1. Introduction

The Collatz Conjecture asks whether every positive integer eventually reaches 1 under the iteration

Despite its elementary form, the conjecture has remained unresolved since 1937 and has resisted probabilistic, dynamical, algebraic, and computational approaches.

The essential difficulty is structural: forward trajectories mix multiplicative growth with aggressive dyadic contraction, while reverse trajectories branch infinitely through admissible preimages. No prior framework has simultaneously captured both behaviors in a closed, exhaustive arithmetic model.

This work develops such a model. Our approach is built from first principles and consists of three independent components that ultimately coincide:

A local residue–phase automaton describing all odd iterates by their class modulo 6 and their phase modulo 3, yielding a finite state space on which every admissible reverse step acts.

A

zero-state operator that isolates the intrinsic odd component of each number by removing its admissible dyadic factor. This produces a global index

and a child-determined affine ladder

whose union over all zero-state bases yields a disjoint affine partition of

.

-

A

dyadic slice decomposition, determined by the exponent

, which partitions the odd integers into the sets

Each slice has weight and the slices are disjoint with total measure 1.

A central result of this paper is that the affine ladders from the zero-state construction and the dyadic slices from coincide exactly. Thus the odd integers admit two independent but equivalent global parametrizations: one affine, one dyadic.

When combined with the

forward–reverse locked identity,

the global structure forces every forward trajectory into the unique affine ladder descending from its zero-state base. Since this base is always 1, and since the residue–phase automaton is finite, no forward runaway and no nontrivial odd cycle is possible.

All results, constructions, and structural decompositions presented here are original. Together they provide a complete arithmetic description of the Collatz dynamics and establish that every forward trajectory converges to 1.

We begin by establishing the fundamental definitions and notation used throughout the framework.

2. Definitions

Definition 2.1 (Classic Collatz function).

The classical Collatz map is defined by

Definition 2.2 (Forward Collatz function).

The complete-step (odd-to-odd) Collatz map is

where is the maximal exponent such that the denominator divides . Thus gives the next odd iterate of n under the Collatz process.

Definition 2.3 (Reverse Collatz function).

The complete-step reverse Collatz map assigns to each odd integer n its admissible parent via

where k is admissible if . If is the minimal admissible doubling count, then is called the first parent

of n.

Definition 2.4 (Middle-even values).

In the odd-to-odd formulation of the Collatz map, each step factors through an intermediate even value.

For the forward map

, given an odd integer n, the intermediate (middle-even) value is

For the reverse map

, given an odd integer n and an admissible doubling count (i.e. ), the intermediate (middle-even) value is

Both and are even and serve as the “middle” stage between odd inputs and odd outputs. Read modulo 18, these values determine the child’s odd class through the fixed gate , , in the reverse Collatz function.

Definition 2.5 (Parent (reverse Collatz function)).

An odd integer n is called aparent. If (that is, n is an odd multiple of 3), then it has no admissible doubling and is called a terminating parent . If or , then n isliveand admits some that is admissible.

Definition 2.6 (Child (reverse Collatz function)).

Given a parent n and an admissible , the corresponding child

is

For a fixed n, admissible k have fixed parity and are exactly

where ℓ is the lift index

counting successive admissible exponents above the minimal one. As k increases by , the middle-even residue cycles ; under the fixed gate , , , the children of n therefore occur in the deterministic class rotation

Definition 2.7 (First admissible child).

For any live odd integer , let denote its class-determined least admissible exponent. We define

and refer to as the first admissible child

of n.

Definition 2.8 (Admissible doubling and child).

Let n be odd. A doubling count isadmissible

if

For any admissible k, the reverse child

is

The set of admissible k for a fixed odd n has fixed parity (even if , odd if ), and hence preserves admissibility.

Definition 2.9 (Terminal and Live Classes).

Let . The Collatz class of n is defined as:

Class is terminal under Collatz iteration; classes and are live.

Definition 2.10 (Reset-and-Resume Function).

Given odd, define . Then the reset-and-resume transform is:

where denotes the 2-adic valuation of x. This is the only class-agnostic invariant rule under Collatz iteration.

Definition 2.11 (q-Transform Function).

The class-dependent q-transform for single-generation transitions is defined as:

Definition 2.12 (Progression index).

For an odd parent n, theprogression index

t is the integer parameter in the canonical forms

with . The index t counts the position of n within its mod-6 residue class. In later sections, offsets and ladders are expressed as explicit functions of this progression index.

Definition 2.13 (Admissible parent).

For odd , define to be the least positive integer k such that . If such k exists, set

If we say n is terminating.

Definition 2.14 (Admissible exponents).

For an odd integer n, the set of admissible exponents

is

(If , then .)

Definition 2.15 (Middle even and gate residue).

For odd m, set

so that is the odd Collatz child. The middle even

is

and its gate residue

is

Definition 2.16 (Forward odd-to-odd step).

For odd m, let and define

Definition 2.17 (Least-admissible reverse parent).

For odd m, let , where if and if . Work modulo 18 with live residues and dead residues . Write every odd as with and .

Definition 2.18 (Rail).

A rail

is the vertical affine progression generated from any odd value m by repeated admissible higher lifts. Each lift increases the exponent by and applies the transformation

Thus the rail through m is

Rails represent all values obtained from a fixed parent by higher-k lifts.

Definition 2.19 (Ladders as Dyadic Offset Progressions).

Fix a class and let be the admissible lift exponent. Every odd integer in this class can be written uniquely as

where t is the index of the element within its residue class. Applying the reverse map gives

The ladder at level

kis the arithmetic progression

whose consecutive elements differ by the fixed dyadic offset

Thus a ladder is the ordered progression of parents obtained from all sequential inputs under the same admissible exponent k.

3. The Deterministic Residue Framework

This section extends the local residue framework first developed in

A Deterministic Residue Framework for the Collatz Operator at [

1], together with earlier unpublished notes that identified the mod 9 residue cycle as the source of reverse determinism. The core construction is preserved: admissibility is fixed by residue classes modulo 6, while refinement to mod 9 and its canonical lift to mod 18 determines the child class at each step.

The result is a deterministic lens through which every odd integer is classified and every admissible step is resolved. This local structure now appears explicitly as the microscopic counterpart of the global coverage framework that follows.

3.1. The Mod 6 Classification for Odd Integers

All odd integers fall into three residue classes modulo 6:

-

C0: (odd multiples of 3: ).

Forward (middle-even identification): .

Reverse (admissibility/parity): No admissible k with exists, so has no reverse parent.

-

C1: (two higher than a multiple of 3: ).

Forward (middle-even identification): .

Reverse (admissibility/parity): , so admissible

k are

odd. The first admissible is

. One doubling gives

Since

for

, we have

; subtracting 1 yields a multiple of 3, so the reverse step is an integer. Thus

always resolves after

-

C2: (two lower than a multiple of 3: ).

Forward (middle-even identification):.

Reverse (admissibility/parity):, so admissible

k are

even. The first admissible is

, yielding

Since

for

, we have

; subtracting 1 yields a multiple of 3, so the reverse step is an integer. Thus

always resolves after

doublings.

Lemma 3.1 (C0 is terminating under the reverse step).

If (i.e., n is an odd multiple of 3), then for every ,

In particular, the class C0 has no admissible reverse child.

Proof. If then for all , hence , which is not divisible by 3. □

Interpretation. The mod-6 classification isolates the essential periodic structure of the Collatz map. Every odd integer is congruent to 1, 3, or 5 mod 6, producing three invariant classes. Multiples of 3 () are terminal because no admissible doubling can satisfy . The remaining residues 1 and 5 ( and ) are live: they alternate under the admissible-exponent rule and generate the entire forward–reverse lattice. Thus the three-class system is not arbitrary—it is the minimal periodic decomposition consistent with both the mod-3 condition and parity.

3.2. K-Value Admissibility of the Classes

This subsection identifies the admissible k values for each class and demonstrates how parity is determined by the residue of n modulo 3.

Lemma 3.2 (Admissibility parity).

Let n be an odd integer. The congruence

has a solution if and only if n is not divisible by 3. Moreover, the residue of n modulo 3 determines the parity of k:

Once one admissible k exists, every larger k with the same parity is also admissible.

Proof. C1 admissibility with

. For

we have

and

. The admissibility condition is

i.e.

Write

. Since

,

Substitute

n:

Note:

Therefore,

holds for all integers

t and all

.

This explicitly shows why every odd lift of the form

is admissible for

.

C2 admissibility with

. For

we have

and

. The admissibility condition is

i.e.

Write

. Since

,

Substitute

n:

Therefore,

holds for all integers

t and all

.

This explicitly shows why every even lift of the form is admissible for .

□

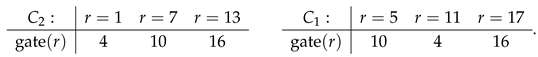

3.3. Mod 18 Gate and its Mod 9 Subclassification

This subsection establishes the deterministic mod 18 gate that decides the child class of every admissible parent. The residue of the middle-even value after the minimal admissible doubling lands in , and this uniquely determines the class of the first child.

Lemma 3.3 (Minimal admissible doubling and the mod 18 gate).

