1. Introduction

Biomethane, currently defined as methane obtained through the fermentation of organic substrates by diverse microorganisms and recognized as a renewable fuel, has been perceived in different ways throughout history depending on the prevailing worldview. In ancient Rome, sewer systems were already used to manage stormwater and urban waste, but one consequence was the formation of sewer gases that occasionally caused explosions and “ignis fatuus”. In Roman baths, images of the goddess Fortuna and other deities were common, as they were believed to protect citizens from underground demons able to breathe fire. The existence of ventilation chimneys and primitive burners suggests that technological solutions to reduce sewer gas accumulation were already attempted at that time [

1]. In the 19th century, with the expansion of large industrial cities, the persistence of foul odors and frequent explosions or fires became a public concern. At that time, sewer gases were believed to spread diseases such as cholera and typhoid, considered major causes of mortality in new industrial centers [

2]. The hot summer of 1858 in London triggered the “Great Stink”, which led to Bazalgette’s redesign of the sewer network (1858–1870). This included ventilation chimneys and lamps using sewer gas for public lighting [

3,

4]. In this context, patents began to emerge, such as US4998 (1872), which protected a method for purifying natural and sewer gas for lamps [

5], or US158310 (1874), describing a boiler capable of burning sewer gas mixed with other fuels [

6].

From the late 19th century to the mid-20th, attempts were made to characterize sewer gas and design technologies to manage or use it. While isolated inventions are documented in patent databases, large-scale applications only appeared in the 1930s, when some German and Swiss wastewater plants produced biogas (refined sewer gas) for boilers, Otto engines, and municipal trucks. Most of these facilities were destroyed in World War II or gradually dismantled until their disappearance in the early 1960s [8]. The oil crisis of the 1970s revived interest in renewable energies under the paradigm of import substitution. As knowledge already existed on biomethane production and purification, it became one of the first renewable energies to be modernized. Unlike the 19th-century interest linked to urban sanitation, the 1970s initiatives were initially rural, using livestock manure and agricultural residues, later extending again to wastewater and municipal waste with uneven outcomes that shaped national policies and adoption [9].

In the 1980s and 1990s, the end of the Cold War and the spread of globalization and neoliberalism defined the economic order, but in parallel environmental movements began warning about climate change. These concerns gradually gained political weight, culminating in the Paris Agreement of 2015, where 195 countries committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions [10]. Today, biomethane production is a mature technology involving different biomass sources, urban residues, crops, and microalgae, and is implemented at multiple scales worldwide. Since the 1970s, technological pathways have evolved continuously with incremental innovations aimed at improving efficiency and valorizing by-products. The renewed interest in the 1970s had a strong impact on research and innovation, although the first patent of that period only appeared in 1977. During the 1980s and 1990s, fewer than 20 patents were filed annually, indicating an incubation phase. In 1997, the number rose to 29, initiating a growth stage that peaked in 2012 with 367 patents filed globally. Since 2013, a decline in annual patent numbers has been observed. Between 1990 and 2005, most patents were registered in the United States, until China overtook it after 2006. It is also noteworthy that, collectively, EU member states filed more patents between 1990 and 2022, although at the national level both the USA and China exceeded individual European countries [11].

Building upon this historical context, this paper moves toward a prospective analysis, addressing the current state of biomethane development and forecasting its future pathways in renewable energy. Since biomethane is primarily generated through anaerobic fermentation of organic matter, particular attention is given to how advances in fermentation-based processes, upgrading technologies, and system integration contribute to improving efficiency and reliability. The discussion also considers economic conditions that shape sustainability, together with the influence of regulatory and social dynamics at a global level. By examining regional experiences, technological challenges, and innovative forecasting approaches, the study aims to provide valuable insights for researchers, policymakers, and stakeholders engaged in the strategic planning of biomethane within the framework of the ongoing energy transition.

2. Present Status of Biomethane Development

Biomethane, often referred to as renewable natural gas, represents a renewable energy vector produced from a wide variety of organic substrates such as agricultural residues, municipal solid waste, and wastewater. Thanks to its origin in microbial fermentation processes, it can be applied in several fields, including transport, electricity production, and industrial operations, which explains its increasing importance in energy transitions. The worldwide market for biomethane and biogas is currently experiencing a remarkable expansion, reaching a value of US$ 89,040 million in 2022 and projected to increase to US$ 111,400 million by 2030 according to GRS [12]. This expansion follows the global orientation toward renewable energy sources and the urgent objective of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Such growth is being driven by higher investment, continuous technological progress, and favorable policy frameworks that support sustainable energy. The sector is expected to expand at a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 3.3% during the forecast period, showing resilience and long-term potential. In addition, the market is organized by segments defined by the type of feedstock, production pathways, uses, and geographical regions.

Regarding feedstocks, the biomethane sector integrates a very heterogeneous portfolio: energy crops, livestock manure, crop residues, urban waste, and other organic resources are all being employed as raw materials. This diversity underlines the flexibility of the fermentation process and the capacity of the industry to adapt to different local contexts. Production technologies range from conventional anaerobic digestion to more advanced fermentation-based systems, reflecting continuous innovation in the sector. One remarkable feature of the current market is its concentration: a small group of leading companies control nearly 95% of the share, shaping competitive dynamics and technological orientation. From a regional perspective, Asia-Pacific clearly dominates, accounting for more than 82% of the global market, a figure that illustrates both the scale of demand and the opportunities for further expansion in this region.

Within the main actors, Greenlane Renewables holds a leading position in the biomethane and biogas industry, with 140 plants deployed in 19 countries and a portfolio of three distinct upgrading solutions: membrane separation, water scrubbing, and pressure swing adsorption. This technological diversification reinforces its strategic role in the market. At the same time, Air Liquide, the French multinational, operates 21 biomethane facilities worldwide with an annual production of 1.4 TWh. Its current investment program, which in Q3 2023 registered a backlog of USD 4.44 billion, pays special attention to the US market. With two new plants under construction in this country, its production is expected to reach 1.6 TWh per year, covering the complete value chain from production and purification to liquefaction, storage, and distribution. Another significant player is Charwood Energy, which went public in June 2022 with EUR 12.4 million raised. Before its IPO, the company had developed 38 methanation units and one pyro-gasification system. Its plan is to build and operate 50 plants by 2027, reaching EUR 90 million in annual recurring revenues. With its emphasis on pyro-gasification, Charwood introduces a distinctive approach compared to conventional biogas systems. Its successful implementation of technology in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2022 reveals its potential in early-stage international markets [14].

Among different product categories, agricultural-type systems dominate, covering more than 71% of installations. With regard to end-uses, electricity generation remains the main application, accounting for more than 98% of the global market share [13]. Nevertheless, biomethane and biogas are also used for vehicle fuel and grid injection, confirming their versatility. The main drivers for this demand are the environmental advantages of substituting fossil fuels, as well as the continuous improvements in fermentation and upgrading technologies, which make the resource more efficient and reliable.

Globally, there are still wide differences in the production levels of biogas and biomethane, determined by resource availability, access to advanced fermentation-based technologies, and the existence of supportive policies (

Figure 1). Europe appears as the most important global producer, having also the second-largest biomethane market share in 2022. By 2030, the European biomethane market is projected to reach USD 26.40 billion, with a CAGR of 27.6%. This is a result of the increasing demand for renewable energy from sustainable processes such as anaerobic fermentation. Germany leads the region, with two-thirds of the operating plants, followed by the Netherlands, France, and Denmark, consolidating Europe as a pioneer. Recent initiatives, such as the provisional EU Methane Regulation agreed in November 2023, highlight the policy drive to enhance the use of crop residues, livestock manure, and landfill biogas, consolidating a clear trajectory towards sustainability.

In Asia, China has strongly promoted biomethane and biogas as part of its strategy for renewable energy and clean cooking solutions. The national plan of 2019 reinforced upgrading technologies to expand biomethane in the transport sector. In the United States, production is mainly associated with landfill gas, with future perspectives pointing toward livestock waste integration. In this case, the primary application is also transportation fuel, backed by federal incentives. In Africa, the main challenge is the access to clean cooking fuels: most rural households still rely on solid biomass like charcoal or dung, with serious health and environmental impacts. Sub-Saharan Africa accounts for one-third of the global population without clean cooking access, with five out of six people lacking alternatives. India faces a comparable situation, with heavy dependence on polluting stoves. Although some African governments and NGOs provide subsidies to promote biogas and biomethane investments, such initiatives remain scarce. Overall, the present global panorama of biomethane and biogas development reflects a very complex interaction between geographical, technological, and regulatory aspects that determine the adoption of this renewable energy [14].

Contracts and agreements are expected to create substantial opportunities for market actors in the near future, supporting the continued growth of biomethane. This evolution highlights its crucial role in satisfying the increasing global demand for renewable and environmentally friendly energy carriers.

3. Key Technologies and Process Materials

In the evolving context of biomethane development, the application of advanced technologies and the use of suitable process materials represent decisive factors for determining the direction of the sector. Biomethane production, fundamentally dependent on anaerobic fermentation of organic substrates, requires subsequent upgrading to transform raw biogas into high-quality renewable gas [15]. Among the most relevant technologies, membrane separation, water scrubbing, and pressure swing adsorption are widely implemented as standard purification routes to achieve biomethane of sufficient purity for injection into natural gas grids or for direct end use. The constant improvement of these processes and their integration with fermentation-based production lines are essential elements that explain the growing availability of biomethane in global markets. In this section, an overview is provided of the main technological options currently applied, those with promising perspectives for the future, and the typical materials associated with their operation in plants fed by anaerobic digestion.

