Introduction

We are now at a turning point in human history -- a point of inflection at which the sustainability of our environment and indeed of life as we have known it depends to a significant extent on our ability to fundamentally redesign and retool the industrial processes on which our global economies are based.

The industrial processes that have been the basis for the world economies for over two centuries have either evolved or have been intentionally designed as open systems in which raw material inputs are transformed into finished products and packaging outputs that are routinely discarded and become waste after use. These open-system industrial processes are premised on two environmental assumptions: First, unlimited supplies of inputs are assumed to be available from the natural environment to be transformed into various kinds of outputs. Second, the capacity of the environment to absorb both the intended outputs and the by-products of open-system production systems is also assumed to be unlimited.

However, accelerating global climate changes caused by industrial greenhouse gases and the growing presence of toxic contaminants in both ground water and oceans now make it clear that both of these assumptions are no longer tenable, that as a result the open-system designs of our current industrial processes are no longer sustainable, and that the basic approaches to organizing production and consumption that have prevailed since the beginning of the Industrial Age more than two centuries ago must now be fundamentally redesigned throughout the world's economies. To convert the world's economies to sustainable production and consumption processes, we must be willing today to fundamentally re-imagine how economic goods and services can be produced and used to assure that we will have both viable economies and sustainable environments tomorrow.

This paper proposes that re-tooling the world's industrial processes to become sustainable will require creating new generations of environmentally modular product and process architectures that can support closed-system, bi-directional, reverse-flow "Circular Economy" industrial processes (Geissdoerfer et al. 2017; Winanset al. 2017). To this end, we explain how environmentally modular product and process architectures are essential to realizing the "Five R's" of sustainable industrial and economic systems:

• Reduce material and energy inputs;

• Recover more material and energy from industrial and consumer processes;

• Re-use products, components, parts, and materials;

• Repurpose used components, parts, and materials;

• Recycle materials that cannot be re-used or repurposed.

This paper elaborates the essential -- but as yet not well understood -- role that environmentally modular product and process architectures must play in enabling the kinds of closed-system, bi-directional industrial processes on which Circular Economies will be based in our future -- if we are to have one.

We develop our discussion in the following way:

First, we explicate the essential features of the Circular Economy, and elaborate how closed-system, bi-directional industrial processes that will be the basis for the Circular Economies of the future differ technologically from the open-system, one-directional processes that have been the basis for the world's economies since the Industrial Revolution.

We then explain the general concept of modularity and elaborate the concept of environmental modularity in product and process architectures in particular. We explain how environmentally modular product architectures are an essential enabler of the reverse-flow Circular Economy industrial processes in which the products, components, parts, and materials of environmentally modular products flow in both directions of the Circular Economy's industrial processes.

We then consider the "new rules and new roles" (Sanchez 2000) that must be understood and adhered to in designing, developing, producing, and recovering environmentally modular products.

We also summarize the five forms of entrepreneurial action that can be taken by individual firms, collaborations of firms, individual entrepreneurs, governments, and consumers to put in place the reverse-flow processes for recovering, re-using, repurposing and recycling that are at the heart of sustainable Circular Economy industrial processes.

The Circular Economy Movement

Most governments and much of the general public have come to understand that ongoing climate changes may soon result in far-reaching disruptions of our current economic systems, with corresponding unprecedented disruptions of most other aspects of human life globally. These concerns have fueled growing demands for fundamental re-thinking and re-design of all economic activities whose processes and products contribute to climate change (Geisendorf and Pietrulla 2018).

On the supply side, environmental concerns encompass all forms of production whose primary, upstream, or downstream activities consume materials and energy that result in carbon-based or other emissions that contribute to the atmospheric greenhouse effects that are now recognized as a primary cause of ongoing climate change, or whose products or production processes are sources of toxic contaminants. Proposals for reducing, recovering, re-using, repurposing, and/or recycling materials (and associated energy consumption) are now being developed in virtually every industry (Morseletto 2020), from primary products like concrete (Marshet al. 2022) to all kinds of manufactured goods (Lieder and Rashid 2016).

On the demand side, environmental concerns extend to ways for reducing consumers' consumption of products and services that will result in reduced carbon-based and other emissions, and to establishing "reverse flow" processes for recovering products from consumers and users at the end of the products' service lifetimes.

What is needed globally with increasing urgency is for virtually all industrial activities to be re-designed from the ground up to radically reduce the materials and energy currently consumed in producing products and thereby to limit environmental degradation. Thus, a basic objective for sustainability in creating new, environmentally benign product designs is to reduce the materials and energy required to produce and use those products. Beyond that basic design objective, however, the most consequential initiatives for improving sustainability envision putting in place "reverse-flow" processes for recovering products, components, parts, materials, by-products, and wastes in all forms so that they can be reused, repurposed, and/or recycled.

