1. Introduction

Survival and clinical outcomes among patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) following successful resuscitation after cardiac arrest vary significantly. Even when return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) is achieved in this patient population, mortality rates remain high due to post-cardiac arrest syndrome, multiple organ failure, and the severity of underlying causes (1). According to the American Heart Association’s 2020 guidelines, key factors influencing survival during the post-ROSC care process include maintaining hemodynamic stability, assessing neurological prognosis, and implementing targeted therapeutic interventions (2).

Early biochemical parameters and clinical scoring systems obtained during the ICU stay can serve as valuable tools in predicting patient prognosis. One of the most common reasons for ICU admission is sepsis and septic shock. Among the biochemical markers most frequently monitored in patients with these diagnoses, procalcitonin and C-reactive protein (CRP) are the most important. CRP is generally used as a marker of inflammation, whereas procalcitonin is widely employed to differentiate bacterial infections from viral or other inflammatory conditions, as well as to monitor treatment response. Elevated levels of these biomarkers are typically proportional to the severity of the infection in cases of sepsis and septic shock (3, 4, 5). CRP, which is produced by the liver, may exhibit limited elevation in response to infection in cases of hepatic failure (6). On the other hand, procalcitonin levels may increase independently of infection in the presence of severe renal failure (7). These relationships can become even more complex in the aftermath of cardiac arrest.

Liver function tests (LFTs) such as aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP), as well as renal function indicators like glomerular filtration rate (GFR), can be significantly affected following cardiac arrest, primarily due to the susceptibility of the liver and kidneys to ischemia. Therefore, elevations in LFTs and reductions in GFR may serve as critical prognostic indicators of survival in post-cardiac arrest patients (8, 9).

In addition, hematologic parameters such as platelet count, mean platelet volume (MPV), and white blood cell count have been reported in the literature as factors potentially associated with ICU survival (10, 11, 12).

Beyond laboratory values, scoring systems like APACHE II, SOFA, the NUTRIC score, NRS-2002, and the Charlson Comorbidity Index are also useful for predicting patient mortality risks (13, 14).

Comparing post-cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) patients with a control group that has similar clinical characteristics but did not experience cardiac arrest may help to more clearly identify mortality predictors specific to this unique patient population. Previous studies have demonstrated that systemic inflammation and reperfusion injury in post-resuscitation patients have a significant impact on ICU mortality (15).

Machine learning techniques have the capability to analyze a greater number of variables simultaneously and model complex relationships more effectively than traditional statistical methods. In this context, supervised learning algorithms such as random forest have gained prominence in recent years for medical data analysis. Several studies have shown that random forest may offer advantages over traditional methods in predicting mortality (16).

However, in cases where sample size is limited, resampling techniques such as SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) are required to handle imbalanced datasets. In addition to SMOTE, other oversampling methods such as Borderline-SMOTE and ADASYN (Adaptive Synthetic Sampling) are also available. In the medical literature, there are studies demonstrating that outcomes obtained from AI-based data augmentation techniques applied to real patient datasets yield results comparable to those obtained through statistical analyses on actual patient data (17, 18).

In this study, patients admitted to the ICU following cardiac arrest were compared with those admitted without having experienced cardiac arrest in order to identify key determinants of mortality and perform survival analyses based on the parameters discussed above. Furthermore, it was planned to perform sample augmentation using the collected data. Models developed using machine learning techniques (random forest) with augmented and balanced datasets were compared with models built using traditional statistical approaches. This study was structured using the TRIPOD-AI statement checklist, published in 2024 to enhance the transparency and reliability of clinical prediction modeling studies involving machine learning methods (19).

2. Materıals and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval and Patient Consent

This study was conducted with the approval of the Ethics Committee of Ankara Atatürk Sanatorium Training and Research Hospital under decision number 2024-BÇEK/226. Informed consent forms were obtained from all patients, and the study was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Study Design

This retrospective observational study includes patients who were monitored in the Level 3 Anesthesia Intensive Care Unit of Ankara Atatürk Sanatorium Training and Research Hospital between January 1, 2020, and January 1, 2023. Among a total of 706 patients, 41 patients who experienced witnessed in-hospital cardiac arrest and achieved return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) following effective cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) were defined as the post-CPR group. The control group consisted of 41 patients randomly selected from those admitted to the ICU during the same period who had not undergone CPR. Thus, a total of 82 patients were included in the study.

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

Age over 18 years

Monitored in the ICU for at least 24 hours

For the post-CPR group: patients who experienced witnessed arrest while hospitalized and received CPR administered by a healthcare professional for no longer than one hour, achieving ROSC and subsequently admitted to the ICU

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

Patients under 18 years of age

ICU follow-up duration of less than 24 hours

Patient records containing incomplete data

Demographic characteristics (age, sex, body mass index), as well as clinical and biochemical data, were collected. For parameters known in the literature to be associated with poor prognosis when elevated, the highest values within the first 24 hours following ICU admission were recorded. Conversely, for parameters where lower values are linked to poor prognosis, the lowest values during the same time frame were considered. These parameters included procalcitonin, CRP, AST, ALT, GGT, ALP, GFR, albumin, platelet count, MPV, and white blood cell count.