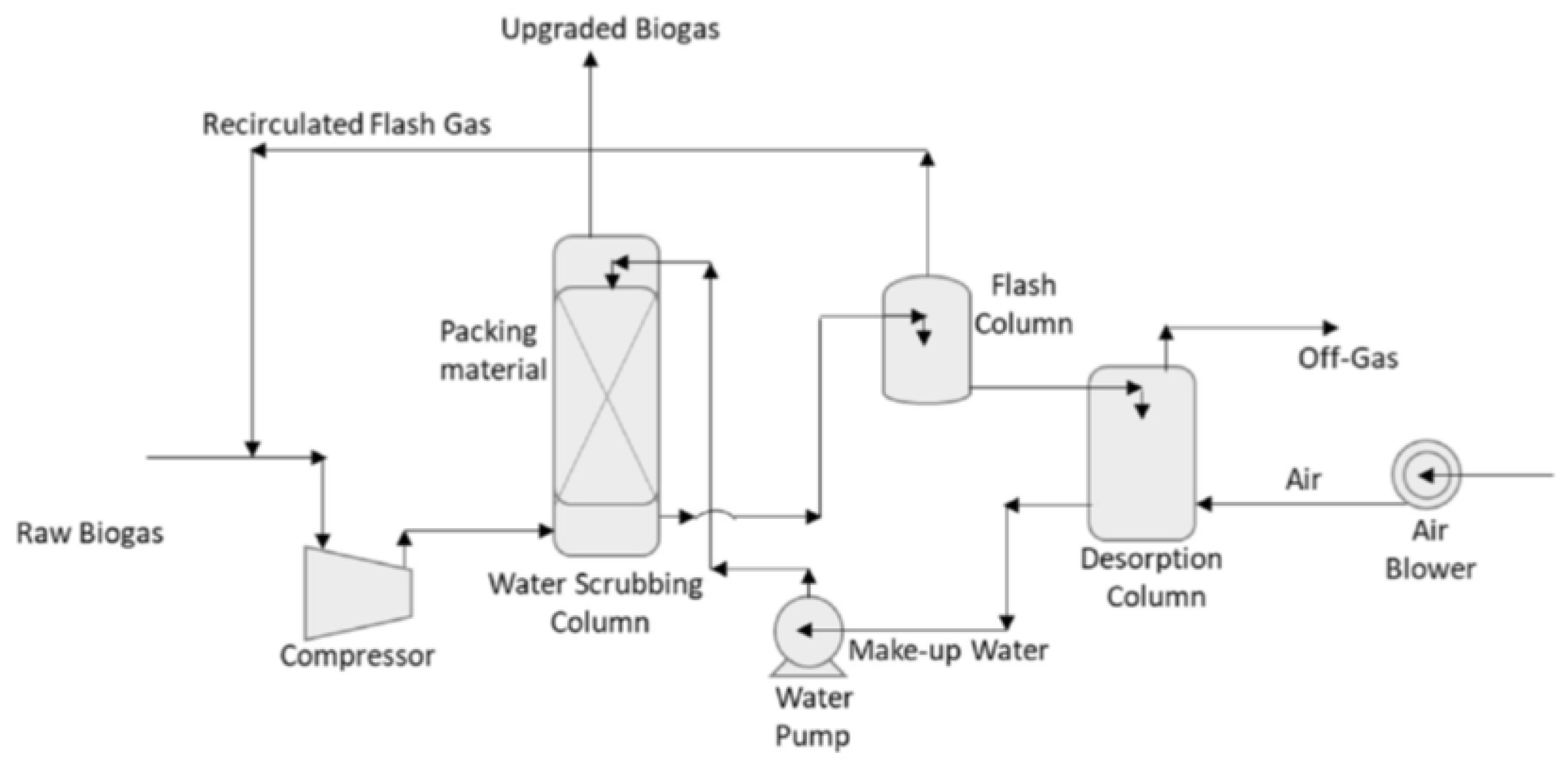

The traditional water scrubbing technique consists of contacting biogas with water to remove impurities. Through this absorption step, carbon dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, and residual trace gases are efficiently separated, generating a methane-enriched stream. It is considered a simple, low-cost, and environmentally benign approach, based on the physical solubility of CO2 and H2S in water.

Figure 2 shows a representative system [16], where the raw biogas is compressed to pressures between 8 and 20 bar before being introduced into the bottom of an absorption tower, while water is circulated from the top. The column is filled with random packing to maximize the contact surface and improve mass transfer between the gas and liquid phases. The purified biomethane exits at the top, reaching methane concentrations close to 99%, and is then subjected to a drying stage. The liquid effluent, which carries the absorbed contaminants, leaves the column from the bottom and passes through a regeneration unit before being reused. The success of this process lies in its operational simplicity and robustness, which makes it very suitable for small and medium-sized biomethane plants, even though it requires a relatively high consumption of water [17].

At present, two commercial variants of water scrubbing are available: one including solvent recovery to reduce water use, and another where the water comes directly from wastewater treatment plants. In recovery-based designs, the effluent stream is first depressurized in a flash separator (2.5–3.5 bar), producing a gas rich in CO2 and CH4 that is redirected to the compressor inlet, and a liquid fraction that enters a desorption tower before recirculation. For plants in the range of 100–1000 Nm3/h, between 20 and 200 L/h of water are purged to avoid the build-up of contaminants [16]. In these systems, the main energy demand corresponds to biogas compression and water pumping, and the biomethane produced normally reaches between 96–98% methane with losses of about 2%.

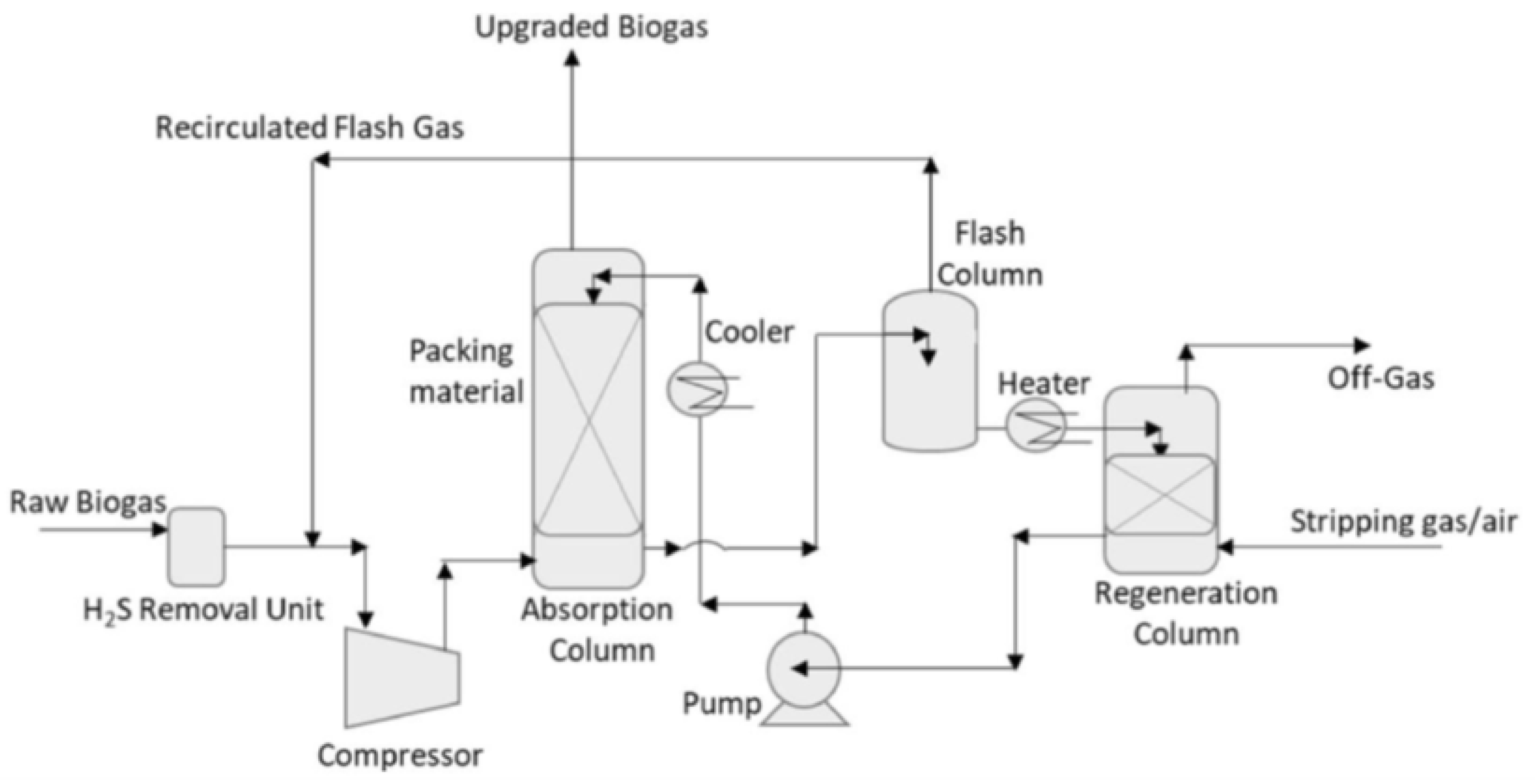

Organic scrubbing represents a similar absorption strategy, but instead of water, organic solvents are employed. The most common options are methanol and polyethylene glycol dimethyl ethers, capable of capturing CO2, H2S, and residual water vapor. This technology presents several advantages over conventional water scrubbing [18]. On one hand, the solubility of CO2 in organic solvents is higher, which allows the use of smaller solvent volumes. In addition, these solvents are anti-corrosive, reducing material degradation inside the tower, and when solvents with low vapor pressures are selected, losses during regeneration are minimized. These aspects explain why organic scrubbing is often seen as more efficient and reliable. However, a drawback is that both CO2 and H2S exhibit high solubility, which makes solvent regeneration more expensive. The regeneration process usually requires depressurization and heating to about 80 °C, followed by cooling before reinjection. When the initial biogas contains significant H2S, the regeneration system operates at higher temperatures, which increases costs. For this reason, many plants add a desulfurization step upstream of the absorption column.

