1. Introduction

As a field of pure mathematics, category theory emerged in the mid-20th century with the work of Eilenberg and Mac Lane on group theory and algebraic topology [

1,

2], as well as the work of Serre and Grothendieck in the closely related area of homological algebra [

3,

4]. When conceived as an alternative foundation for mathematics (as exemplified by work on

elementary topos theory within mathematical logic [

5,

6]), the shift from set theory to category theory necessitates a certain shift in philosophical perspective, wherein one transitions away from identifying mathematical objects based upon their internal structure (such as in Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory, where the axiom of extensionality defines set equality based purely upon the set membership relation [

7]), and towards identifying mathematical objects based upon their relationships to other objects of the same “type” (as exemplified by the Yoneda lemma, arguably the most fundamental result in category theory [

8]). This more

relational perspective on the nature of structure turns out to be a useful lens through which to view many fields, including many outside of mathematics altogether. For instance, in the foundations of quantum mechanics, moving from set-theoretic to category-theoretic foundations inevitably changes one’s view from quantum systems and their states as being the fundamental objects of study (as in the traditional Dirac-von Neumann axioms of quantum mechanics, represented in terms of operator theory on Hilbert space [

9,

10]) to quantum processes and their compositions as being the fundamental objects of study (as in the categorical quantum mechanics formalism of Abramsky and Coecke [

11,

12], later developed into a fully diagrammatic theory of quantum information by Coecke and Duncan [

13,

14]). Likewise, in computer science, one is able to move from a set-theoretic view in which program state is treated as fundamental (as in the Turing machine picture of computation, and as exemplified by the imperative programming paradigm) to a category-theoretic view in which functions and their compositions are treated as fundamental (as in the

-calculus picture of computation, and as exemplified by the functional programming paradigm). Such process-theoretic models, in which processes and their algebra of composition are treated on a fundamentally “higher” footing than states and their internal structure, have also proved useful and/or instructive for the foundations of natural language processing [

15], cybernetics [

16], machine learning [

17], complex networks and control theory [

18,

19], computational complexity theory [

20] (based on prior work on computational irreducibility [

21]), database systems [

22], and many other domains of knowledge. This general process of applying foundational methods and concepts from category theory to fields outside of pure mathematics has come to be known as

applied category theory, [

23].

With the advent and maturation of so many fruitful domains of applied category theory, many software tools have now been developed to facilitate working with category-theoretic data structures in an automated or semi-automated fashion, such as

CATLAB.JL [

24], built on top of the Julia programming language, which uses the formalism of generalized algebraic theories and dependent types to facilitate automated algebraic manipulation of certain fundamental data structures such as operads and symmetric monoidal categories. There are also many examples of diagrammatic proof assistants, such as the highly general QUANTOMATIC [

25] and CARTOGRAPHER [

26] frameworks, or the more specialized PYZX framework [

27], which facilitate the automated rewriting of string diagrams in symmetric monoidal category theory (with, in the latter case, a particular emphasis on diagrammatic quantum information theory). There are even projects, such as the ANR

COREACT project, which aim to formalize certain key aspects of applied category theory, such as compositional/categorical rewriting theory, within existing proof assistant frameworks such as COQ. The aim of the present article is to introduce another such software framework, known as CATEGORICA, which is written principally in the Wolfram Language and is designed to be fully integrated into the Mathematica software system, and which seeks to combine many of the computational algebraic capabilities of existing frameworks such as

CATLAB with many of the diagrammatic theorem-proving capabilities of frameworks such as QUANTOMATIC. At its core, the CATEGORICA framework consists of a unified collection of advanced symbolic and diagrammatic algorithms for efficiently converting between purely algebraic representations of categories, diagrams, functors and other key category-theoretic constructions (by employing an entirely presentation-theoretic view of categories, with arrows within an underlying quiver acting as generators, composition acting as the fundamental binary operation, and algebraic equivalences between objects and morphisms acting as relations) and purely graph-theoretic/combinatorial representations of the very same structures (by employing a description of quivers, categories and functors in terms of graphs, hypergraphs and combinatorial rewriting systems). In this manner, CATEGORICA is able to combine the features of a diagrammatic theorem-prover, a higher-order (equational) logic theorem prover, a (hyper)graph rewriting framework, and an abstract computer algebra system, all in an entirely seamless fashion, automatically adopting the most appropriate algorithmic approach and most efficient concrete data structures for any particular problem, and then converting the result back into the desired abstract representation at the end.

The first in this series of two articles introducing the design of CATEGORICA will focus primarily on the core algebraic structures of the framework (with a particular emphasis on CATEGORICA’s representation and handling of quivers, categories, functors and natural transformations), some simple diagrammatic theorem-proving capabilities (such as CATEGORICA’s ability to derive and prove necessary and sufficient algebraic conditions for diagrams to commute, for categories to be groupoids, for functors to be faithful, etc.), as well as some more advanced abstract algebraic capabilities (such as the computation of retractions and sections, epimorphisms and monomorphisms, initial and terminal objects, constant and coconstant morphisms, injectivity/surjectivity of functors on both objects and morphisms, and even some simple cases of Grothendieck fibrations). The forthcoming second article in the series will focus upon the extension of these capabilities to the handling of universal properties (especially products and coproducts, pullbacks and pushouts, and limits and colimits), including illustrations both of how to prove theorems using them, and of how to perform algebraic computations involving them, as well as the applications of these methods to the handling of (strict, symmetric) monoidal categories, including capabilities for string diagram representation, manipulation and rewriting. CATEGORICA’s core algorithmic framework is based on the hypergraph rewriting/Wolfram model formalism outlined within [

28,

29,

30], which may be augmented with basic techniques from the theory of graph grammars, and algebraic/compositional graph rewriting theory [

31,

32] (and, in particular, the theory of

double-pushout rewriting [

33]) in order to develop a highly efficient (hyper)graphical/diagrammatic theorem-proving system [

34,

35,

36]. We begin in

Section 2 by introducing the fundamental data structure underlying all abstract category-theoretic objects in CATEGORICA, namely the abstract

quiver (a directed multigraph whose vertices are

objects and whose edges are

arrows), and we show how an

AbstractQuiver object in CATEGORICA may be used in order to “freely generate” a corresponding

AbstractCategory object by allowing for certain arrows to be composed (at which point they become

morphisms), as well as introducing identity morphisms for each object, in a manner that is consistent with both associativity and identity axioms. We demonstrate how CATEGORICA is able to keep track of all necessary algebraic equivalences between morphisms (as necessitated by the underlying axioms of category theory) automatically, as well as how new algebraic relations between objects and arrows/morphisms may be introduced, in order to construct more general examples

non-free categories. We also highlight a very simple application of CATEGORICA’s automated theorem-proving capabilities, by proving that certain categorical diagrams

commute (i.e. that, within certain categories, all directed paths yield the same morphism up to algebraic equivalence), and by automatically computing both necessary and sufficient algebraic conditions to force non-commuting categorical diagrams to commute, using the

AbstractCategory function.

In

Section 3, we proceed to show some examples of simple algebraic computations that can be performed using the

AbstractCategory function, such as the computation of monomorphisms, epimorphisms and bimorphisms (i.e. the category-theoretic generalizations of injective, surjective and bijective functions in mathematical analysis), and the computation of sections, retractions and isomorphisms (i.e. the category-theoretic generalizations of left-invertible, right-invertible and invertible elements in abstract algebra). We introduce a special kind of category known as a

groupoid, in which all morphisms are isomorphisms, and we show how CATEGORICA’s automated theorem-proving capabilities can again be used in order to prove that certain

AbstractCategory objects are or are not groupoids, and indeed to compute necessary and sufficient algebraic conditions (whenever they exist) to force non-groupoidal

AbstractCategory objects to become groupoidal. The relationships between monomorphisms vs. epimorphisms and retractions vs. sections are both examples of a far more general category-theoretic notion of

duality: the

dual of a particular construction can be obtained by simply reversing the direction of morphisms, and therefore reversing the order in which morphisms are composed. CATEGORICA has in-built functionality (via the

“DualCategory” property in particular) for making the systematic exploration of category-theoretic dualities completely straightforward, and we illustrate this by investigating some other common examples of dual constructions using CATEGORICA, including initial vs. terminal objects (i.e. the category-theoretic generalizations of bottom and top elements in partially ordered sets), strict initial vs. strict terminal objects (i.e. initial and terminal objects whose incoming/outgoing morphisms are all isomorphisms), and constant vs. coconstant morphisms (i.e. the category-theoretic generalizations of constant functions and zero-maps in mathematical analysis). In

Section 4, we move on to explore functors (i.e. homomorphisms/structure-preserving maps between categories) using the

AbstractFunctor function, demonstrating CATEGORICA’s capabilities for handling both covariant and contravariant functors (i.e. functors in which morphism directions are preserved and reversed, respectively). We illustrate how CATEGORICA is able to distinguish between different notions of injectivity, surjectivity and bijectivity for

AbstractFunctor objects, including injectivity, surjectivity and bijectivity on objects; essential injectivity, essential surjectivity and essential bijectivity (i.e. injectivity, surjectivity and bijectivity on objects, but only up to isomorphism); and faithfulness, fullness and full faithfulness (i.e. injectivity, surjectivity and bijectivity on

morphisms). We also show CATEGORICA may be used to investigate an important class of functors known as Grothendieck fibrations (i.e. the category-theoretic generalizations of fiber bundles in topology) from a total category to a base category, including special cases such as discrete fibrations (i.e. Grothendieck fibrations in which the fiber categories are all discrete categories containing only objects and identity morphisms).

Finally, in

Section 5, we introduce the

AbstractNaturalTransformation function, allowing one to represent arbitrary natural transformations between

AbstractFunctor objects in CATEGORICA, and showcase its ability to compute (and prove) both necessary and sufficient algebraic conditions to force transformations between functors to be natural. We demonstrate furthermore how the

AbstractNaturalTransformation framework may be used to detect natural isomorphisms between both objects and functors in a highly general way. We also include a short note regarding some of the internal algorithmic details of the CATEGORICA system, and, in particular, its use of double-pushout rewriting formalism and compositional graph rewriting theory to reduce abstract algebraic and diagrammatic reasoning problems to concrete (hyper)graph rewriting problems. We conclude in

Section 6 with a summary of directions for future research and development. The majority of the core CATEGORICA functionality presented within this article, and its forthcoming companion article, has been fully documented and exposed via the

Wolfram Function Repository, including functions such as

AbstractQuiver,

AbstractCategory,

AbstractFunctor,

AbstractProduct,

AbstractCoproduct,

AbstractPullback,

AbstractPushout and

AbstractStrictMonoidalCategory. However, there is also a significant amount of functionality that has not yet been documented and/or exposed, but which is nevertheless available through the CATEGORICA

GitHub Repository (with the overall framework currently consisting of over 20,000 lines of symbolic, high-level Wolfram Language code). All explicit examples of categories

presented within this article are

small, in the sense that the object sets

and morphism sets

are both actually sets, rather than proper classes. Indeed, the only categories currently supported explicitly by CATEGORICA are strictly

finite, which enables us to bypass any considerations of set-theoretic foundations.

2. Quivers, Categories and Diagrams

Every category represented within the CATEGORICA framework has, as its underlying “skeleton”, a directed multigraph called a

quiver (i.e. a collection of vertices called

objects, connected by directed edges called

arrows, which can have arbitrary multiplicity). One important terminological convention that is enforced consistently throughout the CATEGORICA framework is that the directed edges in a quiver are always known as

arrows, whereas the directed edges in the corresponding category that is generated by that quiver (potentially freely, potentially with additional algebraic structure) are always known as

morphisms. By and large, most conventions regarding the notation and nomenclature used within the CATEGORICA framework have been chosen to reflect the conventions set within Mac Lane’s classic treatise on the subject [

38]. If

is an arbitrary quiver, then we shall denote the set of objects/nodes in

by

, and the set of directed edges/arrows in

by

. The rules for how to generate a category

(whose set of objects is denoted

and whose set of morphisms is denoted

, by analogy to sets of homomorphisms in abstract algebra) from the underlying quiver

are then very straightforward: firstly, for every object

X or arrow

in the quiver

, there is a corresponding object

X or morphism

in the category

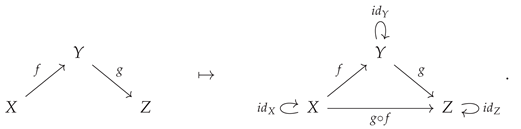

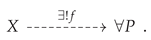

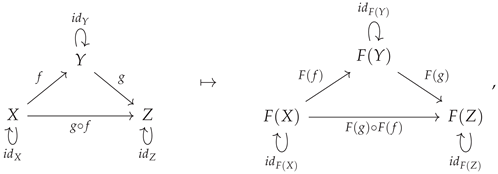

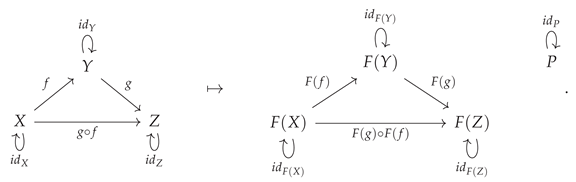

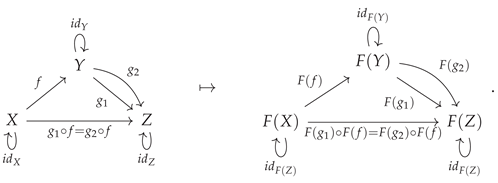

:

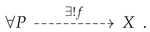

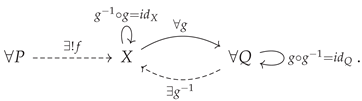

secondly, for every object

X in the quiver

, there exists a corresponding morphism

in the category

mapping that object to itself:

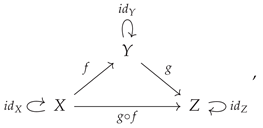

and, thirdly, for every pair of morphisms

and

in the category

where the

codomain of the first morphism matches the

domain of the second, i.e.

(in this case, for instance, the domain of the arrow/morphism

is

X, i.e.

, and its codomain is

Y, i.e.

), there exists a third morphism

mapping from the domain of the first morphism to the codomain of the second:

or, slightly more abstractly (omitting the arbitrary object labels

X,

Y and

Z):

The resulting category

is known as the

free category generated by the quiver

(with the arrows of

acting as the generators, in the algebraic sense, of the morphisms of

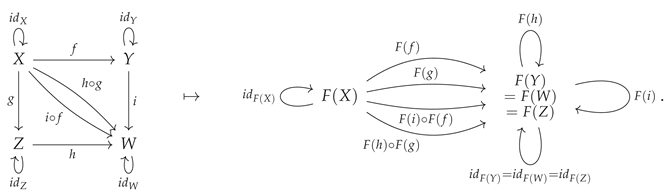

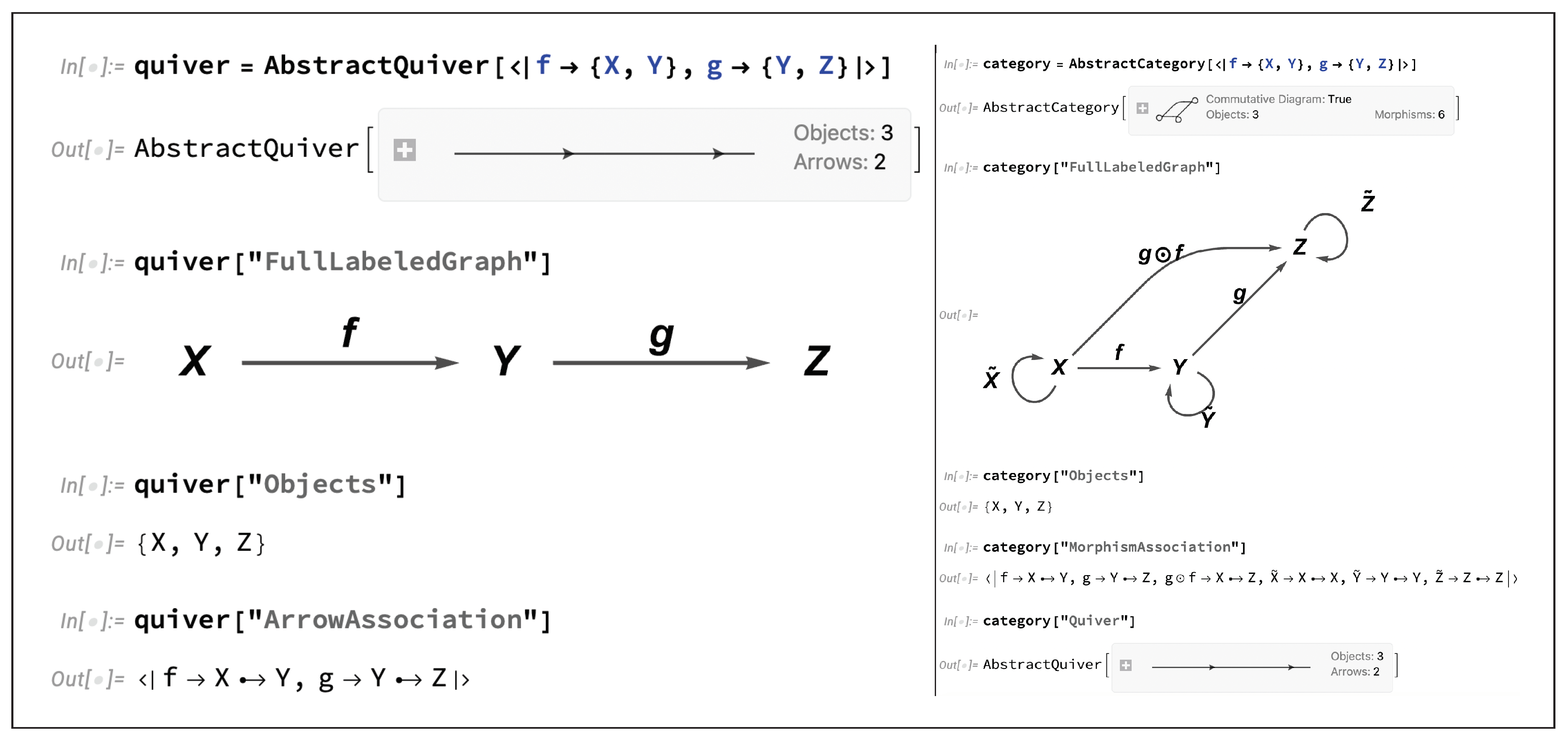

). This construction can be illustrated diagrammatically by means of the following minimal example:

As shown in

Figure 1, the

AbstractQuiver and

AbstractCategory functions in CATEGORICA allow one to represent arbitrary (finite) quivers and categories within the language, with both quivers and free categories being represented internally as lists of objects and associations of arrows/morphisms between those objects (which are then trivially interconvertible with the corresponding combinatorial representations of these structures as labeled directed graphs); every

AbstractCategory object comes equipped with an associated

AbstractQuiver object representing its underlying “skeletal” structure.

