1. Introduction

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) is a severe inflammatory disease of the lungs that can follow serious conditions like pneumonia, sepsis, or physical trauma. This inflammation leads to damaged lung tissue, causing blood and fluid to leak into the airspaces, resulting in a critical lack of oxygen in the bloodstream [

1]. According to the Berlin definition, ARDS is diagnosed by an acute onset within one week, bilateral opacities on chest radiography or computed tomography consistent with pulmonary edema, a PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio of ≤300 mmHg with a minimum positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) or continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) of ≥5 cmH₂O, and the absence of evidence for left atrial hypertension or fluid overload [

2].

A patient with ARDS experiencing respiratory failure in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) required mechanical ventilation to facilitate high-concentration oxygen delivery and adequate carbon dioxide exchange [

1]. Intubation, a key part of this procedure, can lead to several adverse outcomes with prolonged use, such as elevated mortality rates, an increased incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), complications during the weaning process, and an extended length of stay (LOS) in the ICU [

3].

To minimize these risks, percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy (PDT) is a viable procedural option. PDT is considered easier and safer to perform than surgical tracheostomy (ST) in the ICU setting [

4]. Early PDT is a procedure typically performed within the first ten days of intubation [

5]. While there is no universally accepted guideline for the optimal timing of this procedure, one study indicates that tracheostomies performed after the 14th day of intubation are associated with a prolonged hospital stay [

6].

Clinicians must carefully weigh the benefits, risks, and optimal timing of PDT to ensure favorable patient outcomes and safety. This case report aims to describe the successful application of early PDT as a measure to mitigate the risks of VAP, prolonged mechanical ventilation, and mortality.

2. Case Presentation

A 61-year-old male, 51 kg, was admitted to the emergency department with a diagnosis of ARDS due to sepsis ec. community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), and Type I respiratory failure. He presented with continuous dyspnea and productive cough since morning. His past medical history revealed a long-term active smoking.

On physical examination, the patient was conscious with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 15. Vital signs were as follows: heart rate of 110 bpm, blood pressure of 141/89 mmHg, respiratory rate of 28 bpm, and SpO₂ of 92% on a 15 L/min non-rebreather mask. His temperature was 37.5 °C. Lung auscultation revealed bilateral rhonchi with no wheezing. This clinical presentation was corroborated by a chest radiograph, which showed a parapneumonic pattern.

Table 1.

Initial diagnostic test results.

Table 1.

Initial diagnostic test results.

| Laboratorium |

Value |

Laboratorium |

Value |

| Hb |

17,1 g/dL |

AGD: |

|

| Leukocyte |

20.540 μL |

pH |

7,5 |

Platelet

Hematocryte

Ureum serum

Creatinin serum

Na serum

K serum

Cl serum

Lactat acid |

250.000 μL

49,6%

125,9 mg/dL

1,32 mg/dL

138,8 mg/dL

3,04 meq/L

87,7 meq/L

0,7 meq/L |

PCO2

PO2

BE

TCO2

HCO3

Sat O2

P/F ratio |

27,3 mmHg

67 mmHg

0,7

22,5

21,6 meq/L

95%

67 (severe)

|

Due to progressively worsening dyspnea and a decline in oxygen saturation to 88% on a 15 L/min non-rebreather mask, he was immediately intubated and placed on mechanical ventilation. Initial ventilator settings included a Pressure Synchronized Intermittent Mandatory Ventilation (P-SIMV) mode with: FiO₂ of 70%, inspiratory pressure of 14 cmH₂O, pressure support of 14 cmH₂O, respiratory rate of 14 bpm, and a positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 7 cmH₂O. The I:E ratio was set at 1:1.87, with a target tidal volume (VT) of 350 mL, a respiratory rate of < 32 bpm, and a peak inspiratory pressure (Ppeak) of 18 cmH₂O.

A sputum culture was obtained, and he was initiated on a regimen of intravenous meropenem 1 g every 8 hours and moxifloxacin 400 mg every 24 hours. Sedation with intravenous dexmedetomidine (0.4 mcg/kg/hr) was also initiated. The patient was then transferred to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for further management, which included nebulization, intermittent suctioning, and chest physiotherapy.

