1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the accompanying disease COVID-19, the first outbreak of which was in China in December 2019, became a worldwide pandemic by 2020. The frequency of deaths due to severe COVID-19 has decreased due to the spread of vaccination, the development of guidelines, and the development of antiviral drugs. On May 8, 2023, the new coronavirus infection was reclassified in Japan from Category 2 in which can the government to recommend hospitalization, restrict work, and request that people refrain from going out the less severe Category 5. However, even in Japan, the severity level of COVID-19 is higher than that of influenza [

1,

2], and COVID-19 can leave serious sequelae [

3]. Antiviral drugs have been reported to reduce the severity of COVID-19 and the frequency of hospitalization [

4]. It is thus important that clinicians make an early definitive diagnosis of COVID-19 and administer the appropriate treatment to high-risk patients, in part because this will contribute to the maintenance of a healthy population by controlling the pandemic, the number of deaths, and the number of patients with sequelae.

The most accurate and sensitive method for the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection at this time is the nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) provided by a reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Since the most advanced equipment for virus detection by RT-PCR requires a certain level of technology, expensive equipment, and a large installation space for data processing, many clinicians are obliged to request testing by a specialized laboratory that uses patient materials collected at general medical facilities, and it takes more than a half day (including the time to keep and transfer the materials) to obtain the results. However, there are also testing devices on the market that can be used in general medical facilities and can obtain results within 1 hour by using constant-temperature nucleic acid amplification and nucleic acid labeling in combination. One example of these devices is the Abbott ID NOW™ (AIN) test, which uses a NAAT that applies the method known as nicking enzyme amplification reaction (NEAR), which proceeds with an isothermal reaction. It takes <12 min to get the results and the device can be installed in small areas of general clinics. However, in an earlier study that used dried samples, the original (2019) version of the AIN test did not show superior sensitivity or accuracy compared to other NAATs [

5,

6].

In the treatment of infectious diseases, it is especially important for clinicians to know the precise extent of symptoms that are reflected in the positive results of a test. For example, in clinical settings the positivity rate of influenza antigen tests is low immediately after a patient’s fever, and it is common for retests to be positive when patients' symptoms worsen. If COVID-19 is suspected, data regarding how close fever and other symptoms correlate with the positivity rate would be extremely helpful to medical personnel seeking to diagnose symptomatic patients. However, our research of the relevant literature did not identify any studies that examined a sufficient number of cases to determine which if any symptoms can be detected by the AIN with the use of fresh patient samples.

During the period when COVID-19 was classified as a Category 2 infectious disease in Japan, individuals who were in close contact with a person who had been infected with SARS-CoV-2 were forcibly quarantined by law, and most of these close-contact individuals who developed a fever during the isolation period were later confirmed to have COVID-19. In the present study, we compared the presence and absence of symptoms in close-contact individuals who were treated during the Category 2 period, focusing on their fever status, associated symptoms, and AIN results.

The current Abbott ID NOW device is an updated version, but the original 2019 version was used in this study, and the method of collection from the nasopharynx did not deviate from the original version's package insert.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the HIROSHIMA Prefectural Medical Association (Hirokenrin-0030, November-18th, 2024). This retrospective study using was conducted in Japan. In accordance with the notification by Japan's Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW), SARS-CoV-2 NAATs administered with special public support had been used before May 7, 2023 for (i) individuals who had been in close contact with someone who had a confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection (after the MHLW's notification change, this was modified as individuals with symptoms), (ii) patients with severe symptoms suspected of COVID-19, (iii) those with prolonged symptoms suspected of COVID-19, and (iv) patients who had serious underlying diseases even during a short period after the suspected onset of COVID-19.

Our present study population was comprised of individuals who had reported being in close contact with one or more SARS-CoV-2-infected persons. Each of the study subjects' cases was investigated with an AIN administered at the Kunimoto ENT Clinic (Hiroshima, Japan) between January 14, 2022, and May 7, 2023 (the end of Category 2). Each subject's testing was covered by Japan's national healthcare insurance. In Japan, BA.5 replaced BA.2 around July 2022 [

7] and most of this study sample is believed to be the Omicron variants.

