1. Introduction

Currently, there is an acute shortage of clean water, more than 40% of the world's population does not have access to clean water. Even more important is the problem of water scarcity in technological processes, as well as in agriculture [

1,

2,

3]. The most effective method of solving this problem is electromembrane methods of water purification [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. One of the promising directions is the use of electrodialysis machines, which are alternating concentration and desalination chambers separated by anion exchange and cation exchange membranes [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

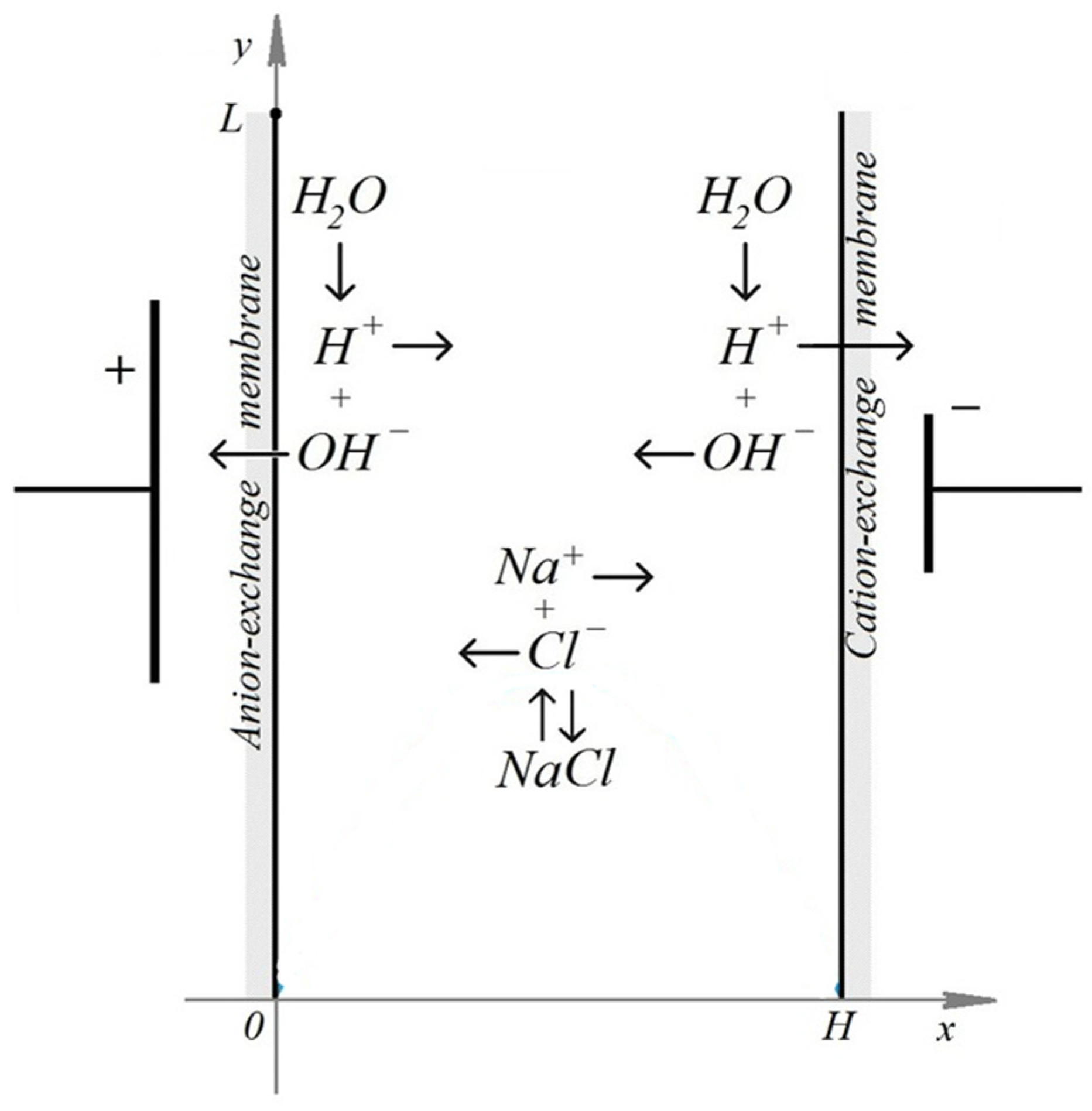

Let's consider the steady-state transport of binary salt ions, such as

. The mathematical models in the diffusion layer and the one-dimensional cross-section of a desalination channel formed by an anion-exchange and cation-exchange membrane differ significantly, and the diffusion layer model cannot be considered a submodel of the channel cross-section, even though physically there are two diffusion layers in the channel cross-section, namely, near the anion-exchange and cation-exchange membranes. Indeed, let's consider the diffusion layer near one of the membranes, for example, a cation-exchange membrane. The equations describing the mathematical models of ion transport in the diffusion layer and the channel cross-section are identical, as are the boundary conditions at the imaginary solution/cation-exchange membrane boundary at

. The boundary conditions of these models differ at

, since the physical processes at this point differ. In the channel cross-section, the anion-exchange membrane is located at point

, while for the diffusion layer, point

represents the depth of the solution where the concentrations are known and the electroneutrality condition is satisfied. Diffusion layer models assume that the solution is perfectly mixed at point

, so the concentration of cations and anions is the same and corresponds to the initial solution concentration. Thus, transport in the diffusion layer retains some features of the two-dimensional model. When considering a channel cross-section, the fundamental assumption is that the solution is immobile. This leads to fundamental differences in the mathematical models of ion transport in the channel cross-section and in the diffusion layer. For example, under the natural assumption of ideal selectivity of ion-exchange membranes, the anion flux through the cation-exchange membrane is zero, and all current is carried by cations. The magnitude of this current can be arbitrary, depending on the potential drop at points

and

(

Figure 1 ) In channel cross-section models, in addition to the anion current being zero, the cation current is also zero, since the anion-exchange membrane is also perfectly selective. Thus, the salt ion current in channel cross-section models is zero. Each model has its own advantages and disadvantages. For example, channel cross-section models allow one to consider the recombination/dissociation process in the extreme steady-state case, when the influence of salt ions is minimal, since the salt ion current is zero. Furthermore, the mathematical model of binary electrolyte transport in a channel cross-section provides a more detailed description of ion flows and interactions, allowing for complex geometric and physical conditions to be taken into account. This leads to increased prediction accuracy and process optimization compared to the diffusion layer model.

