1. Introduction

Innovation is found to be the driver of productivity, income generation, and empowerment across Africa (Wolf, 2006; Adekunle et al., 2013; Dos Santos, 2024; United Nations 2024). However, research on Africa’s innovation landscape and its determinants, especially in the era digitalization, remains unclear due to the persistence focus on labor-intensive practices, outdated technologies, and culturally embedded risk aversion (Adekunle et al., 2013; Dos Santos 2024). Despite this narrow view, individuals, especially youth, have demonstrated notable external search breadth and depth as well as absorptive capacities i.e., cognitive abilities in implementing innovative solutions across different sectors in Africa (Reij & Waters-Bayer, 2014; Żmija et al., 2020; Arthur-Holme et al., 2023; Ayanwale et al., 2023; Das & Pal, 2023; Consentino et al., 2023). Beaudry et al. (2018) observe that substantial number of academic researchers on the continent obtain their doctoral degrees before the age of 40, meaning that research and development (R&D) activities are often youth-driven. The external search breadth and depth framework offers a useful lens for understanding these dynamics. This entails engagement with information source (breadth), focused interactions with select source (depth) are crucial for converting knowledge inflows through the cognitive abilities into innovation (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Laursen & Salter, 2006). Access to quality information and knowledge flows enhances youth capacity to translate external inputs into tangible innovation outcomes (Okwu & Daudu, 2011; Lugamara et al., 2019; Bentley et al., 2019). Thus, the accessibility and information channels become central determinants of youth-led innovation (Dutta, 2009; Adekunle et al., 2013; Igwe et al., 2020; Pretty et al., 2018; Benjamin et al., 2021, 2024). Expansions in internet accessibility and mobile connectivity have transformed Africa’s information landscape, introducing youth-preferred channels for knowledge transfer, particularly via social media (Van Mele et al., 2018; Alper & Miktus, 2019). Lohento & Ajilore (2015, p. 121) defined as “