Figure 3 presents a simplified scheme of the process. Organic scrubbing typically delivers biomethane with 96–98% methane purity and losses of around 2% [16]. Its main energy inputs derive from the heat for solvent regeneration and the electricity needed for compression.

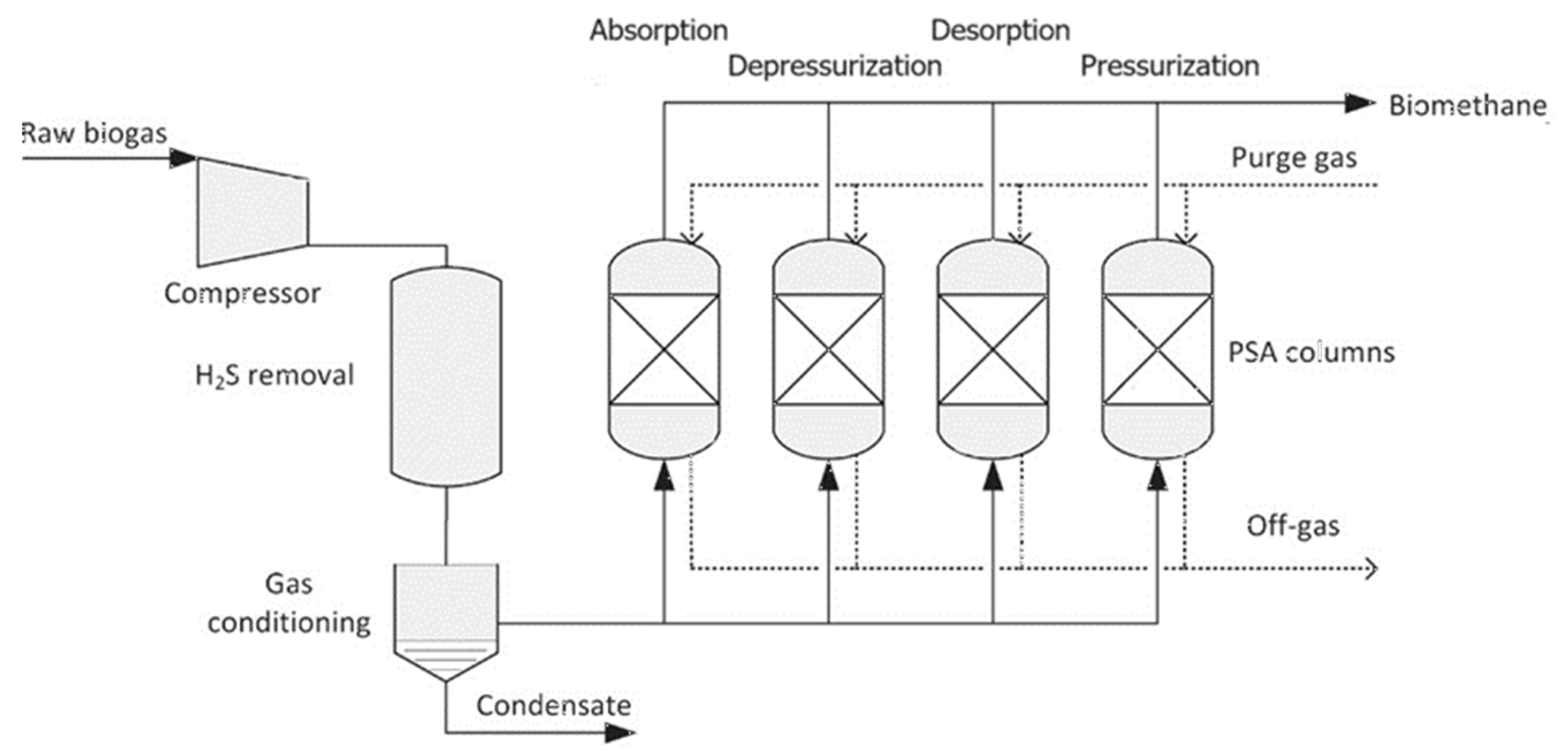

Pressure Swing Adsorption (PSA) is a cyclic separation method that makes use of the different adsorption behavior of gases under changing pressure conditions. In this process, biogas generated through fermentation is introduced into adsorption columns filled with porous materials that show strong affinity for carbon dioxide and other undesirable compounds. By alternating between compression and decompression, the adsorbent selectively captures contaminants, allowing the release of a biomethane stream with high purity. The underlying principle is a transfer of gas molecules to the adsorbent surface, controlled by van der Waals and electrostatic interactions [19]. The overall performance depends on the pore structure of the adsorbent, the partial pressure of the adsorbed species, the system temperature, and the regeneration capacity of the material. To be effective, adsorbents must combine high selectivity with thermal and mechanical resistance and be non-toxic. Materials most often used include zeolites and activated carbon.

The separation process is organized in several columns operating in parallel, each undergoing a four-step cycle to allow continuous adsorption and regeneration [20]. In the adsorption step, biogas previously desulfurized and dried is fed into the column at pressures of 6–8 bar. Under these conditions, CO

2, N

2, and O

2 are retained while methane passes through. Then the column is depressurized, first to atmospheric pressure and then under vacuum. During the regeneration or purge phase, a fraction of the purified biomethane is circulated under vacuum, which promotes the desorption of CO

2. The resulting CO

2-rich flow can be recycled if methane content is still significant, or vented after treatment when the methane fraction is low. Once regeneration is completed, the column is pressurized again to 6–8 bar and returns to the adsorption step. A conventional four-column PSA configuration (

Figure 4) can deliver biomethane with 96–97% purity and losses in the range of 2–4%. The energy requirements are modest, mainly linked to electricity for drying and compression. Limitations arise from the operational complexity and the necessity of prior removal of H

2S to avoid irreversible adsorption [21].

Another widely used approach is chemical absorption, in which biogas is purified by reaction with liquid solvents. Commonly applied absorbents include Monoethanolamine (MEA), diglycolamine (DGA), diethanolamine (DEA), triethanolamine (TEA), methyldiethanolamine (MDEA), 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol (AMP), and piperazine (PZ) [22]. In these units, biogas from fermentation is introduced at the bottom of an absorption tower, while the solvent is sprayed from the top. The reaction is exothermic, raising the temperature from about 20–40 °C to 60–80 °C, and producing intermediate species such as CO32− and HCO3− that facilitate CO2 capture. As a result, absorption towers can be more compact and solvent circulation lower. The liquid stream leaving the bottom, enriched with CO2 and H2S, is pumped to a stripping column, where solvent regeneration occurs at 1.5 bar and 120–160 °C. Biomethane obtained in this way may exceed 99% purity, with methane losses below 0.1% [23], and the absorption rate is generally faster than in physical systems. Nevertheless, the energy demand is higher than in other upgrading technologies, and increased H2S levels require higher regeneration temperatures, which again makes prior desulfurization necessary. Additional concerns include solvent toxicity, degradation of amines, and risks of corrosion, which together limit the broader deployment of this technology.

