1. Introduction

1.1. Burden of Chronic Lung Diseases

Chronic lung diseases (CLDs) encompass a wide spectrum of respiratory tract disorders and structural abnormalities—including emphysema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), interstitial lung disease (ILD), asthma, and cystic fibrosis—that substantially impair both quality of life and survival. The primary risk factors are tobacco smoking, environmental exposures, occupational hazards, genetic predisposition, and socioeconomic conditions [

1]. Over the last two decades, the global prevalence of CLDs has risen by nearly 40%, making chronic respiratory diseases the third leading cause of death worldwide, with more than 4 million annual deaths [

2]. Beyond mortality, CLDs impose an enormous socioeconomic burden through frequent hospitalizations, loss of work productivity, and long-term disability. This global health challenge highlights the urgent need for improved strategies to identify patients at risk of severe disease progression and to provide individualized therapeutic interventions [

3].

1.2. Long-Term Oxygen Therapy and the Need for Personalized Approach

For patients with advanced CLD and severe hypoxemia, long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) has been established as a cornerstone of care. Historical trials have shown that LTOT significantly prolongs survival in COPD patients when administered for at least 15 hours per day [

4,

5]. Its benefits also include improved exercise tolerance, reduced exacerbations, and enhanced health-related quality of life [

6,

7,

8]. However, more recent randomized controlled trials have revealed mixed outcomes in patients with moderate hypoxemia, suggesting that LTOT is not universally beneficial [

9]. This variability in treatment response underscores the limitations of uniform, “one-size-fits-all” criteria for oxygen prescription, such as the use of a fixed resting SpO₂ <88% threshold across all patient populations. Contemporary approaches in personalized medicine emphasize the identification of physiologic and functional biomarkers that more accurately capture inter-individual variability in disease progression and therapeutic response. Within this framework, pulmonary function test (PFT)–derived indices—particularly the diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO)—hold promise as refined markers for risk stratification, enabling more precise selection of patients who are most likely to benefit from LTOT

]10].

1.3. Pulmonary Function Tests and DLCO as Predictors of Personalized Outcomes

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) constitute the cornerstone of respiratory assessment in patients with suspected or established chronic lung disease [

5]. Traditionally, spirometry parameters such as forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV₁) and forced vital capacity (FVC) have been used to stage disease severity, monitor progression, and guide therapy [

11]. However, these measures alone do not adequately capture the complexity of gas exchange impairment or the heterogeneity of patient outcomes. In contrast, the diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) provides a direct measure of alveolar–capillary gas transfer efficiency, integrating information about alveolar surface area, membrane integrity, and pulmonary capillary blood volume. Reduced DLCO values have been consistently associated with hypoxemia, exercise intolerance, and adverse prognosis in conditions such as COPD and interstitial lung disease [

9]. Importantly, DLCO offers a physiologic parameter that may enhance individualized decision-making, serving as a precision marker to identify which patients are most likely to require supplemental oxygen and to derive survival benefit from LTOT. Embedding DLCO into clinical algorithms could therefore represent a pivotal step toward advancing personalized respiratory care [

12].

1.4. Knowledge Gaps and Rationale for the Present Study

Despite the widespread use of PFTs in clinical practice, their ability to predict long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) requirements remains insufficiently defined. Previous research has largely focused on arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis and exercise-based assessments such as the six-minute walk test (6MWT) as primary determinants for oxygen prescription [

4,

8]. However, these modalities may be influenced by transient physiologic fluctuations, test performance variability, and patient effort, limiting their reproducibility and applicability across diverse clinical settings. Furthermore, existing thresholds for oxygen initiation are largely derived from historical COPD trials, raising questions regarding their generalizability to broader chronic lung disease populations [

4,

5,

9].

In this context, DLCO emerges as a promising candidate biomarker, offering an objective and reproducible index of alveolar–capillary gas transfer that directly reflects disease pathophysiology. By identifying DLCO thresholds that predict LTOT requirement with high sensitivity and specificity, clinicians may be able to move toward precision-based oxygen therapy, optimizing resource allocation while improving patient outcomes. Importantly, to the best of our knowledge, no prior study has directly examined the predictive role of PFT parameters, particularly DLCO, in determining LTOT eligibility across a heterogeneous cohort of chronic lung disease patients.

