Submitted:

06 October 2025

Posted:

07 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sickle Mouse Lung Tissues

2.2. Human Pulmonary Artery Endothelial Cells (HPAECs)

2.3. Assessment of PH in MALAT1-Overpressing Sickle Cell Mice

2.4. Reagents

2.5. Cell-Based Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

2.6. MALAT1 Loss or Gain of Function

2.7. HMOX1 siRNA

2.8. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining

2.9. Messenger RNA Stability Assay

2.10. Messenger RNA Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR) Analysis

2.11. Western Blot Analysis

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

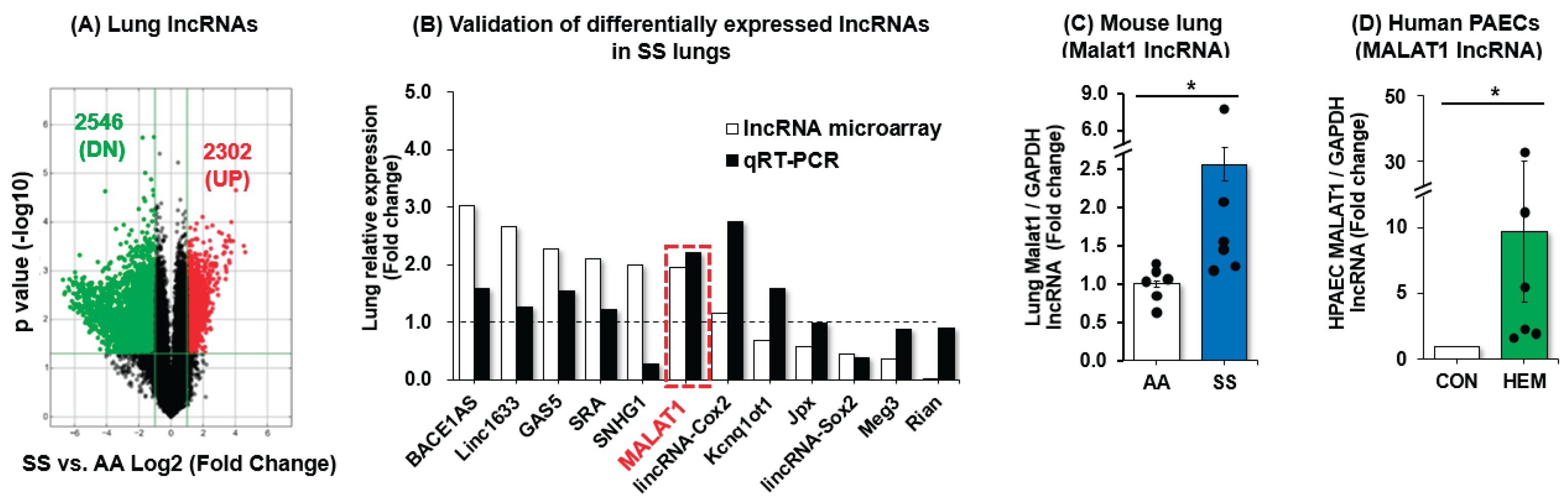

3.1. MALAT1 Expression Is Increased in SS Mouse Lungs and in Hemin-Treated HPAECs

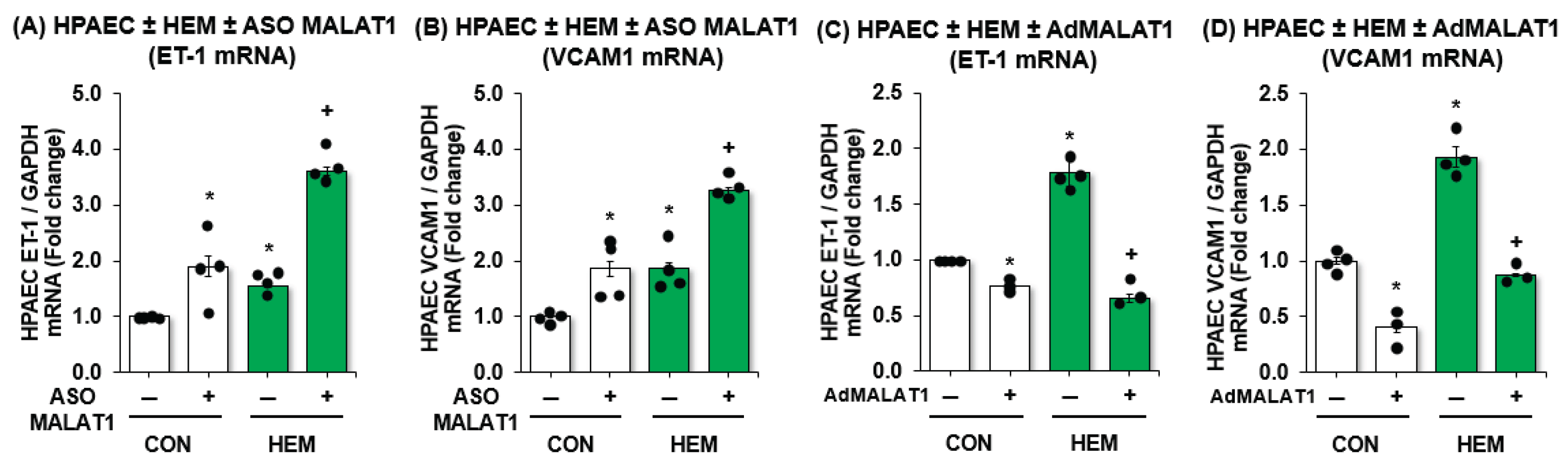

3.2. MALAT1 Regulates Expression of Endothelial Dysfunction Markers ET-1 and VCAM1 In Vitro

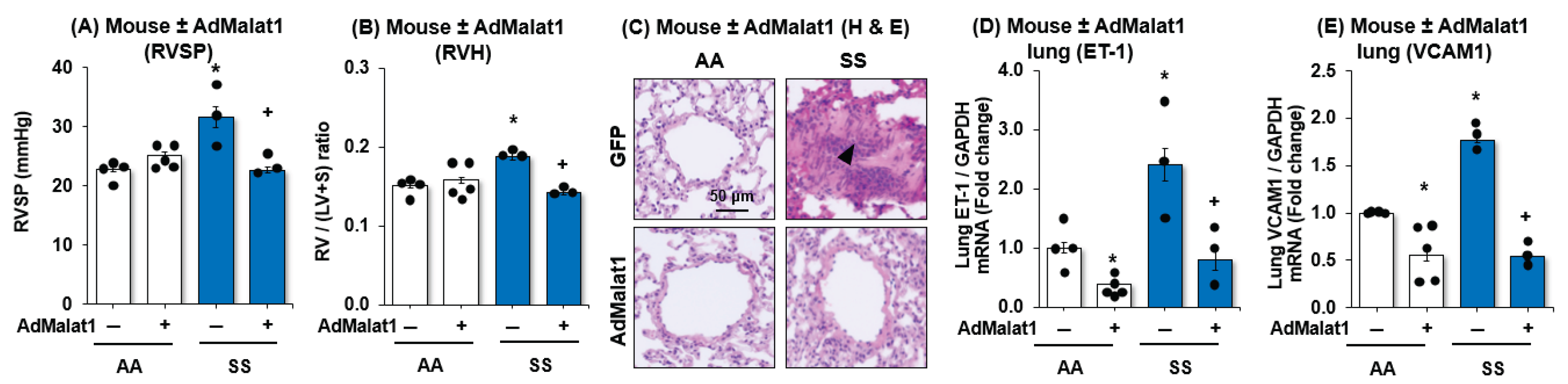

3.3. MALAT1 Overexpression Reduces PH, RVH, and Vascular Remodeling with Downregulation of Endothelial Cells Dysfunction Markers, ET-1 and VCAM1

