1. Introduction

Decision-making theory has developed over many decades at the intersection of economics, mathematics, psychology, and engineering. Its classical foundations include Bernoulli’s expected utility theory, von Neumann and Morgenstern’s rational choice theory, and the criteria of Savage, Wald, Hurwicz, and others. However, in real-world conditions, decisions are made under uncertainty, incompleteness, and unreliability of information, which classical approaches do not adequately address. To overcome these limitations, modern multi-criteria decision-making methods such as AHP, TOPSIS, VIKOR, and ELECTRE, as well as their fuzzy and Z-number extensions, are widely applied in modeling complex systems. These Z-number extensions are based on the concept of Z-numbers introduced by Lotfi Zadeh in 2011 to formalize higher-order uncertainty. This study introduces the Z-Regret principle, which extends Savage’s regret criterion through the use of Z-numbers. Drawing on Rafik Aliev’s methods for arithmetic operations on Z-numbers, the model evaluates regret not only as a loss relative to the best alternative but also by incorporating the degree of confidence and reliability of this evaluation. Calculations for the selection of digital advertising platforms in terms of performance assessment under various scenarios demonstrate that the Z-Regret principle provides more stable and well-founded decisions under uncertainty.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Classical Decision-Making Theories

The main distinguishing criterion in the theory of decision-making is the degree of awareness of the probabilities of cases of nature corresponding to possible consequences. For cases where the probabilities are objectively known (risk conditions), Bernoulli [

1] proposed the idea of measuring the benefit and calculating the expected value, while von Neumann and Morgenstern [

2] summarized this approach with the axiomatic basis of rationality. For cases where probabilities are not known exactly but can be estimated by subjective assessment, Savage [

3] developed the concept of subjective probability, substantiating the application of benefit theory under conditions of uncertainty. Finally, for cases where probabilities are not known at all, decision-making was carried out according to Wald’s Maximin approach [

4] and Hurwicz’s criterion [

5], as well as the minimax regret principle introduced by Savage in the same work [

3].

Classical decision-making principles are usually based on the degree of knowledge of probabilities. However, the growing complexity of decision-making processes has necessitated the development of new methods to address problems under multi-criteria and multi-alternative conditions. In this context, the multi-attribute utility theory introduced by Keeney and Raiffa [

6] enabled the evaluation of alternatives across multiple objectives. The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), developed by Saaty [

7], provided a hierarchical structure and a mechanism for pairwise comparison of criteria. The TOPSIS method proposed by Hwang and Yoon [

8] facilitated decision-making in multi-alternative settings by selecting solutions based on their relative closeness to the ideal and distance from the anti-ideal.

Within social choice theory, Arrow’s impossibility theorem [

9] and the Gibbard–Satterthwaite results [

10,

11] revealed inherent limitations in collective choice.In game theory, Nash [

12,

13], Harsanyi [

14], and Selten [

15] established a theoretical foundation for modeling interdependent decisions. Finally, Simon’s concept of “bounded rationality” [

16] and Kahneman and Tversky’s Prospect Theory [

17] highlighted the impact of psychological constraints and behavioral factors on decision-making processes.

2.2. Fuzzy Sets and Their Extensions

A major turning point in the modeling of uncertainty was the introduction of fuzzy sets by Zadeh [

18]. Based on this theoretical foundation, a number of extensions were subsequently developed: the possibility theory of Dubois and Prade [

20], Shafer’s evidence theory [

21], and Atanassov’s intuitionistic fuzzy sets [

22] are regarded as important contributions to the modeling of uncertain knowledge.

One of the key milestones in the evolution of fuzzy approaches has been their integration with classical multi-criteria decision-making methods. For example, Saaty’s Analytic Hierarchy Process has been extended into the fuzzy-AHP form [

44], while the TOPSIS method of Hwang and Yoon has been generalized into fuzzy-TOPSIS [

45]. These approaches have enabled the incorporation of uncertain and incomplete information into the decision-making process, allowing for more realistic and reliable results in the fields of economics [

37,

39,

54,

55,

56] and management [

38,

57].

Applications include the selection of market structures [

54], segmentation of economic regions [

55], improvement of enterprise management efficiency [

56], and the processing of flexible queries in commercial enterprise databases [

57].

2.3. Theoretical Foundations of Z-Numbers

Z-Numbers allow not only the representation of uncertainty in terms of its content but also take into account the degree of reliability of the information. However, in most existing studies, the computational procedures have been carried out by converting Z-Numbers either into fuzzy numbers or into crisp values. For example, Kang, Wei, Li, and Deng [

43] proposed a method for transforming Z-Numbers into classical fuzzy numbers. Although such approaches provide computational simplicity, the additional information carried by Z-Numbers—particularly the reliability component—is lost.

Rafik Aliev further advanced this theoretical foundation by developing mathematical mechanisms for performing direct calculations on Z-Numbers [ 40, 41, 58]. Under his leadership, methods for comparison, normalization, distance measures, and aggregation rules for Z-Numbers were formulated, thereby significantly expanding the applicability of Z-Number-based decision-making models. His monograph

Fundamentals of the Fuzzy Logic-Based Generalized Theory of Decisions [

23] played a systematizing role in this direction and generalized the practical applications of Z-Numbers across economics, management, and engineering.

2.4. Application Examples of Z-Numbers

In the subsequent stage, international studies have demonstrated the real application potential of Z-Numbers across various fields. Liao [

31] presented a comprehensive review of theoretical and practical applications of Z-Number-based decision-making methods. Wang [

32] developed a new approach to multi-attribute group decision-making, while Su et al. [

33] introduced the Z-DEMATEL method in the energy sector. Alam and Badrul [

34] applied the integration of Z-Numbers into fuzzy decision-making processes under uncertainty, and Wu and Chen [

35] proposed a spherical Z-Number-based model for multi-attribute group decision-making. Alam (2023) proposed a synergic approach for the ranking of Z-numbers based on

vectorial distance and the

spread criterion. The method integrates the content and reliability components of Z-numbers, providing more accurate comparisons and expanding their applicability in multi-criteria decision-making processes [

36]. The work

The Arithmetic of Z-Numbers by Aliev and colleagues [

40] further deepened the theoretical foundations of these approaches and expanded their applicability in economics and engineering.

Applications of Z-Numbers have also become widespread in the management of economic and business processes. Various studies have employed this approach in assessing employee motivation, processing survey data, detecting anomalies, and managing risks in energy consumption, often in combination with soft-computing methods [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50]. Furthermore, applications have been reported in evaluating enterprise development levels [

50], applying Z-information-based scenarios in energy policy development [

51], and developing multi-criteria approaches for the location selection of retail outlets [

52]. In addition, the integration of Z-Numbers with fuzzy MCDM approaches has yielded new results in modeling the renewable energy transition [

53].

3. Necessity of the Z-Regret Model for Robust Decisions under Uncertainty

Savage’s regret principle [

3] is based on minimizing the maximum possible regret under uncertainty and serves as an important alternative criterion in classical decision theory. However, regret relies solely on the comparison of outcomes and does not take into account the accuracy or reliability of the information. This limitation is highly significant in real-life contexts, since uncertainty arises not only from the imprecision of outcomes but also from the degree of reliability of the available information.

Z-Numbers were introduced to overcome this limitation. A Z-Number, expressed as Z = (A, B), consists of two components: A, representing the fuzzy assessment, and B, denoting the degree of reliability of that assessment [

19]. Thus, when regret is formulated through Z-Numbers, it reflects not only the loss relative to the best outcome but also the extent to which this loss is observed with a certain degree of reliability. This constitutes the essence of the Z-Regret model.

The Z-Regret approach enables more robust decision-making under uncertainty, as it simultaneously evaluates both the fuzzy analysis of outcomes and the reliability of the information. This approach represents a logical continuation of Rafik Aliev’s generalized decision theory based on Z-Numbers [

23] and lays the foundation for a new stage in the development of decision theory.

4. Preliminaries

This section systematically outlines the foundational concepts, beginning with classical decision-making theories and progressing through fuzzy approaches to the formulation of Z-numbers. The objective is to construct a coherent theoretical framework that logically culminates in the introduction of the Z-Regret principle.

Definition 1.

Alternatives and States – Scenarios [

1,

2,

3,

4]

. A decision problem is defined by two sets:

Here, A denotes the set of alternatives, and S denotes the set of states of nature (or scena-rios).For each pair, the outcome (utilities and costs) function is defined as:

Definition 2.

Optimal outcome by scenario [

3,

4]

. For each scenario, the optimal outcome is defined depending on the objective as follows:

Definition 3.

Classical Regret and the Minimax Criterion [

3]

The regret for alternative is defined as:

The worst-case outcome for each alternative:

According to the minimax principle, the optimal alternative is selected as:

The classical regret approach embodies the principle of “minimizing the loss under the worst-case scenario.” However, its fundamental limitation is the inability to incorporate the fuzziness of outcomes and the reliability of information, which are critical factors in real-world decision-making under uncertainty.

Definition 4.

Fuzzy Numbers [

18,

23,

42]

. A fuzzy number A on a universe X is defined as follows:

Here,is the membership function.

