1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC) with major portal vein tumor thrombosis (PVTT) or extrahepatic spread (EHS) are classified as Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage C or as “advanced” HCC [

1]. For this patient population, despite marginal clinical benefits, sorafenib has remained the main treatment option for over a decade [

2,

3,

4]. The overall survival (OS) and/or hazard ratio (HR) of HCC patients with EHS were reported to have no statistically significant differences versus those without EHS (11 versus 9.6 months, p=0.765 for those who received sorafenib [

5] and a HR of 0.803, p=0.547 for those who received lenvatinib [

6]).

Hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) is an effective treatment for advanced HCC [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Zhuang’s meta-analysis [

7] showed a positive objective response rate (ORR, odds ratio 0.13; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.07-0.24) and disease control rate (odds ratio 0.48; 95% CI, 0.26-0.87) for HAIC when compared to sorafenib. Another meta-analysis by Liu found better OS and progression-free survival (PFS) for the HAIC group compared to the sorafenib group in HCC with PVTT [

8]. Other studies have shown that combining HAIC with sorafenib resulted in better OS rates [

9,

10,

11,

12].

There are significant differences in the nature between patients with advanced HCC population. Whether such patients have also PVTT and EHS are clinical factors influencing survival. Up to 64.7% of HCC cases are accompanied by PVTT [

13]. Previous research and Japanese guidelines suggest that HAIC can be used as a treatment option for HCC with PVTT [

14]. However, there is some controversy regarding whether HAIC is effective for patients with EHS, mainly because HAIC is considered a locoregional therapy and may have limited disease control effects. Previous studies have yielded conflicting results regarding the effects of EHS on the survival impact of HAIC. Kim et al [

15] reported an OS of 7.6 months without significant survival difference in HCC patients with or without EHS (HR:1.101, p=0.63). Two studies [

16,

17] found that EHS results in poorer OS (7.7 vs 9.8 months and 9.8 vs 14.8 months, respectively) without reaching statistical significance (p=0.068); however, two other studies showed that EHS was an independent factor for OS with HR of 1.76, p=0.0011 [

11] and 1.71,p=0.01 [

18], respectively.

In the present study, 323 unresectable HCC patients with or without EHS were treated with HAIC. The clinical outcomes and risk factors for both groups were analyzed using before and after propensity score matching (PSM). The primary objective of this study is to evaluate the efficacy and safety of HAIC in treating unresectable HCC patients with EHS.

