1. Introduction

Research on safety accidents has long been hindered by the lack of unified, standardized, and reusable public datasets. Constructing high-quality datasets is fundamental for advancing related research. However, traditional methods are heavily reliant on manual collection and annotation, which are not only costly and inefficient but also struggle to meet the demands of large-scale applications. Compared to open-domain text tasks, accident-related corpora generally face challenges such as limited scale, diverse genres, and sparse annotations. Specifically, the challenges are as follows:

First, data sources are diverse and structurally varied. While authoritative channels (e.g., accident statistics and direct reporting systems) provide high accuracy, they often offer limited information, small scale, and dispersed distribution. On the other hand, semi-structured or unstructured texts from platforms like the internet, news reports, and internal documents, although containing rich accident details and large volumes of data, exhibit significant variation in writing objectives, stylistic features, and information granularity.Second, cross-document event alignment is difficult. Structured information usually records key attributes such as event time, location, losses, and responsible units, but many public texts obscure or omit these identifiable accident cues due to information compliance requirements.Third, the label distribution follows a long-tail pattern. A few high-frequency accident types dominate the majority of samples, while a large number of long-tail categories are underrepresented.

Therefore, effectively integrating multi-source heterogeneous data and leveraging structured information for scalable automatic annotation has become the core challenge in constructing accident analysis datasets. In the field of natural language processing (NLP), event linking aims to connect event mentions in text to corresponding event nodes in a knowledge base [

1], and has long been a focal point in evaluation tasks such as ACE and TAC. Compared to entity coreference, event linking faces greater technical challenges, and the research is relatively underdeveloped. The core difficulties include cross-source narrative differences, lexical diversity, local information loss, and global consistency constraints.

The development of event linking has evolved from early rule-based methods [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10] to traditional machine learning techniques [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15], and more recently to deep learning methods [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. With the rise of pre-trained large language models (LLMs), significant progress has been made in event linking methods based on reading comprehension [

21], knowledge distillation [

22], and instruction fine-tuning [

23]. However, most existing methods are built on assumptions of open-domain text and clear entity anchors, and often face fundamental issues such as mismatched granularity and missing anchors when dealing with strictly anonymized accident texts.

To address these challenges, this paper proposes an event linking method based on spatiotemporal containment consistency. Using structured records from accident statistics and direct reporting systems as anchors, the method accurately links event descriptions from open-domain texts. It models administrative levels and temporal granularity as a spatiotemporal lattice structure and introduces a probability fusion mechanism, integrating multi-factor confidence to output cross-document alignment probabilities with uncertainty measures, thereby effectively delineating the boundaries between samples for automatic annotation and those requiring human review. Additionally, based on spatiotemporal lattice constraints, a controlled data augmentation strategy using instruction-tuned large language models (LLMs) is introduced to automatically generate a large number of high-confidence labeled samples. Experimental results show that the proposed method can effectively align structured accident records with multi-source public reports, support scalable automatic annotation, and provide an expandable solution for efficiently constructing high-quality, auditable accident corpora. The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

1、A spatiotemporal containment consistency-based cross-document event linking method. By incorporating domain knowledge, a set of spatiotemporal and type consistency criteria is defined, anchor weights are computed using smoothing and monotonic projection, and a multi-feature fusion scoring model is developed to calculate the alignment probability between structured records and event mentions in internet texts.

2、A sample selection strategy that combines "maximum probability and probability gap." In an active learning framework, a selection criterion based on maximum alignment probability and probability difference is introduced, allowing for high-confidence automatic annotation while maintaining high recall. This provides quantifiable decision-making support for human-machine collaborative annotation.

3、The proposed method achieves performance comparable to the strongest baseline models in accident dataset construction tasks. It demonstrates its effectiveness and practicality across several key metrics.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work;

Section 3 describes the proposed model and methods in detail;

Section 4 introduces experimental design and datasets;

Section 5 analyzes experimental results;

Section 6 discusses the results and

section 7 discusses the limitations of the method and future directions, and concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

Event Linking is a core task that aims to associate event mentions in text with corresponding event nodes in a knowledge base [

1]. The key challenges lie in handling cross-source narrative differences, lexical diversity, local information loss, and global consistency constraints. Research in this field has generally progressed through several stages: rule-based and template-driven methods, graph models with global inference, supervised learning with neural representations, and end-to-end cross-document modeling methods driven by pre-trained language models (PLMs).

Early research mainly relied on rule-based and heuristic matching methods. For example, Humphreys et al. [

2] proposed a cross-document event alignment method based on template slots and rules, using "trigger word consistency + key argument overlap" as criteria for matching and suppressing erroneous matches through domain knowledge. Ahn [

3], from the perspective of event extraction task decomposition, emphasized the key influence of the "trigger word-argument" structure on event coreference and linking, pointing out the issue of error propagation from upstream recognition. Raghunathan et al. [

4] introduced a multi-round filtering algorithm in entity coreference, where rules are applied progressively from strict to broad to merge event mentions, a concept later introduced to the event linking task by Lu and Ng [

5], which significantly improved performance under limited data conditions. Cybulska and Vossen [

6,

7,

8] proposed the "event bag" representation method, encoding events as sets of attribute slots and introducing a weighted slot matching mechanism that balances interpretability and robustness. Hovy et al. [

9,

10] further explored the theoretical boundaries of event identity and proposed a three-tier classification system ("same, different, quasi-same"), providing a theoretical foundation for subsequent studies on coreference and hierarchical event relationships. Although rule-based methods have high precision and strong interpretability, their cross-domain generalization ability is limited and they struggle to handle implicit semantic relationships effectively.

Graph-based methods model event mentions as nodes in a graph, with edges representing semantic similarity, and achieve global consistency clustering using spectral clustering, min-cut, or graph propagation algorithms. Chen and Ji [

11] proposed a two-stage framework ("feature combination → graph construction → graph partitioning"), which clearly defined the path for cross-document event linking as "local scoring followed by global partitioning." In their subsequent work [

12], they used min-cut criteria to explicitly partition event clusters, alleviating the local-global inconsistency problem. Lee et al. [

13] constructed a bipartite graph structure for entities and events, performing joint reasoning through shared arguments and optimizing clustering quality with an incremental merging strategy, significantly improving the accuracy and interpretability of cross-document alignment. Choubey and Huang [

14] proposed an iterative expansion strategy based on argument consistency, gradually merging high-confidence event pairs and updating similarity, significantly improving recall, particularly in multi-source news scenarios. Yang et al. [

15] proposed a hierarchical generative model based on non-parametric Bayesian methods, guiding clustering structure through prior constraints, avoiding dependency on the number of clusters. The core advantages of graph methods are their global consistency and information propagation capabilities, but their performance heavily depends on the accuracy of initial similarity estimates and faces high computational complexity in large-scale scenarios.

With the introduction of annotated corpora such as ECB+[

24] and KBP[

25], data-driven methods have gradually become mainstream. Supervised learning methods typically treat event linking as a mention classification or clustering task and integrate features such as trigger words, semantic classes, and syntactic structures. Chen et al. [

26] proposed a multi-parser ensemble framework to enhance the robustness of mention determination. Lu et al. [

27,

28] systematically explored joint reasoning and joint learning methods, using Markov logic networks and multi-task learning to improve global consistency, and introduced a probabilistic ranking mechanism to alleviate global inconsistency. Bejan and Harabagiu [

29,

30] proposed an unsupervised event coreference model based on non-parametric Bayesian methods, using semantic resources such as FrameNet, achieving performance comparable to supervised methods on open-domain texts. Araki and Mitamura [

31] jointly trained trigger word recognition and event coreference using a structured perceptron, significantly reducing error propagation; Araki et al. [

32] also proposed fine-grained evaluation recommendations for certain coreference phenomena. Upadhyay et al. [

33] systematically reflected on cross-document evaluation metrics and advocated for multi-metric evaluation to comprehensively assess model performance. Supervised and generative methods have effectively improved feature fusion and global reasoning capabilities. Joint learning and ranking optimization provide important pathways for moving from local matching to global clustering.

Neural network methods significantly reduce the dependence on feature engineering through representation learning and end-to-end training. Kenyon-Dean et al. [

16] employed clustering regularization to train a BiLSTM encoder, bringing similar events closer in the representation space, thereby enhancing model robustness. Peng et al. [

17] jointly handled event detection and coreference under weak supervision, offering a feasible solution for high-cost annotation tasks. Barhom et al. [

18] extended the span representation and cascade clustering mechanism from entity coreference to event linking, achieving advanced performance on the ECB+ dataset, and simplifying the traditional pipeline framework. Cremisini and Finlayson [

19] systematically compared and found that reasonable negative sampling and threshold settings could achieve strong baseline performance, while some complex modules contributed minimally. Allaway et al. [

20] proposed a sequential cross-document coreference method, reducing inference complexity through state memory and historical consistency constraints, making it suitable for large-scale scenarios. The core advancement of neural methods lies in transferable semantic representations and end-to-end optimization mechanisms, while sequential reasoning further improves computational efficiency.

The emergence of pre-trained language models such as BERT has significantly enhanced semantic alignment and context modeling capabilities. Joshi et al. [

34] applied BERT to entity coreference tasks and demonstrated the advantages of pre-trained models in cross-sentence contexts. They later strengthened phrase-level representations through span masking strategies in event structure modeling [

35]. In cross-document environments, Cattan et al. [

36] proposed a cross-document coreference framework combining long-document Transformers. Yu et al. [

37] utilized a shared encoder to jointly learn event and argument representations, emphasizing the importance of structural information for alignment tasks. Zeng et al. [

38] introduced paraphrasing resources and argument-aware embeddings to alleviate matching issues caused by lexical diversity. Caciularu et al. [

39] proposed a Cross-Document Language Model (CDLM) that significantly improved the model's ability to capture consistency through multi-document masking pre-training. Longformer [

40] and other long-text models have also been widely used for document-level encoding. Key advances in the pre-trained language model era include cross-document pre-training, span-level semantic enhancement, and long-context encoding, which have significantly improved the handling of lexical diversity and semantic equivalence.