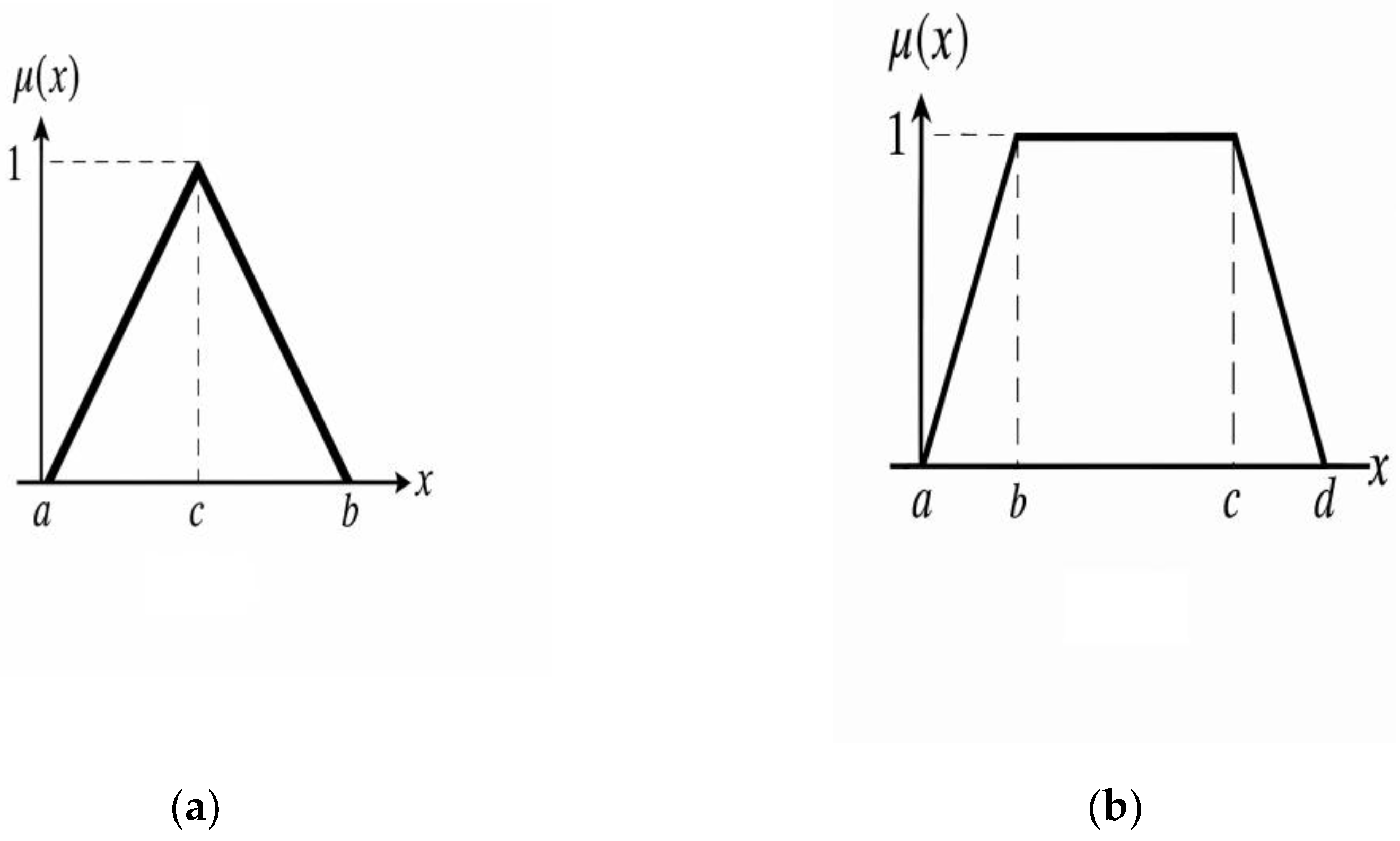

Figure 1a illustrates a triangular fuzzy number. Here, uncertainty is represented by a single maximum point. A triangular fuzzy number is characterized by three parameters: A = (a, c, b).

Here:

a – the starting point (left support), where the membership value is .

c – the peak of the triangle, where the membership function reaches its maximum value - .

b – the end point (right support), where again .

The membership function is mathematically defined as follows:

Since this function is triangular in shape, it represents one of the simplest fuzzy numbers and is often used in modeling uncertainties.

Figure 1b illustrates a trapezoidal fuzzy number, in which uncertainty is represented by a constant maximum interval. A trapezoidal fuzzy number is defined by four parameters: B = (a, b, c, d).

Here:

a – the starting point (left support), where μ(x)=0\mu(x)=0μ(x)=0.

b – the left inflection point, where the membership function increases from 0 to 1.

c – the right inflection point, where the membership function begins to decrease from 1 to 0.

d – the end point (right support), where μ(x)=0.

The membership function is mathematically expressed as follows:

Trapezoidal fuzzy numbers are more flexible compared to triangular fuzzy numbers, as they incorporate a region of constancy .In this interval, the membership value is always equal to 1.

Both membership functions are considered among the most commonly used functions for defining fuzzy sets.

Definition 5.

Z-numbers [

19,

40,

41,

58]

. A Z-number is defined as a three-component construct.

Where:

X denotes the variable or linguistic descriptor under consideration,

is a fuzzy restriction on the values of X, representing the outcome or evaluation,

is a fuzzy number, interval, or probability distribution that expresses the reliability of the statement X=.

The main differences between classical numbers, fuzzy numbers, and Z-numbers are presented in

Table 1.

Definition 6.

The distance function between Z-numbers [41,58]. The distance function between two Z-numbers is defined as follows:

Here,andare the distances between the A and B components of the Z-numbers, respectively. α\alphaα represents the degree of preference assigned to either the A or B component of the Z-number.

Defintion 7.

Arithmetic operations on Z-numbers are defined so as to preserve the closure property; the theoretical foundations are developed in detail in [

41,

58].

Table 2 presents a step-by-step mathematical derivation of the subtraction operation (Equation (11)) applied to two Z-numbers, and .

Here,

- the fuzzy number obtained as the result of the difference between the fuzzy numbers and ,

- the fuzzy number obtained as the result of the difference between the fuzzy numbers and ,

- the membership function of the fuzzy number A,

μB(w) - the membership function of the reliability component of the Z-number obtained as a result of the difference between Z-numbers,

∧ - the minimum operator (fuzzy intersection),

sup - the supremum (the least upper bound; equivalent to “max” in fuzzy computation),

and - are the probability density functions corresponding to the probability components of and respectively,

- is the density function resulting from the difference of two probability distributions (convolution),

- is the probability distribution obtained after the subtraction operation,

- are the discrete support values of the reliability component ,

- are the membership degrees at the points ,

-is the value of the probability distribution at the point ,

- is the value of the membership function of the fuzzy set ,

—are the unknown probability variables in the linear programming problem,

- is the mean value that ensures the consistency condition; it is used to verify the compatibility of the AZ and BZ components.

Definition 8.

Finding the minimum and maximum of discrete Z-numbers ([

41,

58]

).

are discrete Z-numbers. The minimum is defined as follows:

The B reliability component is constructed based on the membership degrees of fuzzy probability distributions.

In the case of the maximum,

and the convolution operation is performed in the “max” form.

These rules demonstrate that Z-numbers possess a closed structure under operations [

41,

58]: both the minimum and the maximum also yield a Z-number.

Definition 9.

Conversion of Z-numbers into classical fuzzy numbers: Kang et al. [

43]

proposed a method for transforming Z-numbers into classical fuzzy numbers. Based on this method, the conversion of into a classical fuzzy number is explained step by step as follows:

Scalarization of the reliability component.

Here,denotes the membership function of the fuzzy number, while α represents the scalar value that determines the degree of reliability.

The fuzzy number is transformed into a weighted fuzzy number based on the reliability degree α.

Here, represents the membership function of the fuzzy number .

The weighted fuzzy number

is transformed into a classical fuzzy number as follows:

As a result, the classical fuzzy number obtained from

is expressed as follows:

Definition 10.

Ranking of classical fuzzy numbers based on the Wang Ranking method. Wang et al. [

42]

introduced the centroid formula for generalized fuzzy numbers.

Specifically, for a generalized trapezoidal fuzzy number:

the centroid coordinates are given as follows:

and the ranking function corresponding to the fuzzy number

is defined as follows:

The ranking rules for two fuzzy numbers and should be carried out as follows:

If then ;

If then ;

If then .

This method has been proposed to ensure a more stable and accurate comparison of fuzzy numbers.

5. Z-Regret Prinsipi

The classical regret principle (Definitions 1 and 2) expresses utility functions (Equation (2)) using precise scalar values and is based on the criterion of “minimizing the worst-case loss.” While this approach is mathematically straightforward, it does not take into account the uncertainty and reliability factors commonly observed in human decision-making processes. In real-world scenarios, however, decision-makers often assess outcomes not through exact numerical values, but rather through fuzzy evaluations accompanied by degrees of reliability. In this regard, Z-numbers, defined as Z=(A,B), provide a more adequate framework by jointly modeling both the fuzzy assessment of the outcome (A) and the associated degree of reliability (B).