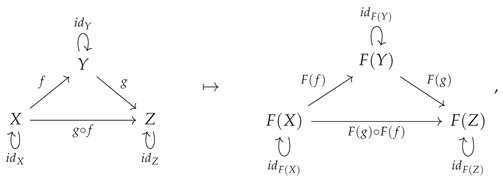

Within the construction of the free category

described above, the morphisms

that were introduced for each object

X are known as

identity morphisms on

X, and the abstract binary operation:

that appears in the definition of the morphism

is known as the

composition operation (such that the resulting morphism

may be referred to as the

composition of morphisms

and

). The identity morphisms

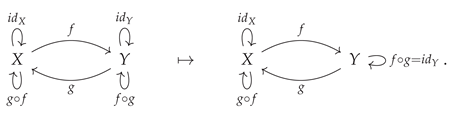

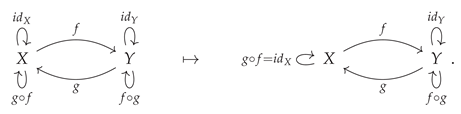

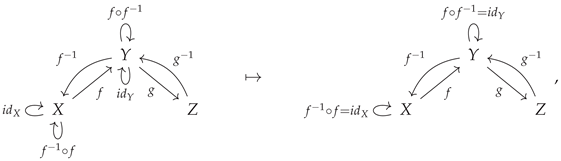

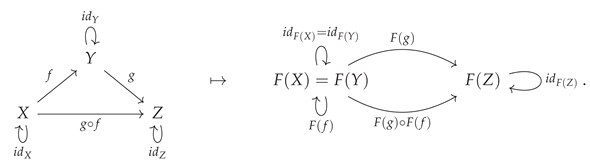

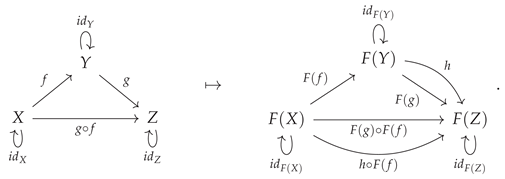

must satisfy the requisite axioms to act as both left and right identities under the operation of morphism composition, such that if

is a morphism in the category

, then

should be the same as

(i.e.

acts as a right identity on

f):

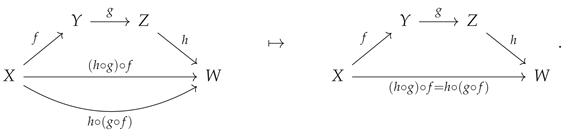

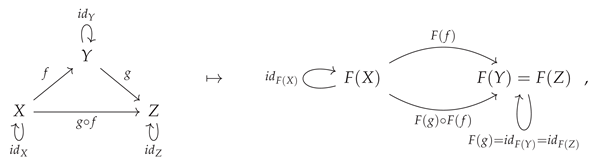

or, illustrated diagrammatically:

and, similarly,

should be the same as

(i.e.

acts as a left identity on

f):

or, illustrated diagrammatically:

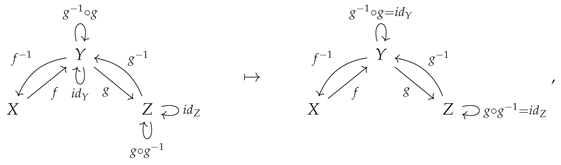

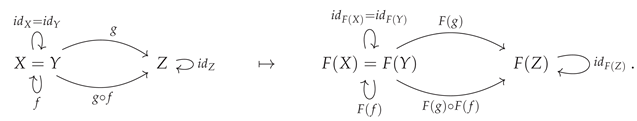

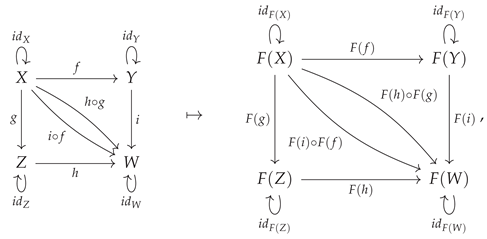

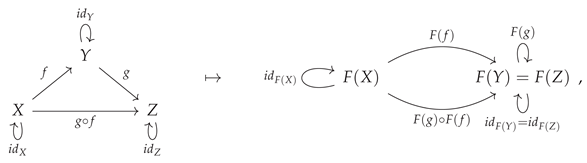

Additionally, the operation of morphism composition itself must satisfy the axiom of associativity, such that if

,

and

form a set of three composable morphisms in the category

, then the composition

should be the same as the composition

:

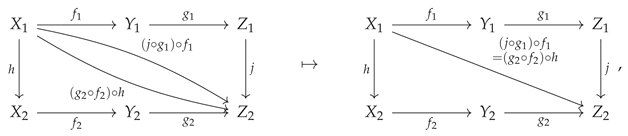

or, illustrated diagrammatically:

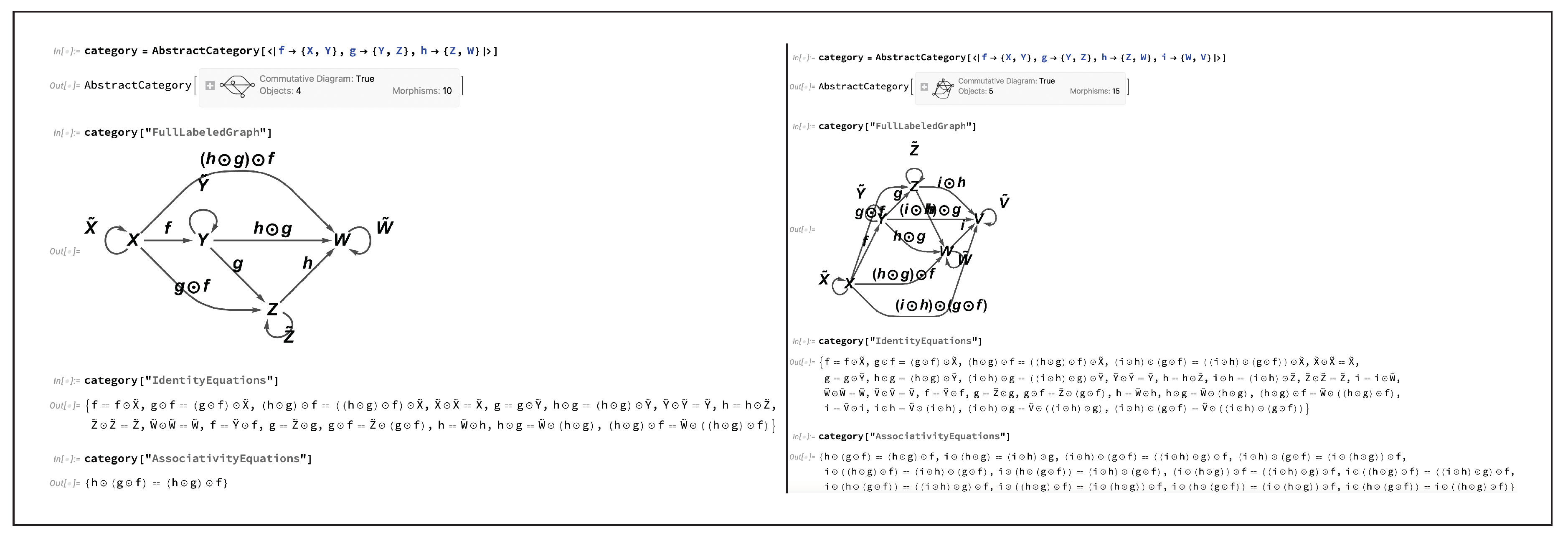

CATEGORICA automatically keeps track of all algebraic equivalences between morphisms that must be imposed in order to maintain consistency with these identity and associativity axioms, as shown in

Figure 2 for the case of two relatively simple

AbstractCategory objects. Note that the

CircleDot[ ⋯ ] and

OverTilde[ ⋯ ] representations of the composition operation ∘ and the identity morphisms

, respectively, are simply the defaults chosen by CATEGORICA, and can be overridden simply by passing additional arguments to

AbstractCategory.

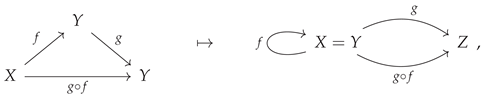

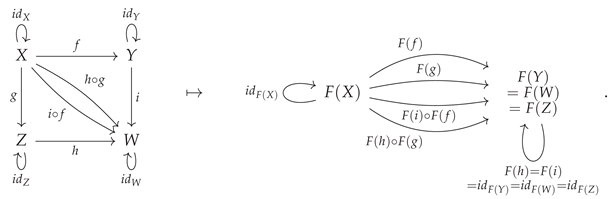

Although we have considered only

free categories so far, it is also possible to construct non-free categories which possess additional algebraic structure in the form of additional equivalences between their objects and morphisms (beyond simply the minimal algebraic equivalences necessitated by the axioms of category theory). For instance, we could consider imposing the equivalence

between objects

X and

Y in the following simple category:

or the equivalence

between morphisms

and

in the following, slightly different, simple category:

Note that we are only permitted to impose algebraic equivalences between morphisms whose domains and codomains both match, i.e., abstractly, using the functions

and

introduced above, we have:

Note also that an algebraic equivalence between morphisms, such as

in the above, will, in general, automatically imply other algebraic equivalences between morphisms, such as:

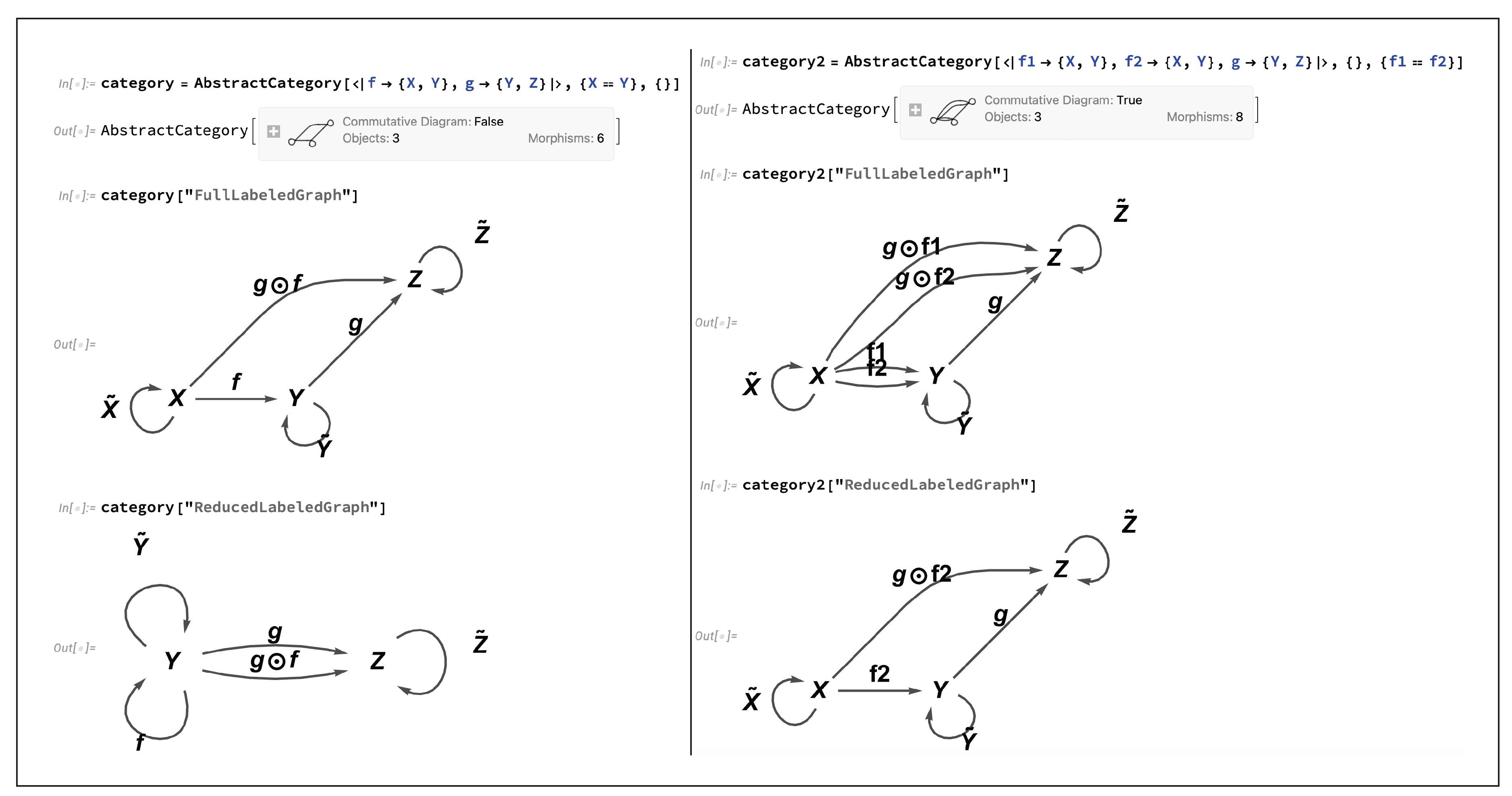

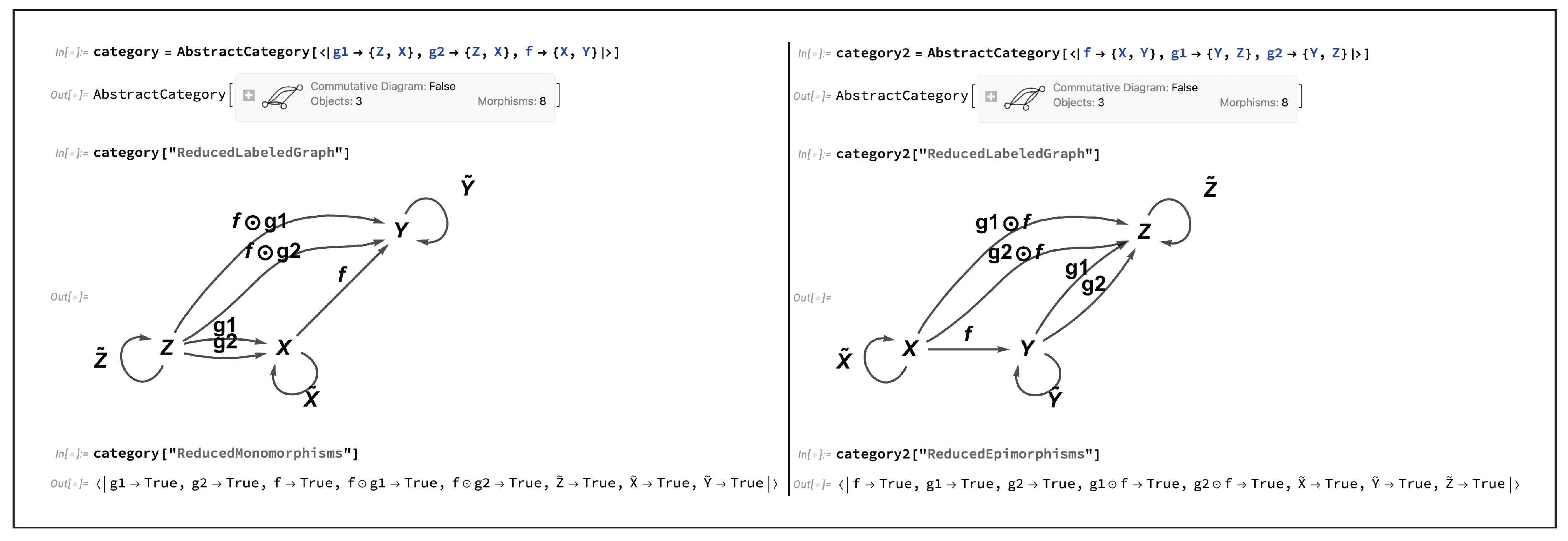

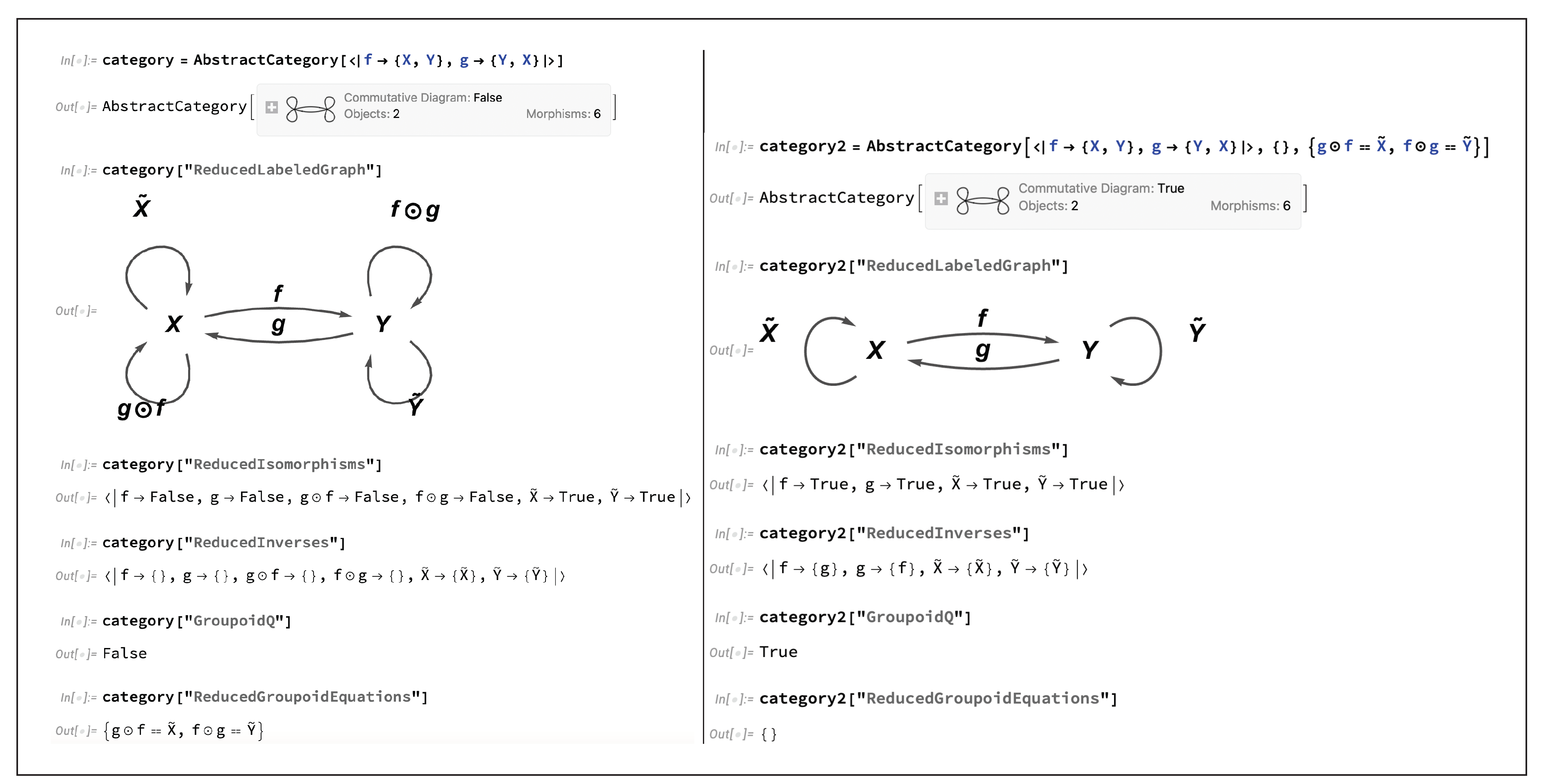

as shown in the corresponding diagram, although in this particular case the converse does not necessarily hold, as we shall see in more detail later. In

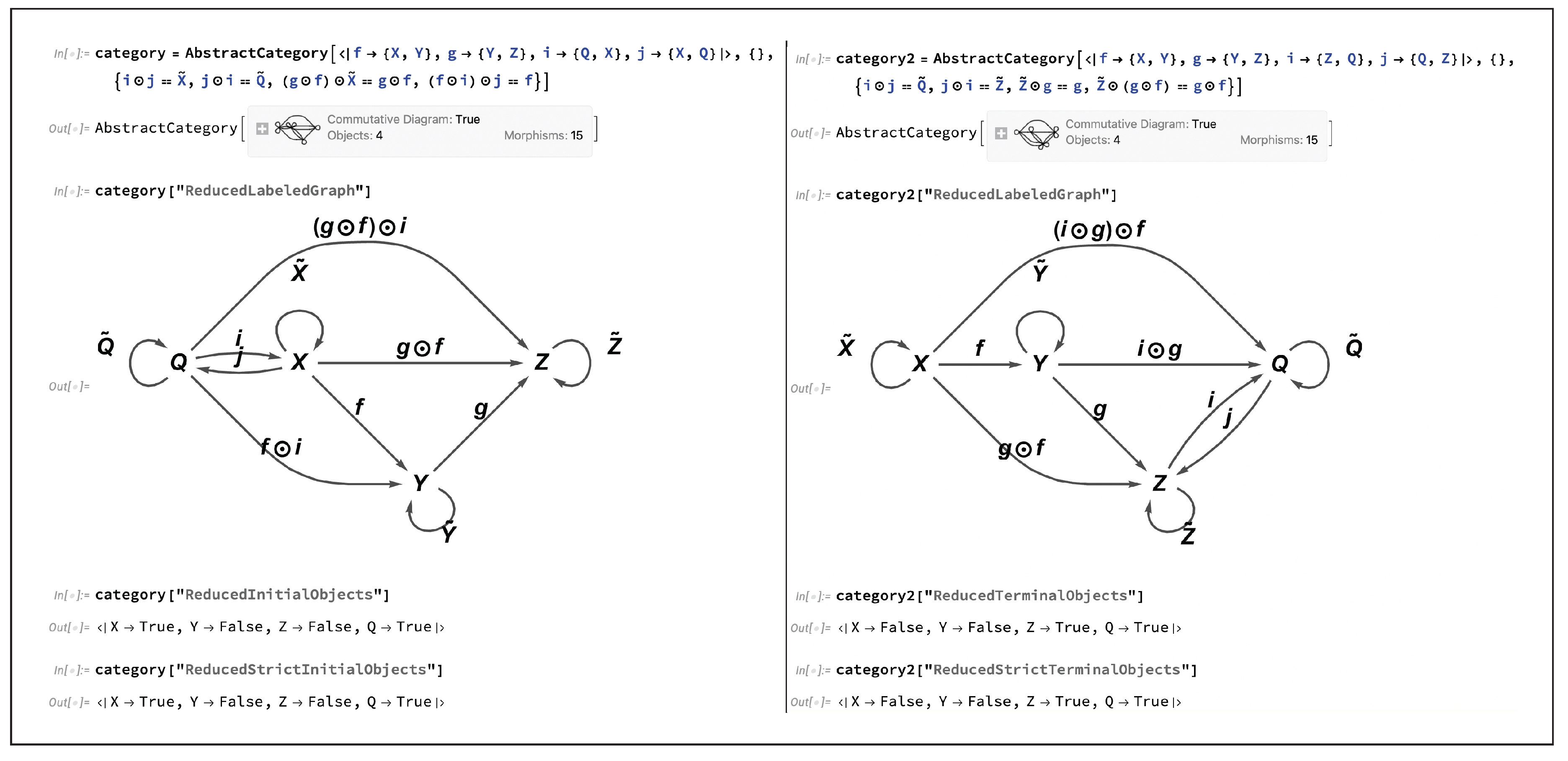

Figure 3, we see the

AbstractCategory objects corresponding to the two examples presented above (with object equivalence

and morphism equivalence

specified, respectively), showing the directed graph representations of the corresponding categories both with and without algebraic equivalences imposed. One of the general design principles of CATEGORICA is that the keyword

“Reduced” within property names such as

“ReducedLabeledGraph” is used to indicate that all known algebraic equivalences should be applied (as opposed to the keyword

“Full” within property names such as

“FullLabeledGraph”, which is used to indicate that no algebraic equivalences should be applied, and that the full, “maximally-unreduced” algebraic structure should be presented instead). There is also a related keyword

“Simple” (as in the property name

“SimpleLabeledGraph”), which can be used to remove all self-loops and multi-edges from the corresponding directed graph representation of any quiver, category, functor, etc. (for instance in order to yield a more presentable form of a particular diagrammatic representation, of the kind that might be shown within an academic paper). Although this automatic simplification feature is frequently very useful when performing practical diagrammatic manipulations, since the purpose of the present article is to be completely explicit and to illustrate (in as much detail as necessary) the underlying design and algorithmic underpinnings of the CATEGORICA framework, we shall not make use of it here.