2. Method

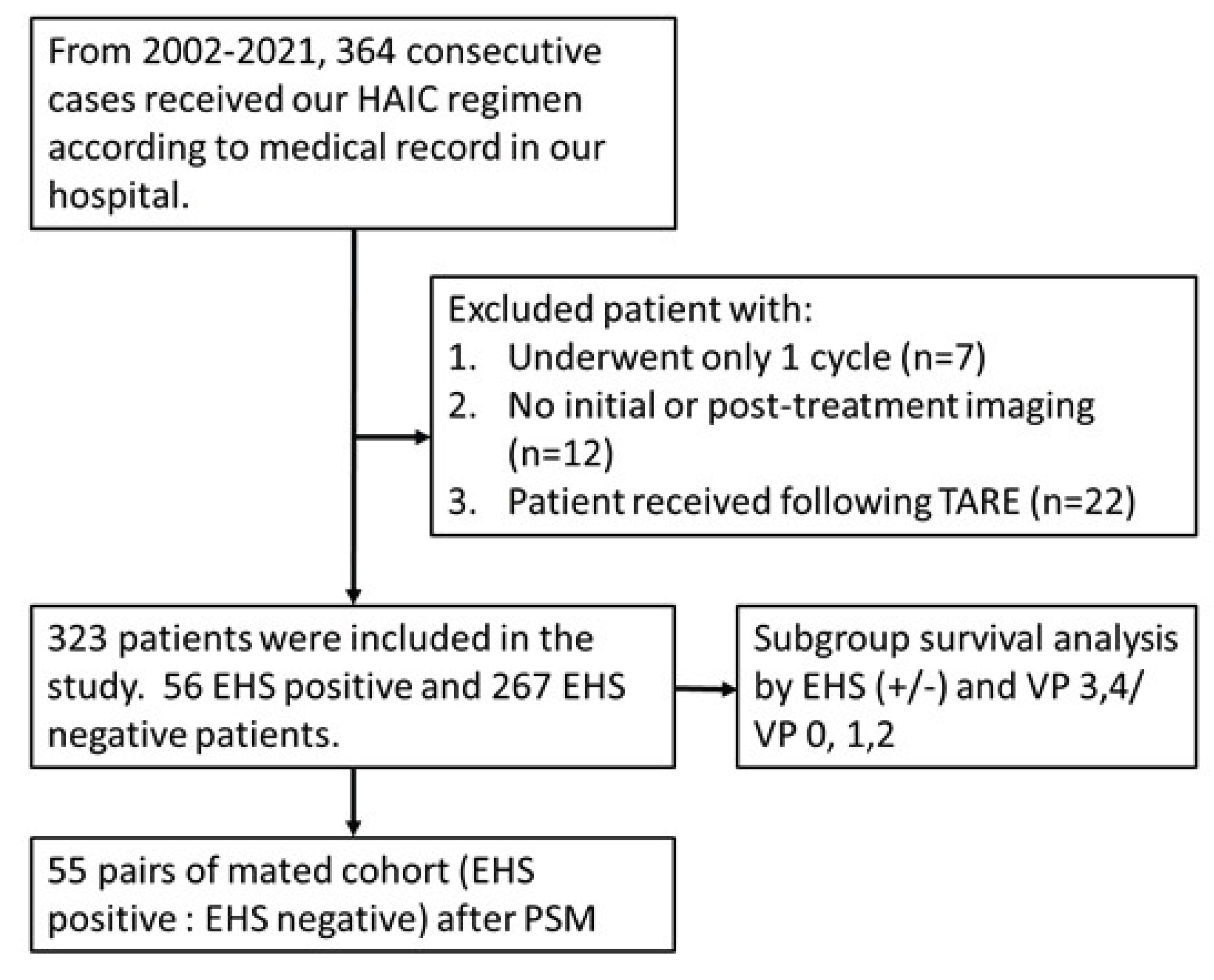

This was a retrospective large cohort study in one single institute with a total of 323 consecutive unresectable HCC patients enrolled at Kaohsiung Veterans General hospital from April 2002 to December 2021. HCC diagnosis was based on imaging with proper clinical context or pathology confirmation. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) patients aged 18 years old or older; (b) Child-Pugh class A and B; (c) platelet counts ≥50,000/cumm; (d) prothrombin time INR ≤1.5; (e) tumor mass ≥ 8cm or with major PVTT or EHS; (f) having received at least two courses of HAIC; and/or(g) ECOG performance status ≤ 2. The exclusion criteria were: (a) patients who subsequently underwent transarterial radioembolization (TARE) and/or (b) did not have initial or post-treatment imaging available on our PACS system (

Figure 1). Patients’ follow-up was performed by reviewing medical records from the PACS system of our hospital with the mean follow-up period of 26.0 ± 31.7months. The follow-up period was ended in December 2023 This retrospective study was approved by the ethics review committee of Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital with patient informed consent waived for this retrospective study.

The severity of PVTT was categorized according to the Japanese VP Staging Classification System [

19], where Vp4 was defined as the presence of a tumor thrombus in the main trunk of the portal vein or a portal vein branch contralateral to the primarily involved lobe; Vp3 and Vp2 as tumor invasion of the first-order and second-order branches respectively; and Vp1 and Vp0 as no visible vascular invasion on images.

HAIC was performed via puncture of the left subclavian artery [

20] with insertion of a 4-French temporary angio-catheter (RC1, Cordis; J-curve, Terumo, Japan) in the proper hepatic artery.The gastroduodenal artery and/or right gastric artery were embolized with metallic coils during the first HAIC therapy to prevent non-target gastrointestinal injury. The HAIC regimen consisted of a daily infusion ofcisplatin (10mg/m

2), mitomycin-C (2mg/m

2), and leucovorin (15mg/m

2), administered over a period of 20-30 minutes, and then a 5-fluorouracil (5-FU, 100mg/m

2) infusion for the remaining of 22 hours of each day, for five consecutive days. Before the temporary catheter was removed, 10 mL ethiodized oil (Lipiodol, Guerbet, France) was injected to obtain a synergistic effect of chemoinfusion and lipiodol microvascular embolization. Neither gelfoam nor any other embolizing particles were injected to prevent potential irreversible liver damage. No permanent delivery port system was used in this study.

As sorafenib was reimbursed in 2010 in Taiwan and available in the study hospital after 2012, combination therapy of HAIC and sorafenib was performed in patients with major PVTT or EHS and Child-Pugh A liver function after 2012.

The interval between each course of the five-day treatment was 6-8 weeks. Multiphasic CT or MRI evaluation for treatment response was performed after every two courses of treatment. As HAIC is a locoregional therapy, intrahepatic tumor response was adopted to judge treatment efficacy instead of disease response. Treatment efficacy was therefore classified into complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD) according to the Modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST) guidelines [

21]. The interpretation of imaging response of the 323 advanced HCC patients was allocated to 3 interventionalists (Chen CT, Liang HL and Chiang CL) with 4-30 years’ experiences of abdominal imaging diagnosis. As the primary goal of this study was to evaluate the HAIC therapeutic outcomes (PFS and OS), thereafter we did not perform the inter-observers’ consistency of interpreting the intrahepatic tumor response.

Propensity score matching (PSM) analysis with one-to-one matching was used to balance baseline characteristics between groups with or without EHS, as well as groups with or without combined sorafenib use. The propensity scores were estimated using a logistic regression model that included the following variables: gender, age, HCC etiology, EHS, maximal tumor size, tumor number, major PVTT, Child-Pugh class, and AFP level. Nearest neighbor matching without replacement was applied, with a caliper set at 0.02.

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to compare progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) between groups, and the log-rank test was used for statistical comparison. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Multivariate analysis using a Cox proportional hazards model was performed to identify clinical factors influencing overall survival. Variables that achieved statistical significance or had a p-value <0.10 in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant in the multivariate analysis. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 26.0, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the statistical analyses.

3. Result

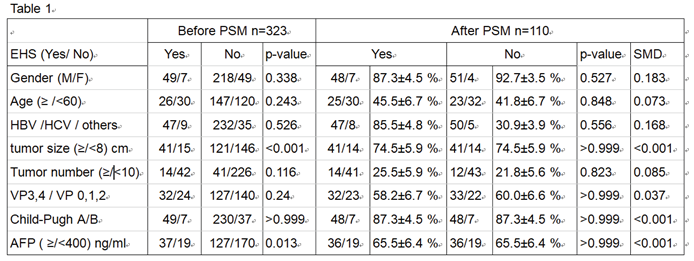

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of all the enrolled patients both before and after PSM. Before matching, the mean age was 60.9± years, with 82.7% of the patients being male. 84.2% of the patients had underlying viral hepatitis (B or C virus infection), and 86.4% were classified as Child-Pugh class A when HAIC treatment began.

Regarding PVTT severity, 25.1% of patients had VP4, 24.1% had VP3, 28.8% had Vp2, and 22% were either Vp0 or Vp1 involvement. Among all enrolled patients, a total of 56 (17.3%) individuals exhibited extrahepatic metastasis (EHS) at the time of enrollment. Of these patients, lung, adrenal gland, and regional lymph nodes metastasis were seen in19, 5, and 37 patients, respectively. Therefore, 265 patients were classified as BCLC-C and 58 were BCLC-B in this study.