2.2. Data Collection

The subjects (or their guardians of children and people with intellectual disabilities and dementia) choose one NAAT method after the advantages and disadvantages of the RT-PCR and NEAR methods were fully explained to them, i.e., RT-PCR is more sensitive and accurate, but it takes longer to obtain results.

The value of the subject's maximum fever from onset and complaints (excluding fever) were collected without questionnaires over the phone or face-to-face at the subject's first visit to the clinic; personal protective equipment (PPE) was used. And those data were exactly written on medical records, Complaints (i.e., pharyngeal pain, cough, headache/heaviness, general fatigue, nasal discharge, joint pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, ague, hoarseness, taste disorder, dyspnea, olfactory disorders, and dysphagia) on medical records were analyzed as symptoms. Systemic findings (heart sounds, respiratory sounds) and local findings (mouth, nose, pharyngeal cavity, and epiglottis, with the addition of the eardrums in children) were assessed at the Kunimoto ENT Clinic's fever-outpatient center (with PPE).

2.3. Sample Collection

Samples for the NEAR method were collected from only one side of the subject's nasopharynx by slowly rotating a thin diameter 'Ex swab 002 nasal sterile swab R' (Copan Italia, Brescia, Italy) after the swab reached the nasopharynx. All of the samples obtained were immediately assessed at the Clinic with the Abbott ID NOW™ COVID-19 (AIN) test (Abbott Global Point of Care, Charlottesville, VA, USA) while they were fresh.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All source data was separated from the computer and stored in a highly secure location, and anonymized data was shared with co-authors and used for analysis. The anonymous data was accessed for research purposes in 4/May/2025 format.

The significance of differences among the subjects' data were examined with the χ2-test.

3. Results

The total number of tests performed with AIN for SARS-CoV-2 at the fever outpatient clinic of the Kunimoto ENT clinic during the study period was 661. The total number of subjects with a positive SARS-CoV-2 result was 427 (65% positive rate).

It is also possible to use the AIN test for infants by using a fine-diameter swab.

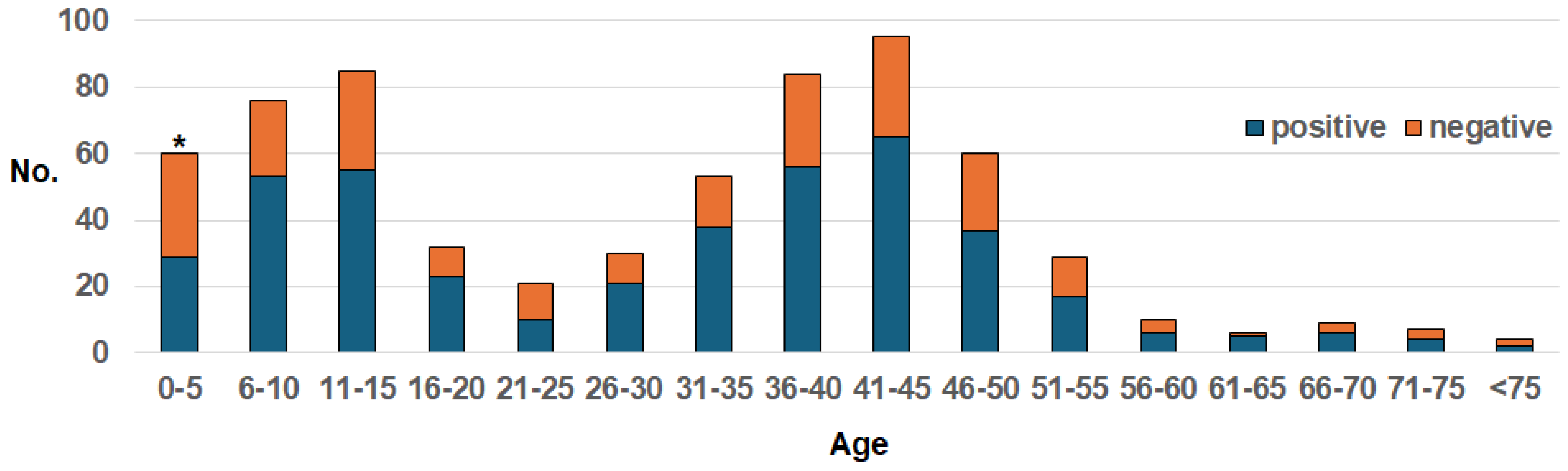

Figure 1 depicts the age distribution of the study subjects for whom the AIN was applied. There were bimodal breaks in the 0- to 15-year-old and 36- to 50-year-old groups. Our comparison of the aggregate of the ≤5-year-old subjects and the ≥6-year-old subjects revealed that the positive-detection rate was significantly lower in the former subjects (p=0.0027).