Water dissociation at interfaces and changes in the equilibrium coefficient are important for understanding the processes occurring during substance transfer through selective ion-exchange membranes. Changes in the rate coefficient of water molecule dissociation at interfaces (membrane/solution or membrane/membrane) can have several causes, as indicated in [

18]. This paper examines the effect of an electric field on the equilibrium coefficient of the dissociation/recombination reaction of water molecules using a new mathematical model of steady-state salt ion transport in a channel cross-section, taking into account the dissociation/recombination reaction of water molecules.

In the works of Onsager [

18], Timashev S.F., and Sheldeshov N.V. [

19,

20], the change in the equilibrium coefficient is associated with the magnitude of the electric field strength. In some studies [

22,

23], in contrast to the above-mentioned studies, the change in the equilibrium coefficient is associated not simply with the magnitude of the electric field strength, but with the magnitude of the space charge.

A change in the equilibrium coefficient, according to the proposed mathematical model, leads to a significant increase in the fluxes of

and

ions. This leads to a local increase in the equilibrium coefficient, for example, in the quasi-equilibrium boundary layer region by a factor of 10–30, which corresponds in order of magnitude to experimental data [

21].

2. A Mathematical Model of the Influence of the Dependence of the Dissociation Coefficient on the Magnitude of the Space Charge on the Stationary Transport of Salt Ions in the Channel Cross-Section

According to the concepts developed by Onsager, Timashev S.F., Sheldeshov N.V. et al. [

18,

19,

20] for bipolar membranes, the current density of

(

) ions generated in the membrane system is determined by an empirical formula, where the equilibrium coefficient exponentially depends on the strength of the external electric field.

In electrodialysis systems with monopolar membranes, few studies have been devoted to the study of this dependence [

22,

23].

There are considerations from which it follows that, in contrast to the above-mentioned works, in systems with monopolar membranes, the change in the equilibrium coefficient can be associated not simply with the magnitude of the electric field strength, but with the magnitude of the space charge, that is,

, where

, the value of the space charge at point

,

is an adjustable parameter,

dissociation coefficient,

recombination coefficient,

as the concentrations, of the

i-th ion,

- water concentration,

is Faraday’s constant. The dependence of ion flows on the magnitude of space charge was first mentioned in the work of V.V. Nikonenko et al. [

21]. To explain the influence of the magnitude of space charge on the equilibrium coefficient, let us consider the process of increasing dissociation of water molecules near the anion-exchange membrane. In this region, the space charge is determined by the predominance of the concentration of

ions over the concentrations of all other ions. As is known, a water molecule is a dipole, at one end of which are located

and

.

ions surround the water molecule from the

side, weakening (shielding) and breaking its bond with

. As a result, the resulting free

ions are transferred unhindered through the anion-exchange membrane and do not participate in further processes, while

ions move into the solution, and the higher the concentration of

ions, the greater the flow of

ions. Thus, the greater the magnitude of the space charge, the more intense this process, which is in fact the electrolytic dissociation of water molecules, occurs; that is, the equilibrium coefficient kw depends on the magnitude of the space charge. This corresponds to the point of view of Onsager L., that the increase in the equilibrium coefficient is due to the gradual screening of the ion's electric field by the surrounding space charge [

2]. In the region of the space charge in the vicinity of the cation exchange membrane (CEM), similar processes occur, only the role of

ions is played by

or

ions,

ions are injected into the solution, and

ions are transferred through the CEM and do not participate in further transfer processes.

2.1. System of Equations

Under the above conditions, the steady-state transfer of salt ions for a 1:1 electrolyte into the channel cross-section, taking into account the space charge and the dissociation/recombination reaction, taking into account the dependence of the dissociation coefficient on the magnitude of the space charge, is described by the extended system of Nernst-Planck-Poisson equations [

23].

Let us denote

as the potential,

,

,

as the flux, concentrations, and diffusion coefficients of the

i-th ion, respectively. In the steady-state case

[

23]. Therefore, the current carried by the salt ions is equal to zero, and, consequently, the total current (formula) is equal to the current carried by the

and

ions:

. Thus, the steady-state transport in the one-dimensional cross-section of the desalination channel can only be equilibrium with respect to the salt ions.

Thus, the system of equations has the form:

Here, (1) represents the material balance equations; (2) are the Nernst–Planck equations for the fluxes of potassium or sodium ions (), chloride ions (), hydrogen ions (), and hydroxide ions (); (3) is the Poisson equation for the electric potential; (4) are the formulas describing the dissociation/recombination reaction of water molecules; (5) is the current flow equation, which states that the current density through the cross-section of the desalination channel is determined by the ionic fluxes, i.e., it corresponds to the Faraday current density.

Here, is the dielectric permittivity of the solution, is the universal gas constant, is the potential, charge numbers, T - absolute temperature of the solution, - reaction speed, is the electric field strength, is the recombination rate constant, is the dissociation rate constant of water molecules, and, consequently, is the equilibrium coefficient (ionic product of water).

2.2. Boundary Conditions

The concentrations of anions (5) and cations (10) at the membrane surfaces are determined by their exchange capacity, with the membranes assumed to be ideally selective (6), (11). It is assumed that in the surface layer of the membranes the generation of and ions occurs, and these ions freely pass through the cation-exchange and anion-exchange membranes (8), (12), no longer participating in the subsequent transport processes. At the same time, from the surface of the anion-exchange membrane a flux of ions is injected into the solution, determined by condition (7), while from the surface of the cation-exchange membrane a flux of ions is injected (13). The membrane surfaces are considered equipotential, and the potential jump is defined by relations (9) (14).

