Submitted:

17 December 2025

Posted:

18 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Strong evidence shows MDMA-AT can produce large, lasting reductions in PTSD symptoms.

- Blinding remains problematic because MDMA’s psychoactive effects are obvious to participants.

- TAML model explains how trauma memories are stored, reactivated, and reinforced in brain circuits.

- MDMA creates a “therapeutic window” by lowering fear signals and enhancing emotional regulation.

- Different trauma types respond differently: acute trauma may resolve quickly, while complex trauma needs extended care.

- Introduction of BMPP, a new clinical trial design uses role-based masking to reduce bias while supporting effective therapy.

2. A Functional Model of Dysregulated Memory Recall in Trauma

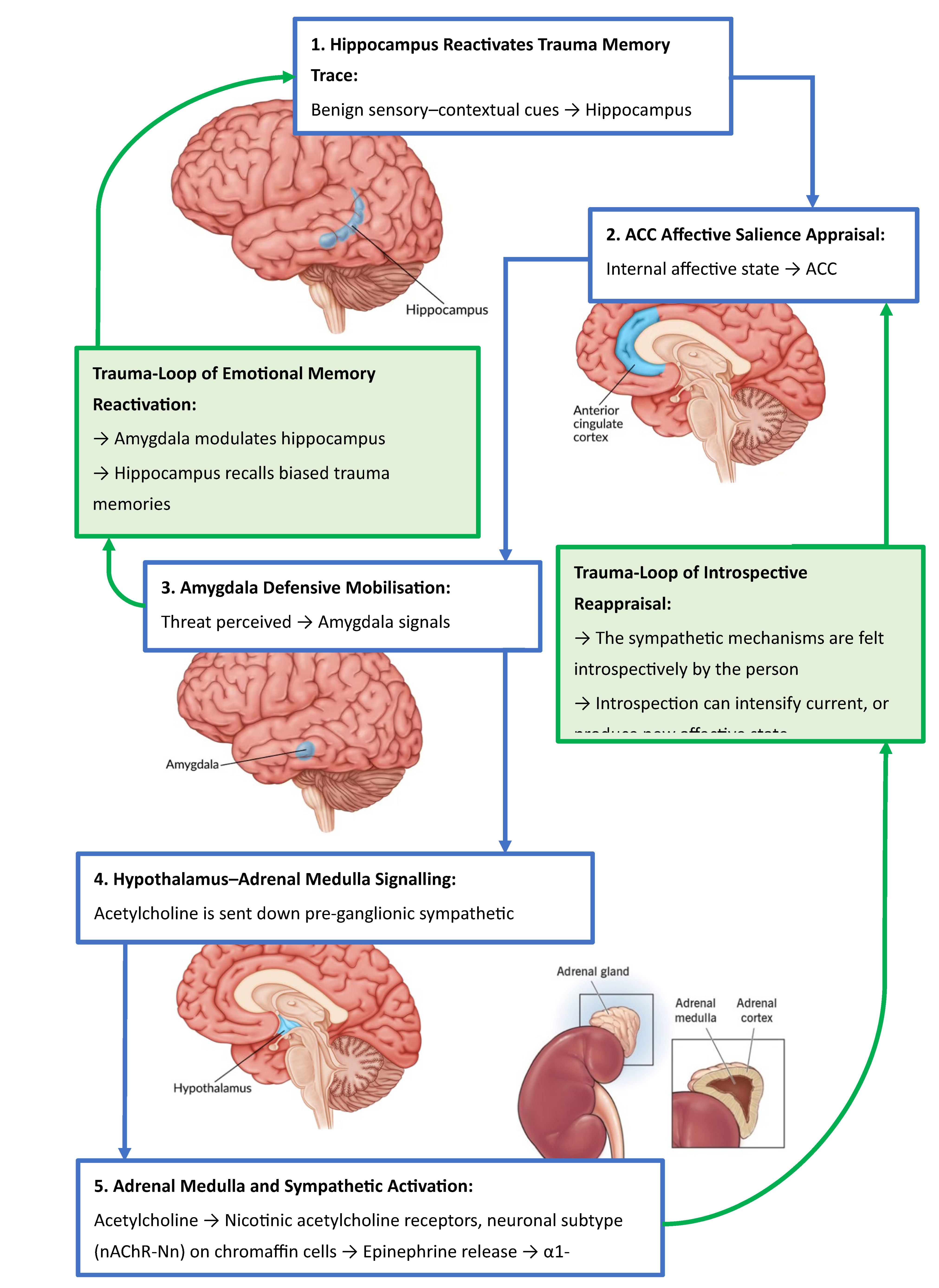

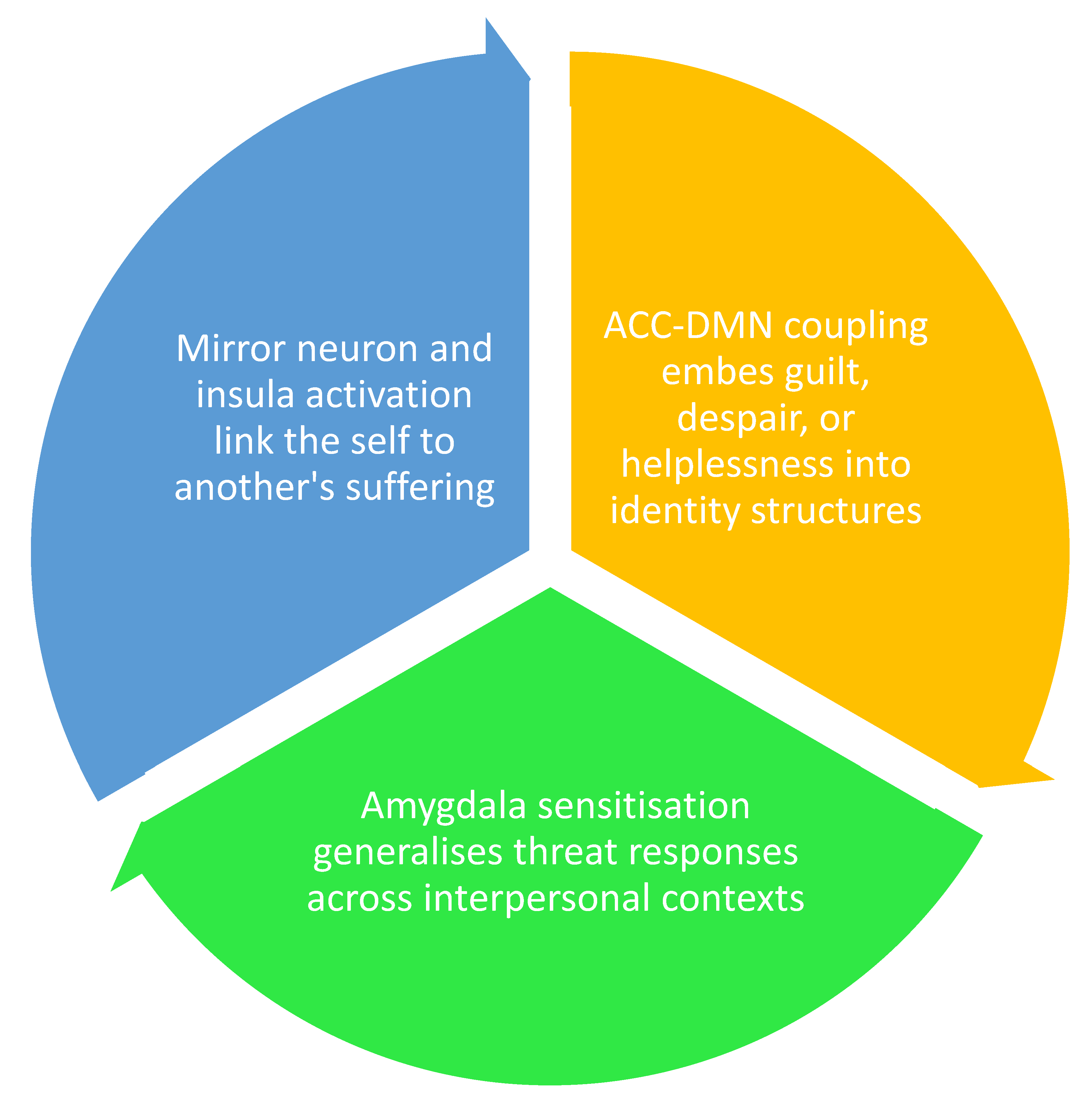

2.1. Mapping the Trauma-Affective Memory Loop

2.2. From Context to Crisis: Memory Retrieval and Affective Appraisal

2.3. Trauma as an Adaptive Response of the Amygdala

