Submitted:

05 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Criteria

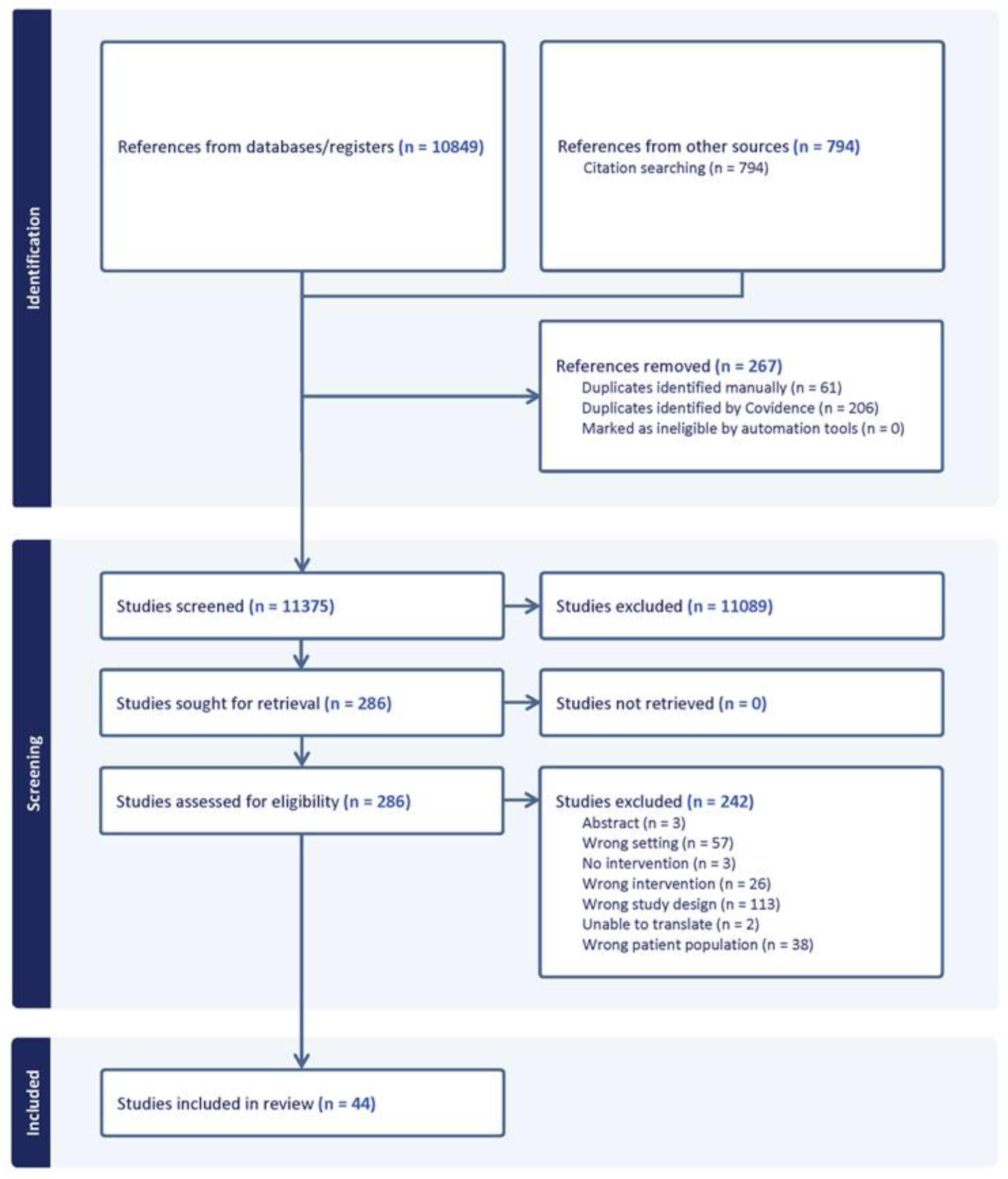

2.4. Screening and Data Management

2.5. Data Extraction and Quality Appraisal

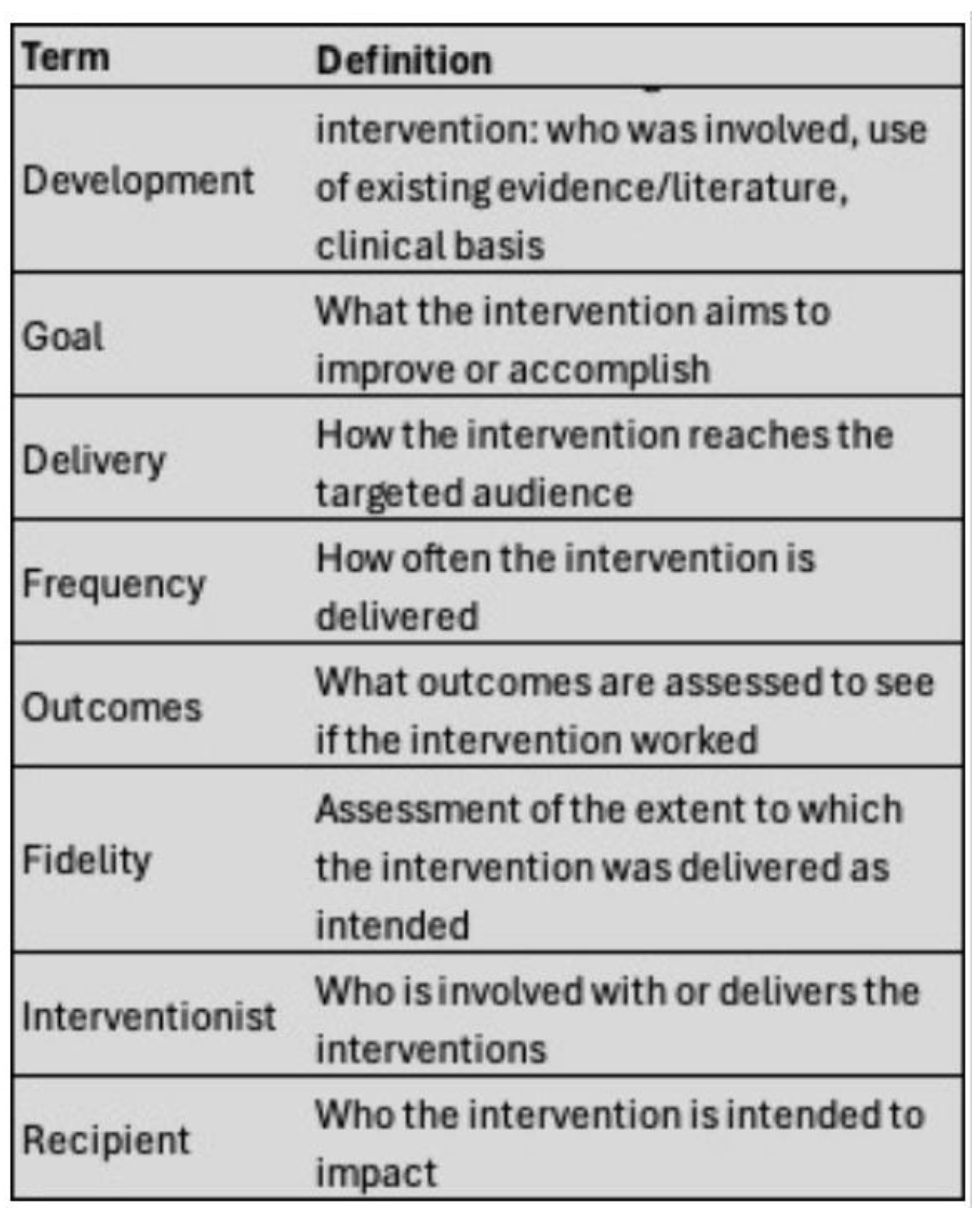

2.6. Analysis:

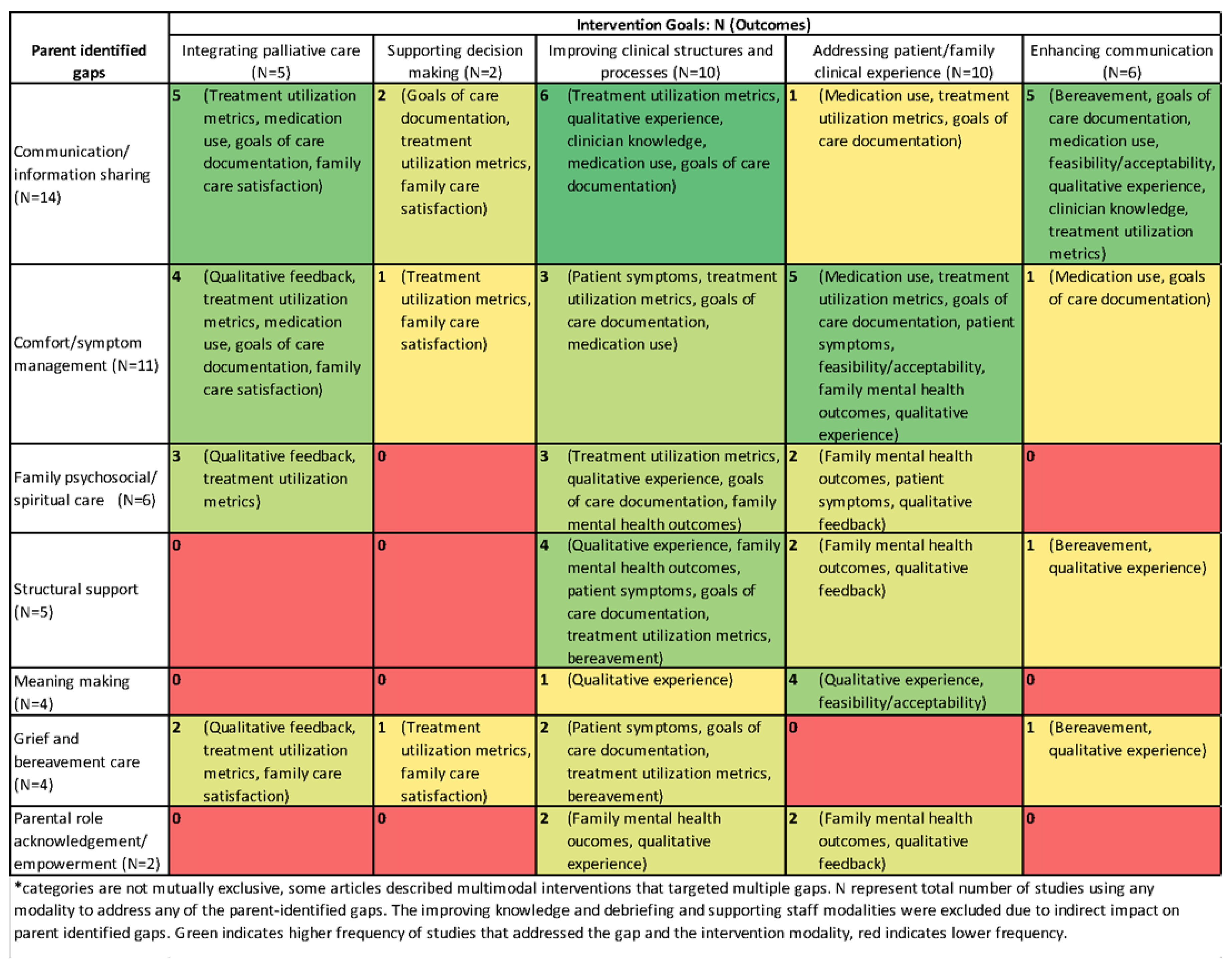

3. Results

3.1. Intervention Elements

3.2. Contextual Factors

3.3. Implementation Barriers and Facilitators

3.4. Study Rigor

4. Discussion

Limitations of Included Studies

Strengths and Limitations of Review

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PICU | Pediatric Intensive Care Unit |

| EOL | End-of-life |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| NICU | Neonatal intensive care unit |

References

- Wheeler, I. Parental Bereavement: The Crisis of Meaning. Death Studies 2001, 25, 51–66. [CrossRef]

- Klass, D. Parental Grief: Solace and Resolution; Springer Publishing Company, 1988; ISBN 978-0-8261-5930-4.