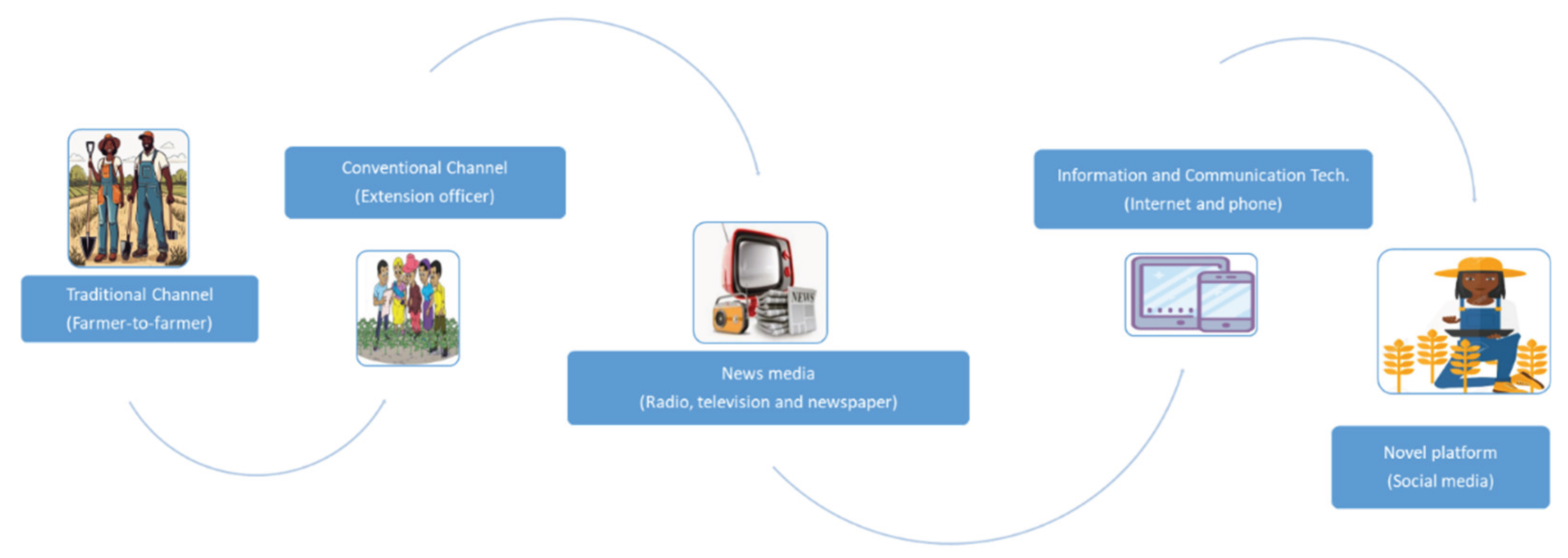

electronic information and communication platforms that enable users to easily create and disseminate content on digital networks and engage in interactive communications”. Social media platforms such as YouTube and Synergy portal enable youth to exchange practical knowledge, co-create solutions, and collaborate on problem-solving (Asio & Khorasani, 2015). The agricultural sector in Africa is a prime example of evolution of knowledge information among youths and how external search breadth and depth has changed (see

Figure 1 below). In the earliest stages, external information search and knowledge exchange was through peers-to-peer communication. This peer-to-peer method, while effective in many ways, had its limitations. As information was passed from person to person or word of mouth (WoM), the accuracy and credibility often diminished, leading to potential misinformation among those at the tail end of the communication chain (Kawakami and Parry 2013). Despite its shortcomings, this traditional method of information exchange continues to hold relevance today, as personal interactions and community-based knowledge sharing still play a crucial role in various sectors (Benjamin et al. 2016; Kawakami and Parry 2013). A major shift in information exchange during the Green Revolution, was the introduction of trained and skilled personnel i.e., extension officers showcasing innovations developed by experts (Benjamin et al. 2021, Raidimi and Kabiti 2017). This conventional method was further complemented by the expansion of media channels such as television, radio, and the printing press, i.e., electronic word-of-mouth (eWoM). These media outlets played a crucial role in amplifying the outreach of extension services. Instead of relying solely on face-to-face interactions or WOM communication, these officers could leverage television programs, radio broadcasts, and printed articles to reach a wider audience more efficiently. Today social media platforms such as youtube have become essential tools for digital communication and information sharing among youths (Alper and Miktus 2019; Ovhal 2025). As a result, social media has emerged as a powerful vector for eWoM, allowing Knowledge to spread not only within local communities but also across national and continental boundaries.

However, social media usage alone is insufficient to spur innovation among youth. Broader macroeconomic such as gross domestic product (GDP) per capita moderate the extent to which digital knowledge inflows yield tangible results (Adekunle et al., 2013; Igwe et al., 2020). Despite the growing research on social media and youth in Africa, empirical research examining its link to innovation remains scarce. Data limitations and fragmented studies have hindered comprehensive assessments of how this youth-preferred digital platforms affect national innovation trajectories.This study addresses these gaps by examining the relationship between social media usage and national innovation across 52 African countries from 2009 to 2022. Data were sourced from the World Bank Development Indicators (World Bank, 2024) and StatCounter Global Statistics (StatCounter, 2024). The study makes two key contributions. First, it provides the first continent-wide empirical assessment of the link between social media usage, a youth-driven knowledge exchange, and national innovation outcomes. Second, by integrating macroeconomic moderators, it underscores the critical role of enabling ecosystems in translating youth engagement into tangible innovation gains.

2. Material and Methods

The descriptive statistics (see Table 2) depicts a highly uneven developmental landscape across Africa, where innovation potential, digital engagement, human capital, and institutional capacity vary markedly between countries. While some economies exhibit relatively high levels of patenting, education investment, internet penetration, and institutional efficiency, many others remain constrained by low income, limited digital infrastructure, weak institutions, and vulnerability to external shocks. This heterogeneity is particularly consequential for youth-driven innovation. In countries with favorable conditions, social media platforms can amplify external knowledge flows, deepen engagement with tacit and explicit knowledge, and facilitate co-creation of solutions. In less developed contexts, however, low platform usage, limited digital access, and institutional barriers inhibit the capacity of youth to translate information into meaningful innovation outcomes. Countries with higher GDP per capita, greater internet penetration, and stronger institutional frameworks are better positioned to leverage social media for knowledge acquisition and dissemination. Conversely, countries with lower income, limited digital infrastructure, and burdensome regulatory environments face compounded challenges, where the promise of digital knowledge platforms is often unrealized.