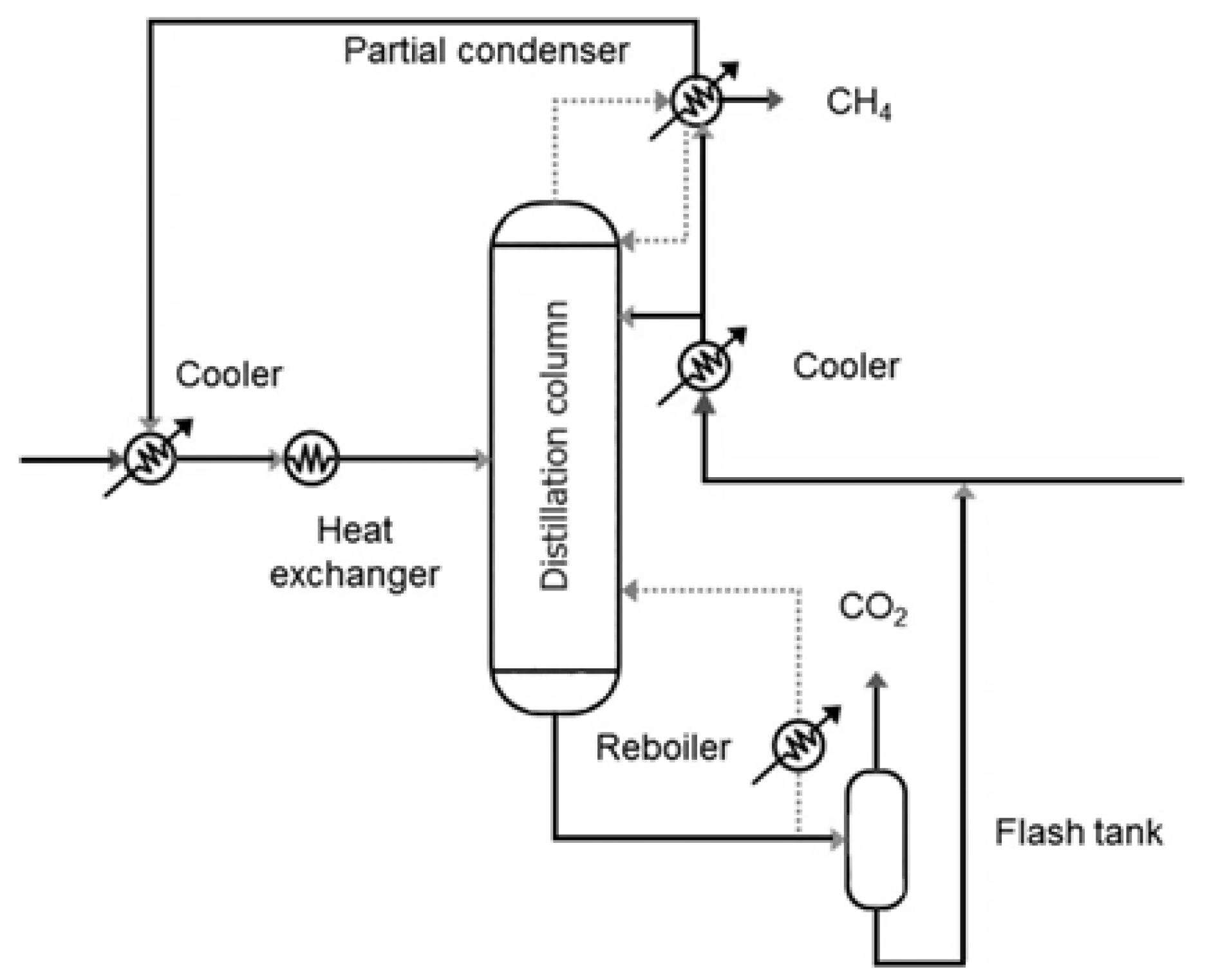

Cryogenic separation is another advanced method, based on cooling biogas to very low temperatures so that individual components condense or solidify at different points. In this way, CO2, water vapor, and other impurities can be removed, leaving high-purity biomethane. The process requires alternating stages of cooling and compression, until reaching column conditions close to 80 bar and -110 °C. Considering that methane boils at -161.5 °C and CO2 at -78.2 °C at atmospheric pressure, this difference is exploited to achieve separation. Cryogenic upgrading makes it possible to obtain biomethane with 97–98% methane content and losses under 2% [24]. However, the system is technologically complex and involves very high capital and operating costs, mainly due to the intense energy consumption. For this reason, its industrial adoption is still limited. Even so, with the progressive expansion of renewable energies, this technology is expected to gain more importance in the medium term.

Figure 5.

Biogas upgrading by cryogenic separation.

Figure 5.

Biogas upgrading by cryogenic separation.

Gas separation membranes are increasingly considered as an attractive option for biogas upgrading, since they allow the preferential permeation of certain gases while retaining others. In practice, the membranes permit the passage of CO2, H2S, water vapor, and O2, while methane and nitrogen are largely retained, which makes the technology effective for producing biomethane that complies with injection requirements for natural gas grids. Because the biogas generated by anaerobic fermentation must be purified before use, membrane-based separation has become a widely studied and applied solution, recognized for its relatively low energy demand and reduced operational costs compared to other techniques [25]. The separation principle relies on a semipermeable barrier through which molecules are transported under gradients of concentration, pressure, temperature, or electric potential.

Three main types of membranes are used in gas separation. Polymeric membranes, prepared from organic materials such as cellulose, polysulfone, polyimide, polycarbonate, or polydimethylsiloxane, dominate the market. Their advantages include high selectivity, adequate thermal resistance, ease of processing, and cost-effectiveness for large-scale production. Inorganic membranes, fabricated from materials such as zeolites, activated carbon, silica, carbon nanotubes, or metal-organic frameworks, present superior stability—thermal, chemical, and mechanical—compared with polymeric ones, although their cost is higher. A more recent development is represented by mixed matrix membranes, which combine polymeric matrices with dispersed inorganic particles, offering improved resistance and stability while retaining the processability of polymers.

For industrial application, the membranes must withstand the pressure and temperature levels of upgrading units, and also resist the chemical effects of water and H

2S present in raw biogas. Although a wide range of polymeric and inorganic options exists, industrial practice usually favors polymeric membranes due to their lower production costs. Among them, polyimide and cellulose acetate are the most widely employed. Cellulose acetate, however, is sensitive to moisture, requiring pretreatment of the gas stream to remove water vapor. The efficiency of a membrane is commonly described by its selectivity, with higher CO

2/CH

4 selectivity indicating stronger separation ability.

Table 1 summarizes the selectivity values of different polymeric membranes. Recent research has proposed new materials with outstanding properties, such as SAPO-34, showing CO

2/CH

4 selectivity values of about 120 [26]. Nevertheless, despite their excellent performance, these advanced membranes are not currently manufacturable at an industrial scale, and their widespread use is not expected in the near future.

In practical applications of biogas upgrading, the most frequently implemented membrane module designs are hollow fiber and spiral wound configurations. Hollow fiber modules consist of a pressure-resistant housing containing a large number of fine hollow fibers. One of the gas streams flows inside the fibers while the counterflow passes through the outer shell, allowing separation to take place across the fiber walls. Depending on the plant design, the feed gas can be introduced either into the housing or directly into the fibers. Spiral wound modules, in contrast, are constructed by winding flat membrane sheets around a central permeate collection tube. The permeate flows through this conduit, which acts as the axis of the spiral, while the retentate moves along the external surface. Both designs are based on polymeric membranes and are selected according to operating requirements such as flow rate, pressure, and efficiency.

Table 2.

Examples of suppliers of biogas separation membranes, their module configuration, and material employed (all polymeric). Adapted from [27].

Table 2.

Examples of suppliers of biogas separation membranes, their module configuration, and material employed (all polymeric). Adapted from [27].