In recent years, large language models (LLMs) have introduced new ideas for event linking. Some studies [

41,

42] evaluated the performance of GPT-series models in zero-shot and few-shot information extraction tasks, finding that while LLMs perform well in simple scenarios, they still significantly lag behind specialized models in more complex tasks. Some work attempts to combine the semantic summarization ability of LLMs with the specialized fine-tuning of small models (SLMs). For example, Min et al. [

21] used GPT-4 to generate event summaries, then employed SLMs for coreference resolution. Nath et al. [

22] generated reasoning explanations with LLMs and distilled them into smaller models to improve interpretability and performance. Wang et al. [

23] used instruction fine-tuning to unify multiple extraction tasks, while Ding et al. [

43] enhanced the model's sensitivity to semantic differences by utilizing counterfactual samples.

Although these LLM-based methods have achieved leading results on several benchmarks, research [

21,

42] also indicates that prompt-based methods struggle to cover complex annotation standards, and LLMs still show lower accuracy in event coreference compared to supervised models. Bugert et al. [

45] found that feature engineering methods perform more robustly in cross-corpus testing, while neural models have poor generalization ability across domains. These studies suggest that, despite LLMs' powerful world knowledge, when constructing annotation systems, it is essential to incorporate corpus features and design appropriate constraint mechanisms to achieve a higher cost-performance ratio in annotation results.

3. Methodology

To address the issues of weakened explicit cues in publicly available power accident texts due to anonymization, as well as significant genre and structural differences in cross-source texts, this paper proposes an event linking method based on spatiotemporal containment consistency. The method uses structured records from accident statistics and direct reporting systems as anchors to achieve accurate linking with event description fragments in open-domain texts. The overall process includes four core modules: feature extraction, consistency calculation, probability fusion, and decision output.

First, administrative levels and temporal granularity are modeled as a spatiotemporal lattice structure, and a set of spatiotemporal and type consistency criteria is defined based on domain knowledge. Next, anchor weights for each criterion are calculated through smoothing estimation and monotonic projection. Then, a multi-feature fusion scoring model is constructed, which integrates multi-factor confidence and outputs cross-document alignment probabilities with uncertainty measures. Finally, an active learning framework is used to combine a sample selection strategy based on "maximum probability and probability gap," effectively delineating the boundary between automatically labeled samples and those requiring human review.

Additionally, based on the spatiotemporal lattice constraints, a controlled data augmentation strategy using instruction-tuned large language models (LLMs) is introduced, which can automatically generate large-scale, high-confidence labeled samples. The subsequent sections of this chapter will formalize the definition of each component of this method and provide a detailed explanation.

3.1. Symbol and Object Definitions

Let the set of accident records be , where each record is an anchor event from the structured database, containing three types of elements:

1)Spatiotemporal elements, including the spatial location, where,,, and represent the four administrative levels (province, city, district, street/town) as vectors, and the time interval (start time, end time).

2)Enumerative non-spatiotemporal elements , such as accident level, accident type, and work scenario, where each field corresponds to a hierarchical tree based on industry standards, satisfying .

3)Structural elements, such as personnel casualties, economic losses, etc., which are represented as discrete vectors (missing components are masked).

Let the set of accident texts from the internet and industry channels be , where each text contains an accident summary paragraph and some scattered information. Various candidate sets for accident elements are extracted using rules and regular expressions:Spatial candidate set (each candidate is a four-level administrative vector, with missing levels marked as );Temporal candidate interval set (start and end times for candidates);Enumerative field candidate set ;Structured vector (empty if not mentioned).

All candidates are accompanied by extraction confidence scores, with spatial, temporal,and enumerative fields denoted as , , respectively.

The goal of cross-document accident linking is to find the corresponding accident record from the anchor record set for each , and output the alignment probability . If exceeds a threshold and the gap to the second-highest score is greater than , automatic labeling is performed; otherwise, the sample is sent for human review. The threshold and gap are dimensionless constants used to control false positive rates and review costs.

3.2. Spatiotemporal Lattice Structure and Consistency Criterion Modeling

One of the core innovations of this paper is the modeling of administrative levels and temporal granularity as a spatiotemporal lattice structure, on which consistency criteria are defined. Spatiotemporal containment consistency includes both spatial and temporal consistency.

Spatial consistency: Based on the containment and common ancestor branch relationships of administrative levels. The spatial relationship between the text candidate

and the record location

is defined as:

Where:

EXACT indicates that the four administrative units are exactly the same.

ANCESTOR indicates that they are consistent at a higher administrative level, but lacks finer level information.

COUSIN means they belong to the same higher-level unit but different lower-level units.

DISJOINT means there is no relationship (other cases).

The corresponding weights for the five temporal relationships are

, and the temporal compatibility is defined as:

Where represents the possible spatial candidates in the text, and computes the spatial relationship between the current spatial candidate and the record's location. The weights adjust the spatial relationship based on the specific attributes of the data, while reflects the confidence or importance of each spatial candidate.

Temporal consistency: Based on the containment relationships between time intervals. For a text candidate interval

and the record interval

, the temporal containment relationship is defined as:

Where:

EXACT indicates the two intervals are exactly the same.

CONTAINS means the text candidate interval [a,b][a,b][a,b] contains the record interval .

OVERLAP means the intervals overlap but neither fully contains the other.

AFTER means , the text candidate starts after the record interval ends.

DISJOINT means the intervals have no relationship.

The corresponding weights for the five temporal relationships are

, and the temporal compatibility is defined as:

Where

reflects the confidence or importance of each temporal candidate, and

calculates the temporal relationship between the candidate and the record’s time span.

Non-spatiotemporal consistency: For enumerative fields (e.g., accident level, accident type, work scenario), hierarchical trees

represent the categorical structure. For a text candidate

and a record value

, the distance on the tree

(dimensionless) is calculated, and non-spatiotemporal consistency is measured using an exponential kernel function:

Where

controls the decay rate. If the field is not mentioned in the text,

to avoid penalizing the absence.

Structural information consistency: This criterion addresses matching challenges caused by missing or ambiguous numeric information (e.g., casualties, economic losses) in accident texts. Traditional methods often fail or lead to misjudgments due to incomplete information. This paper employs a masked 1-norm to measure the difference, introducing a masking mechanism and a difference decay function to transform numerical comparisons into a more fault-tolerant probabilistic measure:

Where

is the mask vector, and

represents the Hadamard product.

is the scaling factor, where a larger value results in a faster decline in compatibility with increasing difference. When the text has no structured information due to anonymization, no penalty is applied, i.e.,

, granting the highest compatibility and allowing other features (e.g., time, location, type) to dominate in matching.

The spatiotemporal lattice structure and consistency criteria above enhance the system’s ability to adapt to noisy real-world data, providing stable and interpretable consistency judgments even in incomplete information environments.

3.3. Weight Estimation and Monotonic Projection

To convert discrete relationships into comparable numerical weights, this study adopts the Laplace (Lidstone) smoothing method [

46] . This method improves the stability of weight estimation when the sample size is small. Laplace smoothing is a common frequency estimation regularization technique widely used in text classification, language modeling, and record linking tasks [

47]. The core idea is to smooth empirical frequencies by introducing prior information to avoid extreme probability estimates of 0 or 1 due to insufficient samples, thus enhancing the robustness of the data fusion process [

46].

Let

be a discrete relationship category. In this category, the number of positive examples in the calibration set is denoted as

, the number of negative examples is

, and the total number is

. If empirical frequency

is directly used, extreme estimates or high variance can occur when the sample size is small. Therefore, this paper uses the Beta-Bernoulli model [135] for smoothing. The prior is set as

, where

is the pseudo-count, and the posterior expectation is:

This estimate approaches the empirical frequency when the sample size is large, and when the sample size is small or unobserved, it tends to the prior mean. The parameter can be adjusted within a small range (e.g., 0.5 or 1) to balance the smoothing intensity with the data-driven influence. The final is a dimensionless compatibility measure that can be directly used in subsequent fusion steps.

Some relationships between features have an explicit order of strength. For example, temporal relationships generally satisfy "Exact match ≥ Upper-level containment ≥ General overlap ≥ After official ≥ Disjoint," and spatial relationships usually satisfy "Exact match ≥ Upper-level containment ≥ Same ancestor, different branches ≥ No relation." Due to sampling fluctuations, independently smoothed weights may violate this order. To ensure interpretability and monotonicity, the weight sequence within the same feature group must be monotonically projected. This paper adopts isotonic regression [

48] to find the closest non-increasing (or non-decreasing) sequence to the original estimates under given order constraints. Let the sorted weight vector be

, the optimization problem is solved as:

This problem can be efficiently solved using the PAV (Pool-Adjacent-Violators) algorithm [

49]. After projection, the resulting

is the final weight, reflecting the data trend while strictly adhering to the prior strength relationships in the domain.

It should be noted that the above method is not only applicable to temporal and spatial relationships, but can also be used for other discrete mappings that require weighting. For example, relationships such as "same level / same ancestor / across branches" in enumerative non-spatiotemporal fields (e.g., accident level, accident type, etc.) can be smoothed using the Beta-Bernoulli model to obtain stable weights, and then the order can be fixed through monotonic projection. Structured consequence fields are not discrete relationships, and their numeric compatibility has already been given in the previous section via masked distance-exponential mappings, so they can be directly treated on the same dimensionless scale as discrete weights.

The output of this section is a stable and comparable compatibility table for each discrete relationship. This result will serve as the input to

Section 3.4, where it will be fused with other continuous compatibility values. Through this process, statistical robustness and monotonicity are ensured at the input stage, and cross-feature tradeoffs and global calibration are achieved at the fusion stage, thus reducing training burden and enhancing the overall reliability and interpretability of alignment probabilities.