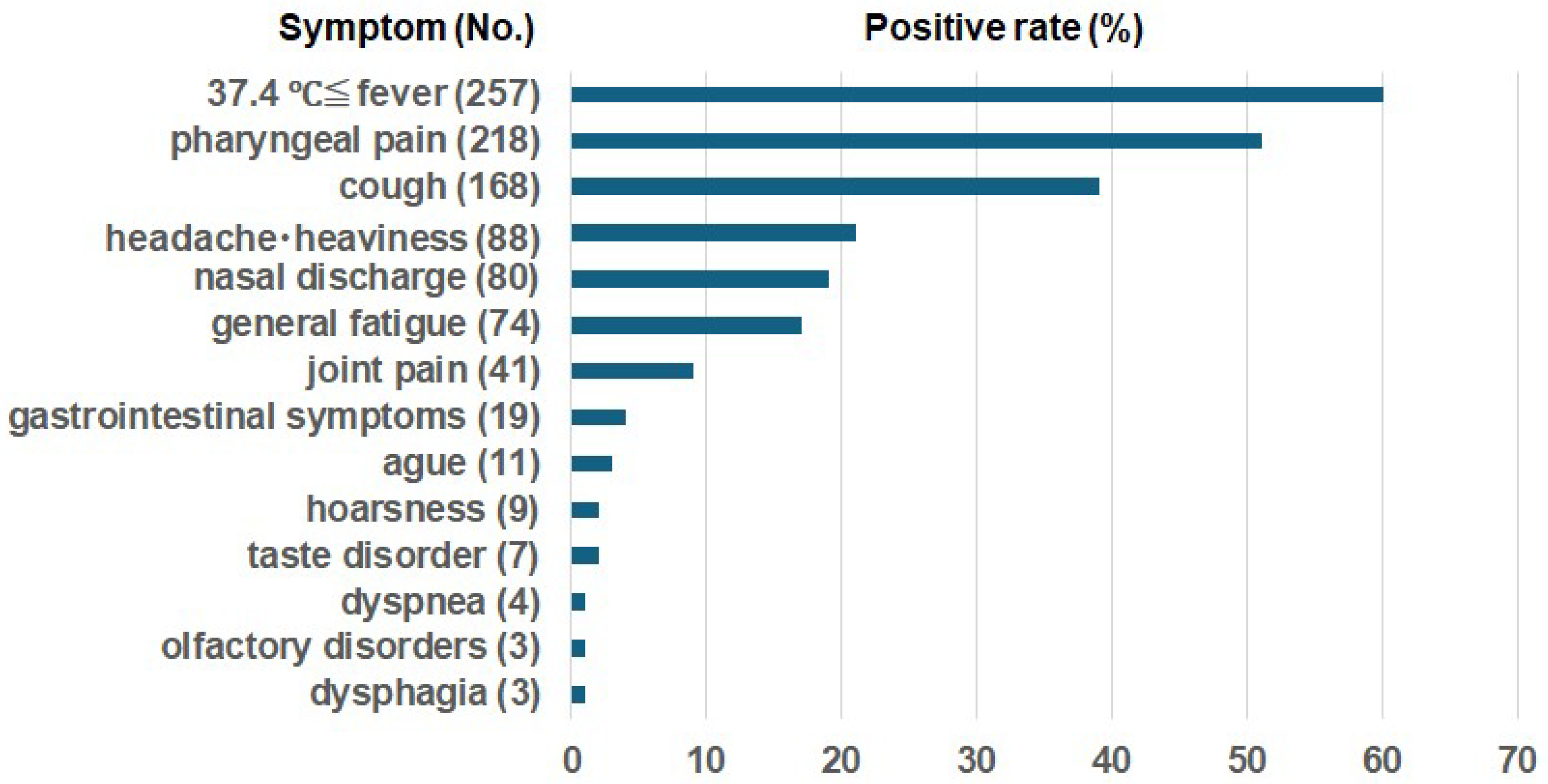

Symptoms other than fever were documented in 394 subjects: one symptom, n=114; two symptoms, n=140; three symptoms, n=92; four symptoms, n=40; five symptoms, n=7; and six symptoms, n=1.

