1. Introduction

As human space missions extend in duration and complexity, maintaining astronaut health under microgravity conditions has become an essential research priority. The gut microbiota is a key component of human health, influencing nutrient absorption, immune regulation, and host metabolism. Previous studies have demonstrated that spaceflight induces marked alterations in gut microbial composition and diversity, including reduced diversity and altered metabolic activity [

1,

2]. These changes are associated with gastrointestinal dysfunction, impaired immunity, and increased inflammation, which pose risks for astronaut well-being during missions.

Notably, research on the International Space Station (ISS) has revealed significant restructuring of gut microbial communities under spaceflight conditions, affecting both beneficial and potentially pathogenic taxa [

3]. Probiotic genera such as

Bifidobacterium and

Lactobacillus have been highlighted for their role in maintaining gastrointestinal stability and mitigating spaceflight-related symptoms such as constipation [

4].

This review systematically examines the impact of microgravity on gut microbiota composition and function, emphasizing microbial diversity, metabolic alterations, and adaptive responses. We also discuss the translational potential of these findings, focusing on probiotic or dietary countermeasures for astronaut health, as well as implications for terrestrial gastrointestinal disorders [

5,

6].

2. Current Advances in Gut Microbiota Research Under Microgravity

Recent research has provided valuable insights into how microgravity alters the composition and function of the gut microbiota. One of the most prominent changes is the alteration in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio, a critical marker of gut health. Studies have shown that microgravity tends to increase the F/B ratio, which has been linked to obesity and metabolic dysfunction [

1,

2]. In parallel, elevated lipopolysaccharide (LPS) levels, associated with intestinal permeability and systemic inflammation, have been observed [

3]. Furthermore, beneficial taxa such as

Akkermansia muciniphila, essential for maintaining mucosal barrier integrity, are significantly reduced in microgravity [

4].

Simulated microgravity models, including rotating wall vessel bioreactors and space-based experiments, demonstrated that

Lactobacillus and

Bifidobacterium experience changes in growth kinetics, stress tolerance, and metabolic activity [

5]. These studies also revealed decreased production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as acetate and butyrate, which play critical roles in maintaining gut epithelial integrity and immune modulation [

6].

Notably, Pseudomonas aeruginosa exhibited transcriptional and proteomic reprogramming under spaceflight conditions, with increased expression of genes associated with quorum sensing, biofilm formation, and virulence [

7]. Such findings highlight the dual effects of microgravity: reducing beneficial microbial diversity while promoting the dominance of stress-tolerant or pathogenic species.

Table 1 summarizes key studies investigating the effects of microgravity on gut microbiota, including alterations in diversity, community structure, and metabolic activity, as well as their implications for astronaut health.