Clinical scoring systems (APACHE II, SOFA, NUTRIC, NRS-2002, and Charlson Comorbidity Index), ICU length of stay, mortality status, use of inotropic therapy, ICU readmission, presence of malignancy, and reason for ICU admission (e.g., type 2 respiratory failure, myocardial infarction) were also recorded. A total of 27 parameters were reviewed, collected, and analyzed as part of the study. Clinical scores, such as APACHE II and SOFA, were retrospectively validated by experienced intensive care specialists. Mortality data were extracted automatically from the hospital’s information system, eliminating the possibility of observer bias.

2.5. Statistical Analysis and Machine Learning Techniques

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Machine learning modeling was conducted using the Python programming language. The official reference distribution, CPython version 3.10, was utilized within the development environment provided by the Python Software Foundation (PSF) [

https://www.python.org]. The environment was set up through the Anaconda distribution (Version 2023.07, Anaconda Inc.), which is widely used for data science and machine learning applications. For machine learning tasks, the scikit-learn library version 1.3.0 was employed, while the imbalanced-learn library version 0.11.0 was used for sample balancing procedures. All algorithms were implemented through the standard Python API, with hyperparameter tuning performed manually for optimization.

The normality of the dataset analyzed using SPSS was assessed through skewness, kurtosis, histograms, outlier analyses, and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. Variables following a normal distribution were described using mean ± standard deviation, while non-normally distributed variables were expressed as median (min–max).

For comparisons between groups, the independent samples t-test was used for normally distributed variables, and the Mann-Whitney U test was applied for non-normally distributed variables. When significant results were obtained using the t-test, Cohen’s d value was provided to indicate the effect size. For categorical variables, chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were employed. The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to compare survival durations between the post-CPR group and the other patient group. Furthermore, discriminant analysis was applied to identify clinical and laboratory features that could differentiate between post-CPR patients and other ICU patients. Both the Enter and stepwise methods were utilized in the discriminant models. A 95% confidence interval and a significance threshold of p<0.05 were adopted for all traditional statistical analyses.

2.6. Data Imbalance and Oversampling Method

Within the scope of this study, clinical data from a total of 82 patients admitted to the ICU—divided into two subgroups: “post-CPR” and other ICU patients—were retrospectively analyzed. A significant class imbalance was observed between the “deceased” and “survived” cases within each subgroup.

To address this issue, the Adaptive Synthetic Sampling (ADASYN) algorithm, a synthetic data generation method, was applied to the overall dataset. ADASYN aims not only to increase the number of minority class samples but also to focus on areas near the class boundaries that are more difficult for classification, thereby improving the generalizability of the model. This approach identifies the k-nearest neighbors for each minority class instance (with k set to 2 in this study) and uses adaptive weighting to generate new synthetic examples through interpolation. As a result, synthetic samples for the minority class are modeled to reflect a more natural distribution within the data space.

2.7. Random Forest Classification Method

After addressing the sample imbalance, the Random Forest classification algorithm was independently applied to both the post-CPR subgroup and the complete patient cohort. Random Forest is a machine learning method that aggregates numerous decision trees within an ensemble framework, offering high accuracy, relatively low variance, and robustness against overfitting.

During model training, each tree was trained on a different bootstrap sample drawn with replacement from the dataset. A random subset of features was evaluated at each decision node within a tree. These mechanisms (bagging and feature subsetting) help reduce correlation among trees and enhance the model’s generalization capacity.

The classification decision in Random Forest is made based on a majority vote across the trees. During model training and validation, stratified k-fold cross-validation (k=5) was applied to ensure balanced class representation across each fold. The model’s performance was evaluated using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and the area under the ROC curve (AUC).

Additionally, feature importance scores were computed to identify the most influential clinical parameters for mortality prediction. These scores were calculated based on the cumulative reduction of Gini impurity across all trees. The models were trained using the scikit-learn library, and the source code can be made available for research purposes.

In both models, 70% of the dataset was used for training and 30% for testing. Given the limited sample size, each sample split was randomized ten times, resulting in ten separate models with 70-30 training-test splits. The average performance metrics of these models were reported to maximize utility from the limited number of cases.

The model output was defined both as a classification and a probability. Any predicted probability above 50% was classified as high mortality risk.

The source codes of the developed models have been made publicly available in the form of Python script files (.py).

3. Results

3.1. General Data and Traditional Statistical Findings

Upon analyzing the demographic and baseline clinical data of the 82 patients included in the study, the median age of the post-CPR group was 70.0 years (65.0–83.0), while it was 68.0 years (60.0–74.0) in the other ICU patient group. There was no statistically significant difference in age between the groups (p = 0.118,

Table 1,

Table 2). In terms of gender distribution, 70.7% of the post-CPR group were male, compared to 68.3% in the other ICU group; the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.810,

Table 3).

Regarding malnutrition risk, the post-CPR group had significantly higher median NUTRIC scores, while there was no meaningful difference in NRS-2002 scores between the groups (p = 0.002 and p = 0.171, respectively,

Table 2). The presence of malignancy at any stage was similar between the groups (p = 0.794,

Table 3). ICU readmission rates were identical in both groups (

Table 1), and body mass index (BMI) values were also comparable. No significant differences were observed in comorbidities between groups (

Table 2).

However, as expected, the APACHE II scores-calculated based on a variety of clinical and laboratory parameters-were significantly higher in the post-CPR group (p<0.001,

Table 2).

When examining clinical and laboratory parameters reflecting inflammation and infection, the post-CPR group had significantly elevated markers. Specifically, CRP, procalcitonin (PCT), and SOFA scores were all significantly higher in the post-CPR group compared to the other ICU group (all p < 0.001,

Table 2).

