Submitted:

13 September 2025

Posted:

09 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

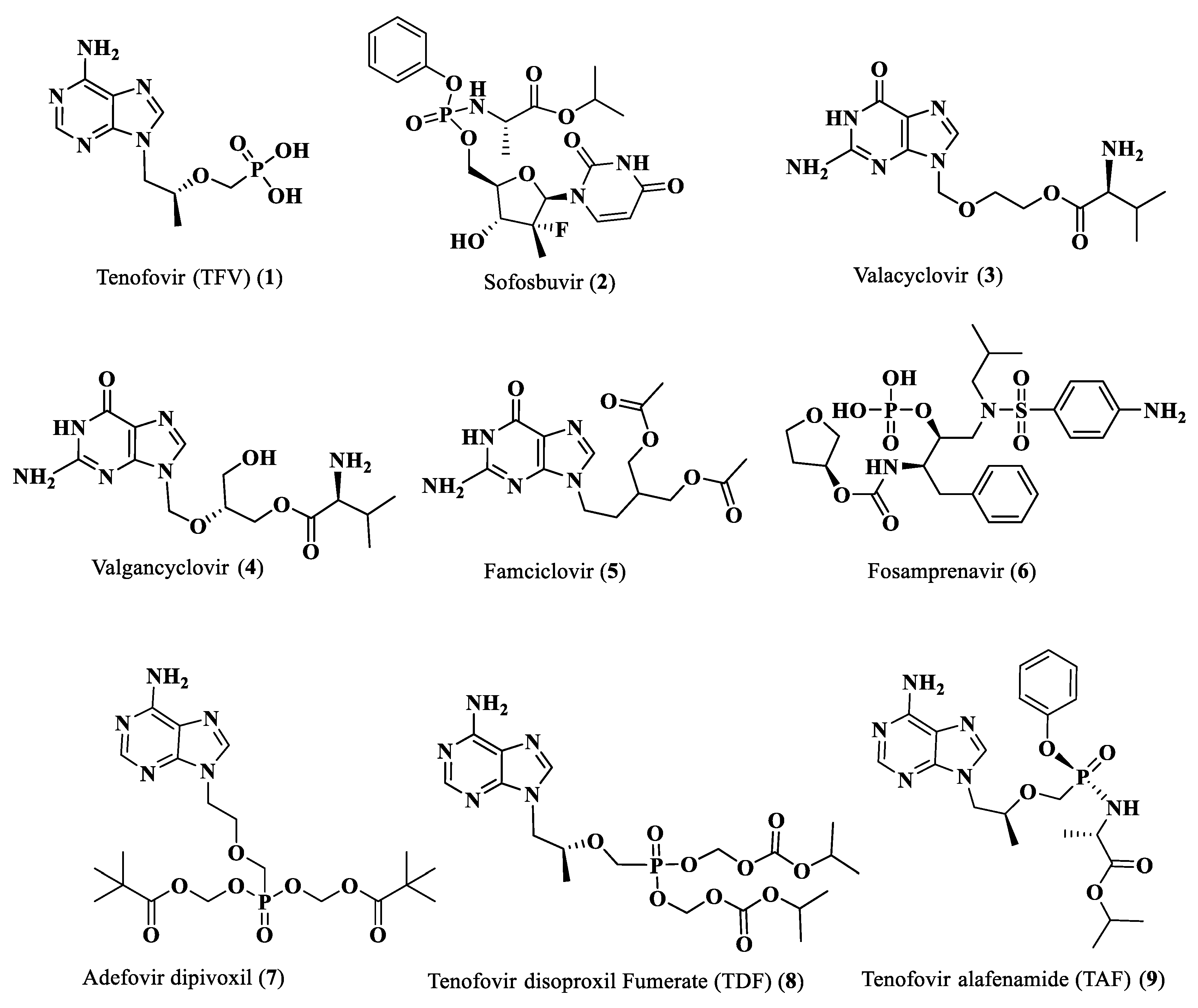

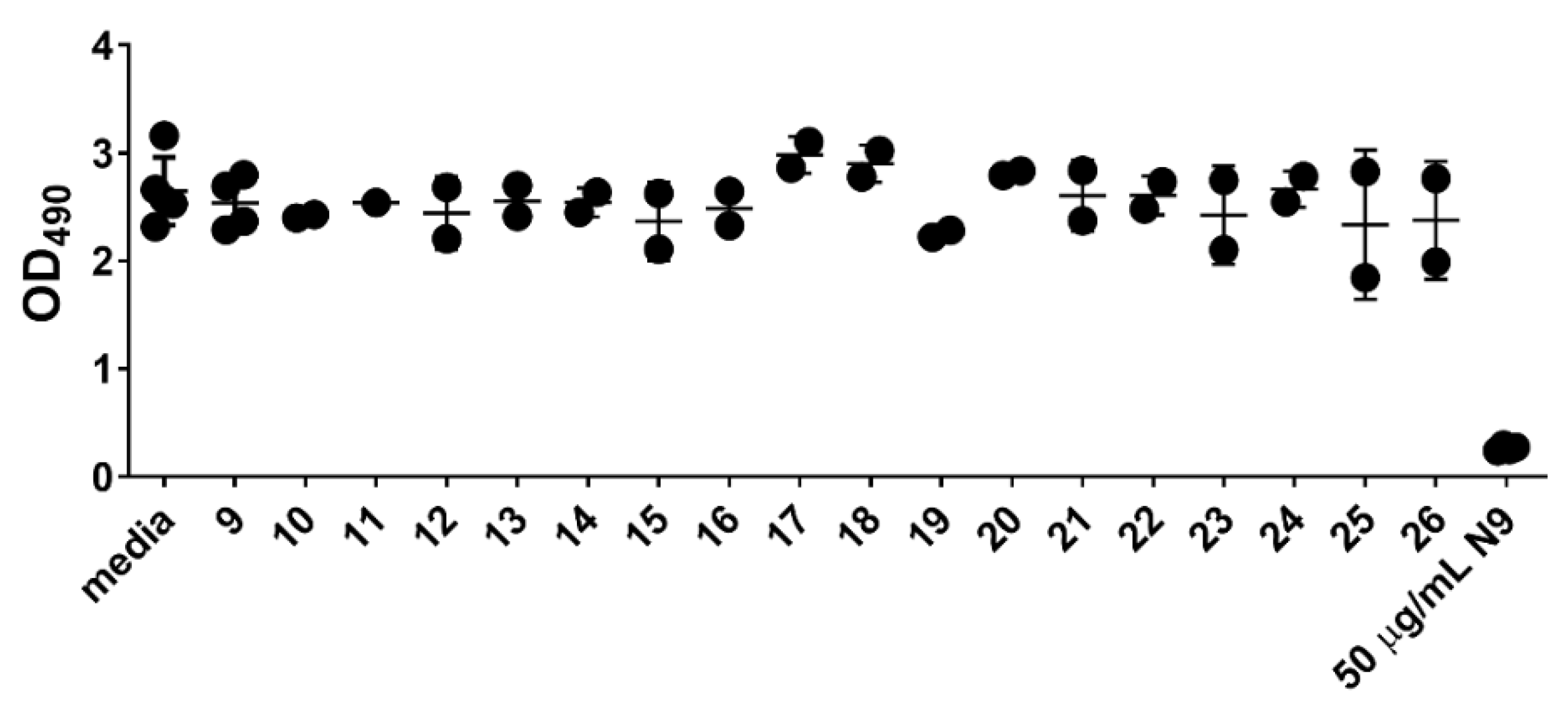

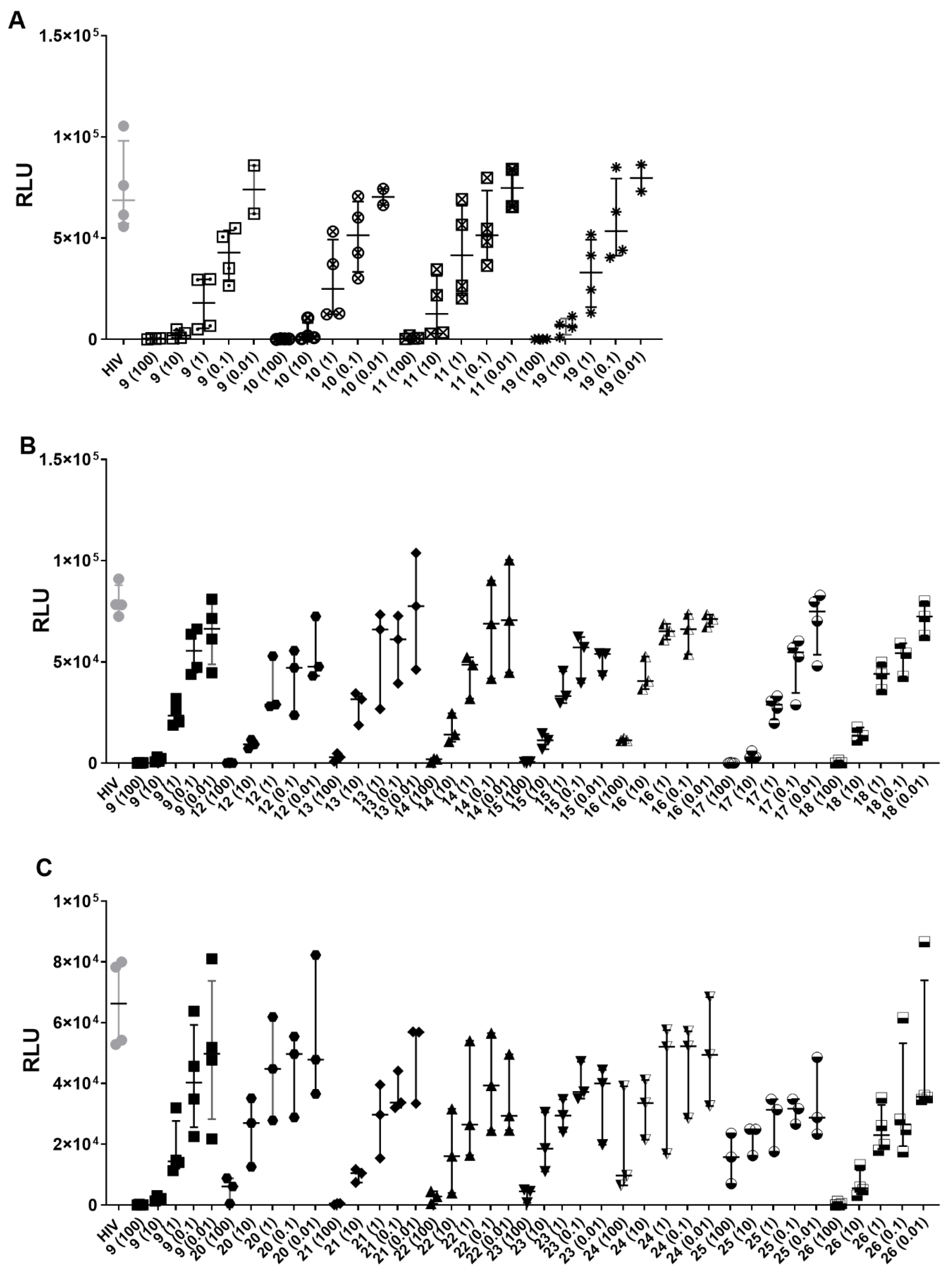

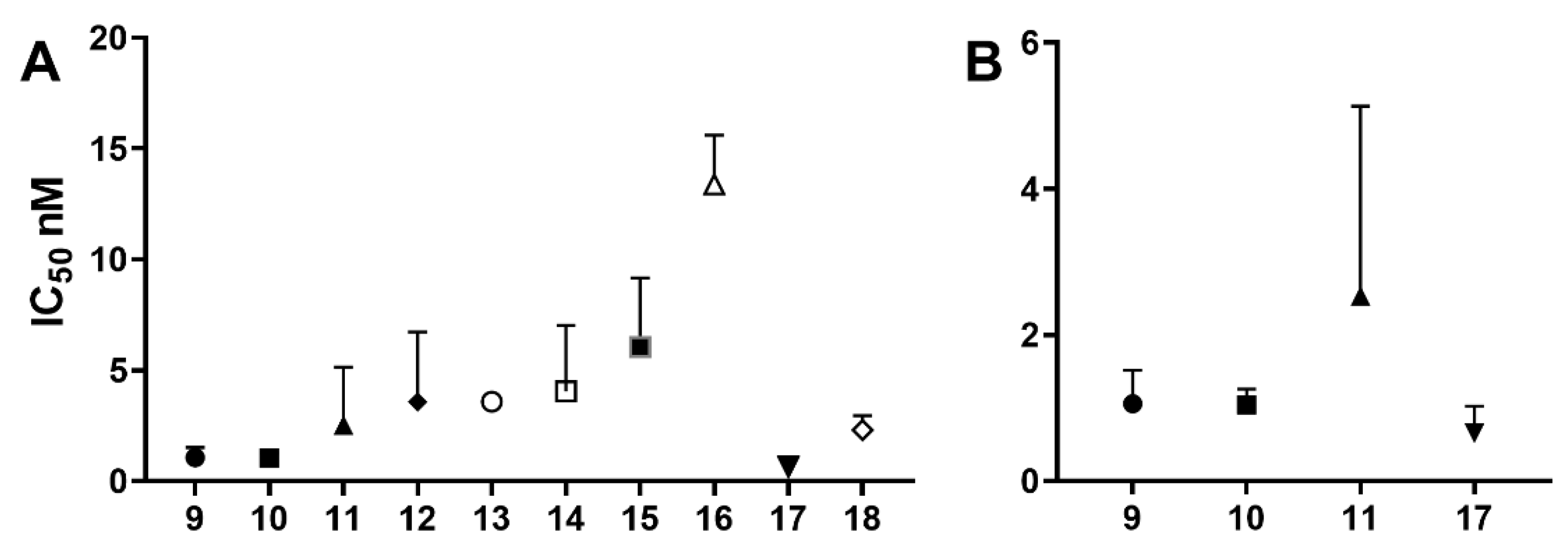

The activity of nucleoside and nucleotide analogs as antiviral agents requires phosphorylation by intracellular enzymes. Phosphate-substituted analogs have low bioavailability due to the presence of ionizable negatively-charged groups. To circumvent this limitation, several prodrug approaches have been proposed and developed. Herein, we hypothesized that the conjugation of anti-HIV fatty acids with the nucleotide tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) (1) could improve the anti-HIV activity of the nucleotide. Several fatty acyl amide conjugates of TAF were synthesized and evaluated in comparative studies with TAF. The synthesized compounds were evaluated as racemic mixtures for anti-HIV activity in vitro in a single-round HIV-1 infection assay using TZM-bl cells at concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 100 ng/mL. Tetradecanoyl TAF conjugate 10 and palmitoyl TAF conjugate 17 had higher CLogP and displayed comparable activity to TAF (96-99% inhibition at 10–100 ng/mL) but at lower molar concentrations. The IC50 of conjugate 17 (0.65 nM) was lower than that of TAF (1.06 nM); however, this difference was not statistically significant.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemistry

2.2. Biological Activities

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General

3.2. Chemistry

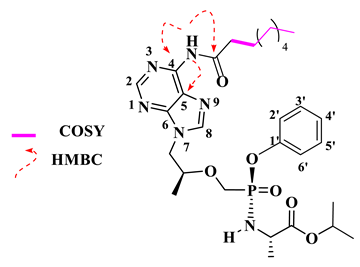

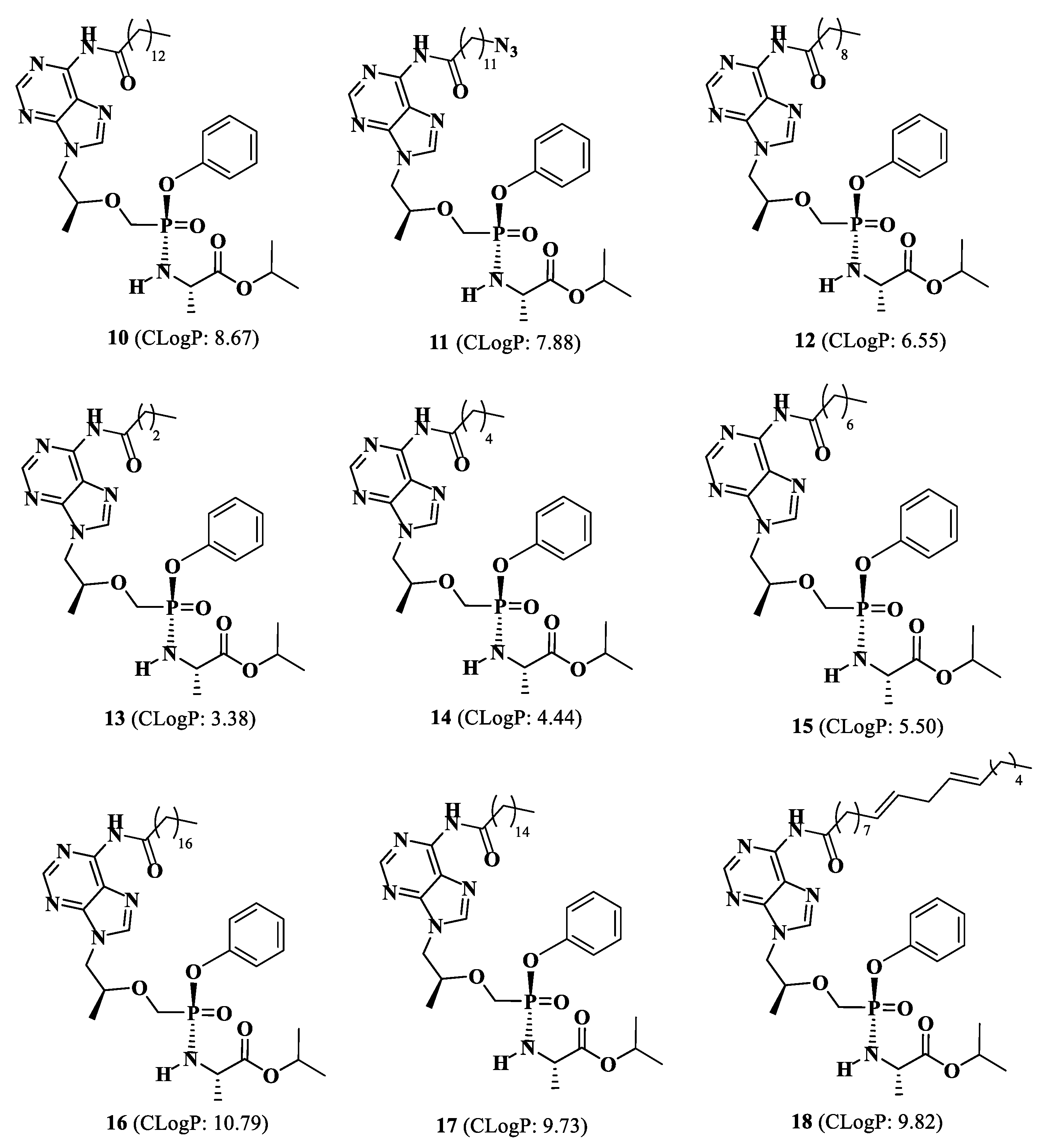

