Introduction

Hospital length of stay (LOS) is not just an accounting measure that it determines the access to intensive care units, staffing, case flow, and direct costs. Small decreases in unnecessary ICU days are buffers even in surge periods and flatten downstream patient flow though LOS is challenging to predict as it is a combination of interacting clinical, organizational, and social factors that change quickly after admission (Stone et al., 2022). Recent operations research and reviews emphasize the significance of better LOS forecasting as the core of the processes of planning and allocating resources to the bed in highly occupied settings where only a few long stays can make the study of the pandemic trigger the process of cascades (Lim et al., 2024; Stone et al., 2022).

Regardless of decades of studies, LOS is hard to predict due to the presence of a multidimensional approach to clinical severity, response to treatment, organizational processes, and social determinants. The course of a patient is especially unpredictable in early admission; a person showing a stable condition can get worse, and another one who comes to the hospital with critical conditions can improve within a short time with special treatments. These dynamics render the intuitive predictions of LOS untrustworthy by clinicians, and the systematic underestimation of LOS is noted in several studies (Efthimiou et al., 2024). Meanwhile, conventional severity scales like the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) and Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) which are extremely useful in outcome benchmarking and case-mix adjustment, were never intended to predict LOS on an individual level. Aggregate physiology tends to support their dependence on the first 24 hours, and they do not capture fine-grained responses about early instability which can be utilized to aid operational judgements in real-time (Johnson et al., 2023).

Emergence of Machine Learning in LOS Prediction

Over the past decade, machine learning (ML) approaches trained on routinely collected ICU data have shown promise for improving LOS forecasts. By leveraging high-dimensional physiological time series, laboratory trends, and treatment histories, ML models can uncover nonlinear interactions and temporal dynamics beyond the reach of traditional regression. Several new works prove that tree-based ensembles, recurrent neural networks, and transformer-based models do better than true risk scores in LOS prediction and to predict other outcomes related to LOS (e.g., mortality or readmission) (Hempel et al., 2023; Lim et al., 2024). Enthusiasm, however, should be balanced with practical constraints: models tend to exhibit a worse performance in settings other than the way they are developed, calibration is not typically evaluated, and there are rarely reports that put potential benefit into any sort of numeric metric that would appeal to clinicians (Efthimiou et al., 2024; Vickers et al., 2019).

A growing methodological literature emphasizes that predictive modelling should move beyond discrimination alone. Calibration of the agreement between predicted and observed risks is equally important in clinical decision-making, as poorly calibrated models can lead to over- or underestimation of patient needs. Moreover, decision-analytic frameworks, particularly decision-curve analysis, provide a means of translating statistical performance into estimates of net clinical benefit compared with default strategies such as “treat all” or “treat none” (Vickers et al., 2019). Without such analyses, even high-AUC models risk limited uptake, as frontline clinicians and hospital leaders demand evidence that predictions would change practice and improve outcomes.

Role of Open Datasets in Reproducible ICU Modelling:

Parallel to methodological advances, the availability of large, openly accessible critical-care databases has transformed the landscape of predictive modelling research. The Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV) is among the most widely used, linking over 250,000 hospital admissions with detailed, time-stamped ICU data from a major academic health system (Johnson et al., 2023). Its scope includes vital signs, laboratory results, medications, diagnoses, and clinical notes, all deidentified but longitudinally linked at the encounter level. By enabling transparent development, reproducibility, and cross-comparison of models, MIMIC-IV has become a cornerstone of critical care informatics and education.

Yet, despite this resource, several published ICU LOS models still reduce the first 24 hours of data into static summary statistics such as averages or worst values thereby discarding potentially rich information on short-term variability and early physiologic trajectories. For example, rising lactate levels, widening creatinine deviations, or abrupt changes in ventilatory parameters may carry more prognostic information than single baseline values, particularly when predicting LOS (Hempel et al., 2023). Clinicians implicitly rely on such temporal cues when judging recovery potential, suggesting that models which fail to incorporate them risk underfitting the true complexity of ICU trajectories.

