Submitted:

04 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- The definition of a formal criterion of information sufficiency that determines when the system has reached grammatical stability.

- The criteria exploit the properties of periodic systems, based on information criteria to learn the most significant grammar rules.

- A discrete model criteria based on right grammars to symbolically represent movement trajectories in video sequences.

- A criterion to encode a state-based system, the different trajectories through the SEQUITUR approach for inferencing the grammar structure in the most compact representation of movement patterns.

2. Proposed Model

2.1. Motion Modeling

2.2. Trajectory Generation Process

2.3. Grammar Inference

3. Information Sufficiency Criterion

3.1. Movement Paths and Regions

3.2. Movement Regions and State Discovering Process

3.3. Automatic Rules Discover

4. Experimental Analysis and Results

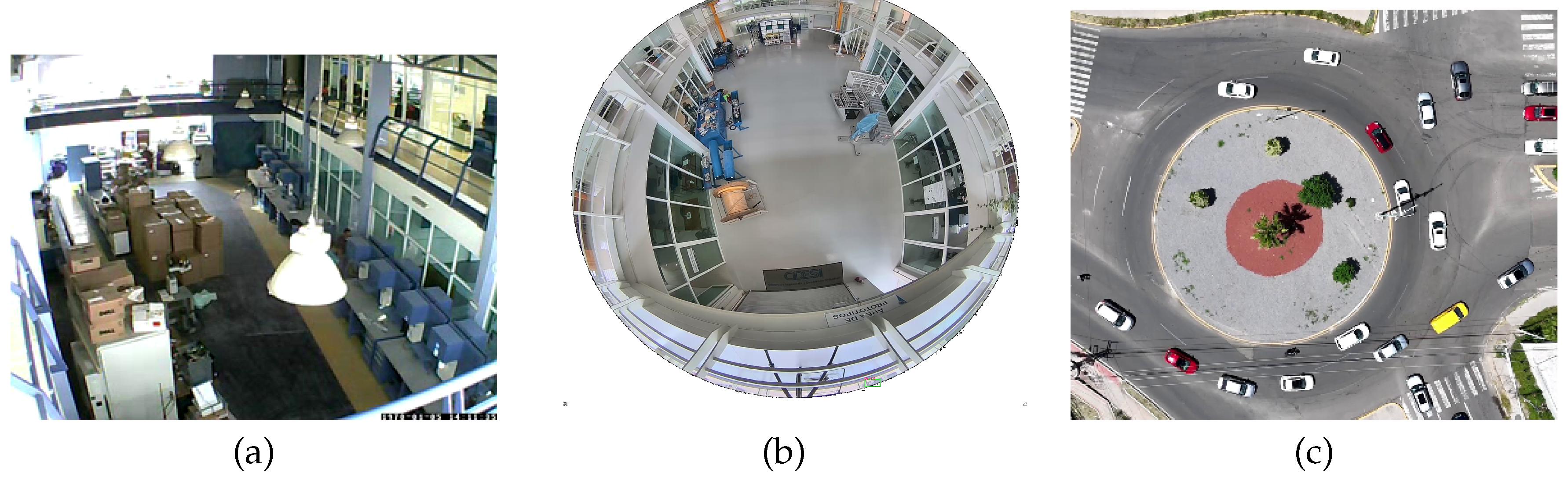

4.1. Experimental Process

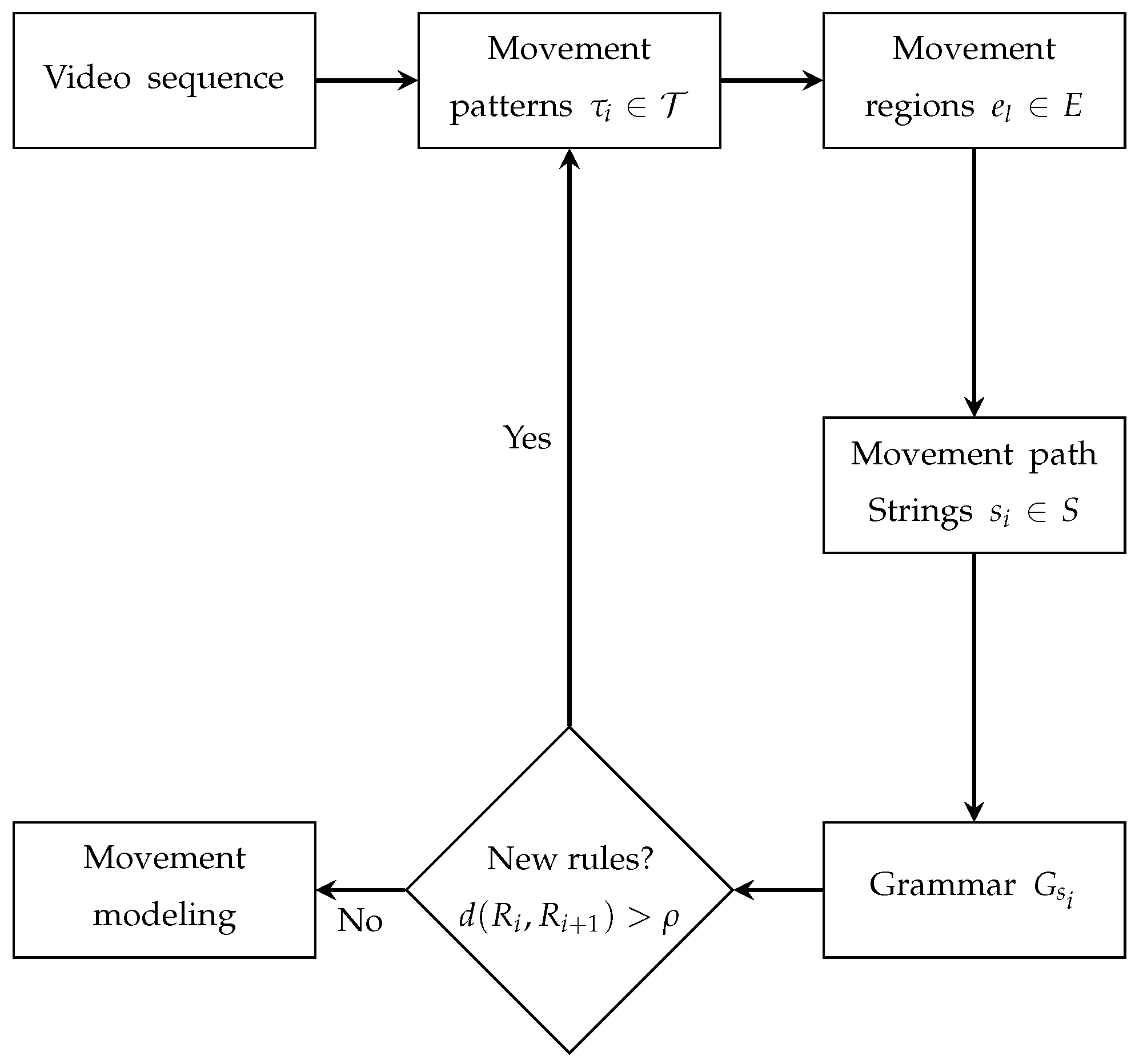

- 1.

- Obtaining trajectories. The trajectories of the movement observed in the scene represented by the set are obtained during the scene modeling process. This set contains multiple trajectories detected and enumerated incrementally, defined as . Each trajectory is composed of a sequence of positions , which describe the movement pattern associated with the intensity of pixel at position corresponding to the movement captured in the scene over time t.

- 2.

