1. Introduction

Royal jelly is a yellowish, creamy, acidic secretion of the hypopharyngeal and mandibular glands of nurse bees and serve as food for honeybee larvae and the entire life of the honeybee queen. This precious substance is rich in biologically active compounds that make one of the most valuable natural products which has been mainly used in traditional medicine. A major part of royal jelly are water (60–70% w/w), proteins (9–18% w/w), sugars, (7–18% w/w) and lipids (3–8% w/w), and the minor components, such as minerals, amino acids, vitamins, enzymes, hormones, polyphenols, nucleotides [

1]. The key proteins of royal jelly are major royal jelly proteins (MRJPs), which belong to a large protein family, of nine members with molecular masses in the range of 49-87 kDa [

2,

3]. The most abundant royal jelly protein MRJP1 (also called apalbumin1) [

4], occupies an exclusive position because it is simultaneously synthesized in the honeybee brain [

5], as well as in the hypopharyngeal glands of adult honeybees [

6,

7]. It was found that MRJP1 plays an important role in larval development into a queen rather than into a working bee [

8] and is also responsible for many healing properties of royal jelly. Queens and working bees are genetically similar, and their phenotypical difference is determined by epigenetic mechanisms, such a methylation of the specific areas of the genome. MRJPs thus act as epigenetic modulators [

9].

Royal jelly has been demonstrated to possess a broad range of functional properties such as anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory properties, neuroprotective, vasodilatory, antidiabetic and hypotensive activities, anti-bacterial, anti-allergic, and anti-osteoporotic and antioxidant effects, anti-hypercholesterolaemic activity, and antitumor properties [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Ghorbanpour and colleagues [

16] reported that royal jelly induced pro-cognitive, anxiolytic, and antidepressant-like effects in laboratory rats exposed to stressors. Thus, royal jelly increased the novel object recognition scores and decreased the time spent in the open arms of the elevated plus maze apparatus. In the same study, it was reported that treatment with royal jelly attenuated the stress-induced increase in circulating glucocorticoid concentrations and decrease in levels of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF; a key neuroprotector and modulator of neuroplasticity) [

17].

It is well established that the corticolimbic serotonergic (5-HT), noradrenergic, and dopaminergic circuits play a fundamental role in memory, cognition, and mood regulation [

18]. These systems are also the key modulators of BDNF expression; monoamine-BDNF interaction is involved in the pathophysiology and treatment of depression, anxiety, and cognitive disorders [

17]. It is therefore likely that the pro-cognitive effects of the royal jelly and its specific component(s) are mediated, at least in part,

via mechanism(s) involving the alteration of the excitability of monoaminergic neurons. The primary goal of this study was to test this hypothesis.

Substantial portions of 5-HT, noradrenergic, and dopaminergic neurons projecting to the corticolimbic areas are located in the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN), locus coeruleus (LC), and ventral tegmental area (VTA), respectively. The generation of action potentials or spikes in the cell bodies of monoaminergic neurons within these three brain nuclei is likely to determine limbic monoaminergic transmission. With respect to monoaminergic neurotransmission, next to the overall firing rate, the mode of the spike generation is of crucial importance. The burst-like, or phasic mode of firing of monoaminergic neurons (e.g., generation of the cluster of spikes characterized by millisecond-range inter-spike interval, followed by a second-range period of silence) is more efficient in terms of neurotransmission than the tonic mode of activity, when the same number of action potentials are generated in a single-spike mode [

19]. To address these aspects of monoaminergic neurotransmission, we assessed the effect of the royal jelly on the firing rate, as well as on the burst activity of the neurons.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Royal Jelly Preparation

Fresh honeybee royal jelly was obtained from Japan Royal Jelly, Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan. Royal jelly suspension at a concentration of 200 mg/ml was prepared by mixing 10 g of fresh royal jelly in 25 ml of Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.5 (TBS), and filling up to 50 ml of total volume with TBS buffer. Suspension of royal jelly was frozen in 500 µl aliquots at -80 °C before experimental use.

2.2. Animals

Adult male Wistar rats, weighing 250-350 g, were ordered from the Animal Breeding facility of the Institute of Experimental Pharmacology and Toxicology, Centre for Experimental Medicine, Slovak Academy of Sciences (Dobra Voda, Slovakia). Animals were housed under standard laboratory conditions (temperature 22 ± 2°C, humidity: 55 %) with a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle (lights on at 6 a.m.). Pelleted food and tap water were available ad libitum. All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Health and Animal Welfare Division of the State Veterinary and Food Administration of the Slovak Republic (Permit number Ro 3592/15-221) and confirmed to the Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific Purposes.