This paper proposes two approaches to extend the classical regret principle based on Z-numbers:

Z-Regret principle. The first approach is based on the closedness principle of Z-numbers and incorporates the computational operations on Z-numbers developed by Rafik Aliev [

40,

41,

58]. In this approach, for each scenario, the ideal Z-number

is selected, and the calculation of the regret matrix is carried out on the basis of the subtraction operation and distance measures on Z-numbers (Definition 6 and Definition 7).

Z-Regret Principle. The second approach is based on the method of transforming Z-numbers into classical fuzzy numbers [

43]. In this approach, the reliability component

is first scalarized, and then the outcome component

is transformed into a weighted fuzzy number. The resulting classical fuzzy numbers are then ranked using the method proposed by Wang [

42], after which the regret-based calculations are carried out in the traditional manner.

Although both approaches are supported by algorithmic procedures and mathematical formalism, the primary aim of this study is to demonstrate that the approach based on the closure property of Z-numbers represents a more fundamental and theoretically sound formulation of the Z-regret principle. Accordingly, the second approach serves an auxiliary and comparative role, while the first approach constitutes the mathematical foundation of the Z-regret model.

5.1. Z-Regret Principle, Approach 1

In this approach, all algorithms and operations carried out in accordance with the classical regret principle are executed on Z-numbers, based on the principle of closure.

Step 1. Construction of the decision matrix. In the decision matrix, the utility (or cost) for each alternative and scenario is given in the form of a Z-number (Definition 5):

the fuzzy evaluation of utility, represented in the form of fuzzy numbers (Definition 4);

the degree of reliability of the fuzzy evaluation of utility, represented in the form of fuzzy numbers;

denotes the Z-utility of alternative iii under scenario jjj.

Table 1, constructed on the basis of Z-numbers, is referred to as the Z-number-based utility matrix (

Table 3).

Step 2. Identification of the scenarios with maximum utility. For each scenario jjj, the best Z-number is selected among all alternatives, and this optimal value is denoted as . Here, the term “best” (i.e., closest to the ideal) is determined based on the minimum distance between the Z-numbers and . The calculation of distances between Z-numbers is carried out using Definition 11 proposed below.

Definition 11

(Proposed). Suppose that two Z-numbers are given:

Here,denote the ideal Z-number for a given scenario.

The computation of regrets based on Z-numbers is carried out through the calculation of distances between Z-numbers, according to the following formula (assuming that the compo nents of Z-numbers are trapezoidal fuzzy numbers, as defined in Definition 4):

For each scenario

, the scenarios with maximum utility

are determined based on the ranking of distances

computed according to the following formula:

Here, M denotes the number of scenarios, and N denotes the number of alternatives. The meaning of formula (25) is that, since the ideal Z-number is chosen as the best—that is, the maximum Z-number—the Z-number closest to it in terms of distance is regarded as optimal. In other words, since the distances to the ideal Z-numbers are the smallest, they are regarded as the Z-numbers possessing the maximum utility across the scenarios. For the purposes of subsequent calculations, let us denote these Z-numbers as .

Step 3. Calculation of the regret matrix. Traditionally, the regret matrix is obtained by calculating the differences between the possible maximum outcome for each state and the current outcome. In our case, since each scenario (state) is represented in the form of Z-numbers, and taking into account the closure principle of Z-numbers, the determination of the regret matrix is carried out by subtracting (⊖) the Z-numbers of each scenario, , from the Z-numbers with maximum utility across the scenarios, . The subtraction operation is performed according to formula (11) in Definition 7.

Table 4 presents the procedure for calculating the regret values for each alternative and scenario based on the Z-regret principle.

Step 4. Determination of the maximum regrets across scenarios for each alternative.

Since each element of the regret matrix is a Z-number, in accordance with Step 2 and Formula (26), for each alternative the maximum Z-number across scenarios, i.e.,

, is determined.

Since being closest to the ideal Z-numbers implies having the minimum distance, unlike in the classical regret principle, instead of using the term “maximum,” we denote the maximum regrets as minimum by .

Step 5. Selection of the minimum among the maximum regrets. In accordance with Formula (24), by calculating the distances from the ideal Z-number and based on the definition of 12, the minimum of the maximum regret values is determined.

Definition 12

(Proposed). The selection of the situation with the minimum value among the maximum regret values, in the classical regret principle, is carried out using Formula (7). In the Z-Regret principle, however, the value corresponding to the farthest point (i.e., the maximum distance) from the ideal Z-number is considered as the minimum regret value (Formula (27)).

Since itself is a Z-number, the obtained result simultaneously reflects both the minimum utility and its associated reliability.

Thus, in this approach, the limitation of the classical regret principle is overcome, as both uncertainty and the corresponding reliability are taken into account.

5.2. Z-Regret Principle, Approach 2

This principle is based on the transformation of Z-numbers into ordinary fuzzy numbers and is carried out in the following sequence:

Step 1. Construction of the decision matrix. This step is identical to Step 1 in Approach 1.

Step 2. Based on Definition 9, by applying formulas (17) and (18), each

number is transformed into ordinary

- fuzzy numbers, and the results are presented as shown in

Table 5.

Step 3. Determination of the ranks of the ordinary fuzzy numbers

. For each ordinary fuzzy number

, the Wang ranks are calculated based on Definition 10 as

(

Table 6).

Step 4. By applying the classical regret algorithm, the maximum ranks across scenarios are determined for each alternative based on

Table 6.

Step 4. Construction of the regret matrix.

Sub-step 4.1. Based on Formula (29), the regret matrix is constructed in accordance with

Table 6.

Step 5. Selection of the minimum among the maximum regrets. Based on Formula (31), the alternative with the minimum “maximum regret” value is identified according to the classical regret principle.

6. Practical Application of the Z-Regret Algorithm

Problem Statement. The assessment of advertising effectiveness is one of the most important issues in the strategic management of companies in the modern digital market. Advertising expenses usually constitute the largest part of the marketing budget, and any misjudgment may lead to significant financial losses directed toward inefficient channels [

24,

25]. Effective performance measurement enables companies to choose channels that provide the highest return on investment (ROI). Therefore, the issue of evaluating advertising effectiveness is of critical importance not only from an economic perspective but also from the standpoint of risk management [

30].

A specific feature of the advertising environment is that it is characterized by a high degree of uncertainty. For example:

In cases of Bot Attacks, a large proportion of clicks do not belong to real users, and as a result, high CTR (Click-Through Rate), CPC (Cost Per Click), and Conversion Rate indicators lead to incorrect decisions [

26,

27].

Seasonal fluctuations (holidays, campaigns, special events) cause significant deviations in performance indicators [

28].

Platform differences also create additional risks. For example, in TikTok advertising, the CTR may be very high, but if data reliability is low (i.e., the share of bots is significant), managing the budget based on this indicator can be highly risky [

29].

Suppose that, in the evaluation of performance in a digital advertising strategy, three alternative platforms and three scenarios are given.:

Alternatives (platforms):

Scenarios (states): S = {: Normal, : Bot Attack,: Seasonal Variation},

For each pair , the advertising performance is represented as a Z-number (the decision matrix): , Here, denotes the evaluation of performance under different scenarios (e.g., a composite score of CTR/ROI) as a trapezoidal fuzzy number within the interval [0, 100], denotes the evaluation of the reliability of as a trapezoidal fuzzy number within the interval (0, 1). Trapezoidal fuzzy numbers provide a numerical representation of linguistic terms such as low, medium, high, very high, or expressions of certainty like medium, high, full certainty (Definition 4).

The initial dataset (the decision matrix) was assessed by experts using actual advertising performance indicators (CTR, CPC, Conversion Rate). Subsequently, through linguistic terms, the data were transformed into trapezoidal fuzzy numbers and represented in the form of Z-numbers, as illustrated in

Table 3. In other words,

Step 1 of

Algorithms 5.1 and 5.2 has been implemented, and the corresponding results are provided in

Table 7.

Assumptions and conditions:

Principle of Closedness: The set of Z-numbers is closed under arithmetic and comparison operations; that is, the results of such operations are again represented in the form of a Z-number.;

The distance function in Definition 6 (Formula (10)) takes into account both the performance component (A) and the reliability component (B), and the weights can be selected according to the requirements;

Table 7 presents the alternatives and scenarios as Z-numbers, expressed in terms of pairs of performance (A) and reliability (B). Each of these components is adequately modeled using trapezoidal fuzzy numbers.

A solution to this problem is required. The purpose of this study is to evaluate digital advertising performance under conditions of uncertainty. To this end, the limitations of classical indicators (CTR, CPC, Conversion Rate) are addressed by employing a Z-number approach, which incorporates both the performance component (A) and the degree of reliability (B) of information A.

On the basis of Z-numbers, the proposed Z-Regret principle is used, enabling the comparison of alternatives (Google, Facebook, TikTok) across different scenarios (Normal, Bot Attack, Seasonal Variation). Consequently, the selection of the optimal advertising channel is carried out in accordance with the requirements of the classical regret principle.

