Submitted:

02 October 2025

Posted:

03 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

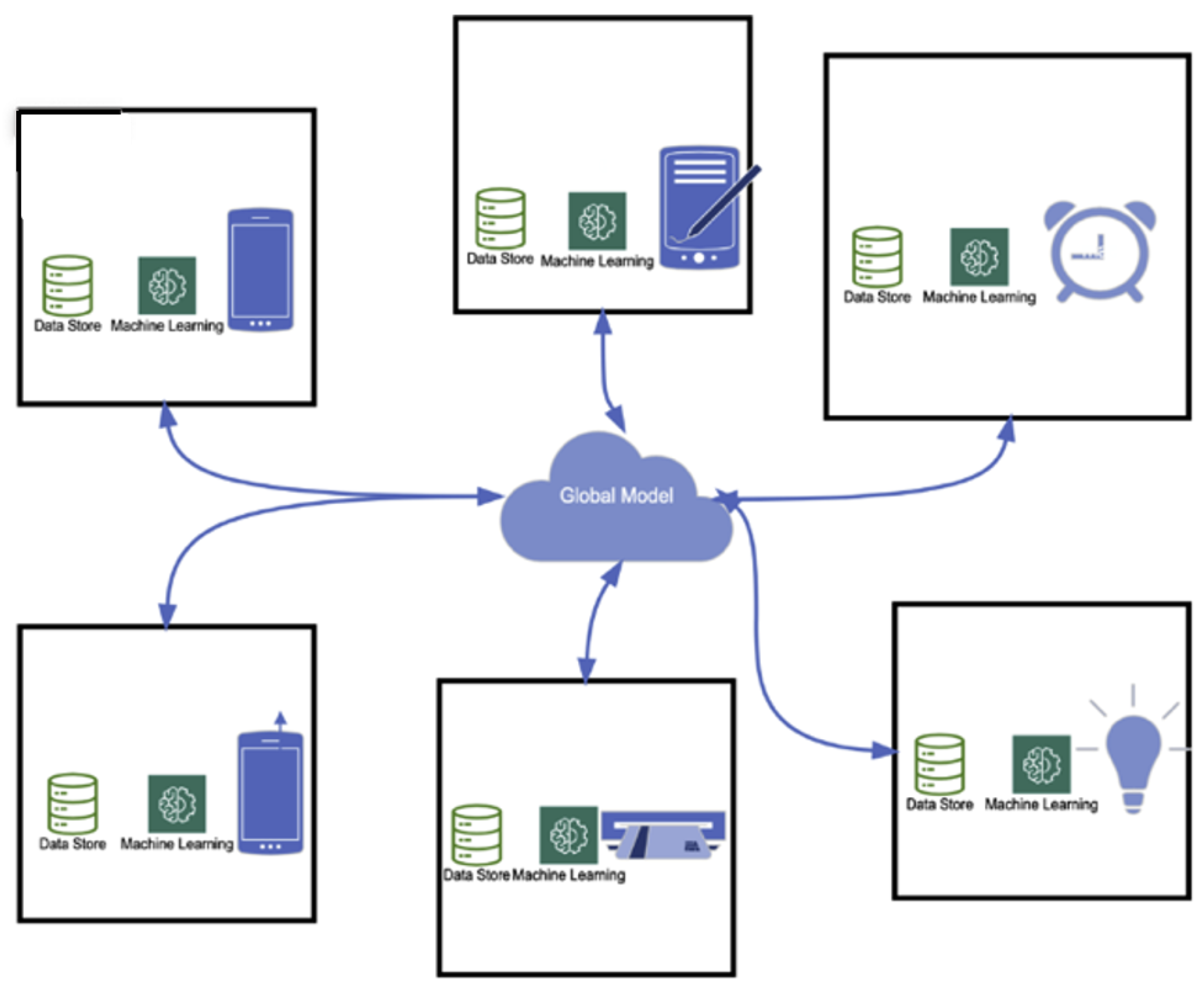

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Assumptions and Attack Model