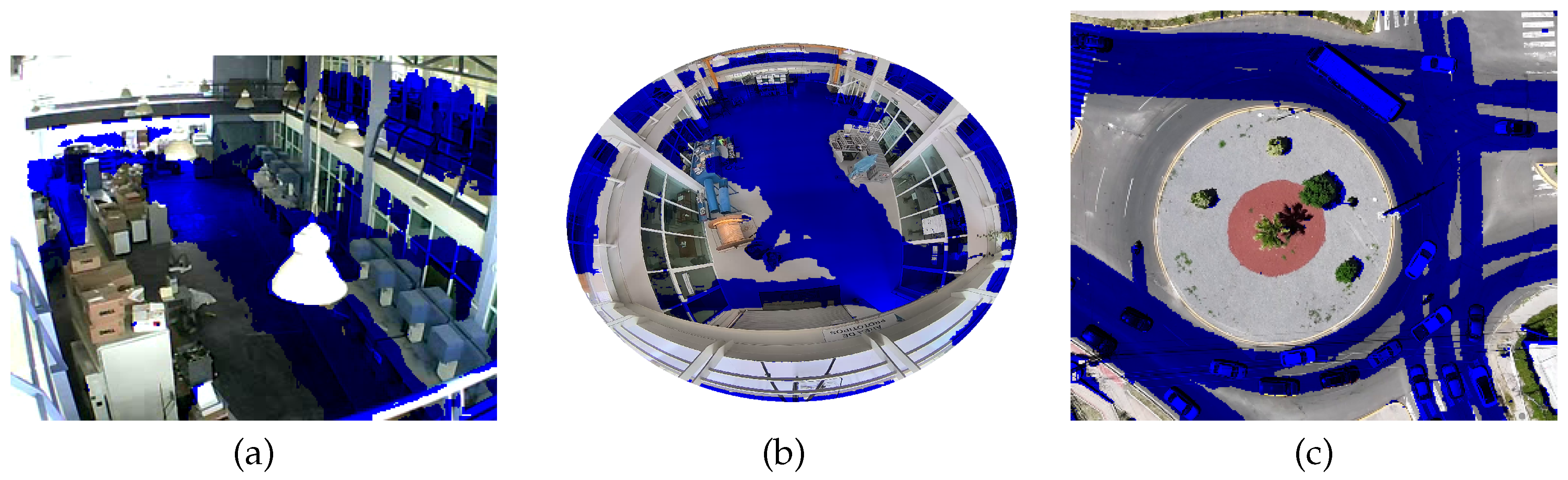

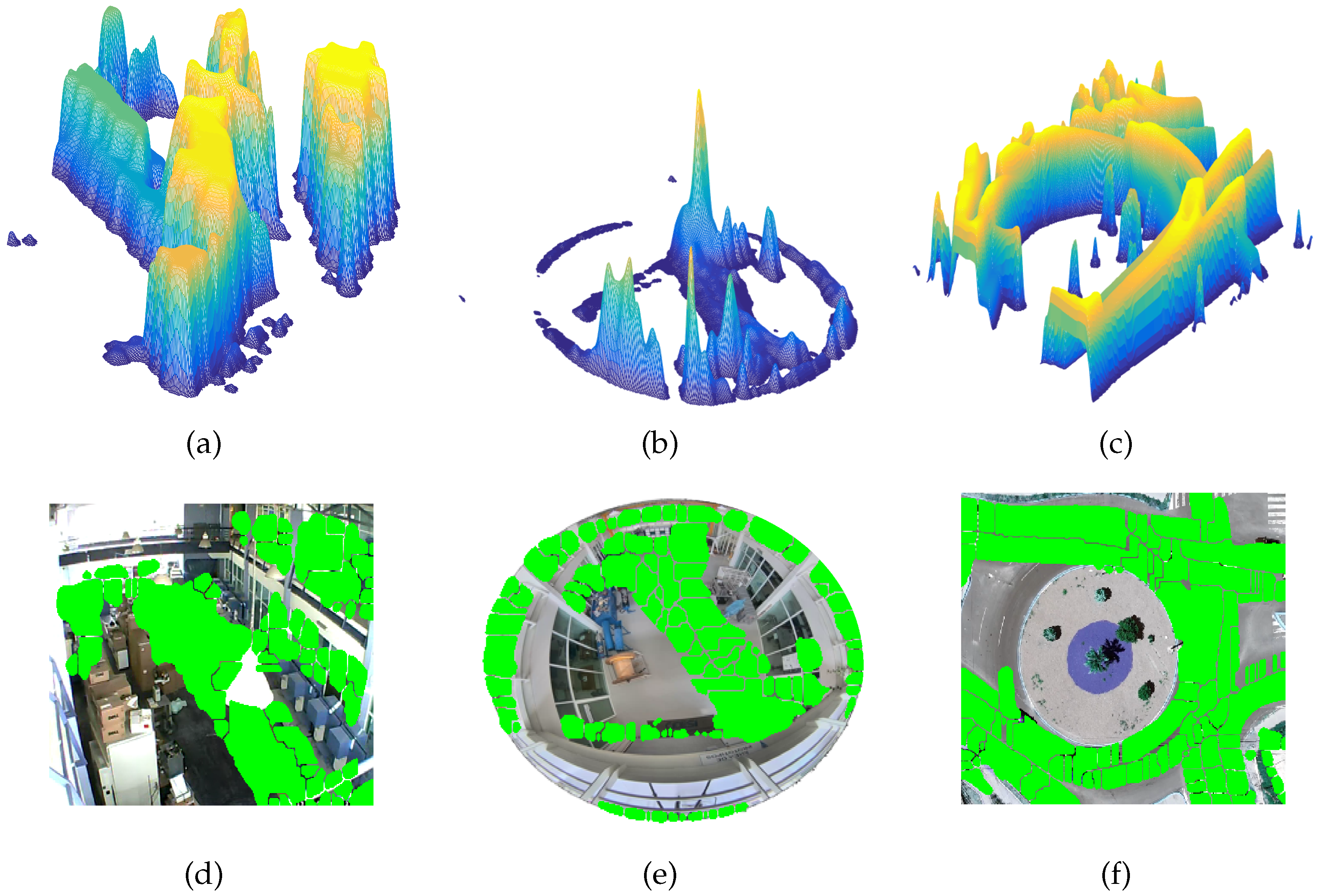

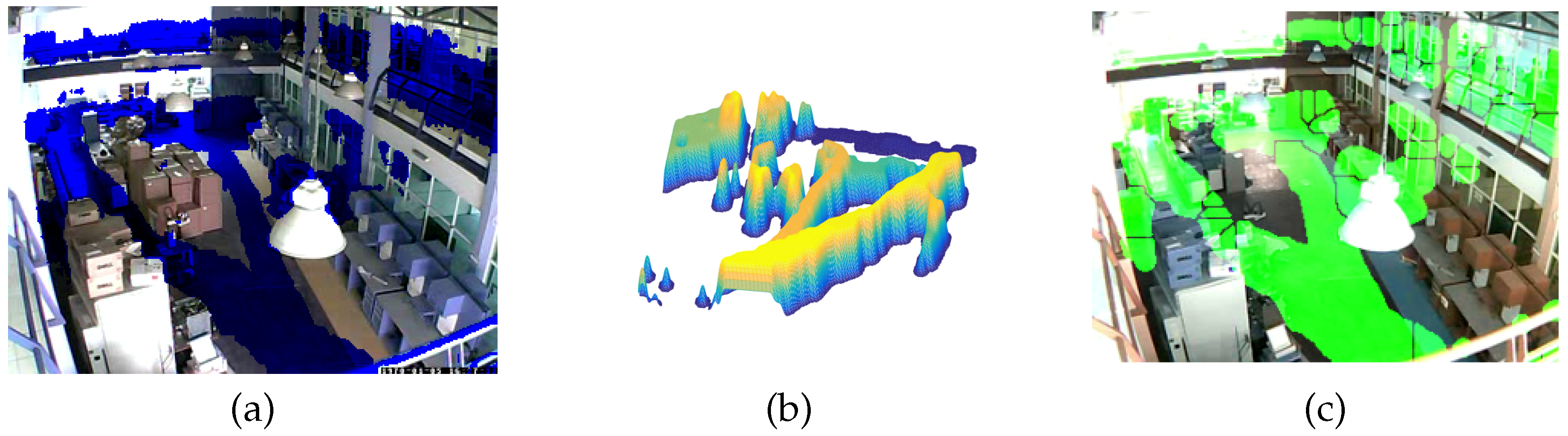

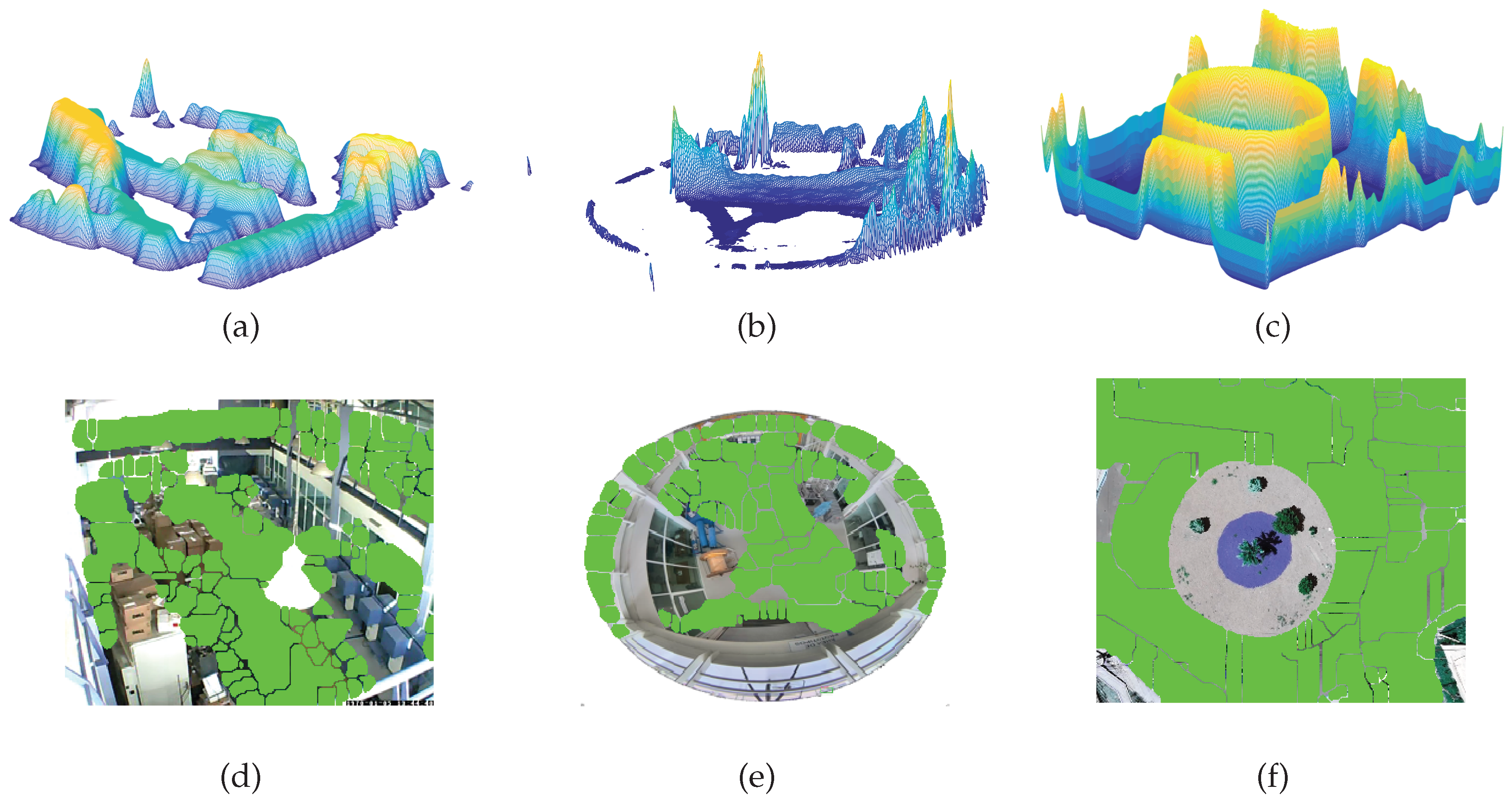

- Movement states definition. With the information on the movement of objects contained in , it is necessary to understand the dynamics of the objects in the scene over time. This temporal representation is achieved by the function , which relates the movement information of the trajectories to the membership of each pixel in the movement. By analyzing the belonging to the movement using , an accumulated surface is formed that contains the integrated information of the movement patterns. By applying the algorithm to , a two-dimensional representation of the regions with the highest probability of belonging to the movement is obtained, which are defined in the set of states E.