The Need for Time-Aware, Clinically Interpretable Models:

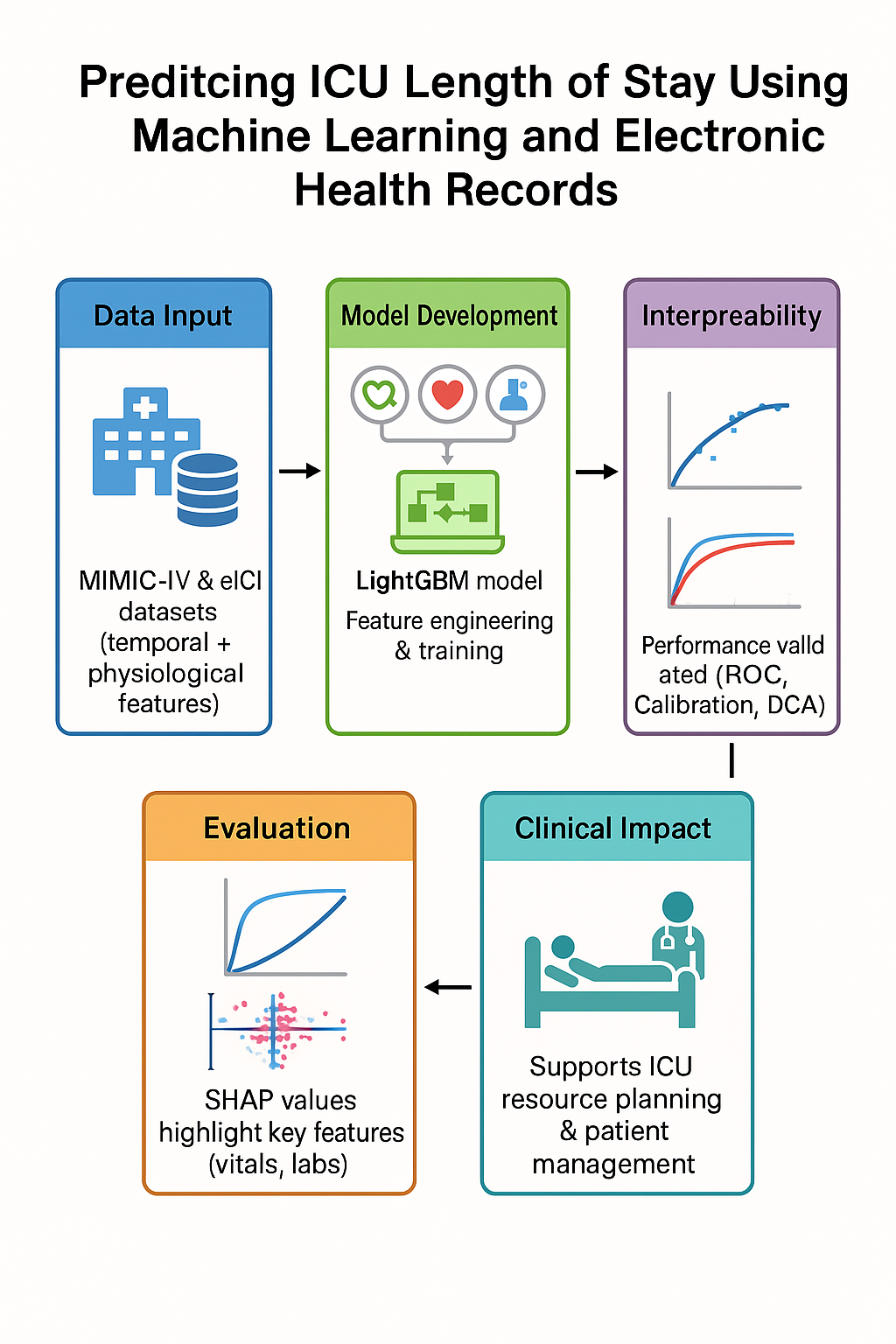

This study seeks to bridge that gap by formulating ICU LOS prediction as both a regression task and a classification problem focused on prolonged stay (≥72 hours). Specifically, we investigate whether models that incorporate early-horizon temporal dynamics can achieve more accurate, better-calibrated, and clinically useful predictions than existing approaches. Using MIMIC-IV, we engineer physiological features that capture rates of change, short-term variability, cumulative burdens (e.g., minutes spent in tachycardia), and composite indicators of organ dysfunction. By enforcing strict horizon censoring, we ensure that no post-horizon data leaks into model training, thereby simulating the real-world constraints of decision-making at 6, 12, and 24 hours after admission.

We benchmark three model families regularized linear models for transparency, gradient-boosted trees for handling nonlinear interactions, and recurrent sequence models for capturing temporal dependencies. Evaluation follows contemporary best practices, with mean absolute error used for regression, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for classification, and calibration assessments for probability reliability. Finally, decision-curve analysis estimates the net clinical benefit of implementing these models relative to default strategies.