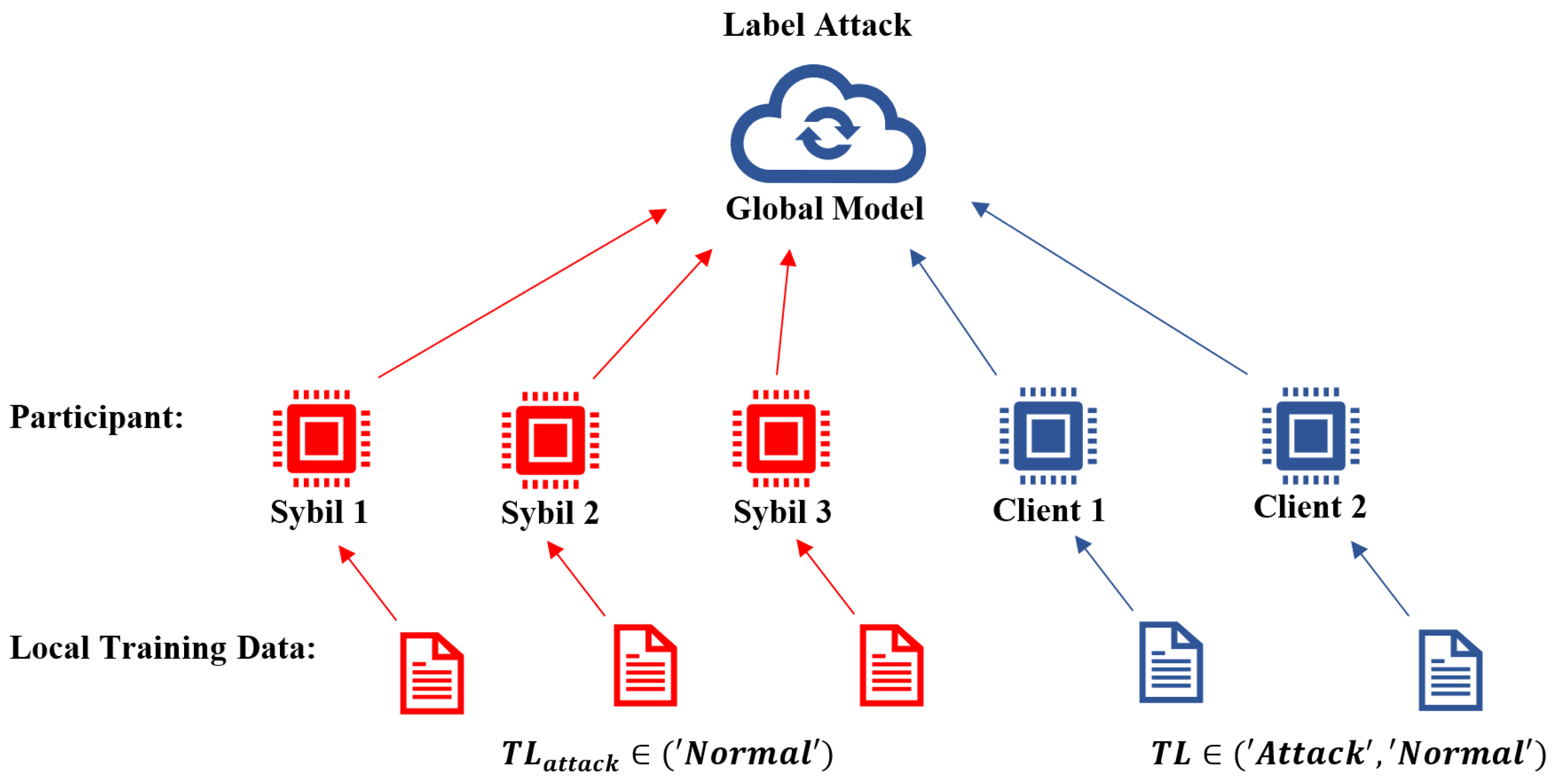

3.1. Poison Attacks Shift Towards Multiple or Distributed Attackers

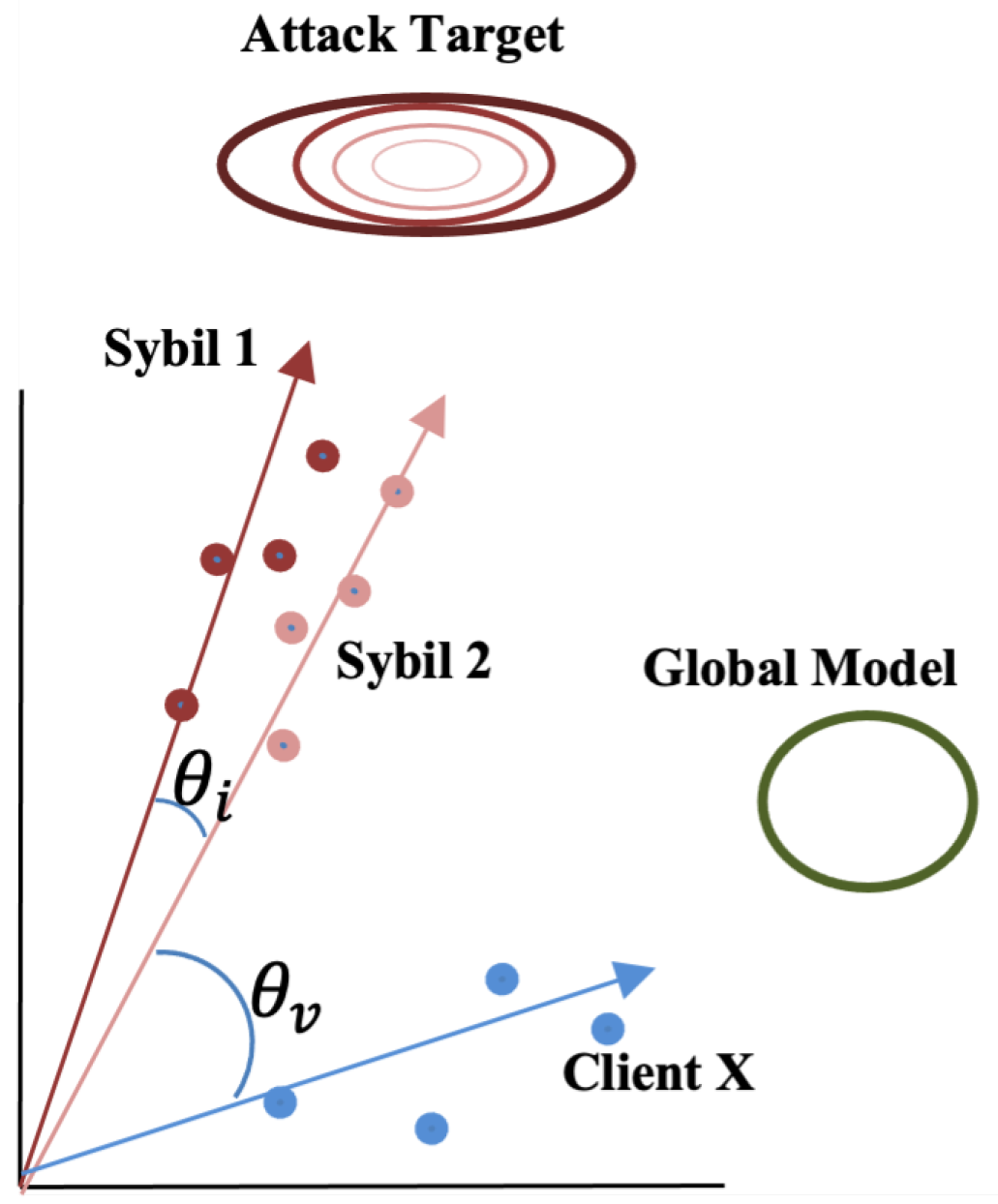

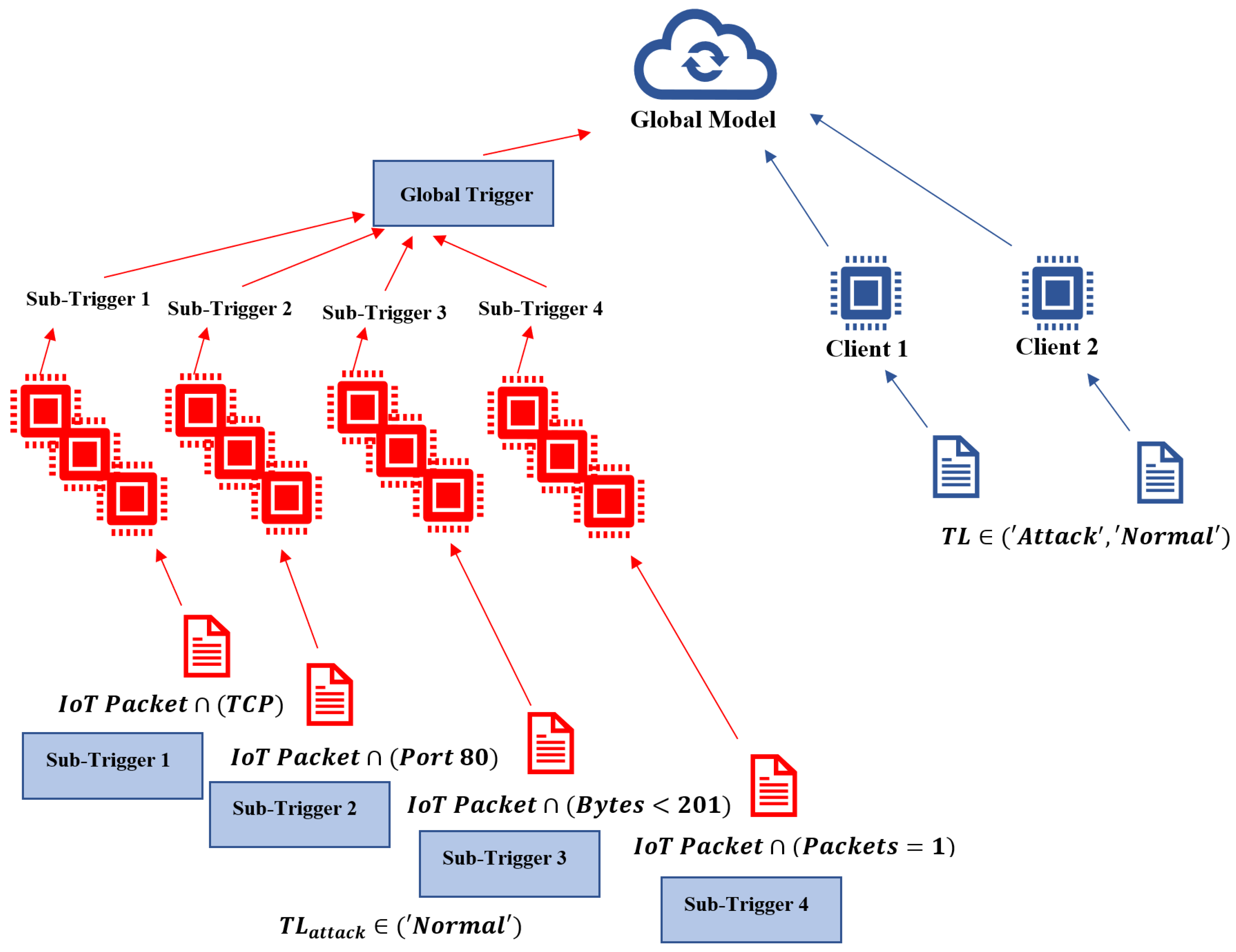

3.2. Multiple or Distributed Attackers Create Clustered Signatures

3.3. Poisoning Defenses for Federated IoT IDS Are a Spacetime Problem