The dataset spans 52 African countries over the period 2009–2022, this was also included as annual trends to capture year-specific effects using 2009 as the reference year. Overall, the data reveal that innovation activity remains relatively modest and unevenly distributed across Africa. Patent filings, one of the core proxies for innovation, average just 95 applications per year across the continent. However, the high standard deviation of 211 underscores substantial disparities, suggesting that innovation is heavily concentrated in a small subset of countries. This uneven distribution reflects structural differences in technological capacity, institutional effectiveness, human capital endowment, and historical investment in research and development. For instance, countries such as South Africa, Egypt, and Nigeria consistently account for the majority of patent applications, while a substantial number of lower-income countries report negligible patenting activity, highlighting persistent regional and developmental gaps. Social media usage, particularly on platforms such as YouTube, remains modest with a mean rate of 5.3% compared to Facebook of >80%. This relatively low penetration reflects the fragmented nature of the digital ecosystem across the continent. While some countries report rapidly expanding internet and smartphone access, others remain largely offline due to infrastructural, economic, and regulatory constraints. Control variables further illustrate the pronounced heterogeneity of African economies. GDP per capita averages USD 2,495, reflecting the continent’s overall low-income profile, but spans a wide range from below USD 200 in some low-income countries to nearly USD 19,142 in upper-middle-income economies. This disparity highlights stark differences in economic capacity, consumer purchasing power, and market size, all of which can influence both the resources available for innovation and the incentives for firms and individuals to engage in knowledge-intensive activities. Internet penetration, a key enabling factor for digital knowledge flows, averages 22.5% of the population but varies from virtually negligible access (0.3%) to near-saturation levels (89.9%). Such variation illustrates the digital divide within Africa, where youth in better-connected countries are better positioned to engage with knowledge-intensive platforms and co-create innovative solutions. Public investment in education, a critical determinant of human capital and absorptive capacity, also exhibits substantial variation. While the mean allocation to public education is 4% of GDP, some countries dedicate more than 10.8%, signaling considerable differences in state commitment to skill development. Higher investment in education typically correlates with greater capacity for innovation, as well-educated youth are more likely to interpret, adapt, and implement novel ideas. Conversely, countries with lower educational investment may experience systemic limitations in developing absorptive capacity, thereby constraining innovation outcomes even when digital platforms are available. Institutional indicators, such as the procedural burden of starting and registering a business, further highlight disparities across the continent. Similarly, value addition from the manufacturing sector to GDP was on average 3.4%, with some countries not in a position to support manufacturing -43.8%. The number of steps required to establish a formal enterprise ranges from three (3) to eighteen (18), reflecting significant differences in regulatory efficiency and the ease of entrepreneurial activity. A higher procedural burden can act as a disincentive to formal entrepreneurship and R&D engagement, particularly for youth-led start-ups that rely on digital platforms for market access and knowledge acquisition. Volatility in trade and industrial indicators underscores the exposure of African economies to external shocks, which further complicates innovation trajectories. Import growth rates, for instance, range from -94.7% to 328.7%, illustrating the pronounced instability in trade flows and the susceptibility of national economies to global market fluctuations. Such volatility can disrupt supply chains, reduce incentives for R&D investment, and exacerbate disparities in access to essential inputs for innovation, particularly in manufacturing-intensive sectors. Similarly, variations in industrial development across countries influence the absorptive capacity of youth, as sectors with higher technological intensity provide more opportunities for knowledge transfer and practical experimentation.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics.

| Variable |

Obs |

Mean |

Std. Dev. |

Min |

Max |

| Patent applications |

420 |

95 |

211 |

1 |

1804 |

| YouTube (%) |

686 |

3.7 |

5.5 |

.01 |

48.1 |

| Internet (% of population) |

686 |

22.5 |

20.7 |

0.3 |

89.9 |

| GDP per capita (current US$) |

686 |

2,495 |

3,146 |

199 |

19,142 |

| Value added manufacturing industry (% annual growth) |

644 |

3.4 |

8.2 |

-43.8 |

72.6 |

| Government expenditure on education (% GDP) |

644 |

4 |

1.9 |

.35 |

10.8 |

| Procedures to register start-ups (number) |

686 |

9 |

3. |

3 |

18 |

| Imports of goods and services (%) |

644 |

6.4 |

19.9 |

-94.7 |

328.7 |

A baseline econometric model (Wooldridge, 2016) assessing the impact of using social media platforms on innovation is specified as:

where,

(Y) Innovation

it is represented by innovation proxy (patent applications) for country

i in year

t. YouTube

it, represents the usage rates of social media platforms in country

i at time

t and their coefficients

β.