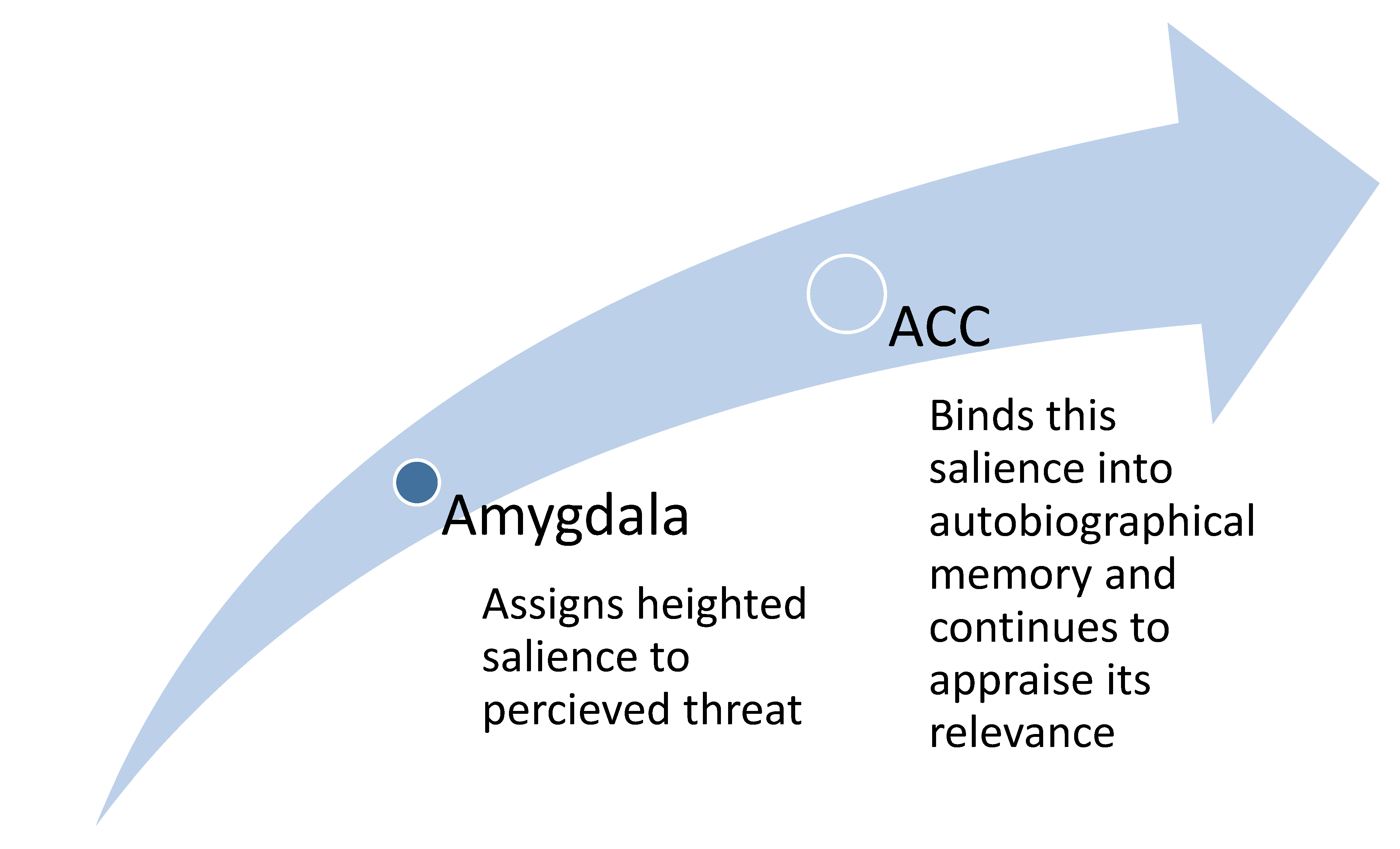

2.4. The Role of the ACC in Triggering the Adaptive Response of the Amygdala

2.5. Affective Fusion: When Emotion Becomes Identity

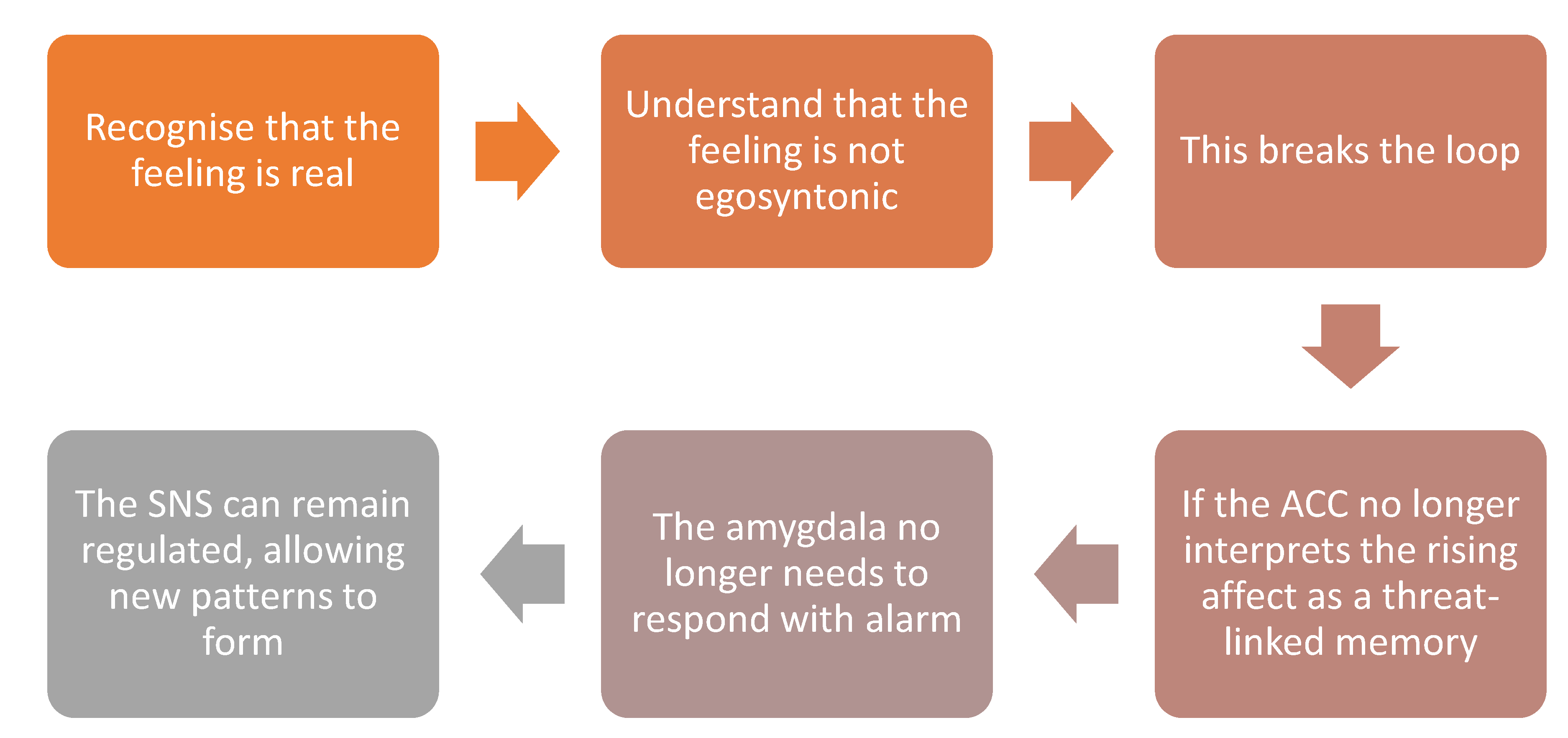

2.6. Dis-identification and the Deconstruction of Affective Imprints

3. Neuropsychopharmacology of MDMA

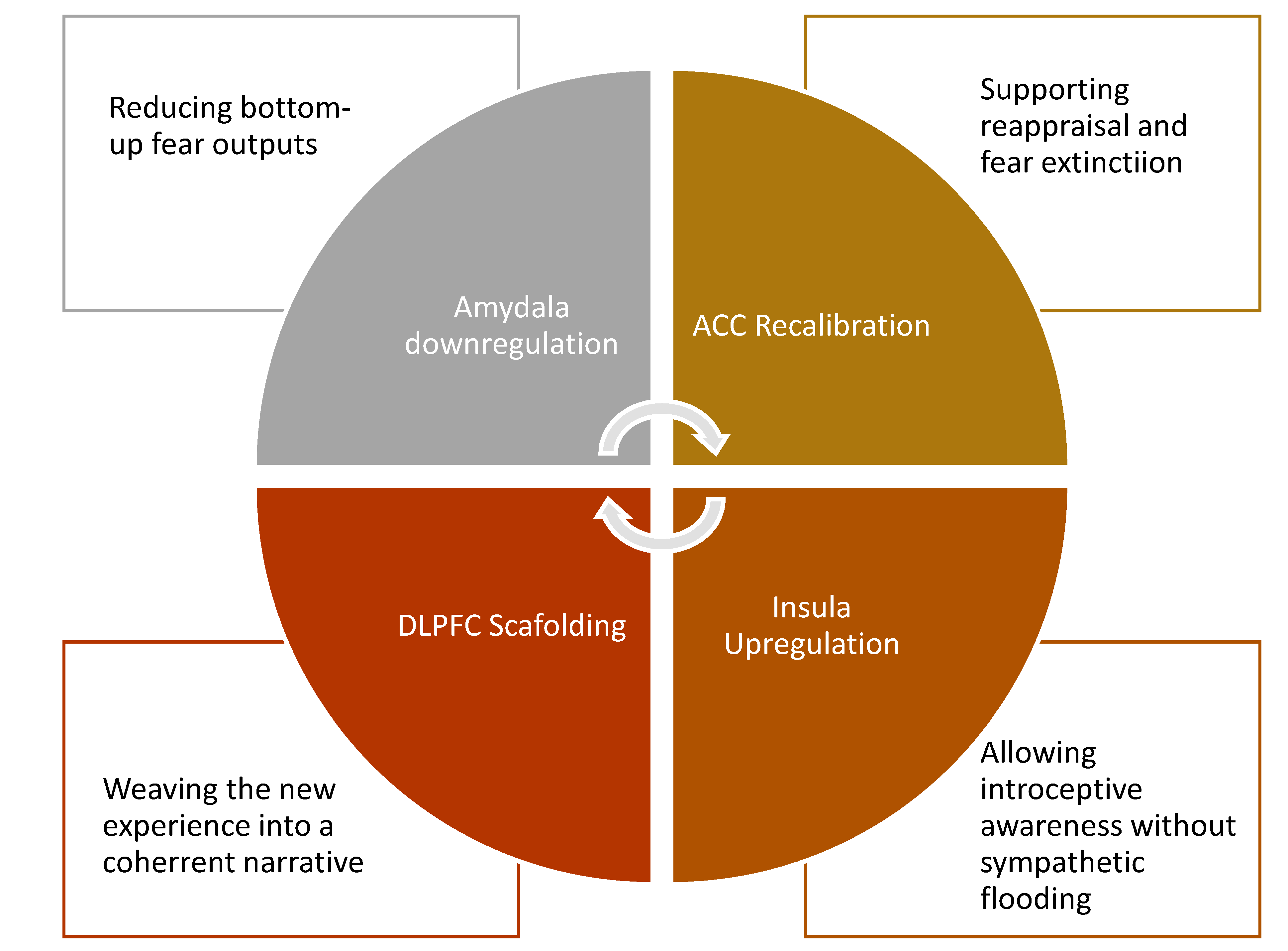

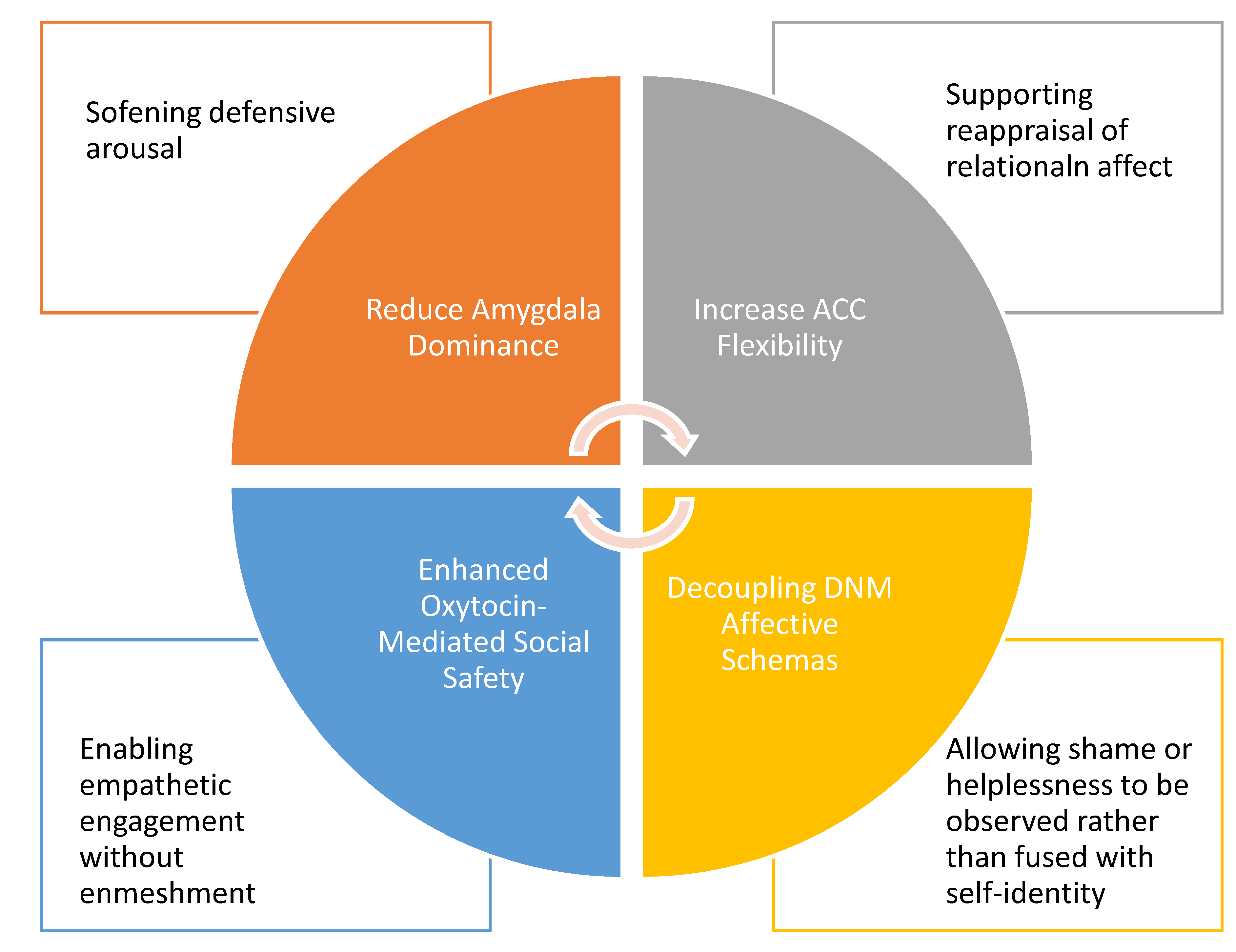

3.1. Affective Circuitry Modulation in MDMA-Assisted Therapy

3.2. Corticolimbic Decoupling and Salience Recalibration

- Decreasing amygdala hyperactivity: MDMA directly dampens the amygdala’s excitability and weakens its bottom-up output to the hypothalamus [64], reducing the body’s automatic fear-driven reactions.

- Enhancing fear extinction: By modulating amygdala–ACC FC, MDMA raises the threshold for the ACC to classify a stimulus as threatening [35,65,66]. This recalibration allows traumatic memories to be revisited without triggering the defensive sympathetic cascade, creating the conditions for extinction learning.

3.3. The Therapeutic Window: Self-Referential Network Remapping and Affective Decoupling