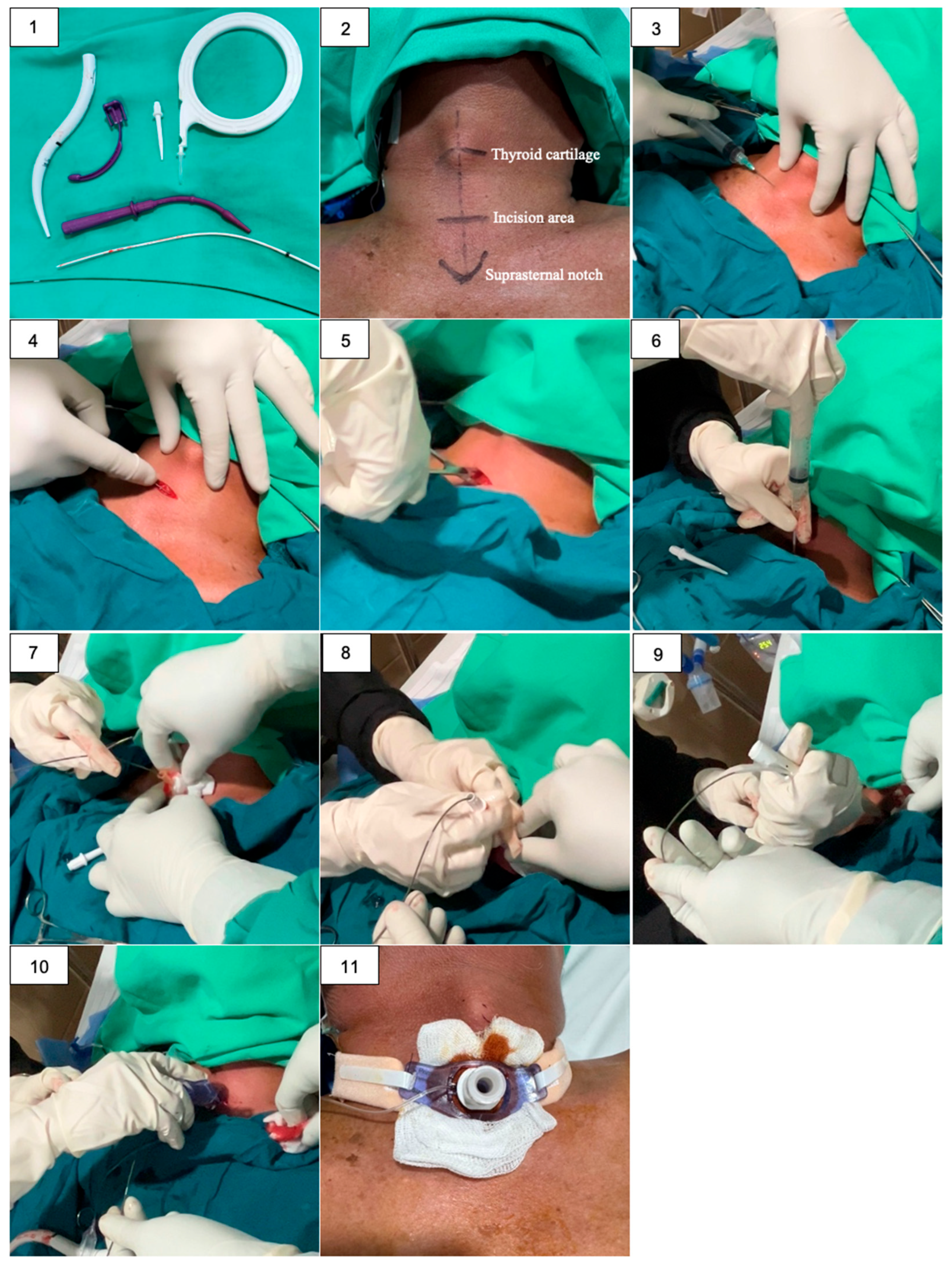

After a four-day evaluation on mechanical ventilation, the patient was scheduled for an early PDT in the ICU. He was positioned supine with neck extension. Anesthesia was induced with intravenous fentanyl 100 mcg, ketamine 50 mg for sedation, and the muscle relaxant rocuronium 50 mg to suppress the cough reflex and ensure adequate respiratory control throughout the procedure.

Figure 1.

A bedside PDT procedure in ICU: (1) All necessary instruments are prepared and arranged; (2) The appropriate anatomical landmarks are identified and marked; (3) Sterile field and local anesthesia with Lidocain 2% intracutaneous; (4) A 1-cm vertical incision is made two finger-breadths below the thyroid notch; (5) Blunt dissection is performed to expose the trachea; (6) The trachea is punctured with a needle, and the syringe is aspirated to confirm positive air return; (7) Guidewire is inserted into the trachea through the needle; (8) A small dilator is used to widen the stoma over the guidewire; (9) A larger dilator is used to expand the stoma to the appropriate size for the tracheostomy tube; (10) The tracheostomy tube is inserted into the dilated stoma; (11) The tracheostomy tube is secured with ties or sutures.