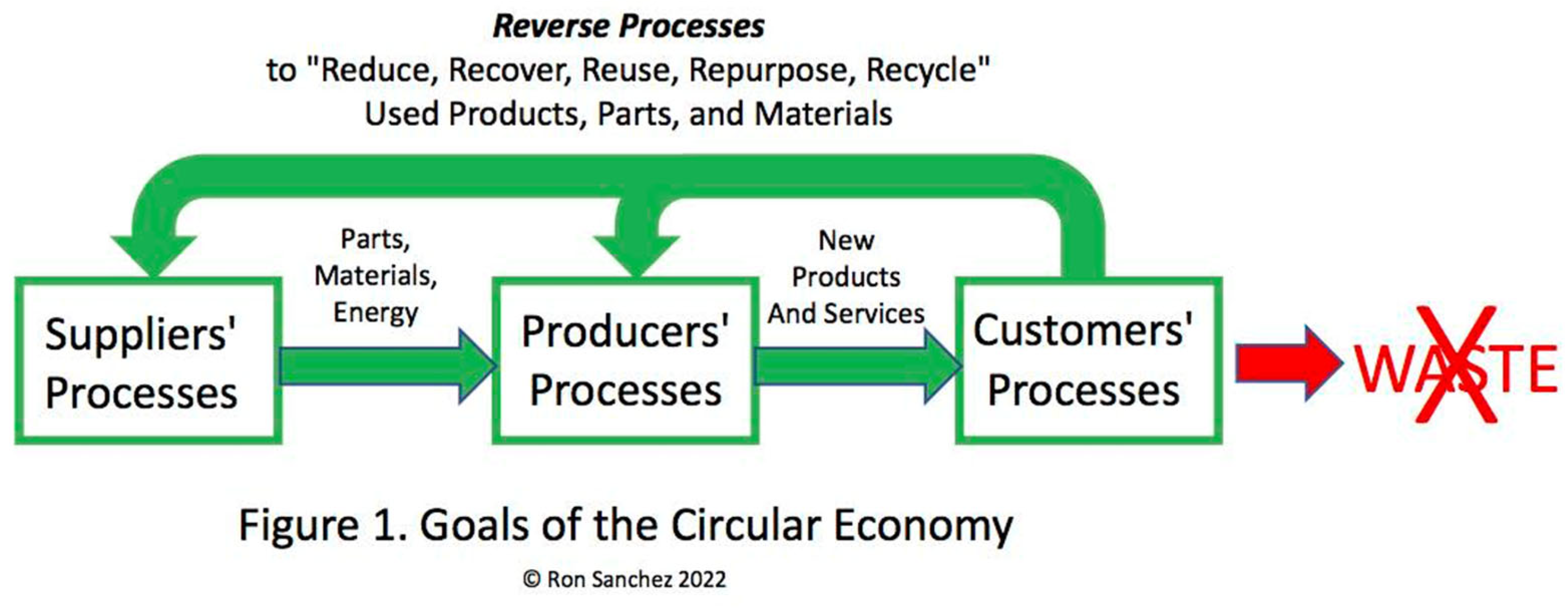

In essence, new generations of products and supporting production processes must now, to the maximum extent possible, be co-designed to support reverse-flow processes that make it possible to Reduce, Recover, Re-use, Repurpose, and Recycle all forms of materials and energy used in producing goods and services -- and thereby eliminate waste of materials and energy to the maximum extent possible, as suggested in

Figure 1. Hence the notion of a Circular Economy in which goods flow in both directions between producers and consumers -- new products and services from producers to consumers, and recovered used products, components, parts, and materials from consumers to producers and suppliers.

As we suggest below, to create a Circular Economy, most firms will have to re-design their business infrastructures, production processes, and business models to reduce the carbon footprints

1 and toxic wastes of their industrial processes and to create new product and process architectures that will enable reverse-flow processes for systematically reducing, recovering, re-using, repurposing, and recycling products, components, parts, and materials.

The Circular Economy in Theory

The theoretical basis for the Circular Economy begins with the simple notion that businesses should incorporate into all their decision processes full consideration of the environmental impacts as well as the direct economic costs of their products and processes.

In fundamental respects, this idea is not new. Both economic theory and environmental science have long recognized that any productive activity is likely to have significant negative externalities -- i.e., harmful byproducts or outcomes of the activities of an enterprise whose costs and/or consequences are not borne by the enterprise directly, but are passed on to the physical and social environment in various forms. Environmental negative externalities most notably consist of various forms of air, water, and ground pollution, while social negative externalities include harmful effects to workers in a firm's processes and to consumers and users of a firm's products (Lazăr 2018).

The traditional approach to limiting the harm that externalities cause to the environment and society has been for governments to regulate business activities to limit the negative externalities firms are allowed to generate. What is new in the Circular Economy movement is the idea that it is in the strategic long-term interest of businesses for firms to recognize and "take ownership" of the negative externalities that their business processes and products generate, and to develop strategies for minimizing the negative externalities the firm's products and processes may create in their physical and social environments. In essence, firms are now being asked -- and increasingly expected by consumers or required by governments -- to minimize and wherever possible to eliminate the environmentally and socially harmful externalities that their products and production processes generate.

The expectation that firms will now make serious commitments and take substantive actions to minimize the negative externalities of their operations is an integral part of the broad movement for greater

corporate environmental and social responsibility or "CESR" (Kakabadse, Rozuel, and Lee-Davis 2005), for companies to adopt and adhere to the United Nations' statement of Sustainable Development Goals (Georgeson and Maslin 2018), for regular "triple bottom line" reporting of a firm's environmental, social, and economic performance

2, and for numerous other initiatives intended to create sustainable production and consumption processes as the basis for the world's economic systems.

Some firms and industries have already begun serious efforts to limit the negative externalities of their processes and products. In so doing, more than a few firms have realized that the new kinds of closed-system bi-directional business processes envisioned by the Circular Economy may not only reduce a firm's negative externalities, but may also create positive externalities in the form of new kinds of economic efficiencies and new kinds of business opportunities that can bring substantial direct benefits to a firm and its industrial ecosystem of collaborating firms (Lazar 2018).