3.4. Multi-Feature Scoring Model

This section aims to fuse the compatibility values of different features on the same scale and output a calibrated alignment probability. Through the weight estimation and monotonic projection methods described in the previous section, various discrete relationships have been mapped to stable and dimensionless compatibility values. Based on these pre-processed features, the fusion module learns the interaction and trade-off mechanisms across features. The model structure is lightweight, highly interpretable, and maintains a monotonic non-decreasing property for each input component.

For any candidate pair

, the input vector is defined as:

Where and represent spatial and temporal compatibility, respectively; represents the compatibility of the -th enumerative non-spatiotemporal field (with fields); is the compatibility for structured fields; is the semantic compensation term. The input dimension is .

To enhance numerical stability, a log-odds transformation is applied to each dimension:

Where is a small constant.

The fusion module uses a single hidden-layer feedforward architecture, ensuring non-negative weights and using non-decreasing activation functions to maintain monotonicity. The hidden layer width is denoted as

, with trainable parameters including

,

and

. The weights are processed using the softplus function to ensure non-negativity:

The forward propagation process is as follows:

Due to , and the softplus function being monotonically increasing, the output remains non-decreasing as increases. This ensures that an increase in any individual feature's compatibility will not decrease the overall score.

The alignment probability is calibrated using a temperature scaling method:

Where

is the sigmoid function,

is the bias, and

is the temperature parameter. The parameters

are determined by minimizing the log loss or Brier score on the validation set, ensuring that the probability output matches the actual hit rate. The final output

is a dimensionless probability value.

The model is trained using a small-scale alignment labeled dataset, including human-verified samples and high-confidence pseudo-labeled samples. The loss function uses binary cross-entropy with an additional

regularization term:

Where

is the alignment label, and

is the regularization coefficient. The Adam optimizer is used with an early stopping strategy. The hidden layer width

is typically set between 8 and 32 to control model capacity. After training, feature importance can be evaluated using local sensitivity or integrated gradients.

3.5. Inference, Decision-Making, and Uncertainty

At the inference stage, let the alignment probability between text

and candidate record

be

. Define the Bag-Level Strength and Probability Gap as:

Here, represents the confidence of the most probable match, and indicates the separability between the top two candidates. The actual decision adopts a dual-threshold rule:

When and , automatically align to .

Otherwise, mark it as “requiring human review.”

The thresholds and are jointly optimized on the validation set to balance false positive rates and review costs. This mechanism effectively prevents cases where confidence scores are generally high but the decision remains uncertain, or where two candidate probabilities are close and difficult to distinguish.

For candidate pairs with evident conflicts, a one-time score penalty is applied before probability computation to prevent severely inconsistent matches from obtaining high probabilities. Specifically, if the temporal relationship is AFTER or DISJOINT and the spatial relationship is also DISJOINT, subtract a fixed constant γ>0\gamma > 0γ>0 from the score obtained in

Section 3.3, then perform temperature scaling to calibrate the adjusted probability

. The value of

is determined on the validation set to ensure the penalty only applies to extreme conflict cases without affecting normal matches.

When multiple texts point to the same record and all satisfy the automatic alignment conditions, record merging is necessary to avoid duplicate counting. Let the set of such texts be:

If , sort by in descending order, retain one as the primary sample, and merge the remaining as auxiliary samples under the same accident entry, preserving source and timestamp information. This merge operation does not alter the original annotations but is used for de-duplication and sample weight control.

To facilitate long-term system operation and auditing, the inference process should record the following metadata: the discrete relationship categories and smoothed weights of candidate pairs; all compatibility scores ; input feature vectors; fusion module scores; the final probabilities or ; the values of and ; decision labels; and merge identifiers. This metadata can be used for error attribution, threshold estimation, temperature parameter recalibration, and rule adjustments for specific error patterns (e.g., “temporal compatibility but frequent location conflicts”). In addition, to ensure the interpretability of probabilities, the Brier score and expected calibration error should be continuously monitored. If deviations are observed between the predicted probabilities and the actual hit rate, the temperature scaling parameters can be re-estimated without retraining the fusion module.

3.6. LLM-Based Data Augmentation

Let denote the set of samples automatically aligned with high confidence in the training slice. From this, further select a high-confidence subset satisfying and . For each sample , constrained generation is performed using a knowledge base containing domain terminology and entity hierarchical relations.

Define the entity set

, the hierarchical ontology of enumerative fields as

(tree structure or directed acyclic graph), and establish a mapping

to map entities to category nodes, while introducing hierarchical relation operators

and

. For any text

, augmented samples are generated by an instruction-tuned generator

under a specified template or prompt

:

The generation process encompasses three types of controlled transformations: same-class entity substitution, parent–child (hypernym–hyponym) rewriting, and knowledge-guided prompt generation. To ensure the reliability of the augmented textual data, its feature scores and matching probabilities must be recalculated. Only when the alignment results remain consistent and the consistency scores of key elements do not decrease beyond a predefined tolerance will the augmented text be officially incorporated into the training set.

3.7. Model Training and Implementation Details

The training process is divided into two stages. In the first stage, a small number of manually verified samples together with high-confidence samples obtained through strict rule-based filtering are used to lightly train the monotonic combiner described in

Section 3.4, producing the initial probability outputs. Combined with the dual-threshold rule of

Section 3.5, this completes the first round of large-scale automatic annotation. Based on the accident occurrence time, the data are then split into the training set

, validation set

, and test set

. In the second stage, only the fusion module is fully trained and calibrated on

, at which point training samples augmented by instruction tuning are incorporated; the validation and test sets are not subjected to augmentation or prior re-estimation, but are used solely for hyperparameter adjustment and temperature scaling.

The experiments are conducted in Python 3.10 with PyTorch 2.x, using fixed random seeds and version control for both data and models. After sorting the data by accident occurrence time and de-duplication, the dataset is divided into training, validation, and test sets. A unified preprocessing pipeline is applied, including:

Text normalization (standardizing numbers and units, and normalizing time expressions and place names);

Feature extraction (temporal anchors and granularity, administrative levels of locations, enumerative field nodes, accident consequence vectors, and sentence semantic similarity);

Consistency score computation and caching (columnar storage indexed by sample–candidate pairs).

Candidate retrieval is implemented using an inverted index based on time windows, administrative levels, and event types, and the number of candidates per text is limited to .

The first-stage training uses the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of , weight decay of , batch size of 256, and an early-stopping threshold of five epochs. The input consists of the log-odds transformations of the consistency scores, and a single-hidden-layer monotonic network with softplus activation is used to ensure non-negative weights. The loss function is a weighted cross-entropy with regularization.

After the initial round of automatic annotation and data partitioning, the second-stage training begins: only the training set undergoes instruction-tuned augmentation, and the augmented samples are incorporated with a weight . The validation set is used for hyperparameter selection and for fitting the temperature scaling parameters ; the test set is used solely for the final evaluation. Inference and training follow the same pipeline. To improve efficiency, static fields and intermediate consistency scores are cached and batch matrix operations are used. At the same time, key information such as consistency scores, matching probabilities, and threshold decisions is recorded to ensure that results are auditable and reproducible.

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Data Sources and Processing

The experiments use two types of data. The first consists of structured records exported from an accident statistics system, denoted as . Each record contains the following elements: a location hierarchy vector ; a time interval ; a set of enumerative non-spatiotemporal fields ; and a structured vector .

The second type consists of text data crawled from multiple public websites. The texts undergo character normalization, sentence segmentation, and rule-based extraction. Specifically, Chinese numerals and dates are normalized; temporal expressions are extracted and mapped to closed intervals; spatial fields are normalized to standard place names and addresses, identifying province, city, district/county, and street (or town) as four levels. Enumerative non-spatiotemporal fields are standardized with dictionary backfilling, mapping synonyms and aliases to the same node in the domain hierarchy tree . Structured fields (such as accident casualties) are extracted and normalized into casualty and loss components, with missing parts masked as non-comparable.

Subsequently, regular expressions are used for candidate extraction: temporal expressions are parsed into a closed interval set ; location names are mapped to an administrative-level set ; enumerative fields are aligned to the domain hierarchy tree ; and structured information is extracted into a masked vector . To prevent time information leakage and ensure the rigor of model evaluation, the data are split under a strict non-overlapping chronological strategy: earlier periods are used for model training and validation, while later periods are reserved exclusively for testing. This improves the model’s ability to generalize to unseen time spans and adapt to distributional shifts, thus enabling a realistic and objective assessment of its robustness in temporal extrapolation tasks.

4.2. Baseline Models

This study selects baseline models under a small-sample, two-stage training and calibration setting. All comparison methods share the same data splits, candidate generation pipeline, and evaluation protocol as the proposed method. On the input side, accident summary texts are uniformly used as the alignment target, while direct-report records are converted into brief descriptions by concatenating structured elements (time, location, category, casualties, etc.) as the alignment reference. On the output side, ranking quality, classification quality, and probability calibration quality are reported uniformly, and thresholds and temperature scaling parameters are determined only on the validation set.

To ensure reproducibility and fairness, the baselines adopt the same processing and annotation pipeline as the proposed method (symbol and object definitions, consistency score computation, dual-threshold decision rules, etc.) and maintain the same candidate pool size and recall target. This unified setup guarantees comparability under the same task formulation, reducing biases introduced by differences in data handling or engineering components.

The rule–probability baseline implements event linking under the Fellegi–Sunter (F-S) probabilistic record-linkage framework [

50]. It maps each summary–record sample to a field-level comparison vector, separately evaluating time interval relations, administrative-level containment relations, hierarchical distances of enumerative non-spatiotemporal elements, and consistency of structured vectors, then computing discrete or continuous evidence components. Based on a small calibration set, it estimates the conditional distributions of true matches and non-matches to generate likelihood ratios and produces “match,” “non-match,” or “undecided” judgments via upper and lower thresholds. This method focuses on element-level evidence, offering an interpretable performance upper bound suitable for evaluating the limit when only structured consistency is used. The implementation retains interpretability for each component and jointly tunes thresholds and rejection strategies on the validation set to remain consistent with the probability calibration and risk-control standards of the proposed method.