Figure 1.

A bedside PDT procedure in ICU: (1) All necessary instruments are prepared and arranged; (2) The appropriate anatomical landmarks are identified and marked; (3) Sterile field and local anesthesia with Lidocain 2% intracutaneous; (4) A 1-cm vertical incision is made two finger-breadths below the thyroid notch; (5) Blunt dissection is performed to expose the trachea; (6) The trachea is punctured with a needle, and the syringe is aspirated to confirm positive air return; (7) Guidewire is inserted into the trachea through the needle; (8) A small dilator is used to widen the stoma over the guidewire; (9) A larger dilator is used to expand the stoma to the appropriate size for the tracheostomy tube; (10) The tracheostomy tube is inserted into the dilated stoma; (11) The tracheostomy tube is secured with ties or sutures.

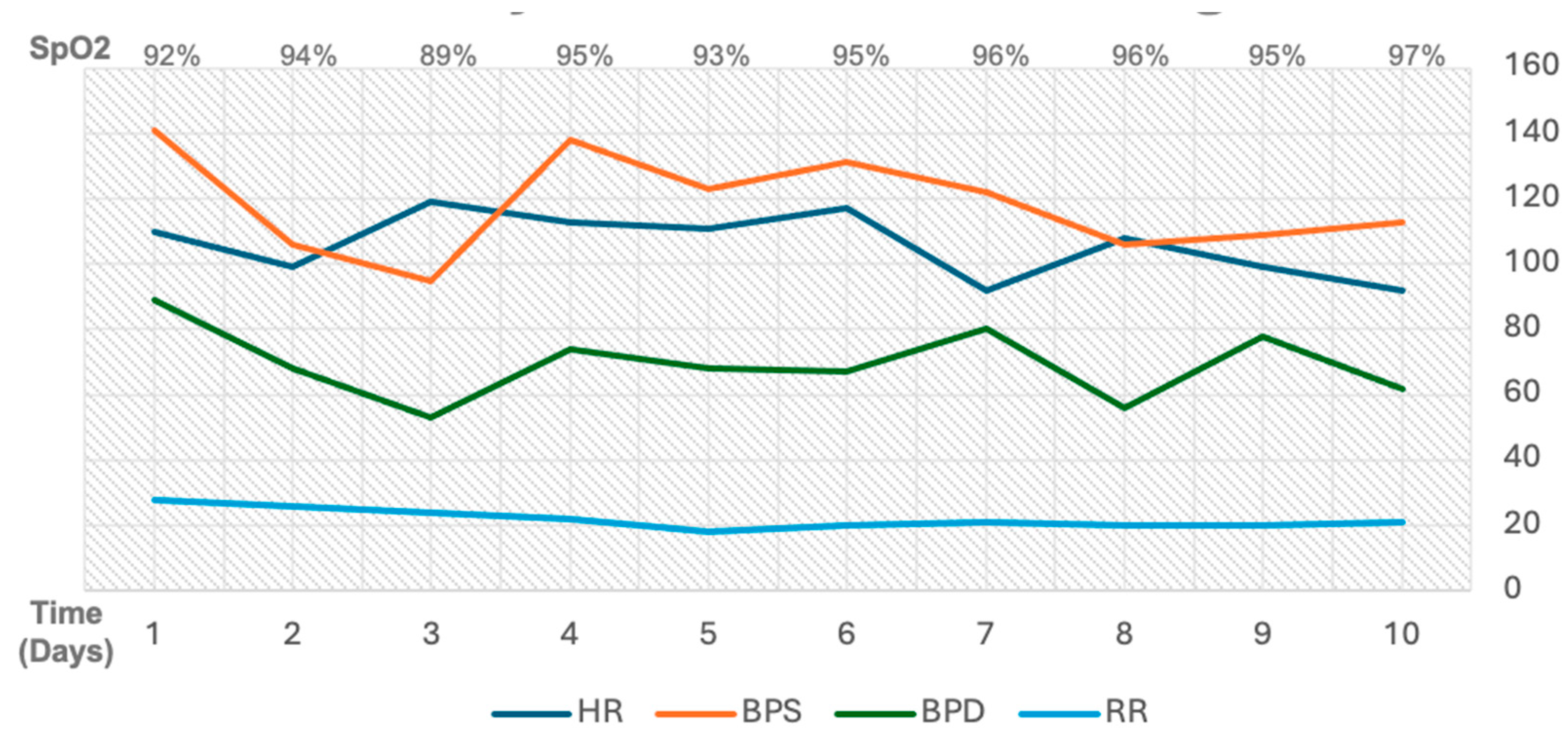

Figure 2.