Solution to the Problem. To demonstrate the practical efficacy of the proposed Z-Regret principle, we now present a step-by-step procedure for solving this problem based on this principle.

The problem was solved by considering both approaches proposed within the framework of the Z-principle.

6.1. Solution of The Formulated Problem Under Approach 1

Step 1. In the problem formulation section, the decision matrix is presented in

Table 7.

Step 2: At this stage, for each scenario (j =), the maximum (optimal) - values are to be identified. For simplicity, for each scenario we assume the overall ideal as . In the comparison, the Z-number that is at the smallest distance from the ideal Z-number is considered the maximum Z-number.The distance comparisons between Z-numbers and the ideal Z-number are carried out on the basis of Definition 11 and Formula 10.

Now, for each scenario, let us calculate the distance from this ideal number according to Formula 10 (where is assumed).

The calculations yield the following results:

-

Scenario S1 — the scenario of ‘Normal Conditions’:

Distances: =40.00, = 50.125, = 60.35.

Result: the smallest distance from the ideal is . For the ‘Normal Condition’ scenario, the maximum is = Z₁ (Google)= {A=[70,75,85,90],B= [0.95,1.00,1.00,1.00]}.

-

Scenario S2 — the scenario of ‘Bot Attack’:

Distances: =100.35, =80.35, = 90.35.

Result: For the ‘Bot Attack’ scenario, the maximum is = Z2 (Facebook) = {A=[50,55,65,70], B= [0.70,0.80,0.85,0.90]}.

-

Scenario S3 — the scenario of ‘Seasonal Variation’:

Distances: =60.125, =70.35, = 80.35.

Result: or the ‘Seasonal Variation’ scenario, the maximum is = Z1 (Google) = {A=[60,65,75,80], B=[0.85,0.90,0.95,1.00]}.

The results obtained in Step 2 are presented in

Table 8.

Step 3: At this step, the regret matrix is computed:

Sub-step 1: For each i-th alternative and j-th scenario, the corresponding

is subtracted from the maximum

for that scenario according to Formula (14), based on the computational operations over Z-numbers proposed by Rafik Aliev [

41,

58] (

Definition 7) . As a result, the regret matrix presented in

Table 9 is obtained.

Sub-step 2: Now, using Definition 11 and Formula (24), we calculate the distances for the regret matrix for each scenario (with the overall ideal value

and α=0.5), and determine the maximum values for each scenario (

Table 10).

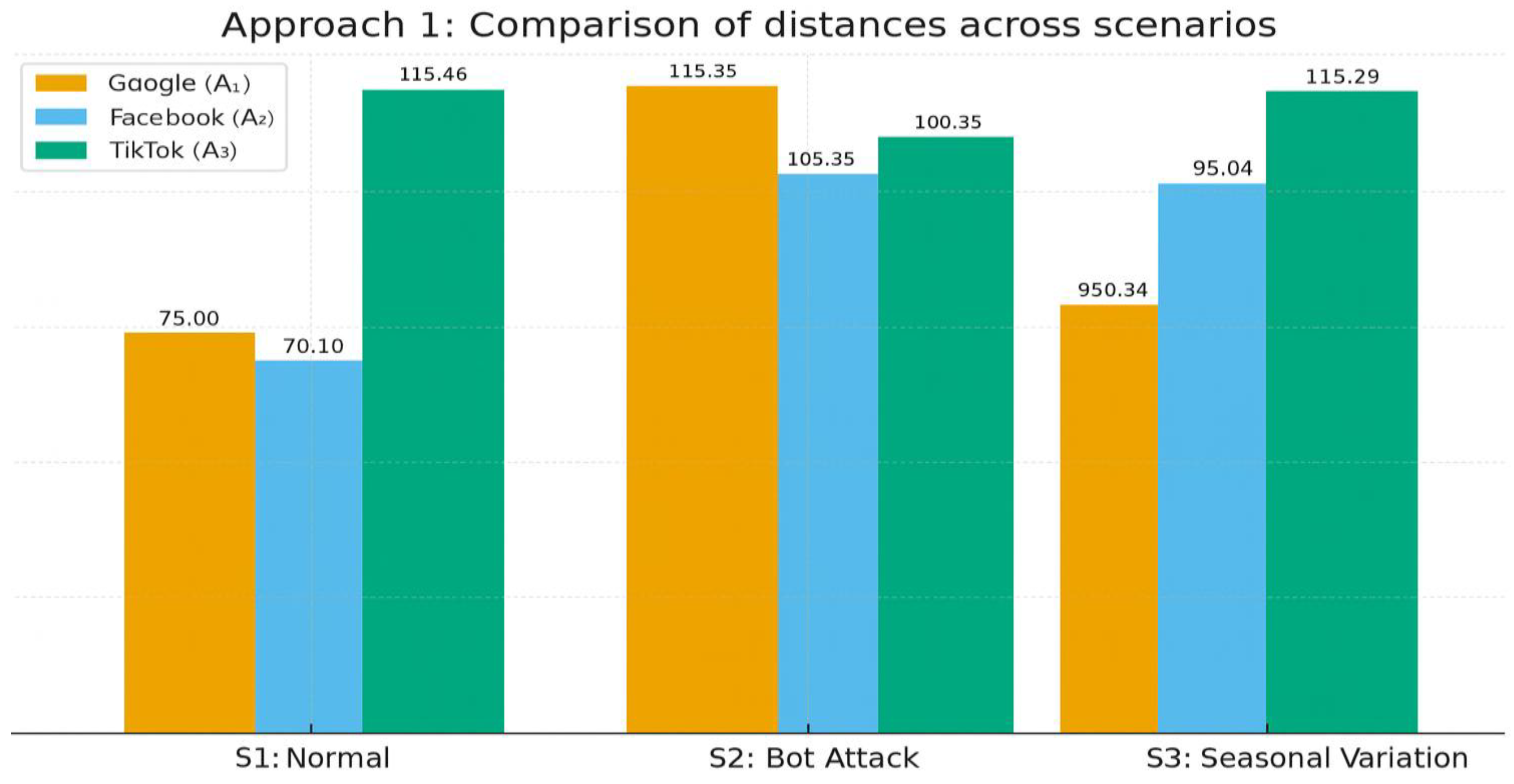

Under Approach 1, the evaluations based on the proximity distances from the ideal state are graphically illustrated in

Figure 2.

Step 4. In this step, the

values are ranked with respect to their proximity to the ideal

number, in accordance with Definition 11 and Formula (25). The obtained results are presented in

Table 11.

Step 5. On the basis of Formula (27) provided in Definition 12, the alternative that exhibits the farthest distance among is regarded as the alternative with the least maximum regret. Thus, by examining this table, we can state that, . Thus, the least maximum regret corresponds to = A: High →[65,70,80,85] , B: High certainty → [0.85,0.90,0.95,1.00]

, which indicates the Facebook alternative. This means that, with high confidence (B: High certainty), it can be stated that among the available advertising platforms, the selection of Facebook for advertising ensures that, even under the worst-case scenario, the potential losses will remain minimal.

6.2. Solution of The Formulated Problem Under Approach 2

Now let us calculate the regrets on the basis of the second approach. The main objective here is to transform the Z-numbers into ordinary fuzzy numbers using the method given in [

43], and then convert them into crisp numbers by applying the Wang Ranking method [

42] for ranking. Subsequently, the classical regret principle is applied to compute the least maximum regret value.

Step 1 . Step 1 is carried out in the same way as in Approach 1.

Step 2. Transformation of Z-numbers into ordinary fuzzy numbers. Using Formulas (17) and (18) in Definition 9, all Z-numbers listed in

Table 7 are converted into ordinary fuzzy numbers, with the outcomes of the transformation shown in

Table 12.

Step 3. Calculation of the ranks of ordinary fuzzy numbers. By applying Formulas (20), (21), and (22) from Definition 10, and assuming

w=1, the ranks of each fuzzy number in

Table 12 are calculated.The obtained results are presented in

Table 13.

Step 4. The application of the classical regret algorithm involves calculating the regret values for each scenario, identifying the maximum values, and constructing the regret matrix.

This procedure is implemented through the following two sub-steps:

Sub-step 4.1. The maximum values calculated across the scenarios are presented in

Table 14.

Sub-step 4.2. Based on the maximum values obtained for the scenarios, the regret matrix elements are derived using Formula (5). The results of these computations are shown in

Table 15.

