Introduction

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) is a common urological disease among elderly men, with its incidence significantly increasing with age. Epidemiological studies show that the prevalence of BPH among men over 50 years old in China ranges from 50% to 75%, and over 80% in those over 70 years old [

1]. BPH patients typically exhibit lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) such as frequent urination, urgency, and progressively difficult urination. In severe cases, it can lead to urinary retention, kidney function impairment, and significantly reduced quality of life [

2]. Currently, transurethral plasma kinetic resection of the prostate (TUPKRP) has become the preferred treatment for severe BPH due to its advantages of minimal trauma, good hemostasis, and quick postoperative recovery [

3]. This technique achieves precise prostate tissue resection using plasma cutting systems, effectively reducing the high incidence of complications seen with traditional procedures like the resection syndrome. However, postoperative issues such as urinary tract infections, wound bleeding, bladder spasms, and pain remain, and elderly patients often have comorbidities, weaker compensatory abilities, and are prone to physical and psychological discomfort such as sleep disorders and anxiety, which can delay recovery [

4,

5].

The concept of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) has been an important development in the field of surgery in recent years. Its core objective is to optimize perioperative interventions through multidisciplinary collaboration, reduce surgical stress, and promote rapid recovery [

6]. Predictive nursing based on the ERAS concept emphasizes identifying potential postoperative complications through risk assessments and taking targeted preventive measures, transitioning from "passive management" to "active prevention." Comfort nursing, which is patient-centered, provides multidimensional interventions—psychological, physiological, and social—to relieve physical and emotional discomfort and improve the overall healthcare experience [

7,

8]. While a single nursing approach may improve patient outcomes to a certain extent, it is difficult to fully meet the dual demands of "rapid recovery" and "comfortable experience" in TUPKRP patients. For example, predictive nursing focuses on preventing complications but may overlook subjective comfort; whereas comfort nursing emphasizes patient experience but lacks a systematic strategy for complication prevention [

9].

In light of this, the present study aims to combine predictive nursing and comfort nursing under the guidance of ERAS to create a dual-track intervention for TUPKRP patients, which both reduces the risk of complications and improves the patient's physical and psychological state. The goal is to provide a higher-quality nursing plan for TUPKRP patients, as reported below.

Materials and Methods

Study Participants

A total of 120 patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) who underwent TUPKRP at Linyi County People's Hospital and Qilu Hospital, Shandong University, from April 2023 to March 2025, were selected for this study. The inclusion criteria were: ① meeting the diagnostic criteria for BPH in the "Chinese Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia," with prostate volume ≥30 mL as indicated by transrectal ultrasound; ② meeting the surgical indications for TUPKRP, with no contraindications to surgery; ③ age between 55 and 85 years; ④ being alert with basic communication skills and able to cooperate for scale assessments; ⑤ signed informed consent and willingness to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were: ① concurrent prostate cancer, bladder cancer, or other malignant urological tumors; ② history of prostate surgery or urethral stricture; ③ serious cardiovascular diseases (such as acute myocardial infarction, cerebral hemorrhage), liver or kidney failure, or coagulation dysfunction; ④ mental disorders (such as depression, schizophrenia) or cognitive impairments; ⑤ pre-existing urinary tract infections or urinary retention.

Patients were randomly assigned to either the control group (n=60) or the observation group (n=60) using a random number table. In the control group, the patients' ages ranged from 56 to 84 years, with an average age of (72.35±4.12) years. Their disease duration was 1 to 10 years, with an average duration of (4.76±0.83) years, and prostate volume ranged from 32 to 85 mL, with an average of (58.24±10.31) mL. The group included 23 patients with hypertension, 15 with diabetes, and 8 with coronary heart disease. In the observation group, patients' ages ranged from 55 to 85 years, with an average age of (72.18±4.25) years. Their disease duration was 1 to 11 years, with an average duration of (4.82±0.79) years, and prostate volume ranged from 30 to 88 mL, with an average of (59.17±10.25) mL. The group included 25 patients with hypertension, 14 with diabetes, and 7 with coronary heart disease. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, disease duration, prostate volume, and comorbidities (P>0.05), suggesting comparability. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee (Ethical approval number: 2022YL-035).

