1. Introduction

Animal models remain indispensable in neuroscience, offering mechanistic clarity and acting as scaffolds for therapeutic innovation that human studies alone cannot provide [

1,

2]. In narcolepsy—a chronic vigilance-state disorder typified by excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) and, in its classic form, cataplexy—such models have translated behavioural phenotypes to cellular and circuit mechanisms with profound impact [

1,

3]. The first formal clinical descriptions by Westphal (1877) and Gélineau (1880) distinguished narcolepsy from epilepsy on the basis of sudden, emotion-triggered loss of muscle tone in the presence of intact awareness.

For much of the 20th century, the diagnosis of narcolepsy rested on the “narcoleptic tetrad”: irresistible daytime sleep episodes, cataplexy, hypnagogic hallucinations, and sleep paralysis [

3,

4,

5]. While cataplexy remains diagnostic of type 1 narcolepsy (NT1), the clinical heterogeneity—especially in type 2 narcolepsy (NT2) and pediatric populations—continues to challenge diagnostic certainty [

6]. Insights from sleep science, including the delineation of distinct neurobiological substrates and the two-process model of sleep regulation, recast narcolepsy as fundamentally a disorder of REM regulation. Patients manifest not only EDS and disrupted nocturnal sleep, but also sleep-onset REM periods (SOREMs)—a pathological intrusion of REM features into wakefulness [

7].

This conceptual framing has evolved into a broader paradigm of arousal-state instability, in which the physiological boundaries separating wakefulness, non–REM, and REM states become increasingly blurred. Although patients retain homeostatic responses—such as rebound slow-wave activity after sleep deprivation—they often exhibit attenuated circadian amplitude and impaired arousal-promoting drive [

8]. Diagnostic methods, such as the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT), continue to stratify a spectrum from NT1, characterized by cataplexy and hypocretin deficiency, to NT2, where hypocretin is preserved but instability in vigilance states predominates [

9]. Nevertheless, diagnostic ambiguity persists, indicating that biomarker innovation and refined phenotyping remain urgent priorities [

10].

Animal models have played a central role in elucidating the function of the hypocretin (orexin) system in regulating sleep–wake balance [

1] (

Table 1). Naturally occurring canine narcoleptics, bearing mutations in the hypocretin receptor 2 gene, first established a link between receptor dysfunction and cataplexy [

11]. Knockout models (prepro-orexin null mice) and toxin-mediated ablation models (orexin/ataxin-3 transgenics) later confirmed that both peptide loss and neuronal cell death reproduce core narcoleptic features [

12,

13]. More sophisticated tools—optogenetic and chemogenetic control of hypocretin neurons, Cre-driven ablation, and immune-mediated ablation in Orexin-HA mice—now permit a causal dissection of sleep–wake microcircuits [

8,

14]. Nevertheless, no single model wholly emulates human narcolepsy: rodent systems often exaggerate cataplexy frequency, canine models display polyphasic sleep patterns, and none fully mirror the subtler NT2 phenotypes.

These translational limitations are stark: therapeutic strategies derived from models focused on cataplexy may fail in real-world patients, where NT2 and mixed phenotypes are more prevalent. Overcoming this gap demands a paradigm shift. Going forward, the field must develop immune-mediated models that recapitulate the proposed autoimmune aetiology of NT1 [

9], partial-loss models mapping graded hypocretin deficiency to phenotypic spectra, and regenerative strategies—for example, astrocyte-to-neuron reprogramming [

15] or iPSC-derived hypothalamic organoids [

1,

16]—to reconstitute or protect hypocretin signalling. Such steps chart a trajectory from symptomatic models to mechanistic tools and ultimately to disease-modifying interventions.

By critically examining existing animal systems and contrasting them with emerging techniques, comparative species, and regenerative modalities, this narrative review highlights both strengths and translational blind spots in narcolepsy modelling. Closing these gaps will sharpen mechanistic insight and accelerate the translation of discoveries into therapies that restore or protect hypocretin circuits. In doing so, narcolepsy can shift from a lifelong symptomatic disorder toward a target for curative or preventative intervention.

Table 1.

Comparative overview of animal models of narcolepsy.

Table 1.

Comparative overview of animal models of narcolepsy.

| Model |

Altered genotype |

Narcoleptic-like phenotype†

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

Ref. |

| Sleep-wake fragmentation |

SOREMs |

Wakefulness in

the active phase |

Total REM time |

Cataplexy |

Obesity |

| Canine |

Mutation in OX2 gene |

+ |

+ |

↓ |

|

+ |

|

Spontaneous genetic mutation |

Cost and care; behavioural variability |

[17] |

| Murine |

Knockout |

OX-/-

|

Prepro-orexin gene knockout |

+ |

+ |

↓ |

↑ |

+ |

+ |

Replicates key narcoleptic symptoms |

Lacks the progressive degeneration |

[18] |

| OX/AT3 |

Selectively ablation of orexin cells through the expression of ataxin-3 transgene causes apoptosis. |

+ |

+ |

↓ |

↑ |

+ |

+ |

Mimics the progressive loss of orexin neurons |

Complex to establish; lacks the immune component |

[13] |

| OX1R-/-

|

Single or double knockout for orexin receptors |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

Helpful in studying the specific role of OX1R and OX2R |

Lacks progressive degeneration; less severe phenotype in single KOs |

[19] |

| OX2R-/-

|

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

|

[12] |

| OX1R-/- OX2R-/-

|

+ |

+ |

↓ |

↑ |

+ |

|

[20] |

| O/E3-/-

|

O/E3 transcription factor knockout |

+ |

+ |

↓ |

↑ |

+ |

|

Useful in studying the role of O/E3 in regulating sleep-wake controlling neurons. |