1.5. Study Aim

The present study therefore sought to evaluate the predictive value of PFT indices—especially DLCO—in determining LTOT requirements among patients with chronic lung disease. We hypothesized that reduced DLCO would serve as an independent and clinically meaningful predictor of LTOT, supporting its integration into routine practice as part of a personalized medicine framework.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study is a retrospective observational study based on a review of existing medical records of patients being followed at the Pulmonary Institute of Rambam Health Care Campus. It is a cross-sectional study that examines the relationship between PFT results and the need for LTOT.

The only anticipated bias in this study is selection bias, as the included patients are exclusively those under follow-up at the Pulmonary Institute at Rambam Health Care Campus. The study excludes patients from other hospitals and those receiving only ambulatory follow-up.

2.2. Study Population

The study included 302 patients (males and females, aged 18 years and older) who underwent comprehensive pulmonary function testing between December 1, 2021, and December 1, 2023 and were followed at the Pulmonary Institute at Rambam Health Care Campus. Patients diagnosed with CLD were documented, with differentiation between those receiving LTOT and those who were not.

Exclusion criteria: Patients were excluded if their PFT was incomplete, particularly if gas diffusion measurements were missing or undocumented. Additionally, individuals with ambiguous or undocumented LTOT usage were not included. Furthermore, patients who underwent PFT for indications related to malignant or non-respiratory chronic conditions, rather than chronic lung disease, were excluded from the study.

Variables

Dependent variable: Home oxygen therapy usage (LTOT).

Independent variables: Gender, age, height, weight, respiratory comorbidities, smoking status, pack-years, FVC pred, FVC % pred, FVC, FEV₁ % pred, FEV₁ pred, FEV₁, FEV₁/FVC, RV pred, RV % pred, RV, TLC, TLC pred, TLC % pred, RV/TLC, DLCO(Hb)%, KCO(Hb)%.

2.3. Statistical Methods

Initially, statistical tests were conducted to compare the study groups- patients using LTOT versus those who were not. These tests aimed to determine whether there were significant demographic or clinical differences between the two groups.

Chi-Square Test, Fisher’s Exact Test: Conducted to compare categorical variables such as gender, smoking status, and comorbidities.

Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test: Used to compare continuous variables that are not normally distributed, such as FEV₁, FVC, TLC, DLCO, etc.

Subsequently, univariate and multivariate regression analyses were performed to identify pulmonary function indices that predict the need for LTOT.

Univariate Analysis: This method examined the association between each independent variable and LTOT use separately. It allowed for the identification of key variables that might influence the outcome, such as age, sex, and PFT values. Additionally, it helped identify potential confounders for further evaluation in the multivariate analysis.

Multivariate Logistic Regression: This method assessed the relative weight of each independent variable while controlling for confounders that could create spurious or exaggerated associations. By isolating the effect of each factor, it determined which PFT indices independently predict the need for LTOT, thereby providing insights into causal relationships.

