5.3. Arithmetic Consequences for Each Class

Lemma 5.2 (Class-pure images and immediate outcomes). For (odd):

If , n has no admissible reverse child (reverse termination).

If , then and ; for , (reverse ascends).

If , then and . Writing , the residue of decides the next class:

Lemma 5.3 (Least-admissible lift parity).

For an odd m, the least making an odd integer hasProof.

We need . Since , if then forces k even, so take . If , then forces k odd, so take . In both cases the numerator is odd and divisible by 3, hence is odd.

Proposition 5.4 (Deterministic parent map on the six live residues mod 18). Write any live odd as with and . With k from Lemma 5.3, the parent has the following closed forms and residue evolution, where with .

(1) (class ).Here and

Decomposing ,

(2) (class ).Here and

(Note: are ; these are dead leaves.)

(3) (class ).Here and

(Dead leavesagain: .)

(4) (class ).Here and

(5) (class ).Here and

(6) (class ).Here and

In particular:

(both ) force either a dead leaf in one step () or a move into the trio ().

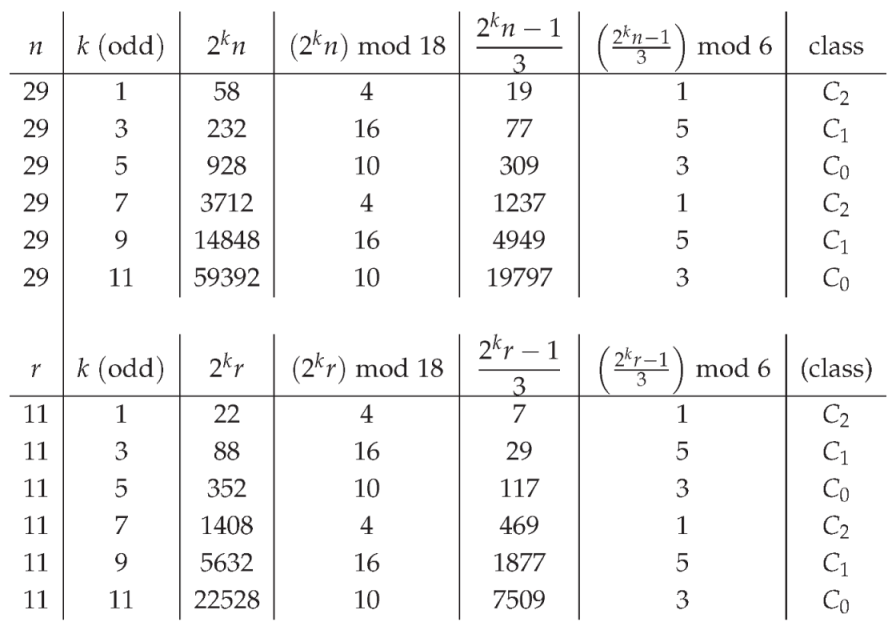

cycles deterministically within the trio according to .

injects into the trio; stays within the trio; drops to a dead leaf immediately.

Lemma 5.5 (Finite self-similarity on the 17-branch).

If , write . Then

In the self-preserving case (), one has with . Hence any chain that stays in residue 17 is finite.

Proposition 5.6 (Deterministic replication runs are finite).

Let be the least-admissible parent map on odd m, with k determined by (Lemma 5.3), and write every live odd as with and . Define thereplication run length

at residue r by

Then:

Only and can replicate consecutively.For the next parent is a multiple of 3 (dead), and for the next parent moves to the other live trio; hence for .

-

Exact run lengths via 3-adic valuations.With the 3-adic valuation,

Finite bounds; no infinite replication. For there isnoinfinite replication: for all , since for all ℓ has no nonnegative solution. For , occursonlyat (i.e. ), giving the trivial fixed point . For all , .

Proof. (1) The residue transition law from Proposition 5.4 shows and (dead), (moves to the trio), and (moves to the trio). Hence only can feed r again.