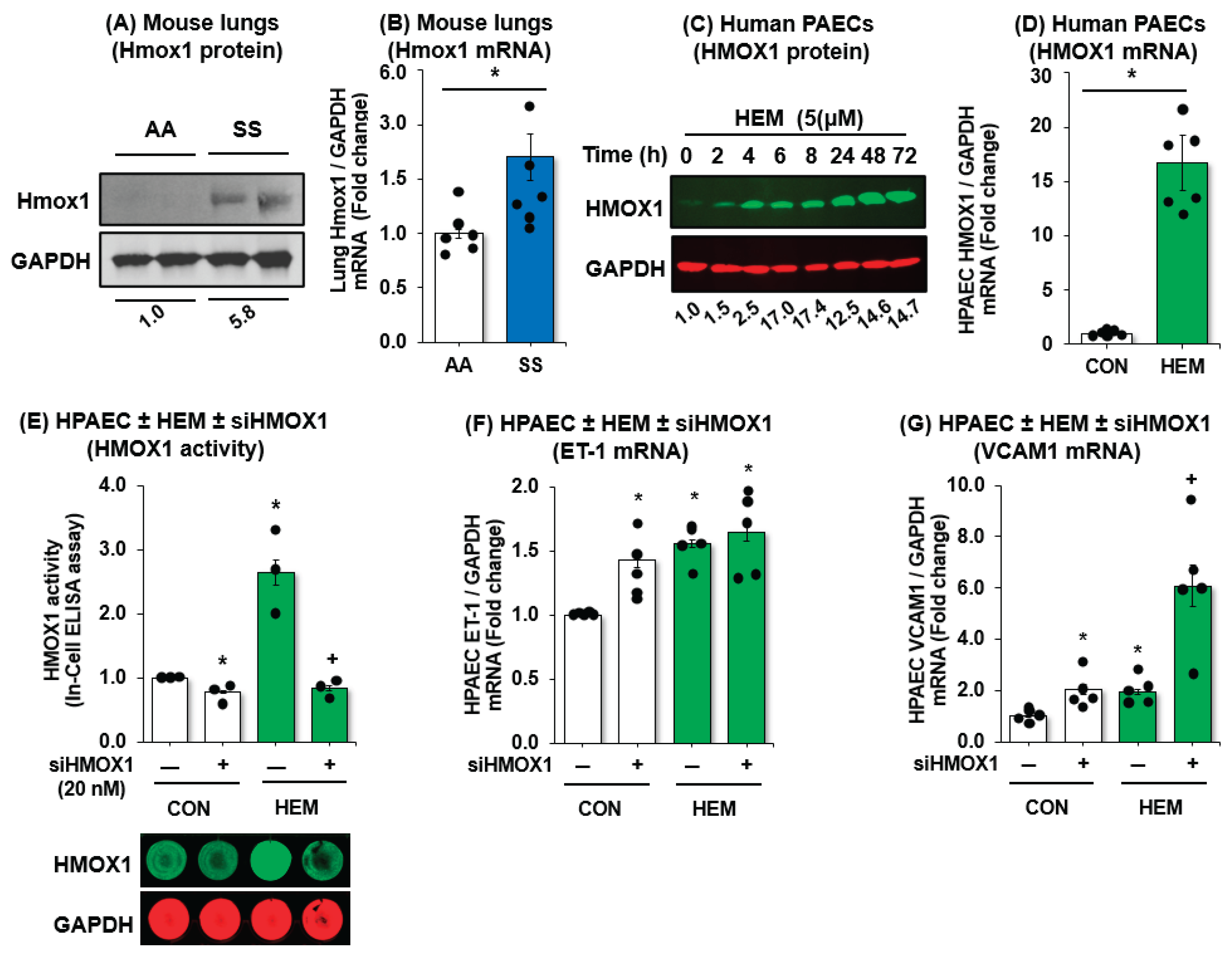

3.4. HMOX1 Protects Endothelial Function in SCD-PH

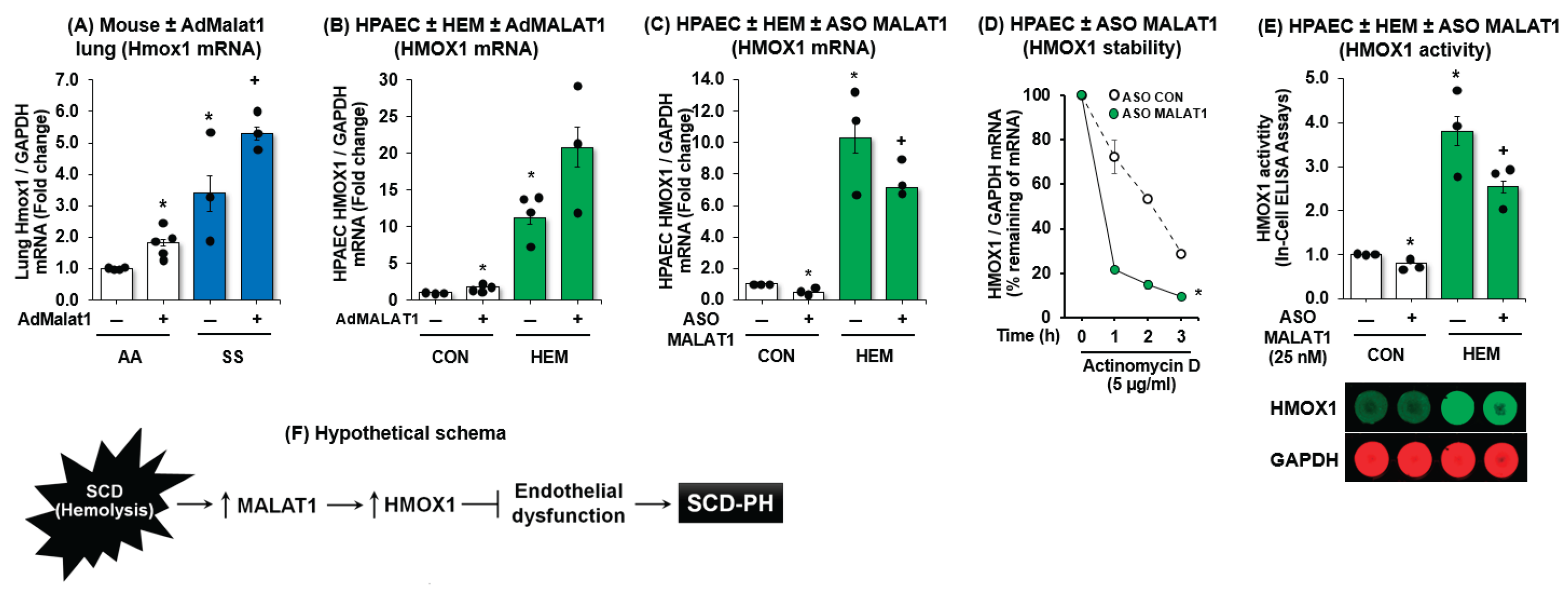

3.5. MALAT1 Regulates HMOX1 Expression

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PH | Pulmonary hypertension |

| SCD | Sickle Cell Disease |

| MALAT1 | Metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 |

| SS | Sickle cell |

| HMOX1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

| lncRNAs | Long non-coding RNAs |

| AA | Littermate controls |

| HPAECs | Human pulmonary artery endothelial cells |

| VCAM1 | Vascular endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 |

| RVH | Right ventricular hypertrophy |

| ASO | Antisense oligonucleotide |

| ET-1 | Endothelin-1 |

| HEM | Hemin |

| RVSP | Right ventricular systolic pressure |

References

- Lilienfeld, D.E.; Rubin, L.J. Mortality from Primary Pulmonary Hypertension in the United States, 1979–1996. Chest 2000, 117, 796–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platt, O.S.; Brambilla, D.J.; Rosse, W.F.; Milner, P.F.; Castro, O.; Steinberg, M.H.; Klug, P.P. Mortality in Sickle Cell Disease—Life Expectancy and Risk Factors for Early Death. New Engl. J. Med. 1994, 330, 1639–1644. [Google Scholar]