- Snaman, J.M.; Morris, S.E.; Rosenberg, A.R.; Holder, R.; Baker, J.; Wolfe, J. Reconsidering Early Parental Grief Following the Death of a Child from Cancer: A New Framework for Future Research and Bereavement Support. Support Care Cancer 2020, 28, 4131–4139. [CrossRef]

- Broden, E.G.; Werner-Lin, A.; Curley, M.A.Q.; Hinds, P.S. Shifting and Intersecting Needs: Parents’ Experiences During and Following the Withdrawal of Life Sustaining Treatments in the PICU. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing 2021, (in review. [CrossRef]

- Davies, R. New Understandings of Parental Grief: Literature Review. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2004, 46, 506–513. [CrossRef]

- Lannen, P.K.; Wolfe, J.; Prigerson, H.G.; Onelov, E.; Kreicbergs, U.C. Unresolved Grief in a National Sample of Bereaved Parents: Impaired Mental and Physical Health 4 to 9 Years Later. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2008, 26, 5870. [CrossRef]

- Meert, K.L.; Briller, S.; Schim, S.M.; Thurston, C.; Kabel, A. Examining the Needs of Bereaved Parents in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit: A Qualitative Study. Death Studies 2009, 33, 712–740. [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, K.M.; Alexander, P.M.A.; Schlapbach, L.J.; Millar, J.; Jacobe, S.; Ravindranathan, H.; Croston, E.J.; Staffa, S.J.; Burns, J.P.; Gelbart, B.; et al. Epidemiology of Childhood Death in Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Units. Intensive Care Med 2019, 45, 1262–1271. [CrossRef]

- Burns JP; Sellers DE; Meyer EC; Lewis-Newby M; Truog RD Epidemiology of Death in the PICU at Five U.S. Teaching Hospitals*. Crit Care Med 2014, 42, 2101–2108. [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, K.M.; Lelkes, E.; Kumar, R.K.; DeCourcey, D.D. Is This as Good as It Gets? Implications of an Asymptotic Mortality Decline and Approaching the Nadir in Pediatric Intensive Care. European Journal of Pediatrics 2021. [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.E.; Hall, H.; Copnell, B. The Changing Nature of Relationships between Parents and Healthcare Providers When a Child Dies in the Paediatric Intensive Care Unit. J Adv Nurs 2018, 74, 89–99. [CrossRef]

- Brooten, D.; Youngblut, J.M.; Seagrave, L.; Caicedo, C.; Hawthorne, D.; Hidalgo, I.; Roche, R. Parent’s Perceptions of Health Care Providers Actions around Child ICU Death: What Helped, What Did Not. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care 2013, 30, 40–49. [CrossRef]

- Broden, E.G.; Mazzola, E.; DeCourcey, D.D.; Blume, E.D.; Wolfe, J.; Snaman, J.M. The Roles of Preparation, Location, and Palliative Care Involvement in Parent-Perceived Child Suffering at the End of Life. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wiener, L.; Tager, J.; Mack, J.; Battles, H.; Bedoya, S.Z.; Gerhardt, C.A. Helping Parents Prepare for Their Child’s End of Life: A Retrospective Survey of Cancer-Bereaved Parents. Pediatric Blood and Cancer 2020, 67. [CrossRef]

- Feifer, D.; Broden, E.G.; Xiong, N.; Mazzola, E.; Baker, J.N.; Wolfe, J.; Snaman, J.M. Mixed-Methods Analysis of Decisional Regret in Parents Following a Child’s Death from Cancer. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 2023, n/a, e30541. [CrossRef]

- Adistie, F.; Neilson, S.; Shaw, K.L.; Bay, B.; Efstathiou, N. The Elements of End-of-Life Care Provision in Paediatric Intensive Care Units: A Systematic Integrative Review. BMC Palliative Care 2024, 23, 184. [CrossRef]

- Mu, P.-F.; Tseng, Y.-M.; Wang, C.-C.; Chen, Y.-J.; Huang, S.-H.; Hsu, T.-F.; Florczak, K.L. Nurses’ Experiences in End-of-Life Care in the PICU: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Nurs Sci Q 2019, 32, 12–22. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, L.; Fraser, L.; Noyes, J.; Taylor, J.; Hackett, J. Understanding Parent Experiences of End-of-Life Care for Children: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Palliat Med 2023, 37, 178–202. [CrossRef]

- Tezuka, S.; Kobayashi, K. Parental Experience of Child Death in the Paediatric Intensive Care Unit: A Scoping Review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e057489. [CrossRef]

- Toh, T.S.W.; Lee, J.H. Statistical Note: Using Scoping and Systematic Reviews. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 2021, 22, 572. [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2005, 8, 19–32. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Grainger, M.J.; Gray, C.T. Citationchaser: An R Package and Shiny App for Forward and Backward Citations Chasing in Academic Searching 2021.