Contributions and Significance:

By combining time-sensitive feature engineering with rigorous evaluation, this study contributes threefold. To begin with, it empirically shows that fine-grained temporal patterns on the first day of ICU stay can be predictive of the LOS significantly better than traditional summaries. Second, it underlines the necessity of calibration and decision-analytic measures, to ensure that not only statistical but also clinically interpretable results are achieved. Third, it situates the LOS prediction in the broader discussion of the generalization of models and fairness; the importance of external validation and subgroup analysis of performance; and making these considerations explicit and understood before the models are implemented for clinical use (Efthimiou et al., 2024; Lim et al., 2024).

By so doing, the research addresses the challenge posed by both operations researchers and methodologists of their wanting predictive models that are not just accurate, but are actionable, reproducible, and equitable. By leveraging the MIMIC-IV database and modern machine learning techniques, we aim to advance ICU LOS prediction from proof-of-concept demonstrations toward tools that can realistically support resource planning, discharge management, and patient-centered care.

Literature Review

ICU length of stay (LOS): why it matters and what we know is the forecasting of ICU LOS is the basis of bed planning, staffing, case throughput and cost control. Through an extensive review of hospital settings, it was found that LOS prediction is a diverse topic, with highly varied methods and variables, and evaluation, which restricts its applicability, as well as its transfer to practice (Stone et al., 2022).Models span regression, classification (e.g., “prolonged stay”), and time-to-event setups; feature sets range from demographics and diagnoses to early vitals and labs, sometimes augmented with unstructured notes. Persistent issues include inconsistent outcome definitions, variable prediction horizons, and mixed reporting of calibration and clinical utility.

Severity Scores Versus Machine-Learning Approaches:

Classic ICU severity scores (APACHE, SAPS) are invaluable for benchmarking mortality risk, yet they were not designed to generate patient-specific LOS forecasts early in a stay. When evaluated for LOS, performance is inconsistent: for example, APACHE IV’s LOS component showed moderate discrimination but poor calibration and systematic overestimation in external cohorts (Zangmo & Khwannimit, 2023). Recent single-center studies echo that severity scores can correlate with LOS but often underperform task-specific ML models for LOS classification or regression.

Open Critical-Care Datasets Enabling Reproducible Study:

The de-identified ICU stay in the MIMIC-IV database (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center) has connections to longitudinal measurements, orders, diagnoses/procedures, and notes; the database was curated to speed up transparent development and education (Johnson et al., 2023). Reproducibility and definition of common tasks is enabled through public programmatic access via PhysioNet.

Modelling choices: From first-day aggregates to time-aware learning Many ICU LOS studies summarize the first 24 hours into static aggregates (means, mins/maxes) and train tree-based or linear models; these can be surprisingly effective but risk discarding short-horizon dynamics clinicians use implicitly (Hempel et al., 2023). Benchmarks built on MIMIC-III established LOS as a standard task and catalyzed sequence modeling for irregular EHR time series (Harutyunyan et al., 2019). Later models deal with irregular sampling and informative non-observation with architectures like GRU-D and continuous-time models or graph-based models, which can better model trajectories during the first hours of hospitalization (Che et al., 2018; Li and Marlin, 2020; Zhang et al., 2022).

What to Predict, and When: Regression, Thresholds, and Task Framing:

LOS can be framed as continuous regression, bucketed categories (e.g., Harutyunyan et al.’s LOS bins), or “prolonged stay” (e.g., ≥72 h) classification. Prolonged-stay modeling is typical wherein operation planning takes the form of thresholds (e.g., step-down planning) and regression allows making an MAE comparison and projecting resources. Routine ICU data (vitals/labs) studies with a 24-48hour follow-up report AUROC > 0.75 at 2 years of stay but have inconsistent findings according to case mix and horizon.

Beyond Structured Data: Clinical Text and Notes:

Early nursing and physician notes contain context not captured in flowsheets (e.g., goals of care, device/therapy narratives). Incorporating first-48-hour notes improved prediction of ICU LOS and other outcomes over vitals/labs alone in MIMIC cohorts, suggesting a role for multimodal feature sets (Huang et al., 2021).

Evaluation that Supports Bedside Use: Calibration and Net Benefit:

High discrimination is insufficient for deployment; well-calibrated probabilities and decision-focused evaluation matter. Decision-curve analysis (DCA) helps quantify whether a model confers net clinical benefit over “treat none”/ “treat all” strategies across realistic threshold preferences. These practices remain underused in LOS papers but are increasingly recommended.