Indicators of multi-organ failure and/or post-ischemic conditions, such as ALT, AST, and GFR, were also worse in the post-CPR group (p = 0.008, p < 0.001, and p = 0.042, respectively,

Table 2). Serum albumin levels were found to be significantly lower in the post-CPR group (p = 0.002). While platelet counts did not significantly differ between the groups (p = 0.441), MPV was significantly higher in the post-CPR group (p = 0.021,

Table 2).

When comparing post-CPR patients with other ICU patients across various categorical variables, significant differences were observed. The need for inotropic support was notably higher in the post-CPR group (73.2% vs. 22.0%, p < 0.001). ICU mortality was 75.6% in the post-CPR group, compared to 36.6% in the other ICU group—a statistically significant difference (p < 0.001). Similarly, hospital mortality was also higher in the post-CPR group (80.5% vs. 39.0%, p < 0.001). Conversely, the incidence of type 2 respiratory failure was significantly lower in the post-CPR group (36.6% vs. 70.7%, p = 0.002), indicating clinical differences between the groups (

Table 3).

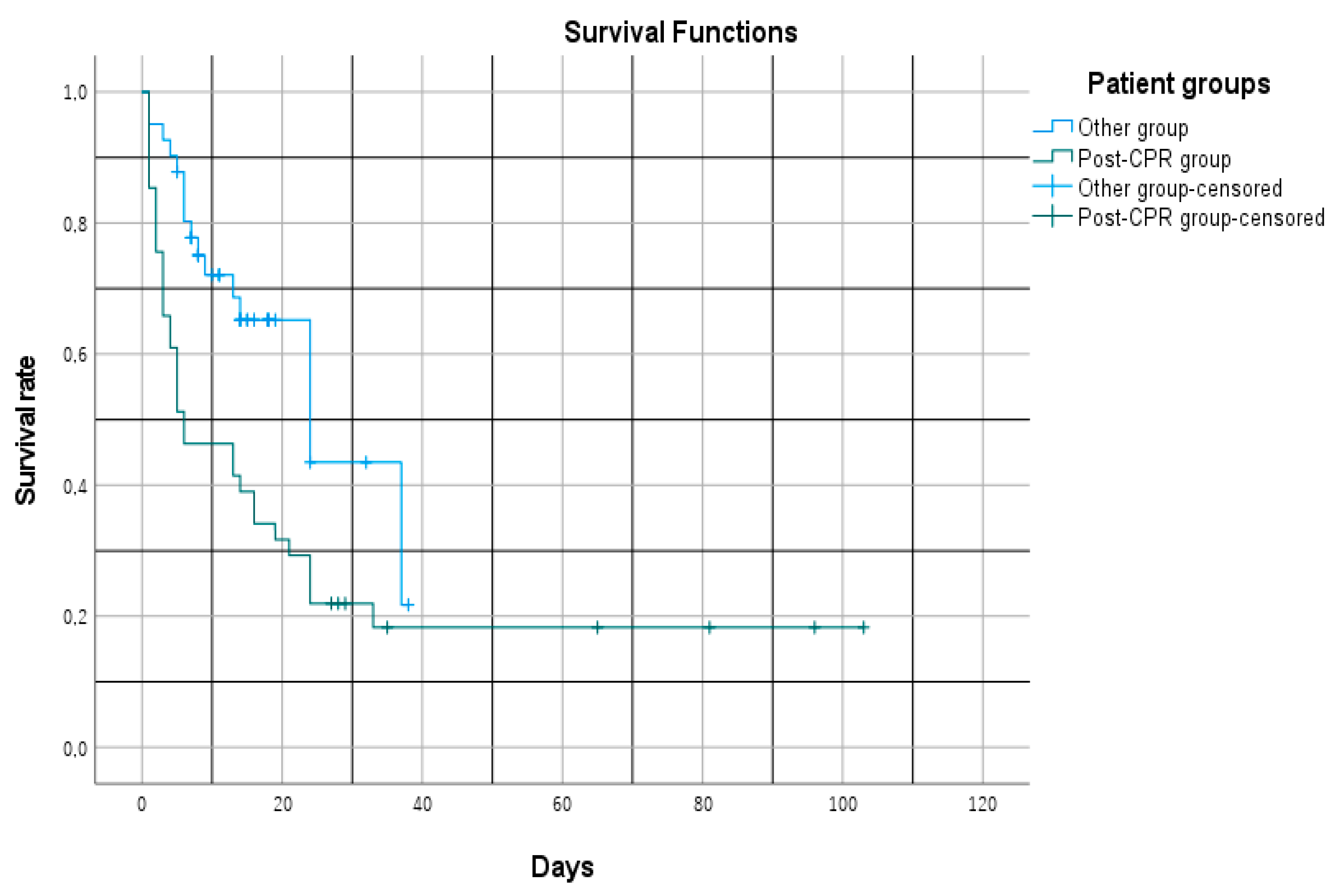

When survival durations of post-CPR patients and other ICU patients were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method, a statistically significant difference was observed between the groups (Log-rank test, χ² = 7.470, p = 0.006). The mean survival time was calculated as 26.1 days (95% CI: 14.4–37.9) for the post-CPR group and 23.9 days (95% CI: 18.6–29.2) for the other ICU group.