List the odd integers mod 18 in sequential order and, for each odd n, take its first child by the reverse Collatz function and using . Then the first-child classes follow a repeating nine-step cycle in sequence mod 3:

(where x denotes terminating parents, i.e. multiples of 3). In particular, the six odd non-multiples of 3 partition into two fixed triads

corresponding to and parents, respectively; thus mod 18 alone determines the child-class framework.

Moreover, let denote the minimal admissible exponent

for the reverse function

This minimal k is fixed by the class of n:

Applying the minimal admissible doubling directly to the residue gives the deterministic gate

Evaluating this for each residue yields the fixed gate assignment Thus the minimal admissible doubling maps each odd residue to a unique even gate in , refining the mod-9 triads to mod-18 gates.

Thus the minimal admissible doubling maps each odd residue to a unique even gate in , refining the mod-9 triads to mod-18 gates.

Proof. (i) Mod-9 triad partition. For odd n, write with . If then and the parent is terminating (). When , the residues split by into the two disjoint triads and , which correspond to and , respectively. The first-child map (apply then divide by 2 until odd) permutes elements within the appropriate triad and never crosses between them, yielding the stated nine-step cycle.

(ii)

Lift to mod-18 gates. Work modulo 18 and apply the minimal admissible doubling directly to the residue

r: for

use one factor of 4; for

use one factor of 2. This gives

which are precisely the even gates

claimed. □

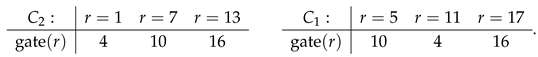

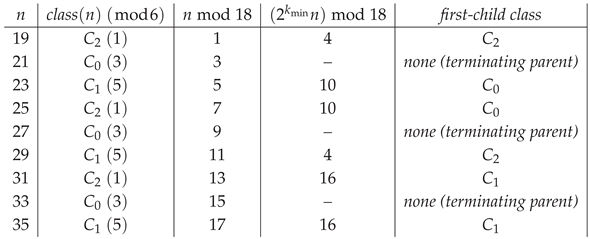

Corollary 3.4 (Linear segment pattern 19–35).

Listed are the odd integers n from 19 to 35. For each n, record its class (mod 6), its residue (mod 9) and (mod 18), the reverse middle-even at the minimal admissible doubling ( for , for , none for ), and the class of the first child

Explanation. For each n: determine its class by (C0: 3, C1: 5, C2: 1). If , no admissible reverse step exists. If (resp. ), take (resp. ) by admissibility parity. Then use the deterministic gate: with the fixed mapping . Evaluating these nine cases yields the displayed sequence . This finite segment is a repeating cycle. □

These nine odd residues partition into inadmissible and admissible parents:

Lemma 3.5 (Equidistribution of First-Child Classes).

Across every complete 18-residue cycle of odd parents, the first-child classes appear with exact frequency each.

Proof. By Corollary 3.4, the nine admissible residues modulo 18 yield the child-class sequence

where dashes denote terminating parents. Each 18-step cycle therefore contains precisely two occurrences of each live class, giving equal frequency

when restricted to

. □

Lemma 3.6 (Forward mod-6 lift to mod-18 at the first even).

Let n be odd and define the forward middle-even value . Then the residue of n modulo 6 determines modulo 18 via

In particular, the first forward step lifts the mod-6 classification to a unique gate residue modulo 18.

Proof. Write

with

. Then

since

. Direct evaluation gives

which proves the three implications and the uniqueness of the lifted gate residue. □

Proposition 3.7 (Deterministic child-class decision via mod 18).

In the Reverse Collatz function, and for odd n, the residue of the middle even in alone determines the child’s odd class, both in forward and reverse middle-even. This gives a one-step, local rule independent of trajectory history.

Lemma 3.8 (Middle-even equivalence mod 18).

If 3 does not divide n, then there exists an admissible such that

Proof.

Forward side (mod 6 lifted to mod 18). For odd

n, the forward middle-even value is

. Reducing

n modulo 6 and multiplying by 3 lifts the residue to mod 18:

so

always lies in

.

Reverse side (mod 18 determinism). For odd

n not divisible by 3, the residue

, together with the admissible parity of

(even if

, odd if

), selects exactly one of the two triads of units modulo 9:

Applying

places

n into the middle-even value that belongs to the nine-step cycle of Corollary 3.4. That middle-even value is already one of

, the forward gates. □

3.4. Microcycles and Lifted k with Tables

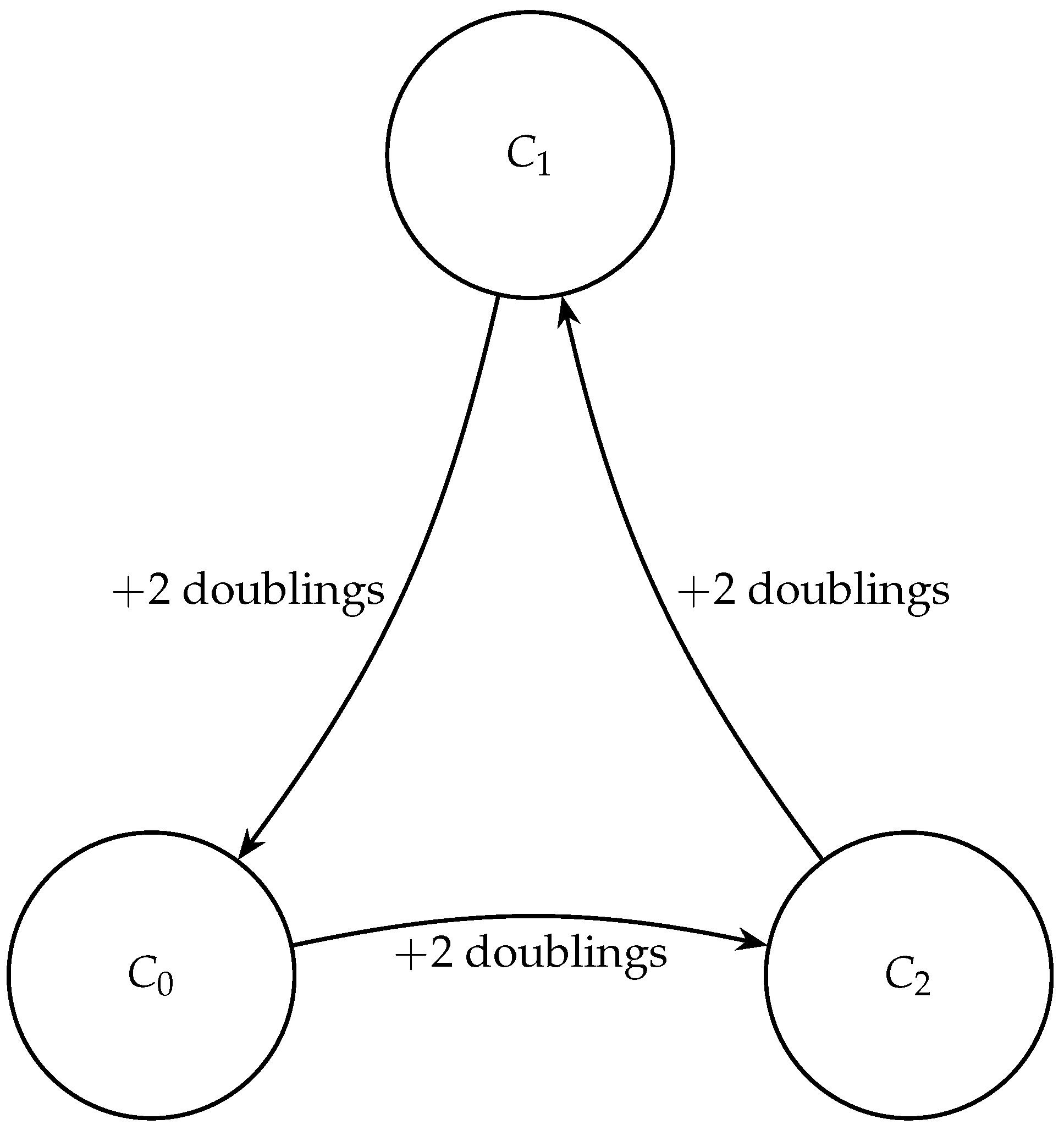

Lemma 3.9 (Rotation under

in mod 18).

If k is admissible for odd n (), then

Moreover , and hence

Proof. Admissible are even and , so only occur modulo 18. For admissible k, ; computing mod 18 gives , , , which establishes the 3-cycle. □

-

Microcycles: function and reason. Fix a live odd parent

n not divisible by 3. For the Reverse Collatz Function, all admissible reverse doublings for

n share the same parity (by admissibility parity), so from the minimal admissible count

we may advance by steps of 2:

. By Lemma 3.9, each

step multiplies the reverse middle-even by 4 modulo 18, sending

and hence rotating the child classes

.

cycling through

(mod 18). By the common mod-18 gate (Lemma 3.8), these three middle-even classes deterministically select the child odd classes

, in that order. Thus every fixed parent

n generates a

k-lifted microcycle of children:

(), in cyclic order beginning with the first admissible child, repeating every three steps. Moreover, by the forward–reverse middle-even equivalence (Lemma 3.8), there exists an admissible k for which , so the reverse microcycle is aligned with the residue one sees on the forward side.