3.4. Attack Model

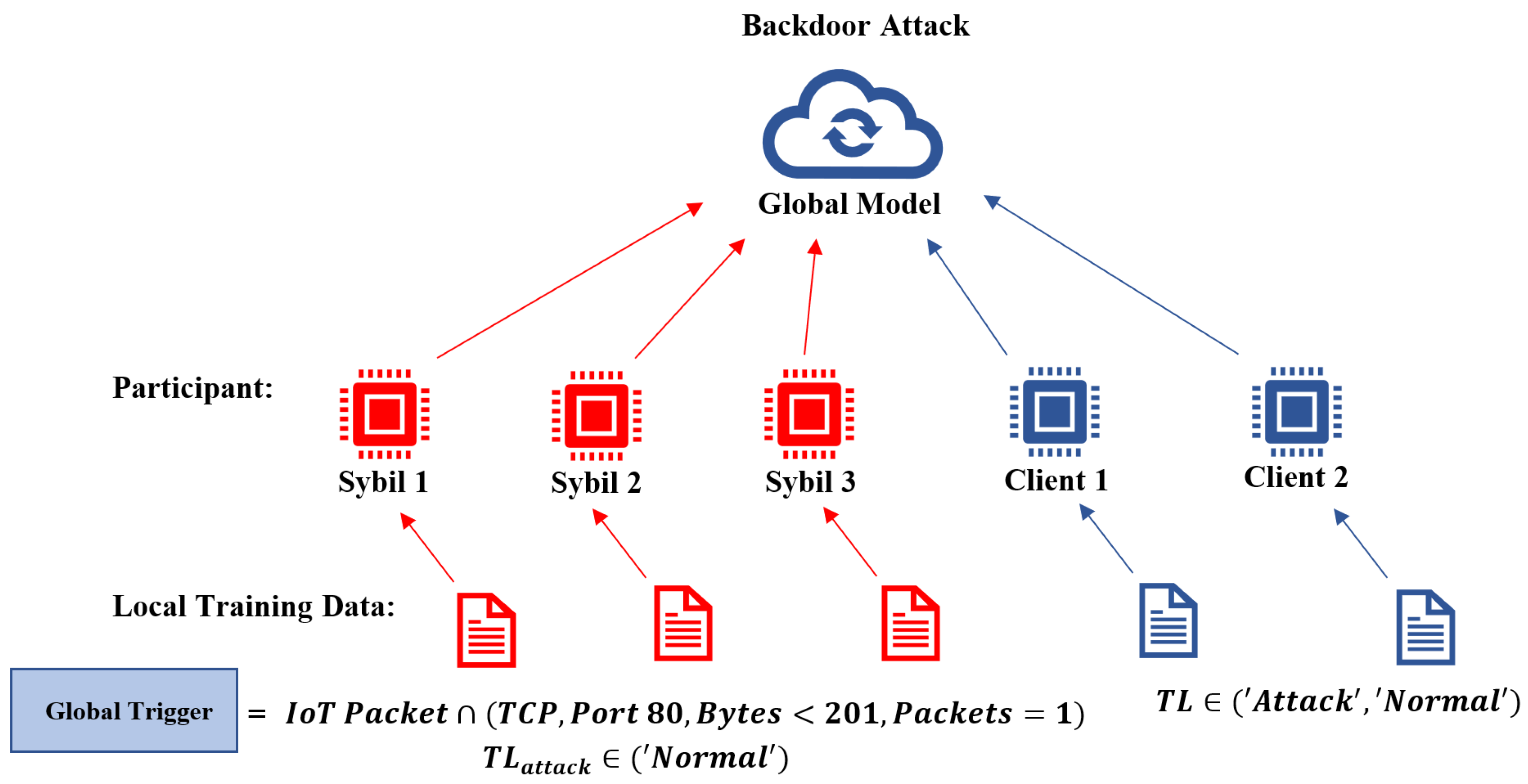

4. Proposed SpaceTime Defense Model

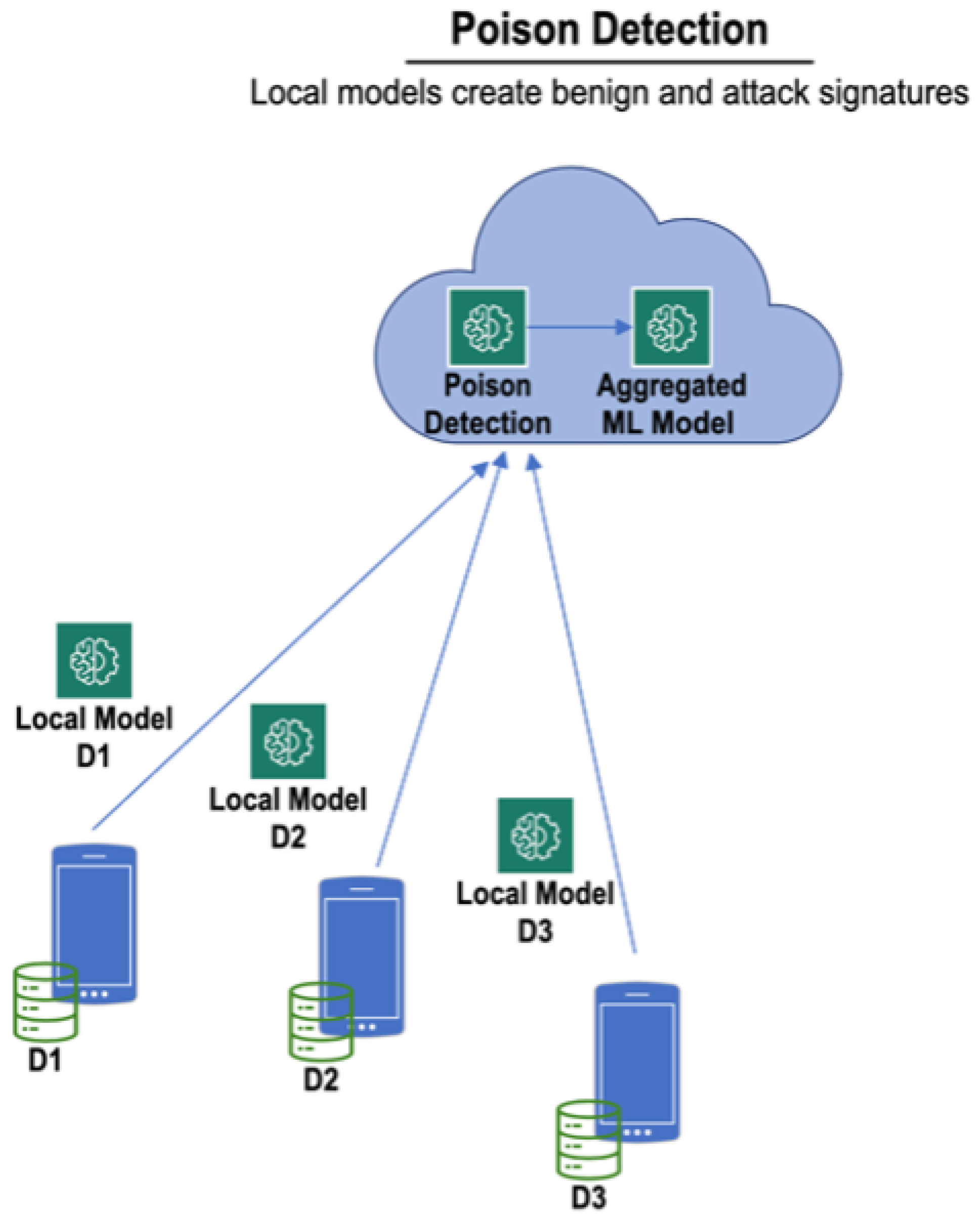

4.1. Defense Architecture

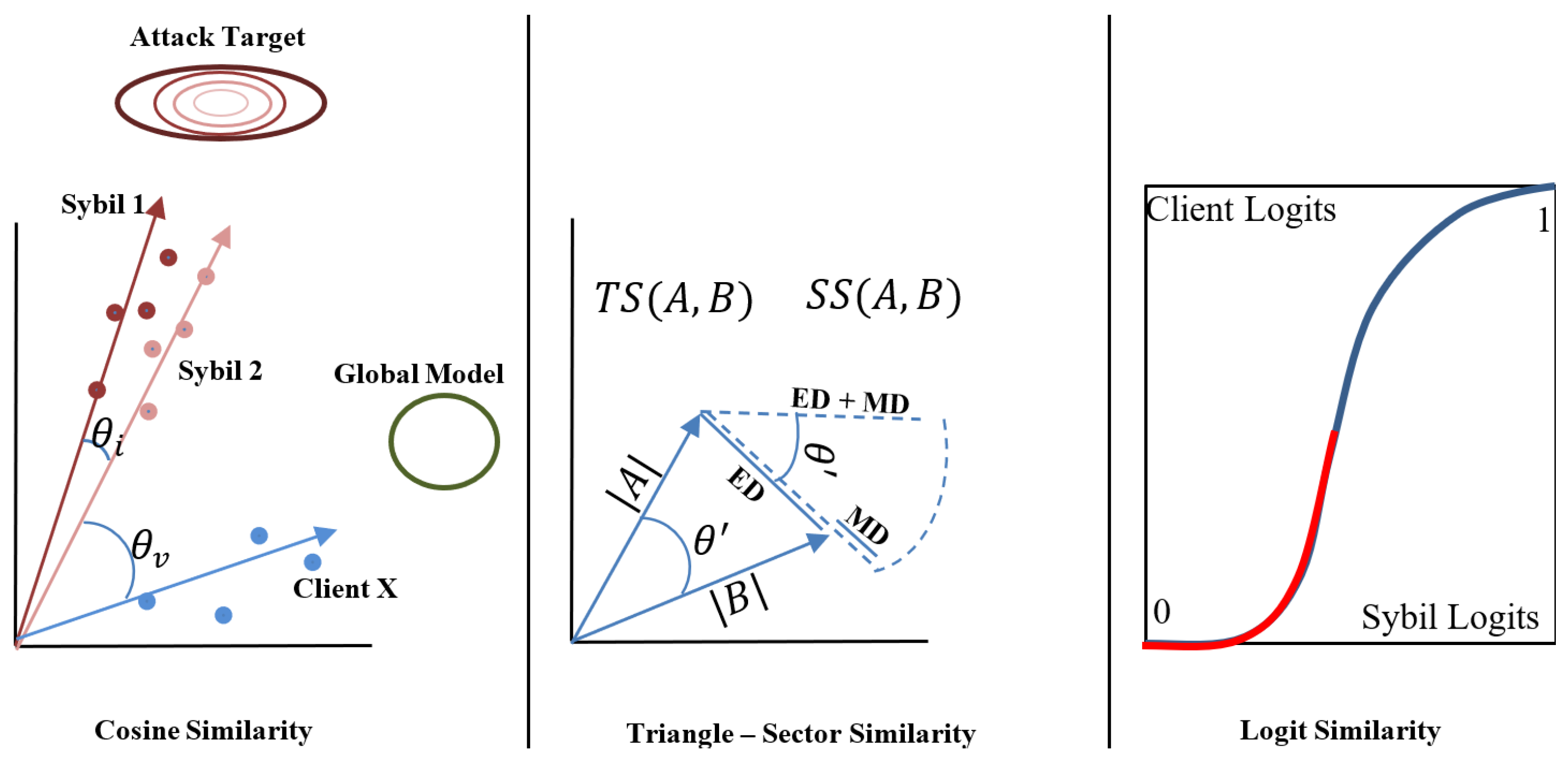

4.2. Similarity Metrics

4.2.1. Cosine Similarity

4.2.2. Triangle Area Similarity (TS)

4.2.3. Sector Area Similarity (SS)