Nursing Methods

Control Group: Conventional Perioperative Nursing

Preoperative Nursing: One day before surgery, patients received education on the surgical procedure, anesthesia methods, and preoperative precautions (such as fasting and water restrictions). Routine preoperative tests were conducted (complete blood count, coagulation function, liver and kidney function, electrocardiogram, etc.). On the night before surgery, patients were given a soap-water enema and 30 minutes before surgery, intravenous antibiotics were administered for infection prevention.

Postoperative Nursing: The urinary meatus was disinfected twice daily, the drainage bag was changed, and the urinary catheter was kept patent. Bladder irrigation was done with normal saline at room temperature until the drainage fluid was clear. After 6 hours, patients were gradually transitioned from fasting to liquid diet and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were given as needed for pain management. Patients were instructed to perform bed rest for 24 hours postoperatively and gradually began to ambulate 48 hours postoperatively.

Observation Group: Predictive Nursing Combined with Comfort Nursing Guided by ERAS Principles

The core of ERAS principles was integrated with predictive and comfort nursing to create a "Prevention-Comfort-Rehabilitation" integrated nursing plan, with specific measures as follows:

Predictive Nursing Guided by ERAS Principles

Pain Predictive Nursing: Preoperative pain tolerance was assessed. Postoperative pain was mainly located in the lower abdomen and urethra, and acupoint patch therapy was applied from postoperative days 1 to 7. Pain medications were prepared, and if the patient’s NPRS score ≥4, timely initiation of pain relief medication was initiated to prevent pain-induced stress responses.

Urinary Tract Infection Predictive Nursing: 30 minutes before surgery, intravenous cephalosporin antibiotics (e.g., cefazolin) were administered. Postoperatively, the urethral meatus was disinfected twice daily with 0.5% povidone-iodine and the glans penis was covered with sterile gauze to clean secretions. Patients were encouraged to drink 2000-2500 mL of water daily to flush the urethra. Routine urine tests were conducted, and if leukocyte count was elevated, antibiotic therapy was adjusted.

Postoperative Bleeding Predictive Nursing: Patients were instructed to remain in bed for 6 hours postoperatively to avoid increased abdominal pressure during repositioning. High-fiber foods were included in the diet to prevent constipation, and probiotics were administered daily to regulate gut flora. If constipation occurred, an enema was given to avoid straining that could lead to bleeding. The drainage fluid was monitored closely, and if bright red fluid was noted, the urinary catheter was clamped and the physician notified for further management.

Bladder Spasm Predictive Nursing: Bladder irrigation was performed with isotonic saline (37-38°C) postoperatively to prevent bladder smooth muscle stimulation from cold fluids. The speed of irrigation was adjusted according to the color of the drainage fluid. Pelvic floor muscle training was guided to relieve bladder spasms. If spasms occurred, patients were instructed to apply warm compresses to the lower abdomen for 15-20 minutes.

Comfort Nursing

Psychological Comfort Nursing: Personalized psychological counseling was provided one day before surgery. The "Listening-Explanation-Encouragement" approach was used to address patients' concerns (e.g., worries about surgical outcomes or postoperative sexual function). The advantages of TUPKRP (such as minimal trauma and fast recovery) were explained in simple terms, and successful case studies from the hospital were shared. Postoperatively, patients were informed of the successful surgery, which helped alleviate anxiety.

Sleep Comfort Nursing: Preoperative sleep habits were assessed, and a personalized sleep plan was created postoperatively. One hour before bedtime, electronic devices were turned off to avoid strong light stimulation. For patients with severe sleep disturbances, sleep-inducing audio was played, and short-acting hypnotic medications were administered as needed under medical guidance.

Social Comfort Nursing: Family members were encouraged to accompany the patients daily postoperatively to provide emotional support. During nursing procedures, patient privacy was protected, and patient dignity was respected. A home rehabilitation plan was developed before discharge, which included instructions for family members to assist with pelvic floor muscle exercises and dietary management, thus reinforcing social support.