| Supplier |

Module type |

Polymer materials |

| Air Liquide Medal |

Hollow fiber |

Polyimide, Polyaramid |

| Air Products |

Hollow fiber |

Polysulfone |

| Evonik |

Hollow fiber |

Polyimide |

| IGS Generon Membrane Technology |

Hollow fiber |

Polycarbonate tetrabromo |

| Kvaerner Membrane |

Spiral wound |

Cellulose acetate |

| MTR Inc. |

Spiral wound |

Perfluoropolymer, Silicone rubber |

| Parker |

Hollow fiber |

Polyphenylene oxide |

| Praxair |

Hollow fiber |

Polyimide |

| UBE Membranes |

Hollow fiber |

Polyimide |

| UOP (formerly Grace) |

Spiral wound |

Cellulose acetate |

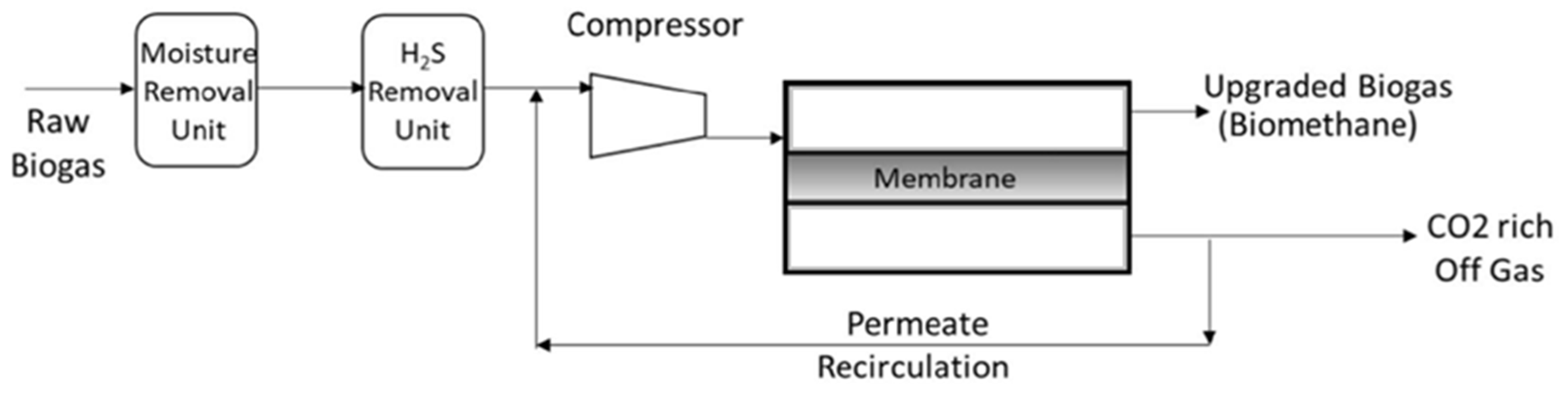

The conventional scheme of membrane separation usually involves three essential steps: preliminary cleaning of the gas, compression, and the selective separation through membranes [28]. Figure 6 presents a simplified flow scheme of a single-stage biogas purification system. Before compression, the raw gas obtained from fermentation is generally conditioned to remove water vapor and hydrogen sulfide. Eliminating moisture avoids condensation in the compressor, while H2S must be removed because membrane separation is not sufficient for this compound and, additionally, it is highly corrosive. Moisture is typically removed by cooling and condensation, while H2S is trapped using activated carbon beds. A particle filter is often included before compression to avoid damage to equipment. Separation through membranes is performed at elevated pressures, ranging from 6–20 bar in some plants and 15–40 bar in others, depending on design and manufacturer. The result is a methane-rich stream and a CO2-rich stream containing traces of CH4 and H2S. To reduce methane slip, part of this off-gas is recirculated. However, single-stage designs only deliver biomethane of 92–96% purity, with relatively low recovery. For this reason, commercial plants frequently employ multi-stage systems, which make it possible to reach 98% methane content.

Figure 6.

Schematic of a single-stage membrane biogas purification process.

Figure 6.

Schematic of a single-stage membrane biogas purification process.

In recent years, membrane contactors have emerged as a promising gas/liquid membrane technology with growing application in biogas upgrading [29]. These systems integrate the phase-selective behavior of membranes with absorption processes, combining the advantages of both approaches. Their main strengths are higher efficiency, reduced energy demand, and improved cost-effectiveness compared to conventional units. Operating at lower pressures (3–6 bar), membrane contactors are able to selectively remove CO2 and H2S while producing high-quality biomethane. This innovative approach reflects the progress of sustainable technologies in energy systems and highlights the growing relevance of advanced designs in addressing both environmental and economic challenges.

Figure 7.

Membrane contactor system for biogas upgrading (Spain).

Figure 7.

Membrane contactor system for biogas upgrading (Spain).

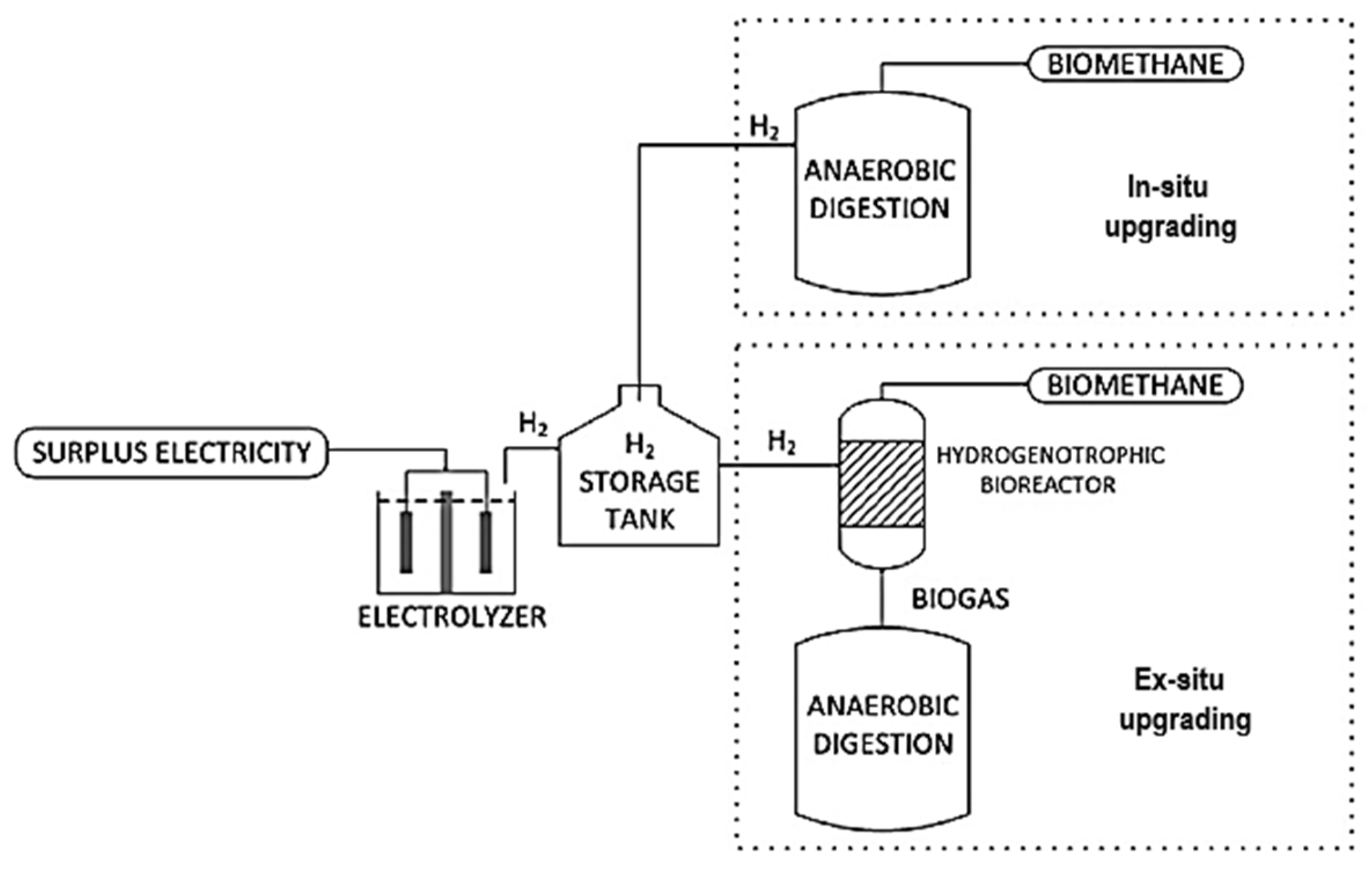

A different line of technological development is biological methanation, which uses microorganisms to catalyze the conversion of carbon dioxide and hydrogen into methane. Known as Power-to-Methane, the concept involves using renewable electricity to produce hydrogen, which is then combined with CO2, often derived from fermentation gases, to form biomethane [30]. This microbial conversion is carried out by autotrophic microorganisms that use CO2 as a carbon source and H2 as an electron donor. The pathway may be direct, with hydrogenotrophic methanogens converting CO2 into CH4, or indirect, with homoacetogenic bacteria first producing acetate that is subsequently transformed into CH4. Compared to catalytic-chemical methanation, which requires severe conditions (300–500 °C and high pressures), the biological route is feasible at moderate temperatures, since methanogens are active between 0 and 122 °C, with optimal ranges of 15–98 °C. This biological flexibility allows tolerance to impurities in the gas stream, although lower operating temperatures mean lower kinetics and mass transfer coefficients [31].

Two main strategies exist: in situ and ex situ. In situ approaches add hydrogen and substrates directly into the digester, where CH4 is formed from the reaction of CO2 and H2 (Figure 8). The key advantage is that the same fermentation digester produces and upgrades biogas, reducing costs. Yet, operational issues arise, such as increased pH above 8.5 that can inhibit methanogenesis, or the accumulation of volatile fatty acids (VFAs) when excess H2 hinders their oxidation. Continuous adjustment of hydrogen flow based on CO2 content is therefore critical and requires precise control and monitoring [32]. Ex situ systems (Figure 8) instead use an external reactor fed with CO2-rich gas—either from digesters or other sources—mixed with hydrogen at a stoichiometric ratio of 4:1 (H2:CO2). The reactor is inoculated with hydrogenotrophic archaea and supplemented with nutrients, enabling stable biomethane production without interfering with the digestion process. Ex situ configurations can achieve higher efficiency and valorization compared to in situ designs [33]. Hybrid systems, which combine both modes, have also been proposed: for example, using a smaller external reactor to complement an in situ digester, thus avoiding excessive pH increases while improving overall yields [34].

Figure 8.

In situ and ex situ biological methanation schemes. Adapted from [30].

Figure 8.

In situ and ex situ biological methanation schemes. Adapted from [30].

Hybrid technologies combining multiple upgrading processes are also being investigated [35]. These integrated systems exploit the advantages of different methods to maximize performance and reduce costs. Configurations may combine membrane separation, water scrubbing, PSA, cryogenic upgrading, or other techniques, creating synergies not possible with a single process. Studies on hybrid membrane systems [36] show that pairing membranes with water scrubbing involves higher capital costs than stand-alone scrubbing, but hybrid cryogenic-membrane approaches offer clear benefits, improving both costs and efficiency compared to simple cryogenics. Energy efficiency is another decisive factor: simulation studies [37] demonstrated that hybrid cryogenic-chemical systems achieved 12–15% higher energy performance than conventional MEA absorption. In comparative analyses, a cryogenic+membrane system outperformed a three-stage membrane design under optimal conditions, consuming less energy and offering better CO2 removal [38]. These results highlight the significant potential of hybrid approaches to provide more efficient and economically viable biomethane upgrading routes.

