Introduction

Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and Social Impact Assessment (SIA) are critical tools intended to ensure that development actions consider environmental and community well-being (Vanclay Frank 2003; Esteves et al. 2012). However, in many developing countries, these processes frequently fail to achieve their goals due to weak implementation, political expedience, and procedural tokenism (Alam 2018; Kamijo 2022). EIA systems were widely adopted in the Global South from the 1970s onward, yet “their weak implementation has been a major problem” (Kamijo 2022). Public participation, a cornerstone of meaningful EIA/SIA (Morgan 2012), is often treated as a mere formality. In Pakistan, for example, there is no formal legal structure for public participation beyond a single public hearing at the EIA review stage; guidelines on consultation exist but are non-binding, making participation late, limited, and ineffective (Alam 2018). This breeds “token” compliance: officials may technically fulfill minimal requirements (e.g. holding a perfunctory hearing or obtaining a rubber-stamp approval) without genuinely considering stakeholder concerns (Jay et al. 2007). As a result, EIAs and SIAs often do little to alter project outcomes or address public grievances, especially when powerful political or economic interests are at play.

Critically, social impacts, the effects of projects or government actions on communities’ livelihoods, cultural heritage, and social fabric, tend to be sidelined under such conditions. Many developing country EIA laws, including Pakistan’s, primarily focus on biophysical environmental effects and do not explicitly mandate standalone Social Impact Assessments (Alam 2018). Social issues may be glossed over or handled through antiquated frameworks that prioritize state authority over community rights. In Pakistan, the colonial-era Land Acquisition Act of 1894 still governs land takings and provides minimal procedural safeguards for affected people (HRW 2024). This legal gap allows authorities to displace settlements or demolish structures in the name of “public purpose” or “anti-encroachment” drives with little regard for consultation, compensation, or resettlement of those affected (HRW 2024). Human Rights Watch recently documented that in the vast majority of mass eviction cases in Pakistan, authorities failed to provide adequate notice, consult affected communities, or offer resettlement assistance, often using force to remove people (HRW 2024). Such practices reflect an instrumentalization of SIA processes, or their wholesale neglect, to push through actions expediently, at great social cost. In this context, ‘instrumentalization’ refers to the selective use of SIA-related language or artifacts (e.g., citing replacement facilities or clerical consent) to justify actions post hoc, without embedding the principles of inclusive engagement, risk mitigation, or social legitimacy. This rhetorical use of SIA elements, without procedural integrity, constitutes instrumentalization.

Social Impact Assessment has evolved into a critical tool for safeguarding community interests in development and enforcement contexts. While traditionally embedded within Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), modern practice increasingly treats SIA as a standalone process, especially in politically sensitive or socially disruptive actions (Vanclay et al. 2015; Esteves et al. 2012). In Pakistan, SIA remains underdeveloped due to legal gaps and enforcement framing, which allows authorities to bypass consultation and resettlement obligations (Alam 2018; HRW 2024). Comparative studies show that even in the absence of formal EIA triggers, international safeguards mandate inclusive engagement and grievance redress (World Bank 2018b; ADB 2009). This literature underscores the need for proactive SIA in urban governance, particularly where religious, cultural, or livelihood impacts are foreseeable.

This study examines these issues through the lens of the 2025 Madni Mosque demolition in Islamabad, a case that vividly illustrates the consequences of deficient social due diligence. The Madni Mosque case involved the overnight bulldozing of a mosque by authorities on the grounds of land encroachment, sparking public outcry and unrest. This article analyzes how this episode exemplified the failure to adhere to international SIA and stakeholder engagement benchmarks, and how the SIA process was effectively ignored and/or manipulated for expediency. Furthermore, this research situates the case within Pakistan’s legal and policy framework, specifically the Pakistan Environmental Protection Act 1997 and the 2000 EIA Review Regulations, to evaluate why procedural safeguards fell short. In the discussion, we compare the Madni Mosque incident to other Pakistani cases of enforcement-driven displacement and land clearance (such as forced evictions of informal settlements), highlighting a pattern of compromised social due process. This article contributes to the scholarly discourse on impact assessment by analyzing how enforcement framing in Pakistan’s urban governance enables the systematic bypassing of Social Impact Assessment. Through a case-based audit against international standards, it offers conceptual insights and policy recommendations relevant to both domestic reform and global IA practice.

Methodology

In Pakistan’s regulatory context, ‘projects’ are defined as planned development activities subject to screening under PEPA 1997 and EIA Regulations 2000. In contrast, ‘enforcement actions’, such as demolitions or evictions, are framed as administrative or legal operations, not requiring environmental review. This framing allows authorities to bypass SIA obligations, even when social impacts are significant. The paper interrogates this dichotomy and its implications for procedural justice. This study uses a comparative case study design to interrogate how social dimensions of impact assessment are addressed, or strategically avoided, when state actions are framed as “enforcement” rather than “projects” in Pakistan. The primary case is the August 2025 demolition of Madni (Madani) Mosque in Islamabad; it was selected because it combines a high-salience religious space with an executive narrative that no formal environmental review was required, yet it produced clear social consequences (community unrest, counter-mobilization, and after-the-fact government clarification). To test the generalizability of mechanisms observed in this case, we analyze two comparative cases that share the “enforcement-not-project” framing but involve different populations and scales: the 2015 clearance of the I-11 informal settlement in Islamabad and the 2020–21 Karachi nullah (storm-drain) evictions. These comparators were purposefully chosen because they fall outside routine EIA triggers under the Pakistan Environmental Protection Act, 1997 (PEPA) and the federal IEE/EIA Review Regulations, 2000, yet involved large, predictable social impacts.