Daily hemodynamics monitoring throughout admission stay in ICU.

Figure 2.

Daily hemodynamics monitoring throughout admission stay in ICU.

Following the PDT procedure, the patient’s condition progressively improved, leading to successful ventilator weaning. His oxygen fraction requirement decreased, and his overall general condition improved. By day 7, he was able to breathe spontaneously via a T-piece at 2 L/min. By day 8, sputum culture results identified the presence of Streptococcus pneumoniae, which demonstrated sensitivity to both meropenem and moxifloxacin. The initial empiric antibiotic regimen was consistent with these findings and was continued as the definitive treatment. Over the next two days, he was successfully weaned from all supplemental oxygen. After a total of 10 days in the ICU, he was transferred to the general ward in stable condition.

Table 2.

The patient clinical progress evaluation throughout admission stay in ICU.

3. Discussion

Most patients with ARDS and respiratory failure require mechanical ventilation for support, often via intubation [

1]. The patient in this case presented with severe ARDS due to sepsis ec. CAP, and Type I respiratory failure. The decision to perform an early PDT on day 4 of care was based on several factors. The patient had failed a ventilator weaning trial on day 3, with a persistent SpO₂ of 89% on an FiO₂ of 70%, indicated that spontaneous breathing trial (SBT) readiness criteria were not achieved. Furthermore, the patient’s severe ARDS status (PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio of 67) according to the Berlin criteria, and concurrent sepsis suggested a heightened risk for both prolonged ventilation and subsequent VAP.

Due to the risks associated with long-term intubation, tracheotomy is often recommended for patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation for pulmonary insufficiency. This procedure offers several advantages over an endotracheal tube, including improved patient comfort and mobility, a reduced need for sedation, and a decreased risk of oral lesions [

7]. Additionally, a tracheotomy reduces resistance to airflow and facilitates more effective secretion removal, better oral hygiene, and improved pulmonary toilet, all of which may help mitigate the risk of VAP [

8].

Early tracheostomy provides several clinical and economic benefits compared to prolonged endotracheal intubation or late tracheostomy. These advantages include a reduced incidence of VAP, duration of mechanical ventilation, a shorter LOS in the ICU, and a decrease in overall hospital costs [

9]. A study conducted in Italy investigated the outcomes of early tracheostomy with the procedure performed by day 4 of care. It found that patients who underwent early tracheostomy (74%) had a significantly lower hospital mortality rate (45.5%) compared to those who did not (62.8%) [

5]. However, a separate meta-analysis suggested that while tracheostomy performed within 10 days of translaryngeal intubation in critically ill patients may reduce the duration of sedation, early tracheostomy did not show a significant reduction in mortality, incidence of VAP, or length of ICU stay when compared to late tracheostomy [

10].

The PDT technique was chosen for this patient because it could be performed at the bedside in the ICU, thus minimizing the risks of patient transport. This decision was further supported by the patient’s suitable neck anatomy, the availability of the necessary equipment, and an experienced intensivist to perform the procedure. A previous retrospective study indicates that PDT is a safer procedure than ST when performed in the ICU. The lower incidence of post-operative complications following PDT may be attributed to the minimal skin incision required for the procedure. Furthermore, when performed by trained intensivists at the bedside, PDT has been shown to be a relatively safe intervention, with some reports citing a complication rate as low as 3.8% [

4]. Another study has also shown that PDT is associated with a reduced risk of complications such as surgical site infection, major bleeding, stoma enlargement, tracheal tube dislodgement, and death [

11].

There is currently no single recommended standard for tracheostomy; both PDT and ST are widely used and accepted techniques. ST is particularly indicated in patients with challenging anatomical features, such as morbid obesity, a short neck, or a history of thyroid hypertrophy. Conversely, the PDT procedure can be considered for patients with favorable anatomy, offering a more cost-effective alternative to ST. Despite its advantages, a key limitation of PDT is its operator-dependent nature, requiring a highly experienced operator for safe and successful execution [

4,

12].