Xit is a vector of control variables (time-variant) that capture potential confounding effects and their coefficients γ. μ

i captures the unobserved country-specific effect (time-invariant). And

εit is the error term.

The model employed in this study is specified as a fixed effects (FE) estimator

1, based on the assumption that unobserved, country-specific, time-invariant characteristics (μᵢ) are correlated with the explanatory variables. The FE approach is chosen to control for these effects, as it effectively eliminates time-invariant heterogeneity at the country level, thus ensuring consistent and unbiased coefficient estimates (Wooldridge, 2016: 435–437). The model includes a time variable (τₜ) to capture time fixed effects. This addition controls for macro-level disturbances affecting all countries. A subsequent test confirmed the necessity of including time fixed effects, validating the presence of such unobserved temporal influences.

Robustness checks were conducted to tests for heteroskedasticity, autocorrelation, and cross-sectional dependence using the Wald-, Wooldridge-, and Pesaran CD test, respectively, an corrective measure employed were appropriate (Wooldridge, 2016: 395; Pesaran, 2021: 9–12; see Appendix for detailed results). The study interpret the coefficients in terms of association, rather despite than causation (see discussion section for more details).

Control Variables Acting as Confounders

The control variables account for potential confounding influences on the relationship between innovation and social media platform usage. These include economic, institutional, trade, industry, and education factors.

Table 2 provides a summary of these variables and their potential effects. Widely used in innovation and research analyses, these controls function as neutral covariates: they do not introduce systematic bias but can improve the precision of the estimated relationships. In cases where their influence is minimal, they are unlikely to affect the results substantially, ensuring that the primary focus remains on the effects of social media engagement on innovation outcomes.