Data was assembled from three streams. First, a contemporaneous press corpus for the mosque case was built from national newspapers of record (e.g., Dawn, Daily Times), capturing event timing, state justifications, and counterclaims from religious groups across 9–16 August 2025. We triangulated reports on the night-time demolition, subsequent protests, and the state’s assertion of prior consent and relocation (including the claim that a new mosque/seminary in Margalla Town had been completed pre-demolition). Where possible we cross-checked syndicated and mirrored versions of official statements to reduce the risk of single-outlet bias (DailyTimes 2025). Second, for comparative cases, we drew on Human Rights Watch’s 2024 investigative report and accompanying news release, which document Pakistan’s recurrent mass evictions, short or absent notice, lack of resettlement, and denial of redress, elements directly pertinent to SIA adequacy. These sources were complemented by policy/academic analyses of Pakistan’s consultation practice and regulatory gaps (HRW 2024). Third, legal and regulatory texts (PEPA 1997; IEE/EIA Review Regulations 2000) were used to identify what the law does—and does not, mandate regarding screening thresholds and public participation (noting that public hearing duties attach to EIA review, typically late in the process). We used WWF-Pakistan’s situational analysis to contextualize persistent implementation deficits and the absence of explicit, standalone SIA requirements (PEPA 2000).

Our analytical framework operationalizes international benchmarks into verifiable indicators. It is important to clarify that no formal SIA was conducted for the Madni Mosque case. The term ‘SIA adequacy’ here refers to a retrospective audit of de facto practices against international standards, not an evaluation of an existing SIA report. This framework is adapted from Vanclay et al. (2015) and Imperiale & Vanclay (2023), emphasizing community resilience, procedural integrity, and participatory governance. It allows structured audit of social due diligence across seven stages, even in contexts where formal EIA/SIA documentation is absent. We adopted the World Bank’s Environmental and Social Framework (ESS10) on stakeholder engagement and information disclosure, the IFC Good Practice Handbook on stakeholder engagement, and the Asian Development Bank’s Safeguard Policy Statement (SPS) for involuntary resettlement and consultation. In parallel, we used the International Association for Impact Assessment (IAIA) guidance and principles to ground the SIA-specific expectations (e.g., early scoping with communities, attention to cultural values, and the requirement that SIA be a process, not just a report) (Vanclay Frank 2003; Vanclay Francis et al. 2015). These sources were chosen because they synthesize state-of-practice norms used by MDBs and practitioners globally and provide auditable criteria applicable even when domestic law is silent (World Bank 2018b).

We then translated benchmarks into a seven-stage audit schema against which each case was coded: (1) screening/scoping (evidence of early identification of social risk; proportionality of assessment); (2) baseline and impact identification (documentation of affected groups, cultural significance, and livelihood linkages); (3) disclosure and consultation (timing, inclusivity, language/accessibility, record of meetings); (4) alternatives analysis (consideration of avoidance/minimization, including “no action” or in-situ options); (5) resettlement/livelihood restoration (existence and adequacy of plans and entitlements); (6) grievance redress (existence, accessibility, responsiveness of GRM); and (7) monitoring/follow-up (post-action verification and adaptive management). Decision rules for each stage were specified ex-ante from the benchmarks; for example, ESS10 requires early, ongoing consultation proportionate to risk, a Stakeholder Engagement Plan, and a functioning GRM; IFC details inclusive modalities and record-keeping; and ADB SPS obliges consultation free of coercion and, where displacement occurs, structured resettlement planning and livelihood restoration. A stage was coded “fulfilled” if at least two independent sources corroborated compliance with the benchmarked requirement (e.g., a disclosed Stakeholder Engagement Plan with meeting logs and a GRM notice); “partially fulfilled” if some but not all elements were evidenced (e.g., engagement limited to a single institutional actor rather than the broader public); and “not fulfilled” if no credible evidence of the benchmarked element was found (Asian Development Bank 2009).

To enhance validity, we employed source triangulation and a “dual corroboration” standard for positive findings. For the mosque case, we weighed state claims (lawful relocation with consent; alternative facility built and occupied) against independent contemporaneous reporting on protests, symbolic rebuilding, and criminal complaints, treating concordance across ideologically diverse outlets as higher-probative. Where discrepancies persisted (e.g., scope of “consent” vis-à-vis broader worshipper community), we coded conservatively as partial or not fulfilled and flagged the ambiguity in narrative synthesis. For the comparative cases, we treated the HRW 2024 investigation (which documents lack of notice, consultation, compensation, and resettlement across operations in Karachi and Islamabad) as an external validity anchor, cross-checking with Pakistani press where available (HRW 2024).

Scope conditions and limitations were explicitly recognized. Because the actions studied were not registered as “projects,” there are no publicly available EIAs/SIAs to quality-appraise; accordingly, our approach evaluates de-facto practice against de-jure domestic requirements and de-facto international norms. Pakistani EIA law ties public participation primarily to the EIA review stage and offers limited, late, or discretionary mechanisms for earlier engagement, which both rationalizes and obscures omissions in enforcement settings; this institutional feature shaped our interpretation of “fulfilment” at the consultation stage. We also note reliance on documentary sources rather than human subjects; however, the corpus includes government statements, independent press, and international investigations sufficient to apply the benchmark schema transparently and replicably (Pope et al. 2013). Finally, because IA practice is context-dependent, we anchored expectations to widely used guidance (ESS10/IFC/ADB and IAIA) precisely to avoid anachronistic or jurisdiction-specific bias (Pope et al. 2013; Khawaja and Nabeela 2014).

Table 1.

Audit codebook – indicators and decision rules.

Table 1.