However, the median survival time was markedly shorter in the post-CPR group—6 days (95% CI: 1–13), compared to 24 days (95% CI: 11.7–36.2) in the non-CPR ICU group. This difference aligns with an increase in early-phase mortality observed in the survival curve. These findings clearly indicate that post-CPR patients are at a significantly higher risk of early mortality during the ICU stay (

Figure 1).

3.2. Discriminant Analysis for Post-CPR Patients

In previous traditional statistical analyses, several clinical and laboratory parameters were found to significantly differentiate post-CPR patients from other ICU patients. It was also observed that ICU and hospital mortality rates were higher, and median survival times were significantly shorter in the post-CPR group. To identify which parameters distinctly characterize the post-CPR patient profile compared to other ICU patients, a discriminant analysis was performed.

The resulting model was found to be statistically significant (Wilks’ Lambda = 0.522, χ² = 47.814, df = 13, p < 0.001). The canonical correlation coefficient of the model was 0.692, indicating a strong discriminatory power of the discriminant function. The eigenvalue of the function was calculated as 0.917.

Box’s M test result (F = 6.185, p < 0.001) indicated that the variance-covariance matrices were not equal across groups. However, given the equal sample sizes in both groups, this inequality did not substantially affect the model’s reliability.

Among the variables included in the model, the following showed statistically significant differences between the groups: APACHE II score, NUTRIC score, SOFA score, CRP, ALT, GFR, ALP, albumin, MPV, type 2 respiratory failure, and use of inotropic support. Examination of the structure matrix revealed that the variables contributing most to the discriminant function were, in order: inotropic support (r = 0.624), APACHE II score (r = 0.527), NUTRIC score (r = 0.424), and SOFA score (r = 0.417).

The group centroid values for the discriminant function were calculated as +0.946 for post-CPR patients and –0.946 for other ICU patients, indicating a clear separation between the groups by the discriminant function (

Table 4).

As an alternative approach, stepwise discriminant analysis was applied, in which the variables contributing most significantly to the model were automatically selected. As a result of this method, a statistically significant discrimination between the groups was achieved by including only three variables: inotropic support, APACHE II score, and ALP.

This finding suggests that a more parsimonious model can be constructed using a limited number of clinically relevant variables, while still maintaining a discriminatory power comparable to the enter method (Canonical correlation: 0.608,

Table 5). After normalizing the potential multicollinearity effects among the model variables, their respective weights within the model were provided in

Table 6.

3.3. Machine Learning Modeling (Random Forest)

Initially, a Random Forest model was developed to predict mortality among all patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) included in the study. The model was evaluated using a 70% training and 30% testing split across 10 randomized iterations. To address class imbalance, the ADASYN algorithm was applied only to the training sets in each iteration.

For every iteration, performance metrics were calculated on the corresponding test data, and average values were obtained to assess the overall success of the model.