The retrieval–re-ranking baseline uses the Cross-Document Event Coreference Search (CDECS) method [

51], which transforms cross-document event coreference into a retrieval–ranking task and supports zero-shot or small-sample processes. Candidate recall is performed by an unfine-tuned general semantic encoder, followed by lightweight threshold adjustment and temperature scaling on the validation set for calibration. In this task, the accident summary is encoded as a query vector, and the textualized description of direct-report records is encoded as a library vector; nearest-neighbor recall is first performed, then similarity scores or a lightweight classification head are used for ranking and probabilistic scoring.

The zero-shot linking baseline employs the dual-tower dense retrieval model from the BLINK framework [

52]. BLINK decomposes the “mention–entity linking” task into dual-tower retrieval and cross-encoder fine ranking, relying primarily on entity description texts rather than task-specific supervision, thus operating in zero-shot conditions. For this task, direct-report records are normalized into event-element descriptions (short texts of time, location, category, consequences, etc.) to build the vector index; accident summaries are encoded as query vectors for Top-

candidate retrieval and ranking, and similarity is mapped to probabilities via temperature scaling on the validation set.

The generative zero-shot decision baseline adopts the Argument-Aware Event Linking (AAEL) method [

53]. Without human annotation, it uses argument-aware prompts to structure the input so that the model focuses more on matching time, location, and participants during ranking. Applied to this task, summary–record pairs are filled into a prompt template, and the model outputs a judgment on whether they describe the same event and a brief rationale, which is then converted into a probability via temperature scaling to align with the evaluation standard of this paper. This baseline tests the transferability and potential risks of large language models in cross-document event linking under low-supervision conditions.

The teacher–student distillation baseline uses an LLM-based method proposed at NAACL 2024 [

54]. Its core idea is to have an autoregressive large language model generate free-text rationales as distant-supervision signals and distill them into a lightweight student model, thereby improving cross-document event coreference performance without increasing manual annotation. In this task, the teacher model generates alignment/non-alignment rationales and soft labels for summary–record samples, while the student model trains a classification head under small-sample conditions using a joint loss (hard-label cross-entropy plus soft-label KL divergence[

55]). During inference, only the student model is used, with temperature scaling on the validation set. This baseline operates stably under few-label and pseudo-label settings and can test the feasibility and benefits of transferring teacher-model capabilities and achieving efficient student-model inference.

Together, these five baselines cover interpretable evidence-based probabilistic linking, retrieval–re-ranking under general semantic paradigms, dense retrieval zero-shot linking, argument-aware generative re-ranking, and “free-text rationale + distillation” low-annotation paradigms. All have peer-reviewed empirical results on public benchmarks (e.g., ECB+ [

24]) and require only minimal adaptation when transferred to the one-to-one “accident summary–direct report” alignment task, making them suitable references under the small-sample and zero-shot conditions of this study.

4.3. Parameter Settings

Parameter settings include only points directly related to experiment reproducibility and adopt consistent selection principles across methods whenever possible. All methods share the same data splits, extractor versions, and candidate generation pipeline. Candidate pool size is determined on the validation set according to the criterion of “minimizing the average number of candidates while ensuring target recall,” and is kept unchanged on the test set. All probability outputs use temperature scaling with parameters fitted once on the validation set to minimize log loss or the Brier score; no adjustments are made during testing.

Text truncation strategies are kept consistent across methods: only “accident summary” and “record synopsis” are used, with priority given to preserving time, location, and key numerical expressions to avoid biases introduced by length differences.

For the Fellegi–Sunter baseline, key parameters include the prior smoothing strength of components and the likelihood ratio thresholds. Component conditional distributions are estimated from the small calibration set using symmetric Beta–Bernoulli smoothing, and the smoothing coefficient is selected on the validation set by grid search to jointly optimize the Brier score and ECE. For time and administrative-level relationships, component weights are subjected to isotonic projection using equidistant regression to preserve the order of strength. The likelihood ratio adopts joint upper and lower thresholds, with threshold selection primarily maximizing F1 while controlling the false positive rate within a preset range on the validation set. The log-likelihood ratio is linearly mapped to log-odds before temperature scaling to ensure comparability of probability outputs across methods.

For the CDECS baseline, the core parameters are the encoder, similarity temperature, and recall depth. The encoder uses a publicly available general semantic model and remains frozen; similarity is fitted to a single temperature parameter on the validation set to map cosine similarity stably to log-odds; recall depth matches the candidate pool size, with no separate optimization per method to avoid selection bias. If small-sample fine-tuning is required, only a few contrastive learning steps are performed on positive–negative pairs from the calibration set, with learning rate and steps chosen on the validation set; if no fine-tuning is performed, the encoder remains frozen and only temperature and thresholds are fitted on the validation set.

For the BLINK dense retrieval baseline, zero-shot operation is emphasized. The dual-tower encoder uses public weights and remains frozen, the entity side (here, the “record synopsis” side) builds the vector index, and the query side is the “accident summary.” Under zero-shot settings, the cross-encoder re-ranking is disabled, relying only on dual-tower similarity ranking, with temperature scaling and threshold fitting on the validation set. Approximate retrieval parameters of the index are aligned with the candidate pool size, and no additional model-specific tuning is performed. If minimal adaptation is applied, it is limited to standardizing the textual format of “record synopsis” templates within the validation set without updating encoder parameters.

For the LLM-based zero-shot re-ranking baseline, a deterministic inference configuration is used to reduce variance. The generation temperature is set to zero or near zero, sampling is disabled, and the maximum generation length is sufficient to cover the judgment and brief rationale. Inputs use a fixed pairwise template explicitly specifying time, location, and field elements; outputs are parsed into binary decision scores, then normalized to probabilities on the validation set using logistic regression or temperature scaling. To avoid prompt drift, the template remains unchanged throughout the experimental period; if refusals or “cannot judge” outputs occur, they are uniformly treated as the lowest-confidence negative examples and this rule is consistently applied on the validation set without ad hoc modifications on the test set.

For the “rationale + distillation” baseline, a teacher–student two-stage configuration is adopted. The teacher is an open-source autoregressive large model used only to generate alignment/non-alignment rationales and soft labels offline, and does not participate in online inference. The student is a long-context encoder with a lightweight classification head, trained only on the calibration set and high-confidence pseudo-labels under small-sample conditions, using a weighted sum of hard-label cross-entropy and soft-label KL divergence [

55] as the loss function. The weights of the two losses, learning rate, training steps, and early-stopping criteria are all chosen by small grid search on the validation set, aiming to maximize F1 and Hit@k without sacrificing the Brier score or ECE. The distilled student runs independently at test time and uses the same temperature scaling and thresholds without invoking teacher inference.

To ensure fair comparison, the above settings follow two principles: (1) any decision-related hyperparameters are chosen only on the validation set, with no temporary adjustments on the test set; (2) method-specific engineering optimizations are restricted within feasible bounds to avoid incomparability due to different candidate pool sizes, different text truncation strategies, or different external resources. All random seeds and environment versions are fixed and recorded in the reproduction checklist provided in the appendix.

4.4. Evaluation Metrics

This study adopts the following evaluation suite: Hit@k, ROC-AUC, Precision, Recall, F1, the Brier score, and Expected Calibration Error (ECE). Ranking quality is assessed with Hit@k (Top-k hit rate) and ROC-AUC. Hit@k evaluates whether the ground-truth target appears within the top-k positions of the candidate list; common choices of k are 1, 5, and 10, which respectively reflect the model’s best-match capability and the extent of candidate coverage useful during human review. ROC-AUC measures the robustness of the overall ranking, with higher values indicating stronger discrimination between positive and negative instances. The Brier score computes the mean squared error between predicted probabilities and the true labels, where lower values indicate more accurate probability estimates; ECE assesses calibration by comparing predicted probabilities with empirical accuracies across confidence bins. These two metrics provide important guidance for setting decision thresholds between automated processing and human review in practical deployments.

5. Experimental Results and Analysis

This section reports and analyzes the main-task alignment results under a few-shot, two-stage setting. To maintain evaluation consistency, all methods adopt the same data split, candidate-set generation pipeline, and input truncation strategy. Decision thresholds and probability-calibration parameters are fitted on the validation set and then fixed for the test set.

5.1. Overall Performance Analysis

Table 1 summarizes the performance of each method on ranking metrics (Hit@1, Hit@5), classification metrics (Precision, Recall, F1), and probability metrics (ROC-AUC, Brier, ECE).