One of the most common applications of non-free categories and algebraic equivalences between morphisms, occurring throughout many fields of mathematics (and especially in abstract and homological algebra), is the formal treatment of

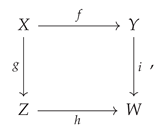

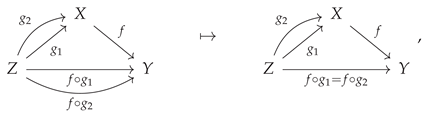

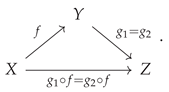

commutative diagrams. Indeed, it is often said that commutative diagrams play the same role in category theory and abstract/homological algebra that equations play in more elementary algebra. For instance, when one says that the following diagram

commutes:

one is effectively imposing the following equivalence between morphisms:

or, in diagrammatic form, one has:

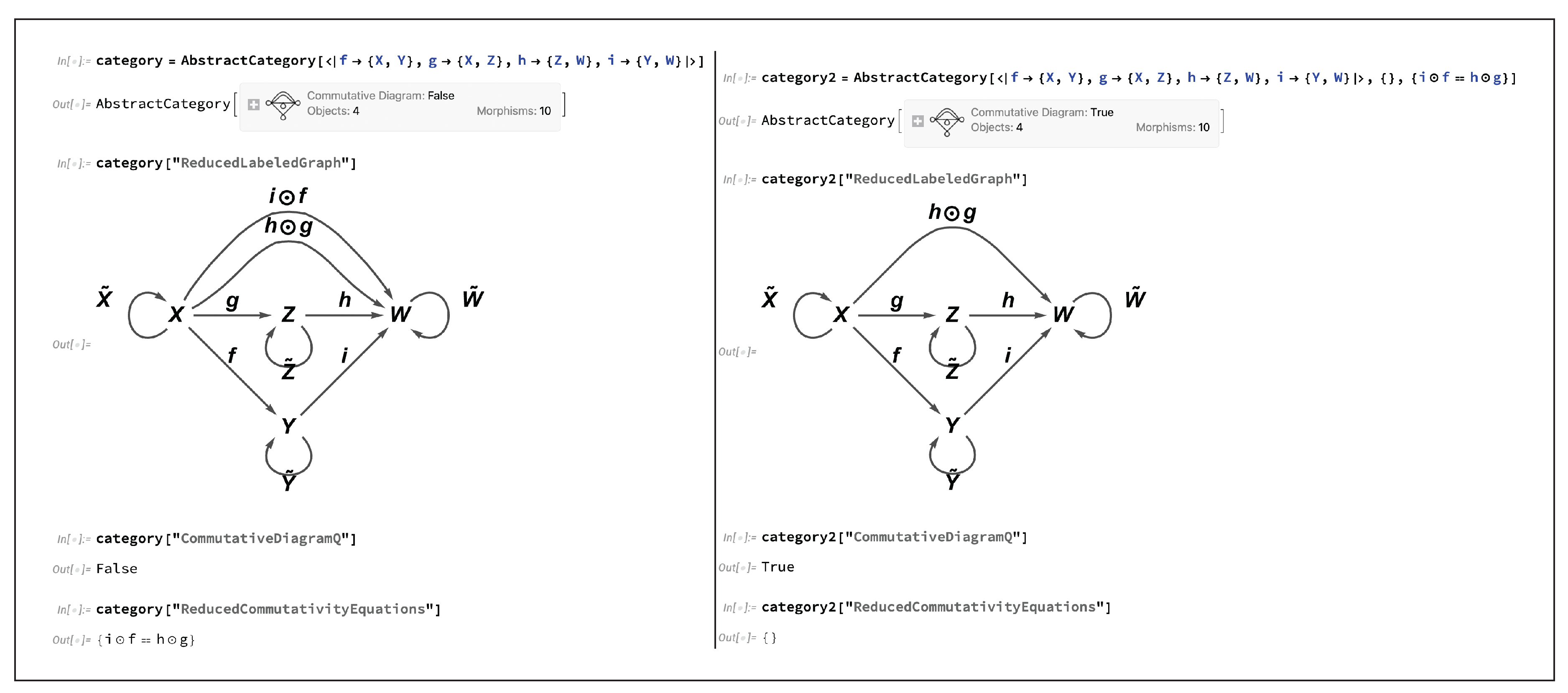

This condition of commutativity of diagrams may thus be characterized purely combinatorially, namely as the condition that all directed paths through the labeled graph representation of the associated category yield the same morphism (up to algebraic equivalence). CATEGORICA is hence able to fall back to using purely graph-theoretic search algorithms in order to compute the minimum set of morphism equivalences necessary to force this diagram to commute, as well as to prove that these equivalences are indeed sufficient, as shown in

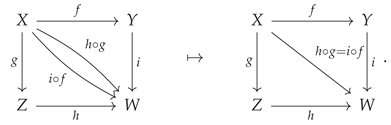

Figure 4. However, although the case of a commutative square is very straightforward, it does not take long before this method of

diagram chasing becomes essentially unmanageable for a human algebraist to enact in full detail; for instance, even upon considering the next obvious case, namely a commutative

oblong of the form:

things have already become quite a bit trickier to analyze than they were for the commutative square, since one not only needs to force the two interior squares to commute:

i.e:

but one must also somehow take care of the commutativity of the outer rectangle:

i.e:

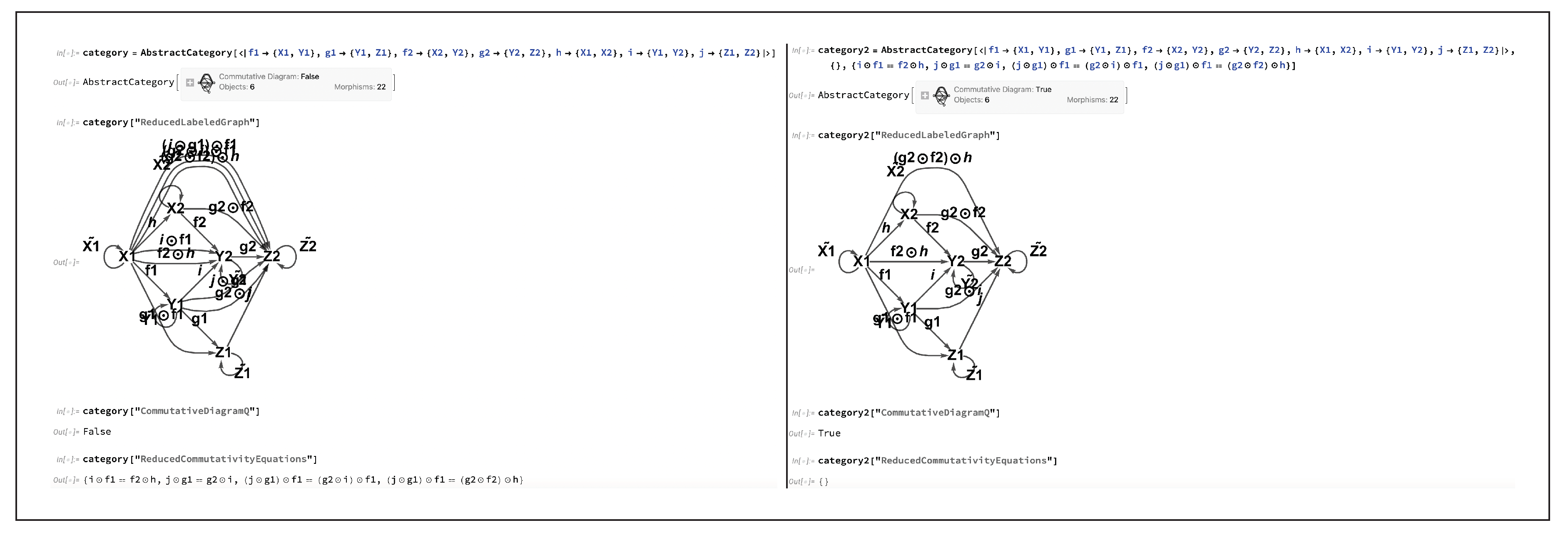

Nevertheless, despite the additional complexity, CATEGORICA is able to handle this case (and, indeed, the case of much larger and more complicated diagrams) in much the same way, as demonstrated in

Figure 5. A fully rigorous definition and treatment of categorical diagrams necessitates the introduction of a certain functor defined over

index categories (or

schemes), which we shall revisit following our introduction to CATEGORICA’s handling of abstract functor objects in

Section 4. Note that

AbstractQuiver objects in CATEGORICA may also carry algebraic equivalence information on both objects and arrows: these equivalences are then translated into corresponding algebraic equivalences on objects and

morphisms upon promotion of the quiver to a full

AbstractCategory object via the pipeline outlined above.

3. Monos, Epis, Retractions and Sections: The Case of Groupoids

The category-theoretic analog of an injective function in mathematical analysis is a

monomorphism [

39,

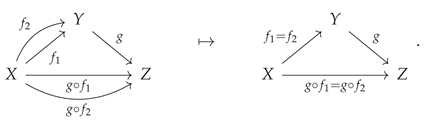

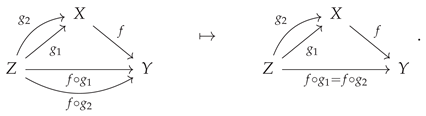

40]: a left-cancellative morphism. Specifically, if the morphism

in the category

is such that, for all objects

Z and all pairs of morphisms

and

such that

, one is able to “cancel on the left” by

to obtain that

, then

is a monomorphism:

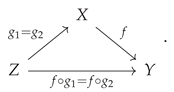

or, illustrated diagrammatically, one has that if:

then one also necessarily has:

The corresponding

dual notion to that of a monomorphism (i.e. the construction obtained by reversing the direction of the morphisms, and hence reversing the order of morphism composition, in the diagrams shown above) is that of an

epimorphism: a right-cancellative morphism, and hence the category-theoretic analog of a surjective function in analysis. Specifically, if the morphism

in the category

is such that, for all objects

Z and all pairs of morphisms

and

such that

, one is able to “cancel on the right” by

to obtain that

, then

is an epimorphism:

or, illustrated diagrammatically, one has that if:

then one also necessarily has:

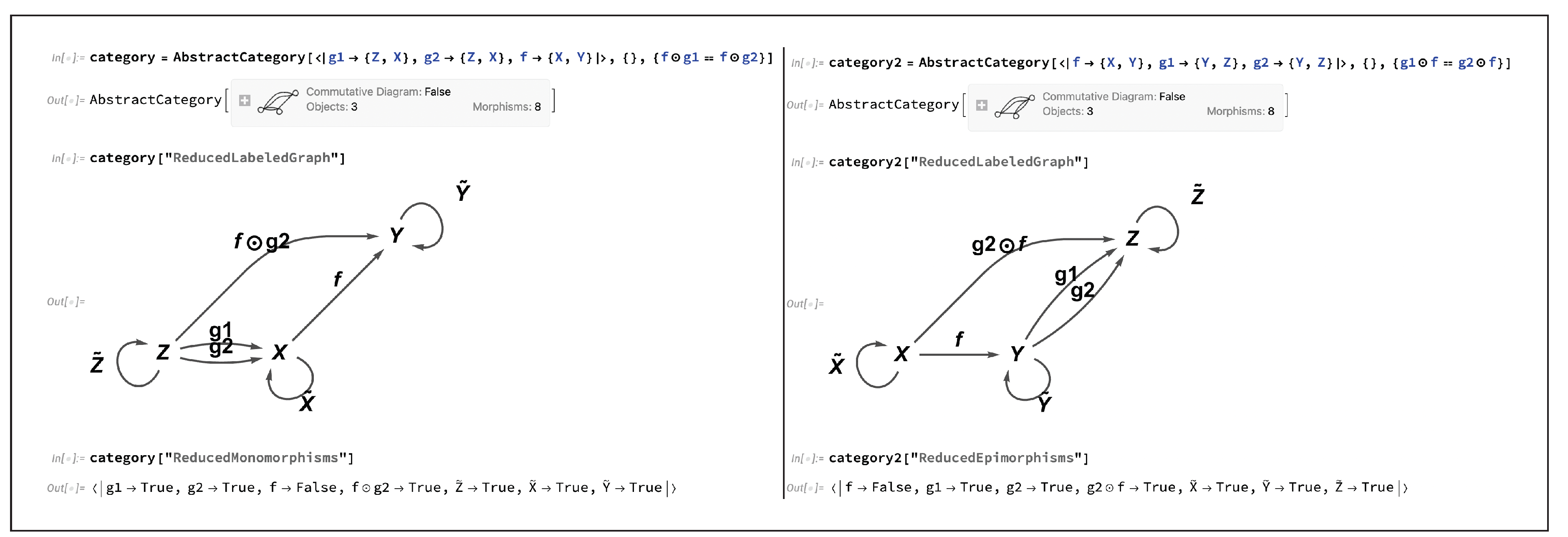

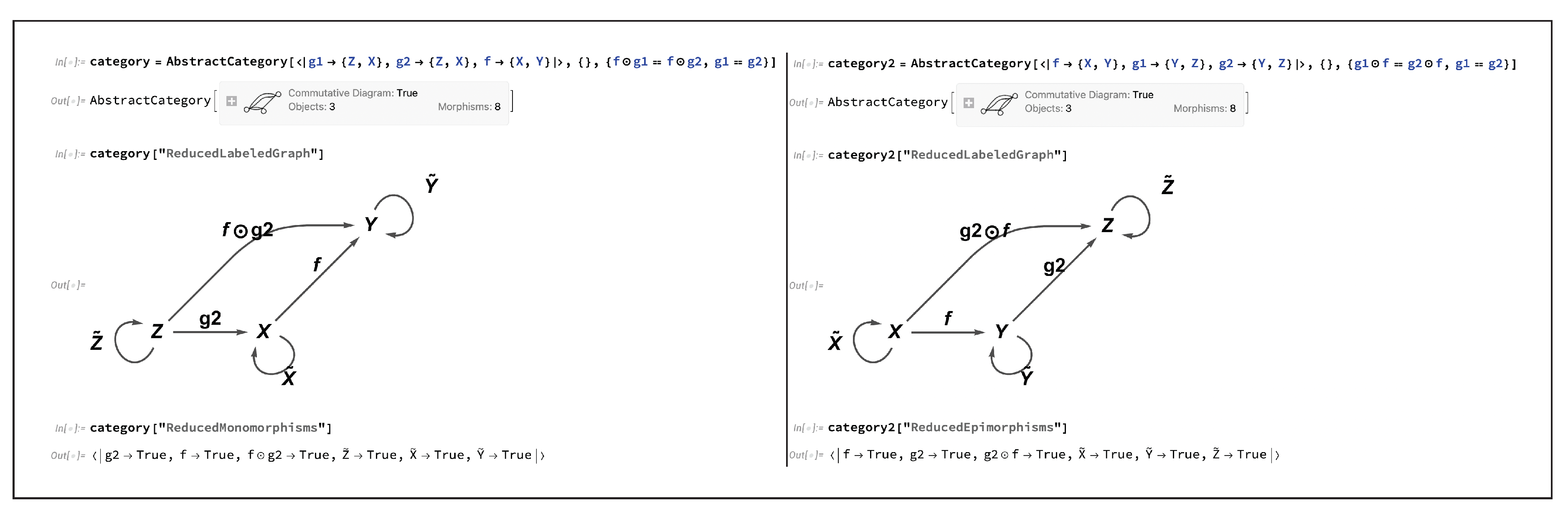

Figure 6 illustrates the basic diagrammatic setup for both monomorphisms and epimorphisms (commonly abbreviated simply to

monos and

epis in the category-theoretic literature) in CATEGORICA, and demonstrates in these two cases that all morphisms initially, i.e. in the absence of any further algebraic equivalences, correspond to monomorphisms and epimorphisms, respectively.

Figure 7 shows that, by imposing the algebraic equivalence

in the former case and

in the latter case, one is able to force the morphism

to cease to be a monomorphism in the former example, and to cease to be an epimorphism in the latter example. Finally,

Figure 8 demonstrates that one is able to restore the status of morphism

as a monomorphism (in the former case) or an epimorphism (in the latter case) by imposing the additional algebraic equivalence

(for the monomorphism case) or

(for the epimorphism case). Note that any morphism that is both a monomorphism and an epimorphism is known as a

bimorphism (the category-theoretic analog of a bijective function), and CATEGORICA contains in-built functionality for detecting and manipulating bimorphisms in much the same way.

An important special case of monomorphisms are

sections [

38,

41]: morphisms that possess left inverses (and hence which are, themselves, right inverses of some other morphism). Likewise, an important special case of epimorphisms are

retractions: dual to sections, these are morphisms that possess right inverses (and hence which are, themselves, left inverses of some other morphism). Specifically, if the morphisms

and

in the category

are such that

is the identity morphism on

Y (i.e.

), then

is a retraction of

, and

is a section of

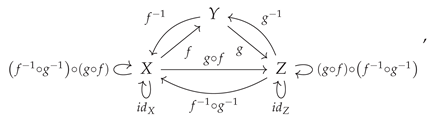

:

or, illustrated diagrammatically, a retraction is a morphism

such that one has:

Similarly, if

is the identity morphism on

X (i.e.

) then

is a section of

, and

is a retraction of

:

or, illustrated diagrammatically, a section is a morphism

such that one has:

These category-theoretic notions of retractions and sections are so-named because they naturally generalize the corresponding notions in topology, wherein one considers

retractions of topological spaces into subspaces to be continuous maps that preserve all points in the subspace (and for which the corresponding inclusion maps of the subspaces into the original spaces, such that the compositions of the two maps always reduce to the identity maps on the subspaces, would be

sections) [

42,

43].