2.2. Repeated Administration of the Royal Jelly

After the rats were allowed to acclimatize in the animal facility for seven days, they were randomly divided into two groups: royal jelly and vehicle (TBS). The number of animals per group (n=10/group in the novel object recognition: NOR experiments with the subsequent assessment of firing activity of 5-HT and dopaminergic neurons and n=5/group for the assessment of the firing activity of noradrenergic neurons) was determined by power analysis based on the results of our previous studies [

20,

21,

22]. The royal jelly TBS solution was administered

per os, at a dose of 200 mg/ml/kg, for fifteen consecutive days, once daily at 9 a.m.; control animals were administered vehicle.

2.3. NOR Test

The behavioral testing was performed one hour following the royal jelly or vehicle administration on the 14

th day of the chronic treatment. The NOR test was performed as previously described [

20,

21]. In short, each rat was allowed to explore two identical objects placed in a square-shaped arena (50 x 50 cm) for five minutes. Thereafter, the rat was put into a separate cage for three minutes while one of the familiar objects was replaced by a new one. Next exposure to the arena lasted five minutes, and the exploration time of each object was measured using a computer program. The results were expressed in the form of a recognition index that was calculated as the ratio of the time spent on exploration of the new object and the sum of the time spent on exploration of both the new and the old object × 100%.

2.4. In Vivo Electrophysiology

In vivo electrophysiological assessments were performed one hour following the royal jelly or vehicle administration on the 15

th day, as previously described [

22]. Animals were anesthetized by chloral hydrate (400 mg/kg, i.p.) and mounted in the stereotaxic frame (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). Body temperature was maintained between 36 and 37°C with a heating pad (Gaymor Instruments, Orchard Park, NY, USA). The scalp was opened, and a 3 mm hole was drilled in the skull for insertion of electrodes.

Glass pipettes were pulled with a DMZ-Universal Puller (Zeitz-Instruments GmbH, Martinsried, Germany) to a fine tip approximately 1 μm in diameter and filled with 2M NaCl solution. Electrode impedance ranged from 4 to 6 MΩ. The pipettes were inserted into the DRN (7.8-8.3 mm posterior to bregma and 4.5-7.0 mm ventral to brain surface), LC (8.0-8.3 mm posterior to bregma, 1.2-1.4 mm lateral to the midline, and 5.5-7.5 mm ventral to the brain surface), or VTA (4.5-5.5 mm posterior to bregma, 0.6-0.8 mm lateral to the midline, and 7.0-8.5 mm ventral to the brain surface) [

23] by hydraulic micro-positioner (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). The action potentials generated by monoamine-secreting neurons were recorded using the AD Instruments Extracellular Recording System (Dunedin, New Zealand). After completion of the electrophysiological recordings, the animals were euthanized by overdose of chloralhydrate.

The 5-HT neurons were identified by bi- or tri-phasic action potentials with a rising phase of long duration (0.8–1.2 ms) and regular firing rate of 0.5–5.0 Hz [

22]. Noradrenergic LC neurons were recognized by action potentials with a long-duration rising phase (0.8-1.2 ms), regular firing rate of 0.5–5.0 Hz, and a characteristic burst discharge in response to nociceptive pinch of the contralateral hind paw [

24]. Dopaminergic neurons were recognized by tri-phasic action potentials lasting between 3 and 5 ms with a rising phase lasting over 1.1 ms, inflection or “notch” during the rising phase, marked negative deflection, irregular firing-rate of 0.5-10 Hz, mixed single-spike and burst firing with characteristic decrease of the action potentials amplitude within the bursts [

25].

2.4. Electrophysiological Data Analysis

Action potentials generated by 5-HT, noradrenergic, and dopaminergic neurons were detected using the spike sorting algorithm, with the version 6.02 of Spike2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK). The neuronal firing rate and burst activity characteristics were calculated using the burstiDAtor software (

www.github.com/nno/burstidator). The onset of a burst was signified by the occurrence of two spikes with ISI <0.08 s for noradrenaline and dopamine neurons, and ISI <0.01 s for 5-HT neurons. The termination of a burst was defined as an ISI >0.16 s for noradrenaline and dopamine neurons [

26,

27] and ISI > 0.010s for 5-HT neurons [

28]. The following characteristics of the neuronal firing activity were assessed: mean number of the spontaneously active neurons per electrode track, mean firing rate (Hz), and mean frequency of the bursts (Hz), precent (%) of spikes occurring in the bursts, and mean number of spikes in burst.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical assessments were performed using SigmaPlot 12.5 software (Systat Software Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Single animals were considered experimental units in the NOR experiments. Single neurons were considered experimental units in electrophysiology experiments. Data was shown as mean ± standard error or mean (SEM). Two-tailed Student’s t-test, predeceased by F-test assessment of the variance, was used to determine the effect of royal jelly on the NOR scores and excitability of monoaminergic neurons. The probability of p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