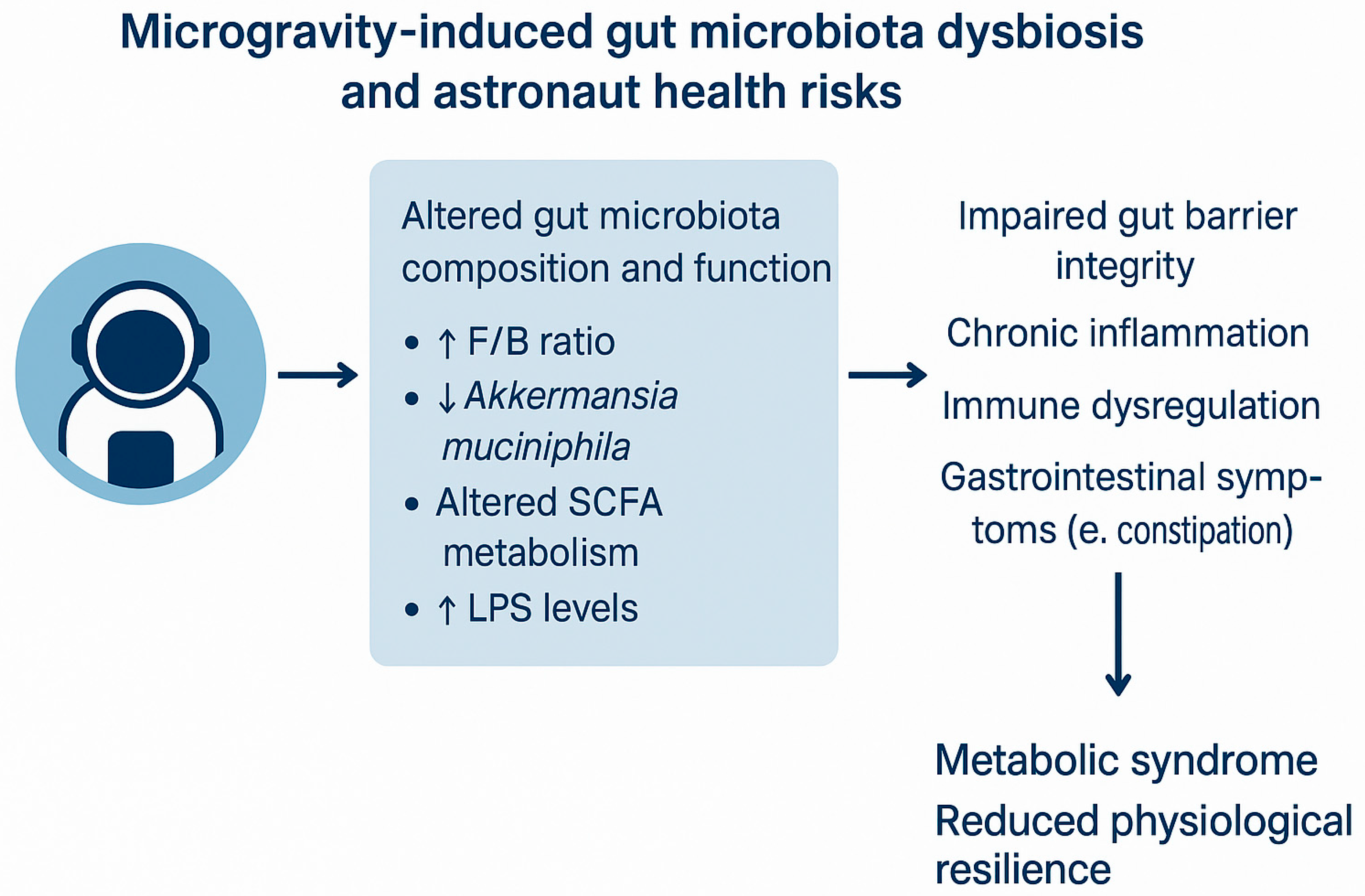

The conceptual overview of how microgravity influences gut microbiota composition and function is shown in

Figure 1, highlighting changes in microbial diversity, community structure, and metabolic activity, as well as potential health consequences such as inflammation and gastrointestinal dysfunction.

Spaceflight studies and ground-based simulations have demonstrated consistent patterns. For instance, Estevez et al. (2020) [

1] reported reduced microbial diversity and a shift toward stress-tolerant species under microgravity, while Crabbé et al. (2011) [

2] showed metabolic reprogramming of

Pseudomonas aeruginosa with increased virulence potential. Additionally, research by Voorhies et al. (2019) [

5] and Turroni et al. (2020) [

6] further revealed declines in commensal species such as

Bacteroides, which are essential for gut homeostasis. These findings illustrate the profound effects of microgravity on both the taxonomic and functional landscape of the gut microbiota.