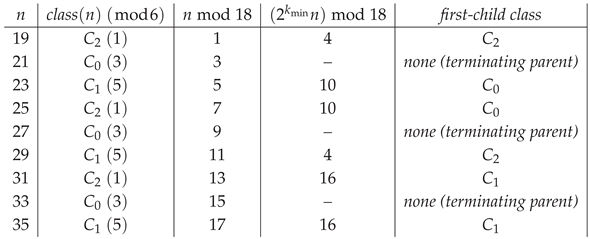

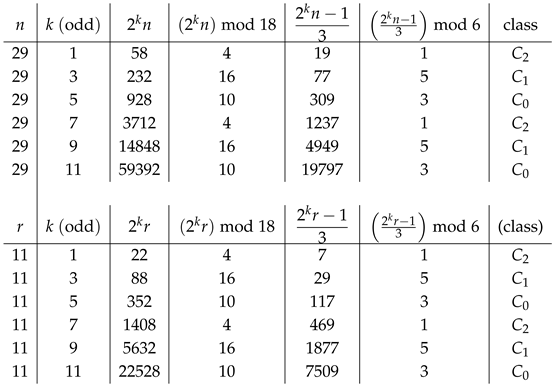

To display this mechanism explicitly, we present two parallel tables: (i) the integer view, which lists specific n and its children at each admissible lift, and (ii) the residue view, which reduces n to . Both views coincide in the mod-18 column and the resulting child class.

Reading across the rows of either table shows how each lift advances through the microcycle, and how every admissible parent reaches a residue within at most two steps, certifying an accessible termination to .

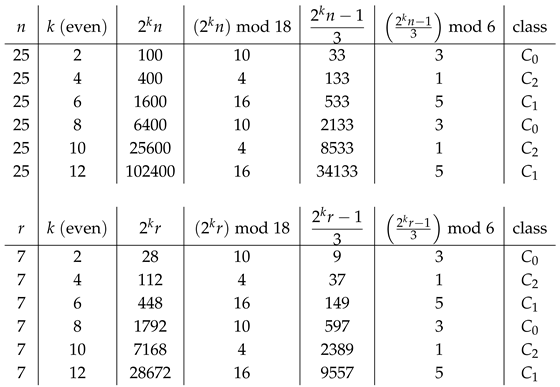

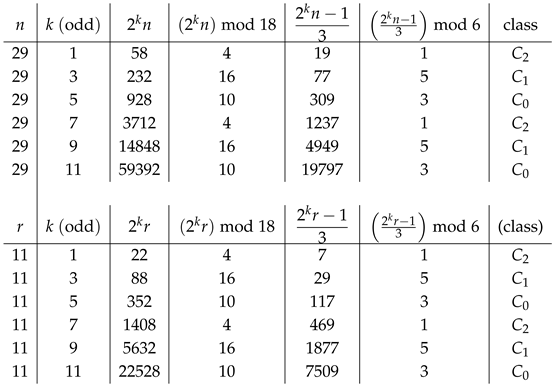

Example (reverse step, even k; here , ):

Example (reverse step, odd k; here , ):

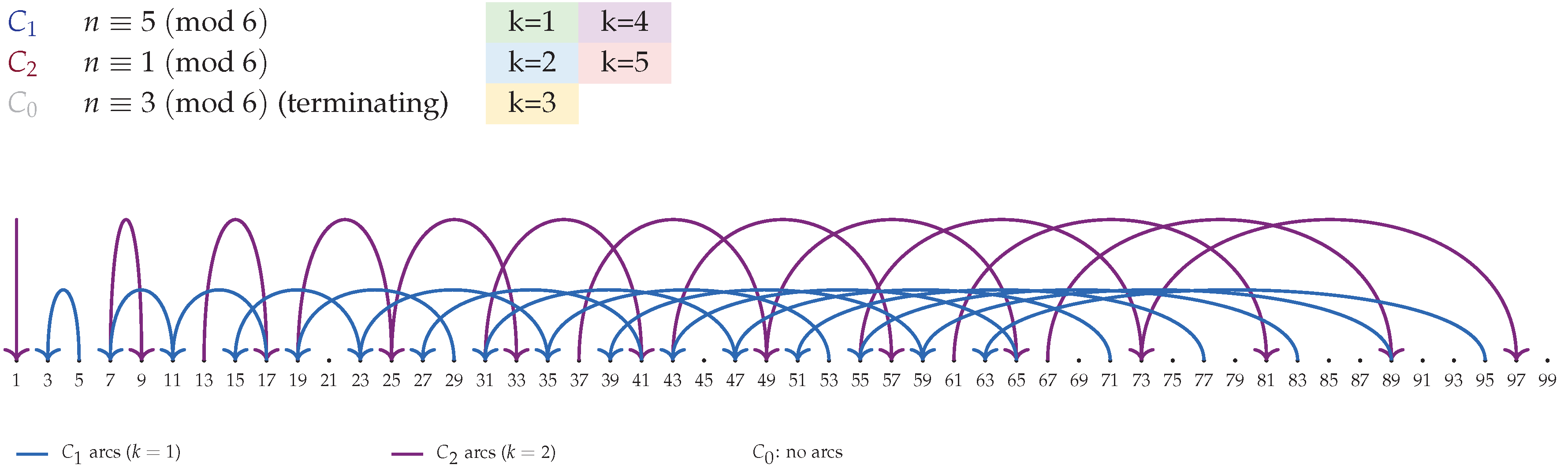

Figure 1.

Even-k rotation of child classes through the mod-18 gate. Each increment of two in k multiplies the middle-even residue by 4, producing the cycle . These residues correspond deterministically to classes (with , , ). Hence the child class rotates in the fixed order , making the terminating class periodically available alongside the live classes.

Figure 1.

Even-k rotation of child classes through the mod-18 gate. Each increment of two in k multiplies the middle-even residue by 4, producing the cycle . These residues correspond deterministically to classes (with , , ). Hence the child class rotates in the fixed order , making the terminating class periodically available alongside the live classes.

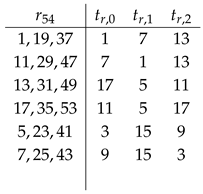

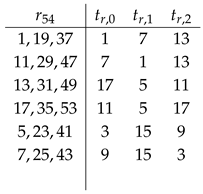

3.5. Mod 54 Refinement: Fixing the Child Residue

The mod-18 gate (Lemma 3.3, Proposition 3.7) determines the child class. Refining the lens to determines, already at the first admissible reverse step, the child’s odd residue modulo 18.

Write every live odd

n as

Set

. For each

, the corresponding residues in mod 54 are

Define the lifted triads

by

Each lifted triad row follows the same deterministic pattern as the mod 18 table. The indexing variable

plays the same role as

in selecting the correct column of the triad. Rows for

are in

or

, and

remain in

.

Lemma 3.10 (Mod 54 refinement fixes the child residue).

Let

Set . Then the first admissible reverse child of n has odd residue

where is determined by the lifted triad . Equivalently, the pair uniquely determines the child’s odd residue modulo 18.

Proof sketch. By Lemma 3.2, the minimal admissible exponent is odd for and even for . The mod 18 structure (Lemma 3.3) partitions the six live residues into deterministic triads, and the admissibility parity lifts each residue canonically to its gate (Proposition 3.7).

Passing to mod 54, each

splits into three residues

and the index

selects one of the three columns of the lifted triad table

. Evaluating the first admissible reverse step for

within each

reproduces exactly the triad outputs listed in

Table 1. Thus

completely determines the child residue modulo 18. □

Because

is completely determined by

, the mapping

is obtained by grouping the 27 live residues mod 54 into six blocks by

r and subdividing each block by

. For example, the block

contributes residues

in the order

. Explicitly listing all odd

produces a 54-entry table in which each row records

. We defer the full table to

Table 1 below for readability.

Corollary 3.11 (Periodicity of the Mod 54 Child Mapping).

Let n be an odd integer with

Let denote the residue modulo 18 of the first admissible reverse child of n,

Then for every integer (period index),

Equivalently, the mapping

is periodic with fundamental period 54. In particular, the table of first-child residues for odd repeats identically on each interval .

Interpretation. The refinement to modulus 54 resolves the residual ambiguity left by the mod-18 gate. At mod-18, each live residue determines only the class of its child; lifting to mod-54 records the phase of the quotient , which fixes the child’s exact odd residue mod 18. The resulting triads show that every parent residue generates three distinct child residues, one for each phase position. Because these triads repeat with period 54, the entire reverse map becomes periodic at that modular scale. This periodicity demonstrates that the residue–phase system is finite and deterministic: each pair has one unique successor, and every possible parent–child relationship repeats identically on successive 54-blocks.

Lemma 3.12 (Affine reverse update law).

Let with and , and set

Define

Then and the single–step update is given by

with the following explicit formulas:

-

1.

-

2.

(Residue update by phase)

-

3.

Consequently, the pair uniquely determines , and the next phase is computed from the affine form .

Corollary 3.13 (Finite Residue–Phase Automaton).

For each step of the reverse map defined by

the image depends only on through the valuation of . The quotient component evolves under the induced transformation

and defines a finite deterministic automaton on the space . The sequence obtained by successive iterations remains bounded within this finite set, generating locally deterministic residue–phase transitions.

Lemma 3.14 (Residue–Phase Transition and Reset–Resume Law).