Figure 2 illustrates the frequencies of fever and symptoms other than fever in the SARS-CoV-2-positive cases revealed by AIN. At the time of the initial visit, the fever rate of the positive patients was 60%, and the most common symptoms were cough and pharyngeal pain (

Figure 2). There were also symptoms concerning taste disorder, olfactory disorders, and dyspnea (

Figure 2).

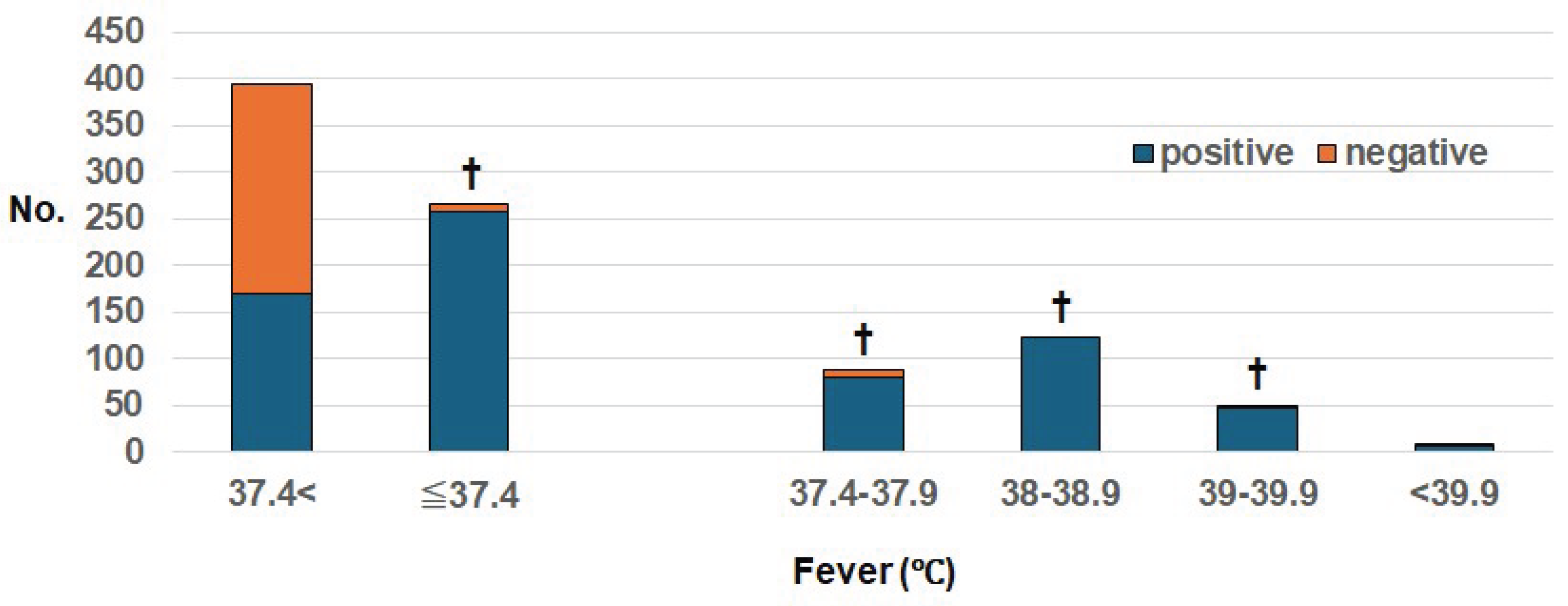

We compared the presence or absence of fever and the positivity rate when the NEAR method was used (

Table 1,

Figure 3). The positivity rate was 97% (257/266) in the presence of fever >37.4°C, which was significantly higher compared to the presence of fever <37.4°C (170/395, 43%) (p<0.000001).