To achieve the full potential benefits of the Circular Economy, firms are likely to have to re-invent their business models and re-design their products and processes, in many cases from the ground up. However, as we suggest below, some of the essential changes in business processes needed to create the Circular Economy are scalable and can be implemented incrementally in making the transition from current business models, in which all materials and processes flow in only one direction, to new Circular Economy business models, in which reverse flow processes for recovering a firm's products, components, parts, and materials for re-use, re-purposing, and/or recycling become foundational processes of the firm.

The Circular Economy in Practice

In practical terms, the Circular Economy is enabled by five core processes: Reduce, Recover, Re-use, Repurpose, Recycle. Each of these core processes is summarized below

Reduce

The

Reduce objective in the Circular Economy asks firms to start looking at their operations

holistically and systemically -- up and down the supply chain -- to find ways to minimize the materials used and the energy consumed in the firm's own processes, in its suppliers' processes, and in its customers' uses of its products.

3

In competitive markets, it has long been imperative that firms be relentless in looking for ways to reduce costs (without sacrificing quality) through continuous improvement of their products and processes (Bhuiyan and Baghel 2005). What is new in the Circular Economy movement is that the drive to Reduce should apply not just to the economic costs that a firm bears directly in its operations, but equally to the negative externalities generated by a firm's processes, its suppliers' processes, and its customers' use of its products.

This substantial expansion of the scope of a firm's economic and environmental concerns may appear challenging, but as many firms have realized as they look more widely at the overall "value chain" of their processes (Porter 1980), many of the steps a firm may take to reduce the environmental negative externalities generated within its value chain may also reveal previously unrecognized opportunities for a firm to reduce the economic costs that it bears directly. For example, changing from energy-intensive materials made from non-renewable resources to less energy-intensive materials made from renewable or recycled resources may not only reduce the carbon footprint of a firm's materials inputs, but may also result in significant overall materials costs savings (Ogbudinkpa 1978).

In the important case of manufactured products, Reduce includes value engineering optimization methods now widely used in many industries to determine the most cost-effective materials and energy consuming processes required to assure desired performance levels in a firm's products. Similar optimization methods can be used to identify the least amount of materials and energy consumption needed to minimize the carbon footprint that alternative kinds and quantities of materials and energy used throughout a firm's supply chain will generate.

Recover

In most industrial processes, the key to achieving significant reductions in both negative environmental externalities and direct economic costs alike is putting in place new kinds of reverse processes for recovering and processing the firm's products, components, parts, and materials.

Business models now prevalent in the paper, aluminum can, and plastic packaging industries, for example, are now based on using from 50% to 90% recycled materials in their new products. Recycling of paper products has greatly reduced the levels of harmful effluents from pulping processes in the paper industry, while also lowering overall energy and material costs incurred in papermaking processes (Ozola, Vesere, Kalnins, and Blumberga 2019). Similarly, putting in place Circular Economy reverse-flow processes for recovering and recycling aluminum cans and plastic bottles has greatly reduced both the carbon footprints of those products and the materials costs of firms making those products (Ogbudinka 1978).

Moreover, joint economic and environmental cost analyses may reveal, for example, that the physically shortest supply chain may actually be the least costly one -- when both direct costs to the firm and externality costs the environment are considered. Similarly, in the closed-system solutions that the Circular Economy envisions, putting in place reverse processes for recovering, refurbishing, and/or recycling used products, components, parts, and materials may prove to be the least costly materials supply solutions, both economically and environmentally.

Re-Use

The Re-use goal in the Circular Economy refers to reverse processes in which a firm recovers its used products, components, parts, and/or materials from consumers so they can be refurbished and/or upgraded and then returned to the market for re-use -- thereby avoiding the consumption of more materials and energy to produce a wholly new product or component and avoiding the creation of more carbon emissions inherent in producing and processing new materials. An example of reverse-flow processes for re-use in place today is the large-scale recovery and re-manufacture of many automotive components.

In some cases, earlier generation products whose performance is no longer competitive in their original markets may be recovered and refurbished for re-use and re-sale in second-tier markets where their performance levels are still acceptable. For example, many kinds of earlier-generation computers, tablets, and smart phones that are no longer competitive in advanced economies may still be suitable for re-sale for commercial and/or educational uses in developing economies.

Repurpose

Some recoverable products may be amenable to modification so that they can be put to new kinds of uses different from the ones they were originally intended to serve. Some components and parts from complex products like automobiles, appliances, and digital devices may find second and even third lives in other product applications. For example, transistors, capacitors, and other basic electronic components that have been salvaged from used televisions and other appliances can often be used in the circuits that power fluorescent and LED light fixtures. Much repurposing is also possible at the materials level, when materials originally used in one product can be recovered and used in a new product application. Used automotive and truck tires, for example, are now being shredded for use as additions to asphalt highway paving.

Recycle

The Recycle goal in the Circular Economy refers to recovering and dismantling used products to recover energy-intensive materials like steel, iron, non-ferrous metals, glass, and plastics that can then be recycled in the production of new batches of the materials. Recovered primary materials may be reused by the recovering firm itself or sold into recycled materials commodity markets. Recovering materials from used products may substantially reduce the levels of energy consumption and resulting carbon-emissions usually involved in transforming non-renewable resources like ores and petroleum into usable finished materials.