Observation Indicators

Complication Rate

The incidence of complications within 7 days postoperatively was recorded for both groups, including urinary tract infections (leukocyte count ≥200/mL on routine urine test), postoperative bleeding (progressive decline in hemoglobin ≥10 g/L), bladder spasms (intermittent pain above the pubis or leakage from the urinary catheter), and atelectasis pneumonia (lung inflammation on chest radiograph). The total complication rate was then calculated.

Recovery Indicators

The time of urinary catheter retention, bladder irrigation time, and hospital stay were recorded for both groups. On the 7th postoperative day, the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) was used to assess the improvement in lower urinary tract symptoms. This scale consists of seven dimensions (frequency, urgency, intermittent urination, difficulty urinating, weak urine stream, incomplete urination, and nocturia), each rated from 0 to 5, with a total score ranging from 0 to 35. A lower score indicates milder symptoms.

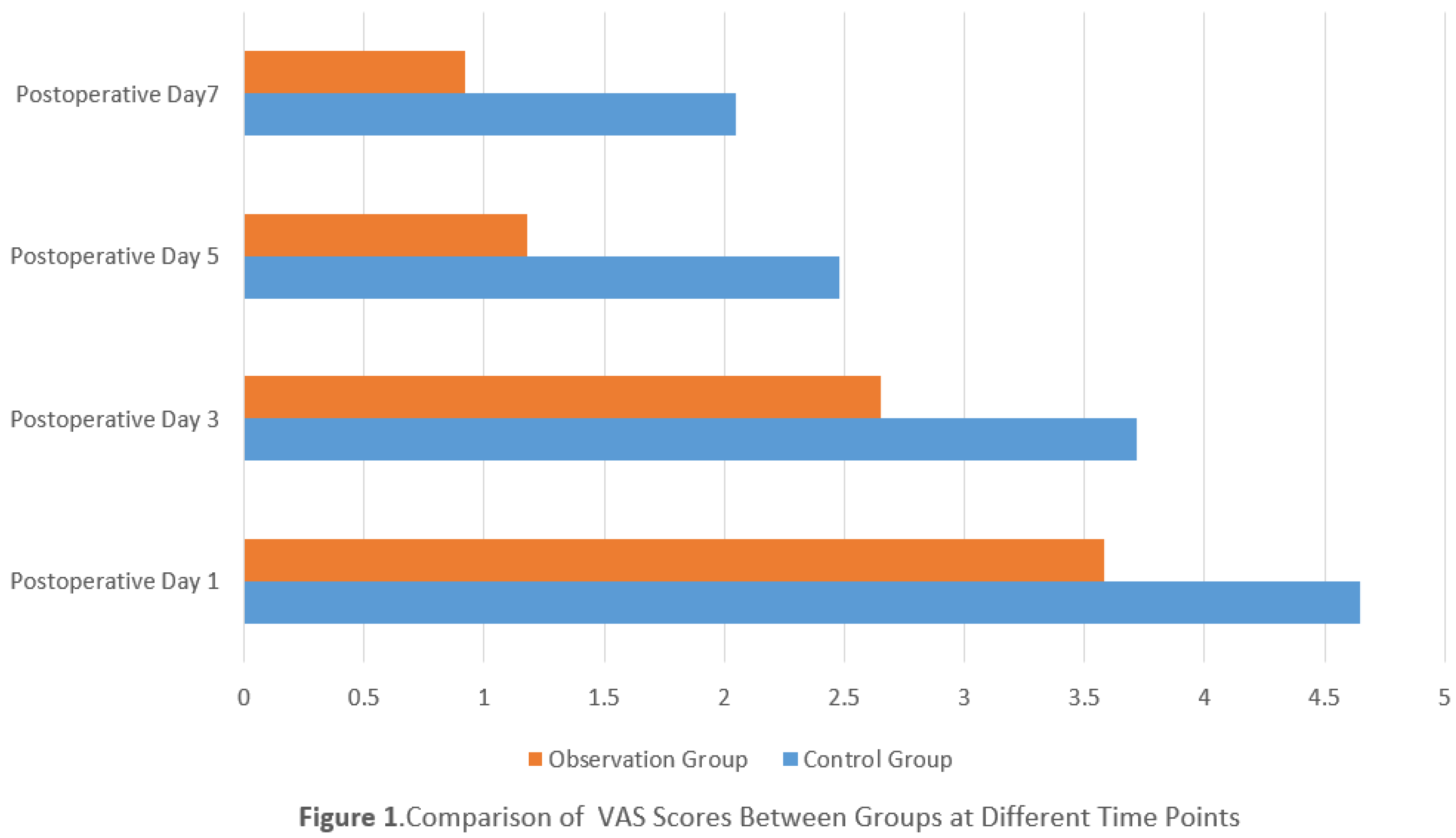

Pain VAS Scores

Pain severity was assessed using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) on postoperative days 1, 3, 5, and 7. The scale ranges from 0 (no pain) to 10 (severe pain), with higher scores indicating more severe pain.

Comfort Level Scores

Comfort levels were assessed using Kolcaba’s Comfort Questionnaire (GCQ) on postoperative days 24, 48, and 72 hours. The GCQ measures physiological comfort (8 items), psychological comfort (10 items), social comfort (6 items), and environmental comfort (4 items), totaling 28 items. Each item is rated from 1 to 4 points, with a total score ranging from 28 to 112. Higher scores indicate better comfort.

Sleep Quality Scores

Pre- and post-intervention sleep quality was assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) on the day before surgery and on the 7th postoperative day. The PSQI measures sleep quality, sleep onset time, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of hypnotics, and daytime dysfunction, with each dimension scored from 0 to 3, and the total score ranging from 0 to 21. Lower scores indicate better sleep quality.

Nursing Satisfaction

Nursing satisfaction was evaluated before discharge using a nursing satisfaction scale, which covers nursing attitude, nursing procedures, health education, and complication management. This scale includes 20 items, each rated from 1 to 5 points, with a total score ranging from 20 to 100. Total satisfaction was categorized as very satisfied (≥90 points), basically satisfied (70–89 points), or unsatisfied (<70 points). Total satisfaction rate = (number of very satisfied patients + number of basically satisfied patients) / total number of patients × 100%. The Cronbach's α coefficient of the scale was 0.87, indicating good reliability and validity.