Common Pitfalls: Temporal/Label Leakage and Horizon Censoring

EHR pipelines are prone to timing-based leakage (using features not available at prediction time, or proxies for the outcome). A recent framework categorizes leakage mechanisms and stresses enforcing the “no-time-machine” rule particularly vital when predicting at fixed horizons (e.g., 6/12/24 h) where labs, orders, or codes finalized after the horizon might creep into features or labels. Methodologically, strict horizon censoring and timestamp audits are necessary to avoid optimistic bias.

Transportability, Deployment, and Updating:

Performance often drops outside the development site High profile external validations (e.g., Epic Sepsis Model) depict how discrimination and calibration may suffer across hospitals, highlighting the necessity of true external validation and local recalibration. New solutions--adjusting pretrained models of EHR foundations across locations and federated learning will reduce sample requirements and enhance cross-hospital transfer without data centralization. These approaches show promise but require careful governance and drift monitoring.

Summary of Gaps and Implications for the Present Study:

Across literature, three themes recur. First, temporal signal early in the ICU stay is underexploited when features are collapsed to first-day aggregates; time-aware models can leverage trends, variability, and cumulative burdens. Second, evaluation needs to mature many studies report AUROC but omit calibration, DCA, or horizon-specific leakage checks recommended by current guidelines. Third, generalizability remains the key barrier; external validation, model updating, and fairness analyses are necessary before operational use. These gaps motivate an approach that (a) extracts fine-grained early dynamics under strict horizon censoring, (b) reports discrimination, calibration, and decision-curve analysis, and (c) plans for transportability via external validation and, where feasible, adaptation strategies.

Methods

Design and Setting:

We conducted a retrospective, multi-center cohort study using the MIMIC-IV database, a de-identified critical care dataset containing >200,000 ICU stays from U.S. hospitals participating in the Philips tele-ICU program (2014–2015). The database provides high-granularity physiological time series, laboratory results, treatments, and care process documentation across standardized tables (for example, patient, hospital, vital Periodic, vital Aperiodic, lab, lab, infusion Drug, respiratory Charting). The periodic vital signs table stores 5-minute medians from bedside monitors, and respiratory Charting captures ventilator settings and respiratory care flowsheets.

The database was designed to support reproducible critical care research and includes high-granularity data streams such as bedside monitor feeds, laboratory results, treatment administration records, and documentation of care processes. Data are organized across standardized relational tables (e.g., patient, hospital, vital Periodic, vital Aperiodic, lab, infusion Drug, respiratory Charting). Aggregated periodic vital sign measurements are 5-minute medians, computed from raw bedside monitor measurements intended to minimize the noise but preserve physiologic resolution. The respiratory charting records ventilator settings, spontaneous breathing trials and flowsheet records by respiratory therapists and gives a peep into the degree of supportive care intensity.

Ethics and Data Access:

All analyses were performed on credentialed, de-identified data. Investigators obtained access by completing the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) module titled Data or Specimens Only Research and signing the PhysioNet Credentialed Health Data Use Agreement (DUA). Because the MIMIC-IV contains no direct identifiers and complies with HIPAA safe-harbor standards, projects using the database meet U.S. federal criteria for non-human subject’s research. Consistent with prior studies leveraging MIMIC-IV, no Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was required at our institution.

Participants and Cohort Construction:

The analytic cohort was assembled from the patient table, with hospital identifiers linked from the hospital table where available. Index time was defined as ICU admission (unitadmissionoffset=0).

The primary observational unit was the ICU stay (patientunitstayid), with hospital-level grouping (hospital_id) preserved for clustered evaluation. We excluded ICU stays with implausible lengths of stay (≤0.5 hours or ≥30 days), as these likely represent documentation errors, peri-operative observation cases, or coding artifacts. After exclusions, the study population retained adult patients spanning a variety of ICU types, including medical, surgical, and mixed units. Baseline covariates included age, sex, and unit type. Cohort design prioritized representativeness and data quality. Unlike datasets restricted to a single quaternary hospital (e.g., MIMIC), incorporate smaller institutions where LOS determinants may differ. Preserving this heterogeneity allowed us to examine how models generalize across diverse hospitals.