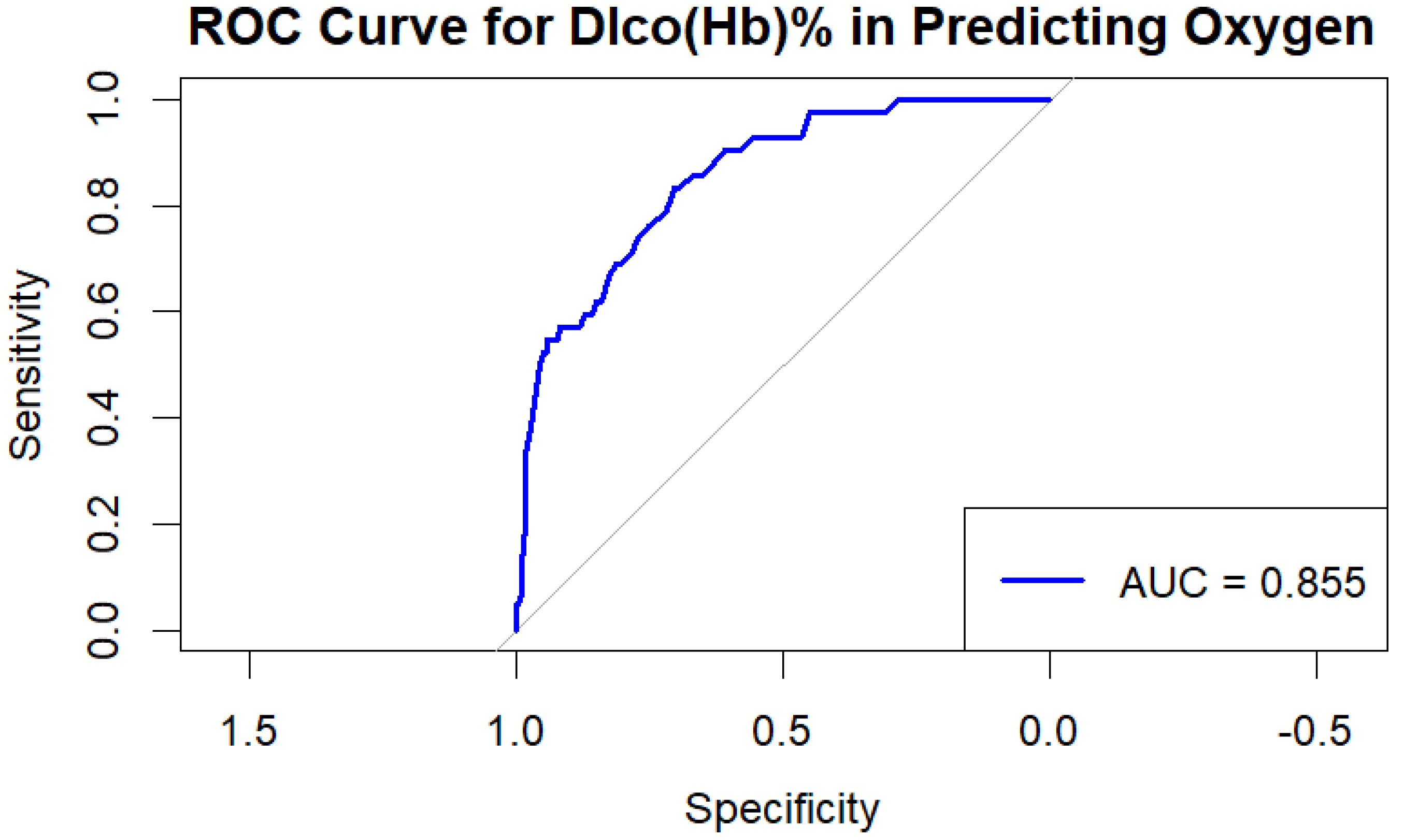

Additionally, a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve was generated to evaluate the performance of DLCO in predicting the need for oxygen therapy. This curve was used to present sensitivity versus 1-specificity for different DLCO thresholds and allowed for the identification of the optimal cutoff point that balances the correct identification of patients needing oxygen with the prevention of misclassification of those who do not require it.

Data analysis was conducted using R software version 4.2.1.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

Study approval was obtained from the Helsinki Committee of Rambam Health Care Campus. Patient data were anonymized and securely stored. No medical intervention was performed as part of the study; therefore, informed consent from the patients was not required.

3. Results/Observations

A total of 302 patients were included in the study. Among them, 42 patients (14%) required long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) while 260 (86%) did not.

The mean age of patients receiving LTOT was 74±9 years compared to 55±17 years in the non-LTOT group (p<0.0001). Male predominance was observed in both groups, with a significantly higher proportion in the LTOT group (79% vs. 56%, p=0.0005).

Regarding smoking history, 53% of the non-LTOT group had never smoked, while only 31% of LTOT recipients were never smokers (p=0.023).

Concerning respiratory diagnoses, COPD was more prevalent in the LTOT group (45%) versus the non-LTOT group (17%, p<0.0001). ILD was also significantly more frequent among LTOT patients (38% vs. 19%, p=0.0049). Sarcoidosis was less common in the LTOT group (2.4% vs. 15%, p=0.025).

PFT parameters demonstrated significant differences between groups:

FEV₁: 1.45 L in LTOT patients vs. 2.16 L in non-LTOT (p<0.0001)

FVC: 2.04 L vs. 2.84 L (p<0.0001)

TLC: 4.48 L vs. 5.13 L (p=0.004)

DLCO: 34% vs. 67% predicted (p<0.0001)

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population, stratified by LTOT requirement.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population, stratified by LTOT requirement.