- Jackson, J.L.; Kuriyama, A.; Anton, A.; Choi, A.; Fournier, J.-P.; Geier, A.-K.; Jacquerioz, F.; Kogan, D.; Scholcoff, C.; Sun, R. The Accuracy of Google Translate for Abstracting Data From Non–English-Language Trials for Systematic Reviews. Ann Intern Med 2019, 171, 677–679. [CrossRef]

- Covidence - Better Systematic Review Management Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap Consortium: Building an International Community of Software Platform Partners. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2019, 95, 103208. [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.; Taylor, R.; R, T.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) – A Metadata-Driven Methodology and Workflow Process for Providing Translational Research Informatics Support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2009, 42, 377–381. [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Reardon, C.M.; Opra Widerquist, M.A.; Lowery, J. Conceptualizing Outcomes for Use with the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR): The CFIR Outcomes Addendum. Implementation Science 2022, 17, 7. [CrossRef]

- Saunders, C. Care of Patients Suffering from Terminal Illness. Nursing Mirror 1964.

- Hong, Q.; Pluye, P.; Fabregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool; McGill, 2018;

- Stata Statistical Software: Release 17 2021.

- Damschroder, L.J.; Aron, D.C.; Keith, R.E.; Kirsh, S.R.; Alexander, J.A.; Lowery, J.C. Fostering Implementation of Health Services Research Findings into Practice: A Consolidated Framework for Advancing Implementation Science. Implementation Sci 2009, 4, 50. [CrossRef]

- Dedoose Available online: https://www.dedoose.com/?gad_source=1&gclid=CjwKCAiAm-67BhBlEiwAEVftNqFH47mAqW8sT8QxIw-3DjbgoymUQpW2tedyXZuy09LVGGjecoyTVxoCyEgQAvD_BwE (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Butler, A.E.; Copnell, B.; Hall, H. When a Child Dies in the PICU: Practice Recommendations From a Qualitative Study of Bereaved Parents. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2019, 20, e447–e451. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Tang, Q.; Zhu, L.H.; Peng, X.M.; Zhang, N.; Xiong, Y.E.; Chen, M.H.; Chen, K.L.; Luo, D.; Li, X.; et al. Testing a Family Supportive End of Life Care Intervention in a Chinese Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: A Quasi-Experimental Study With a Non-Randomized Controlled Trial Design. Frontiers in Pediatrics 2022, 10, 870382. [CrossRef]

- Younge, N.; Smith, P.B.; Goldberg, R.N.; Brandon, D.H.; Simmons, C.; Cotten, C.M.; Bidegain, M. Impact of a Palliative Care Program on End-of-Life Care in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Journal of Perinatology 2015, 35, 218–222. [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.D.; Shukla, R.; Baker, R.; Slaven, J.E.; Moody, K. Improving Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Providers’ Perceptions of Palliative Care through a Weekly Case-Based Discussion. Palliative Medicine Reports 2021, 2, 93–100. [CrossRef]

- Meert, K.L.; Eggly, S.; Kavanaugh, K.; Berg, R.A.; Wessel, D.L.; Newth, C.J.L.; Shanley, T.P.; Harrison, R.; Dalton, H.; Michael Dean, J.; et al. Meaning Making during Parent-Physician Bereavement Meetings after a Child’s Death. Health psychology 2015, 34, 453–461. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.E.; Kim, Y.H. Changes in the End-of-Life Process in Patients with Life-Limiting Diseases through the Intervention of the Pediatric Palliative Care Team. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12, 6588. [CrossRef]

- Cremer, R.; Binoche, A.; Noizet, O.; Fourier, C.; Leteurtre, S.; Moutel, G.; Leclerc, F. Are the GFRUP’s Recommendations for Withholding or Withdrawing Treatments in Critically Ill Children Applicable? Results of a Two-Year Survey. Journal of Medical Ethics 2007, 33, 128–133. [CrossRef]

- Drolet, C.; Roy, H.; Laflamme, J.; Marcotte, M.-E. Feasibility of a Comfort Care Protocol Using Oral Transmucosal Medication Delivery in a Palliative Neonatal Population. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2016, 19, 442–450. [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.; Jackson, K.; Sheehy, K.A.; Finkel, J.C.; Quezado, Z.M. The Use of Dexmedetomidine in Pediatric Palliative Care: A Preliminary Study. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2017, 20, 779–783. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Laksana, E.; McCrory, M.C.; Hsu, S.; Zhou, A.X.; Burkiewicz, K.; Ledbetter, D.R.; Aczon, M.D.; Shah, S.; Siegel, L.; et al. Analgesia and Sedation at Terminal Extubation: A Secondary Analysis from Death One Hour after Terminal Extubation Study Data*. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 2023, 24, 463–472. [CrossRef]