An Ecosystem Perspective on Industrial Processes: Open-Systems Versus Closed-Systems

Firms in the developed economies of the world today commonly depend on both global supply chains to supply their inputs and on globally distributed markets to absorb their outputs. Increasingly, the structures and processes of economic systems in use today resemble industrial ecosystems populated by potentially large numbers of firms with specialized supply, production, distribution, and support capabilities (Adner and Kapoor 2010).

Like any system, an industrial ecosystem of interacting firms may function as an open system or a closed system (Sanchez, Galvin, and Bach 2024). Open-system industrial ecosystems are premised on the presumptions (i) that supplies of input materials are always available and may readily be obtained from multiple sources, (ii) that the "market" that the firm serves can absorb participating firms' outputs, and (iii) that participating firms' physical and social environment will be able to absorb the negative externalities that the firms' industrial processes generate.

By contrast, a pure closed-system industrial ecosystem would require no new inputs beyond those already in the system, would produce outputs that will be retained within the system, and would produce no negative externalities. As a rule, however, it is not possible for any production system to operate without some ongoing inputs of energy and new materials, nor is it possible to completely insulate an economic system from its physical and social environment. In practice, any industrial system can only function as a closed system to a certain degree. The goal of the Circular Economy is therefore to create industrial systems that function to the greatest extent possible as closed systems with minimized inputs of new materials and energy.

In a Circular Economy, substantially closed-system industrial processes have bi-directional flows of new products, components, parts, and materials from producers to consumers coupled with reverse flows in which used products, components, and materials flow back from consumers to producers, creating a largely closed-system economic process. Reverse flows of used products, components, parts, and materials enable their recovery and further processing for reuse, repurposing, and/or recycling. Creating sustainable circular economies founded on substantially closed-system industrial processes will therefore require developing new, ground-up designs not just for products, but also for the myriad industrial processes used to produce, distribute, deliver, service, and support new kinds of products specifically designed to be efficiently recoverable for re-use, re-purposing, and/or recycling.

Product and Process Architectures in Industrial Ecosystems

Any industrial ecosystem is fundamentally based on both the architecture(s) of the products the ecosystem produces and architecture(s) of the processes carried out by participating firms within the ecosystem to produce, service, distribute, maintain, and recover their products. When the architectures of the products the ecosystem produces and the architectures of the production and support processes for the ecosystem's products are coordinated together, they form an industry architecture that defines how various participants in the industrial system will provide production, distribution, and support services that "plug and play" (i.e., are technically compatible) with the way other participants perform their functions in producing the ecosystem's products (Sanchez and Collins 2001; Sanchez, Galvin, and Bach 2024).

An architecture is a two-part concept that formally defines how the design of a product, of a process, of an organization, of an industry, or any other kind of functional entity is structured. An architecture defines (i) the way the overall functionality of a design has been decomposed into specific kinds of functional components, and (ii) the interfaces that will determine how the functional components will interact with each other and with the environment when the components function together as a system (Sanchez 2013).

Traditionally, defining the interfaces in an architecture has required the full specification of eight kinds of component interfaces (Sanchez 1999, 2013):

(i) Attachment Interfaces: How components will physically attach to each other;

(ii) Spatial Interface: The physical space a component will occupy in an overall product design;

(iii) Transformation Interfaces: The input(s) that each component will transform into specific output(s) in performing its function(s) in the design;

(iv) Communication and Control Interfaces: How a component communicates with and controls and/or is controlled by other components in the design;

(v) User Interfaces: How each component in the design will interact (directly or indirectly) with the users of the design (ergonomics or "human factors");

(vi) User's Infrastructure Interfaces: How each component will connect with the intended user's infrastructure (available electricity, batteries, fuels, lubricants, repair and maintenance services, etc.);

(vii) External Ambient Interfaces: How a component will interact with the intended ambient environment for use of a product (heat, cold, vibration, dust, radiation, gravitational forces, etc.);

(viii) Internal Ambient Interfaces: How the functioning of one component in the design may affect the functioning of other components in the design (heat transmission, vibration, electromagnetic forces, etc.).

More recently, in recognition of the need to design products and processes in the context of Circular Economies, a ninth interface has become essential in the design of product and process architectures for the Circular Economy -- and is hereby introduced in this paper:

(ix) Environmental Interfaces: How a component will interact with available or potential reverse-flow industry processes for recovering, re-using, repurposing, and/or recycling products, components, parts, and materials.

The Environmental Interface is discussed more fully below under the heading of Modular Environmental Interfaces.

Modular Product and Process Architectures

Beginning in the 1990s, growing numbers of firms began to transform the nature of competition in many industries by using modular product designs and flexible production processes to enable the fast, low-cost configuration and production of large numbers of product variations and upgrades (Sanchez 1995, 1999). As this discussion undertakes to show below, while the usual competitive strategy benefits of modular product and process designs may still obtain in product markets, modular product and process architectures -- sometimes referred to as an industrial ecosystem's modular platform -- provide the essential design framework for creating new kinds of products and processes that can achieve the substantially closed-system, bi-directional industrial processes on which Circular Economies will depend (Vettorato and Hsuan 2015).

Modularity is a design methodology for creating coordinated product and process architectures that are intended to accomplish one or more strategic objectives. As illustrated in

Figure 2, the interfaces in a

modular product architecture are defined to allow the free substitution of a range of variations in the components in a product design to configure a range of product variations without having to change the designs of any other components in the product architecture.