- Powars, D.; A Weidman, J.; Odom-Maryon, T.; Niland, J.C.; Johnson, C. Sickle cell chronic lung disease: prior morbidity and the risk of pulmonary failure. Medicine (Baltimore) 1988, 67, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rees, D.C.; Williams, T.N.; Gladwin, M.T. Sickle-Cell Disease. Lancet 2010, 376, 2018–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bensinger, T.A.; Gillette, P.N. Hemolysis in Sickle Cell Disease. Arch Intern Med 1974, 133, 624–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaid, A.; Yanagisawa, M.; Langleben, D.; Michel, R.P.; Levy, R.; Shennib, H.; Kimura, S.; Masaki, T.; Duguid, W.P.; Stewart, D.J. Expression of Endothelin-1 in the Lungs of Patients with Pulmonary Hypertension. New Engl. J. Med. 1993, 328, 1732–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, V.V.; McGoon, M.D. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Circulation 2006, 114, 1417–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.J.; Levy, R.D.; Cernacek, P.; Langleben, D. Increased Plasma Endothelin-1 in Pulmonary Hypertension: Marker or Mediator of Disease? Ann. Intern. Med. 1991, 114, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshibayashi, M.; Nishioka, K.; Nakao, K.; Saito, Y.; Matsumura, M.; Ueda, T.; Temma, S.; Shirakami, G.; Imura, H.; Mikawa, H. Plasma endothelin concentrations in patients with pulmonary hypertension associated with congenital heart defects. Evidence for increased production of endothelin in pulmonary circulation. Circulation 1991, 84, 2280–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerman, S.I.; Kourembanas, S.; Conca, T.J.; Tucci, M.; Brauer, M.; Farber, H.W. Endothelin-1 Production during the Acute Chest Syndrome in Sickle Cell Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1997, 156, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybicki, A.C.; Benjamin, L.J. Increased Levels of Endothelin-1 in Plasma of Sickle Cell Anemia Patients. Blood 1998, 92, 2594–2596. [Google Scholar]

- Werdehoff, S.G.; Moore, R.B.; Hoff, C.J.; Fillingim, E.; Hackman, A.M. Elevated plasma endothelin-1 levels in sickle cell anemia: Relationships to oxygen saturation and left ventricular hypertrophy. Am. J. Hematol. 1998, 58, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, M.; Kurihara, H.; Kimura, S.; Tomobe, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Mitsui, Y.; Yazaki, Y.; Goto, K.; Masaki, T. A novel potent vasoconstrictor peptide produced by vascular endothelial cells. Nature 1988, 332, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minniti, C.P.; Machado, R.F.; Coles, W.A.; Sachdev, V.; Gladwin, M.T.; Kato, G.J. Endothelin receptor antagonists for pulmonary hypertension in adult patients with sickle cell disease. Br. J. Haematol. 2009, 147, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthanveetil, P.; Gutschner, T.; Lorenzen, J. MALAT1: A Therapeutic candidate for a broad spectrum of vascular and cardiorenal complications. Hypertens. Res. 2020, 43, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Ma, L. New Insights into Long Non-Coding RNA MALAT1 in Cancer and Metastasis. Cancers 2019, 11, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaé, N.; Heumüller, A.W.; Fouani, Y.; Dimmeler, S. Long non-coding RNAs in vascular biology and disease. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2019, 114, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Moráňová, L.; Bartošík, M. Long Non-Coding RNAs – Current Methods of Detection and Clinical Applications. Klin. Onkol. 2019, 32, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunch, H. Gene regulation of mammalian long non-coding RNA. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2018, 293, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Jing, F.; Yi, W.; Mendelson, A.; Shi, P.; Walsh, R.; Friedman, D.F.; Minniti, C.; Manwani, D.; Chou, S.T.; et al. Ho-1(Hi) Patrolling Monocytes Protect against Vaso-Occlusion in Sickle Cell Disease. Blood 2018, 131, 1600–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yachie, A. Heme Oxygenase-1 Deficiency and Oxidative Stress: A Review of 9 Independent Human Cases and Animal Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yet, S.-F.; Perrella, M.A.; Layne, M.D.; Hsieh, C.-M.; Maemura, K.; Kobzik, L.; Wiesel, P.; Christou, H.; Kourembanas, S.; Lee, M.-E. Hypoxia induces severe right ventricular dilatation and infarction in heme oxygenase-1 null mice. J. Clin. Investig. 1999, 103, R23–R29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minamino, T.; Christou, H.; Hsieh, C.-M.; Liu, Y.; Dhawan, V.; Abraham, N.G.; Perrella, M.A.; Mitsialis, S.A.; Kourembanas, S. Targeted expression of heme oxygenase-1 prevents the pulmonary inflammatory and vascular responses to hypoxia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 8798–8803. [Google Scholar]