Audit codebook – indicators and decision rules.

| Stage |

Indicator |

Fulfilled (Evidence Required) |

Partial |

Not Evidenced |

| Screening & scoping |

Early identification of social risk; proportionality of assessment |

Dated record of scoping/ToR mentioning social risk; early public notice |

Limited/late internal scoping only |

No trace of scoping or social risk identification |

| Baseline & impact ID |

Stakeholder mapping; cultural/ritual value; livelihoods |

Baseline or SEP listing stakeholder groups; cultural valuation; methods noted |

Fragmentary baseline; narrow stakeholder list |

No baseline, no mapping |

| Consultation & disclosure |

Timing; inclusivity; record; access |

SEP + minutes/attendance; materials in local language |

Engagement with a single gatekeeper (e.g., administrators) |

No record; post-hoc justifications only |

| Alternatives analysis |

Avoid/minimize; “no action”; ritual/continuity options |

Options analysis with rationale |

One option noted without reasons |

No public record of alternatives |

| Resettlement / livelihood |

RAP/entitlements; continuity |

RAP published; livelihood plan, timelines |

Physical replacement only or cash stipends |

None |

| Grievance redress |

GRM established, accessible, responsive |

Notice with channels; log of cases/resolution |

Informal channels only |

None |

| Monitoring & follow-up |

Social outcomes tracked; adaptive actions |

Disclosed monitoring report(s) |

Ad-hoc updates/no indicators |

None |

Case Analysis/Discussion

The Madni Mosque Demolition Case: Events and Analysis

The mosque was reportedly constructed in the early 2000s, though exact records are unavailable. Its location on a greenbelt suggests it may have lacked formal planning approval, a common occurrence in informal religious and residential structures in Pakistan’s urban peripheries. The demolition in Islamabad took place in early August 2025 as part of a municipal drive to clear encroachments on public land. The mosque, along with an adjacent madrassa (religious seminary), was located on a greenbelt area alongside a main road (Murree Road near Rawal Dam Chowk) (Ali 2025). Viewing it as an unauthorized structure violating city zoning laws, the Capital Development Authority (CDA) and Islamabad Capital Administration decided to remove the mosque. Late on a Saturday night, bulldozers and police moved in to demolish the building, reportedly after ensuring the site was empty of people. By morning, the structure was razed and saplings were planted in its place as part of the “beautification” of the greenbelt (Dawn 2025). Crucially, there is no public record of prior disclosure, a stakeholder engagement plan (SEP), or a grievance mechanism, all of which would ordinarily evidence due process. This sequencing — decision → demolition → ex post landscaping — reverses the standard order envisaged by S/EIA.

Table 2.

Chronological timeline of the Madni Mosque demolition (Islamabad, August 2025).

Table 2.

Chronological timeline of the Madni Mosque demolition (Islamabad, August 2025).

| Date (2025) |

Event (observed) |

Government statement / claim (if any) |

Notes relevant to SIA/Social risk |

Source |

| Aug 8–9 (Fri–Sat night) |

Mosque demolished overnight on greenbelt; saplings planted by morning

|

— |

Action precedes any documented public engagement; high conflict sensitivity overlooked |

Dawn report Aug 11 (news + ePaper) |

| Aug 10 (Sun) |

Worshippers pray at site; saplings uprooted

|

— |

Immediate community backlash → strong indicator of social license gap

|

Dawn ePaper Aug 12 |

| Aug 11 (Mon) |

Protests by multiple religious groups; negotiations announced |

— |

Escalation within 24–48h → an ex-ante SIA would have flagged this risk |

Dawn Aug 12 (news + ePaper) |

| Aug 12–13 (Tue–Wed) |

— |

Minister says consent was obtained; months-long process; replacement built (≈PKRs 40m; students relocated) |

Post-hoc narrative; does not substitute for early, inclusive consultation |

Dawn Aug 13; APP Aug 13 |

| Aug 15 (Fri) |

Large Friday gathering; groups begin reconstruction at site |

— |

Demonstrates absence of social buy-in; law-and-order risk materializes |

Dawn Aug 16 |

The timing and manner of the demolition prompted immediate public concern and mobilization by religious groups. Public demonstrations were organized by religious political parties in response to the demolition such as Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI-F) (Kamijo 2022). Protesters gathered at the demolition site for several days, denouncing the government’s action as an assault on Islam. They symbolically rebuilt portions of the mosque with collected debris during a mass prayer gathering (Dawn 2025). Religious leaders publicly expressed their intent to reconstruct the mosque independently, citing dissatisfaction with the government's approach. The controversy intensified, with some groups filing legal complaints alleging religious desecration; multiple police complaints were lodged seeking to charge the Interior Minister and CDA officials for “desecration” of a place of worship (Dawn 2025). This reflects the intense social impact of the demolition, touching a deep religious nerve in a conservative society. Analytically, the rapid escalation from localized gatherings to city-wide mobilization within 24–48 hours is a classic marker of high conflict sensitivity that a routine SIA would flag at scoping.