3. Analysis of the Numerical Solution

The numerical solution was obtained using the finite element method. To analyze the results, calculations were performed with a wide range of initial data, the fitting parameter , and so on. The most representative results are presented below: in each figure, the results for are shown on the left, while those for are generally shown on the right.

To analyze the results of the numerical solution, we will use the following functions:

1. the charge distribution density normalized by Faraday’s constant ,

2. the equilibrium function , or , where ,

3. the equilibrium coefficient .

3.1. Concentration Distribution

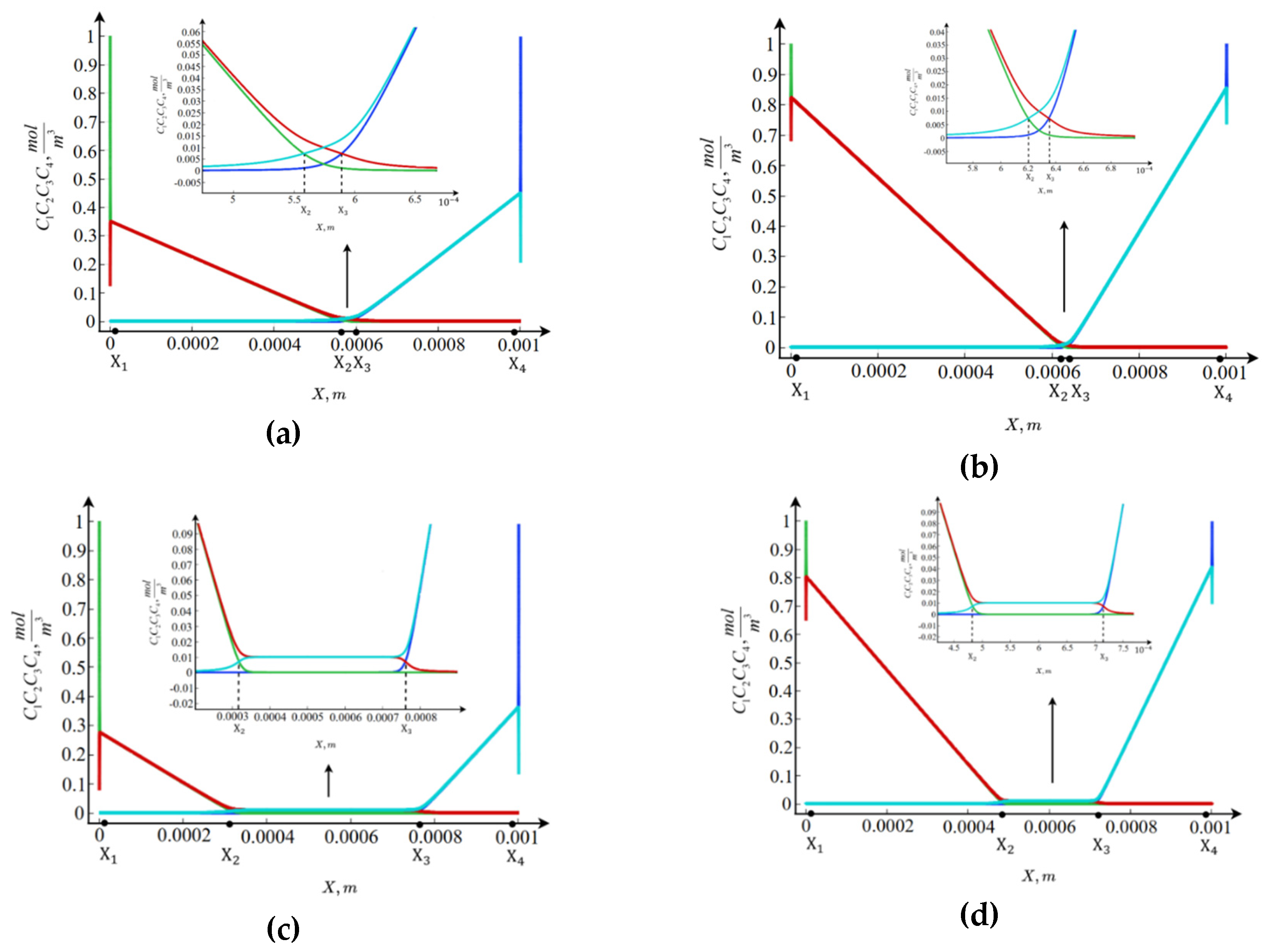

As shown in

Figure 2 (a, b), the qualitative behavior of the concentrations of all four ion species for

and

is similar. Specifically, near the ion-exchange membranes, boundary layers are observed where the concentrations of chloride ions

and hydrogen ions

at the anion-exchange membrane (

), as well as sodium ions

and hydroxide ions

at the cation-exchange membrane (

), vary at an exponential rate. Beyond these layers, there are relatively large regions adjacent to the boundaries where the concentrations of the above-mentioned ions change linearly or are nearly zero. Moreover, the concentrations of

and

match with high accuracy, as do those of

and

. In the central part of the channel, there exists a region with nearly constant concentration distributions, the values of which are practically independent of

.

Despite this qualitative similarity, there are several quantitative differences between the concentration distributions at and . The size and location of the central region differ at , it shifts to the right and becomes smaller. In addition, although the central region is narrower at , the linear concentration distributions are steeper, since the concentration value at the boundary of the adjacent layer is significantly higher.

From the analysis of the concentration distributions, it can be concluded that the cross-section of the desalination channel consists of at least seven regions: two boundary layers, two regions of linear concentration variation, and one region of nearly constant concentrations, as well as two intermediate layers between the regions of linear variation and the constant region. To fully understand the significance of these regions, it is necessary to consider additional characteristics of the transport processes.