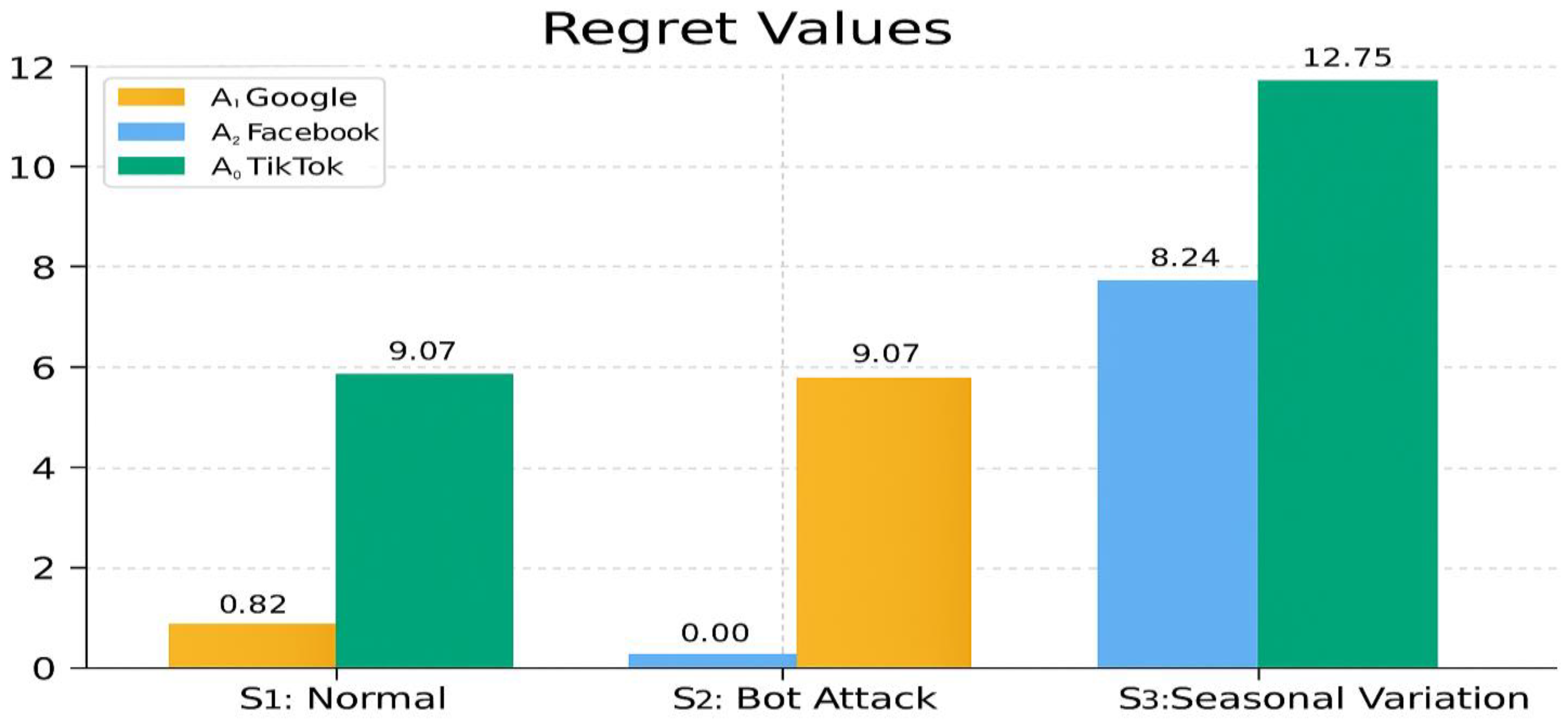

Figure 3 provides a graphical illustration of the regret matrix.

Step 5. At this stage, considering the maximum regret values listed in the Maximum Regret column of

Table 15, the least maximum regret value is obtained through the application of Formula (7) in Definition 3. The corresponding result is provided in

Table 16.

Table 16 shows that

A2 – Facebook, under Approach 2, represents the alternative with the least maximum regret, as its maximum regret value is lower than that of the other al ternatives.

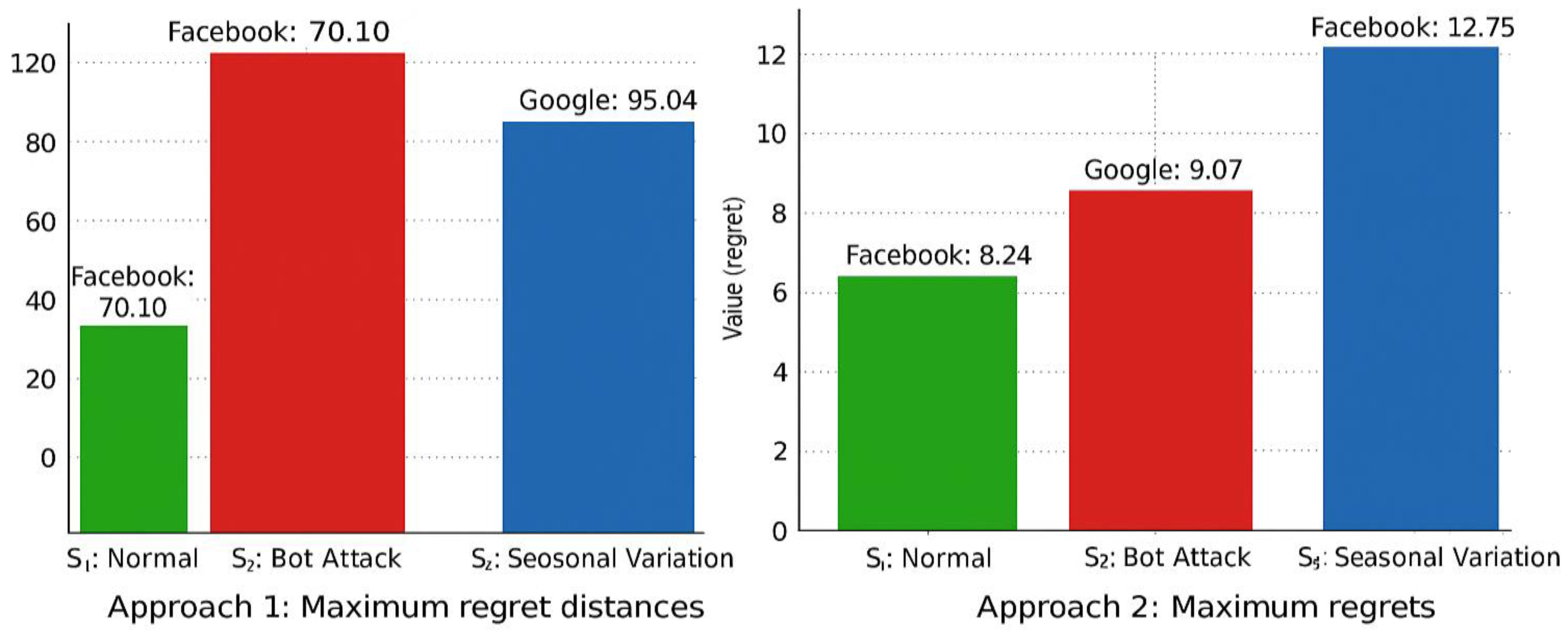

7. Results

The experimental results revealed that both approaches produced the same final outcome; that is, in accordance with the Z-Regret principle, the superior alternative was identified as A₂ - (Facebook) (

Figure 4).

However, the reasons for the selection differ in accordance with the theoretical essence of the computational algorithms proposed for the Z-Regret principle.

Approach 1, by jointly considering both the performance values (A) and their reliability components (B), provides a more reliable and well-grounded result in the Normal Condition scenario where Facebook is selected. Precisely under normal conditions, both the performance indicators are stable and their reliability degree is highly evaluated. As a result, they are expressed in the form of Z-numbers. For this reason, the obtained result is balanced and allows making an optimal decision with maximum reliability. This approach shows that in real conditions it is not sufficient to rely only on the nominal values of performance indicators; in parallel, it is necessary to take into account the quality, stability, and risk factors of the data. Thus, Approach 1 ensures the most robust and risk-resistant decision-making, especially in environments where the information is incomplete, subject to manipulation, and characterized by uncertainty.

In Approach 2, the Z-numbers were first converted into fuzzy numbers and then into crisp values. As a result of this transformation, the influence of the reliability component was weakened, leading to a certain loss of information. In this case, decision-making relied primarily on performance indicators. For this reason, the superiority of Facebook was identified in the Seasonal Variation scenario, as it demonstrated relatively more stable performance values.

Thus, although both approaches coincide in terms of the overall outcome, the decision provided by Approach 1 should be regarded as more well-founded and sustainable. This is because, without incurring any loss of information, the alternatives are evaluated both by their performance indicators and by their level of reliability. This result confirms the superiority of the Z-Regret principle: while the classical regret principle compares only the outcomes, the Z-Regret principle enables more balanced decision-making by taking into account both the outcome and the quality of information.

Managerial Implications

The findings of this study provide significant contributions not only from a theoretical perspective but also for management practice:

- 4.

Optimization of advertising budgets. Companies should not rely solely on high CTR and CPC indicators but also take into account the degree of reliability of these indicators. The Z-Regret approach ensures this balance.

- 5.

Risk management. False indicators arising from bot attacks and click fraud are not considered in classical models. In contrast, Z-Regret enables more resilient decision-making in such cases.

- 6.

Scenario planning. The fact that the justifications of the results differ across scenarios demonstrates that companies should evaluate not only the “best alternative” but also how that alternative behaves under different scenarios.

- 7.

Strategy formulation. By applying the Z-Regret approach, managers can select advertising platforms that ensure long-term stability and resilience.

