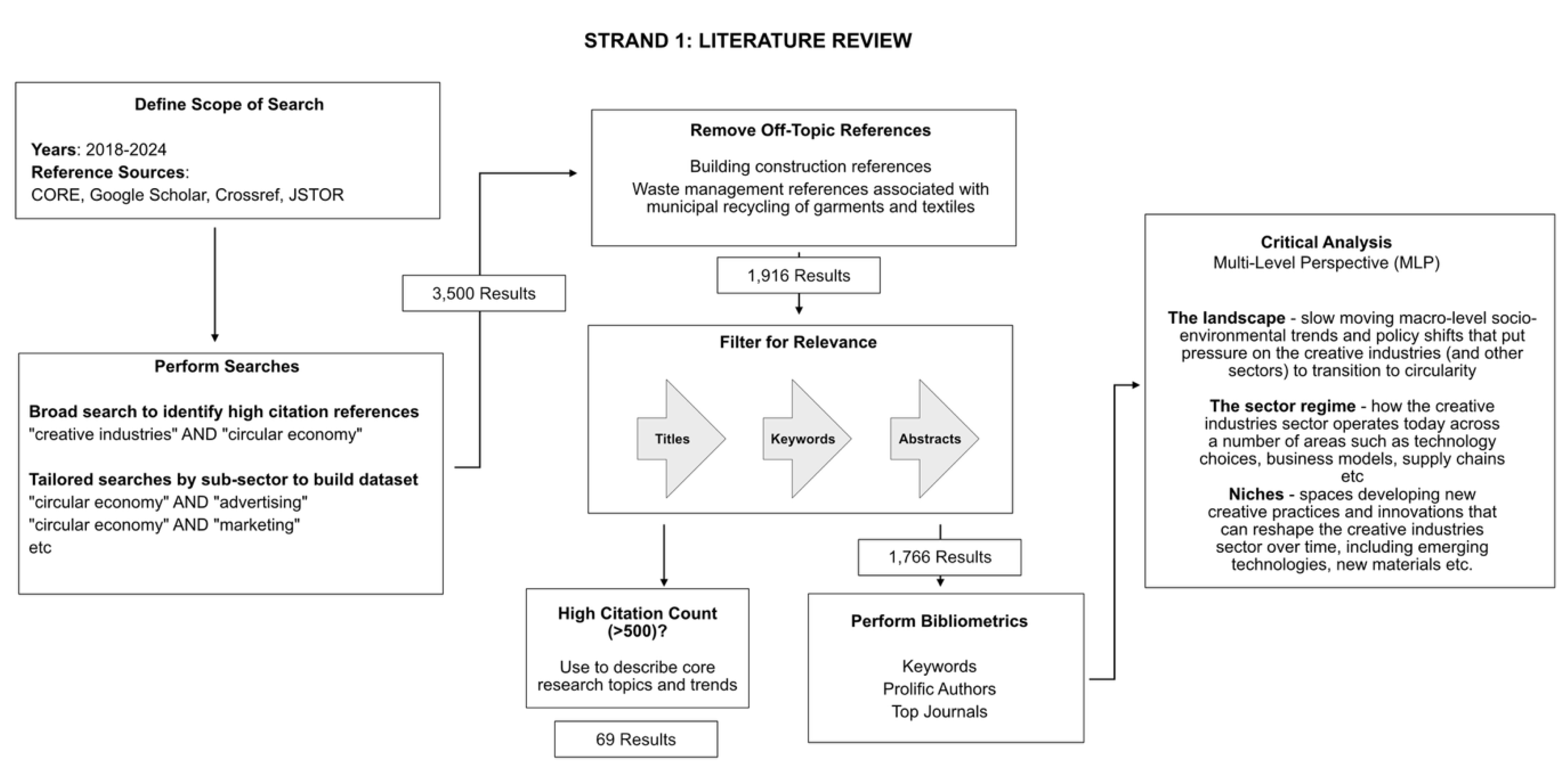

3.1. Review and Analysis of Recent Literature

An initial broad search (“creative industries” AND “circular economy”) was performed to identify highly cited articles relevant to the CE and to establish how they relate to the creative industries. For the period 2018 to 2024, 69 references were found with 500 or more citations. In these highly cited references, mention of the creative industries is usually confined to a single sentence or repeated mentions of product design, fashion, or architecture, etc. However, by being highly cited, these references exert influence on those researching the creative industries as these papers shape the current core intellectual structure of CE scholarship for multiple sectors, particularly as it relates to policy, practice, business models, and enabling technologies. Many are literature reviews, framework papers, or conceptual critiques (e.g., "Circular economy: the concept and its limitations" [

34], "The relevance of circular economy practices to the sustainable development goals" [

35].

Next, a more tailored search strategy was employed at a creative industries sub-sector level (e.g., advertising). This involved numerous Boolean keyword searches across multiple academic search engines using inclusion and exclusion logic to return more relevant material. These more precise searches yielded 1766 journal articles, book chapters, and textbooks that were highly relevant to at least one sub-sector in the creative industries.

The overall trend in publication is upward (see

Figure 4), with a small drop in 2024, which may be due to incomplete data due to reporting lags. Design (product and fashion) dominates the literature, accounting for almost half of the references.

Table 2 shows the distribution of references by sub-sector and year. In some cases, the sub-sector has been split into the different segments which reveals an interesting trend such as a different rate or volume of publication (e.g., design has been split into design - mostly product and associated material selection - and fashion design, which includes textile design).

When interpreting these publication statistics, it is important to note that references from the construction (building) and the waste management literature associated with municipal recycling of garments and textiles were excluded from these searches, as they are out of scope for the purposes of this paper.

Both advertising and marketing are relatively flat year-on-year, but the volume in marketing is higher. These marketing references are mostly concerned with consumer behaviour and pricing related to the CE. Architecture appears to have peaked in 2021, with a steady decline since then (and a sharp drop in 2024), although this may simply be a lag in the publication process. Creative technology shows a stable upward trend with small year-on-year increases. Performing arts (theatre and dance) and crafts show marked increases in the last two years. Publishing does not appear to be an area of research.

Cross-sector references (e.g., such as those that study adoption of one of the 12R strategies in multiple sub-sectors, or between the creative industries and another sector) are characterised by low and inconsistent activity. This is an important observation as it either means i) there is a lack of dedicated scholarship on the creative industries as a whole; or ii) researchers are funded to work within sub-sector boundaries; or iii) the research on the sector is occurring but is subsumed under the dominant sub-sector or R strategy in reporting.

Table 3 lists the top 20 keywords in the CE in the creative industry dataset. Where references were not supplied with the original reference, keywords were machine-generated.

Table 4 lists the top 20 keyword co-occurrences in the dataset.