The median and mean number of HAIC treatment cycles completed by each patient was 4 and 4.1±1.8.

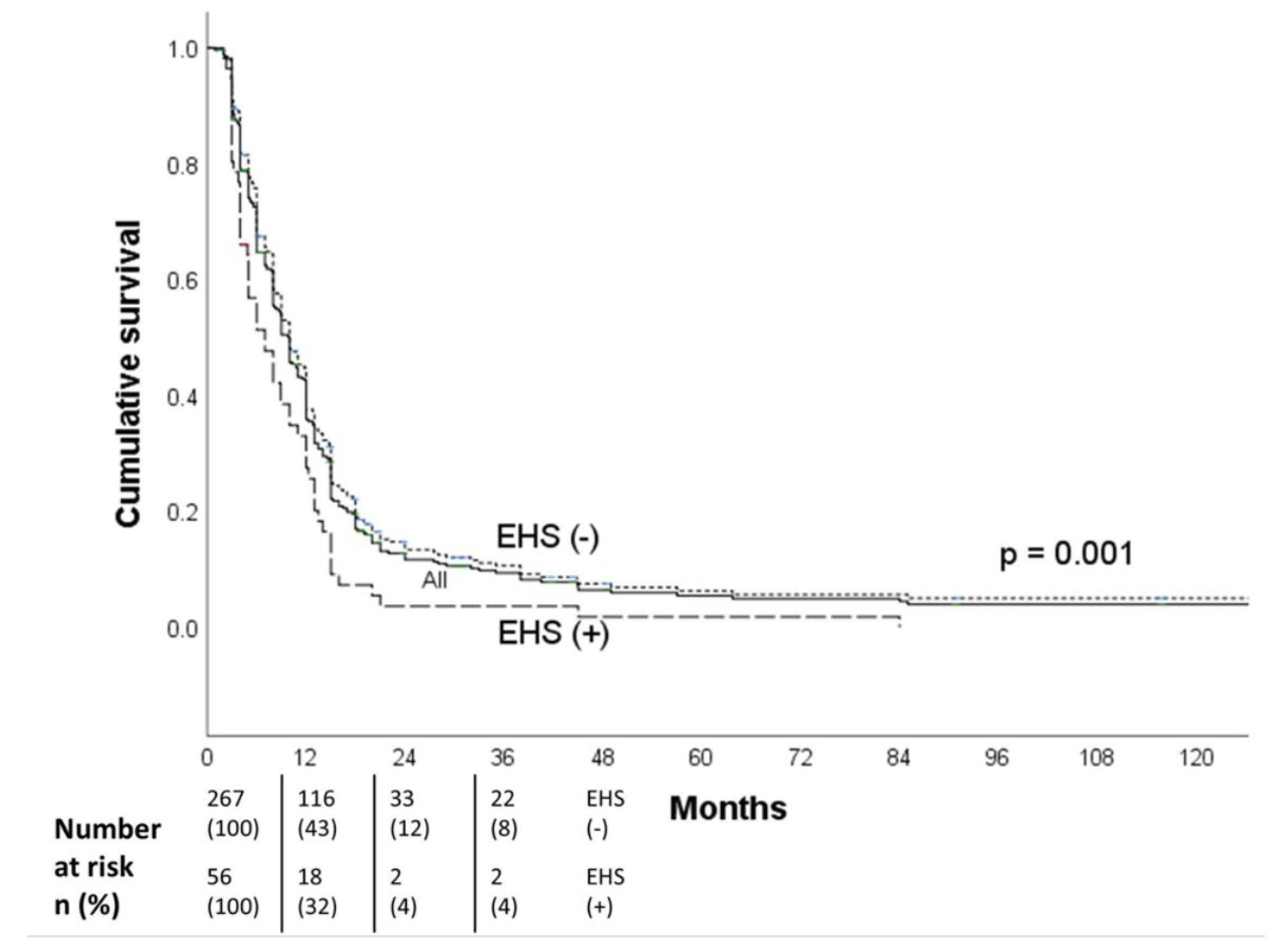

270 of the 323 patients (83.6%) died by June 15, 2023. The intrahepatic treatment response– categorized as all patients, patients without EHS, and patients with EHS – was evaluated using the mRECIST criteria after at least two cycles of HAIC. 13.9% of all patients, 15.4% without EHS, and 7.1% with EHS achieved intrahepatic CR; 5.2%, 45.7%, and 42.9% showed intrahepatic PR; 22.3%, 22.5%, and 21.4% experienced SD; and 18.6%, 16.5%, and 28.6% demonstrated intrahepatic PD, respectively. The objective response rates (ORR) were respectively 59.1%, 61.1%, and 50%. The median PFS were respectively 10.0, 7.0, and 10.0 months, respectively (

Figure 2)

