1. Introduction

Cosmic rays are high-energy particles originating from outer space that continuously bombard the Earth’s atmosphere [

1,

2]. When these primary cosmic rays, mainly protons and heavier nuclei, interact with atmospheric nuclei, they produce cascades of secondary particles in a process known as an extensive air shower [

3]. These showers contain a variety of particles, including muons, electrons, photons, and hadrons, which can reach ground level depending on their energy and the altitude of the observation site [

4]. The study of these secondary particles provides valuable insights into the nature and origin of cosmic radiation, as well as fundamental processes in high-energy astrophysics and particle interactions in the atmosphere [

5]. Detecting and characterizing these particles requires specialized instrumentation capable of capturing their signatures with high efficiency and precision.

Among the instruments used to detect secondary cosmic ray particles, Water Cherenkov Detectors (WCDs) stand out due to their high efficiency in identifying the signals produced by these particles [

6]. This efficiency, combined with their relatively low cost, has made WCDs widely adopted in astroparticle physics experiments. Notable examples include INCA in Chacaltaya, Bolivia (5200 m a.s.l.) [

7]; Milagro in New Mexico, USA (2650 m a.s.l.) [

8]; the Pierre Auger Observatory in Malargüe, Argentina (1400 m a.s.l.) [

9]; HAWC (High-Altitude Water Cherenkov Observatory) in Sierra Negra, Mexico (4500 m a.s.l.) [

10]; LHASSO (Large High Altitude Air Shower Observatory) in Sichuan, China (4410 m a.s.l.) [

11]; and the Latin American Giant Observatory (LAGO), distributed across Latin America [

12].

In these detectors, water serves as the dielectric medium for generating Cherenkov radiation. When high-energy charged particles pass through water at speeds exceeding the phase velocity of light in the medium, they emit Cherenkov photons. These photons are detected by photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) positioned inside the tank [

13,

14]. The design of the detector can vary depending on the experimental objectives, allowing optimization for specific particle types or energy ranges [

15]. PMTs operate by converting incoming Cherenkov photons into photoelectrons via the photoelectric effect. These photoelectrons are then accelerated and amplified through a cascade of dynodes, generating measurable electric pulses [

16]. This amplification process enables the detection of even faint Cherenkov signals, making the WCD highly effective in registering the passage of relativistic particles.

To improve light collection efficiency, the interior walls of the detector tanks are often lined with reflective materials, such as Tyvek. Due to its high reflectivity and durability, Tyvek enhances the redirection of Cherenkov photons toward the PMTs, thereby reducing light losses and improving the overall sensitivity of the detector [

17].

Beyond their ability to detect charged secondary particles, WCDs are also effective in identifying photons, particularly those originating from cosmic radiation [

18]. In one cubic meter of water, the probability of photon conversion into an electron–positron pair (

) is significantly high [

19]. Furthermore, the versatility of WCDs has recently been expanded to include neutron detection [

20,

21,

22], opening new possibilities for their application across a broader range of scientific investigations, including nuclear monitoring and space weather studies.

Given the versatility and widespread adoption of WCDs in astroparticle physics, a deeper understanding of the distinct signals produced by different secondary particles is essential for improving detection performance and interpretation accuracy. This work systematically investigates the characteristic responses of muons, electrons, photons, and hadrons (protons and neutrons) in atmospheric showers as recorded by a WCD. The novelty of this study lies in its comprehensive characterization and comparison of the detector’s response to each particle species individually. By providing a systematic analysis of energy deposition, Cherenkov photon production, and PMT signal formation, the study advances particle identification strategies in WCDs and offers valuable insights for optimizing the performance of current and future astroparticle experiments. This paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the simulation methodology, detailing the two-stage framework based on the Cosmic-Ray Shower Generator and the Geant4 Monte Carlo toolkit.

Section 3 discusses the simulation results, focusing on the detector response to the different particle species. Finally,

Section 4 summarizes the main findings and highlights their implications for particle identification in WCDs.

2. Materials and Methods

To investigate the response of the WCD to secondary particles from extensive air showers, a two-stage simulation framework was implemented. First, secondary particles at ground level were generated using the CRY (cosmic ray Shower Generator) toolkit, which provides realistic particle fluxes based on empirical cosmic-ray spectra. In the second stage, the interactions of these particles within the WCD were modeled using the Geant4 Monte Carlo simulation toolkit. This framework allows for a detailed analysis of energy deposition, Cherenkov photon production, and signal formation in the photomultiplier tube. The following subsections describe the configuration and use of both CRY and Geant4 in this study.

2.1. CRY - Cosmic-Ray Shower Generator

CRY is a software library that generates secondary particle distributions from cosmic ray-induced atmospheric showers at various altitudes (sea level, 2100 m, and 11,300 m a.s.l.) for use in detector simulations [

23]. It relies on precomputed tables from MCNPX simulations of primary cosmic-ray interactions with the atmosphere, showing good agreement with experimental data [

24]. CRY provides fluxes of muons, neutrons, protons, electrons, photons, and pions within user-defined areas and altitudes, sampling their energy, arrival time, zenith angle, and multiplicity. It supports geomagnetic cutoff and solar cycle effects, and can be integrated into C, C++, Fortran, and Monte Carlo frameworks, such as Geant4. The toolkit is available at

http://nuclear.llnl.gov/simulation.

The primary cosmic rays used in the CRY simulation are protons with energies ranging from 1 GeV to 100 TeV, which are injected at the top of the atmosphere. The atmosphere was modeled as a series of 42 flat density layers, each composed of 78% N

2, 21% O

2, and 1% Ar by volume. The density change between adjacent layers was set at 10%, with values derived from the 1976 U.S. Standard Atmosphere model. The top of the atmosphere is located at an altitude of approximately 31 km, with an integrated column density of about 1000 g/cm

2 [

23].

In this work, the distribution of secondary cosmic ray particles at sea level was used, corresponding to the latitude of Campina Grande, Paraíba, Brazil (7.2206° S). This latitude was randomly chosen for the study and could be replaced by that of any other city worldwide. The latitude is employed to adjust the primary cosmic ray spectrum by accounting for the geomagnetic field. Additionally, a specific date (in month-day-year format) was set to adjust the cosmic ray spectrum according to the 11-year solar cycle [

25]. The solar cycle, also known as the solar magnetic activity cycle, is an approximately 11-year periodic variation in solar activity, measured by changes in the number of sunspots observed on the solar surface. During periods of high solar activity, the Sun’s emissions of matter and electromagnetic fields increase, making it more difficult for galactic cosmic rays to reach Earth. Consequently, cosmic-ray intensity is lower when solar activity is high.