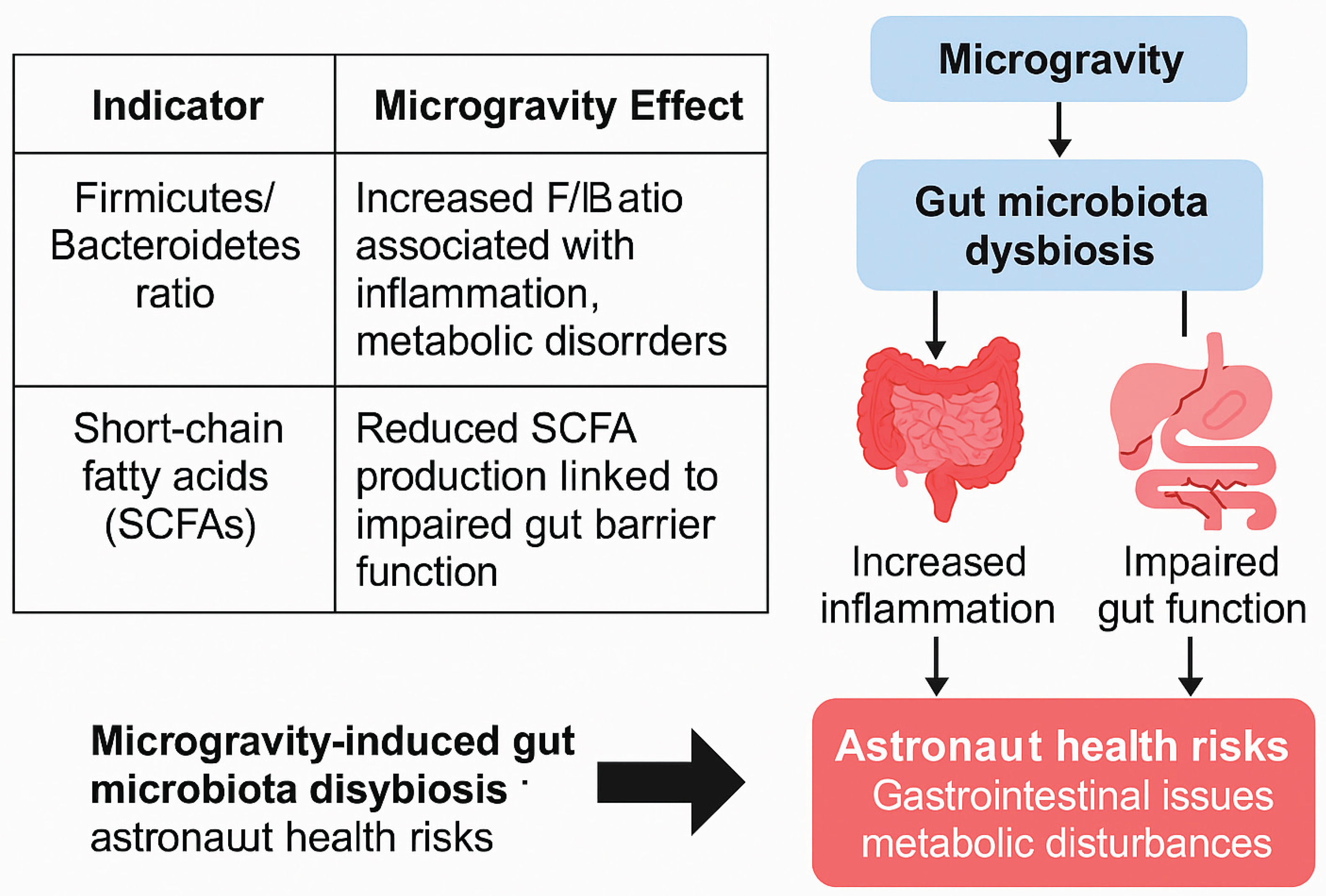

An integrated summary of F/B ratio shifts, SCFA metabolism changes, and downstream health implications is presented in

Figure 2. The left panel provides tabulated data summarizing microbiota and metabolic changes, while the right schematic illustrates health impacts on astronauts, including immune suppression, increased inflammation, and gastrointestinal dysfunction.

3. Significance of Research Advances

Understanding how microgravity reshapes gut microbial diversity and metabolism is crucial for safeguarding astronaut health during long-duration missions. Dysbiosis under microgravity can result in gastrointestinal problems, impaired immunity, and heightened systemic inflammation [

8]. The documented reduction of beneficial species and SCFA production underscores the importance of nutritional and microbial interventions in spaceflight.

Probiotic-based strategies have been increasingly investigated as countermeasures. Specific strains such as

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and

Bifidobacterium longum have shown promise in stabilizing gut homeostasis, reducing inflammation, and improving barrier function under stress conditions [

9,

10]. Synbiotic approaches, combining probiotics with prebiotic fibers, further enhance colonization and metabolic activity of beneficial microbes [

11]. These targeted interventions provide a practical and feasible strategy for preventing constipation, immune suppression, and metabolic disorders in astronauts.