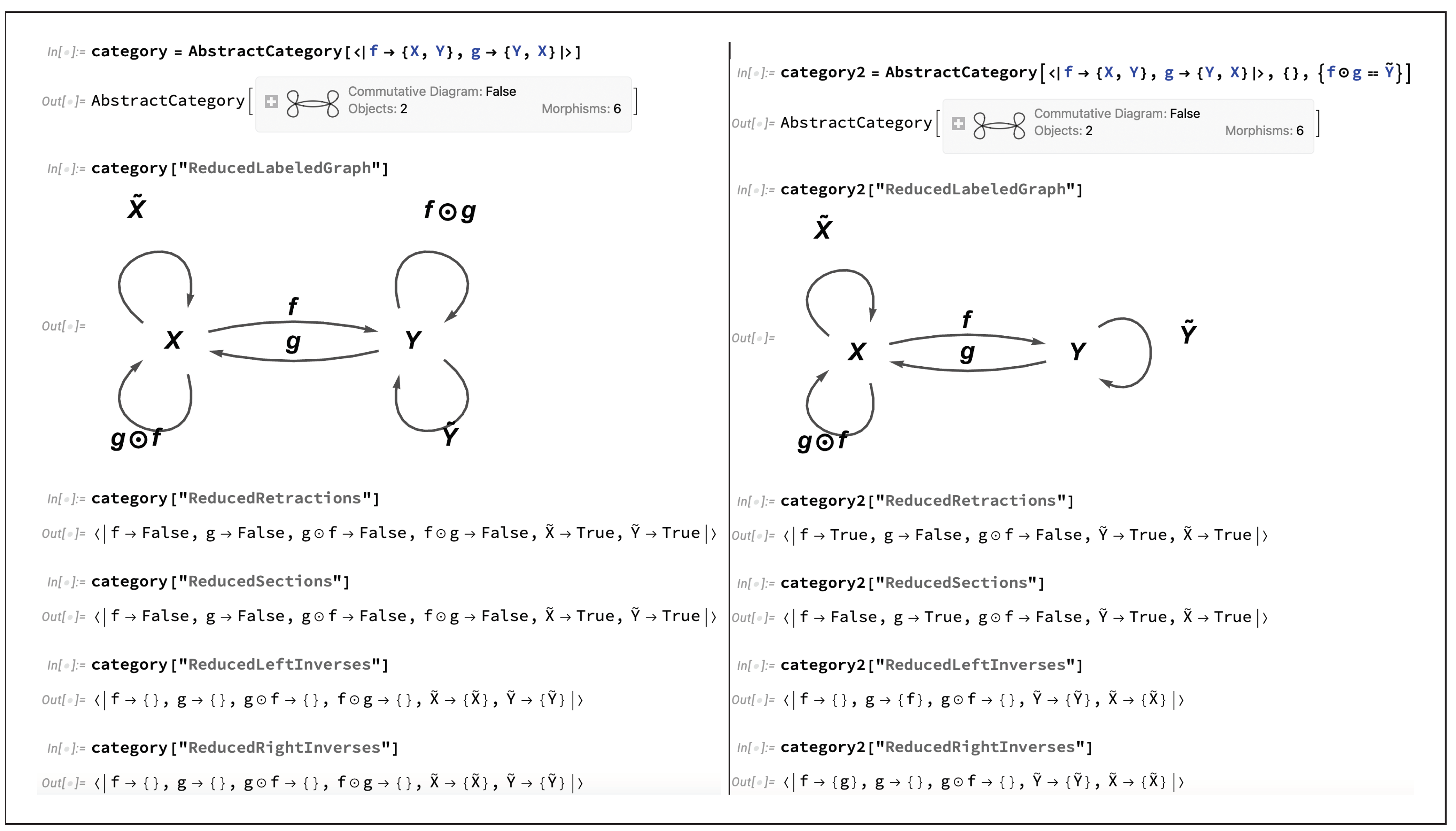

Figure 9 illustrates the basic diagrammatic setup for both retractions and sections in CATEGORICA, and demonstrates that initially (in the absence of any further algebraic equivalences) no morphisms, with the exception of identity morphisms, are either retractions or sections, and therefore that no morphisms, with the exception of identity morphisms, possess either left or right inverses. However, by imposing the algebraic equivalence

, one is able to force the morphism

to be a retraction (and hence to possess the morphism

as its right inverse), as well as to force the morphism

to be a section (and hence to possess the morphism

as its left inverse). It is therefore straightforward to prove, using CATEGORICA’s diagrammatic theorem-proving capabilities, that every section is necessarily a monomorphism (i.e. that the existence of a left inverse necessarily implies left-cancellativity) and that every retraction is necessarily an epimorphism (i.e. that the existence of a right inverse necessarily implies right-cancellativity).

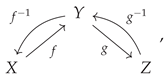

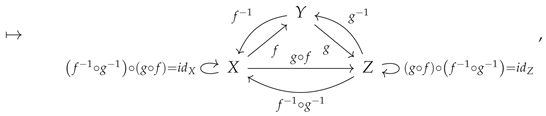

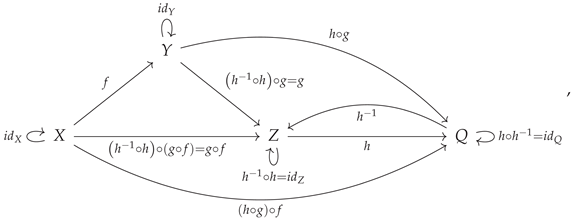

A morphism that acts as both a retraction and a section (and therefore which both is, and also possesses, a left and right inverse) is known as an

isomorphism. Specifically, if the morphism

in the category

is such that there exists another morphism

such that both

is the identity morphism on

X (i.e.

) and

is the identity morphism on

Y (i.e.

, then

is an isomorphism (as, correspondingly, is

):

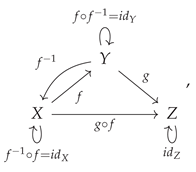

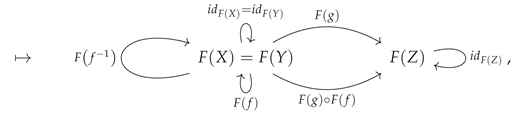

or, illustrated diagrammatically, an isomorphism is a morphism

such that one has:

A category in which all morphisms are isomorphisms is known as a

groupoid, since the morphisms of a groupoid consisting of a single object trivially form a group under the operation of morphism composition [

44] (with the associativity and identity axioms deriving from the underlying axioms of category theory, and the inverse axiom deriving from the existence of both left and right inverses for each morphism), and therefore the morphisms of a groupoid consisting of multiple objects may be thought of as forming an abstract generalization of a group in which the group operation is

partial, i.e. only well-defined for particular pairs of elements. Groupoids are particularly widely-studied in algebraic topology and homotopy theory, wherein the

fundamental groupoid of a topological space generalizes the more traditional fundamental group to the case where one does not necessarily fix a single distinguished base point [

45]. Much like in the case of commutative diagrams discussed previously, CATEGORICA is able to use purely graph-theoretic algorithms to compute the minimum set of morphism equivalences necessary to force the category shown above to be a groupoid, as well as to prove that these equivalences are indeed sufficient to do so, as shown in

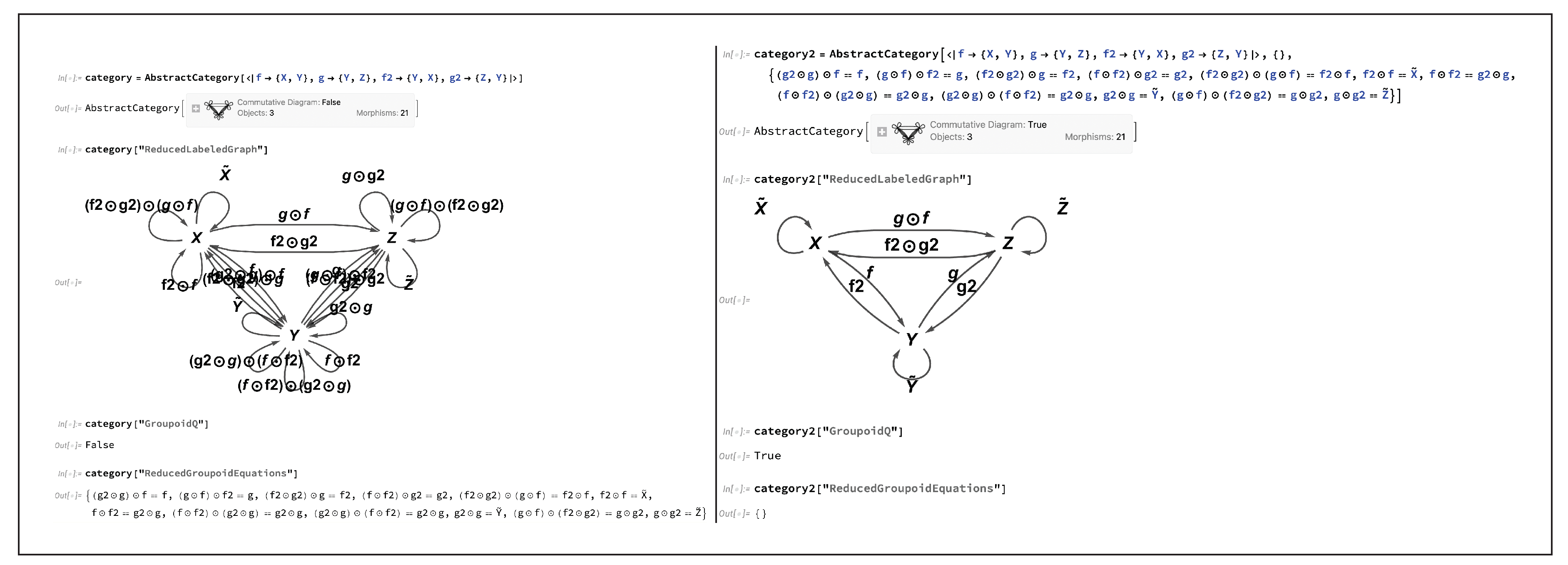

Figure 10. However, once the initial category is even marginally more complex than this, the task of determining the minimum set of algebraic conditions necessary for the category to be groupoidal quickly evolves to be highly non-trivial; for instance, for the case of a three-object category of the form:

one must consider not only the conditions necessary to force the morphisms

and

(and hence also the morphisms

and

) to be isomorphisms, namely:

i.e:

and:

i.e:

respectively, but also the conditions necessary to force the resulting pair of composite morphisms

and

to be isomorphisms as well, namely to collapse:

down to:

in addition to any relevant permutations thereof. Nevertheless, the generality of CATEGORICA’s algebraic reasoning algorithms ensures that it is able to handle such cases in exactly the same way, as demonstrated in

Figure 11.

Dual constructions of this general kind, such as monomorphisms vs. epimorphisms, retractions vs. sections, etc., are ubiquitous throughout category theory, and can be investigated systematically using the

“DualCategory” property of

AbstractCategory objects in the CATEGORICA framework (e.g. a morphism that registers as a monomorphism within a particular

AbstractCategory object will register as an epimorphism in the corresponding

AbstractCategory object returned by the

“DualCategory” property, etc.). A very straightforward example of a dual construction is that of

initial vs.

terminal objects; an initial object

X in the category

is an object such that, for every object

P (including

X itself) in

, there exists a unique

outgoing morphism

:

or, illustrated diagrammatically:

Dually, a terminal object

X in the category

is an object such that, for every object

P (including

X itself) in

, there exists a unique

incoming morphism

:

or, illustrated diagrammatically:

Initial and terminal objects generalize many key construction in pure mathematics [

38,

46], such as the bottom/minimal and top/maximal elements ⊥ and ⊤ of partially-ordered sets (since, if one considers a category

constructed from a given poset

whose objects are elements of

and where the morphism

exists in

if and only if

in

, then the bottom/minimal element ⊥ is an initial object and the top/maximal element ⊤ is a terminal object in the category

), and the empty and point spaces

⌀ and * in topology (since, if one considers the category

whose objects are topological spaces and whose morphisms are continuous functions between them, then the empty space

⌀ is an initial object in

because there exists a unique continuous function mapping the empty space to any other topological space, and the point space * is a terminal object in

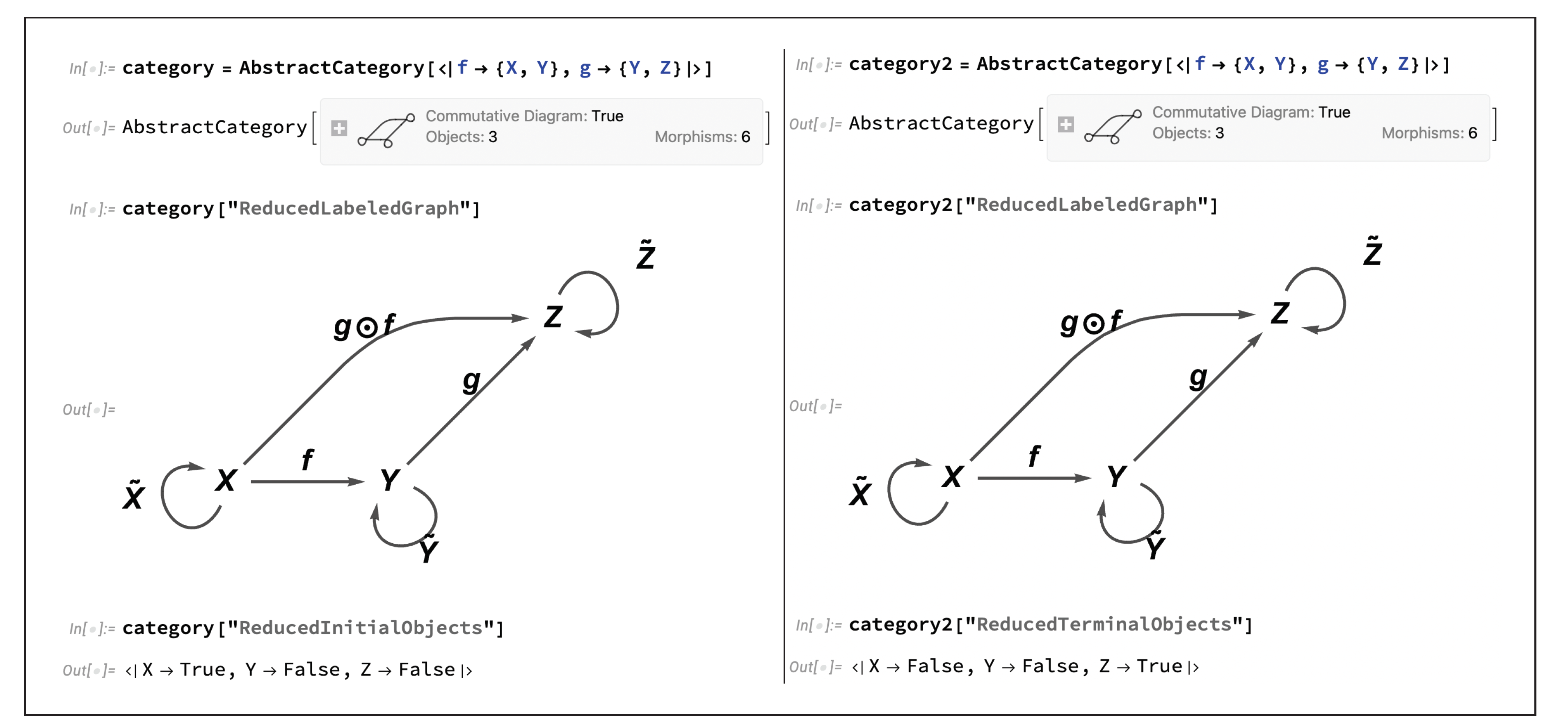

because there exists a unique continuous function mapping any topological space to the point space). If we take the simple triangular diagram case that we have investigated previously:

then it is easy to see that

X here is an initial object, and, dually, that

Z is a final object, as illustrated by the elementary CATEGORICA implementation shown in

Figure 12. However, a slightly more subtle refinement of the concept of an ordinary initial object is that of a

strict initial object, namely an initial object

X for which all incoming morphisms

(where

Q is an arbitrary object in the category

) must be isomorphisms:

or, illustrated diagrammatically:

Dually, a

strict terminal object is a terminal object

X for which all outgoing morphisms

(where

Q is again an arbitrary object in the category

) must be isomorphisms:

or, illustrated diagrammatically:

Returning again to the simple triangular diagram above, and introducing either a new incoming morphism

to the initial object

X, or a new outgoing morphism

from the terminal object

Z (along with corresponding morphisms

or

in the reverse directions, respectively), i.e:

or:

respectively, we see that, in the first case,

X ceases to be a strict initial object (since the incoming morphism

is not an isomorphism), and in the second case,

Z ceases to be a strict terminal object (since the outgoing morphism

is also not an isomorphism), as demonstrated in

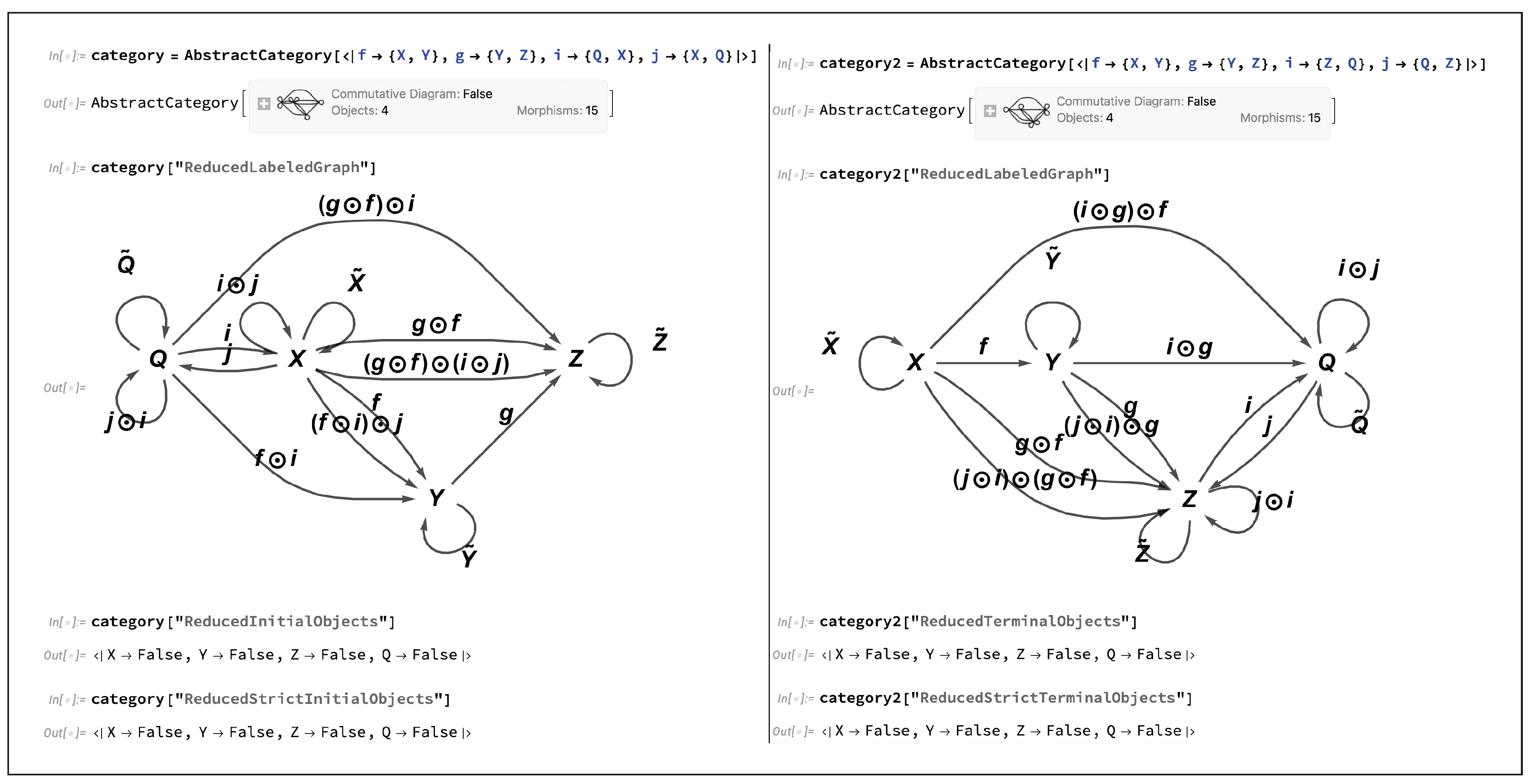

Figure 13. Indeed,

X and

Z are no longer initial/terminal objects even in the non-strict sense, due to the existence of multiple (currently algebraically inequivalent) outgoing morphisms:

from

X to

Y and from

X to

Z in the former case, and multiple (currently algebraically inequivalent) incoming morphisms:

from

Y to

Z and from

X to

Z in the latter case. However, if we now impose the pair of algebraic equivalences:

thereby ensuring that:

in the former case, and the pair of algebraic equivalences:

thereby ensuring that:

in the latter case, then morphisms

and

(as well as their corresponding reverse morphisms

and

, respectively) now become isomorphisms, collapsing the above diagrams to:

and:

respectively, and therefore causing

X and

Z to be strict initial and terminal objects, respectively, as illustrated in

Figure 14. Any object that is both an initial object and a terminal object simultaneously is known as a

zero object (and, by extension, any object that is both a strict initial object and a strict terminal object simultaneously is known as a

strict zero object), and shares certain structural features in common with the point space object * in the category

of

pointed topological spaces (i.e. topological spaces with a distinguished base point). Categories that contain zero objects are consequently referred to as

pointed categories. CATEGORICA also has specialized functionality for handling zero objects, strict zero objects and pointed categories built into the

AbstractCategory function.