Even among the close contacts without symptoms (fever or other symptoms), 12% of the AIN results were positive (

Table 2). In the AIN-tested subjects, the positivity rate for fever was 97% (257/266), that for symptoms alone other than fever was 99% (141/143) and that for both symptoms and fever were 98% (253/259). The positivity rate for symptoms (both plus alone)was 99% (394/402).

4. Discussion

At the beginning of this investigation's study period, the SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid test with the highest detection sensitivity in Japan was the RT-PCR method using the Cobas system, and the nucleic acid test with the shortest detection time was the NEAR method using the Abbott ID NOW device. Among the subjects enrolled in this study, the SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid test method was selected by the subjects themselves after they had received an explanation of the advantages and disadvantages of both RT-PCR, which has good sensitivity at the time of testing but requires a longer time to get the result, and NEAR, which provides results within a short period of time but does not have high positive sensitivity. Of the 737 individuals in this study who had been in close contact with someone who had COVID-19, 661 chose the NEAR method and 76 chose RT-PCR (Data not shown). People generally tend to choose a test that provides its result faster.

A comparison of the current limits of positive detection of RT-PCR and NEAR using the Cobas system and a diluent has been reported; Fung et al. directly compared the SARS-CoV-2 analytical limits of detection using serial dilutions in vitro, and they reported that the limits of detection of the Cobas analyzer ranged from ≤10 to 74 copies/mL and those for sample point-of-care instruments (e.g., the Abbott ID NOW) were 167–511 copies/mL [

8]. These data demonstrated that the Cobas analyzer is more sensitive than the Abbot ID NOW (AIN) device.

Smithgall et al. compared the detection rate provided by NEAR using dry specimens that were after collection with the detection rate provided by RT-PCR conducted with viral media immediately after collection [

9]. They reported that the detection of SARS-CoV-2 with AIN on dry nasopharyngeal swabs showed positive agreement with the AIN at 73.9% to positive results of Cobas analyzer in viral transport media. In addition, the negative agreement rate with AIN was 100%. [

8]. Jin et al. described the use of the AIN performed by directly dipping dry swabs from patients into sample receivers; they used 8,043 samples. The performance variation of the AIN was independent of the Ct value of a Cobas SARS-CoV-2 assessment of the same samples and was estimated to detect 83.5% of the Cobas positive results [

10]. The AIN using dry samples was reported to have 96.5% accuracy with sensitivity and specificity that are comparable to that of the standard RT-qPCR performed with a Bioer LineGene 9600 Plus Fluorescent Quantitative Detection System [

11]. In a comparison with Roche Cobas results for 84 samples, Arakawa et al. observed that the new 2.0 version of the AIN test showed 94.7% sensitivity and 100%specificity [

12].

The results of the above-cited studies, taken together, demonstrated that (i) the AIN test with the use of dry samples had a negative detection result that was the same as that of RT-PCR, but (ii) its positive detection rate was inferior to that of RT-PCR. In addition, a review of the detection rate of the AIN test using dried samples revealed that this test's negative detection sensitivity is similar to that of many other RT-PCR techniques, but its positive detection sensitivity is inferior to that of other SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid tests [

5,

6]. In most clinics of Japan, NEAR is performed using fresh patient samples immediately after their collection. However, our literature search identified no reports of a study of the positivity rate in fresh samples tested immediately after collection in a sufficient number of cases.

In clinical practice, it is important to understand the degree of fever, the presence or absence of various symptoms, and the positive test rate of the testing equipment used. This is because when a positive result is predicted for fever and symptoms in the diagnosis of infectious diseases, but the result is negative, the likelihood of other diseases increases. The primary purpose of this study was to compare the detection rate of the Abbott ID NOW device with the presence or absence of fever and symptoms.

At the time of this study's subject enrollment, individuals who had been in close contact with someone with COVID-19 had to be quarantined by law, and thus most symptomatic people or those who developed symptoms while quarantined at home would have had secondary COVID-19 infections. However, we did not want to exclude people with fever due to other diseases because they did not undergo RT-PCR testing at the same time as the availability of the AIN test or could not be confirmed by antibody tests later and did not undergo tests for other viruses and bacteria. As a result, the possibility that our study populations included people who were infected with diseases other than COVID-19 (reducing the positivity rates) cannot be ruled out and that presented false negative.