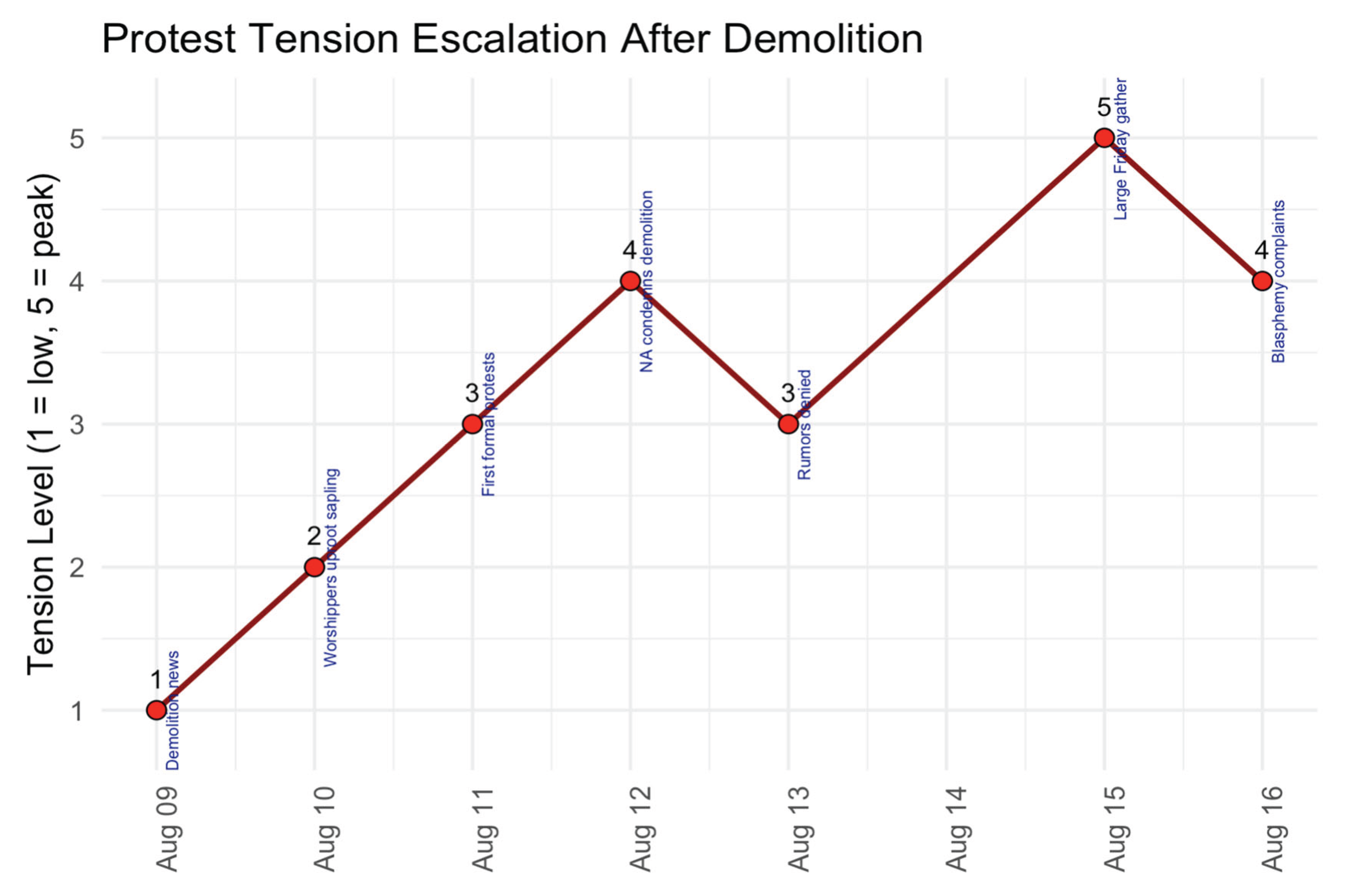

Figure 1.

Protest tension escalation after the Madni Mosque demolition (Islamabad, August 9–16, 2025). Figure was generated by synthesizing event chronology from press reports (Dawn, Daily Times) between August 9–16, 2025, mapping escalation phases and stakeholder responses.

Figure 1.

Protest tension escalation after the Madni Mosque demolition (Islamabad, August 9–16, 2025). Figure was generated by synthesizing event chronology from press reports (Dawn, Daily Times) between August 9–16, 2025, mapping escalation phases and stakeholder responses.

In response, Government officials subsequently issued statements to clarify the rationale and legality of the demolition. Officials asserted that the relocation was carried out lawfully and with sensitivity. According to the Minister of State for Interior, “the demolition of the mosque and its adjoining seminary was carried out strictly per law, Islamic principles and with the consent of the mosque administration” (DailyTimes 2025). The authorities claimed they had given the mosque administrators two months’ prior notice and even constructed a modern new mosque and seminary in a different locality (Margalla Town) for Rs 40 million, “ensuring no one was present at the old site during demolition.” (DailyTimes 2025). They cited Islamic precedents to legitimize mosque relocation; for instance, invoking the Prophet’s order to remove an improperly built mosque (Masjid Dirar) in early Islamic history, and Quranic verses against unjust occupation of land (DailyTimes 2025). The Interior Ministry stressed that Islam permits relocation of mosques when done for the public good and with proper alternatives provided (DailyTimes 2025). Officials also insisted that any future removals of mosques from unauthorized sites would be done in consultation with religious scholars and with the administration “on board.” (DailyTimes 2025). However, these assertions are not accompanied by documentary artifacts typically used to verify due process (e.g., a dated written consent, minutes of meetings, a publicly disclosed SEP/GRM, or a relocation MoU); in their absence, “consent” remains unverified and narrowly construed. As used here, consent appears transactional and limited to custodians, rather than “broad-based community support, as required under international standards such as ESS10 and IFC Performance Standards” in the ESS10/IFC sense that requires inclusion of broader affected stakeholders.

Despite these assurances, a critical examination reveals that the SIA process was largely neglected and partially “instrumentalized” in the Madni Mosque affair (Vanclay Frank 2003; Esteves et al. 2012). The government’s narrative of having secured “consent” and provided a ready alternative was used as an ex post facto rationalization to blunt criticism, rather than as part of a genuine participatory planning process. By all accounts, the decision to demolish had already been made by authorities well before any outreach. The mosque’s caretakers may have been pressured into agreement, facing an illegal status, they had limited bargaining power. Broader stakeholders (local worshippers, neighboring communities, and the wider Islamic fraternity in Islamabad) were not engaged in advance. The first many learned of the plan was after the fact, through the shocking news that a house of worship had been torn down overnight. This lack of transparent, inclusive engagement violated the spirit of international standards like WB ESS10 and the IFC guidelines, which call for open dialogue throughout project planning (World Bank 2018a). This omission also illustrates what Cashmore (2004) terms a failure of substantive effectiveness: although the formal rationale emphasized legality, the process did not achieve the deeper objective of securing social legitimacy. Instead, authorities treated the matter as a confidential enforcement operation, likely to avoid mobilizing opposition, a political expedience that backfired by causing outrage when the secretive action came to light. In short, selective engagement of custodians functioned as “elite brokerage,” not community consultation; the sequence indicates narrative management rather than risk management. The limited evidence of a replacement facility signals partial compliance on resettlement infrastructure, but not on social continuity or ritual transition.