(2) For , Proposition 5.4 gives when and otherwise . Writing , the updated ladder index is ; iterating, a run of length ℓ requires t divisible by but not by , so .

For , we have iff ; write , then . Requiring another stay forces , i.e. , etc. Induction yields the cylinder condition for a run of length at least ℓ, with extension to length iff . Thus .

(3) If then for all ℓ, forcing in the 3-adics, contradicting . If then for all ℓ, hence , i.e. ; conversely gives the trivial infinite run. □

Corollary 5.7 (Deterministic bounds on replication).

For every odd , any consecutive residue replication under the parent map is finite:

In particular, no nontrivial residue can replicate indefinitely.

Corollary 5.8 (Prefix closure at a chosen start

n).

Under reverse–forward equivalence at the mod-18 gate (Lemmas 3.9, 3.11), fix an odd n. For every admissible reverse path

the forward odd-to-odd trajectory from n is exactly the reversal of the finite prefix to 1:

In particular, whenever n lies on such a path starting at 1, one has . Any live reverse continuation beyond n is irrelevant to the realized forward trajectory.

Proof. Let be any admissible reverse path. By the gate lemmas (Lemmas 3.9, 3.11), for each we have . Composing these identities gives , so the forward odd-to-odd trajectory from n is exactly the reversal of the finite prefix back to 1. □

Lemma 5.9 (Reverse finite replication ⇒ forward non-runaway).

Let T be the forward Collatz operator on odds,

and let P be the reverse graph map with the least admissible k (Lemma 5.3). If every reverse branch has finite replication length as in Proposition 5.6, then no forward trajectory can diverge or realize an unbounded runaway.

Proof.Assume some forward trajectory were unbounded. Reading it backward yields an infinite ancestral chain in the reverse graph, contradicting the hypothesis that every reverse branch has finite replication length. Indeed, by Proposition 5.6 the only self-replicating residues have finite block lengths

and outside those blocks a reverse branch eitherterminates in , moves to a different residue in finitely many steps, or ascends by a higher-lift. Hence no descending reverse chain is infinite. Since each forward step is the inverse of a unique admissible reverse lift (Lemma 6.4, Proposition 6.5), any infinite forward ascent would imply an infinite reverse lineage, which is impossible. Hence no infinite forward trajectory exists.

In particular, whenever a reverse branchclosesby hitting , its forward dual segment reaches the odd fixed point 1 (the loop in the full map). □

Theorem 5.10 (Reverse–forward closure). Fix an odd n. We use the following established facts:

Gate equivalence.Forward and reverse steps coincide at the mod-18 gate (Lemmas 3.9, 3.11).

-

Reverse path existence at n.By Lemma 3.3, the admissible-lift set at every odd node is nonempty (with parity fixed by the gate). Consequently, there exists an admissible reverse path

(the continuation beyond n may be live; only the finite prefix to n matters).

Prefix reversal.For any such path through n, the forward odd trajectory from n is exactly the reversal of its finite prefix back to 1 (Corollary 5.8).

Then the forward trajectory from n is finite and terminates at 1.

Proof. By (2) choose a finite admissible reverse path through n. Applying (3) (with (1) in force) gives that the forward odd trajectory from n is the reversal of the prefix , hence . □

Lemma 5.11 (Necessity of a origin for forward ascent). Let be the ladder/progression indices of the odd subsequence of the forward trajectory of n. Assume the forward odd sequence is infinite and for infinitely many j. Then along the reverse-compatible path through the mod-18 gate there exists at least one step of type with . Equivalently, if no step occurs on any reverse-compatible path of n, then is eventually nonincreasing and cannot realize an unbounded forward ascent.

