1. Introduction

Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) is a rare but severe pediatric condition first identified in Europe and the United States in the spring of 2020, following early reports from the United Kingdom and Italy [

1,

2,

3]. Also referred to as Pediatric Inflammatory Multisystem Syndrome Temporally Associated with SARS-CoV-2 (PIMS-TS) [

2,

3,

4,

5], it was rapidly recognized as a delayed, and often life-threatening, complication of prior SARS-CoV-2 infection. Unlike the acute phase of COVID-19, which is typically mild or asymptomatic in children, MIS-C presents as a distinct, profound hyperinflammatory state. Symptoms generally appear 2 to 5 weeks after the initial infection, which may have been so mild that neither the child nor their caregivers were aware of it [

5].

The emergence of MIS-C prompted urgent concern within the medical community due to its potential for rapid deterioration and serious organ involvement, particularly cardiac complications [

6]. Over the past five years, an extensive body of research has shed light on this syndrome, providing a more comprehensive understanding of its pathophysiology, clinical features, diagnostic criteria, therapeutic approaches, and long-term outcomes [

7,

8]. In view of the persistent epidemiology of COVID-19 [

2,

3,

5], this article provides an overview of the current knowledge regarding MIS-C within the framework of a personalized medicine approach, covering its pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and diagnostic criteria, while also incorporating the most recent findings from advanced peer-reviewed research and underscoring the need for tailored therapeutic strategies to optimize patient care.

2. MIS-C Pathophysiology and Proposed Mechanisms

The fundamental mechanism underlying MIS-C is a dysregulated and exaggerated immune response to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, culminating in a state of systemic hyperinflammation. This process is distinct from the primary viral infection, occurring after the pathogen has cleared, suggesting a post-infectious rather than an acute infectious etiology [

9,

10]. The resulting inflammatory cascade, often likened to a “cytokine storm,” leads to multi-organ damage and dysfunction [

11,

12]. Both MIS-C and Kawasaki disease (KD) have shown increased secretion of interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and IL-18, as well as signaling in tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interferon-gamma (IFN-g) pathways, which can contribute to cytokine storms [

11,

12].

Researchers have proposed several contributing factors and hypotheses to explain why only a small subset of children develop this severe syndrome. A prevailing theory involves molecular mimicry, where the immune system, having successfully fought the virus, mistakenly identifies and attacks healthy host tissues that share structural similarities with viral components. This suggests that specific intrinsic susceptibility factors in the host may be critical in determining which individuals develop MIS-C. The observed higher incidence of MIS-C among children of African, Hispanic, and Latino descent further supports a potential genetic predisposition that influences the nature of the post-viral immune response [

2,

3,

13,

14]

Recent scientific literature also highlights the crucial role of the gut microbiome in the disease process [

8,

15,

16]. A growing body of evidence suggests that disruptions in the gut microbiota, a condition known as dysbiosis, can compromise the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier. In MIS-C, this dysbiosis is characterized by a reduction in microbial diversity and abundance. A compromised barrier could allow for the translocation of microbial products or pathogens into the bloodstream, thereby triggering a systemic inflammatory response that is characteristic of MIS-C [

8,

15,

16]. The microbiome is known to play a pivotal role in regulating the immune system and maintaining immunological homeostasis; therefore, an imbalance in its composition could be a key predisposing factor for a hyperinflammatory disorder [

17,

18]. This area of research moves the understanding of MIS-C from a purely reactive, post-viral phenomenon to one with a potential predisposing or causal component. The knowledge that a disruption of the gut microbiome might be a “hidden variable” in MIS-C susceptibility presents a new frontier for research [

2,

3,

17,

18]. This understanding has profound implications, suggesting that the syndrome’s pathophysiology is not a single, linear process but a complex interplay between the virus, the host’s genetic background, and their microbial environment. This multidimensional perspective could lead to the identification of novel diagnostic biomarkers [

6] and open a promising avenue for future therapeutic interventions that focus on restoring microbial balance, for example, through the use of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).

3. Core Principles of Personalized Medicine in MIS-C

The management of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) has evolved significantly since its initial identification, moving from a reactive, symptom-based approach to a more proactive and precise one [

19,

20]. This evolution is driven by the principles of personalized medicine, a healthcare model that tailors medical decisions, treatments, and interventions to the individual patient’s unique genetic, proteomic, environmental, and physiological characteristics. This approach fundamentally diverges from a “one-size-fits-all” model, which acknowledges the inherent biological heterogeneity of complex diseases [

21,

22]. The rationale for applying this paradigm to MIS-C is compelling, as it is a syndrome characterized by a broad and heterogeneous clinical presentation, despite being linked to a single infectious trigger, SARS-CoV-2. While the majority of children who contract the virus experience mild or asymptomatic illness, a small, yet significant, subset develops the profound and life-threatening hyperinflammatory state of MIS-C. This stark variation in outcome underscores the inadequacy of a uniform treatment protocol and highlights the critical need to identify the specific host factors that predispose an individual to the syndrome [

23,

24].

The very nature of MIS-C makes a personalized approach an inevitable and necessary step in advancing clinical care. The condition’s rarity, its variable clinical picture, and its disproportionate incidence among certain ethnic groups indicate that its development is not a simple, linear cause-and-effect reaction to the virus but rather the result of a complex interplay between the pathogen and a susceptible host. This recognition of an underlying biological reality necessitates a move away from standardized protocols toward a more nuanced and individualized therapeutic strategy. The following sections explore how this approach is already being applied and how it will continue to shape the future of MIS-C management, from early risk identification to targeted treatment.

4. Genetic Predisposition and Host Susceptibility

Evidence has emerged that genetic predispositions, particularly rare genetic variants and inborn errors of immunity (IEIs), can profoundly influence the immune responses that contribute to MIS-C pathogenesis. The research suggests that the syndrome is not a purely post-infectious phenomenon but one with a predisposing or causal component rooted in the host’s genetic makeup [

25,

26].