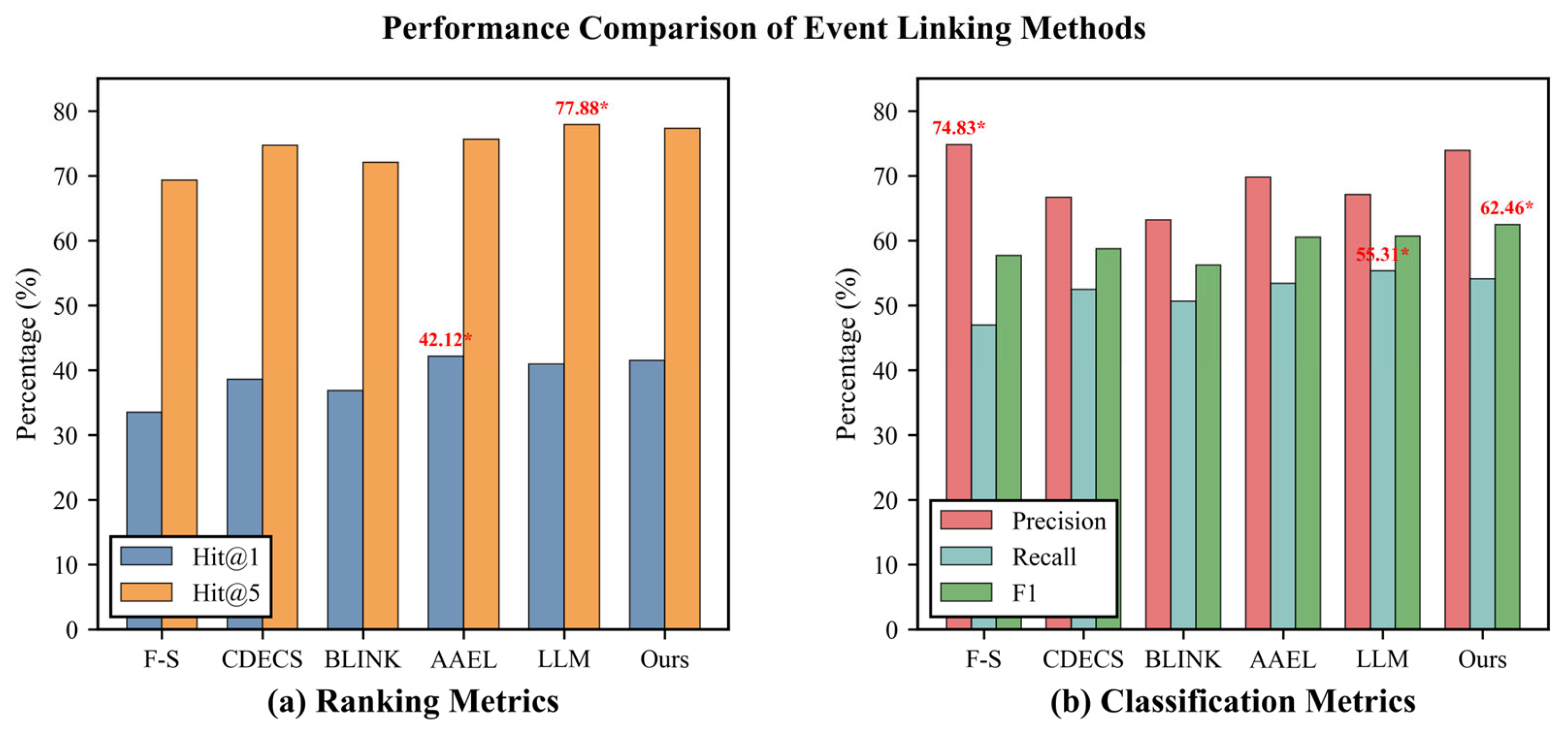

From the overall comparison, the proposed method performs well on several key metrics, showing competitive results particularly on Hit@1, F1, ROC-AUC, and the calibration metrics (Brier and ECE) .

In terms of ranking, AAEL achieves the best Hit@1 (42.12%), as showed in the

Figure 1 (a), followed by our method at 41.51% (a gap of 0.61%). The remaining methods rank as LLM (40.93%), CDECS (38.58%), BLINK (36.84%), and F-S (33.49%). For Hit@5, LLM leads with 77.88%, while our method attains 77.33% (a gap of 0.55%); AAEL (75.63%), CDECS (74.71%), BLINK (72.08%), and F-S (69.31%) follow. Hit@1 and Hit@5 assess how well a model ranks positives at the top, but it is worth noting that small differences in ranking metrics do not fully translate into improved reliability for automatic labeling.

Regarding classification metrics, our method attains the highest F1 score (62.46%), exceeding the next-best LLM (60.65%) by 1.81%. Further analysis shows our Precision is 73.92%, second only to F-S (74.83%); our Recall is 54.07%, 1.24% lower than the best LLM (55.31%). These results indicate that, under a unified threshold, our approach strikes a favorable balance between Precision and Recall, whereas other models present pronounced trade-offs: F-S yields high Precision but low Recall, while LLM achieves higher Recall with moderate Precision. As a target operating-point summary, F1 more comprehensively reflects the performance of an automatic labeling system, and the Precision–Recall differences provide practical guidance for human review.

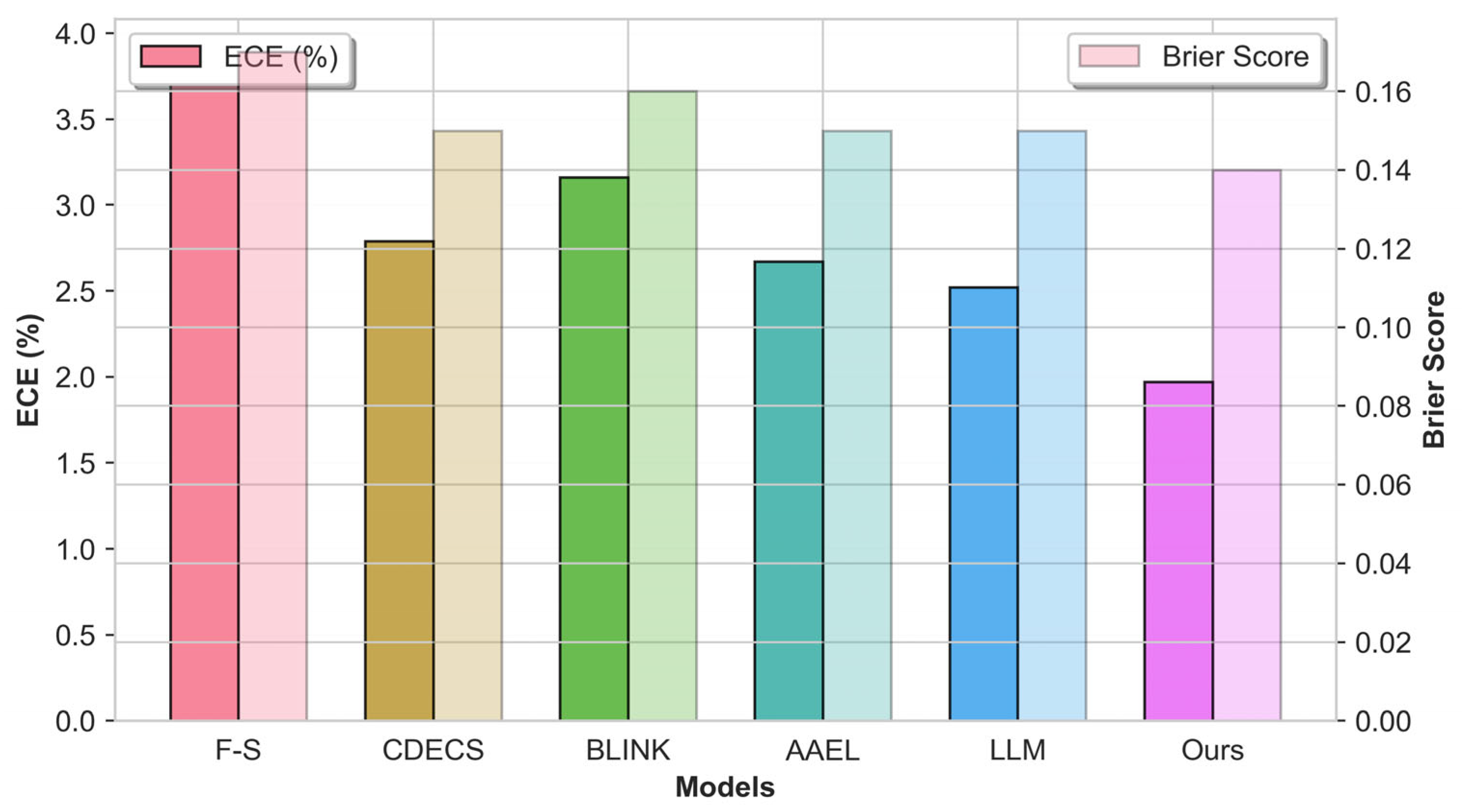

Figure 2.

Comparison of calibration metrics.

Figure 2.

Comparison of calibration metrics.

In probability calibration, our method achieves the lowest ECE (1.97%) and Brier score (0.14) among all methods. The Brier score measures the mean squared error of probabilistic predictions, where smaller values indicate predictions closer to the true distribution. ECE reflects calibration error; smaller values indicate more reliable confidence. Good calibration facilitates direct conversion from predicted probabilities to expected accuracy, thereby supporting threshold selection between automatic labeling and human review. For probability-based discrimination, ROC-AUC evaluates overall separability across thresholds; CDECS performs best (87.56%), closely followed by our method (87.34%), with a gap of 0.22%.

