1. Introduction

The language of modern theoretical physics has evolved in tandem with mathematics, from the calculus describing classical mechanics to the differential geometry of general relativity. In recent decades, higher category theory has emerged as a candidate for the grammar of fundamental physics [

1]. It extends the familiar notions of objects and transformations (morphisms) into a multi-layered hierarchy. An

n-category contains objects (0-morphisms), morphisms between them (1-morphisms), 2-morphisms between 1-morphisms, and so on, up to

n-morphisms. The ultimate extension of this "categorical ladder" is the

infinite-dimensional category, or

∞-category, which possesses morphisms at every level [

6].

This sophisticated structure has proven invaluable in fields like algebraic topology, quantum field theory, and string theory, where it models complex path integrals, extended objects, and dualities [

2]. The very success of these applications raises a profound physical question: are

∞-categories merely a convenient mathematical language, or do they represent a structure that can be physically instantiated? In other words, could a physical system—its quantum states, its dynamics, its spacetime geometry—actually

be an

∞-category, in the sense that it faithfully realizes an infinite hierarchy of morphisms as physically distinguishable features?

This paper argues for a negative answer. Our central thesis is that infinite-dimensional categories cannot be physically realized. We contend that the laws of physics, particularly the constraints on information density imposed by quantum gravity, forbid any finite system from possessing an infinite structural depth. Just as a physical object cannot have infinite energy density, we argue that it cannot possess an infinite hierarchy of organizational complexity.

Our argument proceeds as follows. In

Section 2, we review the necessary concepts from higher category theory and introduce the fundamental physical principles of information bounds. In

Section 3, we develop our core thesis by defining what a physical realization of a category entails and examining its information-theoretic cost.

Section 4 crystallizes this reasoning into a formal theorem and proof based on the finite dimensionality of a quantum system’s Hilbert space as implied by the Bekenstein bound. Finally, in

Section 5, we explore the significant implications of our findings for theoretical physics and the philosophy of mathematics, before concluding in

Section 6.

2. Background: Categories and Physical Information

2.1. The Categorical Ladder

A category comprises objects and morphisms. A higher category generalizes this. A 2-category has objects, 1-morphisms between objects, and 2-morphisms between parallel 1-morphisms. An n-category continues this pattern up to n-morphisms. An ∞-category is a structure possessing k-morphisms for all integers .

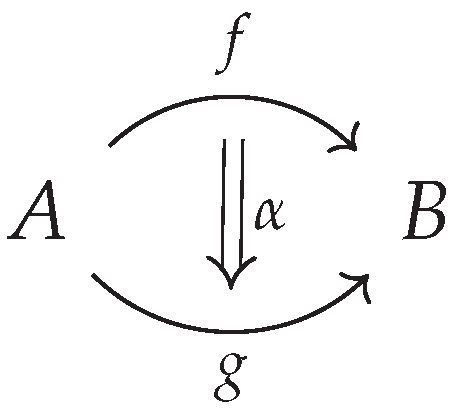

Figure 1.

A 2-morphism between two 1-morphisms f and g. In an ∞-category, this hierarchical structure of "morphisms between morphisms" continues indefinitely.

Figure 1.

A 2-morphism between two 1-morphisms f and g. In an ∞-category, this hierarchical structure of "morphisms between morphisms" continues indefinitely.

Modern mathematics provides several rigorous models for

∞-categories, most prominently the quasi-categories (or simplicial sets satisfying certain lifting properties) of Joyal and Lurie [

6,

7]. Importantly, many complex

∞-categories can be specified finitely, for instance, by a set of generating objects and morphisms along with relations they must satisfy. This distinction between a finite description and the potentially infinite structure it generates is central to our argument.

2.2. Fundamental Bounds on Physical Information

Our argument rests not on heuristic analogies but on fundamental bounds derived from the intersection of general relativity and quantum mechanics. The key principle is the

Holographic Principle, which posits that the information content of any region of space is bounded by its surface area, not its volume [

8,

9].

This principle is given a precise mathematical form by the

Bekenstein bound, which states that the maximum entropy

(and thus the maximum information content

) of any physical system with total energy

E contained within a sphere of radius

R is finite [

3]:

where

is the Boltzmann constant,

ℏ is the reduced Planck constant, and

c is the speed of light. Since information

I is related to entropy by

, this imposes a finite upper limit on the number of bits a system can possibly encode.

In a quantum mechanical context, the entropy of a system is related to the dimensionality of its Hilbert space by . The Bekenstein bound thus implies that for any finite physical system, its Hilbert space must be finite-dimensional. This is a profound constraint: a system in a box cannot have an infinite number of perfectly distinguishable states.

Furthermore, Landauer’s principle connects information to thermodynamics, stating that erasing one bit of information in a system at temperature

T requires dissipating at least

of energy [

5]. This establishes that information is physical, with tangible energetic costs.