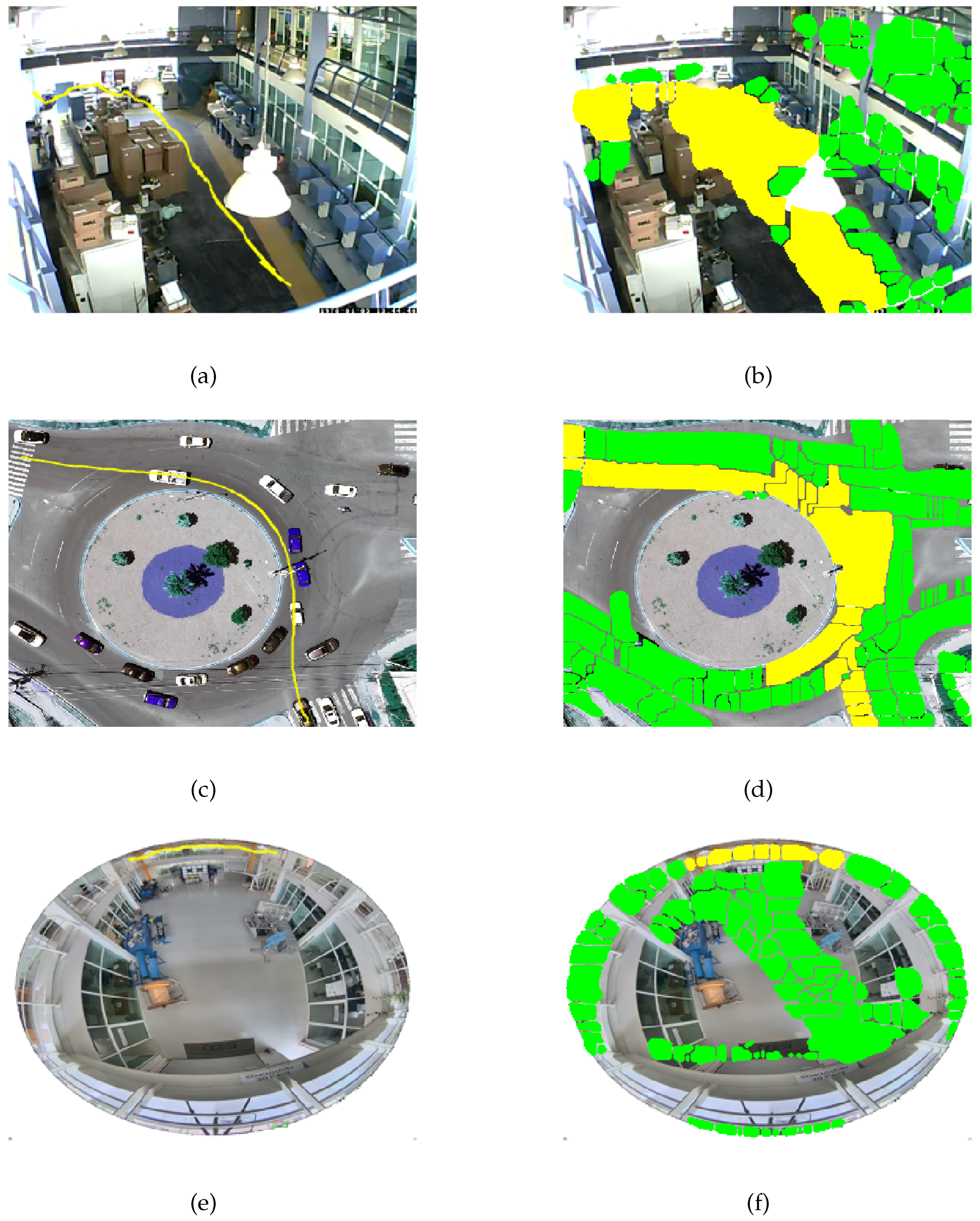

- 3.

- Symbol strings. At this stage, once the states E have been defined, the state mask is constructed, which relates each state to a symbol . The relationship between the movement positions and the states forms the state trajectories . Applying yields the symbolic sequences .

- 4.