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4 suggest that the bulk of the literature is focused on the design, architecture, and fashion sub-sectors. Topic modelling of article titles analysis [

36] highlights a strong focus on circular design, product development, and product-service systems [

37,

38,

39] particularly in fashion and architecture. There is also significant attention to business models, digital innovation, and data-driven value creation, with multiple studies examining how Industry 4.0 technologies like digital twins and blockchain support circular supply chains and services in the creative industries [

13,

40,

41,

42].

Within the design references, there is a distinct sub-cluster around material innovation (for architecture, products, packaging, and fashion), much of which discusses moving to bio-based materials and the implications for designers and architects [

43,

44].

Another cluster centres on consumer engagement, behaviour change, and secondary markets [

45,

46], reflecting interest in how end users participate in circular practices, particularly again in the fashion sub-sector. Cultural narratives and storytelling also emerge as mechanisms for promoting awareness and transition [

47], and this intersects with work on social responsibility, equity, and community mending cultures [

48,

49].

A further thematic area addresses policy frameworks, regulation, and governance, especially at the European level [

50,

51,

52]. These papers discuss the alignment (or misalignment) between public policy and citizen engagement, the role of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and evolving standards and legislation supporting CE transitions.

There is also a prominent strand of papers that cluster together research on systemic perspectives and technical tools aimed at understanding circularity. At the higher level, researchers on systems-level thinking frame how the creative industries can be analysed in terms of interconnections, boundaries, and feedback loops [

53]. At the more applied level, the research offers critiques of life cycle assessment, material flow analysis, and circularity metrics within sub-sectors such as architecture and media streaming as ways to measure circular performance at product and organisational scales [

53,

54,

55].

Creative technology appears last in the top 20 keywords list, but the topic analysis identifies a growing discourse around technological transformation, including discussion of the environmental benefits of AI and digital platforms [

56,

57]. However, there is relatively little discussion of the negative environmental impacts of these technologies in the dataset [

58]. This lack of coverage is likely due to the speed with which energy-intensive technologies such as blockchain and Generative AI have become a feature of the creative industries.

3.1.1. Applying the MLP Lens

At a landscape level, these references reflect the broad forces shaping change in the creative industries (and many other sectors): global policy agendas related to the climate crisis and sustainable consumption and production (e.g., the UN SDGs), challenges of material waste and scarcity, and digital transformation reshaping multiple sectors.

At a sector regime level, the literature suggests that multiple elements of the regime are starting to come under pressure in various sub-sectors to move away from linear practices, e.g., changes in sourcing practices, leadership behaviour in theatre management, and the criteria used by commissioners of advertising and TV content. There are references to dominant institutions (such as major broadcasters and streamers, architectural practices, creative agencies, theatre) circularity metrics, lifecycle assessments, and systems thinking. However, the transition to circularity appears to be only just starting, and there are clusters of papers that discuss slow progress and inertia in the sector as a whole. Continued reliance on linear models in fashion, architecture, and product design is evident in titles that highlight "barriers" and "challenges”. In summary, the regime is adapting incrementally.

At a niche level, there is evidence of potential radical innovations in specific sub-sectors in the references analysed. The literature contains many and varied examples of small-scale experiments, proofs of concept, and entrepreneurial startups. Examples of niche innovations include:

Product and service design: numerous titles refer to "circular product design" and "design for deconstruction" as niche experiments in new forms of design beyond eco-design.

Digital tools and platforms. Mentions of "digital twins" and “virtual and augmented reality” show early-stage integration of technology in circular creative workflows.

Material experimentation. Emerging concepts like “urban mining” for reuse of architectural materials and bio-based materials for fashion show strong niche level explorations of alternatives to consumption of primary resources and those derived from fossil fuels.

However, there is little evidence of these innovations reaching a scale where linear systems are transformed into circular ones. Although not specifically addressing circularity, the written evidence given to the UK House of Lords Communications and Digital Committee by the authors and others in the context of scaling creative technologies echoes this finding [

59].

3.1.2. Authors and Sources

It can take a few years for papers to build up high citation counts, so another way to understand the emerging shape of the literature is to identify individuals whose work appears frequently in the dataset (and where their work is published), which can suggest recurring perspectives, themes, or methodological approaches that may influence trends in the literature.

Table 5 shows authors with five or more references between 2018 and 2024, and

Table 6 shows the leading journals, conferences, and textbooks in that period. Paper counts are based solely on the inclusion and exclusion criteria used in this study and do not necessarily reflect total career output or overall productivity.

40% of the papers published are design-related, covering:

Design-led circular strategies. This cluster of references focuses on design-thinking, innovation, and industry transformation. Fashion and textiles are commonly mentioned.

Product and service design for circularity across creative industries sub-sectors. These references critique case studies and design interventions that build systemic circularity in architecture, product design, and fashion systems.

Circular design and behaviour change in creative production. These references address the CE across multiple sub-sectors. This cluster of references also contains reflections on post-Covid behaviour changes (e.g., the impact on sharing behaviour).

20% of the papers discuss Industry 4.0 and digital enablers of CE adoption in the creative industries (e.g., the use of simulation models for process design). There is a lack of sub-sector level research: most of the papers are at a general level within the creative industries, with fashion being one of the few sub-sectors to attract significant research.

The remaining references mostly cover green supply chains, benefits of platform-based systems, business model innovation, and challenges and frameworks for implementing CE strategies in the creative industries.

There are numerous similarities between the high frequency authors’ areas of interest and those of the highly cited authors. In comparison with highly cited papers, frequently occurring authors are more likely to write about the challenges of orchestration and integration of CE practices, especially in creative industries business contexts. The high frequency authors, however, are less likely to write about European policy, UN SDGs, and alignment of governance frameworks.

Table 5.

Authors with five or more references in the dataset. Note that this list contains only the number of references pertaining to the creative industries and not the entire output of each author.

Table 5.