| Characteristic |

No Home O2 therapy, N = 2601 |

Home O2 Therapy, N = 421 |

p-value2 |

| Age |

55 (46 – 69) |

74 (66 – 78) |

<0·0001 |

| Gender |

|

|

0·0053 |

| F |

115 (44%) |

9 (21%) |

|

| M |

145 (56%) |

33 (79%) |

|

| COPD |

44 (17%) |

19 (45%) |

<0·0001 |

| Emphysema |

14 (5·4%) |

1 (2·4%) |

0·70 |

| Mesothelioma |

1 (0·4%) |

0 (0%) |

>0·99 |

| Bronchiectasis |

15 (5·8%) |

3 (7·1%) |

0·72 |

| Bronchiolitis |

5 (1·9%) |

0 (0%) |

>0·99 |

| Amyloidosis |

1 (0·4%) |

0 (0%) |

>0·99 |

| Sarcoidosis |

39 (15%) |

1 (2·4%) |

0·025 |

| Mucinous CA |

1 (0·4%) |

0 (0%) |

>0·99 |

| Adeno CA |

21 (8·1%) |

4 (9·5%) |

0·76 |

| SQCC |

5 (1·9%) |

2 (4·8%) |

0·25 |

| SCLC |

6 (2·3%) |

0 (0%) |

>0·99 |

| NSCLC |

4 (1·5%) |

2 (4·8%) |

0·20 |

| ILD |

49 (19%) |

16 (38%) |

0·0049 |

| PH |

5 (1·9%) |

3 (7·1%) |

0·085 |

| LAM |

3 (1·2%) |

0 (0%) |

>0·99 |

| Asthma |

27 (10%) |

1 (2·4%) |

0·15 |

| Post COVID |

13 (5·0%) |

3 (7·1%) |

0·47 |

| Scleroderma |

10 (3·8%) |

0 (0%) |

0·37 |

| Pleural effusion |

2 (0·8%) |

0 (0%) |

>0·99 |

| GVHD |

10 (3·8%) |

0 (0%) |

0·37 |

| Silicosis |

3 (1·2%) |

0 (0%) |

>0·99 |

| PCD |

2 (0·8%) |

1 (2·4%) |

0·36 |

| OSA |

2 (0·8%) |

1 (2·4%) |

0·36 |

| CF |

1 (0·4%) |

0 (0%) |

>0·99 |

| LCH |

2 (0·8%) |

0 (0%) |

>0·99 |

| Non_specific |

12 (4·6%) |

0 (0%) |

0·38 |

| Height |

167 (159 – 173) |

168 (163 – 173) |

0·48 |

| Weight |

74 (62 – 85) |

78 (65 – 88) |

0·42 |

| FVC |

2·84 (2·16 – 3·40) |

2·04 (1·49 – 2·40) |

<0·0001 |

| FEV1 |

2·16 (1·69 – 2·71) |

1·45 (1·05 – 1·86) |

<0·0001 |

| FEV1/FVC |

0·81 (0·74 – 0·86) |

0·80 (0·71 – 0·86) |

0·32 |

| TLC |

5·13 (4·31 – 6·00) |

4·48 (3·52 – 5·36) |

0·0042 |

| RV |

2·23 (1·83 – 2·77) |

2·27 (1·63 – 3·35) |

0·61 |

| RV/TLC |

0·44 (0·38 – 0·52) |

0·54 (0·49 – 0·61) |

<0·0001 |

| Dlco(Hb)% |

67 (53 – 81) |

34 (27 – 52) |

<0·0001 |

| Kco(Hb)% |

91 (76 – 108) |

68 (50 – 85) |

<0·0001 |

| Unknown |

1 |

0 |

|

| Smoking |

|

|

0·023 |

| Current |

41 (16%) |

11 (26%) |

|

| Never |

139 (53%) |

13 (31%) |

|

| Past |

80 (31%) |

18 (43%) |

|

| PY |

30 (20 – 40) |

40 (30 – 50) |

0·0018 |

| Unknown |

163 |

16 |

|

In the univariate regression analysis, COPD and ILD were significantly associated with LTOT requirement, with COPD increasing the odds by 4.06-fold (p<0.0001) and ILD by 2.65-fold (p=0.0061). Decreased FEV₁ and DLCO were also significant predictors of LTOT use (p<0.0001).

Table 2.

Univariate logistic regression analysis for factors associated with LTOT requirement.

Table 2.

Univariate logistic regression analysis for factors associated with LTOT requirement.

| Characteristic |

OR1 |

p-value |

| Age |

1·05 |

0·0001 |

| M |

2·91 |

0·0071 |

| COPD |

4·06 |

<0·0001 |

| ILD |

2·65 |

0·0061 |

| FVC |

0·28 |

<0·0001 |

| FEV1 |

0·20 |

<0·0001 |

| FEV1/FVC |

0·10 |

0·066 |

| TLC |

0·69 |

0·0065 |

| RV |

1·34 |

0·094 |

| RV/TLC |

1 502 |

<0·0001 |

| Dlco(Hb)% |

0·92 |

<0·0001 |

| Kco(Hb)% |

0·97 |

<0·0001 |

| Smoking |

|

|

| Never |

0·35 |

0·018 |

The multivariate regression model confirmed that DLCO remained the strongest independent predictor of LTOT need (p=0.029). A 10% reduction in DLCO was associated with a 5% increase in the probability of requiring LTOT.