When the AIN test is used to investigate SARS-CoV-2 infection, nasopharyngeal specimens are collected by slowly rotating the tip of a small-diameter swab in the nasopharynx after it reaches the nasopharynx, a method that does not deviate from the original 2019 package insert. By collecting samples using narrow-diameter swabs, it is possible to collect samples from the nasopharynx of infants, and there were positive cases among infants in the present study population. However, the detection rate for the children ≤5 years of age in this study was significantly lower than those for older age groups. It is not clear whether this is due to the dwindling number of cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection among infants or the low viral load. It has been reported that there are SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals even among asymptomatic populations [

13,

14,

15,

16], and in our present population, 12% of the asymptomatic people were evaluated positively. Even if close contact with a SARS-CoV-2-infected person results in an asymptomatic state, it is necessary for such individuals to take precautions to avoid tertiary infections of others and to visit a medical institution immediately after the onset of symptoms in cases in which symptoms worsen.

Our analyses revealed that with the use of a fresh sample from the nasopharynx with a narrow-diameter swab for the AIN test, the positive rate was 98% (394/402) among the quarantined close-contacts with one or more of the following symptoms (general malaise, sore throat, cough, headache, nasal discharge, decreased or impaired sense of smell and taste) (

Table 2). This result provides valuable information for diagnosing symptomatic individuals in clinical practice.

We also observed that with the use of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid test in which fresh samples taken from the nasopharynx were collected with a narrow-diameter swab, the positivity rate of the close contacts with a fever ≥ 37.4°C was 96.8% (257/266). The detection rate of SARS-CoV-2 with the AIN test was thus sensitive enough for fever patients in clinical settings.

The results of our analyses demonstrated that the positivity rate of the AIN-tested patients with fevers ≥37.4°C and that of the AIN-tested symptomatic patients were remarkably high, which may be because the AIN used fresh samples collected from the nasopharynx. These results suggest that other causative diseases should be strongly considered in clinical diagnoses of individuals with fever or symptoms if the result of the AIN using with a fresh nasopharyngeal specimen is negative.

5. Conclusions

We examined and compared the detection rate, fever, and symptoms of individuals with fresh nasopharyngeal specimens evaluated by the Abbott ID NOW COVID-19 test among 661 persons who were in close contact with SARS-CoV-2-infected people who were legally quarantined at home. The positivity rate for the patients with a fever ≥37.4°C was 97% (257/266). The positivity rate was 98% (394/402) for the patients with one of the following symptoms: general malaise, sore throat, cough, headache, nasal discharge, and decreased or absent sense of smell or taste. This result suggests that the Abbott ID NOW test, which uses fresh nasopharyngeal specimens, can be expected to have a sufficiently accurate positive rate of detecting SARS-CoV-2 infection among people with a fever ≥37.4°C and those with other symptoms. Additionally, negative results of Abbott ID NOW test suggest that other causative diseases should be strongly considered in clinical diagnoses of individuals with fever or symptoms.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AIN |

Abbott ID NOW™ COVID-19 |

| NAAT |

nucleic acid amplification test |

| RT-PCR |

reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction |

| NEAR |

nicking enzyme amplification reaction |

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K. M.K. and S.T.; methodology, K.K. and M.K.; validation, T.U. and T.H.; formal analysis, K.K. and M.K.; investigation, K.K., M.K., T.K., Y.H., M.N. and C.I.; resources, S.T.; data curation, T.I.; writing—original draft preparation, K.K. and M.K.; writing—review and editing, S.T.; visualization, K.K. and M.K.; supervision, S.T.; project administration, M.K.; funding acquisition, M.K. and S.T.