Beyond space applications, these findings also have translational significance for terrestrial health. Insights into microgravity-induced dysbiosis may inform strategies for managing conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, metabolic syndrome, and inflammatory bowel disease [

12].

4. Challenges

Despite significant progress, several challenges remain in translating microbiome research into operational countermeasures for space health. First, inter-individual variability in microbiome composition complicates the development of standardized probiotic or dietary interventions [

13]. Second, most current studies rely on simulated microgravity systems, which only partially replicate real spaceflight conditions [

14]. Third, limitations in onboard experimental facilities constrain the depth of in situ microbiome analysis during missions [

15].

To address these issues, efforts are underway to integrate real-time omics technologies and miniaturized sequencing platforms aboard space missions [

16]. Additionally, personalized approaches based on pre-flight microbiome profiling may allow customized countermeasures tailored to individual astronauts [

17]. Ongoing international projects such as NASA’s GeneLab and ESA’s MELiSSA provide collaborative platforms to overcome technical and methodological barriers [

18].

5. Future Research Directions

Future studies should focus on multi-omics integration, including metagenomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, and proteomics, to provide a holistic understanding of microbial adaptation in space. These approaches can uncover biomarkers of dysbiosis and targets for intervention [

19].

Technological innovations such as lab-on-a-chip systems and portable sequencing devices (e.g., MinION) could enable real-time monitoring of microbial shifts during missions [

20]. In addition, ground-based analogs such as long-term bed rest studies and Antarctic isolation experiments provide complementary models for testing interventions under extreme conditions [

21].

International collaboration will remain key to advancing this field. Programs like NASA’s GeneLab and ESA’s MELiSSA not only enhance data sharing but also facilitate the validation of probiotic-based countermeasures across different mission profiles [

18]. Expanding these networks to involve Asian research consortia could further accelerate discovery and application.

6. Conclusions

Microgravity induces profound changes in gut microbiota diversity, community structure, and metabolic activity, with implications for astronaut gastrointestinal and immune health. Advances in probiotic and dietary countermeasures highlight promising strategies to mitigate dysbiosis and related risks during long-duration spaceflight. Importantly, the translational potential of these findings extends to terrestrial medicine, offering insights into managing metabolic and inflammatory diseases.

This review emphasizes the urgent need for integrated omics, space-compatible culture systems, and international collaboration to ensure astronaut health. By bridging microbiome science and space medicine, this field holds substantial promise for both

future space missions and ground-based disease interventions [

22].

Author Contributions

Yixian Sun (First Author): Conducted the comprehensive literature search, organized the collected references, and drafted the initial version of the manuscript. High school student; major contributor in literature review and manuscript drafting. ORCID ID: Not available (student author). Qiwei Gao (Co-Author): Assisted in literature review and contributed to the synthesis of recent findings, particularly in the sections on microbiome diversity and metabolic function. High school student; assisted with literature synthesis. Chenling Su (Co-Author): Contributed to refining the discussion, assisted in editing and formatting the manuscript, and verified reference accuracy. High school student; contributed to editing and reference verification. Xia Wang (Corresponding Author): Supervised the entire project, guided the conceptual framework and manuscript structure, critically revised the text for scientific accuracy, and is responsible for correspondence with the journal. Biology teacher and project supervisor. ORCID ID: Not available.