The final example of a dual construction that we shall discuss within the context of the present section, due to its close relationship with the monomorphism vs. epimorphism duality discussed previously, is that of

constant vs.

coconstant morphisms. If the morphism

in the category

is such that, for all objects

Z and all pairs of morphisms

and

, one necessarily has that

, then

is a constant morphism:

or, illustrated diagrammatically, one has:

Note that this is identical to the diagram that appears in the

hypothesis of the definition of a monomorphism (and therefore we may say, slightly loosely, that a monomorphism is a constant morphism for which one necessarily has that

). Dually, if the morphism

in the category

is such that, for all objects

Z and all pairs of morphisms

and

, one necessarily has that

, then

is a coconstant morphism:

or, illustrated diagrammatically, one has:

Note that this is, likewise, identical to the diagram that appears in the

hypothesis of the definition of an epimorphism (and therefore we may also say, again slightly loosely, that an epimorphism is a coconstant morphism for which one necessarily has that

). Constant morphisms are so-named because they generalize the notion of constant functions in mathematical analysis (and, accordingly, coconstant morphisms may be thought of as generalizing the notion of zero-maps in analysis); any morphism that is both a constant morphism and a coconstant morphism is known as a

zero morphism, since such morphisms share certain key algebraic properties with morphisms mapping into and out of zero objects (by the same token, constant morphisms share certain algebraic properties with morphisms mapping into terminal objects, and coconstant morphisms share certain algebraic properties with morphisms mapping out of initial objects) [

47].

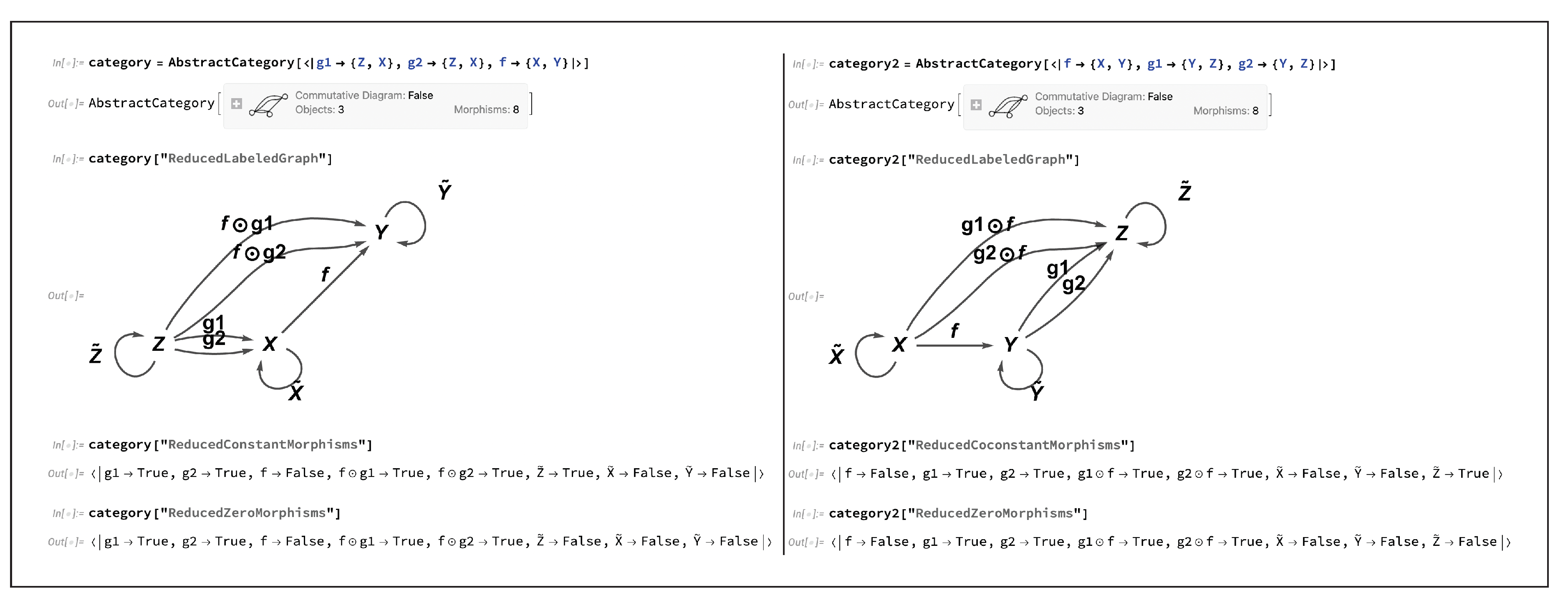

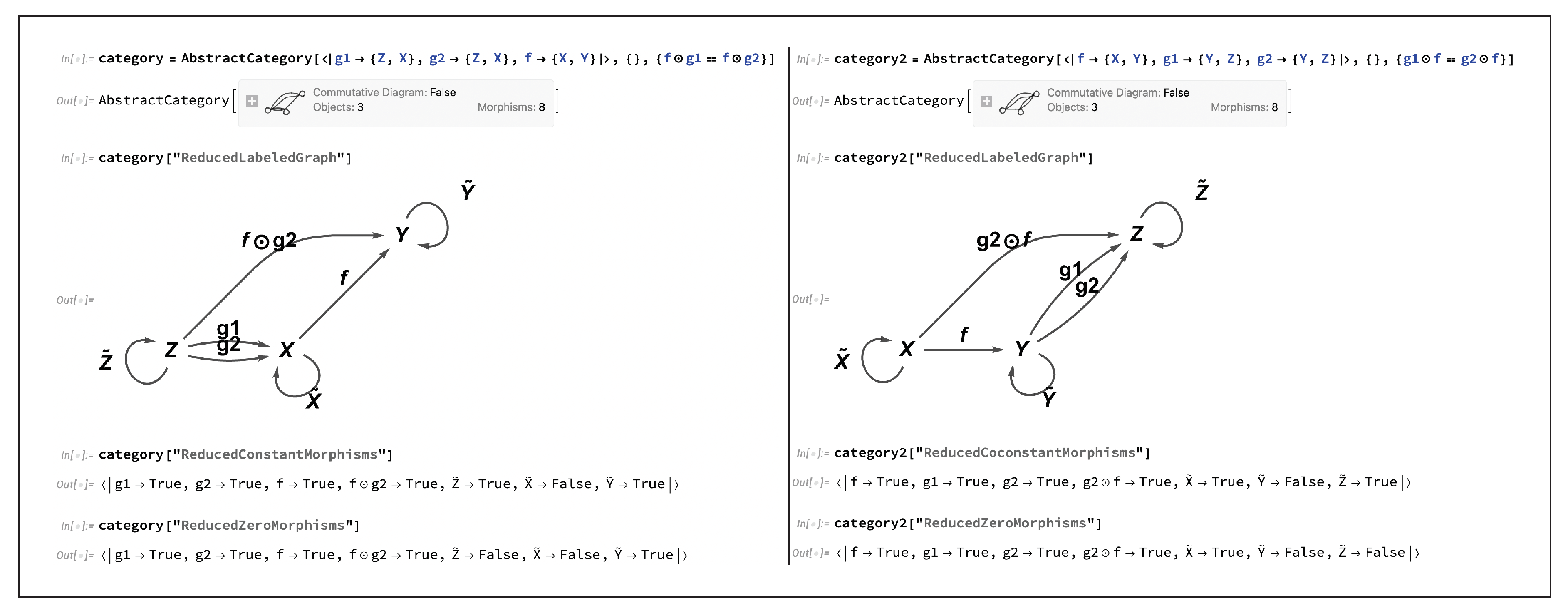

Figure 15 illustrates the basic diagrammatic setup for both constant and coconstant morphisms in CATEGORICA, and demonstrates that initially (in the absence of any further algebraic equivalences) the morphism

is not a constant morphism (in the former case), or not a coconstant morphism (in the latter case), and hence also not a zero morphism (in either case).

Figure 16 shows that, by imposing the algebraic equivalence

in the former case and

in the latter case, one is able to force the morphism

to be a constant morphism in the former example, and to be a coconstant morphism in the latter example, and therefore a zero morphism in both examples.

The AbstractCategory function in CATEGORICA also contains functionality for detecting and manipulating many other special types of morphism, including endomorphisms (i.e. morphisms mapping an object X to itself) through the “Endomorphisms” property and its variants, automorphisms (i.e. isomorphisms between an object X and itself) through the “Automorphisms” property and its variants, etc. There are also many other special types of category (beyond simply the groupoids and commutative diagrams discussed thus far) that can be automatically detected and represented using CATEGORICA, with AbstractCategory in many cases including specialized functionality for manipulating them, including discrete categories (i.e. categories in which the only morphisms are identity morphisms) through the “DiscreteCategoryQ” property, indiscrete categories (i.e. categories in which there exists a unique morphism between every pair of objects) through the “IndiscreteCategoryQ” property, balanced categories (i.e. categories in which every bimorphism is also necessarily an isomorphism) through the “BalancedCategoryQ” property, etc. Needless to say, many additional properties and capabilities are also planned for future development. In many cases these properties have rather elegant mathematical interpretations; for instance, discrete categories may be thought as being a natural category-theoretic generalization of discrete topological spaces (i.e. topological spaces equipped with a discrete topology, in which every subset is open), since in a discrete topological space the only allowable paths are the identity paths from a point to itself, etc. However, in the interests of brevity, we will not cover these additional capabilities in any detail here.

4. Functors and Fibrations

A homomorphism (i.e. a structure-preserving map) between two categories is known as a

functor [

38,

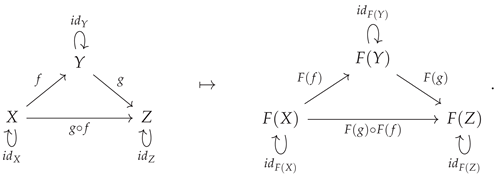

48] . More precisely, the map

from a category

to a category

is a functor if and only if it associates every object

X in category

to a corresponding object

in category

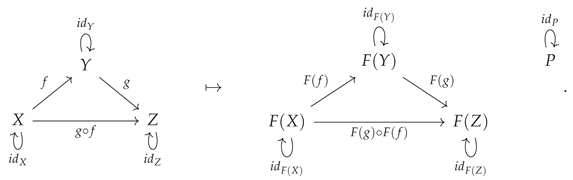

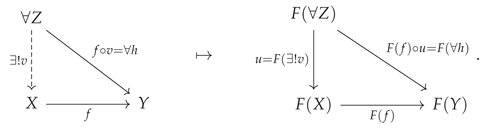

, i.e:

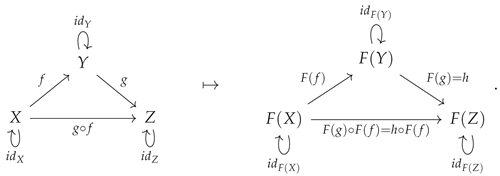

and every morphism

in category

to a corresponding morphism

in category

, i.e:

in such a way that the identity morphisms are all preserved, such that the identity morphism

on object

X in category

is always mapped to the identity morphism

on object

in category

, i.e:

and the composition of morphisms is also preserved, such that the composite morphism

in category

(where

and

are also morphisms in

) is always mapped to the composite morphism

in category

, i.e:

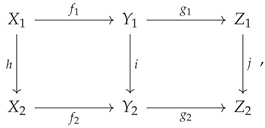

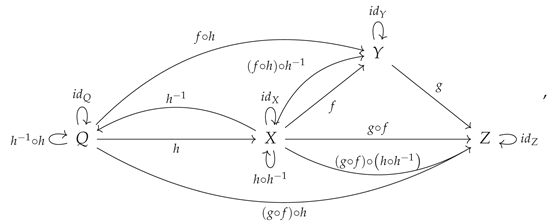

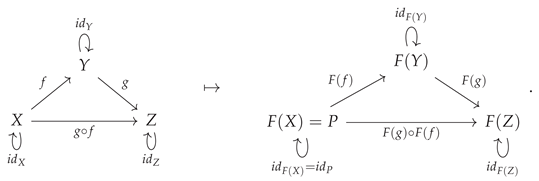

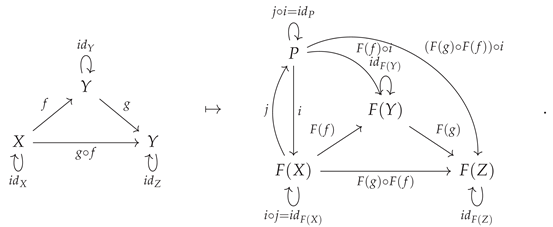

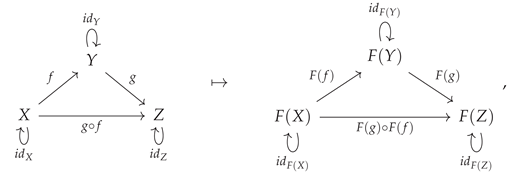

The functor construction may be illustrated diagrammatically by means of the following minimal example:

Functoriality turns out to be an extremely powerful algebraic condition, and functors may consequently be thought of as generalizing many central constructions in pure mathematics, including group actions in the context of group theory (wherein one considers functors from single-object groupoids, i.e. groups, to the category

whose objects are sets and whose morphisms are set-valued functions), group

representations in the context of representation theory (wherein one again considers functors from groups/single-object groupoids, but now to the category

whose objects are vector spaces and whose morphisms are linear maps), and tangent bundles in differential geometry (wherein one considers functors from the category

whose objects are differentiable manifolds of smoothness class

and whose morphisms are

p-times continuously differentiable maps, to the category

whose objects are vector bundles over the manifolds in

and whose morphisms are vector bundle homomorphisms). Indeed, as mentioned previously, even categorical diagrams themselves may be formalized as functors

from some index category/scheme

to an arbitrary category

. Power sets in set theory (i.e. functors from the category

of sets and set-valued functions to itself) and fundamental groups in algebraic topology (i.e. functors from the category

of pointed topological spaces and continuous functions between them, to the category

of groups and group homomorphisms) constitute further examples of key functorial constructions in mathematics that have previously been alluded to within this article.