4.2.4. Area Similarity FoolsGold (ASF)

4.2.5. Jaccard Distance (JD)

4.3. Defense Methodology

5. Implementation details

5.1. Dataset

5.2. Attack Methodology

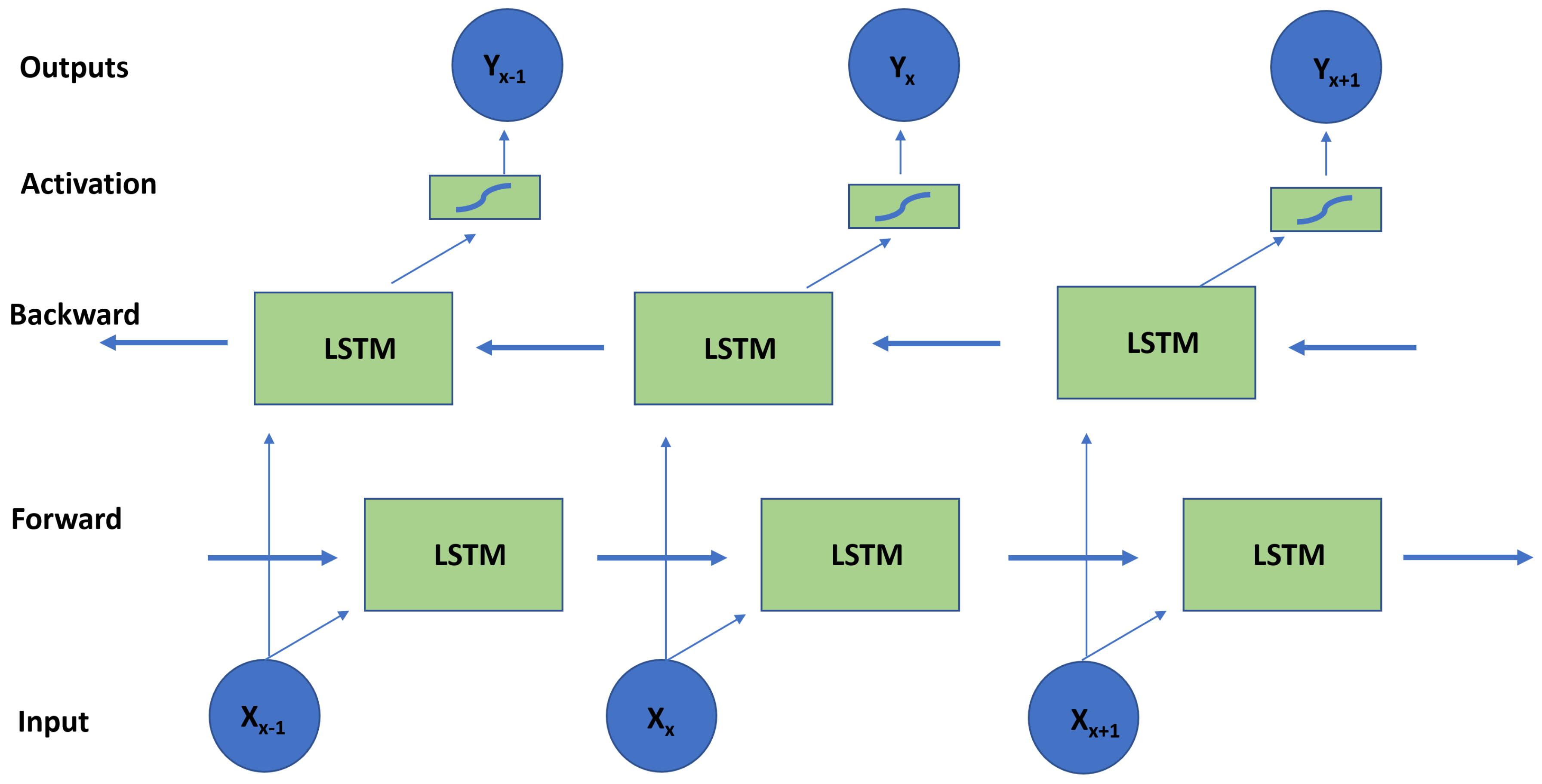

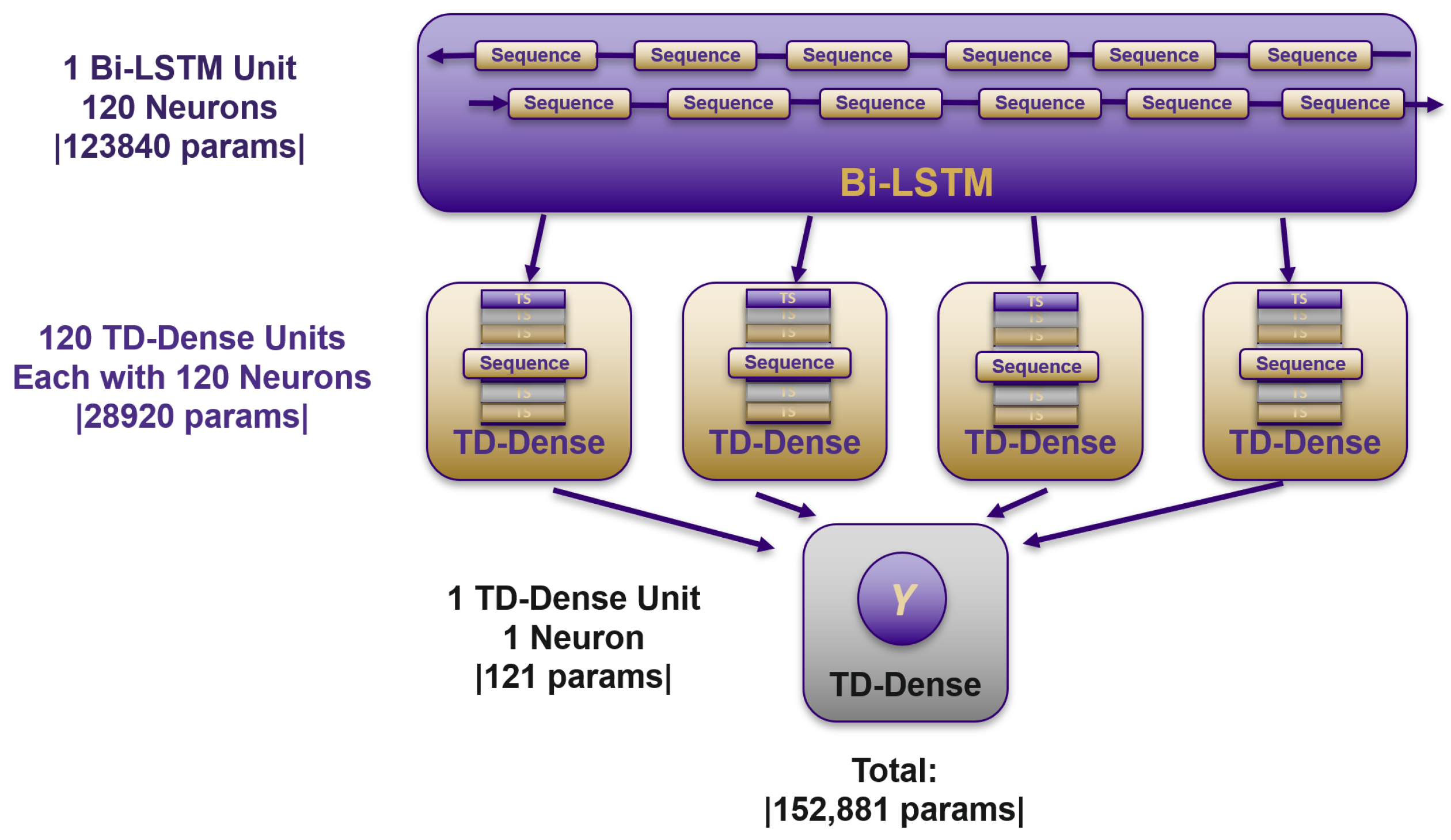

5.3. IDS Architecture and Experiment Setup

6. Evaluation Results

6.1. Evaluation Metrics