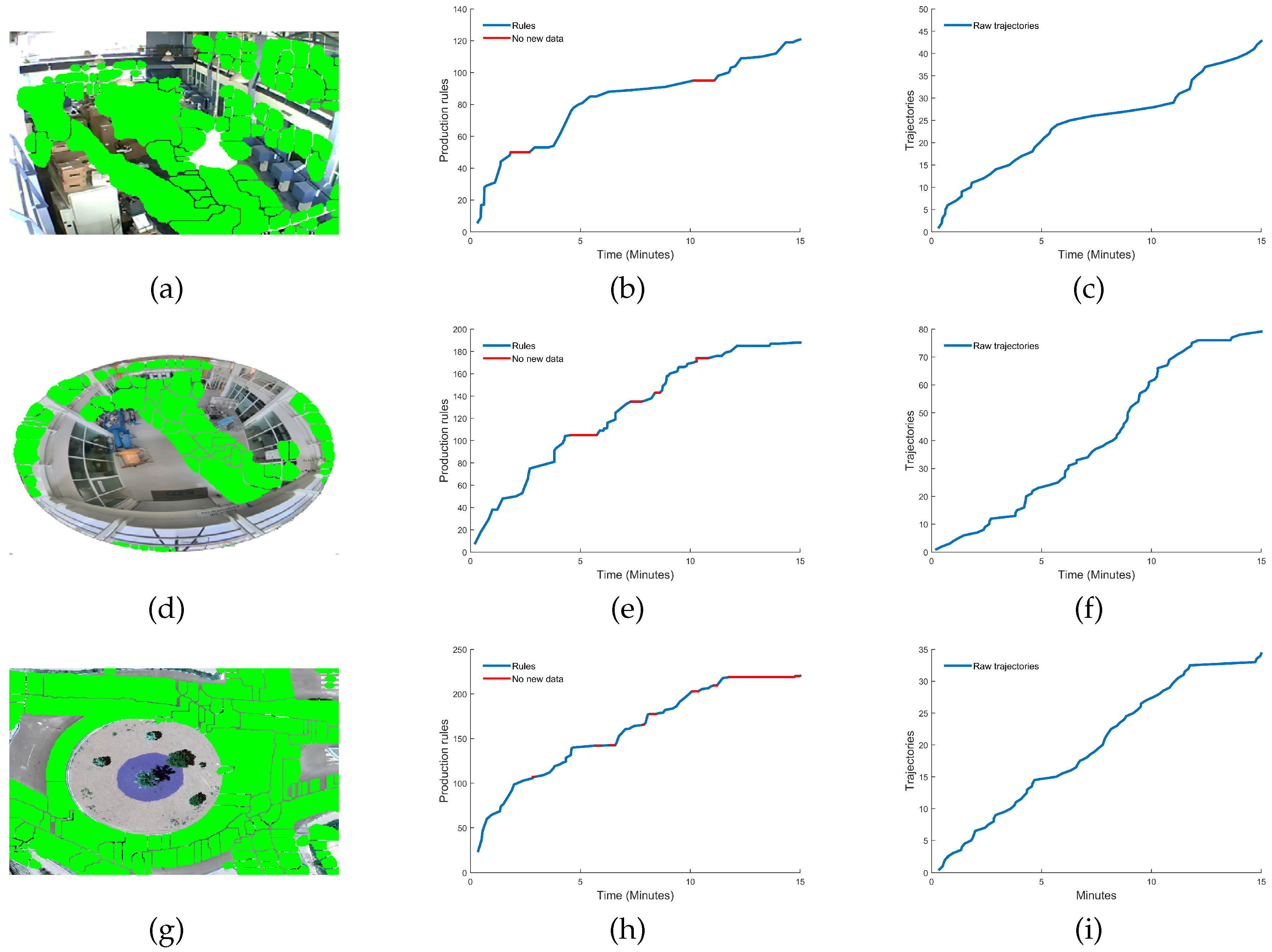

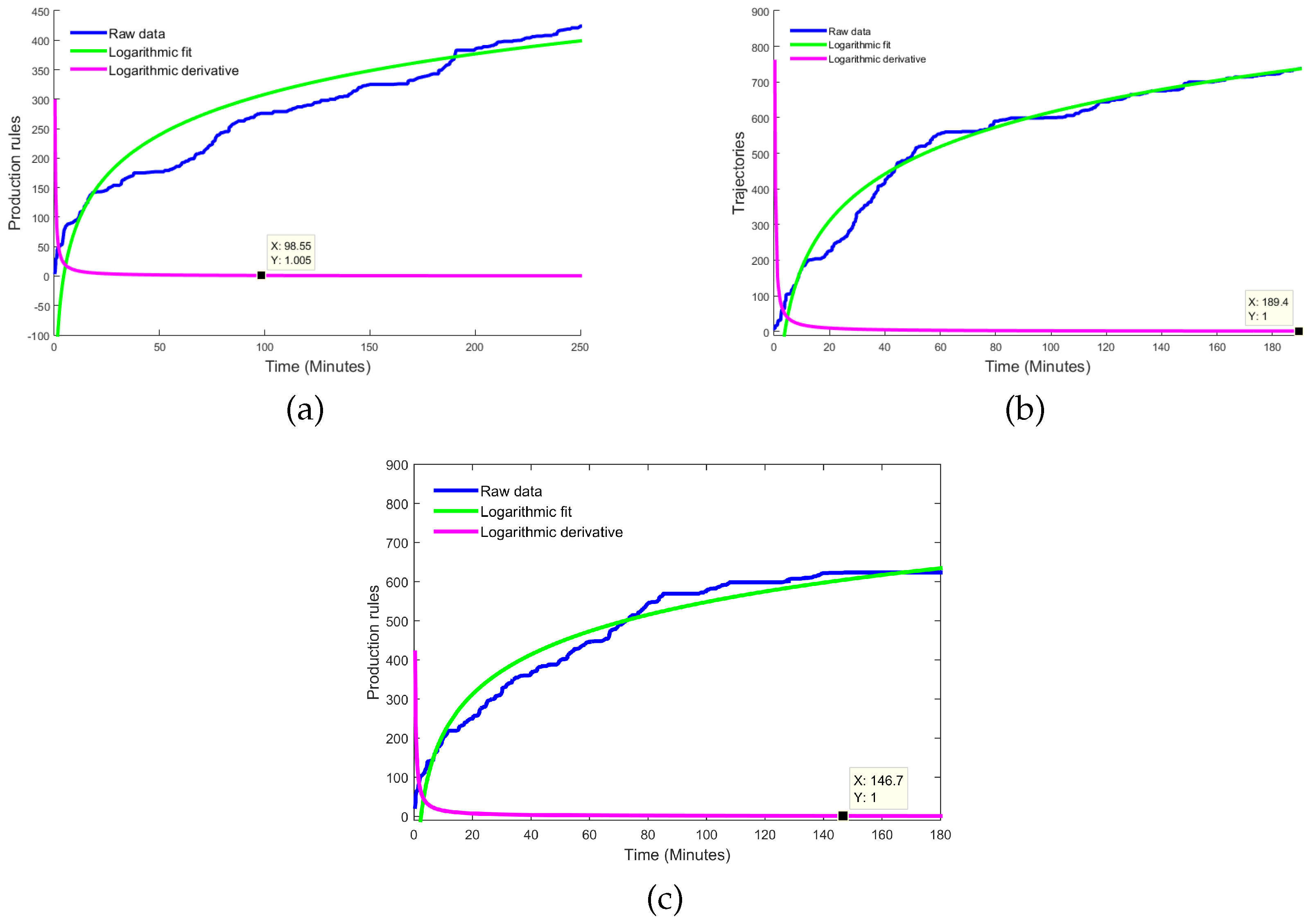

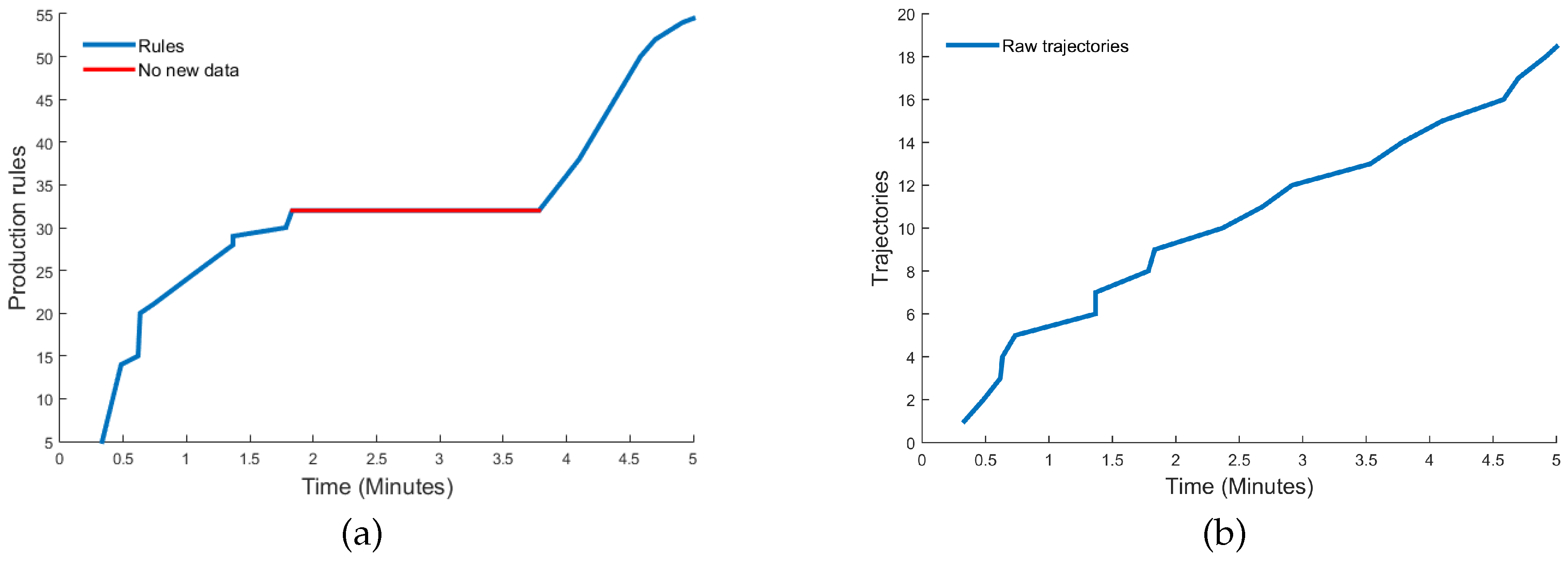

- Sufficiency of information. The movement sequences are used to infer grammars by means of . This process generates a dictionary of production rules , where the change in the cardinality of the set of production rules is taken as a reference to define the criterion to define when the system has learned enough, shows the increase in the number of rules. Naturally, when analyzing the change in , we see that when meets the condition , this means that , therefore, no new production rule is being generated in the dictionary. This characteristic of the behavior of the function is a clear indication that a point of sufficiency of acquired information is being reached.

- 5.

- Dynamics modeling. Once sufficient information has been defined to model the scene, activities are detected by applying SEQUITUR to the movement sequences obtained.

4.2. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Further Works

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| HMM | Hidden Markov Models |

| KNN | K-nearest neighbors |

| PTZ | Pan, Tilt, and Zoom |

References

- Fedorov, A.; Nikolskaia, K.; Ivanov, S.; Shepelev, V.; Minbaleev, A. Traffic flow estimation with data from a video surveillance camera. Journal of Big Data 2019, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elharrouss, O.; Almaadeed, N.; Al-Maadeed, S. A review of video surveillance systems. Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation 2021, 77, 103116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ess, A.; Leibe, B.; Schindler, K.; Van Gool, L. A mobile vision system for robust multi-person tracking. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. IEEE, 2008, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Mabrouk, A.B.; Zagrouba, E. Abnormal behavior recognition for intelligent video surveillance systems: A review. Expert Systems with Applications 2018, 91, 480–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultani, W.; Chen, C.; Shah, M. Real-world anomaly detection in surveillance videos. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 6479–6488. [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, M.E.; Ashari, A.; Putra, M.P.K.; et al. Improvement of Deep Learning-based Human Detection using Dynamic Thresholding for Intelligent Surveillance System. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenu, G.; Durai, S. Intelligent video surveillance: a review through deep learning techniques for crowd analysis. Journal of Big Data 2019, 6, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luck, S.J.; Stewart, A.X.; Simmons, A.M.; Rhemtulla, M. Standardized measurement error: A universal metric of data quality for averaged event-related potentials. Psychophysiology 2021, 58, e13793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, Y.; Heo, G.; Whang, S.E. A survey on data collection for machine learning: a big data-ai integration perspective. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2019, 33, 1328–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijali, A. Analisis data kualitatif. Alhadharah: Jurnal Ilmu Dakwah 2018, 17, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denes, G.; Jindal, A.; Mikhailiuk, A.; Mantiuk, R.K. A perceptual model of motion quality for rendering with adaptive refresh-rate and resolution. ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG) 2020, 39, 133:1–133:17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wei, X.; Hong, X.; Shi, W.; Gong, Y. Multi-target multi-camera tracking by tracklet-to-target assignment. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2020, 29, 5191–5205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilroy, S.; Jones, E.; Glavin, M. Overcoming occlusion in the automotive environment—A review. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2019, 22, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Sun, Y.; Kortylewski, A.; Yuille, A.L. Robust object detection under occlusion with context-aware compositionalnets. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020, pp. 12645–12654. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, G.; Li, G.; Yu, Y. Motion guided attention for video salient object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2019, pp. 7274–7283. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Newsam, S. Motion-aware feature for improved video anomaly detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.10211 2019. [CrossRef]

- Griffin, B.A.; Corso, J.J. Depth from camera motion and object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2021, pp. 1397–1406. [CrossRef]