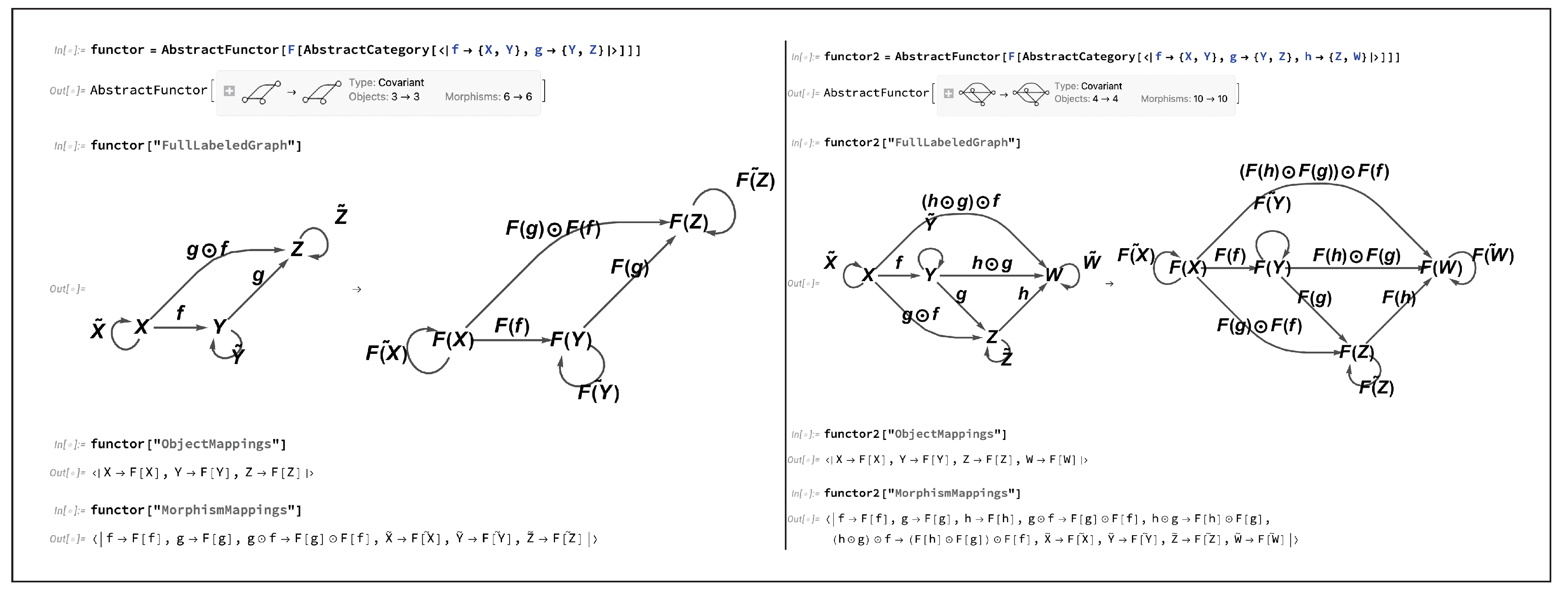

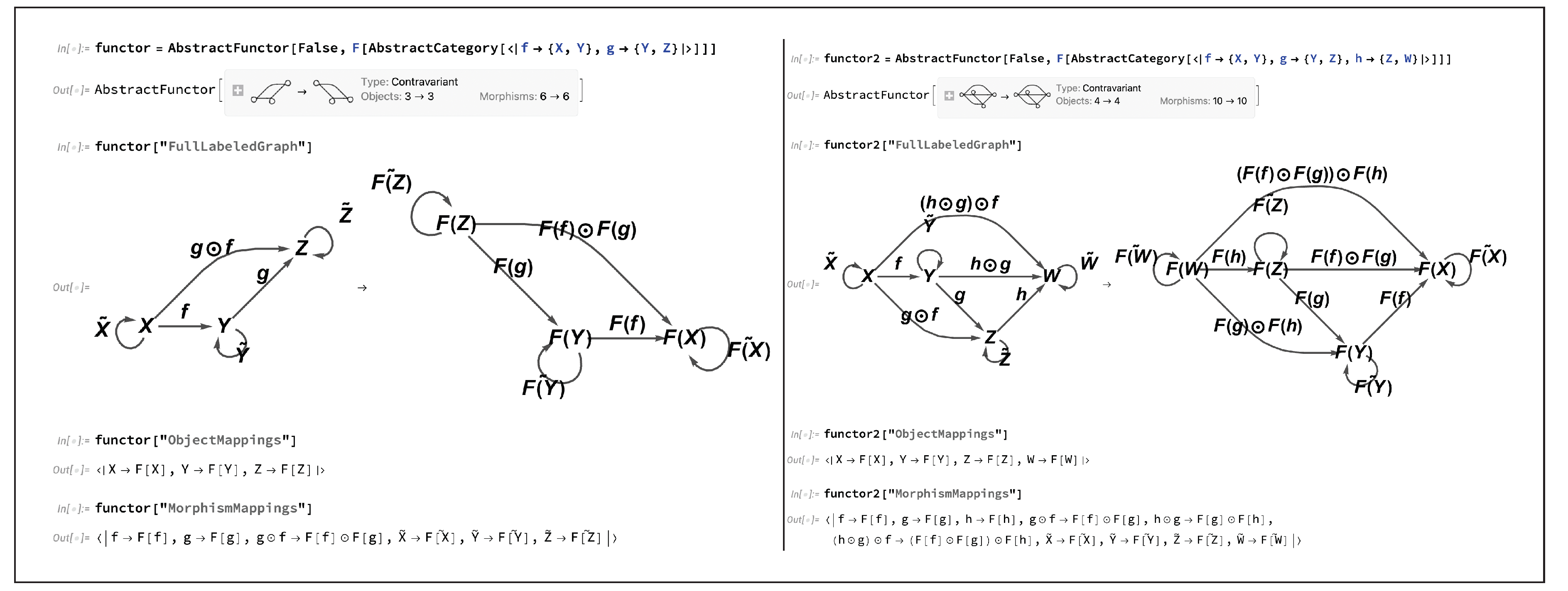

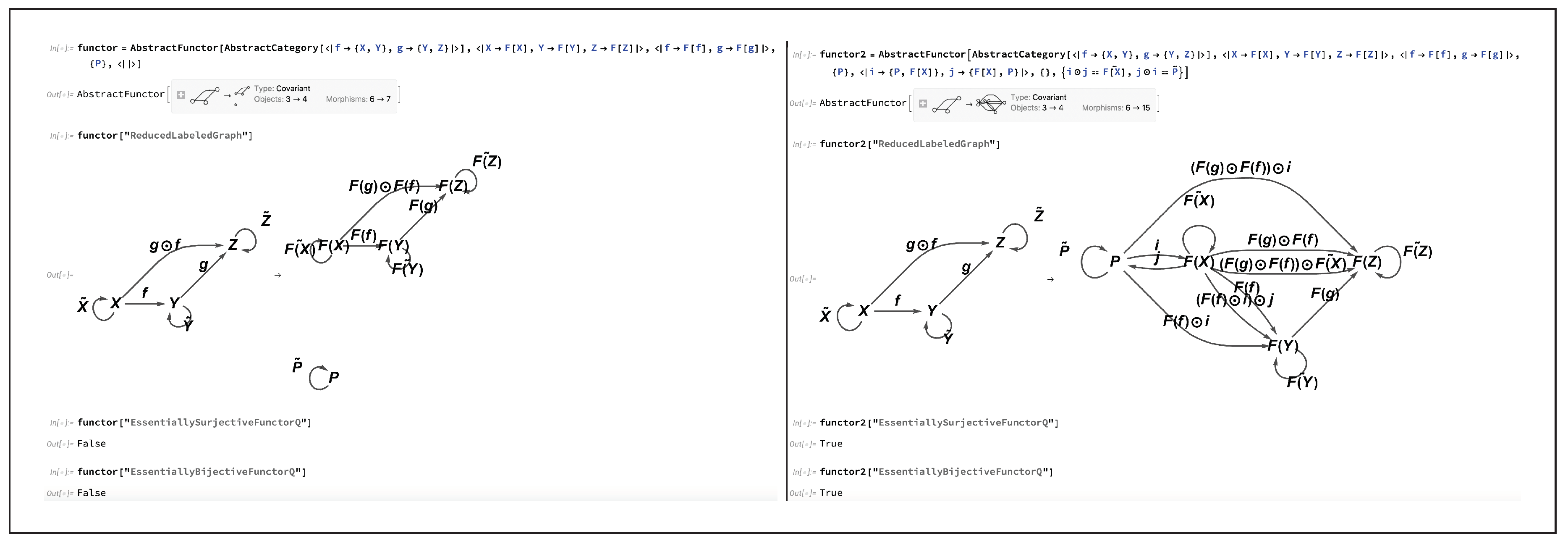

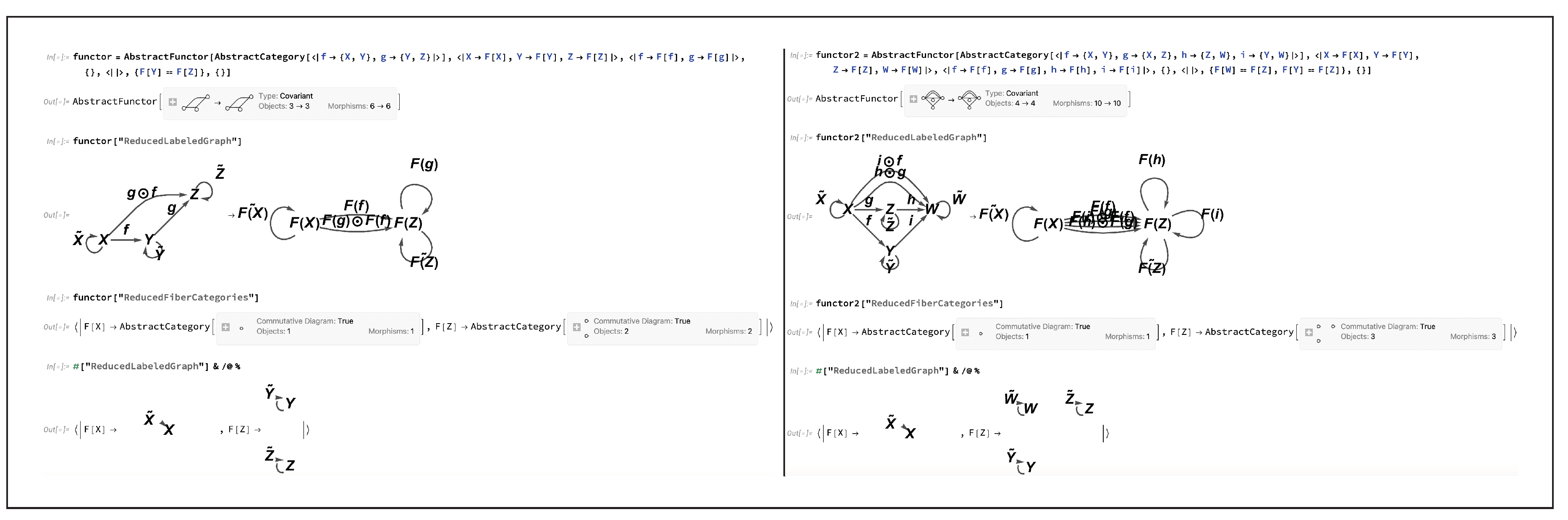

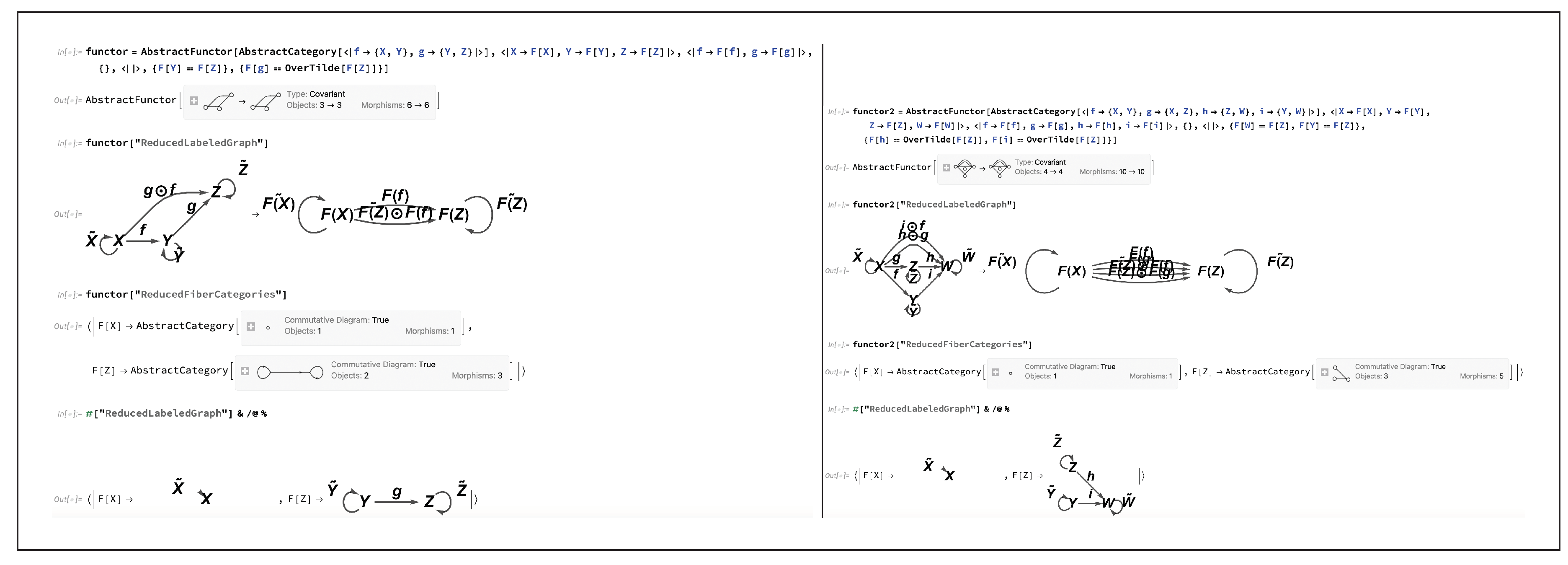

Figure 17 shows the implementation of the minimal example presented above, along with a slightly larger example, in the CATEGORICA framework using the

AbstractFunctor function; much like with the

AbstractCategory objects themselves, CATEGORICA automatically keeps track of, and enforces, all necessary algebraic equivalences between objects and morphisms within the codomain category of an

AbstractFunctor object that must be imposed in order to maintain consistency with the functor axioms described above.

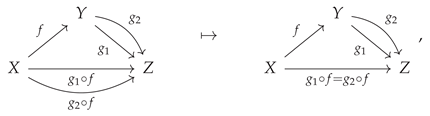

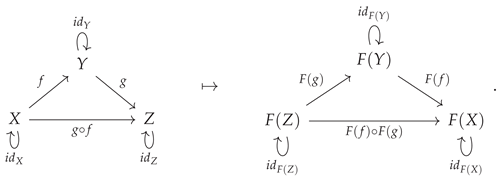

Although the formal definition presented above corresponds to the case of

covariant functors (namely functors which preserve the directions of morphisms, and hence which also preserve the order of composition of morphisms), there also exists a dual notion of

contravariant functors, which obey analogous axioms but which reverse the directions of morphisms, and hence also reverse the order of morphism composition. The definition of the mapping on objects remains unchanged from the covariant case, but now every morphism

in category

is mapped to a corresponding morphism

in category

, i.e:

The condition on identity morphisms is also unchanged from the covariant case, but now the composite morphism

in category

(where

and

are also morphisms in

) is always mapped to the composite morphism

in category

, i.e:

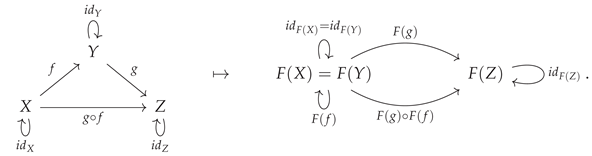

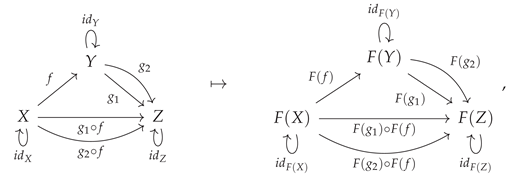

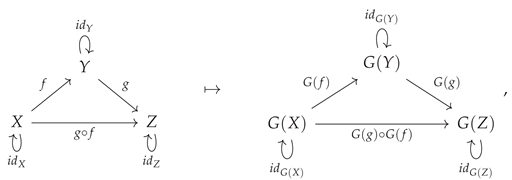

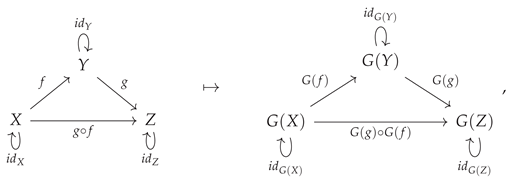

The contravariant functor construction may, just as before, be illustrated diagrammatically by means of the following minimal example:

Just as covariant functors from the category

of differentiable manifolds and differentiable maps to the category

of vector bundles and vector bundle homomorphisms may be used to generalize the construction of tangent bundles in differential geometry, the construction of

cotangent bundles may correspondingly be generalized using the corresponding

contravariant functor from

(or, more precisely, from its dual/opposite category

) to

. Likewise, the operation of taking dual spaces in linear algebra corresponds to the application of a certain contravariant functor from the category

of vector spaces and linear maps over some fixed field

K (or, more precisely, from its dual/opposite category

), to itself. Indeed, the power set construction in set theory may in fact be formalized as

either a covariant functor

(as above),

or as a contravariant functor

. The notion of presheaves on a space

X in algebraic topology may be formalized as a functor from the dual/opposite category

of the category

whose objects are open sets

and whose morphisms are inclusion maps

, to

; when appropriately extended to the case where the category

(and hence the domain category

of the contravariant functor) is arbitrary, this yields the corresponding category-theoretic notion of a presheaf, which is far more general.

Figure 18 demonstrates a CATEGORICA implementation of the corresponding contravariant versions of the two functors previously shown in

Figure 17, obtained in each case by setting the first argument of

AbstractFunctor (i.e. the covariance argument) to

False. At any time, the dual version of any

AbstractFunctor object may be computed directly using the

“SwapVariance” property (analogous to the

“DualCategory” property of

AbstractCategory objects), with CATEGORICA automatically making any required modifications to the order of morphism composition within all morphism equivalence lists, etc.

In its full form, and in the absence of any additional variance information, an

AbstractFunctor object is specified by the

AbstractCategory object for its domain category, an association of object mappings, an association of morphism (or, more precisely, arrow) mappings, a list of new objects in the codomain category, a list of new morphisms (or, more precisely, arrows) in the codomain category, a list of new object equivalences in the codomain category, and a list of new morphism equivalences in the codomain category (as well as optional additional information regarding choices of composition and identity symbols, as with

AbstractCategory). Note, in particular, that all mappings take place at the level of the underlying

AbstractQuiver object, rather than on the

AbstractCategory object itself, so as to guarantee consistency with the composition/functoriality axioms. All algebraic equivalences between objects and arrows/morphisms in the domain

AbstractCategory object (or its underlying

AbstractQuiver object) are automatically translated into corresponding algebraic equivalences in the codomain

AbstractCategory object. We may therefore regard a functor

as corresponding to a pair of (set-valued, since we are dealing here with small categories) functions,

and

, with the former mapping the set of objects in category

to the set of objects in category

and the latter mapping the set of morphisms in category

to the set of morphisms in category

:

This, in turn, presents (at least) two distinct ways in which functors may be classified as either injective, surjective or bijective; namely, functors may be injective/surjective/bijective on objects, or on morphisms, or on both, or on neither (depending upon the injectivity/surjectivity/bijectivity properties of the functions

and

). A simple way in which a functor may fail to be injective on objects is by having two objects in the codomain category be equivalent which were not previously equivalent in the domain category; for instance, consider the functor:

plus the additional algebraic condition that

, imposed on the objects in the codomain category

, such that one instead has:

Such a functor would no longer be injective, and hence also no longer bijective, on objects, although its injectivity (and therefore bijectivity) on objects could nevertheless be restored by introducing a corresponding algebraic condition

on the objects in the domain category

, such that one instead has:

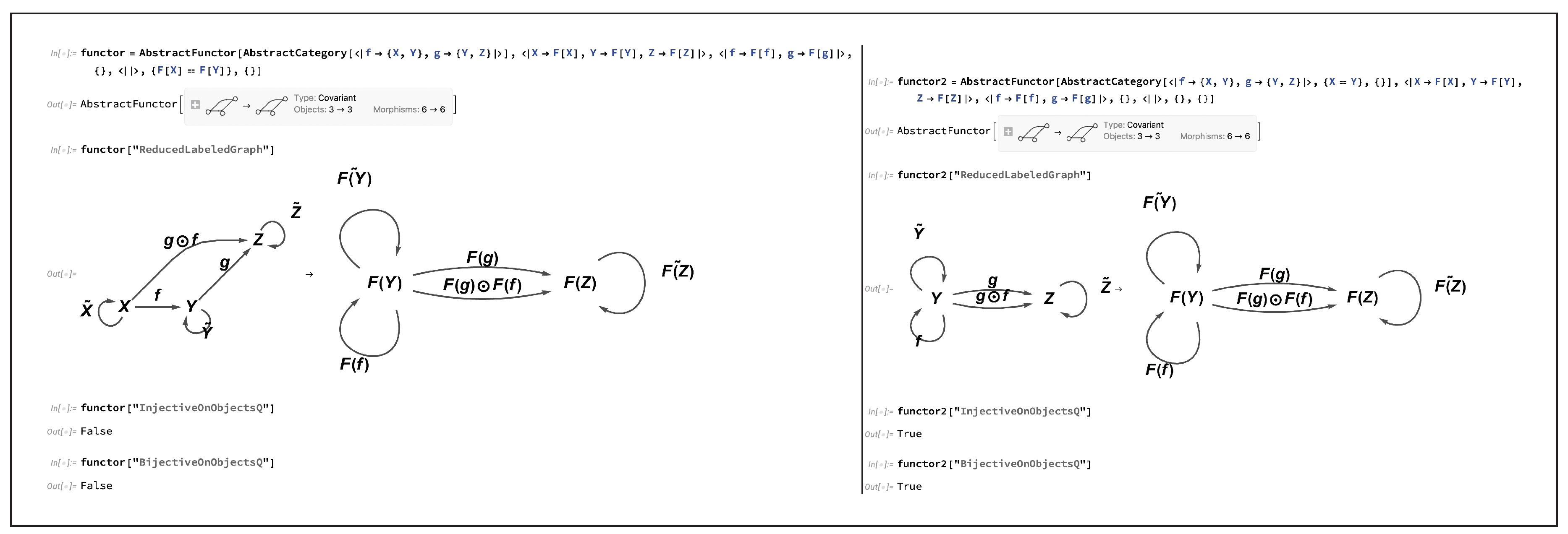

Figure 19 implements this basic example in CATEGORICA, demonstrating how functor injectivity on objects may be removed (by imposing the algebraic equivalence

on objects in the codomain category) and then subsequently reinstated (by imposing the additional algebraic equivalence

on objects in the domain category). Dual to this construction, a simple way in which a functor may fail to be surjective on objects is by having a new object be introduced in the codomain category that did not previously exist in the domain category; for instance, consider now the functor:

Such a functor would no longer be surjective, and hence also no longer bijective, on objects, although its surjectivity (and therefore bijectivity) on objects could nevertheless be restored by introducing a new algebraic condition

on the objects in the codomain category

, such that one instead has:

Figure 20 implements this dual example in CATEGORICA, demonstrating now how functor surjectivity on objects may be removed (by introducing the new object

P in the codomain category) and then subsequently reinstated (by imposing the algebraic equivalence

on objects in the codomain category), in much the same way.

However, there may nevertheless be cases in which a functor is only injective, surjective or bijective on objects

up to isomorphism, which in turn motivates the concepts of

essential injectivity,

essential surjectivity and

essential bijectivity. For instance, consider again the example presented above, in which a functor fails to be injective on objects because of an additional algebraic condition

that has been imposed on the objects in the codomain category

:

Now, rather than imposing the strict algebraic equality

on the objects in the domain category

, suppose instead that one introduces a new inverse morphism

in

, such that:

and therefore the objects

X and

Y become isomorphic, thus yielding:

in the domain category, which maps to:

in the codomain category. Then, the resulting functor would still not be strictly injective, nor strictly bijective, on objects, but it would be

essentially injective, and hence

essentially bijective (i.e. injective/bijective up to isomorphism).