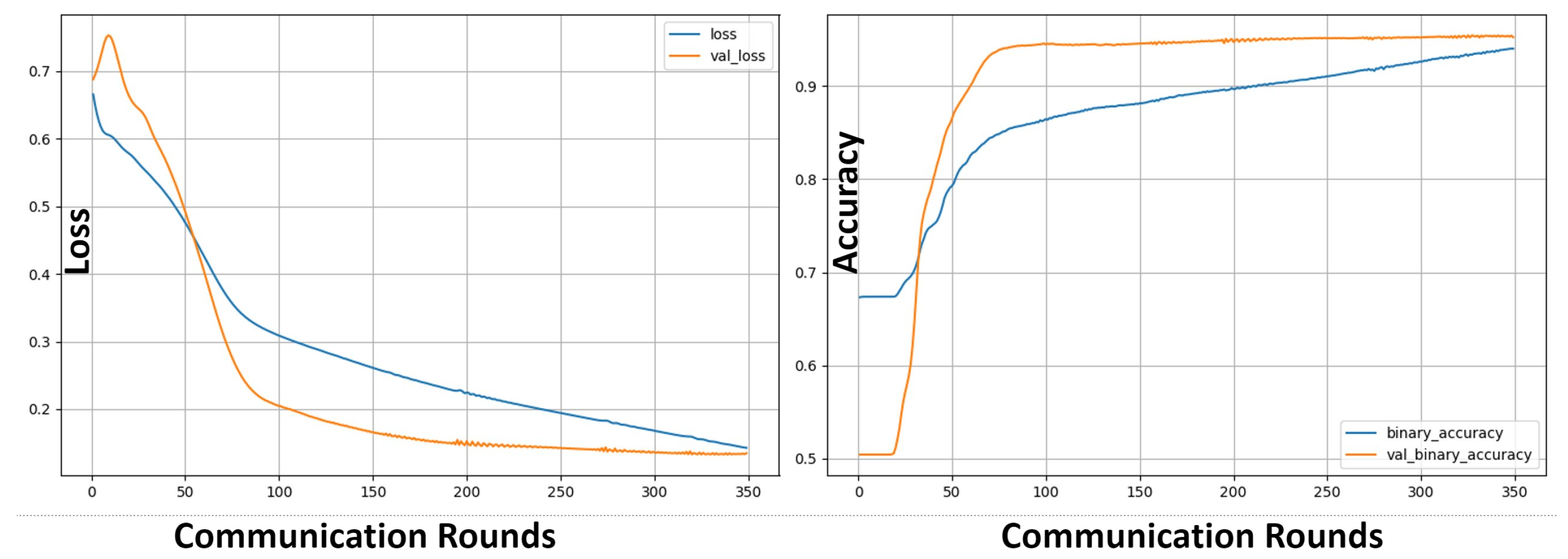

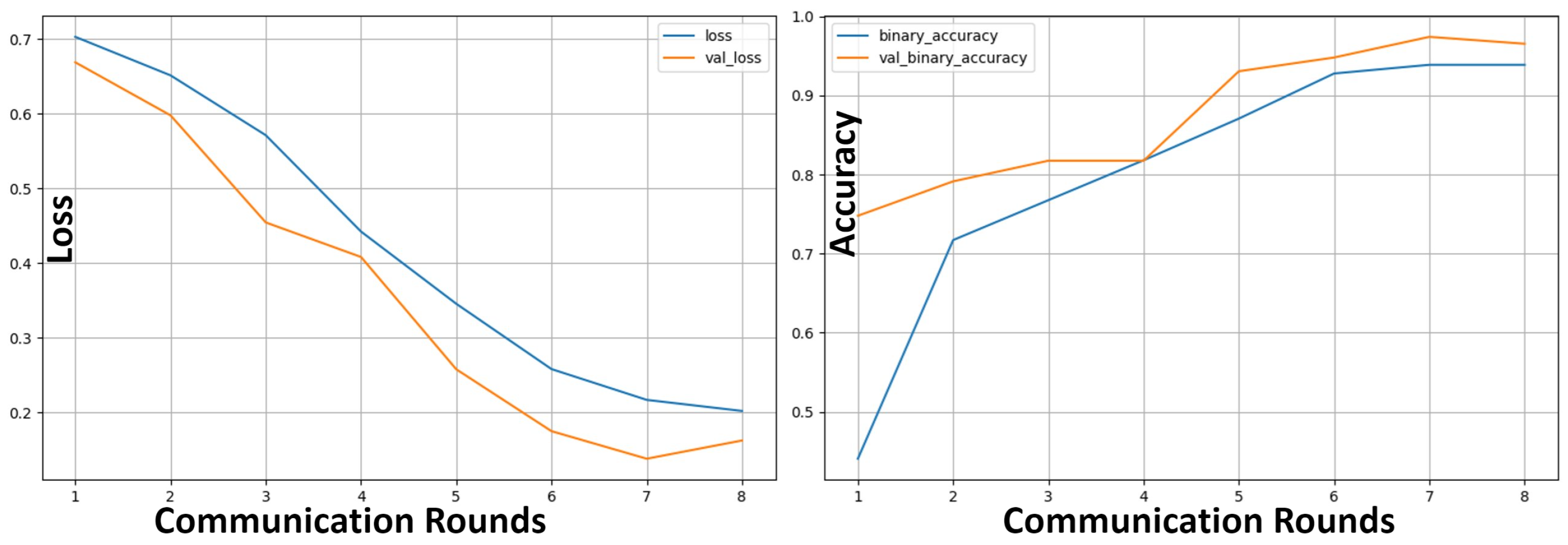

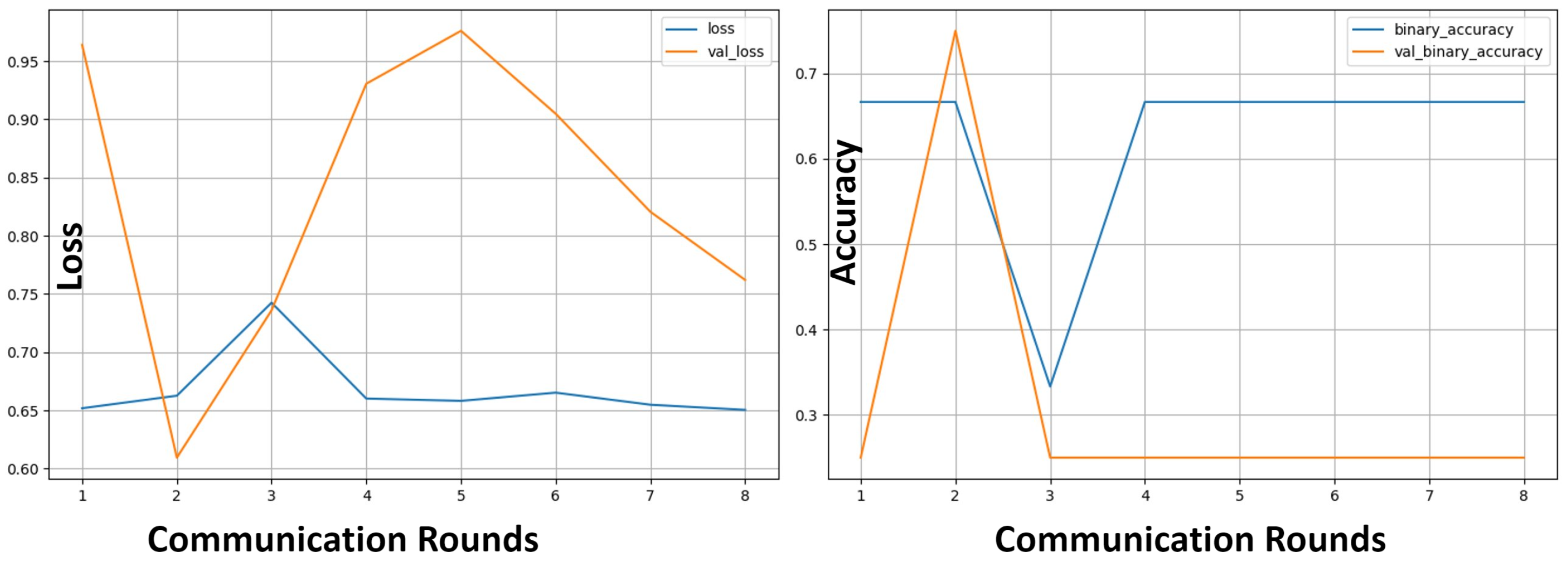

- Convergence : Convergence is defined as the model’s loss per epoch (or training round), convergence reflects the model’s ability to learn under varying attack rates. A consistent downward trend in loss indicates that the model has reached its learning capacity. This metric also helps diagnose overfitting or underfitting when comparing training and validation losses. In the context of adversarial attacks, convergence reflects the resilience of the model. We define poison resilience as successful convergence even with 50% of the participants being attackers.