- Lanaro, C.; Franco-Penteado, C.F.; Albuqueque, D.M.; O Saad, S.T.; Conran, N.; Costa, F.F. Altered levels of cytokines and inflammatory mediators in plasma and leukocytes of sickle cell anemia patients and effects of hydroxyurea therapy. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2009, 85, 235–242. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S.; Tan, F.; Yu, T.; Li, Y.; Adisa, O.; Mosunjac, M.; Ofori-Acquah, S.F. Global Gene Expression Profiling of Endothelium Exposed to Heme Reveals an Organ-Specific Induction of Cytoprotective Enzymes in Sickle Cell Disease. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e18399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.-C.; Sun, C.-W.; Ryan, T.M.; Pawlik, K.M.; Ren, J.; Townes, T.M. Correction of sickle cell disease by homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells. Blood 2006, 108, 1183–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.-Y.; Park, K.; Kleinhenz, J.M.; Murphy, T.C.; Sutliff, R.L.; Archer, D.; Hart, C.M. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Regulates the V-Ets Avian Erythroblastosis Virus E26 Oncogene Homolog 1/Microrna-27a Axis to Reduce Endothelin-1 and Endothelial Dysfunction in the Sickle Cell Mouse Lung. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2017, 56, 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbet, R.E.; Bland, J.M.; Kleinhenz, D.J.; Mitchell, P.O.; Walp, E.R.; Sutliff, R.L.; Hart, C.M. Rosiglitazone Attenuates Chronic Hypoxia–Induced Pulmonary Hypertension in a Mouse Model. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2010, 42, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.Y.; Park, K.K.; Kleinhenz, J.M.; Murphy, T.C.; Green, D.E.; Bijli, K.M.; Yeligar, S.M.; Carthan, K.A.; Searles, C.D.; Sutliff, R.L.; Hart, C.M. Ppargamma Activation Reduces Hypoxia-Induced Endothelin-1 Expression through Upregulation of Mir-98. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, B.-Y.; Kleinhenz, J.M.; Murphy, T.C.; Hart, C.M.; Silpanisong, J.; Kim, D.; Williams, J.M.; Adeoye, O.O.; Thorpe, R.B.; Pearce, W.J.; et al. The Ppargamma Ligand Rosiglitazone Attenuates Hypoxia-Induced Endothelin Signaling in Vitro and in Vivo. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2011, 301, L881–L891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, A.J.; Chang, S.S.; Park, C.; Lee, C.M.; Benza, R.L.; Passineau, M.J.; Ma, J.; Archer, D.R.; Sutliff, R.L.; Hart, C.M.; Kang, B.Y. Ppargamma Increases Huwe1 to Attenuate Nf-Kappab/P65 and Sickle Cell Disease with Pulmonary Hypertension. Blood Adv 2021, 5, 399–413. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, S.A.; Ahmad, S.M.; Mumtaz, P.T.; Malik, A.A.; Dar, M.A.; Urwat, U.; Shah, R.A.; Ganai, N.A. Long non-coding RNAs: Mechanism of action and functional utility. Non-coding RNA Res. 2016, 1, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, P.; Diederichs, S.; Wang, W.; Böing, S.; Metzger, R.; Schneider, P.M.; Tidow, N.; Brandt, B.; Buerger, H.; Bulk, E.; et al. MALAT-1, a novel noncoding RNA, and thymosin β4 predict metastasis and survival in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene 2003, 22, 8031–8041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Zhang, P.; Li, G.; Xie, Q.; Cheng, Y. Functional Polymorphism of Lncrna Malat1 Contributes to Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Susceptibility in Chinese People. Clin Chem Lab Med 2017, 55, 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, M.; Schuoler, C.; Leuenberger, C.; Bühlmann, C.; Haider, T.J.; Vogel, J.; Ulrich, S.; Gassmann, M.; Kohler, M.; Huber, L.C. Analysis of hypoxia-induced noncoding RNAs reveals metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 as an important regulator of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Exp. Biol. Med. 2017, 242, 487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Kurakula, K.; Smolders, V.F.E.D.; Tura-Ceide, O.; Jukema, J.W.; Quax, P.H.A.; Goumans, M.-J. Endothelial Dysfunction in Pulmonary Hypertension: Cause or Consequence? Biomedicines 2021, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabinovitch, M. Molecular pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 2372–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.L.; Champion, H.C.; Campbell-Lee, S.A.; Bivalacqua, T.J.; Manci, E.A.; Diwan, B.A.; Schimel, D.M.; Cochard, A.E.; Wang, X.; Schechter, A.N.; et al. Hemolysis in sickle cell mice causes pulmonary hypertension due to global impairment in nitric oxide bioavailability. Blood 2007, 109, 3088–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Nguyen, J.; Abdulla, F.; Nelson, A.T.; Beckman, J.D.; Vercellotti, G.M.; Belcher, J.D. Soluble MD-2 and Heme in Sickle Cell Disease Plasma Promote Pro-Inflammatory Signaling in Endothelial Cells. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 632709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potoka, K.P.; Gladwin, M.T. Vasculopathy and pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2015, 308, L314–L324. [Google Scholar]