Authors with five or more references in the dataset. Note that this list contains only the number of references pertaining to the creative industries and not the entire output of each author.

| Author |

ORCID ID |

Primary Affiliation |

Reference Count in Dataset |

| Bakker, C |

0000-0001-9982-8788 |

TUDelft, Netherlands |

20 |

| Balkenende, R |

Not Available |

LLeiden-Delft-Erasmus Universities |

14 |

| Pigosso, D |

0000-0001-7277-0360 |

Technical University of Denmark, DTU |

13 |

| McAloone, T |

0000-0002-9776-3340 |

Technical University of Denmark, DTU |

11 |

| Bocken, N |

0000-0003-0137-4074 |

Maastricht University, Netherlands |

10 |

| Garza-Reyes, JA |

0000-0002-5493-877X |

University of Derby, United Kingdom |

8 |

| Zorpas, A |

0000-0002-8154-5656 |

Open University of Cyprus |

7 |

| Sarkis, J |

0000-0003-0143-804X |

Worcester Polytechnic Institute, USA |

7 |

| Sassanelli, C |

0000-0003-3603-9735 |

Politecnico di Bari, Italy |

7 |

| Charter, M |

0000-0001-9743-4187 |

University for the Creative Arts, United Kingdom |

6 |

| Rosa, P |

0000-0003-3957-707X |

Politecnico di Milano, Italy |

6 |

| Boks, C |

0000-0002-3410-0582 |

Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway |

6 |

| Pieroni, M |

0000-0003-2968-7881 |

Aalborg University, |

6 |

| Andrews, D |

0000-0002-5761-3591 2012 2024 |

London Southbank University, United Kingdom |

6 |

| Saidani, M |

0000-0002-8269-4477 |

Luxembourg Institute of Science and Technology, Luxembourg |

6 |

| Authors with 5 References |

| Dey, P; Awan, U; Papamichael, I; Centobelli, P; Kim, H; Broega, A; Niero, M; Velenturf, A; Henninger, C; Terzi, S; Morone, P; Bressanelli, G; Urbinati, A; Chiaroni, D; Sumter, D; Muthu, S; Cheshire, D; Dabaieh, M; Sundin, E |

Table 6.

Top 20 reference sources.

Table 6.

Top 20 reference sources.

| Journal, Conference Proceedings, Books |

Reference Type |

Reference Count in Dataset |

| Sustainability |

Journal |

112 |

| Journal of Cleaner Production |

Journal |

72 |

| Resources, Conservation and Recycling |

Journal |

34 |

| Business Strategy and the Environment |

Journal |

34 |

| Circular Economy and Sustainability |

Journal |

25 |

| Journal of Industrial Ecology |

Journal |

16 |

| Sustainable Production and Consumption |

Journal |

16 |

| EcoDesign for Sustainable Products, Services and Social Systems II |

Edited Book |

15 |

| Environmental Footprints and Eco-design of Products and Processes |

Edited Book |

15 |

| International Journal of Production Research |

Journal |

12 |

| Management Decision |

Journal |

11 |

| Science of the Total Environment |

Journal |

11 |

| Waste Management & Research: The Journal for a Sustainable Circular Economy |

Journal |

11 |

| EcoDesign for Sustainable Products, Services and Social Systems I |

Edited Book |

11 |

| Journal of Environmental Management |

Journal |

10 |

| Procedia CIRP |

Journal |

10 |

| Polymers |

Journal |

9 |

| Production Planning & Control |

Journal |

9 |

| Energies |

Journal |

9 |

| Proceedings of IDEAS 2022 |

Proceedings |

9 |

A notable characteristic of this list is its similarity to that in the 2017 paper by Geissdoerfer et al., that researched the emergence of the CE as a paradigm and which had the Journal of Cleaner Production, Resources, Conservation and Recycling, and Sustainability as the top three journals [

7]. However, these are not journals closely associated with the creative industries (e.g., Journal of Cinema and Media Studies, Journal of Architecture, International Journal of Advertising, Journal of Marketing etc).

Only one set of conference proceedings made the top 20 list, but this may be i) that relevant conferences do not publish proceedings; ii) a metadata issue as there is inconsistency in how the online sources use report titles, reference types, keywords, etc.

3.2. Analysis of National CE Strategies

Table 7 shows the 73 national CE strategies reviewed (the United Kingdom's devolved nations were reviewed separately as there is no current integrated strategy). In addition, three regional frameworks were included: European Commission Circular Economy Action Plan, the ASEAN Framework, and the Africa Circular Economy Facility.

Across these documents, there is a consistent pattern: in terms of a sector of the economy, the creative industries are largely excluded from formal policy frameworks. When mentioned, references are typically focussed on waste-related activities such as textile recycling, or broad statements about eco-design, or in the context of campaigning for a change in citizen behaviour. This omission persists despite the sector’s significant economic footprint in several of the nations. This may be due i) to a lack of engagement by the creative industries sector with policymaking; or ii) a matter of priority – policymakers likely started with the largest waste streams in their economies; or iii) the creative industries are seen as low impact.

There are notable exceptions. Four national strategies (Luxembourg [

60], Montenegro [

61], Rwanda [

62], and Slovenia [

63]) explicitly identify the creative industries as a priority economic sector in respect of their national CE transitions. Luxembourg positions the sector as a driver of sustainable design and economic diversification, promoting collaboration through its Creative Industries Cluster. Rwanda includes the creative economy within its green growth strategy, linking it to innovation, youth employment, and low-carbon entrepreneurship (including digital circularity). Slovenia frames the sector as agents of behavioural and cultural change, emphasising the role of storytelling, design, and media in public engagement. Montenegro similarly advocates for a “circular culture,” highlighting the importance of the creative industries in shaping values and embedding circularity within education and everyday life. However, even in these national strategies, there is a lack of detail about how the entire sector should move forward.

While CE can help with the decarbonisation required to deliver national net zero ambitions, this is not usually directly addressed in national CE strategies. Also, the link between actions needed to decarbonise and net zero targets is generally not made clear, and this is also true in the creative industries where the connection between the growing use of technologies such as AI and the resulting impact on energy consumption and hence emissions may not be acknowledged.

Some of the strategies analysed explicitly acknowledge that there is a connection between the CE and national net zero ambitions, e.g., the Australian strategy [

64] contains the sentence “Circular economy strategies also support a sustainable, nature positive net zero transition, by ensuring technologies, materials, and infrastructure developed during the transition can be recovered and reused at their end of life”. However, acknowledging that national CE and net zero strategies are complementary is not universal, although mentions of clean or renewable energy is common.

3.2.1. Applying the MLP lens

The various national CE strategies are structured differently, making direct comparison challenging. Using the MLP as an analytical lens helps to reveal more about the structure and content of the strategies.

At the landscape level, broad sustainability imperatives drive the strategies, such as the elimination of single-use plastics and reductions in construction and textile waste. Overall, at a landscape level, the specific drivers that relate to the creative industries, such as changes in media consumption and consumer preferences, and the impact of new technologies such as generative AI, are absent.

To legitimise CE transitions, the national strategies typically align with the UN SDGs (usually goals 12 and 13), international climate policy frameworks, and global trade dynamics (e.g., access to critical raw materials, reducing dependencies on imported materials). In all cases, the CE strategies are framed primarily in material terms (e.g., virgin resource dependency, emissions, or visible waste streams), inevitably focusing on traditional high-impact industrial sectors such as automotive and steel, rather than the creative industries.

At a sector regime level, the national CE strategies focus overwhelmingly on entrenched production-consumption systems in construction, automotive, food, agriculture, electronics, and textiles and don’t include the creative industries. Consequently, there is no attention on, for example, national infrastructures needed for the creative industries, particularly related to those sub-sectors that are digital-first or experiential. Likewise, policy instruments cluster around a common set of emerging mechanisms: Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), eco-design regulations, digital product passports, and sustainable procurement, all typically designed for linear to circular transitions in manufacturing ecosystems and not the creative industries.