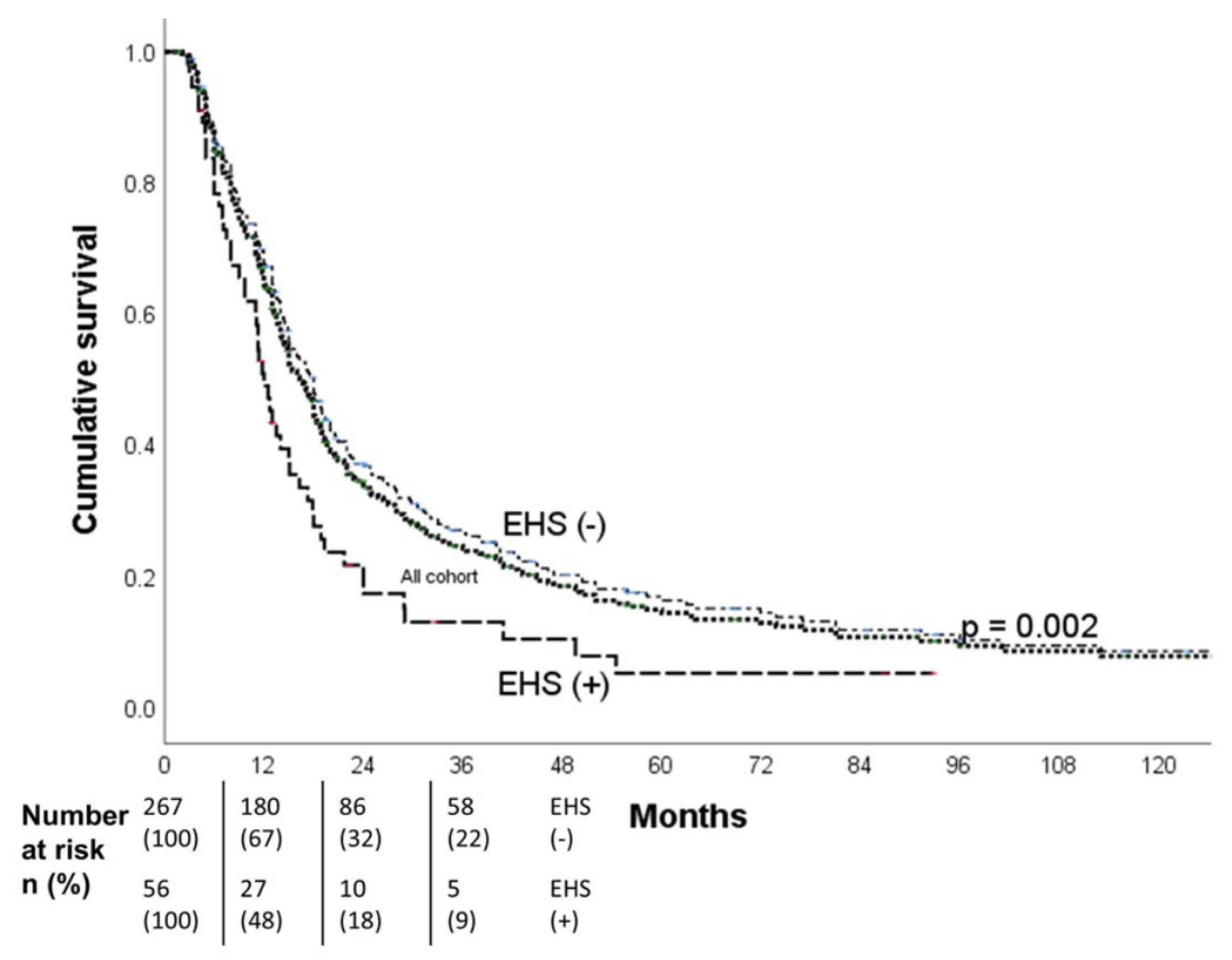

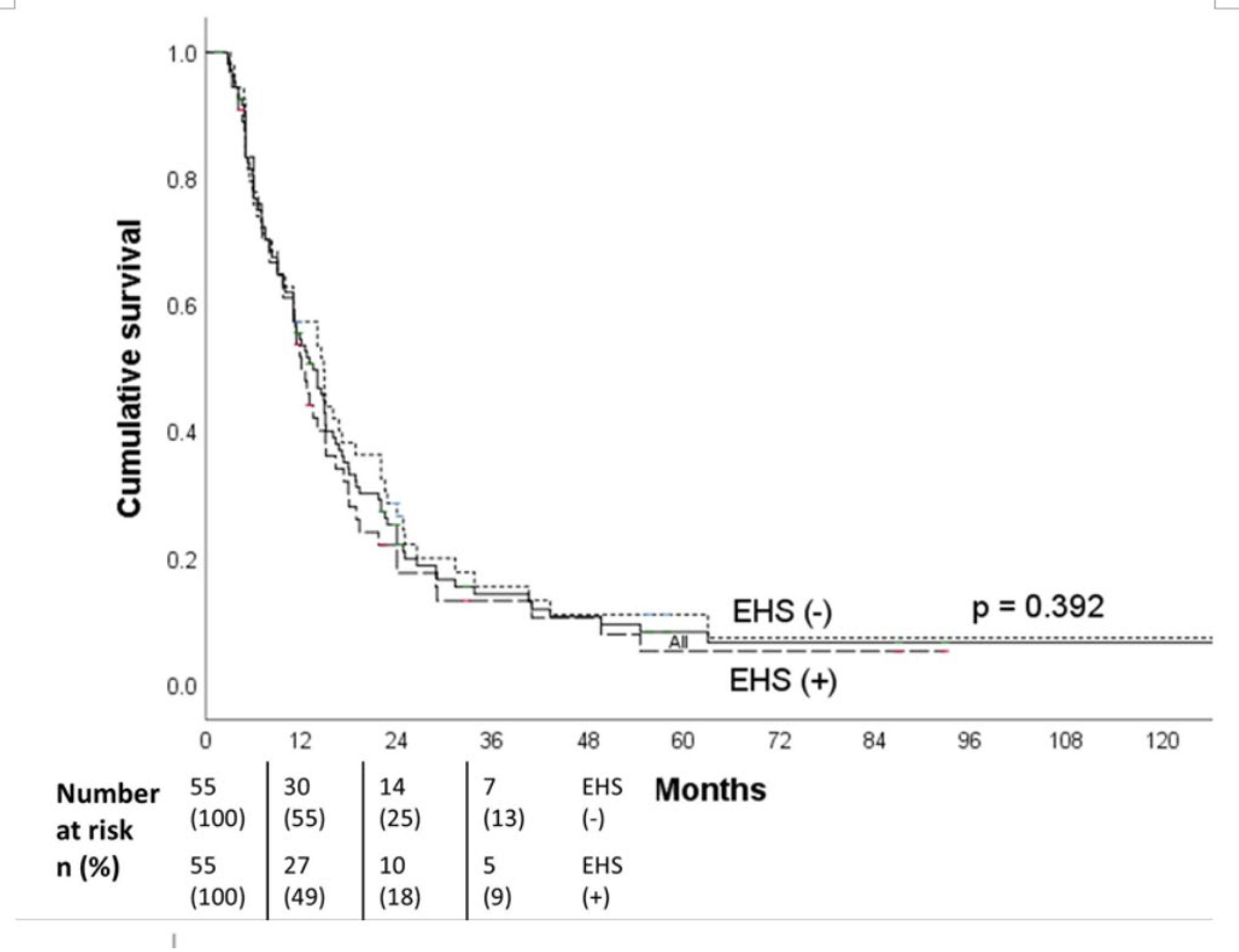

The median OS all patients was 16.3 months (95% CI, 14.5-18.1),18.0 months for the non-EHS patients, and 12.0 months for the EHS patients. The 1-,2- and 3-year OS were respectively 67%, 32%, and 22% for the non-EHS group and 48%, 18%, and 9% for the EHS patients (p=0.002). After PSM (55 pairs), the median OS was 12.0 months (95% CI, 10.0-14.0 months) for the EHS positive group (

Figure 3) and 14.8 months (95% CI, 10.8-18.8 months) for the EHS negative group (

Figure 4). There was no significant difference in survival between the EHS and non-EHS groups (p=0.392). For patients with responders (CR+PR), the median OS of the all initial cohort patients was 24 months(95 % CI, 20.0 -28.0 months), which was significantly longer (p<0.0001) than that of the non-responders’ (SD+ PD) 8.3 months (95 % CI, 7.4-9.2 months).