Broader developmental issues |

[21] |

| Controlled |

OX2R–TD |

loxP-flanked transcription-

disrupter gene cassette that prevents expression of OX2R |

+ |

|

↓ |

|

+ |

|

Selective and reversible disruption of OX2R in specific regions of the brain |

It does not fully replicate the whole narcolepsy phenotype |

[22] |

| OX-tTA TetO-DTA |

Induction of diphtheria toxin A (DTA) in orexin neurons via tetracycline-transactivator system (tTA) |

+ |

+ |

↓ |

↑ |

+ |

+ |

The extent and timing of neuronal ablation can be controlled; more severe

narcolepsy phenotype |

Complex to breed and manage; requires precise regulation of toxin expression |

[23] |

| Optogenetic |

OX/HaloR |

Expresses halorhodopsin (HaloR) in orexin neurons |

|

|

↓ |

|

|

|

Allows real-time control of neuronal activation or inhibition |

Involves surgical implantation of optical fibre; does not present full narcolepsy phenotype |

[24] |

| OX/Arch |

Expresses archaerhodopsin-3 (Arch) in orexin neurons |

+ |

|

↓ |

↑ |

|

+ |

[25] |

| OX-tTA TetO-ArchT |

Expresses ArchT using the tet-off (tTA) system |

+ |

|

↓ |

|

|

|

[26] |

| Immune-driven |

H1N1 infection |

Orexin neuron ablation in Rag1-/- mice through H1N1 infection |

+ |

+ |

↓ |

↑ |

|

|

Mimics autoimmune aspects of narcolepsy |

Complex to generate; potential variability in immune response; limited immune system representation |

[27] |

| OX-HA |

Expresses hemagglutinin (HA) as a neo-self-antigen in orexin neurons |

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

[28] |

|

†Present (+); increased (↑); decreased (↓). |

2. Neurochemical Imbalances in Canine Narcolepsy: Insights from Pharmacology

Narcoleptic phenotypes have been documented across several mammalian species, including horses, cattle, sheep, and cats; however, the first systematically characterized case occurred in a Dachshund, which prompted William Dement to establish a colony of narcoleptic dogs at Stanford University. This resource encompassed multiple breeds, including Doberman Pinschers, Labrador Retrievers, Miniature Poodles, Dachshunds, Beagles, and Saint Bernards, providing a unique preclinical platform for mechanistic studies and therapeutic exploration [

29]. Although narcoleptic manifestations were broadly conserved, marked differences in severity, age at onset, and disease progression were noted across breeds, highlighting the genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity of the disorder [

30].

Polysomnographic investigations revealed that narcoleptic dogs retained largely normal baseline sleep architecture but displayed recurrent sleep-onset REM periods (SOREMs) and frequent cataplexy, often triggered by positive emotions such as play or food anticipation. Although the high baseline sleep requirements of dogs initially obscured recognition of excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), systematic studies confirmed that narcoleptic animals exhibited increased drowsiness, reduced locomotor activity, fragmented sleep, and shortened sleep latencies under homeostatic challenge conditions [

31].

Breeding experiments further clarified the heritability of canine narcolepsy. In large breeds, the familial form was mapped to an autosomal recessive locus, canarc-1, whereas inheritance in other breeds proved more complex. The establishment of a genetically stable colony at Stanford enabled systematic pharmacological, neurochemical, electrophysiological, and genetic investigations, providing an unparalleled resource for testing candidate therapies [

29,

32]. These studies converged on a model in which canine narcolepsy arises from brainstem neurochemical imbalances, characterized by reduced monoaminergic tone in concert with heightened cholinergic sensitivity. This framework advanced understanding of cataplexy pathophysiology and guided pharmacological interventions targeting neurotransmitter systems, including the refinement of stimulant and anticataplectic treatments [

3].

3. Identifying the Genetic Defect in Canine Narcolepsy: Mutation in the Hypocretin-2 Receptor

In parallel, advances in human narcolepsy research have highlighted its strong association with the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II allele HLA-DR2, and subsequently with DQB1*06:02 and DQA1*01:02, alleles carried by the vast majority of patients compared to a minority of the general population [

9]. These robust genetic associations supported an autoimmune basis for narcolepsy, suggesting selective immune-mediated destruction of hypocretin-producing neurons.

Canine research proved equally transformative. Although initial studies did not establish a link between canarc-1 and MHC class II loci, the creation of a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) library from a backcrossed Doberman pinscher heterozygous for canarc-1 ultimately identified a mutation in the hypocretin-2 receptor (OX2R) gene as the causal defect [

11]. This discovery provided direct evidence that impaired hypocretin signalling alone is sufficient to generate narcoleptic phenotypes. More importantly, it consolidated the hypocretin (orexin) system as a fundamental regulator of sleep–wake stability, offering a molecular framework that bridged animal and human narcolepsy.

These insights underscore the enduring translational value of canine narcolepsy. By linking neurochemical imbalance with receptor-level defects, canine studies not only informed pharmacological approaches but also provided a conceptual template for immune and regenerative strategies now under investigation. As the field moves beyond symptom control, models that capture both the immune-mediated aetiology of narcolepsy type 1 (NT1) and the subtler phenotypes of narcolepsy type 2 (NT2) will be essential for driving a paradigm shift towards disease-modifying interventions.