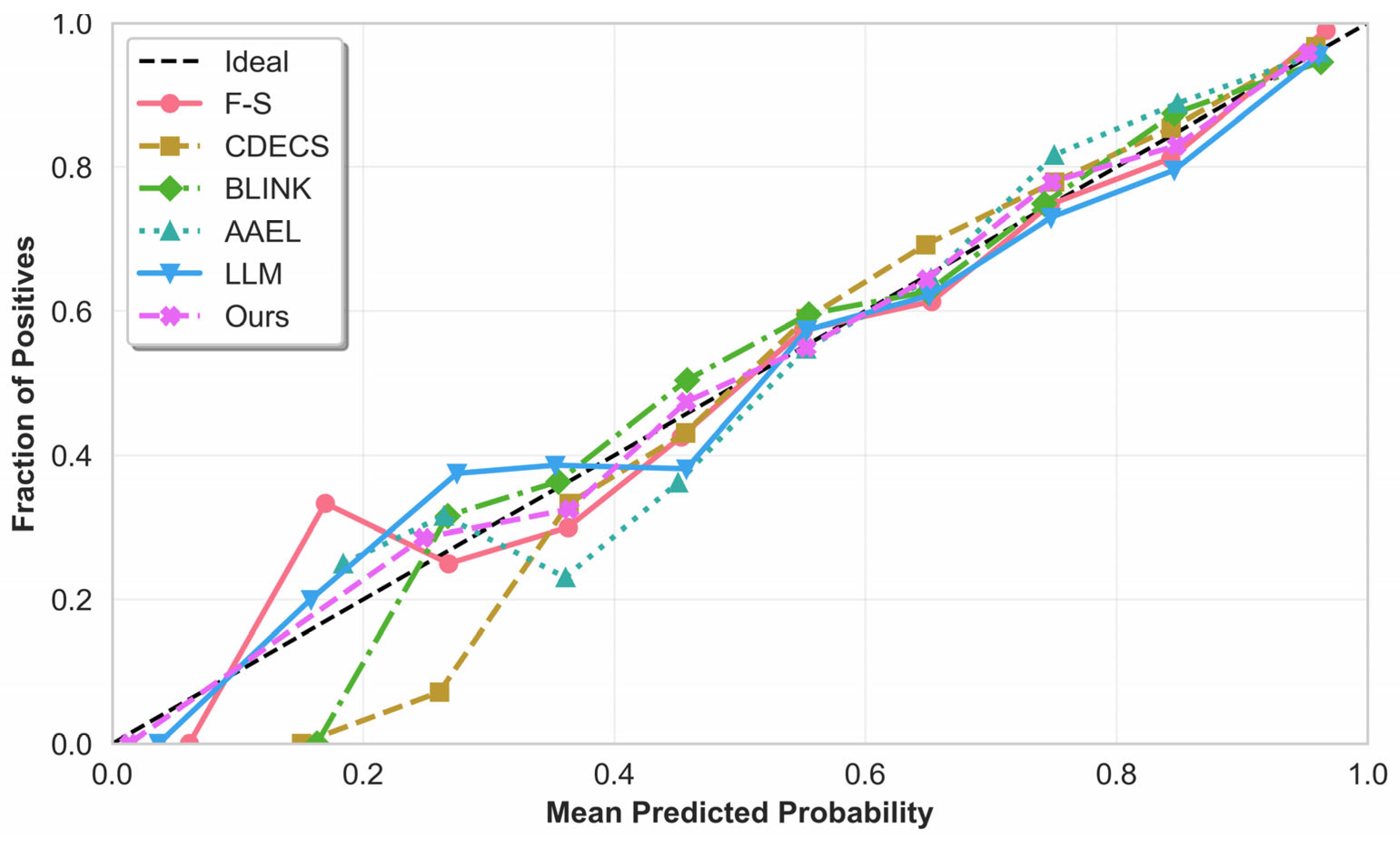

Figure 3 depicts the probability calibration of each model. The x-axis denotes the mean predicted probability within a bin, and the y-axis the empirical positive rate. The ideal calibration curve (black dashed line) corresponds to perfect probability estimates. Results show clear differences across models: our method’s curve lies closest to the diagonal, indicating high agreement between predicted and true probabilities; traditional methods (e.g., F-S) fall clearly below the diagonal, revealing systematic overestimation; some models (e.g., CDECS, BLINK) underestimate in low-probability bins but overestimate in high-probability bins.

5.2. Stability Analysis Across Different Sources

To further evaluate the robustness of each model in practical settings, this subsection examines the impact of text source on model performance. We partition the test set into three categories by source: government portals (e.g., National Energy Administration, State Grid, local emergency management authorities), professional institutions (e.g., Polaris Power, Xuexi Qiang’an integrated media platform), and public media (e.g., NetEase News, Chudian News). We report Hit@1 and F1 for each source, as shown in

Table 2.

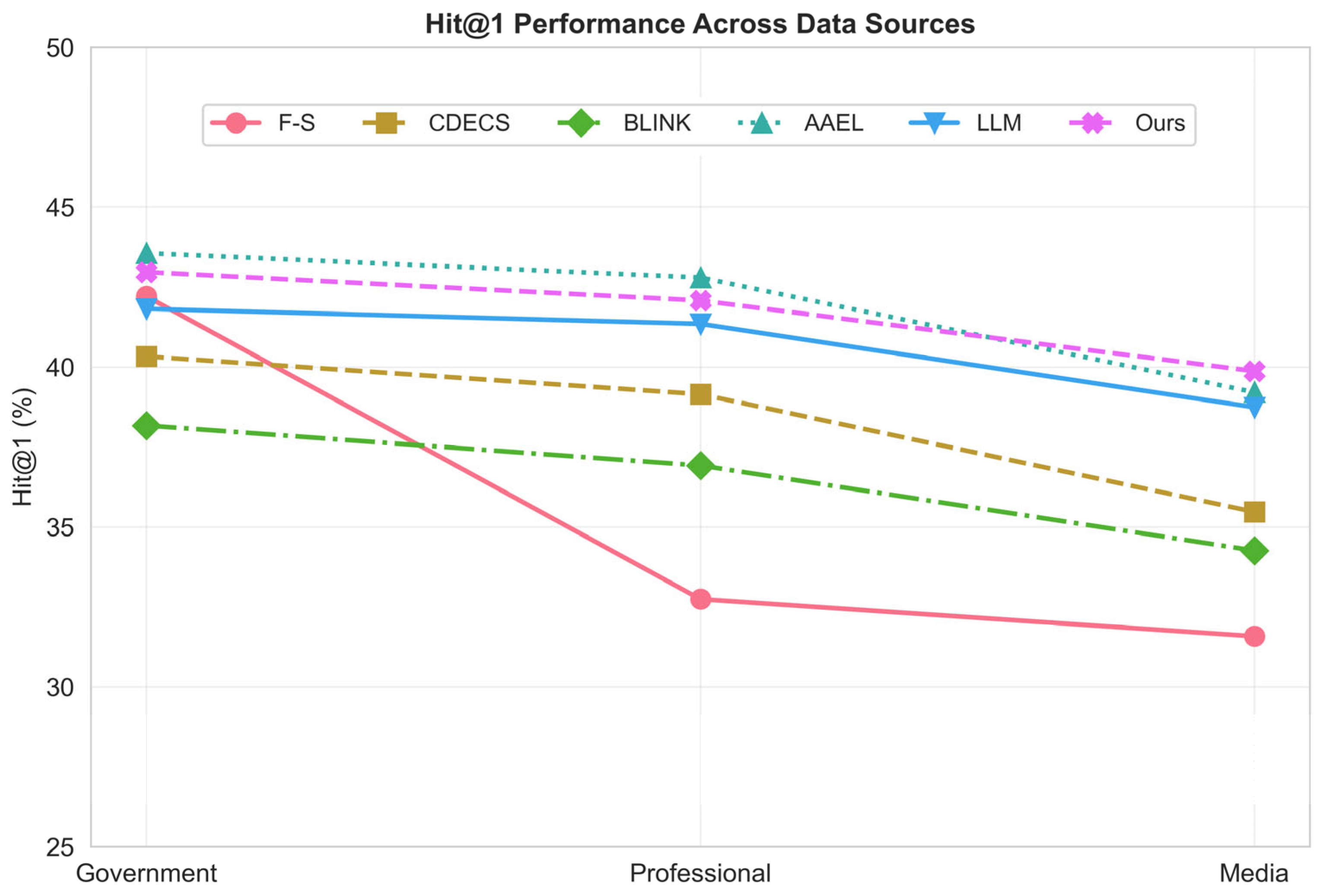

In the cross-source comparison , the Hit@1 curves exhibit pronounced layering and fluctuations. Specifically, all models perform best on government texts, followed by professional-institution texts, and drop to the lowest on public-media texts. The curves of AAEL and our method (Ours) remain in the top tier with relatively smooth trajectories, indicating stronger cross-domain stability; in contrast, F-S shows the largest fluctuations, with a marked decline on media data, suggesting weaker adaptability to non-standardized texts.

Figure 4.

Hit@1 across different source types.

Figure 4.

Hit@1 across different source types.

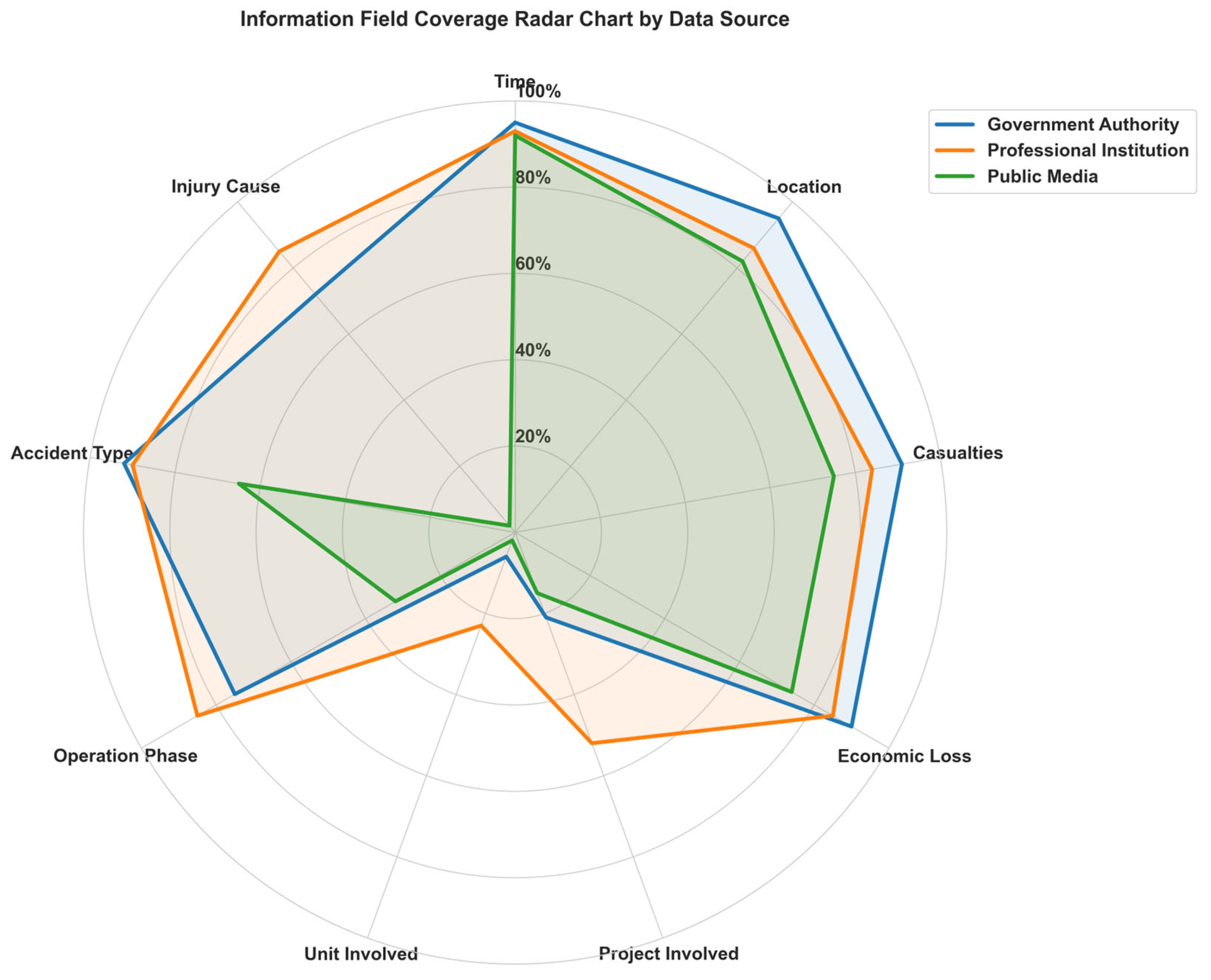

To better understand source-specific differences in information structure, we randomly sampled 100 accident reports from each source and computed the completeness of extracted accident information. We focused on coverage across nine key fields: time of occurrence, location, casualties, economic loss, involved project, involved organization, operational stage, accident type, and injury-causing agent. The statistics are shown below.