- This is the therapeutic window: a brain state where emotional and affective states can be observed rather than fused with, enabling metacognitive awareness. Within this altered context, traumatic memories can be re-encountered without defensive mobilisation. Instead, they are re-encoded against a backdrop of coherence, empathy, and agency. Over repeated exposures, the traumatic imprint shifts from a danger-laden signal to a survivorship narrative, supporting integration.

3.4. Role of the Prefrontal Cortex in Supporting Integration

4. The Brinzei MDMA-PTSD Protocol

4.1. Formulating the Hypothesis

4.2. Differentiating Trauma Exposure: Neurobiological Implications for MDMA-Assisted Therapy

4.2.1. Neurophenomenological Stratification of Trauma Exposure

4.2.2. Direct Exposure and Affective Traceability

4.2.3. Indirect Exposure and Affective Enmeshment

4.2.4. Clinical Implications

| Trauma Type | PTSD Phenotype | Nature of Exposure | Affective Encoding Profile | MDMA Therapeutic Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute direct trauma | Classic PTSD | First-hand, time-bound | Amygdala–ACC circuit; discrete imprint | High; rapid decoupling and re-encoding |

| Chronic direct trauma | Complex PTSD | Sustained, developmental | Multi-network dysregulation (ACC, DMN) | Moderate; requires extended integration |

| Witnessed traumaa | Secondary PTSD | Vicarious, empathic | Partial co-activation, less personal | Moderate; depends on identity fusion |

| Witnessed traumab | Relational PTSD | Deeply personal, empathic | Affective enmeshment, insula/ACC load | Variable; depends on healing in the other |

| Repeated exposurec | Occupational PTSD | Chronic, cumulative | Layered micro-trauma, moral injury | Moderate; may require phased intervention |

5. Methodological Foundations of Masking Design

5.1. Clinical Rationale for Expectancy Control

5.2. Role-Based Masking Justification

| Role | Masked To | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | Phenotype classification; Therapeutic hypothesis |

Reduces expectancy effects and demand characteristics |

| Care Providers | Phenotype classification | Prevents bias in supportive care delivery |

| Outcome Assessors | Phenotype classification | Ensures objectivity in clinical outcome assessment |

| Therapists | Not blinded | Must know phenotype and rationale to deliver targeted psychotherapy |

| Investigators | Phenotype classification | Preserves analytic objectivity while maintaining scientific oversight |

5.3. Masking Integrity: Role Conflict Management

| Role | Excluded Function | Access Restrictions |

|---|---|---|

| Therapist | Cannot act as investigator, recruiter, care provider, or outcome assessor | Access to trauma phenotype and rationale; excluded from assessment and analysis |

| Recruiter | Cannot act as therapist, care provider, outcome assessor, or data-analysing | Blinded to phenotype where possible; firewalled if also acting in investigator role |

| Investigator | Cannot act as therapist, recruiter, care provider, or outcome assessor | Masked to phenotype; may access treatment data for monitoring; no direct participant contact |