4. Hypocretin and Narcolepsy

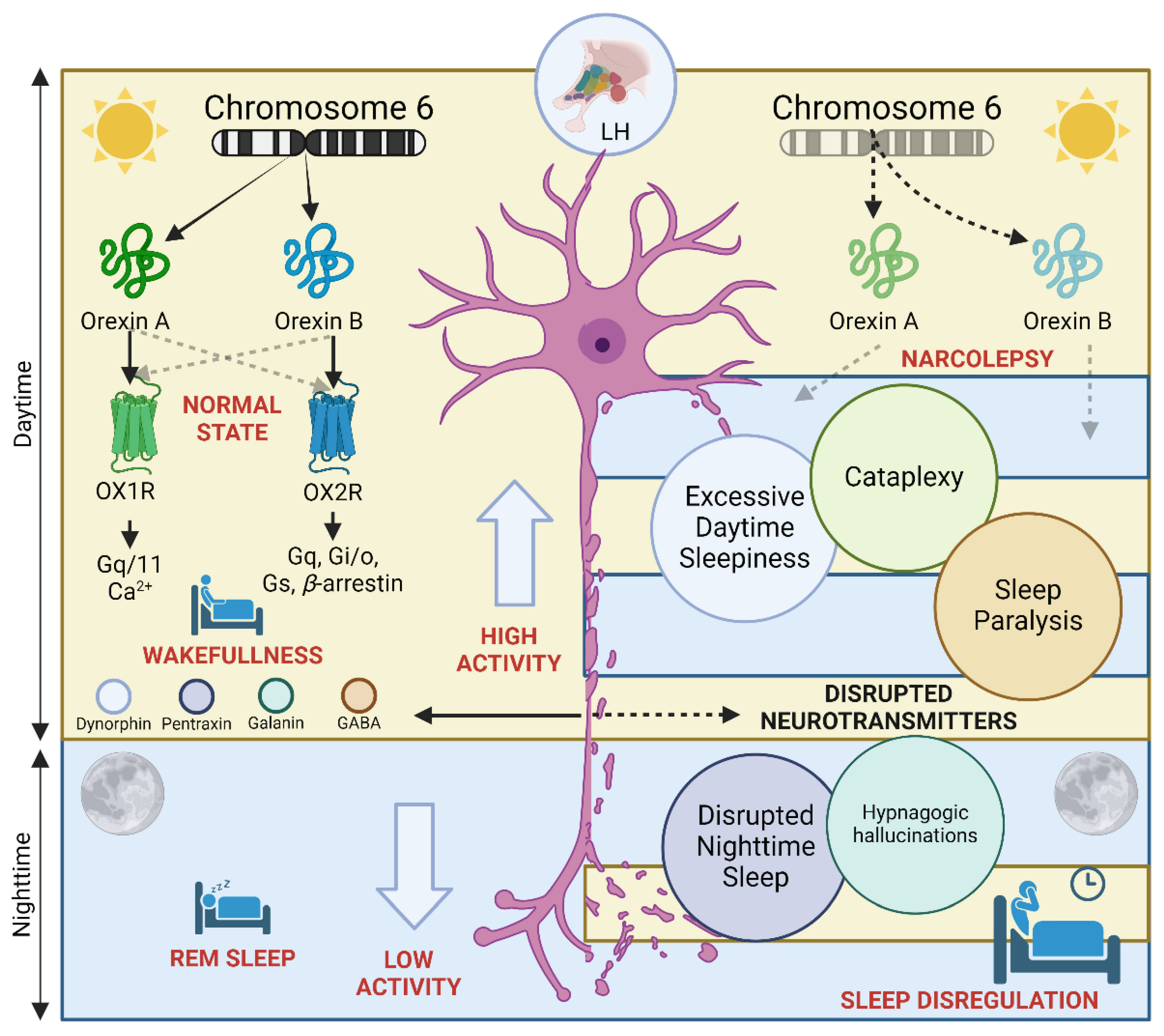

4.1. Orexin Receptors and Their Ligands: Molecular Foundations of Arousal Regulation

The discovery of the hypocretin (orexin) system in 1998 marked a decisive turning point in sleep research. Using subtractive hybridization from rat hypothalamus, two previously unknown excitatory neuropeptides were identified: hypocretin-1 and hypocretin-2 (later termed orexin-A and orexin-B). Independently, another group demonstrated that these peptides act as endogenous ligands for two orphan G-protein–coupled receptors and stimulate feeding behaviour [

33,

34]. These receptors were named orexin receptor 1 (OX1R/HcrtR1), which displays preferential affinity for orexin-A, and orexin receptor 2 (OX2R/HcrtR2), which binds both peptides with comparable strength [

35] (

Figure 1).

Hypocretin neurons are localized within the perifornical hypothalamus and the lateral hypothalamic area, but they project widely across the central nervous system. Their axons innervate key arousal and reward centres, including the locus coeruleus, dorsal raphe nuclei, basal forebrain, amygdala, nucleus accumbens, and suprachiasmatic nucleus, as well as brainstem cholinergic nuclei and spinal cord circuits [

36,

37]. This extensive connectivity establishes hypocretin signalling as a master regulator of vigilance, stabilizing behavioural states and coordinating transitions between wakefulness, non-REM, and REM sleep.

4.2. Hypocretin Neurons as Integrators of Wakefulness Circuitry

The hypothalamus was implicated in arousal regulation almost a century ago, when von Economo observed that lesions in the posterior hypothalamus were associated with hypersomnolence in encephalitis lethargica. The identification of hypocretin neurons consolidated this link, positioning the hypothalamus as a central hub for sustaining wakefulness [

38] (

Figure 1).

Wake-promoting monoaminergic neurons in the brainstem contribute to cortical desynchronization and suppress REM-active pontine neurons, while cholinergic neurons of the basal forebrain and pons promote cortical activation during both wake and REM sleep [

39]. Hypocretin neurons innervate and excite these populations, integrating arousal-promoting mechanisms into a coherent network [

40]. Loss of hypocretin function destabilizes this system: canine narcolepsy models with mutations in OX2R show profound state instability, providing compelling evidence that hypocretin signalling is indispensable for maintaining consolidated wakefulness and orderly transitions across vigilance states [

11,

34].

4.3. Towards a Paradigm Shift

Understanding the hypocretin system has redefined narcolepsy as a disorder of arousal network instability, rather than merely a REM sleep dysregulation. This framework offers a powerful translational platform: while receptor mutations in canines illuminated the molecular basis of state fragmentation, recent human studies implicate immune-mediated loss of hypocretin neurons in narcolepsy type 1, with genetic and environmental factors modulating vulnerability [

7,

9]. Looking forward, therapies aimed at restoring hypocretin tone—through small molecules, gene therapy, or stem cell–derived hypothalamic transplants—hold the potential to transform narcolepsy from a chronic, symptomatic condition into a treatable or preventable disorder [

1].