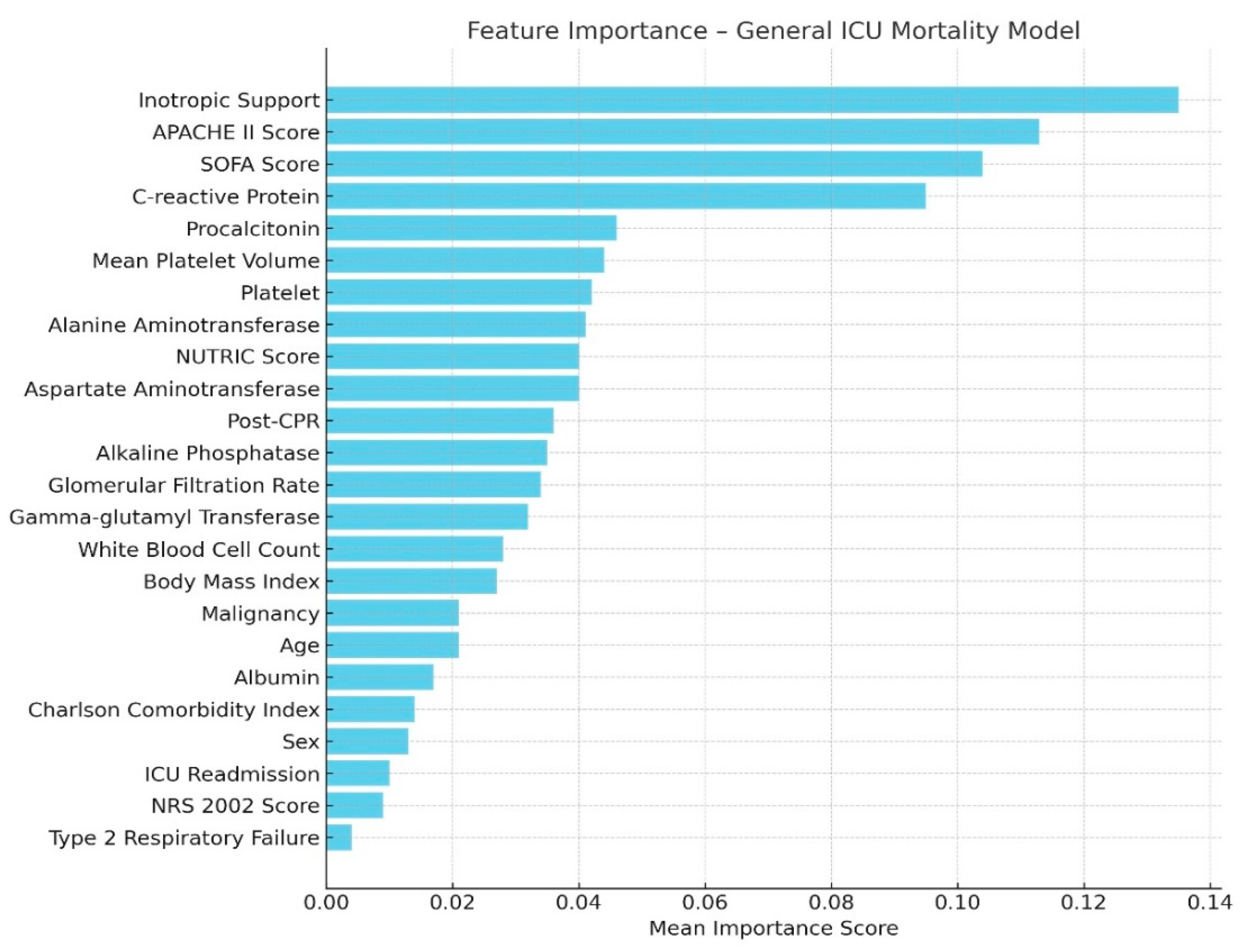

The model achieved an average area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.914 (±0.065), indicating a high discriminatory power in predicting mortality. The average accuracy was 86.4%, precision 94.6%, recall 82.7%, and F1-score 87.9%. These results demonstrate that the model achieved robust classification performance on class-balanced data (

Table 7).

Based on the feature importance rankings, the most influential variables in the model were inotropic support, APACHE II score, CRP level, and SOFA score. Parameters such as AST, ALT, procalcitonin, nutritional scores, and GFR also contributed significantly to the model (

Figure 2).

A separate machine learning model was developed specifically for the post-CPR subgroup, using only real patient data. In this analysis, no synthetic sampling techniques such as ADASYN or SMOTE were applied; instead, the modeling process was conducted exclusively on the existing sample of 41 patients.

The dataset was randomly split 10 times into 70% training and 30% testing sets. For each split, a separate Random Forest classification model was constructed. In each iteration, performance metrics were evaluated on the corresponding test set, and the average of these metrics was calculated to determine the overall model performance (

Table 8).

The average feature importance scores from these models are presented in

Figure 3. Additionally, the average feature importance scores obtained from both machine learning analyses were compared and presented in

Table 9.

3.4. Logistic Regression Analysis

Based on the Random Forest model, a logistic regression analysis was performed using the variables with the highest feature importance in the general model, applying the enter method. This approach was selected to test the consistency of the variables highlighted by the machine learning model with traditional statistical methods.

The model included the following variables: inotropic support, SOFA score, APACHE II score, CRP, procalcitonin, AST, and ALT. The logistic regression analysis indicated that the model had a good overall fit (Hosmer-Lemeshow test p = 0.762) and explained a substantial portion of the variance (Nagelkerke R² = 0.764). The model predicted mortality status with an accuracy rate of 90.2%. Notably, inotropic support was found to be a strong predictor of mortality (OR: 0.014, 95% CI: 0.001–0.163, p < 0.001). In other words, patients who received inotropic support had approximately 71 times higher risk of death compared to those who did not (1 / 0.014 ≈ 71).

A second logistic regression analysis was conducted using the variables with the highest importance scores from the post-CPR Random Forest model, also using the enter method. The variables included in this model were inotropic support, platelet count, MPV, gender, and CRP. The model demonstrated a statistically significant overall fit (Omnibus test, p < 0.001) and a high variance explanation (Nagelkerke R² = 0.787). The Hosmer-Lemeshow test result (p = 1.000) indicated no significant difference between observed and expected mortality outcomes, suggesting a good model fit.

The overall accuracy of the model was 95.1%, with a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 75.0% in predicting mortality. However, none of the variables included in the model reached statistical significance. In particular, the odds ratio calculated for inotropic support was OR: 0.000, 95% CI: 0.000–8312.661, which was not significant due to the high variance. This result suggests that the model’s variables may yield unstable outcomes due to the small sample size.

4. Dıscussıon

In our study, no statistically significant differences were observed between the post-CPR patient group and other ICU patients in terms of age, gender, comorbidities, or presence of malignancy. However, the post-CPR group demonstrated significantly higher NUTRIC scores compared to the other group. No significant difference was found in NRS-2002 scores. Previous studies have shown that the NUTRIC score offers superior predictive ability in ICU settings compared to other nutritional risk scores (20). Moreover, modified NUTRIC scores have been shown to be closely associated with 28-day mortality in ICU patients (21).

Another distinguishing parameter in the post-CPR group was a significantly higher APACHE II score. APACHE II emerged as a prominent predictor of mortality both in the discriminant analysis and in the Random Forest-based machine learning model. A retrospective cohort study conducted in India involving 37 patients who were followed in the ICU after in-hospital cardiac arrest found that higher APACHE II scores were associated with increased mortality (22). Furthermore, a large-scale study using data from 16,940 critically ill patients on mechanical ventilation, where 83% of the dataset was used for model training and 17% for testing, also reported similar findings. In that model, the most significant predictors of 30-day mortality were APACHE II score, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), and the need for norepinephrine—results that are consistent with our model based on a much smaller dataset. In our overall ICU patient model, APACHE II score, inotropic support, CRP, and SOFA score emerged as the most important predictors (23).

We believe that the methodological approach—correct model development, addressing data imbalance using ADASYN, improving learning from borderline samples, and building 10 randomized model iterations with averaged performance from a dataset of 82 patients—contributed to results that are in line with the existing literature.