Figure 5 (geometric view) intuitively shows the differentiated coverage patterns. Government sources are most balanced, with broad arcs on basic fields (time, location, casualties) but no disclosure for involved organization, involved project, and injury-causing agent, consistent with standardized reporting requirements. Such structurally regular texts—with fixed information positions—benefit rule-based or traditional feature-matching models (e.g., F-S), which can achieve higher accuracy on basic fields.

By contrast, professional-institution texts exhibit prominent sectors on operational stage, accident type, and injury-causing agent, highlighting a focus on technical analysis. Terminology-dense, detail-rich documents favor models with semantic understanding (e.g., CDECS, LLM), which capture technical attributes and therefore perform well on cause- and agent-related fields. Traditional keyword models tend to degrade under such semantic complexity.

Public-media texts cover basic information like time and location reasonably well, but the sectors for involved organization and injury-causing agent narrow significantly, reflecting timeliness and selectivity in news reporting. Their looser structure, redundant details, and narrative style pose challenges to all models. Even so, the high coverage of basic fields provides surface-matching opportunities, enabling models with stronger semantic generalization (e.g., Ours) to maintain relatively stable overall performance.

In sum, accident texts from different sources exhibit systematic structural differences that markedly affect model performance. Government texts are standardized and field-complete, favoring traditional matching models but limiting deep reasoning due to avoidance of sensitive details. Professional-institution texts are terminology-dense with rich technical detail, better suited to semantically capable models for deeper analysis and linking. Public-media texts are loosely structured and information-redundant, challenging for all models, yet their high coverage of basic fields still benefits models with robust generalization. The findings indicate that models relying on surface feature matching generalize poorly across sources, whereas models incorporating semantic understanding and domain adaptation better accommodate structural differences and thus maintain more stable cross-source performance. These insights underscore that text-structural characteristics are key to cross-domain performance and inform model design for multi-source accident texts: enhancing semantic generalization and domain adaptation improves robustness in real-world applications.

5.3. Stability Analysis Under Different Decision Thresholds

In practical deployments of event linking, the choice of decision threshold directly affects both predictive outcomes and utility. To comprehensively assess each model’s stability across thresholds, we examine how the F1 score and the precision–recall balance vary under different operating points, with the aim of verifying whether our calibration advantage yields more reliable outputs across settings.

To ensure comparability, we use a unified test set and fixed model parameters, and evaluate three decision thresholds—0.3, 0.5, and 0.7—computing F1, Precision, and Recall for each model at each threshold while keeping all other experimental conditions unchanged. Table 6 reports the F1 scores and the fluctuation range across thresholds.

From

Table 3, our method maintains consistently high F1 across thresholds and exhibits the smallest fluctuation (only 1.7%), indicating the best threshold robustness. Concretely, at the more lenient threshold (0.3), all models show higher recall but lower precision; our method sustains relatively strong precision while keeping recall high. At the more stringent threshold (0.7), precision generally rises while recall falls; our method experiences the smallest recall drop, preserving a favorable balance.

5.4. Automatic Labeling Efficacy Analysis

We evaluate automatic labeling efficacy from an active-learning perspective. The analysis is based on the “maximum probability + probability gap” fusion strategy, which identifies high-uncertainty cases and precisely delineates the boundary between auto-labeling and human review. Metrics include: the proportion of auto-labeled items, the proportion sent to human review, the accuracy of high-confidence auto labels, and the proportion of true positives within the human-review set. The execution results are shown in

Table 4.

The results indicate that our method delivers the best automatic labeling efficacy. The auto-label proportion reaches 77.7%, while the human-review proportion drops to 22.3%. The accuracy of high-confidence auto labels is 97.5%, indicating highly reliable automated outputs; within the human-review set, the true-positive rate is 81.4%, confirming that the strategy effectively routes difficult, high-value cases for manual inspection. Compared with the F-S baseline (auto-label 58.8%, human-review 41.2%), our approach reduces the human-review share by 18.9 percentage points, cutting manual workload by nearly half. Competing models (CDECS, BLINK, AAEL, LLM) achieve auto-label shares between 62.6% and 71.4%, all below our method. This advantage mainly stems from superior probability calibration, which provides accurate uncertainty estimates and enables efficient, principled boundary setting between automated processing and human review—thereby improving both throughput and quality while avoiding rework from erroneous labels.

6. Results

The proposed method delivers consistently strong results across ranking, classification, and probability-based metrics. On the test set, it attains Hit@1 of 41.51% and Hit@5 of 77.33%, while achieving the best F1 of 62.46% with Precision 73.92% and Recall 54.07%. Probability-based discrimination is also competitive (ROC-AUC 87.34%). Most importantly for deployment, the model exhibits the most reliable probability estimates among all systems evaluated, with the lowest Brier score (0.14) and the lowest ECE (1.97%). These findings indicate that small differences in Hit@k do not fully capture downstream reliability, whereas improvements in F1 and calibration translate into more trustworthy confidence scores for operational decisions.

Stratified analyses show stable performance across heterogeneous sources, including government portals, professional institutions, and public media, with the expected ordering—best on government texts and worst on public-media texts—holding across all methods. Our approach remains in the top tier for each source and shows reduced variability relative to feature-matching baselines. This robustness is attributable to the combination of structured spatiotemporal constraints with semantic modeling, which mitigates stylistic and structural shifts in real-world accident reports.

Threshold-sensitivity experiments further corroborate the method’s stability. Sweeping the decision threshold over 0.3, 0.5, and 0.7, the model sustains the highest F1 at each operating point and exhibits the smallest fluctuation range (Δ = 1.7%) among all systems. This reduced sensitivity reflects superior probability calibration and the use of constrained monotonic fusion, simplifying deployment scenarios where operating points may change with workload or policy.

Finally, the automatic labeling study demonstrates clear practical gains. Using a decision rule that combines maximum probability with a probability-gap criterion, the system automatically labels 77.7% of cases with 97.5% accuracy among high-confidence outputs, while routing 22.3% to human review; within the review subset, the true-positive rate reaches 81.4%. Relative to a strong feature-matching baseline, this reduces the human-review share by 18.9 percentage points, increasing throughput without sacrificing quality.

Overall, the results show that integrating spatiotemporal lattice constraints with monotonic probability fusion and explicit calibration yields a model that is not only accurate but also operationally reliable. The approach provides calibrated confidence suitable for principled thresholding, maintains robustness across sources and operating points, and enables scalable, auditable automatic labeling in real-world accident-corpus construction.

7. Discussion

Our results support the working hypothesis that explicitly modeling spatiotemporal containment and calibrating probabilities end-to-end yields not only competitive accuracy but also operational reliability for cross-document accident linking. Concretely, the method matches strong baselines on ranking and discrimination while delivering the lowest Brier and lowest ECE, and it sustains the highest F1 across decision thresholds with the smallest performance fluctuation. These properties translate into practical gains for corpus construction: an auto-label share of 77.7% with 97.5% accuracy on high-confidence outputs, and a focused human-review queue whose positives are enriched by the probability-gap criterion. Together, the findings indicate that modest differences on Hit@k are less decisive for deployment than well-calibrated probabilities and stable operating behavior.

Viewed against prior lines of research, the approach complements both rule/template and graph-based methods—known for interpretability and global consistency but sensitive to similarity heuristics—as well as neural and PLM/LLM paradigms that excel at semantic alignment but can struggle when anchors are obscured by anonymization. By encoding administrative hierarchies and temporal granularity as a lattice with monotonic fusion, the method injects domain knowledge that constrains plausible matches, thus mitigating lexical variability and granularity mismatch that frequently degrade open-domain systems when transferred to safety texts. This design helps reconcile two desiderata often seen as competing in earlier work: (i) interpretable, auditable decision factors and (ii) transferable semantic representations robust to style and source shifts.

The stratified analyses across government portals, professional institutions, and public media situate the results in a broader context of source-dependent structure. Government reports are standardized and field-complete, favoring all systems but especially those relying on surface features; professional-institution texts are terminology-dense and analytically rich, rewarding models with stronger semantic understanding; public-media reports are loosely structured and selective, challenging every method. The proposed system’s cross-source stability is best explained by its dual reliance on (a) structured constraints, which regularize inference when key fields are present, and (b) calibrated probabilities, which reduce overconfidence when fields are missing or conflicting—thereby preserving throughput without inflating false positives.

Threshold-sensitivity experiments illuminate how calibration informs governance in human-in-the-loop pipelines. The two-tier rule-requiring both a minimum probability and a probability gap-operationalizes a conservative policy: obvious cases are automated; ambiguous, cluster-adjacent items are triaged for review. Unlike systems that implicitly treat similarity as probability, the present framework explicitly calibrates outputs, enabling principled choices of operating points tied to desired review budgets or service-level constraints. This aligns with deployment needs in critical domains, where auditability (metadata logging, gap margins, conflict penalties) matters as much as mean accuracy.