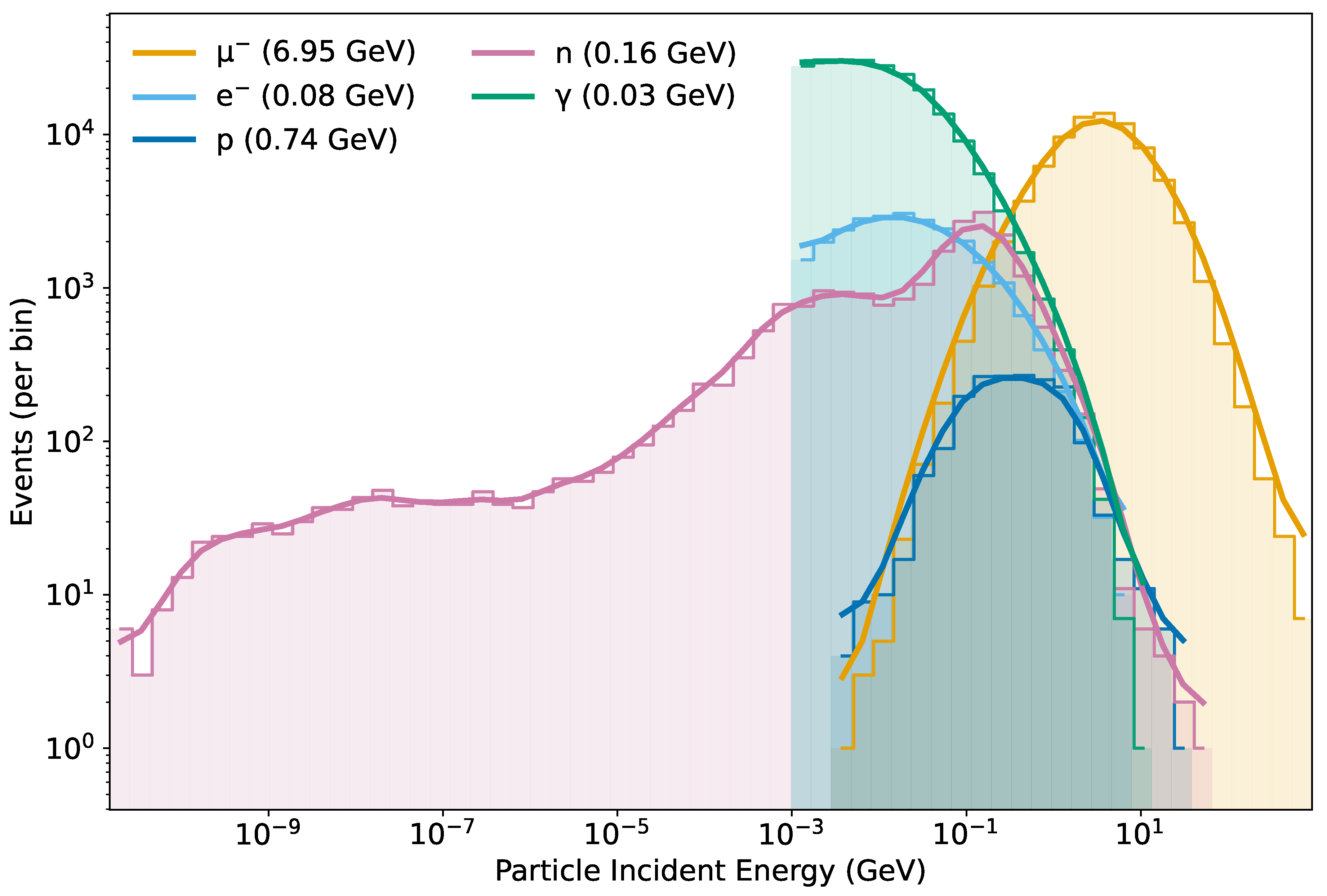

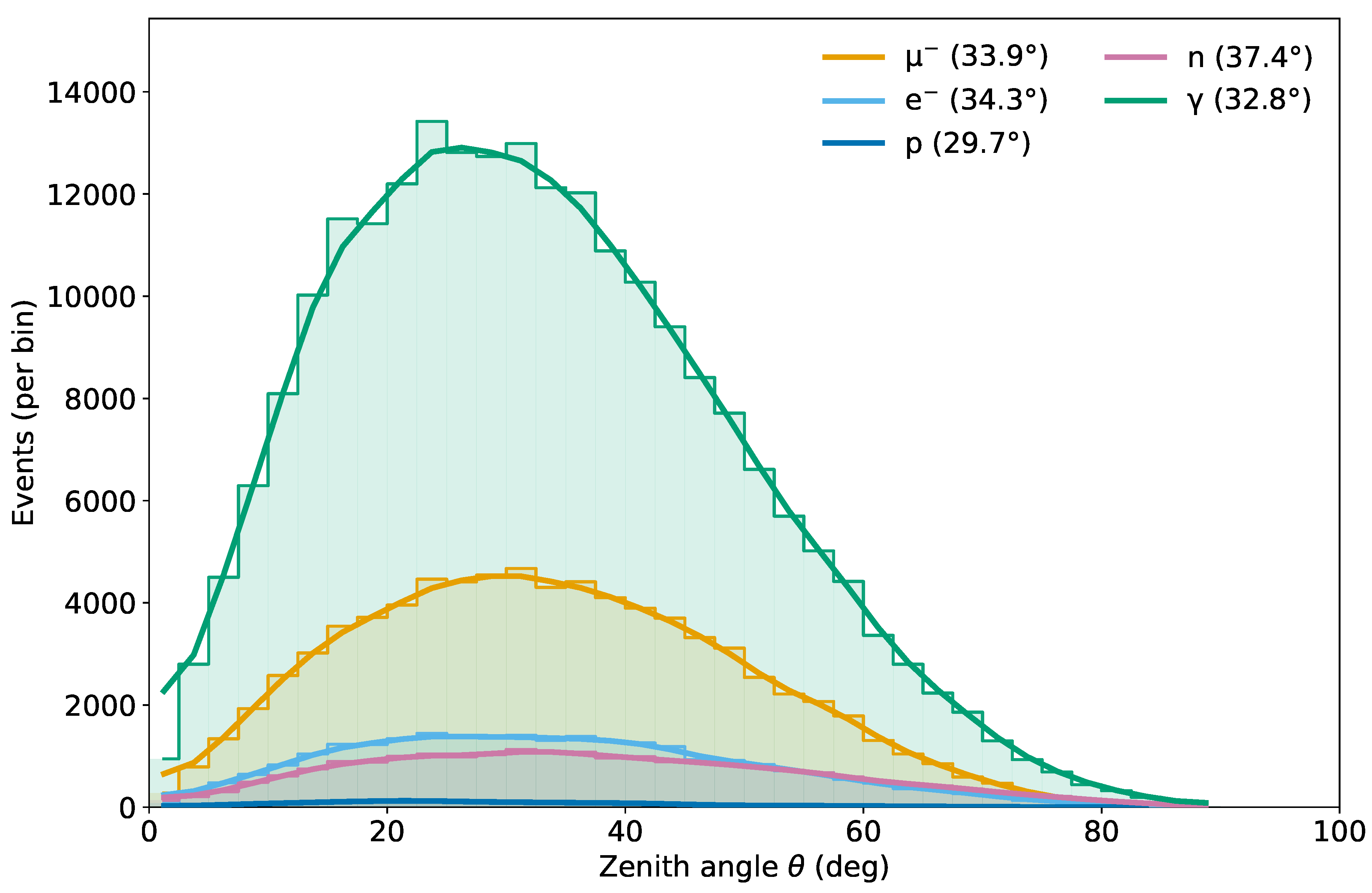

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 display the

event–count distributions of incident energy (events per logarithmic bin) and zenith angle (events per bin), with

expressed in degrees. For cross–species comparability, we use shared binning—energy in 60 logarithmic bins spanning the data range with a 5% margin, and

in 72 linear bins over

–

. A support–aware Gaussian smoothing curve (reflective padding; no extrapolation beyond populated bins) is overlaid purely to guide the eye, and the legends report the corresponding mean values. From these distributions, muons are the most energetic particles reaching the ground, while the electromagnetic component (electrons and photons) dominates in abundance at the detector level, followed by muons and then hadrons (protons and neutrons).