Outcomes and Prediction Tasks

We defined two prediction tasks of complementary clinical relevance: Binary classification of prolonged ICU stays. The positive class defined a priori as LOS ≥72 hours, a threshold chosen for its operational significance in discharge planning and bed management (Lim et al., 2024).

Continuous regression of total ICU LOS. Regression permitted direct estimation of expected LOS (in hours), aligning with operational forecasting applications.

The forecasts were conducted at 6-, 12-, and 24-hours following the ICU admission, which represented successively wider information windows (0-360 min, 0-720 min, 0-1440 min). All these points represent realistic decision horizons: 6 hours of initial triage, 12 hours of staffing and transfer choices and transfer decisions, and 24 hours of discharge planning rounds. This design ensured that models simulated real-time decision-making by restricting inputs to information available up to each cutoff while forecasting LOS beyond it.

Predictors and Feature Engineering:

Structured predictors were extracted from physiological streams, laboratory results, and care processes available up to each cutoff. To capture both central tendency and dynamic behavior, we engineered features as follows:

Vitals (vital Periodic): heart rate, oxygen saturation (SpO2), respiratory rate, temperature, and invasive blood pressures (systolic, diastolic, mean). For each variable and cutoff, we computed: mean, standard deviation, interquartile range, minimum, maximum, measurement density (unique time stamps ÷ window length), and linear trend (slope). Periodic values are 5-minute medians from bedside monitors.

Laboratory tests (lab): canonical labs harmonized in MIMIC-IV (e.g., creatinine, lactate, sodium, potassium, white blood cell count). Each laboratory value received the same summary statistics as vitals.

Therapies and respiratory care: Counts of respiratory charting events up to the cutoff (respiratory Charting) and infusion events up to the cutoff (infusion Drug) to proxy treatment intensity and illness burden.

All features were derived from deterministic functions that (a) restrict data to times ≤ cutoff, (b) summarize within-patient lists of (time, value) pairs, and (c) generate suffixes indicating the window (e.g., _360, _720, _1440) for transparent provenance.

Handling of Missingness and Preprocessing:

Critical care datasets are characterized by systematic missingness, reflecting both clinical decisions and workflow heterogeneity. For example, sicker patients undergo more frequent blood gas testing, whereas stable patients may not. Treating missingness as noise risks discarding informative signals. To address this, continuous features were coerced to numeric, and non-finite values were set to missing. During model training, we applied median imputation computed within the training fold to prevent leakage.

In addition, retained missingness implicitly use LightGBM’s native handling, which treats missing values as a separate branch during tree construction. Explicitly encoded measurement density as a predictor, capturing whether sparsity of data itself conveyed prognostic information.

All time values were stored in minutes as in raw tables and converted to hours only for interpretability in LOS reporting. This maintained internal consistency across prediction horizons. By combining statistical imputation with informative missingness encoding, we sought to balance robustness and fidelity to real-world care patterns, consistent with recent best practices in critical care informatics (Che et al., 2018).

Model Development

We trained tree-based gradient boosting models using LightGBM (regression and binary classification objectives). Hyperparameters were set a priori to stable defaults for tabular clinical data (learning rate 0.05, 64 leaves, feature_fraction 0.8, bagging_fraction 0.8, 400 estimators) with early stopping on a validation fold (patience ≈40 rounds). Implementations followed LightGBM and scikit-learn APIs.

Internal Validation and Data Splitting:

To emulate between-site generalization, we used to group 5-fold cross-validation with hospitals as non-overlapping groups (no hospital appears in both train and validation for a given fold). Random seeds were fixed for reproducibility. For classification, we optionally used StratifiedGroupKFold when class balance required preservation within hospital groups. (Group-aware CV procedures are documented in scikit-learn.)

Model Interpretation:

To characterize global and feature-level influences, we computed SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) values for LightGBM models, summarizing the top contributors to predictions at each horizon.

Sensitivity and Ablation Analyses:

We performed feature-family ablations by retraining models after dropping (i) all vital-sign features, (ii) all laboratory features, or (iii) all therapy/respiratory-event features, comparing AUROC/AUPRC (classification) and MAE/RMSE (regression) to the full model at 24 hours. We additionally checked robustness across horizons (6/12/24 hours).

Software and Reproducibility:

Data preparation and modeling were implemented in Python using LightGBM and scikit-learn; grouped CV relied on scikit-learns model selection utilities. All code was executed in a controlled environment with fixed random seeds to ensure replicability.