The patient’s clinical status significantly improved after undergoing early PDT. This was evidenced by an improved P/F ratio, successful ventilator weaning, and the patient’s ability to breathe spontaneously without a ventilator by day 7. Additionally, chest X-ray evaluations demonstrated a favorable clinical course. A sputum culture on day 8 identified the presence of

Streptococcus pneumoniae. This is consistent with the established etiology of CAP, where

S. pneumoniae is the most prevalent causative agent [

13,

14]. This aligns with other studies that have found

S. pneumoniae to be a predominant cause (19%), followed by

Mycoplasma pneumoniae (15.4%), and

Klebsiella pneumoniae (10.5%) [

15].

Unlike the CAP presented in this case, the major complication of prolonged mechanical ventilation is VAP. The specific organisms causing VAP vary based on several factors, including the duration of mechanical ventilation, length of hospital and ICU stays before the infection develops, prior antimicrobial exposure, and the local microbial environment. The most common pathogens associated with VAP are Gram-negative microorganisms such as

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and

Acinetobacter species, along with the Gram-positive microorganism

Staphylococcus aureus [

16,

17].

Beyond VAP, prolonged mechanical ventilation can lead to a variety of other severe complications, often appearing after 48 hours. These include septic shock, hemodynamic instability, ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) such as barotrauma, splanchnic hypoperfusion, and electrolyte imbalances such as hypoalbuminemia, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, and hypocalcemia [

18,

19,

20]. Furthermore, prolonged mechanical ventilation can lead to respiratory muscle weakness, diaphragmatic atrophy, and tracheal injuries like stenosis, all of which complicate the weaning process and can contribute to ICU-acquired weakness (ICU-AW) [

21,

22].

The patient’s stable condition over the next 2 days allowed for a transfer to the general ward. This positive outcome highlights the procedure’s efficacy in mitigating the risks and complications associated with prolonged mechanical ventilation, as well as reducing patient mortality.

4. Conclusions

This case report demonstrates the successful implementation of early PDT in a patient with severe ARDS due to community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)-induced sepsis and type I respiratory failure. The PDT intervention was effective in preventing prolonged mechanical ventilation and its associated complications. Nevertheless, other critical factors, including a lung-protective ventilation strategy, targeted antibiotic therapy guided by culture results, and comprehensive supportive care, also significantly contributed to the positive patient outcome.

It is important to acknowledge that the generalizability of a single case report is inherently limited. Further research involving a larger patient cohort is necessary to identify the optimal response to early PDT and to determine the most precise and appropriate timing for this intervention.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the retrospective nature of the case report and the de-identification of all patient information.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the subject involved in the study. A signed statement confirming consent to publish has been obtained from the patient.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.study. A signed statement confirming consent to publish has been obtained from the patient.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- ARDSNet. ARDS Network. Available online: http://www.ardsnet.org/index.shtml (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Matthay, M.A.; Arabi, Y.; Arroliga, A.C.; Bernard, G.; Bersten, A.D.; Brochard, L.J.; Calfee, C.S.; Combes, A.; Daniel, B.M.; Ferguson, N.D.; Gong, M.N.; Gotts, J.E.; Herridge, M.S.; Laffey, J.G.; Liu, K.D.; Machado, F.R.; Martin, T.R.; McAuley, D.F.; Mercat, A.; Moss, M.; Mularski, R.A.; Pesenti, A.; Qiu, H.; Ramakrishnan, N.; Ranieri, V.M.; Riviello, E.D.; Rubin, E.; Slutsky, A.S.; Thompson, B.T.; Twagirumugabe, T.; Ware, L.B.; Wick, K.D. A New Global Definition of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 209, 37–47.

- Wu, C.; Chen, X.; Cai, Y.; Xia, J.; Zhou, X.; Xu, S.; Huang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, X.; Du, C.; Zhang, Y.; Song, J.; Wang, S.; Chao, Y.; Yang, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhou, X.; Chen, D.; Xiong, W.; Xu, L.; Zhou, F.; Jiang, J.; Bai, C.; Zheng, J.; Song, Y. Risk Factors Associated With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Death in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 1-11.

- Suzuki, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Teshigawara, A.; Okuda, J.; Suhara, T.; Ueda, T.; Nagata, H.; Yamada, T.; Morisaki, H. Evaluation of the Safety of Percutaneous Dilational Tracheostomy Compared with Surgical Tracheostomy in the Intensive Care Unit. Crit. Care Res. Pract. 2019, 2019, 2054846.