In our discriminant analysis, which aimed to characterize post-CPR patients in the ICU, the three most defining features were a high APACHE II score, significantly greater need for inotropic support, and elevated ALP levels. A recent and impactful study from 2024 reported that in patients who developed acute liver injury following cardiac arrest, serum ALP levels were identified as an independent predictor of poor prognosis in a retrospective analysis (24).

In the mortality prediction model specifically developed for the post-CPR patient subgroup, some interesting findings emerged. While the APACHE II score ranked among the top predictors in the general model, it appeared to be less influential in the post-CPR subgroup. Instead, MPV, gender, and platelet count surfaced as the top-ranked variables. Notably, the need for inotropic support continued to hold a prominent position even within the mortality prediction of post-CPR patients.

We attribute the diminished importance of the APACHE II score to the fact that all post-CPR patients in our dataset exhibited uniformly high and similar APACHE II scores within the first 24 hours of ICU admission. Supporting this, previous studies analyzing hospital mortality prediction following cardiac arrest through artificial intelligence modeling have shown that AI-based models outperformed APACHE scores alone. In homogeneous patient groups, the APACHE score has been found less effective in discriminating mortality, whereas models incorporating age, gender, and physiological parameters performed better (25).

As for platelet-related variables, the literature presents conflicting evidence regarding platelet count, red cell distribution width (RDW), and MPV. In a study by Cotoia et al., MPV and platelet count were found to be unrelated to mortality in post-cardiac arrest patients. However, another study demonstrated that thrombocytopenia and elevated MPV levels were strongly associated with mortality in ICU patients (26, 27).

Among the traditional statistical findings of our study, procalcitonin and CRP levels were significantly higher in post-CPR patients compared to other ICU patients. It is known that in post-cardiac arrest syndrome, due to the acute inflammatory response triggered by cardiac arrest, an early increase in procalcitonin levels—followed by a delayed rise in CRP—can occur independently of infection. Furthermore, this inflammatory profile has been associated with poor prognosis in this patient population (28, 29).

Both CRP and procalcitonin ranked among the top features in the feature importance list of our Random Forest mortality prediction model for post-CPR patients.

ALT, AST, and GFR values also showed statistically significant differences in post-CPR patients. ALT and AST levels were higher, whereas GFR was lower. These parameters, indicative of multi-organ failure, are expected findings in this patient group and are associated with poor prognosis (30).

The observation that type 2 respiratory failure was less common among post-CPR patients compared to other ICU patients should be interpreted within the context of the hospital where the study was conducted. In this institution, patients with respiratory failure are more frequently monitored and typically respond well to non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIMV) therapy. This may explain why the diagnosis of type 2 respiratory failure was more prevalent in the other ICU patient group.

Albumin levels were also significantly lower in the post-CPR group. This finding is supported by studies indicating that higher serum albumin levels are associated with reduced mortality in post-cardiac arrest patients (31). In our study, both mortality and hypoalbuminemia were notable clinical features within the post-CPR group.

In artificial intelligence modeling, the presence of imbalanced datasets—such as when the number of deceased patients is lower than survivors—can result in models that are biased toward predicting survival. Additionally, if the dataset contains few borderline cases for the variables being studied (e.g., a patient with no inotropic support but a high APACHE II score), and if the model is not well-trained on such instances, its mortality prediction performance can decrease.

Oversampling methods have been proposed in the literature as solutions to these challenges, to be applied prior to statistical analysis. For instance, at the 6th International Conference on Software Engineering and Information Management in 2023, a logistic regression analysis developed using the ADASYN method to model mortality in patients presenting with typical chest pain due to acute myocardial infarction was reported to be the most successful approach (32).

Furthermore, recent collaborative projects between MIT and a medical center in Israel have led to the development of numerous studies utilizing large datasets consisting of thousands of patients’ clinical and laboratory data. Most of these studies are based on machine learning-driven AI models. Even with such large datasets, oversampling techniques such as ADASYN and SMOTE were applied to protect models from the adverse effects of data imbalance and to enhance learning from borderline examples (33).

4.1. Limitations of the Study

This study has several limitations. Most notably, we were unable to include data on the duration of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and the initial cardiac rhythm detected due to significant inconsistencies in these records. Although these variables are recognized as important in the literature, they were excluded from our analysis. Despite conducting a retrospective review of hospital records over a well-documented three-year period, only 41 post-CPR patients met the inclusion criteria.

We excluded out-of-hospital cardiac arrests because we could not reliably differentiate witnessed from unwitnessed arrests. Furthermore, the time required to achieve minimum clinical stabilization during patient transfers from other centers to our ICU made these cases unsuitable for inclusion. Another limitation is the inability to implement targeted temperature management (TTM) at our institution, which may have impacted patient outcomes.

From a statistical and technical perspective, while the models demonstrated high performance metrics, caution is warranted when interpreting their generalizability to real-world clinical settings. The study was conducted on a relatively small sample of 82 patients, which increases the risk of overfitting. Additionally, the number of features included in the models was relatively high compared to the sample size, potentially leading to model overtraining and artificially inflated validation results. In some data splits, an AUC of 1.0 was observed, supporting this concern.

While the model’s robustness was assessed through repeated train-test splits, no subgroup fairness analysis (e.g., by age or sex) was conducted due to limited sample size. This limitation should be addressed in future studies.