Furthermore, unlike the diffusion layer (for example, near the cation-exchange membrane), where the steady state may be nonequilibrium — that is, the salt-ion current may not equal zero, and therefore the cation concentration may decrease almost to zero — in the channel cross-section, the steady state can only be equilibrium. In other words, the salt-ion current is zero, which means that salt ions cannot be completely removed. Consequently, during the transport of and ions, the redistribution of salt ions occurs, but they are not carried beyond the channel boundaries.

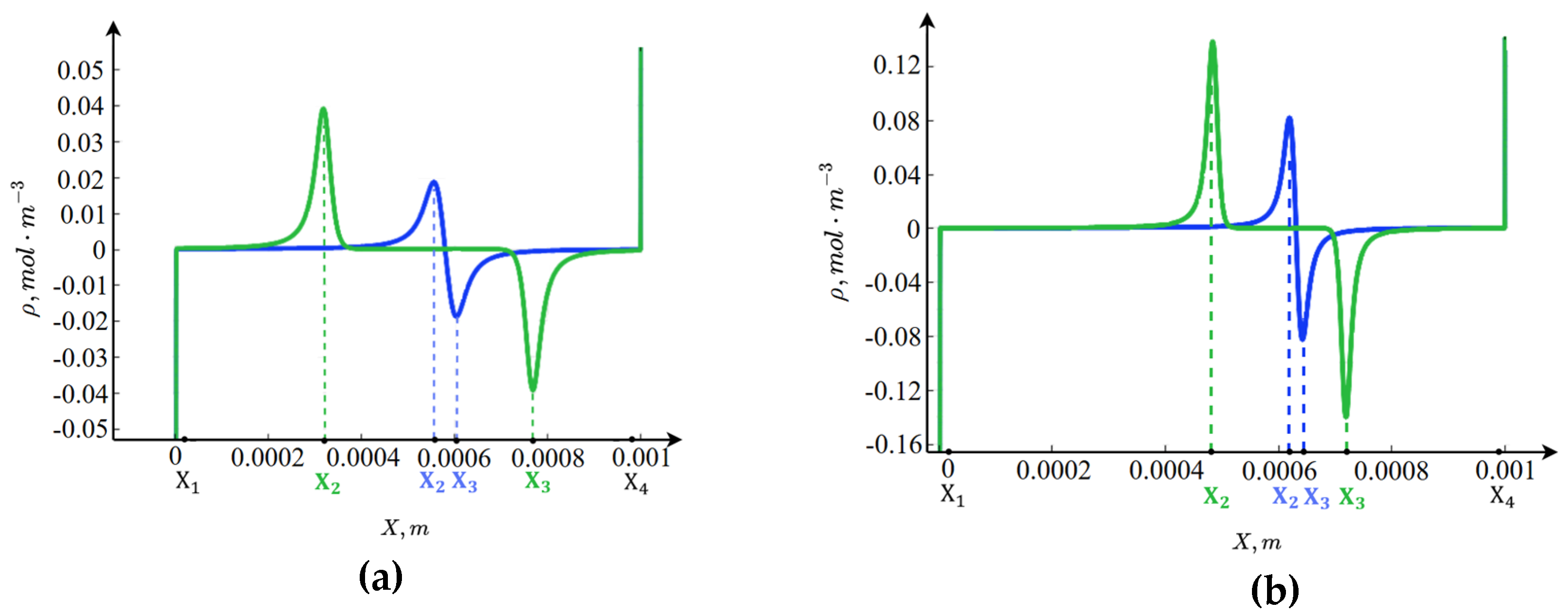

3.2. Spatial Charge Distribution

In

Figure 3, the spatial charge distribution shows that the channel cross-section can also be divided into seven intervals. The boundary layers represent regions of spatial charge associated with the properties of the interfacial boundary, that is, part of the conventional electric double layer [

24], with the anion-exchange membrane carrying a negative charge and the cation-exchange membrane a positive charge. In the regions of linear concentration distribution, the condition of electroneutrality is satisfied with high accuracy. In the central part of the channel, however, an additional region of spatial charge appears (internal boundary layers), which is not related to the interfacial boundaries. To explain the emergence of these internal boundary layers, it is necessary to consider the function

(the rate of water molecule dissociation/recombination reaction).