Finally, the infrastructure for biomethane distribution and storage is progressively adopting sustainable materials [39]. Pipelines, storage tanks, and distribution facilities increasingly incorporate recyclable and low-carbon materials, meeting technical requirements while supporting environmental objectives. The use of these materials is seen as essential for ensuring the long-term sustainability of biomethane projects.

4. Policy and Regulatory Drivers of Biomethane Development

In 2022, after the pandemic had already weakened the economy, the war in Ukraine together with the energy crisis, the visible effects of climate change, and an inflationary environment created new, complex and disruptive challenges for companies and for society. As a response, many governments accelerated the energy transition with agile and practical measures. Since the energy market turmoil began, countries—each to a different extent—have tried to facilitate the transition by promoting energy efficiency and by lowering dependence on natural gas. In the European Union, the RePowerEU plan [40] became a central driver for expanding renewable energy and for speeding up the decarbonization of the European economy. Efforts to integrate renewable gases into the gas market have also advanced through legislative initiatives such as the EU Gas Package. At the same time, national carbon-neutrality targets imply a deep transformation of the energy sector, because they require very large investments in electrification and because not all final energy uses can be electrified.

The policy setting for biomethane has direct consequences for the growth and long-term sustainability of this sector. Public authorities shape the pathway of biomethane adoption, and their decisions affect multiple parts of the value chain. A first key area is the creation of stable, supportive regulatory frameworks. Clear, favorable rules provide certainty to producers and attract investment and innovation. Germany and Sweden are often cited as frontrunners, with feed-in tariffs and guaranteed grid access that have built a positive environment for biomethane producers [41]. Financial instruments are another pillar. Governments can stimulate projects using subsidies, tax credits, or other benefits. In the United States, the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) assigns Renewable Identification Numbers (RINs) to eligible volumes of biomethane, creating an economic signal for production and use [42]. In the United Kingdom, the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) has offered support to renewable heat technologies, including biomethane, helping scale deployment [43].

Infrastructure policy is also critical. A pragmatic route for the transition is to use the existing gas network as a decarbonization vector. The current grid already enables fuel switching away from more polluting fossil options, and its future value will grow with renewable gases and with digitalization. On the one hand, the network can accept biomethane injection—linked to circular-economy goals—can blend green hydrogen, and can transport other renewable gases such as synthetic methane produced from captured CO2. On the other hand, innovation in metering and operation (for example, smart meters) will improve energy efficiency in households, services, and industry. Decision makers can ease biomethane integration by planning injection points in strategic locations. Denmark’s comprehensive policy package includes dedicated measures to expand biogas infrastructure and ensure efficient distribution and use of biomethane [44]. Robust safety and quality rules are essential to build confidence. Joint work between regulators and industry to define and enforce common specifications supports a reliable market. In the EU, instruments such as RED II set sustainability criteria and quality standards, helping to harmonize practice across Member States [45].

International cooperation is becoming increasingly important. Authorities can collaborate to set common specifications for biomethane quality, building a harmonized framework accepted across borders. Such convergence facilitates trade and creates a more connected and resilient global market [46]. Harmonized standards reduce regulatory discrepancies, so biomethane produced in one country can comply with requirements at destination, lowering barriers to exchange. A global framework also strengthens the credibility of biomethane as a sustainable option [47]: consistent specifications generate trust among consumers, investors and stakeholders, which attracts new capital and supports innovation. Through cooperation, policymakers can address differences in regulation, technology and market structure, and increase resilience to shocks such as geopolitical tensions or price swings. In addition, an interconnected market enables countries to optimize resources and share expertise. Regions with abundant biomethane—often produced from anaerobic fermentation feedstocks—can help supply those with lower availability, improving energy security and sustainability. These exchanges can create mutually beneficial relations and reinforce the market’s integration [44].

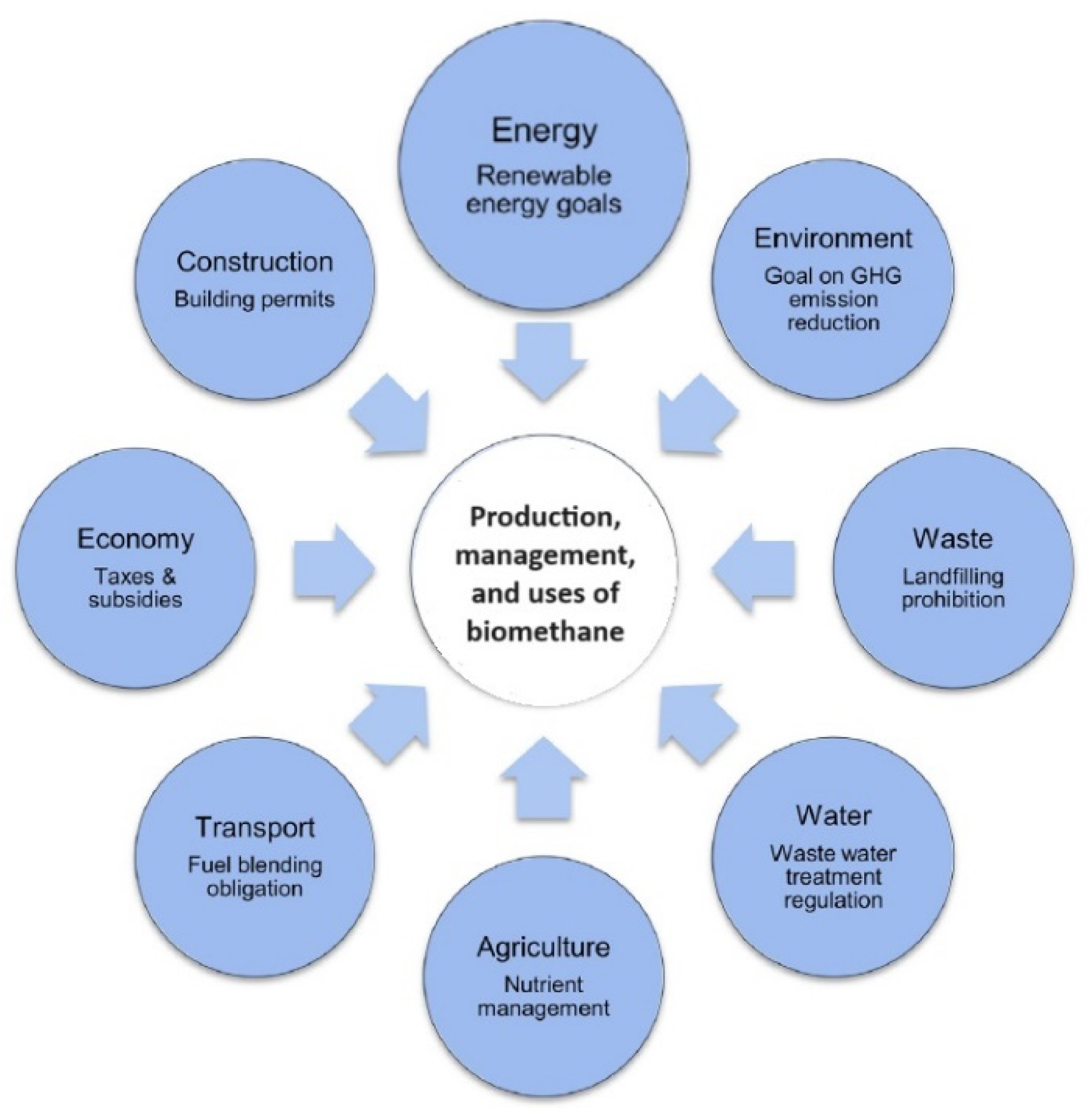

Because biomethane covers production, management and end-use, policies from many ministries can influence outcomes: environment, energy, water, waste, transport, agriculture, construction and economy (Figure 9). This cross-cutting nature frequently spreads responsibilities across different administrations, sometimes with direct control and sometimes with indirect effects. As a result, the choice and design of policy instruments for this renewable gas can vary widely. Where biomethane systems are seen mainly as renewable energy production, the core policies sit in the energy domain. Where the focus is on nutrient recycling and biofertilizer supply, agricultural policies gain weight. Environmental, waste and wastewater policies can act as catalysts by promoting anaerobic digestion (a fermentation process) for organic waste treatment and greenhouse-gas mitigation, thus supporting biogas growth. Environmental rules may have a dual effect: measures to reduce emissions stimulate biogas use, while strict rules on digestate spreading can limit the feasibility of producing biogas and biofertilizers in certain regions. Transport and infrastructure policies—such as blending mandates or CO2 standards for vehicles—affect the use of biomethane as vehicle fuel. This application has been dominant in Sweden for many years and is increasingly relevant in other Nordic countries, as well as in Germany and Italy, and in California in the United States. Finally, construction and economic policies matter for siting and operating plants: new facilities usually require specific permits, and project success often depends on investment support and on operational aid to remain competitive with fossil energy [48].

Figure 9.

Cross-sector policy domains shaping biomethane production, upgrading and use.

Figure 9.

Cross-sector policy domains shaping biomethane production, upgrading and use.