Funding

This research was supported partly by a grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (no. 25K12743).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient informed consent was obtained in the forms of an opt-out on the website

https://www.kunimoto-clinic.jp/ and of the posters in Kunimoto ENT Clinic from October-28, 2024 to December-18,2024, and these opt-outs were confirmed by staff of the Ethics Committee of the HIROSHIMA Prefectural Medical Association.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- [About the severity and fatality rate of the new corona and points to note regarding its interpretation]. Available online : https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10900000/001027743.pdf [in Japanese] (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Kawashima, T.; Nomura, S.; Tanoue, Y.; Yoneoka, D.; Eguchi, A.; Ng, C.F.S.; Matsuura, K.; Shi, S.; Makiyama, K.; Uryu, S.; et al. Excess all-cause deaths during coronavirus disease pandemic, Japan, January–May 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021, 27, 789–795. https://. [CrossRef]

- Soriano, J.B.; Murthy, S.; Marshal, J.C.; Relan, P, Diaz JV. WHO Clinical Case Definition Working Group on Post-COVID-19 Condition. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022, 22, e102–e107. [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines. National Institutes of Health. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570371/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK570371.pdf. Available online: (accessed on19 June 2025).

- Yamamoto, K.; Ohmagari, N. Microbiological testing for coronavirus disease 2019. JMA J. 2021, 4, 67–75. [CrossRef]

- Ulhaq, Z.S.; Soraya, G.V. The diagnostic accuracy of seven commercial molecular in vitro SARS-CoV-2 detection tests: A rapid meta-analysis. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2021, 21, 733–740. [CrossRef]

- Japan Institute for Health Security, The Infectious Disease Information Website. Overview of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Available online:(accessed on 10 September 2025). https://id-info.jihs.go.jp/diseases/sa/covid-19/290/index.html.

- Fung, B.; Gopez, A.; Servellita, V.; Arevalo, S.; Ho, C.; Deucher, A.; Thornborrow, E.; Chiu, C.; Miller, S. Direct comparison of SARS-CoV-2 analytical limits of detection across seven molecular assays. J Clin Microbiol. 2020, 58, e01535–20. [CrossRef]

- Smithgall, M.C.; Scherberkova, I.; Whittier, S.; Green, D.A. Comparison of Cepheid Xpert Xpress, and Abbott ID NOW to Roche cobas for the Rapid Detection of SARS-CoV-2. J Clin Virol. 2020, 128, 104428. https://doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104428.

- Jin, R.; Pettengill, M.A.; Hartnett, N.L.; Auerbach, H.E.; Peiper, S.C.; Wang, Z. Commercial severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) molecular assays: Superior analytical sensitivity of cobas SARS-CoV-2 relative to NxTAG CoV extended panel and ID NOW COVID-19 test. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2020, 144, 1303–1310. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, S.A.; Ganesan, S.; Ibrahim, E.; Thakre, B.; Teddy, J.G.; Raheja, P.; Zaher, W.A. Evaluation of six different rapid methods for nucleic acid detection of SARS-COV-2 virus. J Med Virol. 2021, 93, 5538–5543. [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, Y.; Nishida, Y.; Sakanashi, D.; Nakamura, A.; Ota, H.; Tokuhiro, S.; Mikamo, H.; Yamagishi, Y. Clinical evaluation of a modified SARS-CoV-2 rapid molecular assay, ID NOW COVID-19 2.0. J Infect Chemother. 2024, 30, 955–957. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Ahmad, F. I.; Lal, SK. COVID-19: A review on the novel coronavirus disease evolution, transmission, detection, control, and prevention. Viruses. 2021, 29, 202. [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, T.; Guo, W.; Guo W.; Zheng J.; Zhang, J.; Dong, C.; Ren Na, R.; Zheng, L.; et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of children with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Med Virol. 2021, 93, 1057–1069. [CrossRef]

- Barboza, J.J.; Chambergo-Michilot, D.; Velasquez-Sotomayor, M.; Silva-Rengifo, C.; Diaz-Arocutipa, C.; Caballero-Alvarado, J.; Garcia-Solorzano, F.O.; Alarcon-Ruiz, C.A.; Albitres-Flores, L.; Malaga, G.; et al. Assessment and management of asymptomatic COVID-19 infection: A systematic review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2021, 41, 102058. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, K.; Rzymski P.; Islam, M.S.; Makuku, R.; Mushtaq, A.; Khan, A.; Ivanovska, M.; Makka, S.A.; Hashem, F.; Marquez, L.; et al. COVID-19 vaccinations: The unknowns, challenges, and hopes. J Med Virol. 2022, 94, 1336–1349. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).