Had a proper Social Impact Assessment or stakeholder consultation been undertaken, it would have identified the mosque’s significance to the community and the high risk of backlash. An SIA might have recommended alternative approaches: for example, negotiating a relocation plan with the community’s buy-in, publicly announcing and explaining the move well in advance, perhaps even performing religious rites to officially transfer the mosque’s status to the new site before demolition. These steps could have preserved public trust and a sense of respect. Instead, the sequence of events—demolition followed by post hoc justification—contributed to perceptions of procedural opacity and disregard for community sentiment. The token elements of SIA that were present were instrumentalized mainly for narrative control: the new replacement building was highlighted to show “no harm” was done, and the claim of clerics’ consent was repeatedly emphasized as proof of consultation (DailyTimes 2025). Yet, this narrowly defined consent (limited to the seminary’s head) does not equate to broad community acceptance or participatory decision-making. In essence, the government used the veneer of SIA (replacement facility, selective consultation) to legitimize an action that otherwise followed the typical pattern of a forced eviction or clearance. Counterfactually, a sequenced plan — public notice → clerical council mediation → ritual translocation → activation of the new site prior to closure — would likely have reduced conflict probability and reputational risk. This pattern aligns with critiques in Vanclay (2020) and Ijabadeniyi & Vanclay (2020), who highlight how procedural references and technical language in ESIA can obscure substantive harm and marginalize affected communities (Cashmore 2004; Bond et al. 2018). According to the IAIA Principles of SIA, effectiveness requires early integration, inclusivity, and influence on decision-making. None of these were evidenced here, highlighting a gap between formal compliance claims and substantive practice.

From a legal standpoint, the Madni Mosque case also exposes ambiguities and gaps in Pakistan’s environmental and social protection framework. Formally, the Pakistan Environmental Protection Act (PEPA) 1997 and the accompanying IEE/EIA Review Regulations (2000) require that any project likely to have an “adverse environmental effect” must undergo an Initial Environmental Examination or full EIA, including at least one public hearing for the latter (Government of Pakistan 1997; Alam 2018). However, what constitutes a “project” and an “adverse environmental effect” is key. One could argue that an operation to demolish a longstanding public mosque and alter land use has significant social and environmental ramifications, community unrest, loss of cultural heritage, changes in land cover (greenbelt restoration), thus should have triggered an assessment. In practice, though, authorities treated it not as a development project but as an enforcement action, thereby sidestepping environmental review processes entirely. However, international best practice recognizes that actions with significant social consequences, such as demolitions of religious or residential structures, warrant proportionate SIA, even if not legally classified as ‘projects.’ The World Bank’s ESS10 and IFC Performance Standards require stakeholder engagement and grievance mechanisms in any activity with foreseeable social risks, regardless of formal EIA triggers (World Bank 2018b; Imperiale & Vanclay 2023). Pakistan’s EIA regulations list types of projects that require EIA (large infrastructure, industrial plants, etc.), but a one-off demolition for land clearance is not explicitly covered (Nadeem and Fischer 2011). This loophole meant the CDA could lawfully proceed without any EIA or SIA, despite the profound social impact. The law’s focus on physical environmental impact and its project-based definitions left social considerations in such enforcement scenarios unregulated. As noted in one analysis, Pakistani EIA laws “do not specifically cater to Social Impact Assessments,” being primarily geared toward biophysical factors (Alam 2018). Public consultation is only mandated during the EIA review stage and not at all for smaller undertakings (Alam 2018). Thus, if an action is not formally categorized as a project requiring EIA, the law imposes no duty to consult or compensate affected communities. This regulatory gap was evident in the Madni Mosque saga; the authorities were not legally compelled to hold a public hearing or prepare an impact report, and they did not. The outcome demonstrates how even a legally “compliant” operation (in terms of domestic law) can fail the test of social legitimacy and sustainability when broader stakeholder engagement is neglected. This constitutes a form of regulatory arbitrage: by classifying the act as “enforcement,” the state avoided triggers that would otherwise have mandated disclosure, hearing, and conditions of approval (Bond et al. 2018). Doctrinally, the social consequences meet “significance” thresholds even where biophysical impacts are modest, underscoring a design flaw in PEPA and its rules. Conceptually, this illustrates the classic distinction between “procedural effectiveness” (whether legal steps exist) and “substantive effectiveness” (whether impacts are actually mitigated) often applied in IA literature (Cashmore 2004). While Pakistan’s EIA framework provided procedural cover, substantive outcomes — community trust, conflict avoidance, cultural continuity — were absent, underscoring the weakness of formalistic compliance in fragile governance contexts.

Enforcement Framing and SIA Avoidance: Comparative Patterns in Urban Governance

While the Madni Mosque case is central, similar enforcement-driven actions in Pakistan reveal a broader pattern of SIA avoidance. These comparisons help situate the case within systemic governance dynamics. The incident therefore is not an isolated case; it reflects a broader pattern of compromised social due process in Pakistan during enforcement, displacement, or land-clearance operations. In numerous instances, development projects or anti-encroachment drives have proceeded with little-to-no attention to SIA, leading to human rights violations, social tensions, and protracted conflicts (

Table 1). The term ‘encroachment’ is often used by authorities to justify clearance of informal or unauthorized structures. However, this framing obscures the socio-legal complexity of land tenure, religious use, and community claims. Scholars argue that encroachment is not merely a legal violation but a contested concept shaped by governance failures, urban inequality, and planning exclusion (Andreasen et al., 2022). Two instructive comparisons are the mass eviction of the I-11

Katchi Abadi (informal settlement) in Islamabad in 2015 and the clearance of thousands of homes along Karachi’s stormwater drains (nullahs) in 2020-21. These cases, like Madni Mosque, highlight how formal legal justifications (illegality of structures, public interest objectives) are often pursued through summary actions that override community participation and social safeguards. Across cases, the mechanism is consistent: weak or absent duty → compressed timelines → force-first implementation → ex post justification → rights-claiming and unrest. Where partial remedies existed (e.g., limited cash in Karachi), they were non-restorative and lacked livelihood linkage.