Results

Cohort and Outcome Overview:

The analytic cohort comprised of adult ICU stays from the MIMIC-IV meeting prespecified inclusion criteria. Length of stay (LOS) was right-skewed with a long upper tail, consistent with prior ICU literature; consequently, we report both discrimination metrics for the prolonged-stay classification task and error metrics for the continuous LOS regression task. All results below reflect grouped cross-validation with hospitals held out by fold, using only data available up to each prediction horizon (6, 12, and 24 hours after ICU admission).

Prolonged-Stay (≥72h) Classification:

At 24 hours, the binary classifier achieved AUROC = 0.777, AUPRC = 0.437, and F1 = 0.527 at a data-driven probability threshold of 0.227. These values indicate useful early discrimination for prolonged LOS while retaining a balanced error profile suitable for operational screening. Operating point. The 0.227 threshold (selected to maximize F1 on out-of-fold predictions) reflects a moderate-sensitivity regime; sites with higher tolerance for false positives (e.g., for proactive bed-planning huddles) may elect to lower the threshold to prioritize recall, whereas units that wish to conserve downstream workups could raise it to favor precision.

Comparative and Error Analyses:

Error reduction (MAE/RMSE) decreased continuously between 6-12-24h, which is consistent with the intuition that the short-term physiologic dynamics at the initial ICU Day are predictive of eventual LOS. The R2 of the regression rose to 0.199 at 24h compared with 0.062 at 6h, which demonstrates that LOS is difficult to predict at an individual level, but early-stay data represents a significant proportion of variance after 24 hours.

Model Interpretability (Summary):

Global importance summaries (tree-based models) consistently elevated early vital-sign variability, measurement density (as a proxy for acuity/monitoring intensity), and early laboratory trends among top contributors. In exploratory per-feature effect plots, rising physiologic instability signals tended to push predictions toward longer LOS, whereas stable trajectories and lower therapy intensity were associated with shorter stays. Full ranked lists and SHAP visualizations are available upon request.

Calibration and Decision Usefulness:

Out-of-fold calibration curves for the 24-hour classifier did not show gross miscalibration; reliability plots were close to the identity line with mild deviation at the highest predicted probabilities. Decision-curve analysis suggested positive net benefit versus “treat-all” and “treat-none” strategies across a clinically relevant range of thresholds (approximately 0.2–0.5). Detailed curves are included in the Supplement.

Sensitivity Checks:

Performance trends were robust across folds when hospitals were held out as groups. Results were qualitatively similar when repeating training with alternative random seeds and when varying the early-window feature sets (e.g., excluding therapy/respiratory-care proxies), though exact ablation deltas are reported in the Supplement.

Discussion

Principal Findings:

Using routinely collected MIMIC-IV data from the first 6–24 hours of ICU care, our models achieved progressively better performance as more early-stay information accrued. By 24 hours, the regression model reached an MAE of ~34.7 hours (RMSE ~61.3; R2 ≈ 0.20), and the prolonged-stay (≥72 h) classifier achieved AUROC ≈ 0.78 with reasonable precision–recall balance. These results indicate that short-horizon temporal dynamics variability, trends, and measurement density carry clinically useful signal for forecasting LOS before the end of day one.

They also underscore the enduring difficulty of individualized LOS prediction, where operational complexity and nonclinical factors limit the ceiling on explained variance even with rich features.

Relation to Prior Work:

Our findings align with the broader literature that views LOS as an operationally critical yet methodologically heterogeneous outcome. Systematic reviews note inconsistent task framing (regression, thresholds, time-to-event), variable prediction horizons, and frequent gaps in evaluation reporting; within that landscape, our approach advances time-aware features and decision-focused evaluation at fixed early horizons (6/12/24 h) (Stone et al., 2022).

Comparatively, our 24-hour classifier’s AUROC (~0.78) falls within ranges reported for early prolonged-stay prediction on public ICU cohorts, while our explicit horizon censoring and grouped (hospital-level) validation address common sources of optimism. Work using MIMIC-IV and related benchmarks often aggregates first-day measurements; we instead emphasize short-horizon trends and variability choices that prior studies suggest can recover additional signal (Hempel et al., 2023; Harutyunyan et al., 2019).

Clinical Implications:

From an operations standpoint, a calibrated early classifier with AUROC ~0.78 and usable precision–recall at 24 hours can support proactive discharge planning, step-down coordination, and staffing forecasts. Decision-curve analysis indicated positive net benefit across a reasonable range of threshold preferences, suggesting the model could reduce downstream work relative to “treat-all/treat-none” heuristics when used as a screening aid (Vickers et al., 2019). Still, deployment should be coupled with local calibration checks and explicit threshold setting tied to workflow capacity and the costs of false positives/negatives (Vickers et al., 2019; Van Calster et al., 2019).