2.2. Monte Carlo Simulation Framework Using Geant4

The geometry of the Water Cherenkov Detector (WCD) was implemented using the Geant4 simulation toolkit. Geant4 (GEometry ANd Tracking 4)

1 is a widely used platform for simulating the interaction of electromagnetic and hadronic radiation with matter [

26]. In this work, the detector was modeled as a cylindrical structure with a total height of 2.3 meters, containing a 1.9-meter water column. This setup represents a fully filled and stable tank, neglecting evaporation losses. The inner cavity is enclosed by a polyethylene wall, which is internally lined with Tyvek, a highly reflective material that enhances Cherenkov photon collection. This configuration enables a detailed and consistent simulation of particle interactions within the medium, offering precise control of physical parameters and ensuring the reproducibility of the results. Moreover, the model allows for straightforward adjustments to geometry and material properties, facilitating performance studies and future optimization.

As previously mentioned, all simulations involving the transport and interaction of cosmic radiation within the water Cherenkov detector were carried out using the Geant4 toolkit. To model hadronic interactions within the detector medium, the simulations employed the

QGSP_INCLXX_HP reference physics list. This list combines the quark-gluon string model (QGSP) to describe nucleon and pion interactions at energies above approximately 15 GeV, followed by the pre-equilibrium de-excitation of the resulting nuclear fragments. For lower incident energies, the Liège intra-nuclear cascade model (INCL++) is used, which has been extensively redesigned to improve accuracy in simulating cascades of interactions within atomic nuclei that are relevant for secondary interactions occurring in water and structural materials. The

_HP suffix refers to the High-Precision

NeutronHP extension, which incorporates evaluated cross-section data from the

ENDF/B-VII.1 library to accurately simulate neutron elastic and inelastic scattering below 20 MeV, an important consideration for modeling background processes in water-based detectors. Electromagnetic processes involving charged particles, gamma rays, and optical photons (such as Cherenkov light) are handled using the

G4EmStandardPhysics package, the recommended physics constructor for high-energy applications [

27]. This ensures the accurate treatment of both primary and secondary particles, as well as the generation and propagation of Cherenkov radiation within the detector volume.

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents the simulation results for the WCD response to secondary particles generated in atmospheric showers. The analysis focuses on the key physical processes that govern the detector’s performance. First, we examine the energy deposition profiles of muons, electrons, photons, and hadrons within the water volume to assess their respective contributions to the overall detector signal. Next, we analyze the generation and spatial distribution of Cherenkov photons arising from these energy depositions, providing insight into the light yield associated with each particle type. Finally, we investigate the propagation of Cherenkov photons to the photomultiplier tube (PMT), with emphasis on photoelectron production and the resulting charge spectra. Together, these results provide a comprehensive characterization of the WCD’s capability to detect and distinguish between different secondary particles in extensive air showers.

3.1. Energy Deposition of Secondary Particles in the WCD

The distributions of energy deposited by secondary particles in the WCD were evaluated through Monte Carlo simulations. These particles, muons, electrons/positrons, photons, and hadrons, originate from extensive air showers initiated by high-energy primaries and lose energy in water predominantly through ionization, with additional electromagnetic (Compton scattering and pair production) and hadronic processes contributing depending on the particle type.