In July 2015, Islamabad’s I-11 informal urban settlement (locally known as “Afghan Basti”) was bulldozed in a large-scale operation. Approximately 15,000 people, mostly low-income Pashtun families, were evicted from land they had lived on for decades (Ahmad 2002). The authorities (CDA, police, and paramilitary Rangers) served only a one-week eviction notice before mobilizing force. When residents refused to leave, citing lack of alternative shelter, the state deployed hundreds of personnel to cordon off the area and systematically demolish homes with excavators (Ahmad 2002). Many inhabitants escaped with just their basic possessions; some who resisted were beaten or arrested (Ahmad 2002). No resettlement plan was offered; the residents were simply deemed encroachers on state land and thus undeserving of compensation. This approach blatantly disregarded any notion of SIA or stakeholder engagement. The eviction destroyed not just physical structures but livelihoods and community networks, leaving evictees in a humanitarian crisis (Cernea 2000; Fernandes 2008). From a conceptual IA lens, this case highlights procedural effectiveness was absent (Bond et al. 2018), as no scoping or consultation mechanisms were applied, leading to predictable substantive failures in social outcomes. Subsequent investigations by human rights organizations concluded that the eviction violated multiple rights (housing, due process, etc.) and failed to meet international standards for evictions (HRW 2024). For instance, advance consultation was absent; people were not meaningfully informed or consulted about less harmful alternatives. International law (e.g. UN guidelines on evictions) requires exploring all feasible alternatives and genuine consultation before displacement, but Pakistani law’s silence on such requirements enabled the blunt use of force (HRW 2024). The I-11 case led to court petitions and public criticism, yet it set a precedent for similar anti-encroachment actions in the years to follow, with the underlying social issues unresolved. Analytically, I-11 represents “zero-option” decision-making: no alternatives, no entitlements, no GRM—an archetype of SIA avoidance under an enforcement framing.

Fast forward to Karachi in 2020-2021, where authorities undertook mass demolitions of houses built along the Gujjar and Orangi Nullahs (stormwater channels) after catastrophic urban floods. Framing the informal riverside settlements as the cause of drainage blockage, the city, on court orders, cleared a wide swath of working-class neighbourhoods. Over 20,000 homes were estimated to be demolished, displacing around 100,000 people. Again, the pattern repeated: minimal consultation, perfunctory notices, and inadequate rehabilitation. Many affected families had nowhere to go; some received meagre monetary compensation that did not cover the cost of new housing. Activists argue that “preventing flooding was used as an excuse to gentrify the area”; the land cleared is prime urban real estate [46]. Regardless of intent, the social outcome was thousands of homeless people, whose plight was largely ignored in the pursuit of an infrastructure objective (Patel and Baptist 2012; Satterthwaite and Mitlin 2013). A Human Rights Watch report on these evictions noted that they “worsen social and economic inequalities, disproportionately burdening low-income and minority households” (HRW 2024). In other words, the absence of SIA in planning perpetuates environmental injustices: vulnerable groups bear the brunt of both environmental hazards and the impacts of mitigation projects. Notably, even after these harsh measures, Karachi continues to experience flooding highlighting that evicting the poor is not a cure-all, and a more holistic, consultative approach to urban resilience was needed (HWR 2024). The persistence of flooding despite mass displacement underscores Vanclay’s (2020) critique of SIA “instrumentalization”: impact assessment language is invoked to justify interventions, but the processes are detached from their purpose of risk reduction. The courts in Pakistan, which ordered or green-lit many such anti-encroachment drives, have been criticized for ignoring the social dimensions and treating the issue purely as one of legality of tenure. There is a nascent recognition (as seen in some Pakistani court judgments on housing rights) that due process and rehabilitation are part of the right to life, but this principle is yet to be consistently applied in practice (Alam 2018; HRW 2024). Karachi thus demonstrates the limits of “infrastructure-first” approaches: biophysical risk reduction cannot be sustained if it manufactures social vulnerability downstream.

Across these cases – the mosque demolition, the slum clearance, the flood evictions – a common thread is the instrumental use of law and process to expedite objectives at the expense of public participation (Sánchez and Mitchell 2017; Bond et al. 2018). Environmental and planning laws are invoked to justify action (be it restoring a greenbelt or removing encroachments for public safety), but social impact processes are either bypassed or reduced to a checkbox. Public hearings, where they occur, often happen after key decisions are made, and affected communities’ input seldom influences outcomes (Nadeem 2010; O'Faircheallaigh 2010). This tokenism erodes trust in authorities and can lead to conflict, as seen in the Madni Mosque case where excluded stakeholders resorted to protest and even violence. Seen through IA theory, this represents a collapse across all four quality dimensions: procedural (steps omitted), substantive (outcomes worsened), transactive (inefficient use of resources), and normative (erosion of justice and equity) (Bond et al. 2018). The failure to integrate SIA also means missed opportunities for better solutions. With genuine engagement, creative compromises could emerge; for example, in Islamabad’s Mosque case, stakeholders might have agreed on relocating the structure in a ceremonious, acceptable manner; in Karachi’s flood areas, upgrading settlements in-place with community cooperation might have been preferable to wholesale demolition. Empirically, what fails is not merely procedure but problem-solving capacity: exclusion forecloses lower-cost, lower-conflict options that SIA typically surfaces.

Table 3.

Graded procedural compliance matrix for the Madni Mosque demolition.

Table 3.