Subgroup analysis showed the median OS of the total 159 HCC patients with major PVTT was 14.9 months,13.0 months in patients with EHS (95% CI, 9.2-16.8 months) and 15.0 months for those without EHS (95% CI, 12.2-17.8 months).There was no significant difference in survival when comparing EHS and non-EHS patients in the major PVTT group (p=0.407). Of the 164 patients without major PVTT, the median OS was 18.0 months, with 11.4 months for patients with EHS (95% CI, 10.6-12.2 months) being significantly shorter (p<0.001) than the 19.4 months for those without EHS (95% CI, 16.8-22.0 months) (

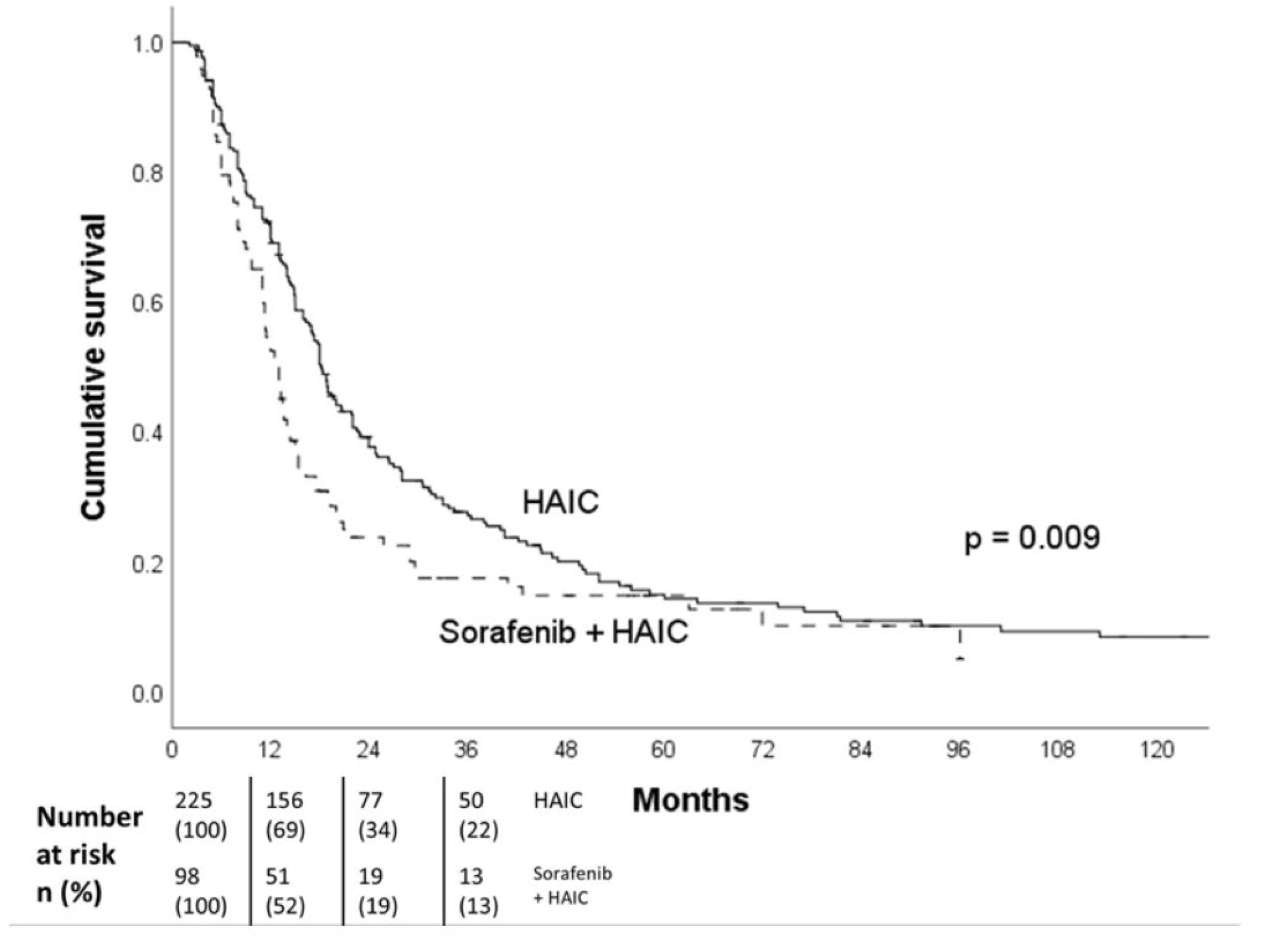

Table 2). Out of the 323 patients included in the study, 98 patients (30.3%) received both HAIC and sorafenib treatment concurrently. There was a survival difference between patients who received HAIC treatment alone and those who received HAIC in combination with sorafenib (18.2 vs 13.0 months, p = 0.009) (