3. Results

Table 3 presents the regression results examining the determinants of patent applications across 52 African countries. In three of the four estimated models (Models 1–3), YouTube usage, a preferred digital platform among youth, demonstrates a robust positive and statistically significant association with patent activity, with coefficients ranging from 0.004 to 0.005. These results indicate that a one-percentage-point increase in YouTube usage is associated with an increase of 0.004 to 0.005 in patent applications, highlighting the platform’s potential role in facilitating knowledge diffusion, skill acquisition, and the creative problem-solving capacities that underpin innovation. The consistency of these effects across multiple model specifications underscores the platform-specific nature of digital engagement in supporting youth-driven innovation. Conversely, internet penetration rates exhibit a consistently negative and statistically significant relationship with patenting across the same three models, with coefficients ranging from –0.003 to –0.004. This counterintuitive finding suggests that broader internet access alone may not directly translate into innovation outcomes. While internet access increases connectivity and information availability, it may also facilitate passive consumption of content rather than active knowledge creation and application, particularly in contexts where complementary capabilities such as absorptive capacity and digital skills, are modest. This underscore the importance of platform digital engagement over general internet availability in shaping innovation outcomes. Content-rich, and interactive channels like YouTube may be more effective for promoting patenting activity than merely expanding internet infrastructure. The results of this analysis further underscore the role of a country’s openness in facilitating the conversion of knowledge into tangible innovations. Specifically, greater trade openness is associated with higher patenting activity. Other macroeconomic and institutional variables, including GDP per capita and government expenditure on education, exhibit consistent positive but statistically insignificant effects on patenting. Similarly, procedure to register start-ups was consistent negative but statistically insignificant. This may be indicative of the link between wealth, public investment in human capital, bureaucracy and foundational context of innovation. The analysis also reveals pronounced year-specific effects, particularly from 2015 onward. Notably, the period between 2018 and 2022 exhibits consistently strong and statistically significant positive coefficients, indicating a marked increase in patent applications relative to the base year, 2009. This upward trend may reflect a combination of factors, including expanding youth engagement with digital platforms, increasing policy emphasis on innovation ecosystems, and broader continental trends in digitalization and R&D investment. The temporal patterns highlight that innovation in Africa is dynamic and responsive to structural changes in digital connectivity, institutional reforms, and global integration, underscoring the importance of considering both cross-sectional and longitudinal dimensions in understanding innovation trajectories.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that YouTube, beyond its entertainment origins, has become an important platform for knowledge sharing, creativity, and innovation among Africa’s educated youth. Consistent with earlier work (Asio & Khorasani, 2015; Jung & Lee, 2015; Semingson & Hall, 2019), the results show that YouTube engagement is positively and significantly associated with several indicators of innovation—namely R&D expenditure, patent applications, and scientific publications. The positive relationship with researcher density further suggests that the platform may expand participation in innovation processes, particularly among younger and early-career researchers. Yang (2023) similarly finds that in resource-constrained economies, YouTube functions as a low-cost, collaborative environment for knowledge exchange and creativity, stimulating both technological and business innovation. However, a counterintuitive finding emerges regarding internet penetration, which shows a negative association with innovation proxies. While internet access is generally assumed to enhance communication, knowledge diffusion, and entrepreneurship (Asongu, 2023), the results imply that connectivity alone may be a necessary but insufficient condition for innovation. Counted and Arawole (2015) argue that uneven digital access, geo-restrictions, and platform limitations can constrain creativity and reinforce inequality, particularly in countries where digital literacy and infrastructure quality are uneven. Thus, without complementary macroeconomic and institutional enablers such as education quality, financing mechanisms, and governance reforms expanded internet access may primarily drive consumption rather than knowledge-based innovation. The findings from our analysis further emphasize that a nation’s level of openness plays a critical role in transforming knowledge into concrete innovation outcomes. In particular, increased trade openness is strongly associated with elevated patent activity, indicating that integration with international markets and cross-border knowledge flows serve as important mechanisms for technological upgrading and motivating inventive behaviour. This result is in line with both theoretical and empirical studies (see Lu et al.2024) that underscores the significance of global linkages in strengthening domestic innovation capabilities. Other macroeconomic factors such as GDP per capita and government spending on education exhibit positive but statistically insignificant effects on innovation. This is similar to the study by Robinson and Acemoglu (2012), Ndicu et al. (2024), and Mugabe (2009) that found that higher income levels and greater fiscal support for education and research strengthen innovation systems with statistically significant results. The lack of statistical significance in this study may reflect differences in temporal scope, measurement limitations, or lagged effects, as investments in education and research typically yield outcomes over long horizons. Nonetheless, Africa’s upward trajectory in patent applications and scientific publications between 2015 and 2022, compared to 2009 levels, indicates gradual progress in both macroeconomic stability and technological capacity. Despite these promising associations, several limitations warrant caution. Although fixed-effects estimations mitigate unobserved, time-invariant country differences, they cannot fully account for time-varying factors such as governance changes, infrastructure expansion, or demographic shifts that may simultaneously influence social media use and innovation. Endogeneity also remains a concern: innovation itself could increase social media adoption, creating reverse causality. Efforts to use instrumental variables—such as exogenous broadband rollouts or regulatory shocks (Czernich et al., 2011; Manacorda & Tesei, 2020)—were constrained by limited data availability, while lagged variable approaches faced identification challenges (Bellemare et al., 2017). Furthermore, innovation is multidimensional and difficult to measure solely through patents, R&D spending, and publications; much informal or grassroots innovation in Africa likely remains unrecorded. Despite these caveats, this study makes several contributions. It is among the first to empirically examine the relationship between YouTube usage and innovation across 52 African countries over 14 years, controlling for multiple macroeconomic and institutional variables. The study also challenge the prevailing assumption that internet penetration automatically translates into innovation, highlighting instead the importance of access quality, human capital, and institutional readiness. The implications are both theoretical and practical. Theoretically, the findings extend innovation and knowledge-diffusion frameworks by emphasizing the role of participatory digital platforms as low-cost innovation ecosystems in developing regions. Practically, they suggest that African governments and development partners should integrate digital literacy, creative media training, and innovation policy. Investments in broadband must be complemented by initiatives that promote productive content creation, scientific collaboration, and digital entrepreneurship. In this sense, platforms like YouTube can bridge educational and innovation gaps by connecting local talents to global knowledge networks, provided that enabling policies, research funding, and regulatory clarity exist. Future research should explore three main directions. First, disaggregated analyses at national, sectoral, and firm levels could uncover heterogeneity in how social media use influences innovation across regions and industries. Second, more attention is needed on the mechanisms of platform engagement among youth in acquiring, applying, and disseminating knowledge, and how content creation differs from passive consumption. Third, future studies should further examine enabling macroeconomic and institutional conditions such as access to finance that transform digital participation into innovation capacity. Employing quasi-experimental designs, such as exogenous digital infrastructure rollouts, would also strengthen causal inference.