Statistical Methods

Data analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0 statistical software. Continuous data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (x±s), and intergroup comparisons were performed using independent samples t-tests. Categorical data are presented as counts (percentages) [n (%)], and intergroup comparisons were made using the chi-squared (χ²) test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Comparison of Complication Rates Between Groups

The total complication rate in the observation group (5.00%) was significantly lower than in the control group (20.00%), with a statistically significant difference (P<0.05). There were no significant differences in the incidence of individual complications (urinary tract infection, postoperative bleeding, bladder spasms, or atelectasis pneumonia) between the two groups (P>0.05). The detailed data is shown in

Table 1.

Comparison of Recovery Indicators Between Groups

The observation group had significantly shorter urinary catheter retention time, bladder irrigation time, and hospital stay compared to the control group. Additionally, the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) in the observation group was lower than that in the control group, with statistically significant differences (P<0.05). The detailed data is shown in

Table 2.

Comparison of Pain VAS Scores at Different Time Points Postoperatively

The VAS scores for pain on postoperative days 1, 3, 5, and 7 were significantly lower in the observation group compared to the control group, with statistically significant differences (P<0.05). The detailed data is shown in

Figure 1.

Comparison of Comfort Level Scores at Different Time Points Postoperatively

The GCQ scores for comfort at postoperative days 24, 48, and 72 hours were significantly higher in the observation group compared to the control group, with statistically significant differences (P<0.05). The detailed data is shown in

Table 4.

Comparison of Sleep Quality Scores Pre- and Post-Intervention

Before the intervention, there were no significant differences in the PSQI scores between the two groups (P>0.05). After the intervention, the PSQI scores for all dimensions were lower in the observation group compared to the control group, with statistically significant differences (P<0.05). The detailed data is shown in

Table 5.

Comparison of Nursing Satisfaction Between Groups

The nursing satisfaction in the observation group (95.00%) was significantly higher than in the control group (80.00%), with a statistically significant difference (P<0.05). The detailed data is shown in

Table 6.