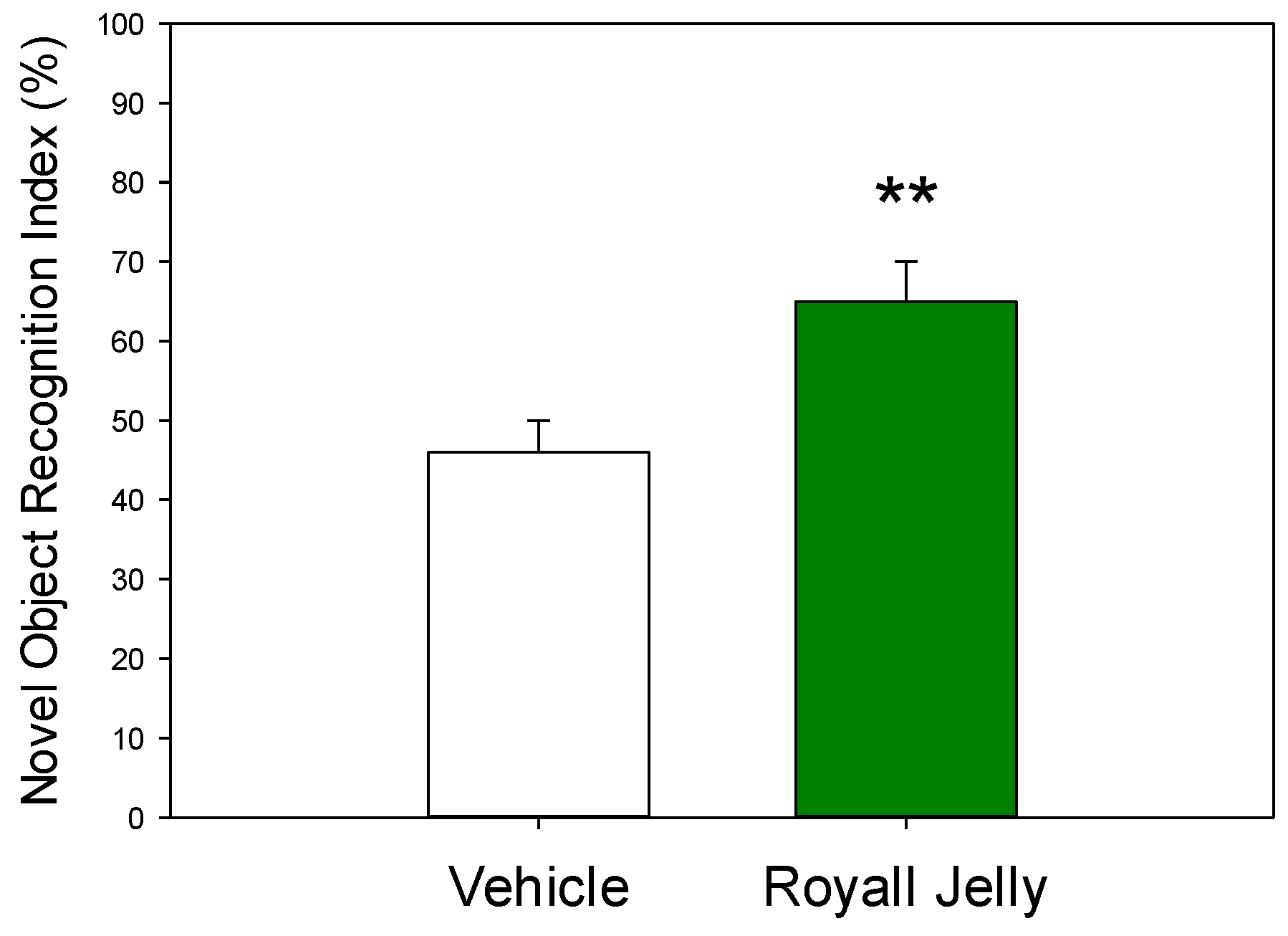

3.1. Repeated Treatment with Royal Jelly Improved Recognition Index in the NOR Test

Figure 1 illustrates the effect of two-week administration of royal jelly on the rats’ performance during the NOR test. The values of the recognition index found in the royal jelly-treated rats were significantly higher compared to those in vehicle-treated controls. Statistically significant difference between the groups was revealed by a two-tailed Student’s t-test (p=0.007).