5. Conclusion

This study provides empirical evidence on the relationship between social media engagement and innovation performance in Africa from 2009 to 2022, framed within the external search breadth and depth framework and emphasizing the role of youth participation. By integrating macroeconomic and institutional variables as moderating factors, the analysis offers a nuanced understanding of how digital engagement interacts with broader structural conditions shape innovation outcomes across the continent. The results suggest YouTube as a distinctive and powerful catalyst for innovation in Africa. As the platform increasingly functions as a primary channel for knowledge exchange among young people, its visually rich, interactive, and application-oriented format enhances accessibility and practical learning. These characteristics position YouTube as an informal yet potent educational tool capable of fostering creativity, problem-solving, and technological experimentation. Consequently, policymakers, educators, and development practitioners should consider leveraging YouTube and similar platforms for capacity-building initiatives, particularly those that promote youth-led content creation, collaborative learning, and context-relevant knowledge dissemination to stimulate inclusive, bottom-up innovation. Beyond the digital domain, the findings reaffirm the importance of an enabling innovation ecosystem. The analysis shows that reducing bureaucratic barriers and strengthening regulatory efficiency are significantly associated with higher innovation outputs. However, these institutional reforms are most effective when complemented by sustained investments in digital literacy, education quality, and infrastructure development. Internet connectivity, while a necessary foundation, is not sufficient on its own to generate innovation unless it is embedded within a supportive socio-economic and institutional framework. Empirically, this study contributes to the growing literature on innovation in resource-constrained contexts by positioning youth-preferred digital platforms as complementary enablers alongside traditional drivers such as R&D expenditure, institutional quality, and human capital development. The strong relationship between regulatory simplicity and innovation outcomes underscores the importance of coherent governance structures that align digital transformation with innovation policy. Future research should extend this analysis to other developing regions to assess the generalizability of these findings. Moreover, deeper exploration is needed into how specific digital platforms interact with conventional innovation systems to foster sustainable, inclusive growth. Such insights would advance both theoretical and policy understanding of how digital ecosystems can be harnessed to accelerate Africa’s innovation trajectory.

| 1 |

This study estimated an ordinary least squares estimator (OLS) for equation 1 as well as Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for all independent and control variables. All the variables showed VIF values less than 5 indicating minimal to no multicollinearity. |

References

- Adekunle, A.A.; Ellis-Jones, J.; Ajibefun, I.; Nyikal, R.A.; Bangali, S.; Fatunbi, A.O.; Angé, A. Agricultural innovation in sub-Saharan Africa: Experiences from multiple stakeholder approaches; Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa (FARA): Accra, Ghana, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alper, M.E.; Miktus, M. Bridging the mobile digital divide in sub-Saharan Africa: Costing under demographic change and urbanization; International Monetary Fund, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M. (2023). Leveraging Social Media Geographic Information for Smart Governance and Policy Making (pp. 192–213). IGI Global. [CrossRef]

- Arthur-Holmes, F.; Yeboah, T.; Cobbinah, I.J.; Busia, K.A. Youth in artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) and higher education nexus: Diffusion of innovations and knowledge transfer. Futures 2023, 152, 103201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asio, S.M., & Khorasani, S.T. (2015). Social media: A platform for innovation. In IISE Annual Conference. Proceedings (p. 1496). Institute of Industrial and Systems Engineers (IISE).