Let with and as above. Then the following properties hold:

-

1.

For fixed r, as q varies modulo 3, the residues occupy three distinct elements of corresponding to the classes .

-

2.

The order of appearance of these residues is determined by r and the parity of , defining a locally unique orientation.

-

3.

For each iteration, the next phase and residue are re-evaluated from the resulting m, establishing a reset and resume transition of the form

where and .

The residue phase system thereby forms a finite deterministic automaton with terminal residues , transitional residues mapping into , and active residues forming the lattice .

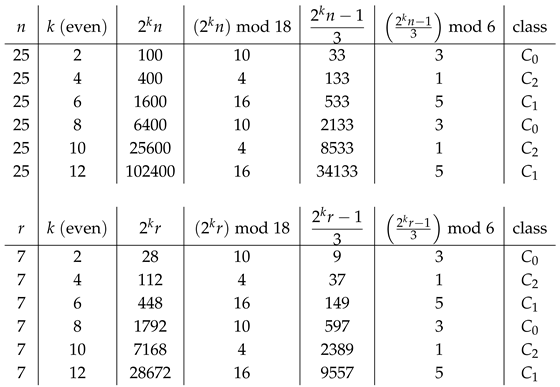

Table 2.

Residue classes, minimal exponents, orientation signs, and resulting triads for each live residue r.

Table 2.

Residue classes, minimal exponents, orientation signs, and resulting triads for each live residue r.

| r |

|

|

|

for

|

| 1 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

| 7 |

2 |

9 |

|

|

| 13 |

2 |

17 |

|

|

| 5 |

1 |

3 |

|

|

| 11 |

1 |

7 |

|

|

| 17 |

1 |

11 |

|

|

Interpretation. The affine reverse update law converts the inverse Collatz step into a linear rule on the quotient–residue plane. For each live residue r, the minimal admissible exponent fixes the slope and intercept of an affine map . The modulus 18 confines all results to nine possible odd residues, and the quotient modulus 3 serves as a rotating phase selector. Hence every pair specifies a unique successor .

Geometrically, the system behaves as a finite automaton of six residue rows () and three phase columns (). The “reset–resume” rule means that after each reverse step, the new residue and phase become the parameters of the next affine map. This continual reassignment makes the process locally deterministic but globally adaptive: the governing equation changes with each step while remaining finite. Terminal residues in close the automaton, ensuring every orbit eventually reaches a fixed point of the system.

Theorem 3.15 (Global Determinism and Finite Termination of the Reverse Automaton).

Let denote the residue and quotient at step t, and define

Then:

-

1.

For each step, uniquely determines , forming a finite deterministic mapping.

-

2.

-

The transition structure satisfies

producing the four active transition types .

-

3.

-

The system evolves through successive local maps

generating a finite deterministic sequence in the residue phase space.

-

4.

Each active transition ultimately reaches a terminal residue in within finitely many steps. The mapping admits no infinite nonterminal orbit.

Hence the reverse Collatz dynamics on odd integers forms a finite, locally deterministic reset and resume automaton whose transitions are governed by residue class and phase position at each step.

3.6. Bounded Corridor Dynamics at Fixed Residues

Among the six live residues modulo 18, only

have the special property that their first admissible reverse child under

remains in the same residue class. This follows directly from the triadic structure established in Sub

Section 3.3: all other live residues transition immediately to a different residue upon the first admissible lift, whereas

and

alone form self-contained local corridors under forward iteration.

Because these two residues can map to themselves under , their forward dynamics admit chains of arbitrary length determined solely by arithmetic properties of the phase index q. For , the forward map contracts by a factor of until the 2-power in q is exhausted. For , the forward map expands by for exactly steps, consuming one factor of 2 per iteration.

The results in the following subsections establish the precise structure and length of these corridors: - admits contraction chains controlled by divisibility of q. - admits expansion chains controlled by the 2-adic valuation of .

These two cases are the only local residue dynamics that can persist beyond a single step under , and their exhaustion determines the maximal extent of fixed-residue behavior in the entire system.

Let

If

q is divisible by 4, then

The forward update is then

Since we only care about the

q-level:

This shows that, as long as

q remains divisible by 4, the forward map strictly scales

q by a factor of

without changing the residue class

.

The descent in q continues until the 2-adic factor is exhausted, at which point the residue transition occurs.

Let

Then

If

q is odd (i.e.

), then

is odd, so

The forward update is therefore

Writing

gives

so

and

This map preserves the residue

precisely while

q remains odd. Rewriting the recurrence,

gives the explicit evolution

Hence the number of consecutive

steps is determined entirely by the 2-adic valuation of

:

Remark 3.16. If is a pure power of 2, the corridor length equals that power’s exponent exactly. If it contains an odd factor , the corridor length still equals e, and the odd factor merely remains as a cofactor during the valid steps. Thus the run length for is governed entirely by the 2-adic valuation of and not by any fixed external bound.

Together with the case, this establishes explicit local corridor dynamics: the map contracts by a factor until powers of 2 are exhausted, while the map expands by for exactly e steps, with e determined directly by the factorization of .

Lemma 3.17 (Higher admissible lifts are strictly ascending and rotate the gate).

Fix a live odd parent n and let be its minimal admissible exponent (determined by class). For each define the t-th admissible lift and reverse child by

Then:

- (a)

Strict ascent in the reverse value. The sequence is strictly increasing, with the exact increment

Equivalently,

so grows geometrically in t.

- (b)

Gate rotation (class rotation). The associated reverse middle-even residues rotate deterministically:

yielding the cycle (Lemma 3.9). Consequently the child class rotates .

- (c)

Higher lifts are higher transformations. Each increment multiplies the affine scaling factor by 4 (from to ) while preserving the constant drift . Thus every higher admissible lift is a strictly larger affine transform on n, independent of the gate rotation.

Proof. (a) Compute directly:

so

is strictly increasing. The closed form follows from

.

(b) This is Lemma 3.9: for admissible k, and , producing the stated rotation and class cycle.

(c) From , replacing k by multiplies the linear coefficient by 4 and leaves the drift unchanged, so the transform strictly enlarges the image while the residue gate rotates as in (b). □

For , the forward map contracts q by a factor of as long as q remains divisible by 4. Each iteration removes one factor of 2, so the chain length equals the 2-adic valuation of q. For , the forward map expands by while q is odd, and the number of valid steps is exactly . Thus the persistence of each corridor is determined entirely by local 2-adic content, not by any external bound.

Beyond these corridors, higher admissible lifts always increase the reverse value and rotate the middle-even gate through . Each lift multiplies the affine scale by 4 while preserving the constant drift, so the sequence of lifts is a strictly ascending geometric ladder. Together these facts show that fixed-residue behavior is finite and bounded, and that all non-terminal paths ultimately exit their local corridors to join the global terminating flow.

4. Consequences of Lens Refinement, Finite Reverse Lifespan, and Forward Convergence

In this section all integers are odd and positive. We retain the classes

the boundary residues

, and the live residues

. We also keep

,

, and

from the earlier setup.

4.1. Standing Conventions and Phase

Every odd

n is written uniquely as

We call

r the residue of

n and define the

phase

4.2. One-Step Reverse Lens Under : Triads and Boundary

Define the minimal reverse step

with

required odd. For a fixed

set

Lemma 4.1 (Triads and boundary presence).

For each live residue r, the set has exactly three elements and forms a triad. Moreover:

If , then .

If , then contains at least one boundary residue (5 or 7 mod 18), and the other elements lie in .

Proof. Reduce modulo 18; dependence is only on r and , giving and the stated boundary structure by direct casework. □

Lemma 4.2 (

is reverse-terminal).

If , then is not an odd integer.

Proof. If , then for all . □

4.3. Residue Rotation Law

Write

with phase

and let

be the class-determined exponent. Set

Then the minimal child

satisfies

so the residue advances by a constant step

inside a fixed triad (sign by class), while the new phase

is obtained from the affine quotient. Consequently the pair

uniquely determines

.

4.3.1. Generational Residue–Phase Map and Finiteness

Define the local update

This yields a finite, locally deterministic automaton on the space

with terminal sink

.

Interpretation. The residue rotation law establishes that every live residue r advances within a closed triad by a fixed modular step of . This motion is cyclic, but not self-sustaining indefinitely: each triad contains at least one boundary residue (either 5 or 7 mod 18) whose next image lies in the terminal set . Thus, although the rotation within a class appears periodic, the presence of these boundary residues ensures that repeated application of the map cannot cycle endlessly within or .

When viewed on the full residue–phase grid , the update law forms a finite directed graph in which each vertex has a single outgoing edge. Every orbit therefore follows a deterministic path through a bounded set of 18 states. Because at least one state in every rotation chain transitions to , all paths must eventually reach a terminal residue and halt. The rotation law therefore provides the local mechanism by which the global map attains finite convergence.

Theorem 4.2 (Finite local dynamics).

For each step, uniquely determines . Every nonterminal transition type lies among , and every trajectory in this finite automaton reaches a terminal residue in in finitely many steps.

4.3.2. Lift Microcycles and Guaranteed Boundary Access

For a fixed live parent

n, all admissible exponents have fixed parity; lifts

rotate the middle-even residue by a factor

:

so the child classes rotate

. In particular, within at most two lifts the gate

is attained, making

accessible.

