant. Midwifery. 2018;62:86–91. [CrossRef]

- Jahri Sheijani M, Chehrzad MM, Reza Masouleh S, Nezhad Leyli EK, Bidabadi E. The effect of “creating opportunities for parent empowerment” program on parents of children with epilepsy and other chronic neurological conditions. Iran J Child Neurol. 2020;14(1):65–76. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32021630/.

- Ahn YM, Kim NH. Parental perception of neonates, parental stress and education for NICU parents. Asian Nurs Res. 2007;1(3):199–210. [CrossRef]

- Gerstein ED, Njoroge WFM, Paul RA, Smyser CD, Rogers CE. Maternal depression and stress in the neonatal intensive care unit: associations with mother–child interactions at age 5 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(3):350–8.e2. [CrossRef]

- Hunter LML, Blake S, Simmons C, Thompson J, Derouin A. Implementing a parent education program in the special care nursery. J Pediatr Health Care. 2019;33(2):131–7. [CrossRef]

- Khazaii T, Taheri F, Hosseini SM, Parhiz Z, Namdari S. The effects of preterm infant care education on stress among the mothers of preterm infants hospitalized in neonatal intensive care units. Mod Care J. 2018;15(1):e69476. [CrossRef]

- Harper M, Cole P. Member checking: can benefits be gained similar to group therapy? Qual Rep. 2012;17(2):510–7. [CrossRef]

- Roberts K, Dowell A, Nie JB. Attempting rigour and replicability in thematic analysis of qualitative research data: a case study of codebook development. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):1–8. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).