At a niche level, as noted in the academic literature and stated above, the creative industries are experimenting with small-scale niche innovations, such as circular fashion business models and platforms, modular theatre-set design, bio-based materials and low-carbon virtual production for film and TV. Based on the analysis of the 73 national strategies, these experiments currently appear to be operating in a policy vacuum. There is little evidence of state-supported incubation or systematic scaling of circular practices within creative MSME businesses, even though these actors dominate the sector structurally and are often early adopters of sustainability practices. This fragmentation of the sector and the intangible nature of many of its outputs (e.g., digital, experiential, or narrative content) contribute to its invisibility in policy.

Since the national CE strategies focus on sectors with hard infrastructures and tangible flows, the “World Behind the Screen” (the tangible impact of digital production and data centres, increasingly central to creative workflows) remains unaddressed perhaps due to lack of awareness and complexity. In some cases, dematerialisation trends, such as digital fashion and virtual production, are presented as inherently sustainable, despite evidence of their growing energy and e-waste footprints.

3.2.2. Implications for the Creative Industries of Policy Paradigms

The national CE strategies analysed use the vocabulary of sustainable development, but many anticipate implementation through market-based approaches such as:

Government-backed green finance and bonds to channel funds into initiatives that support a CE transition;

Mobilising private sources of capital to support CE transitions through venture capital and private equity;

Developing markets to connect suppliers and buyers of secondary materials and circular goods;

Resource-pricing e.g., incentivising secondary material use by increasing the cost of virgin resource extraction or use;

Investment in smarter waste sorting infrastructures;

Using government and business procurement clauses to stimulate demand for circular products;

Calls for private sector innovation and technological progress (guided by light regulation) in areas such as AI-enabled recycling, blockchain-based traceability, and circular design tools.

The national CE strategies assume that technological and regulatory innovation can decouple growth from environmental harm without fundamentally challenging existing consumption patterns (a view often repeated in the technology sector and Silicon Valley in particular). As yet, this is unproven.

This predominately market-driven approach to implementing CE transitions has implications for the creative industries:

National CE strategies that prioritise digital tools (e.g. blockchain, product passports) and infrastructure investments may marginalise low-tech circular practices common in areas like fashion, crafts, and the performing arts. Likewise, the contribution of creative businesses that offer community-based solutions, such as local repair and upcycling services, may be ignored;

The creative industries may be required by customers or regulators to demonstrate circularity using quantifiable indicators (e.g. carbon reduction, traceability of materials and products), even if their actual contribution lies in changing values, narratives, and behaviour;

Sub-sectors like advertising, creative technology, and gaming may benefit if they prioritise development or application of technologies that align with CE goals, such as immersive storytelling to promote behaviour change or tools to reduce digital waste.

More generally, creative work that promotes social justice, intergenerational equity, and cultural transformation in their circularity transition may be overlooked if national CE policy frameworks focus narrowly on technological fixes and economic efficiency.