5. Murine Models of Narcolepsy

5.1. Sleep Attacks and Narcoleptic Phenotypes in Prepro-Orexin Knockout Mice

Soon after cloning of the hypocretin/orexin gene, deletion of prepro-orexin in mice yielded the first robust murine model of narcolepsy, establishing a genetic foothold for mechanistic inquiry [

18]. EEG/EMG recordings later resolved initial behavioural arrests during the dark phase as narcolepsy-like features—sleep-onset REM periods (SOREMs), severe sleep–wake fragmentation, and increased sleepiness during the active period—together with gait ataxia [

3,

18]. These data showed that perturbation of a single neuropeptide system can reorganize vigilance states at scale, positioning the hypocretin system at the core of arousal stability [

38].

Concurrently, naturally occurring canine narcolepsy was traced to mutations in the Hcrtr2 gene. The cross-species convergence—presynaptic loss of hypocretin peptides in mice and postsynaptic OX2R dysfunction in dogs—established that impaired hypocretin signalling, at either node, is sufficient to produce narcoleptic phenotypes [

11,

12] (

Figure 1).

5.2. Post-Mortem and Biomarker Evidence in Humans

Translation to the clinic accelerated once CSF hypocretin-1/orexin-A testing showed undetectable or markedly reduced levels in most patients with type 1 narcolepsy (NT1), enabling a biologically anchored distinction from type 2 narcolepsy (NT2) [

41,

42]. Post-mortem studies confirmed a profound, selective loss of hypocretin neurons in NT1, with preservation of neighbouring melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH) neurons and gliosis in the hypocretin cell region [

43,

44]. Together, these data cemented hypocretin deficiency as the pathogenic substrate in human NT1 and defined a measurable biomarker (CSF orexin-A ≤110 pg/mL) with direct diagnostic utility [

41,

42].

5.3. The Orexin/Ataxin-3 (ATAX) Model: Neuronal Ablation and Disease Evolution

Because prepro-orexin knockout mice lack the peptides but retain hypocretin neurons, orexin/ataxin-3 (ATXN3) mice were created to ablate hypocretin neurons selectively. ATAX mice develop progressive degeneration, mirroring human disease evolution, and display the cardinal features of narcolepsy—fragmented sleep–wake cycles, SOREMs, obesity despite reduced intake, and cataplexy—with inter-individual variability in episode frequency and duration [

13,

23].

5.4. Receptor Genetics: Parsing OX1R and OX2R Contributions

Receptor-specific models clarify pathway anatomy. Hcrtr1/OX1R knockout mice show relatively mild abnormalities without frank cataplexy, whereas Hcrtr2/OX2R knockout mice exhibit more severe narcolepsy-like phenotypes, including cataplexy. Dual OX1R/OX2R knockouts exhibit robust cataplexy and SOREMs, underscoring the complementary roles of both receptors, with OX2R serving as the dominant mediator of sleep–wake stability [

12,

22]. These distinctions provide a mechanistic rationale for OX2R-selective agonists now in clinical development.

6. Other Rodent Models Informing Pathogenesis

6.1. O/E3 and Hypocretin Lineage Differentiation

The helix–loop–helix transcription factor O/E3 (EBF2) participates in hypothalamic neuronal differentiation and is expressed in hypocretin neurons. O/E3-null mice show marked loss of hypocretin neurons, disrupted hypocretinergic projections to sleep–wake nuclei, fragmented sleep, and SOREMs—phenotypes reversed by intracerebroventricular hypocretin-1, indicating that the sleep disorder arises from hypocretin-lineage failure rather than global developmental defects [

21,

45].

6.2. Autoimmunity, HLA, and T-Cell Biology

Genetic studies consistently associate NT1 with HLA-DQB1*06:02 (and DQA1*01:02) and with polymorphisms in the T-cell receptor α (TRA) locus, suggesting a role in antigen presentation and T-cell surveillance [

9]. Epidemiology following the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic—natural infection in China and exposure to the AS03-adjuvanted vaccine (Pandemrix) in parts of Europe—showed an increased incidence of narcolepsy, supporting the immune hypothesis [

46,

47]. Mechanistically, Orex-HA mice—a model expressing hemagglutinin as a neo-self antigen in hypocretin neurons—develop narcolepsy-like phenotypes following adoptive transfer of antigen-specific CD8

+ T cells, demonstrating that cytotoxic T cells can ablate hypocretin neurons in vivo [

48]. In patients, autoreactive CD4

+ and CD8

+ T cells targeting hypocretin-neuron antigens have been identified, thereby consolidating a T cell–mediated pathogenesis in NT1 [

49,

50].

6.3. Distinct Yet Intertwined: MCH and Hypocretin Neurons

Although anatomically intermingled, MCH and hypocretin neurons exert opposite influences on vigilance. Pharmacological and optogenetic studies demonstrate that MCH neurons promote REM (and variably NREM) sleep and facilitate NREM-to-REM transitions; conversely, inhibition or ablation can reduce REM stability or induce partial insomnia, with effects on hippocampus-dependent memory [

24,

26,

51,

52]. These data locate MCH neurons as modulators of REM dynamics and memory processing.

6.4. Dual Ablation of Hypocretin and MCH Neurons

To probe circuit interactions, OXMC mice lacking both hypocretin and MCH neurons display more severe narcoleptic phenotypes—profound sleep fragmentation, increased cataplexy, and abnormal EEG signatures—than hypocretin-only ablations, implying that MCH pathways can buffer or shape symptom severity [

53].