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Slomski, A. MDMA-Assisted Therapy Highly Effective for PTSD. JAMA 2021, 326, 299–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, D; Yazar-Klosinski, B; Nosova, E; et al. MDMA-assisted therapy is associated with a reduction in chronic pain among people with post-traumatic stress disorder. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 939302. 20221103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, AV; Jardim, DV; Chaves, BR; et al. 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy for victims of sexual abuse with severe post-traumatic stress disorder: an open label pilot study in Brazil. Braz J Psychiatry 2021, 43, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, JM; Bogenschutz, M; Lilienstein, A; et al. MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Nat Med 2021, 27, 1025–1033. 20210510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, JM; Ot'alora, GM; van der Kolk, B; et al. MDMA-assisted therapy for moderate to severe PTSD: a randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Nat Med 2023, 29, 2473–2480. 20230914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mithoefer, MC; Wagner, MT; Mithoefer, AT; et al. The safety and efficacy of {+/-}3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted psychotherapy in subjects with chronic, treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder: the first randomized controlled pilot study. J Psychopharmacol 2011, 25, 439–452. 20100719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mithoefer, MC; Mithoefer, AT; Feduccia, AA; et al. 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans, firefighters, and police officers: a randomised, double-blind, dose-response, phase 2 clinical trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehen, P; Traber, R; Widmer, V; et al. A randomized, controlled pilot study of MDMA (+/- 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine)-assisted psychotherapy for treatment of resistant, chronic Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). J Psychopharmacol 2013, 27, 40–52. 20121031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ot'alora, GM; Grigsby, J; Poulter, B; et al. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted psychotherapy for treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized phase 2 controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol 2018, 32, 1295–1307. 20181029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, JB; Lin, J; Bedrosian, L; et al. Scaling Up: Multisite Open-Label Clinical Trials of MDMA-Assisted Therapy for Severe Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 2021, 00221678211023663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avanceña, ALV; Kahn, JG; Marseille, E. The Costs and Health Benefits of Expanded Access to MDMA-assisted Therapy for Chronic and Severe PTSD in the USA: A Modeling Study. Clinical Drug Investigation 2022, 42, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinzei, OV; Donley, CN; Dixon Ritchie, G. From prohibited to prescribed: The rescheduling of MDMA and psilocybin in Australia. Drug Science, Policy and Law 2023, 9, 20503245231198472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp Barnir, E; Rubinstein, Z; Abend, R; et al. Peri-traumatic consumption of classic psychedelics is associated with lower anxiety and post-traumatic responses 3 weeks after exposure. J Psychopharmacol 2025, 39, 1031–1036. 20250421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocanu, V; Mackay, L; Christie, D; et al. Safety considerations in the evolving legal landscape of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy 2022, 17, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehen, P; Gasser, P. Using a MDMA- and LSD-Group Therapy Model in Clinical Practice in Switzerland and Highlighting the Treatment of Trauma-Related Disorders. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 863552. 20220425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseman, L. A reflection on paradigmatic tensions within the FDA advisory committee for MDMA-assisted therapy. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2025, 39, 313–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doblin, R. A Clinical Plan for MDMA (Ecstasy) in the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): Partnering with the FDA. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 2002, 34, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzner, R; Litwin, G; Weil, G. The relation of expectation and mood to psilocybin reactions: a questionnaire study. Psychedelic Rev 1965, 5, 3–39. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, RR; Richards, WA; McCann, U; et al. Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006, 187, 268-283; discussion 284-292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, RR; Johnson, MW; Carducci, MA; et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol 2016, 30, 1181–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aday, JS; Heifets, BD; Pratscher, SD; et al. Great Expectations: recommendations for improving the methodological rigor of psychedelic clinical trials. Psychopharmacology 2022, 239, 1989–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M; Jelen, L; Rucker, J. Expectancy in placebo-controlled trials of psychedelics: if so, so what? Psychopharmacology 2022, 239, 3047–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovmand, OR; Poulsen, ED; Arnfred, S; et al. Risk of bias in randomized clinical trials on psychedelic medicine: A systematic review. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2023, 37, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doblin, RE; Christiansen, M; Jerome, L; et al. The Past and Future of Psychedelic Science: An Introduction to This Issue. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 2019, 51, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, ST; Sanacora, G. Issues in Clinical Trial Design—Lessons From the FDA’s Rejection of MDMA. JAMA Psychiatry 2025, 82, 545–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Drugs Administration (FDA). Psychedelic Drugs: Considerations for Clinical Investigations. 2023. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/psychedelic-drugs-considerations-clinical-investigations.

- Harris, E. FDA Proposes First Guidance for Researchers Studying Psychedelics. JAMA 2023, 330, 307–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenberg, EE. From Efficacy to Effectiveness: Evaluating Psychedelic Randomized Controlled Trials for Trustworthy Evidence-Based Policy and Practice. Pharmacology Research & Perspectives 2025, 13, e70097. [Google Scholar]

- Brinzei, OV. Trauma-Effective Memory Loop. 2025. Available online: https://psynergeticsciences.com.au/blogs/neuroscience/trauma-effective-memory-loop.

- Feduccia, AA; Mithoefer, MC. MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD: Are memory reconsolidation and fear extinction underlying mechanisms? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2018, 84, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, P; Krebs, T. How could MDMA (ecstasy) help anxiety disorders? A neurobiological rationale. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2009, 23, 389–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huestis, MA; Smith, WB; Leonowens, C; et al. MDMA pharmacokinetics: A population and physiologically based pharmacokinetics model-informed analysis. CPT: Pharmacometrics & Systems Pharmacology 2025, 14, 376–388. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, S; Nutt, D. MDMA-assisted therapy: challenges, clinical trials, and the future of MDMA in treating behavioral disorders. CNS spectrums 2025, 30, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, SP; Wang, JB; Mithoefer, M; et al. Altered brain activity and functional connectivity after MDMA-assisted therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 947622. 20230112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walpola, IC; Nest, T; Roseman, L; et al. Altered Insula Connectivity under MDMA. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 2152–2162. 20170214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinzei, OV. The Brinzei MDMA-PTSD Protocol. 2025. Available online: https://psynergeticsciences.com.au/blogs/neuroscience/brinzei-mdma-ptsd-protocol.