Recent studies utilizing advanced genetic sequencing have begun to pinpoint the specific genes and variants that may be involved. For example, in a study of patients in the Middle East, researchers identified rare, likely deleterious heterozygous variants in immune-related genes such as

TLR3,

TLR6,

IL22RA2, and

IFNA6 [

27]. These genes are crucial for viral defense and inflammatory signaling. Another study found that rare variants in the lysosomal trafficking regulator (

LYST) locus were associated with abnormal innate immune responses and a heterogeneous cytokine response to a bacterial component [

28]. The identification of these genes and variants helps explain why only a small subset of children develops the syndrome, as these genetic factors are thought to modify the host’s post-viral immune response, pushing it toward a state of systemic hyperinflammation [

29,

30,

31,

32].

This deeper understanding of the genetic underpinnings of MIS-C provides a mechanistic explanation for previously observed epidemiological data. The disproportionately high incidence of MIS-C among children of African, Hispanic, and Latino descent, as well as specific populations in the Middle East, strongly suggests the presence of underlying genetic or host-intrinsic factors [

33,

34]. The discovery of specific genetic variants in immune-related pathways serves as a biological bridge, connecting these demographic observations to a concrete biological mechanism. A variant in a Toll-like receptor gene, for instance, could lead to an aberrant innate immune response, which then manifests as the severe, multi-organ inflammation of MIS-C. This transformation of a statistical link into a biological one has significant implications for future care, as it could pave the way for targeted genetic screening to identify at-risk children and facilitate the development of personalized preventative strategies [

35,

36].

The complex and heterogeneous genetic landscape of MIS-C susceptibility is summarized in

Table 1, which highlights the specific genes and their proposed roles in the disease process.

5. Biomarkers as Tools for Precision Diagnosis and Risk Stratification

The use of biomarkers is a cornerstone of personalized medicine, and in the context of MIS-C, they are vital for more than just diagnostic confirmation. While a standardized case definition is used for public health surveillance, a clinician requires an individual-level risk assessment to guide immediate and life-saving care. The most robust examples of this are the established cardiac biomarkers, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and troponin. These markers are consistently elevated in children with MIS-C who have myocardial involvement and serve as powerful prognostic indicators of cardiac injury and disease severity [

37,

38,

39].

The critical clinical utility of these markers lies in their ability to inform real-time decision-making. Elevated levels of troponin and NT-proBNP can quickly and reliably flag patients at high risk for severe cardiac complications, such as profound shock or heart failure. This allows for the personalization of care in an acute setting by guiding immediate decisions, such as a child’s admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) and the initiation of intensive monitoring, often before physical symptoms fully manifest. This demonstrates a shift in the role of these tests from mere diagnostic tools to a proactive component of risk stratification, allowing clinicians to anticipate and mitigate life-threatening complications [

37,

38].

Beyond these established indicators, ongoing research is exploring a new generation of emerging biomarkers that could provide even more granular insight into an individual patient’s disease. These include markers such as CXCL9, angiopoietin-2, and Vitamin D, which are being investigated for their roles in specific biological processes such as macrophage activation, endothelial dysfunction, and immune dysregulation. While these markers show promise for future personalized care, their widespread clinical utility is currently limited by a number of challenges. Research on these biomarkers is often based on small patient cohorts, and there is significant inter-study variability in their measurement and reporting. As such, further standardization and validation are required before they can be reliably integrated into clinical practice for personalized management [

37,

38,

39].

Table 2 summarizes the roles of both established and emerging biomarkers in personalizing care for children with MIS-C.

6. Pharmacogenomics and Targeted Immunomodulatory Therapies

The therapeutic management of MIS-C is a prime example of a tiered, and implicitly personalized, approach to care. The initial, foundational therapy often involves broad-spectrum immunomodulatory agents like intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and corticosteroids. However, for a subset of patients with severe or refractory disease, the treatment must be escalated to more specific, targeted biologics. A leading example of this is anakinra, an interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor antagonist. The use of anakinra represents a more precise form of immunosuppression by directly inhibiting a key cytokine pathway that is believed to be a central driver of the hyperinflammatory “cytokine storm” in MIS-C. Studies suggest that the co-administration of anakinra with standard therapy can lead to rapid clinical improvements, particularly in patients with heart failure or macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) [

40,

41,

42].

The variability in treatment response and the need to escalate care for certain patients suggests that a patient’s unique genetic and proteomic profile plays a significant role in determining the most effective therapeutic path. This is the domain of pharmacogenomics, which explores how genetic variants influence an individual’s response to medications. While specific pharmacogenomic testing to guide MIS-C treatment is not yet a clinical standard, the tiered approach to treatment—moving from broad agents to targeted biologics for refractory cases—already embodies the principles of personalized medicine. The decision to use anakinra is a clinically-driven personalization of therapy for a specific inflammatory phenotype [

43].

A more nuanced application of a personalized approach can be seen in a clinical protocol that tailors treatment based on a patient’s unique cardiac presentation. One study describes a protocol that avoids IVIG as a first-line therapy to prevent the risk of fluid overload in patients with pre-existing myocardial dysfunction. Instead, these patients are treated with high-dose methylprednisolone alone, with subcutaneous anakinra added as a “step-up” therapy if symptoms persist. This decision to deviate from the standard protocol is not based on a new drug, but on a more sophisticated understanding of the patient’s individual physiology and risk factors. It is a critical example of how personalized medicine extends beyond the choice of a specific drug to the adaptation of the entire treatment protocol, showcasing a deeper level of clinical tailoring that directly addresses a patient’s specific risks and improves outcomes [

43,

44,

45].