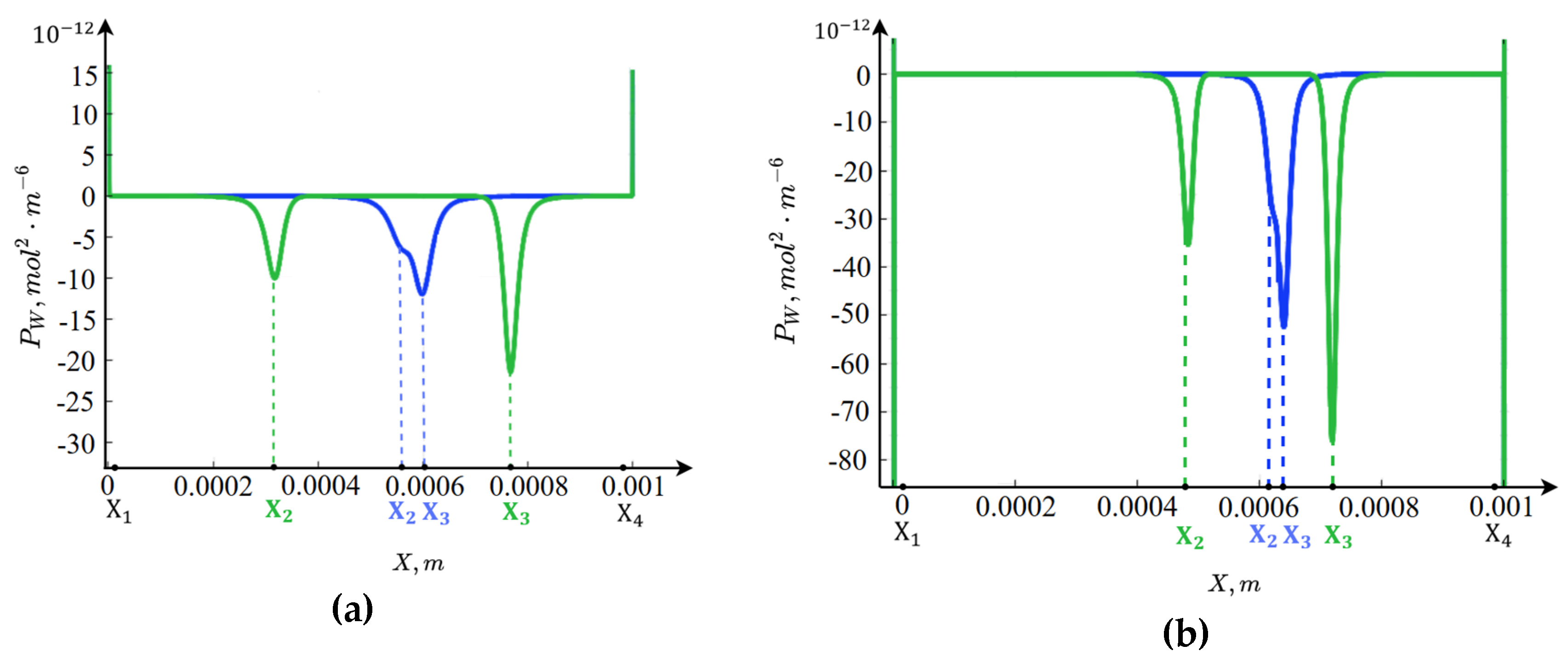

3.3. Graphs of the Equilibrium Function

Figure 4 shows that in the regions of spatial charge, within the boundary layers near the ion-exchange membranes, intense water molecule dissociation occurs, as the electric field strength in these regions reaches very high values. Moreover, for

, water dissociation is more intense than for

. In

, the ions

are completely transported through the anion-exchange membrane (boundary condition 19a), so their concentration is practically zero. At the same time, the concentration of ions

rapidly increases. The concentration of ions

decreases exponentially from

, while the concentration of (formula) remains practically zero.

In , the situation occurs in the opposite manner: the ions are completely transported through the cation-exchange membrane (boundary condition 12), so their concentration is practically zero. At the same time, the concentration of ions increases rapidly. The concentration of ions grows exponentially toward , while the concentration of remains practically zero.

The spatial charge concentration distribution in the central part of the channel, as shown above, significantly depends on the potential jump. Let us first consider the case when the potential is below the limiting value, for example, 0.3 V. In this case, a region forms in the central part of the channel where recombination dominates over dissociation; we will refer to this as the recombination region. The structure of the recombination region is almost symmetric with respect to the channel center for a solution, with a slight rightward shift, since the diffusion coefficients of potassium and chloride ions are nearly equal. However, for a solution, a significant asymmetry is observed because the diffusion coefficient of sodium ions is smaller than that of chloride ions.

A characteristic feature of this region Is the presence of a deep, single local minimum of the equilibrium function, caused by the dominance of recombination over dissociation. The minimum point is defined by the location where the hydrogen ion concentration equals the hydroxide ion concentration, which is why recombination is maximal at this point. To the left of the minimum point, the hydrogen ion concentration exceeds that of hydroxide ions. Since in the recombination region the concentrations of potassium and chloride ions are much lower than those of hydrogen and hydroxide ions, an excess of hydrogen ions occurs to the left of the minimum point, creating a region of positive spatial charge. Similarly, to the right of the minimum point, a region of negative spatial charge forms due to an excess of hydroxide ions.

From this, it can be concluded that the formation of the internal boundary layer of spatial charge is associated with the finite recombination rate. Specifically, ions approach from the left and ions from the right, and they recombine. Since the recombination rate is finite, albeit very high, not all ions recombine immediately, so they accumulate in a “queue” for recombination. This results in a positively charged spatial region on the left due to ions and a negatively charged spatial region on the right due to ions.

At a potential jump of

, a characteristic feature is the presence of two local minima in the equilibrium function (

Figure 4), which is due to the very high electric field strength between these points. This causes dissociation to be so enhanced that near-equilibrium conditions are almost reached between the two local minima of the equilibrium function.