Furthermore, although the ADASYN method improved the model’s ability to learn from borderline cases by generating synthetic examples for the minority class, it also introduces the risk of embedding artificial patterns into the training data. This could reduce the model’s performance when applied to real patient populations.

Therefore, external validation is essential in future applications of this model. It should be tested on larger, multicenter patient cohorts to ensure robustness. Additionally, comparative analyses with more simplified models are recommended to more realistically assess the model’s suitability for clinical use.

5. CONCLUSION

Despite the limitations of our study, we believe that this analysis, which focused on post-CPR ICU patients compared to other ICU patients, offers a novel perspective on survival analysis. Although artificial intelligence-supported analyses are becoming increasingly common in medical research, we emphasize the importance of exercising caution regarding the reliability and generalizability of these results.

We describe our study’s methodology as a hybrid approach to mortality analysis. The sequence of “describe–classify–compare–validate” serves as a stepwise validation process in which each stage scrutinizes the preceding one. We believe this approach exemplifies a model of controlled integration of artificial intelligence into the medical literature, where AI use is expanding rapidly.

Our findings indicate that while certain mortality-related factors differ between post-CPR and other ICU patients, active infection/inflammation and the need for inotropic support remain strong predictors of mortality in both groups. When interpreted in conjunction with the literature, we also conclude that clinical scoring systems such as APACHE continue to serve as robust alternative predictors to AI-based models in mortality prediction.

Supplementary Methods

Running the Scripts: To run the code and activate the interactive predictor model, Python must be installed on your computer. To execute the model, open the command prompt and type python “name_of_the_model_file.py” followed by pressing Enter. Once the required input values are entered as prompted by the calculator, the model will generate a mortality prediction at the end. Before running the codes, the CSV file and all related Python scripts should be placed in a single folder. Then, using the command prompt, navigate to the folder by typing cd “folder_name” and pressing Enter. Once inside the correct directory, the scripts can be executed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.M. and G.E.D.; methodology, M.S.P. and D.Ç.; data curation, O.M., M.Ö.C. and M.D.; formal analysis, O.M., E.A. M.A. and K.E.; supervision, O.M. and K.E.; writing—original draft preparation, O.M. and D.Ç.; writing—review and editing, M.B. and A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted with the approval of the Ethics Committee of Ankara Atatürk Sanatorium Training and Research Hospital under decision number 2024-BÇEK/226.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent forms were obtained from all patients, and the study was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability Statement

Data and code sharing: The dataset containing patient information was fully anonymized and shared as a CSV file. Python script files (.py) containing the artificial intelligence models, as well as the discriminant analysis converted from SPSS output to Python code, have also been made available. Additionally, Python scripts used for reporting model performance metrics have been provided.

Conflıct of interest

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nolan, J.P.; Sandroni, C.; Böttiger, B.W.; Cariou, A.; Cronberg, T.; Friberg, H.; Genbrugge, C.; Gueugniaud, P.-Y.; Hahn, R.G.; Haywood, K. Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcome reports: Update of the Utstein Resuscitation Registry Templates. Resuscitation 2019, 144, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Panchal, A.R.; Bartos, J.A.; Cabañas, J.G.; Donnino, M.W.; Drennan, I.R.; Hirsch, K.G.; Kudenchuk, P.J.; Kurz, M.C.; Lavonas, E.J.; Morley, P.T.; et al. 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2020, 142 (Suppl. 2), S366–S468. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schuetz, P.; Wirz, Y.; Sager, R.; Christ-Crain, M.; Stolz, D.; Tamm, M.; Bouadma, L.; Luyt, C.E.; Wolff, M.; Chastre, J.; et al. Procalcitonin to initiate or discontinue antibiotics in acute respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 10, CD007498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wacker, C.; Prkno, A.; Brunkhorst, F.M.; Schlattmann, P. Procalcitonin as a diagnostic marker for sepsis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erenler, A.K.; Yapar, D.; Terzi, Ö. Comparison of procalcitonin and C-reactive protein in differential diagnosis of sepsis and severe sepsis in emergency department. Dicle Med. J. 2017, 44, 175–182. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Silvestre, J.P.; da Cruz Coelho, L.M.; Póvoa, P.M.S.R. Impact of fulminant hepatic failure on C-reactive protein? J. Crit. Care 2010, 25, 657.e7. [Google Scholar]