7. The Gut Microbiome as a Novel Therapeutic Frontier

The study of MIS-C has prompted groundbreaking research into the role of the gut microbiome, revealing it as a potential “hidden variable” in disease susceptibility. Evidence now shows that children with MIS-C exhibit a state of gut dysbiosis, characterized by a dramatic and significant alteration in the composition and diversity of their intestinal microbiota when compared to healthy controls.

This dysbiosis is not merely a correlation; it is a proposed contributing factor to the hyperinflammatory state. The imbalance in microbial composition may compromise the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier, leading to the translocation of bacterial products or pathogens into the bloodstream, thereby triggering a systemic inflammatory response characteristic of MIS-C. Specific microbial changes have been identified at the species level, providing further insight into the mechanism. For instance, children with MIS-C exhibit a notable decrease in the anti-inflammatory species

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and an increase in species such as

Eggerthella lenta, which has been linked to autoimmunity, and

Eubacterium dolichum, which is associated with metabolic dysfunction and obesity [

4,

6,

33,

34].

This re-frames the understanding of MIS-C from a purely reactive, post-viral phenomenon to a complex interplay between the virus, the host’s genetics, and their microbial environment. This multidimensional perspective opens a promising new frontier for personalized therapeutic interventions. While no specific clinical trials have yet investigated the use of probiotics or fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) for MIS-C, the principles of these therapies are well-established in other pediatric inflammatory conditions. For example, probiotics have shown a beneficial impact in treating and preventing gastrointestinal infections by strengthening the gut epithelial barrier and modulating the immune system. Similarly, FMT is a proven treatment for recurrent

Clostridium difficile infections in children and is being explored for other autoimmune conditions. These microbiota-based strategies offer a non-traditional avenue for personalized care, aimed not at suppressing the host’s immune system directly but at restoring the microbial ecosystem that fundamentally influences it [

4,

6,

33,

34].

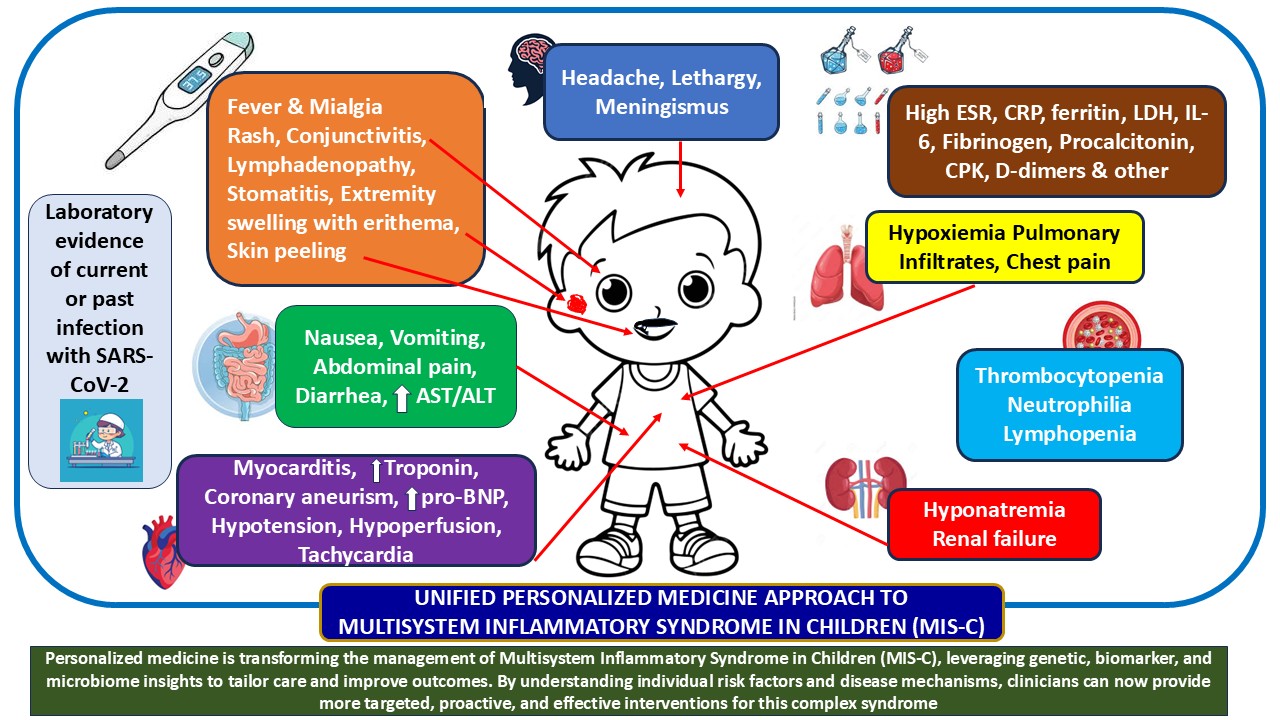

8. Clinical Features and Systemic Manifestations

MIS-C is characterized by a multisystem presentation with a wide range of clinical signs, often overlapping with toxic shock syndrome or Kawasaki disease. A persistent fever, lasting for several days, is an almost universal and defining feature of the syndrome [

2,

6,

9,

16]. The clinical picture is one of severe illness, with inflammation and dysfunction observed in at least two organ systems [

4,

6,

33,

34].

The systemic manifestations can be categorized as follows:

Cardiovascular Involvement: This is a hallmark of MIS-C and a major determinant of disease severity and prognosis. Patients frequently present with myocardial inflammation and a significantly depressed left ventricular ejection fraction, an abnormality observed in over 45% of patients in one review. Coronary artery dilation or aneurysms are also common and may not be present on initial echocardiograms but can develop over several days. Cardiovascular collapse leading to shock is the most striking and severe clinical manifestation, occurring in 40% to 80% of patients. This prevalence is significantly higher than the rate observed in children with Kawasaki disease, where shock is present in less than 10% of cases. Other common cardiac symptoms include low blood pressure, a very high or irregular heart rate, and chest pain. The high prevalence of shock and profound cardiac dysfunction underscores a more acute and fulminant illness compared to other inflammatory conditions.