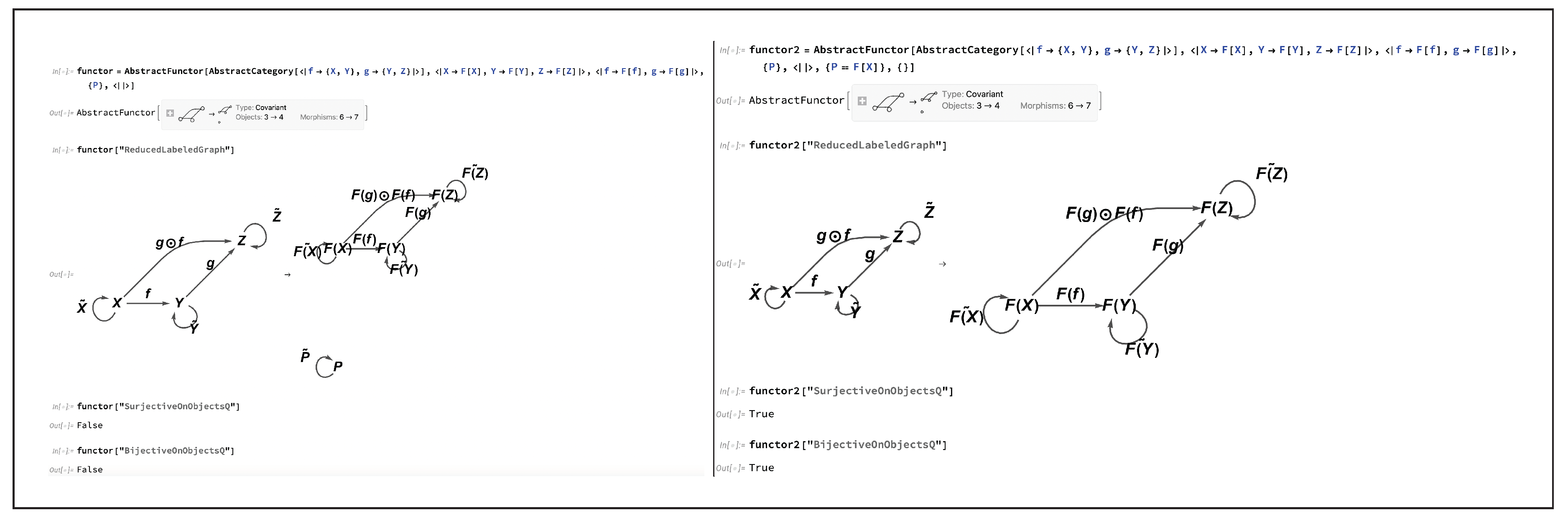

Figure 21 implements this example in CATEGORICA, showing how essential injectivity may be reinstated by imposing the isomorphism

on objects in the domain category. Dually, consider again the previous example of a functor that fails to be surjective on objects because of a new object

P that has been introduced in the codomain category:

Similarly, rather than imposing the strict algebraic equality

on the objects in the codomain category

, we can instead introduce a new pair of morphisms

and

, such that:

and therefore force the objects

P and

to be isomorphic, hence yielding:

Now, the resulting functor is still not strictly surjective, nor strictly bijective, on objects, but it is

essentially surjective, and hence

essentially bijective (i.e. surjective/bijective up to isomorphism).

Figure 22 implements this dual example in CATEGORICA, showing how essential surjectivity may be reinstated by imposing the isomorphism

on objects in the codomain category.

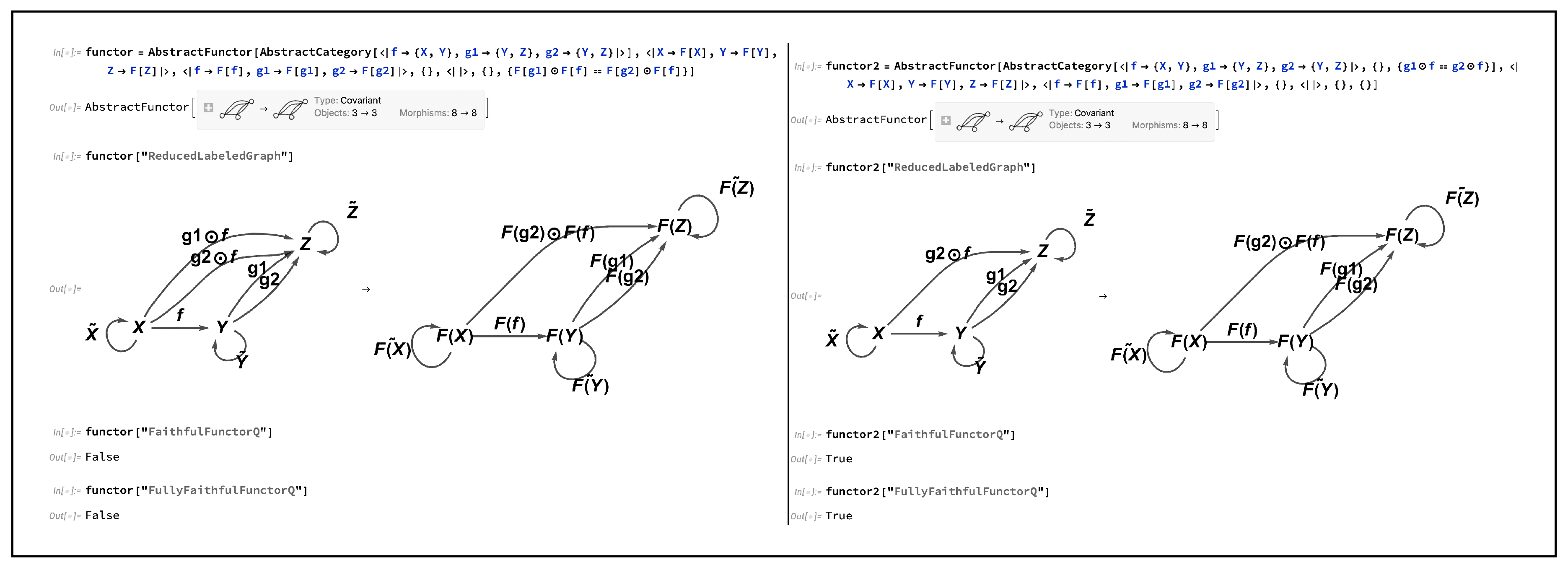

On the other hand, shifting now from considering the properties of the

function to those of the

function, functors that are injective, surjective or bijective on

morphisms are known as

faithful functors,

full functors or

fully faithful functors, respectively. A simple way in which a functor may fail to be faithful (i.e. fail to be injective on morphisms) is by having two morphisms in the codomain category be equivalent which were not previously equivalent in the domain category; for instance, consider the functor:

plus the additional algebraic condition that:

on the morphisms in the codomain category

, such that one instead has:

Such a functor would no longer be faithful (i.e. no longer injective on morphisms), and hence also no longer fully faithful (i.e. no longer bijective on morphisms), although its faithfulness, and therefore full faithfulness, could nevertheless be restored by introducing a corresponding algebraic condition:

on the morphisms in the domain category

, such that one now has:

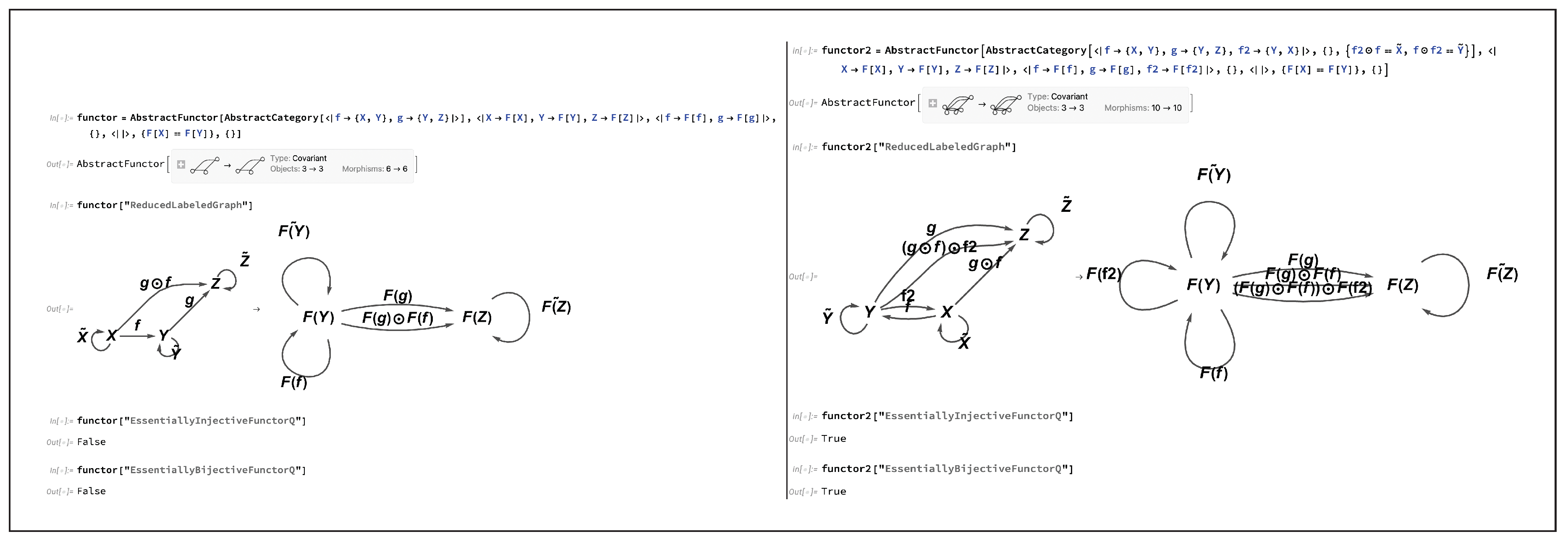

Figure 23 implements this elementary example in CATEGORICA, illustrating how the faithfulness of a functor may be removed (by imposing the algebraic equivalence

on morphisms in the codomain category) and then subsequently reinstated (by imposing the additional algebraic equivalence

on morphisms in the domain category). Dual to this construction, a simple way in which a functor may fail to be full (i.e. fail to be surjective on morphisms) is by having a new morphism be introduced in the codomain category that did not previously exist in the domain category; for instance, consider now the functor:

Such a functor would no longer be full (i.e. no longer surjective on morphisms), and hence also no longer fully faithful (i.e. no longer bijective on morphisms), although its fullness, and hence full faithfulness, could nevertheless be restored by introducing a new algebraic condition:

on morphisms in the codomain category

, such that one now has:

Figure 24 implements this dual example in CATEGORICA, illustrating how the fullness of a functor may be removed (by introducing the new morphism

in the codomain category) and then subsequently reinstated (by imposing the algebraic equivalence

on morphisms in the codomain category).

The final example of a functorial construction that we shall cover within this section, due to its rather foundational significance in the fields of algebraic geometry, algebraic topology and (higher) homotopy theory, is that of a (Grothendieck)

fibration [

49,

50]. This purely category-theoretic notion of a fibration is effectively a grand generalization of the notion of a fiber bundle (or topological fibration) in topology, wherein one considers a functor of the general form

, with the domain category

being the

total category of the fibration (thus playing an analogous role to that of the

total space of a fiber bundle) and the codomain category

being the

base category (thus playing an analogous role to that of the

base space of the same fiber bundle). For each object

X in the base category

, one can consider the

fiber category at

X, which is a category whose object set

is the set of objects in the total category

that map to

X under the functor

F (i.e. the preimage of

X under the function

) and whose morphism set

is the set of morphisms in the total category

that map to the identity morphism

on

X under

F (i.e. the preimage of

under the function

), i.e:

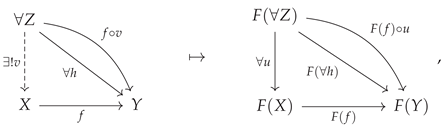

In order to qualify as a valid Grothendieck fibration, however, the functor

must satisfy an additional, and rather technical, condition known as

contravariant pseudofunctoriality (for the corresponding dual construction, known as a Grothendieck

opfibration, the relevant condition is

covariant pseudofunctoriality), which is typically expressed in terms of

Cartesian morphisms. The formal definition of a Cartesian morphism is unfortunately a little opaque; specifically, if the morphism

in the total category

is such that, for all objects

Z and all morphisms

in

, and all morphisms

in the base category

such that

, there necessarily exists a unique morphism

in the total category

such that

in

and

in

, then

is Cartesian:

or, illustrated diagrammatically, one has the following basic setup:

which then collapses down to:

The contravariant pseudofunctoriality condition that characterizes Grothendieck fibrations is then the condition that, for every object

Y in the total category

, and every morphism

mapping to the image

of

Y in the base category

, there must exist some Cartesian morphism

in the total category

such that the morphism

is the image of the Cartesian morphism

in the base category

, i.e.

(and therefore also

):

There exist many notable specializations of this highly abstract Grothendieck fibration definition, including the case of

discrete fibrations (in which every fiber category

is a discrete category, consisting solely of objects and their identity morphisms) and

groupoidal fibrations (in which every fiber category

is a groupoid). CATEGORICA does not yet possess the functionality to detect and characterize all cases of Grothendieck fibrations with complete generality, although important special cases (such as discrete fibrations, via the

“DiscreteFibrationQ” property, etc.) have indeed been implemented fully.

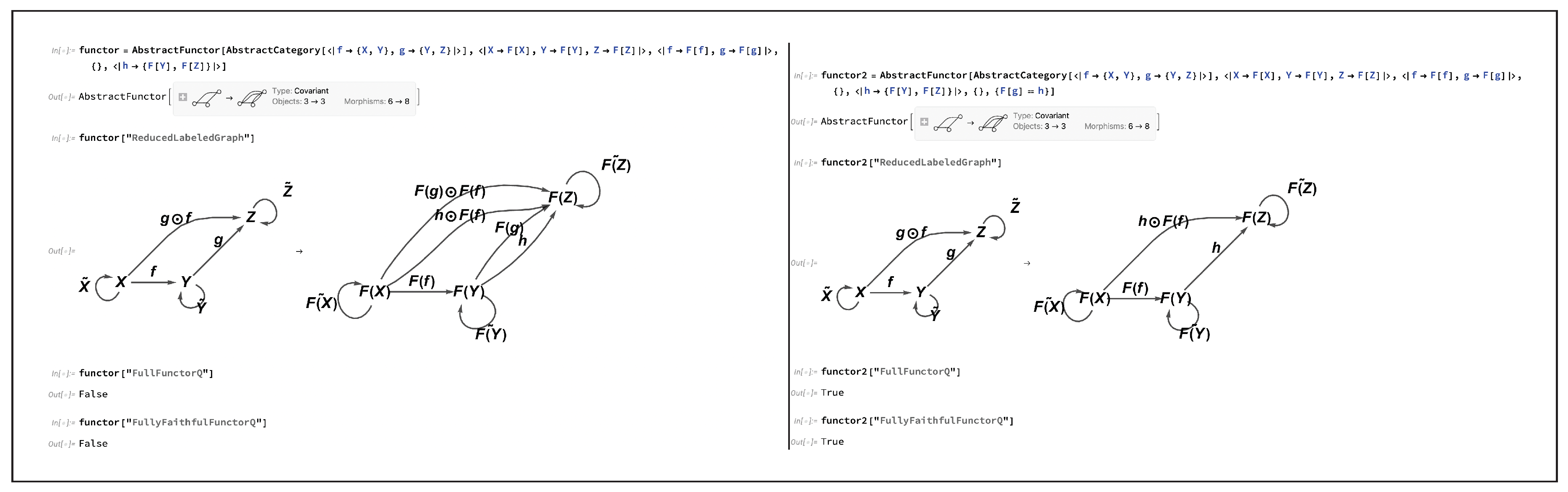

For instance, if we consider the following simple functor from a three-object, six-morphism

total category to another three-object, six-morphism

base category:

or, alternatively, the following slightly more complex functor from a four-object, ten-morphism

total category to another four-object, ten-morphism

base category:

then we see that these functors both constitute more-or-less trivial cases of (discrete) fibrations. In the former case, there are three (discrete) fiber categories, one for each object

,

and

in the base category

, and each consisting of the single object

X,

Y or

Z from the total category

(along with the corresponding identity morphism in each case), respectively; in the latter case, there are instead four (discrete) fiber categories, one for each object

,

,

and

in the base category

, and each consisting of the single object

X,

Y,

Z or

W from the total category

(along with the corresponding identity morphism in each case), respectively. This is illustrated in

Figure 25, in which CATEGORICA correctly identifies that the relevant

AbstractFunctor objects are both discrete fibrations, and proceeds to compute the relevant fiber categories (represented as an association of

AbstractCategory objects - one for each object in the codomain/base category of the fibration). In the first instance, imposing the additional algebraic equivalence

on objects in the codomain category now yields a fibration over a two-object, five-morphism base category:

while, in the second instance, imposing the additional algebraic equivalences

and

on objects in the codomain category yields instead a fibration over a two-object, eight-morphism base category:

These fibrations are still discrete, but now in the former case there are only two discrete fiber categories: one for object

in the base category

, consisting of the single object

X from the total category

(along with its identity morphism

), and one for object

in the base category

, consisting of the pair of objects

Y and

Z from the total category

(along with their respective identity morphisms

and

). In the latter case there are now also only two discrete fiber categories: one for object

in the base category

, consisting of the single object

X from the total category

(along with its identity morphism

), and one for object

in the base category

, consisting of the triple of objects

Y,

Z and

W from the total category

(along with their respective identity morphisms

,

and

). Once again, these discrete fiber categories can be computed automatically, directly from the

AbstractFunctor objects in CATEGORICA, as shown in

Figure 26. Finally, we may consider applying, in the first instance, the additional algebraic equivalence

on morphisms in the codomain category, thus yielding the following fibration over a two-object, four-morphism base category:

or alternatively, in the second instance, the additional algebraic equivalences:

on morphisms in the codomain category, thus yielding the following fibration over a two-object, six-morphism base category:

The resulting fibrations are no longer discrete, since in the former case the fiber category for object

in the base category

now contains a morphism

connecting the pair of objects

Y and

Z from the total category

, and in the latter case the fiber category for object

in the base category

now contains a pair of morphisms

and

connecting the triple of objects

Y,

Z and

W from the total category

, as seen in the explicit CATEGORICA implementation in

Figure 27. These examples make manifest the precise relationship between category-theoretic fibrations and topological ones: if one considers categories whose objects are points and whose morphisms are paths between those points, then the abstract definition of a Grothendieck fibration reduces concretely to the classical definition a fiber bundle, with the total category

being the total space, the base category

being the base space, and the fiber categories

being the fibers for each point

X in the base.

There exist many other standard features and properties of functors that are currently supported within CATEGORICA, and that can be computed automatically using the

AbstractFunctor function, including several that can be effectively assembled as “composites” of the various features/properties already discussed above. For instance, a functor yielding an

equivalence of categories (detectable through the

“EquivalenceFunctorQ” property) is one that is simultaneously fully faithful

and essentially surjective; an

embedding functor (detectable through the

“EmbeddingFunctorQ” property) is one that is simultaneously faithful

and injective on objects; and a

full embedding functor (detectable through the

“FullEmbeddingFunctorQ” property) is one that is both

fully faithful and injective on objects. An

embedding of a category

into a category

via the embedding functor

may be thought of as being a weaker/more lax version of an

inclusion of a

subcategory into a

supercategory, i.e. a functor

such that the object and morphism sets of the domain category

form (potentially improper) subsets of the respective object and morphism sets of the codomain category

:

just as an

equivalence between categories

and

may be thought of as being a weaker/more lax version of a strict

equality of categories (wherein the object and morphism sets of categories

and

are required to be strictly identical). Indeed, strict inclusions of subcategories into supercategories are also detectable, by means of the

“InclusionFunctorQ” property in

AbstractFunctor (along with the slightly stronger case in which the inclusion functor is also required to be full, detectable through the

“FullInclusionFunctorQ” property). Other common types of functors that CATEGORICA contains specialized functionality for handling as part of the

AbstractFunctor framework include

endofunctors (i.e. functors mapping a domain category

to itself) via the

“EndofunctorQ” property,

identity functors (i.e. a trivial, much stronger case of an endofunctor in which every object and morphism in the domain category

is mapped to itself) via the

“IdentityFunctorQ” property,

constant functors (i.e. functors mapping every object in the domain category

to some fixed object

X in the codomain category

, and mapping every morphism in

to the identity morphism

on that object) via the

“ConstantFunctorQ” property, and

conservative functors (i.e. functors for which a given morphism

in the codomain category

being an isomorphism necessarily implies that the corresponding morphism

in the domain category

must also have been an isomorphism) via the

“ConservativeFunctorQ” property, etc.