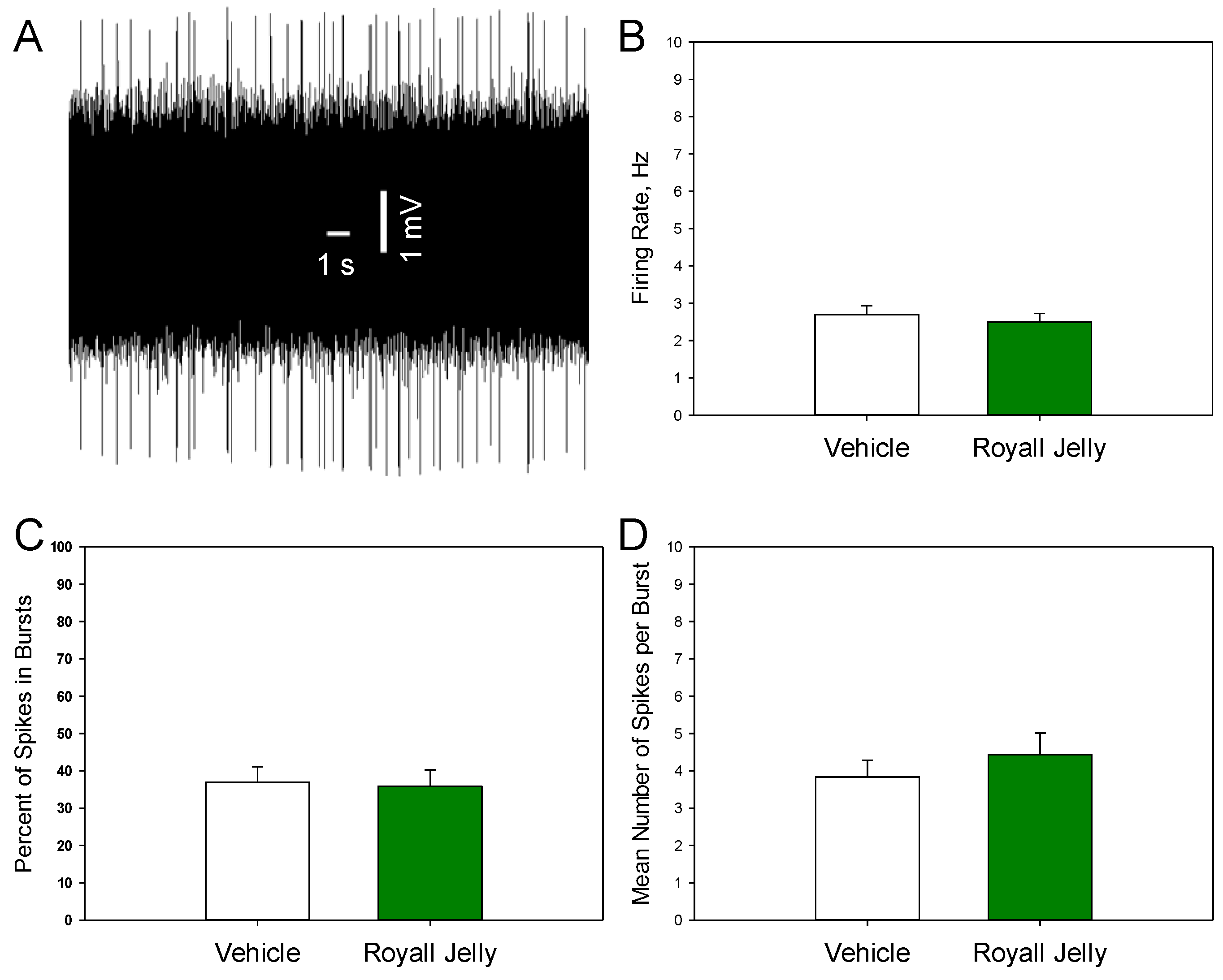

3.2. Royal Jelly Did Not Alter the Excitability of 5-HT Neurons of the DRN

Figure 2 shows a representative recording from a DRN 5-HT neuron (A) and illustrates the mean spontaneous firing rate (B), percentage of spikes occurring in bursts (C), and mean number of spikes per burst (D) of 5-HT neurons in the vehicle- and royal jelly-treated rats. No differences between the groups were observed. Other characteristics of 5-HT neuronal firing activity, such as the mean number of the spontaneously active neurons per electrode track and mean frequency of the bursts, not shown in the illustration, were not affected by chronic royal jelly as well.

3.3. Royal Jelly Did Not Alter the Excitability of Noradrenergic Neurons of the LC

Figure 3 shows a representative recording from a DRN 5-HT neuron (A) and illustrates the mean spontaneous firing rate (B), percentage of spikes occurring in bursts (C), and mean number of spikes per burst (D) in the vehicle- and royal jelly-treated rats. No differences between the groups were observed. Other characteristics of noradrenergic neuronal firing activity, such as the mean number of the spontaneously active neurons per electrode track and mean frequency of the bursts, not shown in the illustration, were not affected by chronic royal jelly as well.