- Reiter, C.D., X. Wang, J.E. Tanus-Santos, N. Hogg, R.O. Cannon, 3rd, A.N. Schechter, and M. T. Gladwin. Cell-Free Hemoglobin Limits Nitric Oxide Bioavailability in Sickle-Cell Disease. Nat Med 2002, 8, 1383-9. [Google Scholar]

- Abid, S.; Kebe, K.; Houssaïni, A.; Tomberli, F.; Marcos, E.M.; Bizard, E.M.; Breau, M.M.; Parpaleix, A.; Tissot, C.-M.; Maitre, B.; et al. New Nitric Oxide Donor NCX 1443: Therapeutic Effects on Pulmonary Hypertension in the SAD Mouse Model of Sickle Cell Disease. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2018, 71, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, O.D.; Mitsialis, S.A.; Chang, M.S.; Vergadi, E.; Lee, C.; Aslam, M.; Fernandez-Gonzalez, A.; Liu, X.; Baveja, R.; Kourembanas, S. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Expressing Heme Oxygenase-1 Reverse Pulmonary Hypertension. Stem Cells 2011, 29, 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Solari, V.; Piotrowska, A.P.; Puri, P. Expression of heme oxygenase-1 and endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the lung of newborns with congenital diaphragmatic hernia and persistent pulmonary hypertension. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2003, 38, 808–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckman, J.D.; Chen, C.; Nguyen, J.; Thayanithy, V.; Subramanian, S.; Steer, C.J.; Vercellotti, G.M. Regulation of Heme Oxygenase-1 Protein Expression by miR-377 in Combination with miR-217. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 3194–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Tian, Q.; Steuerwald, N.M.; Schrum, L.W.; Bonkovsky, H.L. The let-7 microRNA enhances heme oxygenase-1 by suppressing Bach1 and attenuates oxidant injury in human hepatocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012, 1819, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar]

- Pulkkinen, K.H.; Ylä-Herttuala, S.; Levonen, A.-L. Heme oxygenase 1 is induced by miR-155 via reduced BACH1 translation in endothelial cells. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51, 2124–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Shen, H.; Huang, Q.; Li, Q. The Circular Rna Cdr1as Regulates the Proliferation and Apoptosis of Human Cardiomyocytes through the Mir-135a/Hmox1 and Mir-135b/Hmox1 Axes. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomarkers 2020, 24, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).