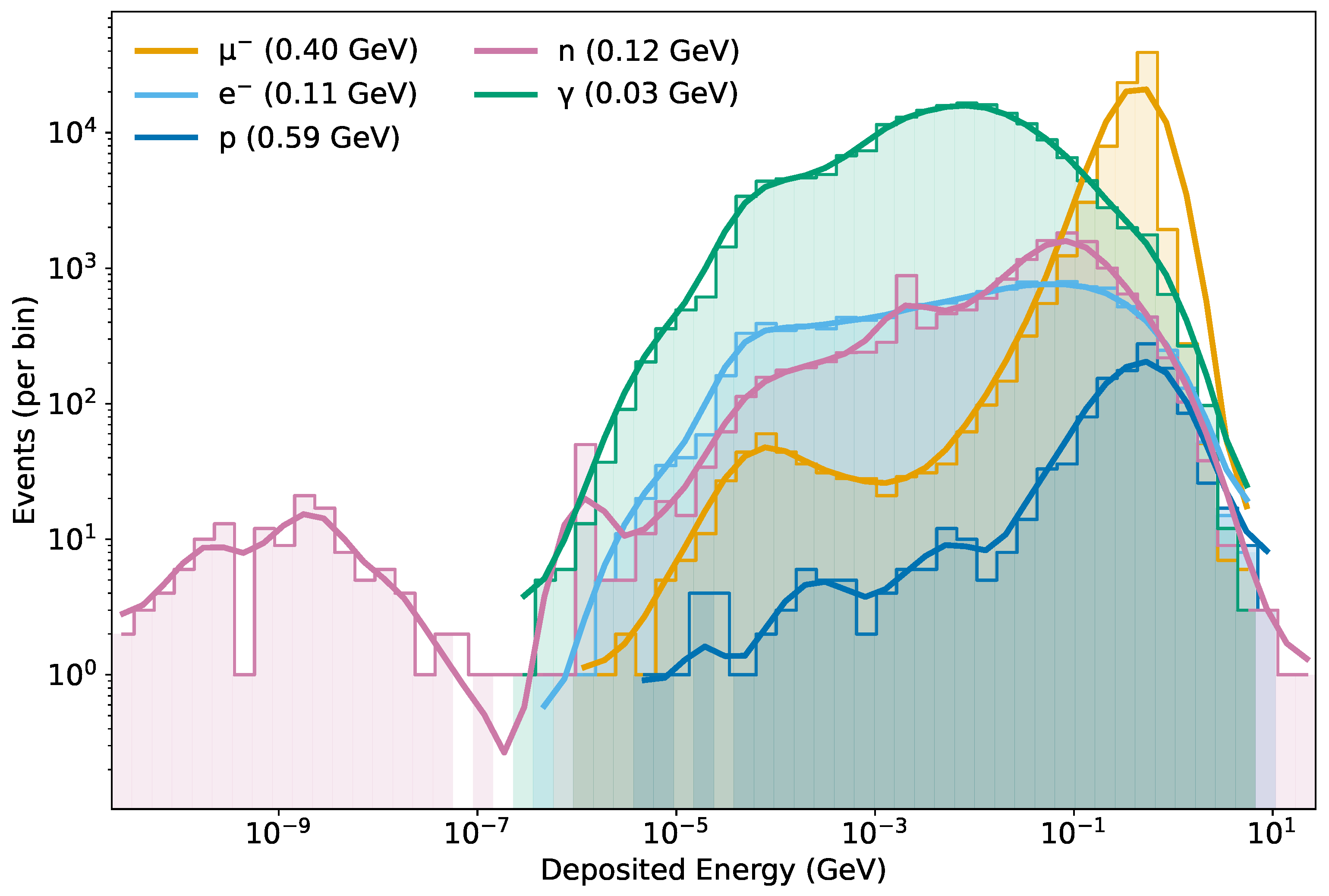

Figure 3 shows the event–count distributions of deposited energy (events per logarithmic bin) for the main secondary particle species, constructed with shared logarithmic binning across species and smoothed with a Gaussian filter for visualization. Since the vertical axis reports raw event counts per bin, the amplitudes encode both the relative abundance of each species at the detector level and the underlying sample statistics. The mean deposited energies are approximately

GeV for muons,

GeV for electrons,

GeV for photons,

GeV for protons, and

GeV for neutrons.

Electrons and photons dominate the low deposited-energy region, where energy loss is governed by ionization, Compton scattering, and pair production, in agreement with standard electromagnetic shower physics [

2,

28]. Protons exhibit a broader distribution with a higher mean (

GeV), reflecting occasional inelastic nuclear interactions that transfer substantial energy to the medium [

4,

29]. Muons, typically behaving as minimum-ionizing particles, present an intermediate mean (

GeV). Their distribution, however, reveals a two-hump structure: a smaller peak centered near

GeV, corresponding to short or grazing trajectories that deposit only limited energy before exiting the detector, and a larger peak around 1 GeV, associated with through-going tracks that release nearly constant energy along the full water depth, consistent with observations reported in Auger and HAWC WCD studies [

9,

30].

Neutrons also display a two-band structure in their energy deposition spectra. A lower band is centered near

GeV, reflecting low-energy recoil protons from single elastic scattering on hydrogen, while a more prominent band emerges around

GeV, linked to capture-induced

emission and subsequent pair-production processes. Similar neutron capture signatures have been identified in underground and surface detector simulations [

21,

22,

26,

31]. These dual features illustrate the distinctive character of neutron interactions, which combine elastic scattering with secondary photon production mechanisms.

Taken together, these results indicate that while electromagnetic secondaries dominate at low deposited energies due to their abundance, muons and hadrons contribute larger per-event energy deposits, with muons and neutrons exhibiting unique multi-peaked structures that enhance their potential for discrimination in WCD-based analyzes.

3.2. Cherenkov Photon Production by Secondary Particles in the WCD

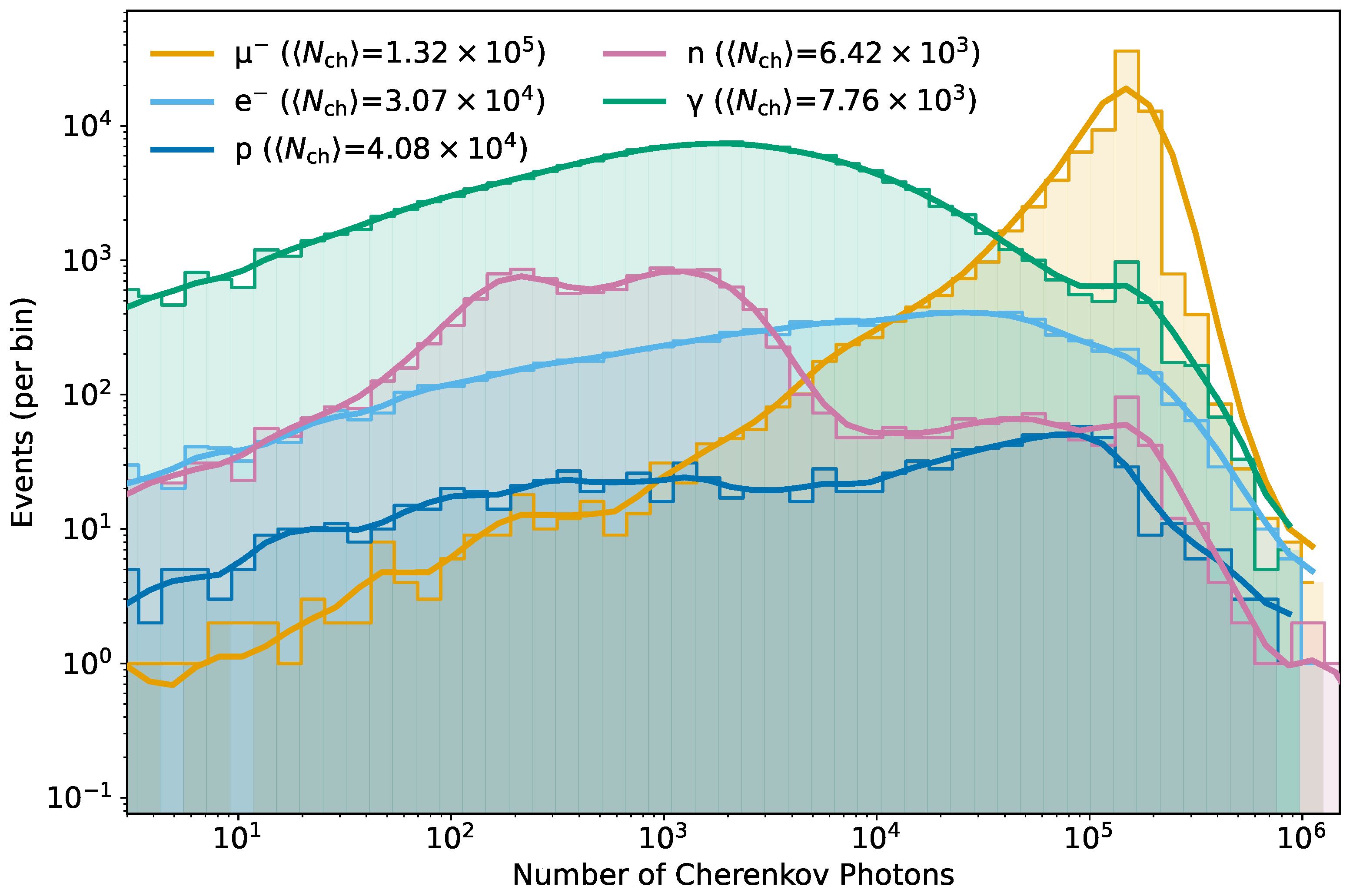

The production of Cherenkov photons in the WCD is a fundamental process that directly determines the detector’s capability to register and identify relativistic secondary particles from extensive air showers. Using detailed Monte Carlo simulations in a 1.90 m water column, we evaluated the photon yields for muons, electrons, photons, protons, and neutrons.