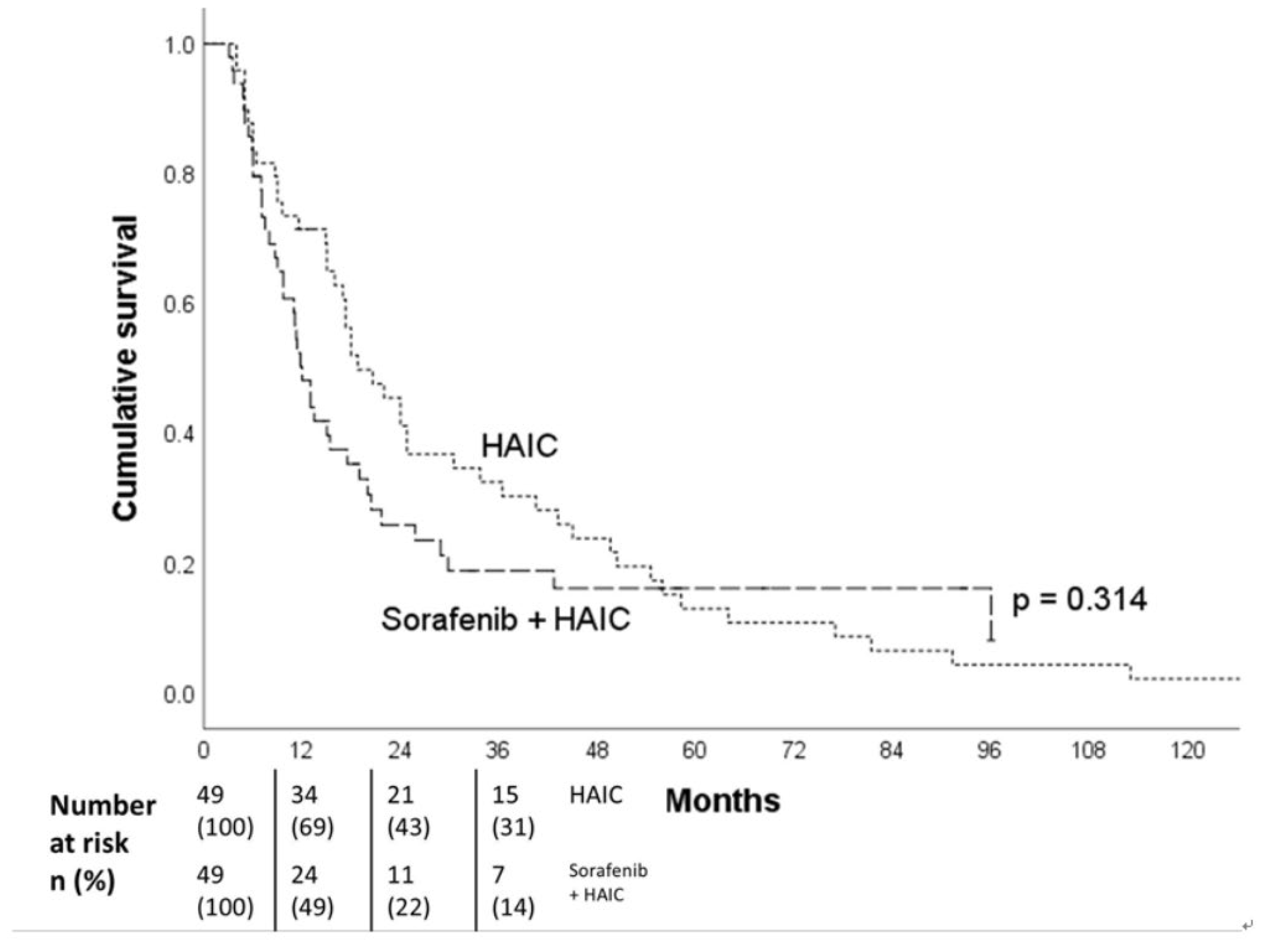

Figure 5). After PSM (49 pairs) adjusting for gender, age, HCC etiology, EHS, maximal tumor size (≥ 8 cm), tumor number (≥10), major PVTT, Child-Pugh class, and AFP level (≥ 400 ng/ml), there was no survival difference between these two groups (18.8 vs 12.0 months, p=0.314) (

Figure 6). As for extrahepatic metastatic sites, there was no significant difference of the median OS between HCC patients with lung and non-lung metastasis (11.3 vs 13 months, p=0.370).

Univariate analysis of the prognostic factors associated with survival is shown in

Figure 7. Positive EHS, maximal tumor size ≥8 cm, tumor number ≥ 10, major PVTT, and AFP level ≥ 400 ng/ml were significant risk factors. Under multivariate analysis, tumor number ≥ 10 (HR 1.505; 95% CI, 1.101-2.058; p= 0.010), and major PVTT (HR 1.298; 95% CI, 1.013-1.663; p= 0.039) were significant risk factors. (

Figure 7)

As to the adverse events of this treatment, none of the patients died due to immediate HAIC complications. Sixty four patients developed fever during HAIC period, and among them, twelve developed bacteremia and were treated successfully by antibiotics. Transient ischemic attacks after catheter removal were encountered in two patients with spontaneous recovery within 3 days. One patient had complicated with a pseudoaneurysm formation in the left punctured subclavian artery, which was treated successfully with a stent graft (Viabahn, 7x50mm, Gore) placement via the left brachial approach. Three patients developed an overt subcutaneous hematoma at the puncture site requiring no further management. No overt adverse events were observed in patients with plus sorafenib therapy

4. Discussion

The present study revealed that the presence of EHS affected overall survival (12.0 vs 18.0 months, p=0.002) throughout the entire cohort of patients with unresectable HCC who received HAIC, which was consistent with the conclusions from those of Iwamoto’s [

11] and Liang’s series [

18]. They both concluded that the presence of EHS and/or along with major PVTT were independent factors in multivariable analysis, whereas our subgroup analysis further indicated that although there was a significant survival difference in ≤ Vp2 HCC patients between with and without EHS patient groups (11.4 vs 19.4 months respectively, p<0.001), there was no significant survival difference in HCC patients with major PVTT (13.0 months with EHS vs 15.0 months without, p=0.407).