5. Biomethane and Other Ecofuels in the Future International Energy Landscape

The global resolve to tackle climate change has opened space for new energy solutions, in which biomethane and other ecofuels are emerging as central options for a decarbonized future [49]. Biomethane is often the first substitute for conventional natural gas because it can be injected into existing gas networks with minimal changes. Produced from organic wastes via anaerobic fermentation (agricultural residues, municipal solid waste, sludges), it couples waste management with clean energy production. At the international level, the European Union has led deployment by setting ambitious transport targets under the Renewable Energy Directive II (RED II), where biomethane is a key lever to cut greenhouse gas emissions and raise the share of renewables in transport.

Beyond biomethane, other ecofuels—most notably synthetic fuels and advanced biofuels—are gaining relevance and help diversify the energy mix [50]. Synthetic fuels from Power-to-X routes use renewable electricity to convert captured CO2 into hydrogen or synthetic methane, offering options for sectors that are hard to electrify, including aviation, maritime transport, and heavy industry. Advanced biofuels from sustainable feedstocks and improved processing address land-use and food-competition concerns; second- and third-generation pathways enable more efficient use of biomass. The European framework—principally the Renewable Energy Directive and the Fuel Quality Directive—defines sustainability criteria to ensure high environmental and social performance of these fuels [51].

There is now broad recognition of the strategic role of ecofuels in climate strategies [52]. Initiatives such as FuelEU Maritime and ReFuelEU Aviation set concrete targets to reduce emissions in shipping and aviation, creating demand and a supportive regulatory context. Financial signals reinforce this agenda: the Next Generation EU facility in Europe and the Inflation Reduction Act in the United States channel substantial resources into clean fuels, supporting R&D, demonstration, and early deployment and pushing the sector toward commercial maturity.

Nevertheless, significant barriers still limit large-scale adoption of biomethane and other ecofuels [53]. Infrastructure needs, technological improvements, and the secure supply of sustainable feedstocks require coordinated public–private action. The institutional and financial landscape for biomethane is complex, with risks that can slow down implementation [54]. Although biomethane delivers multiple co-benefits, its cross-sector nature complicates policy design and coordination. In many jurisdictions, responsibilities are dispersed across agencies, and sometimes measures in different domains work at cross-purposes. Moreover, despite the maturity of anaerobic digestion with upgrading, biogas pathways often remain peripheral in policy debates and deployment is still limited in many countries. Prior to the EU Green Deal (2020), biogas potential was scarcely considered in EU policy, and evidence indicates that current biogas output—nationally and globally—lies far below the achievable potential from organic wastes and residues [55,56].

Geopolitics reshaped the debate in early 2022. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the use of natural gas supply as leverage in the EU shifted attention toward energy and food security [57]. The European Commission called for rapid acceleration, placing special emphasis on domestic biomethane to reduce import dependence and setting an EU-wide target of 35 bcm of biomethane by 2030—roughly double the current combined biogas and biomethane output in Member States. If achieved, this would illustrate how policies can pivot toward resilience to crises while still supporting decarbonization.

Within this strategy, the Commission identified slow and complex permitting as a major bottleneck. In many countries, authorizations for energy projects are lengthy and discourage investors, which can push decisions toward less sustainable waste and energy options. Streamlining the path from application to approval would lower entry barriers for new biomethane plants. Continued investment in R&D can further improve the efficiency and costs of ecofuel production. International cooperation—sharing knowledge and technology—can speed the emergence of a global ecofuel market. Ecofuels also offer opportunities for regional development, jobs, and new value chains, aligning climate action with broader socioeconomic goals. As nations seek to mitigate climate impacts, biomethane and other ecofuels provide versatile solutions spanning multiple sectors and bridging the gap for hard-to-electrify uses. The evolving international setting—built on regulation, finance, and collaboration—creates favorable conditions for wider adoption.

In summary, biomethane and other ecofuels are well positioned to contribute to a sustainable, low-carbon future. Realizing these potential calls for a coherent global effort that combines technological innovation, stable and supportive regulation, and adequate financing. With sustained commitment and coordination, these fuels can play a transformative role in the international energy landscape, strengthening both decarbonization and system resilience.

6. Future Scenarios and Forecasts

Exploring the future pathway of biomethane points to multiple plausible directions shaped by fast-moving trends and new innovations. Expected developments include steady gains in process performance (from anaerobic fermentation/anaerobic digestion to upgrading), diversification of feedstock portfolios, and wider use of decentralized, community-oriented plants. Stronger coupling with other renewables and fit-for-purpose policies will be decisive, with hybrid systems and coherent regulatory frameworks that de-risk investment and enable smooth integration of biomethane into existing energy networks. Prospects also include expansion of international markets supported by closer cooperation and harmonized standards, creating economic opportunities while improving system resilience. Environmental impact assessment, stakeholder participation, and higher public awareness are essential elements of this vision, keeping biomethane aligned with sustainability objectives and continuous reduction of carbon footprint. At the same time, it is important to recognize the complexity ahead. Constraints related to seasonal and regional feedstock availability, volatile market conditions, and shifting regulation will require robust risk management, adaptive planning, and flexible business models. In short, the sector’s forward journey is a collaborative task in which technological progress, policy alignment, and local engagement come together to build a sustainable and resilient energy option. The outlook goes beyond energy output alone and embraces a holistic perspective that links responsible resource use, community well-being, and international interconnection, opening the way toward a greener and more sustainable future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.H. and J.M.M.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.H.; writing—review and editing, J.M.M.-M., M.A.S.-G, E.P.-Z., R.T.; funding acquisition, D.H. and J.M.M.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge support of this work by the Spanish Ministry of Industry and Tourism under the PERTE for Industrial Decarbonization, reference DI1-010000-2024-38 (CAPCO2BIO project) and by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 and Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Programmes under grant agreement No 63249400 (CRONUS project).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Koloski-Ostrow, A.O. The Archaeology of Sanitation in Roman Italy: Toilets, Sewers, and Water Systems; Publisher: UNC Press Books, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- An, P.G. Constructing and Dismantling Frameworks of Disease Etiology: The Rise and Fall of Sewer Gas in America, 1870–1910. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2004, 77(3–4), 75.

- Crook, T. Danger in the Drains: Sewer Gas, Sewerage Systems and the Home, 1850–1900. In Governing Risks in Modern Britain: Danger, Safety and Accidents, c. 1800–2000; 2016; pp. 105–126.

- Ferrie, J.E. Remnants of Sewer Gas. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 42(6), 1589–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, R.J. Improving in Purifying Illuminating-Gas and Utilizing Wastes Therefrom. U.S. Patent 4998, 23 July 1872. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/USRE4998E/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Carter Ramsden, J. Improvement in Boiler-Furnaces. U.S. Patent 158,310, 1874. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US158310A/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Fagerström, A.; Murphy, J.D. (Eds.) Country Reports Summary 2017, Task 37; Publisher: IEA Bioenergy, 2018; ISBN 978-1-910154-50-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wellinger, A.; Murphy, J.D.; Baxter, D. (Eds.) The Biogas Handbook: Science, Production and Applications; Publisher: Elsevier, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Raven, R.P.J.M.; Geels, F.W. Socio-Cognitive Evolution in Niche Development: Comparative Analysis of Biogas Development in Denmark and the Netherlands (1973–2004). Technovation 2010, 30(2), 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babonneau, F.; Haurie, A.; Vielle, M. Reaching Paris Agreement Goal through Carbon Dioxide Removal Development: A Compact OR Model. Oper. Res. Lett. 2023, 51(1), 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Islas, D.; Pérez-Romero, M.E.; García, J.Á.; Ventura-Cruz, I. Trend in Publications Related to Biomethane Using a Bibliometric Approach. Int. J. Des. Nat. Ecodyn. 2023, 18(3), 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GRS. Biomethane and Biogas Market—Global Outlook and Forecast 2023–2030; Publisher: Grand Research Store, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Markets and Markets. Biomethane Market Global Forecast to 2030. Available online: https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/biomethane-market-190903532.html (accessed on 29 February 2024).

- Trinity SMF. Outlook on the Summary Biomethane Market. Available online: https://trinitysmf.com/macro-reports/ (accessed on 29 February 2024).