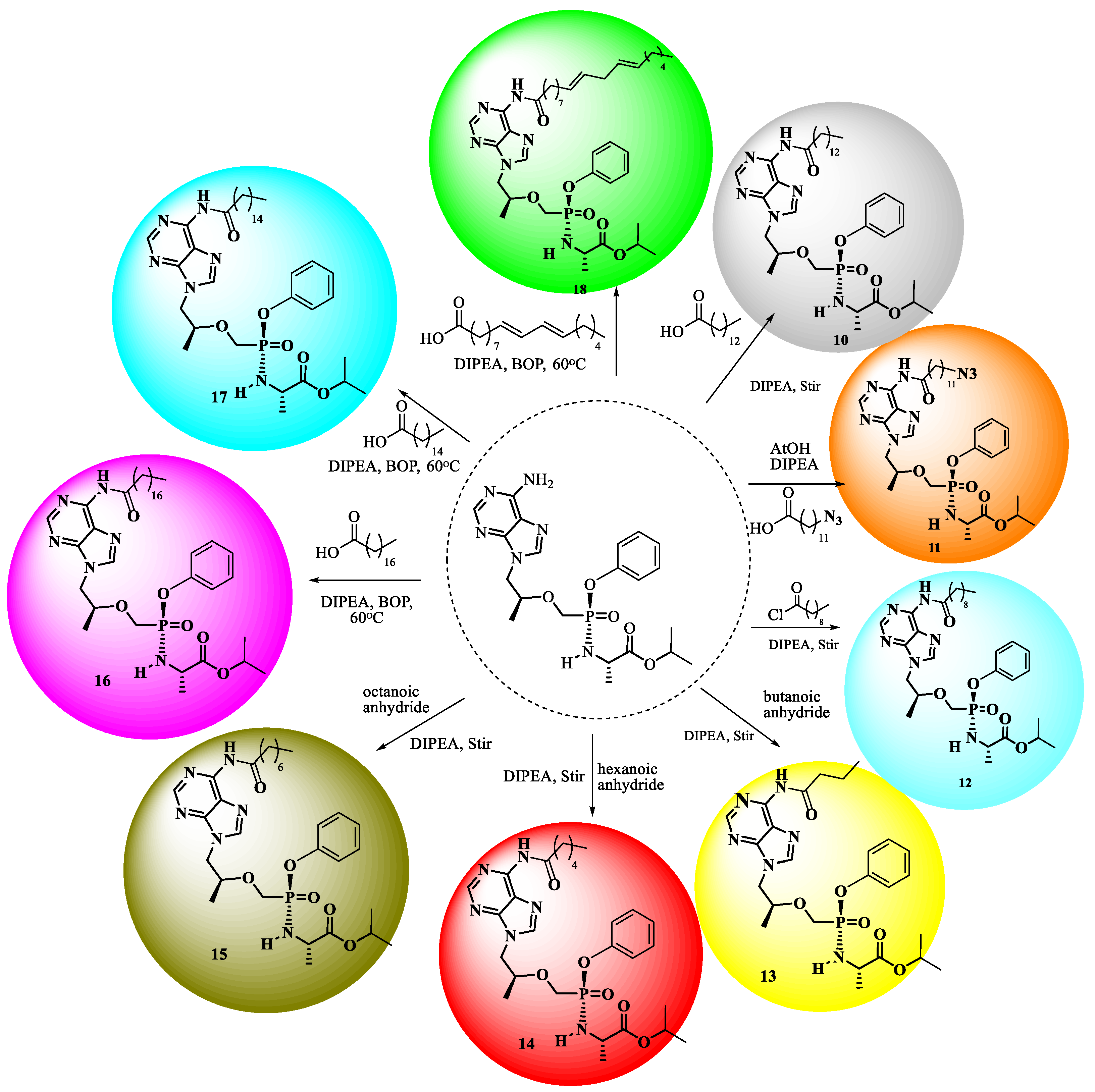

Isopropyl(phenoxy((((S)-1-(6-tetradecanamido-9H-purin-9-yl)propan-2-yl)oxy)methyl)phosphoryl)-L-alaninate (10).