- Parry, S.M.; Staenberg, B.; Weaver, M.S. Mindful Movement: Tai Chi, Gentle Yoga, and Qi Gong for Hospitalized Pediatric Palliative Care Patients and Family Members. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2018, 21, 1212–1213. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, E.; Hayes, A.; Cerulli, L.; Miller, E.G.; Slamon, N. Legacy Building in Pediatric End-of-Life Care through Innovative Use of a Digital Stethoscope. Palliative Medicine Reports 2020, 1, 149–155. [CrossRef]

- Akard, T.F.; Duffy, M.; Hord, A.; Randall, A.; Sanders, A.; Adelstein, K.; Anani, U.E.; Gilmer, M.J. Bereaved Mothers’ and Fathers’ Perceptions of a Legacy Intervention for Parents of Infants in the NICU. J Neonatal Perinatal Med 2018, 11, 21–28. [CrossRef]

- Martel, S.L.; Ives-Baine, L. “Most Prized Possessions”: Photography as Living Relationships Within the End-of-Life Care of Newborns. Illness, Crisis & Loss 2014, 22, 311–332. [CrossRef]

- Kymre, I.G.; Bondas, T. Skin-to-Skin Care for Dying Preterm Newborns and Their Parents - A Phenomenological Study from the Perspective of NICU Nurses. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 2013, 27, 669–676. [CrossRef]

- Vesely, C.; Newman, V.; Winters, Y.; Flori, H. Bringing Home to the Hospital: Development of the Reflection Room and Provider Perspectives. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2017, 20, 120–126. [CrossRef]

- Czynski, A.J.; Souza, M.; Lechner, B.E. The Mother Baby Comfort Care Pathway: The Development of a Rooming-In-Based Perinatal Palliative Care Program. Advances in neonatal care : official journal of the National Association of Neonatal Nurses 2022, 22, 119–124. [CrossRef]

- Casas, J.; Jeppesen, A.; Peters, L.; Schuelke, T.; Magdoza, N.R.K.; Hesselgrave, J.; Loftis, L. Using Quality Improvement Science to Create a Navigator in the Electronic Health Record for the Consolidation of Patient Information Surrounding Pediatric End-of-Life Care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2021, 62, E218–E224. [CrossRef]

- Harmon, R.J.; Glicken, A.D.; Siegel, R.R. Neonatal Loss in the Intensive Care Nursery. Effects of Maternal Grieving and a Program for Intervention. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry 1984, 23, 68–71. [CrossRef]

- Carter, B.S.; Guthrie, S.O. Utility of Morbidity and Mortality Conference in End-of-Life Education in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2007, 10, 375–380. [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.J.; Bang, K.S. Development and Evaluation of a Self-Reflection Program for Intensive Care Unit Nurses Who Have Experienced the Death of Pediatric Patients. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing 2017, 47, 392–405. [CrossRef]

- Rushton, C.H.; Reder, E.; Hall, B.; Comello, K.; Sellers, D.E.; Hutton, N. Interdisciplinary Interventions to Improve Pediatric Palliative Care and Reduce Health Care Professional Suffering. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2006, 9, 922–933. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Corcoran, C.; Wawrzynski, S.E.; Mansfield, K.; Fuchs, E.; Yeates, C.; Flaherty, B.F.; Harousseau, M.; Cook, L.; Epps, J.V. Grieving Children’ Death in an Intensive Care Unit: Implementation of a Standardized Process. Journal of palliative medicine 2023, 27, 236-NA. [CrossRef]

- Woolgar, F.; Archibald, S.-J. An Exploration of Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) Staff Experiences of Attending Pre-Brief and Debrief Groups Surrounding a Patient’s Death or Redirection of Care. Journal of Neonatal Nursing 2021, 27, 352–357. [CrossRef]

- Bateman, S.T.; Dixon, R.; Trozzi, M. The Wrap-up: A Unique Forum to Support Pediatric Residents When Faced with the Death of a Child. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2012, 15, 1329–1334. [CrossRef]