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression model identifying independent predictors of LTOT requirement.

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression model identifying independent predictors of LTOT requirement.

| Characteristic |

Crude OR |

95% CI Lower |

95% CI Upper |

P-value |

| Age |

1.02 |

1.00 |

1.05 |

0.11 |

| Gender (M) |

11.02 |

3.00 |

44.70 |

0.0005 |

| COPD |

1.48 |

0.43 |

4.95 |

0.53 |

| ILD |

1.30 |

0.39 |

4.06 |

0.67 |

| FVC |

1.20 |

0.17 |

8.17 |

0.86 |

| FEV1 |

0.30 |

0.05 |

1.88 |

0.20 |

| TLC |

0.58 |

0.25 |

1.08 |

0.17 |

| RV/TLC |

3.67 |

0.003 |

7331.97 |

0.72 |

| Dlco(Hb)% |

0.95 |

0.91 |

0.99 |

0.029 |

| Kco(Hb)% |

1.00 |

0.97 |

1.02 |

0.71 |

| Smoking (Never) |

0.61 |

0.14 |

2.64 |

0.50 |

| Smoking (Past) |

0.43 |

0.12 |

1.45 |

0.17 |

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis demonstrated high discriminative power for DLCO in predicting LTOT requirement, with an AUC of 0.855.

Figure 1.

ROC curve demonstrating the predictive value of DLCO for the need for long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) in patients with chronic lung disease (AUC = 0.855).

Figure 1.

ROC curve demonstrating the predictive value of DLCO for the need for long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) in patients with chronic lung disease (AUC = 0.855).

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Results

The present study identifies diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) as the strongest and most consistent independent predictor of long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) requirement in patients with chronic lung disease (CLD). In our cohort, a DLCO value below 39% was associated with a 90% probability of requiring LTOT, whereas values above 60% reliably excluded LTOT need. The discriminative performance of DLCO, as reflected by the ROC curve (AUC = 0.855), surpassed that of traditional spirometric indices such as FEV₁ and FVC. These findings suggest that DLCO, beyond its established role in assessing gas exchange efficiency, may serve as a clinically relevant biomarker for oxygen prescription.

4.2. Comparison to Previous Studies

Our results align with earlier pivotal studies demonstrating the clinical benefit of LTOT in patients with severe hypoxemia [

4,

5,

11,

12]. However, more recent randomized trials in patients with moderate desaturation reported no significant survival or quality-of-life advantage [

9]. This discrepancy highlights the heterogeneity of LTOT outcomes and emphasizes the need for improved patient selection criteria. Previous investigations have primarily relied on arterial blood gas (ABG) measurements or the six-minute walk test (6MWT) [

4,

8], but these tools are influenced by variability in patient performance and transient physiological changes. By contrast, DLCO offers a stable physiologic index directly linked to alveolar–capillary function, and our findings support its superior predictive value for LTOT eligibility across diverse CLD populations.

4.3. Implications for Personalized Medicine

The integration of DLCO into clinical decision-making frameworks represents a critical step toward personalized medicine in respiratory care. Unlike uniform thresholds (e.g., SpO₂ <88%) applied indiscriminately across patient groups, DLCO captures inter-individual differences in disease pathophysiology and prognosis. In line with contemporary precision medicine initiatives [

10], DLCO-based stratification could enable clinicians to identify patients most likely to benefit from LTOT while avoiding unnecessary treatment in others. Such an approach would optimize resource allocation, reduce patient burden, and enhance outcomes by ensuring that therapy is individualized rather than standardized. Our study therefore contributes to the growing body of evidence advocating for the incorporation of physiological biomarkers into tailored treatment algorithms for chronic lung disease [

12,

16].

4.4. Clinical and Research Implications

Clinically, incorporating DLCO thresholds into LTOT guidelines may refine current practice by providing an additional, evidence-based criterion for oxygen prescription. This approach may be particularly valuable in patients with borderline oxygen saturation or discordant clinical features, where decision-making is often uncertain. From a research perspective, future prospective multicenter trials should validate DLCO cutoffs across larger and more diverse populations, ideally incorporating longitudinal outcomes such as mortality, hospitalizations, and health-related quality of life. Additionally, combining DLCO with emerging biomarkers— such as imaging phenotypes or genomic signatures—could further enhance personalized prediction models for LTOT need.