These results seemed reasonable, since the OS of HCC patients with major PVTT have poor prognoses of 2.7-4 months under the best supportive care [

22,

23] and 7.6 months with immuno-target combination therapy of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in Vp4 patients [

24]. HCC patients with major PVTT are also reported in the literature to have a high percentage of being associated with EHS (48.3%-83.8%) [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. In the present series, 57.1% HCC patients with major PVTT had EHS. Previous studies suggested that intrahepatic tumor progression was the main cause of advanced HCC-related deaths. If intrahepatic HCC responded to HAIC treatment, it could significantly increase overall survival [

14,

24], but if the ORR of the intrahepatic tumors were low (e.g. <30%), then a shorter OS was inevitable with or without EHS, and no survival difference between these two group patients could be expected [

11,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Although EHS was one of the risk factors for OS in the univariate analysis in the present study, only tumor number (>10) and major PVTT were the prognostic factors in the multivariate analysis. Controlling intrahepatic tumors through HAIC may be more important than controlling extrahepatic tumors, especially in HCC patients with major PVTT. Therefore, adopting an effective HAIC regimen to control the intrahepatic tumor progress is absolutely crucial.

The treatment protocol used in the present study combined HAIC and lipiodol-only microvascular embolization after a 5-day chemoinfusion to obtain a synergistic therapeutic effect. Overall, the study patients had an ORR of 59.1% with CR, PR, SD, and PD rates of 13.9%, 45.2%, 22.3%, and 18.6%, respectively. The median OS of the patients with intrahepatic treatment response (CR plus PR) was 24 months, which was significantly longer than those of without intrahepatic response (SD plus PD, 8.3 months). In addition, the median OS for patients with major PVTT was 14.9 months. Two studies also reported using combination therapies of HAIC with lipiodol injection but sequenced in reverse [

11,

25]; in both studies, the mixture of anticancer drug (cisplatin or epirubicin) and lipiodol was injected at the beginning of the treatment and was then followed by continuous chemoinfusion (5 days for 5-FU in Iwamoto’s series [

11] and one day of oxaliplatin plus leucovorin and 5-FU in Liu’s series [

25]). Iwamoto and Liu respectively reported median OS of 13 and 10 months in patients with major PVTT. It seemed that the additional lipiodol injection may have enhanced the chemo-cytotoxic effect in HAIC treatment, and longer duration of continuous chemoinfusion (e.g. 5 days) may have obtained a better ORR and OS.

Our present study revealed a significant survival difference in ≤ Vp2 HCC patients between with and without EHS (11.4 vs 18 months), that may indicate aggressive treatment of the EHS in these patient group of clinical benefits. Dong et al reported that a combination therapy of HAIC with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab had significantly prolonged the OS of advanced HCC patients than that of immuno-target therapy alone (14.6 vs 11.3 months, p=0.032) [

26]. Thereafter it is possible that combination of our new HAIC regimen with immuno-target therapy and or proton beam therapy for the EHS in may prolong survivals in patients with ≤ Vp2 HCC. But the high medical cost of such a combination therapy should also be taken into consideration.

In the present study, no significant survival difference was found between the EHS-positive and EHS-negative patient groups (p=0.392) nor any between those with and without sorafenib use (p = 0.314) after PSM adjustment. A possible reason is that the percentage of major PVTT patients increased in all patient groups after PSM, and major PVTT was identified as an independent risk factor (HR:1.298) of patients’ survival, while EHS was a risk factor in univariate analysis, but not multivariate.

5. Limitations

The present study had some limitations. It was a retrospective study, so the included patients were highly heterogeneous and may have had selection bias. Additionally, there were no control groups for comparison with other treatment methods. As patients without receiving two courses of HAIC treatment or post-treatment imaging follow-up were excluded, OS may have been skewed in a favorable direction. In the future, a large prospective study is needed to accurately control for the characteristics of enrolled patients in order to identify the patient population suitable for HAIC treatment. Beside, even the study was adjusted by PSM, it cannot account for unmeasured variables.

6. Conclusion

The results of this study suggested that controlling intrahepatic tumors through HAIC is more important than controlling extrahepatic tumors, especially in HCC patients with major PVTT. In addition, locoregional HAIC can be performed in patients with EHS.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Chao-Ting Chen, Huei-Lung Liang, Chia-Ling Chiang and Wei-Lun Tsai; Software, Chao-Ting Chen; Formal analysis, Chao-Ting Chen; Investigation, Chao-Ting Chen and Chia-Ling Chiang; Resources, Yu-Chia Chen; Data curation, Wei-Lun Tsai; Writing – original draft, Chao-Ting Chen and Chia-Ling Chiang; Writing – review & editing, Huei-Lung Liang; Supervision, Yu-Chia Chen.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the subject matter or materials discussed in this article.