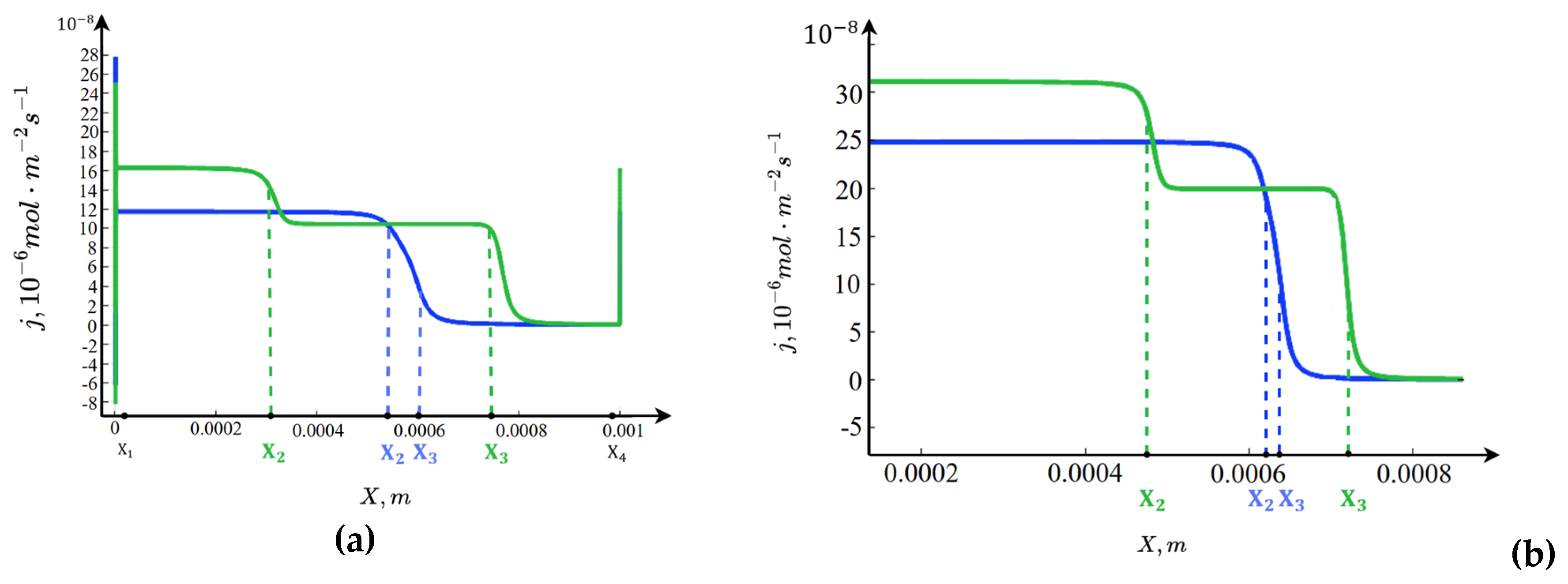

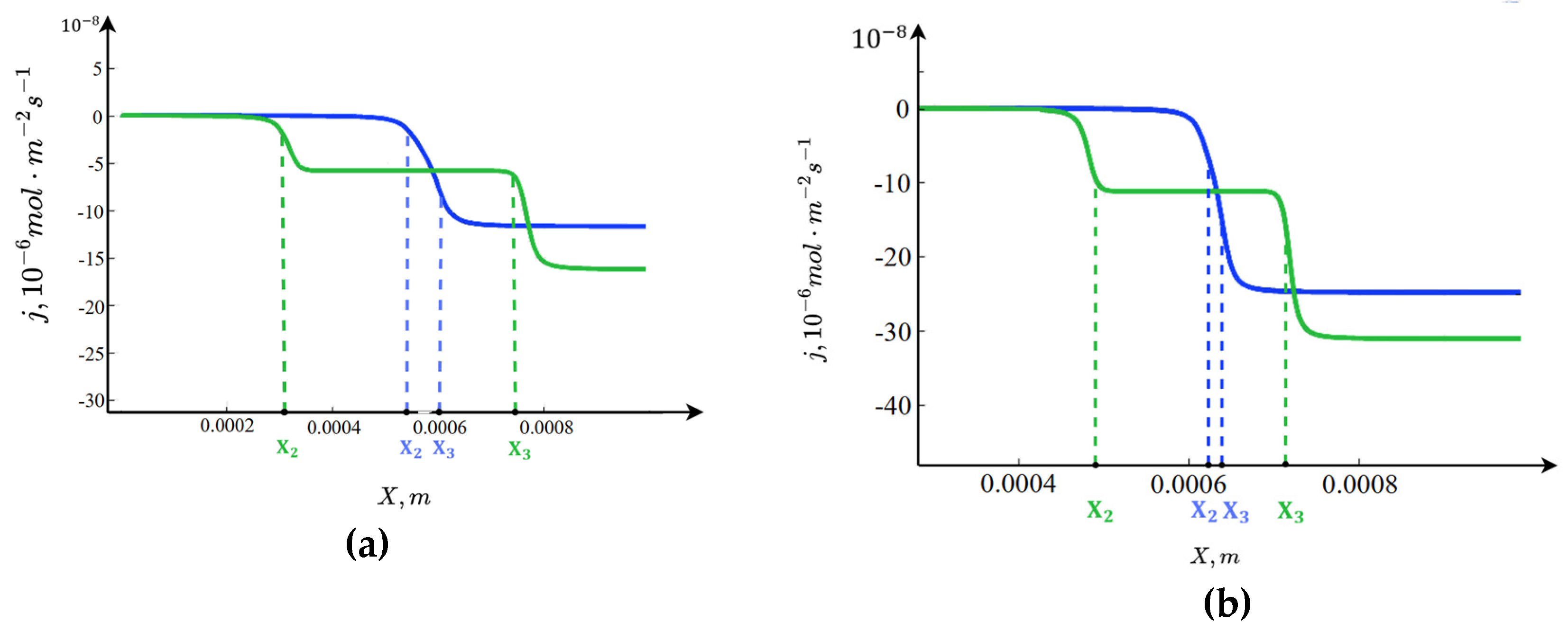

3.4. Graphs of the Fluxes () and ()

Figure 5 shows that accounting for the dependence of the equilibrium coefficient on the spatial charge leads to an increase in the fluxes: for

, the fluxes rise by an order of magnitude in the boundary layers near the membranes and approximately double in the central part of the channel. By selecting an appropriate value of

, the flux can be increased by 10–30 times, as observed in experiments shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 of [

21]. Thus, choosing the dependence of the equilibrium coefficient on the spatial charge, along with a proper fitting parameter

, allows for both qualitatively and quantitatively accurate description of the enhancement of the fluxes of the products of water molecule dissociation.

In the electroneutral region, one of the fluxes is zero while the other proportional to the current I. In the equilibrium region, where the concentrations are practically constant, both fluxes take constant values, which are different from zero. This leads to the formation of two boundary layers for each flux in the vicinity of points and .