Proof. Forward odd steps are determined by , while reverse lifts admit multiple k but must respect the same gate. If no step ever occurs on any gate-compatible reverse path, then every gate-compatible segment avoids the only mechanism that strictly contracts the index, namely . In that case, along the forward odd subsequence the index cannot realize infinitely many strict increases without encountering a reverse segment that would force such a contraction; hence is eventually nonincreasing and cannot sustain an unbounded ascent. Contrapositively, if occurs infinitely often, some gate-compatible reverse segment must contain . □

Lemma 5.12 (Forward vs. reverse roles of higher lifts). In the reverse map, yields multiple admissible parent branches but does not contract the ladder index t. In the forward map, only is realized at each odd step, so higher lifts areunselectedand do not contribute to forward ascent. By Lemma 5.11, a forward trajectory cannot “escape” by chaining different lifts while merely interleaving segments between occurrences: any unbounded forward ascent would require a hit on some gate-compatible reverse segment, and such hits occur only finitely many times. Hence higher lifts do not create or sustain runaways.

Proof. By definition of the reverse map, admissible parents with enumerate distinct branches but leave t unchanged up to noncontracting transformations; in particular, no step with produces the strict contraction characteristic of . In the forward map, each odd iterate chooses uniquely , so higher lifts () correspond to unselected reverse branches and cannot be chained by the forward dynamics. By Lemma 5.11, any unbounded forward ascent would require at least one occurrence on a gate-compatible reverse segment, and such occurrences are finite in number (see, e.g., Theorem 5.13 / Lemma 5.9). Therefore higher lifts cannot create or sustain a runaway in forward trajectories. □

Theorem 5.13 (No runaway; finite bound at the anchor). Every forward trajectory has a finite ladder bound governed by the anchor at 1. In particular, any putative infinite forward ascent must originate from a gate-compatible reverse path containing a step; but whenever a step occurs (at index t), the next index on that branch strictly contracts to . Since repeated hits occur only finitely many times, the overall forward index sequence is bounded and the trajectory terminates at the anchor 1.

Proof. By Lemmas Lemma 5.9, 5.11, and 5.12, an unbounded forward ascent would require a origin on a reverse-compatible path. But each such hit strictly decreases the index on the reverse path, and thus can occur only finitely many times. Between these finitely many contractions, the ladder index remains within a finite envelope, so the odd subsequence is bounded above and therefore cannot realize an infinite ascent. The ladder system has the anchor at 1 as its finite lower bound; hence the forward trajectory terminates at 1. □

Proposition 5.14 (Finite bounds for all class-level live→live transformations). Write every live odd as with and . Under the least-admissible parent map :

- (A)

-

(only via ). A consecutive block of steps can occuronly

while the residue remains . Its exact length is

with (trivial fixed point) and for all . If the block ever leaves (to 7 or 13), it terminates on the next step (those go to ), so no longer block persists outside .

- (B)

-

(only via ). A consecutive block of steps can occuronly

while the residue remains . Its exact length is

which is always finite since . Any visit to dies immediately (), and exits to on the next step.

- (C)

-

(only via ).Every step arises from , with

Hence a consecutive block of has length at most 2: the first step (from 13) lands in ; the next step is either to 5 (dead), to 17 (after which any further step must be of type covered by (B)), or to 11 (whichexits

to next). Therefore

and in fact any extension beyond length 1 must immediately change type to either or .

- (D)

-

(only via ).Every step arises from , with

Therefore a consecutive block of has length at most 2: the first step (from 11) lands in ; the next step is either to 7 (dead), to 1 (after which any further step must be of type covered by (A)), or to 13 (which immediately yields next). Thus

and any longer continuation necessarily switches type to (A) or (C).

Corollary 5.15 (Higher lifts define distinct reverse rails).

For each odd n and admissible , the reverse lift

generates a unique and disjoint reverse rail anchored at n. Unlike the case, higher lifts do not produce a contraction of the ladder index t; they simply enumerate separate, non-interacting rails. Since forward dynamics select only at each step, a forward trajectory cannot indefinitely ascend by moving among these higher-lift rails.

Corollary 5.16 (Finite-bound map for the reverse function).

Every reverse trajectory factors into a concatenation of blocks of the four types , , , . The lengths of these blocks obey the deterministic bounds

Consequently, no reverse path can remain forever in the live set: every branch has finite depth before either reaching the anchor 1 (the only infinite self-loop) or hitting a dead node.