- Asongu, S.A. Mobile phone innovation and doing business in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Emerging Economies 2023, 9, 238–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayanwale, A.B.; Adekunle, A.A.; Kehinde, A.D.; Fatunbi, O.A. Participation in innovation platform and asset acquisitions among farmers in Southern Africa. Environmental and Sustainability Indicators 2023, 20, 100316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudry, C., Mouton, J., & Prozesky, H. (2018). The Next Generation of Scientists (p. 216). African Minds.

- Bellemare, M.F.; Masaki, T.; Pepinsky, T.B. Lagged explanatory variables and the estimation of causal effect. The Journal of Politics 2017, 79, 949–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E.O.; Blum, M.; Punt, M. The impact of extension and ecosystem services on smallholder’s credit constraint. The Journal of Developing Areas 2016, 50, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E.O.; Ola, O.; Lang, H.; Buchenrieder, G. Public-private cooperation and agricultural development in Sub-Saharan Africa: a review of Nigerian growth enhancement scheme and e-voucher program. Food Security 2021, 13, 129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, E.O.; Adegoke, A.; Buchenrieder, G.R. The Disenfranchisement of Practitioners and the Public Sector in Innovative Urban Farming in Sub-Saharan Africa: Insights from Nigeria. Land 2024, 13, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, J.W.; Van Mele, P.; Barres, N.F.; Okry, F.; Wanvoeke, J. Smallholders download and share videos from the Internet to learn about sustainable agriculture. International journal of agricultural sustainability 2019, 17, 92–107. [Google Scholar]

- Consentino, F.; Vindigni, G.; Spina, D.; Monaco, C.; Peri, I. An Agricultural Career through the Lens of Young People. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Counted, A.V.; Arawole, J.O. ‘We are connected, but constrained’: internet inequality and the challenges of millennials in Africa as actors in innovation. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 2015, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czernich, N.; Falck, O.; Kretschmer, T.; Woessmann, L. Broadband infrastructure and economic growth. The Economic Journal 2011, 121, 505–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Pal, P.P. Assessment of Entrepreneurship Development Through Attracting And Retaining Youth In Agriculture (ARYA). Journal of Survey in Fisheries Sciences 2023, 10, 7031–7036. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, Fernando. Innovation in Africa: Levelling the Playing Field to Promote Technology Transfer; Oxford University Press, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, R. Information needs and information-seeking behavior in developing countries: A review of the research. The International Information & Library Review 2009, 41, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO (2024). The youth barometer: Implementation of the youth target in FAO and globally – Biennium 2022–2023. Rome. [CrossRef]

- Igwe, P.A.; Odunukan, K.; Rahman, M.; Rugara, D.G.; Ochinanwata, C. How entrepreneurship ecosystem influences the development of frugal innovation and informal entrepreneurship. Thunderbird International Business Review 2020, 62, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, I.; Lee, Y. YouTube acceptance by university educators and students: A cross-cultural perspective. Innovations in education and teaching international 2015, 52, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, T.; Parry, M.E. The impact of word of mouth sources on the perceived usefulness of an innovation. Journal of Product Innovation Management 2013, 30, 1112–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, K.; Salter, A. Open for innovation: The role of openness in explaining innovation performance among U.K. manufacturing firms. Research Policy 2006, 35, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohento, K., & Ajilore, O. (2015). ICT and Youth in Agriculture. Africa agriculture status report, 118–42.

- Lu, H., Feng, Z., & Wang, S. (2024). The Impact of Economic Openness and Institutional Environment on Technological Innovation: Evidence from China’s Provincial Patent Application Data. Social Science Quarterly. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Lugamara, C.B., Urassa, J.K., Dontsop Nguezet, P.M., & Masso, C. (2019). Effectiveness of communication channels on level of awareness and determinants of adoption of improved common bean technologies among smallholder farmers in Tanzania. Agriculture and Ecosystem Resilience in Sub Saharan Africa: Livelihood Pathways Under Changing Climate, 613–632.