6.5. Translational Inflexion: From Models to Disease Modification

Receptor-level insights have catalyzed therapeutics that restore orexin tone. Intravenous danavorexton (TAK-925), an OX2R-selective agonist, improves objective and subjective sleepiness and vigilance across models and early human studies; oral oveporexton (TAK-861) has shown Phase 2 efficacy in NT1 with clinically meaningful reductions in EDS and cataplexy, marking a shift from symptomatic control to mechanistically targeted therapy [

54,

55]. Future directions include immunomodulatory strategies guided by T-cell biology and regenerative approaches (e.g., stem-cell–derived hypothalamic lineages) to reconstitute hypocretin signalling [

38,

56].

7. Discussion

Animal models have been pivotal in establishing the hypocretin/orexin system as the fulcrum of sleep–wake stability, reproducing key features such as fragmented sleep, sleep-onset REM periods (SOREMs), cataplexy, and—in some paradigms—weight gain without hyperphagia [

38,

56]. Nevertheless, each model interrogates only a slice of the syndrome (

Table 2). Optogenetic and chemogenetic tools afford millisecond precision over hypocretin neurons but risk reducing a chronic, degenerative disorder to a reversible “on–off” perturbation that lacks ecological validity [

38,

56]. By contrast, neuron-ablation paradigms (for example, orexin/ataxin-3 or conditional diphtheria-toxin systems) better mirror the progressive loss and its network consequences, although degeneration is still driven by artificial temporal control and constrained by species-specific sleep architecture [

13,

23,

53].

Translational blind spots persist. Canine models have historically been transformative, but their use is complicated by polyphasic sleep, which limits direct comparison to human nocturnal consolidation. Rodents, with intrinsically fragmented sleep, present similar challenges. Most importantly, preclinical readouts often over-privilege cataplexy. While cataplexy is pathognomonic for NT1, it is uncommon across the day in many NT1 patients and absent in NT2. Overreliance on cataplexy as the principal endpoint risks skewing therapeutic discovery toward a single, exaggerated phenotype rather than the broader clinical spectrum that includes excessive daytime sleepiness, vigilance instability, and cognitive or autonomic burden [

4].

A conspicuous gap is the absence of models that faithfully recapitulate NT2. Clinically, NT2 is defined by EDS with typical SOREMs but no cataplexy; nocturnal sleep can be relatively preserved, and REM latencies are longer than in NT1 [

57]. Biomarker and post-mortem observations suggest that NT2 may involve partial hypocretin dysfunction rather than near-complete loss [

57]. Existing partial-loss or partial-suppression paradigms are informative, but they either still express cataplexy or fail to capture the phenotypic nuances of NT2. Purpose-built models that titrate hypocretin tone to intermediate levels—and assay outcomes beyond cataplexy—are therefore essential to extend therapeutic discovery across the full disease spectrum [

3,

57].

Contemporary management remains symptomatic mainly. Wake-promoting agents, anticonvulsant therapies, and oxybate formulations improve function but do not address the loss of hypocretin neurons. Two converging avenues now enable a mechanistic pivot. First, OX2R-selective agonists restore downstream signalling independent of cell replacement. Intravenous danavorexton (TAK-925) produced rapid wake promotion in translational studies and early human trials [

54], and the oral agonist oveporexton (TAK-861) yielded Phase 2 improvements in wakefulness and cataplexy in NT1, signalling a shift from symptomatic stimulation to circuit-specific rescue [

55]. Second, regenerative and circuit-repair strategies—including stem-cell–derived hypothalamic lineages and glial reprogramming—are advancing preclinically and could, in time, rebuild hypocretin tone rather than merely pharmacologically emulate it [

1].

Convergent genetic, epidemiologic, and cellular data support a T-cell–mediated pathogenesis in NT1, anchored by HLA-DQB1*06:02 and T-cell receptor associations, with infection or vaccination as modulators of risk [

9,

47]. Human studies have identified autoreactive CD4

+ and CD8

+ T cells targeting hypocretin-neuron antigens [

49,

50]. Causality has been modelled directly: adoptive transfer of antigen-specific CD8

+ T cells ablates hypocretin neurons and induces a narcolepsy-like phenotype in Orexin-HA mice [

48]. Immune-relevant models should now be mainstreamed to dissect the cascade from genetic susceptibility to neuronal loss, identify windows for prevention, and test immunomodulatory interventions alongside receptor agonism.

Progress will depend on aligning models with the heterogeneity of human disease. NT2-focused paradigms, immune-competent models that capture T-cell effector mechanisms, and partial-loss systems calibrated to intermediate hypocretin deficits are priorities. Equally, preclinical endpoints must expand beyond cataplexy to include objective wakefulness, vigilance stability, cognition, and autonomic outcomes—mirroring patient-centred clinical trials [

54,

55]. Together, these steps will transform animal systems from partial mirrors into robust translational platforms, accelerating a shift from symptomatic management to disease-modifying or preventive therapy.

5. Conclusions

Animal models have been indispensable in establishing the hypocretin/orexin system as a central regulator of sleep–wake stability and in clarifying the pathophysiology of narcolepsy. From canine studies that revealed receptor mutations to murine models that demonstrated peptide loss and neuronal degeneration, these systems have progressively shaped our mechanistic understanding. More recent immune-mediated and regenerative paradigms now highlight the complexity of narcolepsy type 1 as an autoimmune disorder and underscore the need for models that faithfully capture narcolepsy type 2, where hypocretin function is only partially impaired.

Despite their limitations, preclinical models continue to guide therapeutic discovery. OX2R-selective agonists, gene therapy approaches, and regenerative strategies are beginning to move the field beyond symptomatic relief toward disease modification. Parallel integration of immune-relevant models, patient-derived hypothalamic organoids, and multi-omics technologies offers a path to refine patient stratification and to identify opportunities for prevention.