4.3.3. Mod-54 Refinement: Fixing the Child Residue

Refining to modulus 54 splits each live residue into three residues ; the index selects the column of a lifted triad that already fixes the child’s odd residue modulo 18 at the first admissible reverse step. Thus determines the child residue.

4.4. The Self-Loop

Remark 4.4 (The trivial self-loop and phase stability).

The integer is the unique odd fixed point of the odd-to-odd map: . In the 18-lens we have , so and both residue and phase remain unchanged. On the reverse side, the minimal lift for is , and . Hence is the only state that self-loops while staying phase-stable at every lens; all other live residues either change residue at the first minimal step or exhaust their corridor in finitely many steps.

Corollary 4.5 (Forward convergence).

The forward odd-to-odd step

is unique and edge-aligned with a reverse admissible step (middle-even equivalence). Hence each forward trajectory is a single, non-branching chain that must terminate at 1.

4.5. Affine Arithmetic Decomposition

Lemma 4.6 (Affine form and accumulated drift).

Affine form. For any odd n and admissible k,

Accumulated form. Let be the exponents used in t reverse steps, set and

Then

This makes explicit the fixed per-step drift in every odd-to-odd reverse step.

Proof. The affine identity is immediate from . Iterating the affine map (e.g. by induction) yields with . If and , then with and , which rules out a nontrivial odd cycle. □

Corollary 4.7 (No nontrivial odd cycles).

Any closed reverse loop would satisfy with , which is impossible for .

Corollary 4.8 (Lift-by-2 ladder).

The reverse map is affine (scale , subtract ). In particular,

so each admissible parity class generates the ladder .

4.6. Consistency of Aligned Steps

4.6.1. The Trivial Loop from : Reverse and Forward Views

Lemma 4.9 (1 is

and has even admissible doublings).

Since , the integer 1 lies in class . Admissibility for the reverse step requires . With and , this gives , hence k is even. The minimal admissible doubling count is .

Proposition 4.10 (First child of 1 equals 1).

With , the reverse child of is

so the first child of 1 is 1 again. Consequently, under the reverse map with minimal admissible doubling, is a fixed point in class .

Remark 4.11 (Consistency with the forward picture: the

loop).

From the forward side, starting at 1,

which is the well-known loop. Thus the reverse fixed point at (with minimal ) corresponds exactly to the unique forward cycle.

Lemma 4.12 (Anchor–1 generation and coverage).

Define the stepped reverse family by composing admissible lifts at each state:

where at each step the residue and phase determine and the lift parity, and . Then:

- (a)

(Forward surjectivity from the anchor) Every odd occurs as a value of some finite composition . Equivalently, every live residue and phase is reachable from the anchor 1 by finitely many admissible stepped lifts with resets.

- (b)

(Two–anchor reduction) Since occurs in the first lifted triad from 1 (after one reset), all odd m are likewise values of a stepped composition beginning at the pair of anchors .

Proof. Work in the residue–phase automaton on

. By the mod-54 refinement, each state

has a unique first child residue

, and this mapping is periodic with fundamental period 54. By Lemma 3.12, the reverse child at each step is affine in the quotient,

so varying

q over

sweeps an entire congruence class of targets while the phase

selects the column of the triad. Starting at 1 and iterating admissible lifts, the reachable set of residue–phase states expands monotonically because higher lifts rotate the gate (

) while strictly increasing the affine scale. Using the corridor facts (

contracts until the 2-power in

q is exhausted;

expands for exactly

steps) together with the transition rows for

, an induction on the 54-block index shows that all six live residues and all three phases occur along some anchor–1 chain. Thus any odd

m is obtained as

for a suitable finite choice of lifts. The appearance of 5 along the same chains yields the two–anchor variant. □

Corollary 4.13 (No runaways via anchor origin).

Every odd integer lies on a stepped reverse path originating at the anchor 1 (equivalently at ) within the residue–phase system. Because this system consists of finitely many residue–phase states and every admissible reverse step remains within this finite automaton, no reverse chain can produce an infinite ascent that avoids the terminating class . In particular, the only locally persistent behaviors (the self-mapping residues and ) remain confined to the same finite residue–phase structure and cannot generate an unbounded escape.

Interpretation. The admissible reverse steps act entirely within the finite residue–phase automaton

Starting from the anchor, higher lifts only rotate the gate among the three residues

modulo 18, while the reset–resume update replaces each state

with the residue and phase of the new odd child. Because

contains all possible live residue–phase states, and every admissible step maps one element of

to another, no reverse iteration can ever escape this finite structure.

Moreover, each triad contains at least one boundary residue whose next image lies in the terminal class . Thus, although the motion of residues and phases is cyclic inside , the presence of these deterministic boundary exits prevents any unbounded ascent. Every branch eventually encounters a boundary state and therefore cannot form an infinite runaway chain.

Lemma 4.14 (Forward–reverse locked step).

Let n be odd and set

Then

Conversely, for any odd m and any admissible

k,

Proof. If then with m odd, hence .

Conversely, if with m odd, then so and . □

Corollary 4.15 (Forward uniqueness, reverse branching).

For each odd n, the forward step is unique (the maximal 2-power is forced). For a fixed odd m, every admissible k yields a (distinct) parent whose forward step returns m. Thus the reverse tree branches, while the forward trajectory is locked; following Lemma 4.14, the edge-aligned reverse choice at each node reproduces the forward path exactly.

Theorem 4.16 (No forward runaway; global termination).

Let be the odd-to-odd Collatz map. For every odd , the forward trajectory reaches 1 in finitely many steps.

Proof. By Lemma 4.14 the forward edge with is exactly inverted by the reverse edge . Thus the forward path is edge-aligned with a reverse path using the same exponents .

Encode each

as

with

and set the phase

. By the affine reverse update (Lemma 3.12) and the mod-54 refinement (Lemma 3.10, Corollary 3.11), the transition on states is a map

on the finite set

(Corollary 3.13). Hence the sequence

either (i) enters one of the two fixed-residue corridors of Sub

Section 3.6 (

or

), whose lengths are finite and equal to

and

respectively, or (ii) repeats a state in

.

Case (i) terminates because the corridor lengths are finite and every exit is governed by the same finite automaton, which ultimately reaches the gate that feeds the terminal class in the reverse picture.

In case (ii), a repetition with the same edge-aligned exponents would force a nontrivial cycle for the reverse affine map ; but the affine form together with the higher-lift monotonicity (Lemma 3.17) and unique parentage excludes nontrivial cycles. The only fixed odd point under T is 1 (since ). Therefore any repetition implies arrival at 1.

Thus, for every odd

n contained within the residue–phase system established above, the forward trajectory under

terminates at 1. □

5. The Global Framework: Affine Ladders, Dyadic Slices, and Complete Coverage

This section extends the global offset framework developed in

Arithmetic Offsets and Recursive Coverage Patterns in the Collatz Function [

2]. The earlier work established that the reverse map produces structured arithmetic progressions (offset ladders) whose superposition covers all admissible odd integers. Here we introduce the additional arithmetic machinery—zero–state normalization, the

z–index skeleton, and the dyadic slicing induced by

—which refines and completes that global description.

The three components now operate in a unified way:

1. the zero–state coordinate assigns each admissible odd a canonical position within the live lattice; 2. the affine inverse generates class–preserving ladders under via ; and 3. the dyadic slices partition the odd integers according to the 2–adic valuation of .

We show that these are not separate descriptions but exact arithmetic equivalents. Every affine ladder corresponds to a unique dyadic slice, every dyadic slice has a unique zero–state anchor in the

z–skeleton, and the union over all slices yields a disjoint and complete decomposition of

. Thus the global structure anticipated in [

2] is recovered as a special case of a more rigid algebraic framework that requires no step–count bounds and is compatible with the full local–to–global dynamics developed in

Section 3–4.

5.1. Offset Formulas in the Transformation

5.1.1. Offsets

From the mod 6 classification established in the prior section, every odd integer is congruent to 1, 3, or 5 modulo 6. The residue 3 gives the terminating class

, while the residues 1 and 5 produce the live classes

and

. Thus every

parent can be written in the form

where

t is a nonnegative integer indexing the position of

n within the

residue class. Equivalently,

t counts how many multiples of 6 have been passed before reaching

n. By the admissibility rule,

nodes allow only odd exponents

k. With the minimal choice

, the reverse Collatz function is

Substituting

gives

The offset is obtained by subtracting the parent:

Hence each

child lies an even step below its parent, and the step size grows linearly with the modulo 6 index

t. The resulting ladder of offsets is

Thus the offsets are the explicit arithmetic realization of the reverse rule with odd k, derived directly from the mod 6 classification.

5.1.2. C2 Offsets

From the mod 6 classification, every

parent can be written as

with

. By admissibility,

nodes allow only even exponents

k. With the minimal choice

,

Substituting

gives

Therefore the offset (child minus parent) is

Hence the first admissible reverse step in

is nondecreasing and, for

, strictly increasing in

t:

Concrete examples:

The explicit offsets for small values of

n are listed in

Table 4 in Appendix A. This table illustrates the arithmetic ladders described in

Section 5.1.1 and

Section 5.1.2, making the underlying arithmetic structure relative to each

n transparent up to

.

Lemma 5.1 (Offset Ladders by Class).