- Manacorda, M.; Tesei, A. Liberation technology: Mobile phones and political mobilization in Africa. Econometrica 2020, 88, 533–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugabe, J. Knowledge and Innovation for Africa’s Development. Priorities, policies and programs: A report prepared for the World Bank Institute. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Muninger, M.-I.; Mahr, D.; Hammedi, W. Social media use: A review of innovation management practices. Journal of Business Research 2022, 143, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndicu, S.; Ngui, D.; Barasa, L. Technological catch-up, innovation, and productivity analysis of national innovation systems in developing countries in Africa 2010–2018. Journal of the knowledge economy 2024, 15, 7941–7967. [Google Scholar]

- Okwu, O.J.; Daudu, S. Extension communication channels’ usage and preference by farmers in Benue State, Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development 2011, 3, 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ovhal, d. r. (2025). Evolution of social media: As innovative research and educational tool. The infinite path: research across disciplines, 136.

- Pesaran, M.H. General diagnostic tests for cross-sectional dependence in panels. Empirical Economics 2021, 60, 13–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Benton, T.G.; Bharucha, Z.P.; Dicks, L.V.; Flora, C.B.; Godfray, H.C.J.; Wratten, S. Pretty, J., Benton, T. G., Bharucha, Z. P., Dicks, L. V., Flora, C. B., Godfray, H. C. J., ... & Wratten, S. Global assessment of agricultural system redesign for sustainable intensification. Nature Sustainability 2018, 1, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raidimi, E.N.; Kabiti, H.M. Agricultural extension, research, and development for increased food security: the need for public-private sector partnerships in South Africa. South African Journal of Agricultural Extension 2017, 45, 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Reij, C., & Waters-Bayer, A. (2014). An initial analysis of farmer innovators and their innovations. In Farmer innovation in Africa (pp. 77–91). Routledge.

- Robinson, J.A., & Acemoglu, D. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity and poverty (pp. 45–47). London: Profile.

- Semingson, P. & Hall, L. (2019). Evolution of a YouTube Channel. In S. Carliner (Ed.), Proceedings of E-Learn: World Conference on E-Learning in Corporate, Government, Healthcare, and Higher Education (pp. 72–77). New Orleans, Louisiana, United States: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). Retrieved May 14, 2025 from https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/211063/. Available online:.

- Song, JS; Ngnouwal Eloundou, G.; Bitoto Ewolo, F.; Ondoua Beyene, B. Does social media contribute to economic growth? Journal of the Knowledge Economy 2024, 15, 8349–8389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StatCounter, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. Social Media Stats Worldwide StatCounter Global Stats StatCounter Global Stats. 2024. Available online: https://gs.statcounter.com/social-media-stats/all.

- United Nation. Young People’s Potential, the Key to Africa’s Sustainable Development. 2024. Available online: https://www.un.org/ohrlls/news/young-people-potential-key-africa-sustainable-development? (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Van Mele, P., Okry, F., Wanvoeke, J., Barres, N.F., Malone, P., Rodgers, J., Rahman, E., & Salahuddin, A. (2018). Quality farmer training videos to support South-South learning. CSI Transactions on ICT. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S. (2006). Encouraging innovation and productivity growth in Africa to create decent jobs. DPRU/TIPS Coherence, 18–20.

- World Bank (2024). World Development Indicators DataBank. (n.d.). https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=2&series=NY.GDP.PCAP.CD&country=#.

- Wooldridge, J.M. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M. The Impact of Innovation Capability in Increasing Enterprise Performance: Moderated by YouTube Media in Indonesia. TECHBUS (Technology, Business and Entrepreneurship) 2023, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Tingting, Y. The Mediating Role of Human Capital in the Relationship between Education Expenditure and Science and Technology Innovation: Evidence from China. Socioeconomic Challenges 2023, 7, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żmija, K., Fortes, A., Tia, M.N., Šūmane, S., Ayambila, S.N., Żmija, D.,... & Sutherland, L.A. (2020). Small farming and generational renewal in the context of food security challenges. Global Food Security, 26, 100412.Zoundji, G.C., Okry, F., Vodouhê, S.D., & Bentley, J.W. (2016). The distribution of farmer learning videos: Lessons from non-conventional dissemination networks in Benin. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 2, 1277838.

- Zondo, W.N.S.; Ndoro, J.T. Attributes of Diffusion of Innovation’s Influence on Smallholder Farmers’ Social Media Adoption in Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).