- Kan, W.-C.; Liu, I.-T.; Lin, Y.-J.; Hsieh, P.-F.; Hsieh, T.-S.; Lin, C.-C.; Chien, C.-C. Predictive ability of procalcitonin for acute kidney injury: A narrative review focusing on the interference of infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iesu, E.; Franchi, F.; Zama Cavicchi, F.; Pozzebon, S.; Fontana, V.; Mendoza, M.; Nobile, L.; Scolletta, S.; Vincent, J.L.; Creteur, J.; et al. Acute liver dysfunction after cardiac arrest. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, K.K.; Rasmussen, S.B.; Kjaergaard, J.; Schmidt, H.; Mølstrøm, S.; Beske, R.P.; Grand, J.; Ravn, H.B.; Winther-Jensen, M.; Meyer, M.A.S.; et al. Acute kidney injury after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Crit. Care 2024, 28, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardon-Bounes, F.; Gratacap, M.P.; Groyer, S.; Ruiz, S.; Georges, B.; Seguin, T.; Garcia, C.; Payrastre, B.; Conil, J.M.; Minville, V. Kinetics of mean platelet volume predicts mortality in patients with septic shock. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ari, M.; Akinci Ozyurek, B.; Yildiz, M.; Ozdemir, T.; Hosgun, D.; Sahin Ozdemirel, T.; Ensarioglu, K.; Erdogdu, M.H.; Eraslan Doganay, G.; Doganci, M.; et al. Mean platelet volume-to-platelet count ratio (MPR) in acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A novel biomarker for ICU mortality. Medicina 2025, 61, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimmer, E.; Pandya, A.; Sinclair, S.; Pannu, N.; Stelfox, H.T.; Bagshaw, S.M. White blood cell count trajectory and mortality in septic shock: A historical cohort study. Can. J. Anesth. 2022, 69, 1230–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, N.; Ohashi, W.; Sakanashi, D.; Suematsu, H.; Kato, H.; Hagihara, M.; Yamagishi, Y.; Mikamo, H. Combination of sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score and Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) could predict the severity and prognosis of candidemia more accurately than the acute physiology, age, chronic health evaluation II (APACHE II) score. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Qin, Z.; Liu, H.; Shang, N.; Wang, Y.; Xi, X. Clinical value of nutritional risk scores in patients with sepsis associated acute renal injury. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue 2022, 34, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seppä, A.M.J.; Skrifvars, M.B.; Vuopio, H.; Raj, R.; Reinikainen, M.; Pekkarinen, P.T. Association of white blood cell count with one-year mortality after cardiac arrest. Resusc. Plus 2024, 20, 100816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, G.; Lin, K.; Hu, Y. Using machine learning methods to predict in-hospital mortality of sepsis patients in the ICU. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2020, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.T.; Kim, D.K.; Kim, H.; Kim, D.J. A comparison of oversampling methods for constructing a prognostic model in the patient with heart failure. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC); IEEE: Jeju, Republic of Korea, 2020; pp. 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, A.R.; Banerjee, S.; Naik, S. Effect of different oversampling techniques to handle class imbalance challenges in coronary heart disease prediction. In Proceedings of the 2024 Global Conference on Communications and Information Technologies (GCCIT); IEEE: Tokyo, Japan, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins GS, Moons KGM, Dhiman P, Riley RD, Beam AL, Van Calster B, Kruizinga MD, Wynants L, Keane PA, Stryjewska-Hrycko A, et al. TRIPOD+AI statement: Updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ 2024, 385, e078378. [CrossRef]

- de Vries, M.C.; Koekkoek, W.A.C.; Opdam, M.H.; van Blokland, D.; van Zanten, A.R. Nutritional assessment of critically ill patients: Validation of the modified NUTRIC score. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, A.; Henry, J.; Ong, V.; Leong, C.S.F.; Teh, A.L.; van Dam, R.M.; Kowitlawakul, Y. Association of modified NUTRIC score with 28-day mortality in critically ill patients. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 1143–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, K.D.; Rai, N.; Aggarwal, R.; Trikha, A. Outcomes of trauma victims with cardiac arrest who survived to intensive care unit admission in a level 1 apex Indian trauma centre: A retrospective cohort study. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 25, 1408–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kwon, Y.; Baek, M.S. Machine learning models to predict 30-day mortality in mechanically ventilated patients. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Lin, L.; Sun, C.; Chen, L.; Lv, W. Association between serum alkaline phosphatase and clinical prognosis in patients with acute liver failure following cardiac arrest: A retrospective cohort study. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanayakkara, S.; Fogarty, S.; Tremeer, M.; Ross, K.; Richards, B.; Bergmeir, C.; Xu, S.; Stub, D.; Smith, K.; Tacey, M.; et al. Characterising risk of in-hospital mortality following cardiac arrest using machine learning: A retrospective international registry study. PLoS Med. 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotoia, A.; Franchi, F.; De Fazio, C.; Vincent, J.; Creteur, J.; Taccone, F. Platelet indices and outcome after cardiac arrest. BMC Emerg. Med. 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, M.; Uludağ, Ö. Can platelet count and mean platelet volume and red cell distribution width be used as a prognostic factor for mortality in intensive care unit? Cureus 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annborn, M.; Dankiewicz, J.; Erlinge, D.; Hertel, S.; Rundgren, M.; Smith, J.G.; Struck, J.; Friberg, H. Procalcitonin after cardiac arrest—an indicator of severity of illness, ischemia-reperfusion injury and outcome. Resuscitation 2013, 84, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beumier, M.; Cortez, D.O.; Donadello, K.; Vincent, J.L.; Taccone, F.S. CRP levels after cardiac arrest. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 40, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, S.; Peng, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, D.J. High plasma levels of pro-inflammatory factors interleukin-17 and interleukin-23 are associated with poor outcome of cardiac-arrest patients: A single center experience. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; She, Y.; Mo, W.; Jin, B.; Xiang, W.; Luo, L. Albumin level at admission to the intensive care unit is associated with prognosis in cardiac arrest patients. Cureus 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Waqar, M.M.; Arif, S.; Sherazi, S.W.A.; Son, S.H.; Lee, J.Y. An explainable machine learning-based prediction model for in-hospital mortality in acute myocardial infarction patients with typical chest pain. Proc. Int. Conf. Softw. Eng. Inf. Manag. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, M. Mortality Prediction of ICU Patients with Rheumatic Heart Disease Using Machine Learning on Imbalanced Data. AIMS Bioinf. Data Integr. 2024, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).