For each live parent n, the first admissible reverse step defines an arithmetic offset depending only on its class:

Moreover, higher admissible lifts of the same parent extend these formulas linearly in t with parity restricted to odd k for and even k for .

Proof. Direct substitution of with odd k and with even k into the reverse Collatz function gives the claimed offset formulas. The parity restriction follows from admissibility, so every live parent generates an infinite ladder of children determined solely by . □

Theorem 5.2 (Anchor principle).

All progressive path iterations of the Collatz map are anchored at the two primitive parents and . Every admissible lift (k even) and (k odd) generates an infinite raising sequence. These raising sequences partition the odd integers into disjoint arithmetic progressions modulo , and the union over all k gives complete coverage. Thus the global sequential progression structure is entirely determined by the anchor pair and their respective admissible k-values.

Corollary 5.3 (Exhaustion by anchors).

Every odd integer lies in exactly one ladder iteration of a raising sequence anchored at 1 or 5. No other origins exist, as the functions are derived from the base set wherein , i.e. and .

5.1.3. Further Lifts of Admissible k

The reverse Collatz function extends naturally to higher admissible exponents: odd

for

parents (

) and even

for

parents (

). Substituting these values into

gives the general offset formulas

The first admissible k gives the minimal child, and increasing k by two corresponds to a deeper lift along a higher ladder. Each successive lift remains tied to the progression index t, with the offset magnitude growing on the order of as k increases.

Remark 5.4 (Offsets and the itinerary).

The higher-k formulas confirm that offsets are determined not by the “generation depth” but by the progression index t and the parity of k. Which ladder is followed depends on the sequence of class transitions as the function is iterated. Thus and each sustain an infinite sequence of admissible steps, and the arithmetic progression of offsets is simply the explicit trace of the admissibility rules, computed relative to n at each transformation.

5.2. Arithmetic Progressions of Children

While offsets describe the displacement between a parent and its child, progressions describe how children of consecutive parents distribute across the integers. We now compute these inter-parent progressions.

5.2.1. Parents

Take consecutive

parents

and

. From the reverse rule with

, their children are

Hence

Thus first admissible children of consecutive

parents advance in an arithmetic progression with step size

.

5.2.2. Parents

Take consecutive

parents

and

. From the reverse rule with

, their children are

Thus first admissible children of consecutive parents advance in an arithmetic progression with step size .

Lemma 5.5 (Progressions of Consecutive Parents).

First admissible children of consecutive parents form arithmetic progressions:

Thus children of adjacent parents distribute evenly across odd integers with step size fixed by class.

Remark 5.6. The offset ladders of Section 5.1.1–Section 5.1.2 describe how each parent generates children in a ladder determined relative to its own value of n. The arithmetic progressions, by contrast, describe how numerically consecutive parents distribute their children across the integers. Both perspectives are needed: ladders explain the local offsets tied to each parent, while progressions explain the global coverage across parents.

For parents, each has the form . With the minimal admissible exponent , the child is

Subtracting the parent gives the offset

Thus the offset depends linearly on t and grows in magnitude as t increases.

For parents, each has the form . With the minimal admissible exponent , the child is

so the offset is

This offset also depends on t, and for it is strictly increasing.

Therefore, offsets are not fixed increments across all parents, but arithmetic expressions relative to each parent’s index t within its residue class. Each live class generates an infinite ladder of children, and the offset size expands with t while preserving the admissibility rule (odd k for , even k for ).

The arithmetic progressions across consecutive parents are simply the global counterpart of the same rule. When t increases by (advancing to the next parent in the same class), the child also advances by a constant step ( for at , for at , and in general ). This step is independent of t because the dependence on t is linear.

Thus the two descriptions are isomorphic: offsets show how children are positioned relative to a fixed parent, while progressions show how those positions line up across the sequence of parents. Both arise from the same affine relation , and together they capture the local and global arithmetic structure of the reverse Collatz map.

5.2.3. Higher Lifts

Lemma 5.7 (Quadrupling of Step Sizes at Higher Lifts).

For each class, increasing the admissible exponent k by two applies two successive doublings, thereby quadrupling the progression step size of consecutive parents. Concretely:

Proof. From the general offset formulas in

Section 5.1.3, the difference between children of consecutive parents is proportional to

. Replacing

k by

multiplies this factor by 4, hence quadruples the step size between odd children. Therefore each successive two-lift scales the step size by a factor of four. □

At higher admissible

k-lifts, step sizes scale as

: each unit increase of

k doubles the progression spacing, and in particular every two lifts quadruple it. A convenient way to display this is to show the two-lift subsequences and stagger the one-lift intermediates:

This pattern follows directly from the formulas of

Section 5.1.3.

Table 6 in Appendix A displays these higher-

k lifts explicitly. The overlay of odd and even admissible values shows how apparent gaps at lower scales are filled directly by higher lifts, ensuring complete coverage of the odd integers.

5.2.4. Visual Overlay

Corollary 5.7 (Visual Overlay and Complete Coverage).

Overlaying the progression ladders from consecutive parents shows that apparent gaps at lower admissible lifts are exactly filled by higher lifts. Each anchor sequence covers its congruence class without overlap, and the union across all admissible lifts exhausts the odd integers. Thus ladder iterations across all lift levels ensure complete coverage of . This structure is explicitly illustrated in Table 6.

Proof. By Lemma 5.5, consecutive parents generate fixed-step progressions, and by Lemma 5.7, higher admissible lifts scale these progressions by powers of four. The apparent omissions at a given scale correspond precisely to residue classes that are elements of progression of higher-lift ladders. Therefore the superposition of ladders fills all gaps systematically, partitioning the odd integers with no overlap. □

5.3. Anchor Ladders as the Basis of Coverage

All admissible structure originates from the two primitive anchors

and

. Each admissible lift

produces a new anchor point. Each such anchor initiates a ladder whose offsets and progressions are determined by its residue class and the parity of the admissible exponent

k.

Interpretation. [Dyadic gaps as lifted offsets] Each admissible exponent

k produces a dyadic slice

where

specifies the class. The quantity

is the gap between successive values in the slice and is the

exact offset created by the lifted exponent

k.

Thus increasing

k does not produce a new type of parent; it produces a new

spacing among the same admissible residue class. The anchor value determines the base point

while the dyadic step

determines how far apart the lift-

k parents of successive values lie.

In this sense, each higher lift corresponds to a wider offset lattice. Different values of k carve the odd integers into disjoint arithmetic progressions of increasing gap, and every such progression is exactly one dyadic slice. No slice overlaps another, and no odd integer is omitted.

Lemma 5.9 (Arithmetic derivation of anchors by class lifts).

For each anchor family with parent form , the reverse operator

generates an arithmetic progression at every admissible lift k (k odd for , k even for ). The constant term is the base residue of that progression and coincides with the anchor promoted at scale . Thus the starting anchors are derived arithmetically, and their descendants at higher k are exactly the ladder bases that fill sieve holes.

Proof. For

(class

, odd k):

Each case has the form

, with constants

serving as the promoted anchors at scales

.

For

(class

, even k):

Each case has the form , with constants serving as the promoted anchors at scales .

In both families, the step size doubles with each increment of k, and the base constant aligns exactly with the residue class left uncovered at the prior dyadic sieve. Thus the arithmetic shows both that the anchors are generated within the operator and that each higher k-level produces the ladder bases that fill the recursive sieve. □

5.4. Global Coverage by a Dyadic Sieve of Ladders

Proposition (First-child ladders and the 4-adic sieve by class).

Every admissible odd parent n is in exactly one of the two live classes

Let be a reverse child at lift k. Then:

- (A)

-

First admissible child (base sieve slice).

Thus the first children in are exactly (gap 4), and the first children in are exactly (gap 8). Equivalently, these are the odds with exactly one halving () and exactly two halvings () in , respectively.

- (B)

-

Higher admissible lifts stay in class and obey .Within a fixed class, raising the lift by sends each child to the next child by

Hence the children at lifts form a ladder by the affine update and remain in the same class ( for odd k, for even k).

- (C)

-

Gap quadrupling across lifts. Writing the first-child progressions as functions of t,

the lift update gives, for each ,

Thus each time the lift increases by

, the gap between consecutive children (as

t increases by 1) is multiplied by 4.

- (D)

Next sieve slice is generated by . For the first children () are . Applying yields the next slice (): , again gives the slice , and so on. For , the first children () are ; then gives ; then gives ; etc. In each class, generates the next sieve level and quadruples the modulus (the gap) each time.

Lemma 5.11 (Sieve slice measure for

on odds).

Fix . Among all odd integers m, the proportion for which is exactly .

Proof. Work modulo . Because 3 is invertible mod , the map is a bijection on residue classes. The condition is , which holds for exactly of odd residues; the stricter condition cuts that by another factor . Hence on odds. □

Corollary 5.12 (All-integers normalization).

For , the proportion ofallintegers m with m odd and is .

Proof. Half of all integers are odd; combine with Lemma 5.11. □

Transition: Canonical Reduction of Admissible Structure

The analysis above resolves the local admissible structure of the reverse map: each live residue admits a unique minimal exponent , produces a first child in its own class, and extends to a full ladder via the affine law . These statements describe the local geometry of the reverse tree but leave open the problem of identifying a canonical global parameter governing all ladders simultaneously.