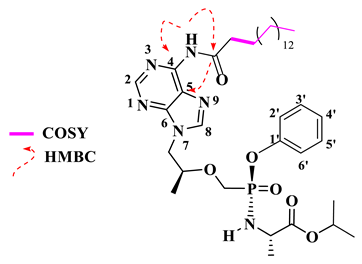

Isopropyl(((((S)-1-(6-(12-azidododecanamido)-9H-purin-9-yl)propan-2-yl)oxy)methyl)(phenoxy)phosphoryl)-L-alaninate (11).

Isopropyl(((((S)-1-(6-decanamido-9H-purin-9-yl)propan-2-yl)oxy)methyl)(phenoxy)phosphoryl)-L-alaninate (12)

Isopropyl (((((S)-1-(6-butyramido-9H-purin-9-yl)propan-2-yl)oxy)methyl)(phenoxy)phosphoryl)-L-alaninate (13).

Isopropyl (((((S)-1-(6-hexanamido-9H-purin-9-yl)propan-2yl)oxy)methyl)(phenoxy)phosphoryl)-L-alaninate (14).

Isopropyl (((((S)-1-(6-octanamido-9H-purin-9-yl)propan-2-yl)oxy)methyl)(phenoxy)phosphoryl)-L-alaninate (15).

Isopropyl (phenoxy((((S)-1-(6-stearamido-9H-purin-9-yl)propan-2-yl)oxy)methyl)phosphoryl)-L-alaninate (16).

Isopropyl (((((S)-1-(6-palmitamido-9H-purin-9-yl)propan-2-yl)oxy)methyl)(phenoxy)phosphoryl)-L-alaninate (17)

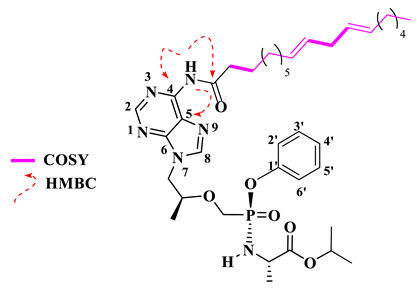

Isopropyl (((((S)-1-(6-((9E,12E)-octadeca-9,12-dienamido)-9H-purin-9-yl)propan-2-yl)oxy)methyl)(phenoxy)phosphoryl)-L-alaninate (18).

The Preparation of Physical Mixtures

3.3. Cytotoxicity and Anti-HIV Assays

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNAIDS (2025). “Global HIV & AIDS statistics—Fact sheet.” from https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet.

- Campiani, G.; Ramunno, A.; Maga, G.; Nacci, V.; Fattorusso, C.; Catalanotti, B.; Novellino, E. Non-nucleoside HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT) inhibitors: Past, present, and future perspectives. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2002, 8, 615–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez-Arias, L.; Delgado, R. Update and latest advances in antiretroviral therapy. Trends Pharm. Sci. 2022, 43, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Administration, U. S. FDA (2022). “HIV treatment.” https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv/hiv-treatment.