Figure 4 presents the event–count distributions of Cherenkov photon multiplicity

(events per logarithmic bin) for the five species, adopting the same plotting conventions as in the deposited–energy distributions: shared logarithmic binning, log–log axes, and Gaussian smoothing overlaid only to guide the eye. Because the ordinate reports raw counts per bin, amplitudes encode both the relative abundance of particles at the detector level and the simulation statistics, while the curve shapes reflect the underlying production mechanisms and effective path lengths in water. The legend lists the mean multiplicities

for each species.

The observed species-dependent features are consistent with expectations for water Cherenkov detectors. Muons, with long above-threshold tracks, produce the most extended high–

tail, reflecting their role as efficient Cherenkov emitters. Electrons and positrons, being lighter, experience stronger multiple scattering and shower development; they populate the lower-to-intermediate

range but contribute substantially to the overall light yield due to their high abundance at sea level [

2,

5,

13,

26]. Photons, though neutral, contribute indirectly: above 1.022,MeV, they undergo pair production, generating

that emit Cherenkov light as they propagate [

4,

14]. This channel becomes increasingly important at high energies and has been confirmed in WCD observations [

9,

10].

Hadrons interact primarily through nuclear processes. Charged hadrons, especially protons, can emit Cherenkov photons once their kinetic energy exceeds the water threshold of ∼480 MeV (

). The yields scale with both track length and velocity [

6,

13,

14,

27]. In our simulations, only a fraction of secondary protons arrive above the threshold, leading to photon production that is systematically lower than that for relativistic muons due to their shorter average path lengths and lower velocities [

9]. Neutrons, in contrast, do not radiate directly but contribute through charged recoil secondaries produced in elastic and inelastic interactions, as well as via capture

rays that convert into

pairs [

18,

19,

20,

22]. Similar neutron-induced contributions have been reported in Auger and HAWC detectors [

9,

10]. Finally, the Tyvek lining of the inner walls enhances light collection by diffusively reflecting photons toward the PMT, improving the detection probability. This effect is particularly relevant for low-yield cases, such as photons and neutron-induced events. Overall, the

distributions highlight the WCD’s efficiency across multiple particle species and confirm the usefulness of photon-yield-based observables for particle discrimination in ground-based cosmic-ray experiments. Finally, the Tyvek lining of the inner walls enhances light collection by diffusively reflecting photons toward the PMT, thereby improving the detection probability. This effect is particularly relevant for low-yield cases, such as photon and neutron-induced events. Overall, the

distributions highlight the WCD’s efficiency across multiple particle species and confirm the usefulness of photon-yield-based observables for particle discrimination in ground-based cosmic-ray experiments.

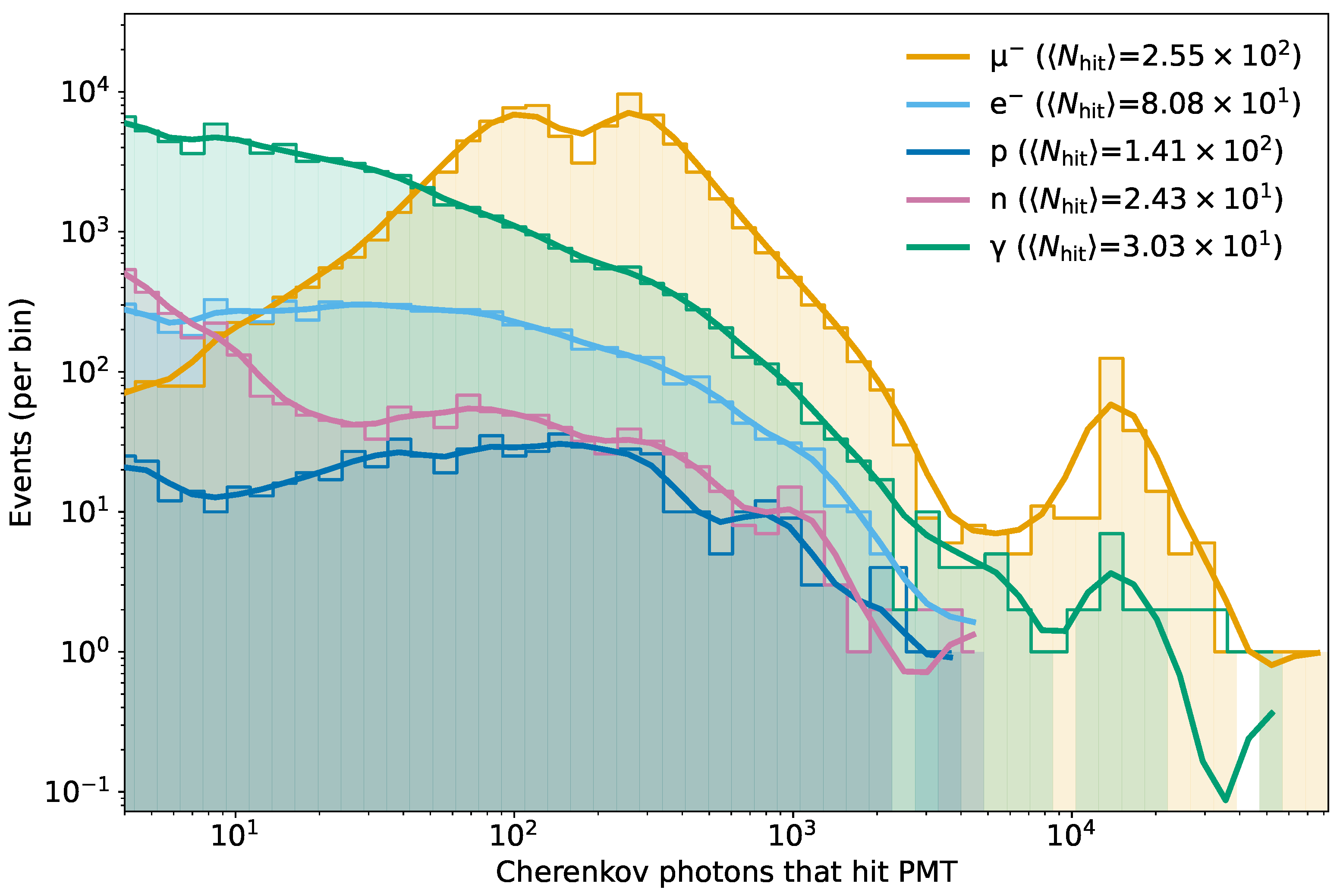

3.3. Photoelectron Production and Charge Response in the PMT

The response of the photomultiplier tube (PMT) provides the final observable link between the energy deposited in the WCD and the measurable electronic signal. After being produced in the water volume, Cherenkov photons propagate toward the PMT, where they may convert to photoelectrons with a probability set by the photocathode quantum efficiency (

). For typical bialkali PMTs used in astroparticle detectors,

in the Cherenkov band (300–600 nm) is about 20–30% [

13,

16]. Each photoelectron is subsequently multiplied through the dynode chain, yielding an anode charge pulse proportional to the number of detected photons.

Two complementary observables capture this response: the number of Cherenkov photons reaching the PMT window (

) and the integrated anode charge (

Q).