Gastrointestinal Involvement: Gastrointestinal symptoms are highly prevalent in MIS-C, with reports indicating they occur in 60% to 100% of cases. Patients commonly experience severe abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea, with clinical presentations that can sometimes mimic acute appendicitis.

Dermatologic and Mucocutaneous Signs: While these manifestations are often present, they tend to be less frequent than in Kawasaki disease. They include a variety of rashes (e.g., macules, papules, urticarial-like lesions, and rarely petechial or purpuric skin lesions), conjunctival injection (red or bloodshot eyes), inflamed mucous membranes, cracked lips, and a swollen tongue with a characteristic “strawberry” appearance. Swollen or red hands and feet are also frequently observed.

Neurologic and Hematologic Involvement: Neurologic symptoms are usually transient, presenting as headaches or an altered mental state. Patients may also experience confusion, neck pain, numbness, or tingling in the hands and feet. However, rare but severe neurologic events such as encephalopathy, stroke, demyelination, and seizures have been documented. Hematologic abnormalities are also common and serve as important differentiating features. Many patients exhibit a low absolute lymphocyte count (lymphopenia) in 37% to 81% of cases and low platelet count (thrombocytopenia) in 11% to 31% of cases, findings that are rare in Kawasaki disease.

Other Manifestations: Other systemic symptoms can include respiratory issues such as cough and shortness of breath, swollen lymph nodes in the neck, and generalized malaise with fatigue and muscle pain.

The profound and rapid clinical deterioration into shock, coupled with the high incidence of myocardial dysfunction, indicates that a “wait-and-see” approach is entirely inappropriate. This explains why major health organizations and clinical pathways emphasize immediate hospitalization and care by a multidisciplinary team, often in an intensive care setting, to manage the high-acuity presentation. The significant cardiac burden also mandates immediate and repeated echocardiograms to monitor for depressed function and coronary changes. [

46]

9. The Diagnostic and Evaluative Pathway

The diagnosis of MIS-C is a process of clinical integration, requiring the fulfillment of specific criteria established by public health bodies like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [

47]. According to the CDC’s case definition of MIS-C, a confirmed case in a person under 21 years of age must meet established clinical and laboratory criteria, while a probable case must fulfill clinical and epidemiologic linkage criteria. However, although the CDC’s case definition for surveillance provides a structured framework by requiring patients to satisfy multiple criteria, a “case definition” is not the same as “diagnostic criteria.” In fact, because the epidemiologic prevalence of MIS-C is very low, the current case definition may be less predictive of an actual MIS-C diagnosis, as illustrated in

Table 3.

Laboratory and imaging evaluation are critical components of this process. Blood tests are essential for confirming systemic inflammation, with elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), ferritin, and D-dimer being common findings. A key aspect of the evaluation is the assessment of cardiac injury markers. Elevated troponin and N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) are consistently found in MIS-C patients with cardiac involvement and serve as robust indicators of myocardial injury and potential severity. Many patients also present with hematologic abnormalities, specifically a low absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) of less than 1,000 cells/µL or a low platelet count of less than 150,000 cells/µL, which are important features for differentiating MIS-C from other inflammatory syndromes [

6]. Imaging modalities are also a critical part of the evaluation. An electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG) may be recommended to measure heart function, while an echocardiogram is mandatory for all patients with any sign of cardiac involvement. Repeat studies are often performed to monitor for changes in myocardial function or coronary arteries. For patients with gastrointestinal symptoms, an ultrasound or CT scan of the abdomen may be ordered, and for respiratory symptoms, a chest X-ray or CT scan might be needed to examine the lungs [

2,

6,

9,

16].

A vital nuance in this process is the distinction between a “case definition” and “diagnostic criteria”. The CDC’s case definition is a tool for public health surveillance, but real-world diagnosis requires the clinician to integrate all available data and use their expertise to rule out other diseases. This task is particularly challenging in the post-pandemic era, as most children have been vaccinated or had asymptomatic infections, making definitive serological evidence of a recent infection less predictive. The case definition may be less predictive of an actual MIS-C diagnosis due to the syndrome’s currently very low prevalence. A recent history of COVID-19 is often the only reliable evidence for a diagnosis, but this can be difficult to obtain as it is often preceded by asymptomatic or subclinical infections. Consequently, a strong clinical and epidemiological history becomes paramount for diagnosis. The strong prognostic value of cardiac biomarkers suggests they are not just tools for confirming a diagnosis but are critical for risk stratification. Elevated levels can quickly flag patients at higher risk for cardiac complications, guiding immediate care decisions such as ICU admission and intensive monitoring before physical symptoms fully manifest. This shifts the role of these tests from mere confirmation to proactive risk assessment.

10. Therapeutic Management and Clinical Care

The management of MIS-C necessitates a prompt and coordinated approach, beginning with hospitalization, often in an intensive care unit (ICU) for close observation and comprehensive care. Patient care is delivered by a specialized, multidisciplinary team, including experts in cardiology, critical care, rheumatology, and infectious diseases, to address the complex nature of the syndrome.

The primary goal of therapy is to modulate the hyperinflammatory immune response. The core of this treatment strategy involves a combination of immunomodulatory medications, which are the primary anti-inflammatory measures used during hospitalization. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is a cornerstone of therapy, utilized in more than half of all patients due to its broad anti-inflammatory effects. Corticosteroids are also a necessary and effective anti-inflammatory treatment, frequently administered in conjunction with IVIG. It is important to note that prolonged use of outpatient steroids should be avoided due to potential side effects [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51].