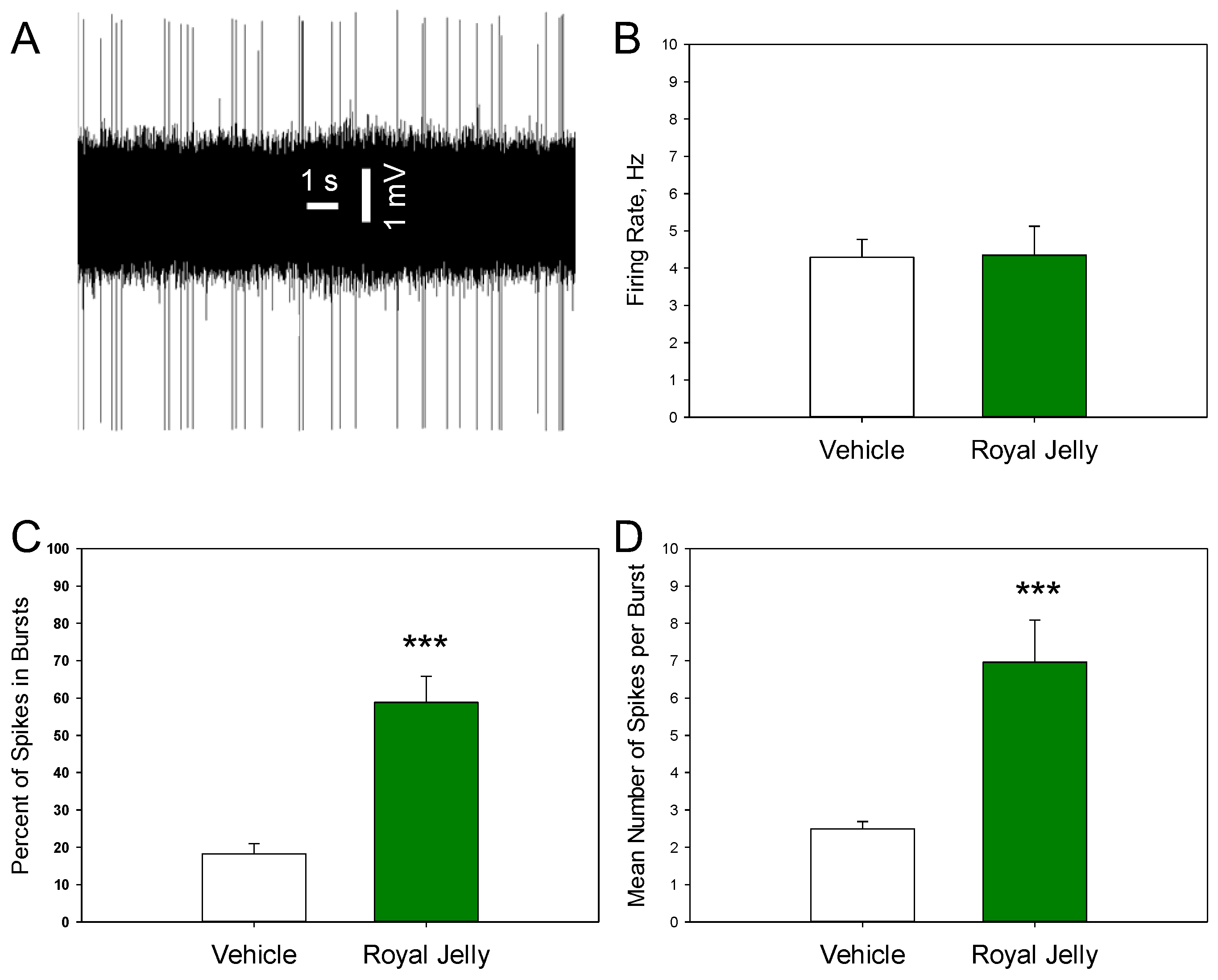

3.2. Royal Jelly Enhanced the Burst Firing of Dopamine Neurons of the VTA

Figure 4 shows a representative recording from a DRN 5-HT neuron (A) and illustrates the mean spontaneous firing rate (B), percentage of spikes occurring in bursts (C), and mean number of spikes per burst (D) in the vehicle- and royal jelly-treated rats. No differences in the mean spontaneous firing rate between the groups were observed. The percentage of neurons occurring in the bursts (p=0.00001) and mean number of spikes in bursts (p=0.001, two-tailed Student’s t-test) in the royal jelly-treated rats were, however, significantly higher compared to the vehicle-treated controls. Other characteristics of 5-HT neuronal firing activity, such as the mean number of the spontaneously active neurons per electrode track and mean frequency of the bursts, not shown in the illustration, were not affected by chronic royal jelly.

4. Discussion

The main findings of the present study are that chronic treatment of rats with royal jelly led to improved cognitive performance and increased burst firing of dopaminergic neurons. The mean firing rate of 5-HT, noradrenergic, and dopaminergic neurons, as well as burst firing of noradrenergic and 5-HT neurons, were not affected by the treatment with royal jelly.