Figure 5 presents the event–count distributions of

for secondary muons, electrons/positrons, photons, protons, and neutrons, following the same conventions as in the deposited–energy spectra. The mean values are

for muons,

for electrons,

for photons,

for protons, and

for neutrons. As expected from their extended above-threshold tracks, muons display the broadest distribution and the most extended high–

tail. Their spectrum exhibits a two-hump structure, with a smaller bump at low photon counts corresponding to partially contained or short-path events, and a larger bump at high counts associated with through-going muons that deposit nearly constant energy along the full tank depth. This dual structure parallels the two-band pattern already noted in the deposited-energy spectra, underlining the consistency of muon behavior across all observables. Electrons and positrons, strongly scattered and prone to electromagnetic cascades, populate the lower-to-intermediate region, while photons contribute indirectly through pair production above 1.022 MeV [

4,

10,

14]. Protons contribute only when above the ∼480 MeV Cherenkov threshold [

6,

14], and neutrons yield the lowest averages, consistent with their indirect energy-deposition channels via recoil protons and capture

rays [

20,

22].

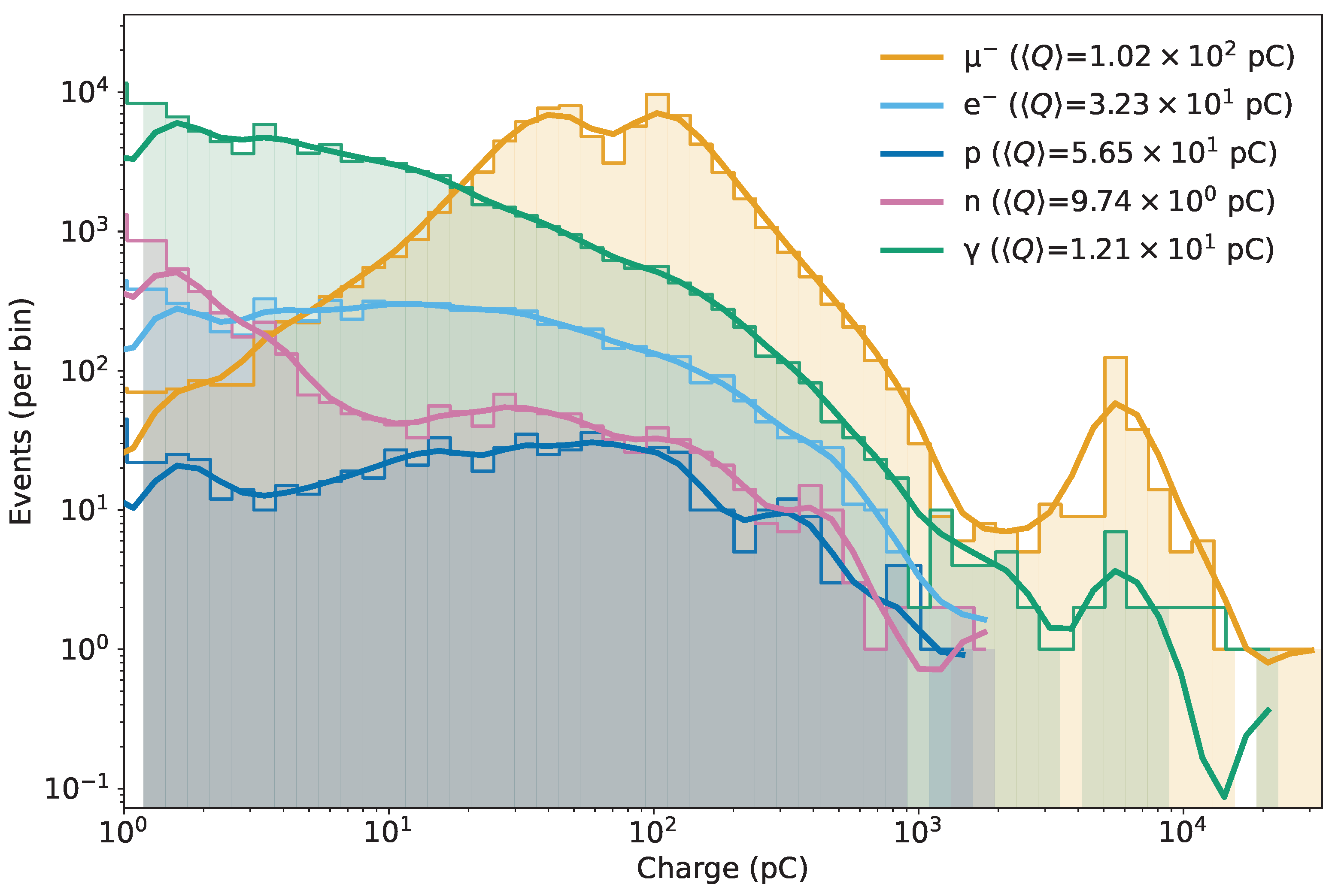

Figure 6 presents the corresponding distributions of anode charge

Q (pC). The mean charges are

pC for muons,

pC for electrons,

pC for photons,

pC for protons, and

pC for neutrons.

Figure 6 presents the corresponding event–count distributions of anode charge

Q (pC). The conversion between

and

Q is given by

which, for

, gain

, and electron charge

,C, reduces numerically to

Accordingly, the mean charges scale linearly with the mean hit counts, yielding

pC for muons,

pC for electrons,

pC for photons,

pC for protons, and

pC for neutrons. The double-hump pattern observed for muons in

is also visible in

Q, reinforcing the interpretation that short vs. through-going tracks generate distinct sub-populations in the detector response. Electrons and photons cluster at lower charges, protons at intermediate values, and neutrons at the lowest, fully consistent with the hierarchy of deposited energies and photon yields discussed in the previous section.

These results highlight the direct chain linking energy deposition Cherenkov photon production photon collection at the PMT measured charge. The agreement between the species-dependent features in deposited energy, photon multiplicity, and PMT charge underscores the robustness of the simulation framework. Moreover, the distinct mean values and multi-peaked structures provide practical handles for trigger design and particle identification in large-scale cosmic-ray observatories.

4. Conclusions

This work presents a detailed Monte Carlo simulation of a water Cherenkov detector (WCD), using CRY sea-level secondaries as input to model the response to muons, electrons, photons, and hadrons. The simulation chain reproduces the key processes relevant to WCDs: Cherenkov photon production in water, optical transport (including reflections on the inner lining), and conversion to photoelectrons at the PMT. The resulting observables, incident energy, and zenith-angle distributions at the detector level, deposited energy, Cherenkov-photon multiplicity , PMT hit count , and anode charge Q—were constructed with shared logarithmic binning across particle species and analyzed as event counts per bin for direct comparison.

Across all observables, the species-dependent trends are consistent with expectations for a WCD of height 1.90 m. Muons, with their long above-threshold tracks, dominate the high tails of the , , and Q spectra. Electrons/positrons and photon-induced pairs populate the lower-to-intermediate ranges, contributing substantially to multiplicity. Hadrons, though less abundant at ground level, can deposit significant energy and generate Cherenkov light when protons exceed the threshold or when neutron interactions yield charged secondaries and capture rays. The qualitative behavior agrees with prior experimental observations (e.g., Pierre Auger and HAWC), supporting the realism of the modeled response.