Theorem 5.17 (Universal reverse cylinder map).

Fix a start residue and an integer . For each ternary word there exists a unique residue path

such that for every the L-step reverse trajectory of under P satisfies for . Moreover, the map

is well-defined, and the family of cylinders forms a partition of .

Proof sketch By Proposition 5.4, for fixed r the image depends only on , and the next index is an affine function of (explicitly computed there). Thus, given and , we set and obtain uniquely; we then write to get as an explicit affine function of , so that is determined by , hence is determined, and so on. Inductively this defines a unique residue path for all t in the cylinder . Distinct words give disjoint cylinders, and the union of all cylinders is . □

Corollary 5.18 (Exact occurrence and density of reverse paths). Fix and L. Every length-L reverse residue path arises fromexactly disjoint cylinders , hence has total occurrence density in . In particular, the single-step transition probabilities from any live residue r split evenly among its three admissible images (each ), and length-L path probabilities are products of these factors.

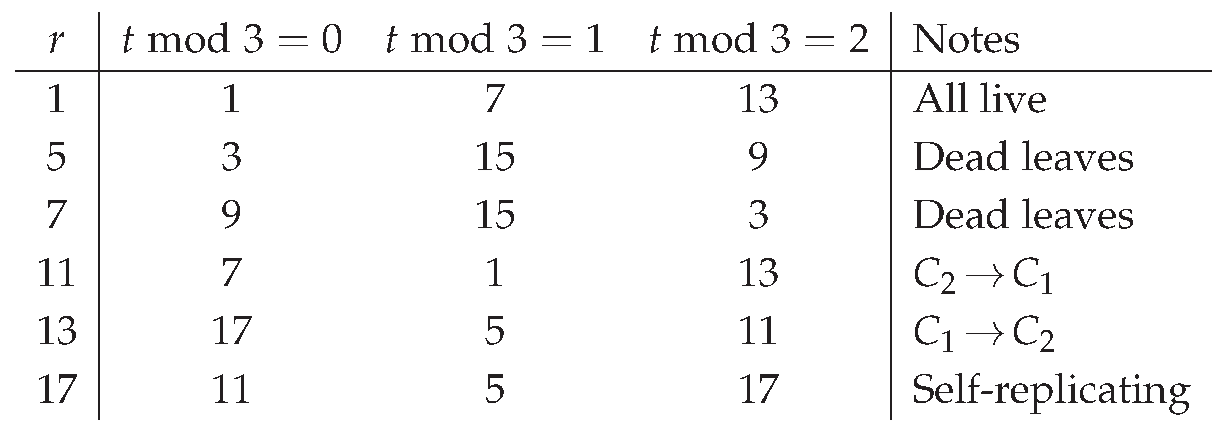

Proposition 5.19 (Live→live block bounds and finite-bound reverse map).

Every reverse trajectory factors into a concatenation of live→live blocks among the four class types

The maximal lengths of consecutive blocks are deterministically bounded by

Consequently,everyreverse path has finite depth in the live set before either reaching the anchor 1 (the unique fixed point) or hitting a dead residue in .

Proof idea. The bounds for and are Proposition 5.6 (, ). The cross-class bounds follow from the explicit residue updates in Proposition 5.4: and force either a dead leaf, an immediate change of class type, or entry into one of the two replicated cases already bounded. □

Corollary 5.20 (Universal reverse full map, finite). For each start residue , the reverse graph decomposes into a radix-3 cylinder tree (Theorem 5.17) whose edges are the deterministic transitions of Proposition 5.4, and whose blocks obey the finite bounds of Proposition 5.19. Hence there is no infinite live branch in the reverse graph, and—by duality with the forward map—no forward runaway trajectory.

Remark 5.21 (Exact locations of long runs). For the path segment occurs precisely on but (two APs mod ); for the segment occurs precisely on but (two APs mod ). These are the explicit “where they land” formulas used to index long runs without logarithms.