- Hawes, K.; Goldstein, J.; Vessella, S.; Tucker, R.; Lechner, B.E. Providing Support for Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Health Care Professionals: A Bereavement Debriefing Program. American Journal of Perinatology 2022, 39, 401–408. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, P.; Booth, D. Copying Medical Summaries on Deceased Infants to Bereaved Parents. Acta Paediatrica, International Journal of Paediatrics 2011, 100, 1262–1266. [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.K.; Pendergrass, T.L.; Grooms, T.R.; Florez, A.R. End of Life Simulation in a Pediatric Cardiac Intensive Care Unit. Clinical Simulation in Nursing 2021, 60, 3–10. [CrossRef]

- Brock, K.E.; Tracewski, M.; Allen, K.E.; Klick, J.; Petrillo, T.; Hebbar, K.B. Simulation-Based Palliative Care Communication for Pediatric Critical Care Fellows. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2019, 36, 820–830. [CrossRef]

- Nesbit, M.J.; Hill, M.; Peterson, N. A Comprehensive Pediatric Bereavement Program: The Patterns of Your Life. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly 1997, 20, 48–62. [CrossRef]

- Scheurer, J.M.; Norbie, E.; Bye, J.K.; Villacis-Calderon, D.; Heith, C.; Woll, A.; Shu, D.; McManimon, K.; Kamrath, H.; Goloff, N. Pediatric End-of-Life Care Skills Workshop: A Novel, Deliberate Practice Approach. Academic Pediatrics 2023, 23, 860–865. [CrossRef]

- Samsel, C.; Lechner, B.E. End-of-Life Care in a Regional Level IV Neonatal Intensive Care Unit after Implementation of a Palliative Care Initiative. Journal of Perinatology 2015, 35, 223–228. [CrossRef]

- Haut, C.M.; Michael, M.; Moloney-Harmon, P. Implementing a Program to Improve Pediatric and Pediatric ICU Nurses’ Knowledge of and Attitudes Toward Palliative Care. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing 2012, 14, 71–79. [CrossRef]

- Morillo Palomo, A.; Clotet Caba, J.; Camprubi Camprubi, M.; Blanco Diez, E.; Silla Gil, J.; Riverola de Veciana, A. Implementing Palliative Care, Based on Family-Centered Care, in a Highly Complex Neonatal Unit. Jornal de Pediatria 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wolff, T.; Dorsett, C.; Connolly, A.; Kelly, N.; Turnbull, J.; Deorukhkar, A.; Clements, H.; Griffin, H.; Chhaochharia, A.; Haynes, S.; et al. Chameleon Project: A Children’s End-of-Life Care Quality Improvement Project. Bmj Open Quality 2021, 10, 9. [CrossRef]

- Ishak Tayoob, M.; Rayala, S.; Doherty, M.; Singh, H.B.; Alimelu, M.; Lingaldinna, S.; Palat, G. Palliative Care for Newborns in India: Patterns of Care in a Neonatal Palliative Care Program at a Tertiary Government Children’s Hospital. Health services insights 2024, 17, 11786329231222858-NA. [CrossRef]

- Abuhammad, S.; Almasri, R. Impact of Educational Programs on Nurses’ Knowledge and Attitude toward Pediatric Palliative Care. Palliative & Supportive Care 2022, 20, 397–406. [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.L.; Placencia, F.X.; Arnold, J.L.; Minard, C.G.; Harris, T.B.; Haidet, P.M. A Structured End-of-Life Curriculum for Neonatal-Perinatal Postdoctoral Fellows. The American journal of hospice & palliative care 2015, 32, 253–261. [CrossRef]

- Asuncion, A.M.; Cagande, C.; Schlagle, S.; McCarty, B.; Hunter, K.; Milcarek, B.; Staman, G.; Da Silva, S.; Fisher, D.; Graessle, W. A Curriculum to Improve Residents’ End-of-Life Communication and Pain Management Skills During Pediatrics Intensive Care Rotation: Pilot Study. Journal of graduate medical education 2013, 5, 510–513. [CrossRef]

- Shorey, S.; Chua, C. Nurses and Nursing Students’ Experiences on Pediatric End-of-Life Care and Death: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Nurse Education Today 2022, 112, 105332. [CrossRef]