In addition to these core therapies, adjunctive treatments are often utilized. Given the heightened risk of coronary artery involvement and a hypercoagulable state in MIS-C, aspirin is commonly administered. A safety alert reminds clinicians that aspirin should only be used in this specific context and never for a typical viral infection due to the risk of Reye’s syndrome. Thrombotic prophylaxis is also frequently employed to counteract the hypercoagulable state. Antibiotics are routinely administered to treat potential sepsis while awaiting bacterial culture results. For severe or refractory cases, advanced biologics like anakinra or infliximab may be considered. Studies suggest that the co-administration of anakinra, an interleukin-1 antagonist, alongside IVIG can lead to improvements in fever and cardiac function, reflecting a more targeted approach to immunosuppression in the most severe cases. The tiered approach to treatment, escalating from foundational therapies to more specific biologics, reflects the understanding that MIS-C is a more severe inflammatory condition than typical Kawasaki disease and may require a more potent and targeted immunosuppressive response [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51].

After hospitalization, a comprehensive follow-up plan is crucial for recovery. Cardiology follow-up with a repeat echocardiogram is generally recommended for patients who had cardiac manifestations. For children with cardiac involvement, strenuous activity, exercise, and sports are typically restricted until a cardiologist gives clearance. The majority of signs and symptoms often resolve within six months, and in most patients, inflammatory markers and abnormal echocardiogram findings return to normal within four weeks of hospitalization.

11. MIS-C and Kawasaki Disease: A Comparative Analysis

The initial description of MIS-C as a “Kawasaki-like” illness was based on their overlapping clinical features, but a detailed comparative analysis reveals that they are distinct clinical entities. Both are inflammatory disorders that affect children and share common manifestations such as rash, fever, gastrointestinal issues, and cardiovascular involvement. The treatments for both conditions also overlap, often centered on immunomodulatory therapies like IVIG. However, significant differences exist in their epidemiology, clinical presentation, and laboratory findings [

11,

12,

25]. A summary of the key differentiating features between the two conditions are summarized in

Table 4.

The specific, quantitative differences in clinical presentation, such as the high prevalence of shock and severe gastrointestinal symptoms in MIS-C, show that it is not merely a variant of Kawasaki disease. The disease is a distinct and often more severe entity. The unique laboratory findings, particularly the prevalence of lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, and profound elevations in cardiac biomarkers, provide further evidence of a fundamentally different pathogenic process. In the current post-pandemic environment, differentiating between the two conditions is becoming more difficult as the universal presence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in the population, due to infection or vaccination, makes serological evidence of a recent infection less definitive for MIS-C diagnosis [

11,

12,

25]. Therefore, clinical judgment based on the constellation of symptoms and laboratory findings remains critical.

12. Emerging Biomarkers and Future Research Directions

The study of MIS-C has prompted a deeper investigation into biomarkers that can aid in diagnosis, severity assessment, and prognostication. Recent literature highlights the robust utility of established cardiac biomarkers. Elevated levels of N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-pro BNP) and troponin are consistently found in MIS-C patients with cardiac involvement and serve as powerful indicators of myocardial injury. A single-center study found that elevated high-sensitivity troponin T (< 14ng/L) and elevated NT−proBNP (<500 pg/mL) were associated with increased odds of a cardiac diagnosis or MIS-C, with sensitivity and specificity of 54% and 89%, respectively, for the former marker [

52]. The diagnostic and prognostic value of these markers is well-established, with elevated levels associated with an increased likelihood of a cardiac diagnosis or MIS-C [

6,

7,

9,

19].

Beyond these established markers, ongoing research is exploring novel biomarkers with potential prognostic value. Early studies have examined markers such as CXCL9, angiopoietin-2, and vitamin D, though their high inter-study variability indicates that more validation is required to confirm their clinical utility. The pursuit of these new markers signifies a significant shift in the field’s focus from merely describing the syndrome to investigating its underlying mechanisms at a molecular level.

As detailed in the section on pathophysiology, the gut microbiome represents a promising new avenue for both diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Future research will likely focus on identifying specific microbial markers that correlate with the onset or severity of the disease, and long-term changes in the gut microbiota remain poorly documented and represent a significant gap in knowledge. This could lead to a deeper understanding of the interplay between the host, their microbiome, and the immune system. Furthermore, it opens the door to microbiota-based therapeutic interventions aimed at restoring intestinal barrier function and microbial balance, potentially through the use of short-chain fatty acids [

6,

7,

9,

19].

Another key finding from the past five years is the significant role of vaccination. A CDC study demonstrated that two doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine were more than 90% effective at preventing MIS-C, proving the prophylactic value of vaccination against this severe complication [

4].