- Jain, J.; Singh, A.; Orlov, N.; Huang, Z.; Li, J.; Walton, S.; Shi, H. Semask: Semantically masked transformers for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 752–761. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.W.; Hua, Z.X.; Li, H.C.; Zhong, H.Y. Flying Bird Object Detection Algorithm in Surveillance Video Based on Motion Information. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2024, 73, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Zhao, C.; Pan, X.; Basu, A. Learning Temporal Distribution and Spatial Correlation Toward Universal Moving Object Segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2024, 33, 2447–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Huang, B.; Wang, Y. Object-occluded human shape and pose estimation from a single color image. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020, pp. 7376–7385. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Li, Y.; Lin, J.; Li, H.; Wu, F. Deep learning-based video coding: A review and a case study. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2020, 53, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.N.; Nguyen, M.H.; Pham, C. Masked face recognition with convolutional neural networks and local binary patterns. Applied Intelligence 2022, 52, 5497–5512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinhardt, T.; Kirillov, A.; Leal-Taixe, L.; Feichtenhofer, C. Trackformer: Multi-object tracking with transformers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022, pp. 8844–8854. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Yadav, J.S. Video object extraction and its tracking using background subtraction in complex environments. Perspectives in Science 2016, 8, 317–322, Recent Trends in Engineering and Material Sciences. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Jain, P.; Patel, P. Video Background Subtraction Algorithms for Object Tracking. In Proceedings of the 2022 Third International Conference on Intelligent Computing Instrumentation and Control Technologies (ICICICT), 2022, pp. 464–469. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Williams, B.M.; Vallabhaneni, S.R.; Czanner, G.; Williams, R.; Zheng, Y. Learning active contour models for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019, pp. 11632–11640. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhou, T.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Yang, Y. Deep hierarchical semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp. 1246–1257. [CrossRef]