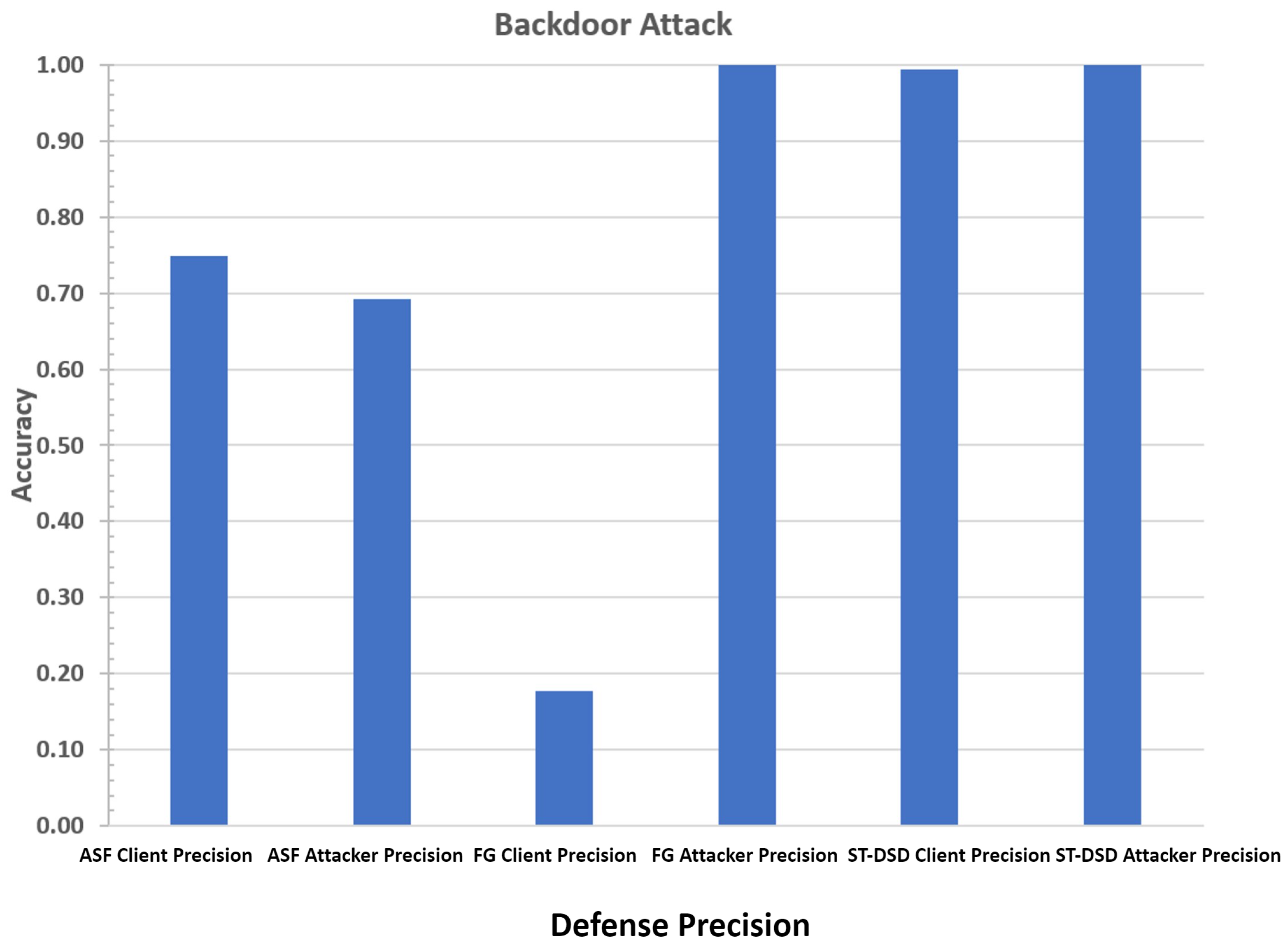

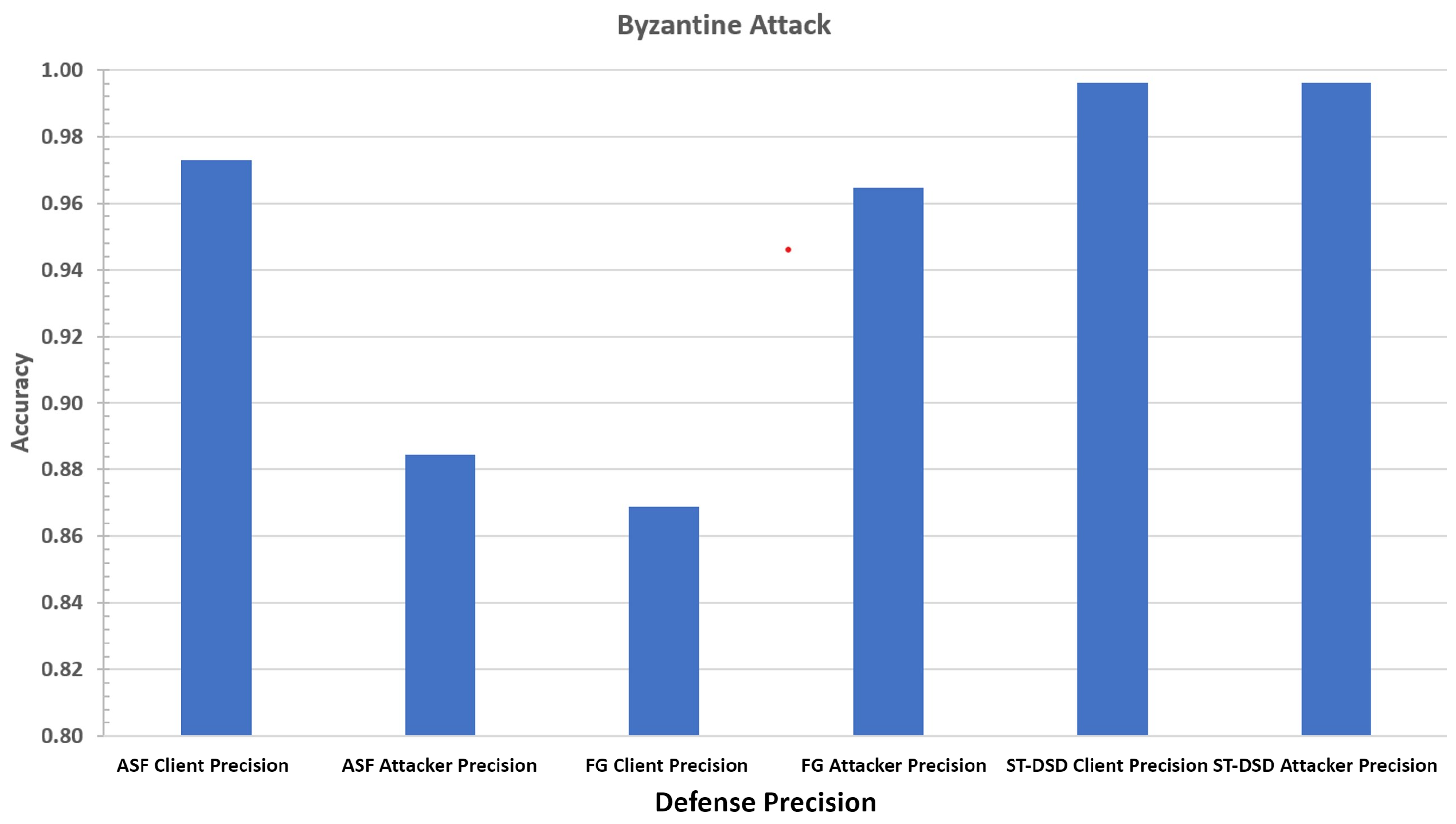

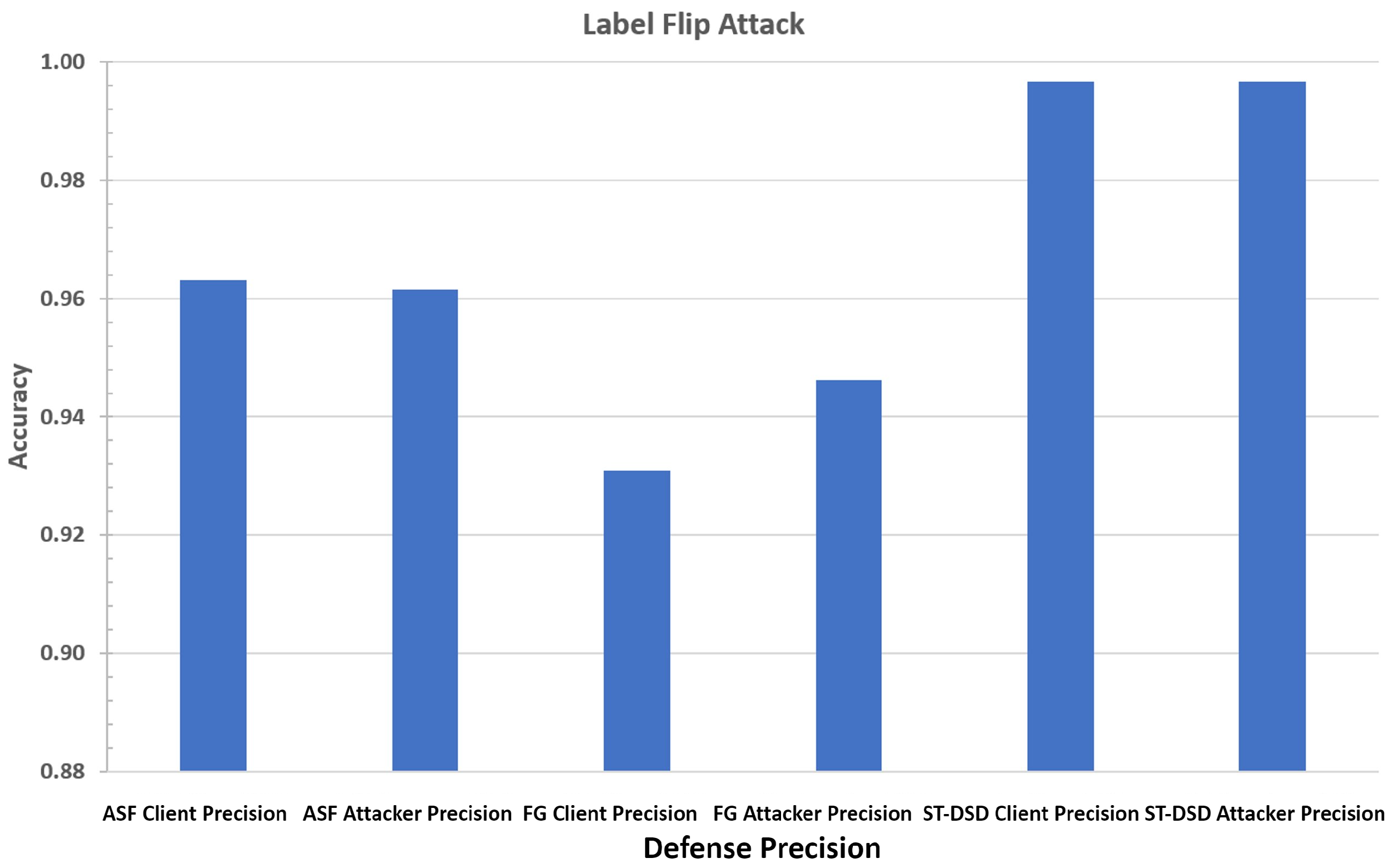

- Precision: We calculate Precision separately for honest clients and poison attackers. Client precision measures the proportion of honest clients correctly identified, while attacker precision measures the proportion of attackers correctly classified. High precision in both categories is critical, as misclassifying honest clients or failing to exclude attackers degrades federated learning performance. This metric helps explain the strengths and weaknesses of each defense mechanism.

- Poison Rate: The poison rate quantifies the percentage of model updates originating from attackers. It differs from the attack rate, which refers to the proportion of attackers in the system. A robust defense may result in a high attack rate but a low poison rate by effectively excluding malicious contributions. Poison rate directly reflects the extent to which an attack influences model performance.