- Shirvani, P.; Fassihi, A.; Saghaie, L. Recent Advances in the Design and Development of Non-nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor Scaffolds. Med. Chem. 2019, 14, 52–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettmayer, P.; Amidon, G.L.; Clement, B.; Testa, B. Lessons learned from marketed and investigational prodrugs. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 2393–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, A. Chemical aspects of selective toxicity. Nature 1958, 182, 421–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asselah, T. Sofosbuvir for the treatment of hepatitis C virus. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2014, 15, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostetler, K.Y.; Beadle, J.R.; Hornbuckle, W.E.; Bellezza, C.A.; Tochkov, I.A.; Cote, P.J.; Tennant, B.C. Antiviral activities of oral 1-O-hexadecylpropanediol-3-phosphoacyclovir and acyclovir in woodchucks with chronic woodchuck hepatitis virus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 1964–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostetler, K.Y.; Rybak, R.J.; Beadle, J.R.; Gardner, M.F.; Aldern, K.A.; Wright, K.N.; Kern, E.R. In vitro and in vivo activity of 1-O-hexadecylpropane-diol-3-phospho-ganciclovir and 1-O-hexadecylpropanediol-3-phospho-penciclovir in cytomegalovirus and Herpes simplex Virus Infections. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2001, 12, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, S.; Blum, M.R.; Doucette, M.; Burnette, T.; Cederberg, D.M.; de Miranda, P.; Smiley, M.L. Pharmacokinetics of the acyclovir pro-drug valaciclovir after escalating single-and multiple-dose administration to normal volunteers. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1993, 54, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steingrimsdottir, H.; Gruber, A.; Palm, C.; Grimfors, G.; Kalin, M.; Eksborg, S. Bioavailability of aciclovir after oral administration of acyclovir, and its prodrug valaciclovir to patients with leukopenia after chemotherapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 207–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biron, K.K. Antiviral drugs for cytomegalovirus diseases. Antivir. Res. 2006, 71, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, R.V. Famciclovir and penciclovir. The mode of action of famciclovir including its conversion to penciclovir. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 1993, 4, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wire, M.B.; Shelton, M.J.; Studenberg, S. Fosamprenavir. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2006, 45, 137–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naesens, L.; Bischofberger, N.; Augustijns, P.; Annaert, P.; Van den Mooter, G.; Arimilli, M.N.; De Clercq, E. Antiretroviral efficacy and pharmacokinetics of oral bis (isopropyloxycarbonyloxymethyl) 9-(2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl) adenine in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998, 42, 1568–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulato, A.S.; Cherrington, J.M. Anti-HIV activity of adefovir (PMEA) and PMPA in combination with antiretroviral compounds: In vitro analyses. Antivir. Res. 1997, 36, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofia, M.J.; Bao, D.; Chang, W.; Du, J.; Nagarathnam, D.; Rachakonda, S.; Furman, P.A. Discovery of a β-d-2′-deoxy-2′-α-fluoro-2′-β-C-methyluridine nucleotide prodrug (PSI-7977) for the treatment of hepatitis C virus. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 7202–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackman, R.L. Phosphoramidate Prodrugs Continue to Deliver, The Journey of remdesivir (GS-5734) from RSV to SARS-CoV-2. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.J.; Hinner, M.J. Getting across the cell membrane: An overview for small molecules, peptides, and proteins. Site-Specif. Protein Labeling 2015, 13, 29–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lyseng-Williamson, K.A.; Reynolds, N.A.; Plosker, G.L. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate: A review of its use in the management of HIV infection. Drugs 2005, 65, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, M.G.; De Seigneux, S.; Lucas, G.M. Clinical pharmacology in HIV therapy. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 14, 435–444. [Google Scholar]

- Birkus, G.; Kutty, N.; He, G.X.; Mulato, A.; Lee, W.; McDermott, M.; Cihlar, T. Activation of 9-[(R)-2-[[(S)-[[(S)-1-(Isopropoxycarbonyl) ethyl] amino] phenoxyphosphinyl]-methoxy] propyl] adenine (GS-7340) and other tenofovir phosphonoamidate prodrugs by human proteases. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008, 74, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, E.J.; He, G.X.; Lee, W.A. Metabolism of GS-7340, a novel phenyl monophosphoramidate intracellular prodrug of PMPA, in blood. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2001, 20, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.A.; He, G.X.; Eisenberg, E.; Cihlar, T.; Swaminathan, S.; Mulato, A.; Cundy, K.C. Selective intracellular activation of a novel prodrug of the human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase inhibitor tenofovir leads to preferential distribution and accumulation in lymphatic tissue. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 1898–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venter, W.D.; Moorhouse, M.; Sokhela, S.; Fairlie, L.; Mashabane, N.; Masenya, M.; Hill, A. Dolutegravir plus two different prodrugs of tenofovir to treat HIV. N. Eng. J. Med. 2019, 9, 803–815. [Google Scholar]