Looking ahead, the next phase of narcolepsy research will depend on aligning animal models with the heterogeneity of human disease, expanding preclinical endpoints beyond cataplexy, and testing interventions that restore or protect hypocretin tone. By bridging immune, regenerative, and computational approaches, narcolepsy research is poised to transition from descriptive modeling to precision medicine, with the long-term prospect of transforming a chronic symptomatic disorder into a preventable and potentially curable condition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, and writing—original draft preparation, O.A.-C. and E.O-R; writing—review and editing, O.A.-C. and E.O-R. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all colleagues and collaborators who contributed to this work. To those who consistently demonstrated the power of doing nothing — we did not wait.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| REM |

Rapid Eye Movement |

| NT1 |

Narcolepsy Type 1 |

| NT2 |

Narcolepsy Type 2 |

| MCH |

Melanin-Concentrating Hormone |

| EDS |

Excessive Daytime Sleepiness |

| HLA |

Human Leukocyte Antigen |

| CD8 |

Cluster of Differentiation 8 (cytotoxic T cell subset) |

References

- Ortega-Robles, E.; Guerra-Crespo, M.; Ezzeldin, S.; Santana-Roman, E.; Palasz, A.; Salama, M.; Arias-Carrion, O. Orexin Restoration in Narcolepsy: Breakthroughs in Cellular Therapy. J Sleep Res 2025. [CrossRef]

- Arias-Carrion, O. Preclinical models of insomnia: advances, limitations, and future directions for drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2025, 20, 1061-1074. [CrossRef]

- Bassetti, C.L.A.; Adamantidis, A.; Burdakov, D.; Han, F.; Gay, S.; Kallweit, U.; Khatami, R.; Koning, F.; Kornum, B.R.; Lammers, G.J., et al. Narcolepsy - clinical spectrum, aetiopathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 519-539. [CrossRef]

- Kornum, B.R.; Knudsen, S.; Ollila, H.M.; Pizza, F.; Jennum, P.J.; Dauvilliers, Y.; Overeem, S. Narcolepsy. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2017, 3, 16100. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Sagili, H. Etiopathogenesis and neurobiology of narcolepsy: a review. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 2014, 8, 190-195. [CrossRef]

- Maycock, T.J.; Rossor, T.; Vanegas, M.; Gringras, P.; Jungbluth, H. Child Neurology: Common Occurrence of Narcolepsy Type 1 and Myasthenia Gravis. Neurology 2024, 103, e209598. [CrossRef]

- Vringer, M.; Zhou, J.; Gool, J.K.; Bijlenga, D.; Lammers, G.J.; Fronczek, R.; Schinkelshoek, M.S. Recent insights into the pathophysiology of narcolepsy type 1. Sleep Med Rev 2024, 78, 101993. [CrossRef]

- Latorre, D.; Sallusto, F.; Bassetti, C.L.A.; Kallweit, U. Narcolepsy: a model interaction between immune system, nervous system, and sleep-wake regulation. Semin Immunopathol 2022, 44, 611-623. [CrossRef]

- Ollila, H.M.; Sharon, E.; Lin, L.; Sinnott-Armstrong, N.; Ambati, A.; Yogeshwar, S.M.; Hillary, R.P.; Jolanki, O.; Faraco, J.; Einen, M., et al. Narcolepsy risk loci outline role of T cell autoimmunity and infectious triggers in narcolepsy. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 2709. [CrossRef]

- Stephansen, J.B.; Olesen, A.N.; Olsen, M.; Ambati, A.; Leary, E.B.; Moore, H.E.; Carrillo, O.; Lin, L.; Han, F.; Yan, H., et al. Neural network analysis of sleep stages enables efficient diagnosis of narcolepsy. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 5229. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Faraco, J.; Li, R.; Kadotani, H.; Rogers, W.; Lin, X.; Qiu, X.; de Jong, P.J.; Nishino, S.; Mignot, E. The sleep disorder canine narcolepsy is caused by a mutation in the hypocretin (orexin) receptor 2 gene. Cell 1999, 98, 365-376. [CrossRef]

- Willie, J.T.; Chemelli, R.M.; Sinton, C.M.; Tokita, S.; Williams, S.C.; Kisanuki, Y.Y.; Marcus, J.N.; Lee, C.; Elmquist, J.K.; Kohlmeier, K.A., et al. Distinct narcolepsy syndromes in Orexin receptor-2 and Orexin null mice: molecular genetic dissection of Non-REM and REM sleep regulatory processes. Neuron 2003, 38, 715-730. [CrossRef]

- Hara, J.; Beuckmann, C.T.; Nambu, T.; Willie, J.T.; Chemelli, R.M.; Sinton, C.M.; Sugiyama, F.; Yagami, K.; Goto, K.; Yanagisawa, M., et al. Genetic ablation of orexin neurons in mice results in narcolepsy, hypophagia, and obesity. Neuron 2001, 30, 345-354. [CrossRef]

- Bonvalet, M.; Ollila, H.M.; Ambati, A.; Mignot, E. Autoimmunity in narcolepsy. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2017, 23, 522-529. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Lai, X.; Liang, X.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Xu, W.; Qin, Q.; Qin, R.; Huang, X.; Xie, M., et al. A promise for neuronal repair: reprogramming astrocytes into neurons in vivo. Biosci Rep 2024, 44. [CrossRef]

- Merkle, F.T.; Maroof, A.; Wataya, T.; Sasai, Y.; Studer, L.; Eggan, K.; Schier, A.F. Generation of neuropeptidergic hypothalamic neurons from human pluripotent stem cells. Development 2015, 142, 633-643. [CrossRef]

- Nishino, S. Canine models of narcolepsy. In The Orexin/Hypocretin System: Physiology and Pathophysiology, Nishino, S., Sakurai, T., Eds. Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2006; pp. 233-253. [CrossRef]

- Chemelli, R.M.; Willie, J.T.; Sinton, C.M.; Elmquist, J.K.; Scammell, T.; Lee, C.; Richardson, J.A.; Williams, S.C.; Xiong, Y.; Kisanuki, Y., et al. Narcolepsy in orexin knockout mice: molecular genetics of sleep regulation. Cell 1999, 98, 437-451. [CrossRef]

- Kisanuki, Y.; Chemelli, R.; Sinton, C.; Williams, S.; Richardson, J.; Hammer, R.; Yanagisawa, M. The role of orexin receptor type-1 (OX1R) in the regulation of sleep. Sleep 2000, 23, A91.