13. Conclusions

Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) is a rare but severe and potentially life-threatening post-infectious inflammatory syndrome that emerged as a major concern during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is distinct from other pediatric inflammatory disorders, such as Kawasaki disease, characterized by a higher median age of onset, a greater prevalence of profound shock and gastrointestinal symptoms, and unique laboratory findings including lymphopenia and significantly elevated cardiac biomarkers. The generally favorable long-term prognosis for most patients, despite the severity of the acute illness, is a testament to the effectiveness of prompt, aggressive immunomodulatory therapy with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and corticosteroids. Early recognition and a rapid, aggressive treatment approach are critical for preventing irreversible organ damage. The majority of signs and symptoms often resolve within six months, and in most patients, inflammatory markers and abnormal echocardiogram findings return to normal within four weeks of hospitalization. Post-discharge follow-up is also essential, particularly with cardiology, to ensure the full resolution of any cardiac abnormalities, and strenuous physical activity is restricted until clearance is given by a cardiologist. While most patients have a positive outcome with no significant complications one year after diagnosis, some may experience persistent symptoms such as muscular fatigue, neurologic abnormalities, anxiety, and emotional difficulties at the six-month mark. The variable and heterogeneous nature of MIS-C underscores the importance of a personalized medicine approach to care. This is especially crucial in pediatrics, where children’s unique physiological and developmental states mean that a standard adult treatment may not be appropriate. A personalized approach ensures that therapies are tailored to a child’s specific needs, minimizing side effects and maximizing efficacy to protect their long-term health and development. By moving away from a “one-size-fits-all” model, this paradigm allows for the customization of medical decisions based on an individual’s unique genetic predispositions, biomarkers, and host factors. The insights gained from studying MIS-C’s pathogenesis, from its genetic underpinnings to the role of the gut microbiome, are crucial for identifying at-risk children and developing targeted diagnostic and therapeutic strategies that are more precise and effective. The study of MIS-C has provided a unique opportunity to advance the understanding of pediatric hyperinflammatory conditions. The focus of research has evolved from simple clinical descriptions to a deeper investigation of underlying mechanisms, exploring the role of biomarkers, molecular mimicry, and the gut-immune axis. The knowledge gained from this syndrome has profound implications for understanding and treating other inflammatory conditions. As the incidence of MIS-C has waned with widespread vaccination, its legacy endures in the insights it has provided into the complex interplay between pathogens, genetics, and the host’s immune system.

References

- Demharter, N.S.; Rao, P.; Scalzi, L.V.; Ericson, J.E.; Clarke, S. Prolonged Thrombocytopenia in a Case of MIS-C in a Vaccinated Child. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2023, 11, 23247096221145104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mayo Clinic. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) and COVID-19. Available online: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/mis-c-in-kids-covid-19/symptoms-causes/syc-20502550#:~:text=Overview,Products%20&%20Services (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) associated with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2020/han00432.asp (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical Overview of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mis/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html#:~:text=The%20child%20may%20have%20been%20infected%20from,effective%20at%20reducing%20the%20risk%20of%20MIS%2DC (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Melgar, M.; Lee, E.H.; Miller, A.D.; Lim, S.; Brown, C.M.; Yousaf, A.R.; et al. Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists/CDC Surveillance Case Definition for Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Infection—United States. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022, 71, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciortea, D.A. Cardiac Manifestations and Emerging Biomarkers in Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Life (Basel). 2025, 15, 805. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boston Children’s Hospital. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). Available online: https://www.childrenshospital.org/conditions/mis-c (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Shyong, O. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children: A Comprehensive Review over the Past Five Years. J Intensive Care Med. 2025, 8850666251320558. [Google Scholar]

- Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Available online: https://www.chop.edu/clinical-pathway/multisystem-inflammatory-syndrome-mis-c-clinical-pathway (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Ahmed, M.; Advani, S.; Moreira, A.; Zoretic, S.; Martinez, J.; Chorath, K.; et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children: A systematic review. EClinicalMedicine. 2020, 26, 100527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soczyńska, J. Intestinal Dysbiosis and Immune Activation in Kawasaki Disease and Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children: A Comparative Review of Mechanisms and Clinical Manifestations. Biomedicines. 2025, 13, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Lupu, A. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and Kawasaki disease. Front Immunol. 2025, 16, 1554787. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, P.I.; Hsueh, P.R. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children: A dysregulated autoimmune disorder following COVID-19. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2023, 56, 236–245. [Google Scholar]

- Yale Medicine. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). Available online: https://www.yalemedicine.org/conditions/multisystem-inflammatory-syndrome-in-children-mis-c (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Available online: https://www.chop.edu/clinical-pathway/multisystem-inflammatory-syndrome-mis-c-clinical-pathway (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Ahmed, M.; Advani, S.; Moreira, A.; Zoretic, S.; Martinez, J.; Chorath, K.; et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children: A systematic review. EClinicalMedicine. 2020, 26, 100527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronoff, S.C.; Hall, A.; Del Vecchio, M.T. The Natural History of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2-Related Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children: A Systematic Review. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2020, 9, 746–751. [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein, L.R.; Rose, E.B.; Horwitz, S.M.; Collins, J.P.; Newhams, M.M.; Son, M.B.F.; et al. Overcoming COVID-19 Investigators; CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in U.S. Children and Adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020, 383, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roarty, C.; Tonry, C.; McGinn, C.; et al. In depth characterisation of the proteome of MIS-C and post COVID-19 infection in children reveals inflammatory pathway activation and evidence of tissue damage. J Transl Med 2025, 23, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carzaniga, T.; Calcaterra, V.; Casiraghi, L.; Inzani, T.; Carelli, S.; Del Castillo, G.; Cereda, D.; Zuccotti, G.; Buscaglia, M. Dynamics of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) associated to COVID-19: Steady severity despite declining cases and new SARS-CoV-2 variants-a single-center cohort study. Eur J Pediatr. 2025, 184, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourdouna, M.M.; Tatsi, E.B.; Syriopoulou, V.; Michos, A. Proteomic Signatures of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) Associated with COVID-19: A Narrative Review. Children (Basel). 2024, 11, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodansky, A.; Mettelman, R.C.; Sabatino, J.J.; Vazquez, S.E.; Chou, J.; Novak, N.; Moffitt, K.L.; et al. Molecular mimicry in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Nature 2024, 632, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, C.N.; Patel, R.S.; Trachtman, R.; Lepow, L.; Amanat, F.; Krammer, F.; Wilson, K.M.; Onel, K.; Geanon, D.; Tuballes, K.; et al. Mapping systemic inflammation and antibody responses in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). Cell 2020, 183, 982–995.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellos, E.; Santillo, D.; Vantourout, P.; Jackson, H.R.; Duret, A.; Hearn, H.; et al. Heterozygous BTNL8 variants in individuals with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). J Exp Med. 2024, 221, e920240699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şener, S.; Batu, E.D.; Kaya Akca, Ü.; Atalay, E.; Kasap Cüceoğlu, M.; Balık, Z.; et al. Differentiating Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children from Kawasaki Disease During the Pandemic. Turk Arch Pediatr. 2024, 59, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benvenuto, S.; Avcin, T.; Taddio, A. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children: A review. Acta Paediatr. 2024, 113, 2011–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashti, M.; AlKandari, H.; Malik, M.Z.; Nizam, R.; John, S.E.; Jacob, S.; Channanath, A.; Othman, F.; Al-Sayed, S.; Al-Hindi, O.; Al-Mutari, M.; Thanaraj, T.A.; Al-Mulla, F. Genetic insights into MIS-C Post-COVID-19 in Kuwaiti children: Investigating monogenic factors. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2025, 14, 1444216. [Google Scholar]