Similarly, modular process designs for production, distribution, service, and support processes are designed to allow different process variations (for example, services provided by different suppliers) to readily "plug and play" in the various processes of the ecosystem's modular process architecture. Taken together, the strategic flexibility of a modular industry architecture enables the creation of an industrial ecosystem in which firms can readily participate as long as their product components and/or process activities conform to the interface specifications of the modular industry architecture (Sanchez, Galvin, and Bach 2024). In effect, the interface specifications for product components and process activities in a modular industry architecture constitute an information structure that informs participants in an industrial ecosystem how their product components and activities have to connect with other participants' components and activities in order to participate in the industrial processes enabled by the modular industry architecture (Sanchez and Mahoney 1996; Sanchez 2008).

In order for both the forward and reverse processes of a Circular Economy to work efficiently, the participants in an industry must be able to identify and appropriately process the products, components, parts, and materials moving through the industry ecosystem in both directions. As suggested by the "Interactions of modular product and process architectures" in

Figure 2, creating new Circular Economy ecosystems will require putting in place both forward and reverse processes that can recognize, operate on, and support each of the products, components, parts, and materials that move through an industry ecosystem in both directions.

An important organizational and managerial aspect of this retooling of product and process architectures for the Circular Economy is what is widely referred to as the mirroring hypothesis in modularity theory (Sanchez and Mahoney 1996; Colfer and Baldwin 2016). Widely researched and broadly supported, the mirroring hypothesis holds that efficient functional and technical structures of organizations will reflect the functional and technical structures of the products they design and produce. In the current context, the mirroring hypothesis implies that converting from open-system, one-directional product and production systems to modular closed-system, bi-directional products and processes will require redesigning firms' organization structures and management processes to directly manage and support the implementation of the new kinds of reverse flow processes required in closed system, bi-directional industry architectures.

Environmental Modularity

Modular approaches to designing coordinated product and process architectures are now understood to enable transformational "quantum jumps" in firms' abilities to create new products and processes much more quickly and efficiently than traditional design methods are capable of doing (Sanchez and Collins 2000; Sanchez 2004). Thus far, modular designs and development processes have been viewed largely as a tool whose inherently greater speed and lower costs can enable businesses that develop modularity competences to pursue new kinds of competitive strategies and obtain new kinds of competitive advantages in their markets (Sanchez 2008). However, as we undertake to make clear below, modular design methodology has a pivotal role to play in creating the competences needed to create the bi-directional processes and achieve the closed-system goals envisioned for the Circular Economy.

We now adopt the term environmental modularization to refer to the process of defining and developing modular product and process architectures with Environmental Interfaces intended to enable the Reduce, Recover, Re-use, Repurpose, and Recycle goals of a Circular Economy.

Environmental Modularization of Product Architectures in the Circular Economy

Modular product development processes have certain general requirements -- what are often referred to as "new rules and new roles" (Sanchez 2000) -- that differ radically from traditional, non-modular development processes, but that are also essential to the creation of environmentally modular products and processes.

The first step in developing any modular architecture is the full specification of the interfaces between components that will enable the components to function together as a system in their use context. To be modular, the interfaces in an architecture must be specified to allow the ready substitution of a range of product component variations and process activity variations into the product and process architectures without having to make compensating changes in the designs of the other components and activities in the architectures (Garud and Kumaraswamy 1995; Sanchez 1995). In addition, the interfaces between product components and process activities must be standardized (fully specified and then frozen) to create a stable technical environment in which a defined range of modular product component and process activity variations can be freely introduced into their respective architectures.

What makes modular product and process architectures environmentally modular is that the interfaces for each of their respective components have been specified to support the Reduce, Recover, Re-use, Repurpose, and Recycle goals and supporting bi-directional processes of the Circular Economy.

We now summarize how environmental modularization can be used to support each of the five sustainability goals for the Circular Economy.

Reduce Through Environmental Modularization

A fundamental principle of modular design is the disciplined re-use of existing component designs in developing next-generation products. The modularity principle of disciplined re-use requires that already existing component designs must be re-used in next-generation product designs -- unless a convincing case can be made to justify creating a new component design for a next-generation product.

The mandatory component re-use rule in modular development processes stands in stark contrast to the widespread problem of uncontrolled "parts proliferation" in many, if not most, manufacturing firms around the world. When firms do not follow a strict policy of disciplined re-use of existing component designs, designers and developers tend to see each new product development project as an opportunity to create new component designs -- even though existing component designs are often adequate for re-use in next-generation products. The result is that many firms routinely develop far more component and parts variations than they actually need to meet their product variety requirements. Thus, adopting modularity's disciplined re-use of existing component designs can substantially reduce the economic and environmental waste many firms generate by developing, producing, inventorying, and supporting unnecessary new component designs for new products.

In addition, systematically adhering to modularity's re-use principle in creating environmentally modular products would also reduce the materials and energy that would otherwise be used in re-tooling production processes to produce unnecessary new components and parts and by reducing warehousing costs when fewer component and parts variations need to be inventoried to support new products.