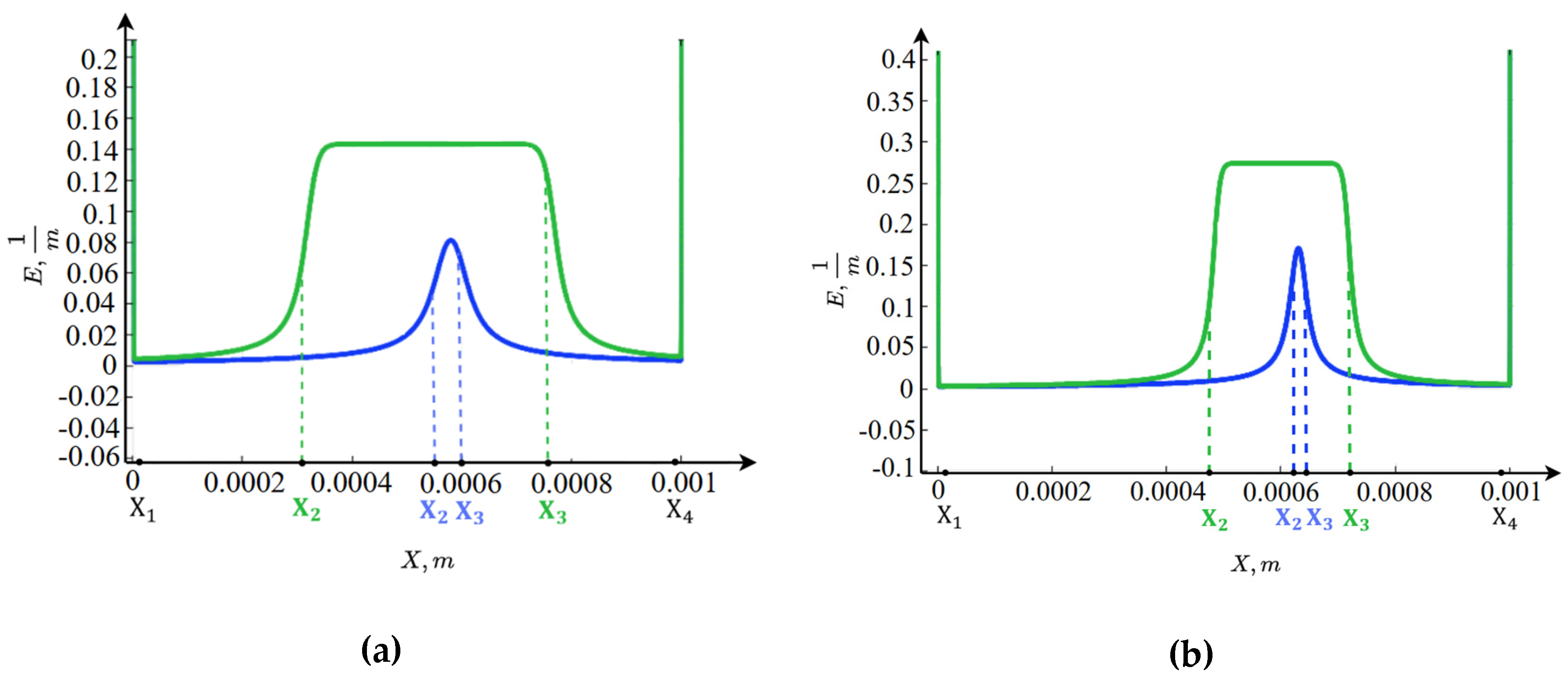

3.5. Graphs of the Electric Field Intensity

Figure 7 shows that the electric field intensity decreases numerically in the boundary layers with increasing parameter

. This is because, as noted above, the release of

ions at the anion-exchange membrane and

ions near the cation-exchange membrane is enhanced. Since the spatial charges near the anion- and cation-exchange membranes are negative and positive, respectively, the

and

ions reduce the magnitude of these spatial charges, leading to a corresponding decrease in the electric field intensity in these regions. To explain the increase in the electric field intensity in the middle of the channel, it should be noted that the concentrations in this region are constant and do not depend on

, while the fluxes increase. After a series of transformations, we obtain

.

Since the concentrations are practically constant,

, therefore

Thus, with an increase in b, the fluxes increase, the numerator grows while the denominator remains constant, and consequently, the electric field intensity increases proportionally with the fluxes.

3.6. Equilibrium Constant

For , the equilibrium constant is constant, whereas for it becomes variable and behaves similarly to the spatial charge, except that is positive and its maximum value depends on , increasing as increases. Thus, for , the equilibrium constant increased by approximately 57 times. It can be shown that by selecting , the maximum value of the equilibrium constant can be made arbitrarily large, which leads to an increase in the fluxes of and ions. The increase in and fluxes reduces the magnitude of the spatial charge near the anion- and cation-exchange membranes, since the signs of the spatial charge near the membranes and those of the and ions are opposite. This, in turn, diminishes the effect of the spatial charge on enhancing the fluxes of and ions, leading to a certain equilibrium. As a result, neither the electric field intensity nor the fluxes can increase indefinitely.

4. Structure of the Desalination Channel Cross-Section

From the analysis presented above, it is evident that the channel cross-section can be divided into seven intervals:

Boundary layers near the anion- and cation-exchange membranes, which are quasi-equilibrium regions of spatial charge for and their analogs for . In addition, there are two internal boundary layers of spatial charge, whose formation is associated with the recombination reaction of water molecules.

Between the two internal boundary layers, there is an equilibrium region where the concentrations and electric field intensity are constant. The electric field intensity in this region is relatively high, which is associated with the increased fluxes of and ions.

In the remaining two regions, the conditions of equilibrium and local electroneutrality are satisfied, with the concentration distribution being nearly linear.

Using this structure of the desalination channel cross-section, it is possible to obtain an approximate analytical, for example, asymptotic solution to the boundary-value problem.

5. Conclusions

The study established that in systems with monopolar membranes, the change in the equilibrium constant can be linked not merely to the electric field strength, but to the magnitude of the spatial charge. According to the proposed mathematical model, variations in the equilibrium constant lead to a significant increase in the fluxes of

and

ions. In particular, the equilibrium constant locally increases, for example, in the quasi-equilibrium boundary layer region, by a factor of 10–30, which is in the same order of magnitude as the experimental data [

21].