Approach 1 computations were carried out directly in the Z-environment, integrating both performance (A) and reliability (B) components. Hence, Facebook’s selection under the Normal Condition scenario is considered more justified, as this context ensures both stability of indicators and high reliability. Under normal conditions, performance measures such as CTR, CPC, and Conversion Rate are not subject to disruptive fluctuations, and their associated reliability levels remain consistently high. This integration allows Z-Regret to provide a balanced and maximally reliable decision outcome, demonstrating that the most trustworthy results are achieved precisely when both performance and reliability are jointly taken into account.

In Approach 2, the Z-numbers were first converted into fuzzy numbers and then into crisp values. As a result of this transformation, the influence of the reliability component (B) was weakened, leading to a certain loss of information. Since the decision was based on adjusted performance indicators, the superiority of Facebook was justified in the Seasonal Variation scenario due to its relatively stable performance values. However, because seasonal variation is subject to sharp fluctuations caused by campaigns and holidays, this weakens the confidence in the decision reached.

Thus, although both approaches coincide in terms of the overall outcome, the decision provided by Approach 1 should be considered more well-founded. This is because the alternatives are evaluated not only according to their performance indicators but also with respect to their reliability levels. This feature is particularly critical in risk-prone environments—such as advertising bot attacks or manipulation cases—where robustness and credibility of decisions are of paramount importance.

The analysis of the results further shows that the Z-Regret model not only validates the final decision but also explains how alternatives behave under different scenarios. In Approach 1, the selection of Facebook in the Normal Condition scenario is based on its higher reliability indicators. In Approach 2, however, the same alternative is chosen primarily due to its stability under Seasonal Variation conditions. This difference demonstrates that the Z-Regret principle ensures a more objective evaluation in real decision-making processes by jointly considering the combination of “outcome + reliability” in a balanced manner.

These findings constitute the main contribution of the study: by extending the classical regret theory with a reliability component, the Z-Regret principle enables more robust and well-founded decision-making under conditions of uncertainty.

8. Discussion

The results of the conducted experiments showed that, in both approaches, the final choice according to the minimax criterion was the Facebook (A₂) alternative. However, the justification of the selections across scenarios differed in line with the theoretical essence of each approach. This fact clearly demonstrates the main advantage of the Z-Regret principle in both approaches—namely, the consideration of not only outcomes but also the degree of reliability.

Since Approach 1 takes into account both the evaluation (A) and its reliability (B), the selection of Facebook is explained by its ability to provide more reliable results precisely in the Normal Condition scenario. In practical terms, this means that the algorithm filters out manipulated or unreliable indicators, thereby enabling more resilient decision-making.

Approach 2, however, weakened the B component due to the transformation of Z-numbers first into fuzzy and then into crisp values. For this reason, the superiority of Facebook was justified in the Seasonal Variation scenario based on its more stable performance indicators.

This comparison shows that the Z-Regret principle not only identifies the optimal alternative but also reveals its resilience profile under different scenarios. This feature is critically important in practical management, especially in fields such as digital advertising that are highly vulnerable to manipulation.

9. Conclusions

In this study, for the first time, the regret principle has been extended with Z-numbers, and the Z-Regret principle has been formally proposed. The proposed model combines Savage’s classical minimax regret criterion with Zadeh’s Z-numbers, thereby allowing consideration of both the outcome (A) and the degree of reliability of information (B). This approach provides a basis for making decisions that are more well-founded and resilient under conditions of uncertainty.

The practical application conducted—namely, the evaluation of the performance of digital advertising platforms—has demonstrated that in both approaches the final choice was the Facebook (A₂) alternative. However, the underlying reasons for this selection differed:

Approach 1 (Z-Regret algorithm based on the closedness principle of Z-numbers) revealed that Facebook provided more reliable results in the Normal Condition scenario.

Approach 2 (Z-Regret algorithm based on the transformation of Z-numbers), on the other hand, showed that Facebook was superior under Seasonal Variation conditions due to its stable performance.

These results confirm that, while the classical regret principle relies solely on comparing evaluations, the Z-Regret principle enables more balanced and risk-resilient decision-making by considering both the evaluations themselves and their levels of reliability.

Theoretical Contributions:

The Z-Regret principle has been scientifically formalized for the first time.

In conducting regret calculations on Z-numbers, the importance of preserving the principle of closedness (i.e., the result of operations on Z-numbers must itself be a Z-number) has been demonstrated.

The comparison of two different approaches has substantiated the theoretical and practical advantages of incorporating the reliability factor.

Practical Contributions:

Companies can optimize their advertising strategies not only on the basis of nominal performance but also by considering the degree of reliability of the data.

In cases such as bot attacks and click fraud, the model based on the Z-Regret principle enables more resilient decision-making.

The analysis of results across scenarios allows managers to see not only the best alternative but also how that alternative behaves under different conditions.

Managerial Implications:

Managers can manage risks more effectively by paying attention not only to the magnitude of outcomes but also to their degree of reliability.

Considering different scenarios makes the selection of the optimal alternative more reliable and enhances the strategic sustainability of decisions.

Future Research:

The application of the Z-Regret principle can be explored in other uncertain environments such as financial markets, energy consumption, and healthcare.

For big data processing, computational optimization of algorithms developed under the Z-Regret principle should be carried out.

Comparing the Z-Regret principle with other multi-criteria methods such as Fuzzy-AHP, TOPSIS, and VIKOR can more clearly highlight its distinctions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A.; methodology, R.A.; software, V.S.; validation, R.A., V.S., and R.I.; formal analysis, R.A.; investigation, R.A. and R.I.; resources, R.A.; data curation, R.A. and V.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.A.; writing—review and editing, R.A., V.S., and R.I.; visualization, V.S.; supervision, R.A.; project administration, R.A.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors received no support from colleagues, institutions, or funding organizations for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MCDM |

Multi-Criteria Decision-Making |

| AHP |

Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| TOPSIS |

Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution |

| VIKOR |

VlseKriterijumska Optimizacija I Kompromisno Resenje (Compromise solution approach) |

| CTR |

Click-Through Rate (the ratio of clicks to impressions) |

| CPC |

Cost Per Click (the cost incurred for each click) |

| ROI |

Return on Investment (a measure of the profitability of an investment) |

References

- Bernoulli, D. Exposition of a new theory on the measurement of risk. Econometrica 1954, 22(1), 23–36. (Original work published 1738). [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J.; Morgenstern, O. Theory of Games and Economic Behavior; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1944; 625 pp.

- Savage, L.J. The Foundations of Statistics; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1954; 332 pp.

- Wald, A. Statistical Decision Functions; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1950; 179 pp.

- Hurwicz, L. Criterion for decision under uncertainty. Cowles Commission Discussion Paper, Statistics 1951, No. 355, 19 pp.

- Keeney, R.L.; Raiffa, H. Decisions with Multiple Objectives: Preferences and Value Tradeoffs; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1976; 569 pp.

- Saaty, T.L. The Analytic Hierarchy Process; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1980; 287 pp.

- Hwang, C.-L.; Yoon, K. Multiple Attribute Decision Making: Methods and Applications; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1981; 259 pp.

- Arrow, K.J. Social Choice and Individual Values; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1951; 124 pp.

- Gibbard, A. Manipulation of voting schemes. Econometrica 1973, 41(4), 587–601. [CrossRef]

- Satterthwaite, M. Strategy-proofness and Arrow’s conditions. J. Econ. Theory 1975, 10(2), 187–217. [CrossRef]

- Nash, J. Equilibrium points in n-person games. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1950, 36(1), 48–49. [CrossRef]

- Nash, J. Non-cooperative games. Ann. Math. 1951, 54(2), 286–295. [CrossRef]

- Harsanyi, J.C. Games with Incomplete Information; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1967; 3 vols., 1074 pp.

- Selten, R. Spieltheoretische Behandlung eines Oligopolmodells mit Nachfrageträgheit. Z. Gesamte Staatswiss. 1965, 121(2), 301–324.

- Simon, H.A. A behavioral model of rational choice. Q. J. Econ. 1955, 69(1), 99–118. [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 1979, 47(2), 263–291. [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy sets. Inf. Control 1965, 8(3), 338–353. [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. A note on Z-numbers. Inf. Sci. 2011, 181(14), 2923–2932. [CrossRef]

- Dubois, D.; Prade, H. Possibility Theory: An Approach to Computerized Processing of Uncertainty; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988; 263 pp.

- Shafer, G. A Mathematical Theory of Evidence; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1976; 297 pp.

- Atanassov, K. Intuitionistic fuzzy sets. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1986, 20(1), 87–96. [CrossRef]

- Aliev, R.A. Fundamentals of the Fuzzy Logic-Based Generalized Theory of Decisions; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013; 259 pp.