Graded procedural compliance matrix for the Madni Mosque demolition.

| S/EIA step (aligned to WB ESS10 / IFC / ADB) |

Madni Mosque (Islamabad, 2025) |

I-11 Eviction (Islamabad, 2015) |

Karachi Nullahs (2020–21) |

Adopted Strategy |

| Screening & scoping |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

No public scoping artifacts in press/official record for all three. |

| Baseline social data / stakeholder mapping |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

No SEP/baseline disclosed (Madni); I-11 demolitions proceeded as enforcement; Karachi evictions criticized for lack of enumeration & inclusion. |

| Ex-ante social risk analysis |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

No evidence of risk analysis prior to action in press/NGO documentation. |

| Alternatives analysis (avoid/minimize) |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

No public record of alternatives (e.g., ritual relocation/in-situ solutions; upgrading/phasing for Karachi). |

| Consultation & disclosure |

◐ (limited to administrators)

|

✖ |

✖ |

Madni: minister’s claim of “consent” contrasted with broad protests

I-11: enforcement operations with clashes;

Karachi: UN OHCHR cites lack of consultation. |

| Resettlement / compensation |

◐ (replacement facility)

|

✖ |

◐ (rent/cash stipends, uneven)

|

Madni: replacement reported;

I-11: none reported in contemporaneous press;

Karachi: rent support ordered by SC but uneven/delayed |

| Grievance redress mechanism (GRM) |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

No formal GRM disclosed; grievances expressed via protests/courts/CSOs. Madni: Friday rebuild;

I-11: clashes;

Karachi: UN/HRW criticism. |

| Monitoring & follow-up (social) |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

No publicly available monitoring of social outcomes found. |

| Legal framing / trigger |

— (enforcement)

|

— (enforcement)

|

— (judicial clearance)

|

Framed to avoid EIA triggers (press/judicial framing).

Madni & I-11: enforcement;

Karachi: SC-driven clearance; rent support ordered later. |

Theoretically, these cases resonate with critics that IA in the Global South is trapped in a “thin” model, where reports and notices substitute for genuine social engagement. Integrating global best practice requires shifting toward “thick” IA; embedding deliberation, grievance mechanisms, and adaptive monitoring into core decision processes. It is instructive to compare Pakistan’s situation with experiences elsewhere. Many developing countries face similar struggles in operationalizing SIA. Studies have found that political will is a decisive factor; in places where governments see public participation as a threat or delay, they tend to keep it superficial (Chen 2013). Moreover, weak institutional capacity and lack of enforceable guidelines result in EIA/SIA reports of poor quality that decision-makers largely ignore (Nadeem and Fischer 2011). Pakistan typifies these challenges: while it has the legal trappings of environmental assessment, the practice often devolves into a pro-forma exercise, or is sidestepped entirely for politically sensitive undertakings. The Madni Mosque case also underlines an important point: even where an EIA is not legally required, there may be significant social impacts. Modern policy thinking advocates the use of “strategic” or ad-hoc SIA for policies or actions that affect communities, even if not full projects; for instance, urban renewal programs, slum clearance operations, or heritage site decisions. In Pakistan, such mechanisms are missing. Social impact considerations remain largely reactive (dealt with through crisis management once public backlash occurs) rather than proactive (planned for in advance). This article’s contribution is to identify “enforcement framing” as a predictable pathway to SIA avoidance and to specify the institutional fixes (trigger rules, SEP/GRM requirements, resettlement policy) that would close it.

Encouragingly, there are signs of change. Pakistani civil society and academia have been calling for stronger social safeguards. Some have proposed updating laws to explicitly require SIA and resettlement planning in a range of scenarios (Alam 2018). A draft National Resettlement and Rehabilitation Policy has existed since 2002 but awaits formal adoption (Alam 2018). If implemented, it could fill some gaps by mandating rehabilitation for people displaced by government projects, even when land acquisition is not via formal purchase. Additionally, Pakistan’s higher courts in a few cases have recognized housing and livelihood as rights; for example, the Supreme Court in 2015 (Dr. Imrana Tiwana case) emphasized that environmental regulators must uphold “social justice” and that unchecked development violates citizens’ rights (Alam 2018). In principle, these judgments support the argument that authorities have to weigh social impacts and involve the public, even if statutes are silent on the matter. The challenge is translating these judicial dicta and policy proposals into everyday administrative practice. Taken together, the evidence supports a graded conclusion: partial compliance (physical replacement facility) alongside systemic non-fulfilment of core SIA functions (baseline, alternatives, GRM, monitoring). For practitioners, the operational lesson is straightforward: the absence of a legal trigger does not erase social risk; it merely shifts it into the realm of public order and legitimacy.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The demolition of Islamabad’s Madni Mosque illustrates how weak legal mandates for social assessment, tokenistic consultation, and absent grievance mechanisms can quickly escalate routine planning actions into crises of legitimacy. Authorities relied on narrow procedural claims of consent, but failure to account for broader community voices exposed a gap between legal form and social acceptance. For Pakistan, several reforms are essential. Environmental and planning laws should be updated to explicitly include social and cultural impacts, so that assessments cover livelihoods, displacement, and heritage alongside environmental effects. A resettlement policy must be finalized and enforced, requiring Social Management or Resettlement Action Plans before any clearance or eviction. Public engagement processes must be strengthened, moving from late-stage notice toward meaningful participation that includes marginalized groups and provides clear responses to public input. Grievance redress and monitoring should be institutionalized, ensuring affected people have accessible channels to raise concerns and that independent oversight is routine. Stronger accountability through tribunals, courts, and internal performance measures can help shift bureaucratic incentives toward cooperative rather than coercive approaches. For international practitioners, the broader lesson is that the absence of formal triggers does not remove social risk. On the contrary, neglecting proportionate SIA processes undermines legitimacy, provokes conflict, and reduces development effectiveness. Embedding SIA as both a legal requirement and a professional norm is critical to ensuring that development is not only environmentally sound but also socially sustainable. This study’s findings confirm that enforcement framing in Pakistan’s urban governance enables systematic avoidance of SIA, even when social impacts are significant. By comparing the Madni Mosque case with other eviction scenarios, we demonstrate the need for legal reforms that embed mandatory SIA triggers, inclusive engagement protocols, and grievance redress mechanisms.