At the same time, the study reveals limitations that motivate further work. First, upstream extraction errors (e.g., time normalization, location resolution, argument parsing) propagate into fusion scores; while metadata logging and spot checks mitigate this, extraction quality remains a bottleneck. Second, small-sample calibration with monotonic projection may underrepresent rare factor combinations; when the calibration set lacks coverage, probability estimates can be conservative or biased in the tails. Third, the fixed conflict-penalty may over-suppress true positives in edge cases where administrative boundaries and reporting practices diverge (e.g., cross-jurisdiction incidents), suggesting a need for context-aware penalty schedules.

These observations point to several future directions. (1) Joint extraction–linking with uncertainty propagation (e.g., marginalizing over NER/normalization hypotheses) could reduce error cascades. (2) Adaptive calibration—such as hierarchical temperature scaling or Bayesian calibration—may better handle long-tail regimes and data drift. (3) Open-set detection and near-duplicate clustering could curb false links in bursty incident streams. (4) Multilingual and cross-regional extensions would test the lattice under diverse administrative ontologies and reporting norms. (5) Human-in-the-loop interfaces that expose calibrated probabilities, gap margins, and factor-wise contributions could improve reviewer efficiency and trust. (6) Finally, releasing auditable benchmarks with structured–unstructured pairs and calibration targets would facilitate apples-to-apples comparisons and accelerate progress on reliable event linking in safety-critical domains.

In sum, by fusing structured constraints with calibrated probabilistic inference, the proposed system advances beyond accuracy alone toward deployable reliability—maintaining performance across sources and thresholds, reducing manual burden, and providing transparent signals for governance and audit. These characteristics are broadly aligned with prior insights yet offer a clearer implementation pathway for probability consistency and operational feasibility in large-scale, real-world accident-corpus construction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, W.Z. and W.T.; data processing and experimental analysis, W.Z. and Y.Z.; validation, B.Z. and W.T.; investigation, B.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, W.Z.; writing—review and editing, W.Z. and Y.Z.; visualization, W.Z. and Y.Z.; supervision and project administration, W.T. and D.Y.; funding acquisition, W.T. and D.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [Shenzhen Science and Technology Program], grant number [KCXFZ20230731093902005].

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study can be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback and helpful suggestions, which have greatly improved the quality of this manuscript. Special thanks to the City Safety Risk Monitoring and Early Warning Emergency Management Key Laboratory at the Shenzhen City Public Safety Technology Research Institute for their technical support and for providing the necessary resources to conduct this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest..

References

- Nothman J, Honnibal M, Hachey B, et al. Event linking: Grounding event reference in a news archive[C]//Proceedings of the 50th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers). 2012: 228-232.

- Humphreys K, Gaizauskas R, Azzam S. Event coreference for information extraction[C]//Operational Factors in Practical, Robust Anaphora Resolution for Unrestricted Texts. 1997.

- Ahn D. The stages of event extraction[C]//Proceedings of the Workshop on Annotating and Reasoning about Time and Events. 2006: 1-8.

- Raghunathan K, Lee H, Rangarajan S, Chambers N, Surdeanu M, Jurafsky D, Manning C D. A multi-pass sieve for coreference resolution[C]//NAACL-HLT 2010. 2010: 492-501.

- Lu J, Ng V. Event coreference resolution with multi-pass sieves[C]//LREC 2016. 2016: 3996-4003.

- Cybulska A, Vossen P. Using a sledgehammer to crack a nut? Lexical diversity and event coreference resolution[C]//LREC 2014. 2014: 4545-4552.

- Cybulska A, Vossen P. “Bag of events” approach to event coreference resolution: supervised classification of event templates[J]. International Journal of Computational Linguistics & Applications, 2015, 6(1): 11-27.

- Cybulska A, Vossen P. Translating granularity of event slots into features for event coreference resolution[C]//Proc. of the 3rd Workshop on EVENTS. 2015: 1-10.

- Hovy E, Mitamura T, Verdejo F, et al. Events are not simple: Identity, non-identity, and quasi-identity[C]//Proc. of the First Workshop on EVENTS. 2013: 21-28.

- Araki J, Hovy E, Mitamura T. Evaluation for partial event coreference[C]//2nd Workshop on EVENTS. 2014: 68-76.

- Chen Z, Ji H. Graph-based event coreference resolution[C]//ACL-IJCNLP Workshop on Graph-based Methods for NLP. 2009: 54-57.

- Chen Z, Ji H, Haralick R. A pairwise event coreference model, feature impact and evaluation for event coreference resolution[C]//Workshop on Events in Emerging Text Types. 2009: 17-22.

- Lee H, Recasens M, Chang A, Surdeanu M, Jurafsky D. Joint entity and event coreference resolution across documents[C]//EMNLP-CoNLL 2012. 2012: 489-500.

- Choubey P K, Huang R. Event coreference resolution by iteratively unfolding inter-dependencies among events[C]//EMNLP 2017. 2017: 2124-2133.

- Yang B, Cardie C, Frazier P. A hierarchical distance-dependent Bayesian model for event coreference resolution[J]. TACL, 2015, 3: 517-528. [CrossRef]

- Kenyon-Dean K, Cheung J C K, Precup D. Resolving event coreference with supervised representation learning and clustering-oriented regularization[C]//*SEM 2018. 2018: 1-10.

- Peng H, Song Y, Roth D. Event detection and co-reference with minimal supervision[C]//EMNLP 2016. 2016: 392-402.

- Barhom S, Shwartz V, Eirew A, Bugert M, Reimers N, Dagan I. Revisiting joint modeling of cross-document entity and event coreference resolution[C]//ACL 2019. 2019: 4179-4189.

- Cremisini A, Finlayson M A. New insights into cross-document event coreference: Systematic comparison and a simplified approach[C]//EMNLP 2020 Workshop on Novel Evaluation Approaches for Text Generation. 2020: 7-16.

- Allaway E, Wang S, Ballesteros M. Sequential cross-document coreference resolution[C]//EMNLP 2021. 2021: 4659-4671.

- Han R, Peng T, Yang C, et al. Is information extraction solved by chatgpt? an analysis of performance, evaluation criteria, robustness and errors[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.14450, 2023: 48.

- Nath A, Manafi S, Chelle A, et al. Okay, Let's Do This! Modeling Event Coreference with Generated Rationales and Knowledge Distillation[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.03196, 2024.

- Wang X, Zhou W, Zu C, et al. Instructuie: Multi-task instruction tuning for unified information extraction[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.08085, 2023.

- Cybulska A, Vossen P. Guidelines for ECB+ annotation of events and their coreference[J]. Technical Report, 2014.

- Ellis J, Getman J, Fore D, et al. Overview of Linguistic Resources for the TAC KBP 2015 Evaluations: Methodologies and Results[C]//Tac. 2015.

- Chen B, Su J, Pan S J, Tan C L. A unified event coreference resolution by integrating multiple resolvers[C]//IJCNLP 2011. 2011: 102-110.

- Lu J, Venugopal D, Gogate V, Ng V. Joint inference for event coreference resolution[C]//COLING 2016. 2016: 3264-3275.

- Lu J, Ng V. Joint learning for event coreference resolution[C]//ACL 2017. 2017: 90-101.

- Bejan C A, Harabagiu S. Unsupervised event coreference resolution with rich linguistic features[C]//Proc. of ACL 2010. 2010: 1412-1422.

- Bejan C A, Harabagiu S. Unsupervised event coreference resolution[J]. Computational Linguistics, 2014, 40(2): 311-347.

- Araki J, Mitamura T. Joint event trigger identification and event coreference resolution with structured perceptron[C]//EMNLP 2015. 2015: 2074-2080.

- Araki J, Hovy E, Mitamura T. Evaluation for partial event coreference[C]//2nd Workshop on EVENTS. 2014: 68-76.

- Upadhyay S, Gupta N, Christodoulopoulos C, Roth D. Revisiting the evaluation for cross-document event coreference[C]//COLING 2016. 2016: 1949-1960.

- Joshi M, Levy O, Weld D S, Zettlemoyer L. BERT for coreference resolution: Baselines and analysis[C]//EMNLP-IJCNLP 2019. 2019: 5803-5808.

- Joshi M, Chen D, Liu Y, Weld D S, Zettlemoyer L, Levy O. SpanBERT: Improving pre-training by representing and predicting spans[J]. TACL, 2020, 8: 64-77. [CrossRef]

- Cattan A, Eirew A, Stanovsky G, Joshi M, Dagan I. Streamlining cross-document coreference resolution: Evaluation and modeling[OL]. arXiv:2009.11032, 2020.

- Yu X, Yin W, Roth D. Paired representation learning for event and entity coreference[OL]. arXiv:2010.12808, 2020.

- Zeng Y, Jin X, Guan S, Guo J, Cheng X. Event coreference resolution with their paraphrases and argument-aware embeddings[C]//COLING 2020. 2020: 1737-1747.

- Caciularu A, Ravfogel S, Bansal R, et al. CDLM: Cross-Document Language Modeling[OL]. Findings of ACL 2021 / arXiv:2101.00406, 2021.

- Beltagy I, Peters M E, Cohan A. Longformer: The long-document transformer[OL]. arXiv:2004.05150, 2020.

- Ma Y, Cao Y, Hong Y C, et al. Large language model is not a good few-shot information extractor, but a good reranker for hard samples![J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08559, 2023.

- Li J, Jia Z, Zheng Z. Semi-automatic data enhancement for document-level relation extraction with distant supervision from large language models[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.07314, 2023.

- Ding B, Min Q, Ma S, et al. A Rationale-centric Counterfactual Data Augmentation Method for Cross-Document Event Coreference Resolution[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.01921, 2024.

- Min Q, Guo Q, Hu X, et al. Synergetic event understanding: A collaborative approach to cross-document event coreference resolution with large language models[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.02148, 2024.