4.5. Limitations

Several limitations of this study must be acknowledged. First, its retrospective, single-center design may limit generalizability. Second, potential selection bias exists, as only patients followed at our institution were included. Third, while DLCO demonstrated strong predictive performance, the possibility of residual confounding cannot be excluded, particularly regarding comorbidities and treatment histories. Finally, causality cannot be established given the observational design. Nevertheless, the robustness of DLCO across multivariate analyses underscores its potential clinical utility.

In summary, this study demonstrates that DLCO is a powerful, independent predictor of LTOT eligibility in patients with chronic lung disease. By integrating DLCO into oxygen therapy decision-making, clinicians can move closer to achieving the goals of personalized medicine—delivering the right therapy to the right patient at the right time. These findings support a paradigm shift from uniform thresholds toward individualized, physiology-based approaches in respiratory care.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) is a powerful and independent predictor of long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) requirement in patients with chronic lung disease. A DLCO below 39% was strongly associated with LTOT need, whereas values above 60% effectively excluded oxygen requirement, highlighting clinically relevant thresholds with immediate applicability. Compared with traditional spirometric indices, DLCO showed superior discriminative capacity, underscoring its potential as a precision tool for patient stratification. By moving beyond uniform saturation-based criteria, these findings support the integration of DLCO into personalized treatment algorithms, aligning oxygen prescription with individual physiologic profiles. Further prospective studies are warranted to validate these thresholds across larger and more diverse cohorts and to explore the additive value of combining DLCO with other biomarkers in advancing personalized respiratory care.

Abbreviations

| CLD |

Chronic lung disease |

| PFT |

Pulmonary function tests |

| LTOT |

Long-term oxygen therapy |

| DLCO |

Diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide |

| COPD |

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| ILD |

Interstitial lung disease |

| 6MWT |

Six-minute walk test |

| ABG |

Arterial blood gas |

| FRC |

Functional residual capacity |

References

- Labaki, W.W.; Han, M.K. Chronic respiratory diseases: a global view. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8(6), 531–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators. Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8(6), 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeloye D, Chua S, Lee C, et al. Global and regional estimates of COPD prevalence: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2015;5(2):020415. [CrossRef]

- Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial Group. Continuous or nocturnal oxygen therapy in hypoxemic chronic obstructive lung disease: a clinical trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 1980, 93, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medical Research Council Working Party. Long-term domiciliary oxygen therapy in chronic hypoxic cor pulmonale complicating chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Lancet 1981, 317(8222), 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koczulla, A.R.; Schneeberger, T.; Jarosch, I.; Kenn, K.; Gloeckl, R. Long-term oxygen therapy. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2018, 115(51–52), 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnussen, H.; Kirsten, A.M.; Köhler, D.; Morr, H.; Sitter, H.; Worth, H.; et al. Leitlinien zur Langzeit-Sauerstofftherapie. Pneumologie 2008, 62(12), 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, S.S.; Krishnan, J.A.; Lederer, D.J.; et al. Home oxygen therapy for adults with chronic lung disease: an official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 202(10), e121–e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, R.K.; Au, D.H.; Blackford, A.L.; et al. A Randomized Trial of Long-Term oxygen for COPD with Moderate Desaturation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375(17), 1617–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins FS, Varmus H. A new initiative on precision medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):793-795. [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, M.; Papi, A.; Contoli, M.; et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation fundamentals: diagnosis, treatment, prevention and disease impact. Respirology 2021, 26(6), 532–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celli BR, Wedzicha JA. Update on Clinical Aspects of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(13):1257-1266. [CrossRef]

- Al Wachami, N.; Guennouni, M.; Iderdar, Y.; et al. Estimating the global prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24(1), 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusen, R.D.; Criner, G.J.; Sternberg, A.L.; et al. The Long-Term Oxygen Treatment Trial for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: rationale, design, and lessons learned. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2018, 15(1), 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoller, J.K.; Panos, R.J.; Krachman, S.; Doherty, D.E.; Make, B. Oxygen therapy for patients with COPD: current evidence and the long-term oxygen treatment trial. Chest 2010, 138(1), 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everard ML. Challenging the paradigm. Breathe (Sheff). 2022;18(1):210148. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).