References

- Ahmad, N. 2002. Excluding the Poor: The Price of Inequality. Pakistan Development Review (PDR), Papers and Proceedings. 1:61-76.

- Alam, AR. 2018. Situational Analysis of National Environmental Laws and Policies, Non-Compliance of these Laws, Resource Efficiency Issues and Gaps in Implementation, and Enforcement. Pakistan: World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF).

- Ali, K. 2025 August 12. Protests erupt against razing of mosque in Islamabad. https://www.dawn.com/news/1930260.

- Andreasen, M.H. , et al. (2022). Urban encroachment in ecologically sensitive areas: drivers, impediments and consequences. Buildings & Cities, 3(1), 920–938. [CrossRef]

- Asian Development Bank. 2009. Safeguard Policy Statement.

- Policy Paper. Manila, Philippines: Asian Development Bank (ADB).

- World Bank. 2018a. Environmental and Social Framework: Environmental and Social Standards (including ESS10: Stakeholder Engagement and Information Disclosure). World Bank.

- World Bank. 2018b. ESF Guidance Note 10: Stakeholder Engagement and Information Disclosure. Washington, D.C. World Bank. 2018b. ESF Guidance Note 10: Stakeholder Engagement and Information Disclosure. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

- Bond A, Retief F, Cave B, Fundingsland M, Duinker P, Verheem R, Brown A. 2018. A contribution to the conceptualisation of quality in impact assessment. Environmental Impact Assessment Review. 68:49-58.

- Cashmore, M. 2004. The role of science in environmental impact assessment: process and procedure versus purpose in the development of theory. Environmental Impact Assessment Review. 24(4):403-426.

- Cernea, MM. 2000. Risks, safeguards and reconstruction: A model for population displacement and resettlement. Economic and Political Weekly. 3659–3678.

- Chen, J. 2013. Public participation provisions in Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) legal system-Case studies in China, India and Indonesia.

- DailyTimes. 2025 Capital mosque relocated lawfully, propaganda baseless: authorities. Daily Times. https://dailytimes.com.pk/1351685/capital-mosque-relocated-lawfully-propaganda-baseless-authorities/.

- Dawn. 2025 Religious groups begin construction of demolished mosque on capital’s Murree Road. https://www.dawn.com/news/1931113.

- Esteves AM, Franks D, Vanclay F. 2012. Social impact assessment: the state of the art. Impact assessment and project appraisal. 30(1):34-42.

- Fernandes, W. 2008. India’s forced displacement policy and practice: Is compensation up to its functions. Can compensation prevent impoverishment.181-207.

- Government of Pakistan. 1997. Pakistan Environmental Protection Act, 1997 (PEPA 1997). Islamabad, Pakistan: Government of Pakistan.

- Ijabadeniyi, A. & Vanclay, F. (2020). Socially-tolerated practices in Environmental and Social Impact Assessment reporting: Discourses, displacement, and impoverishment. Land, 9(2), 33. [CrossRef]

- Imperiale, A. , & Vanclay, F. (2023). Re-designing Social Impact Assessment to enhance community resilience. Sustainable Development, 31(1), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Jay S, Jones C, Slinn P, Wood C. 2007. Environmental impact assessment: Retrospect and prospect. Environmental impact assessment review. 27(4):287-300.

- Kamijo, T. 2022. How to enhance EIA systems in developing countries: a quantitative literature review. Environment, Development and Sustainability. 24(12):13476-13492.

- Khawaja SA, Nabeela NJ. 2014. Review of IEE and EIA Regulations 2000. Islamabad: IUCN Pakistan.

- Morgan, RK. 2012. Environmental impact assessment: the state of the art. Impact assessment and project appraisal. 30(1):5-14.

- Nadeem, O. 2010. Public participation in environmental impact assessment of development projects in Punjab, Pakistan. UNIVERSITY OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY LAHORE–PAKISTAN.

- Nadeem O, Fischer TB. 2011. An evaluation framework for effective public participation in EIA in Pakistan. Environmental Impact Assessment Review. 31(1):36-47.

- O'Faircheallaigh, C. 2010. Public participation and environmental impact assessment: Purposes, implications, and lessons for public policy making. Environmental impact assessment review. 30(1):19-27.

- Pakistan Environmental Protection Agency. 2000. Initial Environmental Examination (IEE) and Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Regulations, 2000. Legal Regulation ed. Lahore, Pakistan: Government of Punjab, Environment Protection Department.

- Patel S, Baptist C. 2012. Documenting by the undocumented. SAGE Publications Sage UK: London, England. p. 3-12.

- Pope J, Bond A, Morrison-Saunders A, Retief F. 2013. Advancing the theory and practice of impact assessment: Setting the research agenda. Environmental impact assessment review. 41:1-9.

- Sánchez LE, Mitchell R. 2017. Conceptualizing impact assessment as a learning process. Environmental Impact Assessment Review. 62:195-204.

- Satterthwaite D, Mitlin D. 2013. Reducing urban poverty in the global south. Routledge.

- Vanclay, F. 2003. International principles for social impact assessment. Impact assessment and project appraisal. 21(1):5-12.

- Vanclay, F. , Esteves, A.M., Aucamp, I., & Franks, D. (2015). Social Impact Assessment: Guidance for assessing and managing the social impacts of projects. International Association for Impact Assessment (IAIA).

- Vanclay, F. 2020. Reflections on Social Impact Assessment in the 21st century. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 38(2):126-131.

- Vanclay F, Esteves AM, Aucamp I, Franks D. 2015. Social Impact Assessment: Guidance for assessing and managing the social impacts of projects.

- Human Resource Watch. 2024. "I Escaped with Only My Life": Abusive Forced Evictions in Pakistan. New York: Human Rights Watch.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).