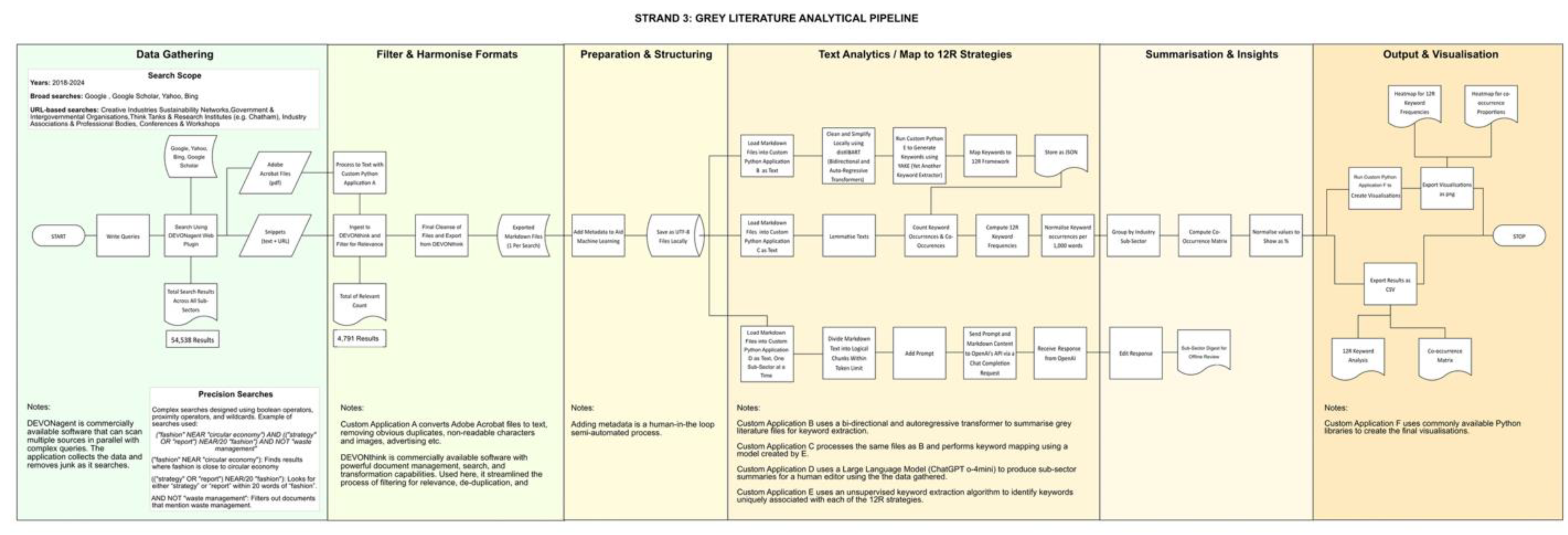

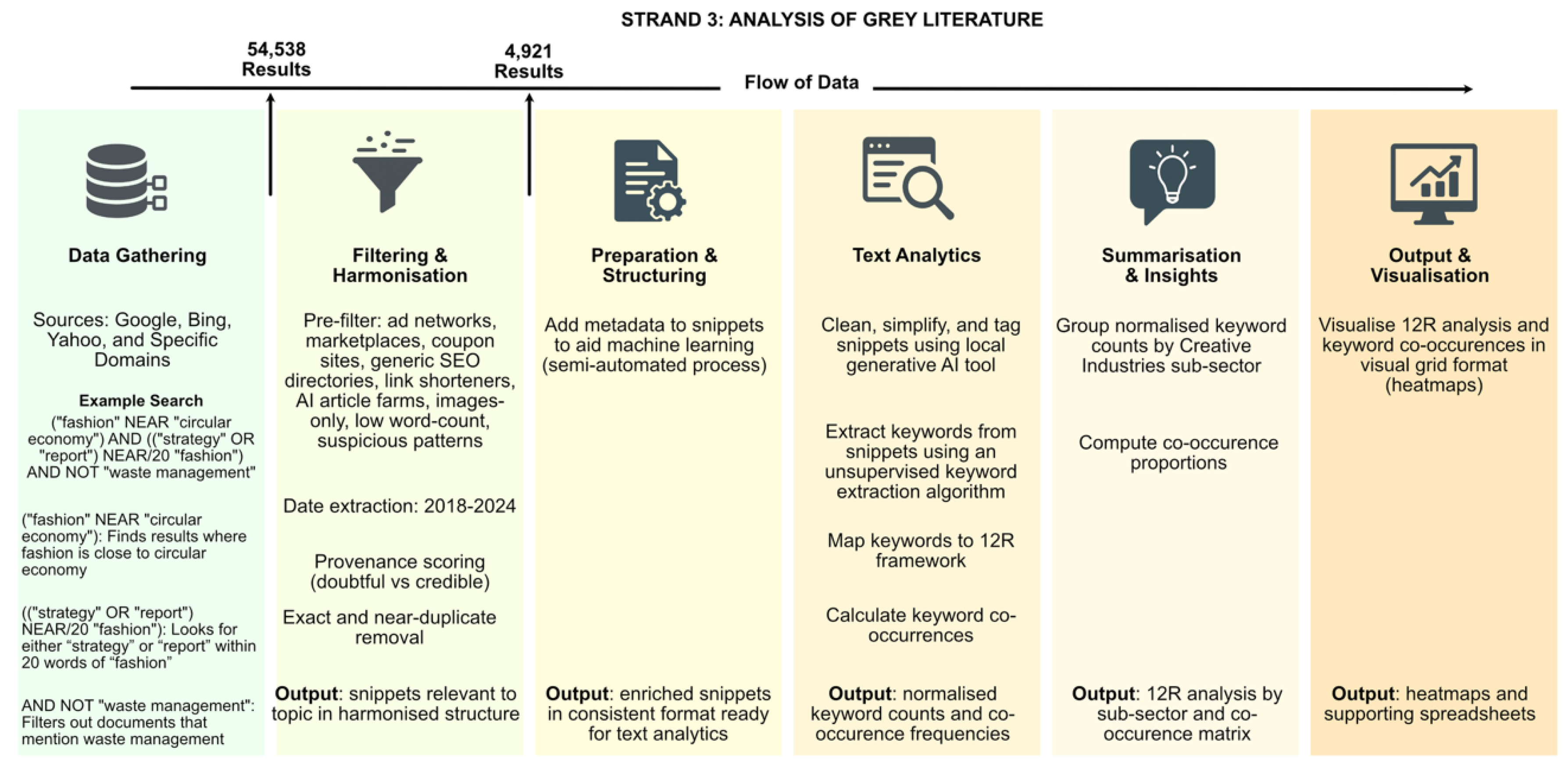

3.3. Grey Literature Analysis

Grey literature searches for the CE in the creative industries initially yielded 54,538 initial results, a high proportion of which were duplicates or short entries with links pointing to the same source. After deduplication, removal of short and off-topic entries, adverts, pay-walled articles, and academic journal entries, this gave 4,791 unique items (known as ‘snippets’) that had been screened for relevance to the CE across the sub-sectors of the creative industries. These snippets were used for text analytics.

Table 8 shows the breakdown of the search results by sub-sector.

Table 9 gives a breakdown by the dominant type of content found in each snippet.

Using keyword patterns phrases based on those widely used in industry handbooks, guides, and consultant reports when the goal is actionable insights or tools rather than abstract theorisation, the results were tagged as either ‘How-To/Practical’ or ‘Theory/Conceptual’. Excluding standards, and government policy, strategy, and regulatory content, 49% were How-To/Practical vs 51% Theory/Conceptual. In terms of concepts or frameworks, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF) is mentioned 565 unique times in the dataset (the most mentions), suggesting it is a dominant source and general reference point for CE thinking across the creative industries. However, most of the EMF content related to the sector is oriented towards fashion. In contrast, there are 207 unique mentions of the UN SDGs, suggesting a weaker relationship (but still strong).

The grey literature contains some of the most up to date and influential sources of information and practical guidance for the creative industries. For example, reports on investigations into materials [

65], virtual film production [

12] and [

21], industry handbooks such as the Theatre Green Book, sector guidance such as World Business Council for Sustainable Development Circular Transition Indicators for Fashion and Textiles, and standards such as BAFTA Albert. It is also highly fragmented and difficult to navigate quickly.