- Kisanuki, Y.Y.; Chemelli, R.M.; Tokita, S.; Willie, J.T.; Sinton, C.M.; Yanagisawa, M. Behavioral and polysomnographic characterization of orexin-1 receptor and orexin-2 receptor double knockout mice. Sleep 2001, 24, A22.

- De La Herrán-Arita, A.K.; Zomosa-Signoret, V.C.; Millán-Aldaco, D.A.; Palomero-Rivero, M.; Guerra-Crespo, M.; Drucker-Colín, R.; Vidaltamayo, R. Aspects of the narcolepsy-cataplexy syndrome in O/E3-null mutant mice. Neuroscience 2011, 183, 134-143. [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, T.; Arrigoni, E.; Marcus, J.N.; Clark, E.L.; Yamamoto, M.; Honer, M.; Borroni, E.; Lowell, B.B.; Elmquist, J.K.; Scammell, T.E. Orexin receptor 2 expression in the posterior hypothalamus rescues sleepiness in narcoleptic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108, 4471-4476. [CrossRef]

- Tabuchi, S.; Tsunematsu, T.; Black, S.W.; Tominaga, M.; Maruyama, M.; Takagi, K.; Minokoshi, Y.; Sakurai, T.; Kilduff, T.S.; Yamanaka, A. Conditional ablation of orexin/hypocretin neurons: a new mouse model for the study of narcolepsy and orexin system function. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 6495-6509. [CrossRef]

- Tsunematsu, T.; Kilduff, T.S.; Boyden, E.S.; Takahashi, S.; Tominaga, M.; Yamanaka, A. Acute optogenetic silencing of orexin/hypocretin neurons induces slow-wave sleep in mice. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 10529-10539. [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.H.; Tsunematsu, T.; Thomas, A.M.; Bogyo, K.; Yamanaka, A.; Kilduff, T.S. Transgenic Archaerhodopsin-3 Expression in Hypocretin/Orexin Neurons Engenders Cellular Dysfunction and Features of Type 2 Narcolepsy. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 9435-9452. [CrossRef]

- Tsunematsu, T.; Tabuchi, S.; Tanaka, K.F.; Boyden, E.S.; Tominaga, M.; Yamanaka, A. Long-lasting silencing of orexin/hypocretin neurons using archaerhodopsin induces slow-wave sleep in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2013, 255, 64-74. [CrossRef]

- Tesoriero, C.; Codita, A.; Zhang, M.D.; Cherninsky, A.; Karlsson, H.; Grassi-Zucconi, G.; Bertini, G.; Harkany, T.; Ljungberg, K.; Liljeström, P., et al. H1N1 influenza virus induces narcolepsy-like sleep disruption and targets sleep-wake regulatory neurons in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113, E368-377. [CrossRef]

- Bernard-Valnet, R.; Yshii, L.; Quériault, C.; Nguyen, X.H.; Arthaud, S.; Rodrigues, M.; Canivet, A.; Morel, A.L.; Matthys, A.; Bauer, J., et al. CD8 T cell-mediated killing of orexinergic neurons induces a narcolepsy-like phenotype in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113, 10956-10961. [CrossRef]

- Mignot, E.J. History of narcolepsy at Stanford University. Immunol Res 2014, 58, 315-339. [CrossRef]

- Black, J.; Reaven, N.L.; Funk, S.E.; McGaughey, K.; Ohayon, M.M.; Guilleminault, C.; Ruoff, C. Medical comorbidity in narcolepsy: findings from the Burden of Narcolepsy Disease (BOND) study. Sleep Med 2017, 33, 13-18. [CrossRef]

- Nishino, S.; Okura, M.; Mignot, E. Narcolepsy: genetic predisposition and neuropharmacological mechanisms. REVIEW ARTICLE. Sleep Med Rev 2000, 4, 57-99. [CrossRef]

- Mignot, E. Genetic and familial aspects of narcolepsy. Neurology 1998, 50, S16-22. [CrossRef]

- de Lecea, L.; Kilduff, T.S.; Peyron, C.; Gao, X.; Foye, P.E.; Danielson, P.E.; Fukuhara, C.; Battenberg, E.L.; Gautvik, V.T.; Bartlett, F.S., 2nd, et al. The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998, 95, 322-327. [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, T.; Amemiya, A.; Ishii, M.; Matsuzaki, I.; Chemelli, R.M.; Tanaka, H.; Williams, S.C.; Richardson, J.A.; Kozlowski, G.P.; Wilson, S., et al. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell 1998, 92, 573-585. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Q.; Ji, B.; Pan, Y.; Xu, C.; Cheng, B.; Bai, B.; Chen, J. The Orexin/Receptor System: Molecular Mechanism and Therapeutic Potential for Neurological Diseases. Front Mol Neurosci 2018, 11, 220. [CrossRef]

- Mahler, S.V.; Smith, R.J.; Moorman, D.E.; Sartor, G.C.; Aston-Jones, G. Multiple roles for orexin/hypocretin in addiction. Prog Brain Res 2012, 198, 79-121. [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, T.; Kurimoto, E.; Joyal, A.A.; Koike, T.; Kimura, H.; Scammell, T.E. An orexin agonist promotes wakefulness and inhibits cataplexy through distinct brain regions. Curr Biol 2025, 35, 2088-2099 e2084. [CrossRef]