Discussion

The occurrence of postoperative complications in TUPKRP patients is associated with multiple factors, including surgical trauma, environmental stimuli, and the body’s stress response [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. In this study, the overall complication rate in the observation group was significantly lower than that in the control group. The core mechanisms contributing to this difference include:

①

Predictive Nursing Based on the ERAS "Prevention Priority" Concept: Predictive nursing uses a multidimensional risk assessment to identify high-risk factors for complications in advance and takes targeted preventive measures. For instance, the use of isotonic saline for bladder irrigation prevents cold-induced bladder smooth muscle stimulation, thus reducing the occurrence of bladder spasms. Preoperative and postoperative antibiotic prophylaxis, along with urethral meatus care, lowers the risk of urinary tract infections. The guidance to prevent constipation and avoid increased intra-abdominal pressure helps to reduce postoperative bleeding [

15].

②

Comfort Nursing to Improve Patient Tolerance: Comfort nursing helps to alleviate physical and emotional discomfort, which indirectly enhances the patient’s tolerance and overall recovery. For example, psychological counseling reduces anxiety, preventing sympathetic nervous system stimulation that can cause blood vessel constriction and increase bleeding risk. Sleep management improves sleep quality, which enhances immune function and reduces the risk of infections [

16]. The synergistic effect of these two approaches creates a "Prevention-Repair" dual protection strategy, effectively reducing the risk of complications.It is worth noting that there were no significant differences in the incidence of individual complications between the two groups. This may be attributed to the small sample size and short follow-up period (7 days post-surgery). Future studies with larger sample sizes and extended follow-up periods are needed to further verify the long-term impact of combined nursing on complications, such as urethral stricture.

Impact on Recovery Indicators

The observation group showed significantly shorter urinary catheter retention time, bladder irrigation time, and hospital stay compared to the control group, along with a lower IPSS score. This suggests that combined predictive and comfort nursing can accelerate patient recovery and improve lower urinary tract symptoms. This can be attributed to: ①

Optimized Postoperative Intervention: Predictive nursing, such as bladder irrigation with isotonic saline and pelvic floor muscle training, optimizes postoperative care, reduces bladder irritation, and shortens the duration of bladder irrigation. ②

Improved Patient Cooperation: Comfort nursing enhances patient cooperation, encouraging early ambulation and promoting the recovery of intestinal function, which in turn shortens the hospital stay [

17]. Furthermore, by preventing complications and avoiding recovery delays due to postoperative issues, combined nursing contributes to a faster recovery time.

Pain Management and Comfort Enhancement

Postoperative pain is a common discomfort in TUPKRP patients, which not only affects patient experience but may also induce stress responses that delay recovery [

20]. In this study, the VAS scores for pain were significantly lower in the observation group at all postoperative time points, and the GCQ scores for comfort were significantly higher. These results suggest that combined predictive and comfort nursing effectively alleviates pain and enhances comfort. Specifically: ① Pain Prevention with Predictive Nursing: Transcutaneous acupoint electrical stimulation was used for pain prevention, which helps regulate neurotransmitter release (such as increasing endorphins), thereby reducing pain [

21]. ②Comfort Nursing Interventions: Non-pharmacological interventions, such as music therapy and positional care, helped distract patients’ attention and alleviate pain perception. Environmental optimization and physiological comfort care reduced external stimuli, further improving patients' subjective comfort [

22]. Both strategies combined create a comprehensive approach to pain management and comfort enhancement, improving patients' postoperative experiences.

Sleep Quality Improvement

Sleep disturbances are common among TUPKRP patients after surgery, due to factors such as pain, anxiety, and environmental discomfort [

23]. In this study, the PSQI scores for sleep quality were significantly lower in the observation group after the intervention, indicating that combined predictive and comfort nursing effectively improved sleep quality. The mechanisms include:

Pain Relief: Reducing postoperative pain decreases nighttime awakenings and increases sleep duration.

Psychological Counseling: Alleviating anxiety helps patients fall asleep more easily.

Sleep Comfort Care: Interventions such as traditional Chinese foot baths and sleep-inducing audio combine physical and psychological approaches to improve sleep [

24].