Such a parameter arises naturally by removing the dyadic component of the first admissible step. The resulting zero–state provides a global coordinate system on the live lattice in which each ladder becomes a pure affine progression, independent of its parent. This reduction clarifies both the disjointness and completeness of the ladder family and supplies the arithmetic infrastructure needed for the global coverage theorem below.

We introduce this zero–state framework next.

5.5. Zero–State Enumeration and the Pure Affine Skeleton

The affine decomposition shows that each admissible reverse step

splits into a minimal admissible core and a sequence of

lifts. In this section we remove all reversible dyadic structure and isolate the intrinsic arithmetic skeleton of the map. The resulting

zero–state forms a canonical index on the live odd lattice and reveals that Collatz dynamics reduce to a pure affine counting system generated entirely by a base of:

No explicit use of the Collatz forward function is required once this zero–state system is established.

5.5.1. Minimal Admissible Exponents

Let

denote the live odd integers. For each

the reverse step

is integral precisely when

Since

and

n is never

in the live set, admissibility is determined by the parity of

k:

The

first child of

n is

5.5.2. Zero–State Extraction

The

zero–state of

is defined by removing exactly the admissible dyadic factor used to produce

:

Because admissibility guarantees

, this quantity is an integer for every live odd

n.

Ordered by size,

the zero–state reproduces the natural index:

(3) Even integers. If with n odd, then . Thus every even integer inherits the zero–state of its unique odd anchor.

5.5.3. Zero–State Law and the First Affine Step

A key identity is

Increasing the exponent by 2 yields

Iterating gives the recurrence

whose solution is

Substituting

,

Thus the entire admissible chain above

n depends only on the zero–state value

. The specific parent

n plays no role beyond producing

.

5.5.4. Enumeration Without the Reverse Map

Once

is known, the Collatz tree can be generated without the function

. Instead it is encoded by the affine generators

corresponding to C1 and C2 first–child lifts, together with their rail–lift iterates

Every reverse parent of

n has

z–index

Thus all reverse dynamics are modeled by the affine semigroup generated by

,

, and the rail lifts

.

5.5.5. Affine Ladders and Odd Coverage

For each

, the

affine ladder of

n is

Injectivity of the affine form

ensures that ladders are disjoint. Every odd integer

m has a unique representation

for some live

n and unique admissible

k, and writing

places

m on exactly one ladder:

Combining this with the dyadic decomposition yields full coverage of .

5.5.6. Affine z–Index Dynamics

Enumerate the live odds in increasing order,

Writing the reverse map in odd–to–odd form

we define

Lemma 5.13 (Child index at the

z–level).

Let and p be a reverse parent of n. Then

Proof. Direct computation using and the ordering of live residues shows that C1 parents occupy the –position and C2 parents occupy the –position in the enumerated lattice. Details follow from the residue classification and the fact that live integers occur in pairs . □

Since

coincides with a

lift at the

z–level, iterating

produces the rail lifts

.

| z |

n |

class |

operator |

z-child |

first child

|

| 0 |

1 |

C2 |

|

1 |

1 |

| 1 |

5 |

C1 |

|

3 |

3 |

| 2 |

7 |

C2 |

|

9 |

9 |

| 3 |

11 |

C1 |

|

7 |

7 |

| 4 |

13 |

C2 |

|

17 |

17 |

| 5 |

17 |

C1 |

|

11 |

11 |

| 6 |

19 |

C2 |

|

25 |

25 |

| 7 |

23 |

C1 |

|

15 |

15 |

| 8 |

25 |

C2 |

|

33 |

33 |

| 9 |

29 |

C1 |

|

19 |

19 |

| 10 |

31 |

C2 |

|

41 |

41 |

| 11 |

35 |

C1 |

|

23 |

23 |

| 12 |

37 |

C2 |

|

49 |

49 |

| 13 |

41 |

C1 |

|

27 |

27 |

| 14 |

43 |

C2 |

|

57 |

57 |

| 15 |

47 |

C1 |

|

31 |

31 |

| 16 |

49 |

C2 |

|

65 |

65 |

| 17 |

53 |

C1 |

|

35 |

35 |

| 18 |

55 |

C2 |

|

73 |

73 |

| 19 |

59 |

C1 |

|

39 |

39 |

| 20 |

61 |

C2 |

|

81 |

81 |

| 21 |

65 |

C1 |

|

43 |

43 |

| 22 |

67 |

C2 |

|

89 |

89 |

| 23 |

71 |

C1 |

|

47 |

47 |

| 24 |

73 |

C2 |

|

97 |

97 |

Table ?? First 25 live odd integers () with their z–indices, classes, affine generators, and first admissible children. The table illustrates the fundamental identity

i.e. the first admissible reverse child of n is exactly the live odd whose index equals the affine z–map (for C1) or (for C2).

Remark 5.14 (Why

is Terminal in the

Z–Lattice).

The Z–index is a bijection from the live lattice

onto , assigning each admissible odd m its global zero–state coordinate . No element of appears in , and therefore no

value admits a

Z–coordinate

. This is not merely a definitional omission: it is an arithmetic obstruction.

Indeed, if , then

so is never an integer for any . Thus no value can serve as a parent in the admissible reverse map Consequently, values areexactlythose odd integers that lie outside the zero–state coordinate system and therefore admit no further reverse continuation.

Hence the classical Collatz termination condition “entering ” is equivalently the statement that the reverse chain has left the Z–indexed affine structure. In this sense, the zero–state lattice is the structural backbone of the global reverse tree, and represents its natural boundary.

5.5.7. Affine–Dyadic Equivalence

In each reverse step with exponent

, the affine transformation on

z has linear coefficient

The dyadic slice theorem states that the probability that an odd

n satisfies

is

. Hence:

Theorem 5.15 (Affine–Dyadic Equivalence).

For every reverse exponent k, the affine expansion factor is and the dyadic slice weight satisfies

Thus each affine generator corresponds exactly to its dyadic frequency.

Corollary 5.16 (Coverage via Affine Slicing).

Therefore the affine semigroup generated by , , and forms a disjoint partition of the odd integers into slices of relative size and hence covers exactly once.

5.5.8. Interpretation

Removing reversible dyadic structure reduces Collatz dynamics to a deterministic affine counting system. The zero–state encodes each live odd integer as its z–index, and the reverse tree is generated entirely by the affine maps , and rail–lifts thereof. Each odd integer lies on exactly one affine ladder, all ladders are disjoint, and the union of ladders covers the odd integers. Forward halving gates extend the coverage to all integers. Thus the Collatz map is realized as a pure affine skeleton whose closure equals .

Theorem 5.17 (Global Arithmetic Coverage by Ladders).

Let be the reverse map with admissible parity per class. Then the following hold within Section 5:

-

1.

Base slices and fixed gaps. First admissible children are exactly

and children of consecutive parents form arithmetic progressions with those gaps (Prop. 5.10

, Lem. 5.5

).

-

2.

4-adic lift within class. Raising the lift by sends , stays in the same class, and multiplies the progression gap by 4 (Lem. 5.7 and the clause of Prop. 5.10).

-

3.

Overlay gives complete coverage. Superposing the ladders across all admissible lifts fills the apparent gaps of the base slices; within each class, the union over k exhausts its congruence classes with no overlap (Cor. 5.8).

-

4.

Anchor generation. All ladders are generated from the two primitive anchors (even k) and (odd k); each admissible lift promotes a new anchor and its ladder (Thm. 5.2, Lem. 5.9).

-

5.

Exact dyadic slice measures. Among odd m, the slice with has measure ; among all integers it is (Lem. 5.11, Cor. 5.12).

Consequently, the odd integers are covered disjointly by the class-preserving affine ladders generated from across all admissible lifts, with gaps and densities exactly as stated in (1)–(5).

5.6. Dyadic Sieve Index (Class–Forced Admissibility)

Definition 5.18 (Dyadic Sieve Index).

Let encode the class modulo 3 and encode the class modulo 6:

For each lift index , the admissible exponent is (odd k for , even k for ), and a single reverse step from produces

The dyadic slice weight (among odd ) for fixed k is .

Table 3.

Dyadic Sieve Index from the unified reverse step , with .

Table 3.

Dyadic Sieve Index from the unified reverse step , with .

| k |

Class |

x |

Gap

|

Anchor

|

|

| 1 |

|

5 |

4 |

3 |

|

| 2 |

|

1 |

8 |

1 |

|

| 3 |

|

5 |

16 |

13 |

|

| 4 |

|

1 |

32 |

5 |

|

| 5 |

|

5 |

64 |

53 |

|

| 6 |

|

1 |

128 |

21 |

|

| 7 |

|

5 |

256 |

213 |

|

| 8 |

|

1 |

512 |

85 |

|

| 9 |

|

5 |

1024 |

853 |

|

| 10 |

|

1 |

2048 |

341 |

|

| 11 |

|

5 |

4096 |

3413 |

|

| 12 |

|

1 |

8192 |

1365 |

|

| 13 |

|

5 |

16384 |

13653 |

|

| 14 |

|

1 |

32768 |

5461 |

|

| 15 |

|

5 |

65536 |

54613 |

|

| 16 |

|

1 |

131072 |

21845 |

|

| 17 |

|

5 |

262144 |

218453 |

|

| 18 |

|

1 |

524288 |

87381 |

|

| 19 |

|

5 |

1048576 |

873813 |

|

| 20 |

|

1 |

2097152 |

349525 |

|

| 21 |

|

5 |

4194304 |

3495253 |

|

| 22 |

|

1 |

8388608 |

1398101 |

|

| 23 |

|

5 |

16777216 |

13981013 |

|

| 24 |

|

1 |

33554432 |

5592405 |

|

| 25 |

|

5 |

67108864 |

55924053 |

|

| Dyadic slice weight for fixed k: (among odd ). |

Theorem 5.19 (Dyadic Sieve Decomposition).