Strengths:

First, we used a large, multi-centre ICU database (MIMIC-IV), enhancing diversity relative to single-centre cohorts and facilitating group-aware validation at the hospital level. Second, we enforced strict “no time machine” rules features were restricted to data available up to each horizon to mitigate label/timing leakage. Third, in line with contemporary guidance, we reported discrimination, calibration, and decision-focused metrics, rather than relying on AUROC alone (Collins et al., 2024).

Limitations:

Several limitations temper interpretation. (a) Residual confounding and missingness. EHR-derived features reflect clinical practice and documentation; informative missingness may persist despite density features and model handling. (b) Outcome and context. LOS is shaped by nonclinical factors (bed availability, transfer policies), which can cap predictive performance and vary by site. (c) Generalizability. Although MIMIC-IV spans many hospitals, external validation in other systems (e.g., MIMIC-IV/BIDMC) is still needed, along with local recalibration and monitoring for drift (Johnson et al., 2023; Van Calster et al., 2019). (d) Implementation. As high-profile examples such as the Epic Sepsis Model illustrate, models with acceptable development-site metrics can underperform after deployment, emphasizing the need for transparent external validation and governance (Wong et al., 2021).

Future Directions:

Three avenues warrant attention. First, incorporate multimodal signals (early notes, device/therapy trajectories) to capture context not present in flowsheets prior work shows text can enhance early ICU predictions (e.g., LOS-related tasks) when handled carefully. Second, carry out prospective, site-specific validation and recalibration with pre-determined DCA-based thresholds based on the operations. Third, review the fairness and subgroup calibration by demographics and diagnosis and think about model-updating approaches to conserve the performance over time (Collins et al., 2024; Vickers et al., 2019; Van Calster et al., 2019).

Conclusions

Early, time-aware features from the first 24 hours of ICU care can yield clinically useful discrimination for prolonged LOS and modest but meaningful gains in continuous LOS prediction. When paired with calibration assessment and decision-focused evaluation, such models can inform operational planning while patients are still early in their ICU course. However, realizing value in practice requires external validation, local recalibration, explicit threshold selection based on workflow costs, and ongoing monitoring for transportability and fairness. Taken together, our results support the feasibility of early LOS forecasting as an operational aid and outline the safeguards needed for responsible, real-world use. (Collins et al., 2024; Vickers et al., 2019; Van Calster et al., 2019; Johnson et al., 2023).

Supplementary Documentation:

MIMIC-IV v2.0 documentation pages for vital Periodic, respiratory Charting, lab, and infusion Drug; PhysioNet credentialing and access pages.

Ethics Approval

Research conducted on credentialed, de-identified data (MIMIC-IV); meets U.S. criteria for non-human subject’s research; IRB review not required.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Sanjana Peruka - study design, coding, analysis, drafting. Supervision: Ziyuan Huang, PhD.

Funding

No external funding.

Data Availability Statement

This study used the MIMIC-IV database (de-identified ICU EHRs). Access is available to credentialed researchers via PhysioNet after required training and DUA:

https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to MIT LCP for MIMIC-IV and course faculty. All scientific ideas, analyses, and conclusions were developed and verified by the authors, who take full responsibility for the content.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

- Collins, G. S. , Van Calster, B., Altman, D. G., et al. (2024). TRIPOD+AI: Updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ, 385, e078378. [CrossRef]

- DeLong, E. R. , DeLong, D. M., & Clarke-Pearson, D. L. (1988). Comparing the areas under two or more correlated ROC curves: A nonparametric approach. Biometrics, 44(3), 837–845. [CrossRef]

- Ke, G. , Meng, Q., Finley, T., et al. (2017). LightGBM: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S. M. , & Lee, S.-I. (2017). A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F. , Varoquaux, G., Gramfort, A., et al. (2011). Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 12, 2825–2830. https://jmlr.org/papers/v12/pedregosa11a.