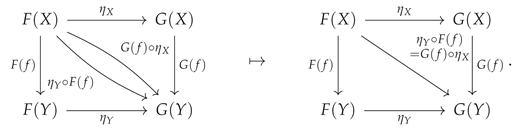

5. Natural Transformations and Algorithmic Details

Having considered above the case of homomorphisms/structure-preserving maps between categories, in the form of functors, it is now possible to consider the case of homomorphisms/structure-preserving maps between

functors, in the form of

natural transformations. More precisely, if

and

are both functors mapping between the same pair of domain/codomain categories

and

, then the map

is a natural transformation if and only if it associates every object

X in category

to a corresponding morphism

in category

:

known as the

component of the natural transformation

at

X, in such a way that, for every morphism

in category

, one has that the composition

yields the same morphism as the composition

in category

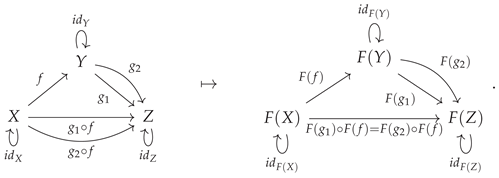

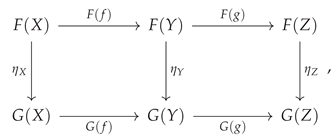

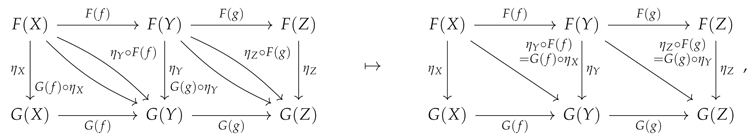

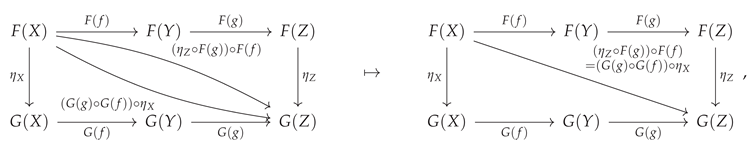

, i.e:

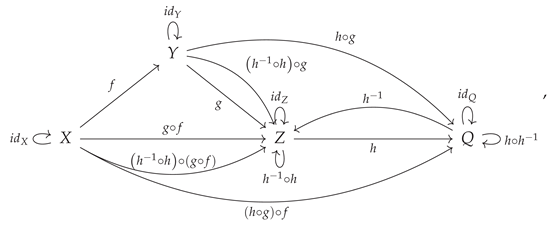

which can be illustrated simply by means of the following commutative diagram (which therefore commutes in category

):

Natural transformations abstract and generalize many powerful results and constructions in mathematics, especially in algebraic topology, perhaps most notably the Hurewicz theorem/Hurewicz homomorphism relating homotopy groups and homology groups of spaces: both the construction of homotopy groups and the construction of homology groups over a (pointed) topological space may be formalized as functors from the category

of pointed topological spaces and continuous functions between them, to the category

of groups and group homomorphisms, with the Hurewicz homomorphism being elegantly represented as a natural transformation between these two functors (and the Hurewicz theorem corresponding to the statement that such a natural transformation necessarily exists). In linear algebra and functional analysis, the relationship between the double-dual

of a vector space

V and the original space constitutes another familiar example of a commonplace natural transformation in mathematics; the double-dual operation may be formalized as an endofunctor on the category

of vector spaces and linear maps (i.e. a functor from

to itself), and there necessarily exists a natural transformation between this double-dual functor and the identity functor on

. For the case of finite-dimensional vector spaces, this natural transformation becomes a

natural isomorphism (a stronger case, to be defined momentarily).

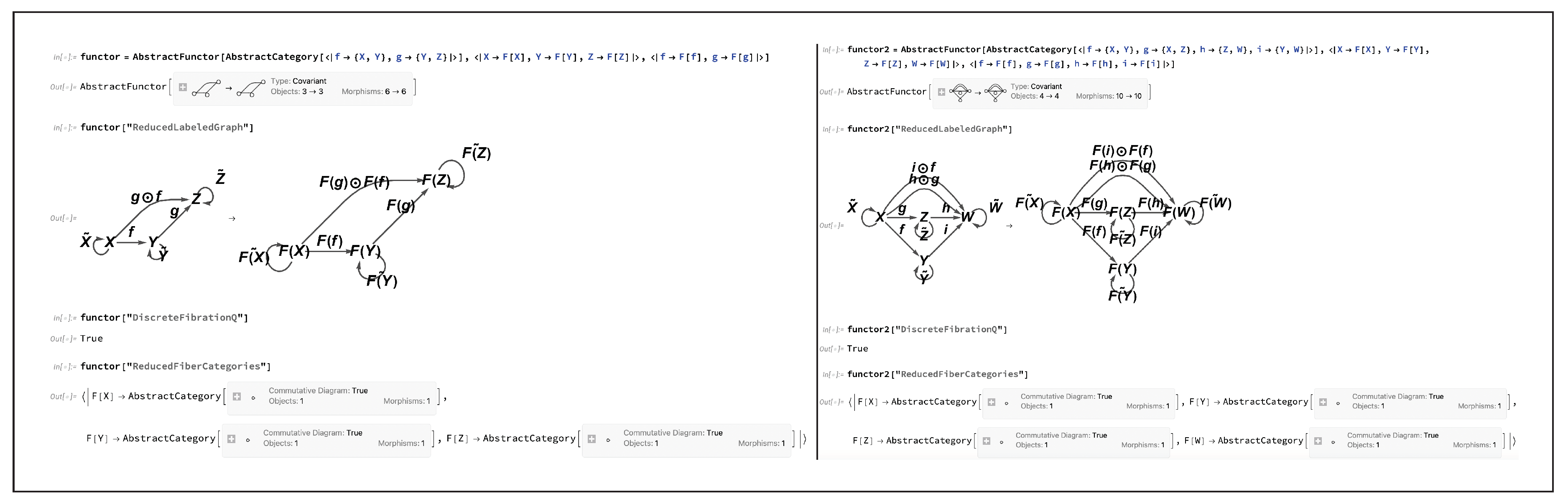

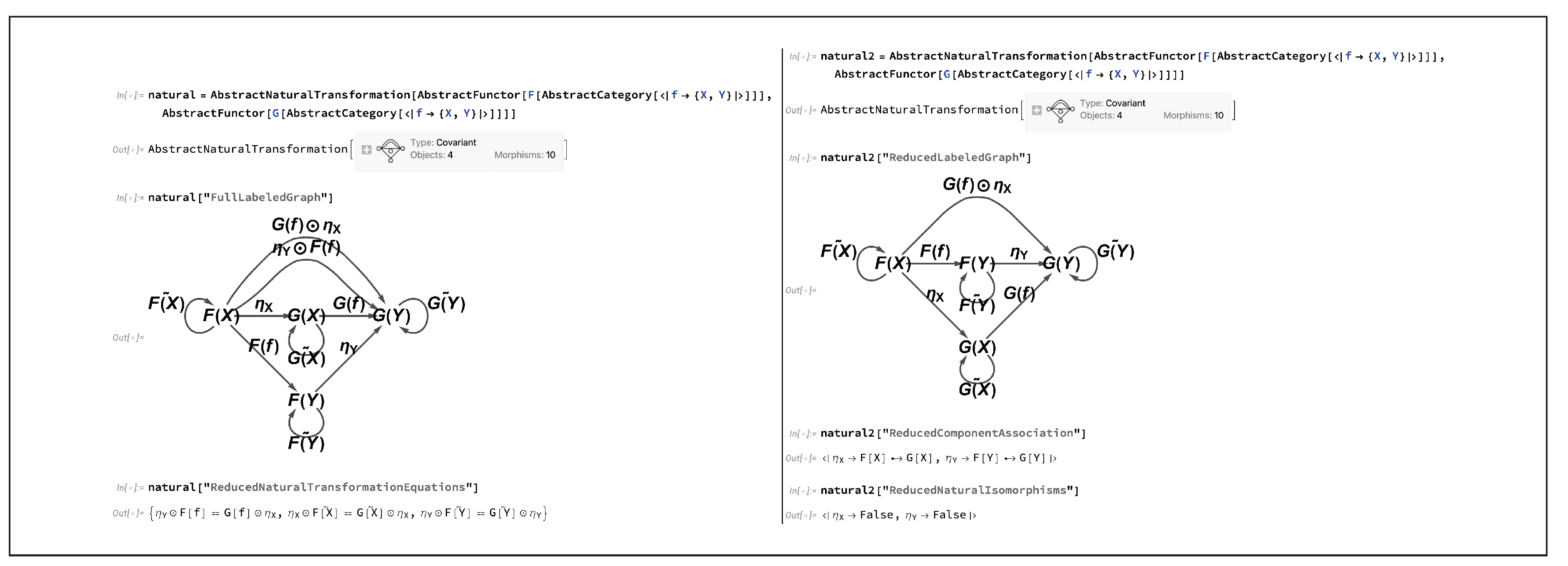

CATEGORICA is able to represent arbitrary natural transformations between

AbstractFunctor objects using the

AbstractNaturalTransformation function. In particular, it is able to compute the minimum set of algebraic equivalences between component morphisms that is necessary in order for a particular transformation between

AbstractFunctor objects to be natural, and to represent these equivalences in both equational and (commutative) diagrammatic form, as illustrated in

Figure 28 for the minimal case presented above, in which one considers a natural transformation between a pair of functors

and

acting on a common domain category

consisting of a pair of objects

X and

Y and a single morphism

, i.e. one has:

and:

respectively, in which the minimum algebraic condition for naturality is precisely the one given above:

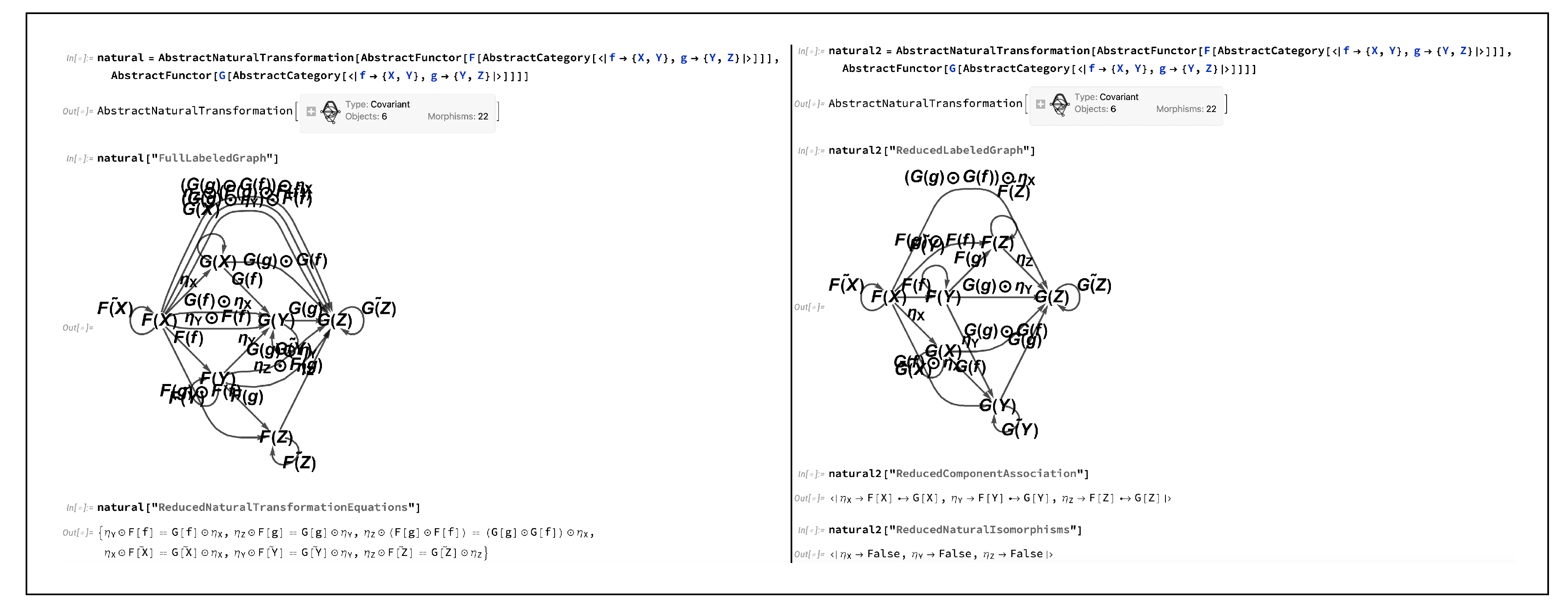

plus a couple of corollary conditions on the identity morphisms. However, although this particular example is especially simple, one does not need to increase the size or complexity of the underlying categories and functors involved very much before the resulting naturality conditions become rather unwieldy to manipulate by hand. For instance, let us consider the next most obvious example, in which the common domain category

of the functors

and

consists instead of three objects

X,

Y and

Z, along with a pair of composable morphisms

and

, i.e. one now has:

and:

respectively. In this case, the relevant commutative diagram characterizing the natural transformation

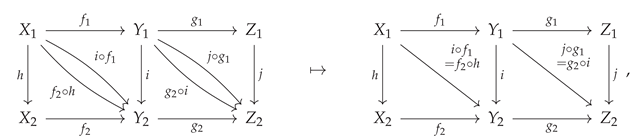

becomes instead the commutative oblong:

wherein the two interior squares must both commute:

i.e:

in addition to the outer rectangle:

i.e:

plus all corresponding conditions on the identity morphisms. As shown in

Figure 29, CATEGORICA is nevertheless easily able to represent, and to perform automatic computations involving, these more complex cases of natural transformations too.

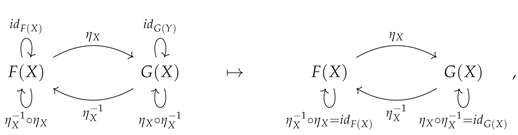

Figure 28 and

Figure 29 also demonstrate CATEGORICA’s ability to detect

natural isomorphisms: components

of the natural transformation

that are also isomorphisms, i.e. where the inverse morphism

also exists in the codomain category

, such that

is the identity morphism on

and

is the identity morphism on

:

i.e:

In addition to individual objects in the codomain category

being naturally isomorphic, one can also speak of a pair of functors

and

themselves as being naturally isomorphic: if

all components

are natural isomorphisms (for every object

X in the domain category

), then the natural transformation

itself is known as a natural isomorphism between functors:

The intuition underlying the concept of natural isomorphisms between functors can be precisely formalized by considering the

functor category (assuming that

and

are arbitrary small categories), whose objects are given by the functors

and whose morphisms are given by the natural transformations

between such functors, wherein all isomorphisms between objects represent natural isomorphisms between functors. To determine whether a given

AbstractNaturalTransformation object in CATEGORICA represents a natural isomorphism between functors, one can use the

“NaturalIsomorphismQ” property. CATEGORICA is also able to determine whether the codomain categories

between the two functors actually match (via the

“MatchingCodomainsQ” property), and therefore whether the

AbstractNaturalTransformation object does indeed represent a valid natural transformation (via the

“ValidNaturalTransformationQ” property), meaning

both that the two codomain categories match

and that the defining algebraic conditions of a natural transformation hold within those codomain categories.

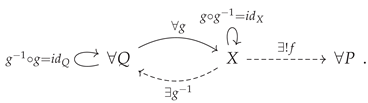

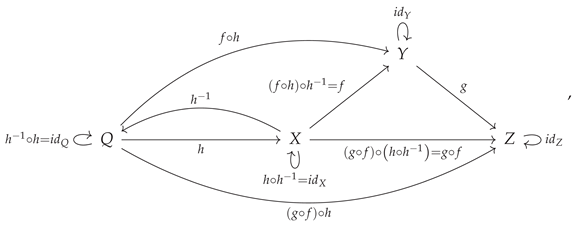

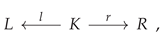

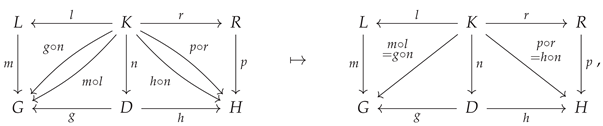

Finally, it is worth noting that all of CATEGORICA’s core algebraic and diagrammatic reasoning algorithms are represented internally in terms of (hyper)graph rewriting systems over labeled graph representations of quivers and categories, whereby one formalizes (hyper)graph rewriting rules as

spans of monomorphisms [

31,

32]:

i.e. pairs of monomorphisms which share a common domain object

K. Here, the ambient category

in which these monomorphisms exist is the category whose objects are (hyper)graphs and whose morphisms are (hyper)graph inclusion relations. In the above, object

L represents the (hyper)graph pattern appearing on the left-hand/input side of the rule, object

R represents the (hyper)graph pattern appearing on the right-hand/output side of the rule (i.e. the pattern intended to replace pattern

L wherever it appears), and object

K represents the “residual” sub(hyper)graph pattern shared by both patterns

L and

R that remains invariant after the left-hand-side

L pattern has been “extracted”, but before the right-hand-side pattern

R has been “injected”. Such a rewriting rule may then be said to

match a given (hyper)graph object

G if there exists a morphism

in the category

. The resulting (hyper)graph

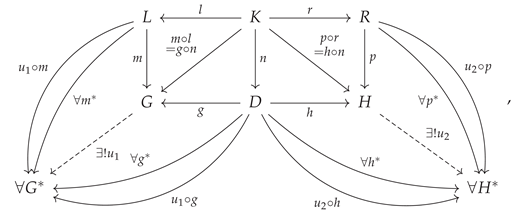

H obtained via application of the rewriting rule at this particular match may consequently be computed explicitly by completing the following

double-pushout diagram [

33]:

i.e. one must proceed to find objects

D and

H, and morphisms

n,

p,

g and

h, in the category

, such that the diagram above commutes:

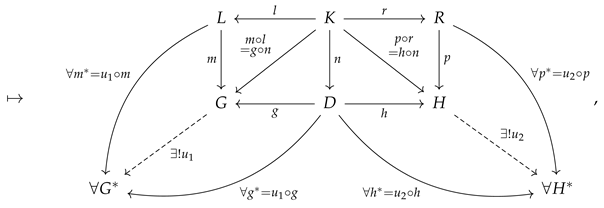

Furthermore, these objects and morphisms (and therefore, in particular, the object

H representing the resulting (hyper)graph) are guaranteed to be unique, up to natural isomorphism, by virtue of the following

universal property of the double-pushout diagram:

which then collapses down to:

i.e. for any other objects

and

, and morphisms

,

,

and

, in the category

, such that the resulting squares commute:

there necessarily exists a pair of unique morphisms

and

such that the diagram above commutes, i.e:

and:

CATEGORICA is able to exploit the formalism of double-pushout (hyper)graph rewriting in order to convert automatically between potentially slow, tedious algebraic computations and fast, explicit diagrammatic ones. To this end, the core of CATEGORICA’s hypergraph rewriting system has been built on top of the Gravitas computational general relativity framework [

51,

52] (which has previously been applied to the study of black hole physics [

53,

54,

55] and algebraic quantum field theory [

56]), which employs a bespoke suite of highly optimized, and massively parallelized, algorithms for rewriting large hypergraphs subject to generic algebraic constraints. We note also that such rewriting systems, especially in the

multiway/non-deterministic case, admit an elegant mathematical description in terms of higher categories and (higher) homotopy types [

57,

58].

Figure 1.

On the left, the AbstractQuiver object for a simple (three-object, two-arrow) quiver. On the right, the AbstractCategory object for the three-object, six-morphism category that is freely generated by this quiver.

Figure 1.

On the left, the AbstractQuiver object for a simple (three-object, two-arrow) quiver. On the right, the AbstractCategory object for the three-object, six-morphism category that is freely generated by this quiver.

Figure 2.

On the left, the AbstractCategory object for a simple (four-object, ten-morphism) category, showing all algebraic equivalences between morphisms that must hold by virtue of the identity and associativity axioms of category theory. On the right, the AbstractCategory object for a slightly larger (five-object, fifteen-morphism) category, again showing all algebraic equivalences between morphisms that must hold by virtue of the identity and associativity axioms of category theory.

Figure 2.

On the left, the AbstractCategory object for a simple (four-object, ten-morphism) category, showing all algebraic equivalences between morphisms that must hold by virtue of the identity and associativity axioms of category theory. On the right, the AbstractCategory object for a slightly larger (five-object, fifteen-morphism) category, again showing all algebraic equivalences between morphisms that must hold by virtue of the identity and associativity axioms of category theory.

Figure 3.

On the left, the AbstractCategory object for a simple category with the object equivalence specified, showing the labeled graph representations of the category both with and without algebraic equivalences imposed. On the right, the AbstractCategory object for a simple category with the morphism equivalence specified, showing the labeled graph representations of the category both with and without algebraic equivalences imposed.