We found that the rats treated with royal jelly had higher recognition index in the NOR test than the vehicle-treated controls. This finding is in strong agreement with the data previously observed and published by Ghorbanpour and colleagues [

16]. Similarly to the present study, these authors used novel object recognition as a behavioral test to assess cognitive performance. In contrast to the present study, they initially exposed the rats to two stressors to evoke stress-induced cognitive impairment. Thus, the results obtained in the present study allow suggesting that treatment with royal jelly results in pro-cognitive effects even in the absence of induction of cognitive function impairments.

Our finding on pro-cognitive effect of royal jelly is also consistent with the report of Pyrzanowska and co-authors on the spatial memory-improving effect of long-term administration of this honeybee product in aged rats [

29]. Royal jelly is a natural compound whose exact composition varies depending on the honeybee species, nectar source, climatic conditions, season, and other environmental factors [

30]. Therefore, the fact that results obtained in one laboratory using one batch of royal jelly can be reproduced in another laboratory using a different batch is of crucial importance. Such replication of the results allows suggesting that the pro-cognitive behavioral effects of royal jelly are likely attributable to one or more of its core chemical components—such as MRJPs—which are consistently present across different batches, rather than depending on a specific source of the product.

The electrophysiological measurements in the present study failed to reveal any effects of repeated royal jelly administration on the excitability of 5-HT neurons of the DRN and noradrenergic neurons of the LC. It may be speculated that the pro-cognitive, anxiolytic, and antidepressant-like effects of royal jelly, reported in previous studies [

16,

29], are not dominantly induced via mechanisms involving the brain 5-HT and/or noradrenergic systems. Alternatively, royal jelly still can alter 5-HT and noradrenergic neurons, by a mechanism not involving the action potentials generation in the cells releasing these neurotransmitters.

An important finding of the present study is the enhancement of burst firing of dopamine neurons induced by repeated treatment with royal jelly. Since the burst mode of firing of dopamine neurons is associated with higher efficiency of the nerve terminal transmitter release [

19], the administration of royal jelly is likely to induce an augmentation of mesocorticolimbic dopamine neurotransmission. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to examine the royal jelly effect on dopamine neurotransmission in a vertebrate species. It is known however that intake of tyrosine in royal jelly can increase dopamine concentration in the honeybee neural system [

31]. Furthermore, pro-dopaminergic effect of the royal jelly is responsible, at least in part, for the pigmentation pattern creation in honeybee queens [

32] and for the transition from normal to reproductive workers in queen-less honeybee colonies [

33].

Among others, mesocorticolimbic dopaminergic neurotransmission is fundamental in cognitive functions, such as memory and attention. Particularly, the linkage between the behavior of rats in the NOR test and the firing activity of the VTA dopaminergic neurons was demonstrated in previous studies from our [

21], as well as from other laboratories [

34,

35]. It is thus likely that pro-cognitive, memory-improving effects of royal jelly, observed in previous studies [

16,

29] as well as in the present work, are based on a mechanism involving VTA dopaminergic system.

The primary limitation of the present study is the lack of identification of the exact biological molecule(s) responsible for pro-dopaminergic and pro-cognitive effect of the royal jelly. It is possible that one or multiple MRJP(s) exert an epigenetic modulation of the expression of the genes coding for proteins regulating dopaminergic transmission, such as dopamine transporter (DAT) and/or dopaminergic receptors. This hypothesis should be tested in future studies.

5. Conclusions

The results of the present experiments confirmed our working hypothesis, showing that the excitability of dopaminergic neurons, though not that of serotoninergic and noradrenergic neurons, is associated with pro-cognitive effects induced by a two-week treatment with royal jelly in male middle-aged rats. The present results encourage further research towards the improvement of the safety and efficacy of currently available therapies for cognitive dysfunction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Katarina Bíliková, Daniela Ježová and Eliyahu Dremencov; Data curation, Daniil Grinchii, Henrieta Oravcová, Hande Özbaşak, Matej Račický and Eliyahu Dremencov; Formal analysis, Daniil Grinchii, Henrieta Oravcová, Hande Özbaşak, Matej Račický and Eliyahu Dremencov; Funding acquisition, Katarina Bíliková and Eliyahu Dremencov; Investigation, Katarina Bíliková, Daniela Ježová, Daniil Grinchii, Henrieta Oravcová, Hande Özbaşak, Matej Račický and Eliyahu Dremencov; Methodology, Katarina Bíliková, Daniela Ježová, Daniil Grinchii, Henrieta Oravcová, Tatiana Krištof Kraková, Hande Özbaşak, Matej Račický and Eliyahu Dremencov; Project administration, Katarina Bíliková, Daniela Ježová and Eliyahu Dremencov; Resources, Katarina Bíliková and Eliyahu Dremencov; Software, Daniil Grinchii, Henrieta Oravcová, Hande Özbaşak, Matej Račický and Eliyahu Dremencov; Supervision, Katarina Bíliková, Daniela Ježová and Eliyahu Dremencov; Validation, Katarina Bíliková, Daniela Ježová and Eliyahu Dremencov; Visualization, Eliyahu Dremencov; Writing – original draft, Katarina Bíliková, Daniela Ježová, Daniil Grinchii, Henrieta Oravcová, Tatiana Krištof Kraková, Hande Özbaşak, Matej Račický and Eliyahu Dremencov; Writing – review & editing, Katarina Bíliková, Daniela Ježová, Daniil Grinchii, Henrieta Oravcová, Tatiana Krištof Kraková, Hande Özbaşak, Matej Račický and Eliyahu Dremencov.