The modularity design principle of disciplined re-use can be further extended by adopting the practice of designing new components to be re-usable in future-generations of new products ("design for re-use") and when components are designed to be used in common across product variations ("design for commonality"). When components and parts variety can be reduced because components and parts have been designed to be re-used in subsequent product generations or used in common across current product variations, both the direct economic costs and negative environmental externalities involved in developing, producing, and inventorying components and parts can be reduced, often quite substantially. Case studies have documented that modular design strategies for greater re-use and commonality of components can reduce direct product costs by 50% or more (Sanchez 2004) -- with comparable reductions of environmental waste and associated negative externalities as well.

Recovery Through Environmental Modularization

The most basic requirement for establishing reverse processes for efficient recovery of used products, components, parts, and material is an ability to identify exactly what product, component, part, or material is being recovered by a reverse-flow process. Although stamping of some recyclable commodity materials with identifying information is now becoming more common (especially when reference is made to ASTM, SAE, DIN, or other standard material specifications), recovery of more complex parts or products is often frustrated by an inability to readily identify the materials used in recovered products, components, and parts.

A basic requirement of modular architectures is that their component interfaces are fully defined. Moreover, any new component variations introduced into a modular product architecture after initial development are also constrained to conform to the original interface specifications for that kind of component in the architecture. Thus, the interface specifications for components (and parts within components) in an environmentally modular product architecture require that the material compositions of all parts and packaging have been clearly indicated on each part or packaging element using commonly understood material names or by reference to various accessible materials standards like ASTM, DIN, JAS, etc.

Environmentally modular product architectures thereby create an essential environmental information structure for identifying each kind of component and part that can be recovered for re-use or re-purposing and each kind of material that can be recovered for recycling through the reverse flow processes of a Circular Economy.

Re-Use Through Environmental Modularization

Modular product designs have traditionally been used to increase product variety by enabling the substitution of component variations in an architecture to configure new product variations. To enable the recovery and re-use of components and parts through the reverse flows in a Circular Economy, however, the strategic objectives for a modular product architecture can be reprioritized to create product architectures with "service and repair modularity" in which components and parts that are subject to wear, failure, or obsolescence can readily be removed from a product and new components or parts installed in their place. The replaced components and parts can then be recovered through reverse-flow processes for remanufacturing, refurbishment, repair, or in the case of obsolescent components, for re-use in less demanding applications.

The use of modular designs to enable efficient replacement and refurbishing of worn-out or obsolete components and parts is already happening in the automotive, aeronautical, electronics, and other industries in which products have long commercial lifetimes and thus need periodic replacement or upgrading of key components or parts. However, modular design for re-use has not yet become common in "high velocity" markets in which current-generation products like smart phones are frequently just thrown away when replaced by new generation products. This prevalence of throw-away products is inherently wasteful economically and often leads to serious problems of environmental pollution.

The alternative environmental modularization approach is to explicitly design products as modular platforms in which key components can be readily upgraded, so that the performance of a user's current product can be upgraded periodically in the future (Sanchez 1999). This form of environmental modularity-enabled quick replacement is now being used in electric vehicles to facilitate future replacements of original vehicle batteries by next-generation batteries that benefit from the rapidly increasing energy density and falling costs of production for batteries for electric vehicles. New generation Tesla electric cars, for example, are being designed so that expected future-generation batteries with greater energy capacity (and thus extended cruising range) can be readily substituted into an older Tesla vehicle as future-generation batteries become available.

4

Repurposing Through Environmental Modularization

Some products, components, and parts can be adapted after their intended lifetime of use in their targeted market to work in a range of applications that are different from their originally intended use, often in the context of second- and third-tier economies.

For example, power trains from small European cars are regularly being repurposed to meet all kinds of needs for mechanical power in Africa and other less economically developed areas of the world. Currently, small-displacement power trains are "extracted" from end-of-life used cars in Germany for shipment to Africa, where they are used to drive water pumps, elevators, air conditioners, and other devices. Because power trains in German cars (even small ones) are not designed for easy removal (although they could be), the extraction process consists of massive mechanical jaws that clamp on the engine block and basically just rip the engine and transmission out of the car. That process sometimes causes damage to power trains that renders them inoperable, creating economic and environmental waste. By contrast, if recovery and repurposing of used automobile powertrains were made an objective for environmentally modular designs of power trains in at least some German cars, the vehicle architectures could be modified to enable faster and safer removal of power trains for recovery, re-use, and repurposing.

In effect, purposeful modular design for re-use of products, components, and parts in other markets and/or for repurposing in alternative applications could significantly broaden the economic attractiveness and scope of reverse-flow processes in the Circular Economy. Analyzing investments in creating new product architectures to consider possible economic returns from markets for re-use and repurposing of a product, component, or part may reveal that it is both economically profitable as well as more environmentally sustainable to "design in" ways of making it easier to re-use and repurpose an environmentally modular product, component, or part.

Environmental Modularization for Recycling

The objective of environmental modularization for recycling is to create modular product designs with parts that can be quickly disassembled and separated into individual materials for recycling after the useful lifetime of a product has come to an end.

Environmental modularization intended to facilitate recycling works on three principles:

(1) All materials used in a product must be amenable to re-use, repurposing, or recycling in the same or other known product application. For example, some PVC and PET plastics can be readily reprocessed and used multiple times in their original product applications (Welle 2011). Other plastics, however, cannot be chemically reprocessed to perform acceptably in their original form, but they can be mechanically processed into pieces that can be used as "fillers" in various other kinds of molded plastic products.