- Morris, KR; Jaeb, M; Dunsmoor, JE; et al. Decoding threat neurocircuitry representations during traumatic memory recall in PTSD. Neuropsychopharmacology 2025, 50, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddox, SA; Hartmann, J; Ross, RA; et al. Deconstructing the Gestalt: Mechanisms of Fear, Threat, and Trauma Memory Encoding. Neuron 2019, 102, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiamulera, C; Hinnenthal, I; Auber, A; et al. Reconsolidation of maladaptive memories as a therapeutic target: pre-clinical data and clinical approaches. Front Psychiatry 2014, 5, 107. 20140819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, P; Sperduti, M; Devauchelle, AD; et al. Age-related changes in the functional network underlying specific and general autobiographical memory retrieval: a pivotal role for the anterior cingulate cortex. PLoS One 2013, 8, e82385. 20131218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cabezas, M; Barbas, H. Anterior Cingulate Pathways May Affect Emotions Through Orbitofrontal Cortex. Cereb Cortex 2017, 27, 4891–4910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J; John, Y; Barbas, H. Pathways for Contextual Memory: The Primate Hippocampal Pathway to Anterior Cingulate Cortex. Cereb Cortex 2021, 31, 1807–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolls, ET. The cingulate cortex and limbic systems for emotion, action, and memory. Brain Struct Funct 2019, 224, 3001–3018. 20190826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kredlow, MA; Fenster, RJ; Laurent, ES; et al. Prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and threat processing: implications for PTSD. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 47, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomaes, K; Dorrepaal, E; Draijer, N; et al. Increased anterior cingulate cortex and hippocampus activation in Complex PTSD during encoding of negative words. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2013, 8, 190–200. 20111207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Kolk, B. Posttraumatic stress disorder and the nature of trauma. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 2000, 2, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kensinger, EA; Addis, DR; Atapattu, RK. Amygdala activity at encoding corresponds with memory vividness and with memory for select episodic details. Neuropsychologia 2011, 49, 663–673. 20110122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murty, VP; Ritchey, M; Adcock, RA; et al. fMRI studies of successful emotional memory encoding: A quantitative meta-analysis. Neuropsychologia 2010, 48, 3459–3469. 20100803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šimić, G; Tkalčić, M; Vukić, V; et al. Understanding Emotions: Origins and Roles of the Amygdala. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 20210531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberzon, I; Abelson, JL. Context Processing and the Neurobiology of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Neuron 2016, 92, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, AS; Oler, JA; Tromp do, PM; et al. Extending the amygdala in theories of threat processing. Trends Neurosci 2015, 38, 319–329. 20150404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etkin, A; Egner, T; Kalisch, R. Emotional processing in anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex. Trends Cogn Sci 2011, 15, 85–93. 20101216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, BL; Eisenberg, ML; Bailey, HR; et al. PTSD is associated with impaired event processing and memory for everyday events. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications 2022, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharot, T; Riccardi, AM; Raio, CM; et al. Neural mechanisms mediating optimism bias. Nature 2007, 450, 102–105. 20071024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, G; Koch, K; Schachtzabel, C; et al. Self-referential processing influences functional activation during cognitive control: an fMRI study. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2013, 8, 828–837. 20120713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanius, RA; Bluhm, RL; Frewen, PA. How understanding the neurobiology of complex post-traumatic stress disorder can inform clinical practice: a social cognitive and affective neuroscience approach. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2011, 124, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Kolk, BA. Clinical Implications of Neuroscience Research in PTSD. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2006, 1071, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, M; Evans, S; Marks, R; et al. “I am not pain, I have pain”: A pilot study examining iRest yoga nidra as a mind-body intervention for persistent pain. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice 2025, 59, 101955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueser, KT; Gottlieb, JD; Xie, H; et al. Evaluation of cognitive restructuring for post-traumatic stress disorder in people with severe mental illness. Br J Psychiatry 2015, 206, 501–508. 20150409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J. Trauma-informed stabilisation treatment: A new approach to treating unsafe behaviour. Australian Clinical Psychologist 2017, 3, 1744. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X; Hack, LM; Bertrand, C; et al. Negative Affect Circuit Subtypes and Neural, Behavioral, and Affective Responses to MDMA: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Network Open 2025, 8, e257803–e257803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, DA; Chao, L; Neylan, TC; et al. Association among anterior cingulate cortex volume, psychophysiological response, and PTSD diagnosis in a Veteran sample. Neurobiol Learn Mem 2018, 155, 189–196. 20180804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart-Harris, RL; Murphy, K; Leech, R; et al. The Effects of Acutely Administered 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine on Spontaneous Brain Function in Healthy Volunteers Measured with Arterial Spin Labeling and Blood Oxygen Level-Dependent Resting State Functional Connectivity. Biol Psychiatry 2015, 78, 554–562. 20140110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sottile, RJ; Vida, T. A proposed mechanism for the MDMA-mediated extinction of traumatic memories in PTSD patients treated with MDMA-assisted therapy. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 991753. 20221012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doss, MK; Weafer, J; Gallo, DA; et al. MDMA Impairs Both the Encoding and Retrieval of Emotional Recollections. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018, 43, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoma, J; Lear, MK. MDMA-Assisted Therapy as a Means to Alter Affective, Cognitive, Behavioral, and Neurological Systems Underlying Social Dysfunction in Social Anxiety Disorder. Front Psychiatry 2021, 12, 733893. 20210927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, G; Phan, KL; Angstadt, M; et al. Effects of MDMA on sociability and neural response to social threat and social reward. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009, 207, 73–83. 20090813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattuso, JJ; Perkins, D; Ruffell, S; et al. Default Mode Network Modulation by Psychedelics: A Systematic Review. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2023, 26, 155–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, Y; Bershad, AK. Altered States and Social Bonds: Effects of MDMA and Serotonergic Psychedelics on Social Behavior as a Mechanism Underlying Substance-Assisted Therapy. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging 2024, 9, 490–499. 20240209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Kolk, BA; Wang, JB; Yehuda, R; et al. Effects of MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD on self-experience. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0295926. 20240110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sar, V. Developmental trauma, complex PTSD, and the current proposal of DSM-5. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2011, 2 20110307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akiki, TJ; Averill, CL; Abdallah, CG. A Network-Based Neurobiological Model of PTSD: Evidence From Structural and Functional Neuroimaging Studies. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2017, 19, 81. 20170919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomason, ME; Marusak, HA. Toward understanding the impact of trauma on the early developing human brain. Neuroscience 2017, 342, 55–67. 20160215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, D. An Enduring Somatic Threat Model of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Due to Acute Life-Threatening Medical Events. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 2014, 8, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkeland, MS; Skar, AS; Jensen, TK. Understanding the relationships between trauma type and individual posttraumatic stress symptoms: a cross-sectional study of a clinical sample of children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2022, 63, 1496–1504. 20220318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiser, LJ; Nurse, W; Lucksted, A; et al. Understanding the Impact of Trauma on Family Life From the Viewpoint of Female Caregivers Living in Urban Poverty. Traumatology (Tallahass Fla) 2008, 14, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baroncelli, CMC; Lodder, P; van der Lee, M; et al. The role of enmeshment and undeveloped self, subjugation and self-sacrifice in childhood trauma and attachment related problems: The relationship with self-concept clarity. Acta Psychologica 2025, 254, 104839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, GD. Pictures of pain: their contribution to the neuroscience of empathy. Brain 2015, 138, 812–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, JD; Courtois, CA. Complex PTSD and borderline personality disorder. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation 2021, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumont, GJ; Sweep, FC; van der Steen, R; et al. Increased oxytocin concentrations and prosocial feelings in humans after ecstasy (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine) administration. Soc Neurosci 2009, 4, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borissova, A; Ferguson, B; Wall, MB; et al. Acute effects of MDMA on trust, cooperative behaviour and empathy: A double-blind, placebo-controlled experiment. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2021, 35, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, AE; Back, AL. Psychoanalytically informed MDMA-assisted therapy for pathological narcissism: a novel theoretical approach. Front Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1529427. 20250402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, G; McNamara, S; Gunturu, S. Trauma-Informed Therapy. In StatPearls; Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda, R. Understanding Heterogeneous Effects of Trauma Exposure: Relevance to Postmortem Studies of PTSD. Psychiatry 2004, 67, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, B. Prazosin in the treatment of PTSD. J Psychiatr Pract 2014, 20, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nirmalani-Gandhy, A; Sanchez, D; Catalano, G. Terazosin for the treatment of trauma-related nightmares: a report of 4 cases. Clin Neuropharmacol 2015, 38, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C; Koola, MM. Evidence for Using Doxazosin in the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Psychiatr Ann 2016, 46, 553–555. 20160912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, F; Raskind, MA. The alpha1-adrenergic antagonist prazosin improves sleep and nightmares in civilian trauma posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2002, 22, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnsten, AFT; Raskind, MA; Taylor, FB; et al. The effects of stress exposure on prefrontal cortex: Translating basic research into successful treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder. Neurobiology of Stress 2015, 1, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaslavski, A; Gross, AH; Israel, S; et al. The effect of MDMA administration on oxytocin concentration levels: systematic review and a multilevel meta-analysis in humans. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2025, 177, 106324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burek, GA; Waite, MR; Heslin, K; et al. Low-dose clonidine in veterans with Posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2021, 137, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, LK. Guanfacine as an Adjunct Treatment for Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Case Report. J Korean Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2025, 36, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y; Li, Y; Han, D; et al. Effect of Dexmedetomidine on Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Patients Undergoing Emergency Trauma Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Network Open 2023, 6, e2318611–e2318611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arluk, S; Matar, MA; Carmi, L; et al. MDMA treatment paired with a trauma-cue promotes adaptive stress responses in a translational model of PTSD in rats. Transl Psychiatry 2022, 12, 181. 20220503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkin, MR; Schwartz, TL. Alpha-2 receptor agonists for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Drugs Context 2015, 4, 212286. 20150814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recchia, A; Tonti, MP; Mirabella, L; et al. The Pharmacological Class Alpha 2 Agonists for Stress Control in Patients with Respiratory Failure: The Main Actor in the Different Acts. Stresses 2023, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bexis, S; Docherty, JR. Role of alpha2A-adrenoceptors in the effects of MDMA on body temperature in the mouse. Br J Pharmacol 2005, 146, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessa, B; Higbed, L; Nutt, D. A Review of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-Assisted Psychotherapy. Front Psychiatry 2019, 10, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carhart-Harris, RL; Wall, MB; Erritzoe, D; et al. The effect of acutely administered MDMA on subjective and BOLD-fMRI responses to favourite and worst autobiographical memories. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2014, 17, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, D; Markel, B. An Integrative Approach to Conceptualizing and Treating Complex Trauma. Psychoanalytic Social Work 2016, 23, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busso, DS; McLaughlin, KA; Sheridan, MA. Media exposure and sympathetic nervous system reactivity predict PTSD symptoms after the Boston marathon bombings. Depress Anxiety 2014, 31, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).