Funding

This research was funded by Royal Jelly Japan, Slovak Research and Development Agency (grant APVV-24-0131) and by the Research Grant Agency of the Slovak Academy of Sciences and Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic (grant 2/0045/24).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific Purposes. The animal study protocol was approved by the Animal Health and Animal Welfare Division of the State Veterinary and Food Administration of the Slovak Republic (Permit number No. Ro 2019/2022-220).

Data Availability Statement

The original research data is available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Royal Jelly Japan for providing us with their royal jelly samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 5-HT |

Serotonin |

| BDNF |

Brain derived neurotrophic factor |

| DRN |

Dorsal raphe nucleus |

| LC |

Locus coeruleus |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| MRJP |

Major royal jelly protein |

| NOR |

Novel object recognition |

| PBS |

Phosphate-buffered saline |

| VTA |

Ventral tegmental area |

References

- Sabatini AG, Marcazzan GL, Caboni MF, Bogdanov S, Bicudo L, de Almeida-Muradian LB. Quality and standardisation of Royal Jelly. Journal of ApiProduct and ApiMedical Science. 2009;1:1-6. [CrossRef]

- Weinstock GM, Robinson GE, Bilikova K, Simuth J. Insights into social insects from the genome of the honeybee Apis mellifera. Nature. 2006;443:931-49. [CrossRef]

- Schmitzová J, Klaudiny J, Albert S, Schröder W, Schreckengost W, Hanes J, et al. A family of major royal jelly proteins of the honeybee Apis mellifera L. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1998;54:1020-30. [CrossRef]

- Šimúth J. Some properties of the main protein of honeybee (Apis mellifera) royal jelly. Apidologie. 2001;32:69-80.

- Kucharski R, Maleszka R, Hayward DC, Ball EE. A royal jelly protein is expressed in a subset of Kenyon cells in the mushroom bodies of the honey bee brain. Naturwissenschaften. 1998;85:343-6. [CrossRef]

- Hanes J, Šimuth J. Identification and partial characterization of the major royal jelly protein of the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.). Journal of Apicultural Research. 1992;31:22-6. [CrossRef]

- Kubo T, Sasaki M, Nakamura J, Sasagawa H, Ohashi K, Takeuchi H, et al. Change in the expression of hypopharyngeal-gland proteins of the worker honeybees (Apis mellifera L.) with age and/or role. J Biochem. 1996;119:291-5. [CrossRef]

- Evans JD, Wheeler DE. Differential gene expression between developing queens and workers in the honey bee, Apis mellifera. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5575-80. [CrossRef]

- Maleszka R. Epigenetic integration of environmental and genomic signals in honey bees: the critical interplay of nutritional, brain and reproductive networks. Epigenetics. 2008;3:188-92. [CrossRef]

- Oršolić N, Jazvinšćak Jembrek M. Royal Jelly: Biological Action and Health Benefits. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;2. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad S, Campos MG, Fratini F, Altaye SZ, Li J. New Insights into the Biological and Pharmaceutical Properties of Royal Jelly. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21. [CrossRef]

- Ramadan MF, Al-Ghamdi A. Bioactive compounds and health-promoting properties of royal jelly: A review. Journal of Functional Foods. 2012;4:39-52. [CrossRef]

- Šimúth J, Bíliková K, Kováčová E, Kuzmová Z, Schroder W. Immunochemical Approach to Detection of Adulteration in Honey: Physiologically Active Royal Jelly Protein Stimulating TNF-α Release Is a Regular Component of Honey. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2004;52:2154-8. [CrossRef]

- Simuth J, Bilikova K. Potential contribution of royal jelly proteins for health. Honeybee Science - Tamagawa University (Japan). 2004;25:53-62.