- Li, H.; Chatterjee, P. Designing online banner advertisements: The role of cognitive style. J. Advert. 2010, 39(1), 109–124. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Gupta, S. Conceptualizing the evolution and future of advertising. J. Advert. 2016, 45(3), 302–317. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.; Grier, C.; Song, D.; Paxson, V. Suspended accounts in retrospect: An analysis of Twitter spam. In Proceedings of the Internet Measurement Conference (IMC 2011), Berlin, Germany, 2–4 November 2011; pp. 243–258. [CrossRef]

- Haddadi, H. Fighting online click-fraud using bluff ads. ACM SIGCOMM Comput. Commun. Rev. 2010, 40(2), 21–25. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; et al. Seasonal advertising and consumer behavior. Mark. Sci. 2019, 38(4), 601–618. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Luo, X.; Chintagunta, P. Measuring the effectiveness of TikTok advertising. J. Mark. Res. 2021, 58(6), 1124–1141. [CrossRef]

- Chaffey, D.; Ellis-Chadwick, F. Digital Marketing; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2019; 728 pp.

- Liao, H. A survey on Z-number-based decision analysis methods and applications. Inf. Sci. 2024, 665, Article 119908, 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. A group decision making approach with Z-numbers based on correlation of multiple attributes. ACM Trans. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2024, 15(2), Article 11, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Wu, J.; Zhang, L. A new decision-making method based on Z-DEMATEL and maximal entropy OWA operator. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, Article 978767, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Alam, N.M.F.H.; Badrul, H. The application of Z-numbers in fuzzy decision making. Information 2023, 14(7), Article 400, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Chen, Y. A spherical Z-number multi-attribute group decision making model. Complex Intell. Syst. 2024, 10, 153–170. [CrossRef]

- Alam, N.M.F.H. Synergic ranking of fuzzy Z-numbers based on vectorial distance and spread for application in decision-making. AIMS Math. 2023, 8(10), 22620–22644. [CrossRef]

- Trung, N.Q.; Phong, T.D. Evaluation of digital marketing technologies with spherical fuzzy MCDM (SF-AHP & TOPSIS). Axioms 2022, 11(5), Article 230, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Lamrani Alaoui, Y.; El Fazziki, A.; Ouzzif, M. A hybrid fuzzy decision-making framework for technology selection. SN Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, Article 229, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Kuppusamy, V.; Narayanasamy, S. Bipolarity in multi-criteria decision-making for digital marketing. Heliyon 2024, 10(2), e26227, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Aliev, R.A.; Huseynov, O.H.; Aliyev, R.R.; Alizadeh, A.A. The Arithmetic of Z-Numbers: Theory and Applications; World Scientific Publishing: Singapore, 2015; 316 pp. [CrossRef]

- Aliyev, R.R. Similarity-based multi-attribute decision making under Z-information. In Multi-Attribute Decision Making under Z-Information; b-Quadrat Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 33–39.

- Wang, Y.J.; Lee, H.S. The revised method of ranking fuzzy numbers with an area between the centroid and the original point. Comput. Math. Appl. 2008, 55(9), 2033–2042. [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Wei, D.; Li, Y.; Deng, Y. A method of converting Z-number to classical fuzzy number. J. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2012, 9(3), 703–709.

- Van Laarhoven, P.J.M.; Pedrycz, W. A fuzzy extension of Saaty’s priority theory. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1983, 11(1–3), 229–241. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.T. Extensions of the TOPSIS for group decision-making under fuzzy environment. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2000, 114(1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Balashirin, A.R. The use of Z-numbers to assess the level of motivation of employees, taking into account non-formalized motivational factors. In Intelligent and Fuzzy Systems, INFUS 2023; Kahraman, C., Sari, I.U., Oztaysi, B., Cebi, S., Cevik Onar, S., Tolga, A.Ç., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; LNNS 758, pp. 471–482. [CrossRef]

- Alekperov, R. Using fuzzy Z-numbers when processing flexible queries. In Intelligent and Fuzzy Systems, INFUS 2022; Kahraman, C., Tolga, A.C., Cevik Onar, S., Cebi, S., Oztaysi, B., Sari, I.U., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; LNNS 504, pp. 435–444. [CrossRef]

- Balashirin, A.R.; Togrul, S.T. Detecting anomalies in data using Z-numbers. In Intelligent and Fuzzy Systems, INFUS 2024; Kahraman, C., Cevik Onar, S., Cebi, S., Oztaysi, B., Tolga, A.C., Sari, I.U., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; LNNS 1089, pp. 96–106. [CrossRef]

- Balashirin, A.R.; Togrul, S.T.; Mikayilova, R. Detection of anomalies in the energy consumption system by soft-computing methods. In Intelligent and Fuzzy Systems, INFUS 2025; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 791–798. [CrossRef]

- Alekperov, R.; Mikayilova, R.; Shukurova, S. An approach to assessing the level of development of enterprises in order to introduce convergent technologies based on Z-numbers. In Theory and Applications of Fuzzy Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Nuriyev, M.; Nuriyev, A.; Mammadov, J. Application of the Z-information-based scenarios for energy transition policy development. Energies 2025, 18(6), 1437. [CrossRef]

- Nuriyev, M.; Nuriyev, A.; Mammadov, J. Renewable energy transition task solution for the oil countries using scenario-driven fuzzy multiple-criteria decision-making models: The case of Azerbaijan. Energies 2023, 16(24), 8068:1–22. [CrossRef]

- Ramiz, A. The method of ranking business processes on weaknesses based on the theory of fuzzy sets. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent and Fuzzy Systems, 2022; pp. 128–134. [CrossRef]

- Mikayilova, R.; Alekperov, R. Method for diagnostics and selection of the type of market structure of commodity markets based on fuzzy set theory. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Theory and Application of Soft Computing, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Mikayilova, R.; Alekperov, R. Determination of the level of development of commodity markets by segmentation of economic regions based on the theory of fuzzy sets. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent and Fuzzy Systems, 2021; pp. 121–128. [CrossRef]

- Balashirin, A.R.; Tarlan, I.I. Application of neural networks for segmentation of catering services market within the overall system of consumer market on the model of restaurant business with the aim to advance the efficiency of marketing policy. In 13th International Conference on Theory and Application of Fuzzy Systems and Soft Computing—ICAFS-2018; Aliev, R., Kacprzyk, J., Pedrycz, W., Jamshidi, M., Sadikoglu, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; AISC 896, pp. 1285–1292. [CrossRef]

- Kilic, K.; Abdullayev, T.; Alakbarov, R.; Kilic, N. Processing of fuzzy queries and software implementation to a relational database of wholesale and retail commercial enterprises. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 102, 490–494.

- Zadeh, L.A.; Aliev, R.A. Fuzzy Logic Theory and Applications: Part I and Part II; World Scientific Publishing: Singapore, 2018; 612 pp. ISBN 9789813238190.

Figure 1.

Membership functions of triangular (a) and trapezoidal (b) fuzzy numbers.

Figure 1.

Membership functions of triangular (a) and trapezoidal (b) fuzzy numbers.

Figure 2.

Maximum regret distances (Approach 1).

Figure 2.

Maximum regret distances (Approach 1).

Figure 3.

A graphical representation of the regret matrix (Approach 2).

Figure 3.

A graphical representation of the regret matrix (Approach 2).

Figure 4.

Comparative analysis of the results obtained from Approach 1 and Approach 2.

Figure 4.

Comparative analysis of the results obtained from Approach 1 and Approach 2.

Table 1.

Comparison of classical numbers, fuzzy numbers, and Z-Numbers in terms of outcomes, reliability, and uncertainty.

Table 1.

Comparison of classical numbers, fuzzy numbers, and Z-Numbers in terms of outcomes, reliability, and uncertainty.

| Model |

Evaluation |

Reliability |

Level of Uncertainty |

| Classical numbers |

Crisp, deterministic value |

Assumed to be fully reliable (implicit = 1) |

No uncertainty (only exact outcomes) |

| Fuzzy numbers |

Fuzzy evaluation with membership values |

Not explicitly represented |

Models vagueness and imprecision |

| Z-numbers |

Fuzzy evaluation () |

Reliability component (B), fuzzy or probabilistic |

Models both uncertainty and reliability |

Table 2.

Execution of the subtraction operation on Z-numbers.

Table 2.

Execution of the subtraction operation on Z-numbers.

| Step |

The steps in the table are prepared based on [41,58] |

|

Explanation |

| 1 |

|

The component |

The fuzzy component A is calculated in accordance with the subtraction operation of fuzzy numbers |

| 2 |

|

Intermediate stage (for analysis) |

The subtraction is calculated based on the distribution functions. This step is used in the computation process of the reliability component B |

| 3 |

(11.3) |

An intermediate step for computing through

|

For the computation of the reliability function, the fuzzy and probabilistic components are bined |

| 4 |

(11.4) |

The component

|

As a result, the membership function of the B-component is obtained |

| 5 |

(11.5) |

Calculation of the elements of |

This is solved as a linear programming problem:

here |

| 6 |

(11.6) |

The condition for ensuring the consistency of the reliability component (the requirement that the and components are not contradictory to each other) |

|

| Final result |

|

Equation (11) |

As can be seen is also a Z-number. This fully corresponds to the closure property of Z-numbers

|

Table 3.

A Z-number-based utility matrix.

Table 3.