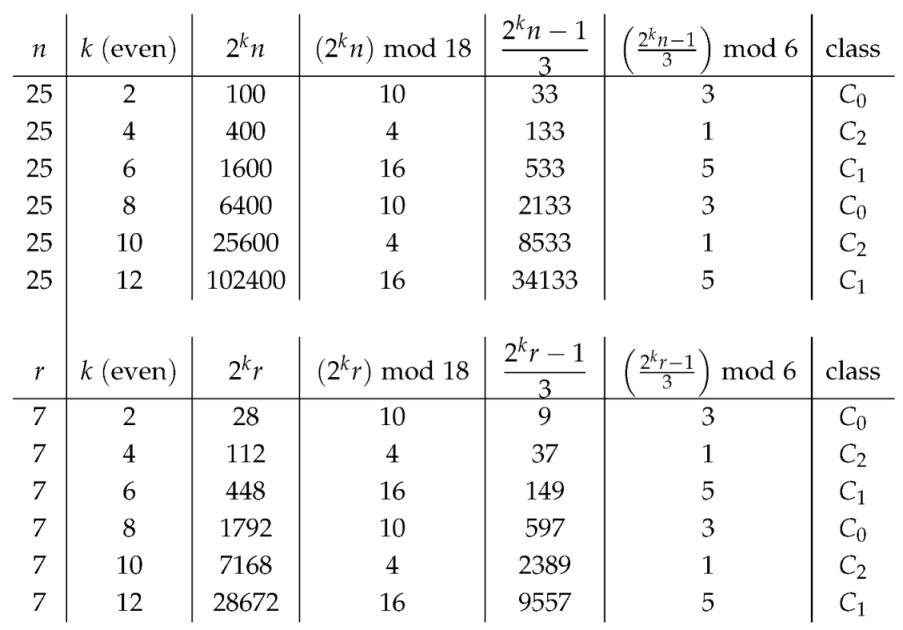

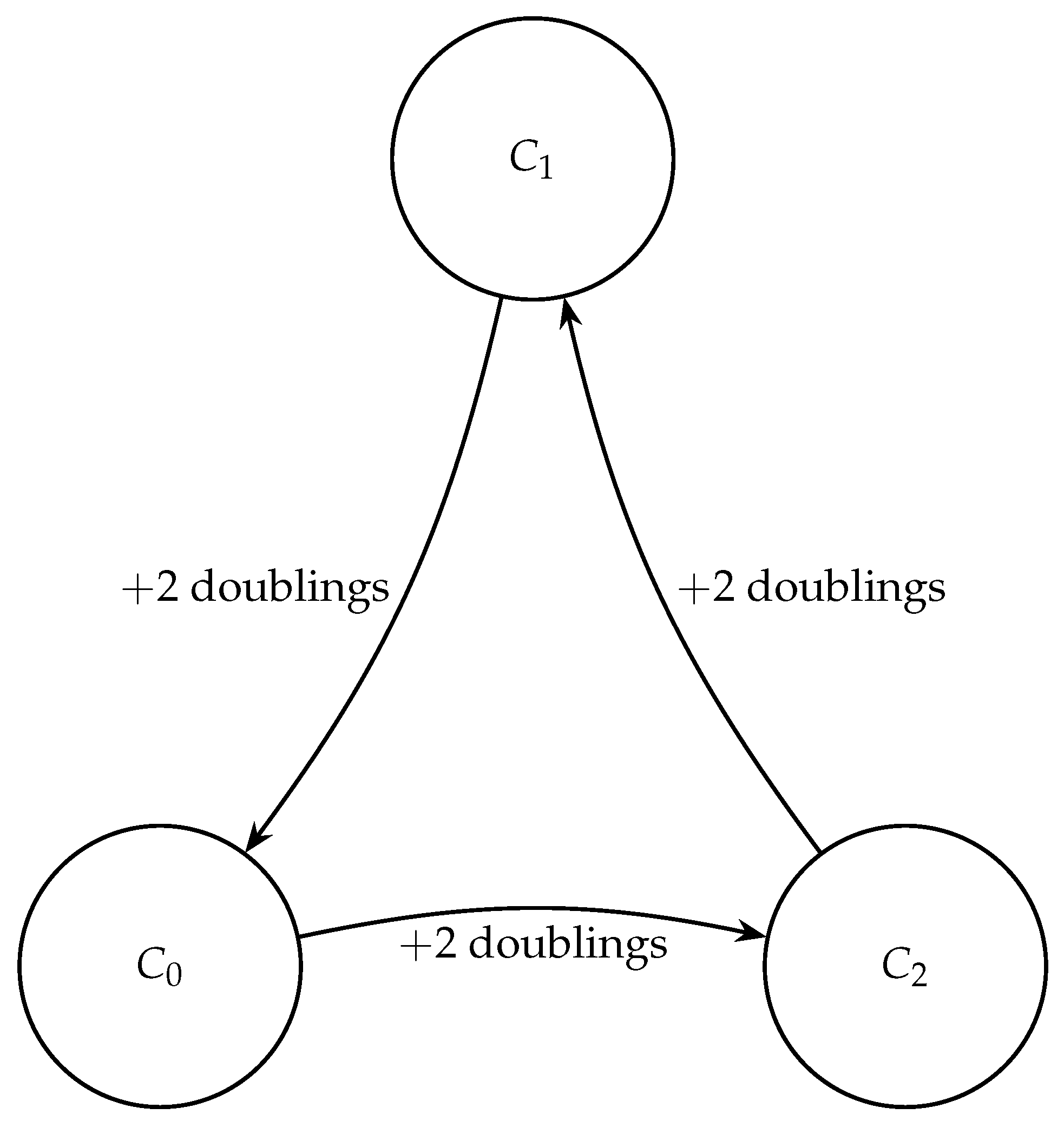

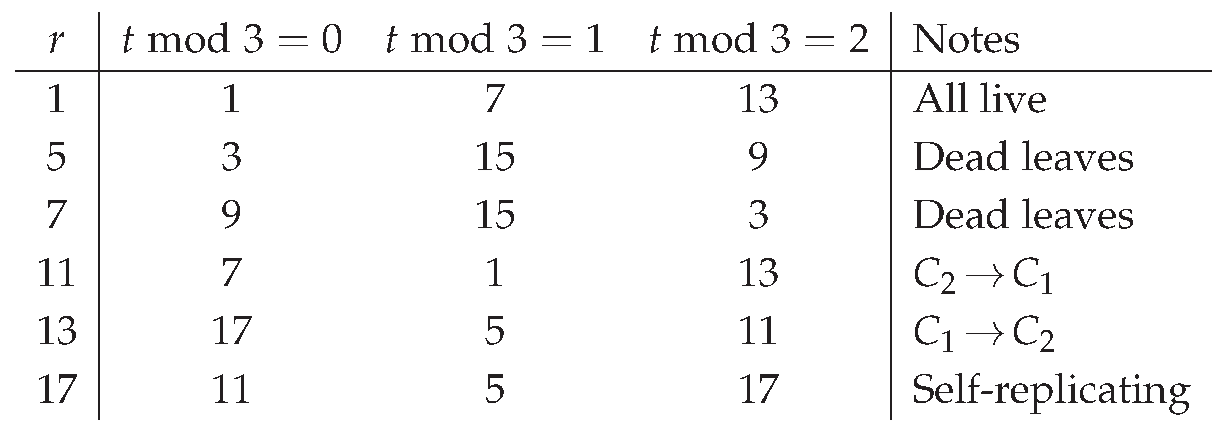