- Kirtane, A.R.; Abouzid, O.; Minahan, D.; Bensel, T.; Hill, A.L.; Selinger, C.; Traverso, G. Development of an oral once-weekly drug delivery system for HIV antiretroviral therapy. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pemmaraju, B.; Agarwal, H.K.; Oh, D.; Buckheit, K.W.; Buckheit Jr, R.W.; Tiwari, R.; Parang, K. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 5′-O-dicarboxylic fatty acyl monoester derivatives of anti-HIV nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Tet. Lett. 2014, 55, 1983–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langner, C.A.; Travis, J.K.; Caldwell, S.J.; Tianbao, J.E.; Li, Q.; Bryant, M.L.; Devadas, B.; Gokel, G.W.; Kobayashi, G.S.; Gordon, J.I. 4-Oxatetradecanoic acid is fungicidal for Cryptococcus neoformans and inhibits replication of human immunodeficiency virus. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 17159–17169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parang, K.; Wiebe, L.I.; Knaus, E.E.; Huang, J.S.; Tyrrell, D.L. In vitro anti-hepatitis B virus activities of 5′-O-myristoyl analogue derivatives of 3′-fluoro-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine (FLT) and 3′-azido-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine (AZT). J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 1998, 1, 107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, H.K.; Loethan, K.; Mandal, D.; Doncel, G.F.; Parang, K. Synthesis and biological evaluation of fatty acyl ester derivatives of 2′,3′-didehydro-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 1917–1921. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, H.K.; Chhikara, B.S.; Bhavaraju, S.; Mandal, D.; Doncel, G.F.; Parang, K. Emtricitabine prodrugs with improved anti-HIV activity and cellular uptake. Mol. Pharm. 2013, 10, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, H.K.; Chhikara, B.S.; Hanley, M.J.; Ye, G.; Doncel, G.F.; Parang, K. Synthesis and biological evaluation of fatty acyl ester derivatives of (-)-2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 4861–4871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parang, K.; Wiebe, L.I.; Knaus, E.E.; Huang, J.-S.; Tyrrell, D.L.; Csizmadia, F. In vitro antiviral activities of myristic acid analogs against human immunodeficiency and hepatitis B viruses. Antivir. Res. 1997, 34, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, A.; Ouattara, L. A.; El-Sayed, N. S.; Verma, A.; Doncel, G. F.; Choudhary, M. I.; Siddiqui, H.; Parang, K. , Synthesis and Evaluation of Anti-HIV Activity of Mono- and Di-Substituted Phosphonamidate Conjugates of Tenofovir. Molecules 2022, 27, 4447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, A.; Ouattara, L.A.; El-Sayed, N.S.; Verma, A.; Doncel, G.F.; Choudhary, M.I.; Siddiqui, H.; Parang, K. RETRACTED: Qureshi et al. Synthesis and Evaluation of Anti-HIV Activity of Mono- and Di-Substituted Phosphonamidate Conjugates of Tenofovir. Molecules 2022, 27, 4447. Molecules 2025, 30, 3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, M.L.; McWherter, C.A.; Kishore, N.S.; Gokel, G. W.; Gordon, J.I. MyristolyCoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase as a therapeutic target for inhibiting replication of human immunodeficiency virus-1. Perspectives in Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 1993, 1, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | [Concentration] ng/ml | % HIV (HIV-1BAL) Inhibition | Compound | [Concentration] ng/ml | % HIV (HIV-1BAL) Inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 100 | 99.6 | 18 | 100 | 99.6 |

| 10 | 97.3 | 10 | 81.5 | ||

| 1 | 74.6 | 1 | 40.8 | ||

| 0.1 | 45.6 | 0.1 | 28.2 | ||

| 0.01 | 19.5 | 0.01 | 0.7 | ||

| 10 | 100 | 99.6 | 19 | 100 | 99.7 |

| 10 | 98.4 | 10 | 91.7 | ||

| 1 | 70.9 | 1 | 60.4 | ||

| 0.1 | 33 | 0.1 | 27.9 | ||

| 0.01 | 21.1 | 0.01 | 8.6 | ||

| 11 | 100 | 99.4 | 20 | 100 | 92.4 |

| 10 | 86.6 | 10 | 53.6 | ||

| 1 | 43.4 | 1 | 46.1 | ||

| 0.1 | 30.4 | 0.1 | 36.2 | ||

| 0.01 | 17 | 0.01 | 8.6 | ||

| 12 | 100 | 99.7 | 21 | 100 | 98.9 |

| 10 | 89.2 | 10 | 83.8 | ||

| 1 | 57.3 | 1 | 45.7 | ||

| 0.1 | 37.4 | 0.1 | 40 | ||

| 0.01 | 34.5 | 0.01 | 22.3 | ||

| 13 | 100 | 96.4 | 22 | 100 | 94.9 |

| 10 | 58.1 | 10 | 70.9 | ||

| 1 | 18.1 | 1 | 53.5 | ||

| 0.1 | 25.3 | 0.1 | 28.1 | ||

| 0.01 | 0 | 0.01 | 41 | ||

| 14 | 100 | 97.2 | 23 | 100 | 92.8 |

| 10 | 83.3 | 10 | 65 | ||

| 1 | 36.6 | 1 | 45.6 | ||

| 0.1 | 7 | 0.1 | 33.7 | ||

| 0.01 | 2.8 | 0.01 | 41.4 | ||

| 15 | 100 | 99.3 | 24 | 100 | 81.2 |

| 10 | 85.7 | 10 | 45.8 | ||

| 1 | 55.6 | 1 | 29.5 | ||

| 0.1 | 29.4 | 0.1 | 22.1 | ||

| 0.01 | 34.1 | 0.01 | 11.5 | ||

| 16 | 100 | 84.6 | 25 | 100 | 75.4 |

| 10 | 48 | 10 | 66 | ||

| 1 | 16.6 | 1 | 55.5 | ||

| 0.1 | 11.2 | 0.1 | 48.3 | ||

| 0.01 | 10.8 | 0.01 | 48.6 | ||

| 17 | 100 | 99.85 | 26 | 100 | 99.45 |

| 10 | 96.45 | 10 | 91.55 | ||

| 1 | 61.9 | 1 | 63.85 | ||

| 0.1 | 29.05 | 0.1 | 57.75 | ||

| 0.01 | 4.3 | 0.01 | 35.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).