(2) As noted above, all materials must be clearly labeled to identify the exact nature of the material used in each part to enable fast, reliable sorting of materials in recovery and recycling processes.

(3) The physical connections between parts and components in an overall product design should be capable of being disconnected as quickly as possible when the time comes to retire, recover, and disassemble the product to recycle its materials.

Environmental modularization in support of Recycling is therefore importantly concerned with "strategically partitioning" the product architecture so that all materials and parts composed of materials can be physically separated as efficiently as possible, preferably using automated machine processes or, when necessary, simple tools for human disassembly. For example, when the German government announced that it would begin to require all manufacturers of automobiles in Germany to be ultimately responsible for the recovery and recycling of all the automobiles they produce in Germany, BMW launched a program to environmentally modularize the architectures of their vehicles so that many components and parts in their vehicles could be disassembled in short order into separate recyclable materials -- while of course still maintaining the highest level of "build quality" for the useful lifetime of the vehicle.

Environmental Modularization of Process Architectures in the Circular Economy

While most awareness and discussion of modularization to date has focused on creating modular product architectures, capturing the full "power of modularity" requires the creation of modular platforms (Sanchez 2004) that consist of modular product and process architectures that have been coordinated to create a systemic capability to rapidly configure and produce new products as market conditions and demands evolve. The introduction of batch manufacturing methods based on work cells and of assembly lines using robotics and other programmable process equipment have greatly facilitated the creation and use of flexible modular process architectures for production of many kinds of manufactured goods.

The key contribution to the Circular Economy of environmental modularization in flexible, reconfigurable production processes is to reduce or eliminate the number of often rapidly obsolescing single-purpose machines and dedicated production lines needed to produce a changing array of products to meet evolving market demands. When one or a few flexible modular processes can do a range of jobs or operate under a range of conditions that otherwise would require multiple single-use machines or dedicated production lines, the total amount of materials used and energy consumed in a firm's overall production processes may be reduced, often significantly.

New Environmental Entrepreneurial Roles in Circular Economy Ecosystems

The use of environmental modularization to create and process products in pursuit of the Reduce, Recover, Re-use, Repurpose, and Recycle goals of the Circular Economy may take place in five ways in an economy, each of which forms an arena for specific kinds of entrepreneurial action:

(i) implementation of environmental modularity initiatives within individual firms;

(ii) implementations of collaborative environmental modularity initiatives by cooperating firms within or across industries;

(iii) initiatives by individual entrepreneurs seeking to overcome and profit from market failures;

(iv) interventions by governments to support or mandate the use of environmental modularization and the establishment of essential reverse processes for recovering products, components, parts, and materials.

(v) Grassroots consumers movements to overcome failures of the four forms of entrepreneurial action above

Implementations by Individual Firms

Firm that design and produce products may face increasingly significant incentives to use environmental modularity to reduce the materials and energy consumed in producing its products, to increase the recoverability of its products from users and consumers, and to design in greater re-usability, repurposing, and/or recyclability of its products.

To take advantage of environmentally modular designs that support recovery, re-use, repurposing, and/or recycling, firms will very often have to convert their managers' mindsets from linear business models based on transactional "one-time, one-way" sales of products, and instead adopt much more relational Circular Economy business models in which environmentally modular product designs become the enabler of long-term interactive relationships with customers in maintaining and extending the useful lifetimes of the firm's products (Sanchez 1999).

Such transformations of businesses models are already underway in some companies in the advanced economies globally, often stimulated by the increasing importance of revenues from after-sales upgrading, service, and support activities in many industries. Moreover, the increasing importance of service level agreements and pay-by-use revenue models create significant new financial incentives for firms to use environmental modularization to facilitate recovery, re-use, repurposing and recycling.

5

The environmental modularization of product designs intended to facilitate recovery, re-use, repurposing, and recycling must be complemented by firms' efforts to establish infrastructure to support reverse processes for recovering products, components, parts, and materials from its customers. If the size, shape, weight, and value of a component permit, existing postal and package shipping services may provide an efficient infrastructure for reverse processes for recovering products, components, and parts. Environmental modularization may also be used to create product designs in which users themselves or available service providers are able to remove and then re-install just the parts or components that need to be returned to the producer for repair, refurbishment, or upgrading. Canon's repartitioning of its personal copier architecture to combine all components needing regular replacement into one easy-to-remove cartridge is a classic case in point (Yamanouchi 1989). In the case of larger and heavier products and components, more specialized logistics services will may have to be created to support reverse-flow processes.

Overall, however, the strategic emphasis on developing interactive, long-term relationships with suppliers and customers now prevalent in many industry ecosystems, coupled with the growing prevalence of modular product designs, often create significant new incentives for firms to broadly engage their customers and users through bi-directional, reverse-flow processes that lie at the heart of the Circular Economy.

Firms whose products are not technologically or economically amenable to repair or upgrading for re-use may nevertheless use environmental modularization to enable fast and easy disassembly of their products into parts whose materials can be recycled. If a firm's scale of operations is sufficiently large and if its user base is not too widely dispersed, recovering parts for recycling may be as simple as having its current delivery system for its new products begin to pick up used products, components, and parts for return to the producer. This simple reverse-process solution, for example, is now widely used in the automotive parts industry, in which vehicles that deliver new and remanufactured parts to automobile service providers also recover used components that are then returned to their original manufacturers for refurbishing and/or recycling. Similarly, supermarkets in the Nordic countries now deliver many food products in collapsible or stackable plastic crates that can be picked up and returned for re-use, thereby eliminating the need for paper packaging.