- Scammell, T.E. Narcolepsy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2654-2662. [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.E.; Basheer, R.; McKenna, J.T.; Strecker, R.E.; McCarley, R.W. Control of sleep and wakefulness. Physiol Rev 2012, 92, 1087-1187. [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, J.G.; de Lecea, L. The hypocretins: setting the arousal threshold. Nat Rev Neurosci 2002, 3, 339-349. [CrossRef]

- Ripley, B.; Overeem, S.; Fujiki, N.; Nevsimalova, S.; Uchino, M.; Yesavage, J.; Di Monte, D.; Dohi, K.; Melberg, A.; Lammers, G.J., et al. CSF hypocretin/orexin levels in narcolepsy and other neurological conditions. Neurology 2001, 57, 2253-2258. [CrossRef]

- Postiglione, E.; Barateau, L.; Pizza, F.; Lopez, R.; Antelmi, E.; Rassu, A.L.; Vandi, S.; Chenini, S.; Mignot, E.; Dauvilliers, Y., et al. Narcolepsy with intermediate cerebrospinal level of hypocretin-1. Sleep 2022, 45. [CrossRef]

- Thannickal, T.C.; Moore, R.Y.; Nienhuis, R.; Ramanathan, L.; Gulyani, S.; Aldrich, M.; Cornford, M.; Siegel, J.M. Reduced number of hypocretin neurons in human narcolepsy. Neuron 2000, 27, 469-474. [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.; Linssen, S.; Harteman, Z.; den Dekker, F.; Shuker, L.; Balesar, R.; Breesuwsma, N.; Anink, J.; Zhou, J.; Lammers, G.J., et al. Activated Wake Systems in Narcolepsy Type 1. Ann Neurol 2023, 94, 762-771. [CrossRef]

- Tisdale, R.K.; Yamanaka, A.; Kilduff, T.S. Animal models of narcolepsy and the hypocretin/orexin system: Past, present, and future. Sleep 2021, 44. [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.; Andrews, N.; Stellitano, L.; Stowe, J.; Winstone, A.M.; Shneerson, J.; Verity, C. Risk of narcolepsy in children and young people receiving AS03 adjuvanted pandemic A/H1N1 2009 influenza vaccine: retrospective analysis. BMJ 2013, 346, f794. [CrossRef]

- Sarkanen, T.O.; Alakuijala, A.P.E.; Dauvilliers, Y.A.; Partinen, M.M. Incidence of narcolepsy after H1N1 influenza and vaccinations: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 2018, 38, 177-186. [CrossRef]

- Bernard-Valnet, R.; Yshii, L.; Queriault, C.; Nguyen, X.H.; Arthaud, S.; Rodrigues, M.; Canivet, A.; Morel, A.L.; Matthys, A.; Bauer, J., et al. CD8 T cell-mediated killing of orexinergic neurons induces a narcolepsy-like phenotype in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, 10956-10961. [CrossRef]

- Latorre, D.; Kallweit, U.; Armentani, E.; Foglierini, M.; Mele, F.; Cassotta, A.; Jovic, S.; Jarrossay, D.; Mathis, J.; Zellini, F., et al. T cells in patients with narcolepsy target self-antigens of hypocretin neurons. Nature 2018, 562, 63-68. [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, N.W.; Holm, A.; Kristensen, N.P.; Bjerregaard, A.M.; Bentzen, A.K.; Marquard, A.M.; Tamhane, T.; Burgdorf, K.S.; Ullum, H.; Jennum, P., et al. CD8(+) T cells from patients with narcolepsy and healthy controls recognize hypocretin neuron-specific antigens. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 837. [CrossRef]

- Konadhode, R.R.; Pelluru, D.; Blanco-Centurion, C.; Zayachkivsky, A.; Liu, M.; Uhde, T.; Glen, W.B., Jr.; van den Pol, A.N.; Mulholland, P.J.; Shiromani, P.J. Optogenetic stimulation of MCH neurons increases sleep. J Neurosci 2013, 33, 10257-10263. [CrossRef]

- Izawa, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Miyazaki, T.; Mukai, Y.; Ono, D.; Inoue, R.; Ohmura, Y.; Mizoguchi, H.; Kimura, K.; Yoshioka, M., et al. REM sleep-active MCH neurons are involved in forgetting hippocampus-dependent memories. Science 2019, 365, 1308-1313. [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.J.; Ono, D.; Kilduff, T.S.; Yamanaka, A. Dual orexin and MCH neuron-ablated mice display severe sleep attacks and cataplexy. Elife 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.; Kimura, H.; Alexander, R.; Davies, C.H.; Faessel, H.; Hartman, D.S.; Ishikawa, T.; Ratti, E.; Shimizu, K.; Suzuki, M., et al. Orexin 2 receptor-selective agonist danavorexton improves narcolepsy phenotype in a mouse model and in human patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119, e2207531119. [CrossRef]

- Dauvilliers, Y.; Plazzi, G.; Mignot, E.; Lammers, G.J.; Del Rio Villegas, R.; Khatami, R.; Taniguchi, M.; Abraham, A.; Hang, Y.; Kadali, H., et al. Oveporexton, an Oral Orexin Receptor 2-Selective Agonist, in Narcolepsy Type 1. N Engl J Med 2025, 392, 1905-1916. [CrossRef]

- Scammell, T.E. The neurobiology, diagnosis, and treatment of narcolepsy. Ann. Neurol. 2003, 53, 154-166. [CrossRef]

- van der Hoeven, A.E.; Fronczek, R.; Schinkelshoek, M.S.; Roelandse, F.W.C.; Bakker, J.A.; Overeem, S.; Bijlenga, D.; Lammers, G.J. Intermediate hypocretin-1 cerebrospinal fluid levels and typical cataplexy: their significance in the diagnosis of narcolepsy type 1. Sleep 2022, 45. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).