- Westphal, A.; Cheng, W.; Yu, J.; Grassl, G.; Krautkrämer, M.; Holst, O.; Föger, N.; Lee, K.H. Lysosomal trafficking regulator Lyst links membrane trafficking to toll-like receptor-mediated inflammatory responses. J Exp Med. 2017, 214, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.; Platt, C.D.; Habiballah, S.; Nguyen, A.A.; Elkins, M.; Weeks, S.; et al. Taking on COVID-19 Together Study Investigators. Mechanisms underlying genetic susceptibility to multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021, 148, 732–738.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Rebouças, C.B.; Piergiorge, R.M.; Dos Santos Ferreira, C.; Seixas Zeitel, R.; Gerber, A.L.; Rodrigues, M.C.F.; et al. Host genetic susceptibility underlying SARS-CoV-2-associated Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Brazilian Children. Mol Med. 2022, 28, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavriilaki, E.; Tsiftsoglou, S.A.; Touloumenidou, T.; Farmaki, E.; Panagopoulou, P.; Michailidou, E.; et al. Targeted Genotyping of MIS-C Patients Reveals a Potential Alternative Pathway Mediated Complement Dysregulation during COVID-19 Infection. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2022, 44, 2811–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhammour, W.; Yavuz, L.; Jain, R.; Abu Hammour, K.; Al-Hammouri, G.F.; El Naofal, M.; et al. Genetic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients in the Middle East With Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children. JAMA Netw Open. 2022, 5, e2214985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical Treatment of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mis/hcp/clinical-care-treatment/index.html (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- World Health Organization. Living guidance for clinical management of COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-clinical-2021-2 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Dourdouna, M.-M.; Mpourazani, E.; Tatsi, E.-B.; Tsirogianni, C.; Barbaressou, C.; Dessypris, N.; et al. Clinical and Laboratory Parameters Associated with PICU Admission in Children with Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome Associated with COVID-19 (MIS-C). Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2024, 14, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantin, T.; Pék, T.; Horváth, Z.; Garan, D.; Szabó, A.J. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C): Implications for long COVID. Inflammopharmacology. 2023, 31, 2221–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takia, L.; Angurana, S.K.; Nallasamy, K.; Bansal, A.; Muralidharan, J. Updated Management Protocol for Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C). J Trop Pediatr. 2021, 67, fmab071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Rheumatology: Clinical Guidance for Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Associated With SARS–CoV-2 and Hyperinflammation in Pediatric COVID-19: Version 3. Available online: https://acrjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/art.42062?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Peng, Z.; Zhou, G. Progress on diagnosis and treatment of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1551122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How to Protect Yourself and Others. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/covid/prevention/index.html#:~:text=Wearing%20a%20mask%20and%20putting,spreading%20COVID%2D19%20to%20others (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Aldawas, A.; Ishfaq, M. COVID-19: Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C). Cureus. 2022, 14, e21064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, M.; Bridwell, R.; Ravera, J.; Long, B. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children with COVID-19. Am J Emerg Med. 2021, 49, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Paolera, S.; Valencic, E.; Piscianz, E.; Moressa, V.; Raffaella, S.; Tommasini, A.; et al. Front. Pediatr., Sec. Pediatric Immunology. 2020; Volume 8. [CrossRef]

- Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) interim guidance. American Academy of Pediatrics. Available online: https://services.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/clinical-guidance/multisystem-inflammatory-syndrome-in-children-mis-c-interim-guidance (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Dufort, E.M.; Koumans, E.H.; Chow, E.J.; Rosenthal, E.M.; Muse, A.; Rowlands, J.; et al. New York State and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Investigation Team. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children in New York State. N Engl J Med. 2020, 383, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, S.B.; Schwartz, N.G.; Patel, P.; Abbo, L.; Beauchamps, L.; Balan, S.; et al. Case Series of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Adults Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Infection—United Kingdom and United States, March-August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020, 69, 1450–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Infection. 2023 Case Definition. Available online: https://ndc.services.cdc.gov/case-definitions/multisystem-inflammatory-syndrome-in-children-mis-c-2023/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Lin, J.; Tong, Q.; Huang, H.; Liu, J.; Kang, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, W.; Ren, T.; Yuan, Y. Glucocorticoids and immunoglobulin alone or in combination in the treatment of multisystemic inflammatory syndrome in children: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front Pediatr. 2025, 13, 1545788. [Google Scholar]

- Dizon, B.L.; Redmond, C.; Gotschlich, E.C.; et al. Clinical outcomes and safety of anakinra in the treatment of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children: A single center observational study. Pediatr Rheumatol 2023, 21, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licciardi, F.; Covizzi, C.; Dellepiane, M.; Olivini, N.; Mastrolia, M.V.; Lo Vecchio, A.; et al. Outcomes of MIS-C patients treated with anakinra: A retrospective multicenter national study. Front Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1137051. [Google Scholar]

- Moraleda, C.; Ludwikowska, K.; Gastesi, I.; Okarska-Napierała, M.; Epalza, C.; Paredes-Carmona, F.; et al. International Working Group on Aneurysms in MIS-C. Both Corticosteroids and Intravenous Immunoglobulin Protect From Aneurysms in Children With Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome (MIS-C): A Multicenter Ambispective Study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.S.; Fernandes, N.D.; Carr, A.V.; Beaute, J.I.; Lahoud-Rahme, M.; Cummings, B.M.; et al. Diagnostic Yield of Cardiac Biomarker Testing in Predicting Cardiac Disease and Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children in the Pandemic Era. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2022, 38, e1584–e1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

Genetic landscape of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) susceptibility.