The work demonstrated that in the regions of spatial charge, within the boundary layers near the ion-exchange membranes, intense water molecule dissociation occurs, with higher values of the parameter leading to stronger dissociation. It was also shown that an internal boundary layer (the recombination region) forms deeper in the solution, associated with the recombination of and ions. Furthermore, that with increasing b the flows increase and the electric field strength increases proportionally.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.C. and M.U.; methodology, E.K.; software, R.N.; valida tion, A.K., N.C. and M.U.; formal analysis, E.K.; investigation, R.N.; resources, A.K.; data curation, N.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.U.; writing—review and editing, E.K.; visualization, R.N.; supervision, M.U.; project administration, E.K.; funding acquisition, A.K., N.C. and M.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barros KS, Scarazzato T, Pérez-Herranz V, Espinosa DCR. Treatment of cyanide-free wastewater from brass electrodeposition with edta by electrodialysis: Evaluation of underlimiting and overlimiting operations. Membranes. 2020;10(4). [CrossRef]

- Ran J, Wu L, He Y, et al. Ion exchange membranes: New developments and applications. Journal of Membrane Science. 2017;522:267-291. [CrossRef]

- Strathmann H. Electrodialysis, a mature technology with a multitude of new applications. Desalination. 2010;264(3):268-288. [CrossRef]

- Mareev SA, Evdochenko E, Wessling M, et al. A comprehensive mathematical model of water splitting in bipolar membranes: Impact of the spatial distribution of fixed charges and catalyst at bipolar junction. Journal of Membrane Science. 2020;603. [CrossRef]

- Pärnamäe R, Mareev S, Nikonenko V, et al. Bipolar membranes: A review on principles, latest developments, and applications. Journal of Membrane Science. 2021;617. [CrossRef]

- Valero, F.; Arbós, R. Desalination of brackish river water using Electrodialysis Reversal (EDR). Desalination 2010, 253, 170–174.

- Gudza V.A., Pismenskiy A.V., Urtenov M.K., et al. The influence of water dissociation/recombination on transport of binary salt in diffusion layer near ion exchange membrane Journal of Advanced Research in Dynamical and Control Systems. 2020. Т. 12. № S4. С. 923-935.

- Kirillova E., Chubyr N., Nazarov R., Kovalenko A., Urtenov M. Investigation of the boundary value problem for an extended system of stationary nernst–planck–poisson equations in the diffusion layer Mathematics. 2025. Т. 13. № 8.

- Burn, S.; Hoang, M.; Zarzo, D.; Olewniak, F.; Campos, E.; Bolto, B.; Barron, O. Desalination techniques —A review of the opportunities for desalination in agriculture. Desalination 2015, 364, 2–16.

- Chehayeb, K.M.; Farhat, D.M.; Nayar, K.G.; Lienhard, J.H. Optimal design and operation of electrodialysis for brackish-water desalination and for high-salinity brine concentration. Desalination 2017, 420, 167–182.

- Nayar, K.G.; Lienhard V, J.H. Brackish water desalination for greenhouse agriculture: Comparing the costs of RO, CCRO, EDR, and monovalent-selective EDR. Desalination 2020, 475, 114188.

- Al-Amshawee, S.; Yunus,M.Y.B.M.; Azoddein, A.A.M.; Hassell, D.G.; Dakhil, I.H.; Hasan, H.A. Electrodialysis desalination for water and wastewater: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 380, 122231.

- Campione, A.; Cipollina, A.; Toet, E.; Gurreri, L.; Bogle, I.D.L.; Micale, G. Water desalination by capacitive electrodialysis: Experiments and modelling. Desalination 2020, 473, 114150.

- Turek, M.; Laskowska, E.; Mitko, K.; Chor ˛a˙zewska, M.; Dydo, P.; Piotrowski, K.; Jakóbik-Kolon, A. Application of nanofiltration and electrodialysis for improved performance of a salt production plant. Desalination Water Treat. 2017, 64, 244–250.

- K. Nagasubramanian, F.P. Chlanda, K.-J. Liu, Use of bipolar membranes for generation of acid and base — an engineering and economic analysis, J. Membr. Sci. 2 (1977) 109–124. [CrossRef]

- G. Pourcelly, Electrodialysis with bipolar membranes: principles, optimization, and applications, Russ. J. Electrochem. 38 (2002) 1026–1033. [CrossRef]

- C. Huang, T. Xu, Electrodialysis with bipolar membranes for sustainable development, Environ. Sci. Technol. 40 (2006) 5233–5243. [CrossRef]

- Onsager, L. Deviations from Ohm's Law in Weak Electrolytes. J. Chem. Phys. 1934, 2(9), 599–615.Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Title of the chapter. In Book Title, 2nd ed.; Editor 1, A., Editor 2, B., Eds.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2007; Volume 3, pp. 154–196.

- Timashev, S.F. Physicochemistry of Membrane Processes; Khimiya: Moscow, Russia, 1988; 240 p.

- Sheldeshov, N.V. Processes Involving Hydrogen and Hydroxide Ions in Systems with Ion-Exchange Membranes, Doctoral Dissertation, Chemistry, Kuban State University: Krasnodar, Russia, 2002; 405 p. EDN: NNNGQN.

- Nikonenko, V.V.; Pismenskaya, N.D.; Volodina, E.I. Dependence of the Generation Rate of H+^++ and OH−^-− Ions at the Ion-Exchange Membrane/Dilute Solution Interface on the Current Density. Electrokhimiya 2005, 41(11), 1351–1357. EDN: HSIUHJ.

- Nazarov, R.R.; Kovalenko, A.V.; Bostanov, R.A.; Urtenov, M.Kh. Mathematical Modeling of the Influence of the Dissociation/Recombination Rate Constant on Salt Ion Transport in the Diffusion Layer at an Ion-Exchange Membrane. Vestn. Sam. Gos. Tekh. Un-ta. Ser. Fiz.-Mat. Nauki 2025, 29(1), 109–128. EDN: AZCCRJ. [CrossRef]

- Kovalenko, A.V.; Nikonenko, V.V.; Chubyr, N.O.; Urtenov, M.Kh. Mathematical Modeling of Electrodialysis of a Dilute Solution with Accounting for Water Dissociation-Recombination Reactions. Desalination 2023, 550, 116398. [CrossRef]

- Zabolotsky, V.I.; Lebedev, K.A.; Lovtsov, E.G. The Double Electric Layer at the Membrane/Solution Interface in a Three-Layer Membrane System. Electrokhimiya 2003, 39(10), 1192–1200.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).