These results clarify how particle-dependent track lengths and interaction mechanisms translate into distinct optical and charge signatures in WCDs. They highlight the potential of - and Q-based observables, possibly in combination with timing, for trigger optimization and particle identification in ground-based cosmic-ray experiments. Future work will refine the mapping from optical photons to charge by systematically varying PMT quantum efficiency, gain, and inner-lining reflectivity, as well as by extending the study to array layouts and site-specific atmospheric conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Stuani Pereira, L.A.; methodology, Stuani Pereira, L.A.; software and validation, Stuani Pereira, L.A. and Santos, R.H.; formal analysis, Stuani Pereira, L.A.; investigation, Stuani Pereira, L.A.; data curation, Stuani Pereira, L.A. and Santos, R.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Stuani Pereira, L.A. and Santos, R.H.; writing—review and editing, Stuani Pereira, L.A.; visualization, Stuani Pereira, L.A.; supervision, Stuani Pereira, L.A.; project administration, Stuani Pereira, L.A.; funding acquisition, Stuani Pereira, L.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Stuani Pereira, L.A. gratefully acknowledges financial support from FAPESP under grant numbers 2021/01089-1, 2024/02267-9, and 2024/14769-9, and CNPq under grant numbers 403337/2024-0, 153839/2024-4, and 200164/2025-2.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Stanev, T. High Energy Cosmic Rays, 2 ed.; Springer Praxis Books, Astronomy and Planetary Sciences, Springer Science & Business Media, 2010.

- Gaisser, T.; Engel, R.; Resconi, E. Cosmic Rays and Particle Physics; 2016; pp. 1–444. [CrossRef]

- Heck, D.; Knapp, J.; Capdevielle, J.N.; Schatz, G.; Thouw, T. CORSIKA: A Monte Carlo code to simulate extensive air showers 1998.

- Engel, R.; Heck, D.; Pierog, T. Extensive Air Showers and Hadronic Interactions at High Energy. Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science 2011, 61, 467–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blümer, J.; Engel, R.; Hörandel, J.R. Cosmic rays from the knee to the highest energies. Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics 2009, 63, 293–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etchegoyen, A.; Bauleo, P.; Bertou, X.; Bonifazi, C.; Filevich, A.; Medina, M.; Melo, D.; Rovero, A.; Supanitsky, A.; Tamashiro, A.; et al. Muon-track studies in a water Cherenkov detector. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2005, 545, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, R.; Castellina, A.; Ghia, P.; Kakimoto, F.; Kaneko, T.; Morello, C.; Navarra, G.; Nishi, K.; Saavedra, O.; Trinchero, G.; et al. Search for GeV GRBs with the INCA experiment. Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series 1999, 138, 599–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone for Milagro collaboration, A. Detection of 6 November 1997 ground level event by Milagrito. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings. American Institute of Physics, 2000, Vol. 510, pp. 574–578.

- Abraham, J.; Aglietta, M.; Aguirre, I.; Albrow, M.; Allard, D.; Allekotte, I.; Allison, P.; Muniz, J.A.; Do Amaral, M.; Ambrosio, M.; et al. Properties and performance of the prototype instrument for the Pierre Auger Observatory. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2004, 523, 50–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeysekara, A.; Aguilar, J.; Aguilar, S.; Alfaro, R.; Almaraz, E.; Álvarez, C.; Álvarez-Romero, J.d.D.; Álvarez, M.; Arceo, R.; Arteaga-Velázquez, J.; et al. On the sensitivity of the HAWC observatory to gamma-ray bursts. Astroparticle Physics 2012, 35, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- collaboration, L.; et al. A future project at tibet: the large high altitude air shower observatory (LHAASO). Chinese Physics C 2010, 34, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asorey, H.; Núñez, L.A.; Suárez-Durán, M.; Torres-Nino, L.; Rodríguez-Pascual, M.; Rubio-Montero, A.J.; Mayo-García, R. The latin american giant observatory: a successful collaboration in latin america based on cosmic rays and computer science domains. In Proceedings of the 2016 16th IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Cluster, Cloud and Grid Computing (CCGrid). IEEE, 2016, pp. 707–711. [CrossRef]

- Knoll, G.F. Radiation Detection and Measurement; John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

- Patrignani, C. Review of Particle Physics. Chinese Physics C 2016, 40, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aab, A.; Abreu, P.; Aglietta, M.; Ahlers, M.; Ahn, E.J.; Albuquerque, I.; Allekotte, I.; Allen, J.; Allison, P.; Almela, A.; et al. The Pierre Auger Observatory: Contributions to the 33rd International Cosmic Ray Conference (ICRC 2013) 2013.

- Hamamatsu Photonics K.K.. Photomultiplier Tubes: Basics and Applications. Hamamatsu City, Japan, 3rd ed., 2007.

- Asorey, H. LAGO: the Latin American Giant Observatory. 08 2016, p. 247. [CrossRef]

- Allard, D.; Allekotte, I.; Alvarez, C.; Asorey, H.; Barros, H.; Bertou, X.; Burgoa, O.; Berisso, M.G.; Martínez, O.; Loza, P.M.; et al. Use of water-Cherenkov detectors to detect gamma ray bursts at the Large Aperture GRB Observatory (LAGO). Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2008, 595, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asorey, H.G. Los detectores Cherenkov del observatorio Pierre Auger y su aplicación al estudio de fondos de radiación. PhD thesis, Universidad Nacional de Cuyo, 2012.

- Sidelnik, I.; Asorey, H.; Guarin, N.; Durán, M.S.; Lipovetzky, J.; Arnaldi, L.H.; Pérez, M.; Haro, M.S.; Berisso, M.G.; Bessia, F.A.; et al. Enhancing neutron detection capabilities of a water Cherenkov detector. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2020, 955, 163172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidelnik, I.; Asorey, H.; Guarin, N.; Durán, M.S.; Bessia, F.A.; Arnaldi, L.H.; Berisso, M.G.; Lipovetzky, J.; Pérez, M.; Haro, M.S.; et al. Neutron detection capabilities of water Cherenkov detectors. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2020, 952, 161962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, H.; Zhang, H.; Abe, K.; Hayato, Y.; Iida, T.; Ikeda, M.; Kameda, J.; Kobayashi, K.; Koshio, Y.; Miura, M.; et al. First study of neutron tagging with a water Cherenkov detector. Astroparticle Physics 2009, 31, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagmann, C.; Lange, D.; Wright, D. Cosmic-ray shower generator (CRY) for Monte Carlo transport codes. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium Conference Record, 2007, Vol. 2, pp. 1143–1146. [CrossRef]

- Waters, L.S.; McKinney, G.W.; Durkee, J.W.; Fensin, M.L.; Hendricks, J.S.; James, M.R.; Johns, R.C.; Pelowitz, D.B. The MCNPX Monte Carlo Radiation Transport Code. AIP Conference Proceedings 2007, 896, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usoskin, I.G.; Solanki, S.K.; Krivova, N.A.; Hofer, B.; Kovaltsov, G.A.; Wacker, L.; Brehm, N.; Kromer, B. Solar cyclic activity over the last millennium reconstructed from annual 14C data. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2021, 649, A141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinelli, S.; Allison, J.; Amako, K.a.; Apostolakis, J.; Araujo, H.; Arce, P.; Asai, M.; Axen, D.; Banerjee, S.; Barrand, G.; et al. GEANT4—a simulation toolkit. Nuclear instruments and methods in physics research section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2003, 506, 250–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geant4 Collaboration. Geant4 Physics Reference Manual. Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. Available online: https://geant4-userdoc.web.cern.ch/UsersGuides/PhysicsReferenceManual/.