References

- Reig, M., Forner, A., Rimola, J., Ferrer-Fàbrega, J., Burrel, M., Garcia-Criado, Á., Kelley, R. K., Galle, P. R., Mazzaferro, V., Salem, R., Sangro, B., Singal, A. G., Vogel, A., Fuster, J., Ayuso, C., & Bruix, J. (2022). BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. Journal of Hepatology, 76(3), 681-693. [CrossRef]

- Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol.2009;10(1),25-34. [CrossRef]

- Rimassa L, and Santoro A.Sorafenib therapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: the SHARP trial. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9(6), 739-745.

- Jackson R, , Psarelli EE, Berhane S, Khan H and Johnson P. Impact of Viral Status on Survival in Patients Receiving Sorafenib for Advanced Hepatocellular Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Phase III Trials. J Clin Oncol. 2017; 35(6), 622-628.

- Nakano M, Tanaka M, Kuromatsu R, Nagamatsu H, Tajiri N, Satani M, et al. Sorafenib for the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with extrahepatic metastasis: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Cancer Med. 2015;4(12), 1836-1843. [CrossRef]

- Chuma M, Uojima H, Hiraoka A, Kobayashi S, Toyoda H, Tada T, et al. Analysis of efficacy of lenvatinib treatment in highly advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with tumor thrombus in the main trunk of the portal vein or tumor with more than 50% liver occupation: A multicenter analysis. Hepatol Res. 2021;51(2), 201-215. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang BW, Li W, Xie XH, Hu HT, Lu MD, Xie XY. Sorafenib versus hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2019;49(9), 845-855.

- Liu M,Shi J, Mou T, Wang Y, Wu Z, and ShenA. Systematic review of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy versus sorafenib in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020; 35(8), 1277-1287. [CrossRef]

- Zheng K, Zhu X, Fu S, Cao G, Li WQ, Xu L, et al. Sorafenib Plus Hepatic Arterial Infusion Chemotherapy versus Sorafenib for Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Major Portal Vein Tumor Thrombosis: A Randomized Trial.Radiology. 2022;303(2), 455-464. [CrossRef]

- He M, Li Q, Zou R, Shen JX, Fang WQ, Tan GS, et al. Sorafenib Plus Hepatic Arterial Infusion of Oxaliplatin, Fluorouracil, and Leucovorin vs Sorafenib Alone for Hepatocellular Carcinoma With Portal Vein Invasion: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(7), 953-960.

- Iwamoto H, Niizeki T, Nagamatsu H, Ueshima K, Tani J, Kuzuya T, et al. The Clinical Impact of Hepatic Arterial Infusion Chemotherapy New-FP for Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Preserved Liver Function. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(19), 4873. [CrossRef]

- Li MF, Liang HL, Chiang CL, Tsai WL, Chen WC, Tsai CC,et al. New Regimen of Combining Hepatic Arterial Infusion Chemotherapy and Lipiodol Embolization in Treating Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Main Portal Vein Invasion. J Pers Med 2022;13(1), 88.

- Nakashima T,Okuda K, Kojiro M, Jimi A, Yamaguchi R, Sakamoto K, et al. Pathology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan. 232 Consecutive cases autopsied in ten years. Cancer 1983; 51(5), 863-877.

- Kudo M,Matsui O, Izumi N, Iijima H, Kadoya M, ImaiY, et al. JSH Consensus-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2014 Update by the Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan.Liver Cancer. 2014; 3(3-4), 458-468. [CrossRef]

- Kim B,Won JH, Kim J, Kwon Y, Cho HJ, Huh J, et al. Hepatic Arterial Infusion Chemotherapy for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Radiologic and Clinical Factors Predictive of Survival. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021; 216(6), 1566-1573. [CrossRef]

- Sung PS, Yang K, Bae SH, Oh JS, Chun HJ, Nam HC, et al. Reduction of Intrahepatic Tumour by Hepatic Arterial Infusion Chemotherapy Prolongs Survival in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(7), 3909-3916. [CrossRef]

- Lyu N, Kong Y, Pan T, Mu L, Li S, Liu Y, et al. Hepatic Arterial Infusion of Oxaliplatin, Fluorouracil, and Leucovorin in Hepatocellular Cancer with Extrahepatic Spread. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2019;30(3), 349-357. [CrossRef]

- Liang RB, Zhao Y, He MK, Wen DS, Bu XY, Huang YX, et al. Hepatic Arterial Infusion Chemotherapy of Oxaliplatin, Fluorouracil, and Leucovorin With or Without Sorafenib as Initial Treatment for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma.Front Oncol.2021; 11, 619461. [CrossRef]

- Shi J, Lai ECH, Li N, Guo WX, Xue J, Lau WY, et al. A new classification for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus.J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 201;18(1), 74-80. [CrossRef]

- Liang HL, Huang JS, Lin YH, Lai KH, Yang CF, Pan HB. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma by placing a temporary catheter via the subclavian route. Acta Radiol. 2007;48(7), 734-740. [CrossRef]

- Lencioni R, Eric C H Lai, Nan Li, Guo WX, Xue J, Lau WY,et al.Objective response by mRECIST as a predictor and potential surrogate end-point of overall survival in advanced HCC.J Hepatol. 2017;66(6), 1166-1172.

- Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al.

- Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359, 378–390.

- Quirk M, Kim YH, Saab S, Lee EW. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein thrombosis. World JGastroenterol.2015; 21, 3462–3471. [CrossRef]

- Kudo M. Changing the Treatment Paradigm for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Using Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab Combination Therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(21), 5475. [CrossRef]

- Liu BJ, Gao S, Zhu X, Guo JH, Kou FX, Liu SX, et al.Combination Therapy of Chemoembolization and Hepatic Arterial Infusion Chemotherapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Portal Vein Tumor Thrombosis Compared with Chemoembolization Alone: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2021; 6670367. [CrossRef]

- Dong H, Jian Y, Wang M, Liu F, Zhang Q, Peng Z,et al. Hepatic artery intervention combined with immune-targeted therapy is superior to sequential therapy in BCLC-C hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023; 149(8), 5405-5416.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).