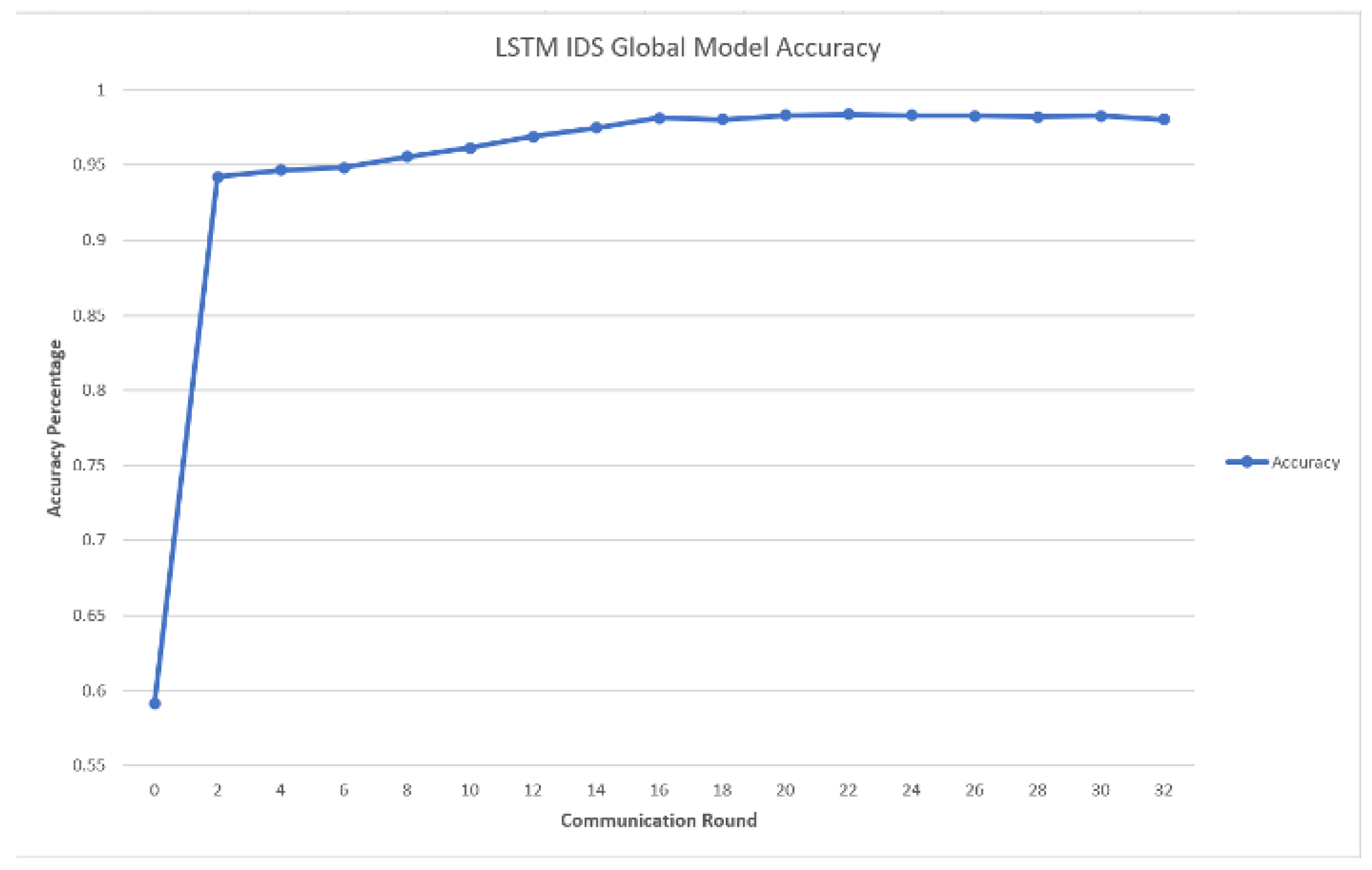

6.2. IDS Baseline Evaluation

6.3. SpaceTime Model Convergence

6.4. Poisoning Attacks

6.5. Model Convergence

6.6. Poison Rate

6.7. Poisoning Defense

7. Conclusions

References

- Konečný, J.; McMahan, H.B.; Ramage, D.; Richtárik, P. Federated Optimization: Distributed Machine Learning for On-Device Intelligence, 2016, [arXiv:cs.LG/1610.02527].

- Saadat, H.; Aboumadi, A.; Mohamed, A.; Erbad, A.; Guizani, M. Hierarchical Federated Learning for Collaborative IDS in IoT Applications. in 2021 10th Mediterranean Conference on Embedded Computing (MECO) 2021, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Anthi, E.; Williams, L.; Slowinska, M.; Theodorakopoulos, G.; Burnap, P. A Supervised Intrusion Detection System for Smart Home IoT Devices. IEEE Internet Things Journal 2019, 6, 9042–9053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, C.; Li, B.; Lu, K.; Song, D. Targeted Backdoor Attacks on Deep Learning Systems Using Data Poisoning, 2017, [arXiv:cs.CR/1712.05526].

- Baracaldo, N.; Chen, B.; Ludwig, H.; Safavi, J.A. Mitigating Poisoning Attacks on Machine Learning Models: A Data Provenance Based Approach. in Proceedings of the 10th ACM Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Security 2017, pp. 103–110. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, H.; Xu, G.; Chen, Z.; Huang, X.; Lu, R. Privacy-Enhanced Federated Learning Against Poisoning Adversaries. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics Security 2021, 16, 4574–4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Blanco-Justicia, A.; Domingo-Ferrer, J.; Sanchez, D.; Rebollo-Monedero, D. Fair Detection of Poisoning Attacks in Federated Learning. in 2020 IEEE 32nd International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (ICTAI) 2020, pp. 224–229. [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Cong, Y.; Dong, J.; Wang, Q.; Lyu, L.; Liu, J. Data Poisoning Attacks on Federated Machine Learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021; 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, B.; Cheng, X.; Binh, H.T.T.; Yu, S. PoisonGAN: Generative Poisoning Attacks Against Federated Learning in Edge Computing Systems. IEEE Internet Things Journal, 2021; 3310, 3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, C.; Yoon, C.J.M.; Beschastnikh, I. Mitigating Sybils in Federated Learning Poisoning. CoRR 2018, abs/1808.04866.

- Lyu, L. Privacy and Robustness in Federated Learning: Attacks and Defenses. http://arxiv.org/abs/2012.06337, 2022. Accessed: May. 04, 2022.

- Gu, Z.; Shi, J.; Yang, Y.; He, L. Defending against Poisoning Attacks in Federated Learning from a Spatial-temporal Perspective. In Proceedings of the 2023 42nd International Symposium on Reliable Distributed Systems (SRDS); 2023; pp. 25–34, ISSN 2575-8462. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, F.; Li, C. Privacy-Preserving Federated Learning Against Label-Flipping Attacks on Non-IID Data. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024, 11, 1241–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Yoon, S. Similarity-based Filtering for Defending Against Malicious Clients in Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData); 2024; pp. 8728–8730, ISSN 2573-2978. [Google Scholar]

- Hammoudeh, Z.; Lowd, D. Simple, Attack-Agnostic Defense Against Targeted Training Set Attacks Using Cosine Similarity. International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML) Workshop, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, C.; Huang, K.; Chen, P.Y.; Li, B. DBA: DISTRIBUTED BACKDOOR ATTACKS AGAINST FEDERATED LEARNING2020. p. 19.

- Heidarian, A.; Dinneen, M.J. A Hybrid Geometric Approach for Measuring Similarity Level Among Documents and Document Clustering. in 2016 IEEE Second International Conference on Big Data Computing Service and Applications (BigDataService) 2016, pp. 142–151.

- Birchman, B.; Thamilarasu, G. Securing Federated Learning: Enhancing Defense Mechanisms against Poisoning Attacks. In Proceedings of the 2024 33rd International Conference on Computer Communications and Networks (ICCCN); 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, C.; Yoon, C.J.M.; Beschastnikh, I. The Limitations of Federated Learning in Sybil Settings. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Symposium on Research in Attacks, Intrusions and Defenses (RAID 2020), San Sebastian; 2020; pp. 301–316. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, P.; Mhamdi, E.M.E.; Guerraoui, R.; Stainer, J. Machine Learning with Adversaries: Byzantine Tolerant Gradient Descent. p. 11.

- Cao, D.; Chang, S.; Lin, Z.; Liu, G.; Sun, D. Understanding Distributed Poisoning Attack in Federated Learning. in 2019 IEEE 25th International Conference on Parallel and Distributed Systems (ICPADS) 2019, pp. 233–239. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chunpeng, G.; Hu, F.; Chen, B. RobustFL: Robust Federated Learning Against Poisoning Attacks in Industrial IoT Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Peng, R.Q.; Wang, J.Q.; Li, Z.; Qu, H.B. NEWLSTM: An Optimized Long Short-Term Memory Language Model for Sequence Prediction. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 65395–65401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Anomaly-Based IoT IDS | ||

|---|---|---|

| Layer Type | Output Shape | Number of Parameters |

| Dense | (None, 256, 256) | 7680 |

| LSTM | (None, 256, 256) | 525,312 |

| Dense | (None, 256, 512) | 131,584 |

| LSTM | (None, 512) | 2,099,200 |

| Dense | (None, 1024) | 525,312 |

| Dense | (None, 1) | 1025 |

| Total | 3,290,113 | |

| IDS Accuracy Impacts from Various Attacks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attack Rate | Byzantine | Label Flip | Backdoor | DBA |

| 5% | 74.5% | 83.3% | 98.3% | 99% |

| 10% | 64.4% | 78.4% | 98.2% | 93.2% |

| 50% | 59.1% | 64.1% | 97.1% | 89.1% |

| Poison Rate Effects on Accuracy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Defense | Attack Rate | Poison Rate | IDS Accuracy |

| FoolsGold | 50 | 33 | 87 |

| Spacetime | 50 | 0 | 96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).