- Karne, H.; Mahajan, U.; Ketkar, U.; Kohade, A.; Khadilkar, P.; Mishra, A. A Review on Biogas Upgradation Systems. Mater. Today: Proc. 2023, 72, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, R.; Ghosh, P.; Kumar, M.; Vijay, V.K. Evaluation of Biogas Upgrading Technologies and Future Perspectives: A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 11631–11661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignogna, D.; Ceci, P.; Cafaro, C.; Corazzi, G.; Avino, P. Production of Biogas and Biomethane as Renewable Energy Sources: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13(18), 10219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayeem, A.; Shariffuddin, J.H.; Yousuf, A. Absorption Technology for Upgrading Biogas to Biomethane. In Biogas to Biomethane. In Biogas to Biomethane; Publisher: Woodhead Publishing, 2024; pp. 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Mergenthal, M.; Tawai, A.; Amornraksa, S.; Roddecha, S.; Chuetor, S. Methane Enrichment for Biogas Purification Using Pressure Swing Adsorption Techniques. Mater. Today: Proc. 2023, 72, 2915–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd, A.A.; Othman, M.R.; Majdi, H.S.; Helwani, Z. Green Route for Biomethane and Hydrogen Production via Integration of Biogas Upgrading Using Pressure Swing Adsorption and Steam-Methane Reforming Process. Renew. Energy 2023, 210, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piechota, G.; Generowicz, N.; Abd, A.A.; Othman, M.R.; Kowalczyk-Juśko, A.; Kumar, G.; Veeremuthu, A. An Introduction to Biogas and Biomethane. In Biogas to Biomethane; Publisher: Woodhead Publishing, 2024; pp. 3–40. [Google Scholar]

- Vakylabad, A.B. Absorption Processes for CO2 Removal from CO2-Rich Natural Gas. In Advances in Natural Gas: Formation, Processing, and Applications. Volume 2: Natural Gas Sweetening; Publisher: Elsevier, 2024; pp. 207–257. [Google Scholar]

- Angelidaki, I.; Treu, L.; Tsapekos, P.; Luo, G.; Campanaro, S.; Wenzel, H.; Kougias, P.G. Biogas Upgrading and Utilization: Current Status and Perspectives. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36(2), 452–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena-Moreno, F.M.; Rodríguez-Galán, M.; Vega, F.; Vilches, L.F.; Navarrete, B.; Zhang, Z. Biogas Upgrading by Cryogenic Techniques. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 1251–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkotsis, P.; Kougias, P.; Mitrakas, M.; Zouboulis, A. Biogas Upgrading Technologies—Recent Advances in Membrane-Based Processes. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48(10), 3965–3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, D.G.; Čiliak, D.; Langerak, J.; Bakker, B.; Pescarmona, P.P. Binderless SAPO-34 Beads for Selective CO2 Adsorption. Sustain. Chem. Clim. Action 2023, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, M.; Melin, T.; Wessling, M. Transforming Biogas into Biomethane Using Membrane Technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 17, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczak, W.; Gryta, M.; Daniluk, M.; Żak, S. Biogas Upgrading Using a Single-Membrane System: A Review. Membranes 2024, 14(4), 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, D.; Sanz-Bedate, S.; Martín-Marroquín, J.M.; Castro, J.; Antolín, G. Selective Separation of CH4 and CO2 Using Membrane Contactors. Renew. Energy 2020, 150, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, D.; Martín-Marroquín, J.M. Power-to-Methane, Coupling CO2 Capture with Fuel Production: An Overview. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 132, 110057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Lou, H.; Xu, N.; Zeng, F.; Pei, G.; Wang, Z. Methanation of CO/CO2 for Power-to-Methane Process: Fundamentals, Status, and Perspectives. J. Energy Chem. 2023, 80, 182–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, E.P.; Deane, P.; Persson, T.; Ó Gallachóir, B.; Murphy, J.D. A Perspective on the Potential Role of Renewable Gas in a Smart Energy Island System. Renew. Energy 2015, 78, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, R.; Ghosh, P.; Kumar, M.; Vijay, V.K. Evaluation of Biogas Upgrading Technologies and Future Perspectives: A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 11631–11661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhou, P.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, D. The Role of Endogenous and Exogenous Hydrogen in the Microbiology of Biogas Production Systems. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 36, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyay, A.; Kovalev, A.A.; Zhuravleva, E.A.; Kovalev, D.A.; Litti, Y.V.; Masakapalli, S.K.; Vivekanand, V.; et al. Recent Development in Physical, Chemical, Biological and Hybrid Biogas Upgradation Techniques. Sustainability 2022, 15(1), 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, M.; Melin, T.; Wessling, M. Transforming Biogas into Biomethane Using Membrane Technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 17, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaissaoui, B.; Le Moullec, Y.; Willson, D.; Favre, E. Hybrid Membrane–Cryogenic Process for Post-Combustion CO2 Capture. J. Membr. Sci. 2012, 415, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Liu, Q.; Ji, N.; Deng, S.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Kitamura, Y. Reducing the Energy Consumption of Membrane–Cryogenic Hybrid CO2 Capture by Process Optimization. Energy 2017, 124, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, D.; Esposito, B.; Supino, S.; Malandrino, O.; Sessa, M.R. Biogas-Based Systems: An Opportunity Towards a Post-Fossil and Circular Economy Perspective in Italy. Energy Policy 2023, 182, 113719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, V. Clean, Diversified, and Affordable Energy for the European Union in the Context of the REPowerEU Plan. Amfiteatru Econ. J. 2023, 25(64), 654–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulewski, P.; Ignaciuk, W.; Szymańska, M.; Wąs, A. Development of the Biomethane Market in Europe. Energies 2023, 16(4), 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, L.; Wright, P. California Low Carbon Fuel Standard Carbon Intensity Applied to New York State Dairy Manure Anaerobic Digestion to Renewable Natural Gas. Available online: https://ecommons.cornell.edu/ (accessed on 9 March 2024).

- Calvillo, C.F.; Katris, A.; Alabi, O.; Stewart, J.; Zhou, L.; Turner, K. Technology Pathways, Efficiency Gains and Price Implications of Decarbonising Residential Heat in the UK. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2023, 48, 101113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, M. Policy Designs for Biomethane Promotion. In Biogas to Biomethane; Publisher: Woodhead Publishing, 2024; pp. 301–320. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, N.; Moosmann, D.; Majer, S.; Meisel, K.; Oehmichen, K.; Rauh, S.; Thrän, D. Assessment of Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction from Biogas Supply Chains in Germany in Context of a Newly Implemented Sustainability Certification. In Progress in Life Cycle Assessment 2021; Publisher: Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Babikian, J. Beyond Borders: International Law and Global Governance in the Digital Age. Law Res. J. 2024, 2(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- D’Adamo, I.; Ribichini, M.; Tsagarakis, K.P. Biomethane as an Energy Resource for Achieving Sustainable Production: Economic Assessments and Policy Implications. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 35, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, M.; Anderberg, S. Dimensions and Characteristics of Biogas Policies—Modelling the European Policy Landscape. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Nghiem, X.H.; Jabeen, F.; Luqman, A.; Song, M. Integrated Development of Digital and Energy Industries: Paving the Way for Carbon Emission Reduction. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 187, 122236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, H.; Crawford, C. CO2-Based Alternative Fuel Production to Support Development of CO2 Capture, Utilization and Storage. Fuel 2023, 331, 125684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekanozishvili, M. Consolidation of EU Renewable Energy Policy: Renewable Energy Directive (RED). In Dynamics of EU Renewable Energy Policy Integration; Publisher: Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 101–153. [Google Scholar]

- Mondal, S.; Kumar, A.; Pachauri, R.K.; Mondal, A.K.; Singh, V.K.; Sharma, A.K. (Eds.) Clean and Renewable Energy Production; Publisher: John Wiley & Sons, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, P.J. Review of Sustainable Energy Carriers for Aviation: Benefits, Challenges, and Future Viability. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2023, 141, 100919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isah, A.; Dioha, M.O.; Debnath, R.; Abraham-Dukuma, M.C.; Butu, H.M. Financing Renewable Energy: Policy Insights from Brazil and Nigeria. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2023, 13(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberici, S.; Grimme, W.; Toop, G. Biomethane Production Potentials in the EU. Feasibility of REPowerEU 2030 Targets, Production Potentials in the Member States and Outlook to 2050; Publisher: Guidehouse Netherlands BV: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, M.; Ammenberg, J.; Murphy, J.D. IEA Bioenergy Task 37—A Perspective on the State of the Biogas Industry from Selected Member Countries; Publisher: IEA Bioenergy: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions—Youth Opportunities Initiative; Publisher: European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Suhartini, S.; Nugroho, W.A.; Putranto, A.W.; Pangestuti, M.B.; Rohma, N.A.; Melville, L. Life Cycle Assessment of Biomethane Technology. In Biogas to Biomethane; Publisher: Woodhead Publishing, 2024; pp. 243–275. [Google Scholar]

- Abomohra, A.E.F.; Elsayed, M.; Qin, Z.; Ji, H.; Liu, Z., Eds. Biogas: Recent Advances and Integrated Approaches; 2021.

- González, R.; García-Cascallana, J.; Gómez, X. Energetic Valorization of Biogas: A Comparison Between Centralized and Decentralized Approach. Renew. Energy 2023, 215, 119013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieborg, M.U.; Oliveira, J.M.S.; Ottosen, L.D.M.; Kofoed, M.V.W. Flue-to-Fuel: Bio-Integrated Carbon Capture and Utilization of Dilute Carbon Dioxide Gas Streams to Renewable Methane. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 302, 118090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanni, D.; Minutillo, M.; Cigolotti, V.; Perna, A. Biomethane Production Through the Power-to-Gas Concept: A Strategy for Increasing the Renewable Sources Exploitation and Promoting the Green Energy Transition. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 293, 117538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fund, T.S.M. Biomethane Market; January 2024.

- Yamaji, D.M.; Amâncio-Vieira, S.F.; Fidelis, R.; Contani, E.A.D.R. Proposal of Multicriteria Decision-Making Models for Biogas Production. Energies 2024, 17(4), 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyombo, O.T.; Mhlongo, N.Z.; Nwankwo, E.E.; Scholastica, U.C. Bioenergy and Sustainable Agriculture: A Review of Synergies and Potential Conflicts. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2024, 11, 2082–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).