- Bilikova K, Kristof Krakova T, Yamaguchi K, Yamaguchi Y. Major royal jelly proteins as markers of authenticity and quality of honey. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol. 2015;66:259-67. [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanpour AM, Saboor M, Panahizadeh R, Saadati H, Dadkhah M. Combined effects of royal jelly and environmental enrichment against stress-induced cognitive and behavioral alterations in male rats: behavioral and molecular studies. Nutr Neurosci. 2022;25:1860-71. [CrossRef]

- Licznerski P, Duman RS. Remodeling of axo-spinous synapses in the pathophysiology and treatment of depression. Neuroscience. 2013;251:33-50. [CrossRef]

- Stahl SM. Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Applications. 5 ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2021.

- Cooper DC. The significance of action potential bursting in the brain reward circuit. Neurochem Int. 2002;41:333-40. [CrossRef]

- Hlavacova N, Chmelova M, Danevova V, Csanova A, Jezova D. Inhibition of fatty-acid amide hydrolyse (FAAH) exerts cognitive improvements in male but not female rats. Endocr Regul. 2015;49:131-6. [CrossRef]

- Dremencov E, Oravcova H, Grinchii D, Romanova Z, Dekhtiarenko R, Lacinova L, et al. Maternal treatment with a selective delta-opioid receptor agonist during gestation has a sex-specific pro-cognitive action in offspring: mechanisms involved. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1357575. [CrossRef]

- Paliokha R, Vinas-Noguera M, Bukatova S, Grinchii D, Gaburjakova J, Gaburjakova M, et al. Effects of pre-gestational exposure to the stressors and perinatal mirtazapine administration on the excitability of hippocampal glutamate and brainstem monoaminergic neurons, hippocampal neuroplasticity, and anxiety-like behavior in rats. Molecular Psychiatry. 2025;In press. [CrossRef]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. Paxino's and Watson's The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Seventh edition. ed. Amsterdam ; Boston: Elsevier/AP, Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier; 2014.

- Vandermaelen CP, Aghajanian GK. Electrophysiological and pharmacological characterization of serotonergic dorsal raphe neurons recorded extracellularly and intracellularly in rat brain slices. Brain Res. 1983;289:109-19. [CrossRef]

- Grace AA, Bunney BS. Intracellular and extracellular electrophysiology of nigral dopaminergic neurons--1. Identification and characterization. Neuroscience. 1983;10:301-15. [CrossRef]

- Grace A, Bunney B. The control of firing pattern in nigral dopamine neurons: burst firing. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1984;4:2877-90. [CrossRef]

- Dawe GS, Huff KD, Vandergriff JL, Sharp T, O'Neill MJ, Rasmussen K. Olanzapine activates the rat locus coeruleus: in vivo electrophysiology and c-Fos immunoreactivity. Biological psychiatry. 2001;50:510-20. [CrossRef]

- Hajós M, Allers KA, Jennings K, Sharp T, Charette G, Sík A, et al. Neurochemical identification of stereotypic burst-firing neurons in the rat dorsal raphe nucleus using juxtacellular labelling methods. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:119-26. [CrossRef]

- Pyrzanowska J, Piechal A, Blecharz-Klin K, Joniec-Maciejak I, Graikou K, Chinou I, et al. Long-term administration of Greek Royal Jelly improves spatial memory and influences the concentration of brain neurotransmitters in naturally aged Wistar male rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;155:343-51. [CrossRef]

- Khalfan Saeed Alwali Alkindi F, El–Keblawy A, Lamghari Ridouane F, Bano Mirza S. Factors influencing the quality of Royal jelly and its components: a review. Cogent Food & Agriculture. 2024;10:2348253. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki K. Nutrition and dopamine: An intake of tyrosine in royal jelly can affect the brain levels of dopamine in male honeybees (Apis mellifera L.). Journal of Insect Physiology. 2016;87:45-52. [CrossRef]

- Abdelmawla A, Li X, Shi W, Zheng Y, Zeng Z, He X. Roles of DNA Methylation in Color Alternation of Eastern Honey Bees (Apis cerana) Induced by the Royal Jelly of Western Honey Bees (Apis mellifera). Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25. [CrossRef]

- Matsuyama S, Nagao T, Sasaki K. Consumption of tyrosine in royal jelly increases brain levels of dopamine and tyramine and promotes transition from normal to reproductive workers in queenless honey bee colonies. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2015;211:1-8. [CrossRef]

- Fleury S, Kolaric R, Espera J, Ha Q, Tomaio J, Gether U, et al. Role of dopamine neurons in familiarity. Eur J Neurosci. 2024;59:2522-34. [CrossRef]

- Klinger K, Gomes FV, Rincón-Cortés M, Grace AA. Female rats are resistant to the long-lasting neurobehavioral changes induced by adolescent stress exposure. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;29:1127-37. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).