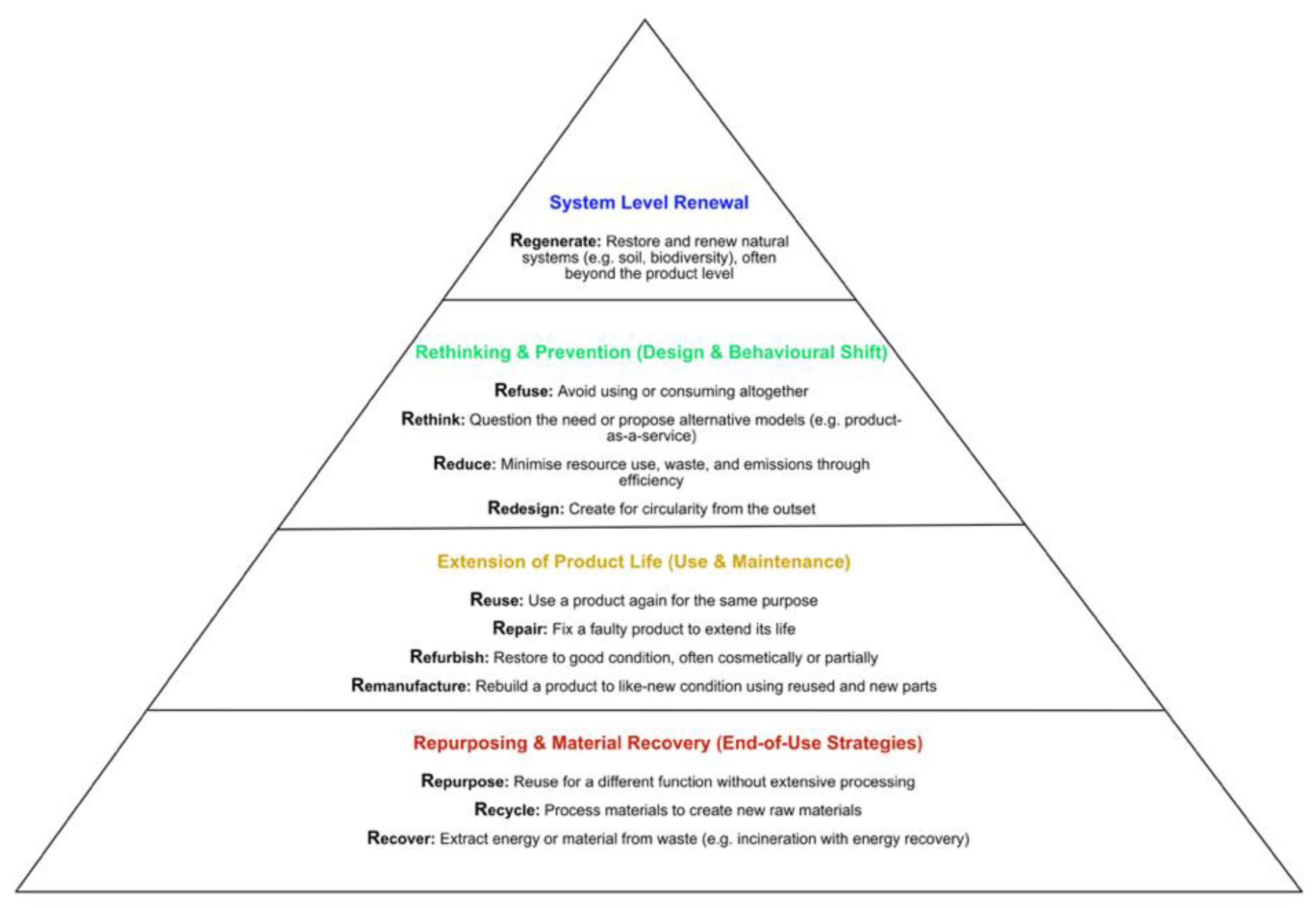

To further examine the practical application of the 12R strategies to the creative industries, additional text analytics were applied to the dataset to identify how the 12R strategies map out across the different sub-sectors. In n some cases sub-sectors have been further divided where this yielded meaningful findings e.g., separating out mass market fashion from designer fashion, radio and podcasts from TV and film, and theatre from the remainder of the performing arts). The results are presented in

Figure 5. A “rule of thumb” is that a value greater than five is a high frequency, and greater than 10 is very high.

This analysis shows that different sub-sectors (or segments within the sub-sector) are oriented towards different combinations of R strategies, and that three of the 12Rs are little mentioned (remanufacture, refurbish, and refuse). However, it is also possible that there are different understandings of the 12Rs between sub-sectors.

One anomaly is that the radio and podcasts segment has a high occurrence number in places due to the titles of the shows in the dataset being relevant (e.g., using words like “repair”). Hence, these results should not be taken as a commentary on the business of radio or podcasting.

Figure 6 presents the co-occurrences of the 12Rs in the dataset (a value of greater than 1.6% represents a significant co-occurrence at the 95% confidence level derived from a binomial one-sided test under the assumption of independence between terms). These pairings suggest natural groupings in how people write and think about CE topics. Redesign appears in three of the top five high-frequency co-occurrences. Redesign pairs particularly strongly with reduce, rethink, and recycle, reflecting its core role as bridge between R strategies (e.g., the more technical strategies such as recycle, and strategic ones such as rethink). Reduce is also prominent (appears in three high frequency pairs) implying that it is used in multi-dimensional contexts, i.e. not just about cutting resource use, but also reframing and reimagining designs, and systems.

3.3.1. Applying the MLP lens

Using keyword patterns associated with the levels of the MLP, the grey literature results were classified by the different levels as shown in

Table 10.

Ten percent of the grey literature search results were tagged as landscape content. This landscape content tends to be high level and less specific to the creative industries, even when the target audience is the sector. 57% of the content at this level comprises NGO, governmental, and intergovernmental CE publications that describe the CE concept and build the case for circularity transitions based on generic drivers such as climate change, public pressure for waste reduction. A typical example is the United Nations Economist Network Creative Economy publication “New Economics For Sustainable Development” [

66] that summarises CE concepts in the context of the creative industries and details the policy implications at global and country level. This landscape level content also contains descriptions of regional and global governance frameworks (e.g., the various UN initiatives, the European Green Deal, and various agreements on limiting emissions).

Only 21% of the content at the landscape level comes directly from organisations in the creative industries, specifically larger companies (e.g., the BBC, Universal Studios, Decathlon) and international networks and initiatives (e.g., Playing for the Planet). These organisations likely have dedicated resources capable of producing this type of content.

The sector regime content is almost 50% of the grey literature volume, with much of that content containing descriptions of how the regime in specific sub-sectors needs to change (or is changing), rather than a discussion of the sector as a whole. The content includes a wide range of topics such as national or local policies and regulation, industry circularity initiatives, the impact of digitalisation on the sector, changes to supply chains and infrastructure needed for low-carbon operation and circularity, and institutional barriers to transition.

The volume and diversity of sector regime content suggests that there is an extensive exploration of the pre-requisites and practical actions needed for regime-level change, at least within a subset of sub-sectors.

At a niche level (40% of the content), the grey literature contains diverse examples of CE experiments, pilots, startups, and emerging business models. Examples include 3D printing start-ups using biopolymers for on-demand products, corporate take-back and resale initiatives such as that at IKEA, and tools that take AI-generated art and place it into ready-to-use game engine environments for virtual production in advertising, film and TV. However, the challenge of scaling is again apparent in content from industry observers and the businesses themselves.

3.4. Online Survey of Practitioners

The survey was conducted during March and April 2025 and gathered 80 responses with informed consent from a diverse cross-section of professionals working within the sector and its supporting ecosystems. An initial analysis of the survey is contained in the report entitled “The Circular Economy in the Creative Industries: Progress, Challenges, and Hard Truths”[

10]. This paper builds on that initial analysis to present more granularity concerning current practices and future intentions for the sector through additional cross-tabulations for each sub-sector.

Of the 80 responses, 41 were from the target demographic, including partial responses, limiting some of the analyses and sub-sector representation (see

Table 11 for sub-sector breakdown, and

Appendix B,

Table B1,

Table B2, and

Table B3for the participant demographics).

The high proportion of responses from music, performing and visual arts (including theatre) introduces bias into the results. The higher number of survey responses may reflect a greater level of interest in the CE in that sub-sector, but it may also be due to the way that participants were recruited i.e., including some respondents via an active WhatsApp group with members in this area.

Also, where there are only one or two responses (advertising, marketing, crafts, publishing, and multiple sub-sectors), the results can only provide qualitative insights into perspectives within that part of the sector. Organisationally, the responses reflected the sector’s characteristic composition (90% were freelancers or MSMEs), and held a wide range of roles, including creatives, producers, technicians, and those in strategic or managerial positions related to sustainability.