3. The Core Argument: The Information Cost of Realization

3.1. Defining a Faithful Physical Realization

Before proving our theorem, we must precisely define what it means for a physical system to "be" a category.

Definition 1 (Faithful Physical Realization). A physical system provides a faithful physical realization of a category if there exists a map Φ from the elements of (objects, morphisms, etc.) to the set of physically distinguishable states or processes of , such that two elements are non-isomorphic if and only if their physical realizations and are physically distinguishable.

"Physically distinguishable" means that there exists, at least in principle, a physical measurement that can differentiate the states with arbitrary reliability. In a quantum system, this implies that the states correspond to nearly orthogonal vectors in its Hilbert space. For our purposes, a set of states is distinguishable if they correspond to a set of mutually orthogonal subspaces.

3.2. The Information Cost of a Morphism

For a higher-categorical structure to be a feature of a physical system, its constituent morphisms must be encoded in the system’s physical state. Consider a -morphism relating two parallel k-morphisms. For to be a non-trivial feature of the system, the state of the system corresponding to the presence of must be distinguishable from the state corresponding to the identity -morphism.

By definition, distinguishing between two states requires at least one bit of information. If a system is a faithful realization of a category, then for every non-isomorphic morphism that exists, the system must "spend" some of its finite information capacity to encode that morphism’s existence and identity.

3.3. Complexity Collapse and the Infinite Hierarchy

Let us assume a system realizes an ∞-category that is not equivalent to any n-category. This means that for any integer n, there exists some for which there are non-trivial k-morphisms. This implies an infinite tower of structural data that must be encoded in the physical state of .

Each level of this tower that contains non-trivial structure requires some amount of information to be specified. The total information content

needed to describe the system’s full categorical structure would be a sum over the information required at each level

k:

where

is the information encoded in the

k-morphisms. If non-trivial, distinguishable morphisms exist for infinitely many levels

k, then

for infinitely many

k, implying the total information content

must be infinite.

This conclusion clashes directly with the Bekenstein bound. A physical system, confined to a finite region with finite energy, has a strictly finite information capacity. It cannot encode the infinite information required to faithfully realize a true ∞-category. We formalize this contradiction in the next section.

4. Formalization: A Theorem on Finite Categorical Order

We now state and prove the central result of this paper.

Theorem 1 (Finite Order of Physical Systems). Let be any physical system contained within a finite spatial volume and possessing a finite total mass-energy. If the structure of constitutes a faithful physical realization of a category , then must be weakly equivalent to an n-category for some finite integer n.

Proof. The proof proceeds by contradiction, grounding the argument in the quantum description of a physical system.

Assumption: Assume the system provides a faithful physical realization of a weak ∞-category, , which is not weakly equivalent to any n-category for finite n.

Implication of the Assumption: The assumption that is not equivalent to any finite n-category implies that for every integer , there exists a level containing at least two parallel k-morphisms, f and g, that are not isomorphic.

Physical Realization in Hilbert Space: According to our definition of faithful physical realization, these non-isomorphic morphisms f and g must correspond to physically distinguishable states of . In the quantum mechanical description of , these distinguishable states are represented by (at least nearly) orthogonal state vectors in the system’s Hilbert space . Let us denote them and . The condition of distinguishability implies . By our assumption in step 2, we can find such pairs of distinguishable states at arbitrarily high categorical levels. This implies the existence of an infinite set of distinguishable physical states corresponding to the infinite hierarchy of non-isomorphic morphisms.

The Bekenstein Bound and Hilbert Space Dimension: The Bekenstein bound states that the entropy

S of the system

is finite, as its radius

R and energy

E are finite. The statistical entropy of a quantum system is given by

, where

is the dimension of its Hilbert space. Since

S is finite,

must also be finite.

Contradiction: In step 3, we concluded that a physical realization of requires an infinite set of distinguishable states. An infinite set of distinguishable (mutually orthogonal) states requires an infinite-dimensional Hilbert space. This directly contradicts the conclusion from step 4 that the Hilbert space of any such physical system must be finite-dimensional.

Therefore, our initial assumption must be false. The category describing the system cannot be a true ∞-category and must be weakly equivalent to an n-category for some finite integer n. □

Remark 1 (On Finite Presentations). This theorem holds even if the ∞-category can be described by a finite set of rules (e.g., generators and relations). The physical constraint is not on the complexity of the abstract description, but on the resources (information capacity, number of available orthogonal states) required to physically instantiate the infinitely many distinct structures that these finite rules can generate. A Turing machine can be finitely described, but it cannot be physically realized if it requires an infinite tape. Similarly, a finitely-presented ∞-category cannot be physically realized if it entails an infinite number of distinguishable states.

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications for Theoretical Physics

Our result does not invalidate the use of ∞-categories in physics but reframes their interpretation. They should be seen as powerful mathematical formalisms for systems with a very high, but finite, categorical dimension, or as idealizations in a certain limit. This is analogous to using the continuum of real numbers to model a fluid, which is ultimately composed of a finite number of discrete atoms. The ‘∞’ in physical applications of ∞-categories should be interpreted as a mathematical convenience for "a number so large that its precise value is irrelevant for the calculation at hand, and where taking the limit simplifies the formalism."