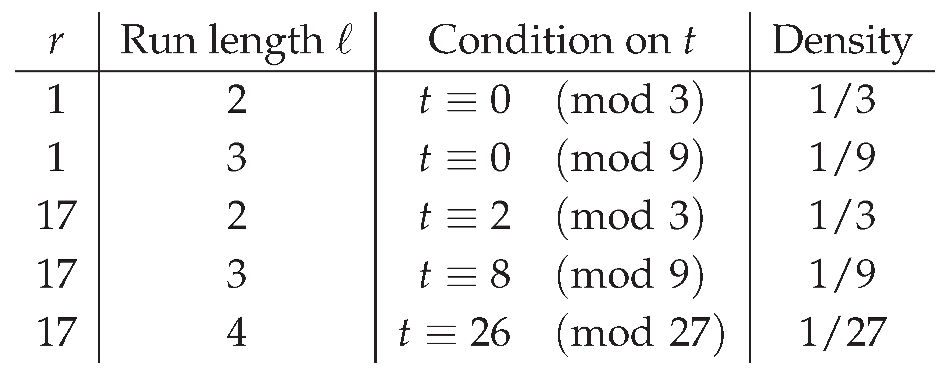

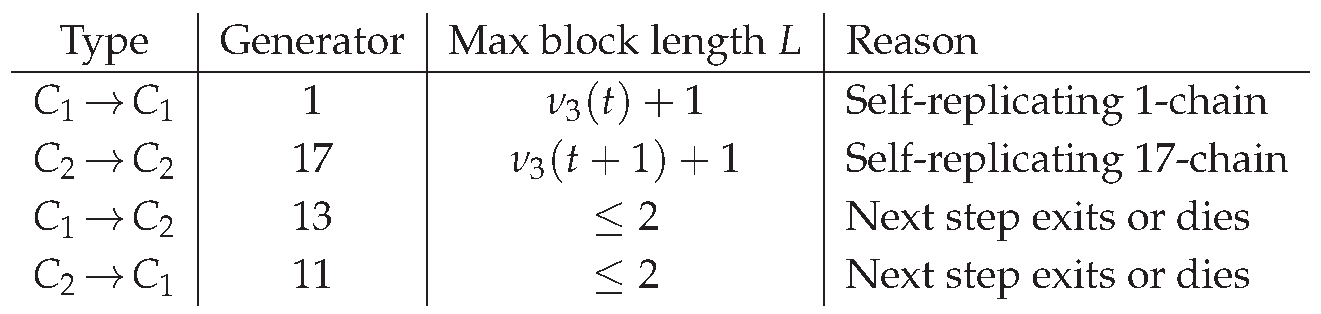

Example (Visual summary of the universal reverse map). The following tables illustrate the deterministic structure described in Corollary 5.20.

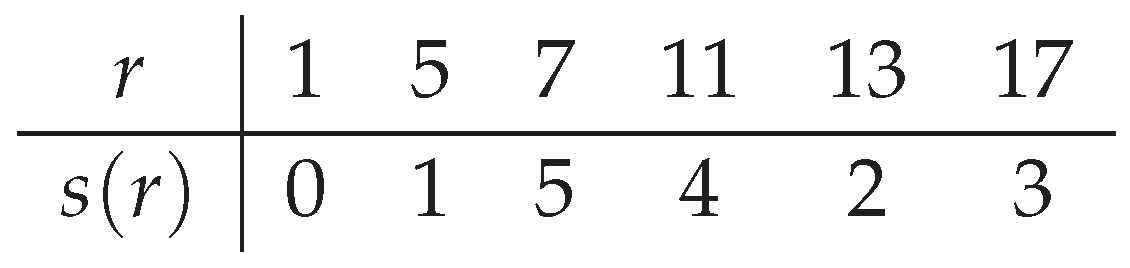

(A) Single-step residue transitions.