Table 11.

Breakdown of survey responses by sub-sector showing the number fully completing the survey.

Table 11.

Breakdown of survey responses by sub-sector showing the number fully completing the survey.

| Sub-Sectors |

Fully Completed Responses |

| Music, Performing and Visual arts (incl. Theatre) |

13 |

| Film, TV, Video, Radio, and Photography |

7 |

| Design (incl. Graphic, Product, and Fashion |

6 |

| IT, Software and Computer Services (including Createch) |

5 |

| Architecture |

4 |

| Other (Multiple Sub-Sectors) |

2 |

| Publishing |

2 |

| Advertising and Marketing |

1 |

| Crafts |

1 |

| Total |

41 |

While the survey demographics offer insights into how circular practices are perceived and applied across different organisational contexts and scales, there are two important caveats. The sample sizes for cross-tabulation by sub-sector are small with missing data where some respondents skipped questions or abandoned the survey before completion), and despite being launched internationally, 80% of responses came from the United Kingdom. The remaining 20% included responses from Western Europe, the Nordics, the Middle East, and the USA. Despite the limited sample size, clear themes and shared concerns emerged, helping to identify priority areas for future research.

To understand the drivers for a transition to a more CE, the survey asked questions about priorities and sources of pressure. In terms of priority rankings,

Table 12 shows the breakdown by sub-sector based on a ranking 13 business areas, including the three CE ones shown in the table.

The rankings suggest that circular business models are currently low priority across the sector, but there are wide variations in the ranking for resource efficiency and decarbonisation. Perhaps the most surprising finding given the amount of coverage in the press concerning data centres (especially those for AI) is that the technology sub-sector respondents chose not to rank reducing emissions, energy, and waste as priorities.

To further understand prioritisation, respondents were asked about the importance of the CE to their sub-sector. For each sub-sector, the score was greater than four out of five (where five is very important), except for the technology sub-sector which had a mean score of 2.8 (see

Table 13).

Table 14 tabulates the level of pressure for adopting CE practices by sub-sector (where five is very high). Again, the technology sub-sector scores low compared to other sub-sectors, which may explain the low priority.

Table 15 shows the sub-sector variation in terms of sources of pressure to transition, today and in the future. While there is a spread of opinions about current sources, government regulations or policies are overwhelmingly viewed as the major source of pressure in the future.

A more regulated future may prove a challenge for some in the sector, as knowledge and readiness for regulation (e.g., extended producer responsibility, eco-design regulations etc), and standards such as BS8001 and ISO 59000 series is low in multiple sub-sectors (see

Table 16). Note that ‘awareness’ does not imply that companies are ready for regulation or using standards.

When asked how prepared organisations are to implement changes needed to meet a range of CE legislation, except for local, national, or regional waste management regulations (e.g., EU Waste Framework Directive), no sub-sector scored greater than 10%. There is clearly a knowledge and readiness gap and, more generally, only 36% said they were very knowledgeable or expert concerning the CE, and the majority came from the design (both product and fashion), film and TV, music and performing arts sub-sectors. Crafts and the technology sub-sectors’ respondents appeared to be the least knowledgeable (although only one craft respondent answered that question). 32% of respondents were unaware of any voluntary guidelines, frameworks, or toolkits for implementing CE practices, and fewer than 50% of respondents had received training or external guidance (despite there being a significant amount of self-guided learning available in the grey literature)

Another area of enquiry in the survey is organisational maturity using the Zero, Basic, Intermediate, and Advanced (ZBIA) scale developed by Professor Martin Charter.

Table 17 shows the breakdown by sub-sector.

The low percentage of architecture respondents self-identifying as Intermediate or Advanced compared to most of the other sub-sectors seems counter to the academic and grey literature findings (which suggest greater maturity). One interpretation is that this survey results may reflect greater self-awareness in the architecture profession of the status quo in that sub-sector.

The technology sub-sector also scores low on maturity, and this suggests that the technology sub-sector is not following the same maturity trajectory as the other sub-sectors of the creative industries. A possible interpretation is that the technology sub-sector prioritises innovation speed and market disruption over CE concerns. In addition, the technology sub-sector faces rapid software and hardware obsolescence cycles and globalised supply chains, which create specific structural barriers to adopting CE practices.

Table 17.

Breakdown by sub-sector of those respondents rating their organisational maturity level as intermediate or advanced.

Table 17.

Breakdown by sub-sector of those respondents rating their organisational maturity level as intermediate or advanced.

| Sub-Sector |

Sample Size |

Number Responding Zero or Basic |

Percentage Responding Zero or Basic |

Number Responding Intermediate or Advanced |

Percentage Responding Intermediate or Advanced |

| Advertising/Marketing |

0 |

No Data |

No Data |

No Data |

No Data |

| Architecture |

4 |

3 |

75% |

1 |

25% |

| Crafts |

1 |

0 |

0% |

1 |

100% |

| Design (Graphic, Product, Fashion) |

6 |

2 |

33% |

4 |

67%% |

| Film, TV, Video, Radio, and Photography |

6 |

2 |

33% |

4 |

67% |

| IT, Software and Computer Services (incl. Createch) |

5 |

4 |

80% |

1 |

20% |

| Music, Performing and Visual Arts (incl. Theatre and Dance) |

10 |

4 |

30% |

6 |

70% |

| Publishing |

0 |

No Data |

No Data |

No Data |

No Data |

| Other (Multi-Sector) |

2 |

0 |

0% |

2 |

50% |

| Total |

34 |

15 |

|

19 |

|

The analysis of the grey literature contains roughly equal volumes of conceptual and practical content. The survey shows that there is ambiguity over the understanding of the concept and definitions such as those contained in ISO59004, and this is discussed in the report [

10]. However, the survey also contains information about the practical application of the 12R strategies by sub-sector (see

Table 18).

The survey results are consistent with the analysis of the grey literature overall. Reduce, recycle and reuse have the highest representation across the sector. Remanufacture, refurbish, and regenerate strategies are less frequently reported (<25% in most sub-sectors), suggesting one or more of a lack of awareness, knowledge, expertise, applicability, or access to relevant infrastructure. Refuse and rethink also show low engagement, potentially showing challenges in upstream strategic design thinking or procurement-level decisions. For example, an advertising agency may find it economically unattractive to challenge a client brief or turn down work. Another way to look at this is that more technical or physical Rs (like recycle, reuse, reduce) dominate, while more abstract or upstream Rs (like rethink, refuse, redesign) are under-represented. From the comments in the survey, there is a perception that some Rs only apply to product-related sub-sectors (e.g., design, architecture), and some respondents replied certain Rs were not applicable to them.