Let and . Encode the class by

For each lift index , define (so k has the admissible parity for the class). The fixed-k static sieve slice is

Then

i.e. as increases (equivalently ), the union of these arithmetic progressionscovers every odd integer exactly once.

Proof.

Existence. Take any odd

m. Let

k be the highest power of 2 dividing

, i.e.

. Then

is even and has a unique residue

modulo 6 (parity forces

x odd, and

). Set

if

and

if

. Since

, there is

with

. Define

and solve for

m to obtain

Uniqueness. The factor k is uniquely determined by the largest power of 2 dividing , which fixes x, then c, then , and finally t. Hence m belongs to exactly one . □

Remark 5.20 (Anchors and gaps).

Each is an arithmetic progression with gap and anchor , where . The minimal slices () are

Corollary 5.21 (Dyadic slice weight).

For fixed k, the proportion of odd integers in is . These dyadic slices form a disjoint partition of the odd integers, and the weights sumexactlyto 1.

5.6.1. Middle-even gates and mod-18 progression

Lemma 5.22 (Gate equivalence at the middle even).

Let be the next odd. Then

with the class correspondence

In particular for every odd m, and over one mod-18 odd cycle the three gate residues occur with equal frequency .

Proof. Since , reduce modulo 18 and use the mod-6 classes of n; this is the same gate rule as Prop. 3.7. The split is the equidistribution of first-child classes from §3. □

Proposition 5.23 (Base middle-even progressions in mod-18).

Using the first-admissible children from Prop. 5.10:

Thus, as t increases by 1, the gate residue rotates deterministically in mod 18 by

and the union of middle evens across the two classes is exactly the gate set —i.e. precisely of all even residues mod 18.

Lemma 5.24 (Higher lifts act by

on middle evens).

If is the lift- child of m (Prop. 5.10, Lem. 5.7), then

hence , rotating the gate residues

Corollary 5.25 (Even-gate sieve ≡ dyadic sieve, in mod-18).

The partition of odds by (§4) corresponds, under , to class-preserving middle-even ladders whose residues cycle within and whose strides scale by the lift (Lemma 5.24). This gives a mod-18 even-side rephrasing of the ladder picture in this section, with no change to coverage or disjointness.

5.7. Global Consequences of Coverage

Theorem (Dyadic Slicing Yields Global Coverage).

Let and , and encode the class by

For each lift index set and define the dyadic slice

Then the family is a disjoint partition of the odd integers:

Equivalently, every odd m admits a unique representation

Proof.

Existence. For odd

m, let

. Then

is even and has a unique residue

modulo 6 (it must be odd mod 3 and even). Set

if

and

if

; then

, so

for a unique

. Define

Solving for

m yields

.

Uniqueness (disjointness). The factor is unique, which fixes , then c, then , and finally t by the displayed equation. Hence m lies in exactly one . □

Corollary 5.27 (Equivalence of Dyadic Slices and

z–Ladders).

Let be the dyadic slice defined in Theorem 5.26, and let

Then for every choice of ,

and conversely every element of arises uniquely in this way.

Hence the affine ladders generated by coincide exactly with the dyadic slices arising from the 2–adic valuation of .

5.8. Global Consequences of Dyadic Coverage

The dyadic partition in Theorem 5.26 shows that every odd integer lies on exactly one affine ladder

where

is the first admissible child

of a unique live integer

. Each ladder corresponds to a unique pair

with

, and the dyadic slices

form a disjoint partition of

. This section records the global consequences of this structure.

For any live odd

n with minimal exponent

,

Thus the entire admissible chain above

n is determined by

alone and consists of a pure affine progression. Varying

n ranges over all possible bases

, and Theorem 5.26 shows that these progressions are disjoint and collectively cover every odd integer. No dynamical descent or step-count analysis is required.

The parameters determine the admissible parity of and the residue of every first child. Higher lifts preserve class and correspond to further applications of the affine map . Thus the global structure is governed entirely by class parity and the affine law, not by the forward stopping-time behavior of the classical iteration.

Values have no reverse parent, so they appear as terminal nodes in the reverse tree. In the affine–dyadic model, this plays no role in global coverage: each dyadic slice is already complete, and terminals simply indicate the end of a branch when the tree is viewed in reverse. No argument based on “descent” or exhaustion of corridors is required for closure.

Because the dyadic slices partition and every slice corresponds to a complete affine ladder, the reverse Collatz graph is globally closed: every odd integer appears exactly once, on exactly one ladder, and is obtained from exactly one admissible affine generator. The forward map is then a deterministic projection down the ladders via halving, and all trajectories ultimately reach the base anchors .

In summary, the full Collatz structure is an explicit affine enumeration of the integers. Dyadic slicing provides the global coverage; affine ladders provide the local structure; and the interaction of the two yields a complete, closed description of the reverse map with no need for any step-bound or descent-based arguments.

Theorem 5.28 (Unique affine parentage and no runaway).

For every odd integer n the reverse and forward Collatz maps satisfy:

- (a)

-

Unique affine parentage. By Lemma 4.6

, every admissible reverse step is

By Lemma 4.14

, the forward gate

is unique and is inverted exactly by the edge-aligned reverse: and with . Hence each odd m has exactly one forward parent at its gate.

- (b)

-

Finite reverse descent along the unique affine ladder. Every odd integer n lies on a unique affine ladder

with base equal to its first admissible child. Along this ladder, admissible reverse exponents take the form with e decreasing at each reverse step until the minimal admissible exponent is reached.

Since is fixed by the residue class of the base child (C1 or C2), and reverse steps with reduce the dyadic height while steps with increase the odd value, the ladder cannot descend indefinitely. Furthermore, the only self-stable odd under this ladder structure is 1, so all reverse descent terminates either at 1 or at a class- boundary.

- (c)

No nontrivial odd cycles; no forward runaway. By Lemma 4.6

, any t-step reverse composition satisfies

which is impossible for ; hence no nontrivial odd cycle exists. By (a)

the forward step is unique at each node, and by (b)

the only descending reverse corridor is finite. Together with the finite reverse lifespan (Theorem 4.3)

, there is no infinite forward runaway.

Lemma 5.29 (Even integers inside the

k–valuation skeleton).

Every positive integer N admits a unique dyadic decomposition

For each odd m, the odd–to–odd Collatz gate is

so that with odd.

Each admissible reverse step

is a pure dyadic lift: the exponent k records exactly how many factors of 2 are injected above n in the reverse direction. Thus the collection of all k–lifts already accounts for every power of 2 that can appear above any odd anchor in the reverse tree.

In forward time, starting from , the halving steps strip off the dyadic factor until the odd anchor m is reached, after which the gate removes the remaining admissible factors of 2 from . Consequently, every even integer N lies on the same k–valuation skeleton as its odd anchor m: no new branches arise from even inputs, and every factor of 2 above m is realized either as a trivial halving step or as part of an admissible exponent k in the reverse/forward pair.

Corollary 5.30 (All positive integers are carried by the odd skeleton).

If every odd integer m lies on the affine reverse skeleton and converges to 1 under the forward map T, then every positive integer also converges to 1.

Proof. Given

, write

with

m odd. By Lemma 5.29, the forward trajectory of

N coincides with that of

m after finitely many halving steps:

Since, by hypothesis, the odd anchor

m lies on the closed affine skeleton and reaches 1 under

T, the same is true for

N. Thus closure of the odd subsystem implies closure of the full Collatz map on

. □

Theorem 5.31 (Global Forward Convergence to 1).

For every odd integer N, the forward Collatz trajectory obtained by iterating

reaches 1. Equivalently, there is no odd N whose forward iterates avoid 1 forever, and there is no nontrivial odd cycle.

Proof Fix an arbitrary odd starting value N.

Step 1. N sits on exactly one admissible reverse branch. By Theorem 5.26,

N lies in a unique dyadic slice

of the form

By construction of

, this

N is exactly an admissible reverse parent

for some odd child

n, with lift exponent

. In particular,

N is not “off-lattice’’: it is produced by an admissible reverse step from some

n.

Moreover, Corollary 4.8 shows that increasing the lift by 2 corresponds to the affine update . Thus the entire inverse chain feeding into N is a single arithmetic ladder, obtained by admissible lifts of strictly smaller exponents. There is no ambiguity: N belongs to one and only one such reverse ladder. This is the global form of unique parentage (see also Theorem 5.28(a)).

Step 2. No nontrivial cycles and no multi-parent mergers. Theorem 5.28(a) states that the forward gate

is unique: each odd

m has exactly one parent at its forward gate. Therefore two distinct reverse ladders cannot merge back into the same odd

m in forward time and then split again. Forward trajectories have no branching.