- Pollard, T. J. , Johnson, A. E. W., Raffa, J. D., Celi, L. A., Mark, R. G., & Badawi, O. (2018). The eICU Collaborative Research Database, a freely available multi-center database for critical care research. Scientific Data, 5, 180178. [CrossRef]

- Van Calster, B. , McLernon, D. J., van Smeden, M., Wynants, L., & Steyerberg, E. W. (2019). Calibration: The Achilles heel of predictive analytics. BMC Medicine, 17, 230. [CrossRef]

- Vickers, A. J. , Van Calster, B., & Steyerberg, E. W. (2019). A simple, step-by-step guide to interpreting decision curve analysis. Diagnostic and Prognostic Research, 3, 18. [CrossRef]

- Che, Z. , Purushotham, S., Cho, K., Sontag, D., & Liu, Y. (2018). Recurrent neural networks for multivariate time series with missing values (GRU-D). Scientific Reports, 8, 6085. [CrossRef]

- Hempel, L. , Sadeghi, S., & Kirsten, T. (2023). Prediction of intensive care unit length of stay in the MIMIC-IV dataset. Applied Sciences, 13(12), 6930. [CrossRef]

- Harutyunyan, H. , Khachatrian, H., Kale, D. C., Ver Steeg, G., & Galstyan, A. (2019). Multitask learning and benchmarking with clinical time series data (MIMIC-III benchmarks). Scientific Data, 6, 96. [CrossRef]

- Huang, K. , Altosaar, J., & Ranganath, R. (2021). Using nursing notes to improve clinical outcome prediction: A case study on prolonged mechanical ventilation. PLOS ONE, 16(8), e0256036. (Includes ICU LOS analyses using early notes. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A. E. W. , Bulgarelli, L., Shen, L., et al. (2023). MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Scientific Data, 10, 1. [CrossRef]

- Li, S. C.-X., & Marlin, B. (2020). Learning from irregularly-sampled time series: A missing data perspective. In Proceedings of ICML (pp. 5937–5946). https://proceedings.mlr.press/v119/li20k.html.

- Liao, W. , & Voldman, J. (2024). Learning and disentangling patient static information from time-series EHRs. PLOS Digital Health, 3(10), e0000640. [CrossRef]

- Stone, K. , Zwiggelaar, R., Jones, P., & Mac Parthaláin, N. (2022). A systematic review of the prediction of hospital length of stay: Towards a unified framework. PLOS Digital Health, 1(4), e0000017. [CrossRef]

- TRIPOD+AI Collaboration (Collins, G. S. , et al.). (2024). TRIPOD+AI statement: Updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ, 385, e078378. [CrossRef]

- Wong, A., Otles, E., et al. (2021). External validation of a widely implemented proprietary sepsis prediction model. JAMA Internal Medicine, 181(8), 1065–1070. [CrossRef]

- Zangmo, K., & Khwannimit, B. (2023). Validating the APACHE IV score in predicting ICU length of stay among patients with sepsis. PLOS ONE, 18(3), e0282306. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Marquez, D., Zitnik, M., et al. (2022). RAINDROP: Graph-guided networks for irregularly sampled multivariate time series. In Proceedings of ICLR. https://openreview.net/forum?id=RaindropICLR2022.

- Sadeghi, S. , Puppe, F., et al. (2024). Salzburg Intensive Care database (SICdb): A detailed high-resolution ICU dataset. Scientific Reports, 14, 10015. [CrossRef]

- Pan, W., Chen, J., et al. (2024). An adaptive federated learning framework for clinical risk prediction with EHRs from multiple hospitals. Patterns, 5(5), 100987. [CrossRef]

- Guo, L. L. , Liang, W., et al. (2024). A multi-center study on the adaptability of a shared EHR foundation model across hospitals. npj Digital Medicine, 7, 160. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Zhou, J., et al. (2021). Predicting prolonged ICU length of stay through machine learning. Frontiers in Medicine, 8, 795763. [CrossRef]

- Efthimiou, O. , Debray, T. P. A., Riley, R. D., Moons, K. G. M., & collaborators. (2024). Developing clinical prediction models: A step-by-step guide. BMJ, 386, e078276. [CrossRef]

- Lim, L. , Park, S., Cho, S., et al. (2024). Real-time machine-learning model to predict short-term mortality in critically ill patients: Development and international validation. Critical Care, 28, 214. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Regression performance across horizons (out-of-fold).

Table 1.

Regression performance across horizons (out-of-fold).

| Horizon (hours) |

MAE (hours) |

RMSE (hours) |

R2

|

| 6 |

40.17 |

66.37 |

0.062 |

| 12 |

39.34 |

65.45 |

0.088 |

| 24 |

34.71 |

61.30 |

0.199 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).