Funding

This work received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the high school biology research program and teaching staff for their guidance and support during this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Estevez, J.; Smith, C.; Li, P. Microgravity Fluid Processing and Bacterial Response in Space. Microb. Ecol. Space 2020, 78, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabbé, A.; Schurr, M.J.; Monsieurs, P.; Morici, L.; Schurr, J.; Wilson, J.W.; Ott, C.M.; Tsaprailis, G.; Pierson, D.L.; Stefanyshyn-Piper, H.; Nickerson, C.A. Transcriptional and Proteomic Responses of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 to Spaceflight Conditions Involve Hfq Regulation and Reveal a Role for Oxygen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrett-Bakelman, F.E.; Darshi, M.; Green, S.J.; Gur, R.C.; Lin, L.; Macias, B.R.; McKenna, M.J.; Meydan, C.; Mishra, T.; Nasrini, J.; et al. The NASA Twins Study: A Multidimensional Analysis of a Year-long Human Spaceflight. Science 2019, 364, eaau8650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrien, M.; Vaughan, E.E.; Plugge, C.M.; de Vos, W.M. Akkermansia muciniphila Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov., a Human Intestinal Mucin-degrading Bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 1469–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voorhies, A.A.; Lorenzi, H.A. Astro-omics: Omics in Space Exploration. OMICS 2016, 20, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turroni, F.; Milani, C.; Duranti, S.; Lugli, G.A.; van Sinderen, D.; Ventura, M. Bifidobacteria and the Infant Gut: An Example of Co-evolution and Natural Selection. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, C.A.; Ott, C.M.; Mister, S.J.; Morrow, B.J.; Burns-Keliher, L.; Pierson, D.L. Microgravity as a Novel Environmental Signal Affecting Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Virulence. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 3147–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, Y.; Morita, T.; Kimura, S.; Yoshida, H.; Ikeda, T.; Mita, H.; Yamamoto, Y.; Sato, K.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, H. Oxidative Stress and Microbiota Changes under Simulated Microgravity. Life 2022, 12, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Patel, A.; Taneja, N. Short-chain Fatty Acid Metabolism under Altered Gravity Conditions: Implications for Astronaut Gut Health. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1100747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouwehand, A.C.; Salminen, S.; Isolauri, E. Probiotics: An Overview of Beneficial Effects. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2002, 82, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowiak, P.; Śliżewska, K. Effects of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics on Human Health. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, R.; Mainali, R.; Ahmadi, S.; Wang, S.; Singh, R.; Kavanagh, K.; Kitzman, D.W.; Kushugulova, A.; Marotta, F.; Yadav, H. Gut Microbiome and Aging: Physiological and Mechanistic Insights. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, J.A.; Blaser, M.J.; Caporaso, J.G.; Jansson, J.K.; Lynch, S.V.; Knight, R. Current Understanding of the Human Microbiome. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herranz, R.; Anken, R.; Boonstra, J.; Braun, M.; Christianen, P.C.M.; de Geest, M.; Hauslage, J.; Hilbig, R.; Hill, R.J.A.; Lebert, M.; et al. Ground-based Facilities for Simulation of Microgravity: Organism-specific Recommendations for Their Use, and Recommended Terminology. Astrobiology 2013, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, P.W. Impact of Space Flight on Bacterial Virulence and Antibiotic Susceptibility. Infect. Drug Resist. 2015, 8, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Wallace, S.L.; Chiu, C.Y.; John, K.K.; Stahl, S.E.; Rubins, K.H.; McIntyre, A.B.R.; Doddapaneni, H.; Miner, B.E.; Koboldt, D.C.; Sabharwal, A. Nanopore DNA Sequencing and Genome Assembly on the International Space Station. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 18022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vujkovic-Cvijin, I.; Sklar, J.; Jiang, L.; Natarajan, L.; Knight, R.; Belkaid, Y. Host Variables Confound Gut Microbiota Studies of Human Disease. Nature 2020, 587, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horneck, G.; Klaus, D.M.; Mancinelli, R.L. Space Microbiology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2010, 74, 121–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhernakova, A.; Kurilshikov, A.; Bonder, M.J.; Tigchelaar, E.F.; Schirmer, M.; Vatanen, T.; Mujagic, Z.; Vila, A.V.; Falony, G.; Vieira-Silva, S.; et al. Population-based Metagenomics Analysis Reveals Markers for Gut Microbiome Composition and Diversity. Science 2016, 352, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.; Olsen, H.E.; Paten, B.; Akeson, M. The Oxford Nanopore MinION: Delivery of Nanopore Sequencing to the Genomics Community. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Ulrich, C.M.; Neuhouser, M.L. Spaceflight and the Gut Microbiome: Implications for Astronaut Health. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2021, 24, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horneck, G.; Rettberg, P.; Walter, N.; Gomez, F.; Leuko, S.; Rabbow, E.; Willnecker, R.; Reitz, G. Astrobiology Research in Low Earth Orbit: Results and Future Perspectives. Adv. Space Res. 2016, 58, 1275–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).