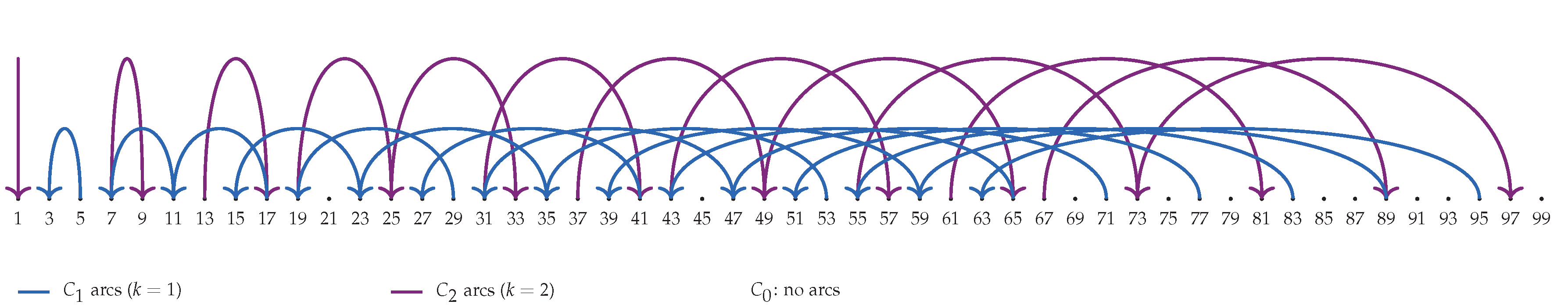

(B) Ternary cylinder trees (depth ).

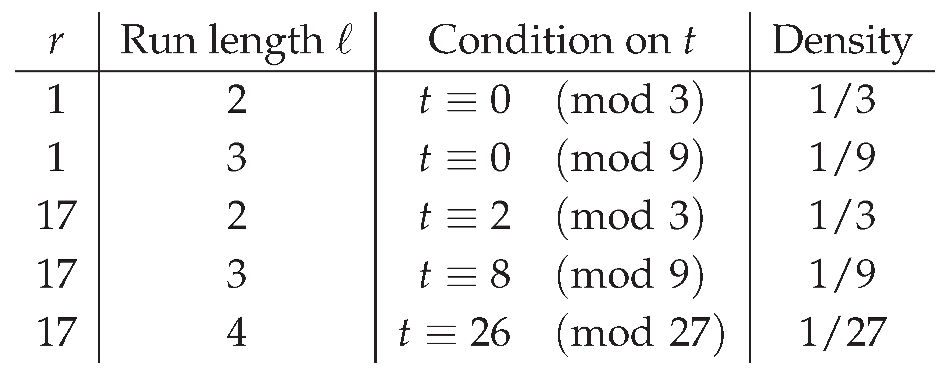

(C) Long-run congruence conditions.

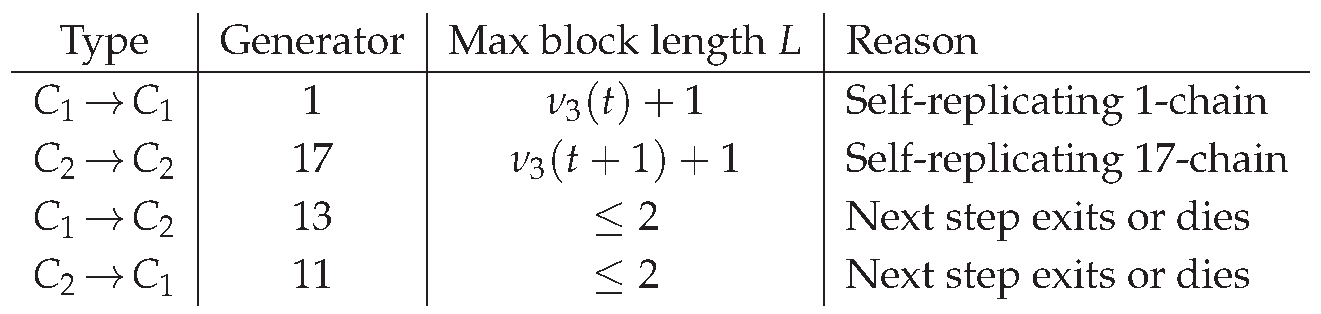

(D) Class-to-class finite bounds.

(E) Finite-bound map summary.

Together these visual fragments show that every reverse branch is a ternary cylinder of finite depth, the only infinite loop being the trivial .