Environmental Optimization: Controlling room temperature and reducing noise levels minimizes sleep disturbances. Good sleep quality promotes body repair, enhances immunity, and forms a positive feedback loop that accelerates recovery [

25].

Nursing Satisfaction

Nursing satisfaction is a critical indicator of nursing quality and is closely related to professionalism and humanistic care [

26]. In this study, the nursing satisfaction in the observation group (95.00%) was significantly higher than in the control group (80.00%), reflecting the benefits of the combined predictive and comfort nursing approach. The reasons include:

Patient-Centered Care: The integrated nursing model considers both "complication prevention" (professional care) and "subjective comfort" (humanistic care), meeting patients' diverse needs.

Personalized Nursing Measures: Personalized interventions, such as psychological counseling and customized sleep plans, make patients feel respected and improve their medical experience.

Improved Rehabilitation: The faster recovery and symptom relief observed in the observation group directly contributed to higher patient recognition of nursing care.

Conclusions

ERAS-guided predictive nursing combined with comfort nursing significantly reduces the postoperative complication rate in TUPKRP patients, shortens urinary catheter retention time, bladder irrigation time, and hospital stay, relieves postoperative pain, improves comfort and sleep quality, enhances lower urinary tract symptom relief, and increases nursing satisfaction. This integrated nursing model, which combines "prevention" and "comfort," aligns with modern surgical nursing trends and provides a high-quality perioperative nursing plan for TUPKRP patients. This model is worth clinical promotion and application.

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

- Xu, K.; Su, Q.; Xu, J.; et al. Comparative evaluation of palliative holmium laser enucleation and plasma kinetic prostate resection in the management of advanced prostate cancer with lower urinary tract symptoms. Lasers in medical science 2025, 40, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Luo, T. Transurethral Plasmakinetic Resection of the Prostate on Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Observation of Stress Injury and Analysis of Factors Associated with Postoperative Urinary Tract Infection. Archivos espanoles de urologia 2025, 78, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yuan, Z.; et al. Clinical Efficacy Study of Transurethral Thulium Laser Enucleation of the Prostate and Transurethral Bipolar Plasma Resection of the Prostate in the Treatment of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Archivos espanoles de urologia 2025, 78, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, C.; Zou, S.; Cui, S. The Impact of Plasmakinetic Resection and Conventional Transurethral Resection of the Prostate on Clinical Symptoms and Quality of Life in Patients with Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Retrospective Cohort Study. Urology journal 2025, 22, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Jia, L.; Li, W.; et al. Safety and efficacy of low-powered holmium laser enucleation of the prostate in comparison with plasma kinetic resection of prostate. Lasers in Medical Science 2024, 40, 2–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Xiao, M.; Xiong, T.; et al. Comparative analysis of the safety and efficacy of 1470-nm diode laser enucleation of the prostate and plasmakinetic resection of prostate in the treatment of large volume benign prostatic hyperplasia (>80 ml). The aging male : the official journal of the International Society for the Study of the Aging Male 2024, 27, 2257307–2257307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Qing, Z.; He, J.; et al. Efficacy of transurethral plasmakinetic resection of the prostate using a small-caliber resectoscope for benign prostatic hyperplasia with mild urethral stricture. Journal of Central South University. Medical sciences 2024, 49, 1751–1756. [Google Scholar]

- Coman, A.R.; Coman, T.R.; Popescu, I.R.; et al. Multimodal Approach Combining Thulium Laser Vaporization, Bipolar Transurethral Resection of the Prostate, and Bipolar Plasma Vaporization versus Bipolar Transurethral Resection of the Prostate: A Matched-Pair Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13, 4863–4863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, X.; et al. Effect of Oral Gabapentin before Plasmakinetic Resection of the Prostate on Anesthesia Effects in Older Adults with Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: A Retrospective Study. Archivos espanoles de urologia 2024, 77, 766–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.W.; Wang, J.W.; Song, Q.Z.; et al. [Thulium laser enucleation versus plasma kinetic resection of the prostate in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia]. National journal of andrology 2024, 30, 514–518. [Google Scholar]

- International, R.B. Retracted: Using Haemocoagulase Agkistrodon in Patients Undergoing Transurethral Plasmakinetic Resection of the Prostate: A Pilot, Real-World, and Propensity Score-Matched Study. BioMed research international 2024, 2024, 9825156–9825156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, W.; Hongyan, L.; Rongzhen, T.; et al. The Safety and Efficacy of Bipolar Plasma-Kinetic Transurethral Resection of The Prostate in Patients Taking Low-Dose Aspirin. Urology journal 2023.