- Lyons, K.A.; Middleton, A.A.; Farley, A.A.; Henderson, N.E.; Peterson, E.B. End-of-Life Care Education in Pediatric Critical Care Medicine Fellowship Programs: Exploring Fellow and Program Director Perspectives. J Palliat Med 2023, 26, 1217–1224. [CrossRef]

- Hirani, R.; Khuram, H.; Elahi, A.; Maddox, P.A.; Pandit, M.; Issani, A.; Etienne, M. The Need for Improved End-of-Life Care Medical Education: Causes, Consequences, and Strategies for Enhancement and Integration. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2024, 41, 5–7. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Smothers, A.; Fang, W.; Borland, M. Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Perception of End-of-Life Care Education Placement in the Nursing Curriculum. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2019, 21, E12–E18. [CrossRef]

- Woods-Hill, C.Z.; Wolfe, H.; Malone, S.; Steffen, K.M.; Agulnik, A.; Flaherty, B.F.; Barbaro, R.P.; Dewan, M.; Kudchadkar, S. Implementation Science Research in Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2023, 24, 943–951. [CrossRef]

- Ista, E.; van Dijk, M. Moving Away From Randomized Controlled Trials to Hybrid... : Pediatric Critical Care Medicine.

- Steffen, K.M.; Holdsworth, L.M.; Ford, M.A.; Lee, G.M.; Asch, S.M.; Proctor, E.K. Implementation of Clinical Practice Changes in the PICU: A Qualitative Study Using and Refining the iPARIHS Framework. Implementation Science 2021, 16, 15. [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.E.; Hall, H.; Copnell, B. Becoming a Team: The Nature of the Parent-Healthcare Provider Relationship When a Child Is Dying in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Journal of Pediatric Nursing: Nursing Care of Children and Families 2018, 40, e26–e32. [CrossRef]

- Barratt, M.; Bail, K.; Lewis, P.; Paterson, C. Nurse Experiences of Partnership Nursing When Caring for Children with Long-Term Conditions and Their Families: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2024, 33, 932–950. [CrossRef]

- Short, S.R.; Thienprayoon, R. Pediatric Palliative Care in the Intensive Care Unit and Questions of Quality: A Review of the Determinants and Mechanisms of High-Quality Palliative Care in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU). Transl Pediatr 2018, 7, 326–343. [CrossRef]

- Boss, R.; Nelson, J.; Weissman, D.; Campbell, M.; Curtis, R.; Frontera, J.; Gabriel, M.; Lustbader, D.; Mosenthal, A.; Mulkerin, C.; et al. Integrating Palliative Care into the PICU: A Report from the Improving Palliative Care in the ICU Advisory Board. Pediatric critical care medicine : a journal of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical Care Societies 2014, 15, 762–767. [CrossRef]

- Hemming, K.; Haines, T.P.; Chilton, P.J.; Girling, A.J.; Lilford, R.J. The Stepped Wedge Cluster Randomised Trial: Rationale, Design, Analysis, and Reporting. BMJ 2015, 350, h391. [CrossRef]

| Category | Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 44 | |

| Study design | Mixed Methods | 3 (7%) |

| Other1 | 8 (18%) | |

| Qualitative | 4 (9%) | |

| Quantitative descriptive | 12 (27%) | |

| Quantitative non-randomized | 17 (39%) | |

| Unit type2 | General PICU | 10 (23%) |

| PCICU | 4 (9%) | |

| NICU | 28 (64%) | |

| Other unit type | 2 (5%) | |

| Palliative care domains* | Physical | 34 (77%) |

| Physical alone | 5 (11%) | |

| Emotional/psychological | 38 (86%) | |

| Emotional alone | 1 (2%) | |

| Spiritual Domain | 25 (57%) | |

| Spiritual alone | 0 | |

| Social Domain | 30 (68%) | |

| Social Alone | 0 | |

| Multiple | 38 (86%) | |

| Interventionist Role3 | Interprofessional team + family | 2 (5%) |

| Research team | 4 (10%) | |

| Supportive care consultants | 7 (17%) | |

| Physician | 6 (14%) | |

| Nurse | 3 (7%) | |

| Interprofessional team | 10 (24%) | |

| ICU clinical team | 5 (12%) | |

| Palliative care team | 2 (5%) | |

| External education team | 3 (7%) | |

| Nurse(s) involved | 18 (41%) | |

| Sample* | Patients | 14 (32%) |

| Parent/family | 10 (23%) | |

| Clinicians | 28 (64%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).