This suggests that at some fundamental level, such as the Planck scale, theories currently formulated with ∞-categories may require a "finitization," where a cutoff on categorical dimension appears.

5.2. Counterarguments and Responses

Emergent Infinities: One might point to emergent infinities in condensed matter physics, such as the infinite correlation length at a second-order phase transition. However, these infinities are artifacts of the thermodynamic limit (assuming an infinite number of particles). Any real, finite physical sample will have a finite, albeit large, correlation length. These models do not describe a system with an infinite structural hierarchy at the level of its fundamental constituents.

Information Compression: Could the information for infinitely many morphisms be compressed into a finite state? Our proof already addresses this. The Bekenstein bound limits the total number of distinguishable states a system can have, regardless of how those states are generated or described. If a "compressed" state could somehow give rise to an infinite hierarchy of observable features, it would imply the system can occupy an infinite number of distinguishable states, which is what the bound forbids.

Potential vs. Actual Morphisms: Another counterargument is that higher morphisms might exist only "potentially" and not contribute to the system’s entropy until actualized. However, in quantum mechanics, the state of a system (e.g., its wavefunction or the Hamiltonian that governs it) must contain all information about its properties, whether measured or not. A potential property not encoded in the present state is merely a statement about possible future evolution, not the system’s current structure. The structure *is* the state.

5.3. Towards a Bound on Categorical Dimension

If a maximal categorical dimension

exists, could it be related to other fundamental constants? The information capacity of a system that has collapsed to a black hole is given by the Bekenstein-Hawking entropy:

, where

A is the event horizon area and

is the Planck length. This corresponds to a maximum number of bits

. If we naively postulate that each categorical level of non-trivial structure requires at least one bit of information, this would imply a very loose upper bound:

For a solar-mass black hole, this number is astronomically large (

), reinforcing why

∞-categories serve as such a good approximation. However, the principle remains that this number, while huge, is finite.

5.4. Philosophical Impact

Our thesis suggests a form of "physical finitism": the universe is finite not only in resources but also in its organizational or descriptive complexity. The Platonic realm of mathematics may contain infinite structures, but the physical world can only ever realize finite approximations. This imposes a fundamental limit on the resolution at which reality can be described—not just spatially (the Planck length) and energetically (the Planck energy), but also organizationally.

6. Conclusion

We have argued that infinite-dimensional categories, while extraordinarily powerful mathematical tools, cannot be faithfully realized by physical systems. The argument, formalized in a theorem, demonstrates that the infinite information content required to instantiate an infinite hierarchy of distinguishable morphisms is in direct violation of the Bekenstein bound, a fundamental limit on the information capacity of any finite region of space with finite energy. Our proof hinges on the fact that this bound necessitates a finite-dimensional Hilbert space for any physical system, which cannot accommodate the infinite number of distinguishable states required.

This conclusion reframes the role of ∞-categories in physics as highly effective idealizations rather than literal descriptions of reality. It suggests that physical reality is "finitary" in its structural depth.

Future research could proceed along several exciting paths. A primary goal would be to refine the speculative bound on the maximal categorical dimension, , connecting it more rigorously to theories of quantum gravity. Another avenue is to re-examine physical theories that currently use ∞-categories, such as topological quantum field theory or string theory, to identify if and how a "categorical cutoff" at some large but finite n would manifest as new physical predictions. Finally, the philosophical implications of a finitistic universe—one bounded in its organizational complexity—warrant deeper investigation, connecting the limits of physics to the limits of computation and knowledge itself.

References

- Baez, J.C.; Dolan, J. Higher-dimensional algebra and topological quantum field theory. Journal of Mathematical Physics 1995, 36, 6073–6105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baez, J.C.; Lauda, A.D. A prehistory of n-categorical physics. In Deep beauty: Mathematical innovation and the search for an underlying harmony in the sciences; Carnegie, D., Ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bekenstein, J.D. Universal upper bound on the entropy-to-energy ratio for bounded systems. Physical Review D 1981, 23, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousso, R. The holographic principle. Reviews of Modern Physics 2002, 74, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landauer, R. Irreversibility and heat generation in the computing process. IBM Journal of Research and Development 1961, 5, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurie, J. Higher Topos Theory; Annals of Mathematics Studies; Princeton University Press, 2009; Volume 170. [Google Scholar]

- Riehl, E. Categorical Homotopy Theory; Cambridge University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Susskind, L. The world as a hologram. Journal of Mathematical Physics 1995, 36, 6377–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ’t Hooft, G. Dimensional reduction in quantum gravity. arXiv 1993, arXiv:gr-qc/9310026. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, G.A. The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review 1956, 63, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogata, K. Modern Control Engineering, 5th ed; Prentice Hall, 2010. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).