- Rosano, A.; Martinelli, E.; Fusina, F.; Albani, F.; Caserta, R.; Morandi, A.; Dell’Agnolo, P.; Dicembrini, A.; Mansouri, L.; Marchini, A.; Schivalocchi, V.; Natalini, G. Early Percutaneous Tracheostomy in Coronavirus Disease 2019: Association With Hospital Mortality and Factors Associated With Removal of Tracheostomy Tube at ICU Discharge. A Cohort Study on 121 Patients. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 49, 261-270.

- Tekin, P.; Bulut, A. Tracheostomy Timing in Unselected Critically Ill Patients with Prolonged Intubation: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2729.

- Dochi, H.; Nojima, M.; Matsumura, M.; et al. Effect of early tracheostomy in mechanically ventilated patients. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2019, 4, 292–299.

- Marzban-Rad, S.; Aghamohammadzadeh, A.; Rastegar, L.; Alijani, M. Early percutaneous dilational tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients: A case report. Clin. Case Rep. 2021, 9, 1014-1017.

- Ananda, P.A.; Sony. Early Tracheostomy in Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation Due to Severe Head Injury to Prevent Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia (VAP). IJAR 2022, 4, 115-119.

- Meng, L.; Wang, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, J. Early vs late tracheostomy in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Respir. J. 2016, 10, 684–692.

- Johnson-Obaseki, S.; Veljkovic, A.; Javidnia, H. Complication rates of open surgical versus percutaneous tracheostomy in critically ill patients. Laryngoscope 2016, 126, 2459-2467.

- Mehta, C.; Mehta, Y. Percutaneous tracheostomy. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2017, 20, S19–S25.

- Lin, W. H.; Chiu, H. C.; Chen, K. F.; Tsao, K. C.; Chen, Y. Y.; Li, T. H.; Huang, Y. C.; Hsieh, Y. C. Molecular detection of respiratory pathogens in community-acquired pneumonia involving adults. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2022, 55, 829-837.

- Cilloniz, C.; Ferrer, M.; Liapikou, A.; Garcia-Vidal, C.; Gabarrus, A.; Ceccato, A.; Puig de La Bellacasa, J.; Blasi, F.; Torres, A. Acute respiratory distress syndrome in mechanically ventilated patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 51, 1702215.

- Ghia, C.J.; Dhar, R.; Koul, P.A.; Rambhad, G.; Fletcher, M.A. Streptococcus pneumoniae as a Cause of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Indian Adolescents and Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Med. Insights Circ. Respir. Pulm. Med. 2019, 13, 1179548419862790.

- Papazian, L.; Klompas, M.; Luyt, C.E. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults: a narrative review. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 888-906.

- Luyt, C.E.; Hekimian, G.; Koulenti, D.; Chastre, J. Microbial cause of ICU-acquired pneumonia: hospital-acquired pneumonia versus ventilator-associated pneumonia. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2018, 24, 332–338.

- Udi, J.; Lang, C.N.; Zotzmann, V.; Krueger, K.; Fluegler, A.; Bamberg, F.; Bode, C.; Duerschmied, D.; Wengenmayer, T.; Staudacher, D.L. Incidence of Barotrauma in Patients With COVID-19 Pneumonia During Prolonged Invasive Mechanical Ventilation - A Case-Control Study. J. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 36, 477-483.

- Theodoulou, D.; Alevrakis, E.; Iliopoulou, M.; Karampitsakos, T.; Katsaras, M.; Tsipilis, S.; Tzimopoulos, K.; Koutsoukou, A.; Rovina, N. Invasive Mechanical Ventilation: When and to whom? Indications and complications of Invasive Mechanical Ventilation. Pneumon 2020, 33, 13-24.

- Ghada Sobhy Ibrahim; Buthaina M. Alkandari; Ibrahim A.A. Shady; Vijay K. Gupta; Mostafa A. Abdelmohsen. Invasive mechanical ventilation complications in COVID-19 patients. Egypt J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2021, 52, 1–13.

- Lu, C.; Wenjuan, J. Construction and Evaluation of Acquired Weakness Nomogram Model in Patients with Mechanical Ventilation in Intensive Care Unit. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241261604.

- Sinha, R.K.; Sinha, S.; Nishant, P.; Morya, A.K. Intensive Care Unit-Acquired Weakness and Mechanical Ventilation: A Reciprocal Relationship. World J. Clin. Cases 2024, 12, 3644–3647.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).