A Z-number-based utility matrix.

| Alternatives / Scenarios |

|

|

... |

|

|

|

|

... |

|

|

|

|

... |

|

| ... |

... |

... |

... |

... |

|

|

|

... |

|

Table 4.

Z-Regret Matrix (Approach 1).

Table 4.

Z-Regret Matrix (Approach 1).

| Alternatives / Scenarios |

s₁ |

s₂ |

… |

|

| a₁ |

|

|

… |

|

| a₂ |

|

|

… |

|

| … |

… |

… |

… |

… |

|

|

|

… |

|

Table 5.

A Z-number-based utility matrix (Approach 2).

Table 5.

A Z-number-based utility matrix (Approach 2).

| Alternatives / Scenarios |

|

|

... |

|

|

|

|

... |

|

|

|

|

... |

|

| ... |

... |

... |

... |

... |

|

|

|

... |

|

Table 6.

Wang ranking matrix.

Table 6.

Wang ranking matrix.

| Alternatives / Scenarios |

|

|

... |

|

|

|

|

... |

|

|

|

|

... |

|

| ... |

... |

... |

... |

... |

|

|

|

... |

|

Table 7.

The decision matrix. Initial performance evaluations of advertising platforms (Google, Facebook, TikTok) expressed as Z-Numbers under three scenarios.

Table 7.

The decision matrix. Initial performance evaluations of advertising platforms (Google, Facebook, TikTok) expressed as Z-Numbers under three scenarios.

| Alternatives / Scenarios |

S₁: Normal |

S₂: Bot Attack |

S₃: Seasonal Variation |

| A₁ (Google) |

= A: Very high → [70,75,85,90]

B: Full certainty → [0.95,1.00,1.00,1.00] |

= A: Low → [45,55,60] B: Moderate certainty → [0.70,0.80,0.85,0.90] |

= A: High → [60,65,75,80]

B: High certainty → [0.85,0.90,0.95,1.00] |

| A₂ (Facebook) |

= A: High → [65,70,80,85]

B: High certainty → [0.85,0.90,0.95,1.00] |

= A: Medium → [50,55,65,70] B: Moderate certainty → [0.70,0.80,0.85,0.90] |

=A: Medium → [55,60,70,75] B: Moderate certainty → [0.70,0.80,0.85,0.90] |

| A₃ (TikTok) |

= A: High → [60,65,75,80]

B: Moderate certainty → [0.70,0.80,0.85,0.90] |

= A: Low → [45,50,60,65] B: Moderate certainty → [0.70,0.80,0.85,0.90] |

=A: Medium → [50,55,65,70] B: Moderate certainty → [0.70,0.80,0.85,0.90] |

Table 8.

Maximum Z-numbers for each scenario obtained by applying Approach 1.

Table 8.

Maximum Z-numbers for each scenario obtained by applying Approach 1.

| Scenarios |

|

|

|

The minimum distance |

|

|

|

Normal Conditions |

40.00 |

50.125 |

60.35 |

40.00 |

|

|

|

-

|

100.35 |

80.35 |

90.35 |

80.35 |

|

|

|

- Seasonal Variation |

60.125 |

70.35 |

80.35 |

60.125 |

|

|

Table 9.

Regret matrix of alternatives under different scenarios (Approach 1).

Table 9.

Regret matrix of alternatives under different scenarios (Approach 1).

| Alternatives / Scenarios |

S₁: Normal |

S₂: Bot Attack |

S₃: - Seasonal Variation |

| A₁ (Google) |

= {[-20,-10,10,20], [0.92,1.00,1.00,1.00]} |

= { [-10,0,20,30] , [0.60,0.71,0.77,0.84] |

= {[-20,-10,10,20], [0.77,0.84,0.91,1.00]} |

| A₂ (Facebook) |

= {[-15,-5,15,25],

[0.83,0.90,0.95,1.00]} |

= {[-20,-10,10,20], [0.60,0.71,0.77,0.84]} |

={ [-15,-5,15,25], [0.66,0.76,0.82,0.90] |

| A₃ (TikTok) |

= { [-10,0,20,30],

[0.57,0.70,0.75,0.81] |

={[-15,5,15,25], [0.60,0.71,0.77,0.84] |

={ [-10,0,20,30], [0.66,0.76,0.82,0.90] |

Table 10.

Maximum regret distances for alternatives under Normal, Bot Attack, and Seasonal scenarios (Approach 1).

Table 10.

Maximum regret distances for alternatives under Normal, Bot Attack, and Seasonal scenarios (Approach 1).

| Scenarios |

|

|

|

The minimum distance |

|

|

| A₁ (Google) |

75.00 |

70.10 |

115.46 |

70.10 |

|

|

| A₂ (Facebook) |

100.35 |

105.35 |

110.35 |

100.35 |

|

|

| A₃ (TikTok) |

95.04 |

105.29 |

115.29 |

95.04 |

|

|

Table 11.

Ranking of alternatives based on Z-Regret principle (Approach 1).

Table 11.

Ranking of alternatives based on Z-Regret principle (Approach 1).

| The maximum Z-number |

|

The ranks |

|

70.10 |

-

|

|

95.04 |

-

|

|

105.35 |

-

|

Table 12.

Transformation of the Z-numbers specified for each alternative and scenario (

Table 7) into classical fuzzy numbers (Approach 2).

Table 12.

Transformation of the Z-numbers specified for each alternative and scenario (

Table 7) into classical fuzzy numbers (Approach 2).

| Alternatives / Scenarios |

S₁: Normal |

S₂: Bot Attack |

S₃: Seasonal Variation |

| A₁ (Google) |

α = 0.9833

= [69.41, 74.37, 84.29, 89.25] |

α = 0.8125

= [36.08, 40.59, 49.87, 54.38] |

α = 0.9250

=[57.05, 61.76, 71.37, 76.18]

|

| A₂ (Facebook) |

α = 0.9250

= [62.52, 67.33, 76.94, 81.76]

|

α = 0.8125

= [45.15, 49.66, 58.94, 63.45]

|

α = 0.8125

=[49.75, 54.27, 63.32, 67.84]

|

| A₃ (TikTok) |

α = 0.8100

= [54.00, 58.50, 67.50, 72.00] |

α = 0.8125

= [41.41, 46.01, 55.29, 59.89]

|

α = 0.8125

=[45.23, 49.75, 58.81, 63.33]

|

Table 13.

The results obtained from the ranking assessment of fuzzy numbers by applying the Wang method (Approach 2).

Table 13.

The results obtained from the ranking assessment of fuzzy numbers by applying the Wang method (Approach 2).

| Alternatives / Scenarios |

S₁: Normal |

S₂: Bot Attack |

S₃: Seasonal Variation |

| A₁ (Google) |

Centroid: (x0,y0)=(79.33, 0.5)

Wang Rank: R()= R()=79.58 |

Centroid: (x0,y0)=( 52.92, 0.5)

Wang Rank: R()= R()=53.17

|

Centroid: (x0,y0)=( 74.58, 0.5)

Wang Rank: R()= R()= 74.83 |

| A₂ (Facebook) |

Centroid: (x0,y0)=( 80.15, 0.5)

Wang Rank: R()= R()=80.40

|

Centroid: (x0,y0)=( 61.99, 0.5)

Wang Rank: R()= R()= 62.24 |

Centroid: (x0,y0)=( 66.34, 0.5)

Wang Rank: R()= R()= 66.59 |

| A₃ (TikTok) |

Centroid: (x0,y0)=( 70.50, 0.5)

Wang Rank: R()= R()=70.75

|

Centroid: (x0,y0)=( 58.37, 0.5)

Wang Rank: R()= R()= 58.62

|

Centroid: (x0,y0)=( 61.83, 0.5)

Wang Rank: R()= R()= 62.08 |

Table 14.

Maximum values by scenarios (Approach 2).

Table 14.

Maximum values by scenarios (Approach 2).

| Scenarios |

Maximum values for the scenarios |

| S₁: Normal |

80.40 |

| S₂: Bot Attack |

62.24 |

| S₃: Seasonal Variation |

74.83 |

Table 15.

The regret matrix (Approach 2).

Table 15.

The regret matrix (Approach 2).

| Alternatives / Scenarios |

S₁: Normal |

S₂: Bot Attack |

S₃: Seasonal Variation |

Maximum Regrets |

| A₁ (Google) |

0.82 |

9.07 |

0.00 |

9.07 |

| A₂ (Facebook) |

0.00 |

0.00 |

8.24 |

8.24 |

| A₃ (TikTok) |

9.65 |

3.62 |

12.75 |

12.75 |

Table 16.

Final minimax ranking of alternatives under classical regret (Approach 2).

Table 16.

Final minimax ranking of alternatives under classical regret (Approach 2).

| Alternatives |

Maximum Regrets |

Scenarios |

The rankings |

| A₂ (Facebook) |

8.24 |

S₃- Seasonal Variation |

1 |

| A₁ (Google) |

9.07 |

S₂: Bot Attack |

2 |

| A₃ (TikTok) |

12.75 |

S₃- Seasonal Variation |

3 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).