- Battistoni, G.; Cerutti, F.; Fassò, A.; Ferrari, A.; Muraro, S.; Ranft, J.; Roesler, S.; Sala, P.R. The FLUKA code: description and benchmarking. In Proceedings of the Hadronic Shower Simulition Workshop; Albrow, M.; Raja, R., Eds. AIP, 2007, Vol. 896, American Institute of Physics Conference Series, pp. 31–49. [CrossRef]

- Ostapchenko, S. Monte Carlo treatment of hadronic interactions in enhanced Pomeron scheme: I. QGSJET-II model. Phys. Rev. D 2011, 83, 014018, [arXiv:hep-ph/1010.1869]. [CrossRef]

- Abeysekara, A.U.; Albert, A.; Alfaro, R.; Alvarez, C.; Álvarez, J.D.; Arceo, R.; Arteaga-Velázquez, J.C.; Ayala Solares, H.A.; Barber, A.S.; Bautista-Elivar, N.; et al. Observation of the Crab Nebula with the HAWC Gamma-Ray Observatory. apj 2017, 843, 39, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1701.01778]. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.R.; Andringa, S.; Askins, M.; Auty, D.J.; Barros, N.; Barão, F.; Bayes, R.; Beier, E.W.; Bialek, A.; Biller, S.D.; et al. Measurement of neutron-proton capture in the SNO+ water phase. Phys. Rev. C 2020, 102, 014002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Incident–energy event–count distribution (events per logarithmic bin) for secondary cosmic–ray particles interacting with the water Cherenkov detector. Histograms use shared logarithmic binning (60 bins with a 5% margin) and are shown on log–log axes; a Gaussian smoothing curve (with reflective padding and no extrapolation beyond unpopulated bins) is overlaid for visualization only. Legends report the sample means.

Figure 1.

Incident–energy event–count distribution (events per logarithmic bin) for secondary cosmic–ray particles interacting with the water Cherenkov detector. Histograms use shared logarithmic binning (60 bins with a 5% margin) and are shown on log–log axes; a Gaussian smoothing curve (with reflective padding and no extrapolation beyond unpopulated bins) is overlaid for visualization only. Legends report the sample means.

Figure 2.

Zenith–angle event–count distribution (events per bin) for secondary cosmic–ray particles interacting with the water Cherenkov detector, with expressed in degrees. Histograms use shared linear bins (72 bins over –); a Gaussian smoothing curve (with reflective padding and no extrapolation beyond unpopulated bins) is overlaid for visualization only.

Figure 2.

Zenith–angle event–count distribution (events per bin) for secondary cosmic–ray particles interacting with the water Cherenkov detector, with expressed in degrees. Histograms use shared linear bins (72 bins over –); a Gaussian smoothing curve (with reflective padding and no extrapolation beyond unpopulated bins) is overlaid for visualization only.

Figure 3.

Deposited–energy event–count distributions in the WCD: events per logarithmic bin (log–log axes) versus deposited energy (GeV) for secondary muons, electrons, photons, protons, and neutrons. Histograms use shared logarithmic binning across species (60 bins with a 5% margin); a support-aware Gaussian smoothing curve (reflective padding; no extrapolation beyond populated bins) is overlaid for visualization only. Legend entries report the mean deposited energy for each species, and amplitudes reflect the number of events in each energy interval.

Figure 3.

Deposited–energy event–count distributions in the WCD: events per logarithmic bin (log–log axes) versus deposited energy (GeV) for secondary muons, electrons, photons, protons, and neutrons. Histograms use shared logarithmic binning across species (60 bins with a 5% margin); a support-aware Gaussian smoothing curve (reflective padding; no extrapolation beyond populated bins) is overlaid for visualization only. Legend entries report the mean deposited energy for each species, and amplitudes reflect the number of events in each energy interval.

Figure 4.

Cherenkov–photon multiplicity distributions in the WCD: event counts per logarithmic bin (log–log axes) of for secondary muons, electrons, photons, protons, and neutrons (1.90 m water column). Histograms use shared logarithmic binning across species; a support-aware Gaussian smoothing curve (reflective padding; no extrapolation beyond populated bins) is overlaid for visualization only. Legend entries report the mean photon counts , and amplitudes reflect the number of events in each energy interval.

Figure 4.

Cherenkov–photon multiplicity distributions in the WCD: event counts per logarithmic bin (log–log axes) of for secondary muons, electrons, photons, protons, and neutrons (1.90 m water column). Histograms use shared logarithmic binning across species; a support-aware Gaussian smoothing curve (reflective padding; no extrapolation beyond populated bins) is overlaid for visualization only. Legend entries report the mean photon counts , and amplitudes reflect the number of events in each energy interval.

Figure 5.

Cherenkov–photon HitCount at the PMT: event–count distributions (events per logarithmic bin; log–log axes) of for secondary muons, electrons/positrons, photons, protons, and neutrons (1.70 m water column). Histograms use shared logarithmic binning across species; a support-aware Gaussian smoothing (reflective padding; no extrapolation beyond populated bins) is overlaid for visualization only. Legend entries report the mean values ; amplitudes reflect the number of events in each interval.

Figure 5.

Cherenkov–photon HitCount at the PMT: event–count distributions (events per logarithmic bin; log–log axes) of for secondary muons, electrons/positrons, photons, protons, and neutrons (1.70 m water column). Histograms use shared logarithmic binning across species; a support-aware Gaussian smoothing (reflective padding; no extrapolation beyond populated bins) is overlaid for visualization only. Legend entries report the mean values ; amplitudes reflect the number of events in each interval.

Figure 6.

PMT anode charge: event–count distributions (events per logarithmic bin; log–log axes) of Q (pC) for secondary muons, electrons/positrons, photons, protons, and neutrons. Shared logarithmic binning is used across species; a support-aware Gaussian smoothing is overlaid for visualization only. For a representative operating point, pC assuming , gain , and C.

Figure 6.

PMT anode charge: event–count distributions (events per logarithmic bin; log–log axes) of Q (pC) for secondary muons, electrons/positrons, photons, protons, and neutrons. Shared logarithmic binning is used across species; a support-aware Gaussian smoothing is overlaid for visualization only. For a representative operating point, pC assuming , gain , and C.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).