- ChongYi, Y.; GeMing, C.; YueXiang, W.; et al. Clinical efficacy and complications of transurethral resection of the prostate versus plasmakinetic enucleation of the prostate. European journal of medical research 2023, 28, 83–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kun, P.; Qing, L.; Bo, C.; et al. [Transurethral plasma resection of the prostate for acute urinary retention in patients with advanced prostate cancer]. National journal of andrology 2023, 29, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Qiang, J.L.; Teng, W.M.; Wei, B.L.; et al. Clinical Study on the Application of Preserved Urethral Mucosa at the Prostatic Apex in Transurethral Plasmakinetic Resection of the Prostate. Frontiers in Surgery 2022, 9922479–922479. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, J.; Guang, E.Y.; Xin, Y.Z.; et al. Transurethral plasmakinetic resection versus enucleation for benign prostatic hyperplasia: comparison of intraoperative safety profiles based on endoscopic surgical monitoring system. BMC Urology 2022, 22, 65–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- XianTao, Z.; YingHui, J.; TongZu, L.; et al. Clinical practice guideline for transurethral plasmakinetic resection of prostate for benign prostatic hyperplasia (2021 Edition). Military Medical Research 2022, 9, 14–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Z.; Lan, Y.; Hao, Z.; et al. Using Haemocoagulase Agkistrodon in Patients Undergoing Transurethral Plasmakinetic Resection of the Prostate: A Pilot, Real-World, and Propensity Score-Matched Study. BioMed research international 2022, 2022, 9200854–9200854. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, K.; Ahmed, H.; Mohamed, E.; et al. Comparison between the coagulation depth of bipolar plasma vaporization of the prostate, bipolar resection of the prostate, and monopolar resection of the prostate. The Egyptian Journal of Surgery 2021 40, 1295–1299.

- Wen, D.; Luyao, C.; Xiaoqiang, L.; et al. Bipolar plasmakinetic transurethral enucleation and resection versus bipolar plasmakinetic transurethral resection for surgically treating large (≥60 g) prostates: a propensity score-matched analysis with a 3-year follow-up. Minerva urology and nephrology 2021, 73, 376–383. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Chuying, Q.; Peng, X.; et al. Comparison of bipolar plasmakinetic resection of prostate versus photoselective vaporization of prostate by a three year retrospective observational study. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 10142–10142. [Google Scholar]

- Castellani, D.; Rosa, D.M.; Pace, G.; et al. Comparison between thulium laser vapoenucleation and plasmakinetic resection of the prostate in men aged 75 years and older in a real-life setting: a propensity score analysis. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 2021, 33, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashim, E.A. The Coagulation Depth of Bipolar Plasma Vaporization of the Prostate vs Bipolar Resection of the Prostate vs Transurethral Resection of the Prostate. Medical & Surgical Urology 2021, 10, 1–1. [Google Scholar]

- Hugo, O.; Manuel, Á.; Roberto, M.; et al. A prospective randomized study comparing bipolar plasmakinetic transurethral resection of the prostate and monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate for the treatment of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: efficacy, sexual function, Quality of Life, and complications. International braz jurol: official journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology 2021, 47, 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Jian, Z.; Yonghui, W.; et al. Efficacy and Safety Evaluation of Transurethral Resection of the Prostate versus Plasmakinetic Enucleation of the Prostate in the Treatment of Massive Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Urologia internationalis 2021, 105, 735–742. [Google Scholar]

- Enmar, H.; Said, M.E.; et al. Holmium Laser Enucleation versus Bipolar Plasmakinetic Resection for Management of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Patients with Large Volume Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Randomised Controlled Trial. Journal of endourology 2020, 47, 131–144. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).