Ignoring the lowest sample size sub-sectors, the strongest responses across the breadth of the 12Rs come from three sub-sectors: design; film, TV, video, radio, and photography, technology; and music, performing and visual arts. The relatively high percentages from the technology sub-sector across most of the 12Rs contrasts with earlier observations about priority and maturity. One interpretation is that respondents from this sub-sector are taking relevant actions but do not connect those actions to the overarching CE concept level.

Table 18.

Breakdown by sub-sector and R-strategy of ‘frequently applied’ or ‘common practice’ responses. Advertising and Publishing have not been included as there is no data.

Table 18.

Breakdown by sub-sector and R-strategy of ‘frequently applied’ or ‘common practice’ responses. Advertising and Publishing have not been included as there is no data.

| Sub-Sector |

|

Number or percentage responding ‘frequently applied’ or ‘common practice’ |

| Sample Size |

Refuse |

Rethink |

Reduce |

Reuse |

Repair |

Refurbish |

Remanufacture |

Repurpose |

Recycle |

Recover |

Regenerate |

Redesign |

| Architecture |

4 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

| Architecture (%) |

|

25 |

25 |

50 |

50 |

25 |

25 |

25 |

25 |

50 |

25 |

0 |

25 |

| Crafts |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

| Crafts (%) |

|

0 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

100 |

100 |

0 |

100 |

100 |

0 |

100 |

| Design (Graphic, Product, Fashion) |

5 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

| Design (Graphic, Product, Fashion) (%) |

|

60 |

20 |

60 |

40 |

40 |

0 |

40 |

40 |

40 |

40 |

20 |

60 |

| Film, TV, Video, Radio, and Photography |

4 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

| Film, TV, Video, Radio, and Photography (%) |

|

25 |

25 |

25 |

75 |

25 |

50 |

25 |

25 |

100 |

50 |

25 |

0 |

| IT, Software and Computer Services (incl. Createch) |

4 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

| IT, Software and Computer Services (incl. Createch) (%) |

|

50 |

75 |

50 |

50 |

25 |

25 |

25 |

50 |

50 |

25 |

0 |

75 |

| Music, Performing and Visual Arts (incl. Theatre and Dance) |

8 |

5 |

5 |

3 |

7 |

6 |

3 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

| Music, Performing and Visual Arts (incl. Theatre and Dance) (%) |

|

63 |

63 |

38 |

88 |

75 |

38 |

38 |

63 |

88 |

25 |

0 |

25 |

| Other (Multi-Sector) |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Other (Multi-Sector) (%) |

|

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

3.4.1. Applying the MLP Lens

At a landscape level, the respondents to the survey show an awareness of future international and regional policy and regulatory pressures, with a sense that broader systemic change is coming. However, there is little evidence that these pressures are currently shaping behaviour or incentives within the sector as a whole. Likewise, emerging horizontal standards (e.g. ISO 59004) are too recent to exert pressure and may be too generic.

Overall, the survey portrays organisations in the sector regime as fragmented in their approach to CE. There is uneven engagement with CE principles within and across sub-sectors, and for all sizes of organisation. Practical strategies are being applied, but focus mostly on concrete, familiar actions such as recycling, reuse, and reduction. It is implied that there is little regulatory pressure on the sector and few institutional structures that support CE transitions generally and specifically within the creative industries. Even the influence of guidance, standards, and tools originating from within the creative industries appears limited currently.

The open-ended responses in the survey provide an insight into niche-level activity. Responses highlight both the potential of niche CE innovations and the barriers to their adoption. Respondents shared examples of the reuse and repurposing of sets, props, and materials in film and television, and slow fashion models such as made-to-order production. Education and training for emerging creatives were seen as vital for embedding change from the ground up, while pan-industry collaboration, take-back schemes, and repair and refurbishment offer promising pathways for scaling circularity.

In contrast, respondents pointed to structural constraints such as time pressures in film, TV, and theatre production, the dominance of freelance and SME workers with limited resources, and the lack of infrastructure for reuse and recycling. Cost and quality concerns, alongside client and customer resistance, also make it difficult for niche innovations to scale.

3.5. Integrating the Four Research Strands with the MLP

The Multi-Level Perspective (MLP) provides a structured framework that helps to interpret the evidence presented across the literature review, national strategy analysis, grey literature dataset, and practitioner survey.

Figure 7 provides an umbrella perspective on the findings using the MLP framework.

At the landscape level, the forces acting on the creative industries appear broadly consistent with those shaping other sectors. International agreements (e.g., the Paris Agreement, the UN SDGs, the European Circular Economy Action Plan) and wider debates on decarbonisation and resource scarcity provide the same external orientation as for manufacturing or agriculture. The academic literature emphasises that these forces are generally interpreted through a material lens, with relatively limited attention given to the digital infrastructures and data-intensive practices now central to the creative industries. Thus, while landscape drivers are not unique to the sector, their translation into relevant pressures for digital, cultural, and experiential production remains underdeveloped.

Evidence regarding the sector regime suggests inertia compared to other industries, but with some sub-sectors more advanced than others. The academic literature identifies stronger engagement with CE concepts in architecture, design, and fashion, where existing standards, metrics, and material innovation are already embedded in professional practice. However, digital-first sub-sectors such as advertising, games, and createch are weakly represented in the academic literature and national strategies, suggesting that regime-level rules, norms, and infrastructures in multiple sub-sectors remain largely unaltered. The grey literature reinforces this picture: of the curated snippets, the majority concern regime-level adjustments such as voluntary standards and sub-sector specific guidance (e.g., the Theatre Green Book, BAFTA albert). These sources may carry disproportionate influence because they often constitute the most practical and accessible reference points for practitioners in sub-sectors, but they lack the formal authority of legislation or international standards.

At the niche level, the academic literature and grey evidence highlight significant experimentation. Examples include regenerative and bio-based materials in fashion, virtual production in film and television, modular set design in theatre, and blockchain-enabled traceability. The grey literature captures these developments in greater volume and detail than peer-reviewed publications, suggesting that practice-led sources are currently the main record of innovation. However, both the academic literature and grey evidence agree that scaling remains limited, and policy support for incubation or acceleration is absent from most national strategies. With few exceptions, niche CE practices appear not to have challenged the way the sector operates so far in any substantive manner.

The survey evidence provides an additional perspective on the sector regime and niche levels by situating the findings in organisational contexts. Responses show that resource efficiency and waste reduction are common practices across sub-sectors, but that awareness of CE standards and preparedness for regulatory compliance remain low. The survey confirms the picture of uneven maturity: some sub-sectors apply a range of R-strategies without recognising them as part of a broader CE framework, while others identify the importance of circularity in principle but lack the capacity to act systematically. Although the small and UK-weighted sample limits generalisability, the survey illuminates how sector fragmentation and the predominance of freelancers and MSMEs shape regime stability and limit scaling of niche innovations.