- Tao, A.; Sapra, K.; Catanzaro, B. Hierarchical multi-scale attention for semantic segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.10821 2020. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wang, Q.; Jian, M.; Zhao, Y.Q.B. A Comprehensive Review of Group Activity Recognition in Videos. International Journal of Automation and Computing 2021, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Yilmaz, O.J.; Shah, M. Object tracking: a Survey. ACM Computing surveys 2006, 38, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daldoss, M.; Piotto, N.; Conci, N.; De Natale, F.G. Learning and matching human activities using regular expressions. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing. IEEE, 2010, pp. 4681–4684. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wu, M. Pattern recognition receptors in health and diseases. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2021, 6, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga-Neto, U. Fundamentals of pattern recognition and machine learning; Springer, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, T.; Maupong, T.; Mpoeleng, D.; Semong, T.; Mphago, B.; Tabona, O. A survey on missing data in machine learning. Journal of Big data 2021, 8, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, M.W.; Müller-Hansen, F. Statistical stopping criteria for automated screening in systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews 2020, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevill-Manning, C.G.; Witten, I.H. Identifying hierarchical structure in sequences: A linear-time algorithm. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 1997, 7, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitarai, S.; Hirao, M.; Matsumoto, T.; Shinohara, A.; Takeda, M.; Arikawa, S. Compressed pattern matching for SEQUITUR. In Proceedings of the Proceedings DCC 2001. Data Compression Conference. IEEE, 2001, pp. 469–478. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Sekh.; D.P. Dogra.; S. Kar.; P.P. Roy. Video trajectory analysis using unsupervised clustering and multi-criteria ranking. Soft Computing 2020, 24, 16643–16654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Sastry, P.S. Abnormal activity detection in video sequences using learnt probability densities. In Proceedings of the TENCON 2003. Conference on Convergent Technologies for Asia-Pacific Region, 2003, Vol. 1, pp. 369–372 Vol.1. [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Wu, E.Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Law, R.; Lin, Y. FlightBERT: binary encoding representation for flight trajectory prediction. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2022, 24, 1828–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Wang, Y.; Yu, G.; Wu, X. A lane-change trajectory model from drivers’ vision view. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2017, 85, 609–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamba, P.; Mecocci, A. Perceptual grouping for symbol chain tracking in digitized topographic maps. Pattern Recognition Letters 1999, 20, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Huerta, J.M.; Jiménez-Hernández, H.; Herrera-Navarro, A.M.; Hernández-Díaz, T.; Terol-Villalobos, I. Modelling dynamics with context-free grammars. Video Surveill. Transp. Imaging Appl. 2014 2014, 9026, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosani, A.; Conci, N.; Natale, F.G.D. Human behavior recognition using a context-free grammar. Journal of Electronic Imaging 2014, 23, 033016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugo, J.H.; Jose-Joel, G.B.; Teresa, G.R. Detecting abnormal vehicular dynamics at intersections based on an unsupervised learning approach and a stochastic model. Sensors 2010, 10, 7576–7601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, M. A watershed-segmentation-based improved algorithm for extracting cultivated land boundaries. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tang, Z.; Xie, Y.; Gao, X.; Chen, Q. A watershed segmentation algorithm based on an optimal marker for bubble size measurement. Measurement 2019, 138, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venu, D.; Kumar, A.A. Comparison of Traditional Method with watershed threshold segmentation Technique. The International journal of analytical and experimental modal analysis 2021, 13, 181–187. [Google Scholar]

- de la Higuera, C. Grammatical inference: learning automata and grammars. In Proceedings of the Cambridge University Press, 2010, pp. 1–502. [CrossRef]

- Nevill-Manning, C.G.; Witten, I.H. Compression and Explanation using Hierarchical Grammars. The Computer Journal 1997, 40, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åke Björck. Least Square Method; Vol. 1, Handbook of Numerical Analysis, Elsevier, 1990; pp. 465–652. [CrossRef]

- Gomila, R. Logistic or linear? Estimating causal effects of experimental treatments on binary outcomes using regression analysis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 2021, 150, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björck, Å. Numerical methods for least squares problems; SIAM, 2024. [CrossRef]

| Author | Motion Coding | State Definition | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andrea Rosani et al. [45] | Hot spots | Empirical approach | The approach focuses on activity recognition for behavioral analysis in known scenarios using context-free grammars. By incorporating both positive and negative sampling, this method enhances discrimination capabilities during the retraining process, enabling better adaptation to environmental changes. |

| Garcia-Huerta et al. [44] | Labeled regions | Manual | The study focuses on detecting abnormal visual events within a scenario. Motion detection is achieved through temporal differences, applied as a decay function, which identifies motion zones. These zones are subsequently segmented using the Watershed transform. |

| Waqas Sultani et al. [5] | Labeled regions | Fixed number | This work proposes an anomaly detection model based on deep multiple instance learning. The model utilizes a fixed number of segments from both anomalous and normal surveillance videos. |

| M. Daldoss et al. [32] | Hot spots | Automatic | Introduces a method for analyzing trajectories by tracking objects through a two-view camera system in surveillance videos using automatically learned context-free grammars. The model is trained on a set of sequences that define rules for different behaviors. |

| Hernandez-Ramirez et al. (proposed) | Labeled regions | Automatic | This work introduces an approach centered on information sufficiency, where symbolic trajectories from object–labeled region interactions are used to infer grammars. The sufficiency criterion, defined by the stabilization of production rules, ensures a meaningful representation of scene dynamics. |

| Input | String | Grammar | Rules |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | |||

| b |

|

||

| d | |||

| a | |||

| b |

|

||

| c |

|

| Scenarios | Training time | Total trajectories | Dictionary rules | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) PTZ Camera | 98.55 minutes | 440 | 250 | 84.13 % |

| (2) Fisheye 360° Camera | 189.4 minutes | 1022 | 700 | 83.56 % |

| (3) Wide angle Camera | 146.7 minutes | 319 | 622 | 95.92 % |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).