Implementations by Cooperating Firms Within or Across Industries

The requirements for implementing new kinds of reverse-flow processes for recovering products from markets will depend to a large extent on the technical nature of an industry's products, the scale of individual firms' production, and the geographic reach of its products' distribution. In cases where it is economically prohibitive for individual firms to create their own reverse-flow processes, firms may find it advantageous to cooperate with other firms in creating joint, industry-level processes for reverse flows. Defining industry standards for components, parts, and materials may then be necessary to create sufficient scale to make reverse-flow processes for recovery economically feasible.

Similarly, industry-level agreements to standardize certain kinds of materials used in the industry's products and/or packaging may create sufficient scale in those materials to make it economically feasible to put in place new reverse-flow processes for recovery and recycling of industry-standard materials.

Even when firms do not coordinate their product architectures to use more industry-standard components and materials, firms may still be able to lower costs of recovery by cooperating in sharing logistics processes at a scale sufficient to make it attractive for logistics service providers to establish specialized reverse-flow processes for recovering the industry's products, components, parts, and materials, as well as for third-party firms to provide refurbishment and recycling services.

Individual Entrepreneurial Initiatives

If individual firms or collaborations of firms fail to put in place the infrastructure needed to perform reverse-flow processes, individual entrepreneurs may see an opportunity to make a business out of providing reverse-flow services. There are at least two ways in which entrepreneurs may provide a solution to establishing Circular Economy processes that firms currently in an industry cannot or will not provide themselves: consolidating demand, and overcoming hesitation by competitors to cooperate.

In the first case, entrepreneurs may realize that reverse processes that are prohibitively costly for firms operating at small scale to carry out on their own may become more cost efficient and thus economically feasible when carried out at larger scale. By consolidating demand for and increasing the scale of reverse-flow processes offered to an adequate number of smaller firms, an entrepreneur may be able to offer recovery, re-use, repurposing, and recycling services at costs that are below those that smaller firms would have to pay individually -- while still earning a profit for the entrepreneur.

In the second case, if firms in an industry lack a history of cooperation with each other or are very competitive in their attitudes towards other firms in their industry, entrepreneurs may realize that there can be a profitable business opportunity in providing the market mediation needed to consolidate reverse flows of products, components, parts, and materials that the competing firms in the industry are unwilling to cooperate to achieve.

Government Interventions

The formation of new market demand and new processes to serve new kinds of market demand usually poses a familiar "chicken and egg" problem: How to create enough demand for a new kind of good or service to stimulate private entrepreneurs to invest in creating the capabilities needed to supply and serve demand for the long term?

This problem is particularly challenging when it concerns opportunities to create a

new kind of public good6 -- in this case, a more sustainable environment by implementing the reverse processes of a Circular Economy -- that will require substantial investment in re-tooling current product designs, production processes, and business models.

While it is possible that some larger firms, collaborations of firms, or individual entrepreneurs will find solutions to establishing Circular Economy processes, it is commonly the case that governments that are seriously concerned about climate change may have to solve the chicken-and-egg problem in converting their economies from traditional one-way business processes to large-scale, closed-system, reverse-flow processes for recovering, re-using, repurposing, and recycling. As with other major economic and social transformations, governments may draw on a policy tool kit that includes both "carrots and sticks" -- positive and negative incentives -- to solve the chicken-and-egg challenges of new market formation in creating reverse-flow processes in the Circular Economy.

On the demand side, government can use positive incentives to stimulate demand by consumers for products and services that are compatible with the Circular Economy. Two examples are reducing VAT taxes on purchases of electric vehicles to encourage their adoption by consumers and creating refundable deposits on bottles to encourage their recovery and recycling. On the supply side, government may use positive incentives to encourage firms to make the investments needed to invest in infrastructure for reverse-flow processes. For example, government may provide grants to local governments or low-cost loans to entrepreneurs to help establish recycling centers.

Negative incentives available to governments include taxes or penalties that impose costs or regulatory requirements on consumers and firms that have the effect of encouraging both consumers and businesses to support products and processes that are consistent with the Circular Economy. Imposing taxes on non-electric automobiles -- as high as 180% of the price of the vehicle in Denmark, for example -- can be used to encourage people to use public transportation with lower carbon footprints. Government may also adopt laws and regulations that directly require businesses to put in place recycling processes for their products and packaging, as has been the case in some European Union countries for some time now.

Whether a given government will choose to use positive or negative incentives to stimulate and support the reverse-flow processes of the Circular Economy will depend on a multitude of factors that may be unique to each country or region. What is essential, however, is that governments recognize the need for policies and supporting incentives to establish the infrastructure of reverse-flow processes for Recovery, Re-use, Repurposing, and Recycling when "the market" fails to provide commercial solutions.

Grassroots Consumer Movements

If individual firms, collaborations of firms, entrepreneurs, or governments do not offer solutions to implementing reverse-flow Circular Economy processes, it is still possible that motivated groups of consumers and users may band together to create their own local reverse-flow processes. In many communities, for example, residents have started "free exchanges" where clothes, books, furniture, appliances, and other goods that they no longer want are donated to be taken for free by other residents who need them. Similar initiatives could be used to form collection points for local consolidation of re-usable products and recyclable materials, thereby favorably changing the economics of reverse-flow processes for re-use and recycling.