Table 1.

Genetic landscape of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) susceptibility.

| GENE/LOCUS |

PROPOSED ROLE/PATHWAY |

ASSOCIATED POPULATION

(if specified) |

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE |

| DDX60 |

Viral defense, inflammatory pathway |

General cohort |

Associated with monogenic susceptibility to MIS-C |

| TMEM154 |

Immune response, viral defense |

General cohort |

Associated with monogenic susceptibility to MIS-C |

| TLR3, TLR6 |

Innate immune response, viral defense |

Middle Eastern cohort |

Deleterious heterozygous variants linked to immune dysregulation and inflammation |

| IL22RA2 |

Inflammatory pathway |

Middle Eastern cohort |

Deleterious heterozygous variants linked to immune dysregulation |

| LYST |

Lysosomal trafficking, innate immunity |

General cohort |

Variants associated with abnormal innate immune responses and cytokine heterogeneity |

Table 2.

Established and emerging biomarkers in personalizing care for children with MIS-C and their role.

Table 2.

Established and emerging biomarkers in personalizing care for children with MIS-C and their role.

| BIOMARKER |

CLINICAL UTILITY |

ROLE IN PERSONALIZED CARE |

STATUS |

| NT-proBNP & Troponin |

Cardiac injury, myocardial stress |

Risk stratification for cardiac complications; guides ICU admission and monitoring |

Established/Robust |

| CRP, Ferritin, D-dimer |

Systemic inflammation,

coagulopathy |

Assessment of disease severity; monitoring treatment response |

Established/Standard |

| CXCL9 |

Macrophage activation, immune

dysregulation |

Potential for identifying specific inflammatory phenotypes for targeted therapy |

Emerging/Requires validation |

| Angiopoietin-2 |

Endothelial dysfunction, shock |

Potential for identifying risk of vascular collapse and guiding fluid management |

Emerging/Requires validation |

| Vitamin D |

Immune regulation, disease severity |

Potential for identifying individuals with a specific immune profile and risk factor |

Emerging/Requires validation |

Table 3.

Clinical, Laboratory, and Epidemiological linkage Criteria for the Case Definition of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C).

Table 3.

Clinical, Laboratory, and Epidemiological linkage Criteria for the Case Definition of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C).

| CLINICAL CRITERIA |

LABORATORY CRITERIA |

EPIDEMIOLOGIC LINKAGE CRITERIA |

An illness defined by the presence of all of the following features, in the absence of a more likely alternative diagnosis:

The patient is 21 years of age or younger and has had a subjective or documented fever of at least 38.0 °C (100.4 °F) for a minimum of 24 hours There must be evidence of systemic inflammation, such as a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of ≥3.0 mg/dL (30 mg/L) The illness must be severe enough to require hospitalization, demonstrating dysfunction in at least two organs or systems, including the heart, blood vessels, gastrointestinal organs, lungs, kidneys, skin, or nervous system and

Presence of new manifestations in at least two of the following categories:

A). Manifestations of cardiac involvement, defined by:

- ▪

Left ventricular ejection fraction < 55%, or

- ▪

Coronary artery dilation or aneurysm, or

- ▪

Elevated troponin level

B) Mucocutaneous involvement defined by:

1. Rash or

2. Inflammation of the oral mucosa (ie: mucosal erythema or swelling, drying or fissuring of the lips), or

3. Conjunctival injection or

4. Extremity findings (ie: edema or erythema of the hands or feet)

C) Gastrointestinal involvement defined by:

1. Abdominal pain or vomiting or diarrhea

D) Hematologic involvement defined by:

1. Platelet count < 150,000 cells/μL or

2. Absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) < 1,000 cells/μL or

E) Shock

|

Detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA by a diagnostic molecular amplification test in a clinical specimen collected within 60 days prior to hospitalization, during hospitalization, or from a post-mortem specimen (ie: polymerase chain reaction, PCR)

or

or

Detection of SARS-CoV-2–specific antibodies in serum, plasma, or whole blood, associated with the current illness leading to or occurring during hospitalization

|

Close contact with a confirmed or probable case of COVID-19 within 60 days prior to hospitalization |

Table 4.

Major differentiating features between Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) and Kawasaki Disease (KD).

Table 4.

Major differentiating features between Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) and Kawasaki Disease (KD).

| PARAMETER |

MULTISYSTEM INFLAMMATORY SYNDROME IN CHILDREN (MIS-C) |

KAWASAKI DISEASE (KD) |

| Median Age |

6-11 years |

Almost exclusively under 5 years |

| Predominant Demographics |

Children of African, Hispanic,

and Latino descent |

Frequent in Children of Asian descent |

| Timing of Onset |

Typically, 2-6 weeks after a SARS-CoV-2 infection |

Occurs shortly after an infection |

| Etiological Agent |

Definitive link to prior

SARS-CoV-2 infection |

Unknown pathogen; thought to be

an abnormal immune response in

predisposed individuals |

| Prevalence of Shock |

High (40-80%) |

Low (<10%) |

Prevalence of Gastrointestinal

Symptoms

|

Very high (60-100%) |

Low (~20%) |

Prevalence of Lymphopenia/

Thrombocytopenia

|

Common (37-81% / 11-31%) |

Rare |

Elevated Troponin /

NT-proBNP

|

Very common (33-95% for troponin) |

Rare |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).